Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: What is the benefit of intravascular imaging modalities—specifically the optical coherence tomography (OCT)—in the context of nonculprit lesions of an acute coronary syndrome (ACS)?

ANSWER: The publications of the COMPLETE and FLOWER MI clinical trials has changed the management of nonculprit lesions tremendously in patients with ACS jeopardizing the role of the pressure guidewire guiding the revascularization of these lesions.1,2 In the COMPLETE trial, angiography-guided complete revascularization reduced the rates of death and infarction compared to

the optimal medical therapy (OMT).1 We should mention that over 80% of the lesions included had an angiographic percent diameter stenosis ≥ 70%.1 In the FLOWER MI trial that included less severe nonculprit lesions, pressure guidewire-guided complete revascularization reduced the number of lesions treated (45% fewer lesions) compared to angiography-guided complete revascularization with a similar rate of events in both strategies.2 However, a subanalysis of the group of patients treated with pressure guidewire guidance revealed that patients with fractional flow reserve (FFR) values ≤ 0.80 (stented according to protocol) had fewer events compared to patients with FFR values > 0.80 (treated with OMT).3 This has aroused controversy regarding the utility of the pressure guidewire in this context. Probably the reason why the FFR has such a low negative predictive value is the lack of information on the composition of the plaque of the target lesion. In a subanalysis of the COMPLETE trial where nonculprit lesions were treated with OCT, it was reported that > 35% of the lesions with stenosis ≥ 70% were classified as vulnerable plaques compared to 25% of intermediate lesions (stenosis between 50% and 69%).4

Vulnerable plaques include a high lipidic content and are covered by a thin fibrous layer (≤ 65 μm according to pathological anatomy, which corresponds to ≤ 80 μm according to OCT if the axial resolution of this technique is taken into consideration).5 According to the PROSPECT clinical trials, the use of intracoronary ultrasound and infrared spectroscopy can detect vulnerable plaques in nonculprit coronary arteries in patients with ACS, and the former are associated with a high risk of triggering ACS at 4-year follow-up (up to 18% if they had a minimum lumen area and a large plaque burden).6,7

The role of OCT to detect vulnerable plaques in nonculprit lesions of ACS is still to be elucidated. However, since this intravascular imaging modality provides the highest resolution of all, it is probably the best imaging modality to assess the morphological characteristics of these lesions, particularly if they show signs of vulnerability.

Q.: How would you introduce the OCT in the assessment protocol of these lesion in relation to the pressure guidewire?

A.: In my opinion, the use of diagnostic intracoronary imaging modalities (whether with guidewire pressure or intravascular images) in severe nonculprit lesions (with percent diameter stenosis ≥ 70%) is not currently justified. Like I said before, severe nonculprit lesions on the angiography have high chances of being vulnerable plaques and, if untreated, are associated with a larger number of adverse events.1,4 As a matter of fact, with a level of evidence IA, the recent clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association published following the COMPLETE and FLOWER-MI trials recommend the revascularization of nonculprit lesions of ST-segment elevation ACS (STEACS) with percent diameter stenosis ≥ 70% on the angiography.8

However, the role these diagnostic intracoronary imaging modalities play in intermediate lesions (stenosis between 40% and 69%) or even in angiographic segments without overt angiographic lesion is still to be elucidated. An early assessment of intermediate lesions with FFR through pressure guidewire allows us to select those lesions that, per se, trigger ischemia. According to former studies on this type of intermediate lesions, nearly 45% of them show FFR values ≤ 0.80 and, therefore, have an indication for revascularization.2,9 As a matter of fact, the positive predictive value of FFR values ≤ 0.80 is not discussed here, and the management of lesions with pathological FFR values is currently backed by the routine clinical practice guidelines with a level of evidence IA.8,10 In my opinion, the utility of the OCT should be reviewed in lesions that don’t trigger ischemia (like lesions with FFR values > 0.80) and when the management of nonculprit lesions is purely preventive.

Up until now, only 1 study has assessed the preventive treatment of nonculprit lesions with characteristics of vulnerability. The PROSPECT-ABSORB trial randomized nonculprit lesions with characteristics of vulnerability on the intravascular echocardiography to receive bioresorbable stents or OMT. In this trial, the preventive treatment of vulnerable plaques reduced the rates of events compared to treatment although the study was not designed to compare clinical events.11

Q.: In your opinion, what will the future bring, new protocols combined? maybe new techniques?

A.: The risk associated with a vulnerable plaque in patients with multivessel ACS is currently under study and discussion. After an infarction, over 50% of the ischemic events described at follow-up are due to nonculprit lesions.7 The Spanish Society of Cardiology Working Group on Intracoronary Diagnosis of the Interventional Cardiology Association has inspired a randomized clinical trial that will include over 40 Spanish centers. The VULNERABLE trial (NCT 05599061) will study nearly 2500 patients with STEACS and angiographically intermediate nonculprit lesions (angiographic percent diameter stenosis between 40% and 69%). Per protocol, these lesions will be studied in an elective procedure different from the index procedure with which the culprit lesion was treated successfully. All eligible lesions will be interrogated using the pressure guidewire, and those with pathological FFR values (≤ 0.80) will be stented and considered a selection failure (it is estimated that nearly 40% of the lesions studied). The remaining lesions (1500 approximately) with FFR values > 0.80 will be studied with the OCT looking for characteristics of vulnerability. Lesions without these characteristics (an estimate of 900 lesions) will be treated with OMT and periodically followed to assess adverse events (within the VULNERABLE Registry). Finally, the study will include a total of 600 lesions with negative FFR but with characteristics vulnerability on the OCT that will be randomized (1:1) to stenting or OMT (within the VULNERABLE clinical trial). The follow-up period scheduled for both registry patients and the clinical trial is 4 years. This is the first trial ever conducted with statistical power to assess the clinical effectiveness of preventive stenting of nonculprit lesions with characteristics of vulnerability according to the OCT.

Q.: How would you bring together the concepts of vulnerable plaque and vulnerable patient?

