Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Percutaneous coronary interventions with drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation have become a well-established treatment for obstructive coronary artery disease, improving long-term outcomes.1 However, despite recent improvements including thinner strut platforms and more biocompatible polymers, the Achilles’ heel of DES strategy remains the risk of DES-related adverse events such as in-stent restenosis or stent thrombosis in the short term,2 along with an increase in hard clinical events at a rate of 2.0 to 3.5% yearly after the first year.3,4

Drug-coated balloons (DCB) have been developed as an alternative to percutaneous coronary intervention with DES implantation in selected populations for the treatment of coronary artery disease. The main advantage of this technology is its ability to deliver an antiproliferative drug to the treated lesion without leaving any layer of metal, which might cause late adverse events. Another advantage is the potential reduction in the duration or discontinuation of dual antiplatelet therapy, especially in patients at high risk of bleeding.

Several studies have investigated the role of DCB in real-world patients, who are those mainly affected by in-stent restenosis or de novo small vessel disease.5-9 The only randomized study of DCB in de novo small vessels with a clinical primary endpoint was BASKET-SMALL-2. This study demonstrated the noninferiority of DCB vs DES (vessel size 2-3 mm), which was maintained up to 3 years follow-up in terms of all clinical endpoints.5

The initial fear of leaving behind a residual coronary dissection, especially in de novo lesions, could limit the widespread use of DCB. However, it has been shown that a nonflow-limiting dissection after DCB treatment tends to heal during the first few months, with both the paclitaxel and sirolimus technologies, without leading to acute or subacute vessel closure.10,11

The main message regarding DCB is that they should be used as the final step of percutaneous coronary intervention and only when a proper lesion preparation has been performed with a fully expanded balloon of the correct size for the vessel, with accurate management of calcifications and no residual stenosis greater than 30% that could impair drug delivery to the vessel and limit the potential of this technology.

Recently, a new generation of DCB eluting sirolimus (SCB, Magic Touch, Concept Medical, United States) has been introduced that uses nanoparticles composed of a dual layer of phospholipids encapsulating the antiproliferative agent. Histopathologic studies have demonstrated therapeutic concentrations of the drug within the vessel wall for up to 60 days after percutaneous coronary intervention.12

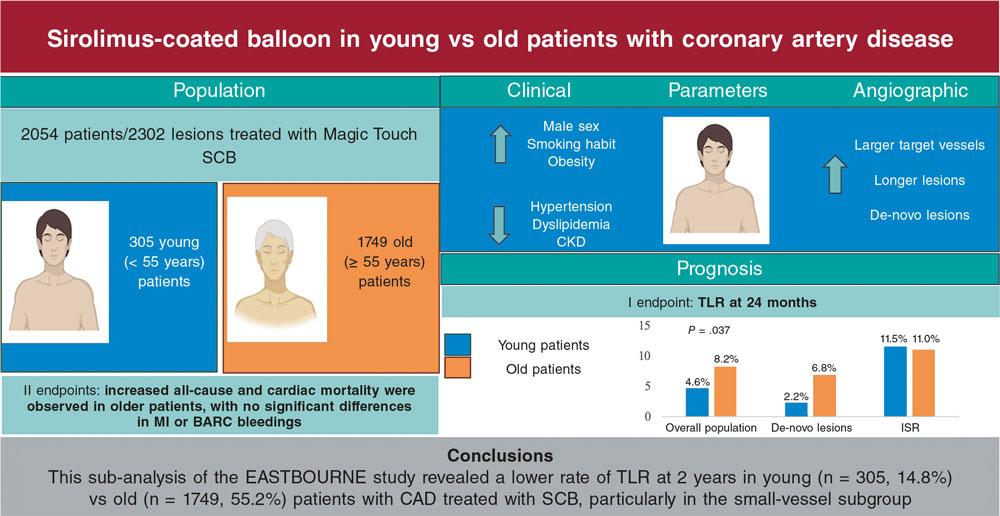

Notably, the angiographic performance of this class of drug seems to be inferior to that provided by paclitaxel. The recently published TRANSFORM I trial showed that SeQuent Please DCB (B. Braun, Germany) outperformed SCB in terms of angiographic parameters at 6 months of follow-up, but without showing any difference in clinical endpoints. This lower performance of SCB seems to occur particularly in cases of complex lesions, emphasizing the importance of adequate lesion preparation, especially with the less lipophilic drug sirolimus (figure 1).13 Somewhat reassuringly, the performance of SCB in terms of clinical endpoints has been demonstrated in all-comer populations, especially in the prospective EASTBOURNE study, which showed a good safety and efficacy profile up to 2 years of follow-up in 2123 patients/2440 lesions.14

Figure 1. Differences in terms of types of lesion and outcomes among 2 top enroller centers for the TRANSFORM II trial. PCB, paclitaxel-coated balloon; SCB, sirolimus-coated balloon.

The next step to ensure wider use of this new generation DCB will be direct comparison with DES, as in the TRANSFORM II (NCT04893291) trial. This is an international, multicenter, prospective, investigator-driven, open-label, randomized (1:1) clinical trial designed to test the efficacy of SCB vs DES in native coronary artery vessels with diameters between 2.0 and 3.5 mm. Inclusion and randomization are being performed after adequate lesion preparation in the absence of flow-limiting dissection and acute vessel recoil. The study population has been calculated expecting the noninferiority of SCB in terms of target lesion failure at 12 months, and its sequential superiority in terms of net-adverse clinical events, including BARC 3-5 bleeding events. Interestingly, patients will be followed up clinically for 5 years to observe the potential superiority of DCB in the long-term. This trial, which includes 7 Spanish centers, is including patients at 40 centers allocated in 11 countries in Europe, Asia, and South America.15 By November 20th, 2023, 600 patients out of the planned 1820 had been enrolled.

The TRANSFORM II trial will be an essential test of the maturity of DCB in such an established, prognostically significant arena, challenging DES as the gold standard for the treatment of patients with native coronary artery disease.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

B. Cortese serves on the advisory board or as a consultant for several companies producing or marketing DCB: Cordis, Medalliance, BBraun, Concept Medical, Medtronic, Innova HTS, and ANT.

REFERENCES

1. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

2. Sarno G, Lagerqvist B, Frobert O, et al. Lower risk of stent thrombosis and restenosis with unrestricted use of 'new-generation'drug-eluting stents:a report from the nationwide Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:606-613.

3. Kufner S, Ernst M, Cassese S, et al. 10-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Trial of Polymer-Free Versus Durable Polymer Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:146-158.

4. Brugaletta S, Gomez-Lara J, Ortega-Paz L, et al. 10-Year Follow-Up of Patients With Everolimus-Eluting Versus Bare-Metal Stents After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1165-1178.

5. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2):3-year follow-up of a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1504-1510.

6. Giacoppo D, Alfonso F, Xu B, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty vs. drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis:a comprehensive, collaborative, individual patient data meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials (DAEDALUS study). Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3715-3728.

7. Wanha W, Bil J, Januszek R, et al. Long-Term Outcomes Following Drug-Eluting Balloons Versus Thin-Strut Drug-Eluting Stents for Treatment of In-Stent Restenosis (DEB-Dragon-Registry). Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010868.

8. Cortese B, Di Palma G, Guimaraes MG, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small Coronary Vessel Disease:PICCOLETO II Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2840-2849.

9. Cortese B, Testa G, Rivero F, Erriquez A, Alfonso F. Long-Term Outcome of Drug-Coated Balloon vs Drug-Eluting Stent for Small Coronary Vessels:PICCOLETO-II 3-Year Follow-Up. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1054-1061.

10. Cortese B, Silva Orrego P, Agostoni P, et al. Effect of Drug-Coated Balloons in Native Coronary Artery Disease Left With a Dissection. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:2003-2009.

11. El Khoury A, Lazar L, Cortese B. The fate of coronary dissections left after sirolimus-coated balloon angioplasty:A prespecified subanalysis of the EASTBOURNE study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102:979-986.

12. Cortese B, Kalkat H, Bathia G, Basavarajaiah S. The evolution and revolution of drug coated balloons in coronary angioplasty:An up-to-date review of literature data. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102:1069-1077.

13. Ono M, Kawashima H, Hara H, et al. A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Trial to Assess the Effectiveness of the MagicTouch Sirolimus-Coated Balloon in Small Vessels:Rationale and Design of the TRANSFORM I Trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;25:29-35.

14. Cortese B, Testa L, Heang TM, et al. Sirolimus-Coated Balloon in an All-Comer Population of Coronary Artery Disease Patients:The EASTBOURNE Prospective Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1794-1803.

15. Greco A, Sciahbasi A, Abizaid A, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary artery disease:Rationale and design of the TRANSFORM II randomized clinical trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100:544-552.

