Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

The use of drug-eluting stents (DES) for the treatment of coronary artery stenosis substantially reduced the need for repeat revascularization compared to bare-metal stents.1 However, as many patients undergoing stenting have long life expectancy, and the incidence rate of stent failure increases with time since implantation, the number of patients presenting with DES restenosis is not insignificant and the treatment of these patients remains a challenge.2

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend treatment of restenosis associated with angina or ischemia by repeat revascularization with either repeat stenting with DES or angioplasty with drug coated balloon (DCB).3 Certain situations favour repeat stenting with DES, most notably loss of mechanical integrity of the restenosed stent. In general, however, although repeat stenting with DES may be more effective than angioplasty with DCB in the short-to-medium-term,4 avoidance of additional stent layers is an important consideration in the longer-term. Indeed, many centres prefer DCB angioplasty as a first-line approach for the treatment of restenosis in the absence of a compelling indication for repeat stenting.

The efficacy of DCB treatment relies on rapid transfer and subsequent tissue retention of the anti-proliferative agent, which is necessary for a persistent suppression of cell proliferation.5 Preclinical data suggest that micro-injuries to the vessel wall may enhance the ability of DCBs to inhibit neointimal growth.6 These micro-injuries can be achieved with a number of different types of modified balloon catheters, such as cutting or scoring balloons. Cutting balloon angioplasty is an attractive option thanks to its ability to effectively incise neointimal tissue and its ease of use.7 Scoring balloons are based on the same principle and may offer superior flexibility and deliverability at the expense of a somehow lower plaque disruption.

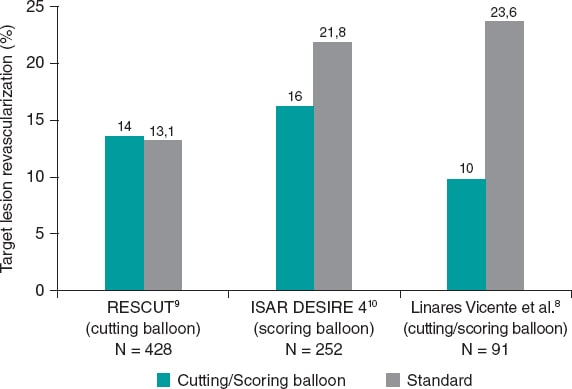

In a recent paper published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Linares Vicente et al. reported on the 5-year results of cutting or scoring balloon angioplasty combined with DCB to treat in-stent restenosis.8 A total of 51 lesions (42 patients) were treated with cutting balloons plus DCBs, and 56 lesions (49 patients) with a standard DCB angioplasty. Both the SeQuent Please (B. Braun Melsungen AG, Germany), and the Pantera Lux (Biotronik, Switzerland) balloons were used. The primary endpoint was clinically driven target lesion revascularization at 5 years. It appears that, compared to the standard DCB strategy, the use of cutting or scoring balloons considerably reduced the 5-year rate of target lesion revascularization, although this difference was not statistically significant (9.8% vs 23.6%; odds ratio = 0.36; 95% confidence interval, 0.19-1.09; P = .05) (figure 1).

Figure 1. Target lesion revascularization (%): studies comparing cutting balloon/scoring balloon vs standard therapy in patients treated with percutaneous intervention for in-stent restenosis.

The study was retrospective and conducted at a single center with a small sample size of 91 patients. However, it is representative of real-world evidence, which may reflect clinical experiences across a broader and more diverse population of patients than those enrolled in randomized controlled trials. Regarding the baseline characteristics, almost 85% of patients were men with a mean age of 68.3 years. Patients had a high prevalence of diabetes mellitus and smoking (36% and 59%, respectively).

Interestingly, despite the current recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology,3 the use of intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography was relatively low (5.9% in the cutting balloon group, and 8.9% in the standard group). Although this is consistent with rates observed in surveys of use in the clinical practice,11 it represents a missed opportunity for the mechanistic understanding of the disease etiology, and guidance for treatment optimization.12

The primary endpoint was the need for clinically driven target lesion revascularization at 5 years, which was 64% lower with cutting or scoring balloon angioplasty. Given the small sample size of this study and the relatively large treatment effect, it is a pity that insights from the angiographic follow-up were not available. Concordant data from systematic surveillance angiography would have given more confidence to the robustness of the observed treatment effect.

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of earlier randomized controlled trials with cutting or scoring balloon angioplasty. In fact, evidence from such trials is scant including the RESCUT (Restenosis cutting balloon evaluation trial) trial9 published in 2003, and the more recent ISAR DESIRE 4 (Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: optimizing treatment of drug-eluting stent in-stent restenosis 4) trial.10

In RESCUT, Albiero et al. randomized 428 patients with bare-metal stent in-stent restenosis across 23 European centers to receive either cutting balloon angioplasty or conventional balloon angioplasty.9 Overall, the trial showed neutral results: at late follow-up, the angiographic restenosis rate, minimal lumen diameter, and the rate of clinical events were similar in both arms (figure 1). Cutting balloon angioplasty, however, was associated with some important procedural advantages, such as use of fewer balloons, less requirement for additional stenting, and a significantly lower incidence of balloon slippage (6.5% vs 25%).

ISAR DESIRE 4 was a randomized, open-label, assessor-blinded trial that enrolled 252 patients with clinically significant DES restenosis undergoing DCB angioplasty at 4 different centres in Germany.10 This trial investigated scoring balloon rather than cutting balloon angioplasty. The primary endpoint–diameter stenosis at the 6-8-month follow-up angiography–was lower for the scoring balloon compared to the regular balloon angioplasty: 35% vs 40.4%; P = .047; in addition, target lesion revascularization was numerically lower (figure 1). Although, the size of treatment effect was modest, small incremental gains in efficacy in this challenging patient subset may translate into important clinical benefits.

Against this background, the observations made by Linares Vicente et al.8 are an important addition to the evidence supporting the clinical use of cutting or scoring balloons to treat stent failure. While repeat stenting with DES or angioplasty with DCB are the mainstay of in-stent restenosis procedures, the procedural efficiency and clinical efficacy of both approaches will likely improve with the adjunctive use of cutting or scoring balloons. The benefits of these devices are most likely mediated by a combination of factors: reduced balloon slippage (or watermelon-seeding), the mechanical advantage of increased disruption of restenotic tissue, and the potential for enhanced efficacy of the device-delivered drug. The management of patients with stent failure remains challenging and deserves the best treatment the operator can offer including the liberal use of cutting or scoring balloon lesion preparation. In this clinical setting, small margins can make a big difference.

