Original article

Angiography-derived index versus fractional flow reserve for intermediate coronary lesions: a meta-analysis review

Índice derivado de la angiografía frente a reserva fraccional de flujo en lesiones coronarias intermedias. Revisión de metanálisis

aDepartamento de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain bCentro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has revolutionised the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, providing an alternative to surgical valve aortic replacement, especially in high-risk patients. Despite its benefits, significant interregional variability in TAVI access persists within Spain. This study aimed to analyse disparities in TAVI implementation across different autonomous communities, identifying the key factors underlying this variability.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective observational study using data from the Spanish National Registry of Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set for 2016–2023, including all TAVI performed in Spain. Additionally, a survey was distributed among specialists from 123 centres to assess the factors influencing clinical decision-making, barriers to access, and resource availability.

Results: Although the number of TAVI increased across all regions, significant differences were observed in the implantation rates (between 0.63 and 2.28 per 10 000 inhabitants). Survey responses indicated that the primary determinants for TAVI indication were heart team judgment (40.0%) and patient risk stratification (36.5%). The main barriers to expanding TAVI access included rigid patient stratification (25.6%), insufficient early detection (17.8%), and resource limitations (13.3%). Participants emphasized the need for better coordination among health care levels and establishing uniform access criteria.

Conclusions: Although TAVI adoption has increased in Spain, significant regional disparities remain, suggesting factors beyond economics contribute to access variability. Addressing these inequalities requires enhanced coordination across different health care levels, optimized resource allocation, and refined patient selection strategies.

Keywords: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Aortic valve stenosis. Health inequities. Health services accessibility. Delivery of health care.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) ha revolucionado el tratamiento de la estenosis aórtica grave sintomática, ofreciendo una alternativa al reemplazo quirúrgico, en especial en pacientes de alto riesgo. A pesar de sus beneficios, persiste una significativa variabilidad interregional en el acceso al TAVI en España. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo analizar las disparidades en la implementación del TAVI entre las distintas comunidades autónomas, e identificar los factores determinantes de la variabilidad.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo con datos del Registro de Actividad de Atención Especializada Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos para el periodo 2016-2023, abarcando todos los procedimientos de TAVI realizados en España. Además, se distribuyó una encuesta entre especialistas de 123 centros para evaluar los factores que pueden influir en la toma de decisiones clínicas, las barreras de acceso y la disponibilidad de recursos.

Resultados: El número de procedimientos de TAVI aumentó en todas las regiones, pero se observaron diferencias significativas en las tasas de implantación, que se situaron entre 0,63 y 2,28 por 10.000 habitantes. Las respuestas de la encuesta indicaron que los principales determinantes para la indicación de TAVI fueron el criterio del equipo médico (40,0%) y la estratificación del riesgo del paciente (36,5%). Las principales barreras para incrementar el acceso al TAVI incluyeron la estratificación rígida de los pacientes (25,6%), la detección temprana insuficiente (17,8%) y las limitaciones de recursos (13,3%). Los participantes subrayaron la necesidad de mejorar la coordinación entre los niveles asistenciales y la estandarización de los criterios de acceso.

Conclusiones: Aunque la adopción del TAVI en España ha crecido, persisten importantes disparidades regionales que no pueden explicarse únicamente por factores económicos. Para abordar estas desigualdades es necesario mejorar la coordinación entre niveles asistenciales, optimizar la asignación de recursos y perfeccionar las estrategias de selección de pacientes.

Palabras clave: Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Estenosis de válvula aórtica. Inequidades en salud. Accesibilidad de los servicios de salud. Atención a la salud.

Abbreviations

AC.: autonomous communities. AS: aortic stenosis. SNS: Spanish National Health Service. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular heart disease, with a prevalence of 3% in individuals older than 65 years and 7.4% in those older than 85 years. AS is more common in men.1,2 It is the leading cause of valve surgery in the adult population,3 and is associated with risk factors such as advanced age.4,5 Although aortic stenosis typically develops after age 60, symptoms usually present between ages 70 and 80; once symptoms occur, the mortality rate may reach 50% within the next few years.4,6

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), initially reserved for patients deemed ineligible for surgical aortic valve replacement,7-11 was subsequently expanded to include those at intermediate risk and, more recently, patients at low risk.5,12-14

In Spain, the use of TAVI has increased,5 reflecting its growing acceptance within the Spanish National Health System (SNS), largely attributable to improved clinical and economic outcomes.5,15 Multiple studies have demonstrated the benefits of TAVI, including significant improvements in quality of life,16,17 lower rates of major complications,18 and reduced mortality.5,19,20

Nationwide, improvements in TAVI outcomes, shorter lengths of stay, and lower mortality rates have been reported. Furthermore, autonomous communities (AC) with higher implant volumes have a better safety and efficacy profile, lower risks of infection, reduced need for permanent pacemaker implantation, and shorter lengths of stay.5 However, the distribution of TAVI reveals notable interregional disparities, with procedural rates varying considerably according to hospital resources and volumes.21

Despite these advances, in Spain, TAVI use remains significantly lower compared with other European countries.22 Furthermore, Spain exhibits one of the highest variations in access and utilization rates among its AC (42%), which cannot be explained solely by economic differences, hospital utilization, or observed mortality.21 An analysis by de la Torre Hernández et al.21 described the need for strategies to promote equity in TAVI access across Spain.

This study analyzed heterogeneity in the use of TAVI across AC (2016–2023) and identified the factors associated with this inequality.

METHODS

TAVI data in Spain from 2016 through 2023

Data on TAVI performed from 2016 to 2023 were obtained from the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set23-25 using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision for Spain (ICD-10-ES) (supplementary data 1). This mandatory registry, which includes all specialized care centers, is managed by the Spanish Ministry of Health and ensures strict compliance with privacy and data protection standards. The analysis included all TAVI performed in public and private hospitals across AC.

Survey

Simultaneously, we designed a survey to gather information on therapeutic decision-making in patients with AS to identify possible factors influencing TAVI implementation and interregional variability previously observed. This survey was distributed to department heads of the 123 medical centers affiliated with the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Respondents were asked to extend the invitation to other department members to ensure representative and diverse responses.

The survey (supplementary data 2) covered clinical, structural, organizational, and patient-related aspects relevant to clinical practice during the study period, and was structured into 3 thematic blocks:

- – Center and participant characteristics (questions A1–C3): evaluation of institutional context and department composition, including variables such as the respondent’s specialty and annual budget allocation.

- – Patient selection and decision-making (questions C4–E2): identification of key clinical and demographic factors influencing therapeutic choice, as well as barriers and determinants shaping clinical team decisions.

- – Center evaluation and TAVI use (questions E3–F9): assessment of clinician perception and satisfaction regarding TAVI, and exploration of adoption, implementation, and geographic distribution of this strategy.

Responses were analyzed descriptive and qualitatively, allowing a comprehensive interpretation of factors influencing TAVI implementation and interregional heterogeneity.

RESULTS

TAVI in 2016–2023

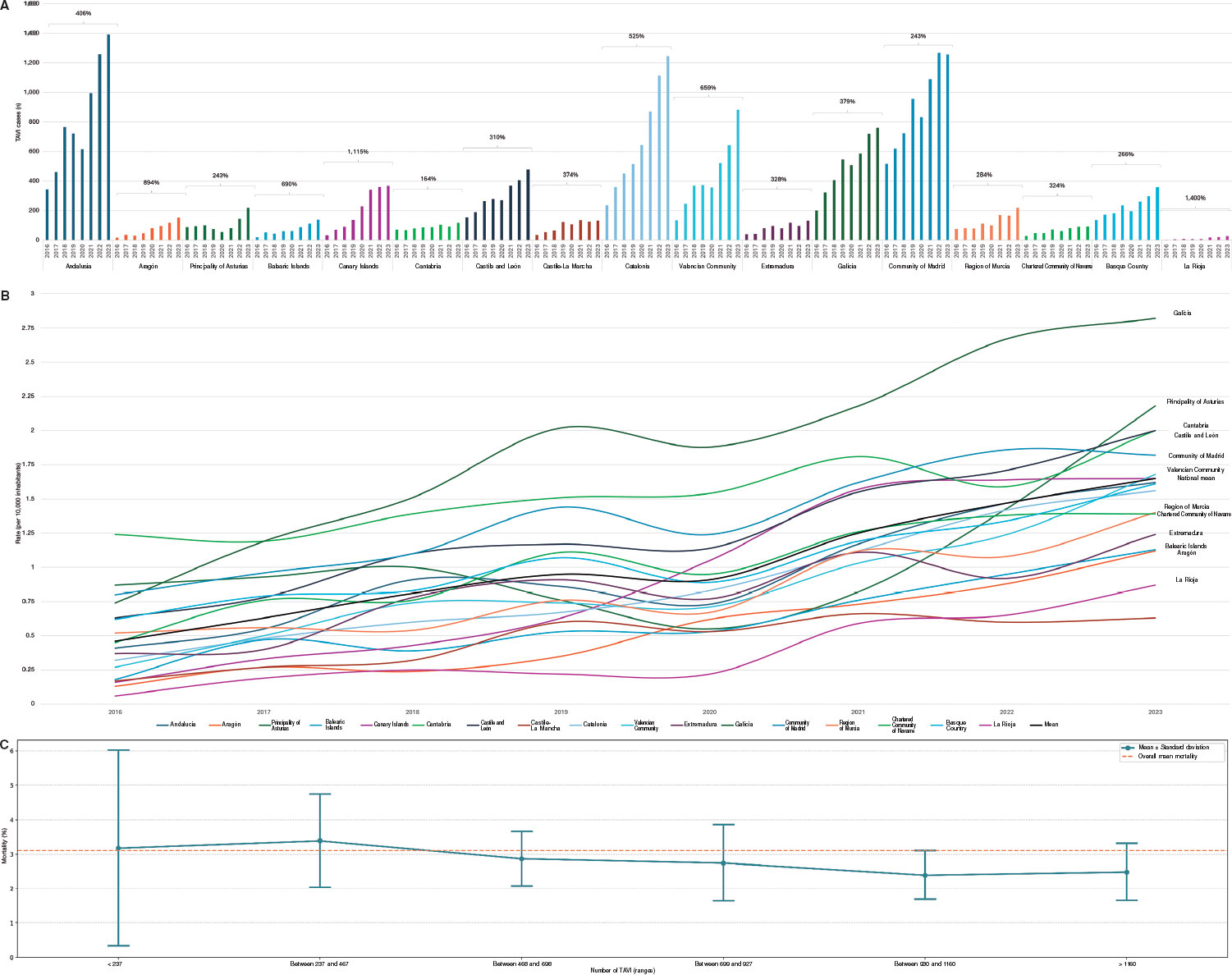

The results of TAVI interventions, expressed as the number of cases and intervention rates per 10 000 inhabitants, are shown in figure 1. All AC experienced an increase in procedures during the study period (figure 1A), with the greatest growth observed in the Canary Islands (33 cases in 2016 and 368 in 2023) and La Rioja (2 cases in 2016 and 28 in 2023), corresponding to increases of 1.115% and 1.400%, respectively. The AC with the highest number of TAVI performed in 2023 were Andalusia (n = 1392), Catalonia (n = 1245), and the Community of Madrid (n = 1257). La Rioja had the fewest (2 cases in 2016, 28 in 2023).

Figure 1. A: total number of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) cases by autonomous community and year (2016–2023). B: population-adjusted procedural rates adjusted (per 10 000 inhabitants) by autonomous community and year (2016–2023). C: mean and dispersion of mortality based on the number of TAVI.

