Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: What relevant evidence could support aortic valve replacement today in cases of true severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis? Are there any studies on both techniques, surgery and transcatheter implantation?

ANSWER: Ross and Braunwald’s1 description of the outcomes of patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis (AS) almost 60 years ago laid the foundations for the indication for surgery—the first-line therapy to date—to treat this disease, although transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is also indicated. At a time when surgery was the only therapeutic option available, with mortality rates close to 3% to 4%, nobody thought of treating asymptomatic patients, who had a risk of sudden death of nearly 1%. These findings were confirmed by later studies, and the treatment of asymptomatic AS continued to lack evidence until the first decade of the 21st century when observational studies with small series of patients with severe asymptomatic AS (Vmax ≥ 4 m/s and mean gradient ≥ 40 mmHg) began to be published. In all of them, the results favored early surgical treatment. In the study of 197 patients by Kang et al.,2 the primary endpoint was a composite of operative and follow-up mortality. The 6-year cardiac and all-cause mortality rates were 0% and 2 ± 1% in the surgical group compared with 24 ± 15% to 32 ± 6% in the conservative treatment group. The CURRENT AS3 registry of Taniguchi et al, with 1808 patients (291 in the surgical group and 1517 in the conservative treatment group) favored the surgical group in terms of overall mortality (15.4% vs 26.4%; P < .009) and heart failure-related admissions (3.8% vs 19.9%; P < .0001). The only randomized clinical trials published to date comparing conservative vs surgical treatment are the RECOVERY4 and the AVATAR5 trials, both with a small number of patients (145 and 157, respectively), and both with results favorable to surgery. In the RECOVERY trial, the primary endpoint was a composite of procedural and cardiovascular mortality during follow-up, with rates of 1% in the surgical group and 15% in the conservative treatment group (hazard ratio [HR], 0.09; 95%CI, 0.01-0.67). The 4- and 8-year cumulative incidence rates of the primary endpoint remained at 1% in the surgical group vs 6% and 26% (P = .003) in the conservative treatment group. In the AVATAR trial, the primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, stroke, or unplanned heart failure-related admission, with rates of 15.22% and 34.7% at the 3-year follow-up (HR, 0.46; 95%CI, 0.23-0.9).

The first TAVI was performed back in 2002. Since then, we have come a long way regarding indications—although it’s only a short time—because in 20 years, TAVI has been recognized as the treatment of choice for inoperable and high surgical risk patients, with similar results compared to those of surgery in moderate and low surgical risk patients. These trials have focused on symptomatic patients. Several trials are under way in asymptomatic patients, EARLY TAVR (NCT03042104) and EVOLVED (NCT03094143), and their results will be published soon, but until then, the only evidence to date supporting treatment in asymptomatic patients is surgical.

Q.: When the decision is made to intervene in cases of severe asymptomatic aortic stenosis, on what grounds should the choice be made between surgery and TAVI? Would it be any different from the choice in a symptomatic case?

A.: The current clinical guidelines on the management valvular heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology6 still focus on the indication for treating AS based on symptoms; asymptomatic AS is not included in this indication, unless there are laboratory or echocardiographic predictors of rapid symptom progression. As explained earlier, there is currently more evidence on surgery in asymptomatic patients. However, a more in-depth analysis of the studies reveals 2 important facts. One is that the mean age was generally low: 65 years in the RECOVERY trial and 68 years in the AVATAR trial, and was very similar in registries. The other is that the causes of AS are highly variable: in the RECOVERY trial, 61% of the patients had bicuspid valves, 33% degenerative valves, and 6% rheumatic valves. In the AVATAR trial, 84.7% had degenerative valves, 14% bicuspid valves, and 1% rheumatic valves.

In Spain, where life expectancy is one of the longest worldwide—82 years in men and 87 years in women in 2023—most patients treated with TAVI have degenerative AS, and the incidence of bicuspid valves is lower than that reported by studies, which means that using the same criteria is challenging. However, it seems clear that severe or very severe AS, as included in the studies, shows better mid- and long-term survival rates when treated early, while asymptomatic. The severity criteria included in the studies (Vmax ≥ 4.5 m/s, mean gradient ≥ 50 mmHg) help us select those patients who benefit the most from early treatment. On the issue on what treatment we should use (surgery or TAVI), the decision is more complicated due to the lack of evidence on TAVI. As mentioned earlier, the average patients we treat are octogenarians. In some cases, AS is found during a routine examination, and if they are truly asymptomatic (because octogenarians often cut down on activity and have difficulty recognizing their own physical limitations) and meet severity criteria, an early intervention will result in better quality of life and fewer procedural complications. In my opinion, applying the same criteria used with symptomatic patients is beneficial for patients, meaning that, in patients with low-to moderate surgical risk, if we accept the results of TAVI trials,6-8 the transcatheter option is entirely acceptable. A different type of patient are those under follow-up because they have bicuspid valves or rheumatic disease. These patients are often younger and the indication for surgical valve replacement is clearer because TAVI still has limitations that need to be resolved in terms of durability, the need for new procedures if there is prosthetic valve degeneration, access to coronary arteries, and the treatment of bicuspid valves, which also remains poorly established. Additionally, TAVI is associated with a higher rate of pacemaker implantation, which, in young patients, is related to new comorbidities and various effects on ventricular function.

Therefore, the choice would be TAVI for octogenarians and surgery for younger patients. I would set patients from 75 to 80 years apart who could potentially receive transcatheter treatment based on their own preferences.

On the issue of whether treatment would differ in asymptomatic compared with symptomatic patients, in my opinion, this would not be the case. AS is a continuum in which symptoms appear sooner or later. Although it seems that we can base our decisions on evidence when treating symptomatic AS, we have to think that the benefit to the patient is greater as physical and pathophysiological conditions will always be better before symptom onset. In fact, sometimes the changes triggered by symptomatic AS can be irreversible. Treating asymptomatic patients requires both us and surgeons, who have already reduced mortality down to 1% in these patients, more meticulous approaches regarding valve selection and implantation, correctly selecting the valve while minimizing risks and complications, since patients should benefit in the short- and long-term.

