Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

INTRODUCTION

Therapies for the management of heart failure have been responsible for the great benefit experienced by the population in terms of hope and quality of life. However, they are nothing more than palliative measures that have not resolved the tissue destruction due to this problem whose malignity causes 20 million cardiac deaths worldwide every year.1 Reparative and regenerative medicine was born over 2 decades ago as a biological response to the pressing need for innovation in this field. Its objective is to orchestrate diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies to restore the molecular, cellular, and tissue health of the cardiac organs damaged.2

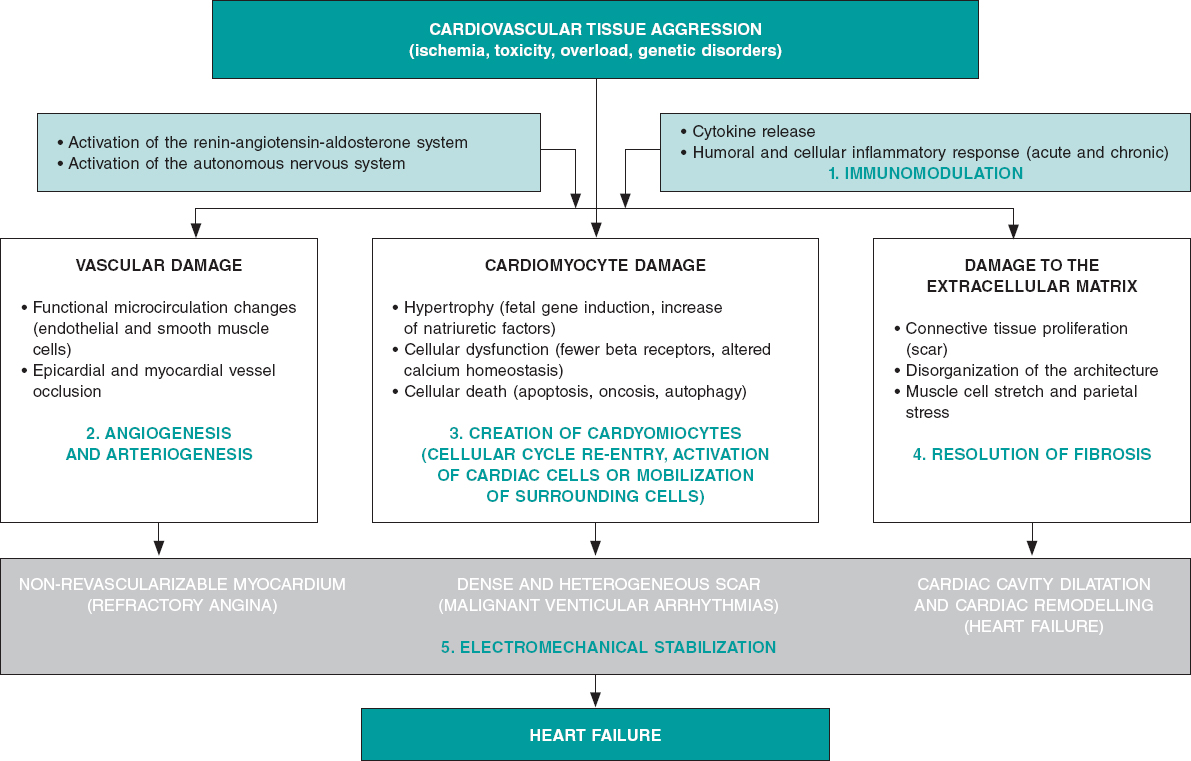

Although we can categorically say that the adult heart has a limited capacity for regeneration that depends on the formation of new cardiac muscle, endothelial and smooth muscle cells from a reservoir of existing heart stem cells,3 we can also say that this capacity is marginal and insufficient to repair cardiac organs after sustaining ischemic, toxic, valvular or inherited damage,4 even after physiological aging.5 On the contrary, the myocardium major repair response consists of cellular hypertrophy, in some cases, and replacement of damaged functional tissue by more or less dense fibrous tissue (scar) in most cases. Process that causes the adverse ventricular remodeling that defines the advanced stages of heart failure (systolic ventricular disfunction and cardiac cavity dilatation) of both ischemic and non-ischemic origin (figure 1).

Figure 1. Common biopathological mechanisms indicative of myocardial damage in its vascular, muscular, extracellular components due to different types of tissue damage including the role of neurohormonal compensatory mechanisms and inflammatory response. The bottom shows the 3 main componentes of heart failure (angina, ventricular arrhythmias and ventricular remodelling). In green, the 5 beneficial action mechanisms confirmed by basic, preclinical research through which reparative and regenerative therapies work.

FUNDAMENTALS OF PATHOBIOLOGY AND PRECLINICAL EXPERIENCES

Ever since the 1990s, different types of cells have been studied in the lab in small and large animal models; in chronological order: skeletal myoblasts, hematopoietic end endothelial cells (in most cases harvested from the bone marrow), mesenchymal cells (harvested from bone marrow or adipose tissue), cardiac cells and, recently, embryonic or adult somatic induced pluripotent stem cells.6 All these types of cells have been studied mostly in ischemic heart disease models. In some cases, they have been explored in their allogenic origin of healthy donors of the same species (unlike autologous stem cells that are harvested from the same recipient). As years have gone by, new products have appeared with regenerative or reparative capabilities. Added to gene therapy that has coexisted with cell therapy almost since the beginning, “non-cellular” products have been developed (growth factors, cytokines, proteins or types of ribonucleic acid—microARN). Many of them contained in microvesicles or exosomes that release stem cells or adult cells when they suffer an aggression. These products together with tissue engineering platforms (nanoparticles, gels, and matrices), have recently become part of regenerative medicine; and clinical research is still in its infancy.