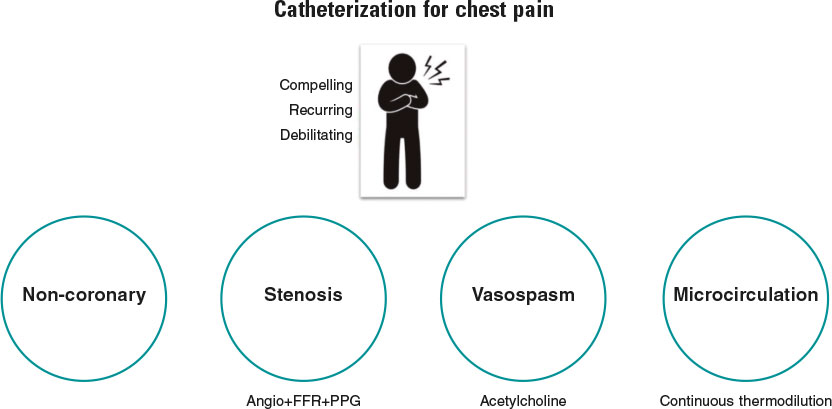

Simply stated, the goal of diagnostic coronary angiography is to distinguish the cause of a patient’s chest pain from 1 of 4 endotypes: a) epicardial stenosis; b) coronary spasm; c) coronary microvascular disease (CMD); and d) —equally important—noncoronary chest pain. Crucially, the latter is a diagnosis of exclusion and consequently cannot be confirmed without formal assessment of the other mechanisms (figure 1). Despite this truism, the interpretation of most coronary angiograms is limited to simple “eyeballing” of an epicardial “shadowgram”. This approach has a low diagnostic yield with 40% of patients found to have no significant epicardial stenoses—an entity known as angina with no obstructive coronary arteries (ANOCA).1 Despite the presence of typical angina or evidence of ischemia during noninvasive testing, these patients, are frequently nonchalantly dismissed without a formal diagnosis.

Figure 1. Patients with compelling, recurring, and debilitating chest pain should undergo catheterization with coronary angiography and—when needed—coronary function testing to unravel the mechanism of their pain. Noncoronary chest pain is a diagnosis of exclusion and consequently can only be confirmed if the 3 other mechanisms have been assessed. FFR, fractional flow reserve; PPG, pullback pressure gradient.

This very large group of patients is heterogeneous, and establishing the underlying cause of ANOCA requires a thorough coronary function testing (CFT) protocol that includes diagnostic angiography, provocation testing for microvascular or epicardial vasospasm, and assessment of CMD.2 In many centers, however, diagnostic angiography is rarely complemented with CFT. Among those that do, testing is often incomplete, with the result that patients often do not receive a diagnosis of the underlying cause of their ANOCA or benefit from potential endotype-specific treatments. Possible explanations for this behavior include a lack of familiarity with the causes of ANOCA, a lack of knowledge of available testing modalities, concerns about the accuracy of tests, and a belief that the underlying diseases are untreatable.

In a recent article published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Rinaldi et al.3 describe their single-center experience of the implementation of a specific ANOCA diagnostic and therapeutic protocol at Hospital Clínic in Barcelona, Spain. In this program, all patients with ANOCA underwent systematic CFT including bolus thermodilution for the calculation of coronary flow reserve and the index of microvascular resistance, as well as intracoronary provocation testing to assess epicardial or microvascular spasm. Based on the results of these tests, patients were classified into 4 endotypes: a) microvascular angina (MVA) (CMD or microvascular spasm); b) vasospastic angina (epicardial spasm); c) both MVA and vasospastic angina; and d) noncoronary chest pain.

The authors demonstrated that, as a result of the identification of specific ANOCA endotypes, there were significant increases in targeted medical prescriptions such as beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and long-acting nitrates. While this did not translate into a statistically significant improvement in quality of life between baseline and 3 months, angina significantly improved in terms of physical limitation, angina stability, and disease perception. Importantly, the protocol was shown to be safe, with only 3 minor adverse events being reported, all occurring during acetylcholine administration (transient bradycardia, paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with spontaneous cardioversion).

This work has significant strengths that should be highlighted. The CorMicA trial provided the first evidence from a randomized controlled trial of the benefits of systematic CFT with targeted medical therapy.4 However, to date, scarce real-world data have been available on the implementation of such protocols in routine clinical practice. As such, this small, real-world, observational study is strongly welcomed. More than the clinical results obtained in a relatively small number of patients, the work by Rinaldi et al.3 is particularly worthwhile for several methodological aspects, 3 of which are discussed below.

(i) Which patients should enter such a program and how? Patients were screened at a specific outpatient clinic and their inclusion was based on well-standardized criteria. Ideally, only patients with compelling, recurrent and invalidating symptoms should undergo CFT. The usefulness of such a program is significantly reduced by the referral of patients with unconvincing symptoms, or those with a high pretest probability of epicardial disease. Notably, the increasing role of coronary computed tomography angiography for the screening of epicardial disease in patients with angina currently allows diagnosis of ANOCA without the use of invasive diagnostic angiography and patients can thus be referred directly for CFT.

(ii) How should CFT be performed? As described by the authors, both microvascular function and coronary vasomotion should be investigated in a strictly standardized manner, preferably in the left anterior descending artery. However, the order of these tests is debatable. In our opinion, it does not make sense to investigate endothelial function and coronary vasomotion with a guidewire in the coronary artery or when the patient has already received vasoactive medications such as nitrates and calcium channel blockers. Consequently, we believe that acetylcholine testing should come first, with epicardial vasodilation being induced with nitrates at the end of acetylcholine testing. The latter also represents an important step (and good clinical practice) before commencing wire-based measurements of microcirculatory function. As for the choice of testing modality, bolus thermodilution should be replaced by continuous thermodilution as it enables the calculation of coronary flow reserve, absolute microvascular resistance (Rµ) and microvascular resistance reserve from absolute volumetric flow rather than from surrogates of flow.5 Future studies are expected to clarify the clinically relevant cutoff values for the indices derived from continuous thermodilution. These values should allow a more robust definition of CMD, which is currently an unmet need.

(iii) How should these patients be followed up? Patients should be followed up by the same physicians in a dedicated outpatient clinic, and be asked about their symptoms in a structured and systematic way. In this regard, the authors should be commended for the use of structured questionnaires to assess angina and quality of life. The classic Canadian Cardiovascular Society grading system for angina is not appropriate for ANOCA patients as their symptoms often differ from those reported by patients with epicardial disease. Moreover, objective signs of ischemia are often lacking. In the future, it is likely that patients will be given an app on their smartphone to closely monitor their symptoms.6

Overall, as with any new program, it is important to recognise that there is a learning phase. However, with a well-structured and standardized program, such as that proposed by Rinaldi et al.,3 this learning phase is likely to be short. There is now a need for future work addressing the implications of such a protocol on both time and cost in routine clinical practice. For example, in the setting of a busy, real-world catheterization laboratory, how much time, on average, does such a protocol add to the length of the procedure? Furthermore, what are the cost implications, and are they sufficiently counterbalanced by an increase in quality of life and/or symptom control?

To conclude, there are now strong clinical grounds for the systematic implementation of CFT in ANOCA patients. Furthermore, as demonstrated by Rinaldi et al., a standardized and robust testing program can be effectively implemented in real-world practice.3 Validation of clear diagnostic criteria for CMD is now needed for the results of CFT to be easily interpreted and acted upon. Patients and their referring clinicians deserve nothing less.

FUNDING

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this editorial.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

T. Mahendiran is supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). B. De Bruyne has a consulting relationship with Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, CathWorks, Siemens, and Coroventis Research; receives research grants from Abbott Vascular, Coroventis Research, Cathworks, Boston Scientific; and holds minor equities in Philips-Volcano, Siemens, GE Healthcare, Edwards Life Sciences, HeartFlow, Opsens, Sanofi, and Celyad.

REFERENCES

1. Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. Low Diagnostic Yield of Elective Coronary Angiography. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:886-895.

2. Jansen TPJ, Konst RE, Elias-Smale SE, et al. Assessing Microvascular Dysfunction in Angina With Unobstructed Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1471-1479.

3. Rinaldi R, Spione F, Verardi FM, et al. Angina or ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries:a specific diagnostic and therapeutic protocol. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M23000418.

4. Ford TJ, Stanley B, Good R, et al. Stratified Medical Therapy Using Invasive Coronary Function Testing in Angina:The CorMicA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2841-2855.

5. De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Gallinoro E, et al. Microvascular Resistance Reserve for Assessment of Coronary Microvascular Function:JACC Technology Corner. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:1541-1549.

6. Nowbar AN, Howard JP, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Daily angina documentation versus subsequent recall:development of a symptom smartphone app. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2022;3:276-283.

INTRODUCTION

Right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) disease is a common finding in children and adults with congenital heart disease and often occurs as a sequel of previous surgery. Over the past 2 decades, percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation has become more widely used and is recommended by current clinical practice guidelines1 as the preferred option for patients with previous conduits or bioprostheses.

