Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

It comes as no surprise that the progression of medical training would eventually take a leap into the digital world where we would be able to access information without leaving our working place or the comfort of our homes. Our specialty, interventional cardiology, predominantly visual, has always benefited from the most advanced technology regarding communication. Actually, we have been doing this for years, even in our country: by the mid-1980s, the Madrid Interventional Course (MIC) organized by Dr. J.L. Delcán and Dr. E. García, was already broadcasting live cases via satellite to analyze and discuss new insights with larger audiences compared to those that can fit in a room. These days, live cases are an essential part of the meetings held in our setting (whether international like the ones organized by EuroPCR and TCT or national like the ones held by the Società Italiana di Cardiologia Interventistica [GISE] and the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology [ACI-SEC])3. These cases are discussed remotely by panels of experts with a growing interaction with in-person and remote attendees thanks to specific computer tools and social media. But it is not only the broadcast of live cases which benefit from these advances. We have had access to information on late breaking clinical trials through the Internet many times even before in-person meeting where these trials are often presented. Also, we have had access to the recordings of many simultaneous sessions we couldn’t attend in-person but can review later when we have the time.

The situation of the pandemic caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has accelerated this cross over to virtual meetings due to the impossibility of travelling to places and holding large in-person meetings.1 The main in-person cardiology meetings scheduled for 2020 have been suspended or turned into virtual meetings. The two largest international meetings already mentioned, EuroPCR and TCT, have become virtual meetings. Also, mass meetings like the ones held by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association or the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have followed in the footsteps of this digital transition. Our sister societies, the Italian GISE and the Portuguese Associação Portuguesa de Intervenção Cardiovascular (APIC) have done the same thing. But, when these restrictions are lifted, will in-person activities like large face-to-face congresses and meetings be gone for good? Let us look at the pros and the cons of virtual and in-person meetings2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pros of virtual meetings compared to face-to-face meetings.

These are the basic strengths of virtual meetings:

-

The speed at which these meetings are prepared is much faster compared to in-person meetings since there are many different tasks that the cardiology society does not need to do.

-

Lower costs: it is obvious that reducing travel and accomodation expenses, renting fewer available spaces, etc. reduces the overall budget. A direct consequence of this is a lower impact on the environment thanks to lower mobility.

-

Greater efficiency in the transmission of the message without time losses when going to the meeting or in-between sessions, possibility of increasing the capacity of the virtual rooms on demand and reviewing pre-recorded sessions on demand (even so, personal interaction will be gone).

-

Better attendance control: computer tools facilitate the comprehensive registry of attendance to every session, time, origin, and interaction developed, etc., but not the quality. Although we cannot fully know to what extent these attendees’ profit from these face-to-face meetings (exams may be an option?) leaving a device connected to these activities is no guarantee either.

-

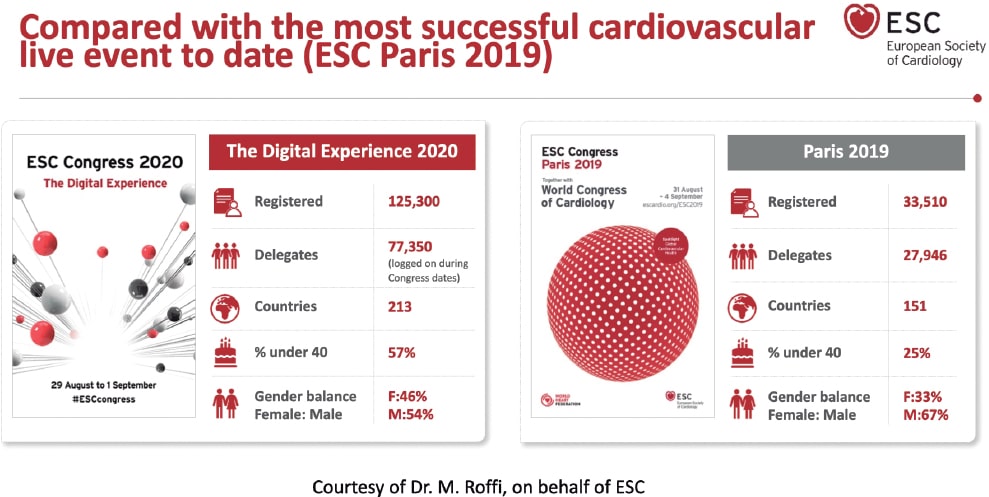

Universal access brings meetings to larger audiences erasing geographical borders: in the fully virtual EuroPCR of 2020 there were over 15 000 registrations (compared to 11 200 registrations in the 2019 in-person edition).3 This phenomenon was even more evident in the ESC congress of 2020. This meeting still holds the registration record with 125 000 registrations from 213 different countries4 compared to the previous year (33 500 registrations).5 (Figure 2). Can these figures be compared? Probably not because registration to these virtual editions was free of charge.

-

Adaptation to changing situations: this virtual format allows us to accommodate meetings to travel limitations or potentially infectious situations like the one posed by the current pandemic.

Figure 2. Registration comparison of the annual meetings held by the European Society of Cardiology back in 2019 and 2020.

The downsides of virtual meetings are:

-

Dependency on technical factors: technical support systems are excellent, but still depend on variables like the Internet bandwidth, the quality of connectivity or the incompatibilities of presentations and videos. After 25 years of use of the DICOM standard for the communication and management of medical imaging we still have issues when we try to play video sequences in virtual meetings.

-

To a great extent, the format of these sessions keeps the same structure as face-to-face meetings. The adaptation to the new virtual environment has been more cosmetic than a true reality with the implementation of several technological advances to mimic the in-person experience (avatars, virtual common rooms, chats to replace direct communication). However, fully developed specific methods of communication have not been implemented yet.

-

More difficult personal interaction: asynchronous communication and other virtual borders like lack of types of nonverbal communication (beyond emoticons) complicate connectivity among speakers, moderators, and audience. Speakers feel some kind of «digital loneliness» because they don’t receive any feedback from the audience. In turn, the audience experience “digital fatigue” and they can’t remain focused on anything for more than 30 minutes. New systems to encourage audience participation are desperately needed, particularly in the virtual format.

