Original article

Optical coherence tomography for the diagnosis and management of stent thrombosis

Tomografía de coherencia óptica en el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la trombosis del stent

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias, Spain

bServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, IIS-IP, Madrid, Spain cCentro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Madrid, Spain dServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de Cabueñes, Gijón, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) is increasingly used in complex percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), particularly in cases of “balloon failure,” which includes both uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions. Although these 2 scenarios represent distinct technical and clinical challenges, they are usually evaluated using the same safety and efficacy endpoints. As a result, there is a lack of specific evidence on the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in each of these situations. Furthermore, the role of intracoronary imaging in optimizing ELCA use remains insufficiently defined.

Methods: This will be an investigator-initiated, multicenter, single-arm, open-label, prospective observational study. Patients with an indication for PCI and undilatable (non-compliant balloon dilatation < 80% at burst pressure) or uncrossable (uncrossable with a “small-profile balloon” with adequate support, left to the operator’s discretion) coronary artery lesions treated with ELCA will be included. Intravascular imaging will be highly advised and analyzed in a core laboratory. Device success, angiographical success, procedural success, clinical success and related complications will be evaluated. Patients will be postoperatively followed for 1 year and clinical events will be recorded.

Conclusions: The LUDICO study will be a multicentre, prospective study of ELCA therapy in uncrossable or undilatable coronary lesions. The study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in these lesions as well as the clinical results at the 1 year follow-up in this setting. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT07206082).

Keywords: Percutaneous coronary intervention. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy. Intravascular imaging. Optical coherence tomography. Complex coronary intervention.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La aterectomía coronaria con láser de excímeros (ELCA) se utiliza cada vez más en intervenciones coronarias percutáneas (ICP) complejas, en particular en caso de «fallo del balón», que incluye tanto lesiones coronarias no cruzables como no dilatables. Aunque estos 2 escenarios representan desafíos técnicos y clínicos distintos, con frecuencia se han evaluado utilizando los mismos criterios de efectividad y seguridad. Como resultado, existe una falta de evidencia específica sobre la seguridad y la efectividad de la ELCA en cada una de estas situaciones. Además, el papel de la imagen intracoronaria en la optimización del uso de la ELCA sigue estando insuficientemente descrito.

Métodos: Se trata de un estudio observacional prospectivo, abierto, multicéntrico e iniciado por los investigadores. Se incluirán pacientes con indicación de ICP y lesiones coronarias no dilatables (dilatación con balón no distensible < 80% a presión de ruptura) o no cruzables (no cruzables con un balón de bajo perfil y adecuado soporte, a criterio del operador) tratados con ELCA. Se recomendará el uso de imagen intravascular, que se analizará en un laboratorio central. Se evaluarán el éxito del dispositivo, el éxito angiográfico, el éxito del procedimiento, el éxito clínico y las complicaciones asociadas. Se seguirá a los pacientes durante 1 año tras el procedimiento y se registrarán los eventos clínicos.

Conclusiones: El estudio LUDICO será un estudio prospectivo y multicéntrico sobre el uso de ELCA en lesiones coronarias no cruzables o no dilatables. Su objetivo es evaluar la efectividad y la seguridad de la ELCA en estas situaciones, así como los resultados clínicos durante un seguimiento de 1 año. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT07206082).

Palabras clave: Intervención coronaria percutánea. Aterectomía coronaria con láser de excímeros. Imagen intravascular. Tomografía de coherencia óptica. Intervención coronaria compleja.

Abbreviations

ELCA: excimer laser coronary angioplasty. IVUS: intravascular ultrasound. OCT: optical coherence tomography. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. RA: rotational atherectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) has been applied since the 1980s in multiple anatomical and clinical settings, with several studies supporting its safety and efficacy profile.1,2 Common indications include in-stent restenoses, stent underexpansion, calcified coronary lesions, saphenous vein graft stenoses, thrombotic lesions, bifurcations, and chronic total coronary occlusions.3-14 In practice, however, ELCA is predominantly used in the setting of balloon failure–specifically uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions. However, historical studies have typically applied a uniform definition of device success across both lesion types, potentially overlooking important nuances that could influence outcomes and therapeutic decision-making.

Furthermore, despite growing recognition of the value of intracoronary imaging in optimizing complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),15 prior ELCA studies have largely underutilized this tool, limiting insight into the mechanisms of success or failure in balloon-resistant lesions.

The safety and efficacy profile of coronary laser in undilatable and uncrossable lesions (LUDICO) study is a real-world, observational study designed to evaluate the use of ELCA specifically in cases of balloon failure. The study has 2 primary objectives: a) to refine the definition of ELCA procedural success based on the type of balloon failure encountered—distinguishing between uncrossable and undilatable lesions—, and b) to emphasize the critical role of intracoronary imaging in guiding ELCA and interpreting procedural outcomes. By addressing these critical gaps, the study aims to provide a more precise and and clinically meaningful framework for the contemporary use of ELCA in complex coronary interventions.

METHODS

Study design and population

This is a prospective, multicentre, observational study including consecutive patients undergoing ELCA in undilatable (expansion < 80% of the distal vessel diameter after inflation of a 1:1 non-compliant balloon at 18 atm) and uncrossable coronary artery lesions (uncrossable after using a small-profile balloon with adequate support left to the operator’s discretion). At least 15 national centers will be contacted to participate in the study. Participant centers will be required to have experience with ELCA and complex PCI, with a minimum of > 5 prior ELCA cases performed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in table 1. This study was conducted in full compliance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.16 The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07206082).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Patients > 18 | Patients with known allergies to ASA, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor |

| Patients with either stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes as the clinical presentation | Patients unable to provide informed consent, either personally or through a legal representative |

| Patients with severe coronary lesions (> 70% by visual estimation) in native vessels or coronary bypass grafts | Patients with clinical or hemodynamic instability defined as: sustained hypotension (SBP ≤ 90 mmHg for ≥ 30 minutes or use of pharmacological, or mechanical support to maintain an SBP ≥ 90 mmHg) or evidence of end‐organ hypoperfusion including urine output of < 30 mL/h, cool extremities, altered mental status, or serum lactate > 2.0 mmol/L |

| “Uncrossable” coronary lesions (eg, lesions that cannot be crossed with a 0.7:1 balloon after successful guidewire passage) or “Undilatable” lesions (eg, those in which balloon dilation with a 1:1 non-compliant balloon at 18 atm results in < 80% expansion relative to the distal reference vessel diameter; this group includes both de novo lesions and in-stent restenosis or underexpanded stents) |

Patients with significant comorbidities and a life expectancy of < 1 year |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; SBP, systolic blood pressure. |

Procedure

PCI will be performed in accordance with current clinical practice guidelines on coronary revascularization.15,17

In uncrossable lesions, following successful guidewire passage and failed balloon crossing, ELCA will be performed (as described in the following section). PCI will be completed with optional predilatation at the operator’s discretion, followed by stenting or drugcoated balloon implantation. Intravascular imaging [preferably with optical coherence tomography (OCT)] will be recommended after laser application to characterize the lesion substrate and evaluate the effect of the laser and at the end of the procedure.