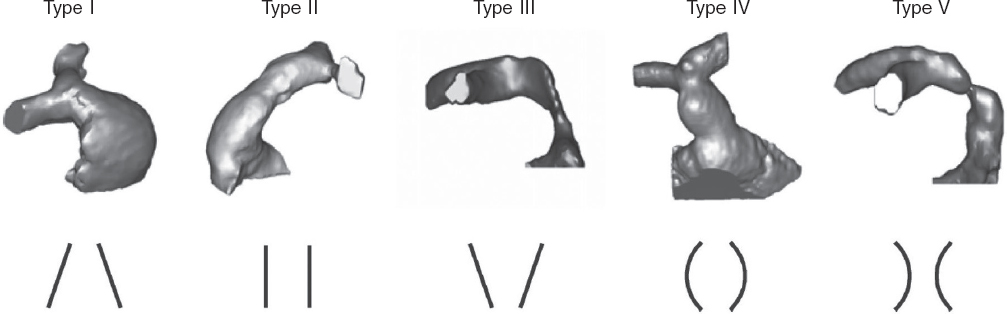

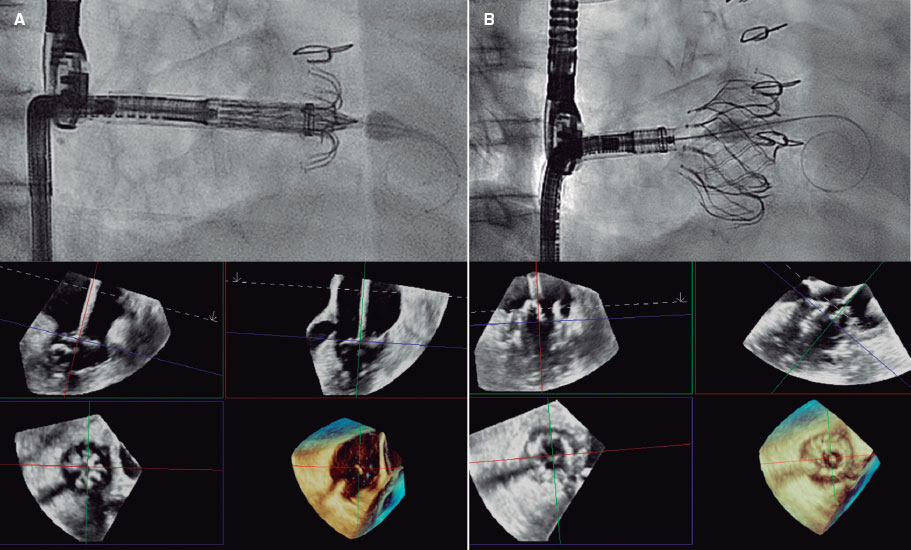

However, many patients have native or patched tracts (hereafter referred to as native RVOTs) with pulmonary regurgitation as the predominant lesion. In these patients, percutaneous valve placement is more complex due to the RVOT anatomy, its dynamic behavior, larger pulmonary annulus size, and lack of a proper landing zone for the valve. Because of the differences in underlying heart diseases, previous surgical repairs, and various pulmonary artery configurations, RVOT morphology varies widely but can be categorized into 5 subtypes2 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Five types of native RVOT anatomy: I - pyramidal; II - cylindrical or tubular; III - inverted pyramidal; IV - central enlargement; V - central narrowing. (Reproduced from Schievano et al.2 with permission from the author.)

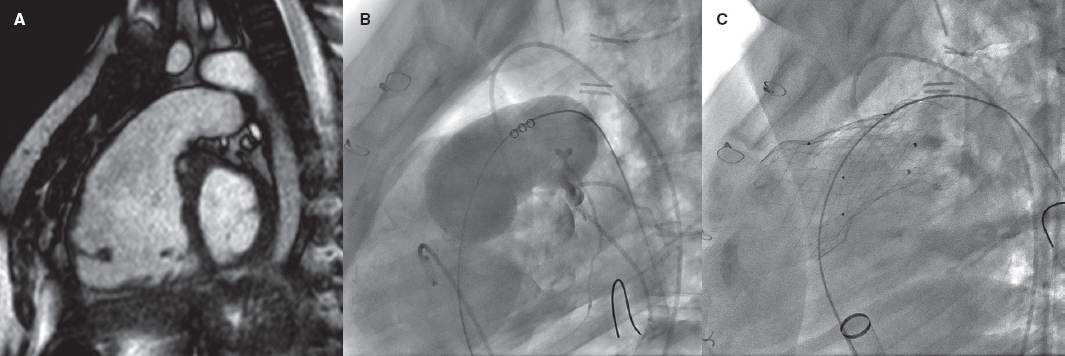

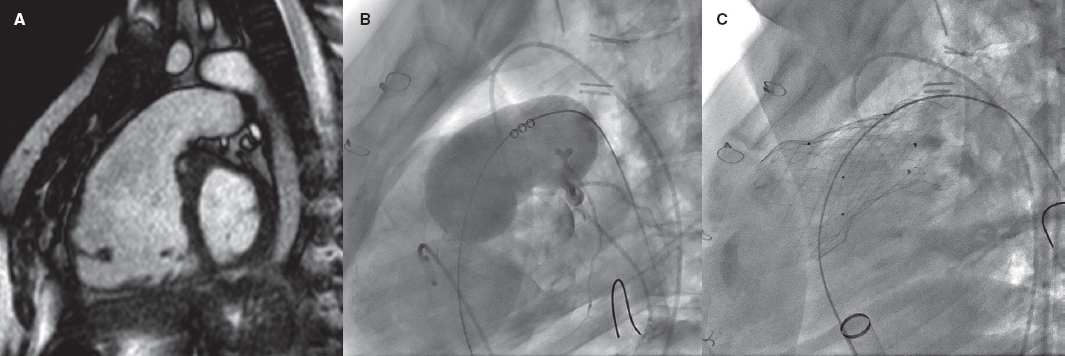

Repaired tetralogy of Fallot serves as the paradigm, and in these cases, surgery remains the standard of care. However, the development of percutaneous procedures has enabled a larger number of patients with these substrates to be eligible for percutaneous treatment (figure 2).

Figure 2. Self-expanding pulmonary valve implantation in an aneurysmal right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT). A: severely dilated RVOT on magnetic resonance imaging, with interventricular septal flattening. B: balloon sizing test in the RVOT with simultaneous injection into the left main coronary artery. C: successful venus-P valve (MedTech, China) implantation in the RVOT.

Two different models of balloon-expandable valves have been authorized to treat dysfunctional bioprostheses and conduits: the Melody (Medtronic, United States) and the SAPIEN valves (XT model, Edwards Lifesciences, United States). Although they have not yet been authorized for implantation in native RVOTs, both (along with the SAPIEN S3) have been used off-label in this setting.

To address the specific characteristics of native RVOTs, several models of self-expanding valves have been developed, such as the Venus-P (Venus MedTech, China, with CE marking for use in Europe since 2022), PULSTA (TaeWoong Medical, South Korea), and Harmony valves (Medtronic, United States, with prior FDA approval). The Alterra valve (Edwards Lifesciences) has also been used. This valve serves as a self-expanding prestent onto which a SAPIEN valve is later implanted.

The characteristics of each of these devices have already been described in detail in a previous issue of REC: Interventional Cardiology.3

RESULTS OF PERCUTANEOUS VALVES IN THE NATIVE RIGHT VENTRICULAR OUTFLOW TRACT

More information has gradually become available on the favorable results and durability of percutaneous valves. The largest multicenter registry to date,4 with 2476 patients (82% implanted with the Melody valve and 18% with the SAPIEN device, including 16% with native RVOTs), reported an 8-year survival rate of 91.1% after implantation, and a reintervention rate of 25.1%, which is similar to the rates reported in some surgical series.5 Nonrandomized comparative studies6 and a recent meta-analysis7 also found similar reintervention rates. Some series report higher rates in patients implanted with the Melody compared with the SAPIEN valve,8,9 although the 2 groups were not directly comparable, with reintervention-free survival rates in patients with SAPIEN being similar to those reported in patients with surgical valves.8

The SAPIEN device can be implanted with or without prestenting, depending on the patient’s characteristics, with good outcomes. The largest trial published to date included 774 patients implanted with the XT and S3 models10, 51% of whom had native RVOTs (table 1).

Table 1. Summary of some of the main trials of patients with native right ventricular outflow tract

| Author and year | Patients with native RVOT/Total patients | Valve type | Follow-up | Implant success | Other results | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Malekzadeh-Milani et al.23, 2014 | 34/34 | Melody | 2.6 years | 100% | Paravalvular leak in 2 patients during follow-up | 3 acute complications (9%): 1 hemoptysis, 1 RVOT obstruction, 1 stent embolization |

| Meadows et al.18, 2014 | 31/31 | Melody | 15 months (1 month- 3.8 years) | 100% | No mortality or valve regurgitation | Stent fractures (32%) associated with a higher rate of stenosis. 3 cases of endocarditis. Reintervention in 3 patients |

| Garay et al.13, 2017 | 10/10 | Venus P | 12 months (4 to 21) | 100% | Normally functioning valve, no stent fractures, right ventricular remodeling, and NYHA functional class improvement | None |

| Martin et al.11, 2018 | 132/132 | Melody | No follow-up | Complete cohort of 229 patients, but only 58% implanted. Good immediate hemodynamic outcomes | Complication rate of 4% (mostly due to stent migration) | |

| Morgan et al.24, 2019 | 41/57 | SAPIEN (S3, XT) | 5.3 months (1 to 26) | 100% | No prestenting. Normally functioning valve at follow-up. No mortality | 1 aortic compression, 2 tricuspid valve injury, 1 valve regurgitation |

| Shahanavaz et al.10, 2020 | 397/774 | SAPIEN S3 (78%) XT (22%) | 12 months (n = 349) | 97.4% | Normally functioning valve: 91.5% | Adverse events: 10%. Emergency surgery: 14 patients (1.8%). Tricuspid injury: 3% |

