Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Thrombus removal in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can be challenging in the presence of a large thrombus burden. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA) is an adjuvant device capable of vaporizing thrombus. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in PCI.

Methods: Patients with STEMI undergoing PCI with concomitant use of ELCA for thrombus removal were retrospectively identified at our center. Data were collected on the device efficacy and its contribution to overall procedural success. Additionally, ELCA-related complications and major adverse cardiovascular events were recorded at a 2-year follow-up.

Results: ELCA was used in 130 STEMI patients, 124 (95.4%) of whom had a large thrombus burden. TIMI grade flow improved significantly after ELCA: before laser application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases and TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%) cases. After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively (P < .001). Technical and procedural success were achieved in 128 (98.5%) and 124 (95.4%) cases, respectively. The complications included 1 death at the cath lab (0.8%), 1 coronary perforation (0.8%), and 3 distal embolizations (2.3%). At the 2-years follow-up, major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 18.3% of the population.

Conclusions: In the context of STEMI, ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution, with adequate technical and procedural success rates. In the present cohort, ELCA use was associated with a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. Thrombectomy. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La eliminación de trombos durante la intervención coronaria percutánea primaria (ICPp) en el infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST) es un desafío en presencia de una carga trombótica elevada. La angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros (ELCA) es una técnica complementaria que permite vaporizar el trombo. Este estudio evaluó la eficacia y la seguridad de la ELCA en el contexto de la ICPp.

Métodos: Análisis retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes con IAMCEST sometidos a ICPp con ELCA. Se evaluaron la eficacia en la disolución del trombo, la mejoría del flujo, el éxito del procedimiento, las complicaciones asociadas y los acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores durante un seguimiento de 2 años.

Resultados: Se realizó ELCA en 130 pacientes con IAMCEST, de los cuales 124 (95,4%) tenían carga trombótica elevada. El flujo TIMI mejoró significativamente tras la ELCA: previamente era 0 en 79 casos (60,8%) y 1 en 32 casos (24,6%), y se lograron flujos TIMI 2 y 3 en 45 casos (34,6%) y 66 casos (50,8%), respectivamente (p < 0,001). Las tasas de éxito técnico y del procedimiento fueron del 98,5% y el 95,4%, respectivamente. Las complicaciones incluyeron 1 muerte intraprocedimiento (0,8%), 1 perforación coronaria (0,8%) y 3 embolizaciones distales (2,3%). A los 2 años, la tasa de acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores fue del 18,3%.

Conclusiones: La ELCA parece ser una técnica eficaz y segura en el IAMCEST para la disolución del trombo, con altas tasas de éxito técnico y procedimental, baja incidencia de complicaciones y resultados favorables a largo plazo.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. Trombectomía. Angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros.

Abbreviations

ELCA: excimer laser coronary angioplasty. LTB: large thrombus burden. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

INTRODUCTION

In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy, as long as it can be performed within 120 minutes of the electrocardiogram-based diagnosis.1 Many patients with STEMI present with thrombotic occlusion of the infarct-related artery. Therefore, the use of devices aimed at reducing thrombus burden is a reasonable consideration to minimize distal embolization and no-reflow. Persistent no-reflow in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI is associated with the worst in-hospital outcomes and increased long-term mortality.2

While early studies on manual thrombus aspiration suggested benefits in terms of improved myocardial blush grades and ST-segment elevation resolution,3 larger trials comparing manual thrombus aspiration with PCI alone showed no significant reduction in cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, or a New York Heart Association FC IV heart failure within 180 days.4 Consequently, routine aspiration thrombectomy is no longer recommended in patients with STEMI.5

Thrombus removal, particularly when dealing with a large thrombus burden (LTB) in the context of STEMI, remains a critical and sometimes challenging aspect of PCI. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA Coronary Laser Atherectomy Catheter, Koninklijke Philips N.V., The Netherlands) is a well-established adjuvant therapy for coronary interventions. ELCA uses xenon-chloride gas as the lasing medium to produce UV light energy, which is delivered to the target site through an optical fiber. This energy has the ability to ablate inorganic material through photochemical, photothermal, and photomechanical mechanisms.6,7 The microparticles released during laser ablation measure < 10 µm and are absorbed by the reticuloendothelial system, theoretically reducing the risk of microvasculature obstruction.8 These unique characteristics of ELCA have facilitated its use as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI to ablate and remove thrombus.

Although ELCA is part of the therapeutic armamentarium in some PCI-capable centers, literature data is limited on its safety and efficacy profile in this specific scenario. The aim of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ELCA, focusing on its safety and efficacy profile as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI in our center.

METHODS

Data from all patients undergoing PCI with the simultaneous use of ELCA as an adjuvant technique were retrospectively recorded in a dedicated database after each procedure, starting from the introduction of the device in our center. ELCA procedures were performed by 5 interventional cardiologists with dedicated training in the use of the device.

This study was approved by Parque Sanitario Pere Virgili ethics committee (Barcelona, Spain) (reference No.: CEIM 003/2025). For the purposes of this study, we selected the subgroup of patients with STEMI who underwent PCI in which ELCA was used to facilitate thrombus removal.

Thrombus burden was assessed using the thrombus grading classification9 as defined by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) study group, ranging from 0 to 5. A LTB was defined as a thrombus score ≥ 3. According to our internal protocol, ELCA was considered in STEMI patients in the presence of angiographic evidence of LTB, defined as TIMI thrombus grade ≥ 3, particularly if TIMI grade-0–1 flow or, poor visualization of the distal vessel, or as a bailout strategy after unsuccessful manual thrombectomy. Clinical variables were meticulously refined, and follow-up details were obtained through a thorough review of the patients’ health records. Following coronary angiography and successful guidewire crossing of the culprit lesion, ELCA was left at the operator’s discretion. It was used either as a primary device for thrombus removal or as a bailout strategy when manual thrombus aspiration did not improve TIMI grade flow. The selection of catheter size was mainly based on the target vessel diameter and on the characteristics of the vessel and the lesion; a 0.9 mm ELCA catheter is usually used in tortuous anatomies due to its better navigability and in small-caliber vessels, whereas a 1.4 mm catheter is used in selected cases involving larger proximal vessels with straight segments. Catheter size (0.9 mm or 1.4 mm) was selected based on vessel diameter and lesion characteristics. Laser fluence (45-60 mJ/mm²) and pulse repetition rate (25-40 Hz) were chosen as per manufacturer’s recommendations.

Before laser application, the target vessel was flushed with saline solution to prevent interaction between the laser and blood or contrast medium. In all cases, continuous saline infusion was administered during laser delivery to avoid coronary artery wall heating. Laser energy was delivered using an ‘on-off’ technique, consisting of 10-s laser activation cycles interspersed with 5-s pauses. The laser catheter was advanced at a rate of approximately 1 mm/s over a 0.014-in coronary guidewire through the target lesion, following the manufacturer’s recommendations.7,10 After 2–3 laser catheter passes, a follow-up coronary angiography was performed to evaluate the efficacy of laser application and assess the feasibility of stent implantation. TIMI grade flow was recorded after the ELCA procedure (Post-ELCA TIMI grade flow) and once the PCI would have been completed (final TIMI grade flow). Technical success was defined as the ability to advance the laser catheter through the entire target lesion and deliver laser energy successfully. Procedural success was defined as achieving a final TIMI grade ≥ 2 flow without any major cath lab-related complications, such as death, coronary perforation, or emergency bypass surgery after PCI completion. All procedural complications, including death, coronary perforation,11 emergency bypass surgery, distal embolization, ventricular arrhythmia, and no-reflow were carefully documented and reported. Follow-up was conducted via retrospective review of health records, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) defined as a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, new myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularization were recorded at the follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Inter-group comparisons were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

The composite endpoint of MACE was analyzed as time-to-event data at the follow-up. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate the event-free survival rates. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 23.0, IBM Corp., United States). A 2-tailed P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between July 2015 and August 2024, a total of 130 PCI s were performed in patients with STEMI using ELCA as an adjuvant therapy for thrombus removal. The patients’ mean age was 61.8 ± 11.7 years, with 18 (13.8%) being women and 18 (13.8%) diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. ELCA was employed as the primary device for thrombus dissolution in 66 cases (50.8%) and as a bailout strategy in 64 cases (49.2%). Within the bailout group, manual thrombus aspiration was performed in 47 cases (36.2%), balloon dilation in 6 cases (4.6%), and thrombus debulking using the dotter effect in 11 cases (8.5%).

In the overall cohort, 124 patients (95.4%) presented with culprit lesions with a LTB. Before laser energy application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%). After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively; P < .001 (figure 1).

Figure 1. TIMI grade flow distribution before and after ELCA application. Stacked bar graph showing the distribution of TIMI grade 0-3 flows at 3 different time points: initial angiography, post-ELCA, and final angiographic result after PCI. A marked improvement in coronary flow is observed following ELCA, with a progressive increase in TIMI grade-3 flow from 6.2% to 74.6%. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Technical success was achieved in 128 (98.5%) cases, and procedural success in 124 (95.4%) (table 1). Procedural success was significantly higher when ELCA was used as the initial strategy vs when it was used as the bailout strategy (100% vs 90.6%; P = .013). However, procedural time was significantly longer in the bailout vs the initial strategy group (69.81 vs 48.50 min, respectively) (table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| Variable (n = 130) | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 61.8 ± 11.7 |

| Female | 18 (13.8) |

| Hypertension | 59 (45,4%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 57 (43,8%) |

| Tobacco use | 78 (60%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (13.8) |

| Killip classification | |

| I | 98 (75.4) |

| II | 18 (13.8) |

| III | 3 (2.3) |

| IV | 11 (8.5) |

| Radial access | 118 (90,7%) |

| Femoral access | 12 (9,3%) |

| Lesion localization | |

| LMCA | 3 (2,3%) |

| LAD | 55 (42,3%) |

| LCX | 8 (6,2%) |

| RCA | 64 (49,2 %) |

| Primary device | 66 (50.8) |

| Bailout strategy | 64 (49.2) |

| Large thrombus burden | 124 (95.4) |

| Laser catheter size, Fr | |

| 0.9 | 114 (87.7) |

| 1.4 | 16 (12.3%) |

| Procedural time, min | 60 (43–86) |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 22.2 ±12.2 |

| Laser frequency, Hz | 31 ± 10.4 |

| Laser fluency, mJ/mm2 | 46.5 ± 9.17 |

| Laser delivery time, s | 125.9 ± 83.4 |

| Technical success | 128 (98.5) |

| Procedural success | 124 (95.4) |

|

LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX: left circumflex artery; LMCA: left main coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|

Table 2. Difference in variables between the initial and bailout strategy groups

| Variable | ELCA as the initial strategy (n = 66) | ELCA as the bailout strategy (n = 64) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 8 (12.1%) | 3 (4.7%) | .100 |

| Large thrombus burden | 64 (97%) | 60 (93.8%) | .440 |

| Technical success | 65 (98.5%) | 63 (98.4%) | 1.000 |

| Procedural success | 66 (100%) | 58 (90.6%) | .013 |

| Procedural time, median | 48.50 (38.83–66.61) | 69.81 (55.36–101) | < .001 |

|

ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|||

One case of type IV coronary perforation, according to the modified Ellis classification, occurred in an octogenarian patient with an ecstatic and tortuous right coronary artery. Perforation sealing was achieved with the implantation of a covered stent. One cath lab-related death occurred in a patient with an uncrossable mid-segment of a left anterior descending coronary artery lesion and initial TIMI grade-3 flow. Following balloon dilation and partial advancement of the laser probe, complete vessel occlusion and suspected left main coronary artery dissection resulted in cardiac arrest and cath lab-related death.