Lab experiments and animal model experimentation have been useful because they have proved that: a) the process of myocardial and vascular repair is incredibly complex, both on the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels, which to this day, it is mostly unknown; b) the contribution made by cardiac stem cells to this process is marginal as it is the re-entry process of mature cardiomyocytes to the cellular cycle; c) the beneficial effects of the different products in the myocardium are due to the effect of the proteins and cytokines released by the cells administered (paracrine effect). They are not due to cellular fusion, proliferation or differentiation of these cells into cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells or smooth muscle cells (this has only been confirmed with pluripotent and embryonic cells that are still not used in clinical research); and d) these positive effects include protection from apoptosis, reduced fibrous tissue resulting from myocardial damage, modulation of the inflammation that precedes or is associated with such damage, creation of new blood vessels or formation of small amounts of cardiomyocytes (figure 1).

However, as in other areas of cardiovascular research,7 there has also been a significant “translational gap” in regenerative medicine, and the closer animal research has been to human clinical features the lower the impact of the therapies applied. For example, a meta-analysis of 80 studies showed that in small animal models, the average reduction of the infarction size with different products was 11%.8 However, in large animals, this reduction was only 5%, and it is well-known that in humans it is between 2% and 4%.9 This discrepancy in the results obtained in animals and humans is partly explained by the complexity of cellular processes that regulate cardiac repair, the enormous size difference among species, and the amount of cells (or products) needed to revert it. Other areas with room for improvement and other concepts that require further study regarding preclinical research are doses, administration times, and combination of products. Lastly, the rigor of clinical research is not always thoroughly applied to animal research. This means that it is required to standardize animal models and protocols to obtain and prepare repair products and develop multicenter, randomized and previously registered studies.2

CLINICAL EVIDENCE

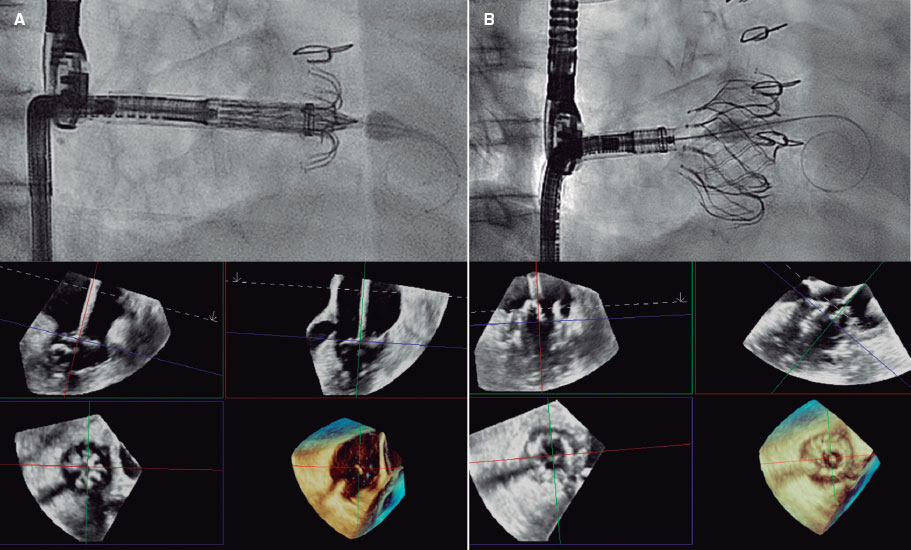

The pressing need for innovation in the management of heart failure promoted research in human regenerative therapies early on. Phase I and pilot studies would soon be followed by clinical trials with small numbers of patients. Some products reached phase III in clinical research, particularly in patients with acute myocardial infarction, refractory angina or ischemic and non-ischemic heart failure. Of all the evidence available to this day these conclusions can be drawn: a) except for exceptional well-identified cases (ventricular arrhythmias with initial cellular types), all products administered in humans have proven safe and no cases of rejection (not even with allogenic products), oncogenesis, worsening of the patients’ cardiovascular status or major complications during the administration have been reported; b) the real clinical efficacy of these therapies has not been undeniably confirmed through hard endpoints. While some studies have shown neutral results, others have confirmed a reduction of the infarction size, increased myocardial perfusion or ejection fraction, and better soft endpoints; c) the most promising scenarios are heart failure with systolic ventricular dysfunction and refractory angina; and d) a large and very sophisticated array of administration strategies, including surgical, has been developed (mostly percutaneous) to allow the injection of biological materials in certain cardiac regions using conventional or special catheters and navigational systems to accurately guide the administration.

