Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: Could tell us what the prevalence of angina without obstructive coronary artery disease is in patients referred for invasive angiography and how has it evolved over the last few years?

ANSWER: Nearly half of the patients referred for cardiac catheterization due to suspected stable angina have coronary arteries without obstructive lesions.1 These numbers are even higher in the series of patients studied through cardiac computed tomography to the point that up to 3 out of 4 patients do not show any obstructive lesions. Women have a higher prevalence compared to men of up to 70%. Therefore, angina without obstructive lesions should not be considered a secondary problem, but a fundamental aspect of our routine clinical practice at the cath lab. Also, these patients have high rates of recurring angina and disability,2 which means that achieving the proper diagnosis and administering the right treatment is of paramount importance.

Q.: We have been using the expression «without obstructive coronary artery disease», but it can be put into context. Shouldn’t we rather say «without angiographically significant stenoses». Do you think that the physiological significance of stenoses with guidewire pressure should always be excluded, even the mild ones?

A.: With the evidence available, I believe that the systematic use of guidewire pressures to assess mild epicardial lesions is not justified. As a matter of fact, the correlation and concordance between angiography and fractional flow reserve (FFR) are modest, which is especially important in 50% to 90% stenoses where the angiography often overestimates functional severity systematically with rates of false positives > 50%.3 On the other side of the spectrum, stenotic lesions < 50% on the angiography have a relatively low risk of being ischemic on the FFR and are almost anecdotal if < 30%. In a study conducted with 139 patients with angina and without obstructive lesions, the frequency rate of lesions with FFR ≤ 0.8 was 5%.4 On the other hand, we should mention that the cut-off value validated to tag a coronary lesion as ischemic is 0.75 although, in practice, 0.8 is used to decide on whether to revascularize or not.

Regarding the clinical benefit of this approach, the large clinical trials that have proven the utility of FFR have only studied lesions > 50%, which is why we don’t have data supporting the clinical utility of assessing mild lesions.5,6 The RIPCORD-2 trial7 presented in the Congress held by the European Society of Cardiology back in September 2021 included patients with, at least, 1 stenotic lesion > 30%. All these patients’ vessels were studied using the FFR and no clinical benefit was found. What this means is that probably the greatest benefit of FFR is to avoid unnecessary revascularizations, and to clarify the significance of truly suspicious lesions.

In practice, I think that the best thing to do is to individualize the decision-making process considering the angiographic severity, location of the lesion, and quality of angiographic assessment. A 20% lesion in a diagonal branch and a 40% lesion in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery are 2 completely different things. Also, a focal lesion in a well-studied segment does not cast the same doubts as a long and calcified disease where a good angiographic assessment is not an easy thing to do due to curves, shortening, etc. Finally, we should remember that if a decision is made to measure microvascular function using a flow-pressure guidewire, the FFR can be established, almost at the same time, on suspicious lesions.

Q.: Once the significant stenosis of the epicardial vessel has been excluded, what should be the assessment protocol inside the cath lab?

A.: The invasive assessment of ischemia without obstructive lesions rests on 2 pillars mainly: the study of microcirculation, and the study of vascular reactivity.

The study of microcirculation consists of assessing coronary flow at rest and during maximum hyperemia. To this end, pressure and flow guidewires, whether thermodilution-based (PressureWire, Abbott, United States) or Doppler-based (Combowire, Philips, The Netherlands) are used. Baselines measures are taken, then maximum hyperemia is induced with adenosine to eventually take the same measures once again. This allows us to estimate the coronary flow reserve that is the ratio between hyperemic and baseline flow (which should be > 2). Coronary flow reserve < 2 means that, in situations of exercise or other stressors, the patient cannot duplicate his oxygen supply to the myocardium eventually, thus leading to ischemia easily. Added to flow coronary reserve, the combination of pressure and hyperemic flow, can also estimate microvascular resistance. The most widely used measure is the microvascular resistance index (considered pathological if > 25.)8

The second part is to assess vasoreactivity since coronary arteries do not necessarily respond to physiological stimuli the same way they do to adenosine. As a matter of fact, coronary flow and vascular tone both of epicardial artery and microcirculation largely depend on the production of nitric oxide by the endothelium. If this production does not properly work, paradoxical vasoconstriction can be seen in physiological situations that would require hyperemia. That is why it is important to assess coronary reactivity, preferably using the acetylcholine provocation testing. It allows us to discard the presence of vasospastic angina, and endothelial dysfunction. We have recently published an article on REC: Interventional Cardiology with a detailed description on how to run and then interpret an acetylcholine provocation testing.9

This approach based on microvascular function and on the acetylcholine provocation testing has been backed by a group of experts from the European Society of Cardiology.8 Regarding the logistics of the procedure, each lab should assess, depending on time availability, resources, and experience whether to perform the procedure ad hoc or whether to stage it, and arrange the order in which the tests will be run. We should bear in mind that, although the assessment of microcirculation requires the previous administration of nitroglycerin, the acetylcholine provocation testing requires just the opposite. Therefore, a possibility is to perform the angiography without nitroglycerin first, then the acetylcholine provocation testing, and finally measure the microvascular function. If nitroglycerin has been administered to achieve the diagnosis, the best thing to do is to measure the microvascular function next and leave the acetylcholine provocation testing for the end.

Q.: Is it possible to draw therapeutic implications from the comprehensive assessment of micro- and macrovascular coronary physiology?

A.: The main problem with microvascular and endothelial dysfunction is that no large clinical trial has ever confirmed any benefits regarding adverse events with any drugs. However, this should not take us to therapeutic nihilism because some former studies have proven the utility of different drugs reducing symptoms and improving quality of life.

If the patient is diagnosed with microvascular dysfunction, the first-line therapy here is beta-blockers. As coadjuvant or alternative therapy ivabradine, ranolazine, nicorandil, and calcium channel blockers can be used; nitroglycerin is not very useful here because it has a minor effect on microcirculation. Statins, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors are advised too for the primary prevention of events.

If endothelial dysfunction-induced vasoconstriction or vasospastic angina are predominant, beta-blockers are ill-advised since they can make things worse. In this case, the first-line therapy is calcium channel blockers, nitrates, and nicorandil. The use of statins, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors can be considered here too.