Procedure rates (figure 1B) indicated that, in 2023, the AC with the highest per capita TAVI volumes were Galicia (2.82 per 10 000 inhabitants), Asturias (2.18 per 10 000), Cantabria (2.00 per 10 000), Castile and León (2.00 per 10 000), and Madrid (1.82 per 10 000), all above the national average (1.65 per 10 000). The lowest per capita TAVI volumes were found in Extremadura (1.24 per 10 000), the Balearic Islands (1.13 per 10 000), Aragón (1.12 per 10 000), La Rioja (0.87 per 10 000), and Castile-La Mancha (0.63 per 10 000).

The mean in-hospital mortality rate during the study period was 3.07% (figure 1C).

Survey

Center and participant characteristics

The survey was completed by 26 specialists with different TAVI-related profiles: 18 in interventional cardiology, 7 in clinical cardiology, and 1 in cardiac imaging, including 4 heads of cardiac surgery departments and 18 cath lab directors. The respondents’ mean professional experience was 26.5 years (range, 9–41 years) and worked in hospitals with a mean TAVI experience of 10.6 years (range, 1–16 years). Responses were obtained from hospitals in 11 of the 17 AC (64.7% of the national territory). Team composition by professional profile is provided in supplementary data 3.

Teams performed a mean of 76 TAVI (range, 0–148) in 2021 and 95 (range, 0–254) in 2022, with marked variation across hospitals. Annual budgets allocated to units ranged from €474 765 to €25 111 709, reflecting wide disparities in resource availability. Despite these differences, most respondents reported being satisfied with the extent to which purchasing committees allocated budgets to meet their teams’ clinical needs (19.2%, very satisfied; 42.3%, quite satisfied; 34.6%, moderately satisfied; 3.9%, unsatisfied).

Most participants rated continuity of care across different settings as good or improvable (54.9% and 38.5%, respectively) and gave examples of best practices as well as areas for improvement. Best practices included teleconsultation, specialized programs such as TAVI Nurse,26 periodic cross-level meetings, and shared protocols between primary and hospital care. Suggested improvements included insufficient coordination between primary and specialized care, overloaded schedules, and the need to improve clinical information systems such as integrating joint activities.

Patient selection and decision-making

The clinical indication for TAVI was determined primarily by heart team judgment (40.0%) and patient stratification (36.5%), followed by patient preference (12.5%) and resource availability (10.4%). Barriers to expanding TAVI included rigid patient stratification (25.6%), insufficient early detection (17.8%), intra-team discrepancies (14.2%), insufficient budget (13.3%) and technology (11.8%), and obstacles to multidisciplinary team integration (7.4%).

Most centers had decision-support tools for TAVI (76.9%) and specific training programs (65.4%). Tools included decision algorithms, clinical practice guidelines, consensus protocols, and software for anatomical, feasibility, and comorbidity assessment. Specific training and periodic multidisciplinary meetings were also in place.

Most centers (76.9%) conducted periodic evaluations of outcomes—described as continuous process evaluation—to optimize procedures, including registries, internal audits, analysis of complications, in-hospital mortality, and readmissions. Annual and monthly clinical meetings allowed protocol adjustments and improved care processes, with high adherence to international clinical practice guidelines.

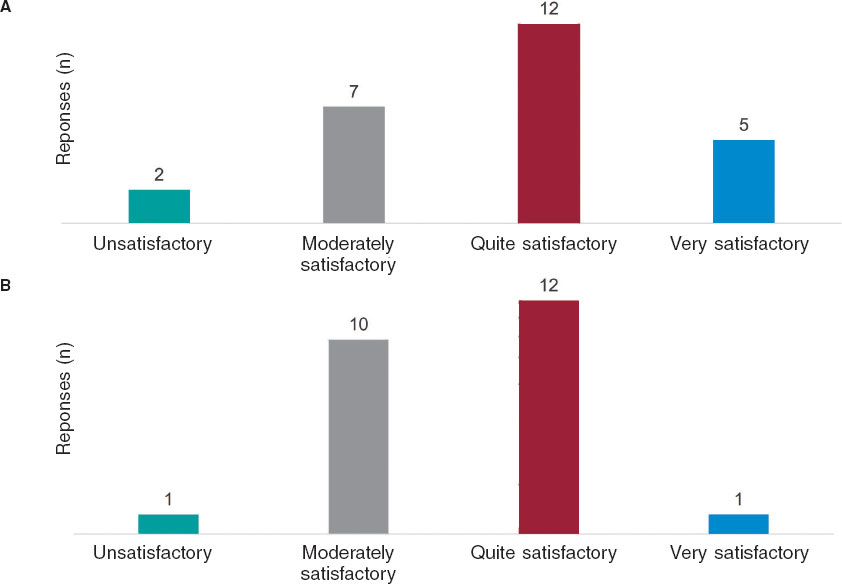

On the other hand, respondents indicated limited satisfaction with information exchange among departments and specialists involved in TAVI decision-making (figure 2A).

Figure 2. A: respondents’ evaluation of information exchange across departments, committees, and professionals involved in decision-making for aortic valve replacement. B: respondents’ evaluation of information exchange and best practices across centers performing transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Spain.

The survey on patient profiles treated with TAVI, which is performed primarily in intermediate- and high-risk patients, showed that 96.2% of centers treat high-risk patients; 76.9%, intermediate-risk patients; and only 30.8%, low-risk patients. In general, although no major barriers to treatment based on risk profile were reported (69.3% responded negatively), some resistance from cardiac surgery (n = 5), disagreement with institutional protocols (n = 4), and infrastructure limitations expressed as restricted availability of cath labs (n = 3) were noted.

Similarly, respondents perceived that the professional background of team members influences clinical decision-making for TAVI (63.6% strongly agreed and 27.3% moderately agreed; n = 11), highlighting the importance of training, experience, and individual performance. Multidisciplinary, consensus-based decisions among specialists in clinical cardiology, imaging, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery allow for the consideration of specific anatomic and clinical factors. Although such multidisciplinary teams promote more objective decision-making, participation from cardiac surgery may affect the indication in low-risk patients.

Therefore, participants considered the heart team’s judgment on additional factors in the indication for TAVI to be relevant, rating it as fairly (50%) or very relevant (50%). Similarly, respondents reported overall satisfaction with the process by which clinical decisions were made within the team: 53.8% found it fairly satisfactory; 38.5%, very satisfactory; 7.7%, moderately satisfactory.

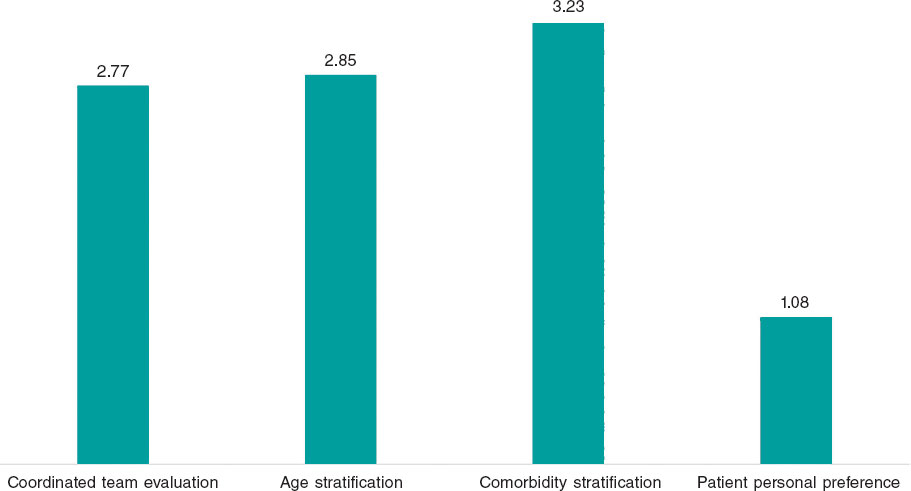

There was near-unanimous agreement (96%) on the importance of incorporating the patient’s opinion into the decision-making process for TAVI indication. When ranking the key factors guiding clinical decision-making, comorbidity and age stratification were rated as the most relevant (figure 3).

Figure 3. Weighted average of responses ranking factors by relevance in the clinical decision to indicate transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

The leading criteria for inclusion on the TAVI waiting list were the presence of comorbidities (n = 22), clinical status or overall risk (n = 20), followed by the minimum (n = 17) and maximum age threshold (n = 2).

The mean waiting time for the procedure was approximately 2 months (mean, 1.92 months; range, 0–4 months). Compared with surgical aortic valve replacement, the waiting list was generally perceived as shorter (50.0%) or equivalent (26.9%).

The primary factors influencing waiting time for TAVI were the need for computed tomography (n = 7) and cath lab availability (n = 5). Other factors included computed tomography availability (n = 3), anesthesia availability (n = 3), and waiting list length (n = 2). In line with this, respondents indicated that most patients (88.5%) undergo TAVI as scheduled procedures

Center evaluation and TAVI use

Most respondents considered the number of centers performing TAVI in Spain sufficient (n = 18, 24 respondents) and highlighted the importance of ensuring adequate procedural volume per center to optimize outcomes and minimize complications. Strengthening infrastructure, human resources, and networking was considered essential, prioritizing quality and safety over opening new centers.

Likewise, participants were generally satisfied with the exchange of information and best practices among TAVI centers in Spain (figure 2B).

There was consensus that improving the early detection of AS would, in turn, improve outcomes and patient experience (91.7%; n = 24). Conversely, most considered that regulatory thresholds for accrediting centers would not substantially affect total TAVI volume (62.5%; n = 24).

Finally, participants shared additional considerations. They emphasized prioritizing safety and clinical outcomes in TAVI programs beyond simply increasing the number of available centers. Although concentration of procedures in high-volume centers was suggested to improve health outcomes, it could also reduce the total number of procedures. The need for audits and dissemination of risk-adjusted results was highlighted to ensure transparency and care quality. Lastly, concern was expressed about the impact of health system fragmentation on equity of access.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms the upward trend in TAVI implantation in Spain, which is consistent with previous research.5,22 From 2016 through 2023, the number of procedures increased in all AC, reflecting broader acceptance of this technique within the SNS. This trend is attributed to the consolidation of TAVI as a reference therapeutic alternative for the treatment of severe symptomatic AS, progressively expanding from high-risk to intermediate- and low-risk patients.12-14

Despite this generalized increase, results show notable interregional variability in TAVI rates. In 2023, some AC reported procedural rates well above the national average, while others were considerably lower. This inequality has been documented previously and suggests a key role for organizational factors in determining access to the procedure.21 Of note, in regions such as La Rioja, the absence of local cardiac surgery centers may partly explain the low number of TAVI. However, this does not mean that patients are not treated; rather procedures are performed in neighboring AC.

From a clinical perspective, multiple studies have shown that TAVI reduces in-hospital mortality, improves quality of life, and decreases the rate of major complications.16-20 Although these outcomes were not directly assessed in the present study, former studies have identified a relationship between higher procedural volume and improved outcomes, including reduced infection risk, decreased pacemaker need, and a shorter length of stay.5 Our analysis does not allow a direct correlation to be established between procedural volume and quality of care in Spain. This suggests that, although cumulative experience is a determinant of improved outcomes, other organizational and resource-management factors may also contribute to the observed discrepancies. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that as TAVI volume increases, the variability in mortality outcomes tends to diminish, suggesting greater standardization of practice and reduced variability across more experienced centers.

