Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

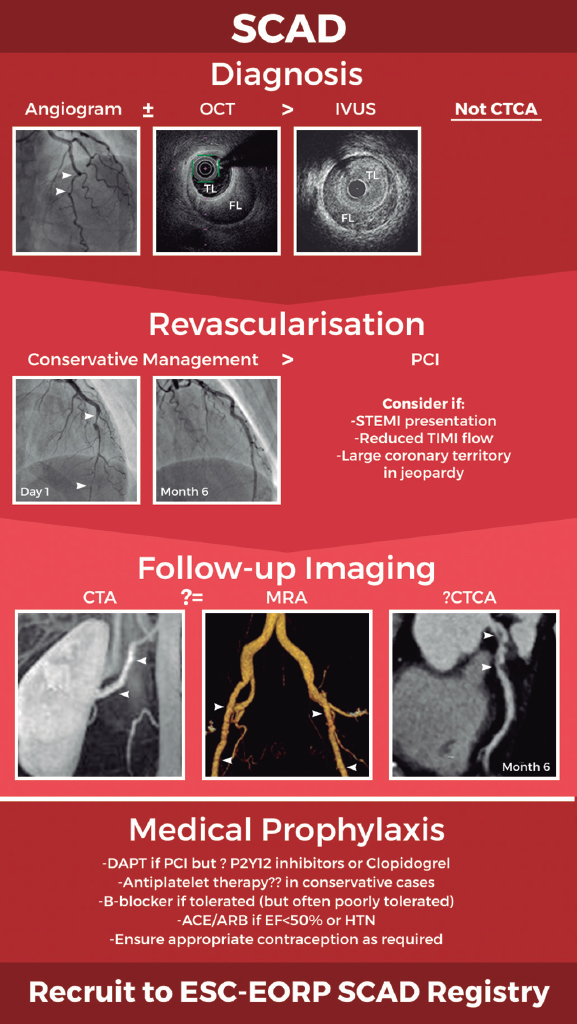

Over the last decade, understanding of spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) has progressed from a condition once considered very rare and the subject largely of esoteric case reports to a disease now recognised as a significant cause of acute coronary syndromes, predominantly in young to middle-aged women. Large observational series have been presented, led by groups in the Mayo Clinic, United States and Vancouver, Canada.1-3 This increased understanding has led to the publication of consensus documents on best practice in both the US and Europe.4,5 Despite this, SCAD remains a condition devoid of randomised clinical trial data and debate continues over many aspects of what constitutes optimal management.

In a recent article published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Bastante et al.6 present data on a highly characterised series from a Spanish centre at the forefront of the progressive management of this condition. Their data provide supporting evidence on findings of direct clinical relevance to contemporary clinical practice and provides novel insight, particularly into the relative merits of antiplatelet therapies for this condition.

The Yip-Saw angiographic classification for SCAD7 coupled with an increased recognition of the central role of intracoronary imaging to aid diagnosis where there is uncertainty, particularly with optical coherence tomography,8 has greatly enhanced the accurate diagnosis of SCAD in the cardiac catheterisation laboratory. In common with other more contemporary and prospective series where there is likely to be less selection bias,2,9 Bastante et al. report SCAD occurring in an older (median age 56), predominantly peri- and post-menopausal female population with a risk factor profile more akin to an age matched general population (48% current or ex-smoker, 36% hypertension, 42% hypercholesterolaemia).6 This further debunks an oft-repeated mantra that SCAD is a disease of pre-menopausal women with few conventional risk factors for ischaemic heart disease. In this and some other studies, only diabetes (6%) seems less prevalent than in the general population. It is interesting to speculate as to whether the adverse vascular effects of diabetes may paradoxically protect against SCAD. Most importantly however, these data remind clinicians not to restrict their consideration of the diagnosis of SCAD to low risk pre-menopausal females.

Accurate diagnosis is the key first management step for SCAD. This paper gives important insights into the diagnostic role of computed tomography coronary angiography (CTCA). It demonstrates that even in a context where the site of SCAD is known from invasive angiography, conventional CTCA missed more than 20% of SCAD locations. This finding confirms that although CTCA is a tempting non-invasive substitute for angiography (particularly given the known increased risk of iatrogenic dissection during invasive angiography in this population10), this approach should not be used for the primary diagnosis of SCAD. The inadequate sensitivity and specificity of CTCA for this diagnosis likely arises because SCAD has a predilection for the mid-distal coronary arteries (76% of cases in this series) where coronary diameters approach the effective spatial resolution of current CTCA technologies. Whether CTCA could still be useful in specific clinical contexts, for example to exclude or to follow progression of high-risk proximal-to-mid vessel dissections, remains to be elucidated.

A key difference between the management of SCAD and atherosclerotic acute coronary syndromes is the increased risk of complications during percutaneous coronary intervention following SCAD. This, coupled with high reported rates of complete healing in conservatively managed SCAD has led to a consensus favouring a non-interventional strategy where possible.4,5 This approach is further supported by the recent demonstration of relatively small infarct sizes in most convalescent SCAD-survivors assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, with larger infarcts predicted by ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction presentation, reduced TIMI flow and more proximal or extensive dissections.11 In the paper by Bastante et al. 82% of patients were managed conservatively.6 This is in keeping with a large recent prospective Canadian series and suggests that in experienced centres, most SCAD can be managed without percutaneous coronary intervention.2

Optimal medical management following diagnosis remains unclear. This becomes particularly relevant when considering the optimal long-term antiplatelet treatment strategy after SCAD. Antiplatelet therapies have become a mainstay of treatment for atherosclerotic acute coronary syndromes which are characterised by the formation of luminal thrombus on ruptured or eroded atherosclerotic plaque. However, this paper confirms previous findings12 that the burden of true luminal thrombus in SCAD is low, leading the authors to adopt a clinical strategy of early aspirin monotherapy in conservatively managed SCAD (only 7/27 such patients were managed with dual antiplatelet therapy). The longer-term justification for maintenance aspirin has also been questioned as it appears somewhat counter-intuitive to use a medication that prolongs bleeding time as prophylaxis for a condition whose primary pathophysiological event seems to be the development of a spontaneous intramural haematoma. The only potentially informative clinical data come from a single Canadian observational series and found no definitive benefit or harm.1 However, these findings have not yet been validated in other series and whilst this report from Bastante et al.6 will add further fuel to this debate, clinical trial data are urgently needed to address this question.13