Like the preclinical setting, the clinical evidence available allows us to identify some of the variables that should be confirmed and better defined before conducting large-scale clinical trials; among them, the selection of the type of product, the total dose, and the optimal administration time for every particular condition. Also, comparative studies of products, repeated administration, and improvement of myocardial retention in the products infused or injected. All these aspects should be rigorously analyzed through basic and preclinical research before conducting new studies in humans. At this point, the rigorous design of clinical trials with well-defined endpoints, adequate sample sizes, and strict regulatory control should be mentioned here.

INTERNATIONAL ALLIANCES AND SPECIFIC WORKING GROUPS

As part of the development of regenerative medicine, and to go deeper in its study and organize and structure a still marginal research, 2 main organizations have been created:

-

– The international consortium TACTICS (Transnational Alliance for Regenerative Therapies in Cardiovascular Syndromes).10 This consortium includes over top 100 international research working groups in this field. It is an worldwide, collaborative consortium network for the writing of position papers and recommendations, the rigorous promotion in all settings (scientific, institutional, and social), and for the design and development of coordinated and efficient clinical and preclinical research projects.

-

– The Working Group on Cardiovascular Regenerative and Reparative Medicine,11 is part of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). It is a dynamic body founded on the pillars of training, education, research, congress participation, and field support as defined by the ESC rules and regulations.

The common initial objective of both associations is to analyze the evidence available on cardiovascular regenerative and reparative medicine, establish future research lines, and ultimately, facilitate the development of therapies to improve the patients’ cardiovascular health.

CONCLUSIONS

Although the clinical efficacy of regenerative and reparative medicine has not been confirmed yet to be able to include it in the routine clinical practice, it has overwhelmingly contributed to broaden our knowledge on the molecular biological, cellular, and tissue processes that govern functional loss, homeostasis, and cardiovascular system repair. By analyzing and planning future studies using multicenter, multidisciplinary, coordinated, evidence-based, rigorous methodology we will be closer to obtaining therapies capable of partially or totally reversing irreversible myocardial tissue damage and improving cardiovascular health.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

REFERENCES

1. GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736-1788.

2. Fernández-Avilés F, Sanz-Ruiz R, Climent AM, et al. Global position paper on cardiovascular regenerative medicine. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2532-2546.

3. Messina E, De Angelis L, Frati G, et al. Isolation and expansion of adult cardiac stem cells from human and murine heart. Circ Res. 2004;95:911-921.

4. Bergmann O, Zdunek S, Felker A, et al. Dynamics of Cell Generation and Turnover in the Human Heart. Cell. 2015;161:1566-1575.

5. Climent AM, Sanz-Ruiz R, Fernández-Avilés F. Cardiac rejuvenation:a new hope in the presbycardia nightmare. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2968-2970.

6. Buja LM. Cardiac repair and the putative role of stem cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;128:96-104.

7. Roolvink V, Ibáñez B, Ottervanger JP, et al. Early Intravenous Beta-Blockers in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Before Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2705-2715.

8. Zwetsloot PP, Végh AM, Jansen of Lorkeers SJ, et al. Cardiac Stem Cell Treatment in Myocardial Infarction:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Preclinical Studies. Circ Res. 2016;118:1223-1232.

9. Fisher SA, Doree C, Mathur A, et al. Meta-analysis of cell therapy trials for patients with heart failure. Circ Res. 2015;116:1361-1377.

10. TACTICS Alliance. Available online:https://www.tacticsalliance.org. Accessed 7 Oct 2019.

11. ESC Working Group on Cardiovascular Regenerative and Reparative Medicine. Available online:https://www.escardio.org/Working-groups/Working-Group-on-Cardiovascular-Regenerative-and-Reparative-Medicine. Accessed 7 Oct 2019.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario Gregorio Marañón, Dr. Esquerdo 46, 28007 Madrid, Spain.

E-mail address: (F. Fernández-Avilés).

Talking about innovation can be confusing. The term “innovation” is used to refer to many different things and proof of this is the large number of different definitions currently available. In any case, innovation is almost a magical word often hiding huge expectations of possible solutions to the great challenges posed by society and that have a dramatic impact on healthcare. We present some of the current trends and reflections affecting the Spanish healthcare system providers.

INNOVATION: GENERATING THE PRODUCT

At this point in time, talking about lists in relation to research and development (R+D) and its situation in Spain is an obvious and overused argument these days. Figures are well-known, have already been confirmed, are widely accepted, and have showed room for improvement over the last few decades: our country ranks high in research but runs low on R+D funding (high efficiency), especially in the private sector (mainly related to the business structure of small and medium-sized enterprises) but innovation still lags behind. Coming to terms with the specific weight of the different possible causes for this gap between research and innovation (culture, funding, education, regulation, etc.) is even harder.1

The impact of a disadvantaged situation in innovation is relevant: we do not invent, so we never own what we need (understood as a product manufactured and marketed by Spanish companies), which means we have to import it. Regarding health—where the impact of technology and drugs is huge—the effect the trade balance may have is considerable. Undubitably, this is a field where the activity of the Spanish healthcare system as a country that generates products, patents or companies may have a significant economic impact.2,3