A.: In my opinion, patients with ACS have 3 different problems occurring simultaneously. First, like I mentioned before, they have a type of aggressive atherosclerosis with significant plaque burden and characteristics of vulnerability.4 Second, patients with ACS have a higher degree of microvascular dysfunction, not only in the infarct-related artery but also in other nonculprit arteries.12 Pancoronary microvascular dysfunction is probably associated with a higher sensitivity to the chronic ischemia due to epicardial obstructive coronary lesions and the inability to create collateral circulation in the presence of a new acute complete obstruction (therefore associated with a higher risk of infarction). And third, patients with ACS have elevated inflammatory markers, more platelet reactivity, and more thrombogenicity compared to chronic patients.13 As a matter of fact, anti-inflammatory treatments have proven capable of reducing adverse events in patients with ACS.14

Therefore, patients with ACS have anatomical, functional, and systemic inflammatory-thrombotic characteristics that clearly separate them from chronic patients. This differentiation is mainly based on a higher risk of new thrombotic events in the future. Some, actually, call them «vulnerable patients». The management of these «vulnerable» patients should address these 3 problems at the same time. Therefore, therapeutic advances are necessary to reduce the plaque burden and stabilize vulnerable plaques. Also, antiplatelet therapies to reduce ischemic risk, at least, until most vulnerable plaques have stabilized, and eventually therapies to reduce systemic inflammation and, probably, improve the endothelial function of these patients.

The role of preventive angioplasty with stenting in vulnerable plaques is still to be elucidated. Undoubtedly, one of the dilemmas we’ll have to elucidate in the future is whether to choose intensive medical therapy with new drugs capable of stabilizing vulnerable plaques or «stabilization sealing» of neointimal tissue layer induced by stenting plus OMT.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Mehta SR, Wood DA, Storey RF, et al. Complete Revascularization with Multivessel PCI for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1411-1421.

2. Puymirat E, Cayla G, Simon T, et al. Multivessel PCI Guided by FFR or Angiography for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:297-308.

3. Denormandie P, Simon T, Cayla G, et al. Compared Outcomes of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients with Multivessel Disease Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Preserved Fractional Flow Reserve of Non-Culprit Lesions Treated Conservatively and of Those with Low Fractional Flow Reserve Managed Invasively: Insights from the FLOWER MI trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e011314.

4. Pinilla-Echeverri N, Mehta SR, Wang J, et al. Nonculprit Lesion Plaque Morphology in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: Results From the COMPLETE Trial Optical Coherence Tomography Substudys. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e008768.

5. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13-18.

6. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226-235.

7. Erlinge D, Maehara A, Ben-Yehuda O, et al. Identification of vulnerable plaques and patients by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy and ultrasound (PROSPECT II): a prospective natural history study. Lancet. 2021;397:985-995.

8. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e4-e17.

9. Koo BK, Kang J, Wang J. Fractional Flow Reserve or Intravascular Ultrasound for PCI. Reply. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:2099.

10. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. The Task Force on myocardial revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

11. Stone GW, Maehara A, Ali ZA, et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Vulnerable Coronary Atherosclerotic Plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2289-2301.

12. van de Hoef TP, Bax M, Meuwissen M, et al. Impact of coronary microvascular function on long-term cardiac mortality in patients with acute ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:207-215.

13. Matsuo K, Ueda Y, Nishio M, et al. Thrombogenic potential of whole blood is higher in patients with acute coronary syndrome than in patients with stable coronary diseases. Thromb Res. 2011;128:268-273.

14. Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2497-2505.

QUESTION: What kind of evidence supports the use of the pressure guidewire for the management of nonculprit lesions in patients with multivessel disease? Can you explain to us the controversy surrounding the results of the most recent clinical trials compared to the former ones?

ANSWER: I would like to start by contextualizing the change of paradigm we’ve been experiencing regarding myocardial revascularization. In controlled clinical trials of stable coronary artery disease, compared to optimal medical therapy, unfortunately, myocardial revascularization—the percutaneous one (PCI) in particular—has not been able to reduce clinical events whether angiography-guided (COURAGE and BARI 2D trials) or guided by non-invasive ischemia detection studies (ISCHEMIA trial).1 1It is hard to believe that although there is a significant correlation between the degree of ischemia documented non-invasively and the risk of adverse events, revascularization based on the information that, as interventional cardiologists, we collecrt from non-invasive studies doesn’t lead to better clinical outcomes compared to non-revascularizing the patient leaving him with ischemia and on optimal medical therapy. Here’s where the use of the pressure guidewire (PG) during the procedure (and possibly its angiographic alternatives) seems to lead to a different outcome. Currently, 3 randomized clinical trials are being conducted—2 of them in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS)—comparing the clinical events associated with PG- and optimal medical therapy-guided myocardial revascularization alone. A recent metanalysis revealed that, compared to optimal medical therapy, PG-guided myocardial revascularization reduces the risk of cardiac death an infarction significantly at 5 years.2 We should mention that this is a high-quality metanalysis that only included randomized clinical trials and «hard» events in its primary outcome. Also, unlike the ISCHEMIA trial that reported more early events associated with revascularization, fewer events were also documented in the PG arm from the beginning of follow-up and, as years went by, this event difference has grown favorable to revascularization. This and other information suggest that the PG allows us to select more accurately compared to angiography the segments of epicardial arteries where the benefits of PCI exceed risks.3,4 This evidence has changed the clinical practice guidelines that now recommend the use of the PG for the lack of previous evidence of ischemia and when the use of revascularization is under consideration. However, although this recommendation has been effective for years, the clinical use of PG is still low worldwide.

Recently, some PG studies have shown neutral or negative results: the FUTURE, RIPCORD 2, FAME 3, and the FLOWER-MI.4 Without smearing the effort made by the investigators, I’ll try to share my view on these trials.

The FUTURE trial randomized patients with and without ACS and 2- or 3-vessel disease to routine or PG-guided revascularization.3,4 The study was interrupted by the safety committee after only 54% of the entire sample was recruited and due to an increased overall mortality rate reported in the PG group. It is always difficult to interpret a study without statistical potential due to the sample size. However, the lack of differences in infarction and cardiac death makes it hard to explain how the PG can increase overall mortality through non-cardiac ways. Also, upon decision by the investigators, over 20% of negative lesions according to the PG were revascularized, which increased the number of procedures performed and stents used in the PG arm. This dropped the rate of revascularization down to 12.6% when, overall, in PG studies where a lower rate of stenting (30%) is often reported.

The RIPCORD-2 included 1100 patients with stable symptoms or ACS without ST-segment elevation randomized to angiography-guided revascularization or systematic use of the PG. The study concluded that the systematic use of the PG did not improve quality of life or reduced costs compared to the angiography-guided PCI. It’s surprising to see how the PG was used in this study since, per protocol, PGs were used in all the arteries even in the absence of visible atherosclerosis. In my opinion, this is a complete game changer from the clinical use of PG, prolongs time, and increases risk without a clear justification. We still don’t know if this proposal of using PG could be associated with the increased number of events seen at 1 year in the PG arm—close to 9%—which was high compared to many other PG studies. However, statistically, it was similar to the one seen in the angiography-guided PCI group of the same study.