-

Agendas, time zones, and time devoted to work: in these virtual meetings it is not unusual to find conflicting time schedules since participants come from all across the world. It is not unusual either that these time schedules invade our spare time or affect our working day. The proliferation of these activities is associated with digital overload that has sometimes been referred to as «death-by-webinars»

-

Program sustainability: although our political representatives can’t wait to stop the private sector from funding our medical training programs, the truth is that this is crucial if we want to develop this kind of activity. If some of the activities that used to take place at face-to-face meetings are gone, will support still be the same? Isn’t it more profitable to conduct sponsored meetings and not independent activities?

Those of us who have been trained in the “traditional” meeting environment have a hard time thinking that they can be totally replaced by the virtual format. Here are some of the reasons why:

-

Attending a scientific meeting is a comprehensive experience that includes training as well as other activities: research coordination meetings, building up professional relations, consultancy and counseling, etc. It is almost impossible to conduct these activities outside the context of a scientific meeting.

-

In this sense, attending a face-to-face meeting is time-bound. It is not always easy to disassociate attendance to these meetings from working or face-to-face obligations (especially when the meeting is held in our own town), but it is actually easier compared to virtual meetings. In our setting there are work permits that can be issued to attend training sessions: could this be applicable to virtual meetings particularly with the current extended time schedules of such events?6

-

Most of the advantages seen in the broadcast of contents have long been part of face-to-face meetings. Consequently, most sessions are recorded for immediate broadcast and further reproduction. The same thing happens with in-person and remote audience interaction where the use of social media has proven very useful.

Will the digital gap between the analogical and the digital world, between immigrants and digital natives, between boomers and millennials grow? I don’t think so. Their coexistence will prevail and bring us the best of both worlds: hybrid meetings. If these two worlds were actually ever there…

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Pérez de Prado declared having received professional fees for his consultancy work or meetings held for iVascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, BBraun, and Abbott totally unrelated to this article; he is the current president of the education and learning organization Fundación Epic.

REFERENCES

1. Alkhouli M, Coylewright M, Holmes DR. Will the COVID-19 Epidemic Reshape Cardiology? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:217-220.

2. Sandars J, Correia R, Dankbaar M, et al. Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish. 2020. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1.

3. PCR e-Course 2020. Thanks to the 15,000+online learners. 2020. Available online:https://www.pcronline.com/Courses/PCR-e-Course. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

4. European Society of Cardiology. ESC Congress 2020 ? The Digital Experience. A record-breaking event:125,000 healthcare professionals from 213 countries. Available online:https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-%26-Events/ESC-Congress. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

5. European Society of Cardiology. Figures from ESC Congress ? Statistics from the world's largest cardiovascular congress. Participation 2015-2019. Available online:https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-&-Events/ESC-Congress/About-the-congress/Figures-from-ESC-Congress. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

6. Margolis A, Balmer JT, Zimmerman A, López-Arredondo A. The Extended Congress:Reimagining scientific meetings after the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish. 2020. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000128.1.

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is one of the most prevalent valvular heart diseases in the world.1 Although surgical mitral valve replacement has shown to improve clinical outcomes in patients with severe primary MR, surgery is still being denied in a significant number of patients due to their multiple clinical comorbidities.2 The current clinical practice guidelines for the management of severe secondary MR recommend the surgical valve intervention only in cases where concomitant coronary revascularization is indicated.3

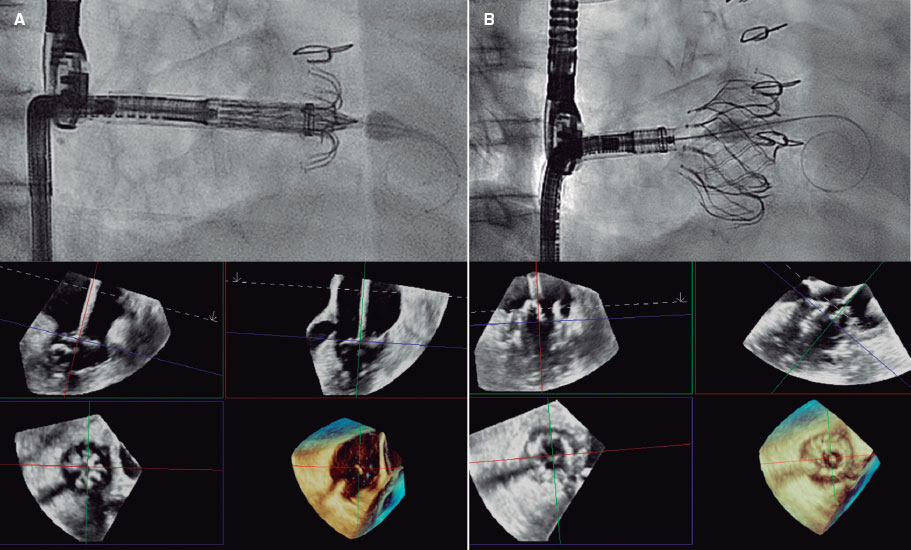

Transcatheter mitral valve repair using the edge-to-edge technique (MitraClip, Abbott Menlo Park, CA, United States) has shown to improve quality of life and reduce all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure and secondary MR refractory to the optimal medical treatment.4 However, the level of MR reduction achieved by MitraClip is inferior compared to the surgical techniques, and its overall use is limited by several anatomical factors.5 Transcatheter mitral valve implantation is emerging as a potential therapeutic alternative that could overcome some of the current limitations of edge-to-edge repair.6 Due to their technical design features, most transcatheter mitral valve implantation systems use the surgical transapical approach. Limited experience has been gathered on the use of dedicated transseptal systems. Finally, complex anatomical features such as the possibility of left ventricular outflow tract obstruction and presence of mitral annular calcification have limited the fast clinical adoption of this technology.