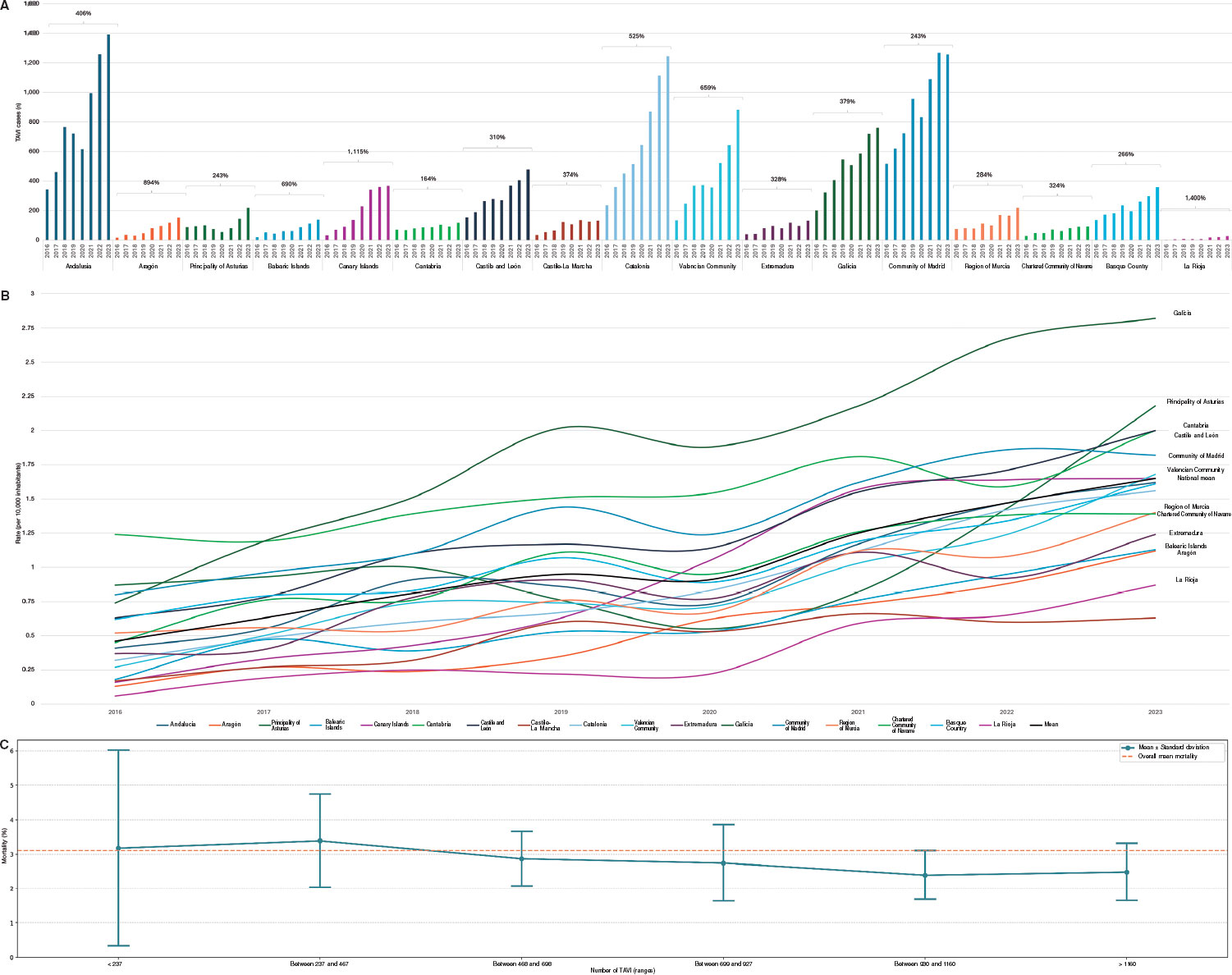

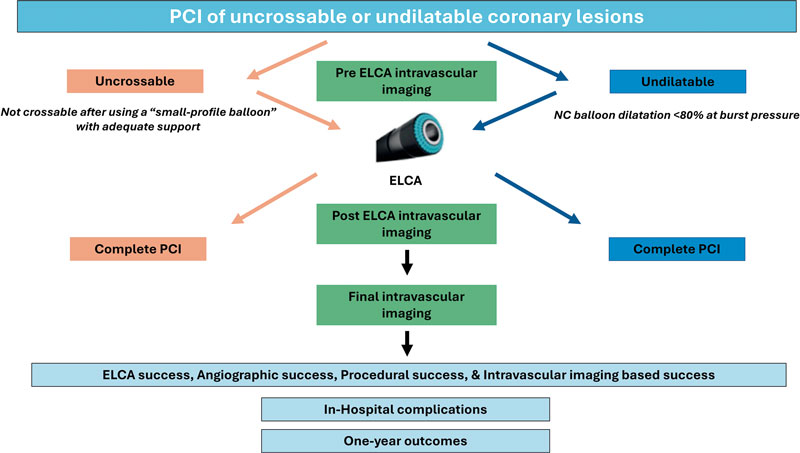

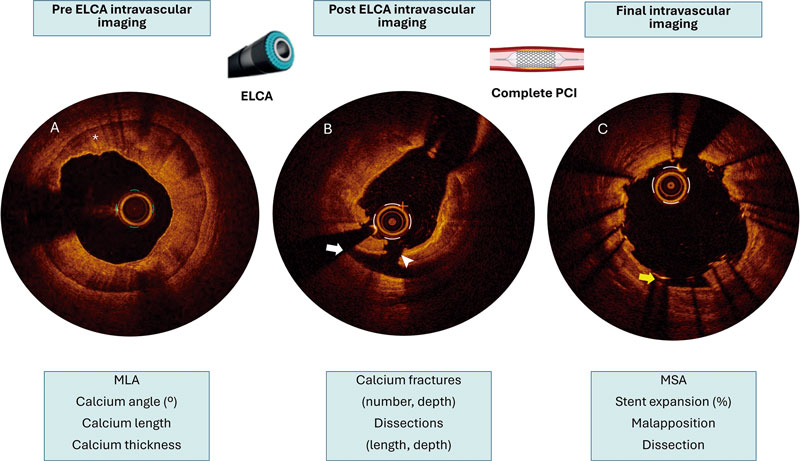

In undilatable lesions, if balloon dilation is inadequate, an initial intracoronary imaging assessment will be conducted. Afterwards, laser atherectomy will be performed, followed by a second intracoronary imaging assessment to evaluate the effects of ELCA on the lesion. PCI will, then, be completed with balloon dilation and stenting or drug-coated balloon implantation, at the operator’s discretion. A third intracoronary imaging pullback will be performed to assess the final procedural outcome (figure 1).

Figure 1. Central illustration. LUDICO study flowchart. ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; NC, non-compliant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Laser atherectomy technique

ELCA procedure will be performed using the Spectranetics CVX300 (Spectranetics, United States) and the latest generation Philips Laser System Excimer (Philips, United States) System, which is based on pulsed xenon‐chlorine laser catheters capable of delivering excimer energy (wavelength, 308 nm; pulse length, 185 ns) from 30 mJ/mm2 to 80 mJ/mm2 (fluencies) at pulse repetition rates of 25 Hz to 80 Hz.

The ELCA technique will be performed according to current recommendations.18 The choice of laser catheter size will be left to the operator’s discretion, selecting among the available rapid-exchange concentric probes (0.9 mm, 1.4 mm, 1.7 mm, or 2.0 mm). The selection of fluence, and repetition rate will be left to the operator’s discretion. A saline infusion technique will be recommended, although application of laser with blood or contrast will be recommended in resistant lesions. In the event of unsuccessful initial therapy, additional plaque modification techniques may be employed at the operator’s discretion and will be thoroughly recorded and described.

Clinical definitions and follow-up

Laser success will be defined differently for uncrossable and for undilatable lesions. For the former, laser success will be defined as the ability of the laser catheter to cross the lesion. Laser success will also be considered in cases where the laser catheter cannot cross the lesion but proximal laser application permits subsequent balloon crossing. For the latter, laser success will be defined as successful balloon dilation (sized 1:1 to the vessel diameter), with adequate expansion (> 80% in 2 orthogonal projections) following laser therapy without the need for other plaque modification technique.

Angiographic success will be defined as Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade-3 final flow and a percent diameter stenosis < 20%. Procedural success will be defined as angiographic success without severe procedural complications (death, coronary perforation, abrupt vessel closure, flow-limiting dissection). Intracoronary imaging-based success will be defined as a stent expansion ≥ 80% (OCT or intravascular ultrasound [IVUS]) or a minimal stent area (MSA) ≥ 4.5 mm2 in OCT or ≥ 5.5 mm2 in IVUS.

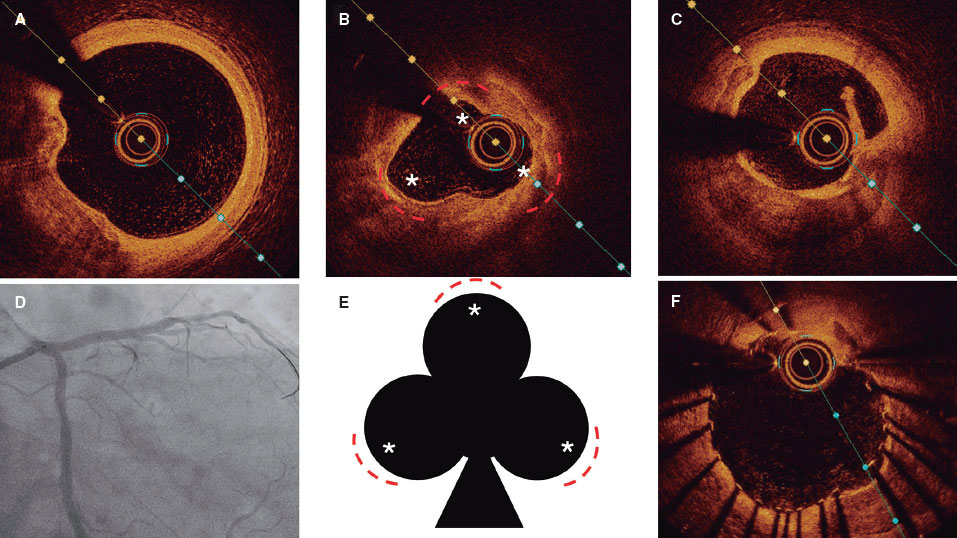

Intracoronary imaging

Intracoronary imaging will aim to describe the lesion characteristics and identify potential predictors of adequate stent expansion and procedural result. Therefore, intracoronary imaging will be highly recommended and the advised imaging modality will be OCT as its better spatial resolution vs IVUS allows better tissue characterization, plaque modification assessment and visualization of stent failure etiologies.19 A baseline intracoronary imaging evaluation is recommended, when possible, to describe the lesion characteristics and identify potential predictors of ELCA success or failure. Additionally, a second intracoronary imaging run is strongly advised immediately after laser therapy. This second run aims to describe the effect of ELCA in the coronary plaque. Evaluating and characterizing changes in the coronary plaque might help guide the optimal ELCA result and allow appropriate adjustment of therapy settings (fluence, repetition rate and infusion characteristics). Finally, a postoperative intravascular imaging run is strongly recommended once the final angiographic result is achieved. All intracoronary imaging data will be analyzed by a core laboratory. In the baseline intracoronary imaging run, lesion characteristics will be described as follows: minimum lumen area (MLA), minimum and maximum lumen diameter, lesion length, calcification angle, calcification thickness. In the post-ELCA imaging run the following parameters will be evaluated: MLA, number of calcium fractures and characteristics, presence of dissection, including its angle and length. In the final imaging run, MSA, stent apposition and dissections will be described. In both OCT and IVUS assessments, a dual-reference approach will be used: the proximal and distal reference lumen diameters will be identified, and MSA will be divided by each of these diameters separately. The final stent expansion index will be calculated as the mean of the 2 resulting values. Second, the tapered mode is only available in OCT: reference lumen profile is estimated based on the distal and proximal reference frame mean diameter and side branch mean diameter in between. With stent lengths > 50 mm, the dual method is preferred. With stent lengths < 50 mm the tapered method is often used. If the dual method is used, the stent expansion percentage of both segments will be recorded with the lower value of the two measurements used for analysis. The main variables to be evaluated by intravascular imaging are summarized and graphically shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of the advised intracoronary imaging assessment in LUDICO study. A: baseline optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of a severely calcified lesion. The asterisk points to a calcium arc of 360° with a maximum thickness of 0.9 mm. B: OCT image after ELCA with contrast media. White arrow points to a dissection. The white arrowhead points to a deep calcium fracture. C: results after stenting. The yellow arrow points to a small area of malapposition. ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; MLA, minimal lumen area; MSA, minimal stent area; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted at 3 different timeframes:a) after PCI; procedural success and complications will be thoroughly documented, and all patients will be evaluated for any postoperative events, such as chest pain, heart failure, bleeding, or ischemic events; b) at hospital discharge, documenting clinical status, complications and antiplatelet therapy; and c) 1 year after the index PCI; clinical events and antiplatelet therapy will be recorded.

The primary endpoint at the follow-up will be the composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as the occurrence of cardiac death, target vessel-related acute myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, or definite/probable stent thrombosis. Secondary efficacy endpoints will include all-cause mortality, cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and target vessel revascularization. Secondary safety endpoints will include stroke and bleeding events (classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] criteria). Endpoint definitions are shown in table 2.

Table 2. Procedural and clinical definitions

| Procedural definitions | |

|---|---|

| ELCA success | Uncrossable: defined as the ability of the laser catheter to cross the lesion or allow subsequent crossing with a predilatation balloon following laser application |

| Undilatable: defined as successful balloon dilation with adequate expansion following laser therapy | |

| Angiographic success | Defined adequate stent implantation and expansion, with residual stenosis < 20% and TIMI grade-3 flow, without crossover to another plaque modification technique |

| Procedural success | Angiographic success without severe procedural complications (death, coronary perforation, abrupt vessel closure, flow-limiting dissection) |

| Imaging based success | Defined as a stent expansion ≥ 80% (OCT or IVUS) or a MSA ≥ 4.5 mm2 in OCT or ≥ 5.5 mm2 in IVUS |

| Severely calcified coronary lesion | Angiographically: opacification in both sides of the artery before contrast administration |

| Intracoronary imaging: > 180° calcium arc or calcium thickness > 5 mm | |

| Clinical definitions | |

| MACE | Defined as the occurrence of cardiac death, target vessel-related acute MI, target vessel revascularization, or definite/probable stent thrombosis |

| Cardiac death | According to ARC definitions:31

|

| Non-fatal MI | Third universal definition of MI.32 In addition, procedure-related myocardial infarction—defined as a troponin elevation > 5 times the upper limit of normal in patients with previously normal troponin levels, or a ≥ 20% increase in patients with previously elevated troponin levels, along with electrocardiographic changes or new areas of myocardial necrosis detected by imaging—was included |

| Stent thrombosis | According to ARC criteria:

|

| Stroke | New neurological focal deficit with imaging confirmation and assessed by a neurologist |

| TLR | New coronary artery lesion in the previously treated coronary lesion including 5 mm proximal and distal to the implanted stent |

| TVR | New coronary artery lesion in the previously treated coronary vessel |

| Hemorrhage | According to BARC classification33 |

|

ARC, Academic Research Consortium; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; ECG, electrocardiogram; ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; MSA, minimal stent area; OCT, optical coherence tomography; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization. |

|

Sample size estimation

The planned sample size of 230 patients was determined based on expected device success rates reported in prior studies of ELCA for undilatable and uncrossable lesions. Assuming a conservative laser success rate of 80%, a cohort of 230 patients would yield a 95% confidence interval with a precision of approximately ± 5% (estimated range, 74.8%–85.2%), which is considered adequate for reliably estimating procedural efficacy in the routine clinical practice. Moreover, this sample size ensures sufficient statistical power to support multivariable analyses of predictors of both intraoperative and follow-up outcomes. With an anticipated 40–50 events, the study would allow the inclusion of approximately 4 to 5 covariates in multivariable regression models while maintaining acceptable model stability. Based on the expected procedural volume at each participant center and the required sample size, the recruitment period is 2 to 3 years.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables following a normal distribution will be expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Those not following a normal distribution will be reported using the median and minimum and maximum values. Qualitative variables will be expressed as absolute numbers and frequencies.