Empirical treatment has often been advised as an easier approach compared to physiological diagnosis and targeted therapy. Once again, each center should adapt its own clinical practice to its own possibilities. However, my own experience is that when these patients are not properly studied, they are not committed to the frequent visits that a careful empirical treatment would require; on the contrary, they are often discharged from the hospital and assessed at the 1-year follow-up, preventing us from conducting a proper follow-up of the symptoms and the effectiveness of treatment. On the other hand, considering that based on the physiological problem, there are very little effective treatments (like nitrates in microvascular dysfunction), and others are harmful (like beta-blockers in vasospasm), I think empirical treatment confront us with true dilemmas when treating patients who are not doing well.

Q.: What is the clinical evidence behind the invasive comprehensive assessment of coronary circulation? Have some advantages been identified regarding prognosis?

A.: Numerous studies from the 90s have proven that physiological disorders in patients with angina and without obstructive lesions are directly associated with myocardial ischemia and with long-term prognosis, as well as with the presence of atheromatous plaques and vulnerability data from intravascular imaging modalities. This is important because it is wrong to assume that all patients with angina and without lesions have the same disease and the same benign prognosis. Truth is that patients with endothelial and microvascular dysfunction have a far worse prognosis compared to patients with normal studies. Also, small trials have allowed us to establish the efficacy of different drugs based on the type of physiological dysfunction, as we have already discussed, thus supporting targeted therapy.

Regarding the prognostic benefit of individualized therapy, the CorMicA trial proved that this approach is superior to empirical treatment offering a better quality of life after 6 and 12 months.10 To this date, we are still lacking studies with large enough samples to detect benefits regarding the adverse events. The iCorMicA trial (clinicaltrials.gov. Identifier: NCT04674449), currently ongoing, will be recruiting 1500 patients to study the benefits in quality of life and adverse events. In any case, with the results of the ISCHEMIA trial in mind,11 I believe that only focusing on reducing hard events is a mistake that can prevent patients from receiving therapies that do help from the symptomatic and functional standpoint. In conclusion, I think there are enough scientific data to say that patients with angina and without obstructive lesions benefit from knowing their physiology and receiving individualized therapies.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author has received payments for training sessions organized by Abbott.

REFERENCES

1. Wang ZJ, Zhang LL, Elmariah S, Han HY, Zhou YJ. Prevalence and Prognosis of Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease in Patients Undergoing Coronary Angiography or Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:329-346.

2. Shaw LJ, Merz CNB, Pepine CJ, et al. The Economic Burden of Angina in Women With Suspected Ischemic Heart Disease:Results From the National Institutes of Health-National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-Sponsored Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation. 2006;114:894-904.

3. Park S-J, Kang S-J, Ahn J-M, et al. Visual-Functional Mismatch Between Coronary Angiography and Fractional Flow Reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1029-1036.

4. Lee BK, Lim HS, Fearon WF, et al. Invasive evaluation of patients with angina in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2015;131:1054-1060.

5. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213-224.

6. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991-1001.

7. Curzen N. RIPCORD 2:does routine pressure wire assessment influence management strategy of coronary angiography for diagnosis of chest pain?En:ESC Congress 2021. The Digital Experience;2021, 27-30 August. Available online:https://digital-congress.escardio.org/ESC-Congress/sessions/2835-hot-line-ripcord-2. Consultado 4 Sep 2021.

8. Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology &Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-3520.

9. Gutiérrez E, Gomez-Lara J, Escaned J, et al. Valoración de la función endotelial y provocación de vasoespasmo coronario mediante infusión intracoronaria de acetilcolina. Documento técnico del Grupo de Trabajo de diagnóstico intracoronario de la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECIC.M21000211

10. Ford TJ, Stanley B, Sidik N, et al. 1-Year Outcomes of Angina Management Guided by Invasive Coronary Function Testing (CorMicA). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:33-45.

11. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

QUESTION: Is there a specific profile of patients with angina and without obstructive coronary artery disease?

ANSWER: Although we have been paying more attention to angina without obstructive coronary artery disease over the last few years (a more truthful denomination compared to ischemia with normal coronary arteries because it focuses on the clinical problem and also because many patients don’t have strictly normal coronary arteries) we still don’t know much about this syndrome. Syndrome X was the term coined back in 1973 after the group of patients with normal coronary arteries that was called group X.1 Actually this term is more appropriate since this is the letter used in algebra to represent something that remains unknown.

Answering your question, it is more common in women; it is often exertional although a different kind of pattern has been reported too (first effort, at rest during certain hours, especially at night-time, exertional dyspnea); also, it is associated with known cardiovascular risk factors since most patients with angina and without obstructive coronary artery disease have coronary atherosclerosis.2 Obesity, the association with inflammatory diseases (such as systemic lupus erythematous), mood swings, intolerance to different drugs are not rare, and make us have to try several combinations to control de symptoms.

Although it seems reasonable to suspect that a patient with angina may not have coronary artery lesions justifying the symptoms, these patients’ profile is somehow similar to that of patients with clinically significant coronary artery lesions. Only an imaging modality capable of discarding clinically significant coronary artery disease can lead to a definitive diagnosis of angina without obstructive coronary artery disease.

Q.: The diagnosis of type of angina is, by definition, achieved after performing an invasive coronary angiography, but since the use of the computed tomography (CT) scan for coronary artery assessment has become more popular, can it also be diagnosed with a non-invasive angiography with a CT scan?

A.: To achieve the diagnosis of angina without obstructive coronary artery disease the following requirements need to be met:3 a) compatible symptoms, b) lack of obstructive coronary artery disease, c) myocardial ischemia, and d) microvascular dysfunction. Therefore, if microvascular dysfunction is not confirmed, the diagnosis cannot be achieved. To answer this question properly we should ask ourselves a couple more questions first: can we diagnose microvascular dysfunction with non-invasive imaging modalities including the CT scan? also, can we achieve the diagnosis only with the clinical signs and proof that there is no obstructive coronary artery disease?

The diagnosis of microvascular dysfunction with non-invasive imaging modalities is feasible, although these are expensive or have been insufficiently validated. Positron emission tomography4 and magnetic resonance imaging5 have been able to confirm the presence of microvascular dysfunction in patients without macrovascular disease in different clinical settings. Contrast echocardiography6 and Doppler echocardiography of the left anterior descending coronary artery7 have also yielded favorable results in this context, but they are barely used.

