ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Thrombus removal in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) can be challenging in the presence of a large thrombus burden. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA) is an adjuvant device capable of vaporizing thrombus. This study aimed to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in PCI.

Methods: Patients with STEMI undergoing PCI with concomitant use of ELCA for thrombus removal were retrospectively identified at our center. Data were collected on the device efficacy and its contribution to overall procedural success. Additionally, ELCA-related complications and major adverse cardiovascular events were recorded at a 2-year follow-up.

Results: ELCA was used in 130 STEMI patients, 124 (95.4%) of whom had a large thrombus burden. TIMI grade flow improved significantly after ELCA: before laser application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases and TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%) cases. After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively (P < .001). Technical and procedural success were achieved in 128 (98.5%) and 124 (95.4%) cases, respectively. The complications included 1 death at the cath lab (0.8%), 1 coronary perforation (0.8%), and 3 distal embolizations (2.3%). At the 2-years follow-up, major adverse cardiovascular events occurred in 18.3% of the population.

Conclusions: In the context of STEMI, ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution, with adequate technical and procedural success rates. In the present cohort, ELCA use was associated with a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. Thrombectomy. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La eliminación de trombos durante la intervención coronaria percutánea primaria (ICPp) en el infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST) es un desafío en presencia de una carga trombótica elevada. La angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros (ELCA) es una técnica complementaria que permite vaporizar el trombo. Este estudio evaluó la eficacia y la seguridad de la ELCA en el contexto de la ICPp.

Métodos: Análisis retrospectivo unicéntrico de pacientes con IAMCEST sometidos a ICPp con ELCA. Se evaluaron la eficacia en la disolución del trombo, la mejoría del flujo, el éxito del procedimiento, las complicaciones asociadas y los acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores durante un seguimiento de 2 años.

Resultados: Se realizó ELCA en 130 pacientes con IAMCEST, de los cuales 124 (95,4%) tenían carga trombótica elevada. El flujo TIMI mejoró significativamente tras la ELCA: previamente era 0 en 79 casos (60,8%) y 1 en 32 casos (24,6%), y se lograron flujos TIMI 2 y 3 en 45 casos (34,6%) y 66 casos (50,8%), respectivamente (p < 0,001). Las tasas de éxito técnico y del procedimiento fueron del 98,5% y el 95,4%, respectivamente. Las complicaciones incluyeron 1 muerte intraprocedimiento (0,8%), 1 perforación coronaria (0,8%) y 3 embolizaciones distales (2,3%). A los 2 años, la tasa de acontecimientos cardiovasculares adversos mayores fue del 18,3%.

Conclusiones: La ELCA parece ser una técnica eficaz y segura en el IAMCEST para la disolución del trombo, con altas tasas de éxito técnico y procedimental, baja incidencia de complicaciones y resultados favorables a largo plazo.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. Trombectomía. Angioplastia coronaria con láser de excímeros.

Abbreviations

ELCA: excimer laser coronary angioplasty. LTB: large thrombus burden. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

INTRODUCTION

In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy, as long as it can be performed within 120 minutes of the electrocardiogram-based diagnosis.1 Many patients with STEMI present with thrombotic occlusion of the infarct-related artery. Therefore, the use of devices aimed at reducing thrombus burden is a reasonable consideration to minimize distal embolization and no-reflow. Persistent no-reflow in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI is associated with the worst in-hospital outcomes and increased long-term mortality.2

While early studies on manual thrombus aspiration suggested benefits in terms of improved myocardial blush grades and ST-segment elevation resolution,3 larger trials comparing manual thrombus aspiration with PCI alone showed no significant reduction in cardiovascular death, recurrent myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, or a New York Heart Association FC IV heart failure within 180 days.4 Consequently, routine aspiration thrombectomy is no longer recommended in patients with STEMI.5

Thrombus removal, particularly when dealing with a large thrombus burden (LTB) in the context of STEMI, remains a critical and sometimes challenging aspect of PCI. Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA Coronary Laser Atherectomy Catheter, Koninklijke Philips N.V., The Netherlands) is a well-established adjuvant therapy for coronary interventions. ELCA uses xenon-chloride gas as the lasing medium to produce UV light energy, which is delivered to the target site through an optical fiber. This energy has the ability to ablate inorganic material through photochemical, photothermal, and photomechanical mechanisms.6,7 The microparticles released during laser ablation measure < 10 µm and are absorbed by the reticuloendothelial system, theoretically reducing the risk of microvasculature obstruction.8 These unique characteristics of ELCA have facilitated its use as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI to ablate and remove thrombus.