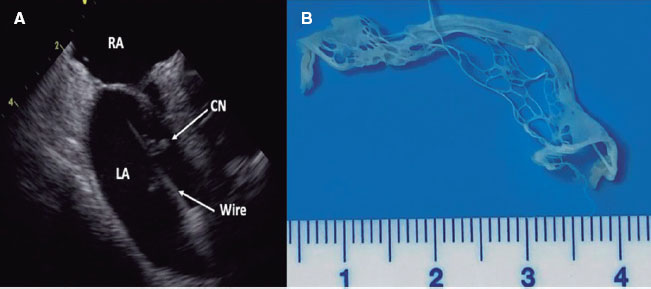

The field of catheter-based mitral valve intervention is rapidly expanding, and translational experimental models are seriously needed for the proper validation of these technologies. Unlike aortic valve disease, MR is due to several pathological conditions that result in different anatomical substrates that are not easy to reproduce in experimental models. Catheter-based technologies are designed taking into consideration specific anatomical targets such as annular dilatation or chord elongation, which are also challenging to reproduce in experimental animal models. Significant differences exist between humans and animal models. In the first place, one of the most important challenges we face is annular size. Devices developed for human use are typically larger compared to the annulus seen in common experimental models, which at times, requires developing customized valve sizes. Secondly, the aortomitral curtain is particularly small, which often leads to device interaction with the aortic valve. Thirdly, the mitral tissue is thin and friable providing little support to technologies that require the use of anchors or pads to remain in position. Finally, the left atrium is flat and shallow and provides little room for the validation of technologies via transseptal access.

The use of diseased animal models is not typically required to validate structural heart technologies and most of the validation work can be done on the bench or on healthy animal models. Healing and thrombogenicity of valve materials is particularly important and can be validated in healthy animals. The stability of the frame and durability of the leaflets can also be tested and is of particular significance in the transcatheter mitral valve implantation space. The mechanism of the deployment and delivery system can also be tested but, overall, the retention of the valve depends on the mechanism of anchoring used, which could be challenging due to the lack of structural support. In these cases, the surgical placement of the valves is needed for the long-term stability of the implant.

The use of diseased animal models is often spared to assess the efficacy of the device or test particular device features (ie, anchoring). Several animal species, primarily dogs suffer from primary MR due to leaflet prolapse and have been used to test several catheter-based technologies.7 However, these models are expensive and difficult to provide. Several groups have already developed secondary MR models by inducing ischemia of the posteromedial papillary muscle.8,9 These models have resulted in a high periprocedural mortality rate and moderate levels of clinically relevant MR. The study conducted by Rodríguez-Santamarta et al. recently published on REC: Interventional Cardiology presents a variation of this model by adding volume overload and creating an aorto-pulmonary fistula following the myocardial infarction of the circumflex artery.10 The number of animals was small, but researchers were able to prove the feasibility of model development. In this study, the level of MR was moderate (at most) and other features associated with MR such as annular dilatation were present. These morphological features, although obvious on the image assessment, were subtle in nature and probably in their early stages compared to patients who suffer from severe MR.

The field of structural heart procedures is changing very rapidly, and experimental models are essential for the proper validation of these technologies. Healthy animal models are perhaps enough to test the mechanism of the device delivery system, healing, and durability. Diseased animal models can help validate device efficacy, mechanisms of anchoring, and the long-term stability of the device. However, due to the high anatomical variability seen in humans compared to animals, long-term results may be confusing and require careful analysis by multidisciplinary teams before starting the first tests in humans. A multi-modality approach is highly desirable in the validation process of structural heart technologies. Although animal data are key, proper validation including human tissue and imaging correlation studies may help minimize the misinterpretation of experimental signals and define the developmental pathway of structural heart technologies.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. Granada is co-founder of Cephea Valve Technologies.

REFERENCES

1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases:a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005-1011.

2. Mirabel M, Iung B, Baron G, et al. What are the characteristics of patients with severe, symptomatic, mitral regurgitation who are denied surgery?Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1358-1365.

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Fleisher LA, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:1159-1195.

4. Stone GW, Lindenfeld JA, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307-2318.

5. Boekstegers P, Hausleiter J, Baldus S, et al. Percutaneous interventional mitral regurgitation treatment using the Mitra-Clip system. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:85-96.

6. Del Val D, Ferreira-Neto AN, Wintzer-Wehekind J, et al. Early Experience With Transcatheter Mitral Valve Replacement:A Systematic Review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013332.

7. Morgan KRS, Monteith G, Raheb S, Colpitts M, Fonfara S. Echocardiographic parameters for the assessment of congestive heart failure in dogs with myxomatous mitral valve disease and moderate to severe mitral regurgitation. Vet J. 2020;263:105518.

8. Pasrija C, Quinn RW, Alkhatib H, et al. Development of a Reproducible Swine Model of Chronic Ischemic Mitral Regurgitation:Lessons Learned. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;111:117-125.

9. Hamza O, Kiss A, Kramer AM, Tillmann KE, Podesser BK. A novel percutaneous closed chest swine model of ischaemic mitral regurgitation guided by contrast echocardiography. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:e518-e522.

10. Rodríguez-Santamarta M, Estévez-Loureiro R, Pérez Martínez C, et al. Experimental model of mitral regurgitation in a porcine model. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;1:12-18.