A significance level of 0.5 will be considered, and 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for the primary outcome variables. Normality of the data will be assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on the distribution, appropriate statistical tests will be applied to compare relevant variables. For comparisons of means, the Student t test for independent samples will be used, or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test in case of dichotomous qualitative variables. For comparisons involving non-dichotomous qualitative variables, ANOVA or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test will be employed. For bivariate analysis of qualitative variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test will be used.

Multivariate analysis will be conducted using forward stepwise Cox regression analysis. Event-free survival curves will be constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Variables will be considered potential risk predictors in the multivariate model if they demonstrate a statistically significant association in the univariate analysis or show a trend toward significance. All statistical analyses will be conducted using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp, United States).

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines, including the most recent ICH E6 (R3) update. Before enrollment, patients or their legal representatives must be fully informed about the nature of the study and must provide written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participant center.

DISCUSSION

The LUDICO study will be a multicenter study to assess the safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes of ELCA specifically in undilatable or uncrossable coronary artery lesions with lesion-specific endpoints and preferential use of intravascular imaging. We believe that this real-life approach will provide valuable insights into the 2 main clinical scenarios in which ELCA is currently used.

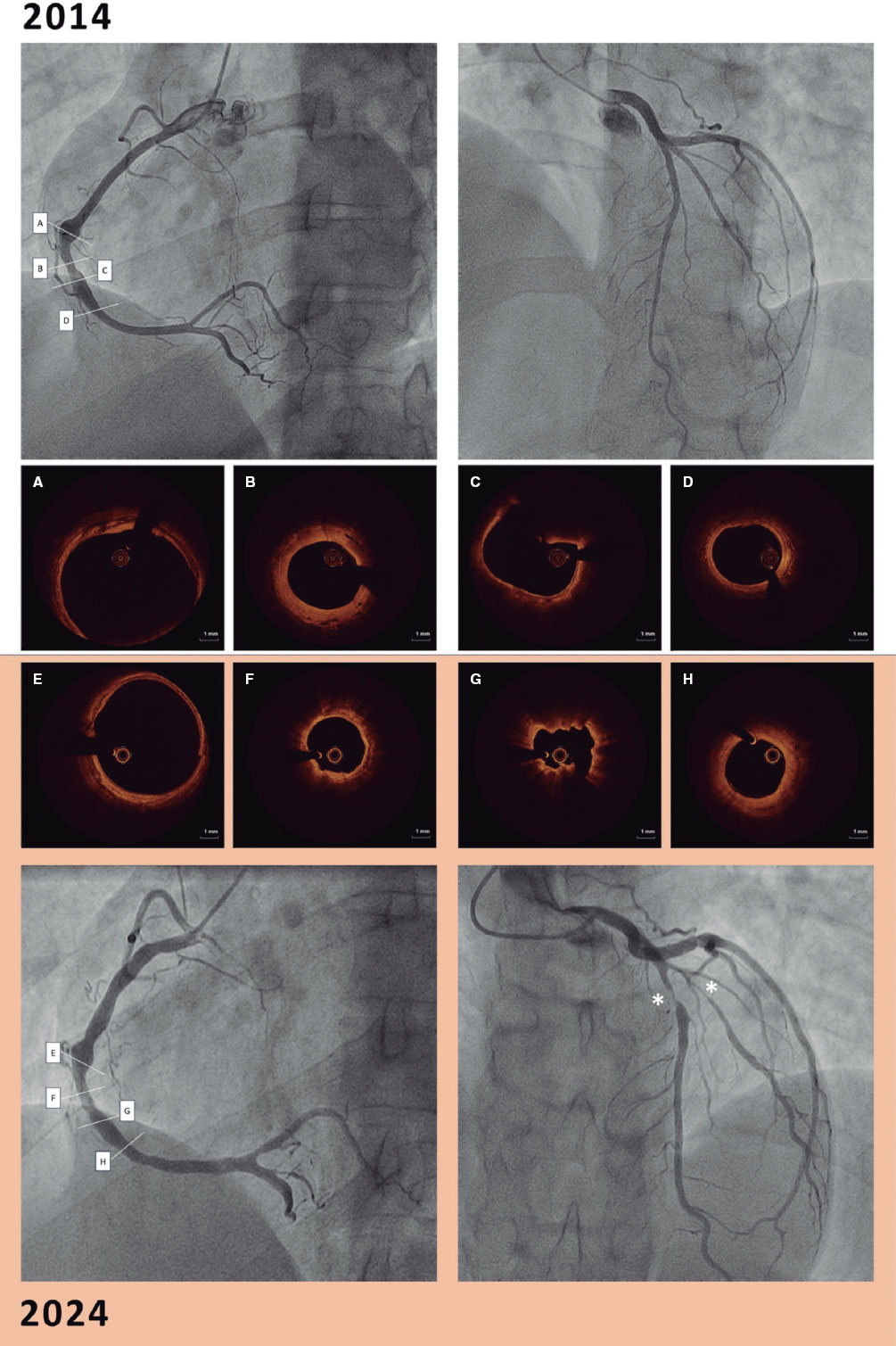

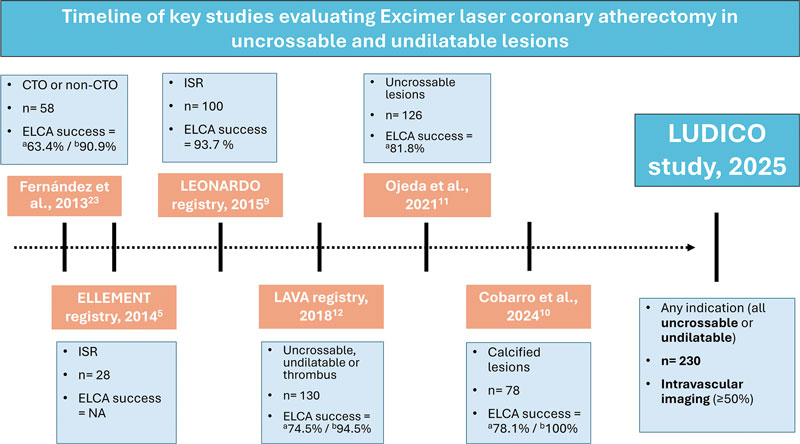

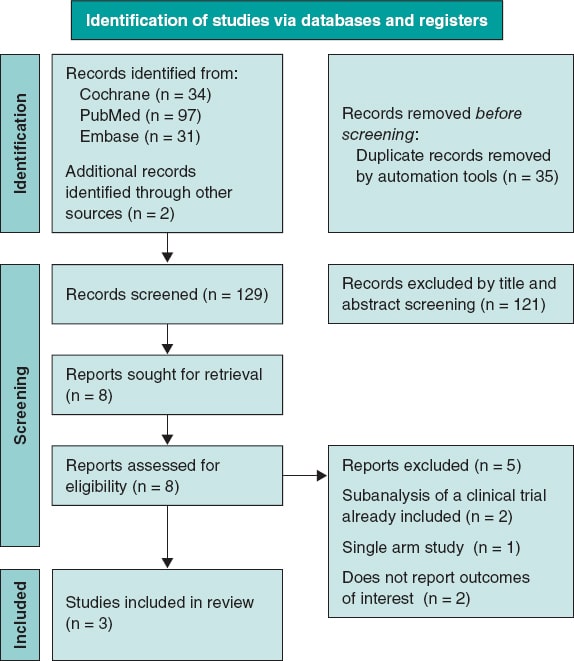

Three recent large registries confirmed ELCA to be a safe technique with an assumable rate of complications.20-22 However, these studies analyzed the overall procedural performance but failed to describe the lesion specific characteristics or intravascular imaging data. The findings of studies reporting balloon failure scenarios5,10-12,23,24 are summarized in figure 3. The LAVA multicenter registry set the main contemporary clinical indications for ELCA.12 This registry analysed ELCA use in 130 lesions and stratified them in 3 scenarios: uncrossable, undilatable and thrombotic. The LAVA and other studies analyzing ELCA has shown good performance of ELCA in balloon-failure, with lower rates of ELCA success in uncrossable vs undilatable lesions. However, one significant limitation is present in these studies: situations of balloonfailure include undilatable, uncrossable, or lesions with both components. In the routine clinical practice, these 2 situations are distinct; however, ELCA success has often been defined uniformly, potentially confounding the real efficacy of the device. Consequently, the LUDICO study aims to address this issue by specifically defining 2 endpoints based on the type of balloon failure, uncrossable or undilatable.

Figure 3. Timeline of key studies evaluating ELCA in uncrossable and undilatable lesions. CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; NA, not available; ISR, in-stent restenosis. a Uncrossable lesions. b Undilatable lesions.

Nonetheless, the definition of ELCA success in uncrossable lesions might be ambiguous in some cases. For instance, cases in which neither the ELCA catheter nor subsequent balloons are able to cross the lesion should not be considered procedurals failures if a microcatheter can subsequently cross and enable successful completion of the procedure using the RASER technique—a combination of ELCA and rotational atherectomy (RA). However, to simplify the endpoint, we have considered this situation a crossover to RA. In contrast, for undilatable lesions, the definition of ELCA success is less prone to interpretation; however, clearly defining what constitutes an undilatable lesion remains essential. This highlights the importance of a compliance test —that is, performing an initial balloon dilatation to objectively demonstrate that the lesion cannot be adequately expanded. Such a test is critical to identify lesions that are likely to benefit from plaque modification techniques, including ELCA. Arguably, the results of some randomized controlled trials in plaque modification devices (such as ECLIPSE25 using orbital atherectomy and ROLLERCOASTR7 using ELCA, intravascular lithotripsy and RA) may have been influenced by the absence of “compliance test”, potentially including coronary lesions in which plaque modification would not have been necessary after balloon testing, thereby reducing the differences across groups. Additionally, the recent CRATER trial showed that a total of 20.9% of patients in bailout RA group required crossover to RA because of balloon failure,26 which highlights the high frequency of this situation and underscores the importance of its prompt identification to select the most appropriate plaque modification technique such as ELCA.

RA is the most extensively studied strategy for managing uncrossable coronary lesions, supported by wide clinical experience and robust evidence.7,26,27 However, RA presents important limitations in specific scenarios where ELCA may offer clear advantages —such as in-stent restenosis or bifurcation lesions requiring side branch protection—given the risk of scaffold damage or distal embolization of debris.28 Orbital atherectomy, although less studied in uncrossable lesions,29,30 shares similar drawbacks due to its ablative mechanism. By contrast, ELCA is compatible with 6-Fr catheters, can be used over any standard guidewire, and has a less demanding learning curve.18 Of note, while RA demonstrates limited efficacy against deep calcium, ELCA can affect both superficial and deep calcification.4 Collectively, these features position ELCA as a uniquely valuable tool among plaque-modification techniques. Its capacity to safely treat in-stent restenosis, thrombotic lesions, uncrossable lesions, and bifurcations requiring side branch protection underscores advantages not readily attainable with RA or orbital atherectomy, thereby reinforcing ELCA as a superior alternative in selected complex PCI scenarios.

