Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: What is the current status of percutaneous coronary interventions to treat functional mitral regurgitation (MR)?

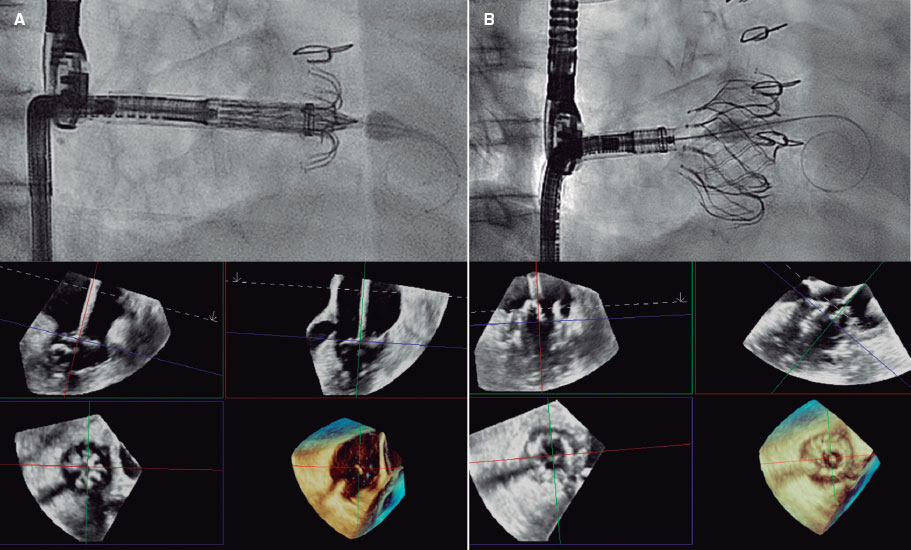

ANSWER: To this date, transcatheter mitral valve repair therapies are backed by the highest scientific evidence. This has been confirmed by the new clinical practice guidelines1 on the management of patients with valve disease published by the American Heart Association (AHA) where transcatheter repair (class IIa-Level of Evidence BR) is recommended for patients with functional MR and severe ventricular dysfunction. However, surgery is spared for cases that require concomitant coronary revascularization. We should not forget that transcatheter repair is the only technique on which there are randomized clinical trials available.2,3 That is why it is indicated as the first-line therapy by the clinical practice guidelines. We should put the old sayings «regarding a case» or «in my hands, results are better» to sleep. Multicenter randomized clinical trials assess the reproducibility of the technique, and that is the key to generalize this or that therapy. In my opinion, the clinical cardiologist should place transcatheter mitral valve repair in the same level as cardiac resynchronization therapy. And, same as it happens with resynchronization, the right selection of patients is of paramount importance. When should repair be considered? In patients on optimal medical therapy who still remain symptomatic with severe functional MR, ventricular dysfunction, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter ≤ 70 mm, and with a suitable valvular anatomy as seen on the transesophageal echocardiography.

Q.: In your opinion, which would be the potential niche to combine techniques that target the leaflets or the annulus in this context?

A.: Winston Churchill used to say: « However beautiful the strategy, you should occasionally look at the results». Combined therapy is a very appealing idea, yet the experienced reported on this procedure is very limited with very few cases published to this date. It has probably encountered 2 main limitations so far: edge-to-edge mitral valve repair can alter the anteroposterior diameter of the mitral annulus and has a 5-year durability time limit compared to surgery; on the other hand, the combined procedure significantly increases risk, complexity, and the cost of the procedure.

With this mind and taking into consideration that in the future low-risk patients with primary MR will be treated, it is likely that we’ll be seeing more reports on combined cases always with the objective of increasing the repair durability.

Q.: What does interventional cardiology have to offer to patients with organic MR who are not eligible for surgery? And what about the mitral annulus?

A.: The main advantage for patients with many comorbidities is that with transcatheter repair recovery is almost immediate (to this date, the average hospital stay is 48 hours) and the rate of complications is very low; the worst thing that can happen is unsuccessful repairs. That is why the main limitation is the impossibility of valvular replacement conversion with suboptimal results (actually something cardiac surgery allows).

Mitral annular calcification does not exclude transcatheter repair, but it can make it difficult due to the presence of less flexible leaflets, thus predisposing to a higher risk of leaflet tear and a greater final transmitral gradient. However, the wide array of devices available allows us to take on situations that we would have discarded in the past. In any case, this seems like the most interesting niche for transcatheter mitral valve repair.

Q.: What degree of clinical development have transcatheter mitral valves reached so far? In your opinion, which should be their indication with respect to repair techniques?

A.: The first series with over 100 patients have already been published with positive results.4 The main limitation here is the excessive selection of patients to guarantee positive results and avoid complications like left ventricular outflow tract obstruction. Over 60% of the patients assessed are eventually considered not eligible to undergo the procedure. Regarding the indication, for the time being, it should be spared for patients in whom the repair is not feasible or may be difficult. We still need data on valvular dysfunction and thrombosis at the follow-up.

Q.: Tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is a complex condition of often unsatisfactory management. What techniques are already available for the interventional cardiologist?

A.: That is true. Unfortunately, the mortality rate of isolated surgery on the tricuspid valve is high; actually, even higher regarding its repair (mortality rate > 10%). On the other hand, medical therapy is often limited by renal function. Also, if we consider that most TRs are functional, it seems like a perfect disease to use transcatheter techniques. That is why several devices we use nowadays to treat the mitral valve are also valid to treat tricuspid regurgitation.

For repair purposes, in the MitraClip device (Abbott Vascular, United States) the delivery sheath has been changed to approach the valve easier. The Triluminate study5 used this version of the device (Triclip), and confirmed that TR was reduced by, at least, 1 grade in 86% of the patients with a 4% rate of adverse events at the 6-month follow-up. This possibility is also being explored with the Pascal device6 (Edwards Lifesciences, United States), primarily with its ACE version, and the early results are similar to those published on the Triclip. The Cardioband7 (Edwards Lifescience, United States) is also available for this use and the early experience with 30 patients reduced TR to less than moderate in 73% of the patients at the 6-month follow-up

On the other hand, the field of tricuspid valve replacement is clearly heading towards the use of the femoral access almost exclusively (currently, in the mitral valve, the most consolidated valve is the Tendyne [Abbott, United States] that is implanted via transapical access). Many of the valves intended for the mitral valve are also being used in the tricuspid one where right ventricular outflow tract obstruction does not seem be a problem.

Finally, we also have heterotopic valves available that are implanted outside the thoracic cavity. The main advantage of these devices is a relatively easy implantation, and the fact that they can be used when the etiology of TR is interference with wires coming from other devices such as pacemakers, automatic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators, etc.

