ABSTRACT

Despite the 2017 update to European medical device regulation and its entry into force in 2021, many doubts persist about its real-world application in medical device (MD) research in Spain. The development of MDs requires collaboration among numerous stakeholders, including researchers, ethics committees, notified bodies, the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices, manufacturers, and other involved parties—all of whom have had to adapt to the new regulatory framework. This has required a significant effort and consumption of resources to understand and apply the different clinical practice guidelines to unify protocols in MD research and ensure the safety and efficacy profile of these products. Although challenges remain, the adoption of this legislation has fostered collaboration among stakeholders, enabling progress and a better understanding of the new obstacles it presents. The aim of this review is to define, in a practical way, the content of this regulation and expose the perspectives of the different actors involved in the development of MD.

Keywords: Medical device. Health research. Research regulation.

RESUMEN

Tras la actualización de la regulación europea sobre dispositivos médicos de 2017 y su posterior entrada en vigor en 2021, persisten multitud de dudas en cuanto a su implementación práctica en la investigación en productos sanitarios (PS) en España. Desarrollar PS implica la colaboración de multitud de actores, incluyendo investigadores, comités de ética, organismos notificados, Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios, industria de dispositivos y diversos colaboradores, que se han visto obligados a adaptarse a esta nueva regulación. Este hecho ha requerido un esfuerzo y un consumo de recursos significativo para comprender y aplicar las distintas directrices que persiguen unificar los protocolos en PS y asegurar la seguridad y la eficacia de estos productos. Desde su implementación, la colaboración entre las distintas partes ha permitido progresar y entender las nuevas dificultades que representa esta normativa. El objetivo de este documento es definir de manera práctica el contenido de dicha regulación y exponer las perspectivas de los diferentes actores implicados en el desarrollo de PS.

Palabras clave: Producto sanitario. Investigación sanitaria. Regulación en investigación.

Abbreviations

AEMPS: Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices. CE: European Certificate. EU-MDR: European Union Medical Device Regulation. MD: medical device. MDR: Medical Device Regulation. MREC: Medicinal Research Ethics Committee. NB: notified body.

INTRODUCTION

Since the update of the European Medical Devices Regulation (MDR) in 2017 with Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on Medical Devices (EU-MDR)1 and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices (EU-IVDR),2 and the promulgation in Spain of Royal Decree 192/2023 of March 21,3 the need has arisen to adapt to the new regulations promoted by Europe. The objective of these regulations is to establish a new robust, transparent, predictable, and sustainable regulatory framework for MD, which guarantees the highest levels of safety and health protection for patients and users, while promoting innovation and the interests of small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) that carry out their activities in this sector, thereby obtaining the European Conformity (CE) marking. This regulation harmonizes the rules applicable to the placing on the market and putting into service in the European Union of MD and their accessories, thus allowing them to benefit from the principle of free movement of goods and ensuring a high level of protection, so that products in circulation do not pose any risks to the health of patients, users or third parties, and achieve the performance assigned by the manufacturer when used under the intended conditions.3