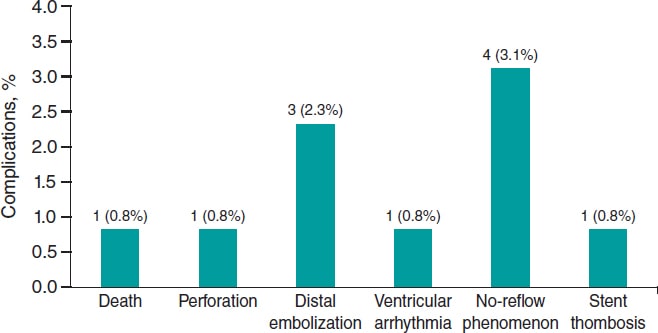

Other procedural complications included distal embolization in 3 (2.3%) cases and slow flow or no-reflow in 4 (3.1%). Among the slow/no-reflow cases, 1 occurred after laser application, and 3 following stent implantation and/or post-dilation. All were successfully managed with optimal medical therapy, achieving final TIMI grade-2 flow. One episode of ventricular arrhythmia occurred during saline washout of the target vessel, requiring electrical cardioversion. Additionally, 1 case of stent thrombosis (0.8%) occurred intraoperatively (figure 2).

Figure 2. ELCA-related procedural complications. Bar chart showing the frequency and percentage of major complications during or immediately after ELCA. The most common was no-reflow (3.1%), followed by distal embolization (2.3%). Other events (death, perforation, ventricular arrhythmia, and stent thrombosis) were rare (0.8% each). ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

Long-term follow-up data were missing for 6 patients (4.6%). At the 2-year follow-up, the event-free rate for combined MACE was 0.80 (95%CI, 0.73–0.88) as determined by the Kaplan–Meier estimator (table 3 and figure 3).

Table 3. List of adverse clinical events

| Patient No. | Event | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Death | 1 |

| 13 | Death | 493 |

| 15 | Death | 148 |

| 23 | Death | 11 |

| 33 | Death | 170 |

| 36 | Death | 4 |

| 43 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 39 |

| 50 | New myocardial infarction | 213 |

| 61 | Death | 16 |

| 77 | Death | 1 |

| 83 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 119 |

| 84 | Death | 4 |

| 92 | Death | 1 |

| 98 | Death | 0 |

| 101 | Death | 37 |

| 110 | Death | 0 |

| 113 | Death | 12 |

| 118 | Death | 253 |

| 121 | Death | 139 |

| 124 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 291 |

| 128 | Death | 10 |

|

TLR, target lesion revascularization. Lost to follow-up: 6 patients (4.6%). |

||

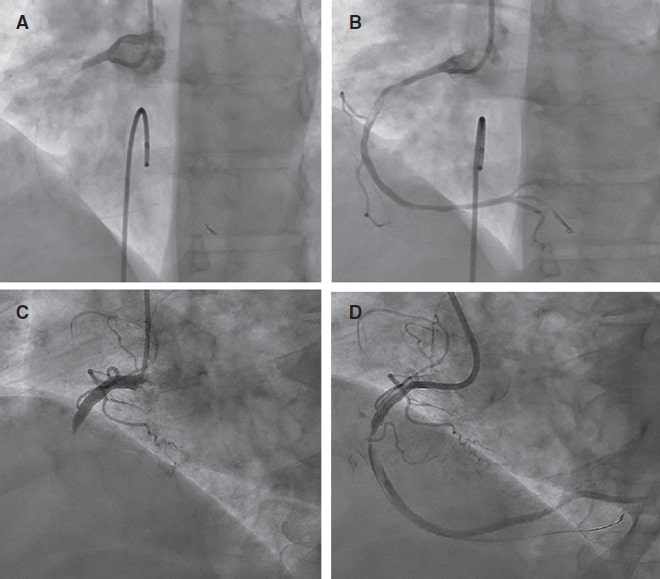

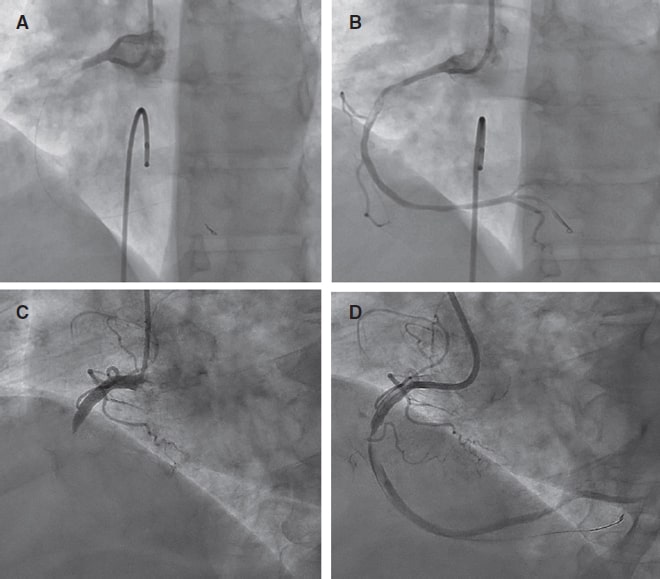

Figure 3. Pre- and post-ELCA findings in 2 typical cases of right coronary artery with large thrombus burden. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this single-center study is that coronary laser angioplasty is a feasible, safe, and effective adjuvant therapy in the context of PCI (videos 1-4 of the supplementary data), demonstrating a low rate of complications and an acceptable long-term rate of MACE.

Data on the use of ELCA in acute myocardial infarction remain limited, with most evidence coming from non-randomized clinical trials. The CARMEL trial,12 the largest multicenter study to date, evaluated the safety, feasibility, and acute outcomes of ELCA in patients with acute myocardial infarction within 24 h of symptom onset requiring urgent PCI. TIMI grade flow significantly improved after laser application, increasing from 1.2 to 2.8, with an overall procedural success rate of 91% and a low distal embolization rate of 2%, even though 65% of cases had a LTB. In our study, 95.4% of the patients had culprit lesions with a LTB, and laser delivery significantly improved the mean TIMI grade flow from 0.6 to 2.29, with a comparable distal embolization rate of 2.3%.

Arai et al.13 retrospectively analyzed 113 consecutive acute coronary syndrome cases undergoing PCI comparing an ELCA group (n = 48) with a thrombus aspiration group (n = 50). They found that ELCA was associated with a significantly shorter door-to-reperfusion time, a better myocardial blush grade, and fewer MACE vs thrombus aspiration. These favorable outcomes are likely attributable to ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi through acoustic shockwave propagation and dissolution mechanisms,12 as well as its capacity to suppress platelet aggregation kinetics (a phenomenon known as the ‘stunned platelet’ effect).14

Reperfusion injury to the coronary microcirculation is a critical concern during PCI in STEMI patients. While manual thrombus aspiration can reduce the rate of no-reflow in patients with a LTB, residual thrombi and decreased coronary flow following thrombectomy have been associated with a higher risk of no-reflow.15 In a study of 812 patients with STEMI and a LTB undergoing PCI, Jeon et al.16 reported that 34.4% experienced failed thrombus aspiration, defined as no thrombus retrieval, remnant thrombus grade ≥ 2, or distal embolization. This failure was associated with an increased risk of impaired myocardial perfusion and microvascular obstruction.

ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi (with a low rate of distal embolization) and mitigate platelet activation, key cofactors in myocardial reperfusion damage,17 can potentially reduce this undesirable effect. Although the direct impact of ELCA on coronary microcirculation in PCI has not been well documented, evidence from smaller studies suggests potential benefits. For example, Ambrosini et al.18 investigated ELCA in 66 patients with acute myocardial infarction and complete thrombotic occlusion of the infarcted related artery, demonstrating excellent acute coronary and myocardial reperfusion outcomes (as assessed by the myocardial blush score and the corrected TIMI frame count), as well as a low rate of long-term left ventricular remodeling (8%). The significant improvement in mean TIMI grade flow observed immediately after ELCA application in our cohort may indirectly suggest a protective effect of this technique on coronary microcirculation. However, the lack of large studies comparing ELCA with conventional STEMI treatment limits the ability to definitively confirm the benefits of coronary laser therapy in this setting. Shibata et al.19 explored the impact of ELCA on myocardial salvage using nuclear scintigraphy in 72 STEMI patients and an onset-to-balloon time < 6 h, comparing ELCA (n = 32) and non-ELCA (n = 40) groups. Their findings indicated a trend towards a higher myocardial salvage index in the ELCA vs the non-ELCA group (57.6% vs 45.6%).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It is a retrospective analysis, which inherently introduces biases related to data collection, interpretation and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Besides, the absence of a comparative group limits the ability to establish the definitive clinical benefit of ELCA and its potential superiority over other strategies in the context of STEMI patients undergoing PCI. Furthermore, while the significant improvement of TIMI grade flow observed after laser application suggests potential benefits for coronary microcirculation, we did not directly assess this effect or thrombus burden reduction since post-ELCA thrombus grading was not systematically recorded. Unfortunately, in our retrospective database, PCI details (segmental analysis of coronary arteries and classification), the use of intravascular imaging modalities, dual antiplatelet therapy regimens (aspirin in addition to a potent P2Y12 inhibitor, or clopidogrel when prasugrel or ticagrelor were contraindicated, was routinely prescribed following current guidelines recommendations) or post-PCI echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance parameters were not systematically collected (unavailable in the health reports we revised) and follow-up data were missing for 4.6% of patients, all of which limited our ability to assess their potential impact on clinical outcomes. Last, our findings represent the experience of a single center, the percentage of women and patients with diabetes is relatively low, and procedures were performed by 5 trained operators, which may limit the external validity of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution in the STEMI scenario, with excellent technical and procedural success rates. Besides, a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes with an acceptable event-free survival rate was observed in the present cohort.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the center Ethics Committee (waiving the need for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the investigation) in full compliance with national legislation and the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Sex was reported as per biological attributes (SAGER guidelines).

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The authors state that no generative artificial intelligence technologies were used in the preparation or revision of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Pernigotti and M. Mohandes were responsible for the conceptualization and study design and contributed equally as co-first authors. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, R. Bejarano, H. Coimbra, F. Fernández, C. Moreno, M. Torres, J. Guarinos were involved in data collection and statistical analysis. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, and J.L. Ferreiro were involved in manuscript drafting and critical revision and were responsible for the supervision and final approval. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal. Each author reviewed all results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. J.L. Ferreiro declared having received speaker’s fees from Eli Lilly Co, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rovi, Terumo and Ferrer; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Co., Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biotronik; and research grants from AstraZeneca, not related to this manuscript.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ELCA is a specialized technique used as adjuvant therapy during PCI for STEMI, particularly in patients with LTB.

- Although former studies have shown that ELCA can improve coronary flow and potentially reduce thrombotic material, data in the setting of acute myocardial infarction remain limited.

