Article

Debate

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:51-53

Debate: MitraClip. The heart failure expert perspective

A debate: MitraClip. Perspectiva del experto en insuficiencia cardiaca

aServicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia, INCLIVA, Universidad de Valencia, Valencia, Spain bCIBER de Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBERCV), Spain

Related content

Debate: MitraClip. The interventional cardiologist perspective

QUESTION: What aspects do you think might explain the significant differences reported between the results from the EBC MAIN (European bifurcation club left main coronary stent study),1 and the DKCRUSH-V (Double kissing crush vs provisional stenting for left main distal bifurcation lesions) clinical trials?2

ANSWER: Both studies differ in several aspects we could categorized into 4: those that are operator-related; study design-related; patient and lesion-related, and those associated with the results from the provisional stenting technique.

The double kissing (DK) is a complex technique where most of the evidence available in the medical literature (including the DKCRUSH-V2) comes from the same group of expert operators who have been using such technique for years now.3,4 However, the operators from the EBC MAIN1 belong to the European Bifurcation Club that has spent years promoting and refining the provisional stenting technique.

Regarding the study design, the group of patients randomized to 2 different stents is also different from one trial to the other: in the DKCRUSH-V only patients treated with the DK crush technique were while in the EBC MAIN most patients were treated with the culotte technique or the T stenting technique. Another different aspect between both trials is the use of systematic angiographic assessments at 1-year in the DKCRUSH-V trial (66% of the patients). It is precisely at this point when event curves separate, and significant differences arise. This strategy can introduce a bias in the study in favor of the double stenting technique that has better angiographic appearance.

The type of patients included is also different and can condition the results. The SYNTAX score was different between both studies being more complex the lesions of the of all DKCRUSH-V trial (31% vs 23%). Also, the length of the lesion in the collateral branch (usually the left circumflex artery) turned out to be longer in the DKCRUSH-V trial: 16 mm vs 7 mm. Therefore, these bifurcations with very long lesions in the side branch penalize the provisional stenting group.

Another aspect that calls our attention in the group of patients randomized to the provisional stenting technique in the DKCRUSH-V trial are the poor results obtained in this group. These results compare to the experience of many other groups and the results obtained on the EBC MAIN trial. Therefore, the rate of stent thrombosis (acute/subacute) in this group is high (2.5%) compared to the 0.8% reported from the EBC MAIN provisional stenting technique group. Also, the crossover rate to 2 stents is the highest of all in the provisional stenting group of the DKCRUSH-V trial compared to the EBC MAIN (47% vs 22%). These differences could be associated with the type of complexity of bifurcation (more complex in the DKCRUSH-V study).

Q.: In the light of the evidence available and based on your own experience, when do you recommend provisional stenting and when an early double stenting technique to treat distal left main coronary artery stenoses?

A.: According to the DKCRUSH-V trial2 and a meta-analysis recently published,3,4 if the provisional stenting technique does not give good results in complex bifurcation the recommendation of using «complex techniques (2 elective stents) for complex bifurcations» can be accepted. The problem consists of identifying this type of unfavorable bifurcations for a simple strategy. The DEFINITION trial (Definitions and impact of complex bifurcation lesions on clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention using drug-eluting stents)5,6 proposes a score based on 2 major criteria and 6 minor ones to distinguish simple from complex bifurcations. On the contrary, such meta-analysis3 identifies patients eligible who would benefit from the DK-Crush technique much easier: patients with long lesions > 10 mm in the collateral branch.

I’m more inclined towards easy rules and I’d make a slight modification of the Medina classification7 by adding, at the end, a letter based on the length of the collateral branch: S (short) < 10 mm, and L (long) > 10 mm. Therefore, we’d be recommending the provisional stenting strategy in the presence of these bifurcations:

- • 1, 1, 1, S

- • 1, 0, 1, S

- • 0, 1, 1, S

- • 1, 1, 0

- • 0, 1, 0

- • 1, 0, 0

However, in the following types of bifurcation we’d rather use the double stenting technique:

- • 1, 1, 1, L

- • 1, 0, 1, L

- • 0, 1, 1, L

Special situations like bifurcations with wiring of the collateral branch are difficult or restenosis of a simple technique can also be considered indications for the use of the elective double stenting technique in the bifurcation.

Q.: In how many angioplasties performed on the distal left main coronary artery is the double stenting technique often used?

A.: As a matter of fact, I think that we’d be under the numbers reported in the EBC MAIN trial (around 10%). For example, in our participation in the OPTIMAL trial of 21 patients included to this date with left main coronary artery disease, none of them was treated with the double stenting technique.

Q.: What is your favorite double stenting technique in the distal left main coronary artery and why?

A.: According to the data published in the medical literature available, I’d have to say the DK crush technique since it’s the most favored of all in the comparative studies conducted.3 However, such studies have the limitations already mentioned here.4 In its latest consensus document, the European Bifurcation Club8 recommends the provisional stenting technique when planning to use 1 single stent. Also, when the use of 2 stents can be anticipated before the procedure. In my opinion, the T stenting technique is the best one when the left main coronary artery/left circumflex artery has a configuration of 90º more or less. In such a way that the implantation of the second stent can be performed precisely into the ostium of the collateral branch by covering it completely without causing significant invasion of the carina. In case of a narrower angle, the DK-culotte technique would be the preferred one since it is impossible to make a perfect adjustment of the second stent without invading the main vessel or leaving a space without «stenting» the collateral branch. This technique can be used starting with the main vessel (provisional stenting philosophy) or the collateral branch (inverted culotte). The most practical thing to do would be to start with the diseased branch and then move on with a combo of POT (proximal optimization technique) plus double kissing balloon. This technique has been described recently,9 and we don’t have comparative studies against the DK crush technique. However, when refined8 it achieves an excellent stent expansion and apposition across all the bifurcation segments, which should lead to clinical outcomes.

