Original article

Angiography-derived index versus fractional flow reserve for intermediate coronary lesions: a meta-analysis review

Índice derivado de la angiografía frente a reserva fraccional de flujo en lesiones coronarias intermedias. Revisión de metanálisis

aDepartamento de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain bCentro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Mitral regurgitation is one of the most common heart valve diseases. Valve replacement surgery is a guideline-recommended option; however, in a significant proportion of patients, this option is not feasible. In such cases, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) is a potential therapeutic alternative. Nevertheless, the results of a randomized clinical trial have shown divergent results. Recently, the results of the RESHAPE-HF2 trial were published, providing additional insights. The objective of this work is to evaluate whether there are any differences between performing M-TEER and keeping patients under guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).

Methods: We conducted a meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. We searched for studies across the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases until February 2025. We establish the following inclusion criteria: patients with secondary mitral regurgitation, studies comparing M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone, and who reported hospitalization due to heart failure (HF) or mortality.

Results: A total of 3 randomized clinical trials meet the inclusion criteria, including a total of 1423 patients: 704 received M-TEER and 719, GDMT alone. M-TEER was associated with a reduced risk of HF-related hospitalization with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.56-0.90; P = .004). We did not find any differences in all-cause mortality with a RR of 0.80 (95%CI, 0.63-1.02; P = .07).

Conclusions: In this meta-analysis, M-TEER plus GDMT shows a lower risk of HF-related hospitalization vs GDMT alone. We did not find any differences in the risk of all-cause mortality or cardiac death.

Registered at PROSPERO: CRD42025645047.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation. Mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. Heart failure. M-TEER.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La regurgitación mitral es una de las valvulopatías cardiacas más comunes. La cirugía de reemplazo valvular es una opción recomendada por las guías clínicas. Sin embargo, en un porcentaje significativo de pacientes, esta opción no es viable. En estos casos, la reparación mitral percutánea de borde a borde (M-TEER) es una posible alternativa terapéutica. No obstante, los resultados de los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados han mostrado resultados divergentes. Recientemente se han publicado los resultados del estudio RESHAPE-HF2, que aportan información adicional sobre este tema. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar si existen diferencias entre realizar M-TEER o mantener a los pacientes bajo tratamiento médico según las guías clínicas (TMSG).

Métodos: Se realizó un metanálisis siguiendo las guías PRISMA. Se buscaron estudios en las bases de datos PubMed, Embase y Cochrane hasta febrero de 2025. Se establecieron los siguientes criterios de inclusión: pacientes con insuficiencia mitral secundaria, estudios que comparaban M-TEER más TMSG frente a solo TMSG, y que indicaran hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca o mortalidad.

Resultados: Tres ensayos clínicos aleatorizados cumplieron los criterios de inclusión, con un total de 1.423 pacientes, de los que 704 se trataron con M-TEER y 719 recibieron solo TMSG. La M-TEER se asoció con una reducción del riesgo de hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca con una razón de riesgo de 0,71 (IC95%, 0,56-0,90; p = 0,004). No se encontraron diferencias en cuanto a muerte por cualquier causa, con una razón de riesgo de 0,80 (IC95%, 0,63-1,02; p = 0,07).

Conclusiones: En este metanálisis, la M-TEER, en combinación con el TMSG, mostró una reducción del riesgo de hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca en comparación con el TMSG solo. No se hallaron diferencias en el riesgo de muerte por cualquier causa (muerte de causa cardiovascular o infarto agudo de miocardio).

Registrado en PROSPERO: CRD42025645047.

Palabras clave: Regurgitación mitral. Reparación percutánea de borde a borde. Insuficiencia cardiaca. M-TEER.

Abreviaturas

MR: mitral regurgitation. M-TEER: mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. GDMT: guideline-direct medical therapy. HF: heart failure. NYHA: New York Heart Association.

INTRODUCTION

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is a prevalent valvular heart disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients with heart failure (HF).1 Traditional management strategies include optimal medical therapy to treat symptoms and surgery for definitive correction.2 However, current clinical practice guidelines only recommend mitral valve repair if the patient is undergoing another intervention such as coronary artery bypass graft or aortic valve replacement; nonetheless, many patients are at a high risk for surgery due to comorbid conditions, for this reason, alternative therapeutic options is required.3

Mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) has emerged as a minimally invasive option for patients with symptomatic mitral regurgitation who are ineligible for surgery.4 While M-TEER has shown promising results, its comparative efficacy vs guideline- directed medical therapy (GDMT) is still a matter of discussion.5

This meta-analysis aims to assess the impact of M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone on major clinical outcomes in patients with secondary MR. The primary endpoint evaluated was HF-related hospitalization. Secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality, cardiac death, improvement in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (FC), and the incidence rate of stroke and myocardial infarction. These endpoints were selected for their clinical relevance and potential to inform therapeutic decision-making in this high-risk patient population.

METHODS

We conducted this meta-analysis in full compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines.6 All the stages of this study were performed following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3.7 The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered prospectively in PROSPERO on 10 February 2025 with protocol ID CRD42025645047.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search across 3 electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and COCHRANE) from inception until February 2025. Search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “transcatheter”, “secondary”, “mitral valve”, “replacement”, regurgitation”, and “insufficiency”. These keywords were combined using Boolean operators AND, OR. The reference lists of eligible studies and previous reviews were checked to identify additional valuable articles.

Criteria of the included studies

Studies were considered for inclusion in the meta-analysis based on the following criteria: a) randomized clinical trials (RCT) or observational cohort studies in Spanish or English that b) compared transcatheter mitral valve replacement vs optimal medical therapy in adult patients with mitral valve regurgitation due to secondary causes; and c) studies that reported outcomes of interest such as the index HF-related hospitalization, HF-related readmissions or cardiac death, and all-cause mortality.

Studies were excluded if they were non-original articles such as systematic reviews, letters, abstracts, meta-analyses, case reports, or case series. Furthermore, studies were excluded if mitral regurgitation was due to primary causes or if prior surgical repair had been performed.

Although observational cohort studies were eligible, we only identified 1 cohort study that did not meet the inclusion criteria during full-text screening. As a result, only RCTs were ultimately included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

To ensure accuracy, we used Zotero to eliminate duplicate references. We screened each paper based on title and abstract as a first step, followed by a full-text review as the second step. Two authors (D.A. Navarro Martínez, and D. Paulino-González) independently screened each paper, with any disagreements being resolved by a third author (A.L. García Loera). In addition, references of the included studies were reviewed and added if they met our eligibility criteria. Data extraction was conducted using Excel spreadsheets capturing the following information: a) baseline characteristics of the studied population, including baseline medication, echocardiographic baseline characteristics, and comorbidities; b) summary of the characteristics of the included studies; c) outcome measures; and d) quality assessment domains.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoints established for this meta-analysis included: a) all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR]), defined as all-cause mortality, assessed using time-to-event analysis,8 and b) HF-related hospitalization, defined as hospital admission for worsening HF following the intervention (M-TEER or initiation of optimal medical therapy).9

Secondary endpoints included a) stroke, defined as an episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal cerebral, spinal, or retinal infarction;10 and b) myocardial infarction, defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition.11

All endpoints were assessed as dichotomous categorical variables, which were reported in percentages. The risk ratio (RR) with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To assess heterogeneity, we used Cochrane’s Q-statistic with a significance level of P < .05. Additionally, the I²-statistic was used to quantify the proportion of variability due to heterogeneity, with values > 50% being considered indicative of high heterogeneity.12

Statistical analyses

To assess dichotomous data, we evaluated event frequencies and totals from each study group to calculate the RR and its 95%CI. Moreover, we obtained the HR and the 95%CI to calculate the standard error (SE).

The variables analyzed in this study were based on data reported in the original studies of the intention-to-treat principle. We implemented a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird13 method to account for variability and allow comparison across studies. Given the limitations and strengths of this method, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method. Forest plots were utilized as a visual representation of the estimated outcomes.

Considering the differences in the populations included in the clinical trials, we conducted an additional exploratory analysis that focused on the RESHAPE-HF214 and COAPT15 trials for the primary endpoints by removing MITRA-FR16 from the analysis.

All statistical analyses, including the calculation of RR and SE, were conducted using RevMan V.5.4.1 software.

RESULTS

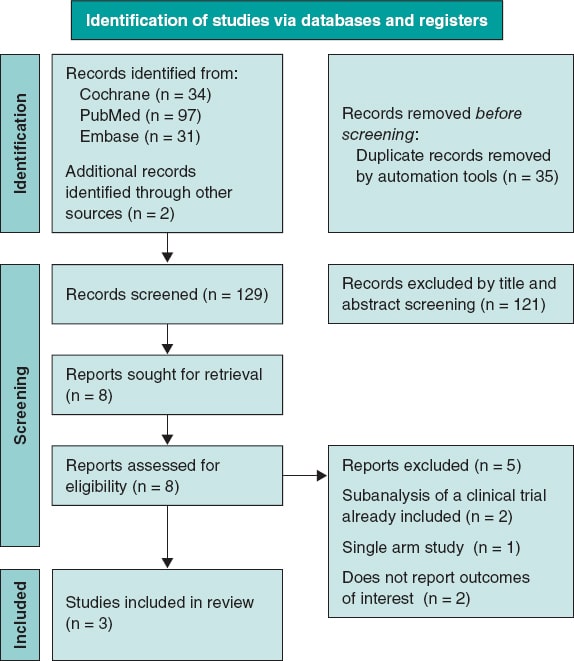

The initial database search yielded a total of 164 potentially relevant articles. After removing duplicates, a total of 129 articles finally remained for title and abstract screening. Following this initial screening, 8 articles were identified as potentially eligible for full-text review. Finally, after a detailed evaluation of the full texts under the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3 studies were included. A summary of the study selection process is shown in the PRISMA flowchart figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

Our analysis included 3 RCTs.14-16 We consulted the extended report of the 2-year outcomes of the MITRA-FR trial17 and 1 additional article on the RESAHPE-HF2 to obtain more data regarding hospitalization.18 All included studies compared the use of M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone. To standardize the outcomes, the median follow-up was set at 24 months; only the NYHA FC was evaluated with 1-year results. All 3 included studies used the MitraClip (Abbott, United States) device.