- ELCA is mostly used in high-volume centers by experienced operators, and standardized criteria for use in STEMI patients are not consistently reported in the literature.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This is one of the largest retrospective single-center series (130 patients) ever reported on the use of ELCA in STEMI patients with angiographically defined LTB.

- The study shows a high rate of technical and procedural success, significant improvement in TIMI flow, low rate of complication, and acceptable long-term outcomes.

- It provides detailed information on operator training, device selection, and laser settings, contributing to transparency and reproducibility.

- It also identifies current limitations in data reporting (eg, lack of systematic thrombus grading or dual antiplatelet therapy regimen documentation), underscoring the need for standardization in future studies.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 2. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 3. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 4. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

2. Kim MC, Cho JY, Jeong HC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of transient and persistent no reflow phenomena following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:490-498.

3. Sardella G, Mancone M, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves myocardial reperfusion and reduces infarct size:the EXPIRA prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:309-315.

4. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1389-1398.

5. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization:Executive summary. Circulation. 2022;145:e4-e17.

6. Grundfest WS, Litvack F, Forrester JS, et al. Laser ablation of human atherosclerotic plaque without adjacent tissue injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:929-933.

7. Mohandes M, Fernández L, Rojas S, et al. Safety and efficacy of coronary laser ablation as an adjuvant therapy in percutaneous coronary intervention:a single-centre experience. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:241-246.

8. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O'Kane P. Coronary intervention with the excimer laser:review of the technology and outcome data. Interv Cardiol Rev. 2016;11:27-32.

9. Gibson CM, de Lemos JA, Murphy SA, et al. Combination therapy with abciximab reduces angiographically evident thrombus in acute myocardial infarction:a TIMI 14 substudy. Circulation. 2001;103:2550-2554.

10. Topaz O, Das T, Dahm J, et al. Excimer laser revascularisation:current indications, applications and techniques. Lasers Med Sci. 2001;16:72-77.

11. Ellis SG, Ajluni S, Arnold AZ, et al. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-2730.

12. Topaz O, Ebersole D, Das T, et al. Excimer laser angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction (the CARMEL multicenter trial). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:694-701.

13. Arai T, Tsuchiyama T, Inagaki D, et al. Benefits of excimer laser coronary angioplasty over thrombus aspiration therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 0. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;38:13.

14. Topaz O, Minisi AJ, Bernardo NL, et al. Alterations of platelet aggregation kinetics with ultraviolet laser emission:the “stunned platelet“phenomenon. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1087-1093.

15. Ahn SG, Choi HH, Lee JH, et al. The impact of initial and residual thrombus burden on the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26:245-253.

16. Jeon HS, Kim YI, Lee JH, et al. Failed thrombus aspiration and reduced myocardial perfusion in patients with STEMI and large thrombus burden. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:2216-2225.

17. Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA. No-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 2002;105:656-662.

18. Ambrosini V, Cioppa A, Salemme L, et al. Excimer laser in acute myocardial infarction:single centre experience on 66 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:98-102.

19. Shibata N, Takagi K, Morishima I, et al. The impact of the excimer laser on myocardial salvage in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction via nuclear scintigraphy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:161-170.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: To compare the effects of drug-coated balloon (DCB) vs drug-eluting stent (DES) in patients presenting with de novo large vessel coronary artery disease (CAD).

Methods: We conducted a systematic research of randomized controlled trials comparing DCB vs DES in patients with de novo large vessel CAD. Data were pooled by meta-analysis using a random-effects model. The prespecified primary endpoint was target lesion revascularization (TLR).

Results: A total of 7 trials enrolling 2961 patients were included. The use of DCB vs DES was associated with a similar risk of TLR (OR, 1.21; 95%CI, 0.44-3.30; I2 = 48%), all-cause mortality (OR, 1.56; 95%CI, 0.94- 2.57; I2 = 0%), cardiac death (OR, 1.65; 95%CI, 0.90-3.05; I2=0%), myocardial infarction (OR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.58-1.61; I2 = 0%), major adverse cardiovascular adverse (OR, 1.19; 95%CI, 0.74-1.90; I2 = 13.5%) and late lumen loss (standardized mean difference [SMD], −0.35; 95%CI, −0.74 to 0.04; I2 = 81.4%). However, the DCB was associated with a higher risk of target vessel revascularization (OR, 2.47; 95%CI, 1.52-4.03; I2 = 0%) and smaller minimal lumen diameter during late follow-up (SMD, −0.36; 95%CI, −0.56 to −0.15; I2 = 34.5%). Nevertheless, prediction intervals included the value of no difference for both outcomes.

Conclusions: In patients with de novo large vessel CAD the use of DCB vs DES is associated with a similar risk of TLR. However, the DES achieves better late angiographic results.

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon. Drug-eluting stent. Coronary artery disease.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Comparar los efectos del balón farmacoactivo (BFA) frente al stent farmacoactivo (SFA) en pacientes con enfermedad arterial coronaria (EAC) de vaso grande de novo.

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados comparando BFA frente a SFA en pacientes con EAC de vaso grande de novo. Los datos se agruparon mediante un metanálisis de efectos aleatorios. El objetivo primario fue la necesidad de revascularización de la lesión diana (RLD).

Resultados: Se incluyeron 7 ensayos con 2.961 pacientes. El uso de BFA, en comparación con SFA, se asoció con un riesgo similar de RLD (OR = 1,21; IC95%, 0,44-3,30; I2 = 48%), muerte por todas las causas (OR = 1,56; IC95%, 0,94-2,57; I2 = 0%), muerte de causa cardiovascular (OR = 1,65; IC95%, 0,90-3,05; I2 = 0%), infarto de miocardio (OR = 0,97; IC95%, 0,58-1,61; I2 = 0%), acontecimientos adversos cardiacos mayores (OR = 1,19; IC95%, 0,74-1,90; I2 = 13,5%) y pérdida luminal tardía (DME = −0,35; IC95%, −0,74 a 0.04; I2 = 81,4%). Sin embargo, el BFA se asoció a un mayor riesgo de revascularización del vaso diana (OR = 2,47; IC95%, 1,52-4,03; I2 = 0%) y a un menor diámetro luminal mínimo en el seguimiento (DME: −0,36; IC95%, −0,56 a −0,15; I2 = 34,5%), aunque los intervalos de predicción incluyeron el valor nulo para ambos resultados.

Conclusiones: En los pacientes con EAC de vaso grande de novo, el BFA comparado con el SFA se asoció a un riesgo similar de RLD, obteniendo el SFA mejores resultados angiográficos.

Palabras clave: Balón farmacoactivo. Stent farmacoactivo. Enfermedad arterial coronaria.

Abbreviations

CAD: coronary artery disease. DCB: drug-coated balloon. DES: drug-eluting stent. MI: myocardial infarction. MLD: minimum lumen diameter. TLR: target lesion revascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-eluting stents (DES) remain the standard of treatment for patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).1,2 However, DES are associated with a gradually and permanent increased risk of adverse events, particularly due to late stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis, with a 2% incidence rate per year with no plateau observed.1 This risk is even higher when complex and long lesions are treated.3 In recent years, drug-coated balloons (DCB) have emerged as a potential alternative treatment option to DES. Following adequate lesion preparation, unlike traditional stents, DCBs can release an antiproliferative drug into the vessel wall without leaving behind a permanent metal scaffold. Notably, permanent scaffolding can distort and constrain the coronary vessel, thus impairing vasomotion and adaptive remodelling, while also promoting chronic inflammation.4 DCB-PCI is a well-established treatment for in-stent restenosis and small-vessel coronary artery disease (CAD).5,6 However, its role in de novo large vessel CAD remains controversial. In a recent randomized clinical trial (RCT) with patients undergoing de novo CAD revascularization, a strategy of DCB-PCI did not achieve non-inferiority vs DES in terms of device-oriented composite endpoint driven by higher rates of target lesion revascularization (TLR).7 Contrary to prior published research, our findings did not support similar clinical outcomes for DCB vs DES in patients with de novo large vessel CAD.8,9 A recent meta-analysis of 15 studies compared DCB-PCI or hybrid angioplasty vs DES-PCI in patients with vessels > 2.75 mm in diameter showing no significant differences in the clinical endpoints of TLR, cardiac death, and MI.10 However, 14 of the 15 included studies were non-RCT, and the recent previously reported RCT was not included. Nevertheless, individual non-inferiority studies often lack the statistical power needed to definitively compare these technologies, underscoring the need for a systematic appraisal of treatment effects and evidence quality. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of available RCT to provide a comprehensive and quantitative assessment of evidence on the efficacy of DCB vs the current-generation DES in de novo large vessel CAD in terms of adverse events at longest available follow-up.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

We conducted a meta-analysis of RCT according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 guidelines.11 Two reviewers independently identified the relevant studies through an electronic search across the MEDLINE and Embase databases (from inception to October 2024). In addition, we employed backward snowballing (eg, reference review from identified articles and pertinent reviews). No language, publication date or publication status restrictions were imposed. This study is registered with PROSPERO and the search strategy is available in the supplementary data.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently assessed trial eligibility based on titles, abstracts, and full-text reports. Discrepancies in study selection were discussed and resolved with a third investigator. Eligible studies needed to meet the following pre-specified criteria: a) RCT comparing PCI with DCB and PCI with DES; b) study population including patients with de novo large vessel CAD (eg, defined as vessel diameter ≥ 2.5 mm);12 c) availability of clinical outcome data (without restriction as to follow-up time). Exclusion criteria were a) lack of a randomized design; b) studies including patients undergoing treatment for in-stent restenosis; c) studies including patients with de novo small vessel CAD; d) lack of any clinical outcome data.

A reference vessel diameter ≥ 2.5 mm was established as the cut-off value to define large vessel based on a recent proposed standardized definition.12

Data extraction

Three investigators (J. Llau García, S. Huélamo Montoro and J. A. Sorolla Romero) independently assessed studies for possible inclusion, with the senior investigator (J. Sanz-Sánchez) resolving discrepancies. Non-relevant articles were excluded based on title and abstract. The same investigators independently extracted data on study design, measurements, patient characteristics, and outcomes using a standardized data-extraction form. Data extraction conflicts were discussed and resolved with the senior investigator.

Data on authors, year of publication, inclusion and exclusion criteria, sample size, patients’ baseline patients, endpoint definitions, effect estimates, and follow-up time were collected.

Endpoints

The prespecified primary endpoint was TLR. Secondary clinical endpoints were all-cause mortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR) and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). Secondary angiographic endpoints were minimum lumen diameter (MLD) and late lumen loss (LLL). Each endpoint was assessed according to the definitions reported in the original study protocols, as summarized in table 1 of the supplementary data. All the endpoints were assessed at the maximum follow-up available.