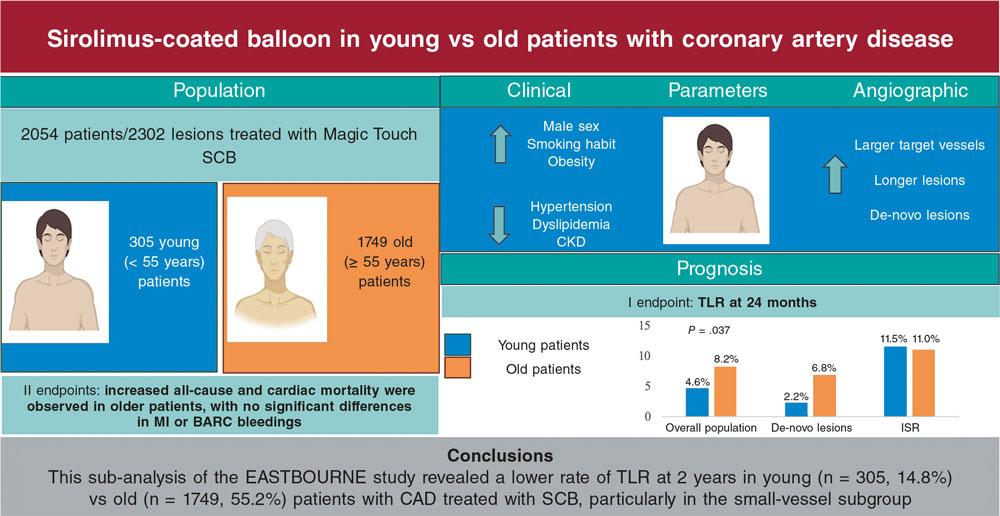

According to data from the National Statistics Institute, life expectancy has increased from 73.5 years in 1975 to 83.6 years in Spain in the year 2019. Also, the mean age of the population has gone up 10 years during this same period.1 In this sense, the results from the study conducted by Dégano et al.2 in 2013 come as no surprise. They already anticipated a strong increase in the rate of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) within the next 35 years when the Spanish population > 75 years will represent almost a quarter of the national census. This study anticipated that between 2013 and 2049, the cases of ACS in elderly patients would increase over 70%, but keep a discrete growth in patients under 75 years. These data are but a glimpse of a not so distant future when our patients will be older and their life expectancy longer. Also, the association between aging and comorbidity means that we will have to treat more complex patients.

Elderly patients with comorbidities are misrepresented in clinical trials studying the efficacy of both early invasive strategy for the management of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS) and the most suitable antithrombotic treatment.3 Therefore, despite the fact that clinical practice guidelines recommend early invasive strategy in most patients,4 its generalization to these patients is controversial. It is often decided to individualize the decision-making process by weighing risks and benefits and taking into consideration the treating physician’s perception on the possible complications. Hence, conducting clinical trials focused on this subpopulation as creating large registries representative of the actual clinical practice is of paramount importance.

In an article recently published by Pernias et al.5 on REC: Interventional Cardiology, the authors present a wide registry of elderly patients with NSTEACS conducted thanks to the collaborative work of different cardiology units from several Spanish autonomous communities. With over 7000 patients included, this study evaluated the impact of comorbidities on the indication to perform coronary angiographies. The 6 comorbidities studied (cerebrovascular disease, anemia, kidney disease, peripheral arteriopathy, chronic pulmonary disease, and diabetes mellitus) turned out to be independent predictors of a non-invasive approach. Also, it was confirmed that patients with more comorbidities had lower the chances of undergoing an invasive strategy despite having higher GRACE scores.

The comorbidities reported in this study are associated with a worse prognosis in this clinical setting.6 However, this does not necessarily involve low short-term life expectancy per se. Therefore, given the futility of an eventual revascularization a conservative strategy would not be justified. This clearly shows the need for a proper comprehensive geriatric assessment of these patients, since the accumulation of concomitant comorbidities is often followed by frailty, cognitive impairment, and functional dependency. These variables are key finding out why there is a paradoxically reverse correlation in these patients between the risk of ischemic events and the frequency of performing coronary angiographies. In this sense, we should mention the LONGEVO-SCA, a registry conducted in our setting that studied in detail the impact of frailty and geriatric syndromes on the therapeutic approach and vital prognosis of elderly patients with NSTEACS. Important conclusions can be drawn from this registry, like the negative impact of frailty both on the prognosis of elderly patients with NSTEACS and on the benefits of an invasive strategy.7,8

The usefulness of the invasive strategy in elderly patients is not well established. The randomized clinical trial After Eighty included 457 patients > 80 years with non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). It confirmed a lower incidence rate of the composite endpoint of death or cardiovascular events at the 1.5-year follow-up with the invasive strategy.9 However, this clinical trial did not consider frailty and included less than 25% of the possible candidates, indicative of bias in favor of elderly patients in better general health conditions and with fewer comorbidities.9 The MOSCA clinical trial10 included 106 elderly patients with NSTEMI and comorbidities. Although there were fewer chances of death or ischemic events in this study at the 3-month follow-up in patients randomized to the invasive strategy, no benefits were seen with this strategy at the end of the follow-up (2.5 years).

Currently underway, the MOSCAFRAIL clinical trial11 will assess the efficacy and safety of the invasive strategy and its prognostic effect within the first year after NSTEMI in elderly patients with confirmed frailty. This trial, that included over 10 tertiary and secondary Spanish hospitals, is a systematic geriatric and comorbidity study conducted with widely validated scales. Its results should provide valuable information and greatly impact clinical practice in the coming future.

Another controversial issue with studies of elderly patients with ACS is what clinical outcomes should be assessed. Most randomized and observational studies focus on “traditional” clinical outcomes like mortality or ischemic events. However, on many occasions there are no data on the impact on symptoms, perceived quality of life, and need for readmission, which may indicate better the clinical benefits of this population. In this sense, we should mention the After Eighty clinical trial found no differences regarding quality of life between patients treated with the invasive strategy and those treated conservatively.12

In conclusion, elderly patients with high comorbidities who are hospitalized due to NSTEACS are a common problem today and will remain so in the future. Given the scarce scientific evidence on the therapeutic approach of these patients, studies like the one conducted by Pernias et al.5 improve our understanding of this complicated clinical scenario and remind us of the importance of collaborative research to conduct large registries that show the reality of this emerging problem in our setting.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Edad Media de la Población por provincia, según sexo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Datos.htm?t=3199#!tabs-tabla. Accessed 11 Jul 2020.

2. Dégano IR, Elosua R, Marrugat J. Epidemiología del síndrome coronario agudo en España:estimación del número de casos y la tendencia de 2005 a 2049. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:472-481.