Q: In your opinion, do you think that the use of intravascular imaging modalities to guide these procedures on the left main coronary artery is important?

A.: The use of intravascular imaging—mainly the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS)—in the percutaneous treatment of left main coronary artery has been a constant recommendation over the last few years.10,11 However, this recommendation is only based on the opinion of experts and observational studies. Therefore, in the latest European guidelines12 the recommendation of using IVUS in the percutaneous management of the left main coronary artery is weak (only IIa B). To achieve recommendation I, a randomized clinical trial would be needed to confirm that there are fewer clinical events. That is the objective of the OPTIMAL trial we are involved with right now. Although a study of this magnitude could change the clinical guidelines, the recruitment of patients is sometimes difficult to see because of our conviction that IVUS is necessary to perform stenting properly, and operators don’t want to leave randomized patients away from the benefits the technique has to offer. By describing this problem we face on a daily basis at the cath lab I think I have already answered to this question.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Conference or workshop minor fees from Abbott, Boston, Phillips, and Worldmedica have been declared.

REFERENCES

1. Hildick-Smith D, Egred M, Banning A, et al. The European Bifurcation Club Left Main Coronary Stent study: a randomized comparison of stepwise provisional vs. systematic dual stenting strategies (EBC MAIN). Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3829-3839.

2. Chen SL, Zhang JJ, Han Y, et al. Double Kissing Crush Versus Provisional Stenting for Left Main Distal Bifurcation Lesions: DKCRUSH-V Randomized Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2605-2617.

3. Di Gioia G, Sonck J, Ferenc M, et al. Clinical outcomes following coronary bifurcation PCI techniques: a systematic review and network meta-analysis comprising 5,711 patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2020;13:14321444.

4. Pan M, Ojeda S. Complex Better Than Simple for Distal Left Main Bifurcation Lesions. Lots of Data But Few Crushing Operators. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1445-1447.

5. Chen SL, Sheiban I, Xu B, et al. Impact of the complexity of bifurcation lesions treated with drug-eluting stents: the DEFINITION study (Definitions and Impact of Complex Bifurcation Lesions on Clinical Outcomes After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Drug-Eluting Stents). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1266-1276.

6. Zhang JJ, Ye F, Xu K, et al. Multicentre, randomized comparison of two-stent and provisional stenting techniques in patients with complex coronary bifurcation lesions: the DEFINITION II trial. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2523-2536.

7. Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. Una clasificación simple de las lesiones coronarias en bifurcación. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59:183.

8. Lassen JF, Albiero R, Johnson TW, et al. Treatment of coronary bifurcation lesions, part II: implanting two stents. The 16th expert consensus document of the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2022;18:457-470.

9. Toth GG, Sasi V, Franco D, et al. Double-kissing culotte technique for coronary bifurcation stenting. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:e724-e733.

10. Burzotta F, Lassen JF, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in left main coronary artery disease: the 13th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:112-120.

11. Mintz GS, Lefèvre T, Lassen JF, et al. Intravascular ultrasound in the evaluation and treatment of left main coronary artery disease: a consensus statement from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e467-e474.

12. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

QUESTION: What types of catheter-based invasive approaches are available today to treat acute pulmonary thromboembolism? Please give us a brief description of the techniques used.

ANSWER: Catheter-directed therapy (CDT) to treat pulmonary thromboembolism falls into 3 different categories: mechanical thrombectomy, local thrombolysis, and a combination of both.

Mechanical thrombectomy (MT) consists of thrombus fragmentation, aspiration or removal. Fragmentation consists of using CDT nonspecific devices such as pig-tail catheters (forced rotation inside the thrombus) or dilatation balloons to break down and fenestrate the thrombotic occlusion to improve flow towards completely occluded regions. This technique is not very precise or reproducible so as new specific devices appear it will probably fall into oblivion. It is often used as an early facilitator of aspiration or penetration of the thrombolytic drug. Thrombus aspiration or removal consists of using hollow catheters of different calibers to aspirate the thrombus. This technique is highly dependent on the age the thrombus (more effective the more acute the case is) and the caliber of the aspiration catheter. Nonspecific material for coronary interventions (guide catheters of up to 8-Fr) or structural or peripheral heart procedures can be used (long introducers or sheaths > 8 Fr), with the advantage of its wide availability and low prices; the setback, however, is that the catheter usually becomes occluded, which is why it is often used in double ‘mother-and-child’ systems.