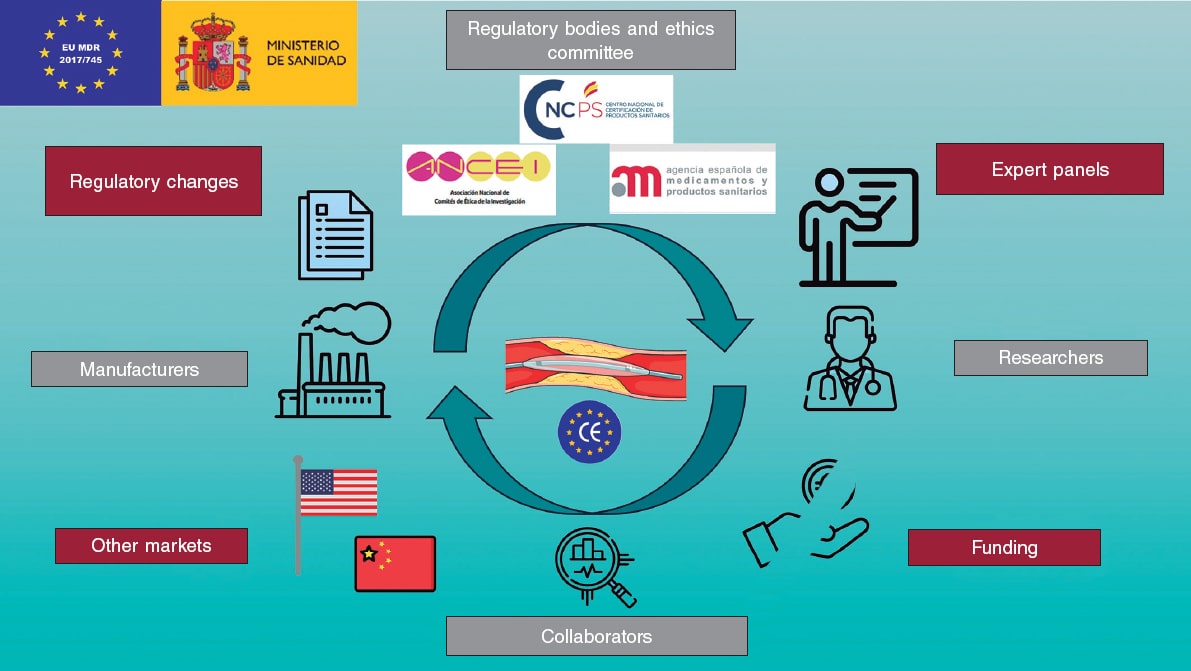

The complexity of this new regulation has led to the publication of previous documents from an academic perspective, at both European and national levels, to help understand the new regulations.4,5 Nonetheless, these regulatory changes invariably generate tensions among the different actors involved in the development of MD. These include regulatory bodies, such as the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS), drugs research ethics committees (DREC), and notified bodies (NB); the industry, comprising various large companies, SME, and start-ups; collaborators, including companies responsible for health data registration and analysis, or different types of consultancies; researchers; and finally, patients and their associations. Since all these actors pursue the same common goal, collaboration among each of the parties involved in understanding this regulation, contributing their unique perspective and the difficulties they individually present, can lead to improved MD development and facilitate an increasingly complex process (figure 1).

Figure 1. Central illustration. Stakeholders in the development of medical devices, challenges and threats they face. Icons created by Freepik, Smalllikeart, Rizal2109, and Iconpro on www.flaticon.com. Image obtained from Servier Medical Art, under CC BY 4.0 license (https://smart.servier.com).

The objective of this document is to summarize the content of the EU-MDR to facilitate its understanding and present the perspective of each of the parties involved in the MD development process. In January 2025, with the above-mentioned objective, Fundación Epic organized and promoted a face-to-face meeting where these perspectives were presented through various presentations. The following summarizes the presentations, questions, and discussions from the meeting.

Definitions and nomenclature in medical devices

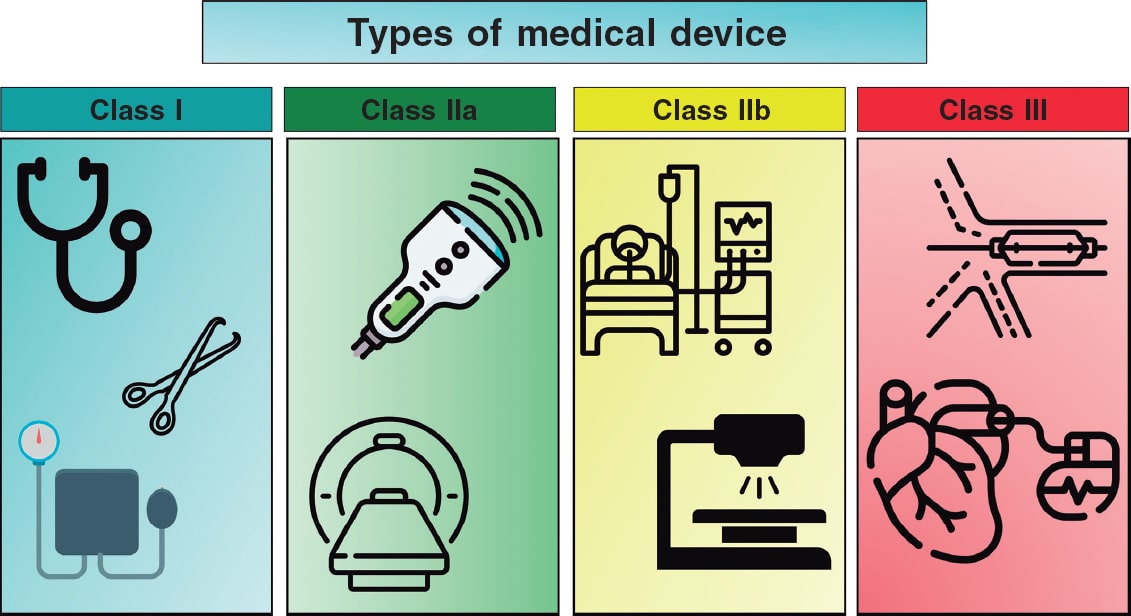

Although the use of MD is ubiquitous in the medical field, health care personnel are rarely familiar with the nomenclature and definitions that apply to them. Table 1 briefly illustrates the main terms we will be using in this document. Although, in Article 2, the EU-MDR clearly defines the terminology to be used,1 it is convenient to expand on some definitions to fully understand the nuances of MD development. The risk classification of MD takes into consideration the intended purpose of the device and its inherent risks (EU-MDR, Annex VIII,1 and European Commission guidance6). Devices can be categorized as low (class I), medium (class IIa), and high risk (class IIb and class III), and in the case of in vitro diagnostic medical devices, as classes A, B, C, and D, with class A being the lowest risk and class D the highest risk. Although class I devices that are considered simpler can be self-certified by the manufacturer, other class I devices (that are sterile or have a measuring function) and class IIa, IIb, and III devices must undergo a conformity assessment requiring the participation of a NB. Implantable devices and those in direct contact with the circulatory system are all defined as high risk (class III); 40% of these are for cardiovascular application.7 Figura 2 illustrates some examples of the different classes of devices, which are defined as:

Table 1. Definitions of the main terms used in the document

| Término | Definición |

|---|---|

| Medical device | Any instrument, apparatus, equipment, software, implant, reagent, material, or other article intended by the manufacturer to be used in humans, alone or in combination, for one or more of the following specific medical purposes:

|

In addition, it does not achieve its principal intended action inside or on the surface of the human body by pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic means, although such means may contribute to its function. The following shall also be considered medical devices:

|

|

| In vitro diagnostic device | Any medical device that is a reagent, reagent product, calibrator, control material, kit, instrument, apparatus, piece of equipment, software, or system, used alone or in combination, intended by the manufacturer to be used in vitro for the examination of specimens derived from the human body, including blood and tissue donations, solely or principally to provide information on one or more of the following:

|

| Legacy medical device | Any medical device that complied with the legislation prior to the EU-MDR but has not yet been certified under the current legislation. |

| Regulation (EU) 2017/745 in MDR | European legislation on medical devices. |

| Regulation (EU) 2017/746 in IVDR | European legislation on in vitro devices. |

| CE marking | Marking by which a manufacturer indicates that a product conforms to the applicable requirements set out in this legislation and other applicable Union harmonization legislation providing for its affixing (MDR, Article 2.43). |

|

CE, European Conformity marking; EU, European Union; IVDR, in vitro devices regulation; MDR, medical devices regulation. |

|

Figure 2. Classification of various types of medical devices and examples thereof. Icons created by Kiranshastry, Vectorslab, Iconsmeet, Freepik, and N.style on www.flaticon.com.

- – Class I: low-risk products for the patient, generally non-invasive. Examples: stethoscope, electrocardiogram electrodes, reusable surgical instruments, and non-automated sphygmomanometer. Specific classes are Is (sterile), Im (measuring function), and Ir (reusable).

- – Class IIa: moderate-risk products used invasively, but on a temporary basis. Examples: hypodermic needle, electronic stethoscope, electronic blood pressure measuring equipment, electrocardiograph, diagnostic ultrasound machine (such as echocardiography), and magnetic resonance imaging system.

- – Class IIb: higher-risk products that may have prolonged contact with the body or that control vital functions. Examples: infusion pumps, monitoring and alarm devices in intensive care, ventilators, external defibrillators, and diagnostic devices that emit ionizing radiation.

- – Class III: high-risk products, generally implantable and with a significant impact on patient health. Examples: cardiovascular catheters and guidewires, bare metal and drug-eluting stents, prosthetic heart valves and valve repair devices, implantable devices for other structural heart procedures, electrophysiology electrodes and ablation catheters and equipment, implantable cardiovascular electronic devices including pacemakers, implantable automatic defibrillators, and cardiac resynchronization therapy, extracorporeal circulation systems, extracorporeal membrane oxygenators, intra-aortic balloon pumps, and left ventricular assist devices.

PERSPECTIVE OF REGULATORY AGENCIES, NOTIFIED BODIES, AND ETHICS COMMITTEES

To obtain CE marking, an MD must comply with a series of requirements imposed by the different regulatory bodies. These requirements depend on the intended purpose and risk classification of each type of MD. Furthermore, with respect to clinical investigations of medical devices under Regulation 2017/745, table 2 outlines key requirements. The roles and responsibilities of the involved bodies are discussed below.

Table 2. Requirements for conducting clinical investigations with medical devices

| Type of investigation | DREC | AEMPS | Management approval | Insurance | Article |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without CE marking | Yes | Authorization | Yes | Yes | Article 62 (objective: assess CE conformity) |

| With CE marking, different intended purpose | Yes | Authorization | Yes | Yes | Article 74, Section 2 |

| With CE marking, same intended purpose and following instructions for use | |||||

| With additional invasive or burdensome procedures | Yes | Notify | Yes | No | Article 74, Section 1 |

| Article 73 (notify NEOPS/EUDAMED) | |||||

| Sin procedimientos adicionales invasivos ni gravosos | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

|

AEMPS, Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices; CE, European Conformity marking; DREC, Drug Research Ethics Committee. |

|||||

Drug research ethics committee

Obtaining approval from the DREC is the first step that any investigation must overcome for its realization. A distinction must be made between the research ethics committee, which oversees biomedical research projects under Law 14/2007, and the DREC,8 accredited to issue opinions on clinical trials with drugs and MD under Royal Decree 1090/2015.9 The criteria that DREC must meet for the evaluation of clinical investigations with MD have not yet been published. Performance studies of in vitro diagnostic MD will not require evaluation by a DREC; in some cases, this evaluation can be conducted by a research ethics committee in accordance with the EU-IVDR.10 The function of every DREC is to safeguard the rights, safety, and well-being of participant subjects. To this end, the DREC must include health care professionals, members outside the health care profession (including law graduates), patient representatives, and an expert in the General Data Protection Regulation; additionally, the DREC may request expert advice if it lacks the necessary knowledge or experience to evaluate a study (as may be the case with the investigation of surgical procedures, diagnostic techniques, or advanced therapies). Consulting experts in MD is a very common thing, given their variety and different purpose and nature which, at times, make it difficult to elucidate whether a device is an MD (for example, in the case of software applications). The DREC evaluation will require:

- Prior clinical evidence demonstrating that the MD performs its intended function and ensures safety.

