Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

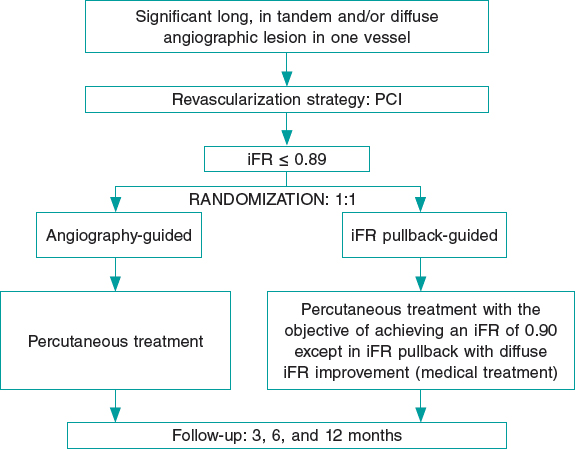

Introduction and objectives: The objective of this study was to describe our experience with coronary physiology assessment using the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) and/or a Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study [Syncvision version 4.1.0.5, Philips Volcano, Belgium] in all-comer patients.

Methods: Consecutive patients undergoing coronary physiology assessment with the iFR (and/or a Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study) at our center between January 2017 and December 2019 were included. The iFR cut-off value was 0.89. The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, probable or definitive stent thrombosis, and target lesion revascularization.

Results: A total of 277 patients with 433 lesions evaluated were included. The mean age was 65 ± 10 years and 74% were men. Personal history of diabetes mellitus was present in 41% of patients. Clinical presentation was stable angina in 160 patients (58%), and acute coronary syndrome in 117 patients (42%). iFRs > 0.89 were obtained in 266 lesions (61.4%) on which the PCI was postponed. The remaining lesions were revascularized. The Syncvision software was used to guide the iFR-pullback study in 155 lesions (36%) and the decision-making process, mainly in long, diffuse or sequential lesions (91 lesions, 58.7%), and intermediate lesions (52 lesions, 33.5%). After a median follow-up of 18 months, the primary endpoint occurred in 17 patients (6.1%) without differences regarding the baseline iFR (≤ 0.89 or > 0.89) (4.2% vs 3.8%; P = .9) or the clinical presentation (stable angina or acute coronary syndrome) (4.4% vs 8.5%; P = .1)

Conclusions: The use of coronary physiology assessment with the iFR and the Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study in the routine daily practice and in all-comer patients seems safe with a low percentage of major adverse cardiovascular events at the mid-term follow-up.

Keywords: Physiological assessment. All-comer patients. Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El propósito del estudio fue describir nuestra experiencia con el uso del índice diastólico instantáneo sin ondas (iFR) para la evaluación fisiológica coronaria o el uso del software Syncvision/iFR (Syncvision versión 4.1.0.5, Philips Volcano, Bélgica) en todo tipo de pacientes.

Métodos: Se incluyeron todos los pacientes consecutivos a quienes, entre enero de 2017 y diciembre de 2019, se realizó en nuestro centro una evaluación fisiológica coronaria con iFR o con Syncvision/iFR. El valor de corte establecido para el iFR fue 0,89. El objetivo primario fue un compuesto de muerte cardiaca, infarto de miocardio, trombosis de stent probable o definitiva y nueva revascularización de la lesión evaluada.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 277 pacientes con 433 lesiones evaluadas. La edad media fue de 65 ± 10 años y el 74% eran varones. El 41% tenía antecedente de diabetes mellitus. La presentación clínica fue angina estable en 160 pacientes (58%) y síndrome coronario agudo en 117 pacientes (42%). Se obtuvo un iFR > 0,89 en 266 lesiones (61,4%), en las cuales la intervención coronaria percutánea fue diferida. Las lesiones restantes se revascularizaron. El software Syncvision/iFR se usó en 155 lesiones (36%) para guiar la toma de decisiones, principalmente lesiones largas, difusas o secuenciales (91 lesiones, 58,7%) y lesiones intermedias (52 lesiones, 33,5%). Tras un periodo de seguimiento de 18 meses, el objetivo primario se observó en 17 pacientes (6,1%), sin diferencias en función del iFR basal (≤ 0,89 o > 0,89) (4,2 frente a 3,8%; p = 0,9) ni de la presentación clínica (angina estable o síndrome coronario agudo) (4,4 frente a 8,5%; p = 0,1).