Q.: Any considerations on the TAVI technique that should be used in these cases?

A.: When we decide to perform TAVI in a symptomatic patient, we assess the anatomical and clinical factors involved. The same applies to asymptomatic patients: on the one hand, if the patient is young and has a bicuspid valve, the valve selected should have enough radial strength, a low pacemaker implantation rate, and give us room to plan a second TAVI in the future while securing access to the coronary arteries. If a self-expanding supra-annular valve is selected, the current tendency is to place the prosthetic valve as high as possible with respect to the annulus to minimize the risk of pacemaker implantation. This may compromise access to the coronary arteries, which is why, commissural alignment should be attempted, as far as possible. To avoid complications such as stroke, which can be devastating in young patients, the use of embolic protection devices is justified, although the only randomized clinical trial published to date has not shown any benefits in specific subgroups for stroke in general (primary endpoint) as opposed to disabling stroke (not the primary endpoint). In older asymptomatic patients with degenerative AS, the implantation technique follows the same pattern used with symptomatic patients.

Q.: What is the current management of these patients in your center?

A.: At the Álvaro Cunqueiro Hospital, all patients are discussed in a heart team session, where the treatment criteria are more or less clear. Asymptomatic patients come through various routes: one is patients with valvular heart disease under clinical surveillance who develop severity criteria during follow-up. If the patient is older than 80 years, the decision is often to use the transcatheter approach, from 75 to 79 years, either of the 2 treatments would be fine, and the patient’s preference is a consideration, and if the patient is younger than 75 years, the decision is often to perform surgical valve replacement. Patients with bicuspid valves are often young and initially referred for surgical treatment.

In other patients, AS is found during routine examination due to another disease. Here, there’s a subgroup that requires quick decision-making: patients with neoplasms or interventions that cannot be delayed for too long. In these cases, transcatheter treatment is the chosen one because implantation is possible once the results from the computed tomography become available. The intervention is performed within the next few days, with rapid recovery, before the next intervention. If the patient is young and has a bicuspid valve, a balloon-expandable valve is often used. If the patient is older and doesn’t have coronary artery disease, a self-expanding valve is used. If the patient has coronary artery disease to be treated after the intervention, if necessary, a self-expanding valve with easy access to the coronary arteries is often implanted. If vascular access is suboptimal, a self-expanding valve is also the preferred choice due to its better profile.

If asymptomatic patients don’t have any other conditions requiring immediate treatment, they are treated as if they were symptomatic patients, except for patients with criteria of very severe AS (Vmax ≥ 5 m/s, mean gradient ≥ 60 mm Hg, and progression of Vmax ≥ 0.3 m/s/year), who are treated preferentially.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. A. Baz Alonso is a proctor for Biosensors for the Allegra valve implantation, and advisor to Medtronic Iberia on structural heart diseases.

REFERENCES

1. Ross J, Braunwald E. Aortic stenosis. Circulation. 1968;38 suppl V:61-67.

2. Kang DH, Park SCJ, Rim JH, et al. Early surgery versus conventional treatment in asymptomatic very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2010;121:1502-1509.

3. Taniguchi T, Morimoto T, Shiomi H, et al. Initial surgical versus conservative strategies in patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2827-2838.

4. Kang D-H, Park S-J, Lee S-A, et al. Early surgery or conservative care for asymptomatic aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:111-119.

5. Banovic M, Putnik S, Penicka M, et al. Aortic valve replacement versus conservative treatment in asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis:the AVATAR trial. Circulation. 2022;145:648-658.

6. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

7. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Evolut Low Risk Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706-1715.

8. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

QUESTION: What’s your interpretation of the REVIVED BCIS2 trial? Which, would you say, are its most positive and debatable features?

ANSWER: The REVIVED BCIS21 trial randomized stable patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) along with optimal medical therapy (OMT) or OMT alone without revascularization. The trial included patients with left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 35%, extensive coronary artery disease, and viability in 4 or more segments amenable to PCI. The results proved that the 2 strategies offered comparable outcomes regarding the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or hospitalization-related heart failure (37.2% vs 38.0%; hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-1.27; P = .96). There were no differences in the changes in left ventricular ejection fraction recorded at 6 months and at 1 year, with improvement confirmed in both groups.2 Previously, the STICH trial2,3 had demonstrated that surgical revascularization combined with OMT provided long-term overall survival benefits in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, despite an initial increase in surgery-related mortality. Therefore, it was believed that the REVIVED BCIS2 trial, with the lower perioperative risk associated with PCI, could equal or even exceed these benefits. However, things have changed since the publication of the STICH trial, including improvements in pharmacological therapy, greater use of devices such as implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy, closer follow-up of patients with heart failure, and widespread use of cardiac rehabilitation programs. The REVIVED BCIS2 trial proves that current OMT with the use of these resources in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy provides certain benefits regarding mortality and heart failure-related hospitalizations that are not enhanced by revascularization, at least with the percutaneous approach.

The most positive feature of this study is that it addresses an open question on the need for the systematic use of PCI in these patients and it does so with a methodologically appropriate clinical trial. The most debatable aspects are the definition of ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy and the achievement of complete revascularization. To characterize cardiomyopathy as ischemic, a BCIS-Jeopardy score4 ≥ 6 was required, with 49% of the patients having 2-vessel disease, while the median number of lesions and vessels treated per patient in the PCI group was 2, and complete revascularization was achieved in 71% of the patients.1

Q.: The STICH trial2 showed benefits beyond the 5- to 10-year mark, but in the REVIVED BCIS2 trial, the median follow-up was 3 to 4 years, although the patients’ age in the 2 studies was very different. What do you make of this?