- Adequate methodology to respond to the objectives, clearly defining in the protocol the justification, study population, sample size, variables that should be included, recruitment and randomization process, etc.

- From an ethical point of view, it must guarantee full compliance with ethical principles, especially in relation to obtaining informed consent, and comply with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki11 and the international standard ISO 14155:2021 (“Clinical investigation of medical devices for human subjects. Good clinical practice”).12

According to Royal Decree 192/2023 on MD research, authorization from the management of the center or centers where the research will be conducted is required, along with a favorable opinion from the local DREC or, in the case of a multicenter study, a single binding opinion issued by a DREC within the national territory.3 In any case, each center will have to manage internal administrative aspects for the study to be conducted. The deadline for each DREC to issue its opinion is not specified in Royal Decree 192/2023, so it largely depends on the characteristics of each committee.

Given the complexity of the new regulation, representatives from various DREC, together with Asociación Nacional de Comités de Ética de Investigación (ANCEI) and the AEMPS, agreed in 2023 to establish a working group to harmonize the evaluation of MD investigations. It is expected that, in the months ahead, this collaboration will result in a joint memorandum of instructions to facilitate the certification process and harmonize the documentation required by both entities; for example, the memorandum will define the deadlines available for issuing an opinion.

Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices

In Spain, the AEMPS is the competent authority responsible for the application and supervision of EU Regulation 2017/745. The AEMPS has prepared a series of documents and manuals with the aim of clarifying the process, requirements, and documentation that must be submitted for its evaluation of MD studies.13 Table 2 illustrates the requirements for conducting clinical investigations with MD.

The AEMPS continues to work on reviewing new documents. Those on in vitro diagnostic MD and the above-mentioned DREC-AEMPS joint document are still pending. Furthermore, the Medical Device Coordination Group—the European group involved in the regulation of MD—publishes guidelines whose compliance is voluntary, but still reflect the current situation and consensus on these issues from a European perspective.14 Regarding performance studies of in vitro diagnostic MD, their requirements, in many cases, will not require authorization or notification by the AEMPS, and could be evaluated by a research ethics committee. However, performance studies of in vitro diagnostic MD that could be burdensome to health or pose a risk to patients are regulated by Article 58 of their own legislation (EU-IVDR 2017/74610) and their requirements are similar to those of table 2. Risk procedures include surgically invasive sample collection solely for the purpose of the study, additional invasive procedures, and other risks to participant subjects, such as interventional procedures or diagnostic tests that may influence clinical decisions.

Moreover, there are combined studies with both drugs and MD, to which both regulations will apply. A case that needs clarification is that of integrated products. Studies with these products would not be combined studies, as they do not involve drugs or MD. An integrated product is a MD or a drug, and only the corresponding legislation would apply to it. The criterion that should be follow is fundamentally its main mechanism of action: whether it is that of a drug or a MD. An example of an integrated product that is a MD would be a drug-eluting stent action whose primary mechanism of action is mechanical dilation of the coronary artery, with the incorporated medicinal substance exerting a secondary antiproliferative effect. A pre-filled insulin syringe would be an integrated product too. However, in this case the main mechanism of action is the drug per se (insulin). The “part of the product” that would be a MD separately would only act as a drug delivery system.

The procedure for authorizing clinical investigations with MD by the AEMPS, as well as other information related to MD regulation, are included in the instructions published on its website, which are currently being reviewed.13 The procedure is, in sum: 15 days for document validation, 20 days for the sponsor to respond to possible AEMPS requirements, and 10 days for the AEMPS to evaluate the responses. Once the application has been admitted for processing, the clinical investigation evaluation period begins, which will last 45 days, although the AEMPS may have an additional 20 calendar days to consult experts. The AEMPS may raise objections to the sponsor and request additional information, in which case the deadlines will be suspended, and the sponsor will have 10 working days (extendable by another 5 days) to respond. Of note, the AEMPS will require the DREC approval, which is why it is recommended to send the documentation with the DREC opinion already issued or in an advanced stage of processing; otherwise, the AEMPS will automatically deny the investigation if the deadline has been met. Once the clinical investigation has been completed, the sponsor will notify the AEMPS within 15 calendar days. If a temporary halt or early termination occurs, the sponsor must notify it within 15 calendar days and provide a justification; if it is for safety reasons, they must inform the AEMPS within 24 hours. For the final report of the investigation, the sponsor will have 1 year since the investigation was completed or 3 months if was terminated early. Of note, Article 69 of the EU-MDR specifies the conditions under which investigations must have insurance or financial guarantee for the research subjects.1 Table 2 shows that investigations involving MD without CE marking, or with CE marking but used off-label (for purposes other than those approved at the time of CE marking), must include subject insurance.