3. Tahhan AS, Vaduganathan M, Greene SJ, et al. Enrollment of Older Patients, Women, and Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups in Contemporary Acute Coronary Syndrome Clinical Trials:A Systematic Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:714-722.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet J-P, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315.

5. Pernias V, García Acuña JM, Raposeiras-Roubín S. Influencia de las comorbilidades en la decisión del tratamiento invasivo en ancianos con SCASEST. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:19-24.

6. Canivell S, Muller O, Gencer B, et al. Prognosis of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular multimorbidity after acute coronary syndrome. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195174.

7. Alegre O, Formiga F, López-Palop R, et al. An Easy Assessment of Frailty at Baseline Independently Predicts Prognosis in Very Elderly Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19:296-303.

8. LlaóI, Ariza-SoléA, Sanchís J, et al. Invasive strategy and frailty in very elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e336-e342.

9. Tegn N, Abdelnoor M, Aaberge L, et al. Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study):An openlabel randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;387:1057-1065.

10. Sanchis J, Núñez E, Barrabés JA, et al. Randomized comparison between the invasive and conservative strategies in comorbid elderly patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. Eur J Intern Med. 2016;35:89-94.

11. Sanchis J, Ariza-SoléA, Abu-Assi E, et al. Invasive Versus Conservative Strategy in Frail Patients With NSTEMI:The MOSCA-FRAIL Clinical Trial Study Design. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:154-159.

12. Tegn N, Abdelnoor M, Aaberge L, et al. Health-related quality of life in older patients with acute coronary syndrome randomised to an invasive or conservative strategy. The After Eighty randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2018;47:42-47.

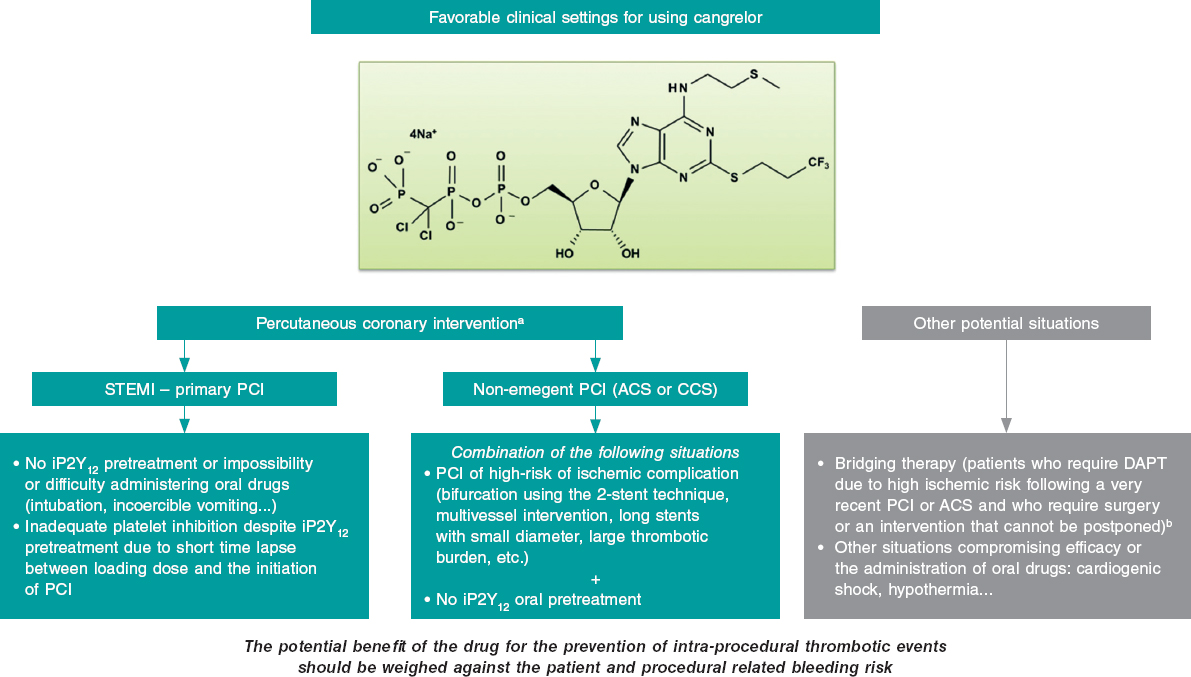

During the second half of 2019, cangrelor started selling in our country, a “new” antiplatelet drug with especial pharmacological properties that make it especially appealing for the management of certain clinical situations in the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) setting. The adjective “new” is in quotation marks because the clinical trial conducted proved its superiority compared to clopidogrel with ICP. The CHAMPION PHOENIX trial1 was published in 2013 and it was approved by regulatory authorities back in 2015. This delay has probably caused the scientific evidence to lose relevance and, in consequence this drug might not be widely accepted within the cardiology community. Also, the indication specified in the technical label is only based on the conditions of the clinical trial that prompted its approval—which is mandatory—not on real-world practices. This may be confusing when selecting those patients who may benefit from this drug.2

In short, cangrelor is an intravenous reversible, high-affinity antagonist of the platelet P2Y12 receptor of adenosine diphosphate to which it binds directly (without need for conversion into an active metabolite). In pharmacodynamic terms, the properties of cangrelor are: a) rapid onset of action (3 to 6 minutes); b) powerful dose-dependent effect (inhibition > 90% of the P2Y12 receptor signaling pathway) in relation to the dose used in the PCI; and c) rapid offset of action (shot half-life of 3 to 5 minutes) with recovery of the baseline platelet function in 60 to 90 minutes after infusion.3

Given its pharmacological properties, cangrelor may help solve some of the problems posed by other antiplatelet agents. For example, oral P2Y12 receptor inhibitors (iP2Y12), especially clopidogrel and to a lesser extent prasugrel and ticagrelor, have a delayed optimal platelet inhibition, which is even more significant in the ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) setting, where the bioavailability of oral drugs may be compromised (worse intestinal absorption, vomiting, use of opioids or situations like intubation, therapeutic hypothermia or cardiogenic shock).3,4 Also, despite their efficacy in reducing thrombotic events, the use of parenteral glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, may be associated with a higher risk of bleeding.