In conclusion, the use of intravascular imaging has been limited in most of the studies that have evaluated ELCA in balloon-failure, particularly those focused on uncrossable lesions. Additionally, none of these studies have described the findings of intravascular imaging before and after ELCA and identified potential predictors of success. In fact, the effect of ELCA in intravascular imaging remains an open question as there is a paucity of studies that have evaluated it and have been limited to in-stent restenosis.4 Therefore, one of the aims of the LUDICO study is to evaluate the effects of ELCA by intravascular imaging (preferably by OCT, due to its better spatial resolution) and identify potential predictors of ELCA success or failure and its effect on the coronary plaque. We hypothesize that recognizing potential predictors in intravascular imaging could help operators guide the procedures and identify the anatomical characteristics that best predict a favourable outcome with ELCA, thereby optimizing patient selection and procedural planning.

Limitations

First, this multicentre prospective study will be conducted in a single country, which may limit the generalizability of its findings to other settings. However, these high-volume centres, with wide experience in complex PCI comply with the international recommendations and their practice is comparable to other similar centres. Second, because of to the nonblinded study design, selection bias may have occurred, whereby certain lesions, such as extremely calcified or highly complex, were preferentially treated with alternative techniques or revascularization strategies. Additionally, there will not be a control group to assess the efficacy of the ELCA therapy vs other therapies. Finally, although intracoronary imaging will be highly recommended, we foresee that the baseline evaluation will be limited to just a few cases. In fact, by definition, uncrossable lesions will rarely have a baseline evaluation. Besides, in the event of the patient having kidney disease, OCT runs could be avoided, conducting to less OCT runs, or even to the absence of intravascular imaging.

CONCLUSIONS

The LUDICO study will be a multicenter, prospective study of ELCA therapy in uncrossable or undilatable coronary artery lesions with specific success definitions for each indication. The study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA and the clinical outcomes during the follow-up. The OCT evaluation will provide insights into the effect of ELCA in this subset of coronary lesions.

FUNDING

The LUDICO study was supported by a non-restricted grant from Biomenco.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained (institutional approval number: 5502), and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to enrolment. The confidentiality and anonymity of participants were strictly preserved throughout the study. Sex and gender considerations were addressed following the recommendations of the SAGER guidelines to ensure accurate and equitable reporting.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence assisted technologies were used exclusively to support language editing and improvement of style. No artificial intelligence tools were employed to generate, analyse, or interpret the data. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity, accuracy, and originality of the manuscript content.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Jurado-Román and J. Zubiaur contributed to the study equally and share first authorship. A. Jurado-Román is responsible of the study conception and design. J. Zubiaur, A. Jurado-Román, and M. Basile were involved in the draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Moreno is associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed; moreover, he has received consulting fees and honoraria/speaker fees from Abbott vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Terumo, and Biotronik. A. Jurado-Román reported receiving consulting fees from Boston Scientific and Philips; honoraria/speaker fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Shockwave Medical, World Medica, and Philips; and serves as a proctor for Abbott, Boston Scientific, World Medica, and Philips. G. Galeote has received honoraria/speaker fees from Meril, Boston Scientific, Abbott SMT, and Biomenco. A. Gonzálvez-García has received honoraria from Abbott. J. Suárez de Lezo has received honoraria/ speaker fees from Abbott and Philips. F. Hidalgo has received honoraria/speaker fees from Philips. M. Basile reported receiving consulting fees and speaking fees from Iberhospitex. B. Garcia del Blanco disclosed his role as a proctor for Edwards Lifescienses and his participation on the Advisory Board of Iberhospitex. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ELCA has demonstrated its usefulness across several challenging lesion subsets, including in-stent restenosis, stent underexpansion, calcified plaques, saphenous vein graft disease, thrombotic lesions, bifurcations, and chronic total coronary occlusions.

- However, in real-world practice, its main indication remains balloon failure, particularly in lesions that are either uncrossable or undilatable.

- Despite this, most earlier studies applied a uniform definition of device success for these distinct scenarios, potentially missing clinically relevant nuances that may affect outcomes and guide treatment strategies.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The LUDICO study is designed as a multicenter investigation to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes of ELCA specifically in undilatable or uncrossable coronary artery lesions, incorporating individualized endpoints for each subset and emphasizing the use of intravascular imaging.

- This real-world strategy is expected to yield meaningful insights into the 2 primary clinical situations in which ELCA is currently employed: uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions.

REFERENCES

1. Choy DS. History of lasers in medicine. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;36 Suppl 2:114–117.

2. Köster R, Kähler J, Brockhoff C, Münzel T, Meinertz T. Laser coronary angioplasty: history, present and future. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2002;2:197–207.

3. Bilodeau L, Fretz EB, Taeymans Y, Koolen J, Taylor K, Hilton DJ. Novel use of a high-energy excimer laser catheter for calcified and complex coronary artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;62:155–161.

4. Lee T, Shlofmitz RA, Song L, et al. The effectiveness of excimer laser angioplasty to treat coronary in-stent restenosis with peri-stent calcium as assessed by optical coherence tomography. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:e279–288.

5. Latib A, Takagi K, Chizzola G, et al. Excimer Laser LEsion Modification to Expand Non-dilatable sTents: The ELLEMENT Registry. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15:8–12.

6. Dörr M, Vogelgesang D, Hummel A, et al. Excimer laser thrombus elimination for prevention of distal embolization and no-reflow in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: results from the randomized LaserAMI study. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116:20–26.

7. Jurado-Román A, Gómez MA, Rivero-Santana B, et al. Rotational Atherectomy, Lithotripsy, or Laser for Calcified Coronary Stenosis. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18:606–618.

8. Giugliano GR, Falcone MW, Mego D, et al. A prospective multicenter registry of laser therapy for degenerated saphenous vein graft stenosis: the COronary graft Results following Atherectomy with Laser (CORAL) trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:84–89.

9. Ambrosini V, Sorropago G, Laurenzano E, et al. Early outcome of high energy Laser (Excimer) facilitated coronary angioplasty ON hARD and complex calcified and balloOn-resistant coronary lesions: LEONARDO Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:141–146.

10. Cobarro L, Jurado-Román A, Tébar-Márquez D, et al. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy in severely calcified lesions: time to bust the myth. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;6:33–40.

11. Ojeda S, Azzalini L, Suárez de Lezo J, et al. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy for uncrossable coronary lesions. A multicenter registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:1241–1249.

12. Karacsonyi M, Armstrong EJ, Huu Tam D, et al. Contemporary Use of Laser During Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: Insights from the Laser Veterans Affairs (LAVA) Multicenter Registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2018;30:195–201.

13. Tomasello SD, Rochira C, Mazzapicchi A, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Excimer Laser Coronary Atherectomy for Complex Coronary Lesions: The ACCELERATE Registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:1630–1638.

14. Basile M, Gómez-Menchero A, Rivero-Santana B, et al. Rotational Atherectomy, Lithotripsy, or Laser for Calcified Coronary Stenosis: One-Year Outcomes From the ROLLER COASTER-EPIC22 Trial. Cath Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:702–710.

15. Vrints C, Felicita Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3415–3537.

16. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–S34.

17. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2024;13:55–161.

18. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O’Kane P. Coronary Intervention with the Excimer Laser: Review of the Technology and Outcome Data. Interv Cardiol. 2016;11:27–32.

19. Nagaraja V, Kalra A, Puri R. When to use intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography during percutaneous coronary intervention? Cardiovasc Diag Ther. 2020;10:1429444–1421444.

20. Sintek M, Coverstone E, Bach R, et al. Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty in Coronary Lesions: Use and Safety From the NCDR/CATH PCI Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010061.

21. Protty MB, Gallagher S, Farooq V, et al. Combined use of rotational and excimer lASER coronary atherectomy (RASER) during complex coronary angioplasty—An analysis of cases (2006–2016) from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society database. Cath Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:E911–E918.

22. Hinton J, Tuffs C, Varma R, et al. An analysis of long-term clinical outcome following the use of excimer laser coronary atherectomy in a large UK PCI center. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;104:27–33.

23. Fernandez JP, Hobson AR, McKenzie D, et al. Beyond the balloon: excimer coronary laser atherectomy used alone or in combination with rotational atherectomy in the treatment of chronic total occlusions, non-crossable and non-expansible coronary lesions. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:243–250.

24. Ambrosini V, Sorropago G, Laurenzano E, et al. Early outcome of high energy Laser (Excimer) facilitated coronary angioplasty ON hARD and complex calcified and balloOn-resistant coronary lesions: LEONARDO Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:141–146.

25. Kirtane AJ, Généreux P, Lewis B, et al. Orbital atherectomy versus balloon angioplasty before drug-eluting stent implantation in severely calcified lesions eligible for both treatment strategies (ECLIPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2025;405:1240–1251.

26. Galeote G, Zubiaur J, Jurado-Román A, et al. Coronary Rotational Atherectomy Elective Versus Bailout in Patients With Severely Calcified Lesions and Chronic Renal Failure (CRATER) Trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:1702–1712.

27. Abdel-Wahab M, Toelg R, Byrne RA, et al. High-Speed Rotational Atherectomy Versus Modified Balloons Prior to Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation in Severely Calcified Coronary Lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e007415.

28. Rivero-Santana B, Galán C, Pérez-Martínez C, et al. ELLIS Study: Comparative Analysis of Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty and Intravascular Lithotripsy on Drug-Eluting Stent as Assessed by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:e014505.

29. Helal A, Ehtisham J, Shaukat N. Overcoming Uncrossable Calcified RCA Using Orbital Atherectomy After Failure of Rotational Atherectomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;105:1265–1268.

30. Bayón J, Mori-Junco RA, Jusková M, Abellas-Sequeiros M, González-Juanatey C. Feasibility and safety of orbital atherectomy in uncrossable lesions. REC: Interv Cardiol. 2025;7:269–271.

31. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351.

32. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567.

33. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Manual thrombectomy (MT) during primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) aims to reduce thrombus burden. Our study evaluates the outcomes and predictors of successful MT.

Methods: The Hunted registry is a retrospective, single-center cohort study including patients who underwent MT during PCI using the Hunter catheter from July 2020 through February 2022. MT success was defined as an angiographic reduction to a Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) thrombus grade of ≤ 2, with clinical follow-up for major adverse cardiovascular events.

Results: Among 750 patients with acute myocardial infarction who underwent PCI, 401 (53%) received MT. The mean age of treated patients was 62 years (80% men). MT was effective in 327 patients (81.55%). Predictors of successful MT included larger vessel diameter (P < .001), high thrombus burden (TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow; P < .001), and non-circumflex target vessels (P < .001). Device-related complications occurred in 17 patients (4.3%). At follow-up, major adverse events occurred in 8.98% of patients at 1 year and in 9.97% at 2 years.

Conclusions: In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing PCI, MT with the Hunter catheter in selected cases with high thrombus burden (TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow), non-circumflex target vessels, and vessel diameters > 2.5 mm, is a safe and effective technique with a low rate of complications.

Keywords: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Manual thrombectomy. Thrombus burden.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La trombectomía manual (TM) en la intervención coronaria percutánea primaria (ICPp) intenta reducir la carga trombótica. Este estudio evalúa los resultados y los factores predictores de éxito de la TM.