Table 1. Main features of included studies

| Study | Year of publication | No. of patients | Type of Device | Reference vessel diameter (mean ± SD) (mm) | Multicenter | Clinical follow up (months) | Angiographic follow-up (months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCB | DES | |||||||

| REC-CAGEFREE I7 | 2024 | 1133 | 1139 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

3.00 ± 0.55 | YES | 24 | NO |

| Nishiyama et al.13 | 2016 | 30 | 30 | Paclitaxel-DCB Everolimus-DES |

2.80 ± 0.63 | NO | 8 | 8 |

| Xue Yu et al.8 | 2022 | 85 | 85 | Paclitaxel-DCB Everolimus-DES |

2.89 ± 0.33 | NO | 12 | 9 |

| REVELATION9 | 2019 | 60 | 60 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus and everolimus DES |

3.24 ± 0.50 | NO | 24 | 9 |

| Gobic et al.15 | 2017 | 38 | 37 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

> 2.50 | NO | 6 | 6 |

| Hao et al.16 | 2021 | 38 | 42 | Paclitaxel-DCB NA |

> 2.50 | NO | 12 | 12 |

| Wang et al.14 | 2022 | 92 | 92 | Paclitaxel-DCB Sirolimus-DES |

3.37 ± 0.52 | NO | 12 | 9 |

|

DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; NA, not available. |

||||||||

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in each study was assessed using the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0).11 Three investigators (J. Llau García, S. Huélamo Montoro and J. A. Sorolla Romero) independently assessed 5 domains of bias in RCT: a) randomization process, b) deviations from intended interventions, c) missing outcome data, d) outcome measurement, and e) selection of reported results (table 2 of the supplementary data).

Table 2. Baseline clinical characteristics of included patients

| Study | Age (years) | Male (%) | Diabetes (%) | Smoking (%) | Hypertension (%) | LVEF (%) | Clinical Presentation (CCS/ACS) (%) | Multivessel (%) | Complex lesion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REC-CAGEFREE I7 | 62 | 69.3 | 27.3 | 45 | 60.1 | 60 | 44.9/55.3 | 4.8 | 0 |

| Nishiyama et al.13 | 69 | 73.3 | 41.6 | 60 | 83.3 | NA | 0/100 | NA | 36 |

| Xue Yu et al.8 | 63.3 | 69.3 | 24.1 | 54 | 63.9 | > 40 | 11.1/88.9 | 84 | 44.1 |

| REVELATION9 | 57 | 87 | 10 | 60 | 31 | 57.6 | 0/100 | 71.6 | N/A |

| Gobic et al.15 | 57.4 | 87 | 10 | 49.5 | 33.4 | 50.2 | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

| Hao et al.16 | 57.5 | 78.5 | 31.5 | 29.5 | 24 | 46 | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

| Wang et al.14 | 49.5 | 93.5 | 81.6 | 81.5 | 71.8 | NA | 0/100 | NA | N/A |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; NA, not available. |

|||||||||

Statistical analysis

Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model, with the estimate of heterogeneity being obtained from the Mantel-Haenszel method. The presence of heterogeneity among studies was evaluated with the Cochran Q chi-square test, with P ≤ .10 being considered of statistical significance, and using the I2 test to evaluate inconsistency. A value of 0% indicates no observed heterogeneity, and values of ≤ 25%, ≤ 50%, > 50% indicate low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. Prediction intervals (95%) in addition to conventional 95%CI around ORs were calculated to assess residual uncertainty. Publication bias and the small study effect were assessed for all outcomes, using funnel plots. The presence of publication bias was investigated using Harbord and Egger tests and visual estimation with funnel plots. We performed a sensitivity analysis by removing one study at a time to confirm that the findings, when compared with DES, were not driven by any single study. To account for different lengths of follow-up across studies, another sensitivity analysis was performed using the Poisson regression model with random intervention effects to calculate inverse-variance weighted averages of study-specific log stratified incidence rate ratios (IRRs). Results were displayed as IRRs, which are exponential ratios of the regression model. Additionally, random-effect meta-regression analyses were performed to assess the impact of the following variables on treatment effect with respect to the primary endpoint: eg, percentage of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS), percentage of patients with diabetes mellitus, mean reference vessel diameter and follow-up duration. The statistical level of significance was 2-tailed P < .05. Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, United States), was used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Search results

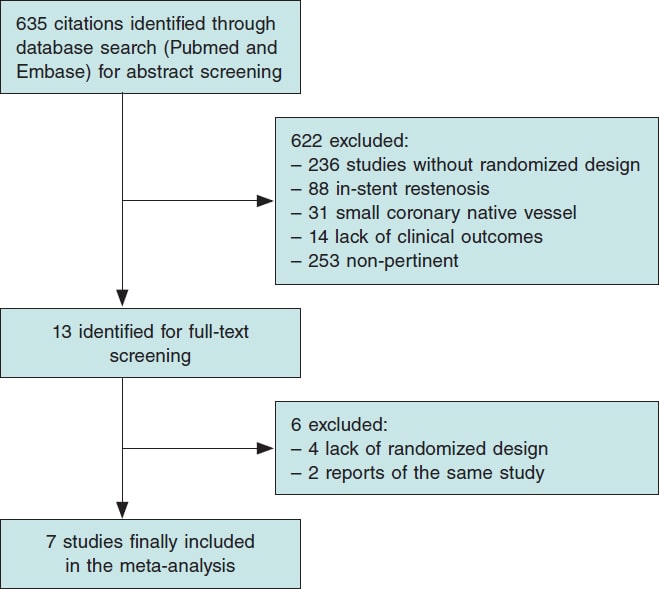

Figure 1 illustrates the PRISMA study search and selection process. A total of 7 RCT were identified and included in this analysis. The main features of included studies are shown in table 1.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of the search for studies included in the meta-analysis according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement.

All studies had a non-inferiority design. A clinical primary endpoint was selected in 1 study,7 and an invasive functional endpoint was selected in another trial,9 while angiographic primary endpoints were prespecified in the remaining studies.8,13-16 The mean clinical and angiographic follow-up were 21.5 months and 8.9 months respectively. A total of 4 studies were conducted in the context of ACS9,14-17 and 1 study in the context of chronic coronary syndrome (CCS).13 Finally, 2 studies enrolled both ACS and CCS patients.7,8 A total of 3 trials enrolled patients treated with second-generation DES (Firebird 2.0 [Microport, China], Xience Xpedition [Abbott Vascular, United States], Orsiro [Biotronik, Germany]),7,9,13 and 2 studies enrolled patients treated with third-generation DES (Biomine [Meril Life Sciences, India], Cordimax [Rientech, China]).14,15 One trial enrolled patients treated with second and third-generation DES (Xience Xpedition [Abbott Vascular, United States], Resolute Integrity, [Medtronic, United States], Firehawk, [MicroPort, China]).8 All studies included patients who underwent paclitaxel-DCB-PCI ([Pantera Lux, Biotronik, Germany],9,14 [SeQuent Please, B Braun, Germany],7,8,13,15 [Bingo DCB, Yinyi Biotech,China]),16 and none with sirolimus-DCB-PCI.

Baseline characteristics

A total of 2961 patients were included, 1476 of whom received DCB and 1485, DES for de novo large vessel CAD. The patients main baseline characteristics are shown in table 2.

Publication bias and asymmetry

Funnel-plot distributions of the pre-specified outcomes indicate absence of publication bias for all the outcomes (figures 1-8 of the supplementary data).

Risk of bias assessment

Table 2 of the supplementary data illustrates the results of the risk of bias assessment with the RoB 2.0 tool. One trial was considered at low overall risk of bias,7 5 raised some concerns8,9,13,14,16 and 1 presented a high overall risk of bias.15