Also, there are 2 aspiration devices that have been specifically approved to treat PTE: the Indigo system (Penumbra, United States), a 115 cm 8-Fr angled tipped catheter with an olive-shaped burr to facilitate the entry and advancement of the thrombus, which will soon will be available in 12-Fr,1 and the FlowTriever system (Inari Medical, United States), specifically designed for PTE aspiration, and including a 24-Fr catheter, a 16-Fr guide catheter extension system, and a nitinol disc-shaped thrombus retriever. Its main advantage is that its outside connections are oversized at larger diameters compared to the Luer medical device standard.2 The Nautilus—a 10-Fr catheter system from iVascular, Spain—is currently in the pipeline. Other peripheral thrombectomy non-specific PTE devices like AngioVac (Angiodynamics, United States) or AngioJet (Boston Scientific, United States) are less common since more complications have been reported.

Compared to local thrombolysis, the advantages of MT by strong aspiration are that it can facilitate the patients’ rapid hemodynamic improvement, also ending in a single procedure that can prevent the use of fibrinolytic agents when used as monotherapy.

Local thrombolysis (LT) consists of introducing 1 or 2 usually multiperforated catheters into the pulmonary artery and in the intra-thrombus position through which 1 variable dose (around 25% of the systemic dose) of a fibrinolytic agent (often rt-PA) is introduced for a certain time (6 h to 24 h) with or without an initial bolus. Its main advantages are that it is easy to use, the possibility of using peripheral vascular access (antecubital vein or veins), and its low cost (a pig-tail catheter can be used). There is an ultrasound-facilitated LT (UFLT) device manufactured by EKOS (Boston Scientific, United States) that comes with a catheter with multiple ultrasound pulse generators to facilitate the fragmentation the fibrin threads while improving drug penetration into the thrombus.

Finally, the combination of MT1 plus LT is based on the principle that MT can act upon the most proximal segments of pulmonary and lobar branches while LT can later act upon lower caliber branches in the entire pulmonary tree.

Q.: What is the clinical evidence available on intravascular thrombolysis and thrombus aspiration therapies?

A.: Most historic evidence on CDT comes from registries and case series. However, over the last few years, the development of specific devices has produced new and high-quality pieces of evidence. There are still gaps of knowledge on the use of CDT to treat high-risk PTE (scarce and heterogeneous data), and comparative data on the different CDT techniques available.

Several registries prior to the development of specific devices like the PERFECT showed, for the very first time, better clinical outcomes with low rates of bleeding too. A meta-analysis of multiple trials on CDT conducted over the last decade provides aggregate data of 1168 patients showing overall rates of procedural success (95% confidence interval [95%CI], 72.5-89.1%), 30-day mortality (95%CI, 3.2-14.0%), and major bleeding (95%CI, 1.0-15.3%) of 81.3%, 8.0%, and 6.7%, respectively, in high-risk PTE. In intermediate-risk PTE, the rates of procedural success (95%CI, 95.3-99.1%), 30-day mortality (95%CI, 0%-0.5%), and major bleeding (95%CI, 0.3-2.8%) were 97.5%, 0% and > 1.4%, respectively.4

MT (aspiration) with the Indigo device was included in the single arm EXTRACT-PE clinical trial5 of 119 patients with intermediate-risk PTE. The efficacy (a 0.43 reduction in the right ventricle/left ventricle (RV/LV) ratio at 48 hours) and safety profile (rates of major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage of 1.7%, and 0%, respectively) was confirmed in a protocol with almost non-use of LT (98.3%). The FlowTriever device was used to conduct the FLARE trial6 of 106 intermediate-risk patients treated without thrombolytic drugs. The device proved its efficacy (a reduction of 0.38 in the RV/LV ratio at 48 hours) and safety profile (rates of major adverse events, major bleeding, and intracranial hemorrhage of 3.8%, 1%, and 0%, respectively). These results were confirmed in the first 250 patients of the FLASH registry7 with a rate of major adverse events of 1.2% (3 hemorrhages, none of them intracranial).

The EKOS device was studied in the ULTIMA randomized clinical trial8 of 59 patients with acute intermediate-risk PTE and a RV/LV ratio > 1 who were randomized to receive fixed doses of rt-PA (10 mg or 20 mg in bilaterals) in UFLT. It confirmed further reductions of the RV/LV ratio at 24 hours compared to standard therapy with heparin (mean reduction of 0.30 ± 0.20 vs 0.03 ± 0.16 (P < .001). The SEATTLE II registry9 of 150 patients most of them with submassive PTE demonstrated a similar efficacy profile with reasonable safety data (rates of 30-day major bleeding and intracranial hemorrhage of 10% and 0%, respectively).

The only comparative randomized clinical trial published to this date of 2 CDT strategies is the SUNSET sPE10 that found no differences in the radiologic thrombus load reduction with UFLT or simple LT with similar doses of thrombolytic drugs.

Q.: What are today’s indications for invasive treatment and how does the routine clinical practice at your center look like?

A.: In the clinical practice guidelines published by the European Society of Cardiology in 2019, CDT is given an indication IIa, level of evidence C, for patients with high-risk PTE in whom systemic thrombolysis (ST) is contraindicated or in cases when it has failed. Also, these guidelines rank CDT as an alternative to ST as a bailout therapy in patients initially treated with anticoagulation (often intermediate-high-risk PTE) with hemodynamic impairment (indication IIa, level of evidence C).

The alternative to CDT with a similar indication but a higher level of recommendation (indication I – level of evidence C) is surgical embolectomy. However, the availability of surgical teams ready to operate on these patients is very limited, as well as evidence compared to CDT.