There is nothing controversial about the FAME 3, I think. For years, we’ve been seeing the same slide in several meetings showing how the PG-related number of events from the FAME trial was similar to the number of events reported in the surgical arm of the SYNTAX trial. That’s the origin of the FAME 3 that compared—with a non-inferiority design—PG-guided surgical to percutaneous revascularization for the management of 3-vessel disease. It was a disappointment to see that the PG-guided PCI is not inferior to surgery even accepting a large non-inferiority margin of 45%. Although the use of intracoronary imaging was low in the FAME 3, it’s not easy to think of an image-guided PCI study reaching non-inferiority compared to surgery given the results of the recent FLAVOUR trial that assessed PG- vs intracoronary ultrasound-guided PCI. Similar clinical outcomes were seen with both strategies at the expense of a 30% increase in the number of stents from the image group.5 We hope that, in the future, it’ll tell us if the interventional strategy included in the SYNTAX II cohort (combining an optimal selection of patients with PG- and intracoronary imaging-guided PCI including total occlusions) is non-inferior to surgery in a controlled clinical trial.

Last but not least, the FLOWER MI trial.6 In my opinion, it is the only one that suggests, in a convincing way, that safety is lower when decisions are based on PGs in patients with ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (STEACS). In the FLOWER MI, a total of 1171 patients with STEACS were randomized to receive angiography- or PG-guided total revascularization after treating the culprit artery. Although the 1-year cumulative rate of the primary event did not change between both arms, a statistically non-significant increase in the risk of infarction (77% in the PG arm) was reported. Also, the estimated cut-off of the effect for the primary endpoint suggests PG-related damage and no benefit. Still, the accuracy of this effect estimate is low and non-significant.

Q.: What kind of evidence supports the use of the PG in nonculprit lesions of an ACS? Do you think it’s strong enough to recommend it?

A.: Currently, 2 large metanalyses are being conducted including the evidence available on the use of PGs in nonculprit lesions, which is large. The first one conducted by Cerrato et al.3 of 8579 patients from 5 different cohorts, 6461 of whom had stable symptoms and 2118 ACS.3 A larger number of events was seen in the group of patients with PG-guided delayed revascularization with ACS compared to the group of patients in stable condition. However, and significantly, patients with ACS treated with PCI had more events compared to patients with ACS and PG-guided delayed treatment. This study suggests that safety of PG-guided delayed PCI depends on the clinical presentation being safer with stable symptoms compared to ACS. Also, that treating nonculprit lesions doesn’t reduce the chances of events compared to delaying the procedure unlike what the FLOWER-MI reported. We should mention that this metanalysis could not distinguish STEACS from other forms of ACS, which is why it should be interpreted in detail.

The second metanalysis is important because it compares all randomized clinical trials currently available on 3 strategies for nonculprit lesion revascularization proposed for patients with STEACS: culprit lesion only revascularization, angiography- and PG-guided total revascularization.4 A total of 8195 patients from 11 randomized clinical trials were included. It was reported that in patients with multivessel disease and STEACS, angiography- or PG-guided total revascularization is associated with a lower rate of adverse events compared to the strategy of revascularizing the culprit lesion only. Also, the PG-guided strategy was associated with a non-significant increased risk of adverse events of 23% (95% confidence interval, 0.78-1.94) compared to the angiography-guided total revascularization strategy. Therefore, in the management of STEACS, angiography-guided total revascularization strategy is far more superior compared to the culprit lesion-only revascularization and similar to PG-guided revascularization. However, the effect estimate of the last comparison is favorable to the total angiography strategy.

Q.: Are there any differences based on the type of ACS with or without ST-segment elevation?

A.: This is not an easy question to answer because most studies report combined data of ACS without stratifying STEACS and NSTEACS.2,3,4 What we know so far is that the current evidence that has generated controversy comes specifically from patients with STEACS. This is consistent with the maturity of multiple lines of research that suggest that the nonculprit lesions of patients with STEACS behave more aggressively compared to the same lesions in patients with stable symptoms. We should remember that, overall, PG-related non-significant lesions in stable disease are responsible for 3% to 4% of clinical events per year while contemporary stents are responsible for an annual 6%. Therefore, if treated, we could be inducing damage. However, non-significant lesions according to the PG in patients with STEACS seem to cause more events—with rates close to 8%—like a substudy of the FLOWER-MI suggests.7 Therefore, any procedure performed here may be associated with more benefits than risks. Therefore, the utility of PG specifically in STEACS seems lower. Finally, we should mention that the results of the COMPLETE and FLOWER MI trials cannot be extrapolated to the STEACS setting. Also, there are many more studies supporting the utility of the PG in this scenario. Therefore, until future studies with robust designs analyze the safety profile of PG to treat NSTEACS, we won’t be able to determine whether safety is closer to the one reported in the stable context or discretely lower, as in the case of STEACS.

Q.: Are there any differences based on the type of index, whether hyperemic or not?

A.: The differences between hyperemic and non-hyperemic indexes does not seem to be very significant from the clinical standpoint. However, when we migrate from clinical trials to physiological indexes (that report, in small series, their findings from combined measurements of pressure and intracoronary flow) it’s hard to determine what indexes are better diagnostic tool in the ACS setting since results are controversial. Therefore, there seems to be greater scientific consensus recognizing a transient fatigue of hyperemic response compared to recognizing significant changes to the baseline conditions. This transient fatigue of hyperemic response is characterized by a reduced coronary flow reserve and an increased coronary fractional flow reserve, a situation that could clinically produce more false negatives with hyperemic compared to non-hyperemic indexes.8 Despite of all this, currently, there are no solid arguments to prefer hyperemic over non-hyperemic indexes.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Echevarría-Pinto is speaker and proctor for manufacturers of pressure guidewires (BSC, Abbot, and Philips).

REFERENCES

1. Mavromatis K, Boden WE, Maron DJ, et al. Comparison of Outcomes of Invasive or Conservative Management of Chronic Coronary Disease in Four Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Cardiol. 2022;185:18-28.

2. Zimmermann FM, Omerovic E, Fournier S, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention vs. medical therapy for patients with stable coronary lesions: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:180-186.

3. Cerrato E, Mejía-Rentería H, Dehbi HM, et al. Revascularization Deferral of Nonculprit Stenoses on the Basis of Fractional Flow Reserve: 1-Year Outcomes of 8,579 Patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1894-1903.