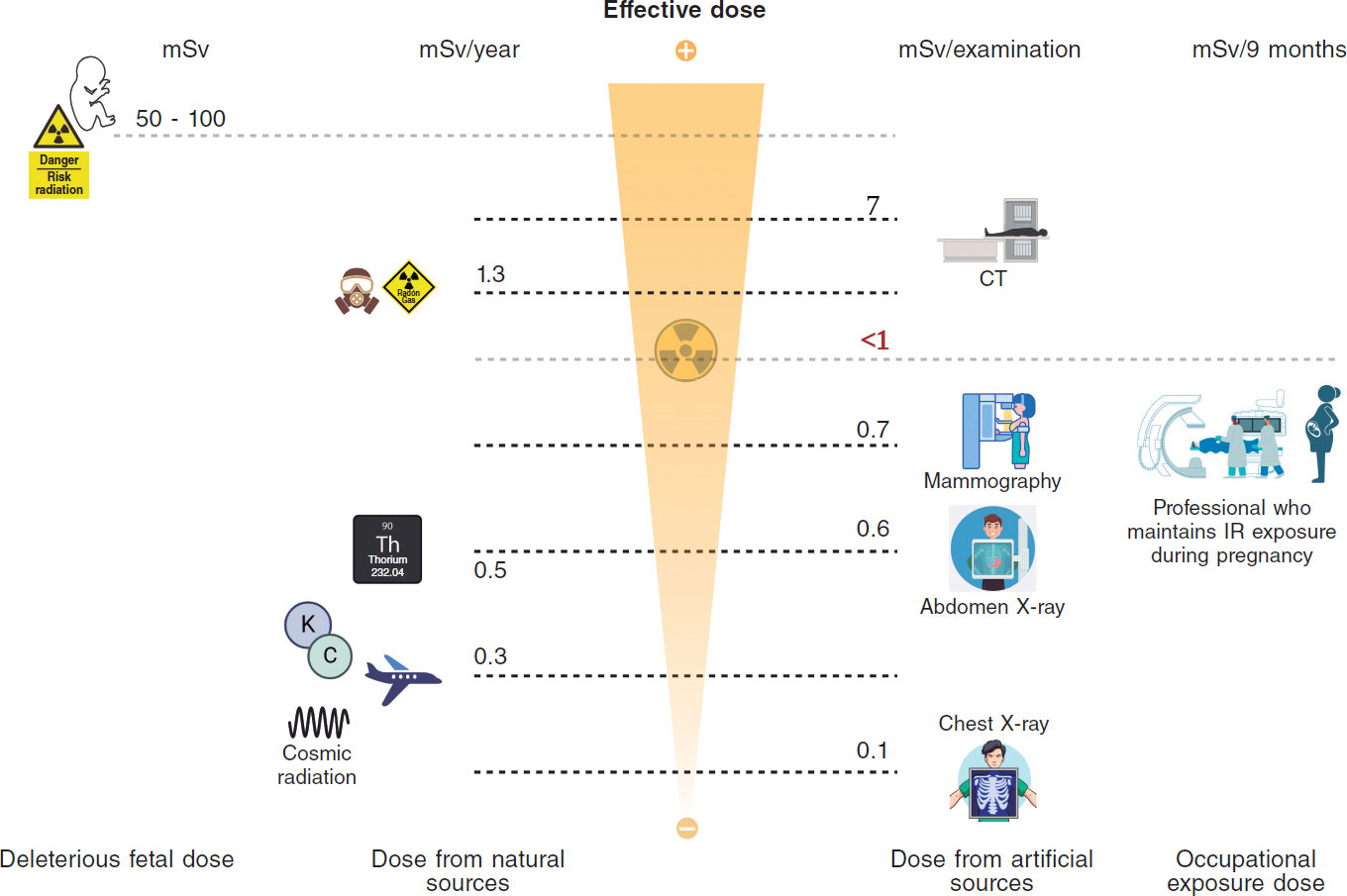

The recognition of extra-coronary arteriopathies in SCAD patients14 has led to a consensus favouring arterial screening by brain to pelvis imaging in all SCAD-survivors.4,5 However, it is important to demonstrate that imaging has the potential to alter clinical management or prevent vascular events, especially given the associated X-ray dose if computed tomography arteriography is used.

This is particularly relevant as the most frequent arteriopathy in SCAD survivors is fibromuscular dysplasia which although common, seems of little clinical consequence in most cases. Therefore, the report by Bastante et al.6 of 3 patients in whom intra-cerebral aneurysms identified during screening required closure provides some additional much-needed supportive data that at minimum intracerebral arterial imaging is indeed merited in SCAD-survivors.

Finally and most importantly for patients, Bastante et al. complement data from other series suggesting that although major adverse cardiovascular events (18%) and SCAD recurrence (12%) are significant problems for SCAD-survivors, the disease-related mortality following SCAD is very low.6 Prevention of SCAD recurrence is therefore the key target for clinical trials targeting improved outcomes in SCAD.

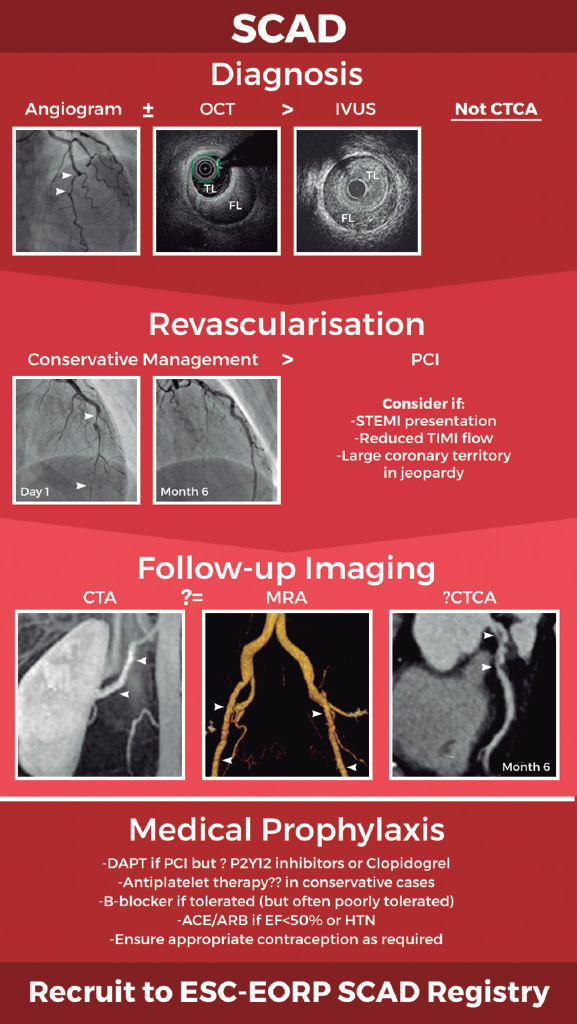

In summary, there has been a paradigm shift in our knowledge of SCAD leading to improved diagnostic accuracy and increasing adoption of a conservative revascularisation strategy (figure 1). However, key questions remain about optimal long-term medical prophylaxis and the best approach to follow-up imaging. International collaboration will be key to generating the data required to definitively address these questions and ensure we continue to improve our approach to the management of this important condition. Recruitment of patients to the new European Society of Cardiology EURObservational Research Programme SCAD registry (CPMS No. 44577, IRAS No. 270314)15 will provide a key platform for future research.

Figure 1. Schematic of current optimal management approach to spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD). Invasive coronary angiography supported by intracoronary imaging if needed remains the diagnostic gold-standard. A conservative approach to revascularisation is favoured except in more extreme presentations. Screening for remote arteriopathies is recommended but the optimal imaging modality and the role of computed tomography coronary angiography remain unclear. Optimal medical management is unknown. All images are from patients from the UK SCAD study (ISRCTN42661582; REC14/EM/0056). ACE/ARB, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor antagonists; CTA, computed tomography arteriography; CTCA, computed tomography coronary angiography; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; ESC-EORP, European Society of Cardiology European Observational Research Programme; FL, false lumen; HTN, hypertension; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MRA, magnetic resonance angiography; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TL, true lumen.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

D. Adlam has received research funds and in kind support from AstraZeneca, including for spontaneous coronary artery dissection research. He has also received an educational grant from Abbott Vascular to support a clinical research fellow and has conducted consultancy for General Electric, Inc. to support research funds. D. Kotecha has no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

1. Saw J, Humphries K, Aymong E, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection:Clinical Outcomes and Risk of Recurrence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1148-1158.