The survey analysis revealed that TAVI indication in Spain continues to depend primarily on physician judgment and patient risk stratification, with less influence from patient preference or resource availability. These findings are consistent with former studies underscoring the importance of multidisciplinary clinical judgment in decision-making, which results in patient selection aligned with clinical practice guidelines and safety criteria.27 However, organizational barriers hindering the expansion of TAVI were identified, including rigid patient stratification, insufficient identification of candidates, and difficulties integrating heart teams. Such limitations have previously been recognized as determinants of inequality in TAVI access in Spain,21 reinforcing the need for strategies to optimize care.

From a financial perspective, TAVI has been shown to be cost-effective compared with conventional surgical aortic valve replacement across various clinical scenarios.15,28 In our study, however, participants did not identify financing as a major barrier to expansion. This finding is consistent with prior Spanish investigations, which found no clear correlation between regional health spending and TAVI rates,5,21 suggesting that variability is more strongly influenced by organizational rather than economic factors.

The perception of infrastructure is relevant too, as most respondents considered the number of centers performing TAVI in Spain sufficient, while emphasizing the importance of guaranteeing a minimum procedural volume per center to optimize outcomes and minimize complications. Former studies have highlighted that cumulative team experience can improve clinical outcomes.27 However, no consensus was reached in this study on whether concentrating procedures in a smaller number of centers would favor equity of access or, conversely, limit availability in regions with restricted supply.

With respect to continuity of care, both advances and opportunities for improvement were identified. While > 90% of specialists positively evaluated the implementation of teleconsultation, specialized nursing programs (TAVI Nurse26), and shared protocols across levels of care, participants also emphasized the need to strengthen coordination between primary and specialized care, improve clinical information systems, and optimize scheduling management. These aspects have previously been highlighted as important for improving the efficiency of TAVI care processes5 and identified as cross-cutting priorities in the 2022 report of the SNS, Estrategia en Salud Cardiovascular.29

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, although the analysis of the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data provides information on overall TAVI trends, the Spanish Ministry of Health’s statistical portal does not include detailed patient-level clinical data, thus preventing assessment of outcomes such as complications.

Second, although the survey was designed to achieve representation from all AC, responses were obtained from only 11 of them (26 of 123 [21%] affiliated centers of the Interventional Cardiology Association), meaning that the perceptions and experiences reflected are drawn from a subset of regions, which may influence interpretation of certain findings. Nevertheless, this limitation is inherent to survey-based research, as participation greatly depends on availability and willingness of respondents. Despite this, the sample offers a representative perspective on organizational and clinical factors influencing variability in TAVI access within the SNS.

Finally, sex and gender variables were not considered in accordance with the SAGER guidelines, as the focus was on regional differences across AC. Future studies should explore sex- and gender-related influences on TAVI implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings reflect sustained growth in TAVI implementation in Spain, alongside marked interregional variability in procedural rates. Patient selection is driven primarily by physician judgment and clinical risk, while barriers to expansion are more organizational than financial. Key strategies are suggested to reduce regional variability and ensure equitable TAVI access within the SNS, including improved coordination across different levels of care, standardization of selection criteria, and strengthened resource management.

FUNDING

This work was funded by Edwards Lifesciences.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Approval from the study ethics committee was deemed unnecessary, as it used administrative data from the Spanish Ministry of Health without accessing patient-level data. Similarly, informed consent was deemed unnecessary. Sex and gender variables were not analyzed in accordance with the SAGER guidelines, as the study focused on regional differences across AC.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used in this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the study design. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo requested the data and implemented the web-based survey. O. Martínez-Pérez conducted data analysis. All authors reviewed and validated the results. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.M. de la Torre-Hernández is editor-in-chief of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo work for Axentiva Solutions S.L., a consultancy providing services to various pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Research Agency and Scientific Department of the Spanish Society of Cardiology for their support in project management and securing funding. Their collaboration was essential to the planning and execution of this study, enabling data analysis and evaluation of regional variability in TAVI implementation in Spain.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- TAVI has revolutionized the treatment of severe AS, becoming a first-line option in high- and intermediate-risk patients. It has demonstrated advantages over conventional surgery, including reduced mortality, a shorter length of stay, and improved quality of life. In Spain, TAVI use has grown unevenly across AC, influenced not only by economic factors but also by organizational and structural differences in patient selection criteria and resource availability. However, the impact of this variability on clinical outcomes and equity of access remains unclear.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study provides a comprehensive analysis of interregional variability in TAVI implementation in Spain, combining the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set with a specialist survey. Compared with former studies, it not only identifies differences in implementation rates across AC but also organizational, structural, and care-related barriers influencing access. Furthermore, it evaluates professional perceptions of team composition in clinical decision-making and challenges in continuity of care. These findings improve understanding of the determinants of heterogeneity in TAVI access and offer recommendations to enhance equity of implementation within the SNS. Results may be key for health policy planning and the design of strategies to optimize resource allocation and ensure more uniform access to this technology.

REFERENCES

1. Ferreira-González I, Pinar-Sopena J, Ribera A, et al. Prevalence of calcific aortic valve disease in the elderly and associated risk factors:a popula- tion-based study in a Mediterranean area.

2. Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical Factors Associated With Calcific Aortic Valve Disease.

3. Salinas P, Moreno R, Calvo L, et al. Long-term Follow-up After Transcath- eter Aortic Valve Implantation for Severe Aortic Stenosis.

4. Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of Aortic-Valve Sclerosis with Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity in the Elderly.

5. Íñiguez-Romo A, Zueco-Gil JJ, Álvarez-BartoloméM, et al. Outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Spain through the Activity Registry of Specialized Health Care.

6. Ramaraj R, Sorrell VL. Degenerative aortic stenosis.

7. Van Hemelrijck M, Taramasso M, De Carlo C, et al. Recent advances in understanding and managing aortic stenosis.

8. Maldonado Y, Baisden J, Villablanca PA, Weiner MM, Ramakrishna H. General Anesthesia Versus Conscious Sedation for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement —An Analysis of Current Outcome Data.

9. Perrin N, Frei A, Noble S. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation:Update in 2018.

10. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implanta- tion for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery.

11. Duncan A, Ludman P, Banya W, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Tran- scatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in High-Risk Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis.

12. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease.

13. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients.

14. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replace- ment with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients.

15. Pinar E, de Lara JG, Hurtado J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the SAPIEN 3 transcatheter aortic valve implant in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis.

16. Tamm AR, Jobst ML, Geyer M, et al. Quality of life in patients with transcatheter aortic valve implantation:an analysis from the INTERVENT project.

17. Nuland PJA, van Ginkel DJ, Overduin DC, et al. The impact of stroke and bleeding on mortality and quality of life during the first year after TAVI:A POPular TAVI subanalysis.

18. Zhang S, Kolominsky-Rabas PL. How TAVI registries report clinical outcomes —A systematic review of endpoints based on VARC-2 definitions.

19. Gargiulo G, Sannino A, Capodanno D, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement.

20. Sehatzadeh S, Doble B, Xie F, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for treatment of aortic valve stenosis:an evidence update.

21. la Torre Hernández JM, Lozano González M, García Camarero T, et al. Interregional variability in the use of cardiovascular technologies (2011- 2019). Correlation with economic indicators, admissions, and in-hospital mortality.

22. Biagioni C, Tirado-Conte G, Nombela-Franco L, et al. Situación actual del implante transcatéter de válvula aórtica en España.

23. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Actividad de Atención Especializada, Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos. Available at:https://www.sanidad. gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/cmbdhome.htm. Accessed 8 Apr 2024.

24. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Actividad de Atención Sanitaria Espe- cializada (RAE-CMBD). Actividad y resultados de la hospitalización en el SNS. Año 2022. Madrid:Ministerio de Sanidad;2024. Available at:https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/RAE-CMBD_Informe_Hospitalizacion_2022.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2025.

25. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Atención Sanitaria Especializada RAE-CMBD. Manual de Usuario y Glosario de Términos. Portal Estadístico;2023. Available at:https://pestadistico.inteligenciadegestion.sanidad.gob. es/publicoSNS/D/rae-cmbd/rae-cmbd/manual-de-usuario/manual-de-usuario- rae. Accessed 29 May 2025.

26. González Cebrián M, Valverde Bernal J, Bajo Arambarri E, et al. Docu- mento de consenso de la figura TAVI Nurse del Grupo de Trabajo de Hemodinámica de la Asociación Española de Enfermería en Cardiología.

27. Carnero-Alcázar M, Maroto-Castellanos LC, Hernández-Vaquero D, et al. Isolated aortic valve replacement in Spain:national trends in risks, valve types, and mortality from 1998 2017.

28. Baron SJ, Magnuson EA, Lu M, et al. Health Status After Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients With Aortic Stenosis.

29. Ministerio de Sanidad. Estrategia en Salud Cardiovascular del Sistema Nacional de Salud (ESCAV). 2022. Available at:https://www.sanidad.gob. es/areas/calidadAsistencial/estrategias/saludCardiovascular/docs/Estrategia_de_salud_cardiovascular_SNS.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2025.

ABSTRACT

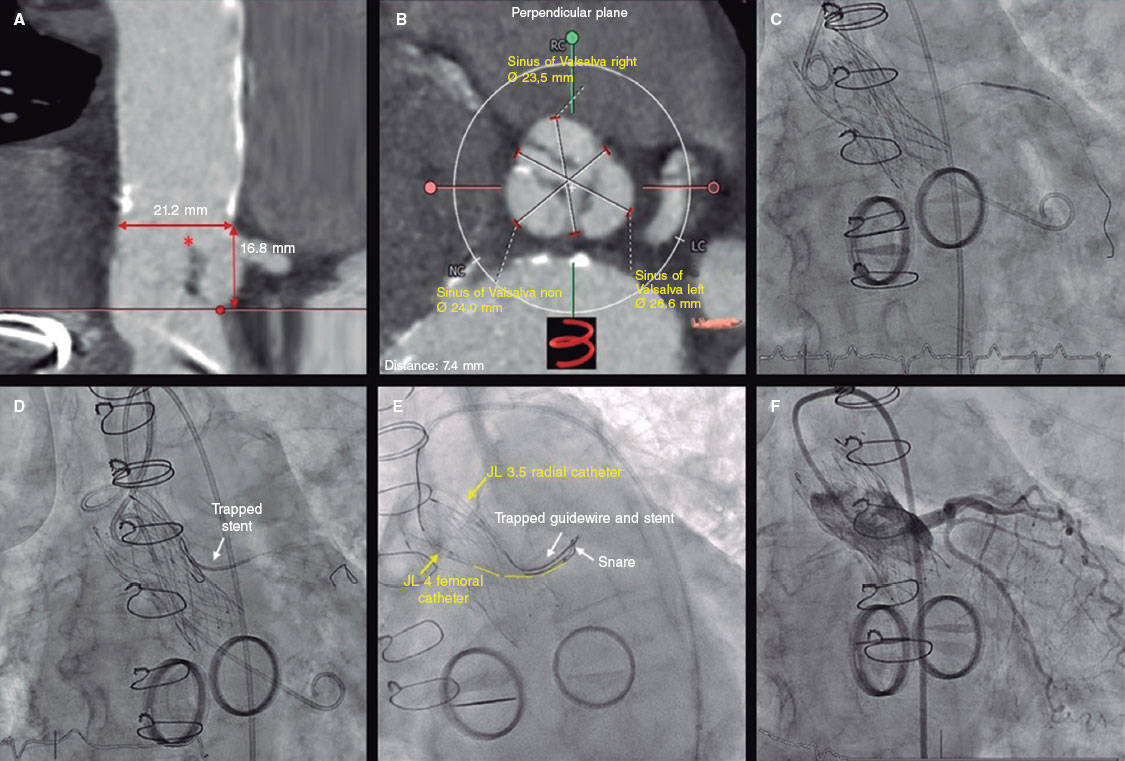

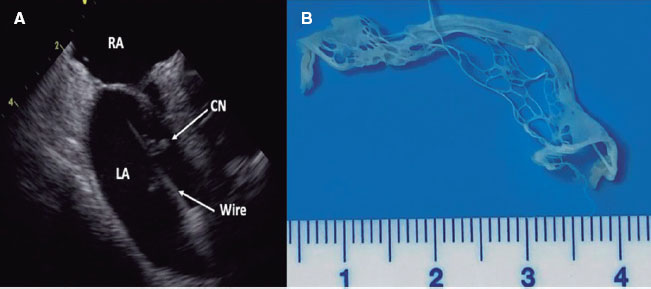

Introduction and objectives: Thrombus removal in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can be challenging in the presence of a large thrombus burden. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA) is an adjuvant device capable of vaporizing thrombus. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in PCI.