Although it does not seem right to achieve the diagnosis without prior confirmation of microvascular dysfunction, it can be reasonable under certain circumstances. If the patient has typical symptoms and cardiovascular risk factors, treatment can be initiated after discarding obstructive coronary artery disease with a CT scan. If symptoms cannot be controlled, we can turn to the invasive study of microvascular function. This can be the go-to strategy in elderly or frail patients or with severe noncardiac diseases. It can even be used for the rest of patients since delaying symptom control does not compromise or worsen prognosis.

Q.: In the presence of mild or moderate stenoses on the CT scan, do you think that a non-invasive assessment of ischemia can help?

A.: Theoretically speaking, as I have already mentioned, we need confirmation of myocardial ischemia to achieve a definitive diagnosis of microvascular disease. There are situations, however, when we can assume the diagnosis if the patient shows typical symptoms and obstructive coronary artery disease has been discarded.

In patients with CT scans showing non-severe coronary artery lesions, we need to make sure that these lesions are not functionally significant before accepting the diagnosis of microvascular disease. The milder the lesion, the more certain we’ll be that it is a non-functionally significant lesion, but microvascular dysfunction. Therefore, in moderate lesions, functional assessments are necessary to discard functionally significant disease. This assessment can be made while the CT scan is being performed by assessing coronary flow reserve8 or with functional tests to see if there are traces of ischemia, and whether these traces originate at the diseased artery.

In any case, to me this question looks more like an academic issue than a practical one. If a patient has angina pectoris, a positive functional test for ischemia, a CT scan showing moderate disease of a coronary artery, and no left main coronary artery disease, medical therapy can be initiated, and the evolution of symptoms assessed. That is so because prognosis is not much better with an invasive approach as the ISCHEMIA trial proved.9

Q.: There are times when, depending on the center, the clinician can find himself with a symptomatic patient for angina who has been diagnosed with lack of coronary stenoses without even an invasive study of coronary physiology. What would the role of non-invasive imaging modalities be here?

A.: That is correct, a few years ago that was the rule of thumb: coronary artery disease was discarded, and there was no need to assess the vascular function. Currently, cardiologists are more aware of its importance, in part due to the interest shown by interventional cardiologists in this disease. Even so, we still see patients with angina pectoris in whom obstructive epicardial vessel disease has been discarded, but endothelium-related o non-related vascular dysfunction hasn’t.

A positive ischemia assessment testing supports the diagnosis of microvascular dysfunction and, even in the absence of an invasive study of coronary physiology, it is good enough to initiate therapy. But if the patient does not get any better with the treatment suggested the invasive assessment of coronary physiology will be necessary to direct therapy towards the specific origin that’s causing the coronary disorder.

Q.: What specific medical therapies are optimal based on the profile of coronary micro- and macrovascular pathophysiology?

A.: Evidence-based recommendations are very scarce. In the first place, cardiovascular risk factors should be put under control adequately, especially hypertension and diabetes mellitus, both of which contribute to vascular disease. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and statins have proven effective to treat these patients. Controlling weight is essential, and a cardiac rehabilitation program can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life.

All types of antianginal drugs can be used in these patients, many times using a trial-and-error approach to it, because patients may be intolerant or drugs ineffective.

To choose the optimal drug therapy we should make a distinction between 2 different profiles of patients with angina pectoris without obstructive coronary artery disease: those with vasospastic angina pectoris and those with microvascular angina pectoris.

Patients with micro- or macrovascular spasm benefit from calcium channel blockers. Both dihydropyridine and non-dihydropyridine drugs can be effective, and the lack of effectiveness of one does not predict a lack of effectiveness of the other. Also, nitrates, both oral an in patches, can be used in this context.

In patients with microvascular angina pectoris not due to vasospasm, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, ranolazine, aminophylline, and trimetazidine have given effective results in preliminary trials, but not yet in randomized clinical trials. Although nitrates can be used in this type of patients, it has been proposed that symptoms could become worse.

Finally, antianginal drugs without significant hemodynamic effects can minimize symptoms in both groups of patients, especially ranolazine and trimetazidine.

Q.: With this therapeutic individualization, have any advantages been identified regarding prognosis?

A.: No beneficial effects have been confirmed regarding prognosis in mortality or myocardial infarction. However, fewer events of angina pectoris have been reported leading to a better quality of life, which is essential in these patients. The CorMicA trial10 confirmed that an invasive study of coronary physiology in patients with chest pain and without obstructive coronary artery disease could identify 3 different groups (vasospastic angina pectoris, microvascular angina pectoris, and noncardiac chest pain). Also, that a specific medical strategy for each specific group reduced the occurrence of angina pectoris.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Arbogast R, Bourassa MG. Myocardial function during atrial pacing in patients with angina pectoris and normal coronary arteriograms. Comparison with patients having significant coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1973;32:257-263.

2. Lee BK, Lim HS, Fearon WF, et al. Invasive evaluation of patients with angina in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2015;131:1054-1060.

3. Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology &Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-3520.

4. Di Carli MF, Charytan D, McMahon GT, Ganz P, Dorbala S, Schelbert HR. Coronary circulatory function in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1369-1377.

5. Panting JR, Gatehouse PD, Yang GZ, et al. Abnormal subendocardial perfusion in cardiac syndrome X detected by cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1948-1953.

6. Caiati C, Montaldo C, Zedda N, et al. Validation of a new noninvasive method (contrast-enhanced transthoracic second harmonic echo Doppler) for the evaluation of coronary flow reserve:comparison with intracoronary Doppler flow wire. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1193-1200.

7. Hildick-Smith DJ, Maryan R, Shapiro LM. Assessment of coronary flow reserve by adenosine transthoracic echocardiography:validation with intracoronary Doppler. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:984-990.

8. Khav N, Ihdayhid AR, Ko B. CT-Derived Fractional Flow Reserve (CT-FFR) in the Evaluation of Coronary Artery Disease. Heart Lung Circ. 2020;29:1621-1632.

9. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al.;ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

10. Ford TJ, Stanley B, Good R, et al. Stratified Medical Therapy Using Invasive Coronary Function Testing in Angina:The CorMicA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2841-2855.

QUESTION: For starters, what is the minimalist approach to transcatether aortic valve implantation (TAVI)?

