Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: In your opinion, what conclusions can be drawn from the 2 ORBITA trials?1,2

ANSWER: The 2 ORBITA studies aim to settle the debate on the utility of coronary revascularization in patients with stable chronic angina and coronary artery lesions causing ischemia in that territory. The first ORBITA trial1—a double-blind, multicenter clinical trial published in 2018—randomized 230 patients with stable angina and at least 1 severe coronary stenosis (> 70%) to undergo percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or receive placebo to assess the symptom relief of angina. After being included in the study, both groups received a strategy of medical therapy optimization 6 weeks prior to randomization. There were no significant differences at the 6-month follow-up in the primary endpoint of exercise tolerance between the 2 groups. The authors concluded that the efficacy of invasive procedures should be determined with placebo control only (without pharmacological optimization). This is precisely what the recently published ORBITA-2 trial2 aimed to address. This trial randomized 301 patients in 14 centers in the United Kingdom to receive PCI or placebo. Two weeks before randomization, all antianginal drugs were discontinued. All patients were required to have significant coronary artery disease and evidence of ischemia in at least 1 vascular territory. Both groups received dual antiplatelet therapy (including the placebo group). The primary endpoint (assessment of angina, need for medication, and events after the 12-week follow-up) favored the PCI group vs the placebo group, with improvements in the follow-up ergometry and quality of life tests. The authors conclude that, in patients with stable angina, coronary artery disease, evidence of ischemia in that vascular territory, and not on antianginal drugs, PCI was more effective in reducing angina symptoms than placebo.

In my opinion, both studies confirm 2 issues: on the one hand, that the first-line therapy in patients with stable angina is optimal medical therapy; on the other hand, that PCI improves the symptoms, exercise capacity, and quality of life of patients who continue to experience angina or treatment-related adverse effects.

Q.: What would be the key features aspects of these 2 studies?

A.: Methodologically, the 2 studies have been conducted appropriately, but with very few patients. In the ORBITA trial1, recruitment was not easy (230 patients in 4 years, in 5 major centers in the United Kingdom), meaning there is a patient selection bias (generally less severe patients). Coronary artery disease was estimated visually (lesions > 70%), without the use of intracoronary imaging, and not all lesions were proximal, which likely have a higher ischemic burden. Finally, 85% of patients who did not undergo PCI, were eventually treated with percutaneous coronary revascularization during follow-up.

The ORBITA-2 trial2 addressed some of these limitations by using intravascular imaging and coronary physiology, which identify really significant lesions and avoid treating lesions that are functionally nonsevere, reducing events during follow-up.3-5 However, once again, and in 14 centers, enrolling 300 patients took more than 4 years. Ethical aspects of the study have been criticized, as comparison vs placebo and not vs optimal medical therapy left the placebo group without any treatment for angina and exposed them to unnecessary bleeding risks due to dual antiplatelet therapy. Nevertheless, conducting the study in this manner seems timely, since both the true utility of PCI and even the foundations of coronary physiology were questioned following the results of the ORBITA trial,1 suggesting that an increase in fractional flow reserve in an ischemic territory had no impact at all, which has been elucidated in the ORBITA-2 trial.2

Finally, perioperative myocardial infarction remains the weak point of coronary interventions in all clinical trials. The definition of “perioperative infarction” includes everything from Q-wave infarction related to loss of epicardial branch to mild troponin elevation (the threshold is 5 times higher than the upper limit, according to the current definition6) due to complications occurring during potentially treatable intervention with good final outcomes (branch dissection, no-reflow, compromised temporary flow, etc). Undoubtedly, this limits revascularization options (whether percutaneous or surgical) in all clinical trials. Therefore, it would be advisable to differentiate between the type of infarction, particularly those with the most prognostic implications.

Q.: What do you think these 2 studies contribute compared with the much larger ISCHEMIA trial?

A.: The ISCHEMIA trial,7 published in 2020, was much larger, with more than 5000 patients with stable coronary artery disease and moderate-to-severe ischemia, randomized to an initial invasive strategy with coronary angiography and revascularization, when necessary, along with medical therapy, or to an initially conservative strategy, with medical therapy alone and angiography if insufficient. The aim of the study was prognostic—not symptomatic—assessment, with a composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or hospitalization for unstable angina, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest. After a median follow-up of 3.2 years, the initial invasive strategy did not reduce the risk of cardiovascular ischemic events or all-cause mortality compared with the conservative strategy.

Setting aside the limitations and potential criticisms of the ISCHEMIA trial,7 such as recruitment difficulties, very rigorous inclusion criteria, the absence of severe ischemia in a high percentage of cases, and that 25% of patients in the conservative treatment group eventually underwent revascularization, it is obvious that the aim of the study is very different from that of the ORBITA and ORBITA-2 trials.

In general, the prognosis of chronic coronary syndromes is good, but it is difficult to demonstrate prognostic differences in this subgroup of patients after a mean follow-up of just over 3 years. Furthermore, the ISCHEMIA trial included a group of patients who were heterogeneous in certain aspects features excluded those with more severe coronary artery disease (such as left main coronary artery disease) or ventricular dysfunction, in whom the prognostic impact of revascularization is known to be greater.

Another issue is symptom relief and quality of life. Indeed, the authors of the ISCHEMIA trial7 reported clinical implications and improvements in terms of quality of life. Although 35% of patients remained asymptomatic, the invasive strategy was associated with an improvement in angina-related quality of life, especially in patients with complete revascularization.8 This difference was greater for symptomatic patients.

The ORBITA trials focus on symptom relief in patients with chronic coronary syndromes, but with significantly fewer patients and shorter follow-up periods to demonstrate improvement in exercise capacity and quality of life, which were indeed observed in the secondary endpoints of the ISCHEMIA trial.

Q.: Based on all this evidence, what are the benefits, if any, of the invasive strategy over the conservative approach?

A.: The advantage of the invasive strategy over the conservative approach as first-line therapy has not been demonstrated in patients with chronic coronary syndromes. The cornerstone of therapy for patients with chronic angina is optimal medical therapy, as stated by clinical practice guidelines. In fact, the publication of the ORBITA trials has not changed these guidelines at all.

However, considering the results of these studies, we can be in no doubt that PCI is the best therapeutic option in patients who cannot control their symptoms with drugs, with drug-related adverse effects, or even those who simply do not want to continue taking drugs to control their symptoms. Revascularizing these patients is possible with good results and symptom relief.

We will have to wait for longer-term follow-up of the ISCHEMIA trial7 to evaluate whether coronary revascularization in patients with stable chronic angina has any prognostic impact. For the time being, until further evidence becomes available for confirmation, we know that the patients included in the study treated with complete revascularization experienced fewer events (cardiovascular death or myocardial infarction) during follow-up than those undergoing incomplete revascularization or an initial conservative strategy.9 Additionally, myocardial infarctions during follow-up (separating them from the perioperative infarctions with the above-mentioned implications) were also fewer in the group who initially underwent the invasive strategy.10

Finally, we should consider that all 3 studies included patients with generally low-risk chronic coronary syndromes, most with clearly demonstrated moderate ischemia, and single-vessel involvement, so their results are not generalizable to patients with more complex coronary artery disease, such as multivessel disease, left main coronary artery disease, or associated ventricular dysfunction.11 Therefore, the correct identification and characterization of coronary artery disease are important, which almost always requires noninvasive coronary angiography, or invasive angiography if the former is inconclusive. Another question arises: once coronary artery disease has been accurately assessed, should the patient undergo revascularization or should a conservative approach to their lesions be pursued for symptom relief? Or, depending on the extent or severity of the coronary artery disease and the myocardial territory at risk, is a more aggressive approach necessary, with either percutaneous or surgical revascularization?

Q.: What indications do you take into consideration in your routine clinical practice to decide which invasive approach to use in a patient with stable angina?

A.: The results obtained in the ORBITA trials maintain medical therapy as the first option for patients with chronic angina and relegate the invasive approach to those with symptoms that cannot be resolved despite optimal medical therapy. This would, therefore, be the indication in stable chronic angina. However, such results cannot be extrapolated to patients with multivessel disease and severe ischemia, so it would be a mistake to take them as a reference to stop performing coronary angiograms, which would imply avoiding the revascularization of patients at higher risk than indicated by their symptoms. Therefore, as always in medicine, each patient should be individually evaluated to determine who requires an earlier invasive approach based on their symptoms and multiple other factors. We’ll still have to wait for longer-term results, even for these lower-risk patients due to their lower ischemic burden, to see how the story ends.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA):a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:31-40.

2. Rajkumar CA, Foley MJ, Ahmed-Jushuf F, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Stable Angina. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2319-2330.

3. Holm NR, Andreasen LN, Neghabat O, et al. OCTOBER Trial Group. OCT or Angiography Guidance for PCI in Complex Bifurcation Lesions. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1477-1487.

4. Lee JM, Choi KH, Song YB, et al. RENOVATE-COMPLEX-PCI Investigators. Intravascular Imaging-Guided or Angiography-Guided Complex PCI. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1668-1679.

5. Tonino PAL, De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, et al. FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213-224.

6. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Executive Group on behalf of the Joint European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)/World Heart Federation (WHF) Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2231-2264.

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

8. Mavromatis K, Jones PG, Ali ZA, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Complete Revascularization and Angina-Related Health Status in the ISCHEMIA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:295-313.

9. Stone GW, Ali ZA, O'Brien SM, et al.;ISCHEMIA Research Group. Impact of Complete Revascularization in the ISCHEMIA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:1175-1188.

10. Redfors B, Stone GW, Alexander JH, et al. Outcomes According to Coronary Revascularization Modality in the ISCHEMIA Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:549-558.

11. Al-Mallah MH, Ahmed AI, Nabi F, et al. Outcomes of patients with moderate-to-severe ischemia excluded from the ISCHEMIA trial. J Nucl Cardiol. 2022;29:1100-1105.

QUESTION: In your opinion, what conclusions can be drawn from the 2 ORBITA trials?1,2

ANSWER: The ORBITA trials focus on a specific aspect of the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome: the benefit in terms of symptom relief of angina.1,2 The first ORBITA trial1 is a double-blind, randomized, multicenter clinical trial, with 230 patients with severe single-vessel disease and ischemic symptoms that analyzed whether percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) was associated with an improvement in angina-free exercise time compared with a placebo procedure.1 There were no statistically significant differences in the primary endpoint (differences in exercise increment on the stress test) at the 6-week follow-up between the 2 groups. The second ORBITA trial2, a double-blind, multicenter clinical trial, randomized 301 patients with exertional angina to undergo PCI or a placebo procedure.2 The methodology differs from that of ORBITA trial: all patients discontinued antianginal medication 2 weeks before randomization and were only included if they experienced angina throughout this period (assessed by a complex scoring system through a mobile application).3 Only patients with at least 1 severe coronary stenosis confirmed through physiological assessment were included; additionally, the 2 groups underwent the intervention (which was simulated in the group treated with the placebo procedure), and all patients received dual antiplatelet therapy. In total, 80% of patients had single-vessel disease, mostly involving the left anterior descending coronary artery, and complete revascularization was achieved in approximately 100% (using intracoronary imaging in 70% of PCIs). At the 12-week follow-up, patients treated with PCI experienced statistically significant greater angina relief, as well as improved exercise tolerance and quality of life than those in the placebo group.

Q.: What would be the key features of these 2 studies?

A.: Despite introducing the novel concept of simulating a PCI in the placebo group (thus avoiding the effect of attributing clinical improvement to the procedure per se), the main limitations of the first ORBITA trial were its small sample size and limited follow-up time. Moreover, the use of exercise tolerance with the stress test as the main study endpoint has been criticized due to its heterogeneity. Of note, 29% of patients had a negative functional flow reserve study (> 0.80), suggesting that there was no symptom improvement after PCI. Indeed, a prespecified substudy determined that, unlike angina (assessed by scores or exercise time), functional flow reserve did predict an improvement in ischemia (assessed by dobutamine stress echocardiography).4 All in all, the possible impact of this study on clinical practice seems limited.

Unlike the first trial, the main criticism of ORBITA-2—which evaluated patients with lesions in more than 1 vessel—is the discontinuation of antianginal treatment (ie, it compared PCI with patients without pharmacological treatment, unlike ORBITA, in which patients remained on optimal medical therapy), against the recommendation of clinical practice guidelines.5 Although the effect of PCI is expected to be immediate and sustained, the 12-week follow-up remains limited. Indeed, the main criticism that can be made of the study is its methodology: using a placebo procedure—not optimal medical therapy—for comparison may limit its clinical applicability. Nonetheless, the double-blind design of the study helps provide further evidence on PCI treatment in patients with coronary ischemia (both anatomical and functional) by improving the pathophysiology of the imbalance between oxygen supply and demand.

Q.: What do you think these 2 studies contribute compared with the much larger ISCHEMIA trial?

A.: In the context of chronic coronary syndrome, revascularization aims to provide 2 benefits: prognostic or symptomatic. In summary, the prognostic benefit of revascularization is well established in patients with severe left main or multivessel disease and left ventricular ejection fraction < 35%.5,6 However, there is more uncertainty surrounding the prognostic benefit in patients with extensive ischemic territory (a topic of discussion in the ISCHEMIA trial) and in evaluating the symptomatic benefit of the intervention regarding angina. The ISCHEMIA trial, with a larger sample size than the ORBITA trials, randomized a total of 5179 patients with stable coronary artery disease and moderate-to-severe ischemia on stress testing to an initial invasive or conservative strategy.7 After a median follow-up of 3.2 years, there were no significant differences between the 2 strategies in the primary endpoint (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina hospitalization, heart failure, or resuscitated cardiac arrest). Although the multiple limitations of the study may affect the interpretation of its results (a high crossover rate between the 2 groups, up to 14% of the patients included in the study had mild or no ischemia, and the inclusion of perioperative infarctions which could bias the primary endpoint—more numerous in the invasive treatment group), patients randomized to the invasive treatment group showed greater symptomatic relief than those in the conservative treatment group. This benefit was greater in patients with more frequent episodes of angina at baseline and was less significant in asymptomatic patients, even with inducible ischemia.8

In my opinion, the main difference between the ORBITA and ISCHEMIA trials, beyond the sample size and limitations of the methodology of the former, is the blinding of patients undergoing invasive treatment in the ORBITA trials. Of note, symptoms are subjective and evaluating any intervention on cardiovascular events can have both a physiological component and a placebo effect. Therefore, we should welcome invasive studies to simulate the procedure in the control group because they allow testing the direct effect of the intervention on subjective endpoints, such as angina relief.

Q.: Based on all this evidence, what are the benefits, if any, of the invasive approach over the conservative approach?

A.: Current clinical practice guidelines (while awaiting the 2024 update from the European Society of Cardiology on the management of chronic coronary syndrome) state that the PCI should be reserved for patients who, despite being on optimal medical therapy, exhibit refractory symptoms,5,6 and the aforementioned evidence does not indicate the need to change this indication. The ORBITA trials have demonstrated that the relationship between epicardial coronary stenosis, ischemia, and symptoms is more complex than we had initially thought, while the ISCHEMIA trial has revealed the questionable impact of relieving ischemia on the incidence of events. Indeed, the severity of ischemia is a reflection of the burden of atherosclerotic disease, which is why only revascularizing the identified blockages will not have any clinical impact, as the intervention cannot change the underlying process.9 Moreover, an important point that should be made is that up to one-third of patients still experience angina symptoms despite successful revascularization.10 In this scenario, even the cost-effectiveness of the invasive approach vs optimal medical therapy remains to be elucidated.11 Therefore, beyond revascularization per se, an invasive hemodynamic study can provide valuable information to confirm the mechanism of ischemia (microcirculation abnormalities, vasomotor dysfunction, etc) and help optimize pharmacological treatment.

Q.: What indications do you take into consideration in your routine clinical practice to decide which invasive approach you should use in patients with stable angina?

A.: Setting aside scenarios where revascularization has previously shown prognostic improvement, as mentioned earlier, it seems reasonable to believe that the gold standard for stable angina should be pharmacological therapy. However, the fact that stable angina is a chronic disease, and the patient requires long-term antianginal drugs can complicate proper symptom control. Additionally, factors such as poor medication tolerability, suboptimal adherence, or the patient’s own preference must be considered. In all these situations, the invasive approach may be the preferred option.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Not used.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Al-Lamee R, Thompson D, Dehbi H-M, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in stable angina (ORBITA):a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:31-40.

2. Rajkumar CA, Foley MJ, Ahmed-Jushuf F, et al. A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Stable Angina. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:2319-2330.

3. Nowbar AN, Rajkumar C, Foley M, et al. A double-blind randomised placebo-controlled trial of percutaneous coronary intervention for the relief of stable angina without antianginal medications:design and rationale of the ORBITA-2 trial. EuroIntervention. 2022;17:1490-1497.

4. Al-Lamee R, Howard JP, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve and Instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio as Predictors of the Placebo-Controlled Response to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Stable Single-Vessel Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2018;138:1780-1792.

5. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:407-477.

6. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e18-e114.

7. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

8. Spertus JA, Jones PG, Maron DJ, et al. Health-Status Outcomes with Invasive or Conservative Care in Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1408-1419.

9. Teoh Z, Al-Lamee RK. COURAGE, ORBITA, and ISCHEMIA. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Stable Coronary Artery Disease. Intervent Cardiol Clin. 2020;9:469-482.

10. Arnold SV, Jang J-S, Tang F, Graham G, Cohen DJ, Spertus JA. Prediction of residual angina after percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Oucomes. 2015;1:23-30.

11. McCreanor V, Nowbar A, Rajkumar C, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of percutaneous coronary intervention for single-vessel coronary artery disease:an economic evaluation of the ORBITA trial. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e044054.

QUESTION: Although we will discuss the aspects of 2 plaque modification techniques, please explain when you resort to intravascular imaging modalities in cases of calcified lesions and how that helps you.

ANSWER: Intracoronary imaging modalities (optical coherence tomography [OCT] and intravascular ultrasound [IVUS]) allow us to optimize percutaneous coronary interventions, and their use in complex lesions improves the patient’s prognosis.1 They facilitate the following aspects:2

- – Calcification detection and assessment: they have higher sensitivity and specificity than angiography for detecting calcium.3 Also, they allow the evaluation of calcification characteristics, and various scores4,5 have been developed that integrate variables associated with stent underexpansion.

- – Selection of plaque modification technique: intracoronary imaging findings have an impact on the strategy used, which is why the use of advanced imaging modalities is advised in the presence of risk criteria for stent underexpansion.2

- – Optimization of stent deployment: this is especially relevant in calcified lesions, which are the lesions most frequently associated with stent underexpansion, the parameter most often associated with stent failure.2 Other parameters that should also be assessed are proper stent apposition, lesion coverage, the absence of dissection, and significant hematoma around the edges.6

Q.: In your opinion, what are the advantages and disadvantages of ablation, whether rotational or orbital?

A.: Ablation therapies, such as rotational atherectomy (RA), or orbital atherectomy (OA), and Excimer laser coronary angioplasty (ELCA), offer several advantages over intracoronary lithotripsy (ICL):

- – Greater crossing ability: calcified lesions that result in very severe stenosis can be uncrossable with a balloon. In these lesions, the use of ablation techniques improves the rate of procedural success,7,8 and probably, costs and safety.

- – Ability to reduce plaque volume: an aspect that can be essential to optimize results.

- – Treatment of long lesions and multivessel disease: ICL balloons are short in length, and display a maximum of 120 pulses per balloon. Also, balloons should be sized in a 1:1 ratio with respect to the vessel diameter, which complicates their use in multiple lesions. With RA, and especially with OA and ELCA, we can safely and effectively treat segments of different calibers without increasing costs.

- The potential disadvantages of ablation therapies are:

- – A longer learning curve: despite having specific technical aspects, ICL does not significantly differ from the plain old balloon angioplasty. Consequently, since it became available, the use of ICL has grown exponentially.9 Ablation techniques require more operator (and nursing) training, which can limit their use.

- – Need for specific angioplasty guidewires: ELCA can be used with 0.014-inch angioplasty guidewires, but both RA and OA require specific guidewires, whose characteristics have been improved to allow their use throughout the entire procedure, as with conventional guidewires. However, they can lead to more difficulties in directly crossing lesions and make the procedure more cumbersome due to their greater length and lower support.

- – Side branch protection: although it can be performed using specific techniques, placing a side branch protection guidewire at a bifurcation during RA or OA is ill-advised. However, this is possible with ICL and ELCA.

- – Distal embolization: debris following the use of ablation techniques can be associated with slow-no reflow.

Q.: In which cases do you use ablation as a first-line approach? Are there any distinctions between rotational and orbital atherectomies?

A.: We usually use these techniques as the first-line approach in lesions so severely stenosed that they complicate balloon crossing or simply make it impossible (uncrossable lesions). The information provided by intracoronary imaging also plays a role in the decision to use ablation techniques as the first option. For some operators, the mere fact of being unable to cross the lesion with an IVUS or OCT probe is, per se, a criterion for using these ablation techniques. If intracoronary images are available, the presence of severity criteria, or the desire to reduce plaque volume encourages the use of advanced plaque modification therapies. Superficial concentric calcification with a very reduced luminal area would favor their use.

In terms of the differences among ablation techniques, in my opinion, the crossing ability of RA and ELCA is superior to that of OA, which therefore makes RA the preferred option to treat critical or uncrossable lesions. On the other hand, OA provides additional advantages over RA.2,10 In the first place, we can treat vessels from 2.5 mm to 4 mm due to its mechanism of action (rotation associated with elliptical orbits) with a single 1.25 mm crown (compatible with 6-Fr) without increasing the size of the guide catheter. Also, the elliptical motion of this crown not only allows for superficial calcium shaving (like RA), but also exerts pulsatile forces against the wall that can modify deeper calcium deposits.10,11 This orbital movement reduces wire bias compared with AR. Wire bias limits ablation, which is contact-dependent, to the vessel sector where the guide is located. In eccentric or nodular plaques, the guidewire may be displaced toward the opposite side of the vessel, thus minimizing the effect of RA on the plaque. Another interesting feature of OA is that the crown has a diamond coating across its entire surface (not just on the distal end, like RA crowns), allowing atherectomy to make forward and backward motions. The pullback mode modifies the ablation vector, potentially reducing wire bias even further. Furthermore, the debris produced by OA is theoretically smaller than those produced by RA. This, along with the fact that the crown does not impede coronary flow during atherectomy, reduces the risk of slow-no reflow and endothelial thermal injury.10

The main difference among ELCA, RA, and OA is that the former is the only ablation technique that is compatible with conventional coronary guidewires. Also, ELCA is compatible with 6-Fr guide catheters and allows for side branch protection. Also, it has beneficial effects in reducing thrombus and has proven to be safe and effective in peristent calcified lesions (restenosis or underexpansion).

Q.: Which calcified lesions benefit more from ablation compared with intracoronary lithotripsy?

A.: The calcified lesions that benefit the most from initial ablation rather than ICL are the most severely stenotic lesions, which are rarely crossable with a lithotripsy balloon as a first-line approach, and those with a large volume of plaque that we intend to reduce. Ablation techniques facilitate crossing these stenoses and are sufficient in many cases (when calcification is superficial, without significant thickness, and when calcified nodules are not involved) to allow adequate balloon or stent expansion, and complete the angioplasty. In addition, diffuse lesions in multiple segments, or vessels of different calibers can benefit more from ablation because they can be treated with a single RA, AO, or ELCA catheter.

Finally, although ICL can be safely performed in left main lesions, some patients (especially those with ventricular dysfunction or right coronary artery disease) can tolerate prolonged ICL balloon inflations poorly, and benefit from ablation techniques as a first option.

Q.: How do you integrate both ablation techniques into your protocol to treat calcified lesions?

A.: There are several algorithms for plaque modification techniques based on expert opinion. Evidence from comparative trials among the various techniques is scarce. Although randomized clinical trials are under way,12 the lesion characteristics, clinical context, available resources, and operator capabilities should always be taken into consideration.

Intracoronary imaging modalities are essential to select the strategy. In general, it is useful to apply the rule of 5N:2 advanced plaque modification techniques are advised to treat lesions where calcium occupies > 50% of the calcium arc (180°), extends longitudinally > 5 mm, is > 0.5 mm thick, or has calcified nodules. Additionally, the depth of calcium is important since some techniques, such as RA, can only modify superficial calcium.

Lesions that cause stenosis so severe that they cannot be crossed by IVUS or OCT probes will likely require RA, OA, or ELCA. RA may be the preferred choice for very stenotic lesions with superficial circumferential calcification, especially if they are uncrossable with a balloon and involve a nontortuous coronary segment. OA may be preferred to treat ostial, nodular lesions, or angulated segments. OA can also be useful in long lesions with significantly different proximal and distal vessel calibers. ELCA would be the preferred choice in lesions that cannot be crossed even with a microcatheter that allows exchange with RA or OA-specific guidewires. Also, ELCA could be the first option to treat peristent calcified lesions and those that combine calcium and thrombus.

ICL has the advantage of being a simpler technique and being able to modify deep calcium. ICL allows side branch protection without causing distal embolization of material. ICL can be the first choice if the lesion is crossable with a balloon, calcification is deep or thick, or it affects a true bifurcation. Additionally, ICL is an optimal technique for use in combination with ablation techniques when these do not allow adequate balloon expansion, or in complex lesions such as calcium nodules. Volume reduction and superficial calcium shaving with ablation techniques allows balloon ICL crossing. This completes plaque modification by fracturing deeper calcium deposits. This technique, initially described as rotatripsy13 (RA and ICL), is increasingly being used. Combinations of ELCA and ICL,14 or OA and ICL15 are less common, but have also been reported.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used in the preparation of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Jurado-Román is a proctor for Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Systems, Inc., World Medica, and Philips-Biomenco.

REFERENCES

1. Lee JM, Choi KH, Song YB, et al. Intravascular Imaging–Guided or Angiography-Guided Complex PCI. N Engl J Med.2023;388:1668-1679.

2. Jurado-Román A, Gómez-Menchero A, Gonzalo N, et al. Plaque modification techniques to treat calcified coronary lesions. Position paper from the ACI-SEC. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:46-61.

3. Wang X, Matsumura M, Mintz GS, et al. In Vivo Calcium Detection by Comparing Optical Coherence Tomography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:869-879.

4. Fujino A, Mintz GS, Matsumura M, et al. A new optical coherence tomography-based calcium scoring system to predict stent underexpansion. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:e2182-e2189.

5. Zhang M, Matsumura M, Usui E, et al. Intravascular Ultrasound-Derived Calcium Score to Predict Stent Expansion in Severely Calcified Lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010296.

6. Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1:guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:656-677.

7. Abdel-Wahab M, Richardt G, Joachim Büttner H, et al. High-speed rotational atherectomy before paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in complex calcified coronary lesions:the randomized ROTAXUS (Rotational Atherectomy Prior to Taxus Stent Treatment for Complex Native Coronary Artery Disease) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:10-19.

8. Abdel-Wahab M, Toelg R, Byrne RA, et al. High-Speed Rotational Atherectomy Versus Modified Balloons Prior to Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation in Severely Calcified Coronary Lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e007415.

9. Jurado-Román A, Freixa X, Cid B, et al. Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry. 32nd official report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2022). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2023;76(12):1021-1031.

10. Yamamoto MH, Maehara A, Karimi Galougahi K, et al. Mechanisms of Orbital Versus Rotational Atherectomy Plaque Modification in Severely Calcified Lesions Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:2584-2586.

11. Yamamoto MH, Maehara A, Kim SS, et al. Effect of orbital atherectomy in calcified coronary artery lesions as assessed by optical coherence tomography. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:1211-1218.

12. Jurado-Román A, Gómez-Menchero A, Amat-Santos IJ, et al. Design of the ROLLERCOASTR trial:rotational atherectomy, lithotripsy or laser for the management of calcified coronary stenosis. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:279-286.

13. Jurado-Román A, Gonzálvez A, Galeote G, et al. RotaTripsy:Combination of Rotational Atherectomy and Intravascular Lithotripsy for the Treatment of Severely Calcified Lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e127-e129.

14. Jurado-Román A, García A, Moreno R. ELCA-Tripsy:Combination of Laser and Lithotripsy for Severely Calcified Lesions. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E754-E755.

15. Yarusi BB, Jagadeesan VS, Hussain S, et al. Combined Coronary Orbital Atherectomy and Intravascular Lithotripsy for the Treatment of Severely Calcified Coronary Stenoses:The First Case Series. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E210-E217.

QUESTION: Although we will discuss the aspects of 2 plaque modification techniques, please explain when you resort to intravascular imaging modalities in cases of calcified lesions and how that helps you.

ANSWER: Undoubtedly, intracoronary imaging modalities are an essential tool for interventional cardiologists in dealing with the assessment and treatment of calcified lesions. As we all know, revascularization of these lesions is associated with a higher rate of short- and long-term cardiovascular events, related to a greater risk of stent underexpansion and intraoperative complications.1 In calcified lesions, simple angiographic assessment is insufficient because of its lower sensitivity in the detection of coronary artery calcification, and limitations in the identification of calcium distribution patterns.

In my opinion, since optimizing results is so important, the use of intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography is mandatory in cases of moderate or severe calcification and helps us in several key aspects of the procedure. First, both intravascular ultrasound and optical coherence tomography have high sensitivity and specificity for calcium detection and its morphological characterization: pattern (nodular, parietal), angle, extent, and depth. With this information, we can select the best plaque modification technique for each case and evaluate its effect on the treated lesion. In recent years, several risk scores based on intracoronary imaging modalities have been developed, including decision algorithms for plaque modification systems based on calcium length, depth, and angle.2

Finally, imaging modalities allow us to be precise in selecting the size and length of the stent, as well as to assess its apposition and expansion, and rule out complications and residual disease. This aspect is crucial in the management of calcified lesions, where plaque modification devices can cause deep dissections and fractures, and we encounter more difficulties when trying to achieve adequate stent expansion.

Q.: In your opinion, what are the advantages and disadvantages of intracoronary lithotripsy?

A.: One of the main advantages for the implementation of intracoronary lithotripsy in the daily routine of cath labs is that it is technically simple and reproducible and does not require a long learning curve. The currently available intracoronary lithotripsy (ICL) system—Shockwave Medical, United States—consists of a specific semicompliant rapid-exchange balloon catheter with a 0.042-inch crossing profile, which is advanced inside the coronary arteries through a conventional 0.014-inch guidewire, and is compatible with a 6-Fr guide catheter. Once positioned in the lesion, the balloon is inflated to 4 atm with the sole intention of ensuring good contact between its surface and the vascular wall to facilitate energy transfer. Inside the balloon, there are 2 emitters that receive an electric discharge from the generator, vaporizing the liquid inside and generating sound waves that cause a local effect. The waves run through the soft tissues, causing selective calcium microfractures in the intimal and medial layers of the vascular wall. After pulse emission and the corresponding calcium modification, the balloon is inflated at 6 atm to maximize luminal gain.

On the other hand, compared with the limitations of noncompliant, very high-pressure, or cutting balloons, which in eccentric calcification can be directed toward noncalcified arterial segments with a risk of dissection at the fibrocalcific interface, ICL allows homogeneous calcium fracture. Another advantage is that ICL avoids the bias of having to follow the direction of the guidewire of rotational and orbital atherectomies, because it fractures calcium on superficial and deep layers circumferentially through acoustic pressure waves.3

Regarding complications, calcium fragmentation caused by the lithotripsy balloon remains in place, without distal embolization, thus reducing the incidence of slow-no reflow.4

In terms of disadvantages, the main limitation of ICL is its crossing profile: it often requires lesion predilatation or combination with atherectomy techniques. Notably, the DISRUPT CAD III trial5 reported ventricular captures during ICL pulses in 41.1% of the patients. Although the drop in systolic pressure is more common in patients in whom ICL induces ventricular capture, it has not been associated with the occurrence of adverse events, or sustained ventricular arrhythmias.

Q.: In which cases do you use intracoronary lithotripsy as a first-line approach?

A.: The available evidence on ICL comes from the DISRUPT CAD trials.5-8 The most relevant of these trials, the DISRUPT CAD III,5 is a prospective registry of 431 patients that assessed the safety and efficacy profile of the ICL balloon to treat calcified lesions. The 30-day rate of adverse cardiovascular events (death, myocardial infarction, or target lesion revascularization) was 7.8%, and the effectiveness rate (procedural success with in-stent stenosis < 50%) was 92.4%. This trial included patients with severely calcified de novo lesions and excluded those with acute myocardial infarction and aorto-ostial or bifurcation lesions.

As I mentioned previously, with the data provided by imaging modalities on calcium distribution and depth, we could consider ICL as the first-line approach to treat concentric calcified lesions with circumferential calcium distribution, especially in cases of deep calcium deposits, where ICL has proven more effective than other plaque modification techniques. Furthermore, ICL is effective in large-caliber vessels since balloons can be up to 4 mm in diameter.

One of the most common scenarios in which ICL is used in routine clinical practice is in calcified lesions that cannot be dilated with conventional or high-pressure balloons. This indication accounts for up to 75% of the cases in real-world registries,9 with very good results, and a procedural success rate of 99%.

Q.: Which calcified lesions benefit most from intracoronary lithotripsy compared with rotational or orbital atherectomy?

A.: While we can’t draw direct comparisons on the safety and efficacy results between ICL and rotational or orbital atherectomy because of the different inclusion criteria, stent types, and study endpoints among trials such as ROTAXUS10 and DISRUPT-CAD, in clinical practice, we choose one technique over the other based on the characteristics of the lesion.

Although, as I will discuss later, both techniques are complementary, atherectomy is an excellent option to treat balloon-uncrossable calcified lesions. However, atherectomy targets superficial calcium shaving, less so the deep calcium deposits. Hence, ICL is a better choice for concentric calcified lesions with circumferential and deep calcium distribution.

Beyond the landmark studies, in recent years, numerous real-world experiences11 have been reported, demonstrating the usefulness of ICL in specific and complex scenarios, such as:

- – Calcified bifurcation lesions: information on the safety and efficacy profile of ICL in complex contexts is limited to case reports and short series of patients describing experiences in substrates such as bifurcation or aorto-ostial lesions with promising results. Unlike rotational or orbital atherectomy techniques, ICL is increasingly used because it allows us to work with 2 different guidewires easily and simplifies the procedure in this context.

- – In-stent stenosis: Although this is an off-label use of ICL, there is growing evidence of the usefulness of ICL in both acute stent underexpansion and restenosis, especially in nondilatable lesions due to calcified neoatherosclerosis.12 In the Spanish multicenter REPLICA registry13 of 426 patients treated with ICL in routine clinical practice, a previously implanted stent was stenosed in 23% of the cases.

- – Chronic occlusions: ICL can be useful to treat chronic occlusions with severe calcification, and its use has increased in recent years, as confirmed by a recently published subanalysis of the PROGRESS-CTO registry14 with data from 82 patients (out of a total of 3301 included in the study [2.5%]) who underwent ICL. Indications were severe vessel calcification, or balloon nondilatable lesions. Technical success was achieved in 94% of the patients and procedural success in 90%.

- – Acute coronary syndrome: available data on the use of ICL in calcified lesions in patients with acute coronary syndrome are scarce. These cases were excluded from the DISRUPT-CAD trials, and again, the experience reported in the medical literature is limited to short case series. However, as the REPLICA registry results show, where a high percentage of patients with calcified lesions treated with ICL presented with acute coronary syndrome (62.8%), this technique is commonly used in the routine clinical practice in this group of patients who require a quick and safe technique.

Q.: How do you integrate the 2 techniques into your protocol to treat calcified lesions?

A.: The combined use of the ICL balloon and other plaque modification techniques, such as rotational15 or orbital atherectomy,16 has shown promising results in short patient series, and seems to be a highly attractive strategy when the target lesion cannot be reached with the ICL balloon.

In my opinion, the combination of atherectomy and ICL techniques is a suitable option to treat diffuse, superficial, and deep calcium deposits. By combining the 2 techniques, we can leverage the advantages of each. On the one hand, atherectomy allows the advancement of the ICL balloon in long lesions with severe stenosis that prevent its passage. On the other, ICL is very useful in balloon nondilatable lesions after atherectomy. This combination of techniques can be particularly useful in one of the most complex scenarios: the management of calcium nodules.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used in the preparation of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Généreux P, Redfors B, Witzembichler B, et al. Two year outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention of calcified lesions with drug eluting stents. Int J Cardiol. 2017;231:61-67.

2. Fujino A, Mintz G, Matsumura M, et al. A new optical coherence tomography-based calcium scoring system to predict stent underexpansion. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:e2182-e2189.

3. Jurado-Román A, Gómez-Menchero A, Gonzalo N, et al. Documento de posicionamiento de la ACI-SEC sobre la modificación de la placa en el tratamiento de las lesiones calcificadas. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:43-61.

4. Rodriguez Costoya I, Tizón Marcos H, Vaquerizo Montilla B, et al. Coronary Lithoplasty:Initial Experience in Coronary Calcified Lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:788-790.

5. Hill J, Kereiakes DJ, Shlofmitz RA, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2635-2646.

6. Brinton TJ, Ali ZA, Hill JM, et al. Feasibility of Shockwave Coronary Intravascular Lithotripsy for the Treatment of Calcified Coronary Stenoses. Circulation. 2019;139:834-836.

7. Ali ZA, Nef H, Escaned J, et al. Safety and effectiveness of coronary intravascular lithotripsy for treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses:the Disrupt CAD II study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e008434.

8. Saito S, Yamazaki S, Takahashi A, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy for vessel preparation in severely calcified coronary arteries prior to stent placement —primary outcomes from de Japanese Disrupt CAD IV Study. Circ J. 2022;85:826-833.

9. Azir A, Bhatia G, Pitt M, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy in calcified-coronary lesions:A real-world observational, European multicenter study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:225-235.

10. Abdel-Wahab M, Richardt G, Joachim Buttner H, et al. High-speed rotational atherectomy before paclitaxel-eluting stent implantation in complex calcified coronary lesions:the randomized ROTAXUS (Rotational Atherectomy Prior to Taxus Stent Treatment for Complex Native Coronary Artery Disease) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;6:10-19.

11. Vilalta V, Rodriguez-Leor O, Redondo A, et al. Litotricia coronaria en pacientes de la vida real:primera experiencia en lesiones complejas y gravemente calcificadas. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:76-81.

12. Tovar N, Sardella G, Salvi N, et al. Coronary litotripsy for the treatment of underexpanded stents:CRUNCH registry. Eurointervention. 2022;18:574.8112.

13. Rodriguez-Leor O, Cid-Alvarez AB, Lopez-Benito M, et al. A Prospective, Multicenter, Real-World Registry of Coronary Lithotripsy in Calcified Coronary Arteries: The REPLICA-EPIC18 Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.. 2024:76(12):1021-1031.

14. Kostantinis S, Simsek B, Karaksonyi J, et al. Intravascular lithotripsy in chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention:Insights from the PROGRESS?CTO registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;100:512-519.

15. Gonzalvez-Garcia A, Jimenez-Valero S, Galeote G, et al. “RotaTripsy”:combination of rotational atherectomy and intravascular lithotripsy in heavily calcified coronary lesions:a case series. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;35:179-184.

16. Yarusi BB, Jagadeesan VS, Hussain S, et al. Combined coronary orbital atherectomy and intravascular lithotripsy for the treatment of severely calcified coronary stenoses:the first case series. J Invasive Cardiol. 2022;34:E210-E217.

QUESTION: Can the prevalence of asymptomatic aortic stenosis and its various degrees of severity be estimated in the general population?

ANSWER: Although estimates can be made, they undoubtedly underestimate the true prevalence of asymptomatic aortic stenosis (AS). What we know is that, according to the 2017 European Cardiovascular Disease Statistics, over 6 million new cases of cardiovascular disease are diagnosed each year in Europe, with over 50 million prevalent cases (a 30% increase since 2000). In Spain, this amounts to over 250 000 new cases of cardiovascular disease diagnosed each year, and over 4 million prevalent cases.

If we focus on valvular heart disease, according to the latest Euro Heart Survey, AS is still the most widely diagnosed (41%) and frequently treated (45% of all procedures performed) severe valvular heart disease in the hospital setting. Undoubtedly, AS represents the highest burden of valvular heart disease among patients overall, and is even more significant among older adults. In the Olmsted County registry,1 the prevalence of AS was 0.5% (4.6% in patients older than 75 years, a rate very similar to that of the AGES-Reykjavík trial,2 where the prevalence of severe AS in patients older than 70 years was 4.3%.)

If we look at asymptomatic patients, data on the true prevalence are available but they are drawn from indirect sources. Spain has played a major role in our ability to estimate the prevalence in these patients. In the registry of Ferreira et al.3 the prevalences of sclerosis was 45.5% and that of stenosis was 3%. More recently, a study conducted by our group4,5 in vaccination centers found undetected aortic sclerosis in 53.4% of the patients and undetected AS in and 4.2%.

Therefore, based on the population prevalence data obtained and the current and projected composition of the Spanish population for the next 40 years, it is estimated that 470 000 Spaniards currently have undiagnosed AS. If the expectations for population growth and distribution of Spain’s National Statistics Institute are met, and if the proportion of diagnosed or treated cases vs undetected cases doesn’t change, the number of people with undiagnosed AS would be close to 1 million by 2060. If we assume that 10% of all undetected cases of AS are severe, were talking about nearly 100 000 cases of undiagnosed severe AS and, therefore, not followed-up or potentially treated. Let’s not forget that, currently, nearly 4500 cases of severe AS are treated each year, which helps put the problem in perspective.

Q.: How should patients with severe AS who remain asymptomatic be approached from a diagnostic standpoint?

A.: First, it is essential to make sure that a patient with severe AS is truly asymptomatic. The key is to delve deep into the patient’s past medical history and have an expert review the EKG performed. If stenosis is genuinely severe and asymptomatic, there are data that will eventually lead us to start early treatment. We should remember to assess the presence of ventricular dysfunction, symptom onset during exercise, a fall in blood pressure on exertion, marked elevations of brain natriuretic peptide levels, very extensive coronary artery calcification, and rapid reduction in aortic area during disease progression; these are clear indications that we need to act quickly. This is much more important with today’s well-established, low-risk percutaneous techniques. We should remember that, with the rapid advancement of the technique since the introduction of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), practices that we never thought to question, such as waiting for symptom onset or starting treatment before progression to severe disease, may have become outdated.

I think that the best time to treat asymptomatic patients with severe AS is when they develop left ventricular decompensation. Data such as brain natriuretic peptide levels, the EKG strain pattern, T1 mapping, and delayed enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging help identify high mortality risk in these patients. Therefore, stratifying heart damage adds additional prognostic value to the traditional clinical risk factors for predicting survival in asymptomatic AS.

Ongoing trials6,7 may lead us to consider earlier interventions even in asymptomatic patients.

Q.: What relevant evidence could support the use of aortic valve replacement in a case of truly asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis?

A.: There is evidence from patients who underwent surgery that supports the idea of treating asymptomatic patients. The AVATAR trial8 demonstrated that, in asymptomatic patients with severe AS, early surgery reduced the composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure-related admissions compared with conservative treatment.

The EARLY TAVR trial (NCT03042104) will examine the safety and efficacy profile of TAVI with the SAPIEN 3 or SAPIEN 3 Ultra valves vs clinical follow-up in asymptomatic patients with severe AS. The aim of this trial is to compare outcomes between patients undergoing valve replacement early in the disease and those undergoing clinical surveillance.

However, given the natural progression of AS and the low morbidity and mortality of TAVI, the idea of treating AS at an earlier stage of the disease has been suggested. The recent VALVENOR trial9 demonstrated that, compared with the general population, patients with moderate symptomatic AS had more cardiovascular mortality than those with mild AS (although still lower than that of patients with severe AS). In this regard, the PROGRESS (NCT04889872), TAVR UNLOAD (NCT02661451), and landmark EXPAND TAVR II trials (NCT05149755) assess TAVI vs clinical surveillance in symptomatic patients with moderate AS. While cautious optimism is warranted, it’s important to acknowledge certain potential limitations. Also, we must be aware that preventing valve degeneration is an important area of current research and that replacing the native valve with a prosthetic valve is not a permanent solution to the problem. Additionally, as we treat progressively younger patients, it is important to understand the anatomical limitations imposed by the need for future valve-in-valve procedures and the durability of the valves.

Q.: How does your center currently manage these patients?

A.: It’s obvious that our center has radically changed the diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment of these patients since we set up the Valve Clinic (2 clinical cardiologists and 1 heart valve clinical nurse specialist) 7 years ago. Diagnoses are reached following a standardized protocol and always with the same echocardiography machine, which is configured to only perform valve EKGs. This guarantees acceptable variability and standardization. Once the clinical cardiologist has decided that a patient needs treatment, we stay in close contact with other professionals specialized in the management of this type of patient. This undoubtedly enhances the quality of care. Data are reported to the hospital annually and are then published, including all possible complications and outcomes. Surgeons also present data on their surgically-treated patients on a yearly basis. We’re lucky to have excellent clinical cardiologists, operators, and surgeons at Hospital Ramón y Cajal with broad experience in the management of patients with valvular heart disease and with published data that can be audited.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.L. Zamorano has not received any funding for drafting this article. He has received speaker fees from Bayer, Pfizer, Daichii, and Novartis.

REFERENCES

1. Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases:a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368:1005-1011.

2. Danielsen R, Aspelund T, Harris TB, Gudnason V. The prevalence of aortic stenosis in the elderly in Iceland and predictions for the coming decades:The AGES-Reykjavík study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176:916-922.

3. Ferreira-González I, Pinar-Sopena J, Ribera A, et al. Prevalence of calcific aortic valve disease in the elderly and associated risk factors:a population-based study in a Mediterranean area. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20:1022-1030.

4. Ramos J, Monteagudo JM, González-Alujas T, et al. Large-scale assessment of aortic stenosis:facing the next cardiac epidemic?Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:1142-1148.

5. Ramos Jiménez J, Hernández Jiménez S, Viéitez Flórez JM, Sequeiros MA, Alonso Salinas GL, Zamorano Gómez JL. Cribado poblacional de estenosis aórtica:prevalencia y perfil de riesgo. REC CardioClinics. 2021;56:77-84.

6. Lancellotti P, Magne J, Dulgheru R, et al. Prognostic impact of left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:145157.

7. Bohbot Y, de Meester de Ravenstein C, Chadha G, et al. Relationship between left ventricular ejection fraction and mortality in asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:38-48.

8. Banovic M, Putnik S, Penicka M, et al. Aortic Valve Replacement Versus Conservative Treatment in Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis:The AVATAR Trial. Circulation. 2022;145:648-658.

9. Coisne A, Montaigne D, Aghezzaf S, et al. Association of mortality with aortic stenosis severity in outpatients. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1424-1431.

- Debate. Asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis: when should we intervene? The interventional cardiologist’s perspective

- Debate. Percutaneous revascularization in dilated cardiomyopathy. Apropos of the REVIVED BCIS2 trial: the clinician’s view

- Debate. Percutaneous revascularization in dilated cardiomyopathy. Apropos of the REVIVED BCIS2 trial: the interventional cardiologist’s view

- Debate. Cerebral embolic protection systems in TAVI: there is not enough evidence available

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

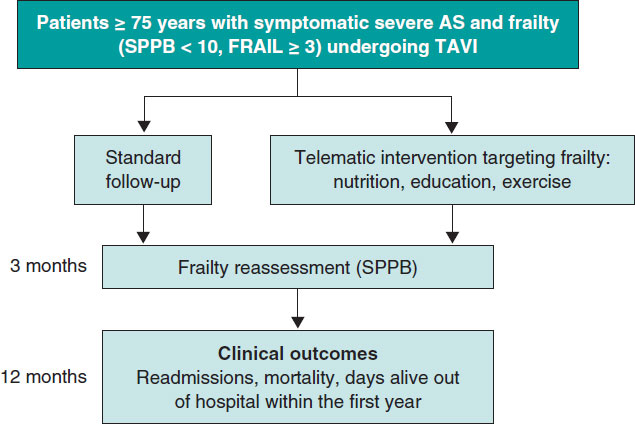

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España