Q.: Which is the optimal clinical indication and anatomical context to use these techniques?

A.: The main clinical indication is patients with severe TR with signs or symptoms of right congestion that are persistent despite medical therapy and without signs of severe pulmonary arterial hypertension. In our case, the typical subject is a patient operated on the mitral valve (probably due to atrial fibrillation) who has been dilating the tricuspid annulus for years and now has severe TR that he did not have when he underwent surgery.

With respect to the anatomical context, maybe the main limiting factor regarding repairs is the echocardiographic window. It is important to know whether we will be able to achieve good projections to guarantee a proper device implantation. There are times that multimodal images including transthoracic, transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiography are required. The main limitation of edge-to-edge repair devices is the size of coaptation defect (in the Triluminate, the cut-off value was 2 cm, but the truth is that in defects > 1 cm it is already assumed that we’ll be needing more than 1 device), and in the case of the Cardioband the size of the annulus should be < 52 mm. Regarding valves, screening is performed through computed tomography scan and the limiting factor here is often the annular size. Heterotopic valves usually have very few limiting criteria.

Q.: What does the future of interventional cardiology have in store with respect to heart surgery? Where should we look into from one specialty and the other?

A.: From the medical point of view, we should probably not pay too much attention to which is the possible survival rate of this or that specialty, but where is the therapy heading to. Today’s medicine favors prevention over intervention, and the least invasive procedures over the most aggressive ones. For example, let’s look at the evolution surrounding the management of rheumatic mitral stenosis. We went from open commissurotomy as the early therapy to percutaneous valvuloplasty when it became available. However, thanks to early antithrombotic treatment there are fewer cases of mitral stenosis. This is the same path we should expect to follow with the remaining valve diseases we treat today.

We should focus on obtaining the most effective treatments causing the least possible damage to the patients. Therefore, it is our responsibility to work in order to a) use the least invasive access routes to boost the patients’ early recovery; b) minimize the impact of the learning curve of this or that therapy through early focus and the proper dissemination; c) consistently assess the results of a new therapy while being patient at the same time (and not trying to know if it is effective with the first 10 cases at the 1-month follow-up); d) be actively involved in improving the procedures (whether through patient selection, device improvement or further medical management); and finally as Hippocrates used to say «foolish the doctor who despises the knowledge acquired by the ancients», in other words, let us benefit from the cumulative experience acquired over time to avoid making the same mistakes over again.

Once a therapy has become consolidated the proper training criteria should be established to be able to perform it, which leads us directly to accreditation. The proper criteria should be established and then incorporated to the proper training, and the corresponding legal validity achieved for accreditation purposes. This can be extrapolated to all the super-specialties within the different fields of medicine. Training is well regulated from college throughout the Internal Medicine Residency (MIR) program. However, once the specialty training is over, it is necessary to regulate further training.

Maybe we should work on how to approach cardiovascular disease from an overall perspective. We should have teams working on prevention, others on diagnosis, and other teams on therapeutics. Interventional cardiology and surgery should be included in the latter group.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

D. Arzamendi is a proctor for Mitraclip and Triclip (Abbott), and Pascal (Edwards Lifescience).

REFERENCES

1. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;14:e35-e71.

2. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307-2318.

3. Obadia J-F, Messika-Zeitoun D, Leurent G, et al. Percutaneous Repair or Medical Treatment for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2297-2306.

4. Badhwar V, Sorajja P, Duncan A, et al. Mitral regurgitation severity predicts one-year therapeutic benefit of Tendyne transcatheter mitral valve implantation. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:e1065-e1071.

5. Lurz P, Stephan von Bardeleben R, Weber M, et al. Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair for Treatment of Tricuspid Regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:229-239.

6. Lim DS, Kar S, Spargias K, et al. Transcatheter Valve Repair for Patients With Mitral Regurgitation:30-Day Results of the CLASP Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1369-1378.

7. Nickenig G, Weber M, Schüler R, et al. Tricuspid valve repair with the Cardioband system:two-year outcomes of the multicentre, prospective TRI-REPAIR study. EuroIntervention. 2021;16:e1264-e1271.

QUESTION: Briefly, what is the evidence behind the percutaneous left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) regarding oral anticoagulation (OA)? Is there any evidence on direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DAOAs)?

ANSWER: The LAAC has been compared to OA regarding the prevention of thromboembolic events in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) in 3 randomized clinical trials: the PROTECT AF, the PREVAIL, and the PRAGUE-17. The first 2 ones randomized 1114 patients with NVAF and CHADS2 ≥ 1 on a 2:1 ratio to receive the Watchman device (Boston Scientific, United States) or warfarin. In an intention-to-treat meta-analysis of aggregate individual data from the 2 studies with 5-year follow-ups no differences were seen between both strategies in the primary composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, and cardiovascular or unexplained death (hazard ratio [HR], 0.82; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.58-1.17; P = .27).1 In the secondary endpoint analysis a higher—though not statistically significant—rate of ischemic stroke or systemic embolism was reported in the device group (HR, 1.71; 95%CI, 0.94-3.11; P = .08). On the contrary, the LAAC was associated with a lower rate of hemorrhagic (HR, 0.20; 95%CI. 0.07-0.56; P = .002) or incapacitating stroke (HR, 0.45; 95%CI, 0.21-0.94; P = .034), major hemorrhage unrelated to the procedure (HR = 0.48; 95%CI 0.32-0.71; P < 0.001), cardiovascular or unexplained death (HR, 0.59; 95%CI, 0.37-0.94; P = .027), and all-cause mortality (HR, 0.73; 95%CI, 0.54-0.98; P = .035).

The results of the PRAGUE17 clinical trial have been recently published. This study randomized 402 patients on a 1:1 ratio with NVAF and an indication for OA to LAAC with the Amplatzer Amulet (Abbott Vascular, United States) (61.3%) or the Watchman device (38.7%) or to a DAOA, mainly apixaban (95.5%).2 This trial only included patients considered of high risk with some of the following criteria: history of bleeding that required intervention or hospitalization, past medical history of embolism despite treatment with OA or CHA2DS2-VASc scores ≥ 3 with HAS-BLED ≥ 2. During the mean follow-up of 20.8 months ± 10.8 months no differences were seen in the composite primary endpoint (stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic embolism, cardiovascular death, major or clinically relevant bleeding or procedural or device-related complications) reaching criteria of non-inferiority (HR, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.53-1.31; P = .44; P for non-inferiority = .004). No differences between both groups were seen either in any of the events included in the composite primary endpoint separately.