ANSWER: After the first case described by Cribier et al.1 back in 2002, the management of aortic stenosis through TAVI has consolidated and become a safe and effective therapy that is based on a well-established and standardized procedure. Although it is a complex procedure due to the characteristics of patients and devices and the fact that experienced operators are needed, the growing number of cases reported, and the technological advances made with the devices have improved processes and reduced complications significantly. This has prompted that, over the last few years, certain experienced groups2 have modified certain steps of the procedure and introduced strategies before and after the intervention to simplify and make TAVI more efficient. Also, to promote faster recoveries in the patients. This set of modifications is described as minimalist approach to TAVI. Two of the most significant aspects here are suppressing balloon dilatation and reducing hospital stays. However, there are simplifying strategies that can be divided into 3 parts: previous assessment and case analysis, valve implantation, and postoperative care. During the previous assessment part, the objective is to speed up the study circuits of the patients and reduce the waiting lists. Also, the decision between surgery or TAVI should not be made on the surgical risk but on the risk-benefit ratio based on the patient’s age, comorbidities, functional status, frailty, anatomical characteristics, family support, and on the experience and results of the treating center. Regarding valve implantation, the simplifying strategies are applied in different settings:

-

– Healthcare professionals and setting. Procedures can be performed in a cath lab by experienced interventional cardiologists. In cases of transfemoral access, the heart team often includes 2 interventional cardiologists, 2 nurses, and 1 patient care technician. The nurse or the technician is in charge of preparing the device. The presence of 1 anesthesiologist and 1 expert cardiologist in imaging modalities or 1 echocardiographist is advised. With highly selected patients—complex access sites or different from the femoral access, etc.—or if certain complications occur the collaboration of a cardiovascular surgeon may be required.

-

– Anesthesia. It is one of the main changes of this minimalist approach. Although the presence of an anesthesiologist during the procedure is advised, general anesthesia is often substituted for local anesthesia and sedation. This avoids intubation and ventilation, minimizes risks, and reduces the hospital stay. General anesthesia would be spared for patients of a higher risk of complications who cannot tolerate the procedure or with high chances of conversion to surgery.

-

– Arterial access. In the primary access, the femoral access is often the one used for valve implantation and has given the best results of all. However, there are other alternatives available when it is not feasible. Puncture should be angiography- or ultrasound-guided and percutaneous closure is often performed with devices like Prostar (Abbott Vascular, United States), Perclose Proglide (Abbott Vascular, United States) or Manta (Teleflex, United States). Although the femoral access site is the preferred one in some cases for a direct control of hemostasis, with these devices, percutaneous puncture is a less invasive option that has good results. Regarding secondary arterial access, another arterial access site is often required, usually the contralateral femoral artery, for pigtail catheter insertion to perform the aortography. When inserted into the non-coronary sinus it serves as the reference for implantation. This access site also allows us to advance the protection guidewire inside the artery through which the access occurs in such a way that, if vascular closure is incomplete or fails, on top of providing compression, a balloon can be advanced to occlude the flow and a covered stent can be implanted. To this point, everal minimalist approaches have been suggested: a) use the radial access as the secondary access; b) simplify it by performing a more distal puncture preferably in the common femoral artery 2 cm further down or in the superficial femoral artery. Through 4-Fr or 5-Fr introducer sheath a protection guidewire would be advanced to perform selective injections, and c) with the smaller size of today’s sheath some even suggest inserting a protection guidewire.

-

– Echocardiogram. Using transthoracic echocardiography during implantation is considered enough because it avoids the problems associated with the transesophageal echocardiogram and allows us to assess fundamental aspects such as LV contractility, the position of the guidewire, and the outcome of valve implantation. Also, complications like cardiac tamponade, aortic regurgitation, etc can be discarded.

-

– Transient pacemaker. Rapid ventricular pacing is required for balloon-expandable valve and certain self-expandable valve implantation. Balloon-tipped electrode catheters should be used to reduce the risk of perforation. To avoid the problems associated with catheterizing that venous route, a metal guidewire placed in the left ventricle can be used for pacing purposes. After placing a subcutaneous 22G needle close to the sheath, the clips are connected to the needle (positive) and the ventricle metal guidewire (negative) isolated with a catheter or a valve placed close to the annulus. If there is no AV block (transient or permanent) or QRS widening > 160 m the pacemaker is removed in the cath lab after analyzing the electrocardiogram. If a definitive pacemaker is required, it should be implanted within the next 72 hours to avoid unnecessary longer the hospital stays.

-

– Avoid balloon predilatation. With some of the new valves available it is possible to perform direct valve implantation, thus reducing the risks derived from aortic valvuloplasty.

-

– Avoid urinary catheterization. It reduces hospital complications—infections, hematuria—and the hospital stay.

Regarding the third part, postoperative care, it is necessary to monitor the patient closely within the first few hours by closely assessing his hemodynamic status and the vascular access routes. Follow-up blood tests should be performed to detect blood losses. Also, the heart rhythm should be monitored to rule out the presence of cardiac conduction disorders or new-onset arrhythmias. A control echocardiogram is required the next day and, in the absence of complications, the patient should regain mobilization soon.

Q.: What advantages does deep sedation have over general anesthesia and how do you think it should be performed?

A.: The presence of an anesthesiologist in the cath lab guarantees closer monitoring and brings comfort to the patient. It also speeds up the procedure in case of complications. This does not necessarily imply using general anesthesia in every case: the use of conscious sedation and local anesthesia allows us to avoid orotracheal intubation, brings greater hemodynamic stability, and shorter procedural and recovery times. Several studies have proven the safety profile of this type of sedation with similar rates of mortality and complications;3,4 its use has become very popular over the last few years. For example, in France,5 it was used in 30% of the cases in 2010 up to 70% in 2017. Therefore, general anesthesia would be spared for patients with hemodynamic instability and higher risk of complications who don’t tolerate the procedure or have high chances of conversion to surgery.

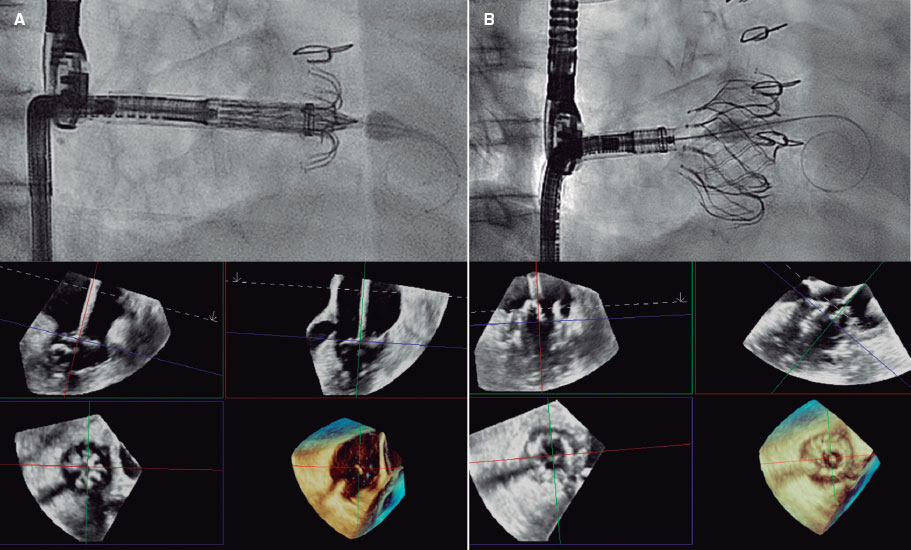

Q.: How is echocardiographic imaging implemented during TAVI? Always or occasionally? Transthoracic or transesophageal?