A.: In the STICH trial, the all-cause mortality curves (primary endpoint) began to separate at the 2-year follow-up, and the original publication of the study, with a median follow-up of 4.7 years, failed to show a significant reduction in the primary endpoint. What demonstrated the prognostic benefit of cardiac surgery in addition to OMT was extending the follow-up to 10 years (median, 9.8 years).3 This reveals several points: on the one hand, the increased perioperative morbidity and mortality and, on the other hand, the long-term benefits of alleviating myocardial ischemia, leading, among other things, to lower rates of reinfarction and ventricular arrhythmias5 This is especially relevant when treating younger patients, whose lower surgical risk and longer life expectancy allow us to actually see clinical benefits. Although PCI was not associated with higher perioperative mortality in the REVIVED BCIS2 trial, there were no significant separations of the primary endpoint curves during the study.

We need to obtain data from a longer follow-up to detect any potential benefits associated with PCI. Additionally, the mean age of the REVIVED trial population was 70 years (compared with the median of 60 years in the STICH trial), making it less likely to achieve the same long-term benefits associated with surgical revascularization.

Q.: What was the clinical profile of these patients, and to what extent was their medical therapy optimized during randomization? Do you think they could have progressed to advanced stages of cardiomyopathy, and if so, could that have impacted the outcomes?

A.: The participants’ clinical profile was typical of this kind of disease. Most were men (88%), and 56% of them had a history of hypertension, 41% had diabetes, and 53% had previous myocardial infarction: 67% were angina-free, 20% had a history of previous PCI, and 5% had undergone surgical revascularization. They were in a favorable functional class (74% were in NYHA class I or II), while only 33% had been hospitalized due to heart failure in the previous 2 years, and the median N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) was 1400 pg/mL. Therefore, their baseline characteristics do not support the assumption that they were in an advanced stage of the disease.6 Although mortality during follow-up was high (32%), it was consistent with what we would expect of patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy,7,8 while the rate of heart failure-related hospitalizations was relatively low (15%). Based on their clinical profile, these patients would have been eligible for improvement with percutaneous revascularization. When the participants were randomized, 89% were on an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, combined with an angiotensin II receptor antagonist or sacubitril-valsartan, 91% were on beta-blockers, and 49% were on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Although this is a well-optimized regimen, there is still room for improvement, because only 5% of the participants were on sacubitril-valsartan, half of them were not on aldosterone antagonists, and sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors were not yet considered part of the foundational treatment of heart failure. Indeed, at the 2-year follow-up, only 20% were on sacubitril-valsartan and 55% were on mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists. Additionally, a low percentage of participants (23%) had a defibrillator or a cardiac resynchronizer.1

Q.: Do you agree that the trial questions the validity of viability tests? Although a 25% cutoff value for late gadolinium enhancement was established in cardiac magnetic resonance, in cases with 25% to 50% enhancement it was left to the local investigators’ discretion to use another imaging modality, such as dobutamine echocardiography. Do you think places doubt on the criteria applied to the trial?

A.: The STICH trial viability subanalysis already cast doubt on the utility of detecting a viable myocardium through single-photon emission computed tomography or dobutamine echocardiography to predict favorable outcomes after revascularization.9 The REVIVED BCIS2 also failed to demonstrate that viability-guided revascularization is able to reduce mortality or improve cardiac remodeling. In this trial, a larger number of dysfunctional—yet viable—myocardial segments were not associated with prognosis or with the possibility of improved ventricular function, whereas less myocardial scarring did predict a more favorable prognosis and a higher likelihood of reverse remodeling. This was independent of the baseline ejection fraction and extent of coronary artery disease.10 The results should prompt us to revisit the notion of hibernating myocardium and avoid basing the coronary revascularization strategy solely on viability tests.11 In this trial, cardiac magnetic resonance was the preferred imaging modality to assess viability (used in 71% of the patients). Considering segments with a maximum late enhancement of 25% as viable was a positive aspect, because participants with higher theoretical probabilities of improving after PCI were selected. Although another additional imaging modality could be used in patients with late enhancement between 26% and 50%, in practice, only 8 patients1 received more than 1 viability test, so this does not seem to be an important point.

Q.: Considering the possibility that coronary artery disease can be concurrent with cardiomyopathy, without it necessarily being the main cause, do you think there is a specific patient profile that could benefit from PCI or, at the very least, could be worth further study?

A.: The subgroup analysis did not show any significant treatment interaction in the prespecified subgroups of interest.1 However, data from the study allow us to speculate on which participants might benefit more from PCI. The trial included few patients with limiting angina, thus making the findings less applicable to these patients. The study showed differences in favor of PCI regarding quality of life at the 6- and 12-month follow-up (becoming equal at 2 years in the 2 groups), suggesting that PCI might be crucial for patients with angina.5 Additionally, PCI-treated patients showed a trend toward fewer appropriate implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapies,1 indicating that revascularization could be more beneficial in individuals in whom ventricular arrhythmias are an issue. Other subgroups of interest would be patients with more extensive coronary artery disease, those with complete revascularization, and those with greater ventricular dysfunction. Future publication of these patients’ outcomes could help in the decision-making process.6

Finally, while surgical revascularization should be the preferred strategy for patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy,7 PCI should still play a role in the management of young patients with significant coronary artery disease and high surgical risk or poor distal beds. With the current evidence available and contemporary OMT, a clinical trial should be conducted comparing 3 therapeutic strategies: isolated OMT, OMT along with surgical revascularization, and OMT alongside PCI in patients with ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. The selection criteria should not consist of viability but rather the feasibility of achieving complete myocardial revascularization in regions at-risk, and follow-up should be long-term.

FUNDING

None reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

1. Perera D, Clayton T, O'Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1351-1360.

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Deja MA, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1607-1616.

3. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-Artery Bypass Surgery in Patients with Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1511-1520.

4. Morgan H, Ryan M, Briceno N, et al. Coronary Jeopardy Score Predicts Ischemic Etiology in Patients With Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. J Invasive Cardiol.2022;34:E683-E685.

5. Ezad SM, Ryan M, Perera D. Can Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Revive a Failing Heart?Heart Int. 2022;16:72-74.

6. Vergallo R, Liuzzo G. The REVIVED BCIS2 trial:percutaneous coronary intervention vs. optimal medical therapy for stable patients with severe ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4775-4776.