| Goldstein et al.19, 2020 | 143/530 | Melody (88%) SAPIEN (22%) | 1 year | 98% | Normally functioning valve: 98% | 1 death. Reintervention rate of 13.3% (mostly unrelated to the valve) |

| Lee et al.12, 2021 | 25/25 | PULSTA | 33 (± 14) months | 100% | Zero cases of valve dysfunction | No significant adverse events |

| Gillespie et al.16, 2021 | 21/21 | Harmony | 5 years | 100% | Implantation in all but 1 patient due to pulmonary hypertension. Normally functioning valve in nonreoperated patients | Valve explantation in 2 patients, 1 death 3 years after implantation, 2 reinterventions (valve-in-valve) |

| Morgan et al.25, 2021 | 38/38 | Venus | 27 months | 97.4% | Normally functioning valve at follow-up | Migration: 2 cases (surgery in 1) |

| Houeijeh et al.9, 2023 | 99/214 | SAPIEN XT/S3 (85%) Melody (15%) | 2.8 years (3 months-11.4 years) | Only cases with successful implantation included | Reintervention-free survival at 5 to 10 years: 78.1% to 50.4% (Melody) and 94.3% to 82.2% (SAPIEN) | Severe complications: 2.3%, 1 valve-related death. Endocarditis 5.5/100 patient-years (Melody) and 0.2/100 patient-years (SAPIEN) |

| Álvarez et al.14, 2023 | 8/8 | Venus | No follow-up | 100% | Normally functioning valve in all | No significant adverse events |

| Lin et al.15, 2023 | 53/53 | Venus (28%), PULSTA (72%) | 27.5 months | 98.1% | No valve regurgitation at 12 months | 1 embolization, 1 endocarditis |

|

NYHA, New York Heart Association; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract. In studies that are not specific to native RVOT, the results and complications refer to the overall cohort, as the results of native, or non-native RVOTs are often not detailed independently. Some centers participated in > 1 study, which allowed the same patient to be included in multiple publications. The most recent series with larger numbers of patients have been prioritized. |

||||||

In a study of patients with native RVOTs that included 229 candidates for the Melody valve, the device was finally implanted in 132 patients (58%).11 The most common reason for avoiding implantation was a prohibitively large RVOT, followed by coronary or aortic root compression. The immediate outcomes of patients with successful implantation were good. However, the low implantation rate demonstrates the limitation of treating native RVOTs with these valves.

Self-expanding valves fill this gap by allowing treatment of larger RVOTs, as they adapt to the anatomy of the RVOT and provide more stable attachment. The series published to date indicate a very high implantation success rate—close to 100%—with good short- and mid-term outcomes and few complications.12-16 (table 1 illustrates a selection of series representative of patients with native RVOTs).

Drawing comparisons between the results of surgical and percutaneous pulmonary valves is challenging because the types of patients and the anatomies treated are very different. Overall, patients undergoing percutaneous valve implantation are at higher risk and often have bioprostheses or small conduits that require smaller percutaneous valves, which is associated with a higher residual gradient, leading to a greater need for reintervention,4,8,9 and a higher rate of endocarditis. This aspect has traditionally led to less favorable results with the Melody series (with a maximum diameter of 22 mm), with durability being one of the issues initially identified, although more recent series have shown positive results. Only indirect comparisons can be drawn with valve procedures in the native RVOT.

PROCEDURAL PLANNING

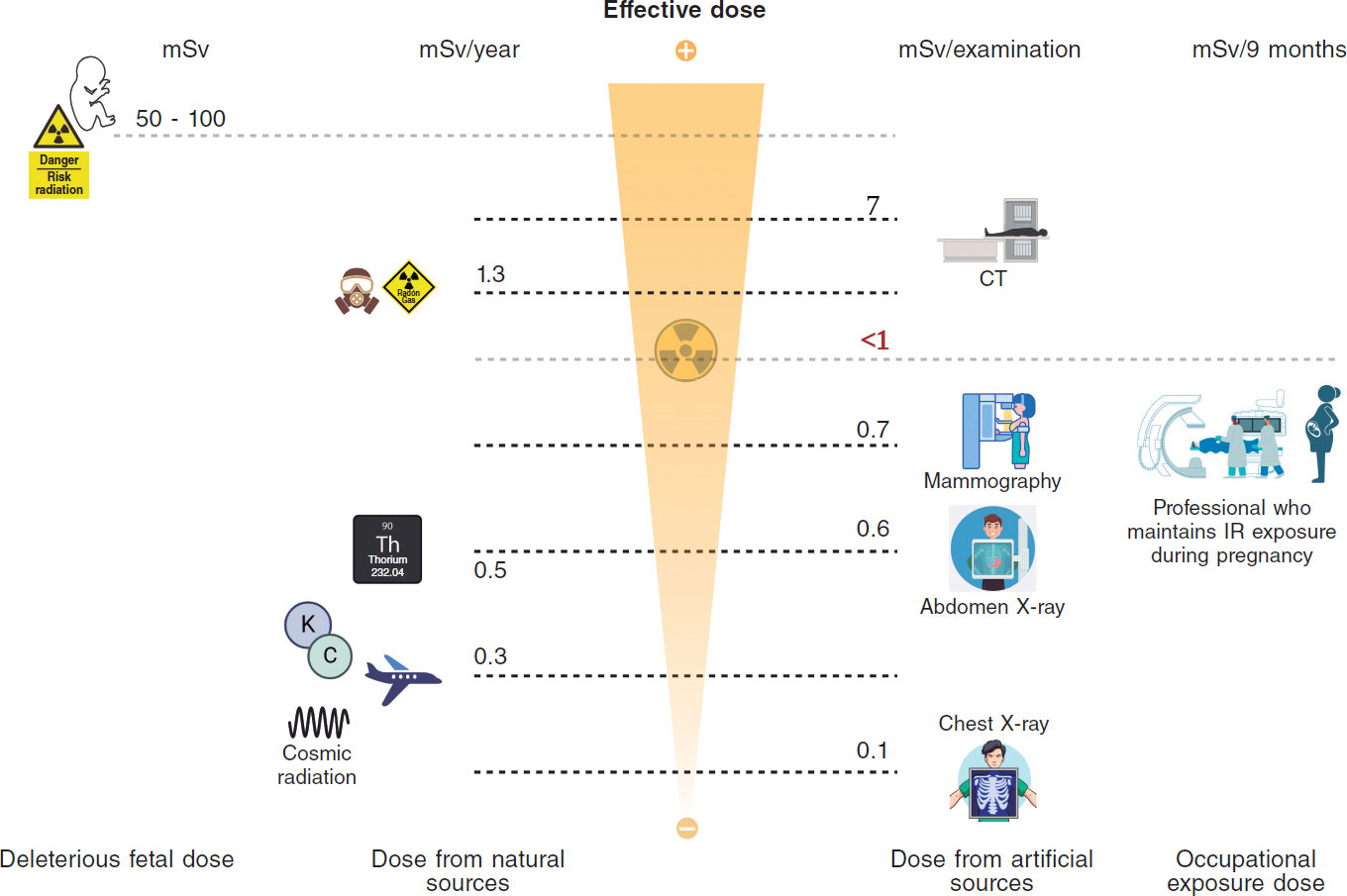

Multimodal imaging modalities, especially magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography, are crucial for patient selection and procedural planning. Key aspects include measurement of the RVOT and the pulmonary annulus, and assessment of both the RVOT and the coronary anatomy. Recently, computed tomography guidelines for RVOT assessment17 have been published with detailed information on the measurements that should be taken, and the cardiac cycle phase.

POTENTIAL PROBLEMS

Valve or stent migration or embolization is a potential complication in patients with large RVOTs due to the lack of an adequate landing zone, with incidence rates between 0% and 4.5%,11,10,18 and consequently proper valve sizing is of paramount importance.

Stent fractures can lead to loss of integrity and contribute to prosthetic valve dysfunction. Nonetheless, the implications of the occasional finding of an isolated strut fracture remain unclear.

Tricuspid valve injury has been reported in 3% to 6% of patients.10 However, this rate has dropped significantly with the use of DrySeal introducer sheaths (W.L. Gore & Associates, United States).10

Coronary compression is a rare complication nowadays, because coronary angiography is simultaneous and systematically performed during RVOT balloon inflation testing. However, it can be a reason for not performing percutaneous implantation in nearly 3% of patients.11

A higher incidence of infective endocarditis has been reported, especially after Melody valve implantation,6,8,9 with a higher risk when smaller valves are implanted and there is a greater residual gradient. The risk involved with other types of device such as the SAPIEN—whether because of its different composition (bovine jugular vein graft in the Melody compared with bovine pericardium in the SAPIEN) or because of its larger size—is much lower9 and seems comparable to that of surgical series.

Self-expanding valves are larger, and the proximal end often remains inside the RVOT, which could increase the risk of ventricular arrhythmias. The incidence of nonsustained ventricular tachycardia varies widely (between 0.6% and 40%11,19,20), although it is usually a transient phenomenon during the early postimplantation phase, and its long-term implications remain unclear. Of note, when comparing surgical with percutaneous pulmonary valve replacement, the early incidence of arrhythmias was lower in the latter.21 A potential caveat is that catheter access to the arrhythmic substrate can be limited after valve implantation.