Although ELCA is part of the therapeutic armamentarium in some PCI-capable centers, literature data is limited on its safety and efficacy profile in this specific scenario. The aim of this study was to evaluate the contribution of ELCA, focusing on its safety and efficacy profile as an adjuvant therapy in patients with STEMI undergoing PCI in our center.

METHODS

Data from all patients undergoing PCI with the simultaneous use of ELCA as an adjuvant technique were retrospectively recorded in a dedicated database after each procedure, starting from the introduction of the device in our center. ELCA procedures were performed by 5 interventional cardiologists with dedicated training in the use of the device.

This study was approved by Parque Sanitario Pere Virgili ethics committee (Barcelona, Spain) (reference No.: CEIM 003/2025). For the purposes of this study, we selected the subgroup of patients with STEMI who underwent PCI in which ELCA was used to facilitate thrombus removal.

Thrombus burden was assessed using the thrombus grading classification9 as defined by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) study group, ranging from 0 to 5. A LTB was defined as a thrombus score ≥ 3. According to our internal protocol, ELCA was considered in STEMI patients in the presence of angiographic evidence of LTB, defined as TIMI thrombus grade ≥ 3, particularly if TIMI grade-0–1 flow or, poor visualization of the distal vessel, or as a bailout strategy after unsuccessful manual thrombectomy. Clinical variables were meticulously refined, and follow-up details were obtained through a thorough review of the patients’ health records. Following coronary angiography and successful guidewire crossing of the culprit lesion, ELCA was left at the operator’s discretion. It was used either as a primary device for thrombus removal or as a bailout strategy when manual thrombus aspiration did not improve TIMI grade flow. The selection of catheter size was mainly based on the target vessel diameter and on the characteristics of the vessel and the lesion; a 0.9 mm ELCA catheter is usually used in tortuous anatomies due to its better navigability and in small-caliber vessels, whereas a 1.4 mm catheter is used in selected cases involving larger proximal vessels with straight segments. Catheter size (0.9 mm or 1.4 mm) was selected based on vessel diameter and lesion characteristics. Laser fluence (45-60 mJ/mm²) and pulse repetition rate (25-40 Hz) were chosen as per manufacturer’s recommendations.

Before laser application, the target vessel was flushed with saline solution to prevent interaction between the laser and blood or contrast medium. In all cases, continuous saline infusion was administered during laser delivery to avoid coronary artery wall heating. Laser energy was delivered using an ‘on-off’ technique, consisting of 10-s laser activation cycles interspersed with 5-s pauses. The laser catheter was advanced at a rate of approximately 1 mm/s over a 0.014-in coronary guidewire through the target lesion, following the manufacturer’s recommendations.7,10 After 2–3 laser catheter passes, a follow-up coronary angiography was performed to evaluate the efficacy of laser application and assess the feasibility of stent implantation. TIMI grade flow was recorded after the ELCA procedure (Post-ELCA TIMI grade flow) and once the PCI would have been completed (final TIMI grade flow). Technical success was defined as the ability to advance the laser catheter through the entire target lesion and deliver laser energy successfully. Procedural success was defined as achieving a final TIMI grade ≥ 2 flow without any major cath lab-related complications, such as death, coronary perforation, or emergency bypass surgery after PCI completion. All procedural complications, including death, coronary perforation,11 emergency bypass surgery, distal embolization, ventricular arrhythmia, and no-reflow were carefully documented and reported. Follow-up was conducted via retrospective review of health records, and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) defined as a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, new myocardial infarction, and target lesion revascularization were recorded at the follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or as the median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Inter-group comparisons were performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and were analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate.

The composite endpoint of MACE was analyzed as time-to-event data at the follow-up. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed to estimate the event-free survival rates. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics (version 23.0, IBM Corp., United States). A 2-tailed P value < .05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Between July 2015 and August 2024, a total of 130 PCI s were performed in patients with STEMI using ELCA as an adjuvant therapy for thrombus removal. The patients’ mean age was 61.8 ± 11.7 years, with 18 (13.8%) being women and 18 (13.8%) diagnosed with diabetes mellitus. ELCA was employed as the primary device for thrombus dissolution in 66 cases (50.8%) and as a bailout strategy in 64 cases (49.2%). Within the bailout group, manual thrombus aspiration was performed in 47 cases (36.2%), balloon dilation in 6 cases (4.6%), and thrombus debulking using the dotter effect in 11 cases (8.5%).