A.: Having a cardiologist expert in cardiac imaging modalities performing monitorization tasks through transthoracic echocardiogram brings extra safety, and avoids the problems associated with the transesophageal echocardiogram. This expert can control the position of the guidewire inside the ventricle, confirm the results of implantation by assessing gradients, identify some degrees of aortic regurgitation, and detect rapidly possible complications that may occur like abnormalities in cardiac contractility or the appearance of pericardial effusion. Transesophageal echocardiogram would be spared for cases of poor acoustic window or specific needs.

Q.: There are very different vascular occlusion systems available. Are there significant differences to pick one over the other based on certain characteristics of the patient? Which are the preferences of your heart team?

A.: Different suture-mediated closure devices (Proglide, Prostar) or collagen-based devices (Manta)6,7 can be used with good results. Some may be used based on the preferences or experience of the heart team since the comparative studies conducted so far do not make any clear differences on this regard. Suture-mediated closure devices may have more problems in femoral arteries with calcium deposits while the Manta collagen-based devices can present complications in small-caliber femoral arteries (< 6 mm) or in very obese patients. Also, we should take into consideration the cost of each one of these devices, and the necessary learning curves. The single or double Proglide device is the most widely used. As a matter of fact, the latter is the common strategy in our center. None of them is infallible and in the presence of bleeding a balloon is required for occlusion purposes and even covered stent graft implantation to contain the bleeding.

Q.: Which is the average hospital stay after TAVI at your center? What do you think of 24 to 48-hour early hospital discharges?

A.: In our center, the average hospital stay is between 3 and 4 days because, although we try to discharge the patients 48 hours after the procedure, their risk profile often requires longer hospital stays. The patient should regain mobility within a few hours if the transient pacemaker has been removed and there are no vascular access complications. Therefore, uncomplicated patients can be discharged in < 72 hours. This early hospital discharge has proven feasible and safe in different studies and even in 1 meta-analysis that confirmed the good results of discharging patients within 3 days.8 Next-day faster hospital discharges are also possible in highly selected patients without procedural complications.9 However, a reason for concern in these patients is the possibility of developing AV block, and the need for pacemaker implantation. Although 50% of cardiac conduction disorders occur during implantation, 44% of them occur within the next 3 days.10 If the 24-hour discharge is decided, it should be performed with a protocol of electrocardiographic monitoring and early detection of patients requiring pacemaker.11

Q.: Finally, in your own opinion, what patients would be eligible for minimalist TAVI and when is it ill-advised?

A.: It is going to depend on how experienced the heart team is, on the characteristics of the hospital, and on the situation of the patient always taking into consideration that the primary endpoint here is the safety and effectiveness of the procedure. The minimalist approach is a reasonable option in hemodynamically stable patients with adequate femoral accesses, collaborators, and without additional problems involving a high risk of complications like coronary occlusion. It will be gradually implemented, yet the effectiveness and quality of healthcare should not be compromised. Instead, the procedures should be performed faster, better, and adapted to the needs of the patients to avoid unnecessary tests, maneuvers, and stays.

FUNDING

None reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported

REFERENCES

1. Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous Transcatheter Implantation of an Aortic Valve Prosthesis for Calcific Aortic Stenosis First Human Case Description. Circulation 2002;106:3006-3008.

2. Lauck SB, Wood DA, Baumbusch J, et al. Vancouver Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Clinical Pathway:Minimalist Approach, Standardized Care, and Discharge Criteria to Reduce Length of Stay. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:312-321.

3. Ehret C, Rossaint R, Foldenauer AC, et al. Is local anaesthesia a favourable approach for transcatheter aortic valve implantation?A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing local and general anaesthesia. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e016321.

4. Harjai KJ, Bules T, Berger A, et al. Efficiency, Safety, and Quality of Life After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Performed With Moderate Sedation Versus General Anesthesia. Am J Cardiol. 2020;125:1088-1095.

5. Oguri A, Yamamoto M, Mouillet G, et al. FRANCE 2 Registry Investigators. Clinical outcomes and safety of transfemoral aortic valve implantation under general versus local anesthesia:subanalysis of the French Aortic National CoreValve and Edwards 2 registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:602-610.

6. Mehilli J, Jochheim D, Abdel-Wahab M, et al. One-year outcomes with two suture-mediated closure devices to achieve access-site haemostasis following transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:1298-1304.

7. De Palma R, Settergren M, Rück A, et al. Impact of percutaneous femoral arteriotomy closure using the MANTATM device on vascular and bleeding complications after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:954-961.

8. Kotronias RA, Teitelbaum M, Webb JG, et al. Early Versus Standard Discharge After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1759-1771.

9. Kamioka N, Wells J, Keegan P, et al. Predictors and clinical outcomes of next-day discharge after minimalist transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:107-115.

10. Bagur R, Rodés-Cabau J, Gurvitch R, et al. Need for permanent pacemaker as a complication of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and surgical aortic valve replacement in elderly patients with severe aortic stenosis and similar baseline electrocardiographic findings. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:540-551.

11. Naveh S, Perlman GY, Elitsur Y, et al. Electrocardiographic predictors of long-term cardiac pacing dependency following transcatheter aortic valve implantation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2017;28:216-223.

QUESTION: For starters, what is the minimalist approach to transcatether aortic valve implantation (TAVI)?