Conclusiones: La evaluación fisiológica coronaria con iFR y el software Syncvision/iFR en la práctica diaria y en todo tipo de pacientes parece ser segura, con un bajo porcentaje de eventos cardiacos adversos mayores a medio plazo.

Palabras clave: Evaluacion fisiologica. Todo tipo de pacientes. Software Syncvision/iFR.

Abbreviations

iFR: instantaneous wave-free ratio. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events.

INTRODUCTION

Physiological assessment using the fractional flow reserve (FFR) or the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) is strongly recommended by the European guidelines to the guide percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) decision-making process to treat intermediate coronary stenosis (indication I, level of evidence A) and multivessel disease (indication IIa, level of evidence B).1-7

The established cut-off values based on landmark trials to safely postpone treatment of a coronary lesion are FFRs > 0.80 and iFRs > 0.89.2-7 Unlike the FFR, the new iFR resting index allows us to analyze the physiological significance of each segment in the presence of coronary arteries with several lesions. Syncvision is a new software that analyzes the specific contribution of each coronary segment allowing us to predict physiological improvement after percutaneous treatment.8,9 It’s not necessary to use any vasodilators either, thus reducing any potential side effects.3,4

However, the evidence supporting the use of coronary physiology assessment with both indices and the use of the Syncvision software in other type of lesions and other clinical scenarios is scarce.8-10 For this reason, it is not quite clear whether the same cut-off value established in the landmark trials should be used; or if safety, utility, and efficacy will be the same.

The objective of this study is to describe our experience with coronary physiology assessment using the iFR (and/or the Syncvision- guided iFR-pullback study) in all-comer patients undergoing invasive coronary angiography.

METHODS

We performed a single-center retrospective study including all patients who underwent functional assessments (using the iFR) and/or the Syncvision software at our center between January 2017 and December 2019 on a PCI decision-making process. The cut-off value to consider the need for revascularization was the same one established by the landmark clinical trials (iFR ≤ 0.89).3,4 The pressure guidewires used for the functional assessment were the Volcano Verrata, and the Volcano Verrata Plus (Philips Volcano, Belgium). The use of the Syncvision software to guide the iFR study as well as the lesions assessed were left to the operator’s discretion.

All subjects included in the study gave their informed consent to undergo the procedure and for data analysis and publication. Additionally, the study received the proper ethical oversight and was approved by our center ethics committee.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with the following criteria were included: a) consecutive patients in whom an invasive coronary angiography was performed due to stable or unstable symptoms or silent ischemia; b) presence of, at least, a lesion or vessel physiologically assessed with the iFR during the index procedure. The following exclusion criteria were stablished: a) impossibility to understand the informed consent during the index procedure; b) written informed consent to use data for research purposes not provided.

Lesion classification

The lesions physiologically assessed were classified based on their angiographic characteristics and/or clinical setting: a) intermediate lesions: lesions with a 40% to 80% angiographic stenosis as seen on the quantitative coronary angiography (QCA); b) sequential or diffuse coronary lesions: presence of, at least, 2 sequential lesions or a coronary segment with diffuse disease (coronary vessel with multiple plaques in most of the epicardial territory) with a total length of 25 mm; c) bifurcation lesions: presence of a coronary stenosis at bifurcation level with a side branch size large enough to be protected; d) in-stent restenosis: presence of focal or diffuse in-stent restenosis with a a 40% to 80% angiographic stenosis as seen on the QCA; e) coronary bypass lesion, defined as, at least, a lesion in the coronary artery bypass grafting or native vessel presenting with proximal total occlusion.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint of the study was the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at the follow-up. The MACE were defined as a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction (MI), definitive or probable stent thrombosis, and new target lesion revascularization (TLR). All deaths were considered cardiovascular unless unequivocal non-cardiac causes would be established. Myocardial infarction included spontaneous ST-segment elevation MI or non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. The TLR was defined as a new revascularization of a baseline physiologically negative lesion at the follow-up or as a repeat revascularization of a baseline physiologically positive lesion percutaneously treated during the index procedure.