Clinical baseline characteristics of the patients

We obtained a total population of 1423 patients; among them 704 received M-TEER and 719, GDMT alone. In the RESHAPE-HF214 the device group showed the following characteristics: mean age was 70 years old; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 32%; median left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), 200 mL; median effective regurgitation orifice (EROA), 0.23 cm2; median N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), 2651; and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), 556. In the COAPT15 trial, median age was 71 years old; LVEF, 31%; LVEDV, 194 mL; median EROA, 0.41 cm2; median NT-proBNP, 5174; and BNP, 1014. Finally in the MITRA-FR trial16, mean age was 71 years old; LVEF, 33%; LVEDV, 136.2 mL; median EROA, 0.31 cm2; median NT-proBNP, 3407; and BNP, 765. Regarding etiology, all trials enrolled mixed ischemic and non-ischemic etiology populations. Patient and study baseline characteristics, including comorbidities, drugs, and echocardiographic data, are shown in table 1, table 2, and table 3.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| Reference | Groups | N | Age | AF or flutter | Diabetes | Previous MI | Nonischemic etiology | Ischemic etiology | 6-min walk distance | Beta- blocker | ACEI | ARB | ARNI | SGLT2i | MRA | Diuretics | Oral anti- coagulants | BNP | NT-proBNP | EuroSCORE II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESHAPE-HF214 | M-TEER | 250 | 70.0 ± 10.4 | 118 (47.2) | 91 (36.4) | 144 (57.6) | 88 (35.2) | – | 300 (220-382) | 238 (95.2) | 142 (56.8) | 51 (20.4) | 40 (16.0) | 24 (9.6) | 200 (80.0) | 239 (95.6) | 163 (65.2) | 556 (312-1018) | 2651 (1630-4918) | 5.3 (2.7-8.9) |

| Optimal medical therapy | 255 | 69.4 ± 10.7 | 125 (49.0) | 85 (33.3) | 135 (52.9) | 88 (34.5) | – | 310 (200-378) | 246 (96.5) | 142 (55.7) | 45 (17.6) | 28 (11.0) | 22 (8.6) | 215 (84.3) | 243 (95.3) | 152 (59.6) | 406 (231-874) | 2816 (1306-5496) | 5.3 (2.9-9.0) | |

| COAPT15 | M-TEER | 302 | 71.7 ± 11.8 | 173 (57.3) | 106 (35.1) | 156 (51.7) | 118 (39.1) | 184 (60.9) | 261.3 ± 125.3 | 275 (91.1) | 138 (45.7) | 66 (21.9) | 13 (4.3) | NR | 153 (50.7) | 270 (89.4) | 140 (46.4) | 1014.8 ± 1086.0 | 5174.3 ± 6566.6 | NR |

| Optimal medical therapy | 312 | 72.8 ± 10.5 | 166 (53.2) | 123 (39.4) | 160 (51.3) | 123 (39.4) | 189 (60.6) | 246.4 ± 127.1 | 280 (89.7) | 115 (36.9) | 72 (23.1) | 9 (2.9) | NR | 155 (49.7) | 277 (88.8) | 125 (40.1) | 1017.1 ± 1212.8 | 5943.9 ± 8437.6 | NR | |

| MITRA-FR16 | M-TEER | 152 | 70.1 ± 10.1 | 49/142 (34.5) | 50 (32.9) | 75 (49.3) | 57 (37.5) | 95 (62.5) | 307 (212-387) | 134 (88.2) | 111 (73.0) | 111 (73.0) | 14/140 (10) | NR | 86 (56.6) | 151 (99.3) | 93 (61.2) | NR | NR | 7.33 ± 6.29 |

| Optimal medical therapy | 152 | 70.6 ± 9.9 | 48/147 (32.7) | 39 (25.7) | 52 (34.2) | 66 (43.7) | 85 (56.3) | 335 (210-410) | 138 (90.8) | 113 (74.3) | 113 (74.3) | 17/140 (12.1) | NR | 80 (53.0) | 149 (98.0) | 93 (61.2) | NR | NR | 6.57 ± 5.24 | |

|

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NR, not reported; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2. Summary of included studies

| Authors and year | Study design | Device | Population size | Compared interventions | Mean follow-up | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anker et al. RESHAPE-HF2 202414 | RCT | MitraClip | 505 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

| Stone et al. COAP 201815 | RCT | MitraClip | 614 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

| Obadia et al. MITRA - FR 201816 | RCT | MitraClip | 304 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; OR, odds ratio. |

||||||

Table 3. Echocardiographic baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | RESHAPE-HF214 | COAPT15 | MITRA-FR16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device group | Control group | Device group | Control group | Device group | Control group | |

| Severity MR Grade 3+, n,% (n) | 141 (56.4) (250) | 141(55.3) (255) | 148 (49.0) (302) | 172 (55.3) (312) | – | – |

| Severity MR Grade 4+, n,% (n) | 109 (43.6) (250) | 114 (44.7) (255) | 154 (51.0) (302) | 139 (44.7) (312) | – | – |

| LVEF, % (n) | 32 (26-37) (250) | 31 (25-37) (255) | 31.3 ± 9.1 (302) | 31.3 ± 9.6 (312) | 33.3 ± 6.5 | 32.9 ± 6.7 |

| LVEDV, mL (n) | 137 (100-173) (250) | 140 (104-176) (255) | 135.5 ± 56.1 (302) | 134.3 ± 60.3 (312) | – | – |

| LVEDV, mL (n) | 200 (153-249) (250) | 206 (158-250) (255) | 194.4 ± 69.2 (302) | 191.0 ± 72.9 (312) | 136.2 ± 37.4 | 134.5 ± 33.1 |

| LVESD, cm (n) | 5.8 (5.3-6.5) (250) | 5.9 (5.3-6.4) (255) | 5.3 ± 0.9 (302) | 5.3 ± 0.9 (312) | – | – |

| LVEDD, cm (n) | 6.9 (6.3-7.6) (250) | 6.8 (6.4-7.5) (255) | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | – | – |

| EROA, cm2 (n) | 0.23 (0.20-0.30) (250) | 0.23 (0.19-0.29) (255) | 0.41 ± 0.15 | 0.40 ± 0.15 | 0.31 ± 10* | 0.31 ± 11* |

| Regurgitant volume, mL (n) | 35.4 (28.9-43.9) (250) | 35.6 (28.2-42.5) (255) | – | – | 45 ± 13 | 45 ± 14 |

|

EROA, effective regurgitant orifice area; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; MR, mitral regurgitation. RESHAPE-HF2 data express median and interquartile range [IQR] in the COAPT trial. MITRA-FR data express median ± standard deviation. * This data was originally expressed in mm2 and has been converted to standardized meditation. |

||||||

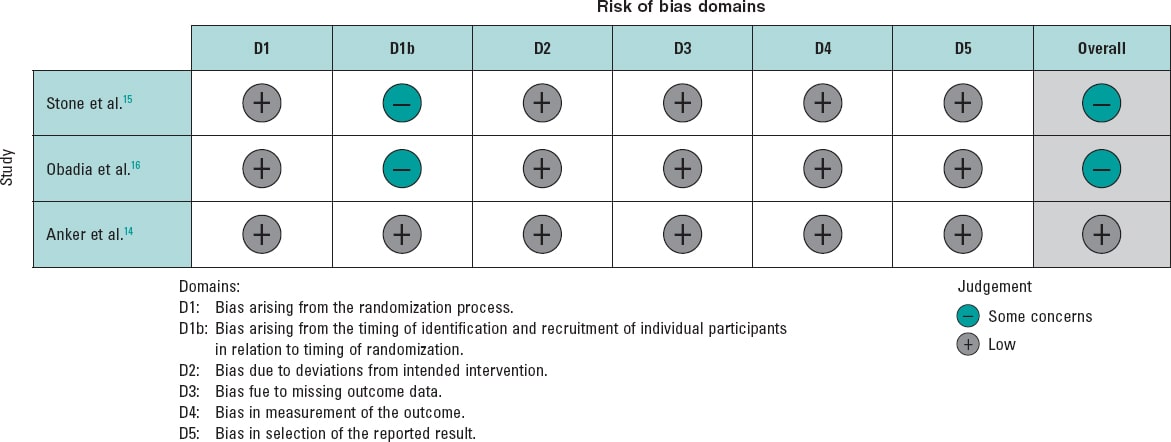

Risk of bias assessment

To evaluate the quality of the included randomized controlled trials, we used the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions 6.3.7 This methodology allowed us to systematically assess the methodological quality of each study, thereby strengthening the validity of our findings.

Of the 3 studies, 1 had a low risk of bias,14 while the other 2 raised some concerns.15,16 The studies with some concerns were limited by factors in their methodologies, as they were open-label studies (figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk of bias for each included randomized clinical trial. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al.16.

Outcomes

HF-related hospitalization

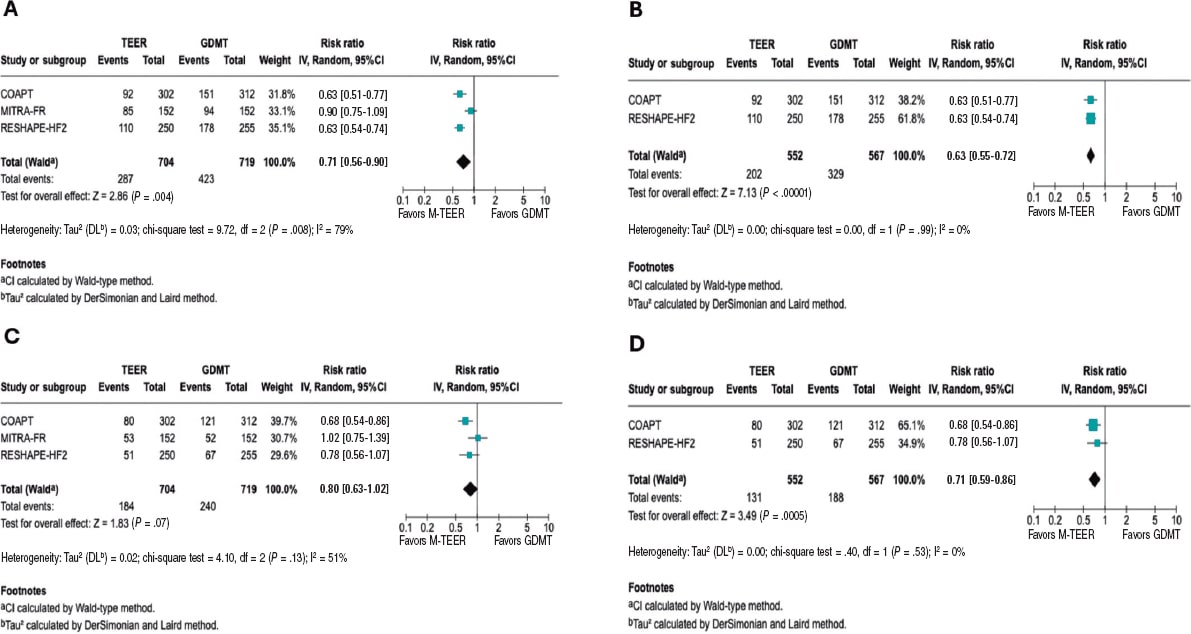

The analysis of this outcome showed a significant reduction, with a RR of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.56-0.90; P = .004). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed, with an I² value of 79%. Considering the differences in the MITRA-FR study population, we conducted an exploratory analysis excluding this trial. Results still demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalization, with a RR of 0.63 (95%CI, 0.55-0.72, P < .00001), along with a marked improvement in heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Of note, this finding is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution.