The clinical development of cangrelor as a coadjuvant therapy in the PCI setting is based on the CHAMPION program, in which the first 2 studies conducted (CHAMPION PCI5 and CHAMPION PLATFORM6) were prematurely interrupted due to their futility, in part attributed to a restrictive definition of myocardial infarction.3,7 On the contrary, the CHAMPION PHOENIX clinical trial did prove the superiority of cangrelor vs clopidogrel reducing the main variable of efficacy (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, ischemia guided revascularization or stent thrombosis) after 48 hours in patients who underwent PCI to treat stable angina or any type of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and who were not eligible for oral iP2Y12 pretreatment.1 We should mention that in a combined analysis of the 3 trials, cangrelor was associated with a slightly higher risk of bleeding mainly at the cost of minor bleeding;8 this good safety profile is probably due to the fact that the drug is administered over a very limited span of time and its effect rapidly goes away after infusion.

The CHAMPION PHOENIX trial has received 2 important criticisms that may condition its implementation in our routine clinical practice. The first is that cangrelor was never compared to prasugrel or ticagrelor (more powerful and effective than clopidogrel and drugs of choice in patients with ACS). The second is that iP2Y12 pretreatment before the PCI was considered an exclusion criterion. We should remember that, although there are serious doubts about its pretreatment benefit in the ACS setting, especially in the non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome setting,9 this strategy is widely used in our country. As a matter of fact, the European technical label of this drug specifically says that cangrelor is indicated in association with acetylsalicylic acid in patients “who undergo PCI and have not received an oral P2Y12 inhibitor before the PCI, and in whom oral treatment with P2Y12 inhibitors is not possible or desired”.2 Still, the pharmacological properties of cangrelor make it especially interesting in situations where not only the aforementioned pretreatment has not occurred, but also in circumstances where it is considered insufficient. Proof of this is the experience published from the Swedish national registry (SCAAR) during the first 2 years of drug use that found an almost exclusive use of cangrelor in patients with STEMI who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention; in this real-world study, cangrelor was combined with ticagrelor mainly, although the latter had already been administered in over 50% of the times in the prehospital setting, which is why in such cases the use of cangrelor would be considered an off-label indication.10

The clinical settings where, in our opinion, cangrelor can be useful both in the PCI setting (most of the cases) and in other situations are shown on figure 1. The most relevant setting would be the primary percutaneous coronary intervention in the management of STEMI, where its use is appropriate in the absence of proper pretreatment with iP2Y12 due to the impossibility or difficulty administering oral drugs (intubation or incoercible vomiting); it may also be considered if the loading dose of iP2Y12 is ineffective during the procedure (short span of time elapsed from its administration until the PCI is performed). Another acceptable situation (much less common than the latter) would be non-emergent high-risk PCIs (such as bifurcations using the dual stent technique, multivessel interventions, in the presence of great thrombotic load, etc.) in patients without iP2Y12 pretreatment. In any case, the drug potential benefit should always be weighed to prevent intraprocedural thrombotic events associated with the procedure and the patient’s bleeding risk. Also, we should remember that the use of cangrelor is ill-advised if glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors are going to be administered.

Figure 1. Potential favorable clinical settings for the use of cangrelor. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; iP2Y12, platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibitors; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment-elevation acute myocardial infarction.

a) The dose in the percutaneous coronary intervention setting should be 30 µg/kg in bolus followed by an infusion at rate of 4 µg/kg/min.

b) The dose studied in the bridging therapy is an infusion of 0.75 µg/kg/min.

Other relevant aspects are the duration of infusion that can be reasonably maintained for at least 2 hours after the PCI. According to the drug technical label, it should be started before the procedure and the infusion lasting at least 2 hours or for as long as the pro- cedure lasts, which ever is longer. Still, this may not be enough in situations where the oral drugs early action is delayed. Also, special care is needed when transitioning to oral drugs; in general, the recommendation here is that ticagrelor can be administered at all times (before, during or after infusion) while thienopyridines can be prescribed after infusion (to avoid an interaction that would imply a time lapse without the proper antiplatelet therapy).3

Taking all this into consideration, cangrelor should be primarily used in the cath lab in situations of periprocedural high thrombotic risk when oral iP2Y12 pretreatment has not occurred, is ill-advised or insufficient. The availability of the drug will probably not change our antiplatelet strategy radically in the short term in the PCI setting. However, in some situations (especially primary percutaneous coronary interventions) its particular pharmacological profile will be very useful. Therefore, its use will probably grow in the interventional cardiology community as we become more familiar with it. In conclusion, cangrelor is an interesting addition to our therapeutic armamentarium in the PCI setting because it can individualize and, therefore, optimize our antithrombotic strategy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.L. Ferreiro has declared he has received funds for his lectures for Eli Lilly Co., Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., AstraZeneca, Roche Diagnostics, Pfizer, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Ferrer; also, he has received funds for his counselling for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Co., Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc., Bristol-Myers Squibb; he has also receive research grants from AstraZeneca. J.A. Gómez-Hospital has declared he has received funds for his counselling for Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Terumo, and IHT.

REFERENCES

1. Bhatt DL, Stone GW, Mahaffey KW, et al. Effect of platelet inhibition with cangrelor during PCI on ischemic events. N Engl J Med. 2013;368: 1303-1313.

2. Kengrexal. Technical label or summary of product characteristics. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/pdfs/es/ft/115994001/FT_115994001.pdf. Accessed 18 May 2020.

3. Marcano AL, Ferreiro JL. Role of New Antiplatelet Drugs on Cardiovascular Disease: Update on Cangrelor. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2016;18:66.

4. Ferreiro JL, Sánchez-Salado JC, Gracida M, et al. Impact of mild hypothermia on platelet responsiveness to aspirin and clopidogrel: an in vitro pharmacodynamic investigation. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2014;7:39-46.