7. Liga R, Colli A, Taggart DP, Boden WE, De Caterina R. Myocardial Revascularization in Patients With Ischemic Cardiomyopathy:For Whom and How. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e026943.

8. Perera D, Clayton T, Petrie MC, et al. Percutaneous Revascularization for Ischemic Ventricular Dysfunction:Rationale and Design of the REVIVED BCIS2 Trial:Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Ischemic Cardiomyopathy. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:517-526.

9. Bonow RO, Maurer G, Lee KL, et al. Myocardial viability and survival in ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1617-1625.

10. Perera D. Effect of Myocardial Viability, Functional Recovery and ICP on Clinical Outcomes in the REVIVED BCIS2 Trial. En:American College of Cardiology 2023 Scientific Session;2023 March 4-6;New Orleans, LA, USA. Available at: https://accanywhere.acc.org/media/c2f4157c-0bef-4d69-87b4-ac6ab6224e07. Accessed 9 Jul 2023.

11. Ryan M, Morgan H, Chiribiri A, Nagel E, Cleland J, Perera D. Myocardial viability testing:all STICHed up, or about to be REVIVED?Eur Heart J. 2022;43:118-126.RECIC_23_064

QUESTION: What is your opinion of the REVIVED BCIS2 trial? Which, would you say, are its most positive and most debatable features?

ANSWER: The REVIVED BCIS21 is a prospective, multicenter, randomized, open-label trial of stable patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction (left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF] ≤ 35%), extensive coronary artery disease with a British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) risk score ≥ 6, and evidence of viability in at least 4 dysfunctional segments amenable to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive PCI along with optimal medical therapy (OMT), or OMT alone. The OMT included pharmacological therapy and implantable devices for the management of heart failure.

The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality or hospitalization over a minimum follow-up of 24 months. Secondary endpoints included 6- and 12-month echocardiographic measurements of LVEF (core lab), quality of life measurement through questionnaires such as the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire, the EuroQol Group 5-Dimensions 5-Level Questionnaire, and New York Heart Association Functional Class, cardiovascular death, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), appropriate defibrillator therapy (antitachycardia pacing or shock), unplanned revascularization, brain natriuretic peptide values, functional class, and major bleeding.

A total of 700 patients were included, of which 347 were randomized to PCI and 353 to OMT. The participants’ mean age was 69 years, and 12% were women. The median follow-up was 41 months (importantly, randomization began back in 2013 and the study was published in 2022), and 40 hospitals in the United Kingdom participated in the trial. The participants received guideline-directed pharmacological therapy (93% received beta-blockers; 66% angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, and 56% aldosterone antagonists). More than 30% of the participants in the 2 groups received a defibrillator or resynchronization device before or during the study period.

The primary endpoint was observed in 37.2% of the PCI group and 38% of those in the OMT group. LVEF was similar in the 2 groups both at 6 and 12 months. Although quality of life questionnaires favored PCI at 6 and 12 months, this improvement was attenuated at 24 months.

I believe the main strength of the study is that it is the first to compare this revascularization mode (PCI) with OMT in ischemic patients with LVEF ≤ 35%. Previously, we only had the STITCH2 trial for this patient subgroup, which compared coronary revascularization surgery with OMT in a population of younger patients with less extensive coronary artery disease. This trial did not show any benefits associated with surgery in terms of overall 5-year mortality but did show benefits at the extended 10-year follow-up. Another important point is the efficacy of OMT in these patients today; in fact, the number of events was even lower than initially anticipated by the investigators.

Regarding debatable aspects, I’d say that, although the patients were selected on the basis of myocardial viability; until now viability testing has never been used to predict the effectiveness of revascularization.2,3 And to be honest, it may not be the most suitable way to identify patients who will benefit from PCI in this population.4 Additionally, most patients were asymptomatic (66%) or showed mild angina symptoms, which could undoubtedly have impacted the results.

Q.: What was the patients’ coronary artery disease profile? What do think of the use of an angiographic risk index like the BCIS in this trial compared with alternatives like the SYNTAX score, and especially functional assessment using pressure guidewires? How far do you think the causal relationship between coronary artery disease and dilated cardiomyopathy was clear?

A.: Compared with the STITCH2 trial, the REVIVED BCIS21 trial included older patients with more extensive coronary artery disease and more contemporary medical treatment. However, the assessment of disease extent and the significance of coronary involvement according to the BCIS5 score raises some questions. In fact, it’s surprising that despite having mean scores of 10, almost half of the participants had 2-vessel disease, and the median number of vessels and lesions treated was 2,6 which raises concerns about how many lesions were not revascularized. Also, it is unclear whether there could have been some selection bias, because some participants with more extensive coronary artery disease amenable to surgery might have been referred directly and not included in the study.

On the other hand, it seems obvious that lesion assessment with pressure guidewires would have provided the study with significant reliability. If we look at the BCIS score, lesions are defined as severe when stenosis is > 70%. Especially in a population of mostly asymptomatic patients or those with mild angina symptoms and multivessel disease, it seems more than reasonable to select target lesions and vessels based on coronary physiology assessment.

Q.: What can you tell us about revascularization? Could the degree of complete revascularization or crossing over from OMT to PCI have impacted the results?

A.: As I mentioned, despite having extensive coronary artery disease according to the angiographic scale used, almost half of the participants had 2-vessel disease, and the median number of treated lesions was 2. Additionally, the authors mention that they have not yet analyzed whether the target vessels coincided with segments of affected viability, complicating interpretation of the results even more. Undoubtedly, if some lesions were left untreated while others without indications were indeed treated, the impact on the results is obvious. Also, as you mentioned in your question, unplanned revascularization was more frequent in the OMT group (10.5%) than in the PCI group (2.9%), which could explain why the PCI group showed better quality of life scores at 6 and 12 months, but not at 24 months when the impact of the higher rate of unplanned revascularizations in the OMT group may have been a factor.

Q.: Were there any benefits seen in any type of clinical event in the PCI group?

