Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

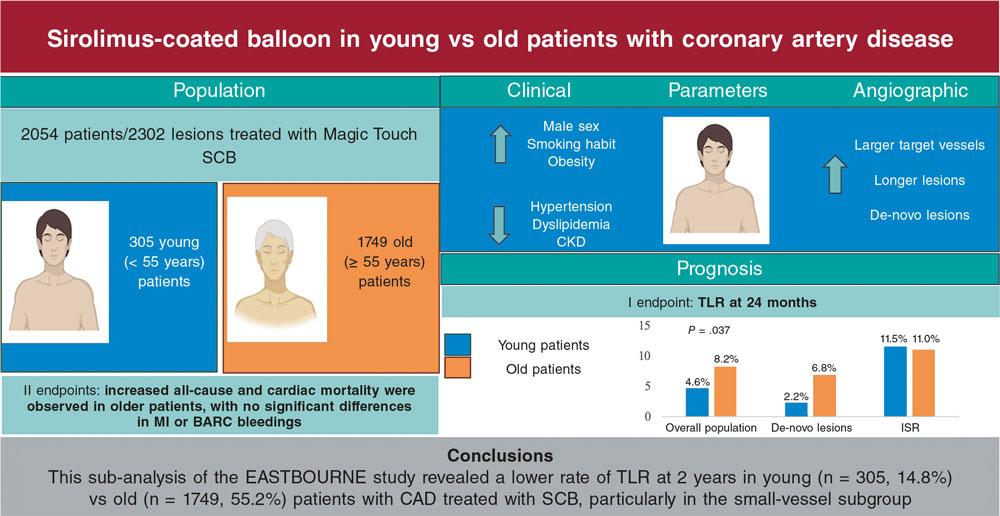

The management of symptomatic coronary artery disease in older adults presents a conundrum. Depending on their residual life expectancy, treatment is focused more on quality of life and symptomatic relief than on the improvement of long-term prognosis. Consequently, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) often is not an option, not only because of an increased and sometimes prohibitive risk but also because of the slow or even incomplete recovery after major surgery in older adults. On the other hand, medical treatment alone is of limited efficacy and may result in polypharmacy, with associated problems of adherence and drug interaction. Thus, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) may remain the only reasonable option. Nevertheless, PCI in older adults is often technically challenging and carries a substantially increased risk compared with PCI in younger patients.1 The extent and location of coronary artery disease appear to be even more important in older adults than in younger patients. Specifically, the risk of PCI in older patients is increased by more than twofold, if it involves the left main coronary artery as compared with PCI in other territories.1

Thus, guidance on left main PCI in older adults is particularly needed. There is, however, a paucity of data to aid treatment decisions in this setting. Older age groups are scarcely represented in the randomized trials that inform current guidelines.2 As a first approach to this problem, it may be important to learn how the outcomes of left main PCI in older adults differ from those in the younger age groups included in pivotal trials.

The study by Gallo et al.,3 recently published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, is an important first step in this direction. This retrospective, single-center observational study investigated all older adult (≥ 75 years) patients undergoing left main PCI at the Cardiology Service of the Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Córdoba, Spain) between 2017 and 2021. Gallo et al. identified 140 patients with a median age of 80 years and a median SYNTAX score of 21, similar to those in published randomized studies. Highlighting the clinical relevance of the issue, these patients represented as much as 32% of their left main PCI cohort.

With a median follow-up of 19 months (interquartile range, 5-35 months), Gallo et al. found substantial differences in outcomes for their left main PCI cohort of older adults compared with published outcomes in pivotal randomized trials comparing left main PCI with CABG (figure 1). In these trials, patients had to be eligible for CABG and were approximately 14 years younger.4 As shown by a recent individual patient data meta-analysis, outcomes in the pivotal trials were driven by nonfatal cardiac events rather than mortality.4 In the current cohort of Gallo et al., however, only 2.1% had a spontaneous nonfatal myocardial infarction during the 2-year follow-up and reintervention was indicated in only 4.3%, whereas 2-year mortality was 27.1%.3

Figure 1. Two-year outcomes of left main percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in older adults in the study by Gallo et al.3 compared with younger patients included in randomized studies comparing PCI with coronary artery bypass grafting.4 Percentages were derived from numbers of events divided by total number of patients for older adults and from Kaplan-Meier estimates for younger patients. The incidence of noncardiovascular death in younger patients was imputed based on the reported proportion of 44% for noncardiovascular death at 5 years. MI, myocardial infarction.

The younger patients in the randomized trials had a substantially better prognosis with a 2-year mortality of only 4.5%. In these patients, outcomes were dominated by spontaneous myocardial infarction and reintervention, with 2-year incidences of 3.0% and 9.6%, respectively.4 According to the individual patient data meta-analysis, CABG substantially reduced these latter events—to 1.6% and 3.4%, respectively—but did not significantly improve survival.

In this context, the results of the study by Gallo et al. are important. They show that the contribution of those events where CABG clearly outperforms PCI (ie, spontaneous myocardial infarction and reintervention) is less relevant in older adults than in the younger patients of the randomized trials.

In the population of older adults in the study by Gallo et al., deaths that could be clearly attributed to noncardiac causes were more frequent than in younger patients. The incidence of noncardiac death was 7.1% at the 2-year follow-up after left main PCI in older adults, while it ranged around 2% in the younger patients of randomized studies on left main PCI (figure 1). This indicates a higher number of deaths not amenable to any cardiovascular treatment in older patients compared with younger patients.

Although higher in absolute numbers, the proportion of deaths that could be attributed unequivocally to noncardiac causes was lower in older adults than in younger patients (figure 1). This finding is, however, difficult to interpret. In line with common practice, deaths of unknown cause were counted as cardiac deaths. Thus, we do not know how many of these deaths were from true cardiac causes, let alone what proportion of deaths were due to treatment failure of left main PCI.

Despite these uncertainties, the study by Gallo et al. shows that in older adults with left main PCI, the causes of death not related to myocardial revascularization were more frequent than in younger patients undergoing left main PCI.