2. Saw J, Starovoytov A, Humphries K, et al. Canadian spontaneous coronary artery dissection cohort study:in-hospital and 30-day outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1188-1197.

3. Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012;126:579-588.

4. Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C, Writing C. European Society of Cardiology, acute cardiovascular care association, SCAD study group:a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3353-3368.

5. Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al.;American Heart Association Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease;Council on Clinical Cardiology;Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing;Council on Genomic and Precision Medicine;and Stroke Council. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection:Current State of the Science:A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e523-e557.

6. Bastante T, García-Guimaraes M, Muñiz M, et al. Contemporary management of spontaneous coronary dissection. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M20000096.

7. Yip A, Saw J. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection-A review. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2015;5:37-48.

8. Alfonso F, Paulo M, Gonzalo N, Dutary J, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Lennie V, Escaned J, Banuelos C, Hernandez R, Macaya C. Diagnosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection by optical coherence tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1073-1079.

9. Adlam D, Garcia-Guimaraes M, Maas A. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection:no longer a rare disease. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1198-1201.

10. Prakash R, Starovoytov A, Heydari M, Mancini GB, Saw J. Catheter-Induced Iatrogenic Coronary Artery Dissection in Patients With Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1851-1853.

11. Al-Hussaini A, Abdelaty A, Gulsin GS, et al. Chronic infarct size after spontaneous coronary artery dissection:implications for pathophysiology and clinical management. Eur Heart J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz895.

12. Jackson R, Al-Hussaini A, Joseph S, et al. Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection:Pathophysiological Insights From Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:2475-2488.

13. Tweet MS, Olin JW. Insights Into Spontaneous Coronary Artery Dissection:Can Recurrence Be Prevented?J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1159-1161.

14. Prasad M, Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Leng S, Liang JJ, Eleid MF, Gulati R, Vrtiska TJ. Prevalence of extracoronary vascular abnormalities and fibromuscular dysplasia in patients with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1672-1677.

15. European Society of Cardiology. European Society of Cardiology EURObservational Research Programme SCAD registry. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/Research/Registries-&-surveys/Observational-research-programme/spontaneous-coronary-arterious-dissection-scad-registry. Accessed 8 Jun 2020.

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is the most prevalent form of valve disease in developed countries1 and its prevalence increases with age affecting ~10% of people > 75 years.2MR is a very heterogenous disease that damages not only the mitral valve apparatus but also its surrounding structures. In primary MR, mitral valve surgery is the therapy of choice in symptomatic patients or asymptomatic patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Surgical repair is generally preferred over replacement if technically feasible.3,4 In secondary MR, the surgical approach is still under discussion5 and it is spared for patients with indications for other surgical cardiac procedures (ie, coronary artery bypass graft).3,4

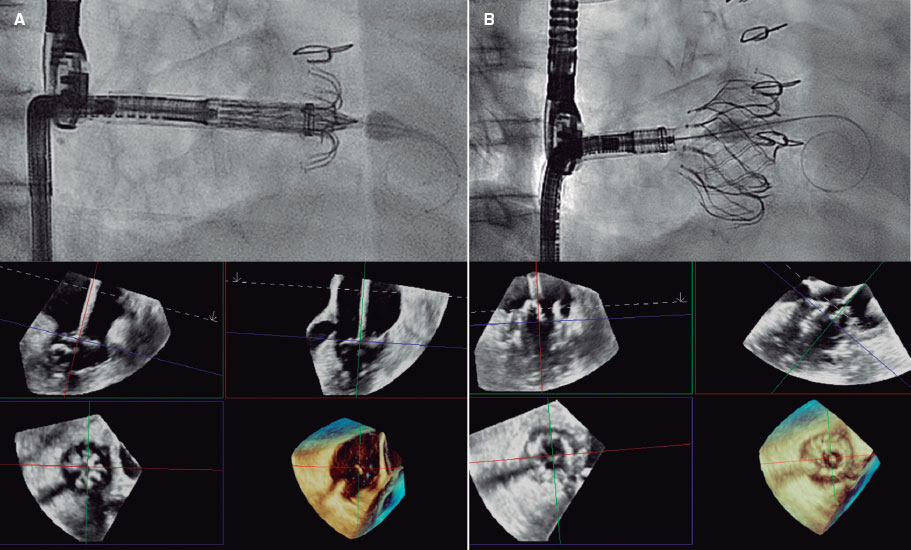

Several studies suggest that a large proportion of MR patients are never treated due their high surgical risk6 and that such a conservative approach results in high re-hospitalization (~90%) and mortality rates (50%) within 5 years following the initial diagnosis.7This population has become a clear unmet need and a target for the development of less invasive therapeutic approaches. Several transcatheter mitral valve repair (TMVR) technologies inspired by well-established surgical techniques have been developed and have already been approved for clinical use. The most commonly used, the MitraClip device (Abbott Vascular, United States) has reached more than 100 000 implants and demonstrated safety and efficacy in several MR subsets.8-10 Although clinical adoption continues to increase, edge-to-edge repair does not fully resolve MR and has some anatomical limitations too (ie, calcified leaflets) that prevent a wider use. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) offers a more universal concept for the management of mitral valve disease with a more predictable abolition of MR severity in a procedure that could be less invasive compared to current surgical techniques.11

Important lessons have been learned from ongoing TMVR clinical studies. First, the patients screened for these trials, considered of high or prohibitive surgical risk display more complex anatomical substrates than originally thought that lead to very high rejection rates. Imaging sizing algorithms used to confirm patient eligibility are patient- and valve-design specific, but have not been standardized in all valve programs. The availability of different device sizes has also limited the wider adoption of this technology.

One of the biggest earliest technical concerns was the ability to achieve valve stability in the absence of sutures. To tackle this issue, several anchoring mechanisms have been developed resulting in high periprocedural success and low early dislodgment rates.12 The potential for left ventricular outflow tract obstruction is still the biggest Achilles’ heel of this technology. Several factors including13 aorto-mitral-annular angle, degree of septal hypertrophy, the left ventricle size, and device protrusion into the cavity may contribute to left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. The short and mid-term valve leaflet performance has not been an issue to this day. Mean transvalvular gradients and paravalvular leaks have been similar to those obtained after surgical mitral valve replacement.

The rate of periprocedural complications varies based on the valve program we are dealing with. The mean 30-day all‐cause mortality reported is ~13.6%.14 Approximately 4.6% of periprocedural death rate mainly due to unsuccessful TMVR deployment that ends up leading to conversion to open heart surgery. Also, issues with the management of access site are responsible for some deaths mainly associated with myocardial tears. The remaining deaths occur following the TMVR procedure. Transapical access has been associated with a higher rate of periprocedural complications (particularly bleeding) and mortality in TMVR procedures.14 The negative effects of thoracotomy in frail populations and the higher degree of myocardial injury associated with the transapical approach may be particularly deleterious in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction.14 Finally, acute hemodymamic changes due to valve implantation in patients with severely depressed left ventricular ejection fraction (< 30%) is a very well-known phenomenon in the surgical field that worsens the prognosis of these patients.