A.: Yes. The PCI group experienced fewer episodes of ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation than the OMT group, suggesting a lower ischemic burden and arrhythmic risk in the OMT group. Additionally, the number of defibrillators implanted after randomization was lower in the PCI group.

On the other hand, although the incidence of AMI was similar in the 2 groups (around 10%), almost half were perioperative in the PCI group, whereas none were perioperative in the OMT group, resulting in more spontaneous AMIs in the OMT group (9% vs 5%). This datum might be clinically relevant because the ISCHEMIA trial7 revealed that spontaneous AMIs have a worse prognosis than perioperative AMIs.

As I mentioned previously, the PCI group also benefitted in terms of quality of life at 6 and 12 months, but not at 24 months.

Q.: Bearing in mind that coronary artery disease may have a causal relationship with cardiomyopathy, do you think there is a particular patient profile that could benefit from PCI or, at the least, merit further investigation of this link?

A.: Based on the REVIVED trial results, it’s obvious that percutaneous revascularization in stable patients with severe LVEF depression, multivessel disease, and few or no angina symptoms provides little benefit. If we remember that lesion selection was purely angiographic (lesions with stenosis ≥ 70%), and that we just don’t know if the treated lesions coincided with segments of abnormal viability, patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction, angina symptoms, angiographically significant lesions, and abnormal coronary physiology assessments (or left main coronary artery intravascular ultrasound assessments)8 may constitute a group that could benefit from coronary angioplasty in terms of survival and quality of life.

FUNDING

None reported.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

1. Perera D, Clayton T, O'Kane PD, et al. Percutaneous revascularization for ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med.2022;387:1351-1360.

2. Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med.2016;374:1511-1520.

3. Cleland JG, Calvert M, Freemantle N, et al. The heart failure revascularisation trial (HEART). Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:227-233.

4. Ryan M, Morgan H, Chiribiri A, Nagel E, Cleland J, Perera D. Myocardial viability testing:all STICHed up, or about to be REVIVED?Eur Heart J. 2022;43:118-126.

5. Perera MA, Stables R, Booth J, et al. The Balloon pump-assisted Coronary Intervention Study (BCIS-1):Rationale and design. Am Heart J. 2009;158:910-916.

6. Vergallo R, Liuzzo G. The REVIVED-BCIS2 trial:percutaneous coronary intervention vs. optimal medical therapy for stable patients with severe ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:4775-4776.

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial invasive or conservative strategy for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

8. De Maria GL, Testa L, de la Torre Hernandez JM, et al. A multi-center, international, randomized, 2-year, parallel-group study to assess the superiority of IVUS-guided PCI versus qualitative angio-guided PCI in unprotected left main coronary artery (ULMCA) disease:Study protocol for OPTIMAL trial. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0260770.

QUESTION: Is there, currently, enough clinical evidence to recommend the use of cerebral protection in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)?

ANSWER: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become the treatment of choice of severe aortic stenosis in patients with some degree of surgical risk involved. Perioperative stroke is a serious complication associated with a dramatic reduction of the patient’s quality of life and, occasionally, with a lower mid-term survival rate. Although the rate of clinical stroke is relatively low (between 2% and 7%, according to the different series published)1, rates of silent cerebral infarction after TAVI of up to 70% have been described, which has been associated with the appearance of progressive cognitive decline at follow-up2. To prevent these adverse events from happening, different cerebral embolic protection devices (CEPD) have been created over the past few years. However, despite several randomized clinical trials conducted, no proven net clinical benefit has been confirmed regarding lower rates of clinical stroke. In the DEFLECT III trial3 using the Triguard device (Keystone Heart Ltd., Israel), Lansky et al. obtained a successful CEPD implantation rate of 88.9% without any differences being reported regarding the safety endpoint, and a tendency towards more new-onset brain injuries (26.9% vs 11.5%) but with less neurological deficit (3.1% vs 15.4%) in the device group. The MISTRAL-C4 trial4 on the Sentinel device (Claret Medical Inc., United States) did not achieve its primary endpoint and found no significant differences in the percentage of patients with new-onset brain injuries in both groups. That same year, the CLEANTAVI trial5 on imaging modality-guided Sentinel devices before and after the procedure, confirmed the presence of fewer and smaller brain injuries in the CEPD group (242 mm2 vs 527 mm2; P < .001). However, no significant differences were found regarding fewer clinical strokes. The SENTINEL IDE trial6 published back in 2017 met its safety endpoint (100% technical success rate). However, no significant differences were found regarding clinical events (major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events: 7.3% vs 9.9%; P = .40) or volume of new-onset brain injuries (103 mm2 vs 178 mm2; P = .33). However, a lower rate of early stroke (3% vs 8.2%; P = .05) was reported in the CEPD group. More recently, the REFLECT II trial7 on the Triguard 3 device showed a non-significant higher rate of bleeding and major vascular complications associated with TAVI in the CEPD group. Also, no significant differences were found in the efficacy endpoint between both groups (30-day rate of mortality or stroke, worsening of the NIHSS score, and presence of new-onset brain injuries on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging between the second and fifth days). Finally, in the anticipated PROTECTED TAVR trial8 the authors concluded that the use of the Sentinel device (Boston Scientific, United States) during TAVI via femoral approach did not have a significant impact on the rate of perioperative stroke. Therefore, in light of the results obtained from different studies published so far, there is not enough clinical evidence to support the routine use of CEPD during TAVI.

Q.: What do you make of the PROTECTED TAVR trial?

