To the Editor,

Premature coronary artery disease (CAD) affects 7%-10% of patients younger than 55 years, leading to reduced quality of life and a significant risk of adverse events.1

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with drug-eluting stents (DES), the standard treatment for this populations, is associated with a 7.3% rate of failure at the 3-year follow-up.2 The use of drug-coated balloons (DCB) eliminates the need for permanent stent strut deployment, offering potential advantages to patients with premature CAD.3 However, the clinical efficacy of DCB angioplasty in premature CAD remains underexplored.

The aim of this study was to compare the efficacy of DCB angioplasty in patients aged < 55 and ≥ 55 years undergoing PCI with sirolimus-coated balloon (SCB).

EASTBOURNE (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT03085823) is a prospective, multicenter, investigator-initiated study that included consecutive patients who underwent PCI with the MagicTouch SCB (Concept Medical, United States) at 38 European and Asian centers from 2016 through 2020. Exclusion criteria were unsuccessful target lesion predilation with persistent residual percent diameter stenosis > 50%, highly tortuous target vessel, severe target vessel calcifications, and high thrombus burden in the target lesion, not amenable to treatment with manual aspiration.4 PCI was performed following the recommendations of the DCB Consensus Group.3 The primary endpoint was 2-year clinically indicated target lesion revascularization (TLR), defined as target lesion reintervention after demonstrating at least 70% narrowing and objective evidence of ischemia, as confirmed by stress testing or functional assessment. Secondary endpoints included non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel MI, all-cause mortality, and cardiac death at 2 years. All angiographic data were analyzed by quantitative coronary angiography by 2 independent, experienced operators. A dedicated and independent committee assessed all reported events. The study, conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the ethics committee of the coordinating center (ASST FBF-Sacco, Milan: Comitato Etico Area B Milano, Italy), and all participating centers. All patients signed the informed consent form prior to being included in the study. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test, and the continuous ones were analyzed using the Student t test. Propensity score matching was used to adjust for clinical confounders, with successful matching defined by standardized mean differences < 0.1 for all covariates, indicating adequate balance (figure 1 of the supplementary data). All statistical tests were 2-tailed, and a P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.0.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

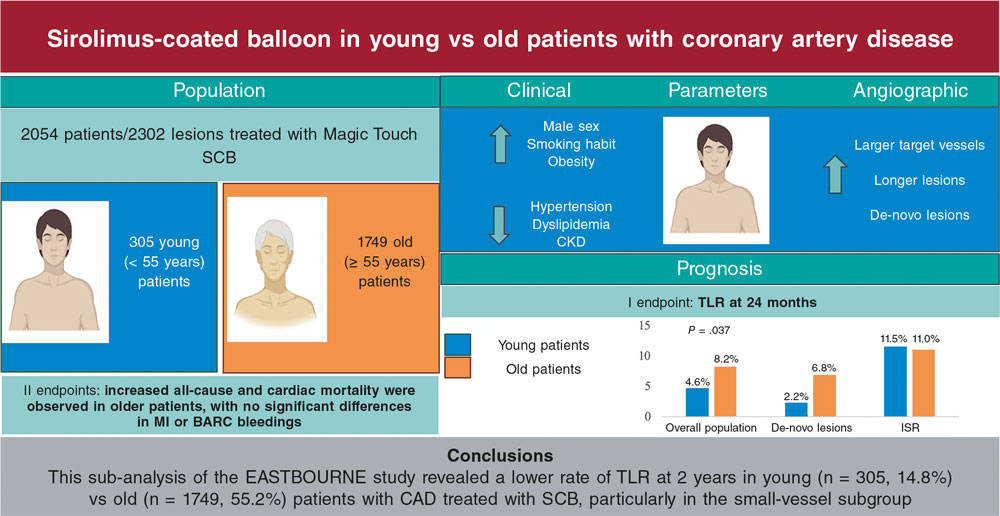

Figure 1. Main findings of the study. BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; ISR, in-stent restenosis; MI, myocardial infarction; SCB, sirolimus-coated balloon; TLR, target lesion revascularization.