FUNDING

L. McGovern is funded by the European Commission under the Horizons 2020 framework (grant agreement number 965246 CORE-MD).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R.A. Byrne declared research or educational funding in the institution he currently works at from Abbott Vascular, Biosensors, Biotronik, and Boston Scientific. L. McGovern declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

REFERENCES

1. Cassese S, Byrne RA, Tada T, et al. Incidence and predictors of restenosis after coronary stenting in 10 004 patients with surveillance angiography. Heart. 2014;100:153-159.

2. Cutlip DE, Chhabra AG, Baim DS, et al. Beyond Restenosis. Circulation. 2004;110:1226-1230.

3. Neumann F-J, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2018;40:87-165.

4. Giacoppo D, Alfonso F, Xu B, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty vs. drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis:a comprehensive, collaborative, individual patient data meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials (DAEDALUS study). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3715-3728.

5. Byrne RA, Joner M, Alfonso F, Kastrati A. Drug-coated balloon therapy in coronary and peripheral artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:13-23.

6. Radke PW, Joner M, Joost A, et al. Vascular effects of paclitaxel following drug-eluting balloon angioplasty in a porcine coronary model:the importance of excipients. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:730-737.

7. Barath P, Fishbein MC, Vari S, Forrester JS. Cutting balloon:A novel approach to percutaneous angioplasty. Am J Cardiol. 1991;68:1249-1252.

8. Linares Vicente JA, Ruiz Arroyo JR, Lukic A, et al. 5-year results of cutting or scoring balloon before drug-eluting balloon to treat in-stent restenosis. REC Interv Cardiol. 2022;4:6-11.

9. Albiero R, Silber S, Di Mario C, et al. Cutting balloon versus conventional balloon angioplasty for the treatment of in-stent restenosis:Results of the restenosis cutting balloon evaluation trial (RESCUT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:943-949.

10. Kufner S, Joner M, Schneider S, et al. Neointimal Modification With Scoring Balloon and Efficacy of Drug-Coated Balloon Therapy in Patients With Restenosis in Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents:A Randomized Controlled Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1332-1340.

11. Koskinas KC, Nakamura M, Raber L, et al. Current use of intracoronary imaging in interventional practice - Results of a European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) and Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Interventions and Therapeutics (CVIT) Clinical Practice Survey. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e475-e484.

12. Alfonso F, Sandoval J, Cárdenas A, Medina M, Cuevas C, Gonzalo N. Optical coherence tomography:from research to clinical application. Minerva Med. 2012;103:441-464.

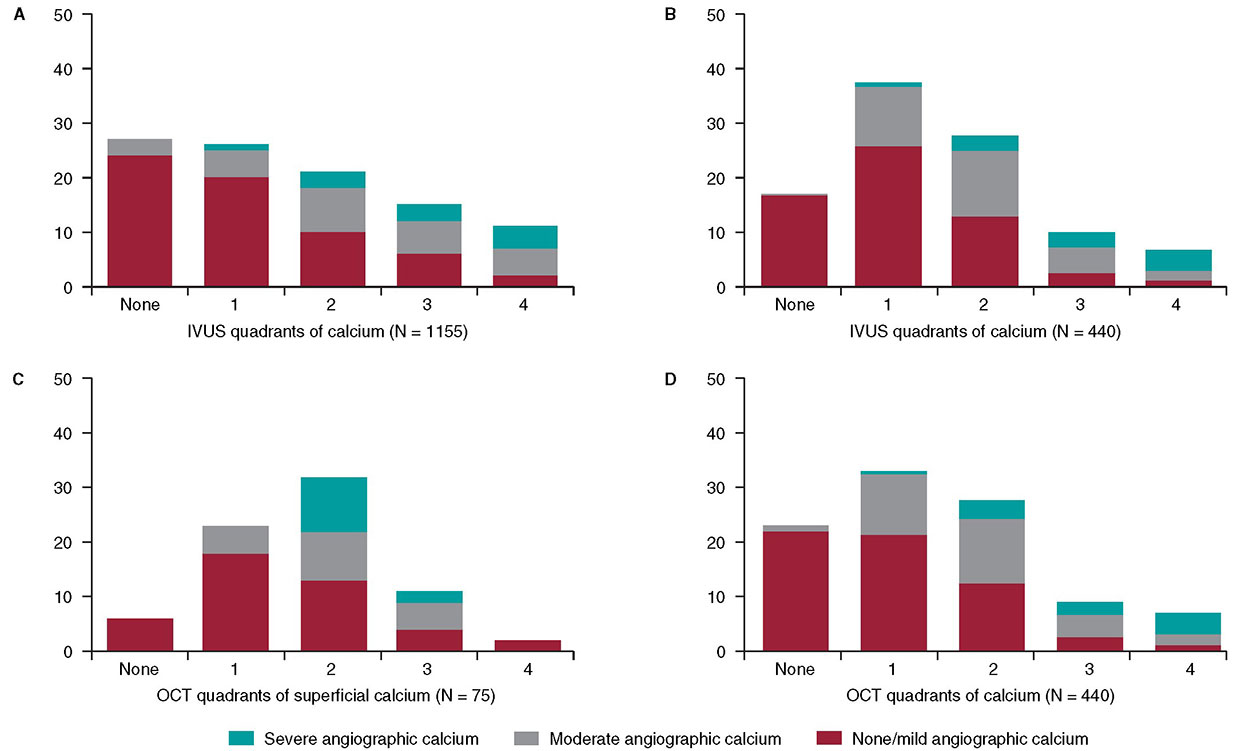

In 1995, my colleagues and I at the Washington Hospital Center (Washington, DC, United States) published an intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) vs angiographic assessment of calcium in 1155 lesions targeted for percutaneous coronary intervention (figure 1)1. Angiography detected calcium in 440 lesions (38%), but IVUS detected lesion calcium in 841 lesions (73%). Among these 1155 lesions, 27% had no IVUS calcium, 26% had 1-quadrant IVUS calcium, 21% had 2 quadrants, 15% had 3 quadrants, and 11% had 4-quadrant IVUS calcium. When present, target lesion calcium was only superficial in 48%, only deep in 28%, and both superficial and deep in 24%. Therefore, some superficial calcium was present in 72% of the 841 calcium-containing lesions (1-quadrant superficial calcium in 35%, 2 quadrants in 31%, 3 quadrants in 18%, and 4-quadrant superficial calcium in 18%). The diagnostic ability of angiography to detect calcium was primarily dependent on the arc and length of calcium, but also on whether calcium was or not superficial (figure 1). However, there was also a curious 10% rate of angiographic false positives attributed to the difficulty differentiating perivascular or reference segment calcium from intralesional calcium. However, it was never clear whether there was a systematic problem with angiographic calcium detection or whether it was because, in the early 1990s, angiography was primitive compared to today and would improve over time.