The presence of the valve metal mesh with or without previous stents inside the RVOT can pose additional challenges for the surgeon if surgical valve replacement is subsequently required. This is a relative problem, because surgical pulmonary valve replacement also increases the risk of future reinterventions related to resternotomy.

BENEFITS OF PERCUTANEOUS VALVE IMPLANTATION

The possibility of performing percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation offers clear advantages: the procedure is much less invasive, length of stay is shorter,8 recovery is faster, the mortality rate is very low (from 0.2% to 0.8%),19 and the cost-effectiveness ratio is more favorable.22 In patients at high surgical risk, it might be the only available treatment option. The path followed by its “left-sided relatives”—transcatheter heart valves in the aortic position—illustrates that the threshold for the use of percutaneous techniques is decreasing as more experience is gained and technology becomes further refined. In cases of intermediate or low risk, percutaneous valve implantation may delay or avoid the need for surgery in patients who often require multiple interventions during their lifetime. This concept of avoiding sternotomies is relevant due to the added risk of further surgeries and for patients who are candidates for heart transplants. The decision on the best approach to valve implantation in each patient should be made by a multidisciplinary heart team, including health professionals experienced in these types of heart disease.

CONCLUSIONS

Percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation is particularly challenging in patients with native RVOTs. Nonetheless, it is a feasible option that is being used with a high success rate and few complications. However, appropriate candidate selection is essential. Several models of self-expanding valves have been specifically developed for this purpose, with good short- and mid-term results, allowing the treatment of patients with large RVOTs that were previously not amenable to balloon-expandable devices. The latest information suggests that the durability of percutaneous valves may be comparable to that of surgical bioprostheses, although long-term data are lacking, especially with the latest models. Although more studies and follow-up are necessary, percutaneous techniques are already an option for many patients and will likely become an alternative to surgical treatment in the near future.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Baumgartner H, De Baker J, Babu-Narayan S, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. The Task Force for the management of adult congenital heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563-645.

2. Schievano S, Coats L, Migliavacca F, et al. Variations in Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Morphology Following Repair of Congenital Heart Disease:Implications for Percutaneous Pulmonary Valve Implantation. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2007;9:687-695.

3. Gutiérrez-Larraya Aguado F, Pardeiro CA, Domingo EJB. Percutaneous treatment of pulmonary valve and arteries for the management of congenital heart disease. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:119-128.

4. McElhinney DB, Zhang Y, Levi DS, et al. Reintervention and Survival After Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:18-32.

5. Buber J, Egidy G, Huang A, et al. Durability of large diameter right ventricular out fl ow tract conduits in adults with congenital heart disease. Int J Cardiol. 2023;175:455-463.

6. Georgiev S, Ewert P, Eicken A, et al. Munich Comparative Study:Prospective Long-Term Outcome of the Transcatheter Melody Valve Versus Surgical Pulmonary Bioprosthesis with up to 12 Years of Follow-Up. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1-7.

7. Ribeiro JM, Gonc L, Costa M. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Pulmonary Valve Replacement:A Systemic Review. Ann Thorac Surg. 2020;110:1751-1761.

8. Hribernik I, Thomson J, Ho A, et al. Comparative analysis of surgical and percutaneous pulmonary valve implants over a 20-year period. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2022;61:572-579.

9. Houeijeh A, Batteux C, Karsenty C, et al. Long-term outcomes of transcatheter pulmonary valve implantation with melody and SAPIEN valves. Int J Cardiol. 2023;370:156-166.

10. Shahanavaz S, Zahn EM, Levi DS, et al. Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement With the SAPIEN Prosthesis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2847-2858.

11. Martin MH, Meadows J, McElhinney DB, et al. Safety and Feasibility of Melody Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement in the Native Right Ventricular Outflow Tract:A Multicenter Pediatric Heart Network Scholar Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1642-1650.

12. Lee S, Kim S, Kim Y. Mid-term outcomes of the Pulsta transcatheter pulmonary valve for the native right ventricular outflow tract. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:E724-E732.

13. Garay F, Pan X, Zhang YJ, Wang C, Springmuller D. Early experience with the Venus p-valve for percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation in native outflow tract. Netherlands Hear J. 2017;25:76-81.

14. Álvarez-Fuente M, Toledano M, Hernández I, et al. Initial experience with the new percutaneous pulmonary self-expandable Venus P-valve. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:263-269.

15. Lin MT, Chen CA, Chen SJ, et al. Self-Expanding Pulmonary Valves in 53 Patients With Native Repaired Right Ventricular Outflow Tracts. Can J Cardiol. 2023;39:997-1006.

16. Gillespie MJ, Bergersen L, Benson LN, Weng S, Cheatham JP. 5-Year Outcomes From the Harmony Native Outflow Tract Early Feasibility Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:816-817.

17. Han BK, Garcia S, Aboulhosn J, et al. Technical recommendations for computed tomography guidance of intervention in the right ventricular outflow tract:Native RVOT conduits and bioprosthetic valves:A white paper of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), Congenital Heart Surgeons'Society (CHSS), and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography &Interventions (SCAI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2023;18(2024):75-99.

18. Meadows JJ, Moore PM, Berman DP, et al. Congenital Heart Disease Use and Performance of the Melody Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve in Native and Postsurgical, Nonconduit Right Ventricular Outflow Tracts. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:374-380.

19. Goldstein BH, Bergersen L, Armstrong AK, et al. Adverse Events, Radiation Exposure, and Reinterventions Following Transcatheter Pulmonary Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:363-376.

20. Taylor A, Yang J, Dubin A, et al. Ventricular arrhythmias following transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement with the harmony TPV25 device. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100:766-773.

21. Wadia SK, Lluri G, Aboulhosn JA, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia burden after transcatheter versus surgical pulmonary valve replacement. Heart. 2018;104:1791-1796.

22. Vergales JE, Wanchek T, Novicoff W, Kron IL, Lim DS. Cost-Analysis of Percutaneous Pulmonary Valve Implantation Compared to Surgical Pulmonary Valve Replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;82:1147-1153.

23. Malekzadeh-Milani S, Ladouceur M, Cohen S, Iserin L, Boudjemline Y. Results of transcatheter pulmonary valvulation in native or patched right ventricular outflow tracts. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;107:592-598.

24. Morgan GJ, Sadeghi S, Salem MM, et al. SAPIEN valve for percutaneous transcatheter pulmonary valve replacement without “pre-stenting“:A multi-institutional experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:324-329.

25. Morgan G, Prachasilchai P, Promphan W, et al. Medium-term results of percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation using the Venus P-valve:international experience. EuroIntervention. 2019;14:1363-1370.

INTRODUCTION

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a well-established procedure for severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Previously, this procedure was used exclusively to treat inoperable and high-risk patients but is now a common approach for intermediate and low-risk populations. In parallel, there has been growing global experience in several off-label scenarios, as in bicuspid, valve-in-valve, and noncalcified aortic regurgitation (NCAR).1

AORTIC REGURGITATION

Due to abnormalities in the aortic leaflets or their supporting structures (ie, aortic root and annulus), or both, aortic regurgitation (AR) causes diastolic reflux of blood from the aorta into the left ventricle (LV). This leads to LV volume overload and dilatation, allowing the ejection of a larger stroke volume. However, over time, it results in a decline in systolic function causing symptoms conferring a poor prognosis.2 Current European and American guidelines recommend surgical intervention when significant AR is accompanied by symptoms, reduced LV ejection fraction, or severe LV dilatation.3-4 Although moderate or severe AR affects around 2.2% of the population aged 70 years or older, up to 30% of these individuals are deemed inoperable due to advanced age or comorbidities, with percutaneous options—including dedicated and nondedicated devices—gaining increased interest due to the absence of safe surgical alternatives.5