Métodos: El registro Hunted es un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo, unicéntrico, de pacientes tratados con TM en ICPp utilizando el catéter Hunter, desde julio de 2020 hasta febrero de 2022. El éxito de la TM se definió como una disminución angiográfica a grado ≤ 2 en la escala Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI), con seguimiento clínico de eventos cardiovasculares adversos mayores.

Resultados: De los 750 pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio tratados con ICPp, en 401 (53%) se realizó TM. Los pacientes tratados tenían una edad media de 62 años y el 80% eran varones. La TM fue efectiva en 327 (81,55%) pacientes. Los predictores de TM efectiva fueron un mayor diámetro del vaso (p < 0,001), una alta carga de trombo (TIMI ≥ 4; p < 0,001) y un vaso diferente de la circunfleja (p < 0,001). Se presentaron complicaciones relacionadas con el dispositivo en 17 pacientes (4,3%). En el seguimiento, el 8,98% presentaron eventos mayores a 1 año y el 9,97% a 2 años.

Conclusiones: En los pacientes con infarto de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST sometidos a ICPp, la estrategia de TM con catéter Hunter, en casos seleccionados con alta carga trombótica (escala TIMI ≥ 4), otros vasos que no fueran la circunfleja y diámetros > 2,5 mm, es una técnica eficaz y segura con una baja tasa de complicaciones.

Palabras clave: Infarto de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST. Intervención coronaria percutánea primaria. Trombectomía manual. Carga trombótica.

Abbreviations

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. MT: manual thrombectomy. PCI: primary coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

INTRODUCTION

In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the treatment of choice is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) performed within the appropriate time window and by experienced operators. PCI has been shown to reduce mortality, reinfarction, and stroke compared with fibrinolysis.1 Among other factors, this benefit may be attributed to greater epicardial reperfusion and higher TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) flow grades and myocardial blush grades achieved with PCI in the culprit artery, all of which are known to influence survival.2,3

PCI have distinctive characteristics, including the presence of a high thrombus burden and performance in patients in a markedly thrombogenic state. To reduce the local thrombus burden in the culprit artery, manual thrombectomy (MT) has been widely used during PCI to reduce thrombus load, prevent distal embolization, and improve final myocardial perfusion.3,4 Despite its initial widespread adoption, routine use of MT in all patients undergoing PCI is no longer recommended, as randomized clinical trials have not demonstrated consistent clinical benefit.3-7

MT should be reserved for patients in whom it is most likely to provide benefit. To optimize the efficacy of PCI, the American8 and European9 clinical practice guidelines recommend MT in high-risk patients with a moderate-to-high thrombus burden who present with short ischemia times. Currently, however, there are no clearly defined criteria to precisely identify patients or thrombotic lesions that would derive the greatest benefit from MT.

The aim of our study was to evaluate the results of MT performed with the Hunter catheter (IHT–Iberhospitex SA, Barcelona, Spain), which has a high extraction capacity, in selected patients with STEMI undergoing PCI, and analyze the angiographic patterns associated with successful MT in our center.

METHODS

Study design and population

The Hunted registry is a single-center, observational, retrospective study. We included all patients diagnosed with STEMI who underwent PCI and in whom MT was performed using the Hunter thrombus aspiration catheter. This device was the first-choice catheter for MT in our center during the study period. The decision to perform MT was always left to the discretion of the operator performing the PCI, following homogeneous criteria among operators, subjectively based on angiographical evidence of a large angiographically visible thrombus. MT was not recommended in coronary vessels with a diameter < 2 mm or for the extraction of chronic thrombi or atherosclerotic plaques. The study period ranged from July 2020 through February 2022. Patients in whom MT was performed using a catheter other than the Hunter device were excluded.

The primary objective of the study was to evaluate the success of thrombus aspiration during PCI in patients with STEMI. Effective MT was defined as an angiographical reduction in thrombus burden, achieving a TIMI thrombus grade ≤ 2 (thrombus dimension < 50% of the vessel diameter). Moreover, angiographic factors associated with effective MT were assessed.

Secondary objectives included describing the clinical and angiographic characteristics of the patients and evaluating major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) during hospitalization and follow-up.

MACE were defined as a composite endpoint of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular death, stroke, and acute myocardial infarction. Two follow-up time points were established at 1 and 2 years after PCI. Total ischemia time was defined as the interval, in minutes, between symptom onset and reperfusion, defined as passage of the intracoronary guidewire, in accordance with clinical practice guidelines.

Thrombus burden was graded according to the TIMI thrombus scale,10 which includes 5 grades: grade 1, possible thrombus; grade 2, thrombus dimension < 50% of the vessel diameter; grade 3, thrombus dimension 0.5 to 2.0 vessel diameters; grade 4, thrombus dimension > 2.0 vessel diameters; and grade 5, total vessel occlusion by thrombus. Grades 4 and 5 were considered high thrombus burden.

Successful PCI was defined as achievement of TIMI grade 3 flow with residual percent diameter stenosis < 20%, without device-related complications or intraoperative MACE. For study purposes, patients were categorized into 2 groups according to whether MT was effective or not. Furthermore, these groups were compared to identify angiographic parameters that could predict MT success.

Data for the variables included in the Hunted registry were collected using a dedicated electronic case report form. Retrospective angiographic analysis was performed exclusively by 3 operators. All measures were taken to ensure confidentiality and protection of patient health record information. The study protocol fully complied with international recommendations for clinical research outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the hospital Ethics and Research Committee.

Characteristics of the Hunter device and aspiration technique

The Hunter thrombus aspiration catheter is a 140 cm rapid-exchange aspiration catheter compatible with a 6-Fr guiding catheter. Its tip has a slightly conical, low-profile, atraumatic design. The effective distal aspiration area measures 0.95 mm2, and it can aspirate up to 1.92 mL per second, one of the highest capacities available. The distal segment is coated with a hydrophilic surface to facilitate device navigability.

The standard thrombectomy technique used in our center consisted of advancing the Hunter catheter to a segment proximal to the culprit lesion. Aspiration was always initiated proximal to the culprit lesion. The catheter was then slowly advanced across the lesion under continuous aspiration to reach the distal segment, while continuous filling of the syringe was observed. If filling stopped, the catheter was withdrawn until aspiration resumed or removed completely if aspiration could not be reestablished. Continuous aspiration until removal from the guiding catheter was mandatory, as was thorough subsequent flushing of the guiding catheter, to prevent embolization of residual thrombotic material.

All retrieved material from the catheter and aspiration syringe was subsequently filtered using the filters provided with the device packaging. The procedure was repeated as many times as deemed necessary by the operator until the desired reduction in thrombus burden was achieved.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and the quantitative ones as mean and standard deviation when normally distributed, and as median and interquartile range when distribution was nonnormal.

Qualitative variables were compared using the chi-square test, with odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) calculated. Quantitative ones were compared using the Student t test or nonparametric tests, as appropriate.

In univariate analysis, each variable was individually assessed for its association with effective MT. Variables showing a statistically significant association were included in the multivariate analysis. Multiple regression models were used to control for potential confounders and determine the independent effect of each variable on the outcome.

Survival curves were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival-related parameters were evaluated using Cox proportional hazards analysis. A 2-sided P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 15 (StataCorp, United States).

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 750 PCI were performed in patients diagnosed with STEMI. MT using the Hunter catheter was performed in 401 patients (53.47%). The clinical characteristics of the patients, STEMI features, and PCI are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of patients and procedural variables

| Clinical characteristics | (n = 401) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 62.38 ± 12.43 |

| Male sex | 319 (80) |

| Current/former smoker | 163 (40.65) / 35 (8.73) |

| Hypertension | 207 (51.62) |

| Dyslipidemia | 186 (46.38) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 86 (21.45) |

| Kidney failure | 7 (1.75) |

| Previous stroke | 16 (3.99) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 8 (2.00) |

| Previous AMI | 48 (11.97) |

| Previous PCI | 50 (12.47) |

| Prior CABG | 5 (1.25) |

| Infarct location | |

| Anterior | 166 (41.50) |

| Inferior | 207 (51.75) |

| Lateral | 27 (6.75) |

| Killip-Kimball classification | |

| I | 338 (84.71) |

| II | 18 (4.51) |

| III | 8 (2.01) |

| IV | 35 (8.77) |

| Procedural variables | |

| Radial access | 385 (96.01) |

| No. of diseased vessels* | |

| 1 | 233 (58.10) |

| 2 | 111 (27.68) |

| 3 | 57 (14.21) |

| Infarct-related artery | |

| Right coronary artery | 183 (45.64) |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 166 (41.40) |

| Left circumflex artery | 48 (11.97) |

| Venous graft | 1 (0.25) |

| Left main coronary artery | 3 (0.75) |

| No. of stents implanted | |

| 0 | 34 (8.47) |

| 1 | 288 (71.82) |

| 2 | 60 (14.96) |

| 3 | 19 (4.74) |

| Drug-eluting stent (n = 367) | 362 (98.64) |

| Total ischemic time | |

| < 90 min | 43 (10.72) |

| 91-180 min | 167 (41.65) |

| 181-270 min | 82 (20.45) |

| 271-360 min | 42 (10.47) |

| > 360 min | 67 (16.71) |

|

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. |

|

Angiographic analysis of the culprit lesion and flow in the infarct-related artery is shown in table 2. Initial TIMI grade flow in the infarct-related artery, prior to intracoronary guidewire passage was 0 in 83% of cases. A high thrombus burden was observed in 87.5% of patients, corresponding to TIMI thrombus grades 4 or 5; 53.4% had grade 5 and 34.2% had grade 4. Only 50 patients (12.5%) had a TIMI grade < 4 flow, defined as a low thrombus burden.

Table 2. Angiographic analysis of patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention and manual thrombectomy

| Angiographic variables | |

|---|---|

| Vessel diameter | 3.25 [3.00-3.50] |

| 2.0-2.5 mm | 61 (15.21) |

| 2.6-3.0 mm | 122 (30.42) |

| 3.1-3.5 mm | 124 (30.92) |

| 3.6-4.0 mm | 66 (16.46) |

| > 4.0 mm | 28 (6.98) |

| Lesion length, mm | 16 [15-20] |

| AHA/ACC lesion type | |

| B1 | 60 (14.96) |

| B2 | 161 (40.15) |

| C | 180 (44.89) |

| Thrombus burden grade (TIMI) | |

| 1 | 1 (0.25) |

| 2 | 5 (1.25) |

| 3 | 44 (10.97) |

| 4 | 137 (34.16) |

| 5 | 214 (53.37) |

| Pre-PCI IRA TIMI flow grade | |

| 0 | 332 (82.79) |

| 1 | 18 (4.49) |

| 2 | 24 (5.98) |

| 3 | 27 (6.74) |

| Post-PCI IRA TIMI flow grade | |

| 0 | 2 (0.50); |

| 1 | 3 (0.75); |

| 2 | 10 (2.49); |

| 3 | 386 (96.26) |

|

AHA/ACC, American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology; IRA, infarct-related artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

|

According to the predefined criteria, effective MT was achieved in 327 of 401 patients (81.5%). Thrombectomy was considered ineffective in the 6 patients who had initial TIMI thrombus grades 1 and 2. Final post-PCI coronary flow was TIMI grade < 3 flow in 15 patients (3.74%). Overall, the PCI was successful in approximately 97% of cases. Device-related complications were recorded in 17 patients (4.24%): severe arrhythmias (ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia) occurring during reperfusion in 10 patients; severe no-reflow due to distal thrombus migration that could not be successfully treated in 4 patients; and coronary dissection after passage of the MT catheter, which was successfully treated with stenting in 3 patients. There were no cases of perioperative stroke due to migration of aspirated thrombus.