Figure 1. A total of 3 studies (clockwise starting in the upper left-hand corner) comparing intravascular imaging to the angiography detection of coronary lesion calcium. A: the study conducted by Mintz et al.1 from 1995. B and C: the study by Wang et al.2 from 2017. D: the study by McGuire et al.3 from 2021. IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

This experiment was repeated more than 20 years later by Wang et al. in a smaller cohort of 440 lesions using state-of-the-art angiographic equipment and both IVUS and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging (figure 1).2 Any amount of calcium was detected by coronary angiography in 40.2% (177 of 440) of the lesions, by IVUS in 82.7% (364 of 440) of the lesions, and by OCT in 76.8% (338 of 440) of the lesions. Notably and compared to the 1995 study, almost all calcium was superficial, fewer lesions had no calcium, and more lesions had 1- or 2-quadrant calcium (figure 1). In 13.2% of the lesions with IVUS-detected calcium, calcium was not visible by OCT mostly because of attenuation due to superficial lipid plaque accumulation. In a recent paper published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, McGuire et al.3 compared angiographic vs OCT calcium detection in 75 lesions. OCT detected calcium in 69 lesions vs 30 lesions by angiography with no angiographic false positives (figure 1).3 Compared to IVUS, OCT can measure the thickness, area, and volume that affect the angiographic detection of calcium in addition to its arc and length.2,3

Other than a reduced rate of false positives in the 2 contemporary studies, which could be attributed to the improved resolution of modern x-ray equipment, the lower x-ray doses being used today vs 1995, and the clinical recognition of the existence perivascular calcium, the results were remarkably similar to those of 1995. Thus, there appears to be a fundamental limitation to x-ray that cannot be improved by technological advances.

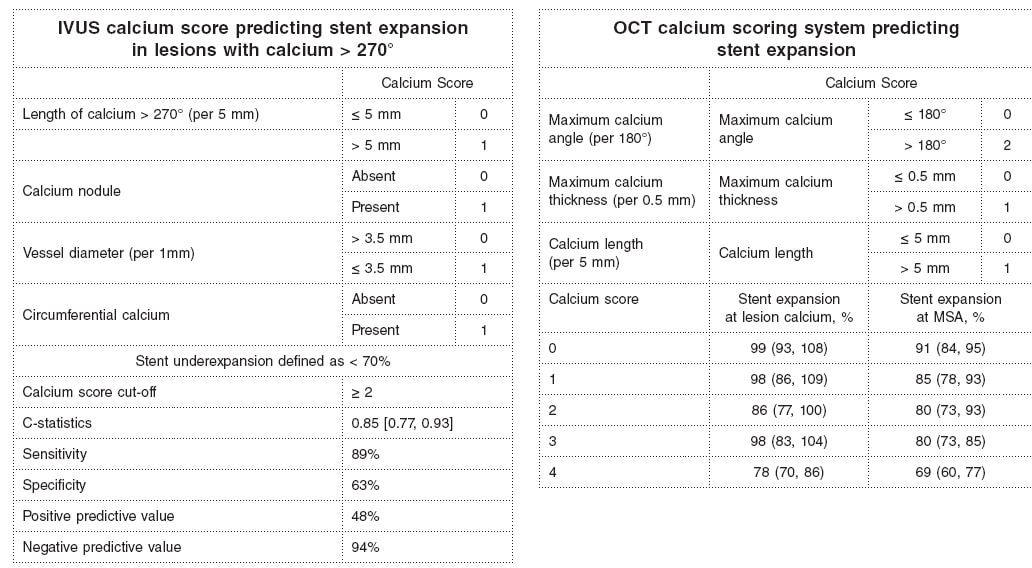

Why is calcium detection so important? The primary cause of in-stent restenosis is stent underexpansion, the primary cause of stent underexpansion is calcium, and the natural history of in-stent restenosis is not benign with an annual mortality rate of 5% to 7% (associated with treatment and at the follow-up).4-7 There are calcium scores for both OCT and IVUS that reliably predict calcium-related stent underexpansion (figure 2);8,9 and there are technologies and approaches that can be used to modify calcium to promote a better stent expansion.4,10

Figure 2. Intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography calcium scores to predict stent underexpansion.8,9 IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MSA, minimum stent area; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

There are predictors of target lesion calcium at patient level (older age, non-insulin treated diabetes, stable angina rather than an acute coronary syndrome, chronic kidney disease—especially if a patient is on dialysis—, and calcium elsewhere in the coronary tree), and predictors at lesion level too (smaller vessels, more severe stenoses).11-15 However, for the most part, lesions behave independently with regards to calcium accumulation. Only intravascular imaging can reliably detect and quantify target lesion calcium and predict stent underexpansion in the severe target lesion calcium setting.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

G.S. Mintz declares having received honoraria from BostonScientific, Philips, Medtronic, and Abiomed outside the present work.

REFERENCES

1. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, et al. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995;91:1959-1965.

2. Wang Z, Matsumura M, Mintz GS, et al. In vivo calcium detection by comparing optical coherence tomography, intravascular ultrasound, and angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:869-879.

3. McGuire C, Shlofmitz E, Melaku GD, et al. Comparison of quantitative calcium parameters in optical coherence tomography and invasive coronary angiography. REC Interv Cardiol. 2022;4:6-11.

4. Mintz GS, Ali ZA, Maehara A. Use of intracoronary imaging to guide optimal percutaneous coronary intervention procedures and outcomes. Heart. 2021;107:755-764.