Long-term data in a large cohort of patients is still lacking. In the largest series reported so far, no cases of structural valve degeneration, new occurrence of paravalvular leaks or valve dislocation requiring reintervention have been reported.14 However, a more systematic clinical and echocardiography follow-up of patients undergoing TMVR is crucial to provide consistent data on valve durability and structural valve failure in the future. Data on the risk of long-term thrombosis is scarce too. No episodes of clinically relevant valve thrombosis have been reported with other TMVR devices. Three-month anticoagulation therapy is currently recommended although no long-term data on the real thrombogenic profile of these devices has been reported yet.3,4,15

TMVR is evolving to become a new alternative for treating patients with severe MR of very high or prohibitive surgical risk. The complexity of the mitral valve apparatus and the heterogeneity of the disease have limited the wide adoption of these technologies. Several devices are under clinical evaluation and the early experience gained with some of them proves the feasibility of their implantation. Larger studies including a larger number of patients are still needed to test the clinical performance of these technologies. Emerging transseptal TMVR systems have the potential to overcome some of the limitations of current transapical devices. However, technical and anatomical challenges will remain the same. The TMVR field is rapidly evolving, what is somehow clear now is that it will benefit a specific population subset and that there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all solution.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The CRF Skirball Center for Innovation has received research grant support from Edwards Lifesciences, Neovasc, Abbott Vascular, Sinomed and Cephea. J.F. Granada is one of the co-founders of Cephea.

REFERENCES

1. Coffey S, Cairns BJ, Iung B. The modern epidemiology of heart valve disease. Heart. 2016;102:75-85.

2. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases:a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005-1011.

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 aha/acc guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:252-89.

4. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739-2791.

5. Acker MA, Parides MK, Perrault LP et al. Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:23-32

6. Mirabel M, Iung B, Baron G, et al. What are the characteristics of patients with severe, symptomatic, mitral regurgitation who are denied surgery?Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1358-1365.

7. Goel SS, Bajaj N, Aggarwal B et al. Prevalence and outcomes of unoperated patients with severe symptomatic mitral regurgitation and heart failure:comprehensive analysis to determine the potential role of MitraClip for this unmet need. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:185-186.

8. Feldman T, Kar S, Elmariah S et al. Randomized Comparison of Percutaneous Repair and Surgery for Mitral Regurgitation:5-Year Results of EVEREST II. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2844-2854.

9. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307-2318.

10. Obadia JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, Leurent G, et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2297-2306.

11. Maisano F, Alfieri O, Banai S, et al. The future of transcatheter mitral valve interventions:competitive or complementary role of repair vs. replacement?Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1651-1659.

12. Regueiro A, Granada JF, Dagenais F, Rodes-Cabau J. Transcatheter mitral valve replacement:insights from early clinical experience and future challenges. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2175-2192.

13. Meduri CU, Reardon MJ, Lim DS, et al. Novel multiphase assessment for predicting left ventricular outflow tract obstruction before transcatheter mitral valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:2402-2412.

14. Del Val D, Ferreira-Neto AN, Wintzer-Wehekind J, et al. Early experience with transcatheter mitral valve replacement:a systematic review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e013332.

15. Pagnesi M, Moroni F, Beneduce A, et al. Thrombotic risk and antithrombotic strategies after transcatheter mitral valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:2388-2401.

-

«Don’t say anything online that you wouldn’t want plastered on a billboard with your face on it.»

Erin Bury, Sprouter community manager

Scientific dissemination has always been at the forefront of medicine. It consists of bringing the advances made in research to all professionals and the general population. The traditional way to do this was through books. However, the growing accumulation of knowledge and the need to communicate it in a timely manner prompted the appearance of periodic publications: the scientific journals.

Currently, the enormous speed at which knowledge is generated and the lust for knowledge have found an ally in the Internet and the inevitable social media. The possibilities are just amazing, and they allow the spread of ideas and opinions with greater impact in education, networking, and public health. 1,2

In our journal, Jurado-Román reviewed the role of social media in the educational setting and highlighted its importance without obviating its potential risks and limitations.3,4 Some have already coined the term “twitterology” to refer to the medical use of this social network.5

Over the last year an example of this have been the ISCHEMIA and PARTNER-3 landmark clinical trials that have prompted ongoing discussion and debate on social media.6,7 But new studies do not have the monopoly on this. We have also witnessed fierce debates about a not so recent trial that gave rise to methodological considerations; I am referring to the EXCEL trial and the update of its 5-year results.8-11

The recent pandemic of COVID-19 has been the largest dissemination of medical-scientific information on social media ever. We have learned so much from this world-shocking experience in this regard.

CHARACTERISTICS AND PREVALENT VALUES OF COMMENTS POSTED ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Here is a brief description of the characteristics of communication in social media based on what is being posted on a daily basis.

Totally open access

Anybody can post their opinion or comment on social media. This means that the capacity to spread knowledge has been democratized with the corresponding benefits and risks involved. There is no peer review nor filters on authors or content. Rigor and truth are not guaranteed either, only if imposed by the author himself.

Communication on real time and immediacy

The comments are published and available online immediately. There are no delays anymore. Communication needs to happen as quickly as possible after public exposure or after the publication of the study or even better during its presentation at the congress. Being the “first to shoot” is the only thing that matters.

Concision

These comments are limited in size and thoughts on a particular study have to be summarized in a few words. Regarding Twitter, complexity has to be summarized in just 280 characters. Simplicity over concision is the rule to follow.

Impact

Communication needs to generate sensations and induce reactions whether of agreement or of rejection; anything goes but indifference.

The group: tribalism

The study results perceived as favorable are cheered by the group and those considered negative are ignored, questioned or even rejected in a sort of medical tribalism already identified and questioned by some.12 This mimics the fierce style of political or football discussions.

The influencer

The communicator becomes the “man of the hour”; it is not about the actual value of the message anymore but about the messengers themselves. The author feels compelled to comment on all studies. These comments are awaited by those who receive them with sympathy or rejection. These influencers have followers who can’t wait to give their feedback as well; this division is related to the author’s profession and the group represented by the author.

The reactions

Reactions are subject to similar conditions. However, in this case, they may not be preceded by the acquisition of information and reflection on the opinion given; feedback is posted in a rather direct way often guided by feelings and emotions rather than reason. There are times that the comment is posted simply because a certain opinion is expected to be given by the author’s professional group.

-

«Twitter is a great place to tell the world what you’re thinking before you’ve had a chance to think about it.» Christopher J. Pirillo, blogger

THE REAL VALUES OF SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSION

Having said all this, we should not forget about the real values of scientific communication. The interpretation of a study requires a detailed analysis of methods and results, confirmation through previous studies, and the assessment of the different interpretations given. All of it requires elaborating and presenting one’s personal opinion in the most basic way possible. This process takes time, space, and moderation. That is the only way to achieve precise and balanced results.

The rule of the 3 Rs to have a scientific debate on social media: rigor, responsibility, and respect

The contrast between the characteristics and values of success on social media and the real values that should inspire scientific discussion is obvious. The only way to bring together the true virtues of both is through the commitment to communicate with rigor, responsibility, and respect:

-

– Rigor. Scientific rigor, that is, sticking to the actual content of a study and what it is actually implied regardless of the prejudices or preferences of the group we belong to.

-

- Responsibility. Responsibility with the professional group that will be following the comments posted —not always experts— and many times not even health professionals but patients, families, and the general population. The effect on the latter —who don’t have the same critical capacity as experts— can be misleading, alarming or doubtful.