5. Harrington RA, Stone GW, McNulty S, et al. Platelet inhibition with cangrelor in patients undergoing PCI. N Engl J Med. 2009;361: 2318-2329.

6. Bhatt DL, Lincoff AM, Gibson CM, et al. Intravenous platelet blockade with cangrelor during PCI. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2330-2341.

7. White HD, Chew DP, Dauerman HL, et al. Reduced immediate ischemic events with cangrelor in PCI: a pooled analysis of the CHAMPION trials using the universal definition of myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2012;163:182-190.e4.

8. Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Hamm CW, et al. Effect of cangrelor on periprocedural outcomes in percutaneous coronary interventions: a pooled analysis of patient-level data. Lancet. 2013;382:1981-1992.

9. Ferreiro JL. Pre-Treatment With Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: Does One Size Fit All? JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:918-920.

10. Grimfjärd P, Lagerqvist B, Erlinge D, Varenhorst C, James S. Clinical use of cangrelor: nationwide experience from the Swedish Coronary Angiog raphy and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2019;5:151-157.

The introduction of endomyocardial biopsy (EMB) for the diagnosis of rejection back in 19721 was considered one of the main advances in the history of heart transplant (HT). Ever since, the EMB has been the gold standard for the diagnosis of rejection. However, this is a repetitive, invasive procedure, often described as uncomfortable by patients and associated with sometimes, serious complications. In this context, in a recent article published on REC: Interventional Cardiology, Tamargo et al.2 shared their combined experience from 2 large national HT centers with the use of EMB via brachial access, a route that is relatively less invasive compared to the femoral access or the most common jugular vein. The authors prove that this is a feasible alternative in 94% of the attempts. Brachial access is safer because it is not associated with some of the major complications of central venous access (mainly pneumothorax and arterial puncture). However, brachial access does not affect the main complication of EMB in the mid-long term: traumatic tricuspid regurgitation occurring after repeated biopsies that can be serious and symptomatic enough to require surgical correction.3 Although brachial access does not reduce procedure time and fluoroscopy time is longer compared to jugular access, it seems evident that this access appears to be more comfortable for patients (although this is based on the testimony of only 19 patients as the authors admit in the limitations section). Therefore, the procedure described is especially appropriate for patients with HT, who represent the largest part of their series and in whom the repeated use of follow-up EMBs is widely accepted as a screening method for graft rejection.

In any case, we should mention that although the EMB still keeps its aura as the gold standard for the diagnosis of rejection, the lack of scientific evidence on this regard is astonishing. In the current era of evidence-based medicine and despite the fact that we have been using this technique for the last 30 years, there is no solid scientific evidence establishing its actual role in the management of patients. In the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation clinical practice guidelines,4 systematic EMB for the detection of rejection has a weak recommendation (level IIa) with the lowest possible level of evidence (class C) and with no back up from scientific references.

Also, the histological interpretation of an EMB is rather subjective, the diagnostic criteria have been changed several times, and there is an alarming inter-observer variability.5,6 Actually, its sensitivity and specificity are completely unknown. On the other hand, all HT groups have experienced the frustration of obtaining repeated false positives7 and false negatives8 to the point that there is often little correlation between the anatomopathological degree of rejection and the functional situation of patient and graft.

Therefore, we are not surprised by the numerous attempts to replace EMB with other non-invasive techniques, mainly echocardiographic. Results have been widely variable and they have never been implemented in the real clinical practice.9 Over the last few years, sophisticated techniques like gene expression profiles have been introduced. However, they have only been applied to selected patients (low risk of rejection) and relatively late after the HT (> 2 months to 6 months), which in practice excludes most clinically relevant rejection episodes.10,11

The main problem of these attempts to replace EMB with non-invasive techniques is that we are comparing these new diagnostic approaches to EMB assuming that EMB is the gold standard. However, this argument is wrong from the beginning because this supposed gold standard is not such. To consider the EMB as the gold standard, the current standards of evidence-based medicine should be applied to undisputedly show that the current practice of systematic follow-up with periodic EMBs and histology-based treatment does actually improves clinical results.

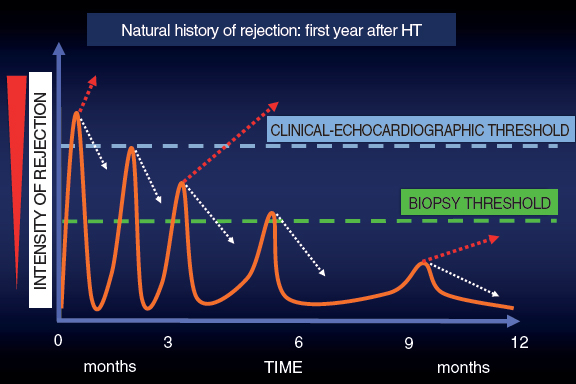

In this context and given the uncertainties due to the frequent false positives and negatives obtained by the EMB, back in the 1990s here at Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla we developed a periodic clinical-echocardiographic follow-up strategy without performing mandatory EMBs.12 Our strategy is based on this idea: as time goes by after the HT, the episodes of rejection are less aggressive and more spaced-out. Many subside spontaneously, but others may progress until they compromise the function of the graft and are detected either clinically or on the echocardiography. Although we lose diagnostic sensitivity, with this strategy we achieve great clinical specificity because we are only identifying episodes of rejection that do not subside spontaneously (a minority according to experience) and that often respond well to treatment (figure 1).

Figure 1. Graphic representation of the natural evolution of rejection within the first year after a heart transplant. The episodes of rejection are less intense and frequent across time. The dotted white arrows indicate spontaneous resolution of rejection thanks to baseline immunosuppression. The dotted red arrows indicate the continuous evolution of rejection.