Comparative analysis of angiographic factors and ischemia time between patients with effective and noneffective MT is shown in table 3. MT was effective more frequently in patients with culprit coronary vessels > 3 mm in diameter (112 [34%] vs 12 mm [16%]; P < .001) and in those with a TIMI grade ≥ 4 thrombus burden (297 [91%] vs 54 [73%]; P < .001). Among the 61 patients with vessels < 2.5 mm, MT was ineffective in 36 (59.01%) vs 38 of 340 patients (11.2%) with vessels > 2.5 mm (P < .001). There were no statistically significant differences in ischemia time in relation to MT success.

Table 3. Comparison of angiographic and procedural characteristics between patients with effective and noneffective manual thrombectomy

| Procedural variables | Effective MT (n = 327) | Noneffective MT (n = 74) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infarct-related artery | .008 | ||

| Right coronary artery | 153 (46.79) | 30 (40.54) | |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 140 (42.81) | 26 (35.14) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 30 (9.17) | 18 (24.32) | |

| Saphenous vein graft | 1 (0.31) | – | |

| Left main coronary artery | 3 (0.92) | – | |

| AHA/ACC classification of the culprit lesion | .004 | ||

| B1 | 51 (15.60) | 9 (12.16) | |

| B2 | 142 (43.42) | 19 (25.68) | |

| C | 134 (40.98) | 46 (62.16) | |

| Reference diameter of the culprit lesion | < .001 | ||

| 2.0 mm-2.5 mm | 25 (7.65) | 36 (48.69) | |

| 2.6 mm-3.0 mm | 101 (30.89) | 21 (28.38) | |

| 3.1 mm-3.5 mm | 112 (34.25) | 12 (16.22) | |

| 3.6 mm-4.0 mm | 64 (19.57) | 2 (2.70) | |

| > 4.0 mm | 25 (7.64) | 3 (4.10) | |

| Thrombus burden grade (TIMI) | < .001 | ||

| Low thrombus burden (TIMI < 4) | 30 (9.18) | 20 (27.03) | |

| High thrombus burden (TIMI ≥ 4) | 297 (90.82) | 54 (72.97) | |

| Pre-PCI TIMI grade flow | .031 | ||

| TIMI grade 0-1 flow | 291 (88.99) | 59 (79.73) | |

| TIMI grade 2-3 flow | 36 (11.01) | 15 (20.27) | |

| Post-PCI TIMI grade flow | .61 | ||

| TIMI grade 0-1 flow | 2 (0.61) | 3 (4.05) | |

| TIMI grade 2 flow | 8 (2.45) | 1 (1.35) | |

| TIMI grade 3 flow | 317 (96.94) | 70 (94.59) | |

| Time from symptom onset to reperfusion | .79 | ||

| ≤ 90 min | 37 (11.31) | 6 (8.11) | |

| 91-180 min | 139 (42.51) | 28 (37.84) | |

| 181-270 min | 68 (20.80) | 14 (18.92) | |

| 271-360 min | 33 (10.09) | 9 (12.16) | |

| > 360 min | 50 (15.29) | 17 (22.97) | |

| Final procedural success | 317 (96.94) | 70 (94.59) | .61 |

|

AHA/ACC, American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology; MT, manual thrombectomy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

|||

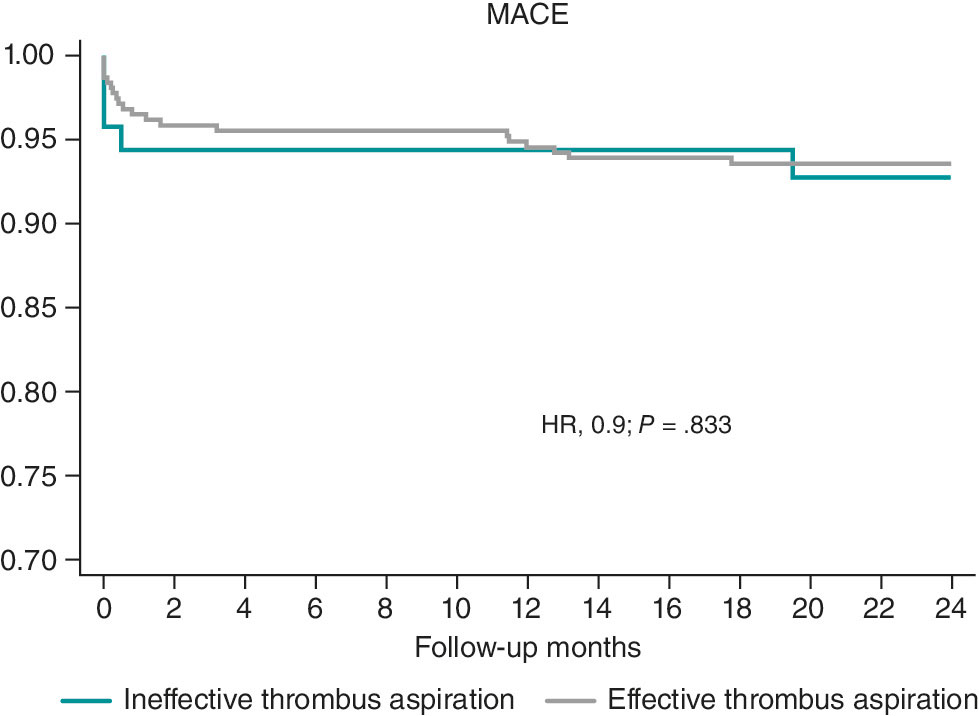

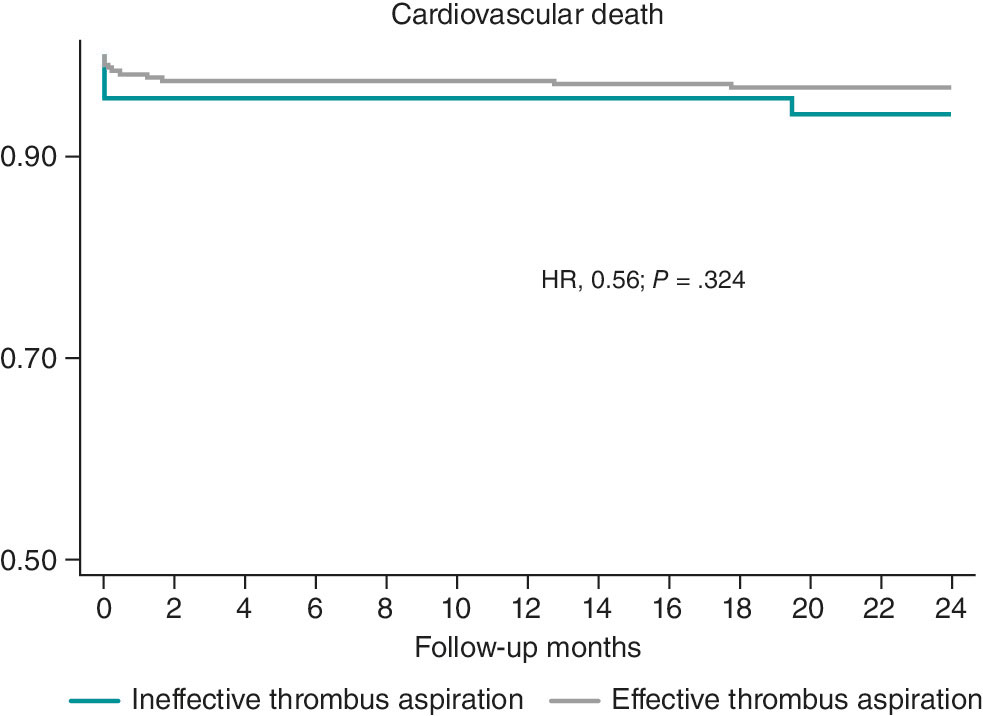

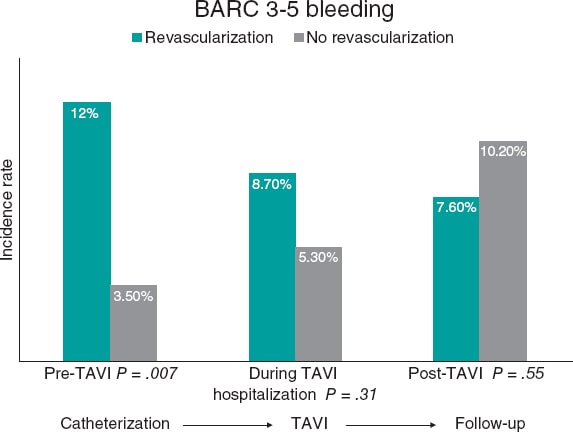

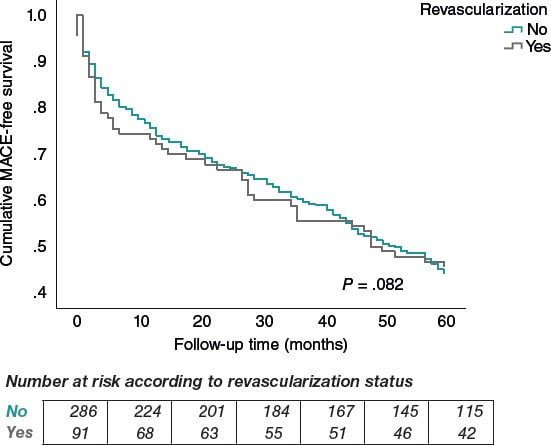

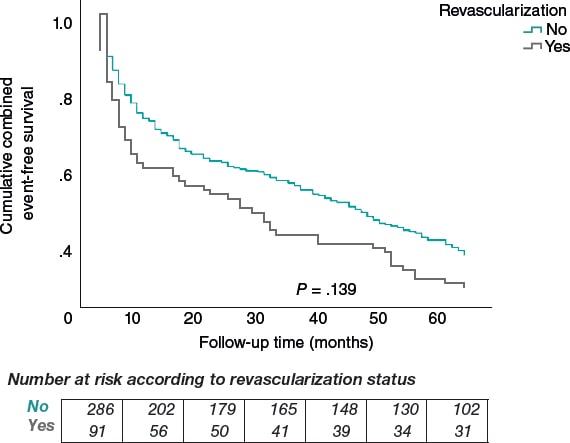

The 1- and 2-year follow-up was completed in 100% of included patients. MACE occurred in 32 patients (7.98%) at 30 days, 36 patients (8.98%) at 1 year, and 40 patients (9.97%) at 2 years (table 4). Kaplan–Meier curves for event-free survival during follow-up and cardiovascular death according to effective vs noneffective MT are shown in figure 1 and figure 2, respectively. Individual components of MACE at 1 year are shown in figure 3.

Table 4. Incidence rate of the composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events during follow-up

| Cardiovascular events at follow-up | n (%) |

|---|---|

| At 30 days | 32 (7.98) |

| At 1 year | 36 (8.98) |

| At 2 years | 40 (9.97) |

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curves for survival free from major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE). HR, hazard ratio.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier survival curves for cardiovascular death. HR, hazard ratio.