A fundamental pillar for the development of the EU-MDR is the EUDAMED database (European Database on Medical Devices), whose objective is to improve public transparency, facilitate device traceability and market surveillance, and strengthen coordination among Member States. This database, intended to be accessible to state organizations, was not available at the time of publication of this document; therefore, the AEMPS continues to use its general registry to process authorizations for clinical investigations with MD and performance studies with in vitro diagnostic MD. For cases that only require notification (table 2), the NEOPS database (notificación de investigaciones clínicas con productos sanitarios) is being used until EUDAMED is definitively implemented.

Notified body

A NB is an organization designated by a European Union Member State (or other countries within the framework of specific agreements) to assess the conformity of certain products before they are out in the market. The only NB created in Spain is Centro Nacional de Certificación de Productos Sanitarios, which has the competence and capacity to designate and monitor MD. The NB requires standardized technical documentation fully complying with the necessary requirements for previous evidence levels and conformity with general safety and performance regulations. Its official website contains the necessary documents for carrying out each procedure and guiding documents (table 1 of the supplementary data).

Since beginning operations on September 15, 2022, the Spanish NB has received requests from 142 applicant companies and has signed 100 agreements. These agreements are defined as a formal contract between the NB and the manufacturer that allows the NB to perform an evaluation of the MD, defining the scope of the evaluation, the obligations of the manufacturer and the NB, the conditions for maintaining, renewing, or suspending the CE, and aspects related to confidentiality and responsibility. Among these agreements, a total of 40 certificates have been issued, including 300 products (29 quality certificates and 11 technical documentation certificates [class IIb implantable or class III MD]). The usual time between MD registration and agreement signing is 1 to 4 weeks. However, this process may extend beyond 2 months because of several difficulties encountered by the NB, such as:

- – Significant workload: the NB currently has 275 products under review, 25% of which are implantable, requiring a more comprehensive and demanding evaluation.

- – Non-adapted technical documentation structure: despite efforts to generate standardized documentation, multiple corrections to the documentation are usually required, thus delaying the certification process.

- – Expert consultation: certain MD require evaluation by a panel of experts. In fact, Article 56 states that consultation with a panel of experts is mandatory for class IIb or III MD.1

- – Identifying experts in certain MD can be challenging, as some MD are designed for highly specific applications; this may further delay the evaluation.

Of note, there is a deadline for the certification of MD with a previous certification. MD that have failed to obtain CE marking under the new legislation by this deadline may no longer be marketed and could be subject to withdrawal. This deadline has already been postponed due to the risk of product shortages in the market, the limitation of NB, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with current dates being December 31, 2027, for class III and IIb implantable MD and December 31, 2028, for non-implantable class IIb, IIa, Is (sterile), and Ir (measuring function) MD.15 However, although these dates may seem distant, the Centro Nacional de Certificación de Productos Sanitarios invites manufacturers to carry out the certification procedure without delay.

A significant limitation of NB is the absence of prior dialogue with manufacturers. This can hinder the development of adequately designed clinical studies which, on occasion, would be considered inadequate by the NB after being completed. Working together on the design of clinical trials could be beneficial for both parties, reducing the time needed for MD approval and facilitating the conduct of the study and its review.

The required documentation is complex and raises many doubts and questions. Therefore, several links of interest to official documents and websites of the corresponding organizations have been provided, where these complex and specific aspects are explained in detail (table 1 of the supplementary data).

MANUFACTURER AND INDUSTRY OUTLOOK

Threats and challenges

The technological industry has required a series of profound adaptations to the new regulations, involving a multitude of threats and difficulties. According to the European association COCIR (European Trade Association representing the medical imaging, radiotherapy, health ICT and electromedical industries), the new legislation has markedly prolonged certification times, with a 157% increase in document preparation time and a 263% increase to final approval. Certification costs have risen by 262%, and regulatory staffing requirements have grown by 5%–9%, resulting in losses of personnel and budget in research, development, and innovation.16 A survey submitted to various manufacturing companies in the MD industry by MedTech Europe found that the main challenges identified are insufficient clinical evidence generated while devices are on the market, the absence of a clear definition of what constitutes sufficient clinical information, and the difficulty in agreeing with the NB on an appropriate post-market surveillance plan.17 In an open-ended question evaluating the main obstacles, respondents cited associated costs, extended timelines, divergent requirements among Member States, and the demanding requirements of clinical investigations. Therefore, Real World Data and Real World Evidence are relevant sources of clinical information. The former refers to information obtained outside traditional clinical trials; it can be drawn from health records, patient registries, insurance databases, or observational or cohort studies. The latter involves the analysis or interpretation of Real World Data, which is limited to raw data. Therefore, Real World Evidence allows generating evidence on safety, efficacy, health outcomes, and use of MD in the routine clinical practice. However, the survey shows that NB would accept this type of evidence mostly as an additional source, 23% of NB would not accept it at all, and only 12% would accept it as the sole source of clinical evidence. Among the types of sources, clinical registries would be the most accepted, with the rest of the formats (surveys, administrative records, etc.) being much lower in terms of acceptance.