In some centers with PTE response teams, CDT is used to treat intermediate-risk PTE (often intermediate-high-risk PTE) as coadjuvant therapy to anticoagulation. Still, there is not such a thing as a formal indication for ST. This strategy is based on studies that show that surrogate parameters like right ventricular function improve faster. However, there is no solid evidence regarding improved clinical parameters compared to anticoagulation therapy only.

Added to the indications approved in the European clinical guidelines, at our center, CDT is used in patients with an indication for LT and high risk of bleeding. Evidence shows that 30% to 50% of the patients with an indication for ST won’t receive this therapy afraid that complications will arise (basically severe or intracranial hemorrhages). Factors associated with high risk of bleeding in ST studies are active neoplasms, age ≥ 75 years, low weight (< 50 kg), acute kidney injury (glomerular filtration rate < 30) or active anticoagulation. These patients can benefit from CDT thanks to their lower risk of bleeding—particularly intracranial—based on data of indirect comparisons with ST.

Q.: Please tell us which trials are currently in the pipeline assessing these invasive strategies.

A.: Scientific societies have been developing European multicenter registries like EuroPE-CDT and NCT04037423 and, at national level, the TROMPA registry that is backed by the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.11

Several studies have already been started by device manufactures and are currently in the pipeline. Regarding the MT strategy, the Indigo device is being studied to collect efficacy, safety, and functional recovery data from 600 patients selected in the already started STRIKE-PE registry (NCT04798261). There is also an active registry currently recruiting patients to test the FlowTriever device that will include 1300 participants (FLASH, NCT03761173). Also, the upcoming PEERLESS clinical trial (NCT05111613) will recruit 550 patients with PTE and intermediate-high risk who will be randomized to receive the FlowTriever aspiration system or CDT based on the local routine clinical practice with other devices available in the market. The study primary endpoint will be death, intracranial hemorrhage, major bleeding, clinical impairment or length of stay at an intensive care unit.

The most relevant studies that are being conducted on the EKOS device are the KNOCOUT PE registry (NCT03426124)—in a phase of active recruitment—that will include up to 1500 patients, and the HI-PEITHO trial (NCT04790370). The latter is an international, prospective, multicenter clinical trial that will be comparing anticoagulation vs anticoagulation plus UFLT. The study primary endpoint is a composite of PTE-related mortality, cardiorespiratory decompensation or nonfatal PTE recurrence at 7 days. We should also mention the NCT03581877 trial (Peripheral systemic thrombolysis vs catheter-directed thrombolysis for submassive PE) that is comparing UFLT vs the same dose (24 mg) of rt-PA administered via peripheral vein for 12 hours.

Today’s challenges regarding research are to define procedural success, standardize the endpoints of clinical trials, and establish what intermediate-risk patients with PTE may benefit the most from CDT compared to standard therapy.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. De Gregorio MA, Guirola JA, Kuo WT, et al. Catheter-directed aspiration thrombectomy and low-dose thrombolysis for patients with acute unstable pulmonary embolism: Prospective outcomes from a PE registry. Int J Cardiol. 2019;287:106-110.

2. Salinas, P. Tromboaspiración con sistema FlowTriever en embolia pulmonar aguda. Med Clin (Barc). 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcli.2022.02.022.

3. Kuo WT, Banerjee A, Kim PS, et al. Pulmonary Embolism Response to Fragmentation, Embolectomy, and Catheter Thrombolysis (PERFECT): Initial Results From a Prospective Multicenter Registry. Chest. 2015;148:667-673.

4. Avgerinos ED, Saadeddin Z, Abou Ali AN, et al. A meta-analysis of outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis for high- and intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2018;6:530-540.

5. Sista AK, Horowitz JM, Tapson VF, et al. Indigo Aspiration System for Treatment of Pulmonary Embolism. JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions. 2021;14:319-329.

6. Tu T, Toma C, Tapson VF, et al. A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Catheter-Directed Mechanical Thrombectomy for Intermediate-Risk Acute Pulmonary Embolism: The FLARE Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:859-869.

7. Toma C, Bunte MC, Cho KH, et al. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy in a real-world pulmonary embolism population: Interim results of the FLASH registry. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions. 2022;99:1345-1355.

8. Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Müller OJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479-486.

9. A Prospective, Single-Arm, Multicenter Trial of Ultrasound-Facilitated, Catheter-Directed, Low-Dose Fibrinolysis for Acute Massive and Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SEATTLE II Study - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26315743/. Accessed 20 Feb 2022.

10.Avgerinos ED, Jaber W, Lacomis J, et al. Randomized Trial Comparing Standard Versus Ultrasound-Assisted Thrombolysis for Submassive Pulmonary Embolism: The SUNSET sPE Trial. Cardiovascular Interventions. 2021;14(12):1364-1373.

11. Registro TROMPA | SHCI - Sección de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista de la SEC (Sociedad Española de Cardiología). Available online: https://www.hemodinamica.com/cientifico/registros-y-trabajos/registros-y-trabajos-actuales/registro-trompa/. Accessed 20 Feb 2022.

QUESTION: In the current management of acute pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE) to what extent is thrombolytic therapy used? and what about invasive therapy?