A.: Although the SENTINEL IDE trial6 showed a secondary endpoint of fewer clinical strokes within the first 72 hours after the procedure (3% vs 8.2%; P = .05), it lacked the statistical power needed to assess this variable. To confirm this hypothesis, the PROTECTED TAVR clinical trial8 was conducted. This is a prospective and multicenter study that randomized 3000 patients with severe aortic stenosis who were going to be treated with TAVI via femoral accees into 2 groups: the Sentinel CEPD group or the control group. The primary efficacy endpoint was the occurrence of a clinical stroke within the first 72 hours after the procedure or until hospital discharge whatever came first. Cerebral imaging modalities were spared only for patients with neurological deficits after TAVI. The rate of clinical stroke was 2.6% (2.3% in the CEPD group vs 2.9% in the control group; P = .30). The rate of non-disabling stroke was 1.7% in the CEPD group compared to 1.5% in the control group (P = .67) while the rate of disabling stroke was 0.5% of the CEPD group vs 1.3% in the control group (P = .02). The device efficacy and safety rates were 94.4% and 99.9%, respectively. Therefore, after a detailed analysis of the study, we can conclude that there is no significant benefit associated with the use of CEPD to reduce the rate of clinical stroke after TAVI. No subgroups of patients were identified either who could benefit from their use. Although the safety profile of the device appears excellent, the associated financial cost and the low benefit derived from it with a number needed to treat regarding total stroke and disabling stroke of 166 and 125 patients, respectively, make the routine use of CEPD in TAVI ill-advised. It seems obvious that both the etiology and pathophysiology of stroke in this context are multifactorial. Therefore, we should not expect that devices that only act as a barrier mechanism will significantly reduce these types of events that occur not only during TAVI but also within the next 72 hours following the procedure. Additionally, the greater experience gained by interventional cardiology units, the precision of imaging techniques, the thorough analysis of each case before the procedure, the progressive reduction of device profiles, and the decreasing complexity of the implantation technique are all factors that could contribute to reduce the rate of stroke associated with TAVI.

Q.: Do you consider the use of cerebral protection devices in some kind of patients or in no patients at all?

A.: To this date, scientific evidence has not yet been able to establish which subgroup of patients eligible for TAVI may have a higher risk of having a stroke and, therefore, would benefit more from the use of CEPD. Although factors associated with the procedure that could increase the risk of stroke during TAVI have been described (pre- or postdilatation maneuvers, valve-in-valve procedures, smaller native aortic valve areas, higher valve gradients, severe valve calcification, bicuspid valve morphology, aortic atheromatous disease)9, it remains controversial since former studies have shown that several of these factors don’t seem to predispose to having a stroke after TAVI. Makkar et al.10 found no statistically significant differences regarding the morphology of bicuspid or tricuspid valve between the rates of mortality (0.9% vs 0.8%; P = .55) and stroke (1.4% vs 1.2%; P = .55) at 30 days in a series of low surgical risk patients. In the PROTECTED TAVR trial8 no significant differences were seen either regarding the use of CEPD in the subgroup analyses including the variables age, sex, STS-PROM (Society of Thoracic Surgeons Predicted Risk Of Mortality) surgical risk score, surgical risk assessed by the heart team, bicuspid or non-bicuspid morphology of the aortic valve, degree of aortic annular calcification, past medical history of coronary artery disease, peripheral arterial disease, stroke, previous valve-in-valve procedure, use of balloon-expandable valves, pre- and postdilatation.

Personally, I would say that patients with significant atheromatous disease in the ascending and thoracic aorta, and those undergoing valve-in-valve procedures with aggressive postdilatation maneuvers (annular fracture) could be subgroups where the use of DPEC could reduce the rate of perioperative stroke. It seems necessary to keep on conducting in-depth retrospective studies on potential predisposing factors thoroughly in patients who have suffered a stroke with or without clinical implications after TAVI before establishing subgroups of higher risk of stroke during implantation.

Q.: Are there any evidence-based differences regarding the type of devices used?

A.: Currently, we have 2 DPEC available with CE marking: the Sentinel and the Triguard 3. The former, on which we have more clinical experience, consists of 2 connected nitinol filters that independently seal the brachiocephalic trunk and the left carotid artery for particles ≥ 140 μm. The system is advanced from the right radial artery using a 6-Fr delivery catheter mounted over a 0.014 in guidewire. The Triguard 3 consists of a self-positioning nitinol structure arranged as a net that is advanced over a 0.035 in exchange guidewire via femoral artery using an 8-Fr delivery catheter. As a potential advantage over its competitor, it protects all 3 vessels (including the left subclavian artery too), thus preventing the passage of particles ≥ 145 μm. Similarly, its design allows us to advance a pigtail catheter through the same introducer without having to cannulate additional vascular accesses. Recently, the results of the PROTEMBO C trial11 on the ProtEmbo device (Protembis GmbH, Germany) have been published. This device consists of a 38 mm × 70 mm self-expanding nitinol mesh inserted via left radial or brachial artery through a 6-Fr catheter mounted over a 0.014 in guidewire. With it we can protect all 3 cerebral vessels by capturing particles ≥ 60 μm. In the 37 patients finally included in the study, the device implantation success rate was 94.5%. Only 1 thalamic stroke was documented in a patient in whom the DPEC was removed prematurely due to significant interaction while TAVI was being performed. Regarding subclinical strokes, diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging found a mean volume of new-onset lesions of 210 mm3 (undetected in 97% of the patients with lesions with volumes > 350 mm3). Currently, no studies comparing the different DPEC available today have been conducted so there is no evidence to recommend the use of 1 device to the detriment of the others. Perhaps the emergence of DPEC with high device implantation success rates, no associated vascular complications, and protection of all 3 major cerebral vessels, preventing the passage of smaller particles could contribute to reducing the rate of perioperative stroke.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

P.L. Martín Lorenzo is a proctor for Myval (Meril Life).

REFERENCES

1. Huded CP, Tuzcu EM, Krishnaswamy A, et al. Association between transcatheter aortic valve replacement and early postprocedural stroke. JAMA. 2019;321:2306-2315.

2. Woldendorp K, Indja B, Bannon PG, et al. Silent brain infarcts and early cognitive outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1004-1015.

3. Lansky AJ, Schofer J, Tchetche D, et al. A prospective randomized evaluation of the TriGuardTM HDH embolic DEFLECTion device during transcatheter aortic valve implantation: results from the DEFLECT III trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2070-2078.

4. Van Mieghem NM, van Gils L, Ahmad H, et al. Filter-based cerebral embolic protection with transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the randomised MISTRAL-C trial. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:499-507.

5. Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:592-601.