5. Wiebe J, Kuna C, Ibrahim T, et al. Long-term prognostic impact of restenosis of the unprotected left main coronary artery requiring repeat revascularization. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2266-2274.

6. Tamez H, Secemsky EA, Valsdottir LR, et al. Long-term outcomes of percutaneous coronary intervention for in-stent restenosis among Medicare beneficiaries. EuroIntervention. 2021;17:e380-e387.

7. Shlofmitz E, Torguson R, Zhang C, et al. Impact of intravascular ultrasound on Outcomes following PErcutaneous coronary interventioN for In-stent Restenosis (iOPEN-ISR study). Int J Cardiol. 2021 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.08.003.

8. Fujino A, Mintz GS, Matsumura M, et al. A new optical coherence tomography-based calcium scoring system to predict stent underexpansion. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:e2182-e2189.

9. Zhang M, Matsumura M, Usui E, et al. Intravascular ultrasound-derived calcium score to predict stent expansion in severely calcified lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010296.

10. De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Banning AP. Management of calcific coronary artery lesions:Is it time to change our interventional therapeutic approach?JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1465-1478.

11. Mintz GS, Pichard AD, Popma JJ, et al. Determinants and correlates of target lesion calcium in coronary artery disease:a clinical, angiographic and intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:268-274.

12. Mintz GS, Pichard AD, Kent KM, Satler LF, Popma JJ, Leon MB. Interrelation of coronary angiographic reference lumen size and intravascular ultrasound target lesion calcium. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:387-391.

13. Tuzcu EM, Berklap B, DeFranco AC, et al. The dilemma of diagnosing coronary calcification:angiography versus intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:832-838.

14. Gruberg L, Rai P, Mintz GS, et al. Impact of renal function on coronary plaque morphology and morphometry in patients with chronic renal insufficiency as determined by intravascular ultrasound volumetric analysis. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:892-896.

15. Chin CY, Matsumura M, Maehara A, et al. Coronary plaque characteristics in hemodialysis-dependent patients as assessed by optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:1313-1319.

The arrival of drug-eluting stents (DES) nearly 2 decades ago ignited a revolution in the field of interventional cardiology. The addition of antiproliferative drugs to the stent platform reduced the rate of in-stent restenosis significantly and increased the number of patients that, to this date, have benefited from percutaneous revascularization.1,2 However, its Achilles tendon was initially the higher rate of late stent thrombosis involved. The permanent polymer used in the first generation of DES induced inflammatory and hypersensitivity reactions that delayed endothelization. A health alert followed3 that made the medical community recommend extended courses of dual antiplatelet therapy and put into question the convenience of DES. Beyond the increased rate of stent thrombosis, the first-generation of this type of stents had additional limitations: they were stainless-steel platforms with up to 140 µm thick struts, worse stent navigability, and fewer crossing capabilities. Also, the stent maximum expansion was limited (3.5 mm in the Cypher stent, Cordis Corp.), which occasionally prevented treating left main coronary artery lesions. With the passing of time, this stent technology has been refined to a point that there has been a major overhaul in its 3 main components: platform, polymer, and antiproliferative drug.

The changes made to the stent platform have been the development of more biocompatible alloys that have reduced strut thickness significantly and, consequently, improved stent navigability. Additionally, radial strength has been preserved to prevent recoil (table 1). Most of the stents commonly used today consist of cobalt-chromium or platinum-chromium alloys. The open-cell design has won the battle over the closed-cell design because it reduces the number of inter-strut links, the degree of jailed side-branch while improving stent navigability and conformability. Also, the new generation of DES have wider overexpansion limits (4.5 mm to 6 mm), which allows us to treat left main coronary artery lesions by adapting the stent area to the corresponding lunimal references without damage to the platform.

Table 1. Characteristics of drug-eluting stents

| Stent | Plataform | Polymer/ coating | Drug | Strut thickness (µm) | Maximum expansion (mm) | Studies with 1 month DAPT duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIENCE | Cobalt-chromium | Permanent/ circumferential | Everolimus | 81 | 2-3.25 → 3.75 3.5-4 → 5.5 |

Xience 28 USA (NCT03815175) |

| SYNERGY | Platinum-chromium | Bioresorbible/ abluminal | Everolimus | 74 | 2.25 → 3.5 3-3.5 → 4.25 4-5 → 5.75 |

SENIOR (NCT02099617) |

| Onyx | Nickel-platinum-chronium | Permanent/ circumferential | Zotarolimus | 81 | 2.5-3 → 3.75 3.5-4 → 4.75 4.5-5 → 5.75 |

Onyx ONE (NCT03344653) |

| Orsiro | Cobalt-chromium | Bioresorbible/ circumferential | Sirolimus | 60 | 2.5-3 → 3.5 3.5-4 → 4.5 |

Bioflow-DAPT (NCT04137510) |

| Ultimaster Tansei | Cobalt-chromium | Bioresorbible/ abluminal | Sirolimus | 80 | 2.25-3 → 4.5 3.5-4 → 5.5 |

Master DAPT (NCT03023020) |

| BioFreedom | Stainless-steel | Polymer-free/ abluminal | Umirolimus | 112 | 2.5-3 → 4.76 3.5-4 → 5.96 |

LEADERS FREE (NCT01623180) |

| Angiolite | Cobalt-chromium | Permanent/circumferential | Sirolimus | 75-85 | 2-2.5 → 4 2.75-3.5 → 5.25 4-4.5 → 6 |

– |

|

DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy. |

||||||

Polymers are the reservoir from which the drug is released in a controlled way towards the arterial wall. XIENCE (Abbott), and Resolute Onyx (Medtronic) stents include permanent polymers, but with improved biocompatibility. The XIENCE polymer is highly fluorinated, which minimizes adhesion and platelet activation increasing the safety profile. The Onyx stent uses Biolinx that consists of a mixture of polymers with hydrophilic capabilities that make it biocompatible and hydrophobic for a prolonged and uniform drug release. However, despite the good results reported with the new permanent polymers, some companies have decided to develop bioresorbable polymers (SYNERGY [Boston Scientific], Orsiro [Biotronik], Ultimaster Tansei [Terumo] stents, etc.). The use of a bioresorbable polymer-based coating facilitates degradation after the drug complete release just leaving 1 bare-metal stent behind 3-4 months after implantation, which prevents the remaining polymer from participating in the immune response associated with stent thrombosis. The biodegradable polymer-based SYNERGY stent has shown a rate of stent thrombosis of 0% at the 6-month follow-up, and a rate of target lesion revascularization similar to the one observed with the permanent polymer-based Promus Element stent (Boston Scientific).4 On the other hand, the biodegradable polymer-based Orsiro stent had a significantly lower rate of target lesion failure compared to the XIENCE stent with permanent polymer.5 However, the XIENCE stent group had more and longer stents implanted, both factors associated with adverse events at follow-up.