4. Elbadawi A, Dang AT, Hamed M, et al. FFR- Versus Angiography-Guided Revascularization for Nonculprit Stenosis in STEMI and Multivessel Disease: A Network Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:656-666.

5. Koo BK, Hu X, Kang J, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve or Intravascular Ultrasonography to Guide PCI. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:779-789.

6. Puymirat E, Cayla G, Simon T, et al. Multivessel PCI Guided by FFR or Angiography for Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:297-308.

7. Denormandie P, Simon T, Cayla G, et al. Compared Outcomes of ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients With Multivessel Disease Treated With Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Preserved Fractional Flow Reserve of Nonculprit Lesions Treated Conservatively and of Those With Low Fractional Flow Reserve Managed Invasively: Insights From the FLOWER-MI Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e011314.

8. van der Hoeven NW, Janssens GN, de Waard GA, et al. Temporal Changes in Coronary Hyperemic and Resting Hemodynamic Indices in Nonculprit Vessels of Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:736-744.

QUESTION: What is the evidence available on the use of drug-coated balloons (DCB) in the de novo lesion setting?

ANSWER: Currently, the evidence on the use of DCB to treat de novo coronary artery lesions is limited. I’ll be focusing on the following randomized clinical trials that compared the use of iopromide-based paclitaxel-coated balloons with second-generations stents in the novo coronary artery lesions. The BASKET-SMALL trial 21 included 758 patients with de novo stenosis in vessels with diameters < 3 mm. The study primary endpoint was a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at 12 months. Patients were randomized to receive a DCB or a drug-eluting stent (DES); 25% were first-generation (TAXUS, Boston Scientific, United States) and 75% second-generation stents (Xience, Abbott, United States). The rates of MACE were similar in both groups at 12 months (7.5% for the DCB vs 7.3% for the DES; HR, 0.97; 95%CI, 0.58-1.64; P = .9180). These results still stand at 3-year follow-up (a 15% rate of MACE for both DCB and DES; HR, 0.99; 95%CI, 0.68-1.45; P = .5).2 Similarly, this trial found no differences in MACE among the following clinical settings: diabetes,3 chronic kidney disease,4 high risk of bleeding,5 and acute coronary syndrome.6 Clinical benefits can be described in very small caliber vessels (< 2.5 mm) according to 1 of the substudies.7 The PEPCADNSTEMI trial8 included 210 patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome and 1 culprit lesions without evidence of thrombus. Patients were randomized to receive DCB (N = 104) or stent (N = 106; 56% of them were treated with conventional stents vs 44% who were treated with DES). A total of 15% of the patients from the DCB group received a bailout stent. At 9 months, the rate of target lesion failure was similar in both groups (3.8% for the DCB vs 6.6% for the DES; intention-to-treat analysis, P = .53). The REVELATION trial9 randomized 120 patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction with not heavily calcified de novo coronary artery lesions and residual stenosis < 50% after predilatation to receive DCB or DES. The study main primary endpoint was fractional flow reserve at 9 months in the infarct-related artery. A total of 11 patients (18%) from the DCB group required stenting. Fractional flow reserve estimated at follow-up was similar between both groups: 0.92 ± 0.05 in the DCB group and 0.91 ± 0.06 in the DES group; P = .27.

Recently, other DCBs with formulations from limus-type drugs—sirolimus and biolimus—have been assessed. Therefore, the BIO-RISE trial10 included 206 patients with de novo lesions in small vessels (between 2.0 mm and 2.75 mm) who were randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive a conventional balloon or a biolimus-coated balloon. At 9 months, late lumen loss was significantly lower in the DCB group (0.16 mm ± 0.29 mm vs 0.30 mm ± 0.35 mm; P = .001). Similarly, positive remodeling was described in 29.7% of the patients from the DCB group vs 9.8% of the patients from the conventional balloon group; P = .007). Finally, the randomized clinical trial SCBDNMAL11 compared a crystalline sirolimus-based DCB with a iopromide-based paclitaxel-coated balloon (SeQuent SCB, B. Braun Melsungen, Germany [4 μg/ mm2] vs DCB SeQuent Please, B. Braun Melsungen, Germany [3 μg/ mm2]) in 70 patients with de novo lesions. At 6 months, late lumen loss was 0.01 mm ± 0.33 mm in the paclitaxel group vs 0.10 mm ± 0.32 mm in the sirolimus group (95%CI, from -0.07 to 0.24). Negative late lumen loss was described indicative of positive remodeling with a greater frequency in the paclitaxel based DCB group (60% vs 32%; P = .019).

Q.: Do you think there is enough evidence to recommend their use in the routine clinical practice?

A.: At this point, evidence indicates that DCB can play a role to treat de novo lesions in small vessels. However, several premises should be taken into consideration. The landmark studies upon which this indication should stand are those where the comparison stent should be a latest generation stent. Therefore, evidence from trials that compared the use of DCB vs conventional stents or first-generation DES should not be extrapolated to the current situation. Secondly, when the DCB strategy is analyzed in the de novo lesion setting, optimal lesion preparation should precede without flow-limiting dissections and residual stenosis of 30% at most.12 Only then the use of DCB is advised. We should remember that stents were designed to solve the potential risk of acute vessel occlusion after balloon predilatation and that, incidentally, it also reduced the rate of restenosis. In this sense, like we have already seen in former studies, there will always be a percentage of lesions that will eventually need stenting as a bailout strategy after predilatation. Thirdly, the type of balloon, type of drug used, formulation, and release are much more relevant when treatment with DCB is planned. Obviously, not all DCBs are the same in this setting, which means that the results from 1 study with a certain type of DCB shouldn’t be extrapolated to another DCB with a different formulation or drug release system. Finally, when dealing with de novo lesions the characteristics of these should be known such as calcifications, thrombus, size of the vessel, length, clinical syndrome, etc.

Therefore, while we await the results of the ongoing clinical trials13 we can use iopromide-based paclitaxel-coated balloons to treat de novo stenoses in small vessels after optimal lesion preparation for the lack of significant traits of risk of acute vessel thrombosis (lack of significant residual dissection, flow-limiting, etc.).

Q.: Do you think that there are differences in the results obtained from the studies and in the level of evidence according to the size of the target vessel?

A.: To know the exact role of sirolimus-based DCBs in the management of de novo coronary lesions is still premature.14 In such a hydrophilic drug, dose, formulation, and release are crucial to define its potential. Therefore, results can vary tremendously based on whether we’re dealing with phospholipid encapsulated sirolimus or a crystalline coating, for instance. Regarding the size of the vessel, the use of the DCB is spared for small caliber vessels (< 3 mm), and, among them, it seems like very small caliber vessels (< 2.5 mm) are the ones that can benefit the most from its use.7

Q.: In which cases would you consider using DCBs to treat de novo coronary artery lesions?