A total of 2054 patients were included in the analysis. Patients aged < 55 years (n = 305 [14.8%]) were more likely to be men (272 [89.2%] vs 1394 [79.7%]; P < .001), smokers (132 [43.3%] vs 399 [22.8%]; P < .001) and had a higher prevalence of obesity (88 [28.9%] vs 327 [18.7%]; P < .001), while those aged ≥ 55 years (n = 1749 [85.2%]) had a higher rate of hypertension (1421 [81.2%] vs 159 [52.1%]; P < .001), dyslipidemia (1283 [73.4%] vs 202 [66.2%]; P = .013) and chronic kidney disease (200 [11.4%] vs 13 [4.3%]; P < .001) (table 1). A total of 2302 lesions (339 in the young patient group, 1963 in the old patient group) were considered for the analysis. Patients aged < 55 years exhibited smaller target vessel diameters (2.50 mm ± 0.54 vs 2.67 ± 0.59; P < .001), longer lesions (19.81 mm ± 9.04 vs 18.63 ± 9.16; P = .004) and a higher prevalence of de-novo lesions (254 [74.9%] vs 1024 [52.2%]; P < .001) vs those aged ≥ 55 years. Furthermore, SCB were longer (24.75 mm ± 10.17 mm vs 22.93 ± 8.57; P = .002), had a higher diameter (2.58 mm ± 1.34 mm vs 2.68 ± 0.59; P < .001) and were inflated at lower pressures (9.03 atm ± 3.43 atm vs 10.12 ± 3.80; P < .001) in patients younger than 55 years (table 1 of the supplementary data).

Table 1. Baseline clinical features in the overall population and in the 2 study groups

| Characteristics | Study population (n = 2054) | Patients aged < 55 years (n = 305) | Patients aged ≥ 55 years (n = 1749) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 66.61 ± 11.14 | 48.67 ± 5.19 | 69.73 ± 8.67 | < .001 |

| Male sex | 1666 (81.1) | 272 (89.2) | 1394 (79.7) | < .001 |

| Hypertension | 1580 (76.9) | 159 (52.1) | 1421 (81.2) | < .001 |

| Obesity | 415 (20.2) | 88 (28.9) | 327 (18.7) | < .001 |

| Diabetes | 856 (41.7) | 94 (30.8) | 762 (43.6) | < .001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1485 (72.3) | 202 (66.2) | 1283 (73.4) | .013 |

| Smoking habit | 531 (25.9) | 132 (43.3) | 399 (22.8) | < .001 |

| Family history of CAD | 468 (22.8) | 77 (25.2) | 391 (22.4) | .300 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 213 (10.4) | 13 (4.3) | 200 (11.4) | < .001 |

| Heart failure | 166 (8.1) | 15 (4.9) | 151 (8.6) | .037 |

| Previous stroke | 93 (4.5) | 7 (2.3) | 86 (4.9) | .060 |

| PAD | 856 (41.7) | 94 (30.8) | 762 (43.6) | < .001 |

| Previous MI | 881 (42.9) | 139 (45.6) | 742 (42.4) | .336 |

| Previous PCI | 1360 (66.2) | 150 (49.2) | 1210 (69.2) | < .001 |

| Previous CABG | 241 (11.7) | 13 (4.3) | 228 (13.0) | < .001 |

| LVEF | 52.49 ± 9.33 | 52.93 ± 9.05 | 52.41 ± 9.38 | .473 |

| Clinical presentation | .684 | |||

| CCS | 1106 (53.8) | 168 (55.1) | 938 (53.6) | |

| Unstable angina | 355 (17.3) | 49 (16.1) | 306 (17.5) | |

| NSTEMI | 436 (21.2) | 48 (15.7) | 388 (22.2) | |

| STEMI | 157 (7.6) | 40 (13.1) | 117 (6.7) | |

|

CAD, coronary artery disease; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

||||

At the 2-year follow-up, patients aged < 55 years experienced a lower rate of TLR (14 [4.6%] vs 144 [8.2%]; P = .037), all-cause mortality (2 [0.7%] vs 98 [5.6%]; P < .001) and cardiac death (0 [0.0%] vs 32 [1.8%]; P = .033) vs the other group (figure 1). There were no significant differences for the other endpoints between the 2 groups (table 2 of the supplementary data). When analyzing different subgroups, a lower rate of TLR was observed in patients aged < 55 years in the small-vessel (< 3 mm) CAD cohort (5 [2.2%] vs 77 [6.8%]; P = .006) (table 3 of the supplementary data), while no differences were observed in large-vessel CAD between the 2 groups (9 [11.5%] vs 67 [11.0%]; P = .849) (table 4 of the supplementary data). Finally, younger patients had a better prognosis vs patients aged ≥ 55 years after propensity score matching (table 5 of the supplementary data).