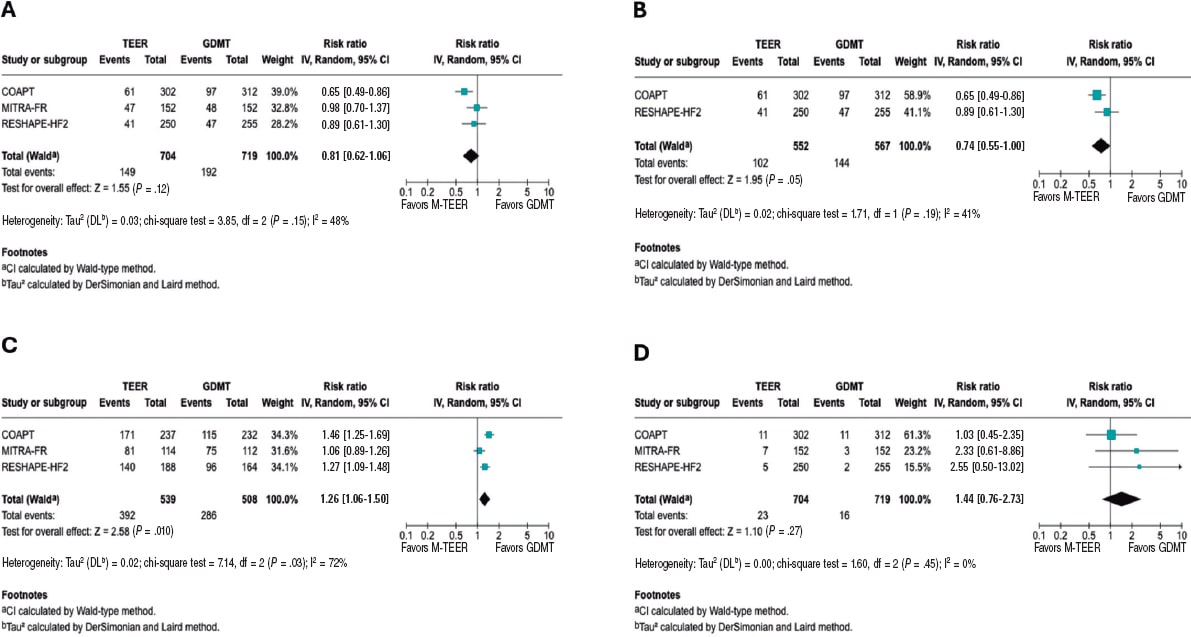

The analysis, including all studies, is shown in figure 3A, and the exploratory analyses are shown in figure 3B. Furthermore, we analyzed HR for this endpoint and, given the limited number of studies, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) method; all these analyses are provided in the supplementary data (figures S1-S4).

Figure 3. Forest plot of risk ratios (RR). Lines denote the 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for each trial. A: forest plot of RR for HF related hospitalization. B: forest plot of exploratory RR for HF-related hospitalization. C: forest plot of RR for all-cause mortality. D: forest plot of exploratory RR for all-cause mortality. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; GDMT, guideline directed medical therapy; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al.16.

All-cause mortality

The RR for all-cause mortality was 0.80 (95%CI, 0.63–1.02; P = .07). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I² = 56%). In the exploratory analysis, a significant reduction in mortality was found, with an RR of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.59–0.86; P = .0005) and no heterogeneity across the studies (I² = 0%). The analyses, including all studies, are shown in figure 3C, and the exploratory analysis in figure 3D.

Both the HR analysis and the sensitivity analysis are provided in the supplementary data (figures S5-S8).

Cardiac death

The RR for death from cardiovascular causes was 0.81 (95%CI, 0.62–1.06, P = .12), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I² = 48%). In the exploratory analysis, a significant reduction in cardiac death was observed, with an RR of 0.74 (95%CI, 0.55–1.00; P = .05) and low heterogeneity (I² = 41%). The analyses, including all studies, are shown in figure 4A, while the exploratory analysis, in figure 4B. The sensitivity analysis and HR results are provided in the supplementary data (figures S9-S12).

Figure 4. Forest plot of risk ratio (RR). A: forest plot of RR for cardiac death. B: forest plot of exploratory RR for cardiac death. C: forest plot of RR of NYHA FC I/II at 1 year. D: forest plot of RR for stroke. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; GDMT, guideline directed medical therapy; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al16. Lines denote the 95%CI for each trial.

NYHA FC

In this analysis of the NYHA FC, we observed that patients undergoing M-TEER are more likely to be found in NYHA FC I/II at 12 months, with a RR 1.26 (95%CI, 1.06–1.50; P = .010), respectively. Of note, the high heterogeneity (I² = 72%). Furthermore, it is also essential to note that the NYHA FC is a subjective classification, which is why the findings of this outcome should be interpreted with caution. These results are shown in figure 4C.

Stroke

There were no statistical differences between M-TEER and optimal medical therapy regarding stroke, with a RR of 1.44 (95%CI, 0.76 - 2.73, P = .27) without any heterogeneity being reported across the studies (I² = 0%). These results are shown in figure 4D.

Myocardial Infarction

Regarding the risk of myocardial infarction, our analysis demonstrated no statistical difference between the M-TEER and optimal medical therapy groups (RR, 0.83; 95%CI, 0.43-1.61; P = .58). No heterogeneity among the studies was observed (I² = 0%); this finding is shown in supplementary data (figure S13).

Exploratory analysis by severity

We conducted an exploratory analysis stratified by the baseline grade of mitral regurgitation. Data on the composite endpoint of all-cause death or HF-related hospitalization were available according to MR grade. For patients with MR 3+, the RR was 0.75 (95%CI, 0.56-1.00; P = .05; I² = 12%). For those with severe MR 4+, data were available only from the RESHAPE-HF2 and COAPT trials, yielding a RR of 0.55 (95%CI, 0.42-0.73; P = .0001; I² = 0%). This finding is shown in the supplementary data (figure S14 to figure S15).

DISCUSSION

Our meta-analysis provides an evaluation of 3 major RCTs, COAPT15, MITRA-FR16, and RESHAPE-HF214, evaluating M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone in patients with secondary MR. In patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate GDMT and who do not meet the criteria for definitive surgical replacement, mitral M-TEER has emerged as a promising alternative. In this updated meta-analysis, no statistically significant effect on all-cause mortality was found; however, the marked between-trial heterogeneity suggests that M-TEER provides meaningful clinical benefit when used in appropriately selected patients.

Our study showed that heterogeneity of results was mainly driven by MITRA-FR. COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 have multiple similar differences compared with MITRA-FR, as evidenced in trial cohort baseline characteristics, methods, and outcome directions. This is better portrayed by an exploratory analysis comparing COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 results, showing a 37% reduction in the risk of HF-related hospitalization risk and a 32% reduction in cardiac death (figure 3). The overall neutral mortality rate resulting from our study may be driven by heterogeneity across trials rather than a lack of intrinsic therapeutic benefit.

Among the main differences across trials, the MITRA-FR trial had broader inclusion of patients with tricuspid regurgitation, advanced LV remodeling, greater dilation, and smaller EROA vs the other 2 trials. Another key source of heterogeneity was baseline MR severity. COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 primarily enrolled patients with grade 3+ and 4+ MR, whereas MITRA-FR is only focused on grade 4+, which may contribute to the observed outcome differences. In our exploratory analysis by MR grade, data showed consistent trends favoring M-TEER; however, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to limited subgroup data.

As proposed by Paul et al.,19 one strategy to evaluate secondary MR is to consider the proportion between EROA and LVEDV. In the MITRA-FR trial, many patients had smaller EROA with markedly dilated ventricles, a phenotype in which GDMT may have more impact than valve proceduren. In the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials, a greater proportion of patients had large EROA relative to the LVEDV,20 making MR a primary driver of symptoms and outcomes, and, therefore, with potential for greater benefit from M-TEER.

In the trial-level subgroup analyses, the COAPT15 and RESHAPE-HF214 trials reported no significant interaction between treatment assignment and ischemic vs non-ischemic etiology, which indicates consistency of benefit across etiologies. Similarly, the MITRA-FR16 did not identify significant heterogeneity regarding etiology across prespecified subgroups. This suggests that ischemic vs non-ischemic alone should not be used to decide the treatment option in secondary MR. Instead, clinical decisions should prioritize other factors, such as the MR severity, the degree of LV dysfunction, symptom burden, and response to optimal medical therapy.21

Furthermore, differences between trials in procedural success are noteworthy, defined as achieving MR ≤ 2+. This was substantially lower in the MITRA-FR (75.6% MR ≤ 2+ at discharge) vs the COAPT (94.8% MR ≤ 2+ at 12 months) and the RESHAPE-HF2 (90.4% MR ≤ 2+ at 12 months). Multiple reasons could have influenced such differences; for instance, operator experience requirement in MITRA-FR (≥ 5 prior MitraClip cases) vs the high-volume and more experienced centers from the other trials. Similarly, post-approval data from the U.S. SSTS/ACC TVT Registry22 demonstrated > 90% MR reduction to ≤ 2+ and survival rates consistent with trial outcomes, underscoring the reproducibility of clinical benefit in experienced centers. Furthermore, device technology is a main contributor to these differences, from first-generation clips in MITRA-FR, to second-generation in COAPT, to the fourth-generation in RESHAPE-HF2 with independent leaflet grasping and wider arm options, potentially explaining discrepant clinical results regarding MR durability and outcomes. Lastly, GDMT implementation differed across trials. MITRA-FR was conducted before the widespread use of ARNI and SGLT2 inhibitors; COAPT was conducted before the adoption of SGLT2 inhibitors; and RESHAPE-HF2 reflects the contemporary use of quadruple therapy.

Despite the differences in patient phenotypes across the trials, in many developing countries, access to transcatheter valve procedures remains limited, primarily due to their high cost and the need for specialized infrastructure.23,24 The pronounced disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies, coupled with the centralization of these procedures in a few urban centers or high-specialty hospitals, a phenomenon observed even in high-income countries such as the United States, leave a substantial portion of the population without viable treatment options.25 Consequently, the most impactful and broadly deployable intervention in these regions remains rigorous GDMT optimization and provider education. Nevertheless, patient phenotyping should still be performed to identify those who may potentially have an outsized benefit from future M-TEER referrals.