Methods: Patients with STEMI undergoing PCI with concomitant use of ELCA for thrombus removal were retrospectively identified at our center. Data were collected on the device efficacy and its contribution to overall procedural success. Additionally, ELCA-related complications and major adverse cardiovascular events were recorded at a 2-year follow-up.

Results: ELCA was used in 130 STEMI patients, 124 (95.4%) of whom had a large thrombus burden. TIMI grade flow improved significantly after ELCA: before laser application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases and TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%) cases. After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively (P < .001). Technical and procedural success were achieved in 128 (98.5%) and 124 (95.4%) cases, respectively. The complications included 1 death at the cath lab (0.8%), 1 coronary perforation (0.8%), and 3 distal embolizations (2.3%). At the 2-years follow-up, major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 18.3% of the population.

Conclusions: In the context of STEMI, ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution, with adequate technical and procedural success rates. In the present cohort, ELCA use was associated with a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. Thrombectomy. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La eliminación de trombos durante la intervención coronaria percutánea primaria (ICPp) en el infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST) es un desafío en presencia de una carga trombótica elevada. La angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros (ELCA) es una técnica complementaria que permite vaporizar el trombo. Este estudio evaluó la eficacia y la seguridad de la ELCA en el contexto de la ICPp.

Métodos: Análisis retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes con IAMCEST sometidos a ICPp con ELCA. Se evaluaron la eficacia en la disolución del trombo, la mejoría del flujo, el éxito del procedimiento, las complicaciones asociadas y los acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores durante un seguimiento de 2 años.

Resultados: Se realizó ELCA en 130 pacientes con IAMCEST, de los cuales 124 (95,4%) tenían carga trombótica elevada. El flujo TIMI mejoró significativamente tras la ELCA: previamente era 0 en 79 casos (60,8%) y 1 en 32 casos (24,6%), y se lograron flujos TIMI 2 y 3 en 45 casos (34,6%) y 66 casos (50,8%), respectivamente (p < 0,001). Las tasas de éxito técnico y del procedimiento fueron del 98,5% y el 95,4%, respectivamente. Las complicaciones incluyeron 1 muerte intraprocedimiento (0,8%), 1 perforación coronaria (0,8%) y 3 embolizaciones distales (2,3%). A los 2 años, la tasa de acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores fue del 18,3%.

Conclusiones: La ELCA parece ser una técnica eficaz y segura en el IAMCEST para la disolución del trombo, con altas tasas de éxito técnico y procedimental, baja incidencia de complicaciones y resultados favorables a largo plazo.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. Trombectomía. Angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros.

Abbreviations

ELCA: excimer laser coronary angioplasty. LTB: large thrombus burden. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

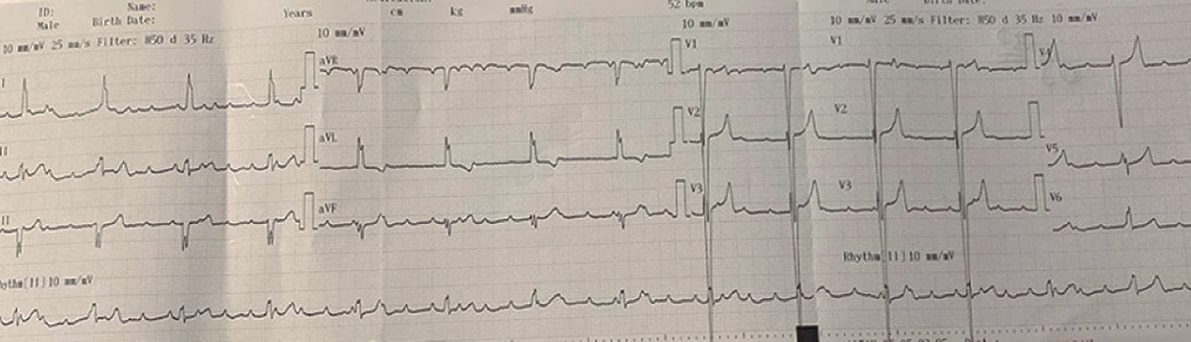

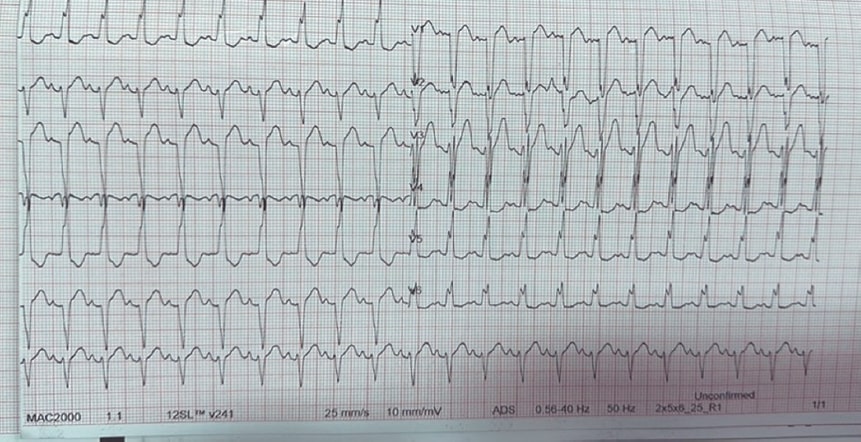

INTRODUCTION

In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy, as long as it can be performed within 120 minutes of the electrocardiogram-based diagnosis.1 Many patients with STEMI present with thrombotic occlusion of the infarct-related artery. Therefore, the use of devices aimed at reducing thrombus burden is a reasonable consideration to minimize distal embolization and no-reflow. Persistent no-reflow in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI is associated with the worst in-hospital outcomes and increased long-term mortality.2

While early studies on manual thrombus aspiration suggested benefits in terms of improved myocardial blush grades and ST-segment elevation resolution,3 larger trials comparing manual thrombus aspiration with PCI alone showed no significant reduction in cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, or a New York Heart Association FC IV heart failure within 180 days.4 Consequently, routine aspiration thrombectomy is no longer recommended in patients with STEMI.5

Thrombus removal, particularly when dealing with a large thrombus burden (LTB) in the context of STEMI, remains a critical and sometimes challenging aspect of PCI. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA Coronary Laser Atherectomy Catheter, Koninklijke Philips N.V., The Netherlands) is a well-established adjuvant therapy for coronary interventions. ELCA uses xenon-chloride gas as the lasing medium to produce UV light energy, which is delivered to the target site through an optical fiber. This energy has the ability to ablate inorganic material through photochemical, photothermal, and photomechanical mechanisms.6,7 The microparticles released during laser ablation measure < 10 µm and are absorbed by the reticuloendothelial system, theoretically reducing the risk of microvasculature obstruction.8 These unique characteristics of ELCA have facilitated its use as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI to ablate and remove thrombus.

Although ELCA is part of the therapeutic armamentarium in some PCI-capable centers, literature data is limited on its safety and efficacy profile in this specific scenario. The aim of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ELCA, focusing on its safety and efficacy profile as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI in our center.

METHODS

Data from all patients undergoing PCI with the simultaneous use of ELCA as an adjuvant technique were retrospectively recorded in a dedicated database after each procedure, starting from the introduction of the device in our center. ELCA procedures were performed by 5 interventional cardiologists with dedicated training in the use of the device.

This study was approved by Parque Sanitario Pere Virgili ethics committee (Barcelona, Spain) (reference No.: CEIM 003/2025). For the purposes of this study, we selected the subgroup of patients with STEMI who underwent PCI in which ELCA was used to facilitate thrombus removal.

Thrombus burden was assessed using the thrombus grading classification9 as defined by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) study group, ranging from 0 to 5. A LTB was defined as a thrombus score ≥ 3. According to our internal protocol, ELCA was considered in STEMI patients in the presence of angiographic evidence of LTB, defined as TIMI thrombus grade ≥ 3, particularly if TIMI grade-0–1 flow or, poor visualization of the distal vessel, or as a bailout strategy after unsuccessful manual thrombectomy. Clinical variables were meticulously refined, and follow-up details were obtained through a thorough review of the patients’ health records. Following coronary angiography and successful guidewire crossing of the culprit lesion, ELCA was left at the operator’s discretion. It was used either as a primary device for thrombus removal or as a bailout strategy when manual thrombus aspiration did not improve TIMI grade flow. The selection of catheter size was mainly based on the target vessel diameter and on the characteristics of the vessel and the lesion; a 0.9 mm ELCA catheter is usually used in tortuous anatomies due to its better navigability and in small-caliber vessels, whereas a 1.4 mm catheter is used in selected cases involving larger proximal vessels with straight segments. Catheter size (0.9 mm or 1.4 mm) was selected based on vessel diameter and lesion characteristics. Laser fluence (45-60 mJ/mm²) and pulse repetition rate (25-40 Hz) were chosen as per manufacturer’s recommendations.

Before laser application, the target vessel was flushed with saline solution to prevent interaction between the laser and blood or contrast medium. In all cases, continuous saline infusion was administered during laser delivery to avoid coronary artery wall heating. Laser energy was delivered using an ‘on-off’ technique, consisting of 10-s laser activation cycles interspersed with 5-s pauses. The laser catheter was advanced at a rate of approximately 1 mm/s over a 0.014-in coronary guidewire through the target lesion, following the manufacturer’s recommendations.7,10 After 2–3 laser catheter passes, a follow-up coronary angiography was performed to evaluate the efficacy of laser application and assess the feasibility of stent implantation. TIMI grade flow was recorded after the ELCA procedure (Post-ELCA TIMI grade flow) and once the PCI would have been completed (final TIMI grade flow). Technical success was defined as the ability to advance the laser catheter through the entire target lesion and deliver laser energy successfully. Procedural success was defined as achieving a final TIMI grade ≥ 2 flow without any major cath lab-related complications, such as death, coronary perforation, or emergency bypass surgery after PCI completion. All procedural complications, including death, coronary perforation,11 emergency bypass surgery, distal embolization, ventricular arrhythmia, and no-reflow were carefully documented and reported. Follow-up was conducted via retrospective review of health records, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) defined as a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, new myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularization were recorded at the follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Inter-group comparisons were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

The composite endpoint of MACE was analyzed as time-to-event data at the follow-up. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate the event-free survival rates. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 23.0, IBM Corp., United States). A 2-tailed P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between July 2015 and August 2024, a total of 130 PCI s were performed in patients with STEMI using ELCA as an adjuvant therapy for thrombus removal. The patients’ mean age was 61.8 ± 11.7 years, with 18 (13.8%) being women and 18 (13.8%) diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. ELCA was employed as the primary device for thrombus dissolution in 66 cases (50.8%) and as a bailout strategy in 64 cases (49.2%). Within the bailout group, manual thrombus aspiration was performed in 47 cases (36.2%), balloon dilation in 6 cases (4.6%), and thrombus debulking using the dotter effect in 11 cases (8.5%).