ANSWER: During the early management of PTE, we’re going after the clinical stabilization of the patient and the alleviation of symptoms, the resolution of vascular obstruction, and the prevention of thrombotic recurrences. The priority of these goals depends on the severity of the patient. Most times (over 90%) these goals can be achieved using conventional anticoagulant treatment to stop the progression of the thrombus while the patient’s endogenous fibrinolytic system resolves the vascular obstruction developing collateral circulation. In a minority of the patients (5% to 10%)—often those with hemodynamic instability (high-risk PTE)—aggressive therapies (of reperfusion) can be used to resuscitate the patient or accelerate the lysis of the blood clot.

When reperfusion therapy is advised for a patient with symptomatic acute PTE, the clinical practice guidelines recommend the use of full-dose systemic fibrinolysis as long as it has not been contraindicated.1 Some of the reasons behind this recommendation are:

- a) Numerous clinical trials (with over 2000 patients included) have assessed the efficacy and safety profile of systemic fibrinolysis (compared to anticoagulation) demonstrating a statistically significant drop of the mortality rate. On the other hand, to this date, only 1 clinical trial has been published assessing the efficacy and safety profile of a catheter-directed treatment (ultrasound enhancement fibrinolysis) in 59 patients with acute PTE and echocardiographic dilatation of the right ventricle.2 The trial used an event of echocardiographic result and was not statistically powered to detect any differences regarding clinical events (mortality, thrombotic recurrences or bleeding).

- b) Percutaneous (local fibrinolysis, embolectomy or a combination of different techniques) and surgical (embolectomy) therapies require infrastructure and experience before they can be applied, and most centers and clinicians who often treat these patients just don’t have what it takes.

Q: Regarding invasive therapy, to what extent is it surgical or percutaneous nowadays?

A: RIETE3 is a real-world, multicenter, and international registry—led by Dr. Manuel Monreal Bosch—of consecutive patients diagnosed with deep venous thrombosis or symptomatic acute PTE. Recent analyses indicate that only 20% of hemodynamically unstable patients with PTE receive reperfusion treatment. Most of these patients (87%) receive systemic fibrinolysis, 10% surgical embolectomy, and 3% percutaneous treatments.

Q: On cardiac catheterization, which is the clinical evidence available regarding intravascular thrombolysis? and regarding thrombus aspiration therapies?

A: The evidence available on the use of percutaneous treatments is still very weak. As I said only 1 clinical trial has been published to this date on the efficacy and safety profile of a catheter-directed therapy (ultrasound enhancement fibrinolysis) in 59 patients with acute PTE and echocardiographic dilatation of the right ventricle (see answer #1).2 Recently, the findings of the prospective FLASH registry have been published including 250 patients treated with percutaneous thrombectomy through the FlowTriever system.4 A total of 3 serious adverse events occurred (1.2%)—all of the severe hemorrhages—that resolved uneventfully. The 30-day all-cause mortality rate was 0.2% (1 death unrelated to PTE). Although the results of clinical registries—that are hypothesis-generating—provide useful medical information, they are no stranger to several biases and confounding factors, which is why they should not be used on a routine basis to assess the efficacy and safety profile of medical procedures. Currently, intermediate-high risk patients are being recruited (sample size, 406-544) with intermediate-high risk PTE for the HI-PEITHO clinical trial. These patients are being randomized to receive conventional anticoagulation or anticoagulation plus ultrasound enhancement local fibrinolysis. The efficacy primary endpoint is assessed by an independent committee 1 week after randomization includes PTE-related death, thrombotic recurrence or hemodynamic collapse.

Q: What are today’s indications for invasive treatment, and how does your center work in this sense? how important is bleeding risk in the decision-making process?

A: At our center we have a PTE code for making decisions on the management of patients with severe PTE (especially high and intermediate-high risk patients). Overall, we follow the recommendations from the Spanish multidisciplinary consensus recently published in Archivos de Bronconeumología.5 We use full-dose systemic fibrinolysis in patients with an indication for reperfusion and without contraindications for use. In patients with an indication for reperfusion and relative contraindications—minor—for full-dose systemic fibrinolysis we use catheter-directed percutaneous treatment (percutaneous thrombectomy, local fibrinolysis or both) or low-dose systemic fibrinolysis. In patients with symptomatic acute PTE, an indication for reperfusion treatment and absolute contraindication for full-dose systemic fibrinolysis we use surgical embolectomy or catheter-directed percutaneous treatment (percutaneous thrombectomy).

From this we can deduce that assessing the bleeding risk is key regarding decision making with reperfusion therapies. In our clinical practice we use the BACS (Bleeding, Age, Cancer, Syncope) scale to identify patients with very low risk of bleeding after the administration of full-dose systemic fibrinolysis.

Q: Can you tell us something on what’s coming in this field, in particular any ongoing studies you think are relevant?

A: As I already mentioned, the HI-PEITHO clinical trial is studying the efficacy and safety profile of ultrasound enhancement local fibrinolysis in intermediate-high risk patients with PTE. Additionally, the PEITHO III clinical trial is currently randomizing intermediate-high risk patients with PTE to receive low-dose systemic fibrinolysis (r-TPA at doses of 0.6 mg/kg up to a maximum of 50 mg) or placebo plus conventional anticoagulation; the efficacy primary endpoint is the same as in the HI-PEITHO trial.