Outcomes

Clinical outcomes

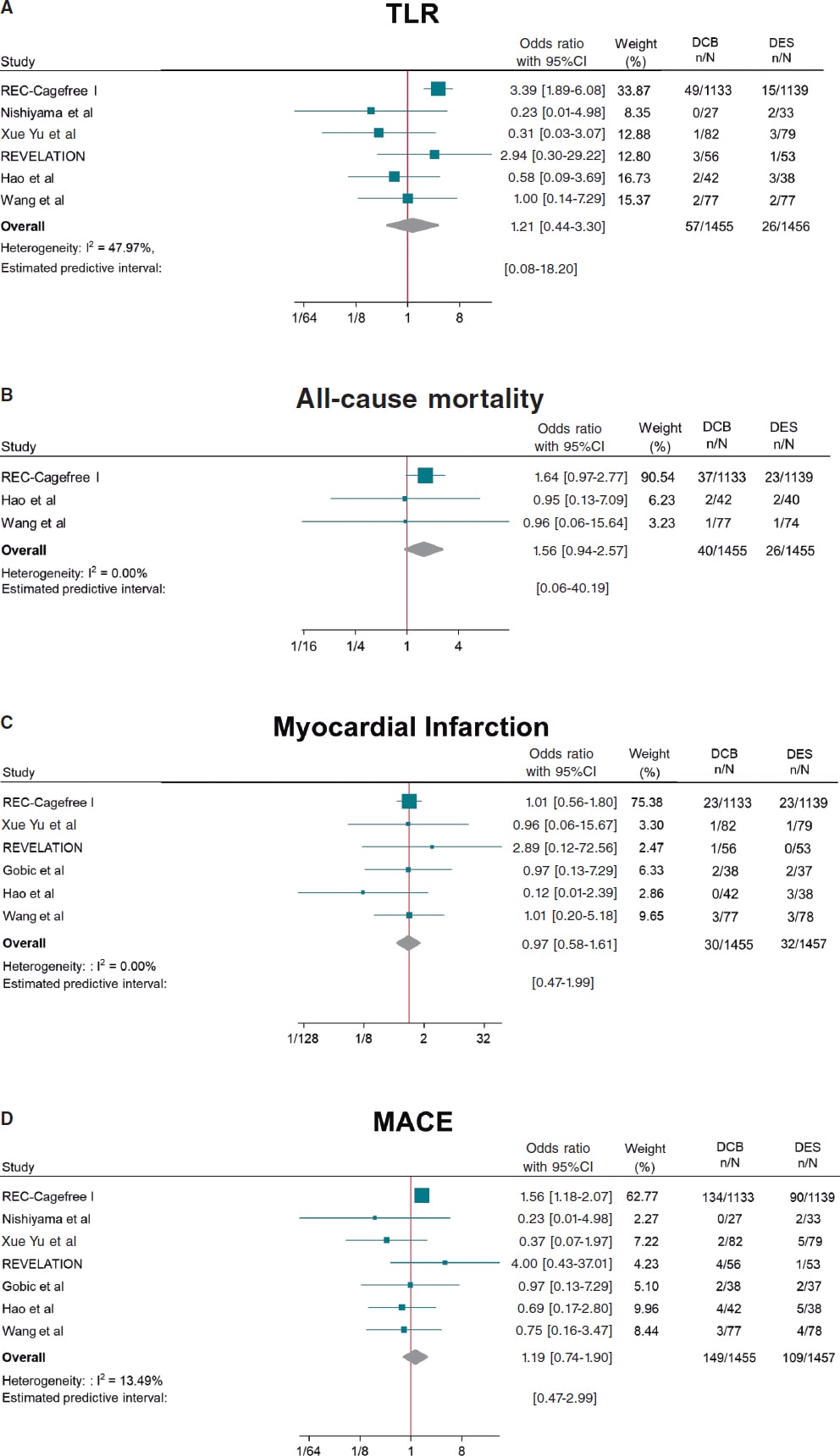

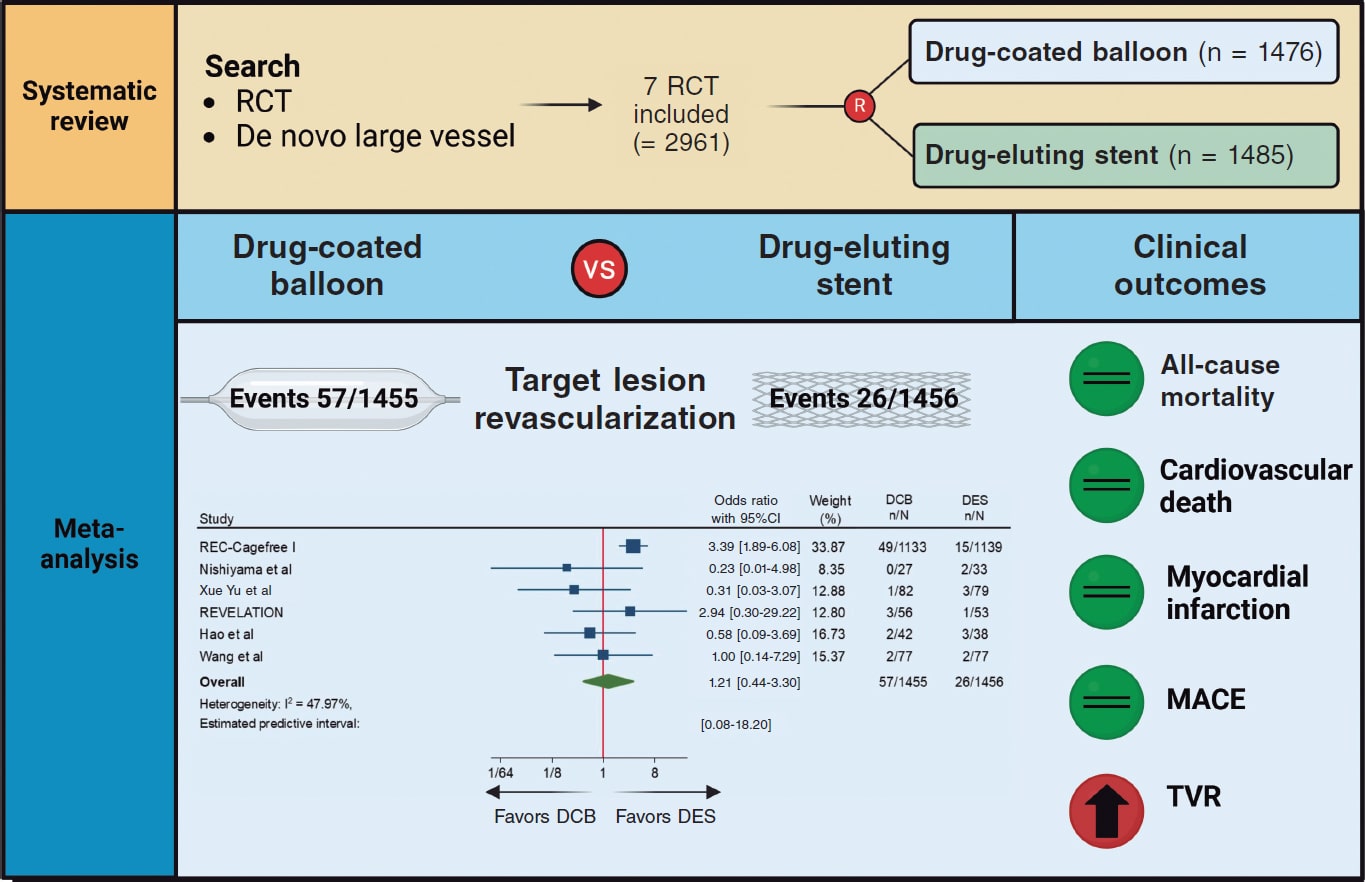

DCB use compared with DES was associated with a similar risk of TLR (OR, 1.21; 95%CI, 0.44-3.30; I2 = 48%), all-cause mortality (OR, 1.56; 95%CI, 0.94- 2.57; I2 = 0%), cardiac death (OR, 1.65; 95%CI, 0.90-3.05; I2 = 0%), MI (OR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.58-1.61; I2 = 0%) and MACE (OR, 1.19; 95%CI, 0.74-1.90; I2 = 13.5%). However, DCB was associated with a higher risk of TVR (OR, 2.47; 95%CI, 1.52- 4.03; I2 = 0%) (figure 2, figure 3 and figures 9-10 of the supplementary data).

Figure 2. Forest plot reporting trial-specific and summary ORs with 95%CIs for the endpoint of A) target lesion revascularization; B) all-cause mortality; C) myocardial infarction; D) MACE. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stents; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; OR, odds ratio. References: REC-Cagefree I.,7 Nishiyama et al.,13 Xue Yu et al.,8 REVELATION,9 Hao et al.,16 Wang et al.,14 and Gobic et al.15

Figure 3. Central Illustration. DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; RCT, randomized clinical trial; TVR, target vessel revascularization. References: REC-Cagefree I.,7 Nishiyama et al.,13 Xue Yu et al.,8 REVELATION,9 Hao et al.,16 and Wang et al.14

Angiographic outcomes

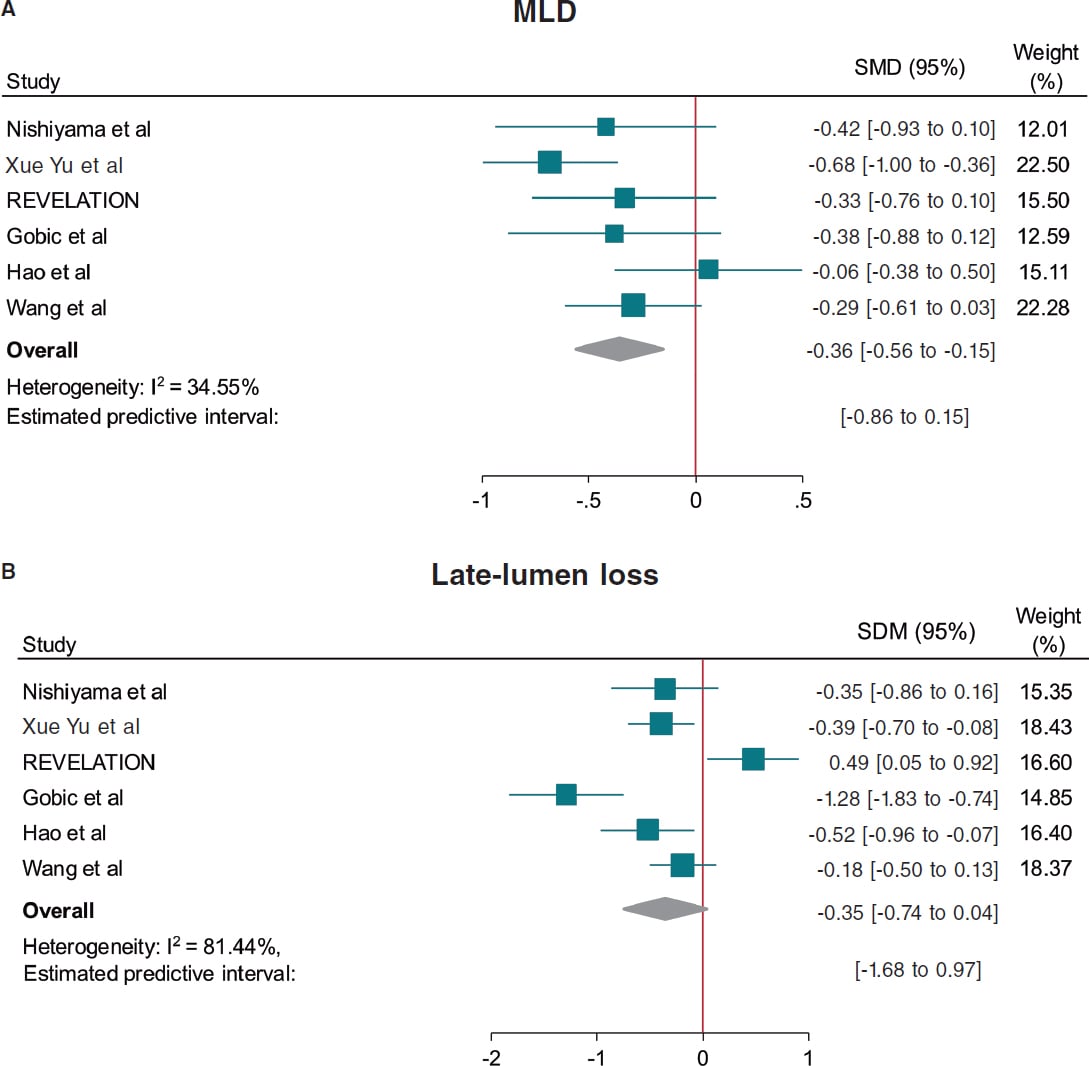

Compared with DES, DCB use yielded significant smaller MLD (SMD, −0.36; 95%CI, −0.56 to −0.15; I2 = 34.5%) and similar risk of LLL (SMD, −0.35; 95%CI, −0.74 to 0.04; I2 = 81.4%) at follow-up (figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot reporting trial-specific and summary ORs with 95%CIs for the endpoint of A: minimum lumen diameter, and B: late-lumen loss. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stents; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MLD, minimum lumen diameter; SMD, standardized mean difference; OR, odds ratio. References: Nishiyama et al.,13 Xue Yu et al.,8 REVELATION,9 Gobic et al.,15 Hao et al.,16 and Wang et al.14.

Prediction intervals were consistent with CI for all the outcomes except for TVR and MLD, which included the value of no difference.

Sensitivity analysis

A leave-one-out pooled analysis by iteratively removing one study at a time was performed for all endpoints. Treatment effects were consistent with the main analysis for TLR, all-cause mortality, cardiac death, MI and MLD. The risk of TVR was no longer significantly higher among patients undergoing DCB when removing the CAGEFREE I trial,7 and the risk of LLL was significantly lower among patients undergoing DCB-PCI when removing the REVELATION trial.9 However, an increased risk of MACE was observed among patients undergoing DCB-PCI when removing the study by Xue Yu et al.18 (tables 3-10 of the supplementary data). A sensitivity analysis using estimated IRRs was performed to account for varying follow-up lengths, confirming that our main analysis findings remained unchanged (table 11 of the supplementary data).

Random effect meta-regression analysis found no significant impact of the proportion of patients presenting with ACS (P = .882), diabetes mellitus (P = .641), mean reference vessel diameter (P = .985) and follow-up duration (P = .951) on treatment effect with respect to the primary endpoint.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive and updated quantitative analysis of available evidence on the comparison of DCB vs DES in de novo large vessel CAD, including data from 2961 patients enrolled in 7 RCT. The main findings of the study are:

a) The use of DCB was associated with a similar risk of clinical events vs DES except for TVR. However, data for this outcome was only available in 3 of the 7 included studies and the increased risk in patients undergoing DCB-PCI was not significant when the CAGEFREE I trial was removed. In addition, prediction intervals were not consistent with the CI. Therefore, the results of this outcome should be interpreted with caution.

b) The effect of DCB on the risk of TLR was not affected by the proportion of patients presenting with ACS or diabetes, as well as the mean reference vessel diameter or follow-up duration as assessed by meta-regression analysis.

c) DCB was associated with lower MLD at angiographic follow-up, but with similar LLL vs DES.