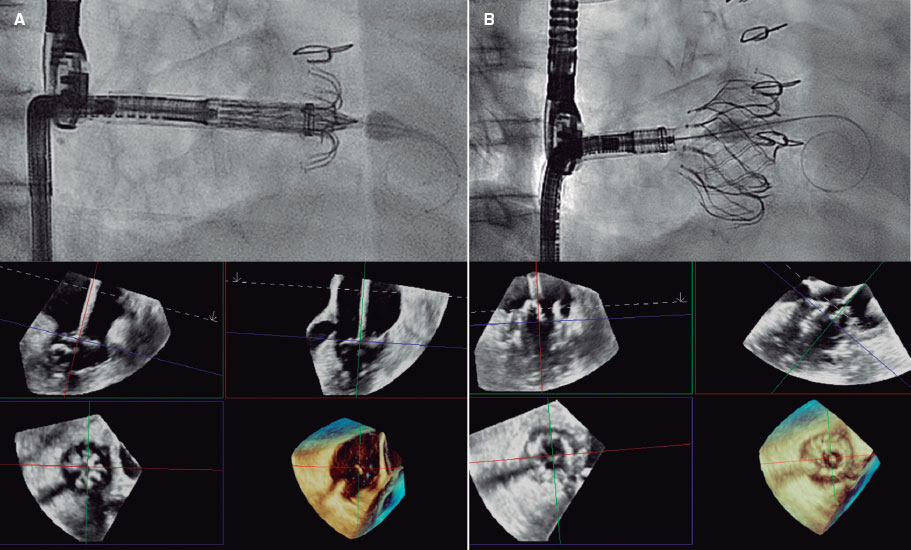

In the overall cohort, 124 patients (95.4%) presented with culprit lesions with a LTB. Before laser energy application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%). After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively; P < .001 (figure 1).

Figure 1. TIMI grade flow distribution before and after ELCA application. Stacked bar graph showing the distribution of TIMI grade 0-3 flows at 3 different time points: initial angiography, post-ELCA, and final angiographic result after PCI. A marked improvement in coronary flow is observed following ELCA, with a progressive increase in TIMI grade-3 flow from 6.2% to 74.6%. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Technical success was achieved in 128 (98.5%) cases, and procedural success in 124 (95.4%) (table 1). Procedural success was significantly higher when ELCA was used as the initial strategy vs when it was used as the bailout strategy (100% vs 90.6%; P = .013). However, procedural time was significantly longer in the bailout vs the initial strategy group (69.81 vs 48.50 min, respectively) (table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| Variable (n = 130) | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 61.8 ± 11.7 |

| Female | 18 (13.8) |

| Hypertension | 59 (45,4%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 57 (43,8%) |

| Tobacco use | 78 (60%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (13.8) |

| Killip classification | |

| I | 98 (75.4) |

| II | 18 (13.8) |

| III | 3 (2.3) |

| IV | 11 (8.5) |

| Radial access | 118 (90,7%) |

| Femoral access | 12 (9,3%) |

| Lesion localization | |

| LMCA | 3 (2,3%) |

| LAD | 55 (42,3%) |

| LCX | 8 (6,2%) |

| RCA | 64 (49,2 %) |

| Primary device | 66 (50.8) |

| Bailout strategy | 64 (49.2) |

| Large thrombus burden | 124 (95.4) |

| Laser catheter size, Fr | |

| 0.9 | 114 (87.7) |

| 1.4 | 16 (12.3%) |

| Procedural time, min | 60 (43–86) |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 22.2 ±12.2 |

| Laser frequency, Hz | 31 ± 10.4 |

| Laser fluency, mJ/mm2 | 46.5 ± 9.17 |

| Laser delivery time, s | 125.9 ± 83.4 |

| Technical success | 128 (98.5) |

| Procedural success | 124 (95.4) |

|

LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX: left circumflex artery; LMCA: left main coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|

Table 2. Difference in variables between the initial and bailout strategy groups

| Variable | ELCA as the initial strategy (n = 66) | ELCA as the bailout strategy (n = 64) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 8 (12.1%) | 3 (4.7%) | .100 |

| Large thrombus burden | 64 (97%) | 60 (93.8%) | .440 |

| Technical success | 65 (98.5%) | 63 (98.4%) | 1.000 |

| Procedural success | 66 (100%) | 58 (90.6%) | .013 |

| Procedural time, median | 48.50 (38.83–66.61) | 69.81 (55.36–101) | < .001 |

|

ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|||

One case of type IV coronary perforation, according to the modified Ellis classification, occurred in an octogenarian patient with an ecstatic and tortuous right coronary artery. Perforation sealing was achieved with the implantation of a covered stent. One cath lab-related death occurred in a patient with an uncrossable mid-segment of a left anterior descending coronary artery lesion and initial TIMI grade-3 flow. Following balloon dilation and partial advancement of the laser probe, complete vessel occlusion and suspected left main coronary artery dissection resulted in cardiac arrest and cath lab-related death.

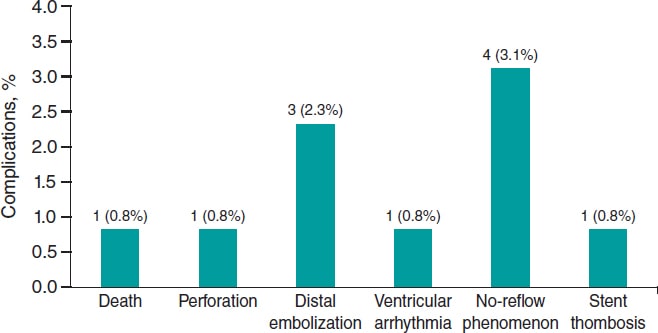

Other procedural complications included distal embolization in 3 (2.3%) cases and slow flow or no-reflow in 4 (3.1%). Among the slow/no-reflow cases, 1 occurred after laser application, and 3 following stent implantation and/or post-dilation. All were successfully managed with optimal medical therapy, achieving final TIMI grade-2 flow. One episode of ventricular arrhythmia occurred during saline washout of the target vessel, requiring electrical cardioversion. Additionally, 1 case of stent thrombosis (0.8%) occurred intraoperatively (figure 2).

Figure 2. ELCA-related procedural complications. Bar chart showing the frequency and percentage of major complications during or immediately after ELCA. The most common was no-reflow (3.1%), followed by distal embolization (2.3%). Other events (death, perforation, ventricular arrhythmia, and stent thrombosis) were rare (0.8% each). ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

Long-term follow-up data were missing for 6 patients (4.6%). At the 2-year follow-up, the event-free rate for combined MACE was 0.80 (95%CI, 0.73–0.88) as determined by the Kaplan–Meier estimator (table 3 and figure 3).

Table 3. List of adverse clinical events

| Patient No. | Event | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Death | 1 |

| 13 | Death | 493 |

| 15 | Death | 148 |

| 23 | Death | 11 |

| 33 | Death | 170 |

| 36 | Death | 4 |

| 43 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 39 |

| 50 | New myocardial infarction | 213 |

| 61 | Death | 16 |

| 77 | Death | 1 |

| 83 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 119 |

| 84 | Death | 4 |

| 92 | Death | 1 |

| 98 | Death | 0 |

| 101 | Death | 37 |

| 110 | Death | 0 |

| 113 | Death | 12 |

| 118 | Death | 253 |

| 121 | Death | 139 |

| 124 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 291 |

| 128 | Death | 10 |

|

TLR, target lesion revascularization. Lost to follow-up: 6 patients (4.6%). |

||

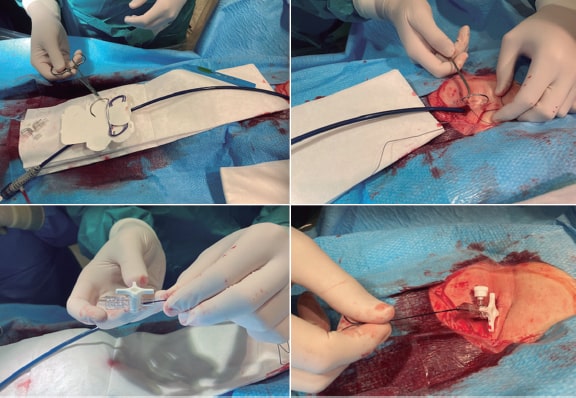

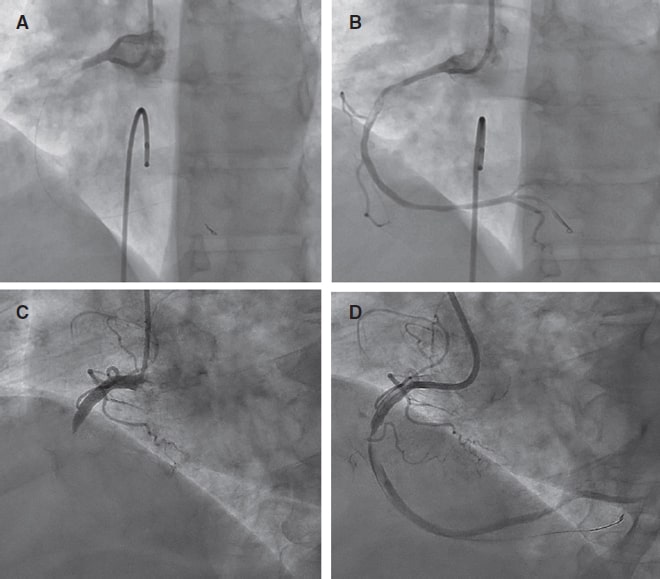

Figure 3. Pre- and post-ELCA findings in 2 typical cases of right coronary artery with large thrombus burden. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this single-center study is that coronary laser angioplasty is a feasible, safe, and effective adjuvant therapy in the context of PCI (videos 1-4 of the supplementary data), demonstrating a low rate of complications and an acceptable long-term rate of MACE.

Data on the use of ELCA in acute myocardial infarction remain limited, with most evidence coming from non-randomized clinical trials. The CARMEL trial,12 the largest multicenter study to date, evaluated the safety, feasibility, and acute outcomes of ELCA in patients with acute myocardial infarction within 24 h of symptom onset requiring urgent PCI. TIMI grade flow significantly improved after laser application, increasing from 1.2 to 2.8, with an overall procedural success rate of 91% and a low distal embolization rate of 2%, even though 65% of cases had a LTB. In our study, 95.4% of the patients had culprit lesions with a LTB, and laser delivery significantly improved the mean TIMI grade flow from 0.6 to 2.29, with a comparable distal embolization rate of 2.3%.

Arai et al.13 retrospectively analyzed 113 consecutive acute coronary syndrome cases undergoing PCI comparing an ELCA group (n = 48) with a thrombus aspiration group (n = 50). They found that ELCA was associated with a significantly shorter door-to-reperfusion time, a better myocardial blush grade, and fewer MACE vs thrombus aspiration. These favorable outcomes are likely attributable to ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi through acoustic shockwave propagation and dissolution mechanisms,12 as well as its capacity to suppress platelet aggregation kinetics (a phenomenon known as the ‘stunned platelet’ effect).14

Reperfusion injury to the coronary microcirculation is a critical concern during PCI in STEMI patients. While manual thrombus aspiration can reduce the rate of no-reflow in patients with a LTB, residual thrombi and decreased coronary flow following thrombectomy have been associated with a higher risk of no-reflow.15 In a study of 812 patients with STEMI and a LTB undergoing PCI, Jeon et al.16 reported that 34.4% experienced failed thrombus aspiration, defined as no thrombus retrieval, remnant thrombus grade ≥ 2, or distal embolization. This failure was associated with an increased risk of impaired myocardial perfusion and microvascular obstruction.

ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi (with a low rate of distal embolization) and mitigate platelet activation, key cofactors in myocardial reperfusion damage,17 can potentially reduce this undesirable effect. Although the direct impact of ELCA on coronary microcirculation in PCI has not been well documented, evidence from smaller studies suggests potential benefits. For example, Ambrosini et al.18 investigated ELCA in 66 patients with acute myocardial infarction and complete thrombotic occlusion of the infarcted related artery, demonstrating excellent acute coronary and myocardial reperfusion outcomes (as assessed by the myocardial blush score and the corrected TIMI frame count), as well as a low rate of long-term left ventricular remodeling (8%). The significant improvement in mean TIMI grade flow observed immediately after ELCA application in our cohort may indirectly suggest a protective effect of this technique on coronary microcirculation. However, the lack of large studies comparing ELCA with conventional STEMI treatment limits the ability to definitively confirm the benefits of coronary laser therapy in this setting. Shibata et al.19 explored the impact of ELCA on myocardial salvage using nuclear scintigraphy in 72 STEMI patients and an onset-to-balloon time < 6 h, comparing ELCA (n = 32) and non-ELCA (n = 40) groups. Their findings indicated a trend towards a higher myocardial salvage index in the ELCA vs the non-ELCA group (57.6% vs 45.6%).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It is a retrospective analysis, which inherently introduces biases related to data collection, interpretation and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Besides, the absence of a comparative group limits the ability to establish the definitive clinical benefit of ELCA and its potential superiority over other strategies in the context of STEMI patients undergoing PCI. Furthermore, while the significant improvement of TIMI grade flow observed after laser application suggests potential benefits for coronary microcirculation, we did not directly assess this effect or thrombus burden reduction since post-ELCA thrombus grading was not systematically recorded. Unfortunately, in our retrospective database, PCI details (segmental analysis of coronary arteries and classification), the use of intravascular imaging modalities, dual antiplatelet therapy regimens (aspirin in addition to a potent P2Y12 inhibitor, or clopidogrel when prasugrel or ticagrelor were contraindicated, was routinely prescribed following current guidelines recommendations) or post-PCI echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance parameters were not systematically collected (unavailable in the health reports we revised) and follow-up data were missing for 4.6% of patients, all of which limited our ability to assess their potential impact on clinical outcomes. Last, our findings represent the experience of a single center, the percentage of women and patients with diabetes is relatively low, and procedures were performed by 5 trained operators, which may limit the external validity of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution in the STEMI scenario, with excellent technical and procedural success rates. Besides, a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes with an acceptable event-free survival rate was observed in the present cohort.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the center Ethics Committee (waiving the need for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the investigation) in full compliance with national legislation and the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Sex was reported as per biological attributes (SAGER guidelines).

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The authors state that no generative artificial intelligence technologies were used in the preparation or revision of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Pernigotti and M. Mohandes were responsible for the conceptualization and study design and contributed equally as co-first authors. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, R. Bejarano, H. Coimbra, F. Fernández, C. Moreno, M. Torres, J. Guarinos were involved in data collection and statistical analysis. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, and J.L. Ferreiro were involved in manuscript drafting and critical revision and were responsible for the supervision and final approval. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal. Each author reviewed all results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. J.L. Ferreiro declared having received speaker’s fees from Eli Lilly Co, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rovi, Terumo and Ferrer; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Co., Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biotronik; and research grants from AstraZeneca, not related to this manuscript.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ELCA is a specialized technique used as adjuvant therapy during PCI for STEMI, particularly in patients with LTB.

- Although former studies have shown that ELCA can improve coronary flow and potentially reduce thrombotic material, data in the setting of acute myocardial infarction remain limited.

- ELCA is mostly used in high-volume centers by experienced operators, and standardized criteria for use in STEMI patients are not consistently reported in the literature.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This is one of the largest retrospective single-center series (130 patients) ever reported on the use of ELCA in STEMI patients with angiographically defined LTB.

- The study shows a high rate of technical and procedural success, significant improvement in TIMI flow, low rate of complication, and acceptable long-term outcomes.

- It provides detailed information on operator training, device selection, and laser settings, contributing to transparency and reproducibility.

- It also identifies current limitations in data reporting (eg, lack of systematic thrombus grading or dual antiplatelet therapy regimen documentation), underscoring the need for standardization in future studies.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 2. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 3. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 4. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

2. Kim MC, Cho JY, Jeong HC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of transient and persistent no reflow phenomena following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:490-498.

3. Sardella G, Mancone M, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves myocardial reperfusion and reduces infarct size:the EXPIRA prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:309-315.

4. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1389-1398.

5. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization:Executive summary. Circulation. 2022;145:e4-e17.

6. Grundfest WS, Litvack F, Forrester JS, et al. Laser ablation of human atherosclerotic plaque without adjacent tissue injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:929-933.

7. Mohandes M, Fernández L, Rojas S, et al. Safety and efficacy of coronary laser ablation as an adjuvant therapy in percutaneous coronary intervention:a single-centre experience. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:241-246.

8. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O'Kane P. Coronary intervention with the excimer laser:review of the technology and outcome data. Interv Cardiol Rev. 2016;11:27-32.

9. Gibson CM, de Lemos JA, Murphy SA, et al. Combination therapy with abciximab reduces angiographically evident thrombus in acute myocardial infarction:a TIMI 14 substudy. Circulation. 2001;103:2550-2554.

10. Topaz O, Das T, Dahm J, et al. Excimer laser revascularisation:current indications, applications and techniques. Lasers Med Sci. 2001;16:72-77.

11. Ellis SG, Ajluni S, Arnold AZ, et al. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-2730.

12. Topaz O, Ebersole D, Das T, et al. Excimer laser angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction (the CARMEL multicenter trial). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:694-701.

13. Arai T, Tsuchiyama T, Inagaki D, et al. Benefits of excimer laser coronary angioplasty over thrombus aspiration therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 0. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;38:13.

14. Topaz O, Minisi AJ, Bernardo NL, et al. Alterations of platelet aggregation kinetics with ultraviolet laser emission:the “stunned platelet“phenomenon. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1087-1093.

15. Ahn SG, Choi HH, Lee JH, et al. The impact of initial and residual thrombus burden on the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26:245-253.

16. Jeon HS, Kim YI, Lee JH, et al. Failed thrombus aspiration and reduced myocardial perfusion in patients with STEMI and large thrombus burden. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:2216-2225.

17. Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA. No-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 2002;105:656-662.

18. Ambrosini V, Cioppa A, Salemme L, et al. Excimer laser in acute myocardial infarction:single centre experience on 66 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:98-102.

19. Shibata N, Takagi K, Morishima I, et al. The impact of the excimer laser on myocardial salvage in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction via nuclear scintigraphy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:161-170.

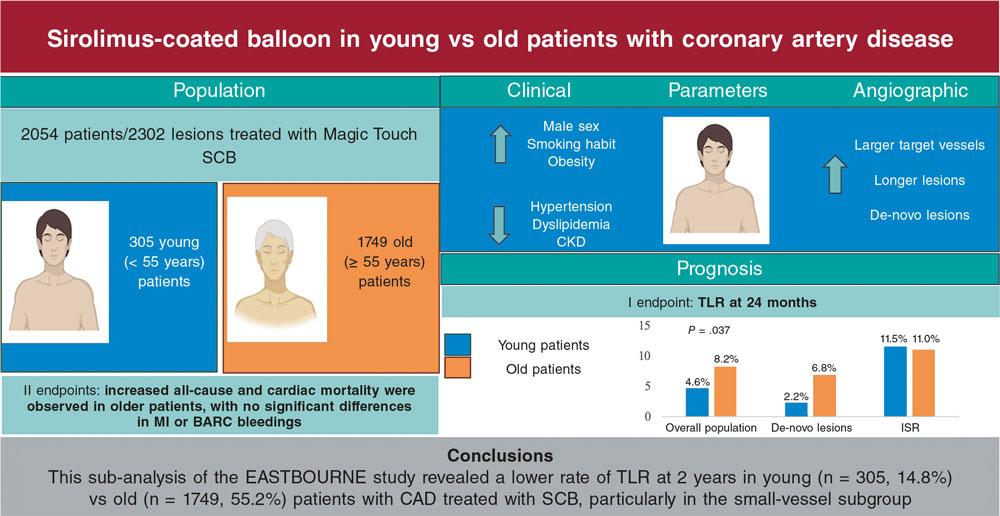

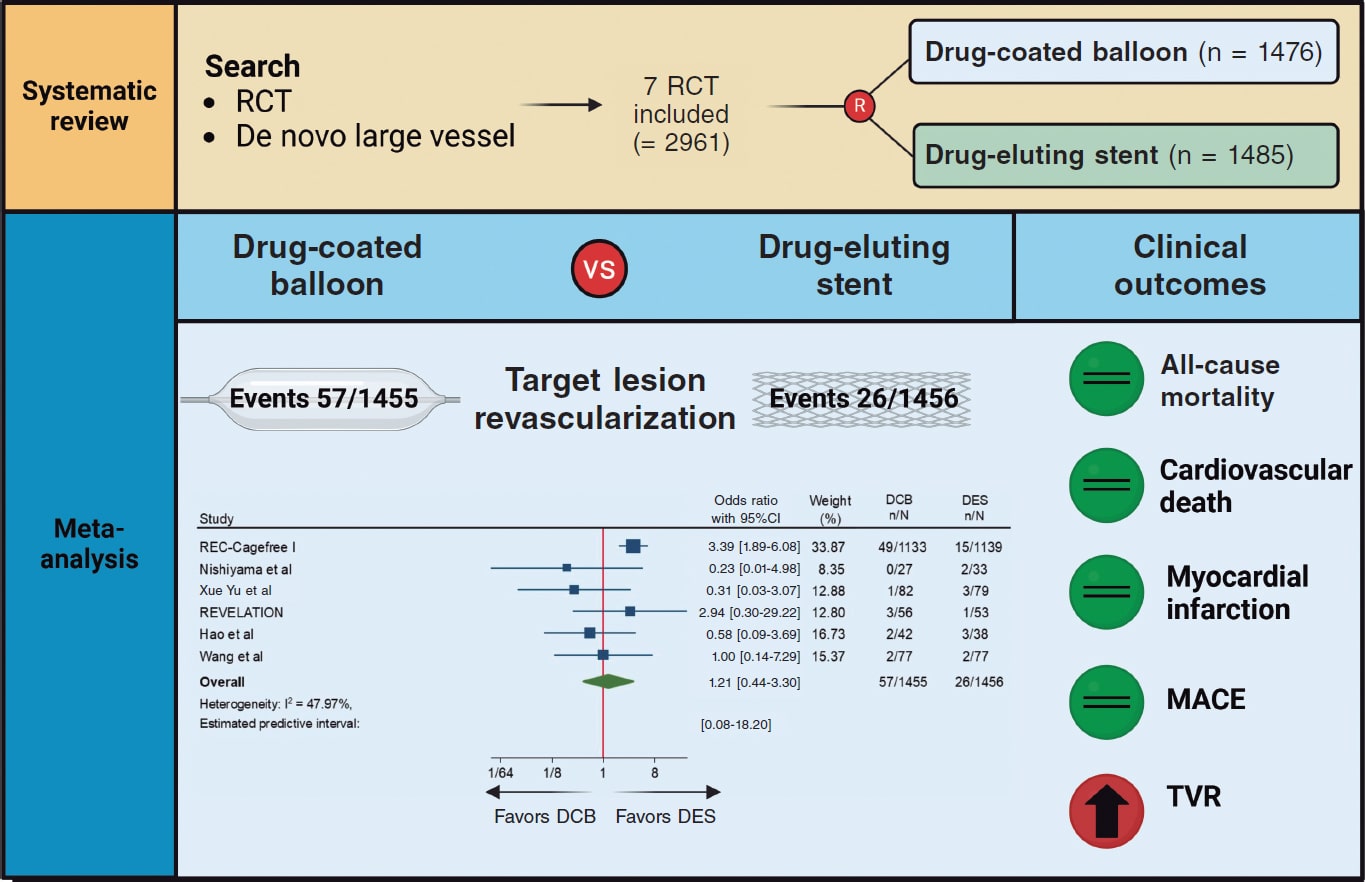

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: To compare the effects of drug-coated balloon (DCB) vs drug-eluting stent (DES) in patients presenting with de novo large vessel coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods: We conducted a systematic research of randomized controlled trials comparing DCB vs DES in patients with de novo large vessel CAD. Data were pooled by meta-analysis using a random-effects model. The prespecified primary endpoint was target lesion revascularization (TLR).