Also, clinical trials are being conducted to assess the efficacy and safety profile of other procedures (non-reperfusion therapies) in patients with severe PTE. In the DiPER clinical trial, a total of 276 patients were recruited to assess the efficacy and safety profile of diuretic therapy to treat PTE with right ventricular dysfunction.6 The administration of a bolus of furosemide improved diuresis and did not make renal function worse. The AIR clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04003116) is currently studying the efficacy and safety profile of the administration of oxygen to patients with PTE and right ventricular dysfunction.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

REFERENCES

1. Stevens SM, Woller SC, Baumann Kreuziger L, et al. Executive Summary: Antithrombotic Therapy for VTE Disease: Second Update of the CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021;160:2247-2259.

2. Kucher N, Boekstegers P, Muller OJ, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of ultrasound-assisted catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute intermediate-risk pulmonary embolism. Circulation. 2014;129:479-486.

3. Registro informatizado de pacientes con enfermedad tromboembólica en España (RIETE). Disponible en: https://www.riete.org/. Consultado 23 Feb 2022.

4. Toma C, Bunte MC, Cho KH, et al. Percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy in a real-world pulmonary embolism population: Interim results of the FLASH registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99:1345-1355.

5. Lobo JL, Alonso S, Arenas J, et al. Multidisciplinary Consensus for the Management of Pulmonary Thromboembolism. Arch Bronconeumol. 2021;58(3):246-254.

6. Lim P, Delmas C, Sanchez O, et al. Diuretic vs. placebo in intermediate-risk acute pulmonary embolism: a randomized clinical trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2022;11:2-9.

QUESTION: What is the prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) in your case series of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) to this date? And what’s the patients’ surgical risk?

ANSWER: Over 1000 TAVIs have already been performed at our center, and the prevalence of BAV stands at around 4.4%. It is greater compared to the Spanish TAVI registry where nearly 2% of the patients treated with TAVI have BAV.1 Thanks to the use of computed tomography scan as a systematic imaging modality to plan TAVI, its diagnosis has gone up. As a matter of fact, our group included the number of patients treated with TAVI or surgery in 2019 in 17 Spanish centers being the prevalence of BAV around 4.6%, and 16%, respectively. At times, the diagnosis of BAV is not an easy one, and when the heart valve is highly unstructured and calcified, it can go unnoticed. Therefore, it can be underdiagnosed in our series of TAVI. However, an «active» search can increase the number of diagnoses.

In our series the risk profile of these patients is intermediate-high. The mean age is 80 years old with a similar distribution by sex. The risk scores measured were the logistic EuroSCORE (14.8%), the EuroSCORE II (5.8%), and the STS (5.7%). However, these scores are influenced by the ones obtained in younger patients (< 75 years) that, although with lower scores, have proven inoperable or are very high-risk surgical patients (mainly due to a respiratory condition or hemodynamic instability).

Q.: What evidence do we have for TAVI to treat bicuspid aortic valve stenosis? Are the actual results equivalent to the ones reported for the non-bicuspid aortic valve?

A.: In short, I would say that although scarce (mainly from retrospective registries), evidence is mounting. The results coming from the oldest series were worse. However, they are currently similar with certain differences.

The evidence available on TAVI in the BAV aortic stenosis fall into 3 categories: a) TAVI in the BAV vs TAVI in the tricuspid valve; b) different types of TAVI in the BAV (TAVI vs TAVI), and c) TAVI vs surgery in the BAV.

The early studies showed that TAVI performed in the BAV had higher rates of paravalvular leak, embolization, need for second valve implantation, and a lower rate of successful device implantation. Thanks to the technical advances made and second and third-generation valves, these results have equalized. However, there is still a significant rate of stroke (2.5%) that is even higher compared to tricuspid valves.2 A meta-analysis demonstrated that the rate of paravalvular leak is still a little higher in self-expanding valves, as well as the rate of mechanical complications in balloon-expandable valves.3 No all valves are the same for the different anatomical and clinical settings. In the BAV only 1 retrospective registry has been published comparing the Edwards SAPIEN 3 valve (Edwards Lifesciences LLC, United States) to the Evolut R/Pro (Medtronic, United States). The outcomes were similar regarding mortality and stroke, but with higher rates of paravalvular leak and device embolization, and fewer overall events of successful implantation in the self-expanding valve group vs higher gradients (approximately 2 mmHg) in the balloon-expandable valve group.4 In the most recent series published on the SAPIEN 3 valve in the context of the Partner-3 trial, a group of patients with BAV was compared—after propensity score-based risk adjustment—to another group of patients with tricuspid valve. It turned out that the clinical outcomes overlapped in both (mortality and stroke rates of 0% and 1.4%, respectively at 30 days). We should mention that the CoreValve Evolut device achieved an indication in patients with BAV (based on the TVT registry5) while the SAPIEN 3 valve does not have a specific contraindication in this context in its instructions for use. However, the remaining valves available today are specifically contraindicated for BAV in the instructions for use. Finally, the outcomes of TAVI vs surgery in the BAV were published in 2 studies, one with in-hospital outcomes and the other with the outcomes reported at the 2-year median follow-up.6,7 Patients treated with TAVI had a higher rate of pacemaker implantation, and better data regarding bleeding, vascular complications, and lengths of stay with similar rates of in-hospital mortality and stroke at the 2-year follow-up. Therefore, although we still don’t have robust evidence that TAVI is superior to surgery regarding the BAV, there is no single piece of evidence that says that TAVI fares worse compared to surgery.