In the overall cohort, 124 patients (95.4%) presented with culprit lesions with a LTB. Before laser energy application, TIMI grade-0 flow was reported in 79 (60.8%) cases TIMI grade-1 flow in 32 (24.6%). After ELCA, TIMI grade-2 and 3 flows were achieved in 45 (34.6%) and 66 (50.8%) cases, respectively; P < .001 (figure 1).

Figure 1. TIMI grade flow distribution before and after ELCA application. Stacked bar graph showing the distribution of TIMI grade 0-3 flows at 3 different time points: initial angiography, post-ELCA, and final angiographic result after PCI. A marked improvement in coronary flow is observed following ELCA, with a progressive increase in TIMI grade-3 flow from 6.2% to 74.6%. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction.

Technical success was achieved in 128 (98.5%) cases, and procedural success in 124 (95.4%) (table 1). Procedural success was significantly higher when ELCA was used as the initial strategy vs when it was used as the bailout strategy (100% vs 90.6%; P = .013). However, procedural time was significantly longer in the bailout vs the initial strategy group (69.81 vs 48.50 min, respectively) (table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| Variable (n = 130) | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, yr | 61.8 ± 11.7 |

| Female | 18 (13.8) |

| Hypertension | 59 (45,4%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 57 (43,8%) |

| Tobacco use | 78 (60%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 18 (13.8) |

| Killip classification | |

| I | 98 (75.4) |

| II | 18 (13.8) |

| III | 3 (2.3) |

| IV | 11 (8.5) |

| Radial access | 118 (90,7%) |

| Femoral access | 12 (9,3%) |

| Lesion localization | |

| LMCA | 3 (2,3%) |

| LAD | 55 (42,3%) |

| LCX | 8 (6,2%) |

| RCA | 64 (49,2 %) |

| Primary device | 66 (50.8) |

| Bailout strategy | 64 (49.2) |

| Large thrombus burden | 124 (95.4) |

| Laser catheter size, Fr | |

| 0.9 | 114 (87.7) |

| 1.4 | 16 (12.3%) |

| Procedural time, min | 60 (43–86) |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 22.2 ±12.2 |

| Laser frequency, Hz | 31 ± 10.4 |

| Laser fluency, mJ/mm2 | 46.5 ± 9.17 |

| Laser delivery time, s | 125.9 ± 83.4 |

| Technical success | 128 (98.5) |

| Procedural success | 124 (95.4) |

|

LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX: left circumflex artery; LMCA: left main coronary artery; RCA: right coronary artery. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|

Table 2. Difference in variables between the initial and bailout strategy groups

| Variable | ELCA as the initial strategy (n = 66) | ELCA as the bailout strategy (n = 64) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | 8 (12.1%) | 3 (4.7%) | .100 |

| Large thrombus burden | 64 (97%) | 60 (93.8%) | .440 |

| Technical success | 65 (98.5%) | 63 (98.4%) | 1.000 |

| Procedural success | 66 (100%) | 58 (90.6%) | .013 |

| Procedural time, median | 48.50 (38.83–66.61) | 69.81 (55.36–101) | < .001 |

|

ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty. Categorical data are presented as absolute value and percentage, n (%); and continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation or first and third quartiles. |

|||

One case of type IV coronary perforation, according to the modified Ellis classification, occurred in an octogenarian patient with an ecstatic and tortuous right coronary artery. Perforation sealing was achieved with the implantation of a covered stent. One cath lab-related death occurred in a patient with an uncrossable mid-segment of a left anterior descending coronary artery lesion and initial TIMI grade-3 flow. Following balloon dilation and partial advancement of the laser probe, complete vessel occlusion and suspected left main coronary artery dissection resulted in cardiac arrest and cath lab-related death.