6. Kapadia SR, Kodali S, Makkar R, et al. Protection against cerebral embolism during transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:

367-377.

7. Nazif TM, Moses J, Sharma R, et al. Randomized evaluation of TriGuard 3 cerebral embolic protection after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (REFLECT II). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:515-527.

8. Kapadia SR, Makkar R, Leon M, et al. Cerebral embolic protection during transcatheter aortic valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1253-1263.

9. Armijo G, Nombela-Franco L, Tirado-Conte G. Cerebrovascular events after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;

5:104.

10. Makkar RR, Yoon SH, Chakravarty T, et al. Association between transcatheter aortic valve replacement for bicuspid vs tricuspid aortic stenosis and mortality or stroke among patients at low surgical risk. JAMA. 2021;326:

1034-1044.

11. Jagielak D, Targonski R, Frerker C, et al. Safety and performance of a novel cerebral embolic protection device for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the PROTEMBO C Trial. Eurointervention. 2022;18:590-597.

QUESTION: Do you think that there is, currently, any evidence behind the use of cerebral protection devices in transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)?

ANSWER: Former studies described that, during TAVI, loose debris like arterial wall fragments, thrombi, valve tissue, and foreign bodies often enters the circulation.1 These particles are the aftermath of the device making its way through the aorta towards the aortic annulus, the positioning and displacement of a calcified stenotic valve between the new valve stent and the aortic wall, and further manipulations to optimize results (postdilatation). To this date, numerous studies have been published on the safety and efficacy profile of these cerebral protection devices (CPD). Specifically, 4 randomized clinical trials have been published associated with the SENTINEL (Boston Scientific Corp., United States): MISTRAL-C,2 CLEAN TAVI,3 SENTINEL,4 and PROTECTED TAVR5 we can talk about later on. The MISTRAL-C trial used cerebral magnetic resonance imaging to demonstrate a significant reduction in the number of patients with multiple cerebral lesions (20% vs 0%; P = .03) and less cognitive impairment (4% vs 27%; P = .017). Similarly, the CLEAN TAVI trial also reported fewer novel lesions and of a smaller volume without any differences being reported in the number of clinical events in the group that used CPD. These studies demonstrated fragments being captured in almost in 100% of the cases. Several metanalyses6-13 also confirm these results regarding the number and volume of cerebral lesions described, and even some show lower rates of strokes in the DPC group.10,12,13 Therefore, we not only have the visual in situ demonstration of the particles being captured in the baskets following implantation, but also scientific evidence that CPD are effective capturing fragments released during TAVI that can land in cerebral circulation, thus lowering the number of cerebral lesions found on the magnetic resonance imaging during the procedure. However, whether capturing such particles with the device has a clear clinical benefit for its widespread use is still to be elucidated.

Q.: What do you make of the PROTECTED TAVR trial?

A.: The PROTECTED TAVR5 was a multicenter randomized trial that included a total of 3000 patients treated with TAVI and randomized on a 1:1 ratio to undergo the procedure with or without a CPD (control group). The study primary endpoint was to assess the rate of strokes 72 hours after TAVI or before discharge, whatever came first, and the difference was not significant between the 2 groups (absolute difference, −0.6%; relative difference, −20.7%). However, in 1 of the 15 secondary endpoints, the rate of disabling strokes dropped significantly in the CPD group (0.5% vs 1.3% in the control group). The number needed to treat to prevent an disabling stroke was 125 patients. This study has its pros and cons. Its main strength is that neurological examinations were conducted before and after TAVI, and events were adjudicated by an independent event adjudication committee.14 However, these examinations were not always conducted by expert neurologists. Also, no imaging modalities were systematically performed on all the patients, thus leading to misdiagnosed asymptomatic strokes. We should mention that hemorrhagic strokes were also included. However, they were only found in 2 patients from each group. The study main weakness is that the size of the sample was estimated to have a rate of strokes of 4%. However, the actual rate of strokes of the control group was much lower than expected (2.9%). A reason that may explain the low rate of strokes reported in the control group is the risk profile of the patients included. In this study, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) mean score in the control group was 3.4 ± 2.8. Also, over 50% of the patients included in both groups had STS scores < 3 meaning that they were low-risk patients. The results of the PROTECTED TAVR trial do not provide scientific evidence for the systematic use of cerebral protection devices. However, we should mention that, across the years, the improvements made in both the TAVI implantation technique and the design of the devices used haven’t reduced the rate of strokes significantly.15 It’s plain to see that the rate of strokes of the different studies conducted drops because the risk profile of the patients included is better. However, if the SENTINEL device eventually manages to reduce the rate of disabling strokes in low-risk patients, we’d be reducing the occurrence of one of the most dreaded complications for patients treated with TAVI both due to the increased mortality associated and the greater morbidity it adds on the patient who, on many occasions, becomes disabled. However, not everything has been said and done in this field. The results of the BHF Protect TAVI randomized clinical trial are still pending.16 It is still recruiting patients and will include twice the number of patients since the size of the sample was estimated for a rate of strokes in the control group of 3%, something more in tune with the actual rate of patients treated with TAVI. There are still unsolved issues like what impact CPD have on patients with high risk of stroke and whether the protective effect of CPD treating asymptomatic cerebral lesions is associated with the patients’ cognitive function in both the mid- and long-term.17

Q.: Are you for a widespread use of cerebral protection devices or do you think that some patients are more eligible than others?

A.: To this date, with the results currently available, there is no robust scientific evidence backing the systematic use of CPD in patients treated with TAVI. I think that those who would benefit the most from this kind of devices are individuals with a higher risk of stroke like patients with previous strokes, renal injuries, bicuspid aortic valves, severe aortic valve calcification and valve-in-valve procedures, porcelain aorta, and young patients.15,18 Also, patients with thrombi in the left atrial appendage or fibroelastoma or loose material dependent on the aortic leaflets or ascending aorta that could embolize during predilatation or valve implantation.

Q.: What are the main differences of the devices currently available?