-

– Respect. Respect to professionals from other groups and subspecialties, especially those capable of interpreting things differently. Topics often admit different readings in such a complex setting as ours. Respect to the population who can have access to this information, such as patients and families.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SCIENTIFIC COMMUNICATORS ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Before posting anything on social media you should inform yourself, delve into the studies, think about your interpretation, and reflect on the reactions your post might generate. Take your time and don’t be obsessed with the topic under discussion right away. Don’t try to amaze everyone at all times, but shake consciences to a certain point, appeal to reason rather than feeling, and respect other people’s opinions.

To mitigate the effects of tribalism it is essential to recognize the natural tendency to create an us-vs-them-based state of opinion and to move away from such a state towards a more problem-focused approach. Group-based approaches should be left aside to favor a more positive collaboration and interaction with others.12

Finally, take your time to fight back, but do not do it right away. The true value should be in the message, not the messenger. If you respect privacy, listen more than you talk, see things from the other people’s perspective, and focus only on doing good to others, then you cannot go wrong.13

I would like to conclude with a quote by social media expert Erik Qualman that perfectly summarizes this editorial: «We don’t have a choice on whether we do social media, the question is how well we do it».

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

J. M. de la Torre Hernández has received funding to conduct his study from Abbott Medical, Biosensors, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Amgen; he has also received funding for his work as a consultant for Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biotronik, and Daiichi-Sankyo.

REFERENCES

1. Snipelisky D. Social Media in Medicine:A Podium Without Boundaries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2459-2461.

2. Hawkins CM, Hillman BJ, Carlos RC, Rawson JV, Haines R, Duszak R Jr. The impact of social media on readership of a peer-reviewed medical journal. J Am Coll Radiol. 2014;11:1038-1043.

3. Jurado-Roman A. Redes sociales como medio educativo en la cardiología intervencionista. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;2:73-74.

4. Yeh RW. Academic cardiology and social media:navigating the wisdom and madness of the crowd. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e004736.

5. Anand A. “Twitterology“:A new age of medicine and social media colliding. Available online:https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/24745332.2017.1382316. Accessed 13 Jan 2020.

6. International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches –ISCHEMIA. En:AHA 2019. American Heart Association Annual Scientific Sessions;2019 Nov 14-16. Filadelfia, Estados Unidos. Available online:https://professional.heart.org/professional/ScienceNews/UCM_505226_ISCHEMIA-Clinical-Trial-Details.jsp. Accessed 13 Jan 2020.

7. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. PARTNER 3 Investigators. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

8. Stone GW, Kappetein AP, Sabik JF, et al. Five-Year Outcomes after PCI or CABG for Left Main Coronary Disease. EXCEL Trial Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1820-1830.

9. Cohen D, Brown E. Surgeons withdraw support for heart disease advice. Available online:https://www.bbc.com/news/health-50715156. Accessed 13 Jan 2020.

10. Genereux P, Gersh BJ, Gershlick A, et al.;for the EXCEL trial leadership. Official Response from EXCEL Leadership. Available online:https://www.tctmd.com/slide/official-response-excel-leadership. Accessed 13 Jan 2020.

11. Taggart D. Response by David Taggart, MD, PhD to the EXCEL Statement. Available online:https://www.tctmd.com/slide/response-david-taggart-md-phd-excel-statement. Consultado 13 Ene 2020.

12. Mannix R, Nagler J. Tribalism in Medicine - Us vs Them. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:831.

13. Mandrola J. RESPONSE:The Necessity of Social Media Literacy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:2461.

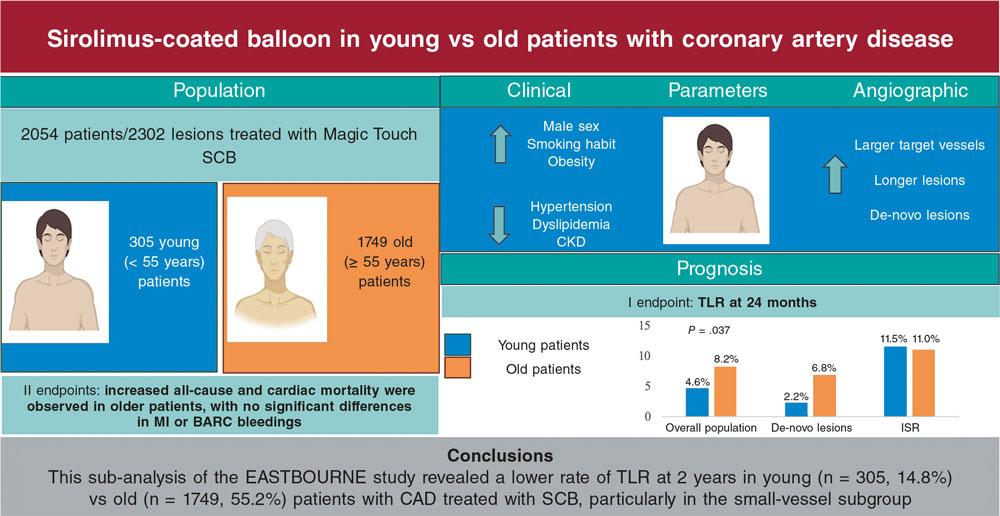

INTRODUCTION

The history of coronary balloon angioplasty began in 1997 with the first percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) ever performed by Andreas Grüntzig.1 Some of the limitations of this technology were solved with the introduction of stents.2 Added to an improved pharmacological concomitant therapy in the form of dual platelet inhibition,3 the local drug delivery initially through stents (drug-eluting stents, DES)4 and then balloons (drug-coated balloons, DCB)5 improved long-term outcomes significantly. The history of coronary angioplasty was summarized in detail in various articles on the 40th anniversary of this technology.6,7

The local application of paclitaxel through DCB had begun to revolutionize the treatment of peripheral arterial disease (PAD).8 This advance was very helpful for patients regarding primary patency and quality of life, but received a severe setback in a meta-analysis that claimed that the use of paclitaxel DES and DCB was associated with a higher mortality rate at the 2- and 5-year follow-up.9

The objective of this editorial is to discuss the safety profile of drug-coated devices in the historical context of the 2006 “European Society of Cardiology (ESC) firestorm” on coronary DES, data available on the coronary use of paclitaxel coated devices, and the potential role of limus-based agents in DCB.

FIRST-GENERATION DES AND THE 2006 “ESC FIRESTORM”

After the publication of the RAVEL clinical trial on the Cypher sirolimus-eluting stent4 and the TAXUS trials on the Taxus paclitaxel-eluting stent,10 the DES rapidly gained momentum thanks to their significantly lower rate of restenosis compared to uncoated bare metal stents (BMS). In a direct comparison with the Cypher stent, the Taxus showed a higher rate of recurrence at the 9- to 12-month follow-up.11 The common view that sirolimus is more effective than paclitaxel is essentially based on these data. However, it should be emphasized that the Taxus stent was almost as effective as the Cypher stent beyond the 12-month follow-up and up to 10 years.12 The progress made by these first-generation DESs compared to modern DESs was based on the nowadays better controlled coating processes especially after improving stent platforms with thinner stent struts.13