ANSWER: Minimalist TAVI is a recent strategy to simplify the procedure, reduce possible complications, and favor early hospital discharges. This general definition can be explained by 2 keys aspects: what measures should be taken? And what patients should be eligible? Replacing general anesthesia and orotracheal intubation for sedation and local anesthesia are some of these measures. Sedation with the use of a laryngeal mask airway waking up the patient once the procedure is done is an intermediate situation. The type of hospital stay following TAVI is also an important aspect to be considered and it is associated with the type of anesthesia or sedation used: intensive care unit, post-anesthesia care unit or the hospital cardiac care unit. Other minimalist approaches during the procedure would be the access site used and the percutaneous closure, to avoid bladder catheterization, use the femoral venous access, use the radial, and not the femoral, artery for monitorization purposes, and to avoid the transesophageal echocardiogram. After the implantation, promoting early walking and removing IVs as soon as possible may also help. All these measures facilitate early hospital discharges. However, the hospital stays following these minimalist measures vary in the series published. In the first series ever published,1 the average stay was 3 days including the intensive care unit stay. Recent series2 report next-day hospital discharges for patients without complications within the first 24 hours. Finally, in the pandemic era of COVID-19 even same-day hospital discharges have sometimes been proposed.3

The other key aspect we should analyze is what patients should be eligible for minimalist TAVI, something we will talk about later.

Q.: What advantages does general anesthesia have to offer and what is patient profile is the most eligible of all?

A.: The way I see it, general anesthesia is beneficial for 2 reasons mainly. The first one is that the patient will remain still for the entire procedure, which is very convenient because precision is required when moving and placing the catheters. The second one is that, in case of hemodynamic instability or serious complications, we have one healthcare professional available, the anesthesiologist, in charge of the patient’s ventilation and vital signs. This liberates the operator who can devote himself to the implantation technique alone or to solve any of the complications that may have occurred. Still, some issues still need further clarification: first, the difference between general anesthesia and sedation. In non-intubated patients, superficial general anesthesia or deep sedation can be used. These are very similar techniques with some very similar aspects that overlap. The use of the laryngeal mask airway provides versatility to adequate sedation or anesthesia for each case in particular. The anesthesiologist is free to use the technique he likes the most with one condition only, that the patient needs to «come in awake and leave the same way». Most times, laryngeal mask airways are used. They are often removed after implantation to refer the patient to the post-anesthesia care unit while awake and with spontaneous breathing. He will remain in this unit for 2 to 4 hours. Then, he will be transferred to the hospital cardiac care unit for electrocardiographic monitoring. The second aspect to be considered is the availability of the anesthesiologist. Sedation without anesthesia gives more versatility while setting everything up at the cath lab and facilitates the performance of more TAVIs regardless of the anesthesiologist’s days available. However, the drawback is that sedation is not that perfect and, in case of hemodynamic instability during the procedure, the operators will have to do 2 things: stabilize the situation, and then proceed with the implantation. Our experience is that having an anesthesiologist available is beneficial because he can provide «a la carte» sedation or anesthesia without extending the hospital stay. Also, the patient is back to the hospital cardiac care unit within a few hours.

Q.: Do you think the transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) brings added value to TAVI? In what cases would it be more indicated during the procedure?

A.: TEE was often used when this technique was born to measure the aortic annulus when the process of sizing the valve was not as standardized as it is today. The computed tomography analyzed by current software provides all kinds of measurements including diameters, perimeters, and areas allowing an accurate selection of the device and leaving the indication for TEE obsolete. Another utility of TEE during the procedure is for the early detection of complications. In patients with severe hemodynamic impairment, it facilitates the differential diagnosis of the complication immediately. Therefore, cardiac tamponade, severe ventricular dysfunction, and severe mitral or aortic regurgitation can be identified early, which in turn facilitates the rapid adoption of the necessary measures. Thrombi and aortic damage are other complications that can also be detected with this imaging modality. To this date, except for the early detection of complications, the TEE does not seem of great utility during the procedure. Since complications are rare and difficult to predict, the systematic use of TEE has been losing interest. This, added to the requirement for endotracheal intubation and longer procedural and hospital stay times4 has put its elective use to an end in most cath labs. The transthoracic echocardiography provides enough information for the decision-making process. Also, in selected cases informs of major complications like severe mitral regurgitation or aortic annulus rupture, the TEE can be used.

Q.: Vascular occlusion systems have variable, yet constant, rates of failure and complications. Do you think there are still indications for minimal access surgery? Where does your heart team stand regarding valvular accesses?

A.: I think there are no indications for minimal access surgery regarding the femoral access. Computed tomography or ultrasound-guided punctures are often used as well as percutaneous closures. Although the latter have some rate of failure, covered stent implantation from the contralateral femoral region would solve most vascular access problems. Femoral surgery is often spared for catastrophic situations only when the problem simply cannot be solved percutaneously. Therefore, from 2019 to this date, 32 failures (13%) have been reported from of a total of 239 cases regarding closures with the suture device that resolved after covered stent implantation from the contralateral femoral region. Also, only in 1 case (0.4%) emergency surgery was required. If possible, our option should always be the femoral access that, as I already said, has always been percutaneous. Elective minimal access surgery has only been used in other access routes different from the femoral one; in our own experience, it has been the subclavian access in patients with severe disease at the femoral iliac territory. Although the percutaneous approach has been described through this access route,5 we are not as experienced with it since most TAVIs can be performed percutaneously via femoral access. Other access routes that require surgery are the transcarotid and the transaortic ones, but we don’t have any experience at all here.

Q.: Regarding patients discharged after TAVI, what is the common practice at your center and what would you recommend?

A.: Ambulatory care patients without femoral complications or conduction disorders find themselves walking the next day. A transthoracic echocardiography is performed after 24-48 hours, and they are often discharged after 2 days. The causes that can delay hospital discharge are severe heart failure prior to TAVI, access site complications (whether homolateral or contralateral), the presence of fever, kidney failure, and conduction disorders. In the latter, delaying the hospital discharge is due to the decision on whether to implant a definitive pacemaker or keep the patient hospitalized while waiting for a definitive resolution of the possible intermittent disorders. A panel of experts has proposed 5 different algorithms depending on the type of conduction defect reported in baseline conditions and after the procedure.6 The goal is to standardize both the indications for definitive pacemaker implantation and the monitorization time necessary for the decision-making process. Thus, the decision to implant a definitive pacemaker cannot be made within the first 24-hours in most patients. My recommendation on hospital discharge following TAVI is to simplify procedure and convalescence as much as possible and try hospital discharge after 48 hours. When the aforementioned complications occur, the right thing to do is wait until they are solved. The algorithms mentioned6 are useful to make the decision, as soon as possible, on whether to implant a definitive pacemaker or not.