Polymer-free stents stand as an alternative to biodegradable polymer-based stents. The most representative of the former is the BioFreedom (Biosensors). It consists of a stainless-steel platform with micropores that store biolimus for a 1-month release of the drug. The lack of a polymer may potentially allow to shorten the duration of the period on dual antiplatelet therapy down to 1 month, like with bare metal stents. In the LEADERS FREE trial,6 the BioFreedom was compared to a bare metal stent in patients with high-risk of bleeding and a 1-month course of dual antiplatelet therapy. The outcomes proved that it was superior regarding the primary evaluation criteria for the safety and efficacy profile. Afterwards, almost every company has conducted or started safety and efficacy trials with 1-month courses of dual antiplatelet therapy (table 1).

Therefore, several advances have been made with new generation DES. The clinical impact associated with strut thickness reduction or the selection of bioresorbable polymer-based stents vs permanent or polymer-free stents is still under discussion. However, these improvements have had significant repercussions in the stent navigability, overexpansion capabilities, and selection of duration for dual antiplatelet therapy. However, these stent properties highly demanded by interventional cardiologists should always be based on a robust set of trials that confirm the efficacy and safety profile of each stent. Currently, the Angiolite stent (iVascular) is in this stage. It has recently joined the family of DES. This stent is an ultra-thin strut (75 µm to 85 µm) cobalt-chromium platform made from a biostable fluorinated polymer plus sirolimus as the antiproliferative drug. In the ANCHOR trial it showed an excellent degree of endothelization on the optical coherence tomography,7 with an 83% strut endothelial coverage at 3 months. Afterwards, the ANGIOLITE trial compared it to the standard DES and found a 0.04 mm late luminal loss vs the 0,08 mm of the XIENCE stent, as well as a low rate of events at the 2-year follow-up in both groups8 (target lesion failure, 7.1% with the Angiolite vs 7.6% with the XIENCE). In an article published on REC Interventional Cardiology, Pérez de Prado et al.9 presented a multicenter real-world registry of patients treated with the Angiolite stent. This registry could be considered the «moment of truth» for this stent. We should remember that the Absorb stent (Abbott) had excellent immediate results and at the 5-year follow-up10 in the early trials. However, it showed a high rate of stent thrombosis when used in real-world patients. The ANCHOR registry included 646 patients with a 2-year clinical follow-up. A total of 30% of these patients were diabetics. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction was the clinical presentation in almost 25% of these patients, and nearly 50% of them had multivessel disease. The rate of target vessel failure and the rate of stent thrombosis at the 2-year follow-up were 3.4%, and 0.9%, respectively. In this sense, the stent offers similar results to those obtained with state-of-the-art DES as the table of the supplementary data of the aforementioned article shows.9 However, these promising results will need to be confirmed at the 5-year follow-up. The behavior of the stent in the most complex lesions like bifurcations or chronic total occlusions associated with worse clinical outcomes—underrepresented in the registry—also needs to be assessed.

FUNDING

The authors received no funding whatsoever while preparing this manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. Suárez de Lezo has received fees from Terumo for his role as a consultor for Abbott and AstraZeneca, as well as for his presentations in training courses and seminars. P. Martín received fees from Cathmedical for his role as a consultor, as well as from Abbott and Boston Scientific for his presentations in training courses and seminars.

REFERENCES

1. Moses JW, Leon MB, Popma JJ, et al.;SIRIUS Investigators. Sirolimus-eluting stents versus standard stents in patients with stenosis in a native coronary artery. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1315-1323.

2. Stone GW, Ellis SG, Cox DA, et al.;TAXUS-IV Investigators. A polymer-based, paclitaxel-eluting stent in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:221-231.

3. Camenzind E, Steg PG, Wijns W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents:a cause for concern. Circulation. 2007;115:1440-1455.

4. Meredith IT, Verheye S, Dubois CL, et al. Primary endpoint results of the EVOLVE trial:a randomized evaluation of a novel bioabsorbable polymer-coated, everolimus-eluting coronary stent. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012:59:1362-1370.

5. Kandzari DE, Mauri L, Koolen JJ, et al. Ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stents versus thin, durable polymer everolimus-eluting stents in patients undergoing coronary revascularisation (BIOFLOW V):a randomised trial. Lancet. 2017;390:1843-1852.

6. Urban P, Meredith IT, Abizaid A, et al. Polymer-free drug-coated coronary stents in patients at high bleeding risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2038-2047.

7. Puri R, Otaegui I, Sabate M, et al. Three- and 6-month optical coherence tomographic surveillance following percutaneous coronary intervention with the Angiolite(R) drug-eluting stent:The ANCHOR study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:435-443.

8. Moreu J, Moreno-Gomez R, Perez de Prado A, et al. First-in-man randomised comparison of the Angiolite durable fluoroacrylate polymer-based sirolimus-eluting stentversus a durable fluoropolymer-based everolimus-eluting stentin patients with coronary artery disease:the ANGIOLITE trial. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:e1081-e1089.

9. Pérez de Prado A, Ocaranza-Sánchez R, Lozano Ruiz-Poveda F, et al. Real-world registry of the durable Angiolite fluoroacrylate polymer-based sirolimus-eluting stent:the EPIC02–RANGO study. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M21000223.