Currently, there are 4 ongoing different randomized clinical trials that will be assessing the benefits of the LAAC with the Watchman FLX device (CHAMPION-AF [NCT04394546]), the Amplatzer Amulet device (CATALYST [NCT04226547]) or with either one of the 2 (OCCLUSION-AF [NCT03642509], CLOSURE-AF [NCT03463317]) vs DAOA therapy in patients with NVAF.

Q.: Which are the current indications for the LAAC? Should the clinical guidelines most recently published be changed somehow?

A.: The European guidelines on the management of AF published in 2020 suggest that the LAAC could be considered in patients with NVAF and a contraindication to OA (IIb level of recommendation, C level of evidence).3 Regarding this indication, I think a few considerations should be made. In the first place, the evidence available on the LAAC is limited basically because of the non-inferiority design of the clinical trials available with a limited number of patients. Also, due to the great heterogeneity of the antithrombotic therapy indicated post-LAAC, that could be conditioning the applicability of the results obtained. Secondly, the guidelines were written before the results of the PRAGUE-17 trial came out, that are consistent with the efficacy and safety profile of the procedure, also vs DAOAs (although in a limited 2-year follow-up) that is currently the treatment of choice to prevent thromboembolic events in patients with AF with, at least, moderate risk. Thirdly, since it is a «prophylactic» therapy, procedural success should be high, and the rate of related complications should be low. In this sense, in the largest registry published to this date of over 38 000 patients, the rate of procedural success was 98.3% and the rate of major complications, 2.16%.4 Finally, the lack of compliance to medical therapy and under or overdosing are common problems in our routine clinical practice, which has a significant impact on the efficacy of OA, which is probably reported in the randomized clinical trials as well.

Q.: Which is the common practice at your center?

A.: The patient’s profile eligible for this procedure is that of an elderly patient with an indication for OA due to NVAF with a previous episode of intracranial or gastrointestinal bleeding. Other less common cases are patients with chronic anemia or high bleeding risk with an indication for OA or dual or triple antithrombotic therapy. Finally, more and more patients with stroke despite being on OA are being reported. We perform a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) prior to the procedure in all the cases. We often perform implantation with mild sedation and TEE guidance with microprobe. Antithrombotic therapy upon discharge is based on every particular patient and followed-up at the specific structural heart disease consultation within the first year including TEE sometime within the first 3 months after hospital discharge.

Q.: How valuable are imaging modalities in the selection of patients and procedural guidance?

A.: The preprocedural study of left atrial appendage aims at determining the anatomical feasibility for implantation purposes, providing the right dimensions for a proper sizing of the device, and excluding the existence of thrombi. To this end, a 3D imaging modality should be used, usually a TEE or a computed tomography scan. The selection of one or the other will depend on its accessibility, experience of every center, and certain characteristics of the patient like the presence of kidney disease. Regarding the computed tomography scan, a 2-stage acquisition protocol with sensitivity and specificity rates close to 100% for the detection of thrombi should be conducted.

In most cases, the LAAC is performed with TEE guidance. However, this imaging modality has complications: on the one hand, the prolonged use of the probe can cause non-negligible oropharyngeal lesions. On the other hand, general anesthesia is required in many patients with the corresponding complications and increased procedural duration and costs. In this sense, as we have been gaining experience on device implantation, new options have come up to minimize these limitations like the TEE microprobe and the intracardiac echocardiography. The microprobe provides slightly lower quality of image compared to conventional TEE but is better tolerated by the patient and requires no general anesthesia. The drawback is that no 3D images can be acquired, which means that a previous study capable of providing 3D images is necessary. Regarding intracardiac echocardiography, the latest machines available provide better quality of images, some even the possibility of 3D reconstructions (still not on the market). They do not require the presence of an imaging specialist at the cath lab or use of a transesophageal probe either. On the other hand, both the cost of the device and its disposable nature reduce its utility in the routine clinical practice. Several ongoing prospective registries will be shedding light on the safety, feasibility, and possible technical advantages.

Q.: Are there any significant differences among the different devices available?

A.: Despite the technical advances made in the procedure, there are still pending challenges or, at least, room for improvement: a) great anatomical variability in the left shape, orientation, and size of left atrial appendage; b) risk of perforation with pericardial effusion; c) device embolization; d) persistent residual leak after implantation; and e) rate of device related thrombosis. For all these reasons, there are many devices to perform LAAC available today or in the pipeline that try to improve some of these aspects. Generally speaking, 2 important types of design can be distinguished here: tamponade-like devices like the Watchman, and anchor-disc shaped devices like the Amplatzer Amulet. In principle, the latter can be more versatile in complex anatomies while the first one has a growing body of evidence. Regarding procedural results, the observational data obtained do not suggest differences in the implantation success rate or in the rate of serious complications, device thrombosis or significant residual leak reported between the 2 most widely used devices to this date. However, the results from comparative studies AMULET IDE [NCT02879448] and SWISS-APERO [NCT03399851]5 will bring us more data on this regard.

There are many other devices available with scarce evidence and limited used, but with technical advances and very promising designs: extreme sizes, antithrombotic expanded polytetrafluoroethylene covering, self-adaptable configuration to the left atrial appendage ostium, small anchor with large disc configuration, highly flexible or articulated devices…Given the great anatomical variability of the left atrial appendage, maybe some devices will be complementary in the future. Therefore, if the volume of cases allows it, it can make sense to use more than just 1 type of device in every patient, the one more suitable to his anatomy.

Q.: Please tell us about any relevant ongoing clinical trials. In your professional opinion, what type of study should be conducted?

A.: There is no doubt that the most significant randomized clinical trials that are being conducted today are those comparing the LAAC to DAOAs. These trials will eventually determine the actual benefit of this procedure. Another very important aspect to elucidate is the optimal antithrombotic therapy to prevent device thrombosis. In this sense, the following randomized clinical trials should be highlighted: a) the SAFE-LAAC trial [NCT03445949] will assess the 6-month efficacy profile of dual antiplatelet therapy vs a 1-month course of dual antiplatelet therapy plus 5 months of single antiplatelet therapy; b) the ANDES trial [NCT03568890] will analyze the DAOA strategy vs an 8-week course of dual antiplatelet therapy; c) the FADE-DRT trial [NCT04502017] will be comparing the efficacy profile of 3 strategies consisting of a 6-week course of OA followed by a 6-month course of dual antiplatelet therapy, half-dose DAOA plus genotype-guided dual targeted therapy (acetylsalicylic acid + clopidogrel or half-dose DAOA depending on clopidogrel resistance or not); and d) the ASPIRIN-LAAO trial [NCT03821883] that will be analyzing the benefit of keeping single antiplatelet therapy starting 6 months after the procedure.