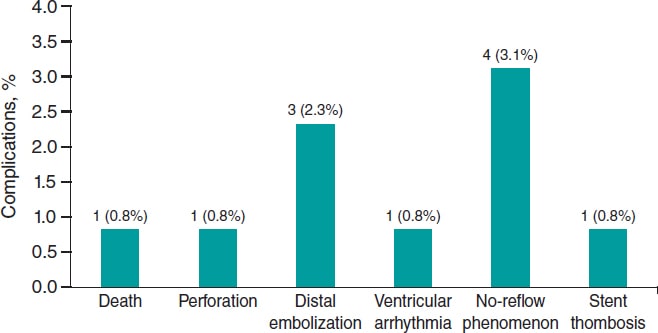

Other procedural complications included distal embolization in 3 (2.3%) cases and slow flow or no-reflow in 4 (3.1%). Among the slow/no-reflow cases, 1 occurred after laser application, and 3 following stent implantation and/or post-dilation. All were successfully managed with optimal medical therapy, achieving final TIMI grade-2 flow. One episode of ventricular arrhythmia occurred during saline washout of the target vessel, requiring electrical cardioversion. Additionally, 1 case of stent thrombosis (0.8%) occurred intraoperatively (figure 2).

Figure 2. ELCA-related procedural complications. Bar chart showing the frequency and percentage of major complications during or immediately after ELCA. The most common was no-reflow (3.1%), followed by distal embolization (2.3%). Other events (death, perforation, ventricular arrhythmia, and stent thrombosis) were rare (0.8% each). ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

Long-term follow-up data were missing for 6 patients (4.6%). At the 2-year follow-up, the event-free rate for combined MACE was 0.80 (95%CI, 0.73–0.88) as determined by the Kaplan–Meier estimator (table 3 and figure 3).

Table 3. List of adverse clinical events

| Patient No. | Event | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | Death | 1 |

| 13 | Death | 493 |

| 15 | Death | 148 |

| 23 | Death | 11 |

| 33 | Death | 170 |

| 36 | Death | 4 |

| 43 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 39 |

| 50 | New myocardial infarction | 213 |

| 61 | Death | 16 |

| 77 | Death | 1 |

| 83 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 119 |

| 84 | Death | 4 |

| 92 | Death | 1 |

| 98 | Death | 0 |

| 101 | Death | 37 |

| 110 | Death | 0 |

| 113 | Death | 12 |

| 118 | Death | 253 |

| 121 | Death | 139 |

| 124 | New myocardial infarction associated with TLR | 291 |

| 128 | Death | 10 |

|

TLR, target lesion revascularization. Lost to follow-up: 6 patients (4.6%). |

||

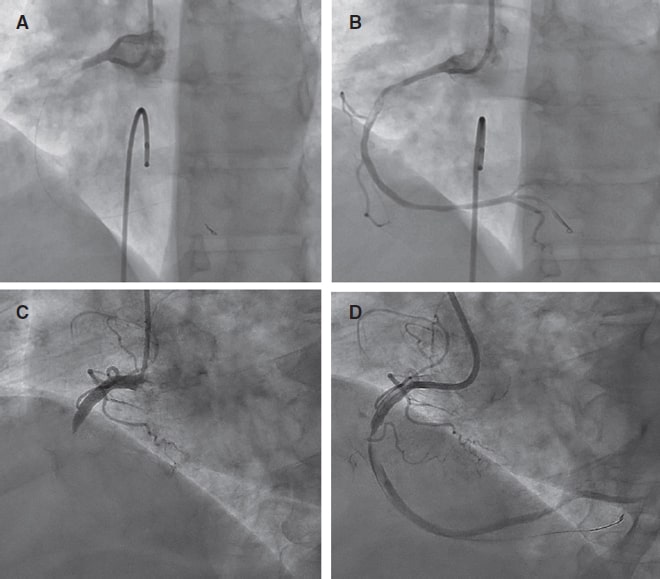

Figure 3. Pre- and post-ELCA findings in 2 typical cases of right coronary artery with large thrombus burden. ELCA, excimer laser coronary angioplasty.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this single-center study is that coronary laser angioplasty is a feasible, safe, and effective adjuvant therapy in the context of PCI (videos 1-4 of the supplementary data), demonstrating a low rate of complications and an acceptable long-term rate of MACE.

Data on the use of ELCA in acute myocardial infarction remain limited, with most evidence coming from non-randomized clinical trials. The CARMEL trial,12 the largest multicenter study to date, evaluated the safety, feasibility, and acute outcomes of ELCA in patients with acute myocardial infarction within 24 h of symptom onset requiring urgent PCI. TIMI grade flow significantly improved after laser application, increasing from 1.2 to 2.8, with an overall procedural success rate of 91% and a low distal embolization rate of 2%, even though 65% of cases had a LTB. In our study, 95.4% of the patients had culprit lesions with a LTB, and laser delivery significantly improved the mean TIMI grade flow from 0.6 to 2.29, with a comparable distal embolization rate of 2.3%.