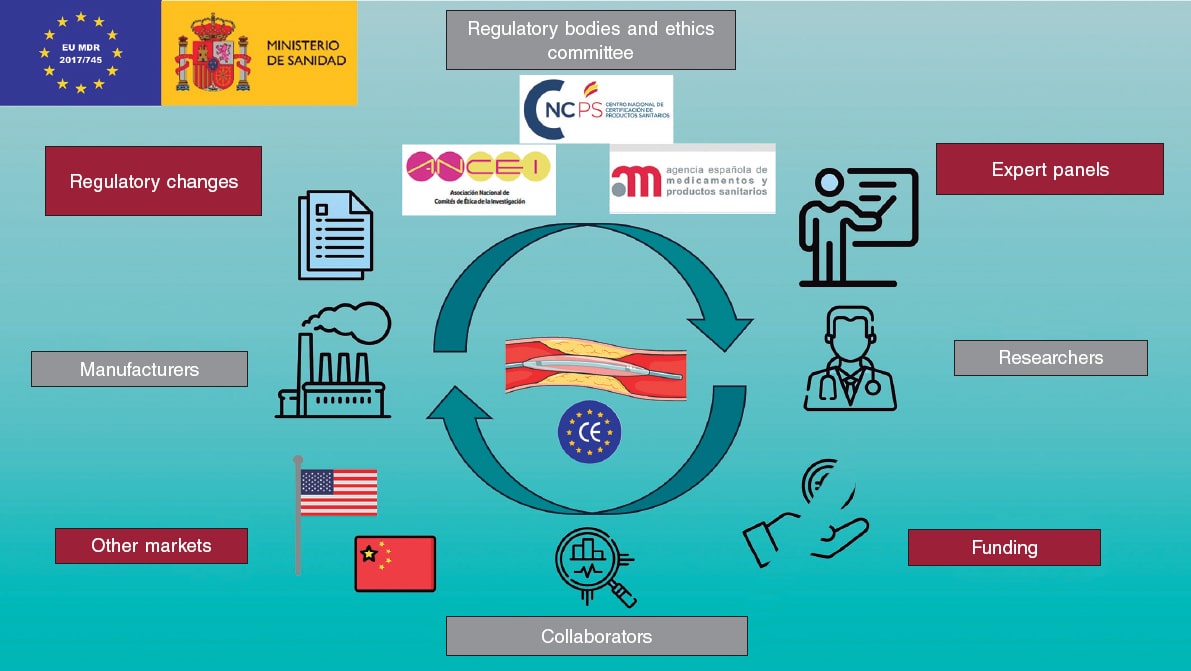

INNOVATION: INTRODUCING THE PRODUCT

Advances in medicine are the key to improve disease management and prevention. The speed at which new products like drugs, devices, machines, diagnostic procedures, etc. are available is now greater than ever. These advances are considered innovation and they become part of the therapeutic arsenal available after an often very expensive process of development where proprietary companies make big investments. The cost of these new products is sometimes considerable and their benefits in terms of incremental net health benefit do not usually match costs and are often limited. Two examples of striking innovations that have recently impacted the media because of their potential cost are the CAR T-cell therapy and proton radiotherapy. Another recent example of great therapeutic innovation is the curative treatment of hepatitis C. The total artificial heart is unquestionably relevant innovation in cardiology. The developing speed of technologies like 3D printing, artificial intelligence, big data, digital health or tele-healthcare forces us to understand what they are good for before implementing them in health organizations and also to assess their impact in the system. In these innovations, price, complexity, conditions of use, and effects greatly condition their use.

INNOVATION: USING THE PRODUCT

Management experts have been anticipating the arrival of a sustainable prevention healthcare model for decades because of the constant growth of healthcare spending due to a number of reasons: higher costs in healthcare innovation, increased chronicity and longevity, and greater expectations from the population.

Patients live longer but they also remain sick longer, and every month of life gained equals higher costs. Although this statement has several exceptions, it forces us to identify those patients who can live disease-free for longer, or, at least, not dependant on the healthcare system. Also, it shows what innovations bring real value both in general and particular terms. Precision medicine and innovation in management play a big role. Both concepts can be considered a spectral continuum in the decision-making process. On the other hand, knowing that these innovations are cost-effective is no longer enough; now it is required to know what their real impact is on population health outcomes like quality of life and disease progression. This is how the Spanish healthcare system is moving forward with the great challenge posed by value-based medicine.4

INNOVATION: ORGANIZATION AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

There are 3 different scenarios regarding innovation: production, introduction, and use. These 3 settings require 3 different fields of expert knowledge —innovation manager, health professional, and healthcare manager— with significant overlapping that still coincides in information systems and new data management. In this context, the great expectations generated by big data and artificial intelligence should not be a surprise. These are true innovations to help us make decisions, prioritize efforts, speed up healthcare processes, reduce the load of tasks with no added value for health professionals, and eventually focus on personal attention.5

Beyond the traditional concept of product understood as technology—devices or drugs—healthcare providers have always been involved by generating solutions in their setting adapted to their working framework and using the existing resources based on process innovation. Healthcare providers can change the way things are done, most of the time intuitively, and then adapt them to their setting thanks to years of experience. They often give their opinion on current needs and possible solutions to different settings. They also happen to be right most of the time.

This may be an organizational innovation we must face: to hear what health professionals have to say to share the decision-making process with them. Also, to support them in complex priority decision-making processes caused by limited resources in a society with growing well-being demands. It is the healthcare institutions that need to move towards more intelligent and collaborative ecosystems to promote a culture of innovation. Innovative ideas have always been there; time has come to listen to the people who had these ideas, evaluate them rigorously, focus on the impact they have on health outcomes, and promote innovation.6-8

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

The road towards innovation is a long one and changing the productive model and the culture of an entire country is a huge challenge. However, over the last few decades, it has been proven that we can change the Spanish model of producing science together. Why not do the same thing with innovation?

Let’s give ourselves the time and opportunity to innovate in health, instead of letting others do the job. Let’s be us who, with our own knowledge, improve our healthcare system, one of the world’s most efficient healthcare systems now facing huge challenges ahead.9

FUNDING

The authors have received funding from the Medical Technology Innovation Platform (ITEMAS) (PTR2018.001071, PT17/0005/0036) sponsored by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Project co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Fundación Cotec. Informe Cotec 2019. Innovación en España. Madrid:Fundación Cotec para la Innovación;2019.

2. Mulet J. Política de innovación para España. Necesidad y condicionantes. Fedea Policy Papers. 2016. Available online:http://documentos.fedea.net/pubs/fpp/2016/07/FPP2016-12.pdf. Accessed 25 Oct 2019.

3. Aloini D, Martini A. Exploring the exploratory search for innovation:a structural equation modelling test for practices and performance. Int J Technol Manage. 2013;61:23-46.

4. Barge-Gil A, Modrego A. The impact of research and technology organizations on firm competitiveness:Measurement and determinants. J Technol Transfer. 2011;36;61-83.

5. Bason C, ed. Leading public sector innovation. Co-creating for a better society. 2nd ed. Bristol:Poliy Press;2018.

6. Pan SW, Stein G, Bayus B, et al. Systematic review of innovation design contests for health:spurring innovation and mass engagement. BMJ Innov. 2017;3:227-237.

7. Bergeron K, Abdi S, DeCorby K, Mensah G, Rempel B, Manson H. Theories, models and frameworks used in capacity building interventions relevant to public health:a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:914.

8. Allen JD, Towne SD Jr, Maxwell AE, et al. Measures of organizational characteristics associated with adoption and/or implementation of innovations:A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:591.

9. GBD 2016 Healthcare Access and Quality Collaborators. Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations:a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;391:2236.

Corresponding author: Edificio IDIVAL, Avda. Cardenal Herrera Oria s/n, 39011 Santander, Cantabria, Spain.

E-mail address: (G. Peralta Fernández).

The sex-based differences in approach and mortality in the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) have been known for a while now. Back in 1991 the New England Journal of Medicine published an editorial1 on this matter. In this article Healy coined the term “the Yentl Syndrome” to refer to the invisibility of women in the studies of cardiovascular disease. She argued that women should behave according to the masculine clinical standards to receive the same care; otherwise they were misdiagnosed and mistreated resulting in healthcare of a lower quality and effectiveness.

Over the last few decades, cardiovascular mortality has decreased thanks to the advances made in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of ischemic heart disease. This improvement has benefited women as well. According to the RESCATE II registry,2 between 1992 and 2003, in-hospital mortality after a first acute myocardial infarction decreased 25% in women. In spite of this, unlike what happens with males, circulatory system diseases are still the leading cause of mortality among women.3 In the study presented by Anguita et al.4 in the last European Congress of Cardiology, female sex was still an independent predictor factor of mortality in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) in Spain. In this study, the authors retrospectively analyzed the Minimum Basic Data Set of the Spanish Ministry of Health from 2005 through 2015. They identified 325 017 patients with STEMI of whom 38.8% were women, and concluded that in-hospital adjusted mortality is still high in this group. It should be mentioned that odds ratio dropped from 1.28 in 2006 to 1.14 in 2014, which may indicative of better care to women with STEMI.

The article by Tomassini et al.5 recently published on REC: Interventional Cardiology is an in-depth analysis of primary angioplasty and midand long-term mortality in patients with STEMI based on sex differences. It is a retrospective analysis of all patients with STEMI presenting with < 12 h of chest pain who underwent a primary angioplasty at their center from March 2006 to December 2016; in total, 1981 patients (24.4%, women). According to other registries,6 compared to males, women are older (mean age 71.3 ± 11.6 vs 62.9 ± 11.8 years), have a higher prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, longer total ischemic times, and worse Killip functional class at admission. Oddly enough after matched propensity score analysis, with the same percentage of multivessel coronary artery disease (5.3% vs 4.7%) and stent implantation (82.9% vs 83.9%), the success of the procedure and ST-segment resolution were significantly lower in women (90.2% vs 94.4% and 47.5% vs 54.1%, respectively). The authors suggest that this is probably due to the different pathophysiology of acute myocardial infarction in women, but they do not say anything about the time elapsed from the first medical contact until guidewire crossing or subsequent medical therapy, variables that have a direct impact on the prognosis of patients.

As interventional cardiologists we have a hard time thinking that there may be different system delays because when the infarction code goes off, the most important thing is to find the ST-segment elevation on the EKG, the timeline of disease progression, and the patient’s clinical signs and hemodynamic status (not always in this order). In any case, we should not forget that treatment starts before and after our intervention.

A study conducted in Portugal7 revealed that delays from the first medical contact to radial access were 15 minutes longer among women. This is not an isolated datum. Huded et al.8 analyzed variability during management and the results of the STEMI care network from Cleveland Clinic (Ohio, United States). They observed worse quality of care in women, longer door-to-balloon times, and medical therapies inconsistent with the guidelines in a higher percentage of cases. The implementation of an adapted protocol improved these parameters, especially among women (the percentage of women who received medical therapy as recommended by the guidelines rose to 98%, and system delays were reduced in 20 minutes). Overall, in-hospital mortality decreased 43%. This makes us think that maybe the variability seen in the management of STEMI is something generalized, that the reduction of discrepancies is possible, and that it can reflect the quality and maturity of care networks.

It is noteworthy to discuss the atypical nature of symptoms in women as the cause for these delays. The VIRGO clinical trial9 interviewed 2009 women and 976 males between 18 and 56 years of age admitted due to an STEMI. In both groups, the main symptom was chest pain defined as pain, pressure, tension or discomfort (87% vs 89.5%). Also, women had more accompanying symptoms (58.5% showed more than 3 additional symptoms compared to 46.2% of males). These data are reproduced in another prospective study conducted at an ER that interviewed 1941 patients with suspected ACS. The study confirmed that 92% of women and 91% of males reported chest pain as the main symptom.10 When women were asked why did not they look for help earlier,11 most of them thought it was not an STEMI and they did not want to be called hypochondriacs if it was not serious after all. And they may be right. According to the VIRGO trial, 53% of women who previously sought medical attention were told that it was not an acute coronary event. Maybe as Healy used to say1 women do not belong in the medical and social category of ACS.

For all this, although the management of STEMI in women has improved over the last few decades, articles like Tomassini et al.’s5 are a friendly reminder that there is still work to be done. Not only clinical trials, but also daily gestures like rising the awareness of society and healthcare providers that STEMI affects everyone, women included.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Healy B. The Yentl Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:274-275.

2. García-García C, Molina L, Subirana I, et al. Sex-based Differences in Clinical Features, Management, and 28-day and 7-year Prognosis of First Acute Myocardial Infarction. RESCATE II Study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014;67:28-35.

3. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Defunciones según la causa de muerte. 2017. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?path=/t15/p417/a2017/l0/&file=01001.px&L=0. Accessed 1 Jun 2019.

4. Anguita M, Sambola Ayala A, Elola J, et al. Female sex is an independent predictor of mortality in patients with STEMI in Spain:a study in 325,017 episodes over 11 years (2005-2015). En:Paris 2019. ESC Congress 2019;2019 31 Aug - 4 Sept;Paris, France. Available online: https://esc365.escardio.org/Congress/ESC-CONGRESS-2019/Poster-Session-2-Risk-Factors-and-Prevention-Cardiovascular-Disease-in-Spec/197767-female-sex-is-an-independent-predictor-of-mortality-in-patients-with-stemi-in-spain-a-study-in-325-017-episodes-over-11-years-2005-2015. Accessed 15 Sept 2019.

5. Tomassini F, Cerrato E, Rolfo C, et al. Gender-related differences among patients with STEMI:a propensity score analysis. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M19000061.

6. Mehta L, Beckie T, Devon H, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Women, A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:916-947.

7. Araújo C, Laszczynska O, Viana M, et al. Quality of Care and 30-day Mortality of Women and Men With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:543-552.

8. Huded CP, Johnson M, Kravitz K, et al. 4-Step Protocol for Disparities in STEMI Care and Outcomes in Women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2122-2132.

9. Lichtman J, Leifheit E, Safdar B, et al. Sex Differences in the Presentation and Perception of Symptoms Among Young Patients With Myocardial Infarction. Evidence from the VIRGO Study (Variation in Recovery:Role of Gender on Outcomes of Young AMI Patients). Circulation. 2018;137:781-790.

10. Ferry A, Anand A, Strachan F, et al. Presenting Symptoms in Men and Women Diagnosed with Myocardial Infarction Using Sex-Specific Criteria. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e01297.

11. Lichtman JH, Leifheit-Limson EC, Watanabe E, et al. Symptom recognition and healthcare experiences of young women with acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015;8:S31-S38.

Spain was inducted in the European initiative Stent for Life in a ceremony hosted by the General Assembly of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) back in 2009. As president of the Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC), Dr. Fina Mauri signed the declaration of commitment with this initiative aimed to improve the access of patients to reperfusion by the increasing use of primary percutaneous coronary interventions (pPCI) as the optimal treatment in the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).

The Stent for Life initiative was born the previous year (September 2008) as an alliance among the Spanish Society of Cardiology, EAPCI, and Eucomed.1 In Europe the situation of reperfusion in the management of infarction was under discussion. They came to the conclusion that there was a great heterogeneity among the different countries with an overall scarce penetration of pPCI as the treatment of choice.2 These differences were not related to gross domestic product (GDP): countries with relative low GDPs (Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Poland, Lithuania) performed many more pPCIs per million inhabitants compared to other countries with higher GDPs like Spain.2 For this reason, Spain was among the 6 countries asked to participate in this initiative together with Turkey, France, Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia. All performed less than 200 pPCIs per million inhabitants (in 2008 only 165 PCIs per million inhabitants were performed in Spain). The objectives established at that time are shown on table 1; they were numerical objectives of implementation and penetration of this technique in the management of STEMI with the implicit creation of acute myocardial infarction networks.

Table 1. Objectives of the Stent for Life initiative from 2008

| Define regions/countries with unmet medical needs for the implementation of the optimal management of acute coronary syndrome |

|---|

| Implement an action program to increase the access of patients to pPCIs: a) Increase the percentage of pPCIs performed in > 70% of STEMI patients b) Achieve pPCI rates > 600 per million inhabitants/year c) Offer a 24/7 service in all necessary angioplasty centers for the full coverage of the region/country |

|

pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

Back in 2008, there were only 4 well-structured infarction networks across in Spain: Murcia, Galicia, Balearic Islands, and the Chartered Community of Navarre performed between 200 and almost 400 pPCIs per million inhabitants. However, eventually only 12.8% of the entire Spanish population benefited from these 4 networks. In the remaining autonomous communities, the pPCIs were performed erratically with numbers lower or closer to 100 pPCIs per million inhabitants. Regions like the Community of Valencia, the Principality of Asturias, and Andalusia performed 61, 78, and 106 pPCIs per million inhabitants).3 Like Europe, these regional differences were not related to the GDP of the different Spanish autonomous communities. Therefore, the creation of a myocardial infarction network with full hospital infrastructure, trained professionals, and a system of medical emergencies in a developed country like ours became a purely organizational matter. In October 2010 and with the explicit support from the SEC and its affiliate sections Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology, Ischemic Heart Disease, and Coronary Units the different scientific societies of the autonomous communities signed the declaration of membership to the Stent for Life initiative (figure 1). From that moment on, the focus was on 3 different levels for the progressive and gradual implementation of infarction networks. In the first place, there was a political and media approach to the different health administrations involved. The publication of the comparative results from the different autonomous communities in the media (figure 2) contributed effectively to their involvement in this issue. Parallel to this and thanks to scientific publications and cardiology meetings, professionals became aware on the clinical need to implement these infarction networks.4-7 Finally, patients were approached through commercial campaigns and media announcements with positive short-term results.8 Everything was mostly funded with the unconditional support from the industry. After 10 years of many people working for the Stent for Life initiative it can be said that it has contributed to the implementation of infarction networks nationwide. In 2018, 21 261 pPCIs were performed (13 395 back in 2008) with an average rate of 416 pPCIs per million inhabitants. This rate is considered adequate given the prevalence of ischemic heart disease in our country without great differences among the different autonomous communities.9 At this point, what challenges will the next decade bring? The survey of a paper recently published by Rodriguez-Leor et al.10 in REC: Interventional Cardiology may have some of the answer to this question. The current objectives should focus on both the patient and the healthcare provider. At this point it is not about opening new centers or programs anymore, but about designing the procedures required for each center to keep quality outcomes. The satisfaction of well-trained professionals built on adequate retributions, regulating the rest periods, and the correct sizing of staff based on the healthcare needs are all key issues to take into consideration at the infarction centers. Similarly, generational replacement should occur while keeping the quality of the entire process. The Administration should consider payment to centers based on results and make sure that these payments reach the treating physician. On the other hand, very complex cases like STEMI patients complicated with cardiogenic shock should be referred to specialized centers capable of performing advanced ventricular assist techniques, heart surgery, and transplants. In this type of patients, mortality rate is still very high (around 50%). Therefore, each infarction network should be able to identify its shock centers for the adequate management of these patients.

Figure 1. A: induction ceremony of the scientific societies of the different autonomous communities into the Stent for Life initiative (Madrid, October 4, 2010); B: certificate of membership to the Stent for Life initiative of an affiliate society (Society of Cardiology of Castile and León).

Figure 2. Examples of news published by the media on comparative results among different autonomous communities on the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

In conclusion, the objectives of the Stent for Life initiative in our country should look at the new clinical and professional challenges ahead with the patient as the protagonist of all clinical actions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Dr. Matías Feldman, Dr. Ander Regueiro, Dr. José Ramón Rumoroso, and Dr. Miren Tellería for their dedication to the Stent for Life initiative in Spain over the last 10 years. We also wish to thank the members of the different boards of directors of the Hemodynamics and Interventional Cardiology Section of the SEC for their contribution to this paper.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Sabaté was the national coordinator of the Stent for Life initiative in Spain between 2009 and 2013. No other conflicts of interest have been reported.

REFERENCES

1. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Kaifoszova Z. Stent for Life:how this initiative began? EuroIntervention. 2012;8 Suppl P:P8-10.

2. Widimsky P, Wijns W, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction in Europe:description of the current situation in 30 acountries. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:943-957.

3. Baz JA, Pinar E, Albarrán A, Mauri J;Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 17th official report of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology (1990-2007). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:1298-1314.

4. Kristensen SD, Fajadet J, Di Mario C, et al. Implementation of primary angioplasty in Europe:Stent for Life initiative progress report. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:35-42.

5. Kristensen SD, Laut KG, Fajadet J, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction 2010/2011:current status in 37 ESC countries. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:1957-1970.

6. Regueiro A, Bosch J, Martín-Yuste V, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a European ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction network:results from the Catalan Codi Infart network. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009148.

7. Gómez-Hospital JA, Dallaglio PD, Sánchez-Salado JC, et al. Impact on delay times and characteristics of patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the southern metropolitan area of Barcelona after implementation of the infarction code program. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65:911-918.

8. Regueiro A, Rosas A, Kaifoszova Z, et al. Impact of the “ACT NOW. SAVE A LIFE“public awareness campaign on the performance of a European STEMI network. Int J Cardiol. 2015;197:110-112.

9. Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Cardiac Catheterization and Interventional Cardiology. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. Available online: https://www.hemodinamica.com/cientifico/registro-de-actividad/. Accessed 3 Jul 2019.

10. Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Alvarez A, Moreno R, et al. Survey on the needs of primary angioplasty programs in Spain. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:8-14.

Undertaking the project REC: Interventional Cardiology, a bilingual journal published in English and Spanish and devoted to interventional cardiology seems a gigantic task to implement, which is why we wish to thank the editors for their entrepreneurial spirit and also Revista Española de Cardiología for making space for this new project. A unique opportunity for developing agreements and team work for the entire Spanish-speaking cardiological community that often feels the imposing presence of English-speaking scientific journals.

Combining the organizational and academic trajectory and leadership of the Spanish Society of Cardiology and the vitality, thrust, and enthusiasm of the Latin American interventional cardiology community may be the beginning of a huge agreement of productivity and novelty. This may, in turn, help the communication network between the Spanish vision planted at the very heart of Europe and the Latin American one that influences over 600 million people, thereby exponentially increasing the opportunities of communication for members of scientific societies and the possibilities of providing relevant scientific information. Talent is universal, opportunities are not.

Although European and American clinical practice guidelines on evidence-based medicine have tremendous exposure and each country publishes its own guidelines, we have been unable to integrate these concepts in regional or intersociety guidelines or approved documents. Yet at the Latin American Society of Interventional Cardiology (Sociedad Latinoamericana de Cardiología Intervencionista, SOLACI) we have tried to integrate the interventional guidelines established by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions and the American College of Cardiology. REC: Interventional Cardiology could well serve as a forum for all interventional cardiology guidelines and consensus documents of our region.

We should also mention that several clinical trials, series, and clinical cases studied in Latin America, especially those including international collaborations or inter-society agreements, should be published in this journal.

Although most multicentric randomized evidence-based clinical trials that are conducted in the United States and Europe are published in English, many significant advances made in cardiovascular medicine such as saphenous vein grafts used in coronary artery bypass graft surgery, stents, and stent-grafts have come from doctors within our region, such as R.G. Favaloro, J. Palmaz, and J.C. Parodi. However, even though these advances may speak Spanish, they have been implemented by English-speaking countries, which is the main reason why cooperation and integration should be our guiding spirit. The goal of this journal is to contribute, not to compete.

Needless to say that the success of this project depends entirely on us; all interventional cardiologists in Ibero-America should convince ourselves that we are capable of producing quality educational material that is attractive, not only to us, but also to our colleagues in other specialties, both in Latin America and the rest of the world. We are convinced that this will be so.

80% of the teachers predict that by 2026 digital content will replace print. In this sense, the educational resources that turn learning into a videogame, such as virtual reality or gaming, and that are patrimony of the digital world1, will make learning a more interactive experience. The digital format of REC: Interventional Cardiology, with its tremendously dynamic character and adaptability to the user, will help amplify its educational purpose, making it an addictive yet healthy experience.

In the battle to conquer everyone’s attention, sensationalist tabloid-style material seems to have replaced academic writing. The focus should be on getting the attention of the specialists through an updated informative model that never loses its primary educational purpose.

Sitting talent and different visions at the same table multiplies the options of creativity. REC: Interventional Cardiology is a golden opportunity for generating knowledge, healthy controversy, and pushing the Latin American interventional medical practice to the limit, under the mentoring of Revista Española de Cardiología in an effort to make a useful and enriching difference in the final result published.

This will be a privileged stage for exchange and academic contribution for the Ibero-American interventional cardiology communities. Congratulations and best wishes!

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever regarding this manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Kali B. The Future of Education and Technology. Available at: https://elearningindustry.com/future-of-education-and-technology. Accessed 28 May 2019.

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

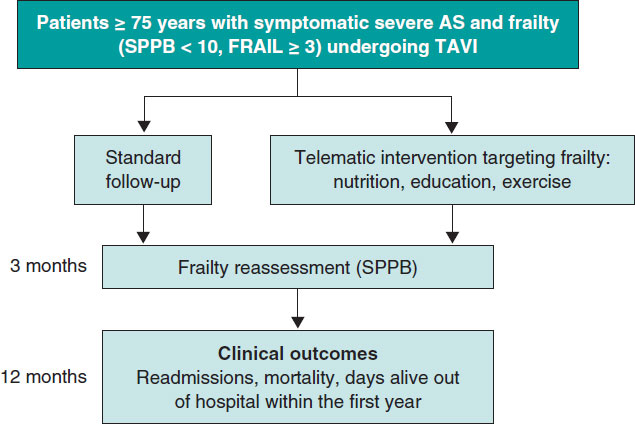

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España