A.: Like I said before, the current evidence available supports its use to treat small caliber coronary vessels, and with a certain type of DCB only (iopromide-based paclitaxel-coated balloons, 3 μg/mm2).

Q.: What is the predilatation protocol, cross-over criteria, and specific DCB treatment technique in this setting?

A.: I use the DCB-only strategy, which involves good target vessel preparation, obtaining good angiographic results without clinically relevant residual dissections, and residual stenosis < 30%. It is in this setting where the bailout stent is not necessary that I use the DCB.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Sabaté is a consultant for Abbott Vascular and iVascular.

REFERENCES

1. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;392:849-856.

2. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): 3-year follow-up of a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1504-1510.

3. Wöhrle J, Scheller B, Seeger J, et al. Impact of Diabetes on Outcome With Drug-Coated Balloons Versus Drug-Eluting Stents: The BASKET-SMALL 2 Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1789-1798.

4. Mahfoud F, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease in patients with chronic kidney disease: a pre-specified analysis of the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2022;111:806-815.

5. Scheller B, Rissanen TT, Farah A, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon for Small Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With and Without High-Bleeding Risk in the BASKET-SMALL 2 Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e011569.

6. Mangner N, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Drug-Coated Balloons Versus Drug-Eluting Stents in Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Prespecified Analysis of BASKET-SMALL 2. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e011325

7. Farah A, Elgarhy M, Ohlow MA, et al. Efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons according to coronary vessel size. A report from the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial. Postepy Kardiol Interwencyjnej. 2022;18:122-130.

8. Scheller B, Ohlow MA, Ewen S, et al. Bare metal or drug-eluting stent versus drug-coated balloon in non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the randomised PEPCAD NSTEMI trial. EuroIntervention. 2020;15:1527-1533.

9. Vos NS, Fagel ND, Amoroso G, et al. Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stent in Acute Myocardial Infarction: The REVELATION Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1691-1699.

10. Xu K, Fu G, Tong Q, et al. Biolimus-Coated Balloon in Small-Vessel Coronary Artery Disease: The BIO-RISE CHINA Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1219-1226.

11. Ahmad WAW, Nuruddin AA, Abdul Kader MASK, et al. Treatment of Coronary De Novo Lesions by a Sirolimus- or Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:770-779.

12. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease: Third Report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402.

13. Greco A, Sciahbasi A, Abizaid A, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary artery disease: Rationale and design of the TRANSFORM II randomized clinical trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100(4):544-552.

14. Sabaté M. Sirolimus Versus Paclitaxel: Second Round. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:780-782.

QUESTION: What is the evidence available on the use of drug-coated balloons (DCB) in the de novo lesion setting?

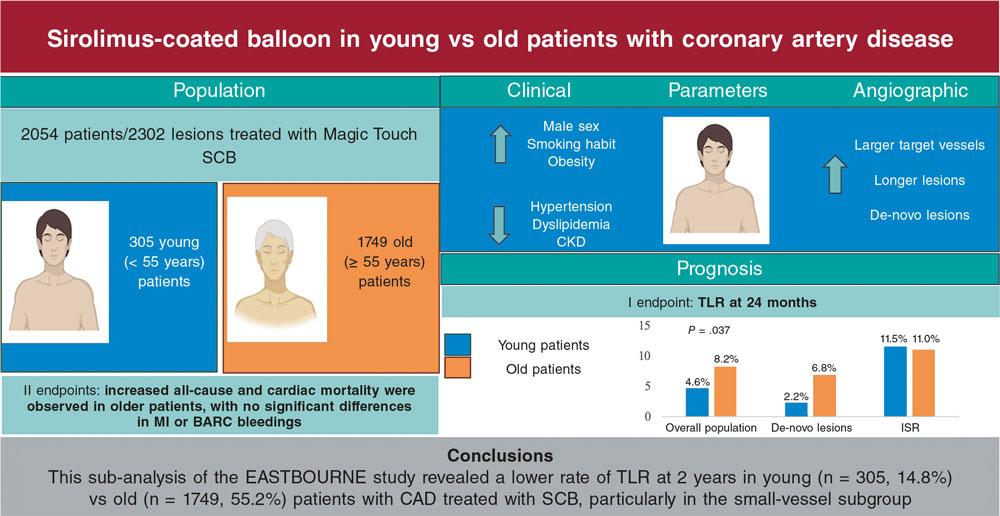

ANSWER: The use of DCB to treat de novo lesions is the most compelling argument regarding this technology, an area that has advanced significantly over the last 5 years. Only recently, investigators and companies have begun to understand that this area also needed strong and reliable scientific evidence similar to the one provided for stent platforms, to understand the real safety and efficacy profile of DCB in the de novo lesion setting. Argument here is currently quite strong: the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial (700 patients) showed no differences at 3 years between paclitaxel-coated balloon and drug-eluting stents (DES),1 the EASTBOURNE (2100 patients) showed the 1-year safety and efficacy profile of the first sirolimus-coated balloon (target lesion revascularization, 5%),2 the PICCOLETO II trial3 showed fewer major adverse cardiovascular events with another paclitaxel-coated balloon compared to an everolimus-eluting stent in the small vessel setting at 3-year follow-up. Finally, the RESTORE SVD trial showed similar results with another paclitaxel-coated balloon at the long-term follow up and similar data vs DES.4 Interestingly enough, the long-term follow-up of the 2 latter trials was presented in September 2022 at the TCT Conference (late breaking clinical science session) confirming that this field is currently highly active.

Q.: Do you think there is enough evidence to recommend their use in the routine clinical practice?

A.: Evidence is compelling enough to recommend DCB in this setting. However, some simple rules should be applied a) we recommend using these devices in the in-stent restenosis setting under imaging guidance for proper lesion assessment. Therefore, treatment of small coronary vessels (< 2.5 mm) can be adopted. Afterwards, larger vessels should also be treated with DCB. The important thing here is to “have a good eye” to treat coronary artery dissections left after treatment (please see below); b) class effect does not exist for DCB. Therefore, only devices with robust clinical data should be used in this setting. Angiographic monitorization is often unnecessary unless DCB is used in a complex lesion setting without prior reliable experience or scientific evidence.

Q.: Do you think that there are differences in the results obtained from the studies and in the level of evidence according to the size of the target vessel?