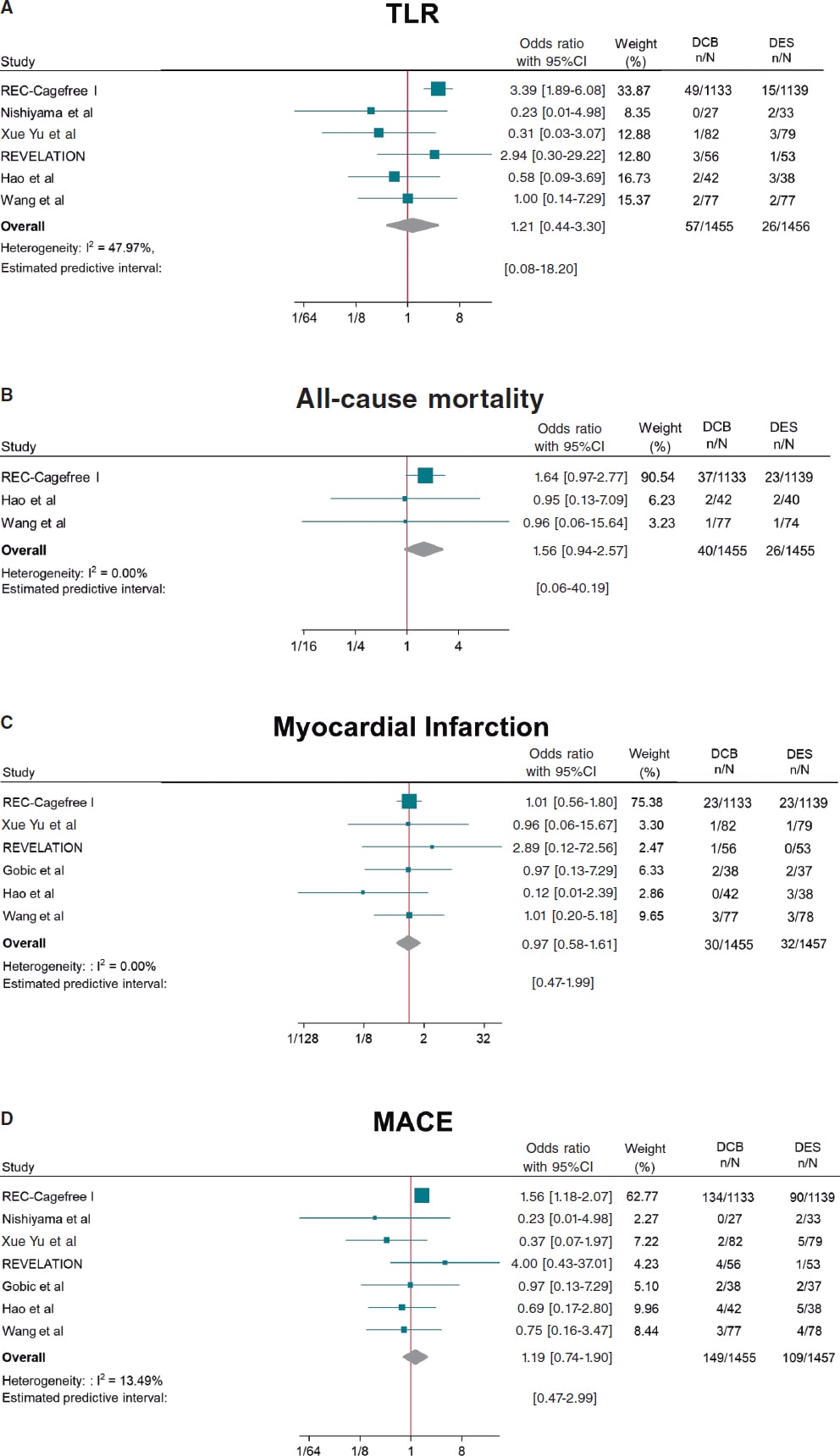

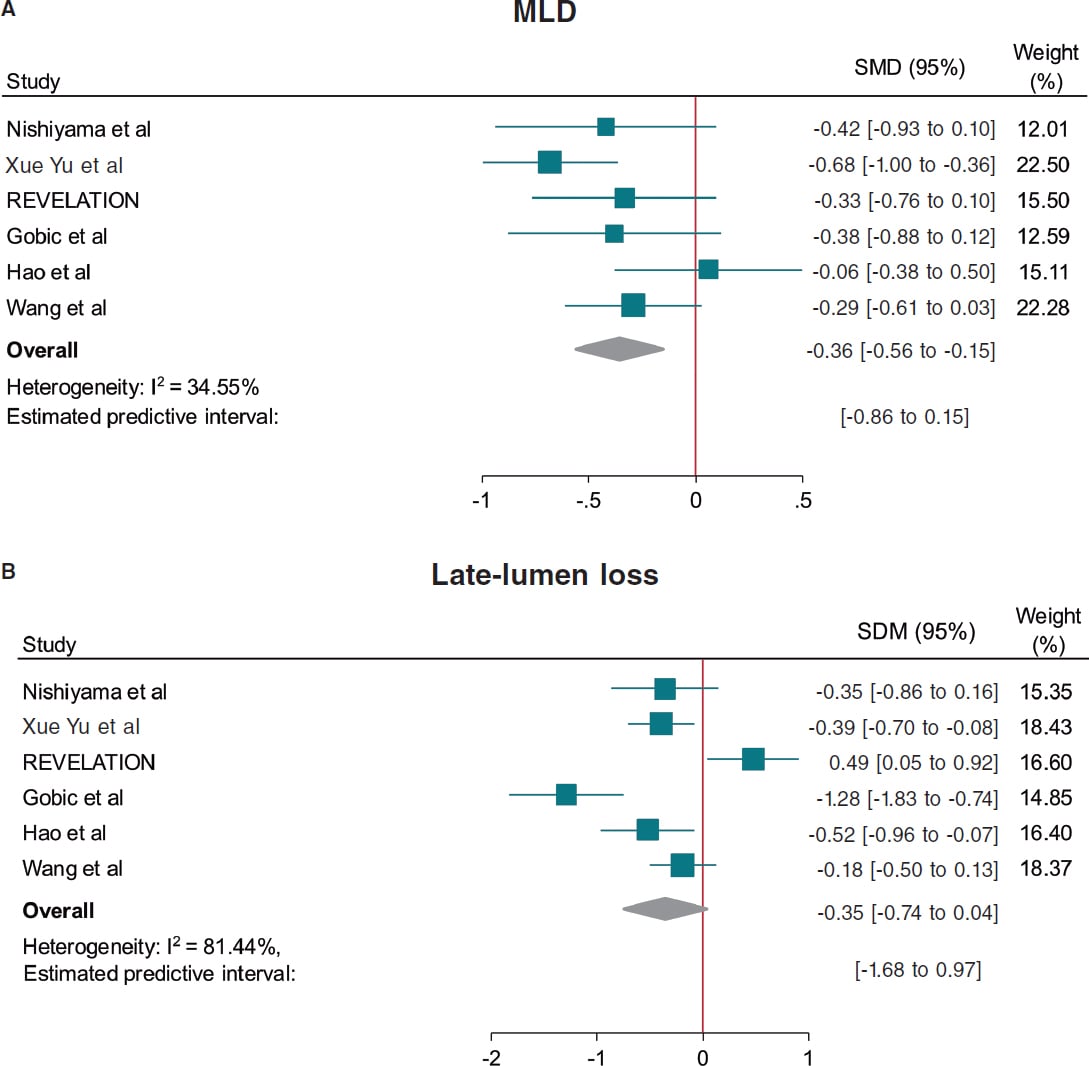

Results: A total of 7 trials enrolling 2961 patients were included. The use of DCB vs DES was associated with a similar risk of TLR (OR, 1.21; 95%CI, 0.44-3.30; I2 = 48%), all-cause mortality (OR, 1.56; 95%CI, 0.94- 2.57; I2 = 0%), cardiac death (OR, 1.65; 95%CI, 0.90-3.05; I2=0%), myocardial infarction (OR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.58-1.61; I2 = 0%), major adverse cardiovascular adverse (OR, 1.19; 95%CI, 0.74-1.90; I2 = 13.5%) and late lumen loss (standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.35; 95%CI, −0.74 to 0.04; I2 = 81.4%). However, the DCB was associated with a higher risk of target vessel revascularization (OR, 2.47; 95%CI, 1.52-4.03; I2 = 0%) and smaller minimal lumen diameter during late follow-up (SMD, −0.36; 95%CI, −0.56 to −0.15; I2 = 34.5%). Nevertheless, prediction intervals included the value of no difference for both outcomes.

Conclusions: In patients with de novo large vessel CAD the use of DCB vs DES is associated with a similar risk of TLR. However, the DES achieves better late angiographic results.

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon. Drug-eluting stent. Coronary artery disease.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Comparar los efectos del balón farmacoactivo (BFA) frente al stent farmacoactivo (SFA) en pacientes con enfermedad arterial coronaria (EAC) de gran vaso de novo.

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados comparando BFA frente a SFA en pacientes con EAC de gran vaso de novo. Los datos se agruparon mediante un metanálisis de efectos aleatorios. El objetivo primario fue la necesidad de revascularización de la lesión diana (RLD).

Resultados: Se incluyeron 7 ensayos con 2.961 pacientes. El uso de BFA, en comparación con SFA, se asoció con un riesgo similar de RLD (OR = 1,21; IC95%, 0,44-3,30; I2 = 48%), muerte por todas las causas (OR = 1,56; IC95%, 0,94-2,57; I2 = 0%), muerte de causa cardiovascular (OR = 1,65; IC95%, 0,90-3,05; I2 = 0%), infarto de miocardio (OR = 0,97; IC95%, 0,58-1,61; I2 = 0%), acontecimientos adversos cardiacos mayores (OR = 1,19; IC95%, 0,74-1,90; I2 = 13,5%) y pérdida luminal tardía (DME = −0,35; IC95%, −0,74 a 0.04; I2 = 81,4%). Sin embargo, el BFA se asoció a un mayor riesgo de revascularización del vaso diana (OR = 2,47; IC95%, 1,52-4,03; I2 = 0%) y a un menor diámetro luminal mínimo en el seguimiento (DME: −0,36; IC95%, −0,56 a −0,15; I2 = 34,5%), aunque los intervalos de predicción incluyeron el valor nulo para ambos resultados.