A.: The 2 devices currently available in Spain are the SENTINEL and the TriGUARD (Keystone Heart Ltd, Israel). The main differences between the 2 are:

- – Access route: the SENTINEL devices always uses a 6-Fr right radial access, and the TriGUARD a 8-Fr access route.

- – The degree of protection of supraaortic trunks: the SENTINEL device protects the brachiocephalic trunk and the left carotid artery only sparing the left subclavian artery. However, the TriGUARD device protects all 3 supraaortic trunks.

- – Anatomical limitations regarding implantation: the SENTINEL device requires brachiocephalic trunk and left carotid artery diameters of 9 mm to 15 mm and 6.5 mm to 10 mm, respectively, and no tortuosity or severe stenosis in the 3 cm from the ostia of the vessels. Also, there are certain anatomical variants of supraaortic trunks that, though rare, would contraindicate its use. Therefore, a computed tomography scan including supraaortic trunks is advised to measure and assees the anatomy and see if device implantation is feasible. Regarding the TriGUARD, the anatomical limitations are iliac artery and abdominal artery diameters > 3.7 mm and > 10 mm, respectively, a distance < 76 mm from the femoral head up to 3 cm to 4 cm beyond the brachiocephalic trunk (this measurement complies with almost 100% of the population in our country), and the so-called «security gap» consisting of a distance > 65 mm between the aortic annulus and the ostium of the brachiocephalic trunk to make sure that the device does not interfere with TAVI.

- – The SENTINEL device captures particles in its filter baskets while the TriGUARD does not. Instead, it steers them towards the descending aorta.

- – Finally, another significant difference is that the TriGUARD device does not protect the coronary arteries from the radial access. If there is risk of coronary occlusion during TAVI, 2 different ipsilateral femoral accesses plus the therapeutic one should be used. This is not the case with the SENTINEL device because the left radial access can be used, if necessary,

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Kawakami R, Gada H, Rinaldi MJ, et al. Characterization of cerebral embolic capture using the SENTINEL device during transcatheter aortic valve implantation in low to intermediate-risk patients: the SENTINEL-LIR study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e011358.

2. Van Mieghem NM, van Gils L, Ahmad H, et al. Filter-based cerebral embolic protection with transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the randomised MISTRAL-C trial. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:499-450.

3. Haussig S, Mangner N, Dwyer MG, et al. Effect of a cerebral protection device on brain lesions following transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis: the CLEAN-TAVI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316:592-601.

4. Kapadia SR, Kodali S, Makkar R, et al. Protection against cerebral embolism during transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;

69:367-377.

5. Kapadia SR, Makkar R, Leon M, et al. Cerebral Embolic Protection during Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement. N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1253-1263.

6. Giustino G, Mehran R, Veltkamp R, et al. Neurological outcomes with embolic protection devices in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2124-2133.

7. Pagnesi M, Martino EA, Chiarito M, et al. Silent cerebral injury after transcatheter aortic valve implantation and the preventive role of embolic protection devices: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016;221:97-106.

8. Bagur R, Solo K, Alghofaili S, et al. Cerebral embolic protection devices during transcatheter aortic valve implantation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2017;48:1306-1315.

9. Giustino G, Sorrentino S, Mehran R, et al. Cerebral embolic protection during TAVR: a clinical event meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:

465-466.

10. Mohananey D, Sankaramangalam K, Kumar A, et al. Safety and efficacy of cerebral protection devices in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a clinical end-points meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2018;19(7 Pt A):

785-791.

11. Wang N, Phan K. Cerebral protection devices in transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a clinical meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:1927-1935.

12. Testa L, Latib A, Casenghi M, et al. Cerebral Protection During Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008463.

13. Ndunda PM, Vindhyal MR, Muutu TM, Fanari Z. Clinical Outcomes of Sentinel Cerebral Protection System Use During Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;2:717-722.

14. Carroll JD, Saver JL. Does Capturing Debris during TAVR Prevent Strokes? N Engl J Med. 2022;387:1318-1319.

15. Vlastra W, Jimenez-Quevedo P, Tchétché D, et al. Predictors, Incidence, and Outcomes of Patients Undergoing Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Complicated by Stroke. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;

12:e007546.

16. Kharbanda RK, Perkins AD, Kennedy J, et al. Routine cerebral embolic protection in transcatheter aortic valve implantation: rationale and design of the randomised British Heart Foundation PROTECT-TAVI trial. EuroIntervention. 2023;EIJ-D-22-00713.

17. Woldendorp K, Indja B, Bannon PG, Fanning JP, Plunkett BT, Grieve SM. Silent brain infarcts and early cognitive outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1004-1015.

18. Armijo G, Nombela-Franco L, Tirado-Conte G. Cerebrovascular Events After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2018;5:104.

- Debate. Revascularization of nonculprit lesions in ACS: physiology or OCT-guided or both? Perspective from imaging

- Debate: Revascularization of non-culprit lesions in ACS: physiology, OCT-guided or both? Perspective from physiology

- Debate. Drug-coated balloons for de novo coronary artery lesions. Still not enough evidence, and the new drug-eluting stents are still better

- Debate. Drug-coated balloons for de novo coronary artery lesions. Evidence available and potential superiority in some settings

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

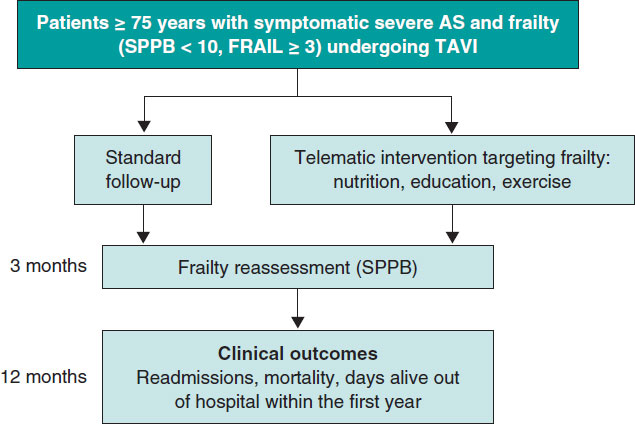

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España