Another particularly interesting randomized clinical trial is the OPTION [NCT03795298] that will be randomizing 1600 patients treated with ablation due to AF to receive the Watchman FLX device or OA. Finally, from a theoretical point of view, evidence is still scarce in some potentially LAAC-eligible patients as it is in patients with recurring thromboembolic events despite OA or with NVAF and chronic kidney disease on dialysis. Both groups are characterized by a very high thrombotic risk. There is lack of consensus regarding the most adequate antithrombotic strategy that is empirically administered in most of the cases. Also, patients on dialysis have a high hemorrhagic risk and, unlike the general population, OA does not seem to benefit them. Some observational studies suggest that the LAAC can be safe and effective in these subgroups of patients. However, to this date, no randomized clinical trial has studied this therapy compared to others.

FUNDING

The author received no financial support for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. 5-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure:From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2964-2975.

2. Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P, et al. Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Direct Oral Anticoagulants in High-Risk Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3122-3135.

3. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2020:ehaa612.

4. Freeman JV, Varosy P, Price MJ, et al. The NCDR Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1503-1518.

5. Basu Ray I, Khanra D, Shah S, et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing WatchmanTM and Amplatzer Devices for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:89.

QUESTION: Briefly, what is the evidence behind the percutaneous left atrial appendage closure (LAAC) regarding oral anticoagulation (OA)? Is there any evidence on direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DAOAs)?

ANSWER: The main clinical evidence published on this regard comes from 3 randomized clinical trials (2 vs anti-vitamin K and 1 vs DAOAs), registries, and case series. The PROTECT AF clinical trial1 included 707 patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and CHADS2 scores ≥ 1 who were randomized on a 2:1 ratio to receive the Watchman device (Boston Scientific, United States) or warfarin. The composite endpoint (stroke, cardiovascular death, and systemic embolism) was less prevalent in patients with the Watchman device (relative risk [RR], 0.62; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.35-1.25); however, adverse events were more common in the device group (RR, 1.69; 95%CI, 1.01-3.19) mainly due to periprocedural complications. These increased adverse events triggered a second clinical trial, the PREVAIL,2 that included 407 patients with CHADS ≥ 2 randomized on a 2:1 ratio to receive the Watchman device or warfarin. The primary efficacy endpoint at the 18-month follow-up (stroke, systemic embolism or cardiovascular or inexplicable death) occurred less often than expected in the warfarin group and the non-inferiority target was not achieved. However, the secondary efficacy endpoint (stroke or systemic embolism 7 days after implantation) was achieved; also, adverse events were less common compared to those of the PROTECT AF trial.

Data from the PROTECT AF1 and PREVAIL2 clinical trials were combined in a meta-analys3 that concluded that the Watchman device was not inferior to anti-vitamin K therapy for the composite endpoint of stroke, cardiovascular death, and systemic embolism. We should mention that patients with the Watchman device had lower chances of bleeding including hemorrhagic strokes. Nonetheless, there was a statistically insignificant higher rate of ischemic stroke and systemic embolism in the Watchman group.

The controversial aspect of these 2 clinical trials is that they only included patients with an indication for OA. However, in the routine clinical practice, the LAAC is used in patients contraindicated to OA.

The third and last clinical trial is the PRAGUE-174 that compared the LAAC to DAOAs. It included 402 patients with AF (CHA2DS2-VASc: 4.7 ± 1.5) and a past medical history of major bleeding or cardioembolic event while on DAOAs or with o con CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 3 and HAS-BLED > 2. Apixaban was the most commonly used DAOA (95.5%). The median follow-up was 19.9 months. No statistically significant differences were found in the annual rates of the primary endpoint (stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic embolism, cardiovascular death, clinically relevant or major bleeding or procedural complications) that were 10.99% with the LAAC and 13.42% with DAOAs (sub-hazard ratio, 0.84; 95%CI, 0.53-1.31 for non-inferiority). A total of 9 patients (4.5%) experienced major complications due to device implantation.

Regarding real-world registries, the NCDR LAAO5 is a large registry designed to assess the utility, safety, and effectiveness of LAAC percutaneous devices in the clinical practice. It includes 38 158 procedures performed in the United States. The mean score in the CHADS-VASC scale was 4.6 ± 1.5, and in the HAS-BLED scale, 3.0 ± 1.1. In-hospital major adverse events occurred in 2.16% of the patients; the most common complications were pericardial effusion that required intervention (1.39%), and major bleeding (1.25%), while strokes (0.17%) and death (0.19%) were rare.

Q.: Which are the current indications for the LAAC? Should the clinical guidelines most recently published be changed somehow?

A.: The most common indications in the routine clinical practice are high bleeding risk and contraindications to DAOAs (eg, dialysis), but as I said, the LAAC has not been studied in clinical trials with the proper statistical power in these subgroups

The recent guidelines published by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)6 give the LAAC a class IIb recommendation and a B level of evidence for the prevention of strokes in patients with AF and contraindications to long-term anticoagulant therapy (eg, intracranial hemorrhage without reversible cause). The clinical guidelines published by the American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and the Heart Rhythm Society (AHA/ACC/HRS)7 also give it a class IIb recommendations as a therapeutic option for patients with an indication for oral anticoagulation, but with a high risk of bleeding, poor compliance or tolerance to anticoagulant therapy. In both guidelines, recommendations are limited. The consensus document published by the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)8 regarding the LAAC makes an extensive review including the largest possible number of indications:

-

1)Patients with contraindications to OA due to:

-

a) High risk of potentially life-threatening or incapacitating hemorrhage or due to untreatable causes like intracranial/intraspinal bleeding (eg, diffuse amyloid angiopathy or untreatable vascular malformation) or severe gastrointestinal (eg, diffuse angiodysplasia) pulmonary or urogenital bleeding that cannot be corrected.

-

b) Serious adverse events with anti-vitamin K therapy or contraindications to DAOAs.

-

-

2) Patients who don’t follow their anticoagulant therapy properly. This indication is controversial, and we should always inform the patient that his main treatment is anticoagulation while trying to solve the problem associated with poor compliance.

-

3)Some specific subgroups:

-

a) Ineffective OA: stroke in a patient properly anticoagulated.

-

b) After pulmonary vein ablation with left atrial appendage electrical isolation due to the high embolic risk involved after this procedure.

-

c) Combination of pulmonary vein ablation and LAAC within the same procedure.

-

d) «Primary» prevention: in patients with interatrial communication treated with percutaneous closure during the same procedure even before the patient develops AF.

-

Q.: Which is the common practice at your center?