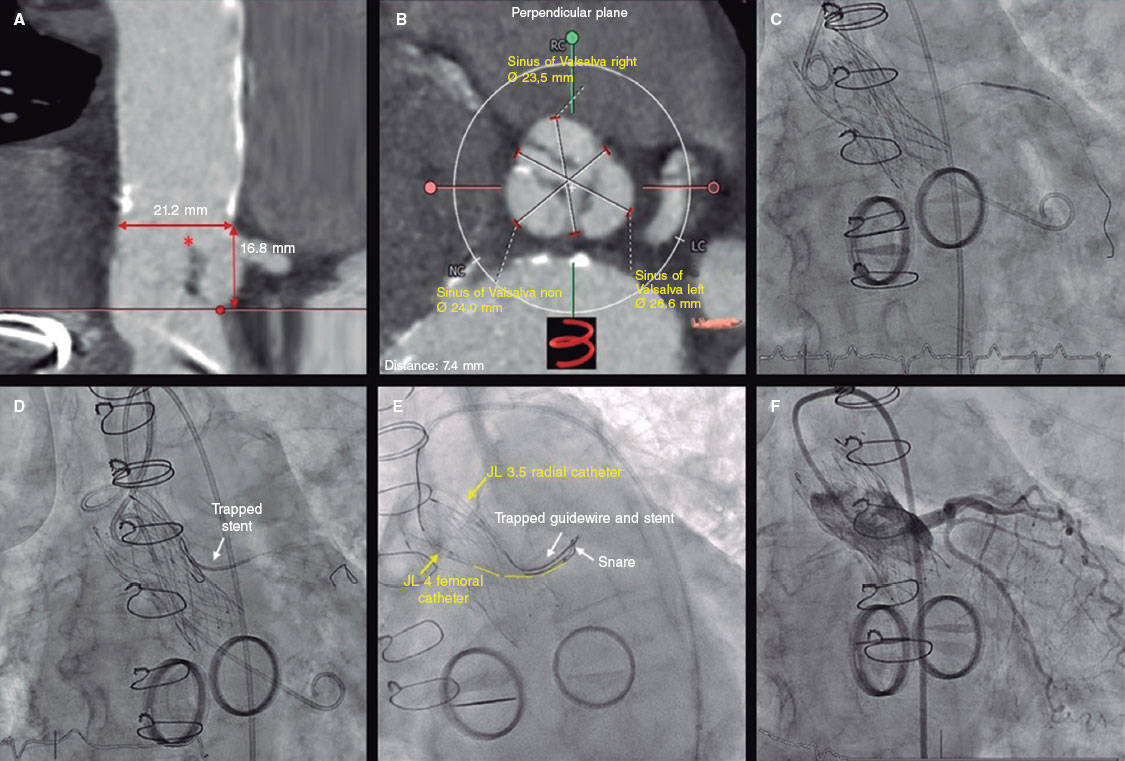

CHALLENGES OF TAVI IN NCAR

Specific challenges for transcatheter devices are due to the characteristics of patients with NCAR, including larger aortic annular dimensions, aortic root dilatation, insufficient annular calcification for anchoring, and larger stroke volume with backflow to the LV causing a “suction effect”. All of these factors create difficulties in selecting the appropriate device and positioning and deploying it correctly, and consequently increase the risk of embolization or malpositioning of the prosthesis, requiring a second valve implantation. Ultimately, these challenges are associated with increased mortality. In particular, the primary concern is valve embolization. To reduce the risk of this complication, prosthesis oversizing is routinely performed, but the exact degree of oversizing with each device has not been standardized. Furthermore, oversizing is associated with a high rate of conduction system disturbances and may carry a higher risk of annular rupture.

DEVICES AND EVIDENCE

There are 2 dedicated-devices for NCAR: The Trilogy system (JenaValve Technology Inc, California, United States) and the J-Valve (JC Medical Inc, California, United States). The most recent experience with these dedicated devices has been reported by Adam et al.6 and García et al.7 The Trilogy system was associated with a 30-day mortality rate of 1.7% (vs 3.7% with J-Valve) and both had 0% ≥ moderate residual AR. However, 7.4% required conversion to surgery with the J-Valve, leading to some technical changes in the technology. Of note, the pacemaker rate with both systems was above 10% (19.6% and 13%, respectively). These promising dedicated technologies still have certain shortcomings, the main one being the lack of sizes covering large annuli; indeed, for 10% oversizing, the proportion of AR patients whose aortic structures were above the recommended indications was up to ~50%.8

The first-in-human compassionate use of SAPIEN (Edwards Lifesciences, California, United States) was reported in 2012,9 followed by multiple case series and registries reporting the feasibility of TAVI in NCAR with new-generation nondedicated devices. The most recent summary of the experience was reported in a meta-analysis by Takagi et al.,10 and the pooled analysis at 30 days demonstrated 80.4% device success, 9.5% all-cause mortality, 7.4% ≥ moderate residual AR, and a pacemaker rate of 11.6%. Although these results were promising and significantly better than with early-generation devices in all aspects, there was still a substantial gap to achieve similar outcomes to TAVI in aortic stenosis and, indeed, the rate of valve embolization was high (above 9% with all the technologies, even the dedicated technologies).10