Mortality was driven less by calendar age and more by frailty. Gallo et al. stratified their cohort into nonfrail and frail groups, as defined by a frailty score of 3 or higher. As many as 57% of the frail patients had died at the 3-year follow-up compared with 23% of the nonfrail patients (P = .001) (for 2-year mortality, see figure 1). After inverse probability of treatment weighting with a number of variables including age, this difference in all-cause mortality remained substantial and statistically significant (23 % vs 44%; P = .046). Thus, frailty, but not age or SYNTAX score, was a significant independent predictor of mortality (multivariable hazard ratio = 2.4; 95% confidence interval, 1.2-5.0; P = .018).These findings are in line with a recently published study on PCI in older adults that identified frailty, but not calendar age, as a strong predictor of mortality.5

The high mortality of older adults with left main coronary disease despite PCI poses the question of futility, particularly in frail patients. While PCI may indeed be futile in terms of prolonging life, it may still alleviate symptoms. In this regard, it is important to note that PCI in the study by Gallo et al. could be accomplished without complications in 94% of the patients (92% of frail patients and 97% of nonfrail patients), and 91% of the patients left the hospital alive, even though 50% of them had presented with acute myocardial infarction. Thus, there is no prohibitive complication rate that justifies withholding left main PCI in older adults as an attempt to improve symptoms. Moreover, the randomized After Eighty study found that myocardial revascularization reduced the risk of myocardial infarction and urgent revascularization in older patients with acute coronary syndromes.6 Thus, PCI in older adults, particularly for the left main, may offer more than just relief from angina or angina equivalents. The low incidences of spontaneous myocardial infarction and reintervention found by Gallo et al. after left main PCI may thus reflect the positive effects of the procedure. However, in the absence of a control group such interpretation remains speculative. Moreover, the number of patients in this retrospective observational study is limited. Together, with the single-center design of the study, this weakens the generalisability of the current findings.

Nevertheless, 3 important messages of the study by Gallo et al. prevail: a) left main PCI in older adults is a reasonable option with a fair procedural success rate; b) the clinical course after left main PCI differs substantially from that in younger patients with death being far more common than nonfatal cardiovascular events; c) frailty is more relevant to prognosis than calendar age, being a central determinant of mortality after left main PCI. Further studies are needed to determine how best to integrate these findings into individualized treatment decisions in older adults presenting with symptomatic left main disease.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

F.-J. Neumann has received consultancy honoraria from Novartis and Meril, speaker honoraria from Boston, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo and Meril and reports speaker honoraria paid to his institution from BMS/Pfizer as well as research grants paid to his institution from Boston and Abbott.

REFERENCES

1. Jalali A, Hassanzadeh A, Najafi MS, et al. Predictors of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events after percutaneous coronary intervention in older adults:a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2024;24:337-349.

2. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

3. Gallo I, Hidalgo F, González-Manzanares R, et al. Percutaneous treatment of the left main coronary artery in older adults. Impact of frailty on med-term results. REC Interv Cardiol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M24000460.

4. Sabatine MS, Bergmark BA, Murphy SA, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents versus coronary artery bypass grafting in left main coronary artery disease:an individual patient data meta-analysis. Lancet. 2021;398:2247-2257.

5. Shimono H, Tokushige A, Kanda D, et al. Association of preoperative clinical frailty and clinical outcomes in elderly patients with stable coronary artery disease after percutaneous coronary intervention. Heart Vessels. 2023;38:1205-1217.

6. Tegn N, Abdelnoor M, Aaaberge L, et al. Invasive versus conservative strategy in patients aged 80 years or older with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction or unstable angina pectoris (After Eighty study):an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;387:1057-1065.

In 1998, in response to a comment on the limited durability of an aortic valvuloplasty performed during the last Madrid Interventional Cardiology (MIC) course, Alain Cribier insightfully stated: “We’ll mount a stent on the valvuloplasty balloon, attach the leaflets, and problem solved.” Four years and countless hours of work later, both at his hospital in Rouen, France, and at the animal experimentation center in Lyon, France, the recently deceased Alain Cribier (1945-2024) achieved a groundbreaking milestone.1 On April 16, 2002, he performed the world’s first surgery-free transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), prolonging the patient’s life and revolutionizing heart valve surgery. This innovation dramatically improved the quality of life of a high percentage of patients with severe aortic stenosis who were ineligible for conventional heart surgery. Since then, more than a million patients have benefited from his technological innovation.

After this pivotal first case of TAVI,1 isolated procedures were performed in selected patients in the following years, with few technical variations, and all via antegrade access. While interventional cardiologists were enthusiastic and had high expectations, critics predicted apocalyptic disasters due to alleged complications, such as vascular complications, valve instability and migration, coronary occlusion, strokes, annular and aortic rupture, paravalvular regurgitation, and concerns about the durability of the valve. In 2006, the first clinical trials (REVIVAL2 in the United States and REVIVE3 in Europe) changed the procedure strategy. The adoption of retrograde access, facilitated by the versatility of a flexible carrier catheter, considerably simplified the technique and contributed to its widespread adoption.