A.: The most common indications are patients with AF on hemodialysis who, we already know, are poor candidates to anti-vitamin K therapy and have contraindications to DAOAs. Also, patients with very high risk of bleeding without treatable cause, especially digestive or due to other causes (eg, Rendu-Osler-Weber disease) and always after trying to solve it with a DAOA.

Q.: How valuable are imaging modalities in the selection of patients and procedural guidance?

A.: The use of imaging modalities is essential if we wish to perform successful procedures. Before the intervention, the anatomy of the left atrial appendage should be studied to see if it is eligible for closure. Also, the right material should be chosen and the presence of thrombi in the left atrium and left atrial appendage should be discarded. In general, this preprocedural assessment is performed with a transesophageal echocardiography, yet the computed tomography scan has been gaining traction.

During the procedure, x-ray images and transesophageal echocardiography are the common imaging modalities to use. When available, intracardiac echocardiography can also be used.

Between 6 and 24 weeks after the intervention, a transesophageal echocardiography or a computed tomography scan should be performed to discard the presence of thrombi in the device (that can appear in up to 2% to 4% of the cases) and significant peridevice leaks (> 5 mm).8

Q.: Are there any significant differences among the different devices available?

A.: The need for antithrombotic therapy post-LAAC shows that there is room for improvement because this procedure maintains the bleeding risk for a longer period of time, and it is still unclear what the optimal protocol should be. The PROTECT AF and the PREVAIL clinical trials kept patients on warfarin and acetylsalicylic acid for 45 days followed by a 6-month course of dual antiplatelet therapy and then acetylsalicylic acid for life.

The guidelines published by the ESC6 recommend acetylsalicylic acid permanently, clopidogrel between 1 and 6 months after the procedure and, for the Watchman device, in cases of low-risk of bleeding, a 45-day course of OA after implantation.

The consensus document published by the EHRA8 includes general recommendations that are very similar to those from the guidelines published by the ESC.6 It also claims that in patients with very high-risk of bleeding the use of single antiplatelet therapy could be an option (acetylsalicylic acid or clopidogrel) for short periods of time. However, this should always be an informed decision and the patient should think about it thoroughly.

Q.: Please tell us about any relevant ongoing clinical trials. In your professional opinion, what type of study should be conducted?

A.: The main ongoing trials are the ASAP-TOO that is assessing the LAAC in 888 patients with AF considered ineligible for OA; the OPTION trial, that is studying 1600 patients with AF to see if the LAAC with the Watchman FLX device is a reasonable option to OA (including DAOAs) after pulmonary vein ablation; and the CATALYST and CHAMPION-AF clinical trials, that will be conducting a long-term comparison between the Amulet (Abbott Vascular, United States) and the Watchman FLX device with DAOAs in patients with an indication for anticoagulant therapy due to AF.

Future clinical trials should prioritize the study of new devices comparing them to DAOAs since they are currently the therapy of choice to prevent strokes in patients with AF, especially those with relative or absolute contraindications to anticoagulation therapy. The use of these devices in patients with ischemic stroke despite the proper anticoagulation therapy should be analyzed too by associating the LAAC with an DAOA and then comparing it to an isolated DAOA. Finally, it is essential to clarify antithrombotic therapy after implantation in order to minimize it, above all, in patients with high risk of bleeding, while still keeping its efficacy.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

1. Holmes DR, Reddy VY, Turi ZG, et al. PROTECT AF Investigators. Percutaneous closure of the left atrial appendage versus warfarin therapy for prevention of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation:a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2009;374:534-542.

2. Holmes DR Jr, Kar S, Price MJ, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of the WATCHMAN Left Atrial Appendage Closure device in patients with atrial fibrillation versus long-term warfarin therapy:the PREVAIL trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1-12.

3. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al.;PREVAIL and PROTECT AF Investigators. 5-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure. From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2964-2975.

4. Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P, et al. Left atrial appendage closure versus direct oral anticoagulants in high-risk patients with atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3122-3135.

5. Freeman JV, Varosy P, Price MJ, et al. The NCDR Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1503-1518.

6. Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2020;42:373-498.

7. January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS Guideline for the Management of Patients With Atrial Fibrillation. Circulation. 2019;140:e125-e151.

8. Glikson M, Wolff R, Hindricks G, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group, EHRA/EAPCI expert consensus statement on catheter-based left atrial appendage occlusion –an update. Europace. 2020;22:184.

QUESTION: How often do you see nonrevascularizable patients with refractory angina today?

ANSWER: The prevalence of this complex entity has gone up thanks to the better prognosis of patients with ischemic heart disease due to changes of lifestyle, drugs, and coronary interventions. Among these, surgical revascularization and, in particular, percutaneous coronary interventions increase survival in the acute coronary syndrome setting. For its diagnosis, reversible myocardial ischemia that cannot be controlled with a combination of medical therapy, angioplasty, and myocardial revascularization surgery needs to be documented first. Although it is often due to severe stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries, it can be seen in non-atherosclerotic coronary artery diseases (spasm, microvascular disease, etc.) and myocardial diseases within the heart-brain axis including myocardial metabolism, and coronary microcirculation. Also, in the perception of pain until neuromodulatory pathways that can also be therapeutic targets in this clinical condition. Therefore, obstructive coronary disease is only one of the possible phenotypes in patients (women in particular) with angina or myocardial ischemia. There is no clear evidence associated with a higher mortality rate; however, the quality of life of rehospitalized patients is worse and health costs are higher.1,2 Former studies1,3 describe a prevalence of refractory angina (RA) of 5% to 10% in patients with chronic coronary syndromes; these studies often focus on nonrevascularizable patients with angina on non-optimized antianginal drug therapy excluding patients without stenosis of epicardial coronary arteries. These studies do not report either on possible cases of RA due to coronary microvascular dysfunction that actually seem to be most of the patients with RA.

Q.: Please explain to us briefly the diagnostic approach used for screening etiologies different from ischemia due to epicardial coronary artery disease such as microvascular ischemia, vasospasm or even noncardiac causes.

A.: Beyond the traditional idea of ischemia-angina where imbalance between myocardial oxygen supply and demand is the main pathophysiological mechanism, we should admit that, in many cases, ischemia is not followed by angina and that many ischemic patients have a constellation of symptoms that may worsen their quality of life.