A.: We believe that most DCBs can also be used for larger vessels (> 3 mm), but a wide use in this setting can be suggested in selected cases only where the stent is not seen as a safe enough solution (highly complex calcified lesions, trifurcations...). Also, the broader use of DCB requires more clinical data—that are still pending—which will hopefully be provided within the next 2 to 3 years. Unfortunately, direct comparisons among DCBs are not available yet except for a small, sponsored trial. A couple of years ago we “indirectly” compared a paclitaxel- and a sirolimus-coated balloon in the SIRPAC trial (1100 patients) showing no differences at 1 year regarding hard endpoints.5 The ongoing TRANSFORM I trial, which has recently completed the enrollment, is comparing paclitaxel- and sirolimus-based DCBs on mid-term angiographic and optical coherence tomography outcomes.6 This mechanistic study is important because it will shed light on the current effect of these drugs on the vessel wall, and on the role paclitaxel plays determining late lumen enlargement for a direct effect in the adventitia, something that is still to be proven by sirolimus. Finally, the ongoing TRANSFORM II trial that is comparing a sirolimus-based DCB to a DES will shed light on the long-term role of this technology.7 In this study, whose primary endpoint is TLF, patients with native vessel disease will be treated and followed for 5 years.

Q.: In which cases would you consider using DCBs to treat de novo coronary artery lesions?

A.: To be honest, given the drawbacks of stents in the small vessel disease and complex lesion settings, here a DCB would be our first choice due to the inherent safety of this technology. For example, in a heavily calcified coronary lesion, despite proper lesion preparation, we often prefer using a DCB when we are not totally sure that the stent will accommodate perfectly with an adequate expansion and apposition. The takeaway here is that DCBs can also lead to restenosis. However, they are safe and do not lead to thrombosis or acute vessel occlusion. Only in case of flow-limiting dissections or acute recoil, a bailout stent should be used after a DCB. Also, we should always remember that a stent-like result after DCB angioplasty should not be expected or is not needed either.

Q.: What is the predilatation protocol, cross-over criteria, and specific DCB treatment technique in this setting?

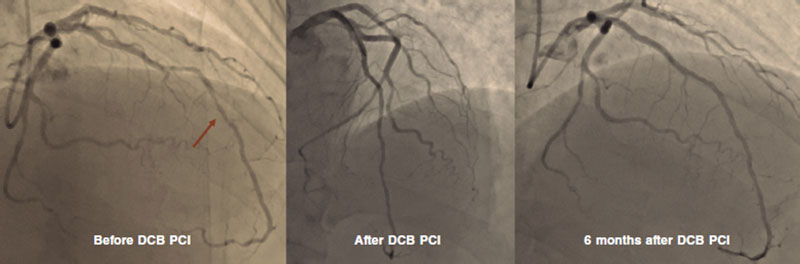

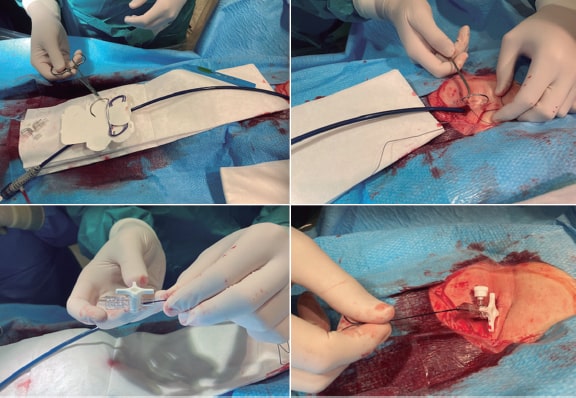

A.: This is a long topic of discussion, and dedicated courses should be followed to “have a good eye” on DCB angioplasty. Our initial suggestion is to adopt a stepwise approach when performing a DCB angioplasty, which means that the main goal is to achieve good results after proper predilatation with whichever tools are available at the cath lab. We can still cross over to a stent angioplasty at any time before drug delivery so make the final choice between DCB and DES after lesion preparation only. Proper predilatation means final stenosis < 30% and no major or flow-limiting dissections.8 After this goal is achieved, the DCB can be used to cover the entire segment treated while keeping inflation for, at least, 30 seconds (possibly 60). In our routine clinical practice we use semi-compliant balloons, and quite often scoring balloons, but other centers use non-compliant balloons as the first choice. The balloon-vessel ratio should often be 1:1, but exceptions exist depending on the target lesion. In the end, type A or B dissections should be sought, and not feared (figure 1). Our group has previously demonstrated how these dissections are safe and not associated with acute vessel occlusions.9 Recently, investigators from Japan have shown how dissections are associated with improved penetration and increased lumen gain at 6 months after paclitaxel-based DCB angioplasty.10 To be considered “expert” DCB users, stenting rate after DCB should be < 10%.

Figure 1. DCB PCI of the middle segment of the left anterior descending coronary artery at 6-month angiographic follow-up. DCB, drug-coated balloon. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow MA, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): 3-year follow-up of a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;396:1504-1510.

2. Cortese B, Testa L, Di Palma G, et al. Clinical performance of a novel sirolimus-coated balloon in coronary artery disease: EASTBOURNE registry. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2021;22:94-100.

3. Cortese B, Di Palma G, Guimaraes MG, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small Coronary Vessel Disease: PICCOLETO II Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2840-2849.

4. Tang Y, Qiao S, Su X, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small-Vessel Disease: The RESTORE SVD China Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2381-2392.

5. Cortese B, Caiazzo G, Di Palma G, De Rosa S. Comparison Between Sirolimus- and Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon for Revascularization of Coronary Arteries: The SIRPAC (SIRolimus-PAClitaxel) Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;28:1-6.

6. Ono M, Kawashima H, Hara H, et al. A Prospective Multicenter Randomized Trial to Assess the Effectiveness of the MagicTouch Sirolimus-Coated Balloon in Small Vessels: Rationale and Design of the TRANSFORM I Trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;25:29-35.

7. Greco A, Sciahbasi A, Abizaid A, et al. Sirolimus-coated balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in de novo coronary artery disease: Rationale and design of the TRANSFORM II randomized clinical trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100(4):544-552.

8. Cortese B. The role of optimal lesion preparation for de-novo coronary vessels when a stentless intervention strategy is planned. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2020;68:51-56.

9. Cortese B, Silva Orrego P, Agostoni P, et al. Effect of Drug-Coated Balloons in Native Coronary Artery Disease Left With a Dissection. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. Dec 2015;8:2003-2009.