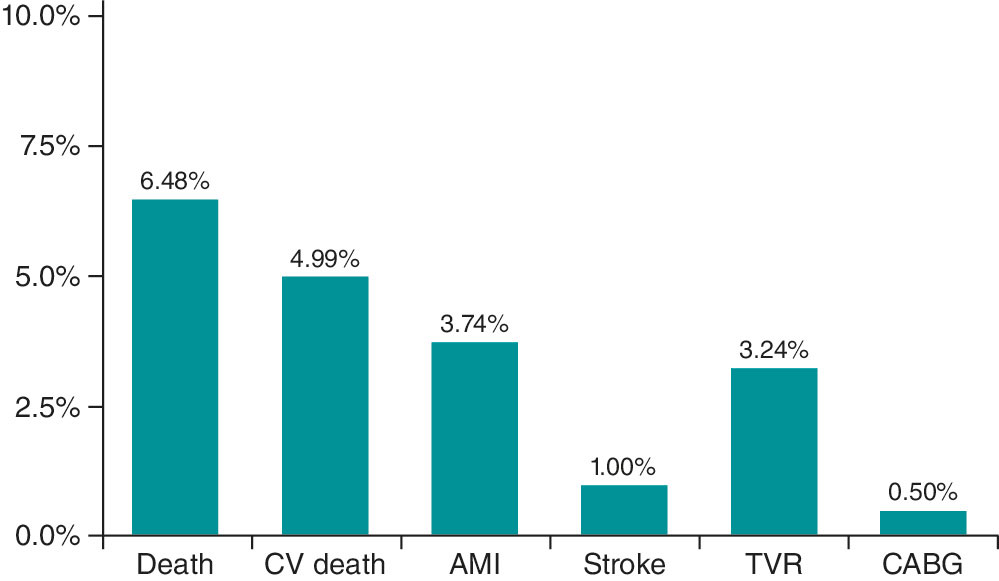

Figure 3. Individual components of major adverse cardiovascular events at the 1-year follow-up. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CV, cardiovascular; TVR, target vessel revascularization.

DISCUSSION

In selected patients, MT using the Hunter catheter is a safe and effective strategy to reduce angiographically assessed thrombus burden during PCI.

Current clinical practice guidelines do not recommend routine MT during PCI but suggest considering it in patients with a high thrombus burden, based on individual assessment and operator experience.8,9 In our series, MT was performed in 53.5% of patients with STEMI treated with PCI, a higher proportion than reported in other countries.11-13 Only 12% of patients undergoing MT did not have a TIMI grade 4–5 thrombus burden on angiographic analysis.

In this selected population with high thrombus burden, 88% had TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow, which is similar to the 79% observed in the TOTAL trial,14 with favorable results in both cases. In contrast, only 33% of patients from the TASTE trial7 had a high thrombus burden.

A high thrombus burden appears to be a key determinant of achieving effective MT and may be associated with better clinical outcomes. In our cohort, although effective MT was achieved in 82% of cases, it was not significantly correlated with final procedural success (97% vs 95%; P = .67), likely due to the small sample size of the 2 groups. MT efficacy was higher in vessels with high thrombus burdens (TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow; P < .001), which is consistent with a meta-analysis showing less cardiovascular death in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI with MT in the high thrombus burden subgroup vs PCI alone (2.5% vs 3.2%; hazard ratio [HR], 0.81; 95%CI, 0.65–0.98; P = .03).15 These findings reinforce the concept that appropriate patient selection is crucial to benefit from MT. Moreover, the same meta-analysis reported a higher risk of stroke (0.9% vs 0.5% in the PCI-alone group),15 a complication that may be related to the TM technique used.

Strict adherence to proper technique is essential to minimize complications and maximize success. In our series, emphasis was placed on following a standardized and rigorous technique, as described in the Methods section, resulting in a low complication rate (4.3%). Many of these complications were not directly related to MT per se but rather to reperfusion, such as ventricular arrhythmias. MT-related stroke is a potential complication; in the TOTAL trial,16 the stroke rate was 0.7%, twice that observed in the PCI-alone group, whereas in the large real-world SCAAR registry, there was no increase in the incidence rate of stroke across the groups,17 which are findings more consistent with our results and possibly related to differences in MT technique.

To identify angiographic predictors of MT success, we compared the characteristics of patients with effective and noneffective MT. The former had significantly larger culprit vessel diameters; 48% of patients with noneffective MT had vessels measuring 2.5 mm. Although MT is generally discouraged in vessels < 2 mm, larger vessels may harbor greater thrombus burden and thus derive greater benefit from MT with the Hunter catheter, which has demonstrated higher in vitro aspiration capacity compared with other devices. Therefore, vessel size is a critical differentiating factor: in vessels < 2.5 mm, MT was ineffective in 59% of cases, a significantly higher proportion than the 11.2% of noneffective MT observed in larger vessels. The other major difference between groups was thrombus burden, as effective MT was achieved more frequently in patients with higher thrombus loads (TIMI grade ≥ 3 flow).15 Furthermore, this factor represents a major difference among randomized clinical trials, in which the proportion of patients with high thrombus burden varied substantially.15 More complex lesions, such as American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology type C lesions, those associated with calcification in addition to thrombus, long lesions, and left circumflex artery lesions were associated with higher rates of noneffective MT. These differences should be considered when selecting appropriate candidates for MT with the Hunter catheter, favoring patients with vessel diameters > 2.5 mm, abundant thrombus burden (TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow), and culprit arteries other than the left circumflex one.

Studies have shown that total ischemia time, which we believe may determine differences in thrombus composition,18 may influence the efficacy of thrombus aspiration.19 In our series, there were no differences between the effective and noneffective MT groups with respect to infarction duration.

When assessing whether effective MT impacted the outcome of the PCI, slightly different procedural success rates were observed: 97% for effective MT vs 95% for noneffective MT (P = .61). Statistical significance was not reached, possibly due to the small sample size. Only 4 patients experienced no-reflow that could not be resolved, with no differences across groups and without demonstrating that MT could prevent distal embolization, as suggested in former studies.17-19

Short- and long-term clinical outcomes in patients with STEMI who required MT were favorable, with a low 1-year cardiovascular death rate of 3.5%, comparable to that reported in randomized clinical trials. In the TASTE trial,7 the 30-day mortality rate was 2.4% in the MT group and 2.9% in the PCI-alone group (HR, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.70–1.01; P = .06). In the TAPAS trial,20 the 30-day all-cause mortality rate was 2.1% in the MT group vs 4.0% in the conventional PCI group, reaching statistical significance at the 1-year follow-up (P = .07). Large registries have reported mortality rates similar to those observed in our series, with 2.8% vs 3.0% in the Swedish registry21 and comparable findings in the Japanese registry.22 The overall mortality rate observed in a meta-analysis with aggregated data from published MT studies was 3.7%.15 When selecting patients with a high thrombus burden (TIMI grade ≥ 3 flow in the meta-analysis subgroup), the cardiovascular death rate was 2.5% (170 of 6872 patients) in the MT group vs 3.1% (205 of 6599 patients) in the PCI-alone group (HR, 0.8; 95%CI, 0.65–0.98; P = .03).15 Proper selection of this subgroup of patients with a high thrombus burden is, therefore, crucial to maximize the therapeutic benefit.

Limitations

As a single-center, observational, retrospective registry, this study has inherent limitations related to its design. First, because it reflects the experience of a single center—albeit with more than 15 years of experience in PCI—operator homogeneity may limit extrapolation of the results. The decision to perform MT was always left to the discretion of the operator, and no control group without MT was available for patient comparison. Because of the retrospective design of the analysis, we could not determine the cause of ineffective MT in all patients, which is why this variable could not be included in the analysis. This study should not be interpreted as an evaluation of thrombus aspiration in general, but rather as an assessment of outcomes in a selected population treated with the Hunter device; these selection criteria represent the primary contribution of this work to current scientific knowledge. The study did not incorporate systematic criteria to address sex- and gender-related variables during methodological development or result analysis. Although angiographic analysis was not performed by an independent core laboratory, it was conducted by 3 experienced analysts. In this analysis, MT success, procedural success, and baseline thrombus burden were defined using the TIMI scale.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with STEMI undergoing PCI, selective use of MT with the Hunter catheter in cases with high thrombus burden (TIMI grade ≥ 4 flow), non-circumflex culprit vessels, and vessel diameters > 2.5 mm is a safe and effective strategy associated with a low complication rate. Further studies are needed to assess the impact of this strategy on PCI outcomes, MACE, and stroke.

FUNDING

This project was supported by IHT-Iberhospitex S.A. (Lliçà de Vall, Barcelona, Spain). As sponsor, the company collaborated in the study design but had no role in data collection, analysis, or interpretation. Manuscript preparation and the decision to submit for publication were entirely independent of the sponsor and performed by the research team.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was approved by Hospital Universitari Germans Trias i Pujol Ethics Committee (Barcelona, Spain) (CEIC code: PI-22-281) and conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. SAGER guidelines were not applied to address gender bias.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

D.G. Borraz-Noriega: angiographic analysis, data review, and manuscript drafting. J.F. Andrés-Cordón: angiographic analysis, data review, and statistical analysis. E. Cañedo: data collection and clinical follow-up. F. Panchano-Castro: angiographic analysis and data review. M. Trichilo: data collection and clinical follow-up. V. Vilalta: data collection and critical manuscript review. O. Rodríguez-Leor: data collection and critical manuscript review. E. Fernández-Nofrerias: critical manuscript review. I. Santos-Pardo: critical manuscript review. X. Carrillo: study design, overall supervision, and manuscript drafting. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

- Routine use of manual thrombectomy has not demonstrated clear benefit. Current clinical practice guidelines recommend individualized use in selected patients with high thrombus burden. Clear angiographic criteria for identifying patients most likely to benefit from thrombectomy are lacking.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The Hunted registry provides specific evidence on thrombectomy performed with the Hunter catheter during PCI.

- It identifies angiographic predictors of thrombectomy success (vessel diameter > 2.5 mm, TIMI ≥ 4 thrombus burden, non-circumflex coronary arteries).

- The Hunter catheter, with its larger effective aspiration area, along with proper technique, demonstrates a low complication rate and favorable clinical outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL, et al. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13-20.

2. Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R, et al. Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, Phase I: A comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation. 1987;76:142-154.

3. Moens AL, Claeys MJ, Timmermans JP, et al. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-injury, a clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Int J Cardiol. 2005;100:179-190.

4. Bhindi R, Kajander OA, Jolly SS, et al. Culprit lesion thrombus burden after manual thrombectomy or percutaneous coronary intervention-alone in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: the OTC sub-study of the TOTAL trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1892-1900.

5. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) Investigators. Manual thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Impact of total ischemic time. J Cardiol. 2016;27:753-758.

6. Vlaar PJ, Svilaas T, van der Horst IC, et al. Cardiac death and reinfarction after 1 year in the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS): a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1915-1920.

7. Lagerqvist B, Fröbert O, Olivecrona GK, et al. Outcomes 1 Year after Thrombus Aspiration for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1111-1120.

8. Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI Focused Update on Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients with ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: An Update of the 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI and the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1235-1250.

9. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177.

10. Sianos G, Papafaklis MI, Serruys PW. Angiographic thrombus burden classification in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010;22:6B-14B.

11. Freixa X, Jurado-Román A, Cid B, et al. Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry. 31st official report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2021). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2022;75:1040-1049.

12. Kimura K, Kimura T, Ishihisa M, et al. JCS 2018 Guideline on diagnosis and treatment of acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2019;83:1085-1196.