By integrating trial-level population characteristics with clinical outcomes, our work bridges the gap between isolated trial findings and real-world patient selection, thus offering a potential framework for future prospective studies and for refining guideline criteria. While the results from our study must be interpreted with caution, they provide hypothesis-generating evidence supporting the concept that patient selection, particularly considering the balance between EROA and LVEDV and GDMT optimization, may be critical to optimizing the benefit of M-TEER in secondary MR. This approach moves beyond the broad application of current guideline recommendations and points toward a more individualized strategy in which anatomical and functional parameters guide intervention.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study lies in the heterogeneity of the populations enrolled in the randomized controlled trials, as evidenced by the I2 observed in the analyses, which may influence the overall results. Second, differences in MR severity across trials represent a key limitation. While the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials mainly included patients with MR grade 3+ or 4, MITRA-FR enrolled a more severe grade, which may partly explain divergent results. Lastly, an individual patient-level meta-analysis could not be conducted due to lack of data; this level of analysis would further increase statistical power, especially in subgroup analyses, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In this meta-analysis, M-TEER plus GDMT shows a lower risk of HF-related hospitalization vs GDMT alone. We did not find any differences in the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiac death, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This meta-analysis was performed using data from previously published studies. As it is based entirely on secondary data, no new data were collected from human or animal participants; on the other hand, the use of SAGER guidelines was not applicable in this study. All included studies were approved from the relevant center ethics committees. The authors confirm that all data utilized were publicly accessible, and no confidential information was used without proper authorization.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4o to review the document’s syntax and grammar. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

D. Paulino-González: conceptualization; formal analysis, writing, review, and editing. A.L. García-Loera: methodology, investigation, writing, review, and editing. D.A. Navarro-Martínez: methodology, formal analysis. M.A. Pardiño-Vega: writing, review, and editing, supervision. K.P. Zúñiga-Montaño: investigation, writing, review, and editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Mitral regurgitation is a prevalent condition that negatively affects the patients’ quality of life. M-TEER-has emerged as an alternative therapeutic option for patients who are ineligible for surgery. However, its benefit remains unclear vs GDMT, as clinical trials evaluating this procedure have reported disparate results, with benefit in primary outcomes observed in the COAPT trial and in the recently published RHESAPE-HF2 trial, but not in the MITRA-FR trial; discrepancy in the results requires further study.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive evaluation of the evidence comparing M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone in secondary mitral regurgitation. Our findings confirm that M-TEER is associated with a significant reduction in HF-related hospitalizations. Of note, by examining trial populations in detail, we highlight how patient selection influences outcomes: in studies enrolling patients with less ventricular dilation and lower biomarker levels of congestion (such as the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials), M-TEER was associated with additional benefits in cardiac death and all-cause mortality. These results underscore the potential role of anatomical and functional parameters, such as the balance between EROA and LVEDV, in identifying patients most likely to benefit from this procedure.

REFERENCES

1. Chehab O, Roberts-Thomson R, Ng Yin Ling C, et al. Secondary mitral regurgitation:pathophysiology, proportionality and prognosis. Heart. 2020;106:716-723.

2. Sengodan P, Younes A, Shah N, Maraey A, Chitwood WR Jr, Movahed A. Contemporary review of the evolution of various treatment modalities for mitral regurgitation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2024;22:639-651.

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159-e1195.

4. Itabashi Y, Kobayashi S, Mizutani Y, Torikai K, Taguchi I. Treatment of secondary mitral regurgitation by transcatheter edge-to-edge repair using MitraClip. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2022;49:389-403.

5. Barnes C, Sharma H, Gamble J, Dawkins S. Management of secondary mitral regurgitation:from drugs to devices. Heart. 2024;110:1099-1106.

6. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement:an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic´J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2:a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

8. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2022;145:e1033.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2022;146:e185.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2023;147:e674]. Circulation. 2022;145:e895-e1032.

9. Abraham WT, Psotka MA, Fiuzat M, et al. Standardized Definitions for Evaluation of Heart Failure Therapies:Scientific Expert Panel From the Heart Failure Collaboratory and Academic Research Consortium. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:961-972.

10. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century:a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [published correction appears in Stroke. 2019;50:e239]. Stroke.2013;44:2064-2089.

11. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Glob Heart. 2018;13:305-338.

12. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560.

13. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188.

14. Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, et al. Transcatheter Valve Repair in Heart Failure with Moderate to Severe Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med.2024;391:1799-1809.

15. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307-2318.

16. Obadia JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, Leurent G, et al. Percutaneous Repair or Medical Treatment for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med.2018;379:2297-2306.

17. Iung B, Armoiry X, Vahanian A, et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation:outcomes at 2 years. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1619-1627.

18. Ponikowski P, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, et al. Hospitalization of Symptomatic Patients With Heart Failure and Moderate to Severe Functional Mitral Regurgitation Treated With MitraClip:Insights From RESHAPE-HF2. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:2347-2363.

19. Grayburn PA, Sannino A, Packer M. Proportionate and Disproportionate Functional Mitral Regurgitation:A New Conceptual Framework That Reconciles the Results of the MITRA-FR and COAPT Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:353-362.

20. Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS. Percutaneous repair of moderate-to-severe or severe functional mitral regurgitation in patients with symptomatic heart failure:Baseline characteristics of patients in the RESHAPE-HF2 trial and comparison to COAPT and MITRA-FR trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26:1608-1615.

21. Nappi F, Singh SSA, Bellomo F.Exploring the Operative Strategy for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation:A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int.2021;2021:3466813.

22. American College of Cardiology. STS/ACC TVT Registry Analysis Finds TMVr Safe and Effective in Real-World Setting. ACC. 2023 Mar 5. Available at: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2023/03/01/22/45/Sun-1215pm-sts-acc-tvt-acc-2023. Accessed 1 Jul 2025.

23. Bernardi FLM, Ribeiro HB, Nombela-Franco L, et al. Recent Developments and Current Status of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Practice in Latin America - the WRITTEN LATAM Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2022;118:1085-1096.

24. Bana A. TAVR-present, future, and challenges in developing countries. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;35:473-484.

25. Steitieh D, Zaidi A, Xu S, et al. Racial Disparities in Access to High-Volume Mitral Valve Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair Centers. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1:100398.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: De-escalation from prasugrel and ticagrelor to clopidogrel in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a strategy aimed at reducing bleeding. This study evaluates whether VerifyNow (Werfen, Spain)–guided de-escalation, based on platelet aggregation measurement, provides a therapeutic benefit in ACS management.

Methods: This ongoing multicenter, prospective, randomized 1:1 trial will enroll 634 patients with ACS who underwent revascularization with a sirolimus-eluting stent and were discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy with ticagrelor or prasugrel. Only those patients with a very low platelet reactivity level (platelet reactivity units ≤ 30) based on VerifyNow 1 month after discharge will be included. The primary endpoint is a composite of cardiovascular death, nonfatal acute myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and bleeding at 1-year follow-up.

Results: The EPIC17-VERONICA study (NCT04654052) will reveal the efficacy profile of the de-escalation strategy, based on the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test, and determine the role of this device in the selection of patients who are eligible to benefit from this strategy.

Conclusions: This study will determine whether platelet function testing provide clinical benefit in the management of patients with ACS.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. Antiplatelet therapy. Platelet function test. Bleeding.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La desescalada desde prasugrel y ticagrelor a clopidogrel en pacientes tras intervencionismo coronario percutáneo por síndrome coronario agudo (SCA) constituye una de las estrategias para intentar disminuir las hemorragias. El objetivo de este estudio es averiguar si dicha desescalada guiada por la prueba de agregación plaquetaria VerifyNow (Werfen, España) tiene un efecto beneficioso en el tratamiento del SCA.

Métodos: Estudio multicéntrico, prospectivo y aleatorizado 1:1, en curso. Se incluirán 634 pacientes con SCA y revascularización con stent de sirolimus que sean dados de alta con doble terapia antiagregante con ticagrelor o prasugrel. Solo se incluirán aquellos con un nivel de reactividad plaquetaria muy bajo (unidades de reactividad plaquetaria ≤ 30) basado en VerifyNow al mes del alta. El objetivo primario es un combinado de muerte por causa cardiovascular, infarto agudo de miocardio no fatal, accidente cerebrovascular no fatal y sangrado en un seguimiento a 1 año.

Resultados: El estudio EPIC17-VERONICA (NCT04654052) permitirá averiguar la eficacia de la estrategia de desescalada basada en la prueba de agregación plaquetaria VerifyNow, además de conocer el papel de este dispositivo en la selección de los pacientes candidatos a beneficiarse de esta estrategia.

Conclusiones: Este estudio determinará si las pruebas de función plaquetaria aportan beneficio en el tratamiento tras el SCA.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. Terapia antiagregante. Prueba de función plaquetaria. Sangrado.

Abbreviations

ACS: acute coronary syndrome. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. PRU: platelet reactivity units.

INTRODUCTION

Following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a 12-month regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 receptor inhibitor and acetylsalicylic acid is recommended, regardless of the type of stent implanted, except when contraindicated.1 Although prasugrel and ticagrelor are preferred over clopidogrel in this setting, there is ongoing debate regarding the potency and duration of dual antiplatelet therapy. This controversy stems from the fact that most patients concurrently face 2 opposing and potentially fatal risks—ischemic and hemorrhagic—which must be carefully balanced on an individual basis.

The introduction of stents with reduced thrombogenicity, together with evidence that thrombotic risk is highest during the first few months after PCI while hemorrhagic risk remains relatively constant throughout time, has led to research efforts focused on minimizing bleeding complications. These strategies include shortening dual antiplatelet therapy, using P2Y12 inhibitors as monotherapy, and implementing de-escalation strategies.2,3

De-escalation consists of switching from prasugrel or ticagrelor to clopidogrel and can be guided (using genetic or platelet function testing) or unguided. Because this strategy may increase ischemic events, it is not recommended within the first month after PCI.1

In the TOPIC trial,4 the unguided de-escalation strategy initiated 1 month after ACS significantly reduced hemorrhagic events (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] grade ≥ 2 bleeding events) at 1 year without increasing the ischemic ones. In the TROPICAL-ACS trial,5 the platelet function testing–guided de-escalation from prasugrel to clopidogrel 2 weeks after revascularization was noninferior to standard therapy, showing a trend toward fewer hemorrhages at 12 months and a similar rate of thrombotic events.1,2,6 In the TALOS-AMI trial,7 12-month event rates were lower, primarily because of fewer hemorrhagic events among patients who underwent unguided de-escalation 1 month after ACS. Table 1 summarizes these studies.

Table 1. De-escalation clinical trials in patients with acute coronary syndrome

| TOPIC (2017)4 | TROPICAL-ACS (2018)5 | TALOS-AMI (2021)12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | n = 645 | n = 2610 | n = 2697 |

| Design | Open-label, single-center, randomized, superiority trial | Open-label, multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial | Open-label, multicenter, randomized, noninferiority trial |

| Strategy | Standard therapy vs unguided de-escalation | Standard therapy vs platelet function testing–guided therapy (Multiplate device) | Standard therapy vs unguided de-escalation |

| Control group | Continued dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and ticagrelor or prasugrel | Continued dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and prasugrel | Continued dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and ticagrelor |

| Experimental group | De-escalation to acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel | 1-week regimen of prasugrel, followed by 1-week regimen of clopidogrel and either prasugrel or clopidogrel from day 14 onward, according to platelet function testing results | De-escalation to acetylsalicylic acid and clopidogrel |

| Time from revascularization to de-escalation | 1 month | 2 weeks | 1 month |

| Follow-up | 1 year | 1 year | 1 year |

| Primary endpoint | Cardiac death, emergency revascularization, stroke, or BARC ≥ 2 bleeding events | Cardiac death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or BARC ≥ 2 bleeding events | Cardiac death, myocardial infarction, stroke, or BARC ≥ 2 bleeding events |

| Results | 13.4% in experimental group vs 26.3% in control group (HR, 0.48; 95%CI, 0.34–0.68; P < .01) | 7.3% in experimental group vs 9.0% in control group (HR, 0.81; 95%CI, 0.62–1.06; P = .0004) | 4.6% in experimental group vs 8.2% in control group (HR, 0.55; 95%CI, 0.42–0.76; P < .0001) |

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; HR, hazard ratio. |

|||

After the positive results of the TOPIC trial, the VerifyNow to optimise platelet inhibition in coronary acute syndrome (EPIC17-VERONICA) trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT04654052) aims to further refine this strategy by only applying de-escalation to patients with excessive antiplatelet effects from prasugrel or ticagrelor after the first month who are at theoretical risk of hemorrhage based on the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test (Werfen, Spain). Thus, patients demonstrating an adequate pharmacologic response will continue prasugrel or ticagrelor therapy for 1 year, whereas those with very low platelet reactivity after a 1-month regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy with these agents constitute the target population of this study.

METHODS

Design

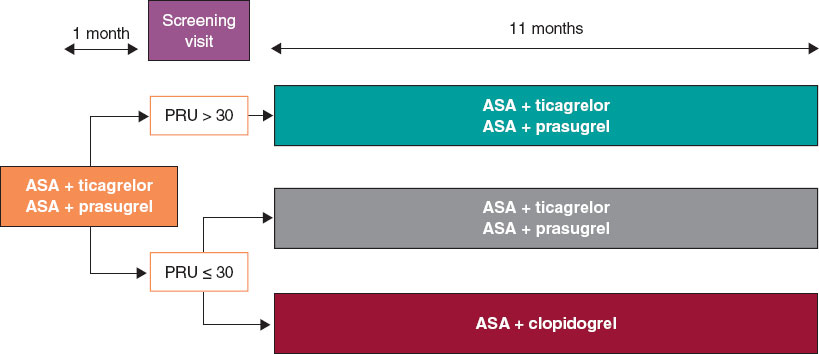

We are conducting a multicenter, prospective, randomized clinical trial at 16 Spanish centers. Based on the results of the platelet aggregation test for P2Y12 inhibition (platelet reactivity units [PRU]) using the VerifyNow system, patients with very low platelet reactivity (PRU ≤ 30) are randomized in a 1:1 ratio to either continue treatment with ticagrelor or prasugrel, or to de-escalate to clopidogrel. Patients with PRU > 30 are not randomized. The study flowchart is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. AAS, acetylsalicylic acid; PRU, platelet reactivity units.

The study is being conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and has been approved by the central ethics committee (Comité del Bierzo, León, Spain) and endorsed by the ethics committees of all participant centers. The appendix lists the participant centers and principal investigators.

The study sponsor (Fundación para la Educación en Procedimientos de Intervencionismo en Cardiología [EPIC]) is fully responsible, together with the principal investigators, for data management and confidentiality.

Population

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 2 summarizes the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Briefly, all patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a sirolimus-eluting stent and a bioresorbable polymer during hospitalization and discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and ticagrelor or prasugrel are eligible for inclusion.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Patients > 18 years |

| Patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous revascularization with a sirolimus-eluting stent with a bioresorbable polymer and discharged on dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and ticagrelor or prasugrel |

| Signed informed consent |

| Exclusion criteria |

| History of intracranial hemorrhage |

| Contraindication to acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor |

| Major ischemic or bleeding events during the first month of antiplatelet therapy |

| Thrombocytopenia < 50 000/µL |

| Permanent oral anticoagulation |

| Pregnancy or breastfeeding |

| Inability to complete the 1-year follow-up |

| Life expectancy < 24 months |

Written informed consent must be obtained before the platelet aggregation tes is performed.

Study protocol and randomization

Eligible patients are scheduled for P2Y12 receptor inhibition testing with the VerifyNow system between 30 and 40 days after hospital discharge. Measurements are obtained at least 6 hours after the administration of the last P2Y12 inhibitor dose. Patients with PRU ≤ 30 (very low platelet reactivity) are randomized in a 1:1 ratio using an electronic system to either continue their current treatment or de-escalate to clopidogrel, 75 mg once daily. De-escalation is preceded by a loading dose of 600 mg administered 24 hours after the last dose of ticagrelor or 75 mg 24 hours after the last dose of prasugrel, in accordance with the 2017 European Society of Cardiology clinical practice guidelines.8

The remaining patients with PRU > 30 are not randomized, and their dual antiplatelet therapy remains unchanged from discharge.

Clinical follow-up

Patients in the 2 randomized groups undergo telephone follow-up to monitor clinical events at 2, 5, 8, and 11 months after enrollment, corresponding to 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after hospital discharge.

For patients with PRU > 30 on the 1-month VerifyNow platelet aggregation test who are not randomized, only baseline characteristics are recorded, and no further follow-up is conducted.

Protocol of the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test

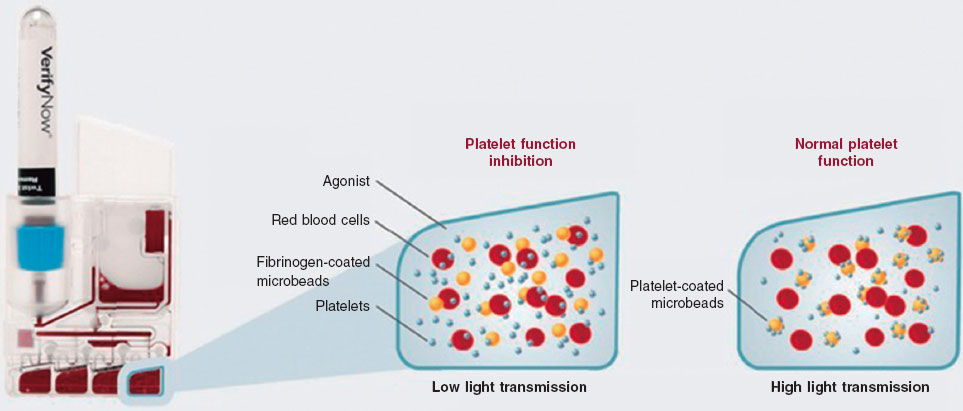

The VerifyNow system determines platelet activity by measuring in vitro aggregation in a blood sample exposed to specific agonists. This optical detection instrument (figure 2), which operates on a turbidimetric principle, uses single-use cartridges. In this study, PRUTest-specific kits are employed. (Werfen, Spain) to assess platelet aggregation while on P2Y12 receptor inhibitor therapy (ticagrelor, prasugrel, and clopidogrel). Each PRUTest kit contains lyophilized microbeads coated with fibrinogen, platelet activators, and a buffered solution. The test is based on the ability of activated platelets to bind fibrinogen-coated microbeads. Light transmission increases as activated platelets bind to and aggregate with the fibrinogen-coated microspheres. The kit measures this change in the optical signal and reports the results in PRU units (figure 3).

Figure 2. VerifyNow system. Reproduced with permission from Werfen.

Figure 3. Performance of the VerifyNow system based on light transmission aggregometry. Light transmission increases as activated platelets bind and aggregate to the fibrinogen-coated microbeads in the kit. Therefore, high light transmission (corresponding to elevated platelet reactivity unit [PRU] values) indicates normal platelet function, whereas low light transmission (decreased PRU values) reflects platelet inhibition induced by the tested drugs.

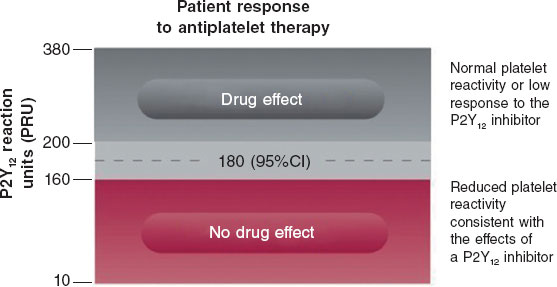

An antiplatelet effect of the drug is considered present with PRU ≤ 180 (figure 4). Only patients with PRU ≤ 30 are randomized, as these are considered to have very low platelet reactivity while on antiplatelet therapy.

Figure 4. Reference levels for platelet reactivity units (PRU). 95%CI, 95% confidence interval.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study is to compare the efficacy of de-escalation from ticagrelor or prasugrel to clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI in the ACS setting, using the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test vs standard dual antiplatelet therapy at the 1-year follow-up. The rate of net adverse cardiovascular events is the primary endpoint of the study, defined as a composite of cardiac death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, nonfatal stroke, and hemorrhage (defined as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] grade ≥ 2 bleeding events). The BARC scale is shown in table S1.

Furthermore, the study aims to compare several secondary endpoints (table 3), such as the occurrence of ischemic events during follow-up: cardiac death and all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, stent thrombosis, and need for emergency revascularization. Moreover, the hemorrhage rate (defined as BARC grade ≥ 2 bleeding events) will be compared. The definitions of all study endpoints are shown in table S2.

Table 3. Endpoints of the study

| Primary endpoint |

|---|

| To compare the percentage of net adverse cardiovascular events between the 2 subgroups of patients with low platelet reactivity (PRU ≤ 30) who were randomized to de-escalation to clopidogrel vs standard therapy |

| Secondary endpoints |

| To compare the rate of cardiac death between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of all-cause mortality between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of acute myocardial infarction between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of stroke between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of stent thrombosis between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of emergency revascularization between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

| To compare the rate of bleeding events (defined as BARC ≥ 2) between the 2 randomized patient subgroups |

|

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; PRU, platelet reactivity units. |

Statistics

Sample size calculation

Sample size was calculated for the randomized clinical trial cohort. The total number of patients (including those not randomized with PRU > 30) will depend on the total required to reach the estimated sample size for the randomized clinical trial.

We estimate a smaller difference in event rates across the groups than that observed in the TOPIC trial,4 specifically, 14% in the de-escalation group vs 22% in the standard therapy group. Assuming a significance level of 0.05, a power of 80%, a 2-tailed P-value and a 10% loss to follow-up, a total of 634 randomized patients (317 per group) will be required.