Conclusiones: En los pacientes con EAC de gran vaso de novo, el BFA comparado con el SFA se asoció a un riesgo similar de RLD, obteniendo el SFA mejores resultados angiográficos.

Palabras clave: Balón farmacoactivo. Stent farmacoactivo. Enfermedad arterial coronaria.

Abbreviations

CAD: coronary artery disease. DCB: drug-coated balloon. DES: drug-eluting stent. MI: myocardial infarction. MLD: minimum lumen diameter. TLR: target lesion revascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-eluting stents (DES) remain the standard of treatment for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1,2 However, DES are associated with a gradually and permanent increased risk of adverse events, particularly due to late stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis, with a 2% incidence rate per year with no plateau observed.1 This risk is even higher when complex and long lesions are treated.3 In recent years, drug-coated balloons (DCB) have emerged as a potential alternative treatment option to DES. Following adequate lesion preparation, unlike traditional stents, DCBs can release an antiproliferative drug into the vessel wall without leaving behind a permanent metal scaffold. Notably, permanent scaffolding can distort and constrain the coronary vessel, thus impairing vasomotion and adaptive remodelling, while also promoting chronic inflammation.4 DCB-PCI is a well-established treatment for in-stent restenosis and small-vessel coronary artery disease (CAD).5,6 However, its role in de novo large vessel CAD remains controversial. In a recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) with patients undergoing de novo CAD revascularization, a strategy of DCB-PCI did not achieve non-inferiority vs DES in terms of device-oriented composite endpoint driven by higher rates of target lesion revascularization (TLR).7 Contrary to prior published research, our findings did not support similar clinical outcomes for DCB vs DES in patients with de novo large vessel CAD.8,9 A recent meta-analysis of 15 studies compared DCB-PCI or hybrid angioplasty vs DES-PCI in patients with vessels > 2.75 mm in diameter showing no significant differences in the clinical endpoints of TLR, cardiac death, and MI.10 However, 14 of the 15 included studies were non-RCT, and the recent previously reported RCT was not included. Nevertheless, individual non-inferiority studies often lack the statistical power needed to definitively compare these technologies, underscoring the need for a systematic appraisal of treatment effects and evidence quality. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of available RCT to provide a comprehensive and quantitative assessment of evidence on the efficacy of DCB vs the current-generation DES in de novo large vessel CAD in terms of adverse events at longest available follow-up.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted a meta-analysis of RCT according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 guidelines.11 Two reviewers independently identified the relevant studies through an electronic search across the MEDLINE and Embase databases (from inception to October 2024). In addition, we employed backward snowballing (eg, reference review from identified articles and pertinent reviews). No language, publication date or publication status restrictions were imposed. This study is registered with PROSPERO and the search strategy is available in the supplementary data.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently assessed trial eligibility based on titles, abstracts, and full-text reports. Discrepancies in study selection were discussed and resolved with a third investigator. Eligible studies needed to meet the following pre-specified criteria: a) RCT comparing PCI with DCB and PCI with DES; b) study population including patients with de novo large vessel CAD (eg, defined as vessel diameter ≥ 2.5 mm);12 c) availability of clinical outcome data (without restriction as to follow-up time). Exclusion criteria were a) lack of a randomized design; b) studies including patients undergoing treatment for in-stent restenosis; c) studies including patients with de novo small vessel CAD; d) lack of any clinical outcome data.

A reference vessel diameter ≥ 2.5 mm was established as the cut-off value to define large vessel based on a recent proposed standardized definition.12

Data extraction

Three investigators (J. Llau García, S. Huélamo Montoro and J. A. Sorolla Romero) independently assessed studies for possible inclusion, with the senior investigator (J. Sanz-Sánchez) resolving discrepancies. Non-relevant articles were excluded based on title and abstract. The same investigators independently extracted data on study design, measurements, patient characteristics, and outcomes using a standardized data-extraction form. Data extraction conflicts were discussed and resolved with the senior investigator.

Data on authors, year of publication, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, patients’ baseline patients, endpoint definitions, effect estimates, and follow-up time were collected.

Endpoints

The prespecified primary endpoint was TLR. Secondary clinical endpoints were all-cause mortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Secondary angiographic endpoints were minimum lumen diameter (MLD) and late lumen loss (LLL). Each endpoint was assessed according to the definitions reported in the original study protocols, as summarized in table 1 of the supplementary data. All the endpoints were assessed at the maximum follow-up available.

Table 1. Main features of included studies

| Study | Year of publication | No. of patients | Type of Device | Reference vessel diameter (mean ± SD) (mm) | Multicenter | Clinical follow up (months) | Angiographic follow-up (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCB | DES | |||||||

| REC-CAGEFREE I7 | 2024 | 1133 | 1139 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

3.00 ± 0.55 | YES | 24 | NO |

| Nishiyama et al.13 | 2016 | 30 | 30 | Paclitaxel-DCB Everolimus-DES |

2.80 ± 0.63 | NO | 8 | 8 |

| Xue Yu et al.8 | 2022 | 85 | 85 | Paclitaxel-DCB Everolimus-DES |

2.89 ± 0.33 | NO | 12 | 9 |

| REVELATION9 | 2019 | 60 | 60 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus and everolimus DES |

3.24 ± 0.50 | NO | 24 | 9 |

| Gobic et al.15 | 2017 | 38 | 37 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

> 2.50 | NO | 6 | 6 |

| Hao et al.16 | 2021 | 38 | 42 | Paclitaxel-DCB NA |

> 2.50 | NO | 12 | 12 |

| Wang et al.14 | 2022 | 92 | 92 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

3.37 ± 0.52 | NO | 12 | 9 |

|

DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; NA, not available. |

||||||||

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in each study was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0).11 Three investigators (J. Llau García, S. Huélamo Montoro and J. A. Sorolla Romero) independently assessed 5 domains of bias in RCT: a) randomization process, b) deviations from intended interventions, c) missing outcome data, d) outcome measurement, and e) selection of reported results (table 2 of the supplementary data).

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics of included patients

| Study | Age (years) | Male (%) | Diabetes (%) | Smoking (%) | Hypertension (%) | LVEF (%) | Clinical Presentation (CCS/ACS) (%) | Multivessel (%) | Complex lesion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC-CAGEFREE I7 | 62 | 69.3 | 27.3 | 45 | 60.1 | 60 | 44.9/55.3 | 4.8 | 0 |

| Nishiyama et al.13 | 69 | 73.3 | 41.6 | 60 | 83.3 | NA | 0/100 | NA | 36 |

| Xue Yu et al.8 | 63.3 | 69.3 | 24.1 | 54 | 63.9 | > 40 | 11.1/88.9 | 84 | 44.1 |

| REVELATION9 | 57 | 87 | 10 | 60 | 31 | 57.6 | 0/100 | 71.6 | N/A |

| Gobic et al.15 | 57.4 | 87 | 10 | 49.5 | 33.4 | 50.2 | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

| Hao et al.16 | 57.5 | 78.5 | 31.5 | 29.5 | 24 | 46 | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

| Wang et al.14 | 49.5 | 93.5 | 81.6 | 81.5 | 71.8 | NA | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; NA, not available. |

|||||||||

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model, with the estimate of heterogeneity being obtained from the Mantel-Haenszel method. The presence of heterogeneity among studies was evaluated with the Cochran Q chi-square test, with P ≤ .10 being considered of statistical significance, and using the I2 test to evaluate inconsistency. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and values of ≤ 25%, ≤ 50%, > 50% indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Prediction intervals (95%) in addition to conventional 95%CI around ORs were calculated to assess residual uncertainty. Publication bias and the small study effect were assessed for all outcomes, using funnel plots. The presence of publication bias was investigated using Harbord and Egger tests and visual estimation with funnel plots. We performed a sensitivity analysis by removing one study at a time to confirm that the findings, when compared with DES, were not driven by any single study. To account for different lengths of follow-up across studies, another sensitivity analysis was performed using the Poisson regression model with random intervention effects to calculate inverse-variance weighted averages of study-specific log stratified incidence rate ratios (IRRs). Results were displayed as IRRs, which are exponential ratios of the regression model. Additionally, random-effect meta-regression analyses were performed to assess the impact of the following variables on treatment effect with respect to the primary endpoint: eg, percentage of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), percentage of patients with diabetes mellitus, mean reference vessel diameter and follow-up duration. The statistical level of significance was 2-tailed P < .05. Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, United States), was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Search results

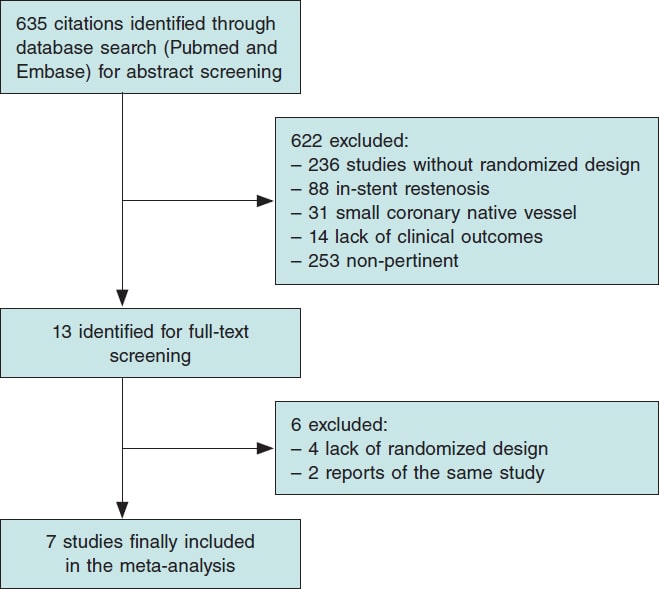

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA study search and selection process. A total of 7 RCT were identified and included in this analysis. The main features of included studies are shown in table 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the search for studies included in the meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement.

All studies had a non-inferiority design. A clinical primary endpoint was selected in 1 study,7 and an invasive functional endpoint was selected in another trial,9 while angiographic primary endpoints were prespecified in the remaining studies.8,13-16 The mean clinical and angiographic follow-up were 21.5 months and 8.9 months respectively. A total of 4 studies were conducted in the context of ACS9,14-17 and 1 study in the context of chronic coronary syndrome (CCS).13 Finally, 2 studies enrolled both ACS and CCS patients.7,8 A total of 3 trials enrolled patients treated with second-generation DES (Firebird 2.0 [Microport, China], Xience Xpedition [Abbott Vascular, United States], Orsiro [Biotronik, Germany]),7,9,13 and 2 studies enrolled patients treated with third-generation DES (Biomine [Meril Life Sciences, India], Cordimax [Rientech, China]).14,15 One trial enrolled patients treated with second and third-generation DES (Xience Xpedition [Abbott Vascular, United States], Resolute Integrity, [Medtronic, United States], Firehawk, [MicroPort, China]).8 All studies included patients who underwent paclitaxel-DCB-PCI ([Pantera Lux, Biotronik, Germany],9,14 [SeQuent Please, B Braun, Germany],7,8,13,15 [Bingo DCB, Yinyi Biotech,China]),16 and none with sirolimus-DCB-PCI.

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2961 patients were included, 1476 of whom received DCB and 1485, DES for de novo large vessel CAD. The patients main baseline characteristics are shown in table 2.

Publication bias and asymmetry