10. Onuma Y, Dudek D, Thuesen L, et al. Five-Year Clinical and Functional Multislice Computed Tomography Angiographic Results After Coronary Implantation of the Fully Resorbable Polymeric Everolimus-Eluting Scaffold in Patients With De Novo Coronary Artery Disease:The ABSORB Cohort A Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:999-1009.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become a widely used therapeutic strategy to treat symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Certain randomized clinical trials available have already described the prognostic benefit of this technique in elderly patients with high or very high surgical risk. Also, when implanted via transfemoral access, it has proven non-inferior or even superior compared to surgical aortic valve replacement in low- and intermediate-risk patients. Therefore, the current recommendations support its use in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis regardless of their surgical risk.1

However, since it is an age-related heart valve disease without an effective medical therapy yet, the prevalence of severe aortic stenosis has been growing parallel to life expectancy. As a matter of fact, this disease has huge repercussions in the patients’ survival rate and quality of life.2 Consequently, nonagenarian patients with severe aortic stenosis are a group in continuous expansion, and, to this date, the best way to treat them is still under discussion. Since most of these patients have traditionally been misrepresented in the clinical trials and there are registries with good results but a possible selection bias, the decision to treat these patients with TAVI is still challenging and is made on an individual basis after meticulous assessment of the patients by the heart team.

Data from the STS/ACC TVT registry on the results of 3773 patients ≥ 90 age provide us with relevant information on this clinical setting.3 Data show a higher mortality rate compared to younger patients at 30 days (8.8% vs 5.9%; P < .001) and 1 year (24.8% vs 22.0%; P < .001) mainly due to higher rates of in-hospital major bleeding (8.1% vs 6.8%; P < .001) and strokes (2.7% vs 2.1%; P = .021). Table 1 shows the data from the main international registries on nonagenarian patients treated with TAVI.

Table 1. Data of nonagenarian patients treated with TAVI from the main international registries

| Study, year | N (≥ 90 years) | Procedural success | Major bleeding | 30-day mortality rate | 1-year mortality rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SwissTAVI,4 2021 | 507 | N/A | 13% | 6.7% | 19.7% |

| Mentias et al.,5 2019 | 13 544 | N/A | 10% | 3.6% | 26.6% |

| Vlastra et al.,6 2019 | 882 | N/A | 8% | 9.9% | N/A |

| Doshi et al.,7 2018 | 1163 | N/A | 35% | 6.0% | N/A |

| Elgendy et al.,8 2018 | 5840 | N/A | 28% | 6.6% | N/A |

| McNeely et al.,9 2017 | 3531 | N/A | 34% | 8.4% | 25.4% |

| STS/ACC TVT,3 2016 | 3773 | N/A | 8% | 8.8% | 24.8% |

|

N/A, not available; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. |

|||||

In a study recently published on REC: Interventional Cardiology, Cepas-Guillén et al. describe the national experience with TAVI in nonagenarian patients with severe aortic stenosis between 2009 and 2018.10 The findings were compared to those from patients between 75 and 90 years who received the same treatment during the same period of time. A total of 8073 patients—387 nonagenarians and 7686 patients between 75 and 90 years—were included. The authors saw a higher in-hospital mortality rate in nonagenarian patients without significant differences at the 1-year follow-up (although with a tendency towards a higher mortality rate in patients ≥ 90 years). In the multivariate analysis, age was not significantly associated with a higher all-cause mortality rate, but the presence of comorbidities such as atrial fibrillation or worsening renal function. Also, a higher surgical risk was reported.10 The role of comorbidities in nonagenarian patients was analyzed by a former substudy that included 117 consecutive patients around 90 years old (median age, 91.1 years; 117 women) from the PEGASO (Prognosis of symptomatic severe aortic stenosis in octogenarians) and IDEAS (Influence of the severe aortic stenosis diagnosis) registries conducted in our country.11 A high comorbidity burden, characterized by scores ≥ 3 in the Charlson comorbidity index, present in a high number of patients, was associated with a high mortality rate at the 1-year follow-up.

Nonetheless, data from the SwissTAVI registry confirmed a tendency towards higher rates of mortality, stroke, and pacemaker implantation in the elderly group (< 70, 70-79, 80-89, and > 90 years) among the 7097 patients treated with TAVI between 2011 and 2018 (median age, 82 ± 6.4 years; 49.6% women) in Switzerland.4 It is interesting that older age was associated with a lower standard mortality rate compared to the general population of the same group without any differences reported among nonagenarian patients. Same as in the study conducted by Cepas-Guillén et al.,10 the mean comorbidity rate of nonagenarian patients included in this registry was lower compared to that of patients < 90 years, suggestive that it is a highly selected population, which is unequivocally associated with a better prognosis in the short- and long-term. Despite of this, in this series, vascular complications and major bleeding increased significantly among nonagenarian patients. In the metanalysis conducted by Sun et al.,12 the rate of major bleeding reported was similar above and below the 90-year mark with a relative risk of 1.17 (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.32). On the contrary, the rate of vascular complications went up > 90 years, especially when non-femoral access techniques were used. In the Spanish national series, transfemoral access was more frequently used in patients < 90 years. Although no random comparison of the access routes was conducted, most data support the idea that risks are higher when the non-femoral access is used.13 Also, these data recommend the use of this access in elderly patients whenever possible. Also, a tendency towards better results has been confirmed as heart teams have been gaining experienced in the management of this group of patients, both in the selection and implantation technique used as well as in further approaches with lower rates of complications and 30-day mortality > 50% at the 4-year follow-up.5 Noteworthy, it would be interesting to have more data on the treatment received by the patients, especially regarding antiplatelet therapy, given these patients’ higher risk of bleeding with the use of 2 different antiplatelet drugs, instead of 1,14 and a longer follow-up too.

Added to all this, we should recognise not only the presence of comorbidities, but also frailty, and other geriatric symptoms—prevalent all of them—that have a significant prognostic impact in elderly patients treated with TAVI.15 Different scales have been described, some of them very easy to implement and based on easy parameters like the presence of lower-limb frailty, cognitive impairment, anemia, and hypoalbuminemia, which allow us to predict mortality at the 1-year follow-up.16 The implementation of measures is essential to reverse frailty—if present—and prevent the appearance of delirium and other complications during admission since this improves the prognosis of patients significantly.

Finally, we wish to congratulate the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology Association for their remarkable work in this area—in continuous expansion and growth—since the experience and learning gained on this regard will contribute to improve the treatments that we will administer to our patients.

FUNDING

No funding whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al.;ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739-2791.

2. Osnabrugge RLJ, Mylotte D, Head SJ, et al. Aortic stenosis in the elderly:disease prevalence and number of candidates for transcatheter aortic valve replacement:a meta-analysis and modeling study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1002-1012.

3. Arsalan M, Szerlip M, Vemulapalli S, et al. Should transcatheter aortic valve replacement be performed in nonagenarians?:insights from the STS/ACC TVT registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1387-1395.

4. Attinger-Toller A, Ferrari E, Tueller D, et al. Age-Related Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:Insights From the SwissTAVI Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:952-960.

5. Mentias A, Saad M, Desai MY, et al. Temporal Trends and Clinical Outcomes of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Nonagenarians. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013685.

6. Vlastra W, Chandrasekhar J, Vendrik J, et al. Transfemoral TAVR in Nonagenarians:From the CENTER Collaboration. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:911-920.

7. Doshi R, Patel V, Shah P. Comparison of in-hospital outcomes between octogenarians and nonagenarians undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement:a propensity matched analysis. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2018;15:123-130.

8. Elgendy IY, Mahmoud AN, Elbadawi A, et al. In-hospital outcomes of transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement for nonagenarians. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:989-995.

9. McNeely C, Zajarias A, Robbs R, Markwell S, Vassileva CM. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Outcomes in Nonagenarians Stratified by Transfemoral and Transapical Approach. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:1808-1814.

10. Cepas-Guillén PL, Regueiro A, Sanmiguel Cervera D, et al. Outcomes of nonagenarians after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M21000220.

11. Bernal E, Ariza-SoléA, Formiga F, et al.;Influencia del Diagnóstico de Estenosis Aórtica Severa (IDEAS) Registry Investigators. Conservative management in very elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis:Time to change?J Cardiol. 2017;69:883-887.

12. Sun Y, Liu X, Chen Z, et al. Meta?analysis of predictors of early severe bleeding in patients who underwent transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120:655?661.

13. Drudi LM, Ades M, Asgar A, et al. Interaction between frailty and access site in older adults undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2185?2192.

14. Sanz-Sánchez J, Pivato CA, Leone PP, et al. Tratamiento antiagregante plaquetario único o doble tras implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Metanálisis de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECIC.M21000206.

15. Díez-Villanueva P, Arizá-SoléA, Vidán MT, et al. Recommendations of the Geriatric Cardiology Section of the Spanish Society of Cardiology for the Assessment of Frailty in Elderly Patients With Heart Disease. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:63-71.

16. Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in Older Adults Undergoing Aortic Valve Replacement:The FRAILTY-AVR Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:689-700.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is one of the leading causes of death worldwide. These rates are only likely to be buoyed in the future by the rising prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, the main cause of CAD, has been a topic of great interest.1 As a brief review, dyslipidemia plays a key role. Beginning with the incorporation of serum low-density lipoprotein into the endothelium tunica intima, chemokines and endothelial adhesion molecules attract macrophages into the arterial wall. Eventually, cholesterol droplets are incorporated into the macrophage cytosol, become oxidized, and form the so-called ‘foam cell’. In a reciprocal exchange, inflammatory mediators released by foam cells trigger ongoing endothelial damage, fibrosis, and intimal hyperplasia. Eventually, coronary artery stenosis occurs; a condition at the basis of CAD and for which inflammation is a key component.

Inflammation is likely to play a role in both stable and unstable CAD. Many patients may present small atheromas, but still suffer from acute coronary thromboses–the acute coronary syndrome. Pathological studies have shown that T-cells, macrophages, and mast cells congregate to plaque rupture sites where they upregulate matrix metalloproteases, degrade collagen, and weaken the fibrous cap that supports the plaques. Additionally, once the endothelium is exposed to the plaque following a rupture, these inflammatory cells facilitate thrombosis, and platelet plug formation. As clues to their damage, such patients show high levels of interleukin-6, and C-reactive protein in their blood.1

ANTI-INFLAMMATORY THERAPIES FOR CAD

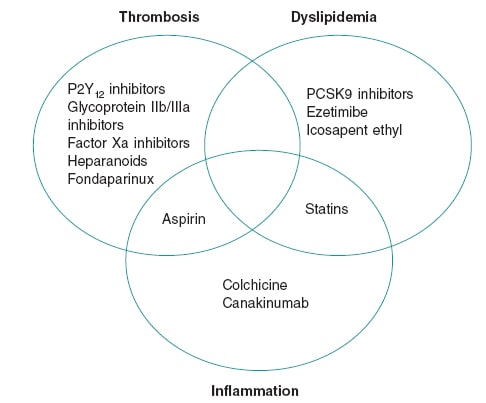

The centerpiece role of inflammation in CAD led to descriptions of atherosclerosis as a “chronic inflammation of the arteries,” a fact borne out by science as early as the 1980s.2 Yet, decades later no routinely used CAD therapies target any inflammatory pathways (figure 1). Many extant anti-inflammatory therapies have tried so but have proven unsuccessful. For instance, corticosteroids exhibit a broad range of anti-inflammatory properties, but their promotion of dyslipidemia and hypertension ultimately cause atherogenesis. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs other than aspirin inhibit prostacyclin, which increases vascular tone and platelet aggregation in the coronary arteries. Interest in methotrexate arose from observational studies that showed cardioprotective properties in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. However, a randomized clinical trial that analyzed its effect in patients with atherosclerosis showed that it does not lower the serum inflammatory markers or prevent myocardial infarction.3

Figure 1. Therapeutic foundations for the management of coronary artery disease. The figure shows agents with proven mortality benefits in the management of coronary artery disease. Although thrombosis, dyslipidemia, and inflammation are all key in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease, the scarcity of effective anti-inflammatory agents is evident.

An interleukin-1b inhibitor, canakinumab, was the first agent to successfully prevent cardiovascular events in patients with a recent myocardial infarction. In the CANTOS trial, canakinumab 150 mg once daily lowered the rates of nonfatal myocardial infarction, stroke, and death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.85; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.74-0.98) at the cost of increasing the rate of fatal sepsis, and infection (0.31 vs 0.18 per 100 person-years; P = .02). This trial was an important scientific breakthrough that showed that the inflammatory hypothesis is a therapeutic option for CAD. However, the costs of therapy and a modest effect size have both limited its use.4

Like methotrexate, interest in colchicine was borne out by observational data. In patients suffering gout flares, the use of colchicine was associated with fewer cardiovascular events compared to non-use.5 These observations led to a non-blinded randomized analysis of colchicine (the Low-dose colchicine for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease [LoDoCo] trial) that proved a reduction in cardiovascular events in patients with stable CAD.6 Although there were some methodological limitations, the trial served as the niche for more upcoming robust clinical data on colchicine.