10. Yamamoto T, Sawada T, Uzu K, Takaya T, Kawai H, Yasaka Y. Possible mechanism of late lumen enlargement after treatment for de novo coronary lesions with drug-coated balloon. Int J Cardiol. 2020;321:30-37.

QUESTION: What aspects do you think might explain the significant differences reported between the results from the EBC MAIN (European bifurcation club left main coronary stent study),1 and the DKCRUSH-V (Double kissing crush vs provisional stenting for left main distal bifurcation lesions) clinical trials?2

ANSWER: The EBC MAIN trial has proven the non-inferiority of the step-by-step provisional stenting technique approach compared to the early double stenting strategy in 467 patients with distal left main coronary artery bifurcation disease (Medina 1,1,1 or 0,1,1). No significant differences were reported regarding the overall rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, target lesion failure, acute myocardial infarction, and stent thrombosis.1

On the other hand, the DKCRUSH V trial randomized 482 patients with distal left main coronary artery bifurcation disease (Medina 1,1,1 or 0,1,1) to receive treatment with the provisional technique vs the DK-crush technique. The latter had a lower rate of major adverse cardiovascular events with statistically significant differences regarding target lesion failure (10.7% vs 5%) (hazard ratio, 0.42; 95% confidence interval, 0.21-0.85; P = .02), acute myocardial infarction (2.9% vs 0.4%; P = .03), and stent thrombosis (3.3% vs 0.4%; P = .02) at 1-year follow-up.2 Results were better in the most complex coronary bifurcation lesions defined, above all, as those with greater side branch damage (> 70% of stenosis and > 10 mm of lesion length), severe calcification or well-defined angles (> 70 or < 45º).

Some have tried to compare data from the EBC MAIN to data from the DKCRUSH-V. However, there are aspects that just don’t make them comparable trials for study design reasons or for the overall results of the DK-crush technique: the complexity of bifurcation and the degree of damage to the side branch was lower in the EBC MAIN compared to the DKCRUSH-V defined by severity of stenosis > 70% and length > 10 mm. As a matter of fact, the mean side branch lesion length was 7 mm in the EBC MAIN vs 16 mm in the DKCRUSH-V, which can be seen in the rate of double stenting of the provisional group (22% in the EBC-MAIN vs 47% in the DKCRUSH-V). Similarly, the low rate of double stenting of the provisional group was left to the operator’s criterion allowing residual lesion in the ostial left circumflex artery of 90% vs 75% in the DKCRUSH-V. In my opinion, another factor penalizing the double stenting group is that only 5% of the patients were treated with the DK-crush technique since the most widely used ones were the culotte (53%), and the T or TAP (T and protrusion) techniques (33%). Also, 6% of the patients from the double stenting group could not receive the second stent unlike the DKCRUSH-V trial where the procedural success of the DK-crush group was 100%. The use of imaging modalities in both studies was similar in around 40% of the cases.3

Q.: In the light of the evidence available and based on your own experience, when do you recommend provisional stenting and when an early double stenting technique to treat distal left main coronary artery stenoses?

A.: Obviously, the only lesions eligible for 2-stent implantation into the distal left main coronary artery are those found in bifurcations we call complex or true bifurcations, that is, when both left main coronary artery branches are damaged (Medina 1,1,1 or 0,1,1). However, among these lesions, the complexity of left main coronary artery bifurcation lesions depends on many different factors, among them, the DEFINITION II trial criteria are the most widely used of all. As far as I know, they’re the most important ones of all regarding the selection of the bifurcation technique that will eventually be used: simple or complex (left main coronary artery bifurcation with side branch stenosis > 70% and lengths > 10 mm, moderate-to-severe calcifications, bifurcation angles < 45º or > 70º, multiple lesions, main vessel reference diameters > 2.5 mm, main vessel lesion lengths > 25 mm or presence of thrombus in the lesion).4

This trial proved that complex bifurcations, under these criteria, are associated with fewer events if treated with the complex double stenting technique compared to the provisional stenting technique. In my opinion, the most valuable criteria that should be used when having to decide between provisional or complex stenting techniques—rather than the severity of stenosis in the side branch—are side branch lesion lengths > 10 mm, moderate-to-severe calcifications, and bifurcation angles < 45º. Angles > 70º can be solved much easier using the provisional 1-stent technique with minimal protrusion in bailout T or TAP.

Q.: In how many angioplasties performed on the distal left main coronary artery is the double stenting technique often used?

A.: Provisional stenting technique used systematically is valid to treat most distal left main coronary artery disease including true bifurcations with side branch damage, assuming that 20% to 40% of the patients will end up with a second stent in the side branch. At our center, however, there are patients we directly treat with 2 stents for being high-complexity patients. The rate of left main coronary artery true bifurcations is somewhere between 25% and 30%.

Q.: What is your favorite double stenting technique in the distal left main coronary artery and why?

A.: I’d say scientific evidence is rather clear on what the double stenting technique of choice should be to treat complex distal left main coronary arteries. In addition to the aforementioned results from the DKCRUSH-V and the DEFINITION II trials where 77.8% of the patients treated with 2 stents received the DK-crush technique,1,4 2 meta-analyses recently published have confirmed the superiority of the DK-crush technique vs other bifurcation techniques. In the one conducted by Di Gioia et al.5 of a total of 5711 patients, 5 different bifurcation techniques used in the studies were compared (provisional stenting, T-stent, TAP, crush, culotte, and DK-crush). It was found that patients treated with the DK-crush technique had lower rates of major adverse cardiovascular events, significant differences regarding the need for new target lesion revascularization (odds ratio, 0.36; 95% confidence interval, 0.22-0.57), and no differences regarding cardiac death, myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis. The biggest clinical benefits from using the DK-crush technique were reported in lesions with side branch disease > 10 mm in length, that is, the most complex bifurcations of all. The second meta-analysis conducted this year by Park et al.6 after the publication of the EBC MAIN results—with a total of 8318 patients—reached the same conclusions. In the conventional meta-analysis, the DK-crush technique proves non-superior to the provisional stenting technique except for cases with side branch disease and lengths > 10 mm where there is a lower rate of cardiac death, and target vessel revascularization. However, when a multiple comparison analysis was conducted, the DK-crush technique had a lower rate of major adverse cardiovascular events regarding cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, and stent thrombosis compared to the provisional stenting technique and any other double stenting technique including T-stent, TAP, dedicated bifurcation stents, crush, and cullote.6

Among the complex double stenting techniques, the culotte one is a very flexible technique we can use to choose the branch we want to treat first, the main vessel or the side branch. Recently, changes have been made that improve its result by minimizing stent overlap in the main vessel and adding a first kissing balloon (KB) after the first stent implantation (DK-mini-culotte) thus improving stent comformability at bifurcation level and improving the success rate of the final KB.7 However, we still don’t have any evidence on the results of the DK-crush technique.