Statistical analysis plan

Quantitative variables will be expressed as mean and standard deviation if normally distributed, or as median and interquartile range otherwise. Categorical variables will be expressed as absolute values and percentages. Study data will be analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables, and Fisher’s exact or chi-square tests for categorical variables, as appropriate. Nonparametric tests will be used for variables that are not normally distributed or cannot be normalized. For the main outcome measure, Kaplan-Meier survival curves with log-rank statistics will be presented for prespecified criteria, and multivariable Cox regression will be performed to adjust for known risk factors and potential confounders. Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals will be reported for all statistically significant variables.

Intention-to-treat (according to randomization assignment) and per-protocol analyses (in case of crossover) will be conducted. The former will serve as the study primary analysis.

DISCUSSION

The EPIC17-VERONICA trial aims to demonstrate the efficacy of a VerifyNow platelet aggregation test-guided de-escalation strategy in reducing hemorrhagic events without increasing ischemic events in patients with ACS who have undergone percutaneous revascularization and exhibit very low platelet reactivity after the first month of treatment with prasugrel or ticagrelor.

The initial lack of expected results from platelet function testing to identify patients at risk for thrombotic events while on clopidogrel in the GRAVITAS,9 TRIGGER-PCI,10 and ARCTIC11 trials relegated its use to a class IIb recommendation in the European Society of Cardiology antiplatelet guidelines for determining the optimal timing of cardiac surgery after ACS.8 However, the 1-year results of the large-scale multicenter ADAPT-DES trial12 with 8500 PCI patients demonstrated that platelet reactivity assessed with the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test is an independent predictor of bleeding events.

In the TOPIC4 and TALOS-AMI7 trials, the unguided de-escalation strategy significantly reduced bleeding events without increasing ischemic events. In the TROPICAL-ACS5 trial, this platelet aggregation test–guided de-escalation strategy showed a trend toward fewer hemorrhages, with a similar rate of thrombotic complications.

The EPIC17-VERONICA study further seeks to improve the application of this de-escalation strategy by using the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test to identify patients with very low platelet reactivity (PRU ≤ 30) as those most likely to benefit from de-escalation.

CONCLUSIONS

The EPIC17-VERONICA trial has been designed to investigate the efficacy of de-escalating from the most potent antiplatelet agents (ticagrelor and prasugrel) to clopidogrel after the first month of therapy in patients with ACS and very low platelet reactivity, aiming to reduce bleeding events without increasing ischemic complications. Furthermore, it will provide evidence on the clinical utility of the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test for patient selection.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study is being conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki on clinical research and has been approved by the central ethics committee (Comité del Bierzo, León, Spain) and endorsed by the ethics committees of all participant centers. Written informed consent is required prior to performing ant platelet aggregation measurements. Sex and gender bias considerations have been addressed.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

C. Garilleti Cámara and I. Lozano Martínez-Luengas drafted the manuscript; the remaining authors critically revised the document and approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.M. de la Torre Hernández is Editor-in-Chief of REC: Interventional Cardiology; A. Pérez de Prado is Associate Editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology. In both cases, the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- De-escalation from the most potent antiplatelet agents to clopidogrel is one of the strategies used to reduce hemorrhage after percutaneous revascularization in acute coronary syndrome. This de-escalation can be performed guided or unguided by genetic or platelet function testing.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The VERONICA trial is the first to use the VerifyNow platelet aggregation test to select patients eligible for de-escalation.

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

2. Angiolillo DA, Galli M, Collet JP, Kastrati A, O’Donoghue MO. Antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention. 2022; 17:e1371-e1396.

3. Angiolillo DJ. The Evolution of Antiplatelet Therapy in the Treatment of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Drugs. 2012;72:2087-2116.

4. Cuisset T, Deharo P, Quilici J, et al. Benefit of switching dual antiplatelet therapy after acute coronary syndrome: the TOPIC (timing of platelet inhibition after acute coronary syndrome) randomized study. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3070-3078.

5. Sibbing D, Aradi D, Jacobshagen C, et al. Guided de-escalation of antiplatelet treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TROPICAL-ACS): a randomised, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1747-1757.

6. Gorog DA, Ferreiro JL, Ahrens I, et al. De-escalation or abbreviation of dual antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention: a Consensus Statement from an international expert panel on coronary thrombosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:830-844.

7. Kim CJ, Park MW, Kim MC, et al. Unguided de-escalation from ticagrelor to clopidogrel in stabilised patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (TALOS-AMI): an investigator-initiated, open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet. 2021;398:1305-1316.

8. Valgimigli A del G de TM, Bueno H, Byrne RA, et al. Actualización ESC 2017 sobre el tratamiento antiagregante plaquetario doble en la enfermedad coronaria, desarrollada en colaboración con la EACTS. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:42.e1-42.e58.

9. Price MJ, Berger PB, Teirstein PS, et al. Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial. JAMA. 2011;305:1097-105. Erratum in: JAMA. 2011;305;2174. Stillablower, Michael E [corrected to Stillabower, Michael E]. PMID: 21406646.

10. Trenk D, Stone GW, Gawaz M, et al. A Randomized Trial of Prasugrel Versus Clopidogrel in Patients With High Platelet Reactivity on Clopidogrel After Elective Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With Implantation of Drug-Eluting Stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:2159-2164.

11. Collet JP, Cuisset T, Rangé G, et al. Bedside Monitoring to Adjust Antiplatelet Therapy for Coronary Stenting. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2100-2109.

12. Sibbing D, Schulz S, Braun S, et al. Antiplatelet effects of clopidogrel and bleeding in patients undergoing coronary stent placement. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:250-256.

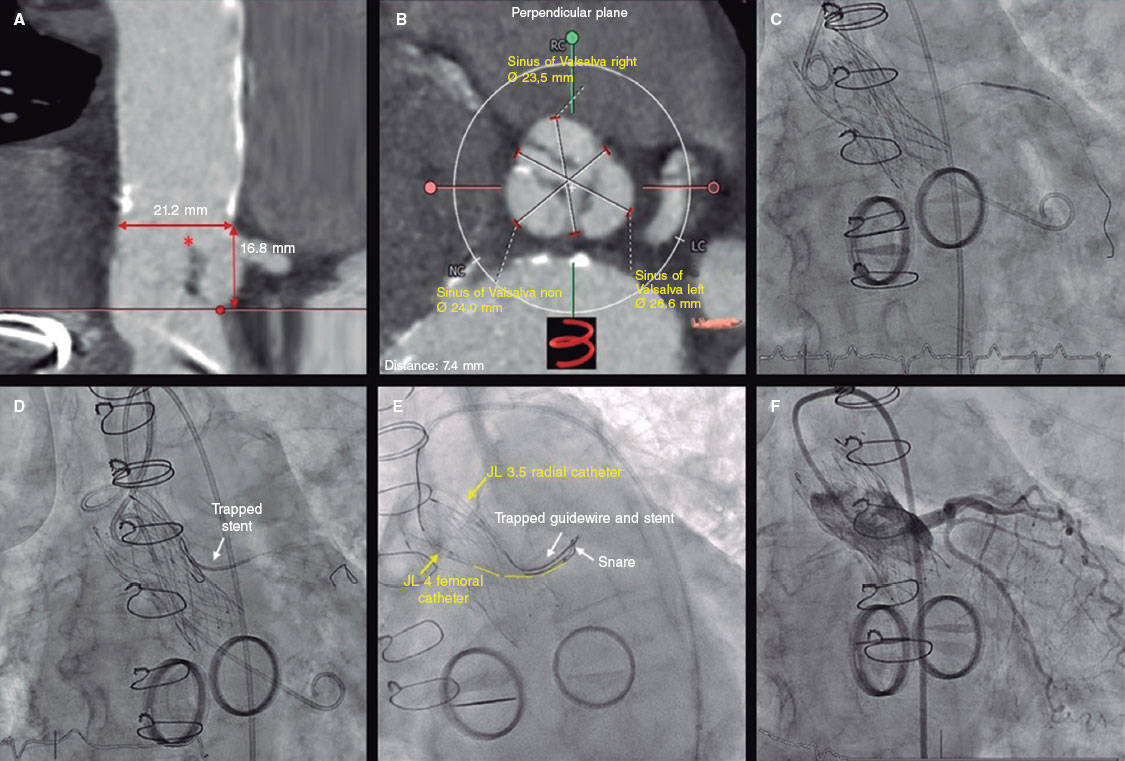

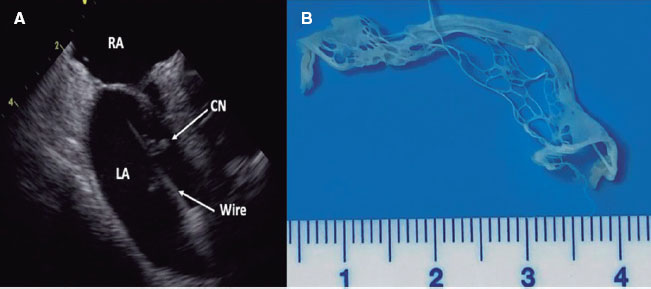

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Calcified coronary nodules (CN) are among the most challenging lesions for percutaneous coronary intervention, as drug-eluting stents (DES) frequently result in suboptimal expansion, malapposition, and recurrent adverse events. Although intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) provides effective plaque modification, the optimal definitive strategy remains unclear. Drug-eluting balloons (DEB) have demonstrated potential in the treatment of complex lesions in which stent implantation may be less desirable. This trial aims to compare the safety and efficacy profile of DEB vs DES after IVL in patients with CN.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective, investigator-initiated, multicenter, non-inferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Results: A total of 128 patients with de novo CN confirmed by intracoronary imaging in vessels measuring 2.5 mm to 4.0 mm in diameter will be enrolled across 10 high-volume percutaneous coronary intervention centers. After lesion preparation with IVL, patients will be randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive a DEB or a DES. The co-primary endpoints are late lumen loss and net luminal gain at 9 ± 1 months of angiographic follow-up, both assessed by an independent core laboratory. Secondary endpoints include procedural, angiographic, and clinical outcomes, adjudicated by a blinded clinical events committee. Clinical follow-up will be conducted at 1 month, 1 year, and 2 years.

Conclusions: The DEBSCAN-IVL trial will provide the first randomized evidence comparing DEB and DES after IVL for CN.

Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06657833.

Keywords: Calcified nodule. Intravascular lithotripsy. Drug-eluting balloons. Drug-eluting stents. Complex percutaneous coronary intervention.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Los nódulos coronarios calcificados (NC) se encuentran entre las lesiones más desafiantes para la intervención coronaria percutánea, ya que los stents farmacoactivos (SFA) con frecuencia presentan expansión subóptima, mala aposición y eventos adversos recurrentes. La litotricia intravascular (LIV) permite una modificación eficaz de la placa, pero la estrategia definitiva óptima sigue sin estar clara. Los balones farmacoactivos (BFA) han mostrado resultados prometedores en lesiones complejas en las que la implantación de stents podría ser menos favorable. Este ensayo tiene como objetivo comparar la seguridad y la eficacia del BFA frente al SFA después de la LIV en pacientes con NC.

Métodos: Ensayo clínico prospectivo, por iniciativa del investigador, multicéntrico, de no inferioridad y aleatorizado.

Resultados: Un total de 128 pacientes con NC de novo confirmados mediante imagen intracoronaria en vasos de 2,5-4,0 mm de diámetro serán incluidos en 10 centros de intervencionismo coronario percutáneo de alto volumen. Tras la preparación de la lesión con LIV, los pacientes serán aleatorizados 1:1 para ser tratados con BFA o SFA. Los criterios de valoración coprimarios son la pérdida luminal tardía y la ganancia luminal neta en el seguimiento angiográfico a 9 ± 1 meses, evaluadas por un laboratorio central independiente. Los criterios secundarios incluyen resultados procedimentales, angiográficos y clínicos, adjudicados por un comité de eventos clínicos enmascarado. El seguimiento clínico se realizará a 1 mes, 1 año y 2 años.

Conclusiones: El ensayo DEBSCAN-IVL proporcionará la primera evidencia de comparación de BFA y SFA aleatorizados después de IVL en NC.

Registrado en ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06657833.

Palabras clave: Nódulo calcificado. Litotricia intravascular. Balón farmacoactivo. Stent farmacoactivo. Intervención coronaria percutánea compleja.

Abreviaturas

CN: calcified coronary nodule. DEB: drug-eluting balloon. DES: drug-eluting stent. IVL: intravascular lithotripsy. OCT: optical coherence tomography. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Calcified coronary nodules (CN) represent the most complex type of calcified lesion for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), as they are associated with worse angiographic and clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation.1-8

Intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) has shown favorable results in this context.9 However, stent implantation after IVL may not always be the best treatment option due to suboptimal stent expansion and severe malapposition in a non-negligible percentage of patients which, along with possible nodule protrusion through the stent struts, may be associated with an increased need for new target lesion revascularization (TLR), and a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).10-12

Drug-eluting balloons (DEB) have demonstrated to be a safe and effective alternative to DES in various settings, especially in those in which stenting is associated with worse outcomes, such as small vessel disease and in-stent restenosis.13 Therefore, their use has increased exponentially in recent years and has expanded to other lesion types.14

In the specific setting of calcified lesions, there are some data on the safety and efficacy profile of DEB after an adequate plaque modification.15-19 Moreover, in this setting, DEB have shown similar clinical outcomes with favorable late lumen loss rate compared with DES.20-23

Despite the increasing use of DEB in calcified lesions, evidence on the safety and efficacy profile of CN treatment is lacking. In this setting, where the risj of suboptimal stent expansion and apposition—and the consequent likelihood of MACE— is higher,24 a leave-nothing-behind strategy using DEB following optimal plaque modification technique may be a more appealing approach.Therefore, our aim is to compare the safety and efficacy profile of the use of DEB or DES after IVL in CN within the context of a randomized controlled trial.

METHODS

Patients and study design

The DEBSCAN-IVL trial is an investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial including 10 high-volume centers.

Patients will be randomized to receive a DEB or a DES after optimal treatment with IVL if they meet all the inclusion criteria and have no exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria are age ≥ 18 years with a clinical indication for PCI (presenting with chronic or acute coronary syndromes) in a CN-induced de novo severe coronary lesion (confirmed via intracoronary imaging) in vessels with a reference diameter between 2.5 mm and 4.0 mm. Patients who meet at least 1 of the following conditions will be excluded: inability to provide oral and written informed consent or unwillingness to return for systematic angiographic follow-up; pregnant or breastfeeding patients; cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest at the time of the index procedure; inability to maintain dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 month; life expectancy < 1 year; index lesion located at the left main coronary artery or in an aorto-ostial location; target lesion previously treated with stents or DEB or with high thrombus burden at the time of PCI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] thrombus grade ≥ 3).

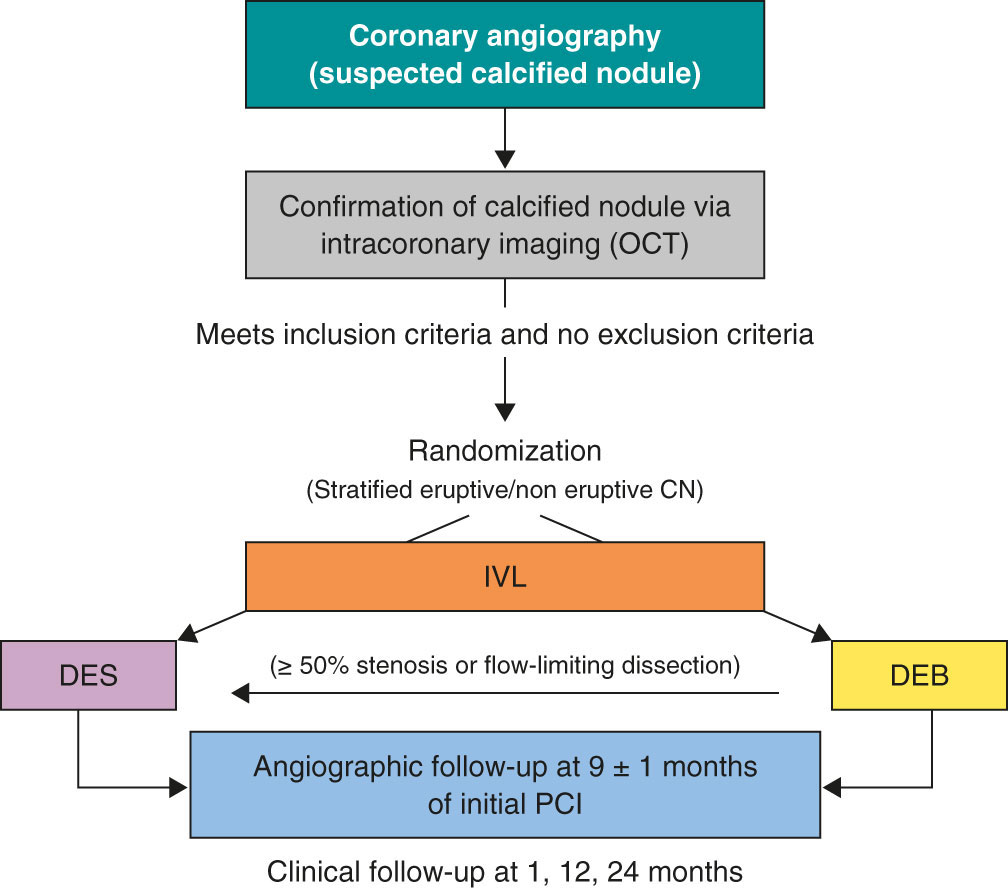

Patients who meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria will be treated with IVL and randomized to receive final therapy with DEB or DES. Randomization will occur via a web-based system. The complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in table 1, and the study flowchart in figure 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Patients must meet all inclusion criteria:

|

Patients must not meet any criteria:

|

|

DEB, drug-eluting balloon; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

|

Figure 1. Central illustration. Study design flowchart. CN, calcified coronary nodule; DEB, drug-eluting balloons; DES, drug-eluting stents; IVL, intravascular lithotripsy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The endpoint of this study is to evaluate and compare the safety and efficacy profile of DEB or DES as final treatment strategies for CN previously modified by IVL.

Co-primary endpoints will be the late lumen loss (LLL) and net luminal gain at 9 ± 1 months of angiographic follow-up, as assessed by an independent core laboratory, with a non-inferiority hypothesis between the 2 groups. LLL is defined as the difference between postoperative and follow-up minimal lumen diameter, whereas net gain is defined as the difference between follow-up and preoperative minimal lumen diameter, according to the latest Drug Coated Balloon Academic Research Consortium Consensus Document.25

Secondary endpoints of the study will include procedural, angiographic and clinical outcomes. Procedural endpoints will include the rate of crossover between treatment groups, angiographic success (defined as final TIMI grade-3 flow and a residual final percent diameter stenosis < 30% in the DEB group or < 20% in the DES group), device success (defined as angiographic success without crossover between treatment group), procedural success (defined as angiographic success without the occurrence of severe procedural complications, including cardiac death, target vessel perioperative myocardial infarction [MI], need for new clinically driven TLR, stent thrombosis [ST], stroke, flow-limiting dissection or vessel perforation). Angiographic endpoints will include the minimal lumen diameter measured immediately after the intervention and at the time of angiographic follow-up, the residual percent diameter stenosis at both timeframes, and the rate of binary restenosis, defined as a luminal diameter reduction o≥ 50% during follow-up.25 Secondary endpoints will include procedural adverse events (such as dissection, perforation, acute vessel occlusion, slow flow or no-reflow, and intraoperative thrombosis), major hemorrhagic events (classified as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] type ≥ 3),26 and hemodynamic instability (requiring unplanned administration of vasopressors, inotropes, or ventricular support devices), cardiac death, target lesion-related MI (TL-MI), need for TLR, and ST, and MACE (defined as a composite of cardiac death, TL-MI, and TLR). TLR and ST are defined according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria.27 MACE and its components will be assessed during the index hospitalization and at 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up visits. Detailed endpoints definitions are shown in appendix S1.

Primary outcome assessment will be conducted by a central independent core laboratory. All medical data will be anonymized and stored, and confidentiality will be protected at any time in full compliance with the current legislation. The clinical events committee (CEC) and the independent core laboratory will be blinded to the treatment group. Secondary outcomes will be assessed via centralized angiographic analysis and structured clinical follow-up, either in person or via telephone, at scheduled time points.

Devices

- – IVL: Shockwave Balloon (Shockwave Medical, United States).

- – Optical coherence tomography (OCT) or intracoronary ultrasound (IVUS) system, based on availability at each participating center.

- – DEB: paclitaxel-eluting balloon (Pantera Lux, Biotronik, Switzerland)

- – DES: new-generation zotarolimus eluting stent (Onyx Frontier, Medtronic, United States).

Procedure

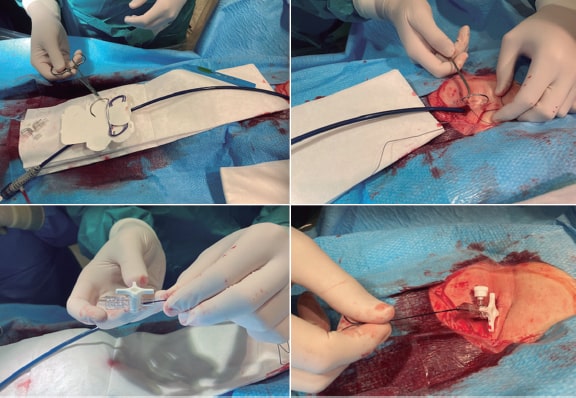

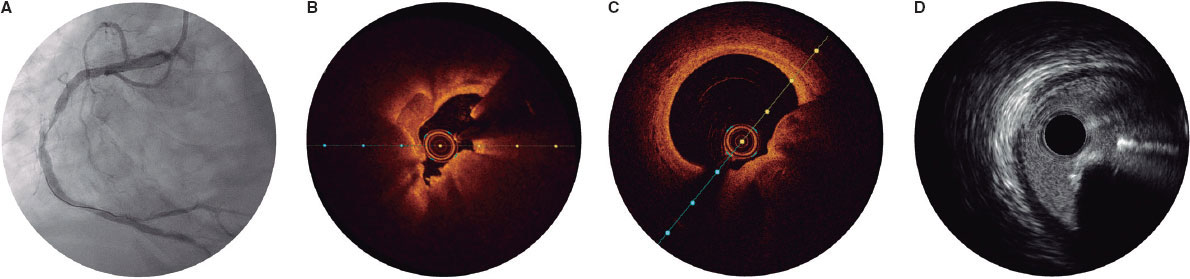

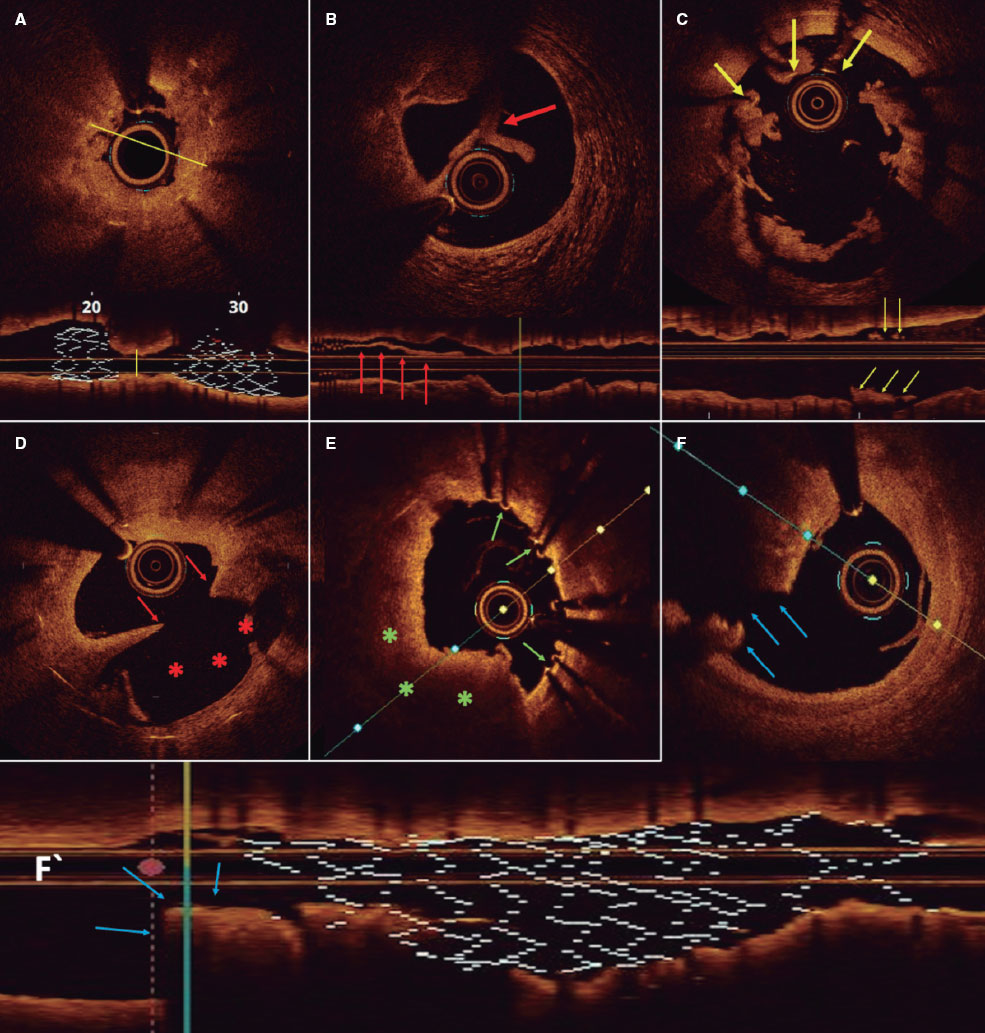

When a CN is suspected on coronary angiography, intracoronary imaging—preferably OCT, with IVUS as an alternative—will be performed to confirm the diagnosis. After confirmation of a CN in the target lesion, patients will be randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive a DEB or a DES. Randomization will be stratified to ensure a balanced distribution of eruptive and non-eruptive nodules across both treatment groups. A CN (figure 2) will be defined as a calcified segment with an accumulation of protruding nodular calcification (small calcium deposits) with disruption of the fibrous cap (eruptive CN) or an intact thick fibrous cap (non-eruptive CN).28-30

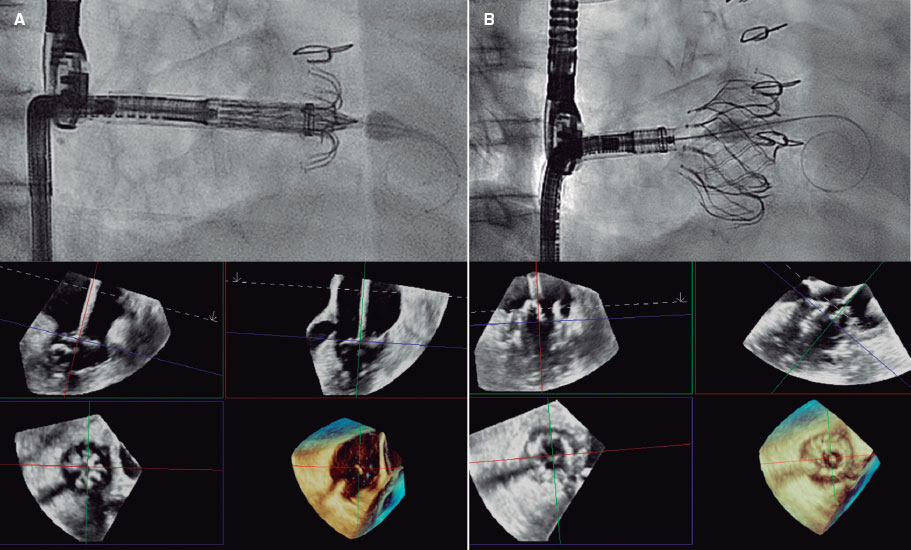

Figure 2. Calcified nodule appearance on angiography (A), optical coherence tomography (eruptive [B] and non-eruptive [C]) and intravascular ultrasound (D).

All patients will be treated with IVL, using a balloon sized 1:1 to the vessel reference diameter. A minimum of 80 pulses per lesion is recommended. If the IVL balloon cannot cross the lesion, predilation with smaller balloons is permitted. Additionally, the use of adjuvant techniques such as rotational atherectomy or excimer laser coronary atherectomy will be allowed only when deemed necessary to facilitate IVL balloon crossing. Postdilation with a non-compliant balloon after IVL is recommended before proceeding with the final assigned treatment modality.

Once optimal lesion preparation has been achieved, defined as > 80% balloon expansion in 2 orthogonal projections with a balloon sized 1:1 to the vessel, patients will receive a DEB or a DES, according to their initial randomization. If a patient randomized to the DEB group experiences a flow-limiting dissection or exhibits a percent diameter stenosis > 50%, conversion to DES implantation will be permitted at the operator’s discretion. Similarly, any crossover from DES to DEB will be documented, along with the reasons for these procedural decisions.

It is recommended that the DEB reach the target lesion within 2 minutes, as drug loss may occur during transit.13 Thus, operators need to anticipate difficulties in reaching the target lesion (proximal coronary disease or tortuosity) and ensure optimal support prior to using the DEB. If difficulties in reaching the target lesion are anticipated, the use of guide extension catheters is recommended. The recommended DEB inflation time is 60 seconds.

The PCI will be performed according to current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, including perio- and postoperative antithrombotic management.31,32 Patients should ideally receive dual antiplatelet therapy at least 2 to 4 hours prior to the PCI to ensure optimal platelet inhibition. In cases where this is not feasible, administration of IV antiplatelet agents, such as acetylsalicylic acid with or without cangrelor, immediately before the procedure is recommended.

Intracoronary imaging with either OCT or IVUS (the same imaging modality that was initially used) is recommended at the end of the procedure.

Angiographic analysis

Quantitative coronary imaging and intracoronary analysis of baseline and follow-up angiographies will be conducted by an independent central laboratory (Barcicore, Spain). At least 2 well-selected orthogonal views—free of foreshortening and side-branch overlap—focused on the target lesion are required after intracoronary nitroglycerine administration. These views should be obtained before treatment, after the intervention, and during follow-up angiography to ensure consistent angulation and enable accurate, reproducible measurements.

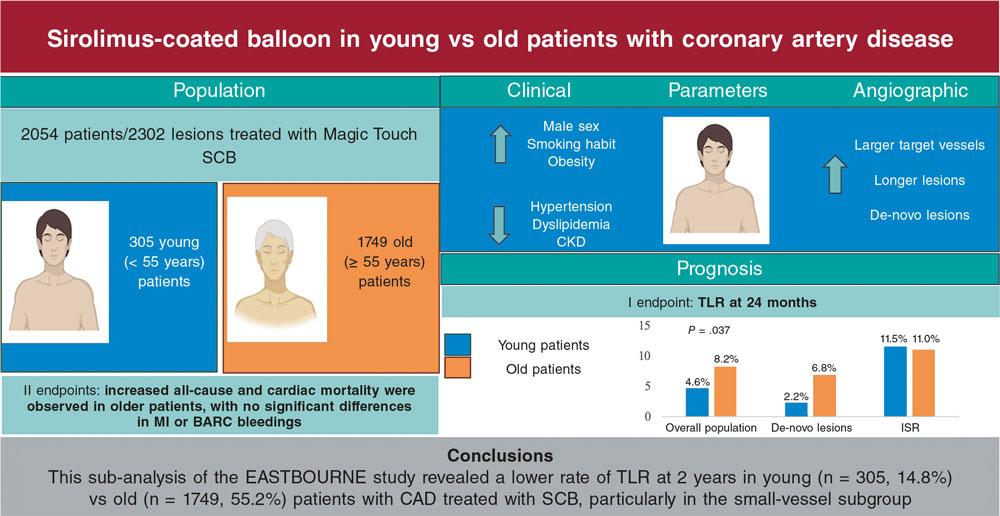

Follow-up