Q.: What special considerations should be made with TAVI when performed on the bicuspid aortic valve? Are there any anatomical variants with specific technical implications?

A.: The first consideration should be to know whether we are really talking about a BAV or not. Like I said, in heavily calcified and unstructured valves it can go unnoticed. For procedural planning purposes, it is essential to make a thorough assessment of the baseline computed tomography scan. It should provide us with detailed information on the valve and the ascending aorta to obtain optimal results. In the first place, we should know both the type of BAV (type 0, I or II) and its morphology. In highly asymmetrical type 0 valves with a heavily calcified raphe, the expansion of the valve can be inadequate (very elliptical) and affect the hemodynamic outcomes (due to gradients and paravalvular regurgitation). Also, both the location of the raphe and calcification per se can have an impact on the position of the valve that can move towards either one of the sinuses (with greater risk of coronary obstruction in case of displacement towards the left or the right sinus). We should mention that the presence of a calcified raphe plus excessive leaflet calcification has been associated with a higher mortality rate.8 The computed tomography scan can also be used to measure the right size of the valve both at annular and supra-annular level (intercommissural distance) always remembering that minimal valve oversizing is often necessary.

Once the right procedural planning is in place, the technical considerations on the day of the surgery should be:

-

–Avoid brain damage as much as possible and, if possible, always use cerebral protection devices.

-

–Use high support guidewires like Lunderquist (Cook Medical, United States) or Back-up Meier (Boston Scientific, United States) when treating tortuous aortas.

-

–Use the necessary time to locate the angiographic plane for implantation since it is often more complex compared to tricuspid valve cases.

-

–Always predilate (in most cases with the minimum diameter and without exceeding the medium) and watch the degree of balloon opening and calcium displacements from the leaflets towards the coronary arteries. The strategy of performing a simultaneous injection during predilation provides us with valuable information to analyze the risk of coronary occlusion and select the size of the valve.

-

–Select the right type of TAVI based on the patient’s characteristics. Self-expanding valves with less radial strength can remain underexpanded so before their implantation we should always acquire several projections to confirm their correct expansion. If there is a high risk of rupture in the annulus with an aggressive expansion, the Evolut Pro+ valve can be used. However, if the risk of aortic regurgitation is high, the SAPIEN 3 Ultra valve should rather be used. We should mention that these risks happen together and the trade-off is complex. The tortuosity of the aortic arch and the horizontally of the ascending aorta (very common in the BAV) can also help us select a flexible valve or with a deflectable catheter. Another significant aspect to select the type of valve is the operator’s experience.

-

–If postdilation is required (needed in over 50% of the cases with self-expanding valves), the balance between the rupture of the annulus and the leak should be observed when selecting the balloon size. On many occasions, the annuli of BAVs are large meaning that large balloons will also be needed (26 mm, 28 mm or 30 mm). Still, balloons this big are not always available at the cath lab.

Q.: Which cases with BAV do you think are clearly eligible for TAVI and which are not?

A.: This is a very relevant question because, like I said, evidence is scarce and barely any randomized trials have been published on this regard (at least in the short and mid-term) comparing TAVI to surgery in the BAV setting. Therefore, decisions should be made based on the operator’s experience and the local outcomes. When examining a patient with BAV for TAVI a series of clinical, and anatomical (or technical) aspects should be taken into consideration. The clinical features in favor of TAVI are the same as for tricuspid valves, that is, old, frail, and female patients (> 75 years) with comorbidities and lack of coronary artery disease or other concomitant valvular heart disease. The favorable anatomical aspects would be a suitable femoral access, type 1 bicuspid anatomy (versus type 0 and 2), small annuli, mild or moderate calcification, no dilatation of the ascending aorta, no calcification of the raphe, and no risk of coronary artery occlusion. I would use TAVI as the first-line therapy for high-risk frail or elderly patients. However, I would use surgery for young low-risk patients (< 70 years). It should be the job of the heart team to know how to deal with intermediate settings in each case like young patients with comorbidities and intermediate risk but with a favorable anatomy for TAVI or high-risk older patients with an unfavorable anatomy for TAVI. Something that should be studied based on the patients’ clinical and anatomical features is whether the long-term results of surgery are predominant compared to its immediate risks or if, on the contrary, TAVI less invasive approach is preferred in this balance even after obtaining suboptimal outcomes in highly unfavorable anatomies. Thanks to the technical advances made, the new valves available, and the experience gained with TAVI with careful procedural planning good results can be achieved even in complex settings. However, since a proportion of patients with BAV are young, we interventional cardiologists need to be aware of the heterogeneity of this disease, refine the technical details of implantation, and the selection of patients and devices to optimize results.

FUNDING

None reported

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

L. Nombela-Franco has received a research grant (INT19/00040) from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation (Instituto de Salud Carlos III), is a proctor for Abbott, and has received speaking fees from Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific.

REFERENCES

1. Jiménez-Quevedo P, Nombela-Franco L, Muñoz-García E, et al. Early clinical outcomes after transaxillary versus transfemoral TAVI. Data from the Spanish TAVI registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2021.07.019.