Despite the results published with the DK-crush technique, it has not become the technique of choice in most centers because it is technically very challenging since 8 very well-defined steps are involved that can’t be omitted since the technique needs to be refined in every step of the way. However, the main setback of this technique is that it is very much time-consuming. Also, the material needed is often unusual and without proper optimization, which means that it can jeopardize results in the real-world. Early POT (proximal optimization technique) is very important here, also KB with non-compliant high-pressure balloons, and final POT. Similarly, the technique needs to be refined based on the recommendations established in the EBC MAIN trial regarding POT, and the KB.

Finally, since this is a time-consuming and challenging technique that takes up a lot of resources, changes to this technique to optimize results and improve procedural times are almost non-stop. One of them is high-pressure stent postdilatation of the side branch at ostial level (proximal SB optimization) that improves stent comformability at carina level and facilitates later recrossing.8 The other one is the DR-crush (double rewire crush) technique that facilitates sequential dilatation of the side and main branches thus avoiding early KB, which simplifies the entire procedure with very good results at 2 years.9

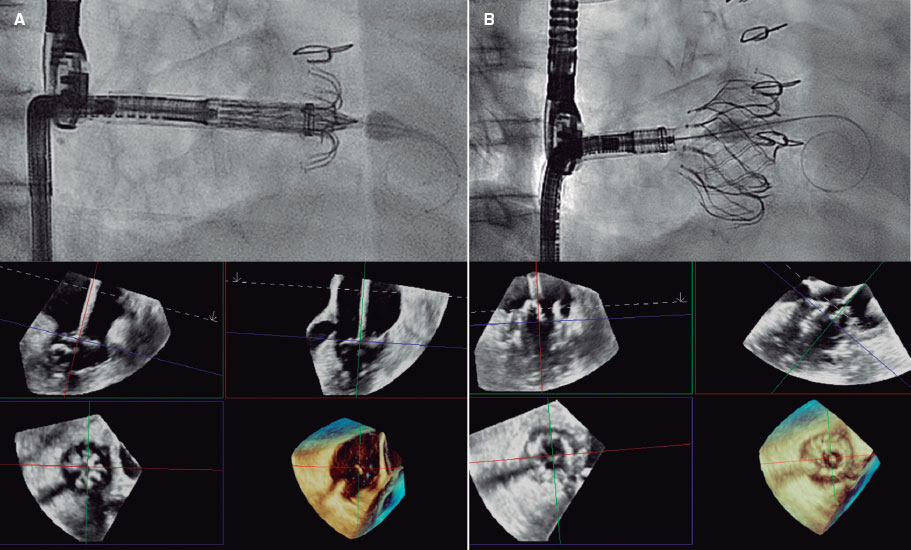

Q: In your opinion, do you think that the use of intravascular imaging modalities to guide these procedures on the left main coronary artery is important?

A: I believe we all agree that the use of imaging modalities to treat these bifurcation lesions at the left main coronary artery is mandatory to both plan the strategy that should be followed and assess the final outcomes. It is the only way to offer the best possible results in a lesion of such prognostic impact. Regarding the most appropriate technique, I think it should be the one the operator is more familiar with. Although it is true that intravascular ultrasound has gained traction to treat the left main coronary artery, since distal segment is involved and as long as we’re not dealing with short left main coronary arteries or excessively large calibers preventing good contrast, the optical coherence tomography would also be useful thanks to its high spatial resolution.

FUNDING

None reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None whatsoever.

REFERENCES

1. Hildick-Smith D, Egred M, Banning A, et al. The European Bifurcation Club Left Main Coronary Stent study: a randomized comparison of stepwise provisional vs. systematic dual stenting strategies (EBC MAIN). Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3829-3839.

2. Chen SL, Zhang JJ, Han Y, et al. Double Kissing Crush Versus Provisional Stenting for Left Main Distal Bifurcation Lesions: DKCRUSH-V Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2605-2617.

3. Jaffer HFA, Mehilli J, Escaned J. Left main coronary disease at the bifurcation: Should the pendulum swing back towards the provisional stenting approach? Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3840-3843.

4. Zhang JJ, Ye F, Xu K, et al. Multicentre, randomized comparison of two-stent and provisional stenting techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: the DEFINITION II trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2523-2536.

5. Di Gioia G, Sonck J, Ferenc M. Clinical Outcomes Following Coronary Bifurcation PCI Techniques: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Comprising 5,711 Patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1432-1444.

6. Park DY, An S, Jolly N, et al. Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis Comparing Bifurcation Techniques for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022;11:e025394.

7. Toth GG, Sasi V, Franco D, et al. Double-kissing culotte technique for coronary bifurcation stenting. EuroIntervention. 2020;16: e724-733.

8. Lavarra F. Proximal side optimization: A modification of the double kissing crush technique. US Cardiology Review. 2020;14:e02

9. Zhang D, He Y, Yan R, et al. A novel technique for coronary bifurcation intervention: Double rewire crush technique and its clinical outcomes after 2 years of follow-up. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93(S1):851-858.

- Debate: Percutaneous revascularization strategies for distal left main coronary artery disease. The EBC MAIN approach

- Debate: Pharmacological or invasive therapy in acute pulmonary embolism. The interventional cardiologist perspective

- Debate: Pharmacological or invasive therapy in acute pulmonary embolism. The clinician perspective

- Debate: Severe bicuspid aortic valve stenosis in non-high-risk surgical patients. In favor of TAVI

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

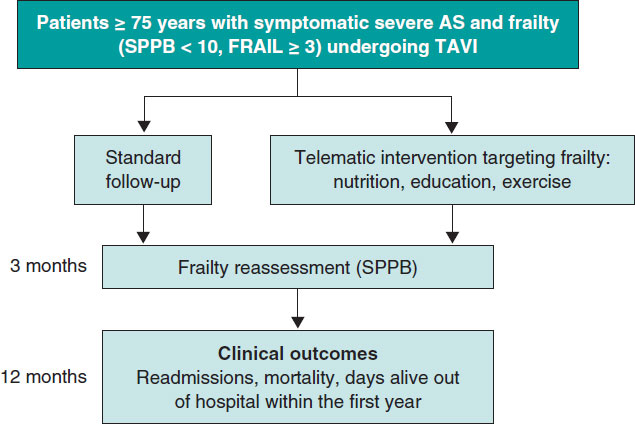

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España