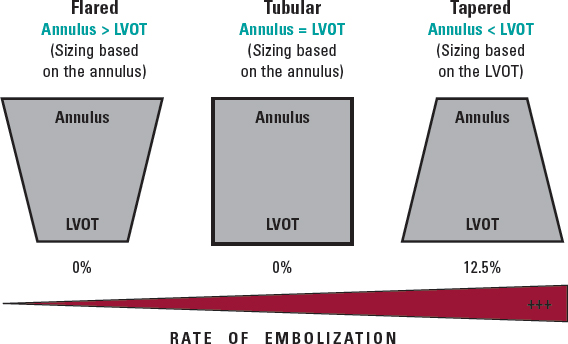

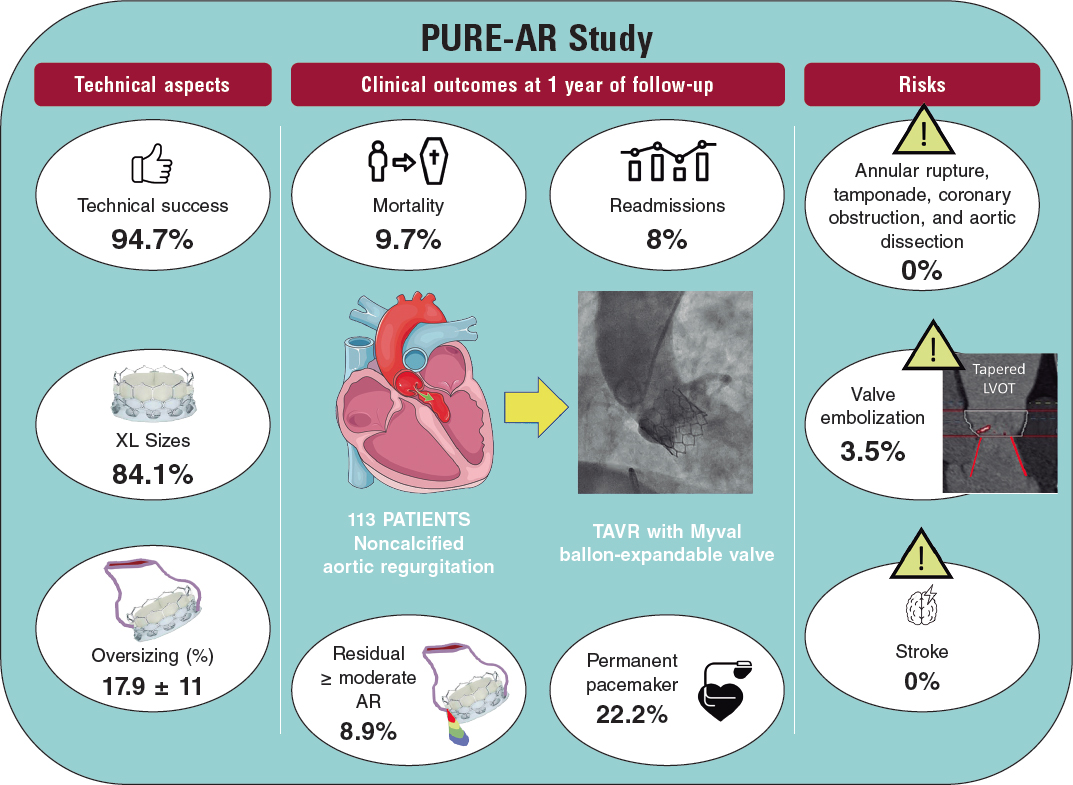

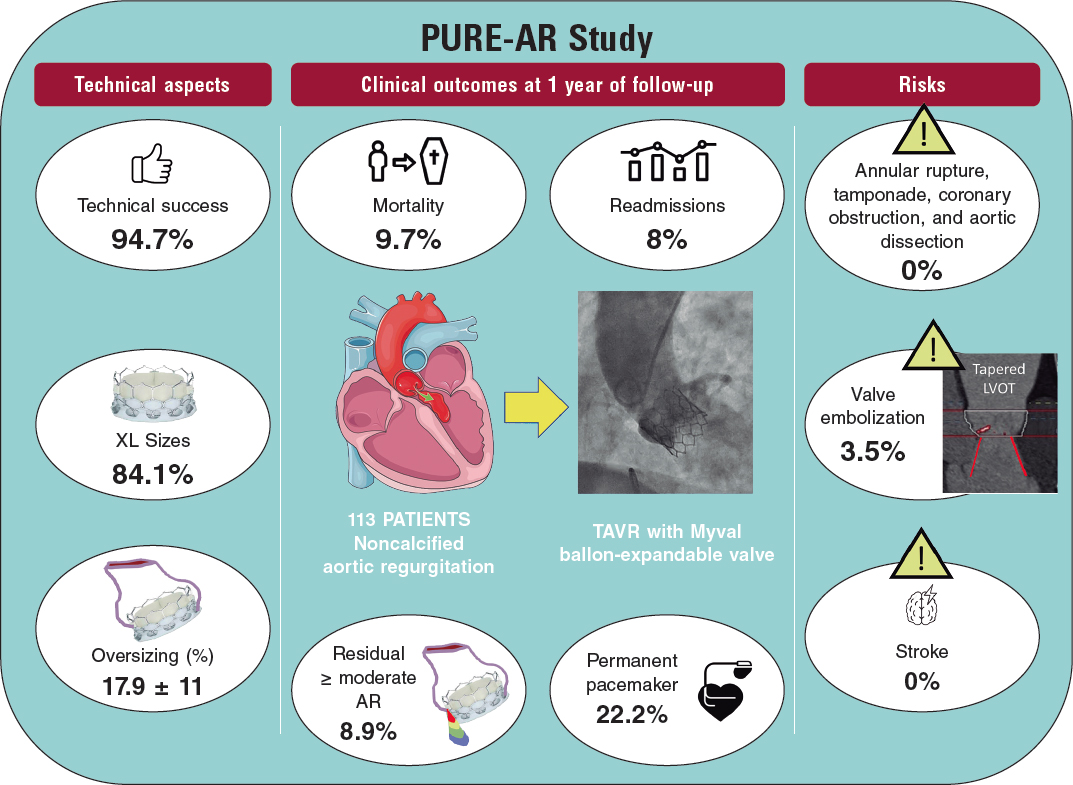

More recently, the new Myval balloon-expandable valve (Meril Lifesciences Ltd, Vapi, India) has demonstrated better outcomes than those reported by Takagi et al. likely due to the availability of extra-large sizes (30.5 and 32 mm), allowing a greater degree of oversizing and covering annuli up to 100.5 mm perimeter and 840 mm2 area at its nominal volume, increasing the proportion of inoperable patients who can be treated percutaneously. Because of the high procedural success rate (94.7%), and the absence of severe anatomical complications (ie, annular rupture, aortic dissection, or coronary obstruction), the Myval balloon-expandable valve is a promising new approach to this condition until dedicated devices for these annular sizes become available. Nevertheless, prosthesis embolization occurs in 3.5% of patients, leaving room for improvement; according to this research, the interplay of the aortic annulus and the LV outflow tract could help to predict the risk of valve embolization, suggesting that, in borderline annular sizes, when 20% oversizing cannot be achieved and adverse (tapered) morphology is detected, the intervention should be avoided or might be carried out under mechanical circulatory support (figure 1).11

Figure 1. Anatomical predictor of valve embolization during transcatheter aortic valve implantation for noncalcified aortic regurgitation. LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract.

Poletti et al.12 recently compared latest-iteration nondedicated devices and suggested that Myval might provide the best outcomes compared with other devices; indeed, the subanalysis (not published yet) comparing the 2 balloon-expandable platforms suggested that, despite being used in patients with significantly smaller aortic annuli, SAPIEN-3 had a lower device success rate (72% vs 90%) and a higher rate of prosthesis migration/embolization (SAPIEN 17% vs MyVal 5%).12 A summary of the PURE-AR study11 with the Myval device is shown in figure 2. The current evidence on different devices is summarized in table 1.

Figure 2. Main outcomes reported in the Myval registry for treatment of noncalcified aortic annuli with large annuli. AR, aortic regurgitation; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; TAVR, transcatheter aortic valve regurgitation.

Table 1. Comparison of outcomes between the international registries

| Registry | No. of patients | Type of device | Device success | All-cause mortality | ≥ Moderate residual aortic regurgitation | Permanent pacemaker implantation rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoon et al.13 (2017) | 331 patients with NCAR and FSHV | Nondedicated devices | Overall: 74.3% | Overall: 10.9% | Overall: 9.6% | Overall: 18.2% |

| Early-generation devices (CoreValve, SAPIEN XT) | Early-generation devices: 61.3% | Early-generation devices: 13.4% | Early-generation devices: 18.8% | Early-generation devices: 17.5% | ||

| New-generation devices (Evolut R, JenaValve, Engager, Portico, ACURATE, Lotus, Direct Flow, SAPIEN 3) | New-generation devices: 81.1% | New-generation devices: 9.4% | New-generation devices: 4.2% | New-generation devices: 18.6% | ||

| De Backer et al.14 (2018) | 254 patients with NCAR | Nondedicated devices Early-generation devices (CoreValve, SAPIEN XT) | Early-generation devices: 47% | Early-generation devices: 17% | Early-generation THV’s: 26% | Not reported |

| New-generation devices (Evolut R, JenaValve, Engager, Portico, ACURATE, Lotus, Direct Flow, SAPIEN 3) | Newer-generation devices: 82% | Newer-generation devices: 8% | Newer-generation THV’s: 5% | |||

| Sawaya et al.15 (2018) | 146 patients with NCAR and failing surgical heart valves (FSHV) | Early-generation devices (CoreValve SAPIEN XT) | NCAR: 72% | NCAR: 13% | NCAR: 13% | NCAR: 18% |

| New-generation devices (Evolut R, JenaValve, Lotus, Direct Flow, SAPIEN 3) | FSHV: 71% | FSHV: 6% | FSHV: 6% | FSHV: 5% | ||

| Early-generation devices: 54% | Early-generation devices: 22% | Early-generation devices: 27% | ||||

| New-generation devices: 85% | New-generation devices: 8% | New-generation devices: 3% | ||||

| Sánchez-Luna et al.11 2023 | 113 patients with NCAR | New-generation nondedicated device: Myval | 94.7% | 9.7% | 8.9% | 22.2% |

| Poletti et al.12 2023 | 201 patients with NCAR | New-generation devices: SEV (Evolut R/Pro, ACURATE Neo/Neo2, Jena Valve, Navitor/Portico) | Overall: 76.1% | Overall: 5% | Overall: 9.5% | Overall: 22.3% |

| SEV: 75.8% | SEV: 5.3% | SEV: 9.2% | SEV: 22.6% | |||

| BEV (SAPIEN, Myval) | BEV: 76.8% | BEV: 4.4% | BEV: 10.1% | BEV: 21.8% | ||

| Adam et al.6 (2023) | 58 patients with NCAR | Dedicated device: Trilogy system (JenaValve) | 98% | 1.7% | 0% | 19.6% |

| Garcia S et al.7 (2023) | 27 patients with NCAR | Dedicated device: J-Valve | 81% | 3.7% | 0% | 13% |

|

BEB, balloon-expandable valve; FSHV, failing surgical heart valve; NCAR, noncalcified aortic regurgitation; SEV, self-expandable valve; THV, transcatheter heart valve. Medtronic, United States: CoreValve, Engager, and Evolut R. Edwards Lifesciences, United States: SAPIEN XT, SAPIEN 3. Abbott Vascular, United States: Navitor/Portico. Meril Life, India: Myval. Boston Scientific, United States: ACURATE Neo/Neo2, Lotus. Trilogy, Germany: JenaValve. Direct Flow Medical, United States: Direct Flow. JC Medical, United States: J-Valve. |

||||||

In conclusion, although the surgical approach remains the standard-of-care in NCAR patients, the outcomes of new-generation dedicated and nondedicated TAVI devices are rapidly improving. The main caveats include the lack of large-sized dedicated devices and the risk of valve embolization with nondedicated devices, although this risk can be minimized by extra-large sizes and morphological analysis of the LV outflow tract. The rate of conduction disturbances is still higher than for TAVI in aortic stenosis and its decrease will require specific technology and strategies, given its potentially negative impact in LV remodelling. Clinical trials comparing surgery and TAVI in this setting for high-risk patients are an urgent need.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

I.J. Amat-Santos and J.P. Sánchez-Luna equally contributed in the design, data gathering, analysis, and final approval of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

I.J. Amat-Santos is proctor for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and Meril Life. There are no other potential conflicts of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

1. Santos-Martínez S, Amat-Santos IJ. New Challenging Scenarios in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: Valve-in-valve, Bicuspid and Native Aortic Regurgitation. Eur Cardiol. 2021;16:e29.

2. Maurer G. Aortic regurgitation. Heart. 2006;92:994-1000.

3. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. EuroIntervention. 2022;17:e1126-e1196.

4. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e35-e71.

5. Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, et al. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:897-902.

6. Adam M, Tamm AR, Wienemann H, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Isolated Aortic Regurgitation Using a New Self-Expanding TAVR System. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1965-1973.

7. Garcia S, Ye J, Webb J, et al. Transcatheter treatment of native aortic valve regurgitation: The North American Experience with a Novel Device. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1953-1960.

8. Chen Y, Zhao J, Liu Q, et al. Computed tomography anatomical characteristics based on transcatheter aortic valve replacement in aortic regurgitation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2023;39:2063–2071.

9. D'Ancona G, Pasic M, Buz, S, et al. TAVI for pure aortic valve insufficiency in a patient with a left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:e89-e91.

10. Takagi H, Hari Y, Kawai N, et al. Meta-analysis and meta-regression of transcatheter aortic valve implantation for pure native aortic regurgitation. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:729-741.

11. Sánchez-Luna JP, Martin P, Dager AE, et al. Clinical outcomes of TAVI with the Myval balloon-expandable valve for non-calcified aortic regurgitation. EuroIntervention. 2023;19:580-588.

12. Poletti E, De Backer O, Scotti A, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Pure Native Aortic Valve Regurgitation: The PANTHEON International Project. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1974-1985

13. Yoon SH, Schmidt T, Bleiziffer S, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Pure Native Aortic Valve Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2752-2763.

14. De Backer O, Pilgrim T, Simonato M, et al. Usefulness of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation for Treatment of Pure Native Aortic Valve Regurgitation. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122:1028-1035.