Therefore, in these periodic reviews we conduct clinical assessments and obtain follow-up echocardiograms without mandatory EMBs that are only performed in suspected cases. Since we are looking for specificity, we only assess “hard” echocardiographic endpoints (relevant changes in wall thickness or a reduced ejection fraction) suggestive of rejection that warrant treatment. We decide not to use other techniques like strain, which is much more sensitive and would make us lose specificity.

After a 30-year experience and some 600 HTs performed, the use of EMB is marginal in our program.13 The historic mean is 1.24 EMBs per patient, but over the last 10 years it has gone down to only 0.2. In our routine clinical practice we do not perform any EMBs at 1-year follow-up in most patients. Our confidence in this strategy is based on the clinical results that hold a favorable comparison to those of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry14 both in the mid and long term. If we exclude the first week after the HT (a time when EMBs are rarely performed), the actual survival rate of Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla is 85% at 1-year follow-up, 75% at 5-year follow-up, and 61% at 10-year follow-up, which is slightly higher compared to that of the Spanish Heart Transplant Registry14 (84% at 1-year follow-up, 73% at 5-year follow-up, and 58% at 10-year follow-up).

In any case, the brachial vein access suggested by Tamargo et al.2 is a warmly welcomed proposal, especially by the patients. Following the classic Stanford Protocol15 a minimum of 14 EMBs should be performed per patient within the first year. This means that the better tolerance shown to this procedure, which is associated with fewer acute complications, can be very relevant for patients given the large number of biopsies they will need to undergo during follow-up.

Several aspects of the current HT management are based on expert opinions and clinical inertia rather than on scientific evidence. Among them, the myth that the EMB is the gold standard should not be accepted given the lack of evidence supporting it. We believe it is important to move forward in this field, but to do so non-invasive alternatives to EMB should change their current approach. Instead of comparing their diagnostic capabilities to those of the EMB (wrong gold standard), they should rather be based on comparing clinical results, which is ultimately what matters. Therefore, we believe that the time has come to design randomized clinical trials comparing clinical results among the different strategies to reduce the use of EMB based on non-invasive methods and review the traditional rule of performing mandatory EMBs.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Caves PK, Stinson EB, Billingham M, Shumway NE. Percutaneous transvenous endomyocardial biopsy in human heart recipients. Experience with a new technique. Ann Thorac Surg. 1973;16:325-336.

2. Tamargo M, Gutiérrez Ibañes E, Oteo Domínguez JF, et al. Endomyocardial biopsy using the brachial venous access route. Description of the technique and 12-year experience at 2 different centers. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M20000110.

3. Alharethi R, Bader F, Kfoury AG, et al. Tricuspid valve replacement after cardiac transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:48.

4. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. Task Force 2:Immunosuppression and Rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:914-956.

5. Marboe CC, Billingham M, Eisen H, et al. Nodular endocardial infiltrates (Quilty lesions) cause significant variability in diagnosis of ISHLT Grade 2 and 3A rejection in cardiac allograft recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24:S219-S226.

6. Crespo-Leiro MG, Zuckermann A, Bara C, et al. Concordance among pathologists in the second Cardiac Allograft Rejection Gene Expression Observational Study (CARGO II). Transplantation. 2012;94:1172-1177.

7. Winters L, Loh E, Schoen F. Natural History of Focal Moderate Cardiac Allograft Rejection. Is Treatment Warranted?Circulation. 1995;91:1975-1980.

8. Fishbein MC, Kobashigawa J. Biopsy-negative cardiac transplant rejection:etiology, diagnosis and therapy. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:166-169.

9. Badano LP, Miglioranza MH, Edvardsen T, et al. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging/Cardiovascular Imaging Department of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology recommendations for the use of cardiac imaging to assess and follow patients after heart transplantation. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:919-948.

10. Pham MX, Teuteberg JJ, Kfoury AG, et al. Gene expression profiling for rejection surveillance after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1890-1900.

11. Crespo-Leiro M, Stypmann J, Schulz U, et al. Clinical usefulness of gene-expression profile to rule out acute rejection after heart transplantation. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2591-2601.

12. Vázquez de Prada JA. Revisión crítica del papel de la biopsia endomiocárdica en el trasplante cardíaco. Rev Esp Cardiol. 1995;48(Supl 7):86-91.

13. Vázquez de Prada JA, Gonzalez Vilchez F, Rodriguez Entem F, et al. Heart Transplantation without Routine Endomyocardial Biopsies Is Feasible:Experience with a Clinical-Echocardiographic Strategy [abstract]. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2016;35(4S):S32-S33.

14. González-Vílchez F, Almenar-Bonet L, Crespo-Leiro MG, et al. Registro español de Trasplante Cardiaco. XXX Informe oficial de la Sección de Insuficiencia Cardiaca de la SEC (1984-2018). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:954-962.

15. Billingham ME. Diagnosis of cardiac rejection by endomyocardial biopsy. Heart Transplant.1981;1:25-30.

- Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: new insights on diagnosis and management

- Transcatheter mitral valve replacement: there is no one-size-fits-all solution

- Scientific debates among professionals in social media: a fantastic, but not risk-free scenario

- Drug-coated balloon catheters. Discussing mortality from the coronary perspective

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

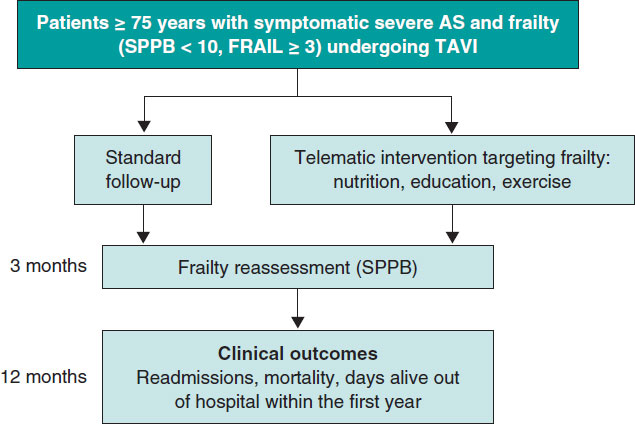

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España