2. Makkar R, Yoon SH, Leon MB, et al. Association Between Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid vs Tricuspid Aortic Stenosis and Mortality or Stroke. JAMA. 2019;321:2193-2202.

3. Montalto C, Sticchi A, Crimi G, et al. Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Bicuspid Versus Tricuspid Anatomy:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:2144-2155.

4. Mangieri A, TchetchèD, Kim WK, et al. Balloon Versus Self-Expandable Valve for the Treatment of Bicuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis:Insights From the BEAT International Collaborative Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:e00∊.

5. Forrest JK, Kaple RK, Ramlawi B, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Bicuspid Versus Tricuspid Aortic Valves From the STS/ACC TVT Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1749-1759.

6. Yoon SH, Kim WK, Dhoble A, et al. Bicuspid Aortic Valve Morphology and Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1018-1030.

7. Elbadawi A, Saad M, Elgendy IY, et al. Temporal Trends and Outcomes of Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1811-1822.

8. Mentias A, Sarrazin MV, Desai MY, et al. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients With Bicuspid Aortic Valve Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2518-2519.

QUESTION: What is the prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve in the population currently eligible for surgical aortic valve replacement?

ANSWER: The prevalence of bicuspid aortic valve is around 1% to 2% of the population. Somewhere between 27% and 35% of the population will eventually require surgery at the 20-year follow-up.1 On the other hand, the associated dilatation of the ascending aorta, with conflicting results regarding its prevalence, stands at around 50% to 80%.1 At our center, 30% of all aortic valve replacements or repairs—with or without replacement of the ascending aorta—are performed on the bicuspid aortic valve. Also, this is a group of predominantly male patients with a mean age of 55 years, and different clinical features compared to the aortic stenosis described in elderly patients. Many of these patients are repaired when regurgitation is predominant with excellent clinical outcomes.

Q.: What special considerations should be made with surgery when performed on the bicuspid aortic valve?

A.: There are 3 special considerations that should be observed. In the first place, this condition affects a group of younger patients. Also, these valves have severe calcification posing great technical difficulties regarding decalcification for correct implantation under direct vison. On many occasions, eventually, the ascending aorta needs to be replaced. According to the clinical practice guidelines from the European medical societies on cardiology and thoracic surgery, the ascending aorta needs to be replaced if it is longer than 45 mm in the presence of associated valve replacement. The indication for isolated aneurysm without valvular lesion is 50 mm in the presence of associated risk factors (arterial hypertension, past medical history of dissection or aortic syndrome).2

Q.: Do you think that severe aortic stenosis in the bicuspid aortic valve is an indication for surgery per se regardless of the surgical risk?

A.: I do for the reasons I already gave you on the special characteristics of this condition that, in most cases, require surgery. The main reason is that it affects younger patients in whom other therapeutic options have not been validate with 10+year follow-ups. Other less important reasons are severe calcification, repair possibilities in the presence of double valvular lesion, and quite often, the need to replace the ascending aorta.

Q.: In your opinion, which are the cases of severe bicuspid aortic stenosis clearly eligible for surgery and which are ineligible?

A.: In principle, preferably, all cases should be treated surgically. Other options can be considered only in patients in whom surgery is contraindicated, although the evidence available on this matter is still weak. Studies on transcatheter aortic valve implantation include elderly patients with aortic stenosis. According to the European clinical practice guidelines, patients over 75 with comorbidities can be treated percutaneously. However, the severe associated calcification, and lack of scientific evidence should always be taken into consideration.3

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None whatsoever.

REFERENCES

1. Detaint D, Michelena HI, Nkomo VT, Vahanian A, Jondeau G, Sarano ME. Aortic dilatation patterns and rates in adults with bicuspid aortic valves:a comparative study with Marfan syndrome and degenerative aortopathy. Heart. 2014;100:126-134.

2. Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, et al. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases:Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873-2926.

3. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group;ESC Scientific Document Group. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561–632.

- Debate: Ischemia without obstructive coronary artery disease. An invasive coronary physiological macro- and microvascular assessment is necessary

- Debate: Ischemia without obstructive coronary artery disease. A non-invasive assessment may be sufficient in some cases

- Debate: Minimalist approach to TAVI as a default strategy

- Debate: Minimalist approach to TAVI as a selective strategy

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

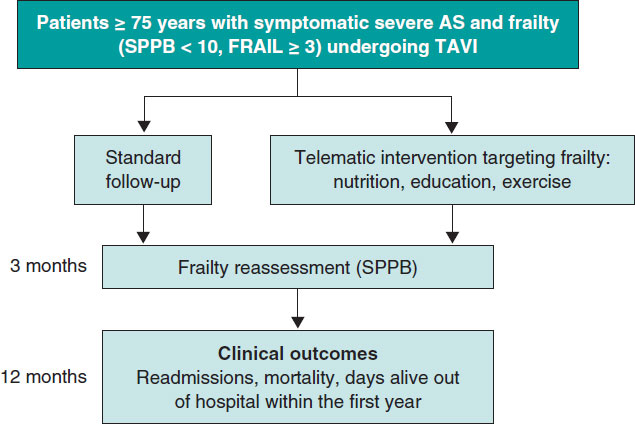

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España