This subanalysis of the EASTBOURNE study assessed the clinical performance of the MagicTouch SCB based on patient age (< 55 and ≥ 55 years). Younger patients presented with a distinct clinical risk factor profile, characterized by higher rates of smoking and obesity, and a lower rate of other cardiovascular risk factors. Additionally, coronary artery lesions in patients aged < 55 years were longer and involved smaller vessels, with a similar distribution and complexity vs the other group. Importantly, patients aged < 55 years demonstrated a better prognosis vs old patients, with nearly half the risk of TLR at 2 years. This difference was particularly pronounced in the small-vessel CAD cohort, where younger patients experienced a significant threefold lower risk of TLR, and a sevenfold lower risk of MI vs older patients.

The overall rate of TLR was relatively low (4.6%) at 2 years in young patients with CAD treated with the MagicTouch SCB. This promising finding is consistent with a recent study by Yang et al.,2 which compared the prognosis of DCB and DES in young (≤ 45 years) patients with MI. The authors reported a numerically lower rate of TLR (3.0% vs 9.1%) in the DCB group at the 3-year follow-up vs those treated with DES.2

Of particular interest is the recent ANDROMEDA study (assessment of long-term clinical outcomes of de novo DCB performance: a comprehensive, individual patient data meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials), an individual patient data meta-analysis that demonstrated lower rates of major adverse cardiovascular events and target lesion failure with paclitaxel DCB vs DES, in patients with de novo small vessel CAD aged < 67 years.5 Previous evidence has shown that younger patients are at a higher risk of late stent thrombosis due to delayed vessel healing and higher rates of neo-atherosclerosis. From a mechanistic standpoint, DCBs could be beneficial for young patients with CAD by minimizing stent-related complications (such as in-stent restenosis and thrombosis), preventing long-term coronary inflammation, preserving endothelial function, and promoting positive vessel remodeling.6

In conclusion, this subanalysis of the EASTBOURNE study revealed a lower rate of TLR at 2 years in young vs old patients, particularly in the small-vessel CAD subgroup. These findings suggest that DCB could be a promising strategy regarding the revascularization of young patients. Of note, patients aged ≥ 55 years had a higher burden of risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, which may partly explain their worse prognosis.

This study is limited by its observational study design, the lack of a DES group for comparison purposes, and the fact that the decision to use SCB was left to the operator’s discretion, potentially introducing selection bias. Moreover, the large difference in sample size between the 2 groups and the low number of adverse events limits the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. Furthermore, paclitaxel DCBs, different in their antirestenotic mechanisms,6 were not investigated. Larger future studies are eagerly awaited to compare the clinical performance of DCB vs DES in young patients with CAD.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study, conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, was approved by the ethical committee of the coordinating center (ASST FBF-Sacco, Milano: Comitato Etico Area B Milano, Italy), and all participating centers. All patients signed the informed consent form prior to being included in the study. Sex and gender variables were considered in full compliance with the SAGER guidelines.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

F.L. Gurgoglione: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, and drafting process. A. Lelasi: critical review of significant intellectual content; data interpretation, and final approval. I. Bossi: substantial contributions to the study conception or design, and final approval. R. Latini: critical review of significant intellectual content, and final approval. B. Cortese: substantial contributions to the study conception or design, critical review of significant intellectual content, and final approval. All authors agreed to be made accountable for all aspects associated with this study, thus ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the study are appropriately investigated and resolved.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Khoja A, Andraweera PH, Lassi ZS, et al. Risk factors for premature coronary artery disease (PCAD) in adults:a systematic review protocol.

2. Yang YX, He KZ, Li JY, et al. Comparisons of Drug-Eluting Balloon versus Drug-Eluting Stent in the Treatment of Young Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction.

3. Fezzi S, Scheller B, Cortese B, et al. Definitions and standardized endpoints for the use of drug-coated balloon in coronary artery disease:consensus document of the Drug Coated Balloon Academic Research Consortium.

4. Leone PP, Heang TM, Yan LC, et al. Two-year outcomes of sirolimus-coated balloon angioplasty for coronary artery disease:the EASTBOURNE Registry.

5. Fezzi S, Giacoppo D, Fahrni G, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of paclitaxel-coated balloons vs drug-eluting stents for small-vessel coronary artery disease:the ANDROMEDA study.

6. Gurgoglione FL, De Gregorio M, Benatti G, et al. Paclitaxel-Coated Versus Sirolimus-Coated Eluting Balloons for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions:Pharmacodynamic Properties, Clinical Evidence, and Future Perspectives.