However, there were also critical remarks to be made on the safety profile of coronary DESs. It has been reported that the delayed drug delivery from the stent struts prevents the implant endothelialization and increases the risk of thrombotic occlusion of the stent.14 The BASKET-LATE trial reported between 3 and 4 times more late deaths or myocardial infarctions15 with first-generation DESs. A hotline session held in Barcelona at the ESC congress of 2006 reported on 2 meta-analyses on a safety risk after sirolimus DES implantation.16,17 In both meta-analyses the events published at study level were divided by the total number of patients with intention-to-treat without observation of cross-over treatments and lost to follow-up numbers. This is similar to the recently controversial meta-analysis on paclitaxel coated devices for the management of PAD.9 The first DES meta-analysis showed significant differences in the mortality and Q-wave myocardial infarction rate at the late follow-up when the Cypher and bare metal stents were compared.16 This finding may be explained by a possibly higher rate of late stent thrombosis. However, the second meta-analysis showed that the higher mortality rate associated with the Cypher stent was due to a higher non-cardiac mortality rate, thus contradicting the mechanism of stent thrombosis.17 Despite these conflicting results, the government regulatory agencies worldwide were alarmed. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published several warning letters that eventually limited the indications for DESs.18 However, further analyses did not confirm such an increased risk.19 Also, the clinical trials that compared the Taxus stent to the BMS or the Cypher did not show higher rates of myocardial infarction or death.10,12 Thus, DES became the standard treatment for the management of coronary heart disease.20 Similarly, large contemporary registry studies and randomized studies have not confirmed any mortality signals for paclitaxel devices for the management of PAD21-24 It remains to be seen whether a similar comeback as with coronary DES will eventually happen.

PACLITAXEL-COATED BALLOONS

Currently, the clinical practice guidelines recommend DCBs for the management of in-stent restenosis (ISR) only.20 However, there is an increasing number of positive data on the treatment of de novo stenoses, particularly in small coronary vessels25,26 and risk indications.27,28 A patient-based meta-analysis of the trials that compared DCBs and DESs in DES-treated ISRs showed a similar 3-year safety profile for DCBs and DESs with numerically lower rates of events with DCB.29 Even individual studies that compared DCB with first-generation DES,30 BMS,27 or plain old balloon angioplasty31,32 reported significantly lower mortality rates after DCB implantation in the long term. However, these studies did not have enough statistical power to analyze this question. A recent meta-analysis of all randomized data on DCBs showed no differences in the mortality rate of DCBs and alternative treatments at the 1- and 2-year follow-up, but a significant survival benefit for DCBs regarding all-cause mortality and cardiac mortality at the 3-year follow-up.33

SIROLIMUS VS PACLITAXEL FOR LOCAL DRUG DELIVERY

When comparing paclitaxel and sirolimus regarding local drug delivery it is often said that sirolimus has a wider therapeutic window and paclitaxel is cytotoxic. However, these statements are not correct.

Cell culture experiments tell us that the exposure of smooth muscle cells or endothelial cells to paclitaxel leads to more pronounced dose-depending growth inhibition compared to sirolimus.34,35 There is an increasing release of cytosolic lactate dehydrogenase—a marker for cell death—when incubating the cells with paclitaxel from a concentration of ≥ 100 ng/mL.34 It should be mentioned that the paclitaxel DES only released 10% of the total amount of drug just as the comparable sirolimus DES because of this stronger antiproliferative effect. Regarding DCB, there are typically acute tissue levels of less than 100 ng/mg in the vessel wall.36 Also, only about 10 ng/mg of paclitaxel are biologically active. Otherwise, the solubility product in the tissue is exceeded. While toxic concentrations may well be reached in the DES in the area of the stent struts, distribution in the vessel wall is very homogeneous with local drug delivery through DCB.37 Also, tissue concentration decreases very rapidly after DCB treatment.36 Therefore, the theoretically possible cytotoxicity of paclitaxel is not a factor in the clinical use of DCB.

The second myth is the therapeutic window. A typical total dose of a paclitaxel DCB equals 0.4 mg (3 µg/mm2, 20 mm length, 3 mm diameter). The single dose per cancer treatment cycle is 100-175 mg/m2 of body surface area through intravenous administration,38 usually 300 mg per infusion. This results in a factor of 750 for paclitaxel as therapeutic window compared to systemic therapy. The typical daily oral dose of sirolimus for restenosis prevention is 2 mg.39 Depending on the specific sirolimus DCB used, the balloon dose is somewhere between 0.2 and 0.6 mg (1-4 µg/mm2, 20 mm length, 3 mm diameter). So far, clinical efficacy could only be proved for the high dose of sirolimus,40 which means a factor of 3 only compared to systemic therapy, a clearly smaller therapeutic window. If a sirolimus DCB is implanted on the superficial femoral artery, the dose delivered through the balloon is already above the systemic dose and should be contraindicated (table 1).

Table 1. Systemic vs local treatment. Therapeutic window of paclitaxel and sirolimus.

| Paclitaxel | Sirolimus | |

|---|---|---|

| Systemic treatment | 300 mg Single IV dose of 100-175 mg/m2 per cancer treatment cycle38 |

2 mg Daily oral dose for restenosis prevention39 |

| Local treatment (DCB) | 0.4 mg CAD 3.0/20 mm at 3 µg/mm2 5.5 mg PAD 5.0/80 mm at 3.5 µg/mm2 |

0.2-0.6 mg CAD 3.0/20 mm at 1-4 µg/mm2 1.6-6.4 mg PAD 5.0/80 mm at 1-4 µg/mm2 |

| Therapeutic window | CAD × 750 PAD × 55 |

CAD x 3-10 PAD none |

|

CAD, coronary artery disease; DCB, drug-coated balloons; IV, intravenous; PAD, peripheral arterial disease. |

||

DISCUSSION AND FINAL REMARKS

The 2006 “ESC Firestorm” can be seen as a blueprint for the current paclitaxel controversy on the management of PAD. Interestingly enough, discussion at that time focused on sirolimus and not on paclitaxel. The current meta-analysis on the management of PAD with paclitaxel devices has several methodical flaws and has already been refuted. In any case, it has caused great damage to the entire field of local drug delivery for restenosis prevention. Too many patients are currently not receiving the therapy that works best for them and have to receive unnecessary revascularizations.

Regarding coronary paclitaxel DCB no associated mortality signals were seen. Just the opposite, there are indications that the therapy could even offer survival advantages in the longer term by avoiding permanent implants. The alternative of a sirolimus-coated balloon endorsed by many interventional cardiologists still has to prove its clinical efficacy. However, considering the necessary local doses compared to systemic therapy, the use of a sirolimus DCB for the management of PAD is questionable.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

B. Scheller is a shareholder of InnoRa GmbH, Berlin, and co-inventor on patent applications filed by Charité university hospital, Berlin, Germany.

REFERENCES

1. Gruntzig A. Transluminal dilatation of coronary-artery stenosis. Lancet. 1978;1:263.

2. Sigwart U, Puel J, Mirkovitch V, Joffre F, Kappenberger L. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:701-706.

3. Colombo A, Hall P, Nakamura S, et al. Intracoronary Stenting without Anticoagulation Accomplished with Intravascular Ultrasound Guidance. Circulation. 1995;91:1676-1688.

4. Morice MC, Serruys PW, Sousa JE, et al. A randomized comparison of a sirolimus-eluting stent with a standard stent for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1773-1780.

5. Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W, et al. Treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2113-2124.

6. Alfonso F, Scheller B. State of the art:balloon catheter technologies - drug-coated balloon. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:680-695.

7. Byrne RA, Stone GW, Ormiston J, Kastrati A. Coronary balloon angioplasty, stents, and scaffolds. Lancet. 2017;390:781-792.

8. Tepe G, Zeller T, Albrecht T, et al. Local delivery of paclitaxel to inhibit restenosis during angioplasty of the leg. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:689-699.

9. Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, Krokidis M, Karnabatidis D. Risk of Death Following Application of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons and Stents in the Femoropopliteal Artery of the Leg:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e011245.

10. Ellis SG, Stone GW, Cox DA, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy with paclitaxel-eluting stents:5-year final results of the TAXUS IV clinical trial (TAXUS IV-SR:Treatment of De Novo Coronary Disease Using a Single Paclitaxel-Eluting Stent). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2:1248-1259.

11. Windecker S, Remondino A, Eberli FR, et al. Sirolimus-eluting and paclitaxel-eluting stents for coronary revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:653-662.

12. Yamaji K, Räber L, Zanchin T, et al. Ten-year clinical outcomes of first-generation drug-eluting stents:the Sirolimus-Eluting vs. Paclitaxel-Eluting Stents for Coronary Revascularization (SIRTAX) VERY LATE trial. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3386-3395.

13. Capodanno D. Very late outcomes of drug-eluting stents:the 'catch-down'phenomenon. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:3396-3398.

14. Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans:delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193-202.

15. Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, Buser PT, et al. Late clinical events after clopidogrel discontinuation may limit the benefit of drug-eluting stents:an observational study of drug-eluting versus bare-metal stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:2584-2591.

16. Camenzind E, Steg PG, Wijns W. Stent thrombosis late after implantation of first-generation drug-eluting stents:a cause for concern. Circulation. 2007;115:1440-1455;discussion 1455.

17. Nordmann AJ, Briel M, Bucher HC. Mortality in randomized controlled trials comparing drug-eluting vs. bare metal stents in coronary artery disease:a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2784-2814.

18. Farb A, Boam AB. Stent thrombosis redux--the FDA perspective. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:984-987.

19. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, et al. Analysis of 14 trials comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with bare-metal stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1030-1039.

20. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al.;ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

21. Secemsky EA, Kundi H, Weinberg I, et al. Association of Survival With Femoropopliteal Artery Revascularization With Drug-Coated Devices. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:332-340.

22. Freisinger E, Koeppe J, Gerss J, et al. Mortality after use of paclitaxel-based devices in peripheral arteries:a real-world safety analysis. Eur Heart J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz698.

23. Albrecht T, Schnorr B, Kutschera M, Waliszewski MW. Two-Year Mortality After Angioplasty of the Femoro-Popliteal Artery with Uncoated Balloons and Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons-A Pooled Analysis of Four Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trials. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2019;42:949-955.

24. Schneider PA, Laird JR, Doros G, et al. Mortality Not Correlated With Paclitaxel Exposure:An Independent Patient-Level Meta-Analysis of a Drug-Coated Balloon. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2550-2563.

25. Latib A, Ruparelia N, Menozzi A, et al. 3-Year Follow-Up of the Balloon Elution and Late Loss Optimization Study (BELLO). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1132-1134.

26. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2):an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392:849-856.

27. Rissanen TT, Uskela S, Eränen J, et al. Drug-coated balloon for treatment of de-novo coronary artery lesions in patients with high bleeding risk (DEBUT):a single-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2019;394:230-239.

28. Scheller B, Ohlow MA, Ewen S, et al. Randomized Comparison of Bare Metal or Drug-Eluting Stent versus Drug Coated Balloon in Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction - PEPCAD NSTEMI. EuroIntervention. 2019. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJ-D-19-00723.

29. Giacoppo D, Alfonso F, Xu B, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty vs. drug-eluting stenting for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis:a comprehensive, collaborative, individual patient data meta-analysis of 10 randomized clinical trials (DAEDALUS study). Eur Heart J. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz594.

30. Kufner S, Cassese S, Valeskini M, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloon for the Treatment of Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis:3-Year Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:877-884.

31. Rittger H, Waliszewski M, Brachmann J, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Treatment With a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Versus Balloon Angioplasty:Insights From the PEPCAD-DES Study (Treatment of Drug-eluting Stent [DES] In-Stent Restenosis With SeQuent Please Paclitaxel-Coated Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty [PTCA] Catheter). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1695-1700.

32. Scheller B, Clever YP, Kelsch B, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up After Treatment of Coronary In-Stent Restenosis With a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Catheter. J JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:323-330.

33. Scheller B. Vukadinovic D, Jeger, et al. Survival After Coronary Revascularization With Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1017-1028.

34. Wessely R, Blaich B, Belaiba RS, et al. Comparative characterization of cellular and molecular anti-restenotic profiles of paclitaxel and sirolimus. Implications for local drug delivery. Thromb Haemost. 2007;97:1003-1012.

35. Clever YP, Cremers B, Krauss B, et al. Paclitaxel and sirolimus differentially affect growth and motility of endothelial progenitor cells and coronary artery smooth muscle cells. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:K32-K42.

36. Gongora CA, Shibuya M, Wessler JD, et al. Impact of Paclitaxel Dose on Tissue Pharmacokinetics and Vascular Healing:A Comparative Drug-Coated Balloon Study in the Familial Hypercholesterolemic Swine Model of Superficial Femoral In-Stent Restenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1115-1123.

37. Scheller B, Speck U, Bohm M. Prevention of restenosis:is angioplasty the answer?Heart. 2007;93:539-541.

38. Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (taxol). N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1004-1014.

39. Waksman R, Ajani AE, Pichard AD, et al. Oral rapamycin to inhibit restenosis after stenting of de novo coronary lesions:the Oral Rapamune to Inhibit Restenosis (ORBIT) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1386-1392.

40. Ali RM, Abdul Kader MASK, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Treatment of Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis by a Sirolimus- or Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:558-566.

Over the last few years, the risk profile of patients referred to receive a coronary angiography has deteriorated and angiographic findings as well. Therefore, the progressive aging of the population and the development of better techniques to address the complexity of the different angiographic scenarios have conditioned the current situation of percutaneous coronary interventions. The balance between demand and supply in this field is in an ongoing expansion. The management of these delicate situations—which is often competence of cardiac surgery—requires profound knowledge of dedicated techniques and a precise clinical judgment.1-3 This population is often discarded for coronary artery bypass graft surgery. There are times that even percutaneous treatment is denied because of a high clinical risk or unfavorable angiographic profile.

According to different series,4 to this day complex calcified coronary lesions are a common finding in up to 25% to 30% of all percutaneous coronary interventions. De Maria et al.5 published a review on the management of calcified lesions. They portrayed an accurate, contemporary big picture on the treatment of these lesions. The review basically focused on the technologies in intravascular imaging and tools available to solve today’s technical complexities. The authors emphasize that today the objective of percutaneous coronary intervention when treating these lesions is to modify the plaque. If it fails to do so, the procedure is more likely to fail also in the clinical and technical aspects. Clinically because there would be more major complications, and techni- cally because the result would compromise stent expansion and apposition, with the resulting increase in the rates of in-stent restenosis and thrombosis, etc.6,7

Intracoronary lithotripsy (ICL) is the latest technology available for the management of severely calcified lesions. Its mechanism of action has been well described in the document. Basically, ultrasound energy interacts with the atherosclerotic plaque causing vibrations that crack and tear the calcified components of superficial and deep layers. Compared to ablation techniques, since it is based on balloons, it is easy to use and there is a short learning curve. This, together with an early apparent evidence of efficacy, suggests that it will soon become the standard of care for the management of many severely calcified lesions. Similarly, this effect on deep calcium is an important benefit of ICL compared to other plaque-modifying techniques. Compared to rotational and orbital atherectomies, both of which reduce the plaque burden, ICL does not ablate or reduce it but cracks it supposedly improving stent apposition and expansion. The long-term follow-up will confirm whether this is enough to see long-term benefits.