DES are the standard of treatment for patients undergoing PCI. However, complications such as stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis still occur with rates estimated at 0.7-1% and 5-10% at the 10-year follow-up respectively.19,20 Therefore, in recent years there has been a growing concern for developing strategies to reduce stent-related adverse events. In this context, DCBs have emerged as a potential treatment alternative based on a “leaving nothing behind” strategy. Nevertheless, data of patients presenting with de novo large CAD is scarce and conflicting. The CAGEFREE I is the only available clinically powered RCT that included 2272 patients undergoing de novo non-complex CAD revascularization across 40 centers in China. A strategy of DCB-PCI did not achieve non-inferiority vs DES in terms of device-oriented composite endpoint driven by higher rates of TLR in the DCB-PCI group (3.1% vs 1.2%, P = .002). On the other hand, in single-center RCT conducted by Nishiyama et al. with 60 patients with CCS undergoing elective PCI a trend toward lower rates of TLR in the DCB-PCI group (0% vs 6.1%, P = .193) was shown at the 8-mont follow-up.13 Similarly, in a RCT including 170 patients undergoing PCI for de novo large CAD lower rates of TLR at the 12-month follow-up were found in patients undergoing DCB-PCI (1.6% vs 3.4%, P = .306).14 In our analysis when pooling data from all available RCT, the risk of TLR was similar among patients undergoing DCB-PCI or DES-PCI. Notably, since this result was obtained with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 ≈ 50%), it should be interpreted with caution regarding its general applicability. These findings remained unvaried at the leave-one-out analysis. In addition, prediction intervals were consistent with CI around ORs showing lack of residual uncertainty. Previous studies have shown that in-stent restenosis after DES is not a benign phenomenon, presenting as an ACS in about 70% of the cases, with 5-10% of these resulting in MI.21 We could speculate that the lack of permanent scaffold with DCB vs DES may predispose to a less aggressive pattern of restenosis and not increase the risk of thrombotic vessel closure beyond 3 months when vessel healing after DCB-PCI has occurred.22

Notably, 5 of the 7 studies included in this meta-analysis enrolled patients presenting with ACS. A total of 34% of the patients included in the CAGEFREE study presented with ACS, with 16% being STEMI cases.7 Four other studies only included STEMI patients.7,9,14-16 Although the performance of DCB in the STEMI scenario is unknown, its use in clinical practice is increasing.23 Culprit lesion plaques in STEMI patients are usually soft and adequate plaque modification can be easily achieved through DCB-PCI (< 30% residual stenosis and low grade of dissection).23 Moreover, the ruptured lipid rich plaque can potentially be an ideal reservoir for effective paclitaxel uptake.24 On the other hand, DCBs carry specific risks for STEMI patients, such as acute recoil and culprit lesion closure, because they don’t provide vessel scaffolding.

In our study, the proportion of patients presenting with ACS had no impact on treatment effects on the meta-regression analysis. Nevertheless, further RCT with adequate sample size are needed to obtain more solid evidence in this field. Of note, complex lesions (eg, severe calcification and bifurcations with planned two-stent technique) were excluded from the studies that included patients presenting with CCS.7,8 Therefore, our findings might not be generalized to this population.

The better angiographic surrogate outcomes with DES-PCI vs DCB-PCI found in our meta-analysis after pooling data from 6 studies can be explained by the absence of a metal scaffold to expand the vessel lumen and the acute recoil following balloon angioplasty. This justifies the lower MLD achieved after DCB-PCI vs DES-PCI. While our analysis did not show significant differences regarding LLL during follow-up, the value of LLL was lower among patients undergoing DCB-PCI when excluding the REVELATION trial.9,17 This study showed extremely low LLL in both DCB and DES groups vs other available evidence from RCT.15,16 The presence of positive vessel remodeling with a late lumen enlargement after the use of DCB evaluated by intracoronary imaging modalities has been evidenced in multiple studies, and seems to be associated with small vessel disease, fibrous and layered plaques and a post-PCI medial dissection arc > 90°.25,26,27 However, evidence of this phenomenon in patients with large vessel CAD is less known.22 It should, therefore, be noted that all studies in this meta-analysis used paclitaxel-DCB. While the evidence comparing sirolimus and paclitaxel-DCB is scarce, 2 recent RCT have shown better angiographic results with the lipophilic component. In the first one, with 121 patients with the novo small vessel CAD, sirolimus-DCB failed to achieve non-inferiority for net-lumen gain at 6 months.28 In the second study, with 70 patients, the 2 devices showed similar results of LLL at 6 months, although patients treated with paclitaxel-DCB had more frequent late luminal enlargement.29 Due to the small sample size and although there is not enough evidence to evaluate differences across clinical endpoints, we cannot assume that there is a class effect across all DCBs. There are larger ongoing RCT to evaluate the outcomes of sirolimus DCB vs DES in large vessels that will provide evidence in this field.30,31

Limitations

The results of our investigation should be interpreted in light of some limitations. First, this is a study-level meta-analysis providing average treatment effects. The lack of patient-level data from the included studies prevents us from assessing the impact of baseline clinical, angiographic and procedural characteristics on treatment effects. Second, minor differences in definition were present for some endpoints (eg, MACE), limiting the reliability of effect estimates. Third, one study which accounted for approximately 75% of all patients included did not included angiographic follow-up,7 thus limiting the evaluation of DCB and DES on angiographic outcomes. Fourth, the clinical follow-up varied from 6 to 24 months. Ideally, outcomes such as TLR should be compared at uniform follow-up across studies (eg, at 1 year), which was not consistently possible in the current analysis. Nonetheless, these differences in follow-up duration were accounted with the IRRs, as detailed in the Methods section. However, longer follow-ups are needed to establish the safety and efficacy profile of DCB vs DES throughout time. Fifth, the definition of large vessel is inconsistent across trials, which might be a source of bias. Finally, the limited number of studies and patients, and the small event rate for some endpoints, such as all-cause mortality may reduce the power for detecting significant differences across groups.

CONCLUSIONS

This meta-analysis provides the most updated quantitative evidence on the use of DCB vs DES for the treatment of de novo large vessel CAD in both CCS and ACS. DCB-PCI is associated with similar TLR and LLL at mid-term follow-up representing an appealing treatment option for patients with large vessel CAD.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethics approval was deemed unnecesary for this meta-analysis as all data were collected and synthesized from previous studies. Additionally, no informed consent was required as there were no patients involved in our work. The meta-analysis of RCT was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2009 guidelines. We confirm that sex/gender biases have been taken into consideration.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J. Llau García, S. Huelamo Montoro and J.A. Sorolla Romero participated in literature research and study selection. J.A. Sorolla Romero, L. Novelli and J. Sanz Sánchez contributed to the conception, design, drafting and revision of the article. P. Rubio, J.L. Díez Gil, L. Martínez-Dolz, I.J. Amat Santos, B. Cortese, F. Alfonso, and H.M. Garcia-Garcia contributed to the critical revision of the intellectual content of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

F. Alfonso is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The authors declared no relevant relationships with the contents of this paper.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- DCB are a well-established treatment for patients with small-vessel CAD.

- Available published evidence of patients with de novo large vessel CAD is scarce and shows conflicting results.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- In this meta-analysis including data from 2961 patients enrolled in 7 RCT, DCB showed similar risk of clinical events at follow-up vs DES in the treatment of de novo large vessel CAD.

- The use of DCB might be considered as an alternative option to DES in patients undergoing PCI for non-complex de novo large vessel CAD.

REFERENCES

1. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

2. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization:Executive Summary:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e4-e17.

3. Kong MG, Han JK, Kang JH, et al. Clinical outcomes of long stenting in the drug-eluting stent era:patient-level pooled analysis from the GRAND-DES registry. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2021;16:1318-1325.

4. Kawai T, Watanabe T, Yamada T, et al. Coronary vasomotion after treatment with drug-coated balloons or drug-eluting stents:a prospective, open-label, single-centre randomised trial. EuroIntervention. 2022;18:e140?e148.

5. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease:Third Report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402.

6. Sanz Sánchez J, Chiarito M, Cortese B, et al. Drug-Coated balloons vs drug-eluting stents for the treatment of small coronary artery disease:A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2021;98:66-75.

7. Gao C, He X, Ouyang F, et al. Drug-coated balloon angioplasty with rescue stenting versus intended stenting for the treatment of patients with de novo coronary artery lesions (REC-CAGEFREE I):an open-label, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Lond Engl. 2024;404:1040-1050.

8. Yu X, Wang X, Ji F, et al. A Non-inferiority, Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Versus New-Generation Drug-Eluting Stents on Angiographic Outcomes for Coronary De Novo Lesions. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2022;36:655-664.

9. Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G, et al. Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction:The REVELATION Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1691-1699.

10. Gobbi C, Giangiacomi F, Merinopoulos I, et al. Drug coated balloon angioplasty for de novo coronary lesions in large vessels:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:4921.

11. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535.

12. Sanz-Sánchez J, Chiarito M, Gill GS, et al. Small Vessel Coronary Artery Disease:Rationale for Standardized Definition and Critical Appraisal of the Literature. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1:100403.

13. Nishiyama N, Komatsu T, Kuroyanagi T, et al. Clinical value of drug-coated balloon angioplasty for de novo lesions in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:113-118.

14. Wang Z, Yin Y, Li J, et al. New Ultrasound-Controlled Paclitaxel Releasing Balloon vs. Asymmetric Drug-Eluting Stent in Primary ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction-A Prospective Randomized Trial. Circ J Off J Jpn Circ Soc. 2022;86:642-650.

15. Gobic´D, Tomulic´V, Lulic´D, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:A Feasibility Study. Am J Med Sci. 2017;354:553-560.

16. Hao X, Huang D, Wang Z, Zhang J, Liu H, Lu Y. Study on the safety and effectiveness of drug-coated balloons in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;16:178.

17. Niehe SR, Vos NS, Van Der Schaaf RJ, et al. Two-Year Clinical Outcomes of the REVELATION Study:Sustained Safety and Feasibility of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E39-E42.

18. Xue W, Ma J, Yu X, et al. Analysis of the incidence and influencing factors associated with binary restenosis of target lesions after drug-coated balloon angioplasty for patients with in-stent restenosis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022;22:493.

19. Coughlan JJ, Maeng M, Räber L, et al. Ten-year patterns of stent thrombosis after percutaneous coronary intervention with new- versus early-generation drug-eluting stents:insights from the DECADE cooperation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2022;75:894-902.

20. Madhavan MV, Redfors B, Ali ZA, Prasad M, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Revascularization for Stable Ischemic Heart Disease:An Individual Patient-Level Pooled Analysis of 19 Randomized Coronary Stent Trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv.2020;13:e008565.

21. Buchanan KD, Torguson R, Rogers T, et al. In-Stent Restenosis of Drug-Eluting Stents Compared With a Matched Group of Patients With De Novo Coronary Artery Stenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2018;121:1512-1518.

22. Antonio Sorolla Romero J, Calderón AT, Tschischke JPV, Luis Díez Gil J, Garcia-Garcia HM, Sánchez JS. Coronary plaque modification and impact on the microcirculation territory after drug-coated balloon angioplasty:the PLAMI study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2025;78:481-482.