15. Sawaya FJ, Deutsch MA, Seiffert M, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in the Treatment of Pure Aortic Regurgitation in Native Valves and Failing Surgical Bioprostheses: Results From an International Registry Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1048-1056.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is an established treatment for elderly patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Currently, most procedures are performed through transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TF-TAVI) under conscious sedation via vascular access with safe and effective closure.1 Nonetheless, large-bore transcatheter arterial accesses are inherently associated with a higher risk of vascular and hemorrhagic complications.2

The use of vascular closure devices (VCDs) in endovascular procedures has grown exponentially. Their emergence has reduced time to hemostasis, facilitated early ambulation and discharge, and reduced hospitalization costs.2-4

However, failed VCDs are not an uncommon finding (1%-8%), and vascular and hemorrhagic complications—most commonly found at the access site—can sometimes determine procedural success or failure.5,6 Vascular complications significantly contribute to clinical outcomes in the short- and long-term, including length of stay, rehospitalizations, need for blood transfusions, and all-cause mortality.2,4 Therefore, successful arterial access and closure is critical in TAVI.2,7,8

CURRENT DEVICES

The most widely used VCDs for large-bore arteriotomy closure are the suture-mediated closure system, Perclose ProGlide system (Abbott Vascular, United States), and the most recent plug-based MANTA vascular closure device (Teleflex/Essential Medical, United States).

The failure mechanisms associated with the Perclose ProGlide device include suture-related malfunction, unsuccessful deployment, and incomplete vessel wall apposition. Potential errors associated with the MANTA device include failed deployment, intraluminal or subcutaneous deployment, collagen detachment, delivery handle-related arterial occlusion, and incomplete handle apposition.5,6,8

The first feasibility studies ever conducted on the MANTA device showed promising safety and efficacy. Afterwards, several registries have presented their findings that compare favorably with suture techniques.8-11

Two recent randomized clinical trials have compared the 2 techniques. The MASH trial included 210 patients and found no differences in its primary endpoint: puncture site-related major and minor complications (10% with the MANTA vs 4% with the ProGlide; P = .16).6 In contrast, in the CHOICE-CLOSURE trial of 516 patients, the MANTA device was associated with a higher rate of puncture site-related major and minor vascular complications (19.4% vs 12% with ProGlide; P = .029), and a similar incidence of puncture-site bleeding (11.6% vs 7.4%; P = .133).12

In an article published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Martinho et al.13 present an interesting single-center observational study on the largest real-world experience with the MANTA device. The aim of the study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of the device in a consecutive unselected cohort of patients referred for TF-TAVI. The registry included 245 patients from March 2020 through February 2022. The participants’ median age was 81 years, 52.7% were women, and the median EuroSCORE II was 3.15%. The 30-day TF-TAVI puncture site-related vascular complications were studied according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium (VARC) criteria. Regarding the primary outcome measure of the study—efficacy according to the VARC-3 criteria—successful puncture-site closure was achieved in 92.2% of participants. There were no major vascular or hemorrhagic complications, and only 8.6% experienced minor vascular complications according to the VARC-3 criteria (secondary safety outcome measure). The main predictors of device failure were a minimum femoral artery diameter and, consequently, a higher sheath-to-femoral artery diameter ratio, and the presence of more tortuous and calcified arterial accesses.13

Compared with the most recent clinical trials, the study by Martinho et al.13 found rates of device failure that were lower than those in the MASH trial (7.8% vs 20%), but higher than those reported by the CHOICE-CLOSURE trial (4.7%). According to the authors, some of these differences may be attributed to the varying and inconsistent definitions of device failure across the studies.6,12

According to researchers, the study limitations include its single-center retrospective design, the absence of comparisons with other closure devices, and the lack of postoperative ultrasound scans for some of the participants (which were mandatory in the CHOICE-CLOSURE trial, potentially contributing to a higher detection rate of access site-related complications).12 We should also mention that the registry included only patients considered eligible for closure with the MANTA device and excluded those with “unsuitable” anatomies.

To date, the available information, which includes numerous observational studies, 2 current randomized controlled trials, and more than 1 meta-analysis, suggests that vascular and hemorrhagic complications associated with collagen-based VCDs are quite similar to those of suture-based devices. No significant differences in the VCD failure rate have been reported, with identical 30-day all-cause mortality rates in the 2 groups.

CONCLUSIONS

The gradual reduction in the rate of vascular complications is the result of better preoperative assessment and technological support. Meticulous preoperative planning, with multidetector computed tomography for iliofemoral arterial axis study and ultrasound-guided access, should allow for an optimal approach to the access site and avoidance of incorrect cannulations.

Undoubtedly, cannulation of severely calcified arteries is associated with worse outcomes because of the difficulty involved in attaching the suture systems, and the higher risk of poor plug device apposition. Conversely, puncture sites without wall calcification should consistently yield better results, regardless of the type of VCD used.

Finally, regardless of the system used, angiographic or ultrasound confirmation after closure is always necessary to identify undetected VCD failures, vascular occlusions, or subcutaneous deployments, and expedite the implementation of corrective measures.5,13

In the search for the ideal VCD, several criteria have been proposed: successful deployment with immediate hemostasis in ≥ 98% of procedures, reduction of device-related major vascular complications to ≤ 1%, versatility to adapt to challenging anatomies, universal applicability with minimal exclusions, user-friendliness, easy access to the arterial site after closure, and the potential for early ambulation.5 Such a perfect closure device, however, is still far from being a reality, which is why VCD innovation must continue to minimize vascular complications and achieve such goals.

A less well studied yet undoubtedly pivotal variable to achieve favorable outcomes with any VCD is the operator’s experience, which is key to guaranteeing closure success and reducing VCD-related complications. However, measuring, quantifying, and analyzing this variable across different studies is a daunting task. Thus, although the perfect device may never become a reality, there will always be experienced operators who prefer certain types of VCDs.

With the current results, the decision to choose one VCD over another should be based on the patient’s anatomy and basically on the operator’s preferences and experience. An important consideration is that, to date, the MANTA device is more expensive than ProGlide, which, added to the substantially larger number of patients treated with TAVI, could pose a major obstacle to its selection in preference to suture-based systems.

In the meantime, we should consider innovations and technological advancements in the field of VCDs as welcome news for the interventional community. Soon, these advancements will likely position TF-TAVI as the technique of choice for most patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Goldsweig AM, Secemsky EA. Vascular Access and Closure for Peripheral Arterial Intervention. Intervent Cardiol Clin. 2020;9:117-124.

2. Montalto C, Munafo` AR, Arzuffi L, et al. Large-bore arterial access closure after transcatheter aortic valve replacement:a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;2:1-9.

3. Carroll JD, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S, et al. STS-ACC TVT registry of transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2492-2516.

4. Bhogal S, Waksman R. Vascular Closure:the ABC's. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2022;24:355-364.

5. Abbott JD, Bavishi C. In Search of an Ideal Vascular Closure Device for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:158-160.

6. van Wiechen MP, Tchétché D, Ooms JF, et al. Suture- or Plug-Based Large-Bore Arteriotomy Closure:A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:149-157.

7. Sohal S, Mathai SV, Nagraj S, et al. Comparison of Suture-Based and Collagen-Based Vascular Closure Devices for Large Bore Arteriotomies —A Meta-Analysis of Bleeding and Vascular Outcomes. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis. 2022;9:331-342.

8. Sedhom R, Dang AT, Elwagdy A, et al. Outcomes with plug-based versus suture-based vascular closure device after transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;101:817-827.

9. Van Mieghem NM, Latib A, van der Heyden J, et al. Percutaneous plug-based arteriotomy closure device for large-bore access:a multicenter prospective study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:613-619.

10. Wood DA, Krajcer Z, Sathananthan J, et al. SAFE MANTA Study Investigators. Pivotal clinical study to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the MANTA percutaneous vascular closure device. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007258.

11. Dumpies O, Kitamura M, Majunke N, et al. Manta versus Perclose ProGlide vascular closure device after transcatheter aortic valve implantation:initial experience from a large European center. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;37:34-40.

12. Abdel-Wahab M, Hartung P, Dumpies O, et al. Comparison of a Pure Plug-Based Versus a Primary Suture-Based Vascular Closure Device Strategy for Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:The CHOICE-CLOSURE Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2022;145:170-183.

13. Martinho S, Jorge E, Marinho V, Baptista R, Costa M, Gonçalves L. The MANTA vascular closure device in transfemoral TAVI:a real-world cohort. REC Interv Cardiol. 2024;6:7-12.

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

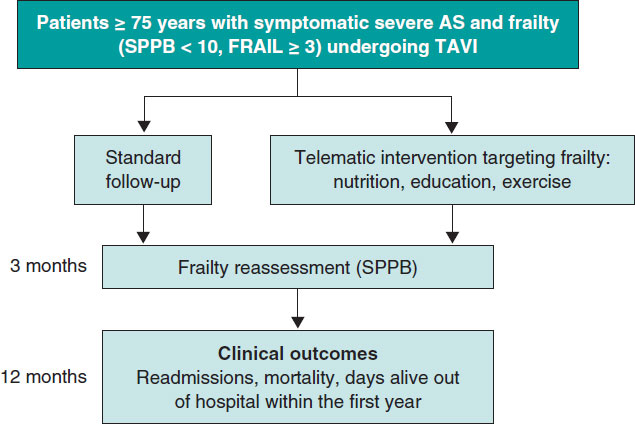

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España