Q.: Finally, in your own opinion, what patients would be eligible for minimalist TAVI and when is it ill-advised?

A.: Although the Vancouver 3M7 criteria are wide enough to include patients in the minimalist approach to TAVI I think it should only be eligible for patients scheduled for TAVI without severe heart failure with good femoral access, no kidney failure or respiratory failure or anemia. However, it would be ill-advised in hospitalized patients with heart failure and hemodynamic instability, depressed ejection fraction or who don’t meet the aforementioned criteria. In patients with previous conduction disorders, the algorithms proposed by the panel of experts should be followed.6 As I have already said, in the presence of complications, the minimal approach to TAVI strategy should be changed and hospital discharged delayed until the complication has resolved, and the patient has fully recovered. In this context, as Albert Einstein used to say: «everything should be made as simple as possible, but no simpler».

FUNDING

None reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Babaliaros V, Devireddy C, Lerakis S, et al. Comparison of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement performed in the catheterization laboratory (minimalist approach) versus hybrid operating room (standard approach):outcomes and cost analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:898-904.

2. Kamioka N, Wells J, Keegan P, et al. Predictors and Clinical Outcomes of Next-Day Discharge After Minimalist Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:107-115.

3. Perdoncin E, Greenbaum AB, Grubb KJ, et al. Safety of same-day discharge after uncomplicated, minimalist transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the COVID-19 era. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:940-947.

4. Bhatnagar UB, Gedela M, Sethi P, et al. Outcomes and Safety of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation With and Without Routine Use of Transesophageal Echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122:1210-1214.

5. Amat-Santos IJ, Santos-Martínez S, Conradi L, et al. Transaxillary transcatheter ACURATE neo aortic valve implantation —The TRANSAX multicenter study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/ccd.29423.

6. Rodés-Cabau J, Ellenbogen KA, Krahn AD, et al. Management of Conduction Disturbances Associated With Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1086-1106.

7. Wood DA, Lauck SB, Cairns JA, et al. The Vancouver 3M (Multidisciplinary, Multimodality, But Minimalist) Clinical Pathway Facilitates Safe Next-Day Discharge Home at Low-, Medium-, and High-Volume Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Centers:The 3M TAVR Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:459-469.

QUESTION: What is the current status of percutaneous coronary interventions to treat functional mitral regurgitation (MR)?

ANSWER: Functional MR is one of the clinical conditions within cardiology that have experienced more changes over the last few years. Currently, not only the best way to treat it is under study including contributions from percutaneous techniques, but also its very definition is under review. Initially, cut-off values used to be selected to define its severity that were different from those of primary MR based on the results from longitudinal studies in populations that had suffered myocardial infarctions.1 However, it has not been easy to confirm that by using these diagnostic thresholds, the therapeutic procedures yield consistent benefits.2,3 As a matter of fact, to this date, it is recommended to use the same criteria as with primary MR (effective regurgitant orifice area ≥ 0.4 cm2 and regurgitant volume ≥ 60 mL).

Another issue under discussion is whether the best therapeutic strategy is valve repair or replacement. Most clinical trials have studied the easiest repair strategy, that is, restrictive annuloplasty. It consists of annular remodeling with a rigid or semirigid annulus that is 1 or 2 sizes smaller than the patient’s valve (usually determined by the intertrigonal distance or the anterior leaflet surface area). Despite the criticism received for the methodology used in the repair group and the results obtained after the procedure, several clinical trials conducted in the United States have shown no clear benefits of mitral valve repair over mitral valve replacement. However, a lower rate of MR has been reported in the group treated with valves.4,5 Several authors suggest that this repair method is not the best one, especially if the etiology is ischemic and considering that myocardial damage and remodeling—the true culprit of valve disease—is often localized and highly variable.

My opinion is that this field has finally entered the adult age. It seems obvious that there is not an easy way to treat all patients. Also, that success depends on the right selection of patients and techniques including, in particular, the use of techniques for the subvalvular apparatus like repositioning or papillary muscle sling. Secondary MR is a ventricular disease; this is what we all say, but most surgeons and cardiologists still try to solve it by only acting on the valve alone.

Q.: Which are the most suitable techniques today to repair mitral valves with organ failure?

A.: The best way to treat primary MR is surgical valve repair when possible. Such is the case of almost all patients with myxoid degeneration treated in experienced centers. Also, it is the therapy of choice to treat other etiologies such as endocarditis and rheumatic disease. However, the repair rate is lower and depends on lesions associated with the valve and in the remaining structures.

The association between primary MR repair and the experience of the treating center is well known.6 However, this experience is hard to gain; up to 50% of the patients who are eligible for valve repair keep are actually treated with valve replacements.7 This opens the debate of whether patients should follow specific patterns of referral to centers experienced on mitral valve repair to guarantee optimal results, especially young patients and during the early stages of disease (asymptomatic, in sinus rhythm, and with a normal left ventricle) as the current clinical practice guidelines recommend.8,9

Q.: Are there good surgical options to treat mitral annular calcification?

A.: Annular calcification is relatively common in rheumatic disease and in advanced cases of myxoid degeneration and, in general, does not pose a significant problem. However, a minority of patients show very extensive calcification of the valvular annulus with deep infiltration and spread towards the ventricular myocardial tissue. These cases pose a problem not easy to solve. Incomplete annular decalcification leads to fewer chances of achieving successful repairs and a higher risk of suboptimal results regardless of the technique used: associated residual MR and stenosis in the case of mitral repair or paravalvular leaks and insufficient valvular size in valvular replacement.

The solution to this problem is performing extensive decalcification, which is a complex procedure with associated risks. It often involves the aggressive debridement of the posterior atrioventricular sulcus and further reconstruction with some type of reinforcement material (autologous or heterologous pericardium or synthetic tissues like Dacron). This type of reconstruction requires the proper selection of patients and a very precise technique since its main complication—the tear of the posterior sulcus—is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.

An interesting option recently presented although with scarce information on the mid-term results is a combination of a minimally invasive approach to prepare the valve followed by implantation under direct vision of an expandable valve, which optimizes valve fixation and avoids left ventricular outflow tract obstruction.

Q.: What is your opinion on less invasive surgical techniques to treat MR?