23. Merinopoulos I, Gunawardena T, Corballis N, et al. Assessment of Paclitaxel Drug-Coated Balloon Only Angioplasty in STEMI. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:771-779.

24. Maranhão RC, Tavares ER, Padoveze AF, Valduga CJ, Rodrigues DG, Pereira MD. Paclitaxel associated with cholesterol-rich nanoemulsions promotes atherosclerosis regression in the rabbit. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:959-966.

25. Kleber FX, Schulz A, Waliszewski M, et al. Local paclitaxel induces late lumen enlargement in coronary arteries after balloon angioplasty. Clin Res Cardiol Off J Ger Card Soc. 2015;104:217-225.

26. Alfonso F, Rivero F. Late lumen enlargement after drug-coated balloon therapy:turning foes into friends. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol. 2024;20:523-525.

27. Yamamoto T, Sawada T, Uzu K, Takaya T, Kawai H, Yasaka Y. Possible mechanism of late lumen enlargement after treatment for de novo coronary lesions with drug-coated balloon. Int J Cardiol. 2020;321:30-37.

28. Ninomiya K, Serruys PW, Colombo A, et al. A Prospective Randomized Trial Comparing Sirolimus-Coated Balloon With Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon in De Novo Small Vessels. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:2884-2896.

29. Ahmad WAW, Nuruddin AA, Abdul KMASK, et al. Treatment of Coronary De Novo Lesions by a Sirolimus- or Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:770-779.

30. Spaulding C, Krackhardt F, Bogaerts K, et al. Comparing a strategy of sirolimus-eluting balloon treatment to drug-eluting stent implantation in de novo coronary lesions in all-comers:Design and rationale of the SELUTION DeNovo Trial. Am Heart J. 2023;258:77-84.

31. Greco A, Sciahbasi A, Abizaid A, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary artery disease:Rationale and design of the TRANSFORM II randomized clinical trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv Off J Soc Card Angiogr Interv. 2022;100:544-552.

ABSTRACT

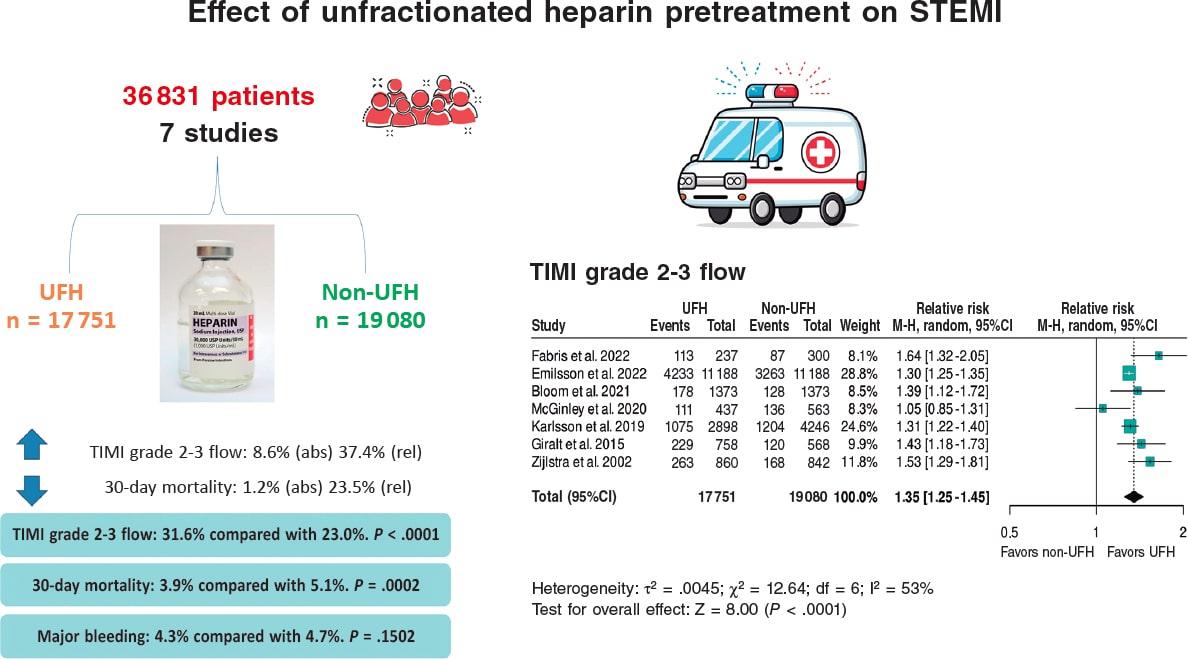

Introduction and objectives: The early administration of unfractionated heparin (UFH) for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is still a matter of discussion, and clinical practice guidelines leave the timing of administration prior to angioplasty at the physician’s discretion.

Methods: We conducted a systematic search across PubMed/Cochrane databases for studies comparing pre-treatment with UFH with a comparative untreated group (non-UFH) of patients with STEMI undergoing primary angioplasty and including TIMI flow and 30-day mortality targets from June 2024 through September 2024. We conducted a randomized meta-analysis and assessed the risk of publication bias to detect asymmetry in the included studies.

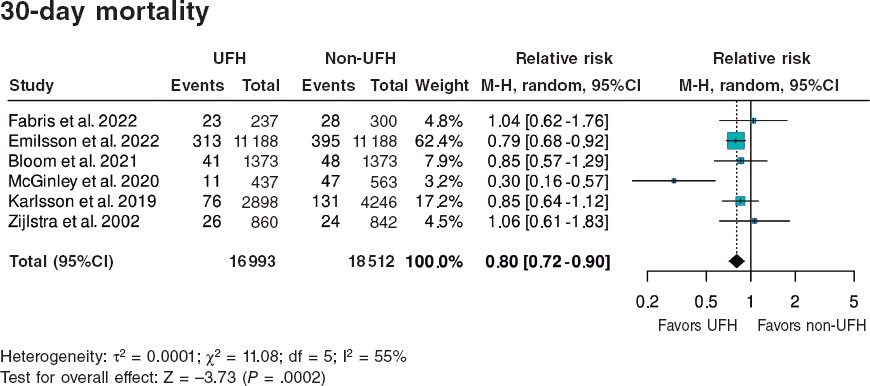

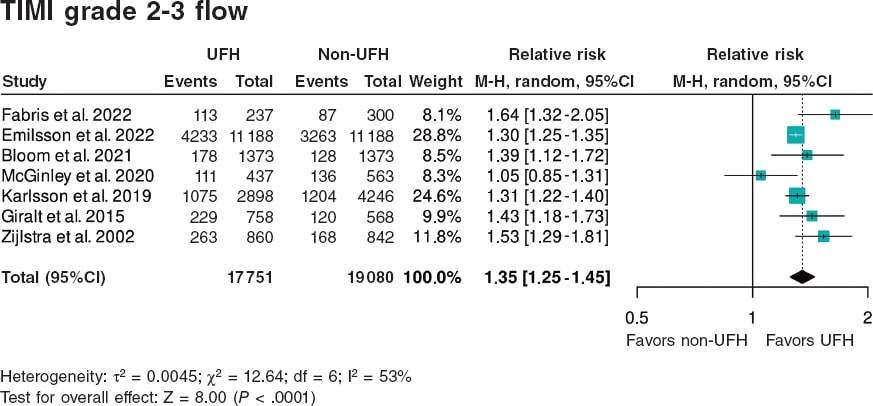

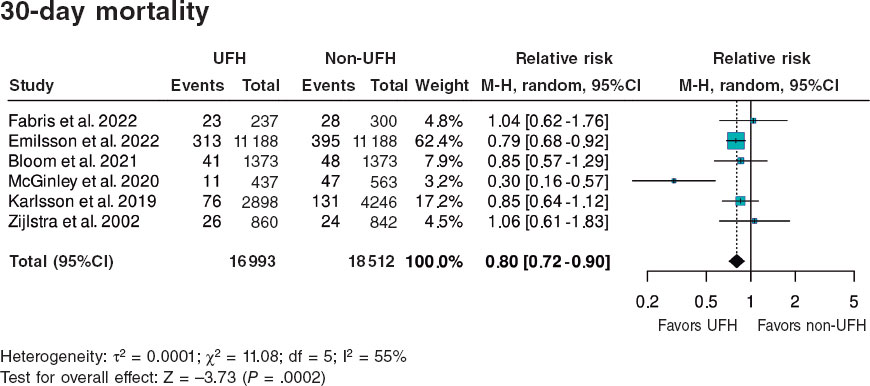

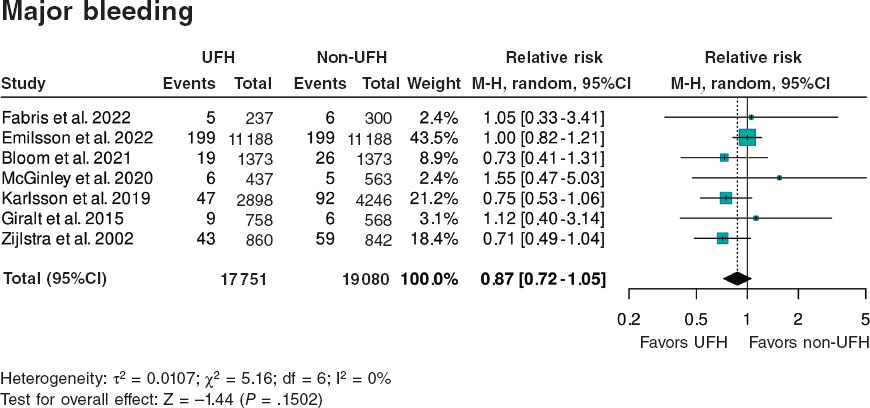

Results: We included a total of 7 studies published from 2002 through 2022 (6 retrospective trials and 1 substudy of a randomized trial) for a total of 36 831 patients: 17 751 in the UFH pre-treatment group and 19 080 in the non-UFH control group. A total of 6202 patients (31.6%) on UFH had TIMI grade-II/III flow vs 5106 (23.0%) on non-NFH while 490 (3.9%) on UFH died within 30 days vs 673 (5.1%) on non-NFH. Meta-analysis demonstrated a higher probability of TIMI grade-II/III flow (HR, 1.35; 95%CI, 1.25-1.45; P < .0001) and a lower 30-day mortality rate in patients on UFH pretreatment (HR, 0.80; 95%CI, 0.72-0.90; P = .0002), with no differences being reported in bleeding complications (HR, 0.87; 95%CI, 0.72-1.05; P = .150).

Conclusions: Meta-analysis of studies shows that pretreatment with UFH in STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty is associated with a higher probability of TIMI grade-II/III flow and a lower risk of early mortality.

Meta-analysis registered in PROSPERO (CRD420250655362).

Keywords: Meta-analysis. Unfractionated heparin. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Prognosis. Pre-treatment. Acute myocardial infarction.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La administración temprana de heparina no fraccionada (HNF) en el infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST) está sujeta a controversia, por lo que las guías de práctica clínica dejan a criterio médico el momento de su administración antes de la angioplastia.