Colchicine is an inhibitor of microtubules and may prevent leukocyte migration into sites of plaque formation and rupture. Moreover, colchicine helps inhibit the formation of the NLRP3 inflammasome –a structure recently involved in cytokine mediated cell death. These pro-inflammatory protein complexes are activated by cholesterol crystals in macrophages and secrete interleukin (IL)-1b, the cytokine target of canakinumab. Colchicine has also been shown to reduce C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6.7

A larger follow up trial to the initial LoDoCo trial, the LoDoCo2, enrolled 5522 patients with chronic CAD, and randomized them to receive colchicine or placebo for a median of 28.6 months after an open label run-in period to ensure colchicine tolerability. Colchicine was associated with a 31% reduction (HR, 0.69; 95%CI, 0.57-0.83; P < .001) of cardiovascular death, infarction, ischemic stroke, and revascularization. Adversely, patients who received colchicine showed higher rates of non-cardiovascular death, although the rate of events was low (HR, 1.51; 95%CI, 0.99-2.31; P = .06).8 Other adverse occurrences and intolerances were rare.

COLCHICINE IN ACS

Another 2 trials examined colchicine in a recent myocardial infarction setting: the COLCOT trial (efficacy and safety profile of low doses of colchicine after myocardial infarction), and the COPS trial (colchicine in patients with acute coronary syndrome). The first and larger of the two, the COLCOT trial, randomized 4745 patients who had a myocardial infarction within 30 days into colchicine therapy or placebo and followed them for a median of 22.6 months. The patients who received colchicine enjoyed a 23% reduction (HR, 0.77; 95%CI, 0.61-0.97; P = .02) in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, cardiac arrest, ischemic stroke, infarction, and angina requiring urgent revascularization. Though a positive outcome, it was driven primary by fewer revascularizations in the colchicine arm. Additionally, patients randomized to colchicine experienced more pneumonia (0.9% vs 0.4%; P = .03) compared to placebo.9 An early administration of colchicine was associated with greater benefits (within 3 days) in the COLCOT trial (HR, 0.52; 95%CI, 0.32-0.84 for initiation within 3 days vs HR, 0.98; 95%CI, 0.53-1.75 for initiation between days 4 and 7).10

The COPS trial enrolled 795 patients and randomized them to receive colchicine or placebo for 12 months. At the 1-year follow-up, no statistical differences were seen in the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, infarction, ischemic stroke, and cardiac arrest with colchicine compared to placebo (HR, 0.65; 95%CI, 0.38-1.09; P = .10), likely due to a lower rate of events from a shorter follow-up period, and a smaller sample size. Moreover, 8 patients from the colchicine arm and 1 from the placebo group died, an effect that reached statistical significance and was driven by non-cardiovascular mortality (P = .047).11 Although this trial enrolled relatively few patients, it reproduced a signal towards mortality as seen on the larger LoDoCo2 trial.

The largest trial of colchicine post-myocardial infarction, the Colchicine and spironolactone in acute MI (CLEAR SYNGERY, NCT03048825), is underway. It will randomize 7000 patients and help solve the issue of whether colchicine increases non-cardiovascular mortality. The findings of the COPS and LoDoCo2 trials may be spurious findings, similar to what was found in earlier statin trials, and eventually disproved. On the other hand, there could be an important impact of colchicine due to a reduction of host defenses that went previously unnoticed.

Colchicine may be the first widely available, inexpensive anti-inflammatory therapy for the management of CAD. However, the issue of non-cardiovascular mortality should be resolved before it is widely adopted.

FUNDING

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

S.S. Jolly reports grant support from Boston Scientific and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. W. Hijazi declared no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Bouabdallaoui N, Tardif JC, Waters DD, et al. Time-to-treatment initiation of colchicine and cardiovascular outcomes after myocardial infarction in the Colchicine Cardiovascular Outcomes Trial (COLCOT). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4092-4099.

2. Butt AK, Cave B, Maturana M, Towers WF, Khouzam RN. The Role of Colchicine in Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2021;46:100690.

3. Hansson GK. Inflammation, Atherosclerosis, and Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685-1695.

4. Nabel EG, Braunwald E., 2012. A Tale of Coronary Artery Disease and Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54-63.

5. Nidorf SM, Eikelboom JW, Budgeon CA, Thompson PL. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:404-410.

6. Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al.;LoDoCo2 Trial Investigators. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1838-1847.

7. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Pradhan A, et al.;CIRT Investigators. Low-Dose Methotrexate for the Prevention of Atherosclerotic Events. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:752-762.

8. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al.;CANTOS Trial Group Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1119-1131.

9. Solomon D, Liu CC, Kuo IH, Zak A, Kim SC. Effects of colchicine on risk of cardiovascular events and mortality among patients with gout:a cohort study using electronic medical records linked with Medicare claims. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1674-1679.

10. Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. 2019. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2497-2505.

11. Tong DC, Quinn S, Nasis A, et al. 2020. Colchicine in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation. 2020;142:1890-1900.

- Registry-based randomized clinical trials in cardiology: opportunities and challenges

- The coming convergence of intravascular imaging with computational processing and modeling

- Left atrial appendage occlusion: a decade of evidence

- In search of excellence in transcatheter and surgical aortic valve implantation

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

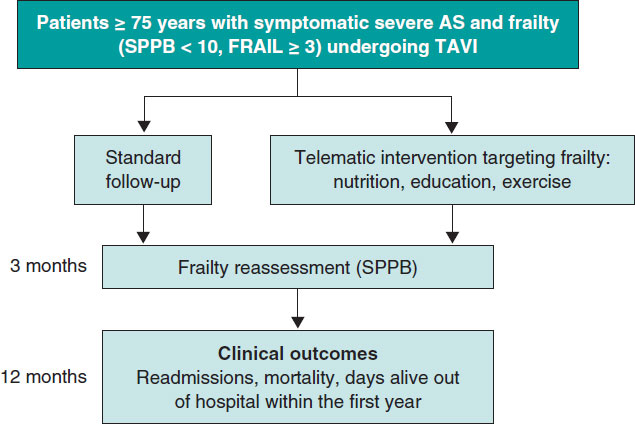

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España