A particularly sensitive threat to MD development affects MD intended for vulnerable patients or with orphan diseases. MD whose scope of use is in pediatric patients or pregnant women run the risk of being unable to obtain sufficient clinical evidence to meet the necessary requirements for obtaining the CE marking. Similarly, if robust clinical evidence is required for a MD intended for orphan diseases, which are characterized by very low prevalence and incidence, there is a risk that sponsoring companies will be unable to cover development costs—already challenging given the unique nature of these rare conditions.

Competitiveness compared with other markets

Many of these limitations pose a serious threat to SME and start-ups, which usually have a less solid and consolidated financial structure than large companies. The increase in costs and the need for additional personnel discourage the development of MD in Europe. Therefore, start-ups such as Aortyx have chosen to direct the development of their medical devices toward more favorable regulatory systems, such as that of the United States, whose primary bureaucratic advantages rest on 2 key points. The first is the greater speed of procedures by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has a maximum of 90 days to give a response, while European NB take a mean 50 days to simply accept the case. Secondly, the possibility of maintaining a dialogue with the FDA to establish what type of clinical trials would be most appropriate to obtain its approval, in non-binding meetings through the Q-sub program, is of special interest. In Europe, the design of the study is left to the manufacturer, without the possibility of receiving feedback from the regulatory body before completing it, thus risking an unfavorable assessment. Consequently, they would be forced to repeat the study, with the substantial investment that this implies. Even so, according to Article 57 of the EU-MDR manufacturers should voluntarily consult a panel of experts on the clinical development strategy and research proposals that should be followed.1 Additionally, in the United States, programs such as Breakthrough Device Designation can further accelerate the process by prioritizing novel MD considered disruptive to treat serious—often cardiovascular—diseases.18

Although the previous reasons may be considered sufficient for certain MD manufacturing companies to prioritize the United States, financial profitability is also of great significance. The US market offers, from this perspective, a series of advantages over the European Union. The first is the higher morbidity of the American population. The second, the significantly higher price at which most MD are marketed. Overall, this means that not only from a bureaucratic point of view, but also from a purely financial one, market access is more promising for most small health technology companies. Furthermore, for similar reasons, markets such as China and Japan are becoming increasingly attractive to companies, posing a risk of shifting regulatory efforts and, consequently, creating shortages of innovative MD in the European market.

Example of a post-market study

To obtain CE MDR marking, iVascular undertook a clinical development plan for a class III legacy coronary device—a coronary angioplasty balloon catheter—after it had already been commercialized. Devices certified under previous MD legislations are termed “legacy MD” indicating they fall within a transitional period for adherence to current legislation. Post-market surveillance must confirm the safety and performance of the product throughout its expected lifespan, identify and analyze emerging risks, ensure benefit-risk acceptability, and identify possible systematic misuse or unforeseen uses. Initially, the clinical development plan was prepared, establishing 2 activities. Activity #1 was a questionnaire activity in which a specific survey about the product was conducted, including variables of safety and clinical performance, later submitted to interventional cardiologists using the device. Activity #2 consisted of a clinical, observational, prospective, and multicenter trial to evaluate the safety and clinical performance in a real-world population and following the manufacturer’s instructions for use. The study was approved by the DREC of each center. After completing the sample size and performing the statistical analysis, a clinical report was prepared and sent to the NB, where the MD result was validated, and CE marking was granted.

Despite iVascular success, in its experience this company acknowledges that the lack of feedback from the NB, whose advice and approval could facilitate the preparation of the clinical development plan. Additionally, the absence of a template for the clinical development plan and questionnaire activity were significant limitations in the procedure. A similar process in the United States could have included dialogue with the FDA to reach consensus on the study design and, potentially, to use the Breakthrough Device Designation program to expedite approval. Although deadlines are more defined in China and Japan, a local clinical trial is required for device approval as well. Despite these advantages, having a dialogue going does not guarantee faster approval, as it will depend on the needs of the required clinical trial.

THE COLLABORATORS’ PERSPECTIVE

The demanding requirements for the development of a MD have led most researchers and manufacturers to require the support of collaborating companies for the proper fulfillment of the different needs of increasingly complex clinical trials. There are several aspects in which collaborating companies can offer a service while developing a MD. In fact, due to current limitations of medical researchers and MD developers, there are CRO (contract research organizations), that is, companies that offer support for clinical research from a global perspective, managing the design of the clinical trial, collecting data and analysis, regulatory issues, monitoring clinical trials, auditing, and handling quality control. Tthe activities for which researchers and manufacturers demand support from external collaborators are mentioned below.

Database creation and analysis

The creation of adequate databases is an essential part of clinical research development to ensure the recording of all important variables that influence the study. In addition, these databases must be accessible to researchers and adequately completed. For this purpose, companies that support database design can provide essential assistance to researchers in developing databases and appropriate forms, as well as in clinical follow-up, data curation, and analysis. These skills may require specific computer knowledge that researchers do not always have. Additionally, the availability of combined online databases minimizes the risk of transcription errors and clinical follow-up errors through adequate coordination of multiple centers in multicenter studies or clinical trials. Outsourcing this process can alleviate the workload of researchers and avoid errors in each of the steps.

Unification of health records

A major barrier in Spain to conducting Real World Evidence studies is the limited access to data nationwide. The fact that each autonomous community has independent databases inaccessible to all national researchers complicates data extraction and analysis on a global scale. In this regard, specific platforms have been developed to unify health care databases across regions with heterogeneous databases, as it is the case with Spain. A unified platform could provide a series of benefits compared with the current system. For starters, from the perspective of each patient, who could travel across the national territory and have access to the results of previous tests performed in other autonomous communities, it would facilitate health care. On the other hand, regarding clinical research, it would allow drawing unified data, providing versatility in export and communication with organizations and states, and participation in joint research projects.

Ethical and legal considerations

While having a large amount of health care data can be an attractive idea for researchers, this raises ethical questions about data protection related to patients. There are consultancies specialized in information security in the health care sector. This area is notable for the complex existing legislation in the field of patient safety and privacy as a fundamental right of individuals. It is common for researchers or manufacturers, who devote their effort and expertise to developing a study or MD, to be unfamiliar with the complexities of the legislation governing this field. Therefore, these types of companies can provide substantial support in the development of MD research, ensuring compliance with all necessary legal requirements and facilitating the performance of other tasks for researchers and manufacturers.

THE INVESTIGATOR’S OUTLOOK

From the investigator’s standpoint, the emergence of a new legislation implies an additional effort for their study and evaluation to carry out projects efficient and effectively. The new legislation has triggered several doubts in the research community and slowed down, at least temporarily, the development of MD. In this regard, the organization of updating meetings with a cross-cutting approach facilitates the understanding of these complex regulations, supports the investigator, and allows for the establishment of valuable professional networks that enhance scientific, regulatory, and industrial collaboration.

As seen throughout this document, the role of the investigator as an expert in certain MD is of paramount importance. Both the AEMPS and the DREC will frequently require the evaluation of certain projects by panels of experts; in addition, manufacturers should consult with experts on projects before submitting them to official bodies. Therefore, having a solid and experienced group of experts is a crucial necessity for conducting effective investigations and critically evaluating new MD applications in collaboration with official bodies.

Finally, many promising projects initiated by investigators to address academic or clinical questions are often delayed or discontinued because of insufficient funding. This challenge is particularly relevant to the development of randomized clinical trials—the gold standard of clinical research—which typically incur higher costs, including those associated with participant health insurance. MD research, on the other hand, may present a less attractive focus for the investigator. However, the importance of post-authorization studies should not be underestimated since due to studies like these, MD and drugs with effects not identified in clinical trials, sometimes harmful to patients, have been identified, leading to their withdrawal from the market.

THE PATIENT’S OUTLOOK

In this complex landscape, it is easy to lose sight of the ultimate goal of MD development: to improve population health and patient outcomes, with patients as the final recipients of these devices. Thus, their perspective is very important and raising awareness about the complexity of health technology development and the multiple requirements needed to obtain safe and effective MD is beneficial for both the patients and all other parties involved in this process. Limiting patient participation to the signing of informed consent minimizes their involvement in the process and can generate distrust towards researchers, manufacturers, and regulatory bodies. In contrast, explaining the MD development process clearly and simply can bring this complex world closer to patients. In fact, DREC already require the inclusion of patient representatives as part of the committee. Other examples include direct consultation with patient groups during study design, their participation in defining research priorities, the development of comprehensible information materials for participants, and their collaboration in the interpretation and dissemination of results. These forms of participation seek to strengthen transparency, improve the relevance of studies, and foster trust in research processes. All these aspects are an important step to encourage patient participation in clinical trials and ensure active follow-up and compliance that will, ultimately, positively impact individual and population health.

CONCLUSIONS

The European EU-MDR legislation has brought substantial changes to the MD development process to unify and ensure the safe and effective development of new MD. Although its implementation entails challenges and threats for MD research in the European Community, the collaboration of the multiple actors involved and sharing their perspectives help to understand the procedure as a whole and facilitate a more harmonious and unified process.