A.: I think that today they are the method of choice to surgically treat mitral valves because the benefits are obvious. We recently published our own experience on the management of mitral prolapse with a successful repair rate (98%) and a perioperative mortality rate < 1% in Revista Española de Cardiología.10 Minimally invasive thoracoscopic surgery was our preferred approach (more than 70% of the cases over the last few years) and is associated with less need for mechanical ventilation, shorter ICU stays, less blood loss, and less need for valve replacement at the 5-year follow-up (100% vs 95%).

Back in November 2019 we started our own robotic surgery program, the only one in Spain, with the Da Vinci system (Intuitive Surgical, United States), which basically focuses on mitral repair. By the time we were writing these lines, we had already treated 50 patients with very satisfactory results. In our early experience we think that the procedure is even less aggressive than thoracoscopy and is associated with further reductions of postoperative stays (median, 4 days).

There is no doubt in my mind that these minimally invasive techniques will keep growing and refining, and more patients will end up benefiting from repair surgeries less aggressively and with faster recovery times. Over the next few years, new robotic surgical platforms will be born for clinical use. Also, there will be new options for transapical neochord implantation without extracorporeal circulation. These advances will widen our current therapeutic armamentarium and join percutaneous techniques as part of our repertoire.

Q.: Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is a complex condition of often unsatisfactory management. What does surgery have to offer these days and to who?

A.: TR has gradually been gaining the attention it deserves. One of the most important changes over the last few years is the confirmation of how important the early, prophylactic treatment actually is even when there is no left-sided valve disease when the procedure is performed.8,9 This adds to the recognition of the need to treat severe primary TR in isolation in patients with symptoms of right-sided heart failure and in asymptomatic patients with progressive right ventricular deterioration.9

Same as it happens with secondary MR, the management of functional TR requires understanding right ventricular remodeling and other associated nonvalvular lesions. Secondary TR has been treated with surgery too often and in a superficial way without the same level of attention and detail paid to left-sided valve disease. Same as it happens with mitral valve repair, the management of secondary TR requires a high level of training and experience. The results of valve repair are excellent in the landmark centers, and sometimes the use of additional techniques is required on the leaflets (anterior leaflet repair with patch augmentation), the subvalvular apparatus (papillary muscle repositioning, chordal shortening or transposition or neochordal implantation), the right ventricle (free-wall and annular plication), and the right atrium. These less traditional techniques allow us to bring the benefits of repair to cases of very advanced functional TR, primary etiologies and, in the case of secondary TR, to repair the damage caused by device wiring or thoracic traumas. A good example of these more complex and advanced procedures is the Da Silva’s cone repair technique in adult patients with Ebstein’s anomaly.11

Isolated tricuspid valve or concomitant to mitral surgery can also be treated through minimally invasive and robotic thoracoscopic surgery in experienced centers in most of the patients. The concomitant ablation of atrial fibrillation can follow too.

Q.: What does the future of interventional cardiology have in store with respect to heart surgery? Where should we look into from one specialty and the other?

A.: I personally see a bright future ahead for the patients (which is the most important thing of all), cardiovascular surgeons, and interventional cardiologists. The magnitude of these improvements and how fast they will spread out will depend on our capacity to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to coordinate ourselves and collaborate with one another.

My opinion is that surgery needs to move towards perfecting training regarding valvular repair and minimally invasive techniques so that more patients can benefit from the better options available. The current low rates of valve repair in the management of mitral valve disease simply cannot stand. Together with cardiology we need to reflect on the current patterns of patient referral and look for formulas so patients can be operated on (whether surgically or percutaneously) in experienced centers. Also, patients need to gain access to all therapeutic options, and all the techniques available should be performed with optimal results based on scientific evidence, auditing, and the public disclosure of results.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

D. Pereda is a proctor for minimally invasive surgery for Edwards Lifesciences.

REFERENCES

1. Grigioni F, Enriquez-Sarano M, Zehr KJ, Bailey KR, Tajik AJ. Ischemic mitral regurgitation:long-term outcome and prognostic implications with quantitative Doppler assessment. Circulation. 2001;103:1759-1764.

2. Michler RE, Smith PK, Parides MK, et al. Two-year outcomes of surgical treatment of moderate ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1932-1941.

3. Smith PK, Puskas JD, Ascheim DD, et al. Surgical treatment of moderate ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2178-2188.

4. Acker MA, Parides MK, Perrault LP, et al. Mitral-valve repair versus replacement for severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:23-32.

5. Goldstein D, Moskowitz AJ, Gelijns AC, et al. Two-year outcomes of surgical treatment of severe ischemic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:344-353.

6. Anyanwu AC, Bridgewater B, Adams DH. The lottery of mitral valve repair surgery. Heart. 2010;96:1964-1967.

7. Iung B, Baron G, Butchart EG, et al. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe:The Euro Heart Survey on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231-1243.

8. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2739-2791.

9. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:e72-e227.

10. Ascaso M, Sandoval E, Quintana E, Vidal B, CastellàM, Pereda D. Early and mid-term outcomes of mitral repair due to leaflet prolapse in a national referral center. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74:462-4.

11. Fernández-Cisneros A, Ascaso M, Sandoval E, Pereda D. Cone repair for Ebstein's anomaly and atrial fibrillation ablation in an adult patient. Multimed Man Cardiothorac Surg. 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1510/mmcts.2020.064.

- Debate: Intervention on the mitral and the tricuspid valves. Perspective from interventional cardiology

- Debate: Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure. The interventional cardiology perspective

- Debate: Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure. The clinical cardiology perspective

- Debate: Refractory angina. The Reducer device as a new therapeutic approach. Perspective from the clinic

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

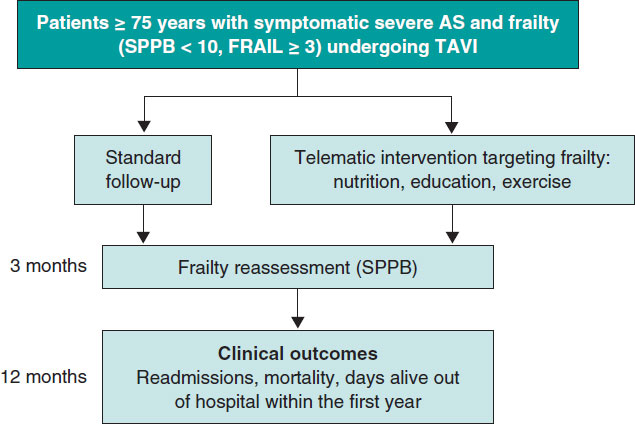

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España