In a recent article published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Vilalta del Olmo et al.8 commented on their first experience with an ICL device in a high-risk population. Their data provide useful information to assess the role, safety, and feasibility profile of ICL in high-risk patients not included in other studies. The authors report on procedural success and the short-term clinical outcomes of a non-randomized registry. The data published show the utility of ICL improving the clinical and angiographic results of complex patients with advanced, diffuse, multivessel, and calcified atherosclerotic disease. Their patients often presented with critical conditions such as acute coronary syndrome or left ventricular dysfunction.

Since they recruited their first patient, many things have changed and new information has come to light. By performing OCTs in 31 patients, Ali et al.9 confirmed that ICL cracks the calcified arch in 43% of the patients with multiple fractures caused in over 25% of the cases. According to these authors, the efficacy of this technique is proportional to the burden of calcium with a higher rate of calcium fractures (77%) in cases with a higher degree of coronary calcifications. Serious safety issues or technical complications (coronary perforations, important dissections or slow flow/no reflow) have not been reported in the studies. Unlike former reports,10 Vilalta del Olmo et al.8 share encouraging data on a high-risk population with results that are as good as those from other authors.

Although the use of ICL has grown rapidly, the experience published on this device is limited, especially that coming from randomized clinical trials, and some considerations should be made on this regard. The first one is that the navigation capabilities of the device are an important limitation of this technique. Although Vilalta del Olmo et al.8 reported that the ICL balloon crossing rate was 100%, our data show that 89% of the lesions required preconditioning with balloon angioplasty (62%) or rotational atherectomy (27%). Therefore, with the current design of the ICL device, in most cases a coadjuvant technique is required prior to the ICL so it can be used effectively which increases the cost of both procedures. Secondly, since the population of the Disrupt CAD II clinical trial10 included stable patients with concentric lesions, the role of this technique in unstable patients and eccentric calcified lesions should be studied in a randomized controlled trial. Although it is a registry with a small sample size, the data from Vilalta del Olmo et al.8 are encouraging on this regard. In the third place, life often outruns science. Although it is a friendly, easy to use technique, randomized clinical trials should be performed to select the patients and establish the indications. For instance, because of the simultaneous presence of compression and decompression forces (pull and push) and the fact that flow is compromised with ICL, its role should be studied in detail in different clinical and angiographic contexts like ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, chronic total coronary occlusion via subintimal pathway, patients with pacemakers, etc. Other contexts suggested are patients with in-stent restenosis or to facilitate transfemoral access in patients with transcatheter aortic valve implantation. The fourth consideration to make is closely associated with the previous one and is inherent to any new technique: the lack of data on its use and long-term benefit. With the ICL rapid expansion we run the risk of using it in non-studied settings making it a useless and unsafe technique that may increase the rate of complications or lead to worse results. For example, a few isolated clinical cases have been reported on the role of ICL on in-stent restenosis due to stent underexpansion. The study conducted by Vilalta del Olmo et al.8 did not report on any of this. Maybe the underlying mechanism of restenosis may explain the oberved differences (underexpansion, malapposition, neoatherosclerosis, etc.). Nevertheless, we still need time to study these issues in randomized and controlled clinical trials. ICL balloon tears have also been reported with the resulting added risk.11 In the fifth place, a very important aspect is that ICL may complement other plaque- modifying techniques; its use is feasible and safe with different angioplasty balloons (non-compliant balloons, cutting balloons, and other), rotational atherectomy, etc.12

In conclusion, the ICL is a new, attractive, easy-to-learn and use technique for the management of calcified lesions. Randomized clinical trials and further data are needed to establish its indications and benefits. In the coming future this technique will probably simplify the complex procedures associated with percutaneous coronary interventions and improve the outcomes of patients.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Hahn JY, Chun WJ, Kim JH, et al. Predictors and outcome of side branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions (COBIS II registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1654-1659.

2. Burzotta F, Trani C, Todaro D, et al. Prospective Randomized Comparison of Sirolimus- or Everolimus-Eluting Stent to Treat Bifurcated Lesions by Provisional Approach. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:327-335.

3. Dahdouh Z, Roule V, DuguéAE, Sabatier R, LognonéT, Grollier G. Rotational Atherectomy for Left Main Coronary Artery Disease in Octogenarians:Transradial Approach in a Tertiary Center and Literature Review. J Interv Cardiol. 2013;26:173-182.

4. Khattab AA, Otto A, Hochadel M, Toelg R, Geist V, Richardt G. Drug-eluting stents versus bare metal stents following rotational atherectomy for heavily calcified coronary lesions:late angiographic and clinical follow-up results. J Interv Cardiol. 2007;20:100-106.

5. De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Banning AP. Management of Calcific Coronary Artery Lesions. Is it time to change our interventional therapeutic approach?JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1465-1478.

6. Lassen JF, Burzotta F, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for the left main stem and other bifurcation lesions:12th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018;13: 1540-1553.

7. Barbato E, CarriéD, Dardas P, et al. European expert consensus on rotational atherectomy. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:30-36.

8. Vilalta del Olmo V, Rodríguez-Leor O, Redondo A, et al. Intracoronary lithotripsy in a high-risk real-world population. First experience in severely calcified, complex coronary lesions. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M19000083.

9. Ali ZA, Brinton TJ, Hill JM, et al. Optical coherence tomography characterization of coronary lithoplasty for treatment of calcified lesions:first description. JACC Cardiovasc Imgaging. 2017;10:897-906.

10. Ali ZA, Nef H, Escaned J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of coronary intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified stenoses. The Disrupt CAD II Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e008434.

11. López-Lluva MT, Jurado-Román A, Sánchez-Pérez I, Abellán-Huerta J, Lozano Ruíz-Poveda F. Shockwave:Useful But Potentially Dangerous. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:500-501.

12. Jurado-Román A, Gonzálvez A, Galeote G, Jiménez-Valero S, Moreno R. RotaTripsy:Combination of Rotational Atherectomy and Intravascular Lithotripsy for the Treatment of Severely Calcified Lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e127-e129.

Corresponding author: Unidad de Cardiología Invasiva, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital La Luz, Maestro Ángel Llorca 8, 28003 Madrid, Spain.

E-mail address: ; (J. Palazuelos).

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

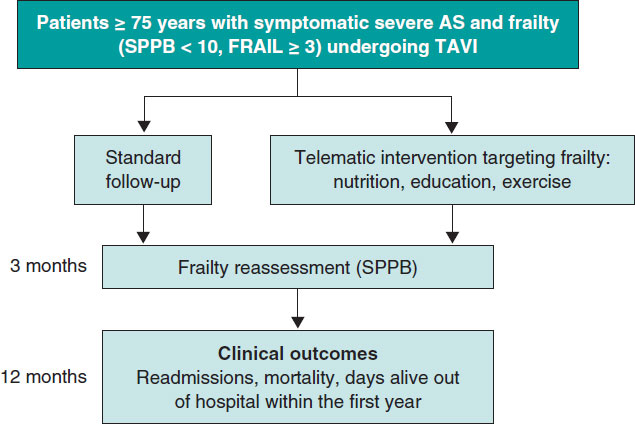

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España