FUNDING

Fundación Epic organized the meeting and covered all expenses. The IE (Instituto de Empresa) provided the facilities for the Epic MDR25 meeting.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This article is a review of previously published literature and does not involve original studies with human beings or animals by the authors. Therefore, it was deemed unnecessary to obtain approval from an ethics committee.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence program was used for the writing of this document.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J. Zubiaur and A. Pérez de Prado drafted the first version of the text. J.R. Rumoroso Cuevas, M.C. Rodríguez Mateos, G. Hernández, I. Alfonso Farnós, M. Aláez, S. Pich, J. Martorell, E. Paredes, A. Escario, P.P. Fernández Rivero, E. Jiménez-Carles, and A. Pérez de Prado contributed to the elaboration of the content from which the information for the drafting of the document was obtained. All authors reviewed the final version of the article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Pérez de Prado is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure the impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. J.R. Rumoroso Cuevas is the general director of Fundación Epic. I. Alfonso Farnós is the president of ANCEI. M. Aláez works at FENIN. S. Pich works at iVascular. J. Martorell is the founder and works at Aortyx. E. Paredes is the founder and works at pInvestiga. A. Escario works at Madrija. P.P. Fernández Rivero works at Start Up SL. E. Jiménez-Carles is the general director and works at Soinde Neuro SL.

REFERENCES

1. Regulation 2017/745 EN Medical Device Regulation EUR-Lex. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/745/oj/eng. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

2. Regulation (EU) 2017/746 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices and repealing Directive 98/79/EC and Commission Decision 2010/227/EU (Text with EEA relevance). OJ L Apr 5, 2017. Available at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/ 2017/746/oj/eng. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

3. Ministerio de Sanidad. Real Decreto 192/2023, de 21 de marzo, por el que se regulan los productos sanitarios. Sec. 1, Real Decreto 192/2023 mar 22, 2023 p. 42678-42706. Available at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2023/03/21/192. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

4. Fraser AG, Byrne RA, Kautzner J, et al. Implementing the new European Regulations on medical devices —clinical responsibilities for evidencebased practice:a report from the Regulatory Affairs Committee of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J.2020;41:2589-2596.

5. Spitzer E, de la Torre-Hernández JM, Guðmundsdóttir Ingibjörg J, et al. Use of cardiovascular registries in regulatory pathways:perspectives from the EU-MDR Cardiovascular Collaboratory. REC Interv Cardiol.2024;6:213-223.

6. DocsRoom European Commission. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/docsroom/documents/10337/attachments/1/translations. Accessed 21 Jan 2025.

7. Biomed Alliance. Biomed Alliance response to JRC consultation on medical devices clinical investigation summary reporting requirements. 10 sep 2018. Available at: https://www.biomedeurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Biomed_Alliance_Response_to_JRC_Consultation_10_Sep_2018-2.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

8. Jefatura del Estado. Ley 14/2007, de 3 de julio, de Investigación biomédica. Sec. 1, Ley 14/2007 jul 4, 2007 p. 28826-28848. Available at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2007/07/03/14. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

9. Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Real Decreto 1090/2015, de 4 de diciembre, por el que se regulan los ensayos clínicos con medicamentos, los Comités de Ética de la Investigación con medicamentos y el Registro Español de Estudios Clínicos. Sec. 1, Real Decreto 1090/2015 dic 24, 2015 p. 121923-121964. Available at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2015/12/04/1090. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

10. Regulation 2017/746 EN Medical Device Regulation EUR-Lex. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2017/746/oj/eng. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

11. WMA The World Medical Association Declaración de Helsinki de la AMM Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas con participantes huma-nos. Available at: https://www.wma.net/es/policies-post/declaracionen-seres-humanos/. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

12. UNE-EN ISO 14155:2021 Investigación clínica de productos sanitarios. Available at: https://www.une.org/encuentra-tu-norma/busca-tu-norma/norma?c=N0066686. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

13. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. 2023 Instrucciones de la AEMPS para la realización de investigaciones clínicas con productos sanitarios en España. Available at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/productos-sanitarios/investigacionclinica-productossanitarios/instruccionessanitarios-en-espana/. Accessed 17 Jan 2025.

14. Guidance MDCG endorsed documents and other guidance European Commission. 2025. Available at: vices-sector/new-regulations/guidance-mdcg-endorsed-documents-and-oth-er-guidance_en. Accessed 27 Jan 2025.

15. BOE.es DOUE-L-2023-80401 Reglamento (UE) 2023/607 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo de 15 de marzo de 2023 por el que se modifican los Reglamentos (UE) 2017/745 y (UE) 2017/746 en lo que respecta a las disposiciones transitorias relativas a determinados productos sanitarios y a productos sanitarios para diagnóstico in vitro. Available at: Error!Hyperlink reference not valid.. Accessed 23 Jan 2025.

16. COCIR. COCIR Position on the Future Governance Framework for the Medical Technologies Sector. Available at: framework-for-the-medical-technologies-sector. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

17. MedTech Europe. MedTech Europe 2024 Regulatory Survey:key findings and insights. Available at: library/medtech-europe-2024-regulatory-survey-key-findings-and-insights/. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.

18. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Breakthrough Devices Program. FDA. 11 de julio de 2024. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/ how-study-and-market-your-device/breakthrough-devices-program. Accessed 18 Jan 2025.