Métodos: Entre junio y septiembre de 2024 se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en PubMed y Cochrane de estudios que comparasen el pretratamiento con HNF con un grupo control no tratado (no-HNF) en pacientes con IAMCEST tratados con angioplastia primaria e incluyesen los objetivos de flujo TIMI y la mortalidad a 30 días. Se llevó a cabo un metanálisis aleatorizado, en el que se evaluó el riesgo de sesgo de publicación para detectar asimetría en los estudios incluidos.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 7 estudios publicados entre 2002 y 2022, de los cuales 6 eran retrospectivos y 1 subestudio de un ensayo aleatorizado, con 36.831 pacientes: 17.751 el grupo de pretratamiento con HNF y 19.080 el grupo control no-HNF. Un total de 6.202 (31,6%) con HNF tuvieron flujo TIMI II/III, frente a 5.106 (23,0%) de los no-HNF, y 490 (3,9%) con HNF fallecieron en 30 días, frente a 673 (5,1%) de los no-HNF. El metanálisis demostró mayor probabilidad de flujo TIMI II/III (HR = 1,35; IC95%, 1,25-1,45; p < 0,0001) y menor mortalidad en los pacientes que recibieron pretratamiento con HNF (HR = 0,80; IC95%, 0,72-0,90; p = 0,0002), sin diferencias en complicaciones hemorrágicas (HR = 0,87; IC95%, 0,72-1,05; p = 0,150).

Conclusiones: El metanálisis muestra que el pretratamiento con HNF en pacientes con IAMCEST y angioplastia primaria se asocia a una mayor probabilidad de flujo TIMI II/III y un menor riesgo de mortalidad precoz.

Metanálisis registrado en PROSPERO (CRD420250655362).

Palabras clave: Metanálisis. Heparina no fraccionada. Infarto con elevación del segmento ST. Pronóstico. Pretratamiento. Infarto agudo de miocardio.

Abbreviations

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. UFH: unfractionated heparin.

INTRODUCTION

The implementation of STEMI Code protocols, involving emergency and cardiology services, has led to improved care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and lower morbidity and mortality rates.1 Correct diagnosis of STEMI, pretreatment with antiplatelet agents, and the organization of rapid and direct transfer to a center with an PCI-capable center for primary angioplasty are quality standards in the management of STEMI.1

Parenteral anticoagulation is generally recommended in acute coronary syndrome at the time of diagnosis.1 In STEMI, the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) during primary angioplasty is recommended to prevent coronary thrombosis and device-related complications, but its use should be discontinued after the procedure.2

The precise role of UFH pretreatment at the time of first medical contact for patients diagnosed with STEMI remains to be fully defined. The 2023 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology1 allow attending physicians to decide when to administer UFH during treatment, as there is no solid evidence supporting its early use. This flexibility is based on the absence of conclusive data on the benefits of UFH at this stage of treatment.1,3

The most recent data published on the implementation of STEMI Code protocols and care networks in Spain reveal heterogeneity in response times and transport among the different autonomous communities (AC).4,5 This heterogeneity is also observed in the administration of anticoagulant and antiplatelet pretreatment across the 17 AC. A review of STEMI Code protocols as of December 2024 shows that in 6 of the 17 (35.3%) AC, pretreatment with UFH is recommended, representing coverage for 43.1% of the Spanish population (table 1 of the supplementary data). All AC, except for one, include dual antiplatelet therapy as pretreatment at the first medical contact in their protocols. Differences in the standardization of UFH use in STEMI Code protocols reflect the lack of evidence and concrete recommendations on this topic.

Table 1. Demographic data of populations and characteristics of the selected studies

| Study | Design | Country | n | n (%) | Age, years | Concomitant antiplatelets, drug, and dosis | Male sex | Door-to-balloon time | UFH dosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | ||||

| Fabris et al. (2022)10 | Retrospective | Italy | 537 | 237 (44.1%) | 300 (55.9%) | 66.0 ± 12.5 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | ASA: 237, 250 mg (100%) Ticagrelor: 237, 280 mg (100%) | ASA: 300, 250 mg (100%) PCI-capable center: UFH + ticagrelor or prasugrel or clopidogrel | 176 (74.3%) | 226 (75.3%) | 77 | 74 | 70 IU/kg | 70 IU/kg |

| Emilsson et al. (2022)6 | Retrospective | Sweden | 22 376 | 11 188 (50.0%) | 11 188 (50.0%) | 67.0 ± 12.0 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | ASA: 226, NR (2%) Clopidogrel: 221, NR (22%) Ticagrelor: 4642, NR (41%), Prasugrel: 574, NR (5.1%) | ASA: 170, NR (1.5%) Clopidogrel: 28, NR (0.3%) Ticagrelor: 4486, N (40%) Prasugrel: 608, NR (5.4%) | 7877 (70%) | 7992 (71%) | 276 ± 244 | 290 ± 270 | NR | NR |

| Bloom et al. (2021)7 | Retrospective | Australia | 2746 | 1373 (50.0%) | 1373 (50.0%) | 63.0 ± 12.4 | 63.2 ± 12.7 | ASA: 1327, NR (96.6%) Ticagrelor: 944, NR (68.8%) | ASA: 1326, NR (96.6%) Ticagrelor: 975, NR (70.9%) | 1099 (80.0%) | 1081 (78.7%) | 48 ± 23 | 64 ± 47 | 4000 + 1000 IU/h in ambulance | 4000 IU |

| McGinley et al. (2020)8 | Retrospective | Scotland | 1000 | 437 (43.7%) | 563 (56.3%) | 63.7 ± NR | 63.7 ± NR | ASA: 437, NR (100%) Clopidogrel: 437, NR (100%) | ASA: NR Clopidogrel: NR | 304 (69.6%) | 390 (69.3%) | NR | NR | 5000 IU | 5000 IU |

| Karlsson et al. (2019)11 | Subanálisis de ensayo clínico aleatorizado | Sweden | 7144 | 2898 (40.6%) | 4246 (59.4%) | 66.0 ± 11.5 | 66.0 ± 11.6 | ASA: 2817, NR (97.2%), Clopidogrel: 1662, NR (57.4%), Ticagrelor: 731, NR (25.2%) Prasugrel: 243, NR (8.4%) | ASA: 3636, NR (85.6%) Clopidogrel: 2489, NR (58.6%) Ticagrelor: 578, NR (13.6%) Prasugrel: 338, NR (8%) | 2169 (74.8%) | 3177 (74.8%) | 185 (125–320) | 181 (118–327) | NR | NR |

| Giralt et al. (2015)9 | Retrospective | Spain | 1326 | 758 (57.2%) | 568 (42.8%) | 61.3 ± 12.8 | 63.4 ± 12.8 | ASA: 744, NR (98.2%) Clopidogrel: 742, NR (97.9%) | ASA: 531, NR (93.5%) Clopidogrel: 503, NR (88.6%) | 618 (81.5%) | 434 (76.4%) | 107 (86–133) | 105 (83–140) | 5000 IU | 5000 IU |

| Zijlstra et al. (2002)12 | Retrospective | The Netherlands | 1702 | 860 (50.5%) | 842 (49.5%) | 59.0 ± 11.0 | 61.0 ± 11.0 | ASA: 860, NR (100%) | ASA: 842, NR (100%) | 696 (80.9%) | 665 (79.0%) | 81 ± 43 | 26 ± 39 | NR | NR |

|

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; IU, international units; NR, not reported; UFH, unfractionated heparin. |

|||||||||||||||

The aim of this study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing studies on UFH pretreatment in the context of primary angioplasty as a reperfusion treatment for STEMI in terms of TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) grade 2-3 flow at the start of the procedure and early 30-day in-hospital mortality.

The meta-analysis follows PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and quality (table 2 of the supplementary data).

Table 2. Events from the studies

| Study | n | n (%) | Open artery: TIMI grade 2-3 flow | Major bleeding | 30-day mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | ||

| Fabris et al. (2022)10 | 537 | 237 (44.1%) | 300 (55.9%) | 113 (47.7%) | 87 (29.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | 6 (2.0%) | 23 (9.7%) | 28 (9.3%) |

| Emilsson et al. (2022)6 | 22 376 | 11 188 (50.0%) | 11 188 (50.0%) | 4233 (37.8%) | 3263 (29.2%) | 199 (17.8%) | 199 (17.8%) | 313 (2.8%) | 395 (3.5%) |

| Bloom et al. (2021)7 | 2746 | 1373 (50.0%) | 1373 (50.0%) | 178 (13.0%) | 128 (9.3%) | 19 (1.4%) | 26 (1.9%) | 41 (3.0%) | 48 (3.5%) |

| McGinley et al. (2020)8 | 1000 | 437 (43.7%) | 563 (56.3%) | 111 (25.4%) | 136 (24.2%) | 6 (1.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 11 (2.5%) | 47 (8.3%) |

| Karlsson et al. (2019)11 | 7144 | 2898 (40.6%) | 4246 (59.4%) | 1075 (37.1%) | 1204 (28.3%) | 47 (1.6%) | 92 (2.2%) | 76 (2.6%) | 131 (3.1%) |

| Giralt et al. (2015)9 | 1326 | 758 (57.2%) | 568 (42.8%) | 229 (30.2%) | 120 (21.1%) | 9 (1.2%) | 6 (1.1%) | NR | NR |

| Zijlstra et al. (2002)12 | 1702 | 860 (50.5%) | 842 (49.5%) | 263 (30.6%) | 168 (20.0%) | 43 (5.0%) | 59 (7.0%) | 26 (3.0%) | 24 (2.9%) |

| Total | 36 831 | 17 751 (48.0%) | 19 080 (51.9%) | 6202 (31.6%) | 5106 (23.0%) | 328 (4.3%) | 393 (4.7%) | 490 (3.9%) | 673 (5.1%) |

|

NR, not reported; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; UFH, unfractionated heparin. |

|||||||||

METHODS

Literature search

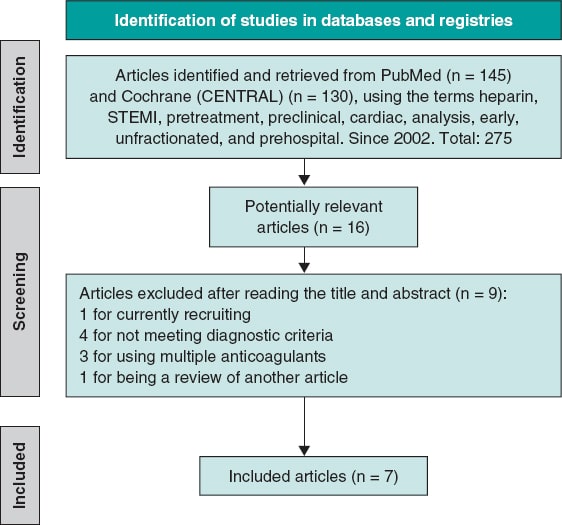

We conducted a systematic search of scientific literature across Medline-PubMed and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) from May through September 2024. We accessed several observational studies and clinical trials comparing UFH pretreatment in the ambulance vs no pretreatment in patients diagnosed with STEMI treated with primary angioplasty. A lower date limit was set to 2002, and no language restrictions were applied. Studies were selected if they included information on initial TIMI grade flow, 30-day early mortality, and major bleeding complications. In the article by Emilsson et al.6 data from the propensity score cohort, which provides better adjustment, were used, and the same population was used in the study by Bloom et al.7. The references of the selected studies were analyzed to obtain additional articles via cross-referencing. Both the search and article selection methodology are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the literature search. STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.