13. Qu Y-Y, Zhang X-G, Ju C-W, et al. Age-Related Utilization of Thrombus Aspiration in Patients with ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Findings From the Improving Care for Cardiovascular Disease in China Project. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:791007.

14. Svilaas T, Vlaar PJ, van der Horst IC, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:557-567.

15. Jolly SS, James S, Džavík V, et al. Thrombus Aspiration in ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction, An Individual Patient Meta-Analysis: Thrombectomy Trialists Collaboration. Circulation. 2017;135:143-152.

16. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1389-1398.

17. Angeras O, Haraldsson I, Redfors B, et al. Impact of Thrombus Aspiration on Mortality, Stent Thrombosis, and Stroke in Patients with ST-Segment–Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report From the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007680.

18. Carol A, Bernet M, Curós A, et al. Thrombus age, clinical presentation, and reperfusion grade in myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2014;23:126-130.

19. Sim DS, Jeong MH, Ahn Y, et al. Manual thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention: Impact of total ischemic time. J Cardiol. 2017;69:428-435.

20. Vlaar PJ, Svilaas T, van der Horst IC, et al. Cardiac death and reinfarction after 1 year in the Thrombus Aspiration during Percutaneous coronary intervention in Acute myocardial infarction Study (TAPAS): a 1-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008;371:1915-1920.

21. Fröbert, O, Lagerqvist B, Olivecrona GK, et al. Thrombus aspiration during ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1587-1597.

22. Inohara T, Kohsaka S, Yamaji K, et al. Use of Thrombus Aspiration for Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: Insights from the Nationwide J-PCI Registry. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025728.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Although acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains a leading cause of death in Mexico, the impact of out-of-hours presentation on mortality remains understudied. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between out-of-hours admissions (nights, weekends, holidays) and 30-day mortality in patients with AMI in Mexican hospitals, with a focus on the role of catheterization laboratories (cath lab).

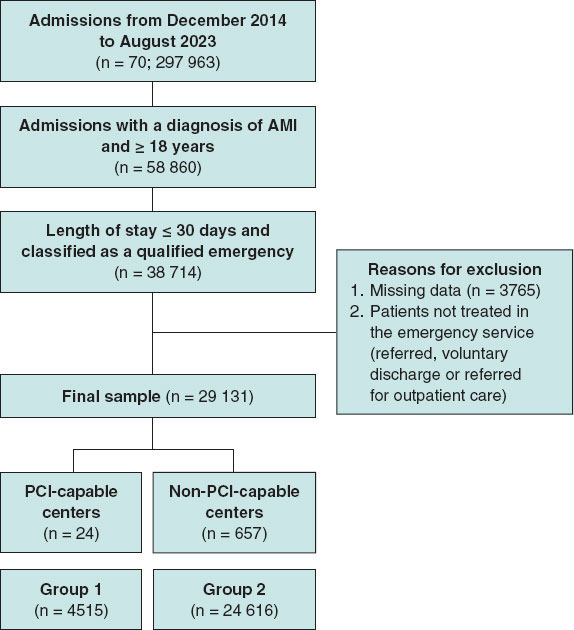

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study to analyze emergency admissions from December 2014 through August 2023. Admissions were classified as out-of-hours or during-hours and were stratified by hospital type (with or without cath lab). Cox regression models adjusted for sociodemographic, health, and temporal variables were used to analyze mortality risks.

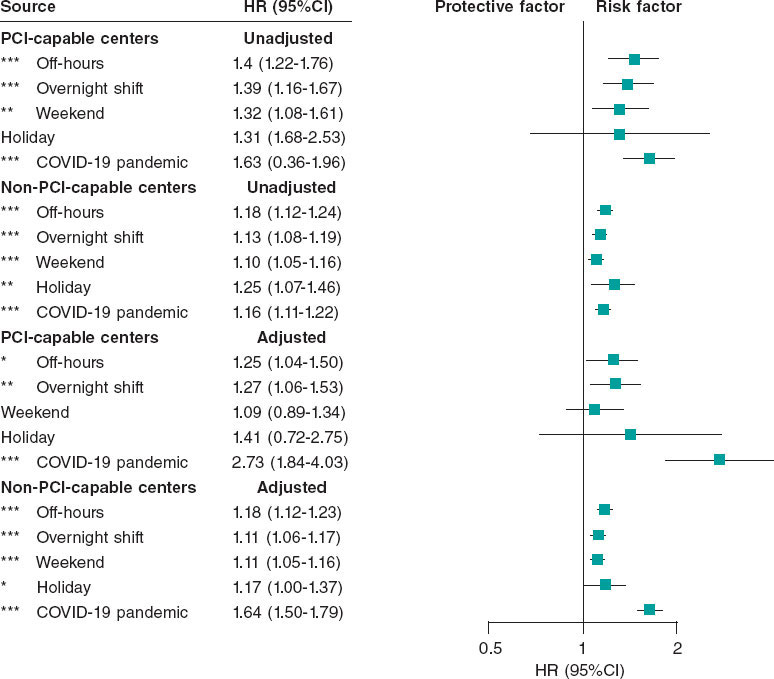

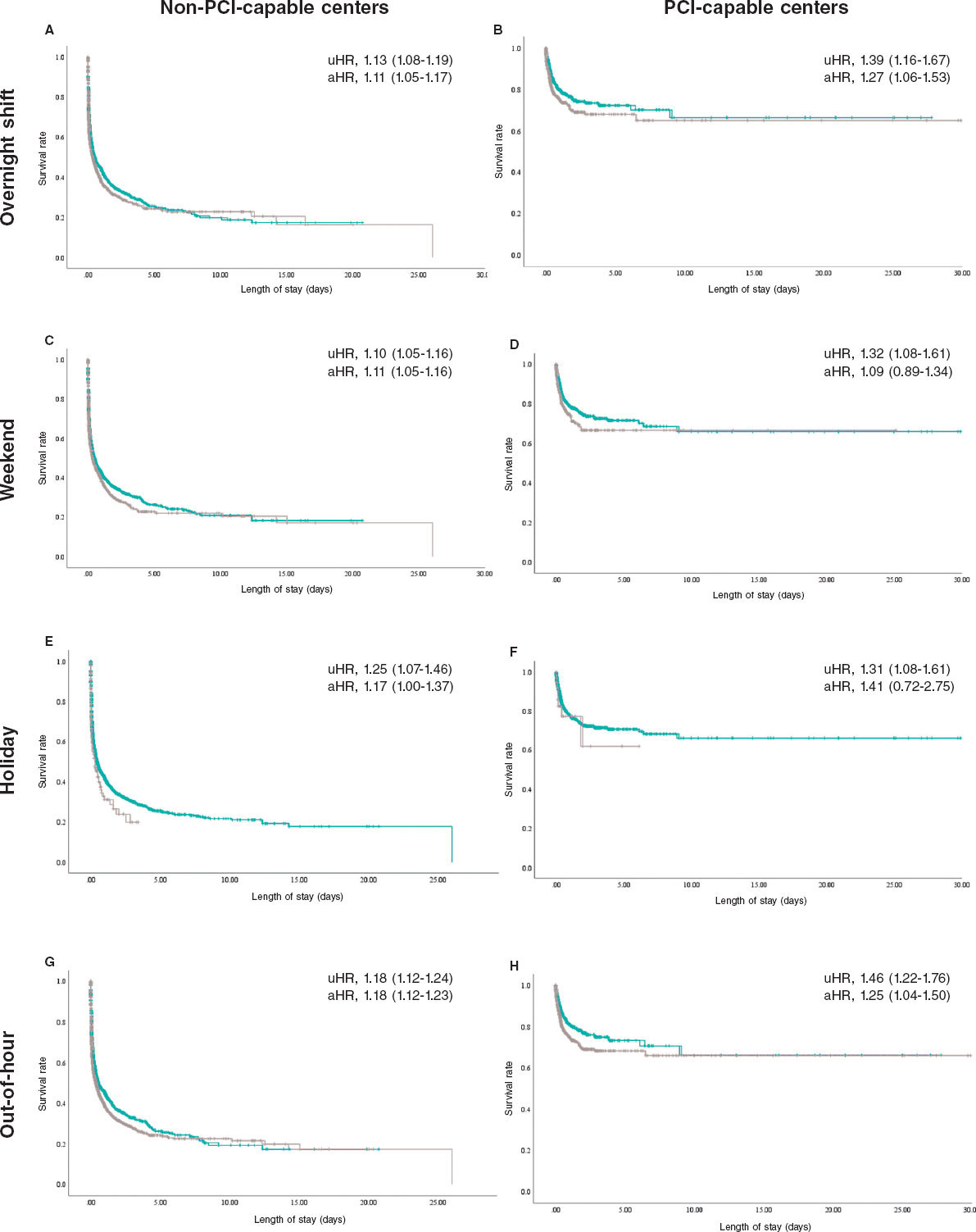

Results: The study included a total of 29 131 cases: 4515 in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-capable centers (group 1) and 24 616 in non-PCI-capable centers (group 2). Admissions outside regular hours accounted for 46.7% in group 1 and 53.6% in group 2. Adjusted analysis showed that although the presence of a cath lab was protective (HR, 0.25; 95%CI, 0.23-0.28), admissions outside regular hours increased the risk of mortality in both groups (group 1: HR, 1.25; 95%CI, 1.04-1.50; group 2: HR, 1.16; 95%CI, 1.11-1.22). Although overnight shifts increased the risk of death in both groups, weekends and holidays increased such risk only in non-PCI-capable centers.

Conclusions: Out-of-hours admissions were associated with higher mortality, and unlike in developed countries, the presence of a cath lab did not improve out-of-hours outcomes.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction. Out-of-hours. Mexico.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El infarto agudo de miocardio (IAM) sigue siendo una causa principal de muerte en México, pero el impacto de su presentación fuera de horario sobre la mortalidad está poco investigado. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la asociación entre las admisiones fuera de horario (noches, fines de semana y festivos) y la mortalidad a 30 días en pacientes con IAM en hospitales mexicanos, con énfasis en el papel de las salas de hemodinámica (SH).

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo que analizó las admisiones en urgencias desde diciembre de 2014 hasta agosto de 2023. Las admisiones se clasificaron como fuera o dentro de horario, y se estratificaron según el tipo de hospital (con o sin SH). Se emplearon modelos de regresión de Cox ajustados por variables sociodemográficas, de salud y temporales para analizar el riesgo de mortalidad.

Resultados: El estudio incluyó 29.131 casos: 4.515 en hospitales con SH (grupo 1) y 24.616 en hospitales sin esta infraestructura (grupo 2). Las admisiones fuera de horario representaron el 46,7% en el grupo 1 y el 53,6% en el grupo 2. El análisis ajustado mostró que, aunque la presencia de una SH fue protectora (HR = 0,25; IC95%, 0,23-0,28), las admisiones fuera de horario aumentaron el riesgo de mortalidad en ambos grupos (grupo 1: HR = 1.25; IC95%, 1,04-1,50; grupo 2: HR = 1,16; IC95%, 1,11-1,22). Los turnos nocturnos también incrementaron el riesgo de muerte en ambos grupos, pero los fines de semana y festivos solo lo hicieron en los hospitales sin SH.

Conclusiones: Las admisiones fuera de horario se asociaron con mayor mortalidad y, a diferencia de los países desarrollados, la presencia de una SH no mejoró los resultados fuera de horario.

Palabras clave: Infarto agudo de miocardio. Fuera de horario. México.

Abbreviations

AMI: acute myocardial infarction. Cath lab: catetherization laboratory. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION