Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

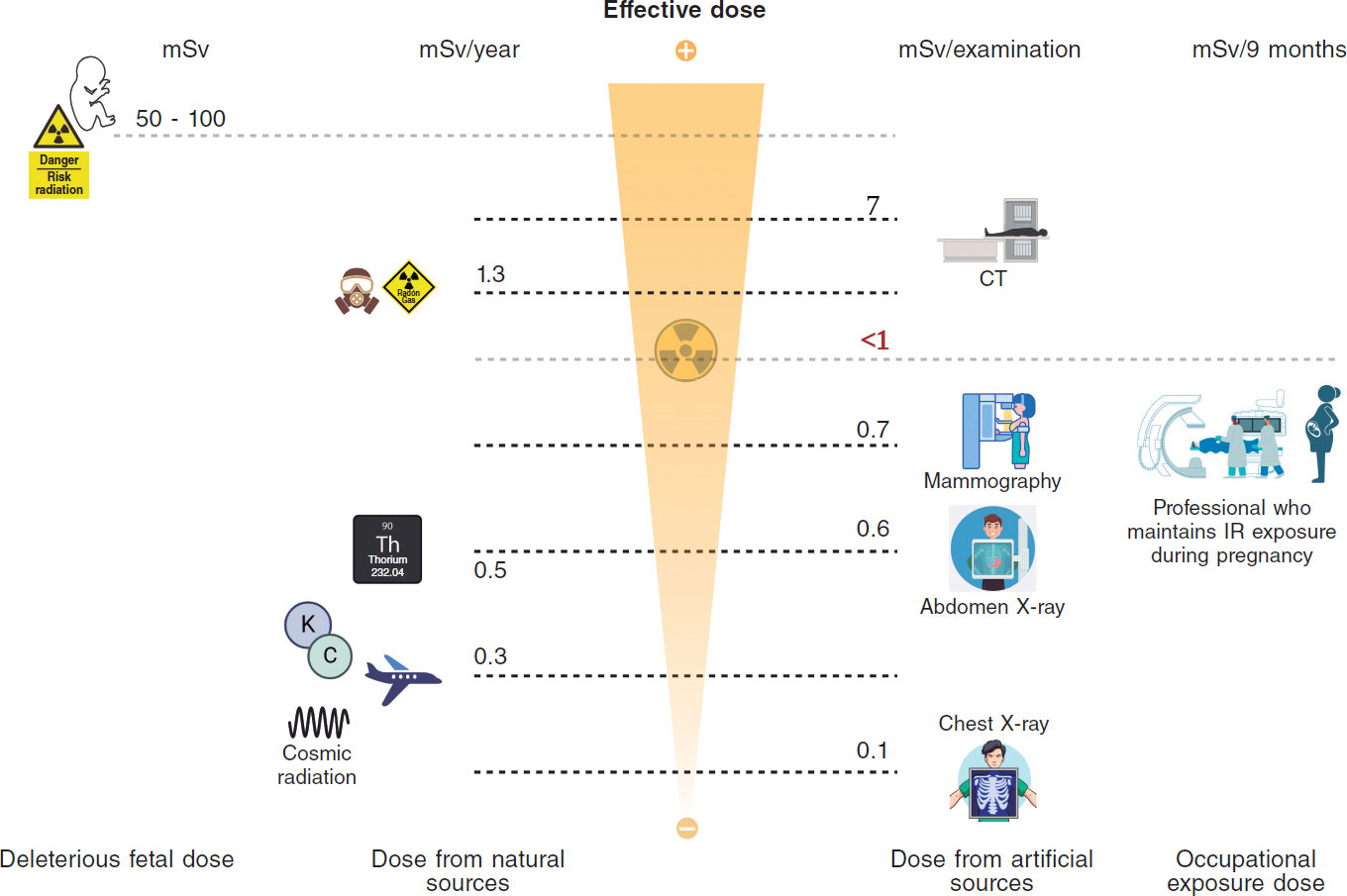

Are the radiation doses we use in interventional procedures appropriate? Cardiologists should be able to answer this question, which is particularly important in pediatric patients. However, the answer matters not only to patients but also to the health professionals involved in these procedures. The occupational radiation doses received by health staff are associated with the doses received by patients, and “optimization” (keeping radiation doses to the minimum needed to achieve the clinical objective of the procedures involved) should be managed comprehensively for patients and professionals alike.1

The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) recommends using “diagnostic reference levels” (DRLs) to help in the optimization of imaging modalities with ionizing radiation (including interventional procedures).2

DRLs are indicative of “good clinical practice”. It is recommended that they be established for specific clinical indications and can be estimated for the local, national, or regional level by using the third quartile of the distribution of the median values of the dose indicators for patients from various centers representative of these clinical practices.2

The term “achievable dose value” has been proposed in the United States for the 50th percentile instead of the third quartile. Although the ICRP has stated that the median could be used as an additional step in optimization, the recommendation of using the third quartile recommendation to estimate DRLs still stands.2

For interventional procedures, the most widely used radiological measure is the kerma-area product (KAP), which is numerically equivalent to the dose-area product (DAP), and serves as one of the main indicators of the radiation doses received by patients. Secondary indicators that can also be used are the kerma at the patient entrance reference point (15 cm below the isocenter), fluoroscopy time, and the number of cine images acquired. These latter 2 indicators are becoming less relevant because doses depend on different image acquisition modes.

The ICRP recommends taking into consideration the complexity of interventional procedures, since it can increase DRLs significantly. Because complexity can vary widely for a single procedure, carried out for the same or similar clinical indications, it is important to assess its impact on the doses delivered to patients.3,4

The ICRP recommendations have been included in the European regulations (Directive 59/2013 EURATOM)5 and the corresponding practical guidelines of the European Union.6,7 For pediatric procedures, it is suggested that DRLs be estimated based on patient age and weight categories.2

The radiation doses received by pediatric patients vary widely depending on their size and weight. Although variations are inevitable, we should try to avoid those stemming from inappropriate use of imaging modalities (different fluoroscopy or cine modes) or protocols. DRLs help optimize radiation protection.

Different fluoroscopy and cine modes with varying dose rates (and image quality) can be used, substantially impacting the radiation doses received by patients. Factors that play a key role in delivered radiation doses are collimation, C-arm x-ray machine angles, fluoroscopy sequence recording to save cine sequences, and rotational acquisitions.

Ways to significantly reduce the radiation doses received by patients and health professionals are knowing the quality control results of x-ray machines (to understand dose differences between cine and fluoroscopy acquisitions) and fostering collaboration between hospital radiologists and cardiologists, along with continuous medical education programs on radiation safety.

All these variables associated with different operating modes can substantially change the doses delivered to patients and the quality of diagnostic information. Therefore, cardiologists’ knowledge and experience of their imaging equipment are crucial. In general, state-of-the-art machines reduce radiation doses while maintaining similar or improved diagnostic information. Quantifying all these factors and deciding whether corrective actions are needed involves comparing radiation doses for specific procedures with the DRLs.

The Royal Decree that transposes part of the European Directive to the Spanish legislation8 demonstrates the implementation and regular review of DRLs. If these DRLs are consistently and significantly exceeded, or if image quality deteriorates repeatedly, the corresponding local reviews should be undertaken and appropriate corrective measures should be implemented without delay.

Some automated dose management systems allow real-time reception and processing of the radiation doses received by patients and operators. These systems can create alerts for safer interventional practices.9,10

Several studies have been published on DRLs in interventional cardiology for adult patients (DOCCACI program) in Spain11,12 with collaboration from the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

No nationwide results have been published on the doses received by pediatric patients in interventional cardiology until now. However, Rueda Núñez et al.13 recently presented the results of the Radcong-21 Registry conducted by the Cardiac Catheterization Working Group of the Spanish Society of Pediatric Cardiology and Congenital Heart Disease (GTH-SECPCC) on the overall values from a sample of 1090 procedures across 10 different hospitals. This registry represents a significant initiative that could encourage other centers to compare their values with dose indicators obtained from a representative sample of multiple Spanish hospitals in patients with congenital heart disease treated with cardiac catheterization and categorized by type of procedure and estimated radiation risk (ERR).

The study authors used medians, although DRL values refer to the third quartile of the distribution of the median values in the different centers involved. Specific DAP/kg values are provided for certain specific procedures to treat prevalent conditions such as aortic coarctations, atrial septal defects, ductus arteriosus occlusions, aortic and pulmonary valvuloplasties and pulmonary valve implantations following the methodology proposed by Quinn et al.14 in the United States.

DAP/kg/fluoroscopy is a parameter that can be confusing when comparing radiation doses. This is because the total DAP includes contributions from fluoroscopic imaging—corresponding to different fluoroscopy modes with very different dose values—and cine acquisitions.

To facilitate comparisons and potential optimization efforts, the authors could provide dose indicator values (DAP/kg) tailored to a wider range of procedure types in future updates of the results. They could also use the third quartiles of the distribution of the median values for each center for the weight categories recommended by the ICRP and European guidelines.2,6,7

We could speculate whether it would be better to perform a global analysis across groups of different procedures or an analysis specifically designed for procedures with specific clinical indications. Quinn et al.14 choose the former, while managing the DAP/kg values as the primary dose parameter. However, a global approach does not allow analysis of specific procedures requiring corrective measures when the doses delivered to some patients may be very high. These doses exceeding the “good clinical practice” threshold can be used in certain procedures, but not in others, within the 3 REC (Radiation Exposure Category) groups proposed by Quinn et al.14 in their methodology. The advantage of using DRLs per weight group is that these DLRs are estimated for specific clinical indications, thus enabling easy comparisons with the dose indicators used in different hospitals for these procedures.

The global KAP/kg values for groups of different procedures may be balanced if there are procedures using higher radiation doses than necessary (due to excessive cine acquisitions, high-dose fluoroscopy modes, lack of collimation, etc) and other procedures requiring standard doses. This could indicate overall improvement (fewer doses in procedural groups), but does not necessarily indicate improvement in all types of procedures.

The effort made by the GTH-SECPCC to obtain and process PDA/kg values represents a significant advancement that could be further expanded in the future. This could involve establishing initial DRLs (KAP values) in Spain, based on weight and age groups, following the recommendations of the European guidelines and ICRP.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. ICRP. Occupational radiological protection in interventional procedures. ICRP Publication 139. Ann. ICRP 2018 47. Available at: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%20139. Accessed 17 Jun 2023.

2. ICRP. Diagnostic reference levels in medical imaging. ICRP Publication 135. Ann. ICRP 2017. Available at: https://www.icrp.org/publication.asp?id=ICRP%20Publication%20135. Accessed 17 Jun 2023.

3. Bernardi G, Padovani R, Morocutti G, et al. Clinical and technical determinants of the complexity of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty procedures:analysis in relation to radiation exposure parameters. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51:1-9;discussion 10.

4. Balter S, Miller DL, Vano E, et al. A pilot study exploring the possibility of establishing guidance levels in x-ray directed interventional procedures. Med Phys. 2008;35:673-680.

5. EUR-LEX. Council directive 2013/59/Euratom of 5 December 2013 laying down basic safety standards for protection against the dangers arising from exposure to ionising radiation and repealing Directives 89/618/Euratom, 90/641/Euratom, 96/29/Euratom, 97/43/Euratom and 2003/122/Euratom. Official Journal of the European Union. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2013/59/oj. Accessed 3 Jul 2023.

6. Radiation Protection No 185 - European Guidelines on Diagnostic Reference Levels for Paediatric Imaging. Directorate-General for Energy Directorate D. Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety. 2018. Available at: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2018-09/rp_185_0.pdf. Accessed 17 Jun 2023.

7. Radiation Protection 195. European study on clinical diagnostic reference levels for X-ray medical imaging EUCLID. Luxembourg:Publications Office of the European Union, 2021. Available at: European study on clinical diagnostic reference levels for X-ray medical imaging - Publications Office of the EU (europa.eu). Accessed 3 Jul 2023.

8. Real Decreto 601/2019, de 18 de octubre, sobre justificación y optimización del uso de las radiaciones ionizantes para la protección radiológica de las personas con ocasión de exposiciones médicas. Boletín Oficial del Estado núm. 262, de 31 de octubre de 2019. Available at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2019/10/18/601. Accessed 19 Jun 2023.

9. Vano E, Sanchez RM, Fernandez JM. Strategies to optimise occupational radiation protection in interventional cardiology using simultaneous registration of patient and staff doses. J Radiol Prot. 2018;38:1077-1088.

10. Vano E, Fernandez-Soto JM, Ten JI, Sanchez Casanueva RM. Occupational and patient doses for interventional radiology integrated into a dose management system. Br J Radiol. 2023;96:20220607.

11. Sánchez RM, Vano E, Fernández JM, Escaned J, Goicolea J, PifarréX;DOCCACI Group. Initial results from a national follow-up program to monitor radiation doses for patients in interventional cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014;67:63-65.

12. Sánchez R, VañóE, Fernández Soto JM, et al. Updating national diagnostic reference levels for interventional cardiology and methodological aspects. Phys Med. 2020;70:169-175.

13. Rueda Núñez F, Abelleira Pardeiro C, Insa Albert B, et al. Dosimetric parameters in congenital cardiac catheterizations in Spain:the GTH-SECPCC Radcong-21 multicenter registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M23000372.

14. Quinn BP, Cevallos P, Armstrong A, et al. Longitudinal Improvements in Radiation Exposure in Cardiac Catheterization for Congenital Heart Disease:A Prospective Multicenter C3PO-QI Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e008172.

Cardialysis was founded in 1983 by visionary professionals from the Thoraxcenter at Erasmus University Medical Center (EMC) in Rotterdam, The Netherlands. This initiative emerged to address the need for a specialized research organization able to plan, execute, and report European cooperative clinical investigations in the field of cardiovascular research.1 The mission of Cardialysis is “to be at the heart of cardiovascular research” in the fullest sense of the phrase. To achieve this mission, the organization strives to collaborate with clinicians, trialists, research professionals, regulators, industry partners, and research organizations that share the same passion. Throughout the first 40 years, its well-established reputation has been based on dedication, diligence, and industry-leading standards. This has been made possible by attracting and retaining talented employees, as well as by cultivating long-standing relationships with investigators, clients, and partners.

Organizations similar to Cardialysis are typically classified as either academic research organizations (AROs) or contract research organizations (CROs). AROs, such as clinical trial units and epidemiology departments, are typically affiliated with universities or university hospitals, and usually design and manage investigator-initiated single-center or multicenter national clinical trials. These organizations are academically-driven and their traditional objectives are to facilitate research and education, publish innovative research in peer-reviewed journals, and support PhD programs. In contrast, CROs are private entities performing sponsor-driven clinical trials across all phases of clinical development. These organizations are business-driven, and expected to remain self-sustaining by establishing research contracts with the medical industry in a strict regulatory environment.

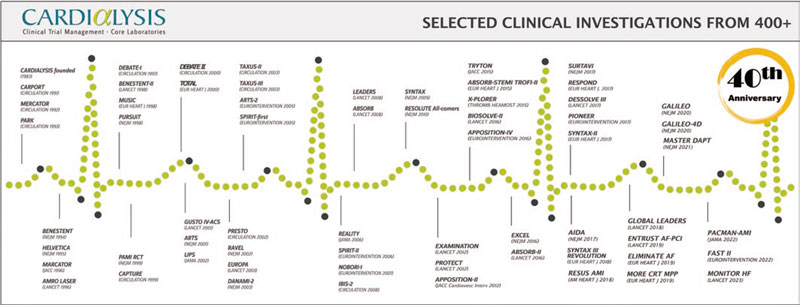

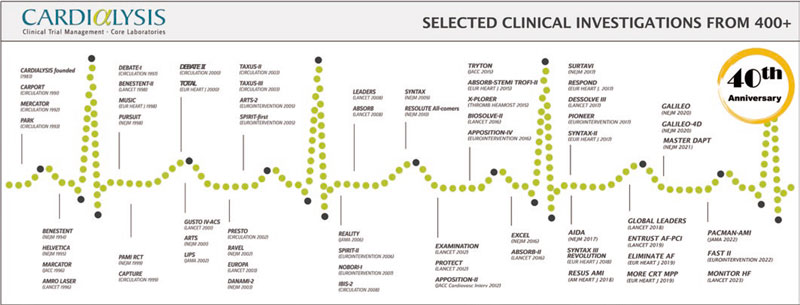

Similar to other world-leaders in cardiovascular research, Cardialysis has successfully adopted a hybrid ARO/CRO model, combining the best of the 2 models. First, the organization participates in innovative research that has played a pivotal role in the development and improvement of therapies in cardiology. This involvement has resulted in numerous high-impact publications and the completion of more than 100 theses through its support of in-house academic research. Figure 1 lists notable trials in which Cardialysis participated, including research in coronary artery disease, structural heart disease, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease. Second, the organization proudly maintains a global network of renowned investigators who play key roles in the academic leadership of trials (eg, within steering committees), independent clinical events committees (CECs),2 independent data and safety monitoring boards,3 and imaging core lab supervision. Third, Cardialysis operates as a private, independent entity that serves both university hospitals worldwide, as well as leading pharmaceutical and medical device industry partners. Fourth, the organization maintains state-of-the-art infrastructure and follows standardized procedures, ensuring efficiency and quality. Finally, Cardialysis consistently adheres to applicable regulatory requirements for trial execution in all active regions, including Europe, the United States of America, and China.

Figure 1. Timeline of landmark trials conducted with Cardialysis.

THE CARDIALYSIS CORE LAB

Over the past half century, clinical research has had an enormous impact on clinical outcomes, which was eloquently summarized by Nabel and Braunwald.4 These advancements are inextricably linked to the development of therapeutic and diagnostic devices, especially in interventional cardiology. The development of coronary angioplasty involved progressive iterations in coronary stent technologies and continuous innovation in intracoronary imaging.5 Similarly, advancements in transcatheter therapies for aortic, mitral, and tricuspid conditions have paralleled the progress in imaging modalities and techniques.6 Independent and consistent assessments of imaging outcomes are an important component of dossier evaluations when commercialization approvals are sought for new devices.7

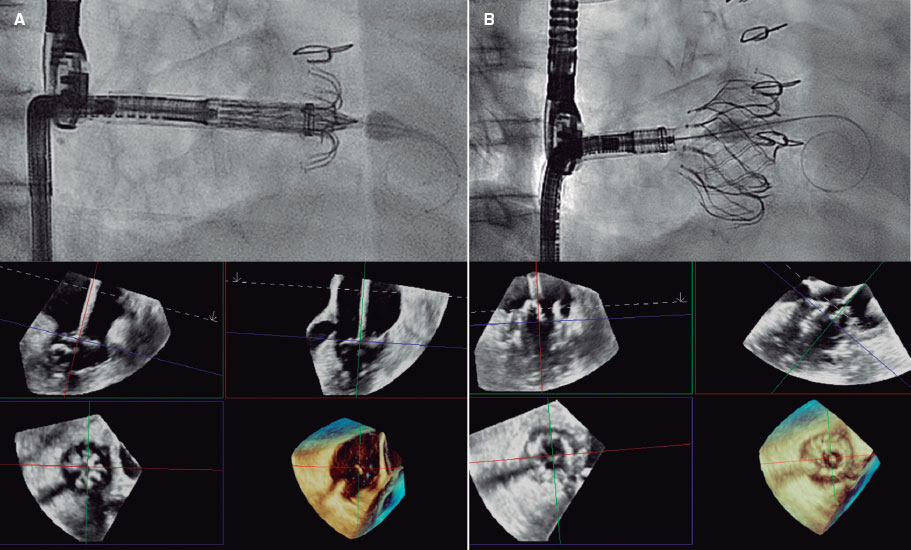

Cardialysis started as a central reading facility for electrocardiography-Holter monitoring. However, over time it has validated and implemented rigorous analysis methodologies for various imaging techniques within the coronary core lab. These include quantitative coronary angiography (n = 67 000+), intravascular ultrasound (n = 16 000+), near-infrared spectroscopy (n = 1500+), and optical coherence tomography (n = 5000+). Notably, Cardialysis also launched and maintains the globally used SYNTAX score (n = 10 000+) website.8 Due to a shift toward structural heart research, its echocardiography core lab has become its largest laboratory and serves large European and global investigations (n = 39 000+). Additionally, the organization operates magnetic resonance imaging (n = 1000+), cardiac computed tomography (n = 1000+), and electrocardiography-Holter core laboratories (n = 270 000+).

CARDIALYSIS CLINICAL TRIAL ACTIVITIES

The workload involved in a clinical investigation should not be underestimated. For example, the ongoing IVUS CHIP randomized clinical trial (NCT04854070) involves 40 sites in Europe and more than 200 professionals in the execution of the study, excluding the members of the Ethics Committees. Managing and coordinating more than 200 professionals across 7 countries for a minimum of 5 years requires high levels of availability, dedication, consistency, and well-established standardized procedures. Having an all-inclusive research organization performing ambitious trials increases efficiencies. Table 1 lists the activities performed at Cardialysis, which are those expected of any all-round professional research organization. Further information is available on the Cardialysis website.8

Table 1. List of activities performed at a cardiovascular research organization

| Trial design and protocol development |

| Steering committee set-up and coordination |

| Site feasibility and selection |

| Site start-up and regulatory submissions |

| Site contracting |

| Project management |

| Monitoring management |

| Site management and site monitoring |

| Safety reporting |

| Medical monitoring |

| Electronic case report forms development and hosting |

| Data management |

| Clinical events committee set-up and coordination |

| Data and safety monitoring board set-up and coordination |

| Publication committee set-up and coordination |

| Biostatistics: sample sizing, statistical analysis plan, and statistical reporting |

| Medical writing including patient narratives |

| Publication strategy |

| Quality assurance and regulatory compliance |

THE ACADEMIC RESEARCH CONSORTIUM

In 2006, with the increasing need for consistent endpoint definitions in coronary artery disease research, and specifically due to the challenges posed by the classification of stent thrombosis, leading AROs in the United States and Europe, including Cardialysis, collaborated to found the Academic Research Consortium (ARC).8 The primary mission of the ARC is to promote informed and collaborative dialogue among stakeholders, with the goal of developing consensus definitions and nomenclature for targeted areas of new medical device development, and to disseminate such definitions in the public domain.8 The first initiative focused on endpoint definitions and classifications for coronary intervention trials and was published in 2007.9 This consensus document was developed in consultation with regulatory agencies in both the United States and Europe, and became one of the most cited articles in interventional cardiology. To date, the ARC has successfully launched and completed 20 programs and is currently running 15 new initiatives based on an unprecedented level of global scientific collaboration.8

EUROPEAN CARDIOVASCULAR RESEARCH INSTITUTE

Europe is known for its stringent regulations on academic research. Importantly, the sponsor of a clinical investigation is the legal entity (or individual) that ensures that regulations are met and that monitors patient safety either directly or through a data and safety monitoring board. The sponsor holds full rights to the study data (ie, has sole ownership) and is responsible for verifying data integrity, ensuring that published results are consistent with the locked final analysis database. Although prominent academic centers possess the expertise to sponsor clinical trials, the size of certain studies requires external support for manageability.

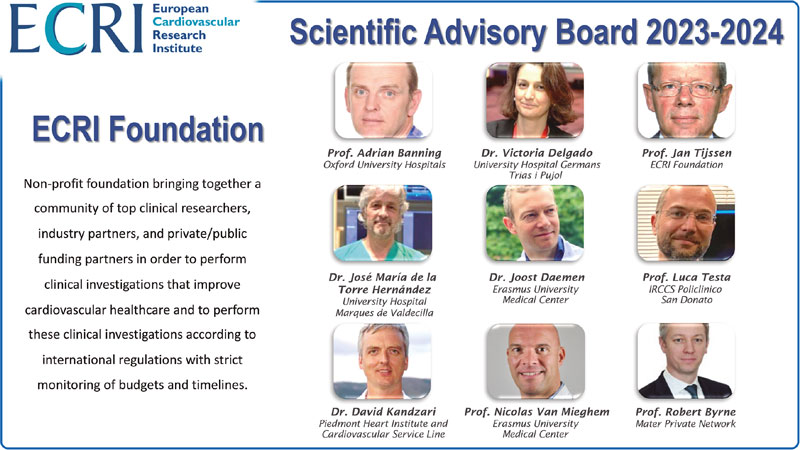

In response to this need, the European Cardiovascular Research Institute (ECRI) was founded in 2012 by the Cardialysis group as an academic research platform capable of overseeing the execution of large, multicenter clinical trials and of fulfilling sponsor responsibilities. Since April 2023, the ECRI has become an independent foundation (Stichting) under Dutch law. This institute combines 3 elements of success: its outstanding academic leadership represented by its pro bono scientific advisory board (figure 2), a well-established network of investigators and research professionals, and the possibility to conduct clinical research activities in partnership with Cardialysis. Through this collaborative model, the ECRI-Cardialysis joint venture has successfully conducted some of the largest interventional cardiology trials, with the GLOBAL LEADERS trial being the most representative.10 This trial enrolled 15 968 patients at 130 sites across 18 countries. Another example is the MASTER DAPT trial,11 which enrolled 4579 high-bleeding risk patients at 140 sites in 30 countries.

Figure 2. European Cardiovascular Research Institute foundation and its scientific advisory board. ECRI, European Cardiovascular Research Institute.

The ECRI-Cardialysis partnership is currently conducting 3 landmark investigations on the use of coronary imaging and coronary physiology to guide percutaneous coronary interventions. Up-to-date details are available on the Cardialysis website.8

A LANDMARK FIGURE

Numerous clinicians and clinical research professionals have passed through the door of Cardialysis, with some staying for a lifetime and others for a short period. Undoubtedly, the most salient contributor to the organization’s innovations and successes has been Prof. Patrick W. Serruys. His mentor, Prof. Paul Hugenholtz, acknowledged as the father of the European Society of Cardiology, and one of the founding members of Cardialysis, recognized Prof. Serruys as a natural talent and luminary in clinical research. Prof. Serruys joined Cardialysis during its early days and since then played a decisive role in the organization. His innovations and contributions included the development of coronary imaging techniques (eg, he was coinventor of quantitative coronary angiography); the establishment of best practices in interventional clinical trials, including the design and execution of the BENESTENT study,12 which was the first of its kind and remains one of the most cited publications in interventional cardiology; research in bioresorbable scaffolds; and an illustrious career that garnered multiple distinctions and awards.13 Although Prof. Serruys left the organization in 2019, his scientific legacy remains highly esteemed.

Currently, a new generation is shaping the present and future of the organization with unwavering commitment to innovation, collaborative research, and, above all, commitment to improved patient outcomes. The 40-year timeline of Cardialysis (figure 1) starts with the CARPORT trial led by Prof. Serruys from the Thoraxcenter, and concludes with the FAST II study led by Dr Joost Daemen14 and the MONITOR HF trial led by Dr Jasper Brugts,15 both also from the Thoraxcenter. While Cardialysis envisions expanding its European and global collaborations in the coming decades, its scientific partnership with EMC has remained strong and will continue to flourish.

THE FUTURE

Cardialysis pledges to continue contributing to the design, execution and reporting of clinical trials as an independent and scientifically-driven cardiovascular research organization and core laboratory. Its priorities are patient safety, data integrity, and the production of high-quality data, which have been achieved by committed employees, passionate investigators, and long-standing collaboration with its valued partners.

Additionally, Cardialysis remains committed to further advancing continued standardization of clinical trial definitions, design principles, and core laboratory methods, given that standardization has proven to be a catalyst in clinical research. Current innovations at Cardialysis focus on implementing artificial intelligence, streamlining clinical trial processes, harnessing the potential of real-world data, and mastering applicable regulatory science.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

E. Spitzer is a board member and shareholder of Cardialysis and a board member of the ECRI.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our 40th anniversary is dedicated to our beloved colleague Eline Montauban van Swijndregt†.

REFERENCES

1. Organization, review, and administration of cooperative studies (Greenberg Report):a report from the Heart Special Project Committee to the National Advisory Heart Council, May 1967. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9:137-148.

2. Spitzer E, Fanaroff AC, Gibson CM, et al. Independence of clinical events committees:A consensus statement from clinical research organizations. Am Heart J. 2022;248:120-129.

3. United States Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Clinical Trial Sponsors. Establishment and Operation of Clinical Trial Data Monitoring Committees. March 2006. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/establishment-and-operation-clinical-trial-data-monitoring-committees. Accessed 30 June 2023.

4. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54-63.

5. van Zandvoort LJC, Ali Z, Kern M, van Mieghem NM, Mintz GS, Daemen J. Improving PCI Outcomes Using Postprocedural Physiology and Intravascular Imaging. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:2415-2430.

6. Casenghi M, Popolo Rubbio A, Menicanti L, Bedogni F, Testa L. Durability of Surgical and Transcatheter Aortic Bioprostheses:A Review of the Literature. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;42:161-170.

7. United States Food and Drug Administration. Clinical Trial Imaging Endpoint Process Standards. Guidance for Industry. April 2018. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/clinical-trial-imaging-endpoint-process-standards-guidance-industry. Accessed 30 June 2023.

8. Cardialysis. Available at: www.cardialysis.nl/library/links. Accessed 2 July 2023.

9. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al;and Academic Research C. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials:a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344-2351.

10. Vranckx P, Valgimigli M, Juni P, et al;and Investigators GL. Ticagrelor plus aspirin for 1 month, followed by ticagrelor monotherapy for 23 months vs aspirin plus clopidogrel or ticagrelor for 12 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy for 12 months after implantation of a drug-eluting stent:a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392:940-949.

11. Valgimigli M, Frigoli E, Heg D, et al;and Investigators MD. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy after PCI in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1643-1655.

12. Serruys PW, de Jaegere P, Kiemeneij F, et al. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:489-495.

13. Serruys DP. Featuring:Dr Patrick Serruys. Eur Cardiol. 2018;13:80-82.

14. Masdjedi K, Tanaka N, Van Belle E, et al. Vessel fractional flow reserve (vFFR) for the assessment of stenosis severity:the FAST II study. EuroIntervention. 2022;17:1498-1505.

15. Brugts JJ, Radhoe SP, Clephas PRD, et al;investigators M-H. Remote haemodynamic monitoring of pulmonary artery pressures in patients with chronic heart failure (MONITOR-HF):a randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2023;401:2113-2123.

The article signed by García-Guimarães et al.1 recently published in REC: Interventional Cardiology is a living example of how a technical modification of a percutaneous device already being used with good clinical outcomes can have a significant impact not only from the standpoint of the parameters of technical results but also from the clinical viewpoint. Over the past 20 years of development of valves for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) procedures we have witnessed a gradual technological progression where 2 different concepts—self-expanding valves and balloon-expandable valves—have initially achieved encouraging clinical outcomes in high-risk or inoperable patients,1,2 and gradually until achieving better short-term results compared to surgical aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients.3,4 This successful trajectory is partly due to the interest for developing and improving early and successive TAVI devices. The trials conducted among high-risk patients already found a higher rate of paravalvular leak after TAVI compared to surgical repair. As a matter of fact, it was a common event very much associated with a greater need for pacemaker implantation after TAVI2 in the early self-expandable valves.

Conceptually this is something that could have been expected since there is no native valve resection or washout of the calcium remaining in the leaflets or the annulus. The need for permanent pacemaker implantation increases due to the implicit mechanism of mechanical fixation due to pressure to the valve annulus and its adjacent structures. We should mention that both phenomena can be inversely associated, that is, the more annular overexpansion we have, the more chances of atrioventricular block and vice versa with paravalvular leak. If we accept that the clinical impact of residual leak—with disparate evidence available—5,6 can be associated with different degrees categorized as mild, all design changes and those associated with the implantation technique used aim at reducing its rate and severity.

The nature and mechanisms involved with paravalvular regurgitation are obviously different compared to the native valve, which is why several authors propose more categories, and a modification of the analysis technique of transthoracic echocardiography after implantation. This aims at the proper detection of different degrees of paravalvular regurgitation with some potential adverse prognostic effect.7 The fact of the matter is that the development of TAVI devices mostly aims at reducing the degree of paravalvular leak without compromising the rate of new pacemaker implantation after TAVI, that is, without changing the degree of pressure to the native annulus. Therefore, the «skirts» surrounding the metal structure of the devices where they come into contact with the annulus are not only here to stay but come in longer lengths and have more morphological variations. The history of ACURATE neo (Boston Scientific Corporation, United States) would be a good example of how a modified skirt that is 60% longer can have a benefit that, though may seem spurious, is really a breakthrough with a potential clinical benefit like García-Guimarães et al. proved.1.

Although the study has some limitations associated with its nature like comparing 2 different, non-homogeneous historic cohorts, it demonstrates something that operators who have tried different models have already confirmed in our routine clinical practice: the segment packaging in contact with the annulus has reduced the rates of leak in TAVI. Also, it proves that designing a device should be a positively toll-free packaging: the ACURATE Neo2 valve reduces paravalvular leak without compromising the rate of pacemaker implantation as another similar study that compared 2 consecutive cohorts with the 2 consecutive models of Accurate neo already demonstrated.8

In the process of developing new devices for TAVI we have learned to study the size of aortic annuli with the computed tomography (CT) scan much better and be more accurate when adapting the size of the device that should be implanted. More technical options have come up regarding the size of the valve have become available too regarding the size of the valve, its measurement, implantation height, and even the need for pre or postdilatation. The impact of each one of these factors could be statistically figured out, although this is not an easy task between 2 different historic cohorts.

If we conduct an in-depth study of what it means to assess aortic valves with the CT scan, especially the capacity to predict the rate of paravalvular leak after TAVI, we’ll find some contradictions along the way. Although the degree or spread of calcification can seem the culprits of paravalvular regurgitation, not everything is so clear or linear. This confusion can be attributed to the different ways valvular calcium can impact the sealing of the valve based on the type (balloon-expandable or self-expanding), specific design (with or without skirt, among other), size selected, and procedural technical issues (implantation height). In the studies of coronary calcification assessed via CT scan there is variability in the technique used to quantify coronary calcium (CT without contrast or coronary computed tomography angiography [CCTA]) and the methods of analysis (threshold for the detection of coronary calcium, assessment of Agatston score or calcium volume even the outflow tract, among other).

The standard method to quantify coronary calcium includes a baseline study often before the injection of the iodinated contrast material needed to perform the cardiac and aortic CCTA. When this baseline determination is lacking, the calcium quantification used in the article signed by García-Guimarães et al.1 includes a dichotomic detection threshold based on the opacification obtained in the outflow tract of CCTA images;9,10 an easy method with an acceptable correlation that was homogeneously applied to both cohorts.

The size of the valve selected, implantation height, and the distribution of calcium both in the annulus and left ventricular outflow tract may have shared some protagonism in this study and on this regard.

Sealing limitations with TAVI compared to surgical aortic valve replacement may still persist for some time despite the advances made with the former. However, the supravalvular position of coaptation and the worse profile of the bare-metal stents vs surgical valve can be favorable assets for TAVI regarding the study of long-term durability.

Finally, although for the time being there is not a cause-effect correlation, it’s striking to see that the group with more residual leak in the aforementioned study1 and others9,10 also shows more bleeding at follow-up. It is obvious that since they’re historic cohorts, this could be due to other factors involved in the learning curve and the development of the technique like vascular access treatment or use of drugs that may affect bleeding. It could also be that the leak has deleterious rheological effects like some studies have already suggested.11

We should say that although there’s always a toll to pay with new packagings, this doesn’t seem to be the case.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

B. García del Blanco is a proctor for Edwards, and has declared to have received funding for counselling jobs for Medtronic, and Boston Scientific. H. Cuéllar Calabria declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

REFERENCES

1. García-Guimarães M, Van Ginkel D-J, Rensing BJ, et al. Paravalvular leak with ACURATE neo and neo2: a comparative study with calcium quantification. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:170-177.

2. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1597-1607.

3. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. PARTNER 3 Investigators. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

4. Reardon MJ, Adams DH, Kleiman NS, et al. 2-Year Outcomes in Patients Undergoing Surgical or Self-Expanding Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:113-121.

5. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706-1715.

6. Athappan G, Patvardhan E, Tuzcu EM, et al. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of aortic regurgitation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: meta-analysis and systematic review of literature. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1585-1595.

7. Ando T, Briasoulis A, Telila T, Afonso L, Grines CL, Takagi H. Does mild paravalvular regurgitation post transcatheter aortic valve implantation affect survival? A meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:135-147.

8. Jones BM, Tuzcu EM, Krishnaswamy A, et al. Prognostic significance of mild aortic regurgitation in predicting mortality after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152:783-790.

9. Angelillis M, Costa G, De Backer O, et al. Threshold for calcium volume evaluation in patients with aortic valve stenosis: correlation with Agatston score. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2021;22:496-502.

10. Kim WK, Eckel C, Renker M, et al. Comparison of the Acurate Neo Vs Neo2 Transcatheter Heart Valves. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E804-E810.

11. Mehran R, Sorrentino S, Claessen BE. Paravalvular Leak: An Interesting Interplay of Acquired vWF-Disease and Late Bleeding After TAVR. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2149-2151.

The time has come. Over the past few years, we have been living a constant increase in the number of patients with aortic stenosis who are treated with transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Although the latest indications of the clinical practice guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology1 are somehow more restrictive than those of the American College of Cardiology2 regarding age cut-offs and surgical risk we’ve seen a growing demand for TAVI in low-risk patients and, progressively, in younger patients in almost all anatomical settings.

Up until now, randomized clinical trials had mostly focused on comparing the TAVI technique to conventional aortic valve replacement surgery.3,4 And although these studies with different models of transcatheter aortic valves laid the foundation for the indications published by the guidelines, very few of them make head-to-head comparisons among the different TAVI models currently available. As a matter of fact, most are observational, non-randomized or non-inferiority clinical trials. On the other hand, the variability of the different models currently available has been growing with technological advances to perform easier, safer, and more durable transcatheter heart valves. However, can we assume that there will be some sort of class effect in all TAVI models currently available?

In an article recently published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Elnaggar et al.5 compared 2 models of top transcatheter heart valves currently available (the Evolut PRO, Medtronic, United States, and the SAPIEN 3, Edwards Lifesciences, United States) using an easy randomized design. Although the study has significant limitations (a rather clinical compared to methodological protocol), it seems reasonable to start discussing whether the different TAVI models available have similar results in non-selected and randomized populations. As it occurred with coronary stents, presumably in no time, we’ll be seeing more comparative trials like this studying not TAVI vs surgery, but TAVI vs TAVI in different clinical and anatomical settings. In the study conducted by Elnaggar et al.5 no significant differences regarding in-hospital mortality between both models were seen, but a difference regarding paravalvular leak favorable to the SAPIEN 3 vs the Evolut PRO device in a population not previously screened through coronary computed tomography angiography. As described in the methodology and further discussion, the method used in the study to assess annular size and anatomy was unusual. The protocol included an intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography plus in-situ balloon inflation to measure the annulus and select the size of the valve based on the coverage index. This may have impacted implantation results following size selection and coronary artery calcium assessment as predictors of paravalvular leak, and not based on today’s gold standard (computed tomography). Regarding the need for pacemaker implantation after TAVI, the authors say that this difference was not significant (7.1% vs 5.8% favorable to the SAPIEN 3) although a difference was seen in the rate of baseline right branch bundle block (16.9% in the SAPIEN 3 group vs 0% in the Evolut PRO group). Therefore, we should mention that the baseline population was more favorable regarding the predictors of pacemaker implantation in the Evolut PRO compared to the SAPIEN 3. The latter, however, showed a lower—although not statistically significant—absolute rate of pacemaker implantation. Finally, the composite endpoint defined by the authors as device success was favorable to the SAPIEN 3 (98%) vs the Evolut PRO (86%) and included lack of mortality, paravalvular leak grade ≥ II at discharge, the need for a second valve, conversion to surgical aortic valve replacement or valve embolization. The study focused on procedural results with a follow-up limited to the length of stay (median of 7 days).

In any case, and beyond any methodological constraints, comparative trials show the strengths and weaknesses of different transcatheter aortic valve models even with experienced operators, which probably debunks the theory that a single model in expert hands fits every patient. If we want excellent results in patients and longer life expectancies, we’ll probably need to profit from what each model has to offer depending on the patient’s anatomy. Also, in high-volume centers that treat young or low-risk patients, the use of different TAVI models should be mandatory for better valve selection regarding the patients’ clinical and anatomical characteristics. As a matter of fact, there is compelling evidence that the hemodynamics of supra-annular models is better compared to that of annular coaptation models, especially, in small annuli6,7 or that, with a significant load of calcium, latest generation balloon-expandable models have better results regarding paravalvular leak,8 etc. Still, several questions remain unanswered that can all be summarized in the headline of this editorial: is there a class effect in all TAVI models currently available?

In view of the reports that compare the results of different models,9,10 similar immediate results are likely during primoimplantation with all of them since the technique is highly reproducible. However, like we said before, the population where indications are trying to be expanded requires excellent results and small differences that seem irrelevant in absolute terms but are very important in this context of excellence if we want TAVI to become the gold standard to treat aortic stenosis regardless of age and surgical risk. Considering the durability data available to this date (median of nearly 8 years)11 when offering this therapy to young patients with longer life expectancies compared to this expected durability, the term «lifetime plan» comes into play. Now the index TAVI needs much more than excellent results regarding severe cardiovascular complications, paravalvular leak, need for pacemaker implantation or rate of stroke. Now, valve selection needs to be planned and carefully individualized to better suit the patient’s anatomy anticipating a possible second TAVI in the future (TAVI-in-TAVI). Come to this point, very few will still advocate for class effect. The different designs and adaptations made to the patient’s anatomy will be key in a crucial aspect regarding planning a second procedure years after the index one: access to coronary arteries following the risk of sinus sequestration or occlusion due to outer skirts and height of the first and second valves. This is where intra- or supra-annular designs, the valve total height, strut amplitude, the possibility of commissural alignment, laceration techniques, prosthesis-patient mismatch, etc. come into play. In conclusion, a significant combination of factors that still need to be studied before answering some of these questions. Undoubtedly, virtual, and three-dimensional simulation technologies play a key role in research and clinical application with decision-making algorithms to choose the best alternative for our patients. Therefore, former studies have already discussed these aspects while trying to elucidate how different models behave in this complex TAVI-in-TAVI setting.12 Also, comparisons have been made with surgical explantation of TAVI with structural failure.13,14 Currently, the rate of these events is not high, but the most plausible thing is that as the patients’ mean age drops, the rate of valve degeneration will increase parallel to the need for dealing with this problem.

All things considered it seems highly likely that there will be no class effect in TAVI considering how different the designs currently available behave beyond implantation. There is, however, great reproducibility of the transfemoral transcatheter technique with excellent short- and mid-term results. Some questions remain, though, on the long-term outcomes that will surely be answered as scientific evidence as it has been the case since this technique was born 20 years ago.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

C.A. Urbano Carrillo is a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences and participates in consulting groups for Medtronic España.

REFERENCES

1. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al.; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

2. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e35-e71.

3. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al.; PARTNER 3 Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

4. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al.; Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators. Low risk trial, transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706-1715.

5. Elnaggar HM, Schoels W, Mahmoud MS, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation using Evolut PRO versus SAPIEN 3 valves: a randomized comparative trial. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5(2):94-101.

6. Schmidt S, Fortmeier V, Ludwig S, et al. Hemodynamics of self-expanding versus balloon-expandable transcatheter heart valves in relation to native aortic annulus anatomy. Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111:1336-1347.

7. Abdelghani M, Mankerious N, Allali A, et al. Bioprosthetic Valve Performance After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With Self-Expanding Versus Balloon-Expandable Valves in Large Versus Small Aortic Valve Annuli: Insights From the CHOICE Trial and the CHOICE-Extend Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2507-2518.

8. Abdel-Wahab M, Mehilli J, Frerker C, et al. Comparison of balloon-expandable vs self-expandable valves in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2014;311:1503-1514.

9. Webb J, Wood D, Sathananthan J, Landes U. Balloon-expandable or self-expandable transcatheter heart valves. Which are best? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1900-1902.

10. Pagnesi M, Kim WK, Conradi L, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement With Next-Generation Self-Expanding Devices: A Multicenter, Retrospective, Propensity-Matched Comparison of Evolut PRO Versus Acurate neo Transcatheter Heart Valves. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:433-443.

11. Blackman DJ, Saraf S, MacCarthy PA, et al. Long-Term Durability of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Prostheses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:537-545.

12. Meier D, Akodad M, Landes U, et al. Coronary access following redo TAVR. Impact of THV design, implant technique, and cell misalignment. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2022;15:1519-1531.

13. Bapat VN, Zaid S, Fukuhara S, et al.; EXPLANT-TAVR Investigators. Surgical Explantation After TAVR Failure: Mid-Term Outcomes From the EXPLANT-TAVR International Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1978-1991.

14. Fukuhara S, Nguyen CTN, Yang B, et al. Surgical Explantation of Transcatheter Aortic Bioprostheses: Balloon vs Self-Expandable Devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113:138-145.

Two decades of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) changed the history of contemporary medicine and became a reference model in cardiovascular disease. Percutaneous structural heart disease (SHD) therapies emerged to treat the entire heart valve and vessel spectrum, as well as congenital or acquired wall and muscular defects.

(R)evolution happened back in 2002 with Alain Cribier’s human aortic valve disease percutaneous milestone treatment.1 A progressive and impressive range of therapeutic alternatives for patients grew parallel to the population’s longevity given the most prevalent etiology of aortic stenosis is degenerative. In fact, cardiovascular diseases remain the leading causes of death and hospitalization and represent an enormous clinical and public health burden, which disproportionately affects older adults. The World Health Organization expects octogenarians to quadruple up to 396 million by 2050. Although rheumatic heart disease has become rare in industrialized countries, its overall burden is still significant. It comes as no surprise that complex patients who can benefit from combined valvular procedures are increasingly common.

The TAVI impact on cardiology and cardiac surgery surpassed the clinical field and imposed a restructure as the path taken in aortic valve disease is transposed, progressively, to other structural clinical areas, namely mitral, tricuspid, and acute stroke prevention.

WHAT’S THE STORY?

Initially, safety and efficacy were the main requirements for TAVI, same as for any other cardiovascular technique. Mortality and complications were important from a clinical point of view resulting in prolonged admissions and increased hospital costs. Intensive use of imaging and general anesthesia were the default procedure for most. Patient selection became the concern and frailty assessment, risk stratification, futility, and the imponderables were the main issues. Bench simulation provided relevant information while studies and registries depicted the actual TAVI expression across countries.2-4

Progressively, innovative techniques and devices led to cautious simplified protocols that run parallel to image expertise replication in the non-aortic space, especially in the mitral valves. Patient subgroups were the main topic, namely the history of cardiac valve surgery –aortic, mitral, and tricuspid– as well as octogenarians. The economic burden of incremental cost on health economics emerged as a concern, as well as device selection, hybrid techniques, alternative access routes, and standardized approaches for complications. Concomitant medical therapy and longevity were also captured.5,6

Therefore, the field of aortic procedures expanded, grew, and consolidated. TAVI procedures became daily routine with hands-on training for fellows. The need for preparing interventional cardiologists for this area became clear, which was reflected in industry proctoring programs and by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Core Curriculum. Simultaneously, expansion to other SHD areas like percutaneous mitral and tricuspid valve procedures, left atrial appendage and valve leak closures emerged from this maturity as a natural (r)evolution in the field of SHD.7-10

WHAT DID WE LEARN?

Aortic valve procedures reflect, first, contemporary longevity and modern medicine. Their expansion constitutes a role model in cardiology and cardiac surgery by inducing changes adopted in other SHD areas.

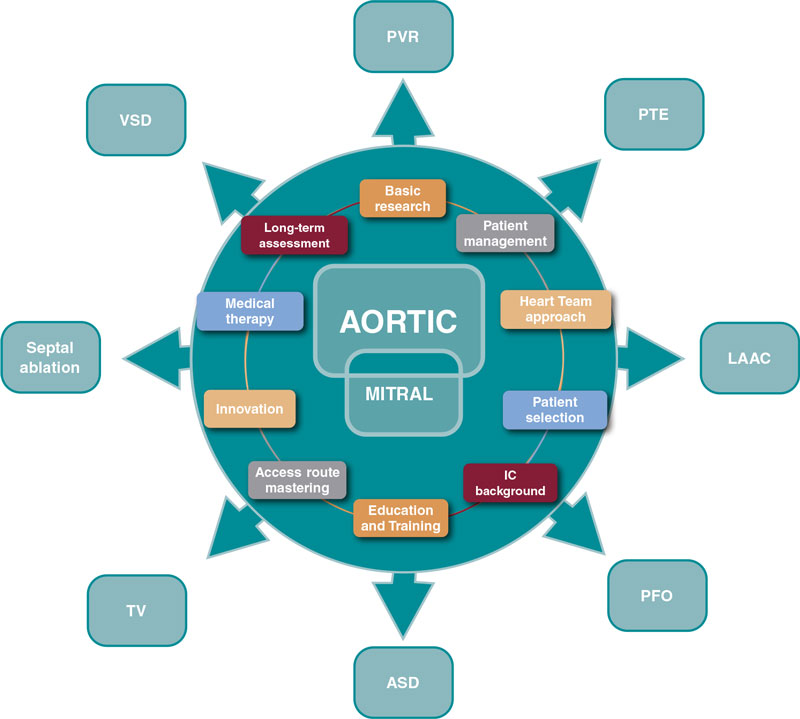

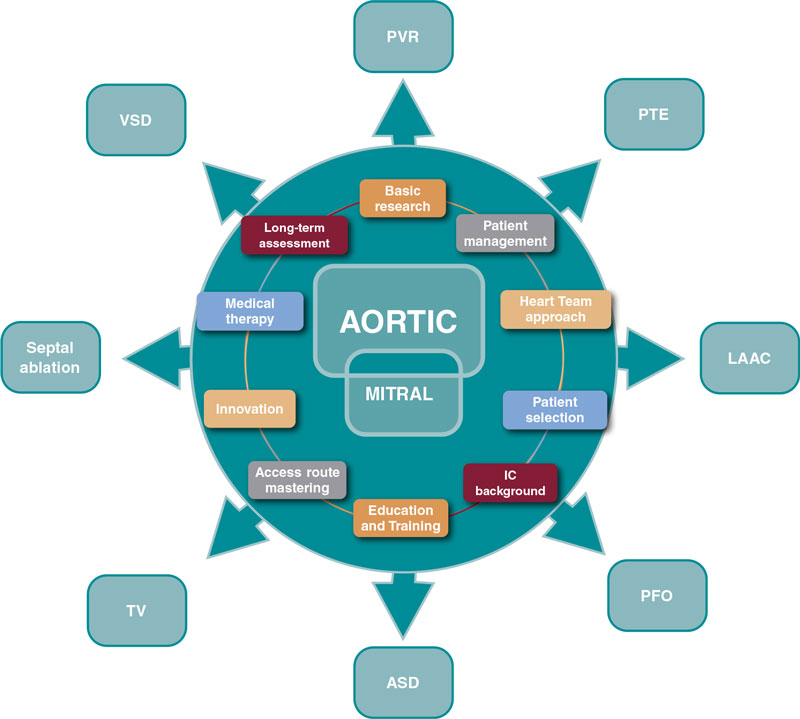

Several SHD procedures have the extraordinary ability to ameliorate heart failure, prevent and treat thromboembolic diseases, and improve survival.11 We should recognize and acknowledge the common features that bring their current prestige, success, and expansion. Among immense factors, the following may be considered the most relevant:

- – Basic research

- – Comprehensive patient management

- – Multidisciplinary approach

- – Patient and subset selection

- – Access route mastering

- – Interventional cardiology background

- – Device iteration and innovation

- – Structured education and training

- – Complementary medical therapy

- – Long-term assessment of care and outcomes

Progress is endless and these are valuable assets to guide the next steps (figure 1).

Figure 1. Influence of aortic and mitral procedures in structural heart disease. ASD, atrial septal defect; IC, interventional cardiology; LAAC, left atrial appendage closure; PFO, patent foramen ovale; PTE, pulmonary thromboembolism; PVR, paravalvular regurgitation; TV, tricuspid valve; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

WHAT DOES THE FUTURE LOOK LIKE?

Physicians, caretakers, industry, and policy makers conquered a huge responsibility in the field of SHD.

To match societal and patient’s expectations, the interventional cardiologist needs a holistic approach:

- – To define the role of SHD interventional cardiologists. As a medical cardiologist who manages patients from diagnosis to follow-up of SHD and performs percutaneous procedures in this domain. As members of heart teams that interact closely with other cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and other medical specialties, nurses, paramedics, and other healthcare professionals.11 All these considerations are based on the EAPCI Core Curriculum of 2020 and on the upcoming EAPCI Core Curriculum on percutaneous SHD procedures (submitted for publication).10

- – To harmonize SHD interventional cardiology practice. Data from health surveys, administrative records, cohort studies, and registries show persisting geographic inequity across Europe. The EAPCI certification that includes a national mutual recognition system, attempts to validate a proper level of knowledge and practice to protect patients from undergoing interventional cardiology procedures performed by unqualified professionals and set up a European standard for competency and excellence in this field.10

- – To promote and assess quality of care by adopting standardized data definitions for the quantification of quality of care and outcomes. Recently, the EuroHeart methodology reached consensus on a set of variables, 93 categorized as mandatory (level 1) and 113 as additional (level 2) based on their clinical importance and feasibility.11 That facilitates quality improvement, observational research, registry-based randomized trials, benchmarking and post-marketing surveillance of devices, and pharmacotherapies.12

- – To perform TAVI in centers without permanent onsite cardiac surgery by establishing straight-forward protocols that provide patient safety and ensure that both operators and hospitals are committed to high quality outcomes. Though TAVI in centers without permanent onsite cardiac surgery is not endorsed at present, the dramatic growth of candidates outpaced the efforts, prompting increased waiting times with negative and severe clinical consequences. Models should include an optimal heart team around the patient from periodic visiting teams to an overall exchange partnership.13,14

- – To expand SHD procedures to low-risk and/or younger patients who present distinct challenges in their stratification, comorbidities, clinical presentation, anatomy, and potential longevity supported by recent trials. Also, by promoting responsible research and enhancing patient-centered solutions.14

- – To develop awareness regarding valvular heart disease since it is not commonly acknowledged by the population and because aortic, mitral, and tricuspid valves present overlapping functions, and differences regarding diagnostic and therapeutic methods. The EAPCI Valve for Life initiative detects barriers, identifies stakeholders, and implements strategic plans to overcome difficulties in different areas.15

- – To provide the referral network a simple, expeditious, and efficient articulation from the patient and the referring physician perspective by deploying and/or developing dedicated information technology solutions for treatment pathways and reshaping the future cardiovascular department (eg, by fusion or rotative leadership between cardiology and surgery).

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, percutaneous SHD procedures are highly demanding and rewarding. Lessons from the past are precious and interventional cardiology must use them wisely as access and volume are increasing significantly. A comprehensive approach is warranted to face this surge.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Campante Teles declared no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Cribier A. Development of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI): a 20-year odyssey. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2012;105:146-152.

2. López-Otero D, Teles R, Gómez-Hospital JA, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation: Safety and effectiveness of the treatment of degenerated aortic homograft. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2012;65:350-355.

3. Simonato M, Azadani AN, Webb J, et al. In vitro evaluation of implantation depth in valve-in-valve using different transcatheter heart valves. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:909-17.

4. Mylotte D, Osnabrugge RLJ, Windecker S, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in Europe: Adoption trends and factors influencing device utilization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:210-219.

5. Ruggeri M, Donatella M, Federica C, et al. The transcatheter aortic valve implantation: an assessment of the generalizability of the economic evidences following a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2022;38:e27.

6. Van Gils L, Tchetche D, Latib A, et al. TAVI with current CE-marked devices: Strategies for optimal sizing and valve delivery. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:Y22-Y27.

7. Simonato M, Whisenant B, Ribeiro HB, et al. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement after surgical repair or replacement comprehensive midterm evaluation of valve-in-valve and valve-in-ring implantation from the VIVID registry. Circulation. 2021:104-116.

8. Gandaglia A, Bagno A, Naso F, Spina M, Gerosa G. Cells, scaffolds and bioreactors for tissue-engineered heart valves: A journey from basic concepts to contemporary developmental innovations. Eur J Cardio-thoracic Surg. 2011;39:523-531.

9. Agricola E, Ancona F, Brochet E, et al. The structural heart disease interventional imager rationale, skills and training: a position paper of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;22:471-479.

10. Van Belle E, Teles RC, Pyxaras SA, et al. EAPCI Core Curriculum for Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (2020): Committee for Education and Training European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). A branch of the European Society of Cardiology. EuroIntervention. 2021;17:23-31.

11. Aktaa S, Batra G, James SK, et al. Data standards for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the European Unified Registries for Heart Care Evaluation and Randomised Trials (EuroHeart). Eur Hear J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;qcac063.

12. Guerreiro C, Ferreira PC, Teles RC, et al. Short and long-term clinical impact of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Portugal according to different access routes: Data from the Portuguese National Registry of TAVI. Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39:705–717.

13. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021:1-72.

14. Foglietta M, Radico F, Appignani M, Aquilani R, Di Fulvio M, Zimarino M. On site cardiac surgery for structural heart interventions: a fence to mend? Eur Heart J Suppl. 2022;24(Supplement_I):I201-I205.

15. Windecker S, Haude M, Baumbach A. Introducing a new EAPCI programme: The Valve for Life initiative. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:977-979.

- Ischemic postconditioning and duration of previous ischemia

- Current state of knowledge on the use of drug-coated balloon in coronary bifurcation lesions

- 3D quantitative coronary angiography based vessel FFR: clinical evidence and future perspectives

- Complete revascularization and diabetes in the real world: observational data as a necessary addition to clinical trials

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

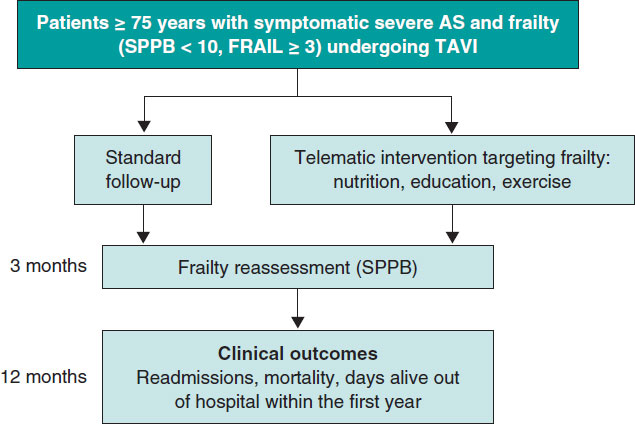

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España