Arai et al.13 retrospectively analyzed 113 consecutive acute coronary syndrome cases undergoing PCI comparing an ELCA group (n = 48) with a thrombus aspiration group (n = 50). They found that ELCA was associated with a significantly shorter door-to-reperfusion time, a better myocardial blush grade, and fewer MACE vs thrombus aspiration. These favorable outcomes are likely attributable to ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi through acoustic shockwave propagation and dissolution mechanisms,12 as well as its capacity to suppress platelet aggregation kinetics (a phenomenon known as the ‘stunned platelet’ effect).14

Reperfusion injury to the coronary microcirculation is a critical concern during PCI in STEMI patients. While manual thrombus aspiration can reduce the rate of no-reflow in patients with a LTB, residual thrombi and decreased coronary flow following thrombectomy have been associated with a higher risk of no-reflow.15 In a study of 812 patients with STEMI and a LTB undergoing PCI, Jeon et al.16 reported that 34.4% experienced failed thrombus aspiration, defined as no thrombus retrieval, remnant thrombus grade ≥ 2, or distal embolization. This failure was associated with an increased risk of impaired myocardial perfusion and microvascular obstruction.

ELCA’s ability to vaporize thrombi (with a low rate of distal embolization) and mitigate platelet activation, key cofactors in myocardial reperfusion damage,17 can potentially reduce this undesirable effect. Although the direct impact of ELCA on coronary microcirculation in PCI has not been well documented, evidence from smaller studies suggests potential benefits. For example, Ambrosini et al.18 investigated ELCA in 66 patients with acute myocardial infarction and complete thrombotic occlusion of the infarcted related artery, demonstrating excellent acute coronary and myocardial reperfusion outcomes (as assessed by the myocardial blush score and the corrected TIMI frame count), as well as a low rate of long-term left ventricular remodeling (8%). The significant improvement in mean TIMI grade flow observed immediately after ELCA application in our cohort may indirectly suggest a protective effect of this technique on coronary microcirculation. However, the lack of large studies comparing ELCA with conventional STEMI treatment limits the ability to definitively confirm the benefits of coronary laser therapy in this setting. Shibata et al.19 explored the impact of ELCA on myocardial salvage using nuclear scintigraphy in 72 STEMI patients and an onset-to-balloon time < 6 h, comparing ELCA (n = 32) and non-ELCA (n = 40) groups. Their findings indicated a trend towards a higher myocardial salvage index in the ELCA vs the non-ELCA group (57.6% vs 45.6%).

Limitations

This study has several limitations. It is a retrospective analysis, which inherently introduces biases related to data collection, interpretation and application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Besides, the absence of a comparative group limits the ability to establish the definitive clinical benefit of ELCA and its potential superiority over other strategies in the context of STEMI patients undergoing PCI. Furthermore, while the significant improvement of TIMI grade flow observed after laser application suggests potential benefits for coronary microcirculation, we did not directly assess this effect or thrombus burden reduction since post-ELCA thrombus grading was not systematically recorded. Unfortunately, in our retrospective database, PCI details (segmental analysis of coronary arteries and classification), the use of intravascular imaging modalities, dual antiplatelet therapy regimens (aspirin in addition to a potent P2Y12 inhibitor, or clopidogrel when prasugrel or ticagrelor were contraindicated, was routinely prescribed following current guidelines recommendations) or post-PCI echocardiography or cardiac magnetic resonance parameters were not systematically collected (unavailable in the health reports we revised) and follow-up data were missing for 4.6% of patients, all of which limited our ability to assess their potential impact on clinical outcomes. Last, our findings represent the experience of a single center, the percentage of women and patients with diabetes is relatively low, and procedures were performed by 5 trained operators, which may limit the external validity of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

ELCA seems to be an effective device for thrombus dissolution in the STEMI scenario, with excellent technical and procedural success rates. Besides, a low complication rate and favorable long-term outcomes with an acceptable event-free survival rate was observed in the present cohort.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the center Ethics Committee (waiving the need for informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the investigation) in full compliance with national legislation and the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Sex was reported as per biological attributes (SAGER guidelines).