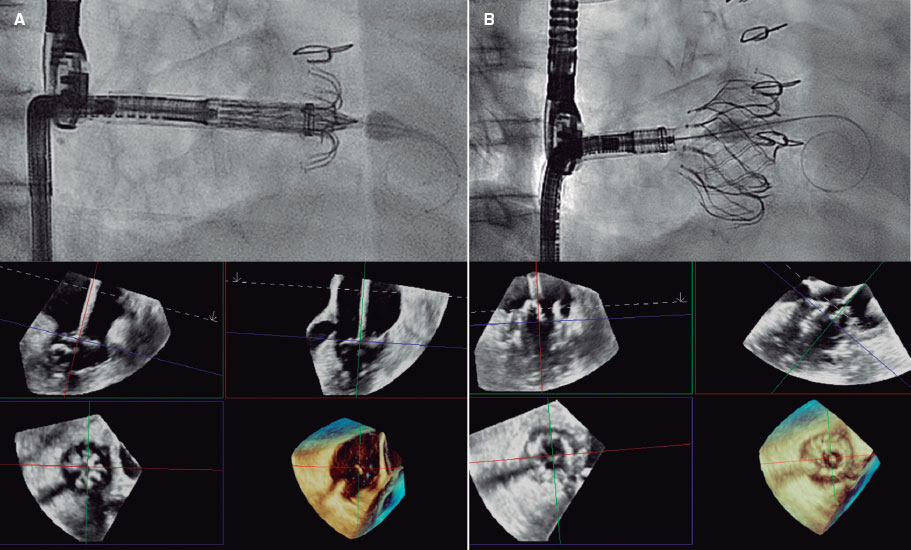

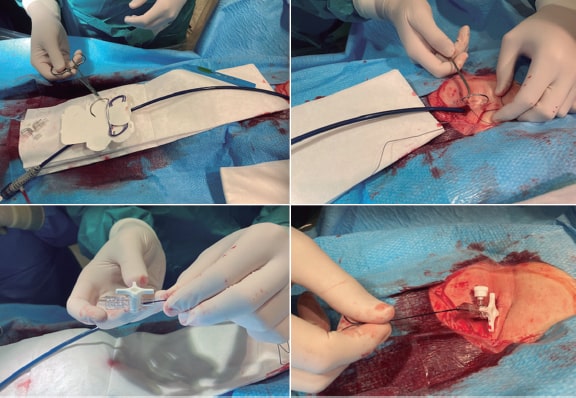

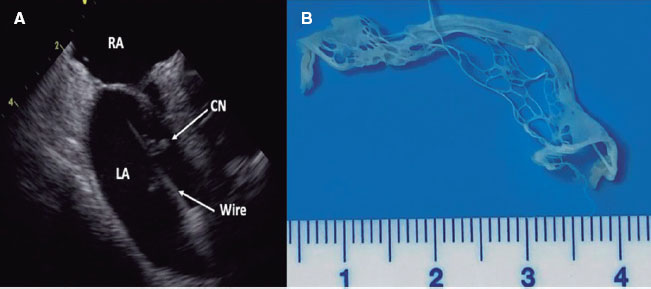

After a stay in Vancouver, Canada to acquire theoretical and practical training in the technique, and with Cribier’s assistance, a team of interventional cardiologists from Hospital Gregorio Marañón, Madrid, Spain successfully implanted the first 2 aortic valves via transfemoral access in Spain on April 23, 2007 (figure 1). Throughout 2007, the team contributed to the REVIVE trial, successfully treating 10 patients with transfemoral TAVI, with no perioperative mortality or major complications. This success, with contributions from other European centers, paved the way for the approval of this technology for clinical use.

Figure 1. First transcatheter aortic valve implantation performed in Spain, on April 23rd, 2007. In the photograph, from left to right, Dr. Alain Cribier, Dr. Eulogio García, and Dr. Javier Ortal.

After standardizing and defining the complications associated with the procedure,4 the randomized PARTNER clinical trials were conducted in inoperable patients and high-risk surgical patients.5,6 These trials confirmed the safety and efficacy of TAVI, establishing it as the treatment of choice for high-risk patients.7 Eventually TAVI became the preferred treatment for all patients with aortic stenosis older than 75 years.8-10

In this exciting journey, we contributed a few technical improvements, demonstrating the safety of direct implantation without prior valvuloplasty11 and improving the management of vascular access via contralateral access.12 The gradual simplification of TAVI led to its classification as a “minimally invasive procedure”. It is now available in all cath labs, with more than 1 million valves implanted in all 5 continents.13

Alain Cribier was technically elegant and efficient; meticulous, systematic, and generous in his teaching. His perseverance in the management of aortic stenosis drove him to seek a definitive solution. Bernard Guiraud-Chaumeil, former president of the French health assessment department, highlighted Cribier’s exceptional contribution to the management of valvular heart disease, stating: “Revolutionary advances in medicine must be accessible to patients as soon as possible.” Cribier’s dedication, perseverance, and ingenuity changed the history of severe aortic stenosis; his legacy will not only save thousands of lives but will also improve the clinical practice of present and future generations of interventional cardiologists.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis:First human case description. Circulation. 2002;106:3006-3008.

2. Kodali SK, O'Neill WW, Moses JW, et al. Early and late (one year) outcomes following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis (from the United States REVIVAL trial). Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1058-1064.

3. Garcia E, Pinto AG, Sarnago Cebada F, et al. Percutaneous Aortic Valve Implantation: Initial Experience in Spain. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:1210-1214.

4. Leon MB, Piazza N, Nikolsky E, et al. Standardized endpoint definitions for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation clinical trials:a consensus report from the Valve Academic Research Consortium. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:253-269.

5. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597-1607.

6. Schymik G, Heimeshoff M, Bramlage P, et al. A comparison of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and surgical aortic valve replacement in 1,141 patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and less than high risk. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:738-744.

7. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al.;ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739-2791.

8. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

9. Reardon MJ, Van Mieghem NM, Popma JJ, et al.;SURTAVI Investigators. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321-1331.

10. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

11. García E, Almería C, UnzuéL, Jiménez-Quevedo P, Cuadrado A, Macaya C. Transfemoral implantation of Edwards Sapien XT aortic valve without previous valvuloplasty:Role of 2D/3D transesophageal echocardiography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;84:868-876.

12. García E, Martín-Hernández P, UnzuéL, Hernández-Antolín RA, Almería C, Cuadrado A. Usefulness of placing a wire from the contralateral femoral artery to improve the percutaneous treatment of vascular complications in TAVI. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014;67:410-412.

13. Akodad M, Lefèvre T. TAVI:Simplification Is the Ultimate Sophistication. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:96.

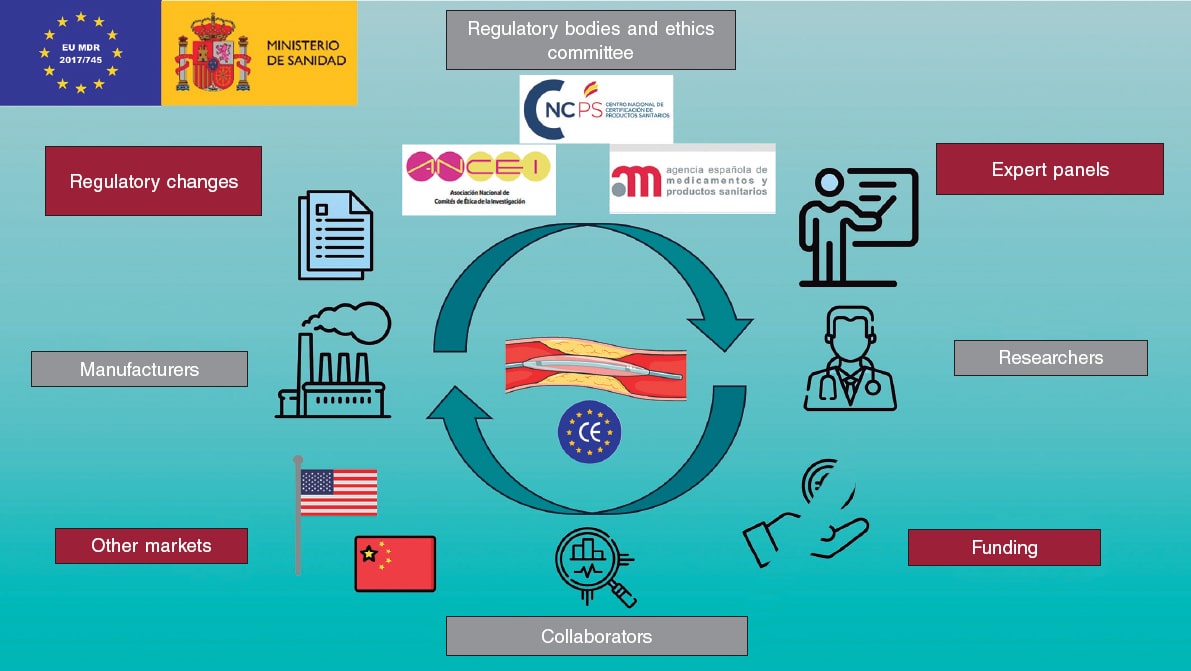

Regulation (EU) 2017/745 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2017 was published to regulate medical devices with the aim of bolstering the safety, quality, and efficacy of medical products in Europe.1

The regulation covers medical products intended for the diagnosis and treatment of numerous cardiovascular conditions, including high-risk devices such as pacemakers, defibrillators, artificial hearts, stents, cardiovascular sutures, heart valves, catheters, cardiovascular wires, and cardiac ablation instruments. According to the classification rules outlined in the regulation, all these high-risk medical products are classified as Class III.

The process for obtaining the CE mark for a medical device requires the manufacturer to demonstrate that the product meets the established safety and performance requirements and to conduct a clinical evaluation to validate the intended indication and purpose of use. For Class III product certification, a notified body designated by a member state authority must verify that the manufacturer has the objective technical and clinical documentation required to demonstrate that the product meets all the claims made by the manufacturer on the product. The authorized body issues a “CE Declaration of Conformity” including the manufacturer’s information, the product’s unique identifier, class, intended purpose, test reports and documentation, date and issue of validity, and details of the notified body involved in the process of granting the CE mark. The manufacturer’s company must also implement a quality management system to ensure that the manufactured products meet specified standards. After auditing the manufacturer’s facilities, the body issues an “EU quality management system certificate” detailing the scope of the quality system and type of manufactured products.

In other words, for the marketing of Class III medical products, the manufacturer must hold 2 different EU certificates issued by a notified body: one for the product and one for the quality management system.

Health care workers or users of a medical product can easily identify which notified body participated in its assessment by checking the product label, which is identified by a 4-digit number appearing alongside the CE mark. The name of the organization behind that number can be found on the European Commission’s website.2 For example, if the digits 0318 appear next to the CE mark on the label or the instructions for use of a medical product, it indicates that the evaluation was conducted by the National Certification Center for Medical Product, the sole notified body designated by the Ministry of Health.

The main change introduced in the regulation on product requirements involves the clinical evaluation. The assessment is especially strict for Class III products, which, as previously mentioned, are high risk. The first requirement is that the clinical evaluation validating the indication for use must be based on clinical data obtained from clinical investigations conducted with the product itself or a product that is technically, biologically, and clinically equivalent. The second requirement is that manufacturers must have access to the primary clinical data supporting the clinical evaluation of the medical product in question, either because they own them, or because the data have been published, or because they have a contractual agreement with the owner allowing permanent access and availability.

Although it may seem trivial, since the publication of the regulation, the availability of a compliant clinical evaluation has been the Achilles’ heel for manufacturers of medical products intending to market their products in Europe in the coming years.

During the 3 decades since the implementation of the directives, special emphasis has been placed on ensuring the safety and quality of medical products, while the available objective evidence supporting their clinical benefit has been relegated to a secondary role. Consequently, manufacturers of medical products that have been on the market for years have had to make considerable efforts and investments to obtain sufficient clinical data with the necessary level of evidence to support the clinical risk-benefit ratio esta- blished by the new legislation. Many have had to devise new clinical evaluation plans or review existing ones, including conducting specific postmarket clinical follow-up studies to provide clinical data with an adequate level of evidence. Therefore, we could say that a culture of the need for clinical research and publication of the obtained data is emerging in the medical products sector.

On the other hand, to minimize potential discrepancies between notified bodies in the assessment of the clinical evaluation of Class III implantable medical products (such as pacemakers), the regulation has established a centralized supervision procedure by a panel of experts in medical products from the European Medicines Agency (EMA). The role of this panel is to review and confirm the adequacy of both the clinical evaluation conducted by the manufacturer and the assessment made by the notified body, and provide any recommendations deemed appropriate regarding the decision on certifying the medical product. These recommendations may include proposing to certify or not certify the product, or to limit or restrict indications, among others.

An interesting point is that 18 out of the 43 applications received by the panel so far correspond to medical products within the “circulatory system” clinical area. In particular, the clinical evaluations of some stents, implantable defibrillators, and various types of heart valves have already undergone this procedure, and the resulting public opinions can be consulted in a list within the framework of the European Commission’s clinical evaluation consultation procedure.3

In addition, manufacturers of these types of products can seek guidance from the panel of experts before starting clinical development to confirm that the strategy designed for clinical development is appropriate and ensure that the resulting clinical evaluation will fully comply with the current legislation. If manufacturers decide to submit this voluntary query, the response issued by the panel will be binding. In other words, manufacturers will not be able to implement a different clinical evaluation plan from that recommended by the panel if they want to obtain the CE mark for the product.

The cornerstone of the CE certification model described is the competence of the personnel conducting the evaluation tasks. The personnel involved in the process of conducting or assessing the clinical evaluation of a medical product must have adequate knowledge. At the forefront of this chain are the manufacturers because they have had to review the competence of their staff to ensure that clinical evaluations are conducted by personnel experienced in clinical evaluation, competent in bibliographic searches, and with sufficient clinical knowledge and use of the products. Next are the notified bodies, which have to ensure that they have sufficient personnel with relevant clinical knowledge to issue a clinical judgment on the product’s risk-benefit ratio after analyzing and scientifically testing the clinical data collected in the clinical evaluation provided by the manufacturers. Furthermore, clinicians internal to the notified bodies must verify that the personnel conducting the clinical evaluations provided by the manufacturers are qualified to perform the task. Further along the review chain, notified bodies are audited by European teams of qualified professionals, who, in turn, must verify that the competencies of the personnel conducting the assessments of the clinical evaluations in the notified bodies meet the criteria of experience and training established in the regulation.

This regulation also encourages the manufacturers of medical products to hire health care workers with clinical experience, who have their own opinions on the products they use in their routine clinical practice. These professionals can participate in the early stages of product design, engage in usability testing, and, naturally, as occurs with drugs, promote clinical research both before and after product marketing. This helps to confirm the clinical benefit of medical products throughout their life cycle.

Health care workers must be aware of the value of their experience and clinical knowledge in ensuring that the medical products entering the market are truly innovative and meet the needs of patients.

The responsible and committed contribution made by each of the parties involved in conducting and reviewing the clinical evaluation of medical products will, on the one hand, provide greater assurance of the rigor, robustness, and sufficiency of the clinical data supporting a product’s indication. On the other hand, it will serve to standardize the criteria applied in the evaluation and ensure that the level of evidence required for all medical products bearing the CE mark under the new regulation is the same. These measures will restore confidence in the legislative model of medical products, ensuring that all manufacturers marketing their medical products in the European common market play by the same rules. Therefore, that the CE certification under which products are marketed will provide identical safeguards to patients, regardless of the country of origin, manufacturer, or issuing body.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Parlamento Europeo. Reglamento (UE) 2017/745 del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo, de 5 de abril de 2017, sobre los productos sanitarios, por el que se modifican la Directiva 2001/83/CE, el Reglamento (CE) n.º178/2002 y el Reglamento (CE) n.º1223/2009, y por el que se derogan las Directivas 90/385/CEE y 93/42/CEE del Consejo. DOUE. 2017;117:1-175.

2. European Commission. New Approach Notified and Designated Organisations -NANDO. Available at: https://webgate.ec.europa.eu/single-market-compliance-space/%23/notified-bodies/notified-body-list?filter=legislationId%3A34%2CnotificationStatusId%3A1. Accessed 18 Dec 2023.

3. European Commission. List of opinions provided under the CECP. Available at: https://health.ec.europa.eu/medical-devices-expert-panels/experts/list-opinions-provided-under-cecp_en#p2.

INTRODUCTION

When scientific projects or articles are evaluated, objections are often raised that may prevent their performance or publication. Sometimes, the flaws noted may not be correct or relevant to the study. In this article, we review the most common types of objections that can hinder the progress of medical research and suggest ways to reduce them.

CLINICAL (OR PROCEDURAL) OBJECTIONS AND STATISTICAL/METHODOLOGICAL OBJECTIONS

The objections an evaluator can make to a research project can be grouped into 2 broad categories: clinical (or procedural) and statistical/methodological.

The former can be addressed and, if necessary, refuted by the author of the project as they relate to the clinical problem per se. In this regard, the author of the project has more expertise and sometimes more up-to-date knowledge than the evaluator on the issue in question. A common example could be the objection, “the project does not specify under which conditions baseline blood pressure should be measured, or the criteria chosen to define hypertension.” The researcher can acknowledge the flaw in his/her protocol and correct it or argue that the objection is incorrect.

The situation is different with statistical/methodological objections. Researchers, whether acting as evaluators or persons who are evaluated, are not usually experts in research methodology and biostatistics. Below are a few examples of this type of objection.

Common erroneous statistical/methodological objections

Sample size

Contrary to what most researchers believe, the objection of an insufficient sample size is only relevant in highly specific situations. In some cases, it is not accurate; for example, if the result has a very small P value that constitutes strong evidence against the null hypothesis. It does not make any sense either in somewhat more complex situations.1

Statistical power

Statistical power depends on 4 parameters, whose value is often not predefined, so by choosing suitable values for these parameters, researchers can obtain almost any value for statistical power. In fact, when researchers are asked about the figure for statistical power, it is often insufficient to give a specific value, because the values of other parameters associated with such power are also necessary. Moreover, it is obvious that by slightly modifying these values within reasonable ranges, very different power values can be obtained.2

Test on the normal distribution of the response variable

In many cases, this objection may be doubly mistaken: either because the response variable is dichotomous and will be treated as such in the analysis, or because the sample size used is greater than, say, 30, and the central limit theorem guarantees a very good approximation to the normal distribution of the statistic used in the test. Naturally, it can never be guaranteed whether the variable has a normal distribution or not. Thus, in cases with a confirmed lack of normal distribution, the robustness of some parametric tests vs nonnormality must be taken into account.3 In cases with a strong association and an extremely small P value in the test, it should be noted that if the true P value of the test were, say, 10 times larger or 10 times smaller than that found in the parametric test, the practical conclusion would be the same.

Control group and study validity

While a control group is a great asset in many situations, demanding its presence should not be a universally or undisputed mantra. In some situations—and when used appropriately—historical controls provide enough information to draw very interesting conclusions. In other cases, each patient serves as his/her own control, thus allowing the use of intraindividual variability, which is often less than interindividual variability and, therefore, provides more powerful tests in many cases.

Pilot trials

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) add highly useful methodological refinements to effectively determine the safety and efficacy profile of a new drug or procedure. However, pilot trials can add these same methodological refinements and be controlled, randomized, and blinded to a point that the level of scientific evidence they provide can be equivalent to that of RCTs, with significant advantages regarding time and cost savings. In addition, in general, their size is not a determining factor that compromises their validity. Then, what is the main difference between the 2 designs? The difference lies not in the level of evidence they provide, but in the administrative process involved. RCTs require approval from external hospital, regional, or national committees, while pilot trials are endorsed by the expertise of the medical team involved in their design. For external evaluators, it is more challenging to make accurate assessments of each aspect of the project and provide a sound judgment. Moreover, if they have the authority to veto the study, there is a possibility of rejecting it based on insufficiently founded considerations.

Observational trials

Blinded RCTs are widely accepted as the best source of evidence on drug and treatment efficacy. However, observational studies can also provide information on long-term safety and efficacy, which is often lacking in RCTs. Additionally, they are less expensive, allow the study of rare events, and provide information more quickly than RCTs. New and ongoing developments in analytical and data technology offer a promising future for observational studies, which already play a key role in researching treatment outcomes. Data from large observational studies can clarify the tolerability profile of drugs and are particularly suitable for large and heterogeneous populations of patients with complex chronic diseases. RCTs and observational trials should, therefore, be considered to complement each other.

Case-control trials

Rothman4 states that case-control trials have gone from “being the Cinderella of medical research to one of its brightest stars.” In case-control designs, it is much more challenging to avoid the distortion caused by confounding factors. However, these issues are partially mitigated by segmentation, matching, and multivariate analysis techniques. In some cases, they can provide significant statistical evidence much faster and more cheaply than clinical trials. Let’s consider an example of a disease that affects 1% of the population who do not follow a particular diet, and 5% of those who do follow it, knowing that 40% of the population follows that diet. A prospective trial would take 80 people from the diet group and another 80 from the control group, and after the agreed-upon time, we would measure the incidence of the disease in each of the 2 groups. The statistical power of this study for an alpha value of 0.05 would be 8%. A case-control trial would take 80 patients with the disease and 80 without it, and with very detailed health records, we would be able to determine the percentage of people who follow that diet in each of the 2 groups. The statistical power would be 93%.

The list of erroneous objections is much longer, however, and each would require a dedicated article to explain it.

CONCLUSIONS

Some of the methodological objections raised by the evaluators are incorrect. In most cases, the evaluated party assumes that his/her project has a major flaw and ends up abandoning it. Consequently, many projects that could have provided valuable information are unfairly discarded slowing down the progress of medicine.

We believe that this anomaly would largely be avoided if: a) evaluators raised methodological objections only in areas in which they have in-depth knowledge; b) whenever possible, the judgment issued by the evaluators from health agencies and bioethics committees was a suggestion instead of a veto; c) the fundamental role of observational trials, which can be highly effective and generally cheaper than clinical trials, was recognized; d) pilot trials were conducted in many cases where they are indicated, because they can be controlled, randomized, and blinded but without the restrictions associated with RCTs (figure 1).

Figure 1. Measures to expedite medical research by promoting the autonomy of qualified physicians, avoiding unjustified methodological objections, and promoting the use of currently underrated designs.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Egbuchulem KI. The basics of sample size estimation:an editor's view. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2023;21:5-10.

2. Prieto-Valiente L, Carazo-Díaz C. Potencia estadística en investigación médica. ¿Quépostura tomar cuando los resultados de la investigación son significativos?Rev Neurol. 2023;77:171-173.

3. Roco-Videla A, Landabur Ayala R, Maureira Carsalade N, Olguín-Barraza M. ¿Cómo determinar efectivamente si una serie de datos sigue una distribución normal cuando el tamaño muestral es pequeño?Nutr Hosp. 2023;40:234-235.

4. Rothman KJ. The origin of Modern Epidemiology, the book. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36:763-765.

Aortic valve stenosis is one of the most acute and chronic cardiovascular disease conditions. Bicuspid aortic valve is the most common congenital heart abnormality and affected individuals have a 50% chance of developing severe aortic valve stenosis during their lifetime. In aortic valve disease (both aortic valve stenosis and bicuspid aortic valve), the heart valves are damaged and do not work properly. This condition can rapidly affect the pumping action of the heart and can progress to heart failure. Heart failure is a deadly disease affecting at least 26 million people worldwide and its prevalence is increasing with high mortality and morbidity.1 Most importantly, aortic valve disease commonly coexists with other cardiovascular diseases, giving rise to the most general yet fundamentally challenging scenario: complex valvular, ventricular, and vascular diseases (C3VD). In C3VD, multiple valvular, ventricular, and vascular pathologies interact with one another, while the physical phenomena associated with each pathology amplify the effects of others on the cardiovascular system.

Left ventricle (LV) pressure-volume (P-V) loop analysis is a powerful tool to assess cardiac mechanics. This analysis can reveal the pathophysiological mechanisms of heart failure, including heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and myocardial and valvular diseases. It is, therefore, instrumental in the evaluation and management of heart failure and valvular heart disease and can also help explain the short- and long-term effects of valvular and other interventions with cardiac implications. In addition, ventricular P-V loop analysis can be used to monitor the cardiac effects of related medical devices, mechanical heart support, therapeutic interventions, and medications.2-5 Indeed, ventricular P-V loop analysis has exceptional potential for integration into current clinical practice to advance the standard of care.

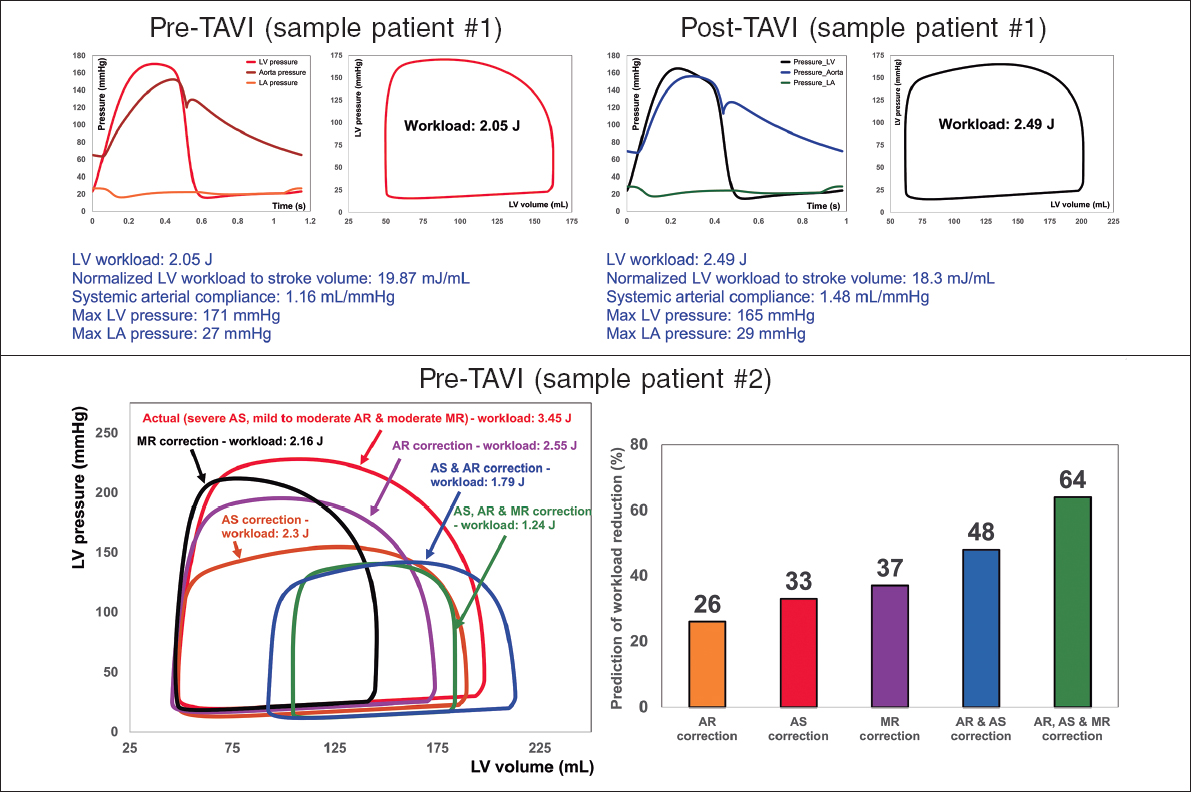

Aortic valvular disease increases LV pressure, LV end-diastolic pressure, LV workload, the stiffness of the systemic arterial system, and LV afterload, contributing to LV systolic and diastolic dysfunction,6 an important cause of heart failure in such patients. While transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) provides positive outcomes and has markedly reduced the mortality rate, TAVI fails in nearly 25% to 35% of patients (patients either die or do not recover a reasonable quality of life after the procedure).7 Indeed, the immediate intraprocedural as well the longitudinal hemodynamic changes affecting the aortic-left ventricular system after aortic valve replacement are poorly understood. While TAVI universally reduces the transvalvular pressure gradient, it is anticipated to improve systolic and diastolic LV function in the long-term. Despite the benefits, invasive LV P-V loop analysis revealed impaired LV systolic and diastolic function in the early phase following TAVI.6,8 LV P-V loop analysis also revealed exacerbated heart failure despite successful TAVI procedures in many patients.5,9 Indeed, LV P-V loop analysis elucidated that reductions in transvalvular pressure gradient post-TAVI were not always accompanied by improvements in LV workload. TAVI has been shown to have no effect on LV workload in many patients, while LV workload post-TAVI significantly rose in many others.2,5,10

In clinical settings, cardiac catheterization is the gold standard for evaluating pressure and flow through the heart to perform ventricular P-V loop analysis. However, due to its invasiveness, cost, and high risk, it is impractical for diagnosis in routine daily clinical applications or serial follow-up examinations. Most importantly, cardiac catheterization only provides access to the blood pressure in very limited regions rather than details of physiological flow and pressures throughout the heart and circulatory system. In addition, there is no method to invasively or non-invasively quantify the heart workload that can provide a contribution breakdown of each component of the cardiovascular diseases. This is especially crucial in the presence of TAVI and C3VD, in which quantification of left ventricular workload and its breakdown are important to guide the priority of interventions. Moreover, there is no noninvasive method for determining LV end-diastolic pressure, instantaneous LV pressure, and contractility. All these parameters provide valuable information about the patient’s cardiac deterioration and heart recovery.

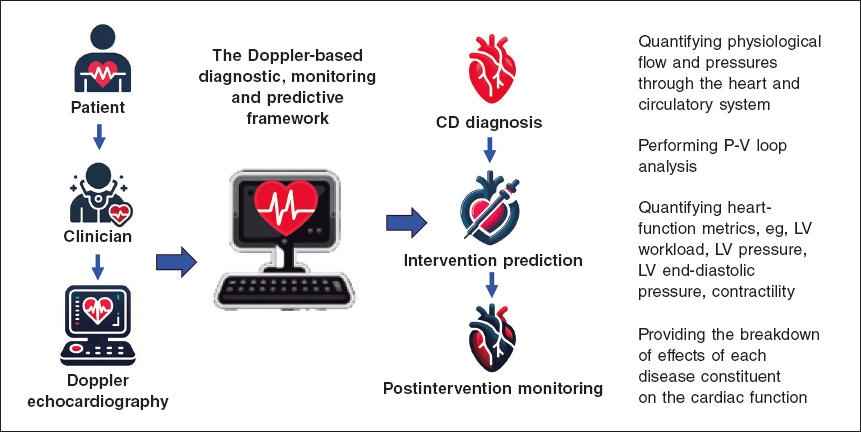

Keshavarz-Motamed11,12 developed the first and the only Doppler-based noninvasive patient-specific diagnostic, monitoring, and predictive tool that can investigate and quantify the effects of interventions, medications, and C3VD constituents on the function of the heart and circulatory system at no risk to the patient (figure 1).

Figure 1. Doppler-based patient-specific diagnostic, monitoring, and predictive tool flowchart. The tool uses a few input parameters that can all be measured using Doppler echocardiography simply and reliably. This novel tool4,10–15 was validated against cardiac catheterization and 4D flow MRI in patients with C3VD (so far ~ n = 600) with substantial inter- and intra-patient variability with a wide range of (adult and congenital) cardiovascular diseases. 4D, 4-dimensional; C3VD, complex valvular, ventricular, and vascular diseases; CD, cardiovascular disease; LV, left ventricular; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

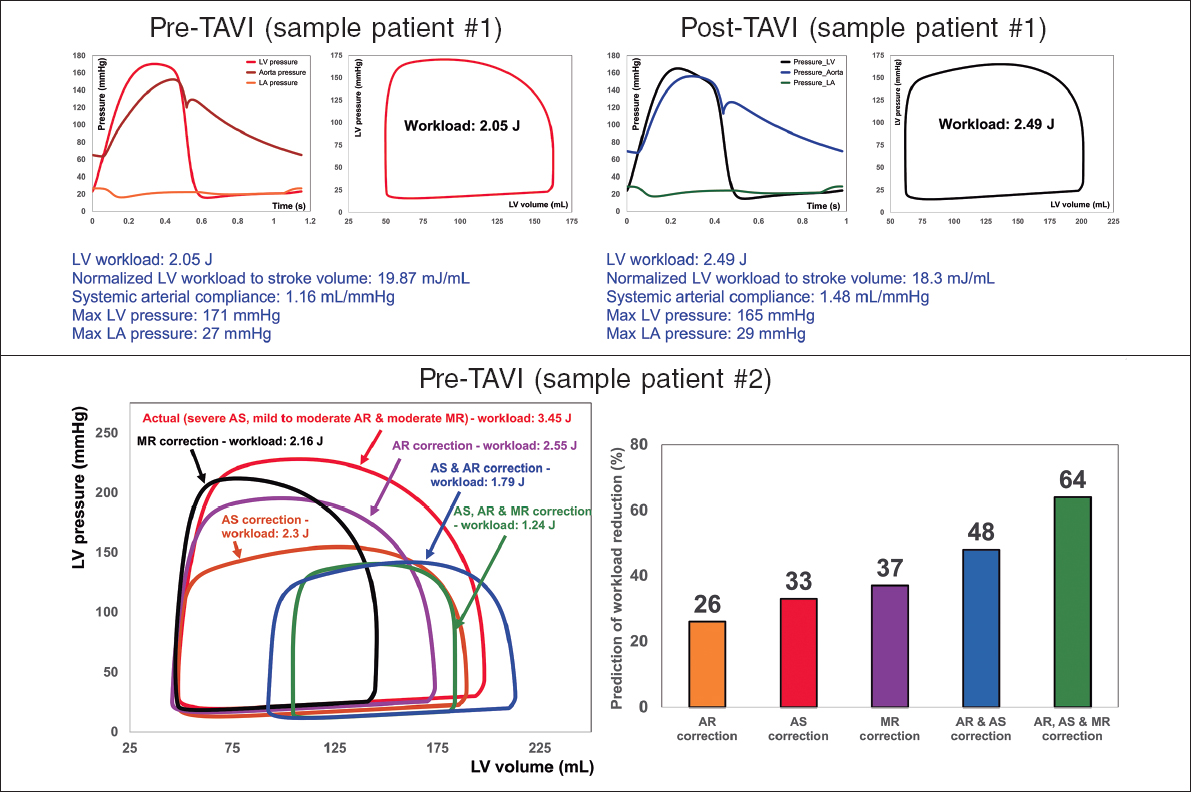

This novel method4,10-15 offers several key capabilities (figure 2, sample results): a) quantifying details of physiological pulsatile flow and pressures through the heart and circulatory system; b) tracking cardiac and vascular states based on accurate time-varying models that reproduce physiological responses; c) performing LV P-V loop analysis and quantifying heart function metrics, specifically in terms of the heart workload; d) providing a breakdown of the effects of disease constituents on global heart function (eg, heart workload) to help predict the effects of interventions and plan the sequence of interventions in C3VD; e) quantifying other heart-function metrics, including LV end-diastolic pressure, instantaneous LV pressure, and contractility. None of the above metrics can be obtained non-invasively in patients, and when invasive cardiac catheterization is undertaken, the collected metrics cannot be as complete as what the novel method can provide. While such information is vitally needed for the effective use of advanced therapies to improve clinical outcomes and to guide interventions in patients, they are not currently accessible in clinical settings.

Figure 2. Diagnosis and monitoring in sample patient 1 from baseline to 90 days: this patient did not fully benefit form transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Instead of improving the patient’s heart condition by reducing LV workload, TAVI caused an increase in LV workload. Example of workload breakdown analysis and prediction for effects of interventions in sample patient 2: right: P-V loops of the actual disease condition and prediction of several valve interventions. Left: predicted percent decrease in LV workload following valve interventions. Both mitral valve regurgitation (38% increase) and aortic valve stenosis and regurgitation (48% increase) substantially contributed to increasing the workload. This patient only underwent TAVI. However, considering this calculation, the decision to also perform mitral intervention at the time of aortic valve intervention should have been evaluated. AS, aortic stenosis; AR, aortic regurgitation; MR, mitral regurgitation; LV, left ventricle; LA, left atrium. We retrospectively received patients’ data from multicentre in which waiver of informed consent and data transfer were approved by their Institutional Review Boards.

CONCLUSION

The novel method, developed and verified by Keshavarz-Motamed,11,12 purposefully uses reliable and noninvasive input parameters measured by Doppler echocardiography to continuously calculate patient-specific hemodynamics to be used for diagnosis, monitoring, and prediction of cardiac function and circulatory status. This innovative method holds potential applications: a) in clinical trials, enabling the noninvasive analysis of cardiac and circulatory function metrics; b) as a diagnostic tool to noninvasively analyze cardiac function metrics for routine care, ambulatory care, or intensive and critical care units; c) as a patient monitoring tool, potentially integrated into personal wearable devices; and d) as a module incorporated into the software of Doppler echocardiography machines for enhanced diagnosis and prediction.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

1. Savarese G, Lund LH. Global Public Health Burden of Heart Failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3:7-11.

2. Keshavarz-Motamed Z, Khodaei S, Rikhtegar Nezami F, et al. Mixed Valvular Disease Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:Quantification and Systematic Differentiation Using Clinical Measurements and Image-Based Patient-Specific In Silico Modeling. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015063.

3. Bastos MB, Burkhoff D, Maly J, et al. Invasive left ventricle pressure-volume analysis:overview and practical clinical implications. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1286-1297.

4. Khodaei S, Abdelkhalek M, Maftoon N, Emadi A, Keshavarz-Motamed Z. Early Detection of Risk of Neo-Sinus Blood Stasis Post-Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Using Personalized Hemodynamic Analysis. Struct Heart. 2023;7:100180.

5. Ben-Assa E, Brown J, Keshavarz-Motamed Z, et al. Ventricular stroke work and vascular impedance refine the characterization of patients with aortic stenosis. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11:eaaw0181.

6. Seppelt PC, De Rosa R, Mas-Peiro S, Zeiher AM, Vasa-Nicotera M. Early hemodynamic changes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis measured by invasive pressure volume loop analysis. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2022;37:191-201.

7. Arnold SV. Calculating Risk for Poor Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Clin Outcomes Manag. 2019;26:125-129.

8. Sarraf M, Burkhoff D, Brener MI. First-in-Man 4-Chamber Pressure-Volume Analysis During Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3:77-81.

9. Fischer-Rasokat U, Renker M, Liebetrau C, et al. Outcome of patients with heart failure after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225473.

10. Khodaei S, Garber L, Abdelkhalek M, Maftoon N, Emadi A, Keshavarz-Motamed Z. Reducing Long-Term Mortality Post Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Requires Systemic Differentiation of Patient-Specific Coronary Hemodynamics. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2023;12:e029310.

11. Keshavarz-Motamed Z. A diagnostic, monitoring, and predictive tool for patients with complex valvular, vascular and ventricular diseases. Sci Rep. 2020;10:1-19.

12. Keshavarz Motamed Z. Diagnostic, monitoring, and predictive tool for subjects with complex valvular, vascular and ventricular diseases. US &Canada patent US11844645B2, granted, 2023.

13. Bahadormanesh N, Tomka B, Kadem M, Khodaei S, Keshavarz-Motamed Z. An ultrasound-exclusive non-invasive computational diagnostic framework for personalized cardiology of aortic valve stenosis. Med Image Anal. 2023;87:102795.

14. Sadeghi R, Tomka B, Khodaei S, Garcia J, Ganame J, Keshavarz-Motamed Z. Reducing Morbidity and Mortality in Patients With Coarctation Requires Systematic Differentiation of Impacts of Mixed Valvular Disease on Coarctation Hemodynamics. J Am Heart Assoc.2022;11:e022664.

15. Sadeghi R, Tomka B, Khodaei S, et al. Impact of extra-anatomical bypass on coarctation fluid dynamics using patient-specific lumped parameter and Lattice Boltzmann modeling. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9718.

- Drug-coated balloons on the “big stage”: is this technology ready for an all-comer population with de novo lesions?

- Implementing an ANOCA clinic

- Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation in native outflow tracts: has the time come?

- Transcatheter aortic valve replacement for noncalcified aortic regurgitation. Where are we now?

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

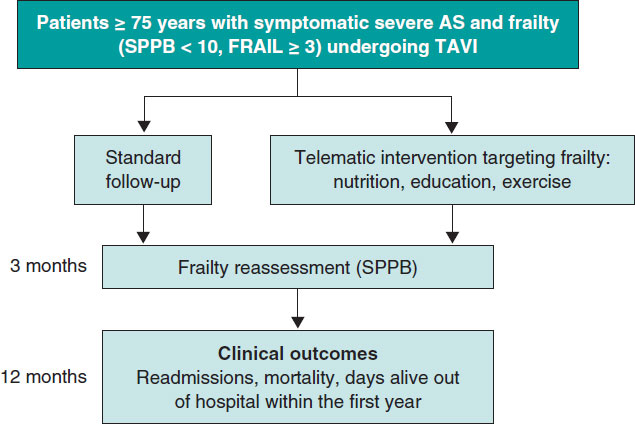

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España