To improve quality of like is the primary endpoint in patients with angina in the chronic ischemic heart disease setting since its presence or myocardial ischemia do not seem to increase mortality. In this sense, rather than making us question the prognostic value of systematic myocardial revascularization in patients with angina in the chronic coronary syndrome setting, the recent results of the ISCHEMIA clinical trial4 should make us think of the need to conduct routine tests to detect ischemia. In this study, over 20% of the selected patients with angina/ischemia could not be randomized eventually for the lack of significant coronary stenoses. In this sense, it has been reported that nearly 40% of the patients with angina without coronary stenosis showed vasomotor response disturbances in coronary micro and macrocirculation. On the other hand, we should transcend the idea of hypoperfusion as the cause of angina and myocardial ischemia; the metabolic alterations of cardiomyocytes related to hypoxia can be due to peaks in the ischemia threshold as the adaptation of metabolism to hypoperfusion or decrease in metabolic situations of use of substrates of lower energy efficiency.1

The diagnosis of microvascular angina is often achieved after discarding significant epicardial coronary stenosis; since segmental contractility alterations are rare on these patients’ exercise echocardiography, we need specific techniques to assess coronary circulation/perfusion and confirm the diagnosis.

I’d like to add that angina, including RA, in the absence of significant coronary stenosis cannot be a diagnosis of exclusion. New protocols are needed to confirm not only the clinical signs and ischemia, but also the pathophysiological mechanisms involved. Only then the diagnostic and therapeutic strategy will be complete for each particular case.

Q.: Which are the best pharmacological strategies to treat refractory angina and how should drug escalation be done?

A.: I think that changing our management of nonrevascularizable patients with RA to improve their clinical situations is a priority. These patients often remain in some sort of diagnostic and therapeutic limbo. Disease exists beyond the possibilities of coronary dilatation. Therefore, only by knowing the pathophysiological substrate of angina in each particular case, we’ll be able to establish protocols including new therapeutic, pharmacological or other modalities.5

The standard of care for the management of patients with RA is to discard and treat secondary causes by optimizing medical therapy and rehabilitation. These patients should be treated with antianginal drug therapy, beta-blockers, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, and sustained-release nitrates. In cases of persistent angina, ivabradine can be used in patients who are in sinus rhythm with heart rates ≥ 70 beats/minute. Also, the possible combination of ranolazine, trimetazidine, and nicorandil is another antianginal therapeutic option. Patients with RA without obstructive coronary lesions benefit from a better control of their angina when therapy is based on every particular patient and the results of intracoronary functional tests. Patients with microvascular angina, reduced coronary flow reserve, increased resistances, and a negative acetylcholine testing respond positively to treatment with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins. They are also responsive to rehabilitation programs to control their risk factors, physical exercise, and weight loss. Patients with EKG changes and angina as a response to the acetylcholine testing but without epicardial coronary spasm should be treated as if they had vasospastic angina: dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and sustained-release nitrates are the drugs of choice associated with changes in the patient’s lifestyle and control of their risk factors. Data available today show the efficacy of ranolazine plus traditional antianginal drugs in patients with microvascular angina; due to its mechanism of action, it should be considered a supplementary therapeutic option in this group of patients

Q.: Which non-invasive, non-pharmacological alternatives exist for these patients?

A.: As I already mentioned, patients with RA should join structured cardiac rehabilitation programs to change their lifestyle. Exercise adapted to each particular case has proven to improve ischemia and stimulate collateral circulation, coronary vascular function, and control the main cardiovascular risk factors. To control the symptoms, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been suggested. Extracorporeal shock waves can promote myocardial revascularization, and external counterpulsation generates diastolic retrograde aortic flow that increases the coronary diastolic and mean pressures. Also, retrograde flow improves myocardial perfusion after inducing flow-mediated coronary vasodilation and stimulates angiogenesis. There is not a single solid piece of evidence on the utility of these techniques in patients with RA. Actually, they should be used based on each particular case strictly as compassionate use and only when the remaining therapeutic options have failed.1

Q.: What evidence do we have today on the Reducer device?

A.: Several invasive techniques have been developed to improve angina including neural stimulation, stellate ganglion block, myocardial laser revascularization, angiogenic stimulation with plasmid DNA, and implantation of CD34+ and CD133+ cells. The results of a recent meta-analysis on the intramyocardial injection of CD34+ have confirmed that it improves angina, the patients’ functional capacity, and prognosis. However, for the time being these techniques are in research stage only.1

The description that an increased coronary sinus pressure induces myocardial flow redistribution in the ischemic regions of patients with RA is the basis of the Reducer device design (Neovasc Inc., Canada). It is a metal balloon-expandable percutaneous device that causes the focal the stenosis of coronary sinus rising its pressure and elevating it in the venules and capillaries too. This promotes the redistribution of flow bringing the endocardial/epicardial perfusion gradient back to normal.1 Several studies confirm the safety profile of this technique and its benefits regarding symptom improvement; the early study results of 15 patients confirmed its long-term safety profile with 12-year patency in 10 of these patients and symptom improvement. However, device migration and coronary sinus perforation and bleeding have been reported; these are complications that should be taken into consideration when giving this device a clinical use. From my own point of view, the only randomized clinical trial published to this date, the COSIRA (Coronary sinus reducer for treatment of refractory angina)6 offers modest efficacy results. A total of 104 patients with RA were randomized to receive the Reducer device or undergo a sham procedure. The patients who received the device improved their angina symptoms and quality of life. However, no significant changes were seen in the stability and frequency of angina or in the duration of exercise.

Several real-world registries confirm the efficacy and safety profile seen in the clinical trial with maximum clinical benefits reported after 4 months and maintained at the 2-year follow-up.7 Improvements in inducible ischemia, functional capacity in the cardiopulmonary exercise testing, myocardial perfusion, and cardiac function have been reported. A special comment should be made on symptom efficacy and myocardial perfusion with the Reducer device in 8 patients with microvascular angina.1

Considering the time elapsed since the arrival of the Reducer device and the scarce quality of scientific evidence with just one randomized clinical trial available and a very qualitative primary endpoint (the assessment of the patient’s self-reported angina), in my opinion, at least, 2 clinical trials should be conducted: the first one in patients with RA due to nonrevascularizable coronary lesions. The second one in patients with microvascular angina. The first study primary endpoint should include symptom improvement according to some objective test of overload and myocardial perfusion assessed through cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. The second study primary endpoint should also include these components plus the functional assessment of coronary microcirculation. In the meantime, I think it should only be used as compassionate use in quality high-volume PCI-capable centers for the management of patients with RA on an optimized therapeutic strategy and clinical follow-up including objective tests to assess ischemia and myocardial perfusion.

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts related to this work.

REFERENCES

1. Gallone G, Baldetti L, Tzanis G, et al. Refractory angina. From pathophysiology to new therapeutic nonpharmacological technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1-19.

2. Lanza GA, Crea F, Kaski JC. Clinical outcomes in patients with primary stables microvascular angina:is the jury still out?Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;5:283-291.

3. Sara JD, Widmer RJ, Matsuzawa Y, Lennon RJ, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Prevalence of Coronary Microvascular Dysfunction Among Patients With Chest Pain and Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1445-1453.

4. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

5. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407-477.

6. Verheye S, Jolicœur EM, Behan MW, et al. Efficacy of a device to narrow the coronary sinus in refractory angina. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:519-527.

7. Giannini F, Baldetti L, Ponticelli F, et al. Coronary Sinus Reducer Implantation for the Treatment of Chronic Refractory Angina:A Single-Center Experience. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:784-792.

QUESTION: How often do you see nonrevascularizable patients with refractory angina today?

ANSWER: Refractory angina is defined as chronic angina that cannot be controlled even with the use of optimal medical therapy and where all revascularization options have failed.1,2 It is a common entity whose prevalence is on the rise due to the ageing of population and the improved prognosis of ischemic heart disease. It is estimated that between 5% and 10% of the patients with chronic ischemic heart disease can develop refractory angina. Its annual incidence rate is between 50 000 and 100 000 cases in the United States and between 30 000 and 50 000 cases in Europe.1,2 On the other hand, we know that around 10% of all coronary angiographies performed indicate that it is not possible to give efficient options of revascularization. According to the activity registry in interventional cardiology in Spain from 2019,3 this figure would be up to 15 000 patients each year, and it is reasonable to think that a significant percentage can suffer refractory angina.

These patients often remain asymptomatic which negatively impacts their quality of life and. Actually, to this day, we still do not have effective therapeutic options to offer. Multidisciplinary approach is crucial here (cardiology, family medicine, cardiac rehabilitation, psychology, pain management units, etc.). Also, we should consider the use of non-pharmacological therapies like spinal cord or subcutaneous stimulation, external counterpulsation or use the coronary sinus reducer device as well as keep looking into other alternatives like new drugs, cardiac shock wave therapy or use of progenitor cells.1,2

Q.: Please explain to us briefly the diagnostic approach used for screening etiologies different from ischemia due to epicardial coronary artery disease such as microvascular ischemia, vasospasm or even noncardiac causes.

A.: The diagnosis of refractory angina is mainly clinical, but it is important to show that there is a correlation between symptoms and ischemia. That is why it is essential to confirm the presence of myocardial ischemia, if possible, through imaging modalities like stress echocardiography, pharmacological stress echocardiography, single-photon emission tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. If no ischemia is seen on these imaging modalities, other possible causes for the symptoms should be considered like esophageal spasm or osteomuscular etiology. In the presence of ischemia, we need to know the coronary anatomy preferably through a coronary angiography before discussing any revascularization options. Information should be analyzed by the heart team including experienced interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons to determine the possibilities of percutaneous or surgical revascularization.

There are 2 groups of patients without revascularization options: the largest one, with advanced coronary disease (diffuse disease, small-caliber distal beds, chronic total coronary occlusions non-eligible for percutaneous coronary intervention, coronary artery bypass graft deterioration…); and that of patients with angina and myocardial ischemia without obstructive coronary lesions. In these patients it would be good to perform a functional study with microvascular dysfunction and coronary spasm testing (coronary reserve, index of microvascular resistance, absolute coronary flow, acetylcholine test) to facilitate targeted therapies with better symptom control.

Q.: What evidence do we have today on the Reducer device?

A.: It is a new option for patients with refractory angina with a different mechanism of action over the cardiac venous system. This mechanism developed over 60 years ago by Claude S. Beck4 is based on creating coronary sinus (CS) stenosis to generate a pressure gradient that is transmitted retrogradely to venules and capillaries, which translates into an improved subendocardial perfusion, probably due to collateral recruitment through the venous plexus and Thebesian veins.

The first experience with humans was reported back in 2007. In 2015 the COSIRA multicenter, randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled clinical trial5 was published. It included a total of 104 patients with refractory angina and functional class III or IV according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) with ischemia seen on the dobutamine stress echocardiography and without any revascularization options after assessment by the medical team assessment. The primary endpoint was to reduce, at least, 2 CSS functional class degrees of severity of angina at the 6-month follow-up. The Reducer device was superior to the sham procedure (35% vs 15%; P = .024), improved, at least, 1 CSS functional class degree of angina in 71% of the patients vs 42%, and improved parameters like duration of exercise or quality of life.

Also, there is evidence of the results of the REDUCE registry6—similar to those reported by the COSIRA trial—in the routine clinical practice on the improvement of, at least, 1 CSS functional degree of angina in 81% of the patients, better parameters of quality of life, greater distances covered in the six-minute walk test, and lower the need for antianginal drugs. The REDUCER-1 registry results of 195 patients presented at Euro-PCR 2019 showed that clinical benefit remained at the 2-year follow-up.7

Overall, in all the studies published it was effective in up to 75% of the patients.8 The reasons why some patients remain unresponsive to therapy are still not known, but they could be associated with lack of device endothelization or with an alternative venous drain through other territories.

An important conclusion we can draw from the accumulated experience is that the implantation of the Reducer device is viable and safe5-8 with serious complications (like CS dissection or perforation or device embolization) in less than 2% of the cases. The 10-plus-year follow-up of the early patients has confirmed its patency and lack of structural alterations in the long-term. No CS thrombosis has ever been reported after implantation.

Magnetic resonance imaging study supports the hypothesis of an increased subendocardial perfusion as the mechanism of action by showing that in ischemic areas the correlation between the myocardial perfusion reserve index and the endocardial reserve index—that remains low at baseline—increases after implantation. Also, myocardial perfusion improves when reducing the myocardial ischemic burden, improving the longitudinal and circumferential strain and systolic function without microstructural alterations or effect on the diastolic function.9

With the accumulated evidence, the last clinical practice guidelines on the management of chronic coronary occlusions of 2019 established by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) included, for the very first time, the implantation of the Reducer device in patients with refractory angina with the same level of recommendation (IIb, level of evidence B) than other previous non-pharmacological options like external counterpulsation or spinal cord stimulation.10

Q.: How is the selection process of the most eligible candidates for this technique?

A.: In my opinion, most patients with symptomatic refractory angina are potential candidates despite the optimal medical therapy without percutaneous or surgical revascularization options after assessment by the heart team and with myocardial ischemia in the left main coronary artery territory as seen on the imaging modalities.6 Due to vein drain anatomy of the right coronary artery territory through the middle and small cardiac veins that drain into the CS very close to its ostium, this drainage would not be affected by the implant. For this reason, the Reducer device would not be the right option for patients with ischemia in the right coronary artery territory only. Thanks to its mechanism of action, it may be an interesting option for patients with ischemia due to microvascular disease without lesions in the epicardial coronary arteries. Although information is still limited in this context information, the early data are positive.11

One contraindication would be the presence of left ventricular pacing electrodes through the CS for resynchronization purposes, which is why its indication should be carefully studied in patients with ventricular dysfunction who may be candidates to such therapy.

Patients with refractory angina can also be candidates to other non-pharmacological therapies like external counterpulsation or neurostimulation. Although they have been available for decades, these techniques have been underused for different reasons like the perception of the lack of efficacy or placebo effect or lack of solid scientific evidence. Randomized clinical trials are needed to compare these different techniques and establish the best way to approach the management of these patients.

Q.: Can you please give us a brief technical description of this procedure?

A.: The implantation of the Reducer device is easy on the technical level12,13 and successful in over 95% of the cases. The device is implanted under local anesthesia via right jugular vein as the access of choice and preferably under vascular ultrasound guidance. A 6-Fr introducer sheath is used followed by the advancement of a multipurpose catheter until the right atrium while keeping the mean pressure < 15 mmHg (with higher pressures the implantation is ill-advised since the pressure of the CS is already high at the baseline level). Afterwards, the CS undergoes selective catheterization by carefully advancing the multipurpose catheter and avoiding small-caliber branches like the left marginal ones or the vein of Marshall. There are times that a highly developed or fenestrated Thebesian valve can make selective catheterization difficult. A venography of CS is performed through the multipurpose catheter to see its size, the origin of lateral branches, and the presence of valves (like Vieussens valve that can complicate the implant).

If the procedure is continued, heparin is administered, and the guidewire is placed distal to the CS. Then, the introducer sheath is changed for a 9-Fr sheath to advance the guide catheter and deliver the device in the location previously indicated by the venography (2-4 cm from the origin of CS avoiding the jailing of lateral branches). The device consists of a stainless-steel balloon-expandable stent whose balloon has the shape of a sand clock that leaves a central waist of 3 mm. It is implanted through the inflation of a second balloon for 30 to 60 seconds at 4 to 6 atm, adjusting its size to the actual diameters of CS of 9.5 mm to 13 mm. During inflation oversizing is attempted (10% to 20%) to reduce the risk of embolization and facilitate neointimal coverage. Once implanted, the balloon is carefully removed until the guide catheter making sure that the Reducer device remains stable. Lastly, a new venography is performed to check the position of the device and lack of complications. The patient can be discharged early on after the procedure and dual antiplatelet therapy is advised for, at least, a month. The effect is evident with device endothelization, which creates a coronary sinus (CS) stenosis, which is why it is necessary to wait between 4 and 6 weeks to determine its efficacy.

In conclusion, the CS Reducer device is a new technique for the management of refractory angina. It improves myocardial perfusion acting from the cardiac venous system. Clinical results confirm its efficacy and safety profile, the technique is easy to use, and its indication has already been established in the clinical practice guidelines. Clinical evidence still needs to grow with more patients, longer follow-up periods, comparisons to other therapies, and further research on the mechanisms of nonrespondent patients. Nonetheless, the Reducer device is a new tool in the interventional cardiology armamentarium that can be an option for patients with refractory angina without revascularization options.

FUNDING

No funding.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Gallone G, Baldetti L, Tzanis G, et al. Refractory Angina:From Pathophysiology to New Therapeutic Nonpharmacological Technologies. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1-19.

2. Sainsbury PA, Fisher M, de Silva R. Alternative interventions for refractory angina. Heart. 2017;103:1911-1922.

3. Ojeda S, Romaguera R, Cruz-González I, et al. Registro Español de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista. XXIX Informe Oficial de la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (1990-2019). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2020;73:927-936.

4. Beck CS, Leighninger DS. Scientific basis for the surgical treatment of coronary artery disease. J Am Med Assoc. 1955;159:1264-1271.

5. Verheye S, Jolicoeur EM, Behan MW, et al. Efficacy of a device to narrow the coronary sinus in refractory angina. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:519-527.

6. Giannini F, Baldetti L, Konigstein M. Safety and efficacy of the reducer:A multi-center clinical registry REDUCE study. Int J Cardiol. 2018;269:40-44.

7. EuroPCR 2019. A proven evidence-based therapy when angina persists. Reducer I Registry. Verheye S. Available online: https://www.pcronline.com/. Accessed 8 Sep 2020.

8. Konigstein MN, Giannini F, Banai S. The Reducer device in patients with angina pectoris:mechanisms, indications, and perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:925-933.

9. Palmisano A, Giannini F, Rancoita P, et al. Feature tracking and mapping analysis of myocardial response to improved perfusion reserve in patients with refractory angina treated by coronary sinus Reducer implantation: a CMR study. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10554-020-01964-9.

10. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407-477.

11. Giannini F, Baldetti L, Ielasi A, et al. First Experience With the Coronary Sinus Reducer System for the Management of Refractory Angina in Patients Without Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1901-1903.

12. Giannini F, Aurelio A, Jabbour RJ, et al. The coronary sinus reducer:clinical evidence and technical aspects. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017;15:47-58.

13. Giannini F, Tzanis G, Ponticelli F, et al. Technical aspects in coronary sinus Reducer implantation. EuroIntervention. 2020;15:1269-1277.

- Debate: Intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography in percutaneous revascularization. The OCT expert perspective

- Debate: Intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography in percutaneous revascularization. The IVUS expert perspective

- Debate: Mechanical circulatory support in relation to coronary intervention. Cardiologist’s perspective from the cardiac intensive care unit

- Debate: Mechanical circulatory support in relation to coronary intervention. The interventional cardiologist perspective

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

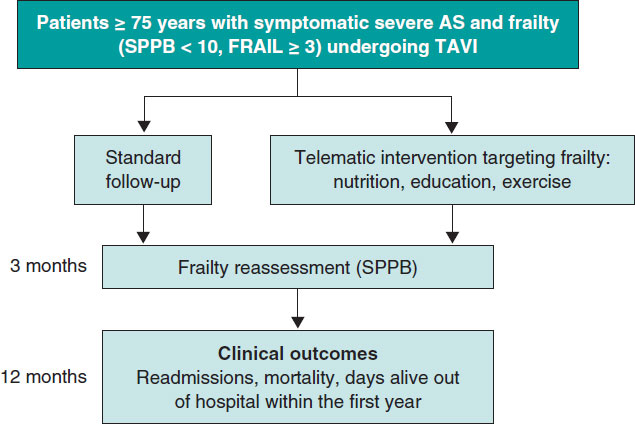

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España