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The authors state that no generative artificial intelligence technologies were used in the preparation or revision of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Pernigotti and M. Mohandes were responsible for the conceptualization and study design and contributed equally as co-first authors. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, R. Bejarano, H. Coimbra, F. Fernández, C. Moreno, M. Torres, J. Guarinos were involved in data collection and statistical analysis. M. Mohandes, A. Pernigotti, and J.L. Ferreiro were involved in manuscript drafting and critical revision and were responsible for the supervision and final approval. All authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and consented to its submission to the journal. Each author reviewed all results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript. J.L. Ferreiro declared having received speaker’s fees from Eli Lilly Co, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Rovi, Terumo and Ferrer; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Co., Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biotronik; and research grants from AstraZeneca, not related to this manuscript.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ELCA is a specialized technique used as adjuvant therapy during PCI for STEMI, particularly in patients with LTB.

- Although former studies have shown that ELCA can improve coronary flow and potentially reduce thrombotic material, data in the setting of acute myocardial infarction remain limited.

- ELCA is mostly used in high-volume centers by experienced operators, and standardized criteria for use in STEMI patients are not consistently reported in the literature.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This is one of the largest retrospective single-center series (130 patients) ever reported on the use of ELCA in STEMI patients with angiographically defined LTB.

- The study shows a high rate of technical and procedural success, significant improvement in TIMI flow, low rate of complication, and acceptable long-term outcomes.

- It provides detailed information on operator training, device selection, and laser settings, contributing to transparency and reproducibility.

- It also identifies current limitations in data reporting (eg, lack of systematic thrombus grading or dual antiplatelet therapy regimen documentation), underscoring the need for standardization in future studies.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 2. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 3. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

Vídeo 4. Mohandes M. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M25000537

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

2. Kim MC, Cho JY, Jeong HC, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of transient and persistent no reflow phenomena following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Korean Circ J. 2016;46:490-498.

3. Sardella G, Mancone M, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, et al. Thrombus aspiration during primary percutaneous coronary intervention improves myocardial reperfusion and reduces infarct size:the EXPIRA prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:309-315.

4. Jolly SS, Cairns JA, Yusuf S, et al. Randomized trial of primary PCI with or without routine manual thrombectomy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1389-1398.

5. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization:Executive summary. Circulation. 2022;145:e4-e17.

6. Grundfest WS, Litvack F, Forrester JS, et al. Laser ablation of human atherosclerotic plaque without adjacent tissue injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:929-933.

7. Mohandes M, Fernández L, Rojas S, et al. Safety and efficacy of coronary laser ablation as an adjuvant therapy in percutaneous coronary intervention:a single-centre experience. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:241-246.

8. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O'Kane P. Coronary intervention with the excimer laser:review of the technology and outcome data. Interv Cardiol Rev. 2016;11:27-32.

9. Gibson CM, de Lemos JA, Murphy SA, et al. Combination therapy with abciximab reduces angiographically evident thrombus in acute myocardial infarction:a TIMI 14 substudy. Circulation. 2001;103:2550-2554.

10. Topaz O, Das T, Dahm J, et al. Excimer laser revascularisation:current indications, applications and techniques. Lasers Med Sci. 2001;16:72-77.

11. Ellis SG, Ajluni S, Arnold AZ, et al. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-2730.

12. Topaz O, Ebersole D, Das T, et al. Excimer laser angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction (the CARMEL multicenter trial). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:694-701.

13. Arai T, Tsuchiyama T, Inagaki D, et al. Benefits of excimer laser coronary angioplasty over thrombus aspiration therapy for patients with acute coronary syndrome and thrombolysis in myocardial infarction flow grade 0. Lasers Med Sci. 2022;38:13.

14. Topaz O, Minisi AJ, Bernardo NL, et al. Alterations of platelet aggregation kinetics with ultraviolet laser emission:the “stunned platelet“phenomenon. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:1087-1093.

15. Ahn SG, Choi HH, Lee JH, et al. The impact of initial and residual thrombus burden on the no-reflow phenomenon in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26:245-253.

16. Jeon HS, Kim YI, Lee JH, et al. Failed thrombus aspiration and reduced myocardial perfusion in patients with STEMI and large thrombus burden. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:2216-2225.

17. Rezkalla SH, Kloner RA. No-reflow phenomenon. Circulation. 2002;105:656-662.

18. Ambrosini V, Cioppa A, Salemme L, et al. Excimer laser in acute myocardial infarction:single centre experience on 66 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2008;127:98-102.

19. Shibata N, Takagi K, Morishima I, et al. The impact of the excimer laser on myocardial salvage in ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction via nuclear scintigraphy. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:161-170.