The secondary endpoints established were: a) analysis of the primary endpoint components separately; b) rate of MACE based on the clinical setting (stable angina or acute coronary syndrome), non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), and ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); c) rate of MACE based on the baseline iFR; d) to determine the type of lesions where the Syncvision software was used for the iFR-pullback study.

Follow-up

The patients’ follow-up was performed through phone calls, hospital record reviews or outpatient visits.

Quantitative coronary measurements

Quantitative coronary measurements were performed using a validated system (CAAS system, Pied Medica Imaging, The Netherlands). These were the measurements analyzed: reference vessel diameter, minimum lumen diameter, percent diameter stenosis, and lesion length. All measurements were performed at baseline and after the PCI.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and the Student t test was used to establish comparisons. The categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and compared using the chi-square test. The univariate analysis was performed with the following covariates: age, male sex, current smoking status, dyslipidemia, left ventricular ejection fraction, acute coronary syndrome, multivessel disease, clopidogrel, ticagrelor, right coronary artery as the study vessel, other vessels analyzed, and baseline iFRs ≤ 0.89. Results were reported using odds ratios (OR), and two-sided 95% confidence intervals. In all the cases, P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analysis was performed using the IBM-SPSS statistical software package (version 24.0 for Macintosh, SPSS Corp., United States).

RESULTS

The study flowchart is shown on figure 1. During the study period, a total of 2951 patients underwent coronary angiography at our center. The iFR-based physiological assessment was performed in 277 patients (9.4%) with 433 lesions. The baseline clinical data are shown on table 1. The mean age was 65 ± 10 years, and 74% of the patients (204) were men. The prevalence of comorbidities was high (diabetes mellitus, 41%; previous MI, 32%; peripheral arterial disease, 4%; cerebrovascular disease, 6%; chronic kidney disease, 13%). The clinical presentation included stable angina in 160 patients (58%), NSTEMI in 91 patients (33%), and STEMI in 26 patients (9%).

Table 1. Baseline clinical data

| Patients | Total (N = 277) | Stable angina (N = 160) | ACS (N = 117) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65 ± 10 | 65 ± 10 | 64 ± 11 | .071 |

| Sex, male, N (%) | 204 (74) | 116 (72) | 94 (80) | .112 |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 175 (63) | 101 (63) | 77 (66) | .645 |

| Diabetes mellitus, N (%) | 114 (41) | 58 (36) | 52 (44) | .169 |

| Dyslipidemia, N (%) | 157 (57) | 101 (63) | 58 (50) | .024 |

| Current smoker, N (%) | 72 (26) | 29 (18) | 42 (36) | .001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction, N (%) | 89 (32) | 53 (33) | 37 (32) | .792 |

| Previous revascularization, N (%) | 94 (34) | 50 (31) | 32 (27) | .518 |

| Percutaneous, N (%) | 80 (85) | 50 (31) | 30 (26) | .336 |

| Surgical, N (%) | 14 (15) | 8 (16) | 6 (19) | .095 |

| Atrial fibrillation, N (%) | 39 (14) | 19 (12) | 13 (11) | .844 |

| Heart failure, N (%) | 8 (3) | 7 (4) | 2 (2) | .216 |

| Prior ACE, N (%) | 17 (6) | 11 (7) | 9 (8) | .795 |

| Peripheral arterial disease, N (%) | 11 (4) | 7 (4) | 5 (4) | .967 |

| Previous bleeding, N (%) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (2) | .752 |

| Chronic kidney disease, N (%) | 36 (13) | 19 (12) | 17 (15) | .486 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.96 ± 1.7 | 13.87 ± 1.8 | 14.13 ± 1.8 | .365 |

| Creatinine, g/dL | 0.98 ± 0.47 | 1 ± 0.63 | 1 ± 0.37 | .584 |

| Left fentricular ejection fraction, % | 59 ± 15 | 57 ± 16 | 60 ± 13 | .098 |

|

ACE, acute cerebrovascular event; ACS, acute coronary syndrome. Data are expressed as number (N) and percentage (%). |

||||

Angiographic and procedural data

Angiographic and procedural data are shown on table 2. Radial access was the access of choice in most of the cases (392 lesions, 91%). A total of 186 patients (67%) showed angiographic multivessel disease. Regarding the angiographic Syntax I score, 232 patients (84%) had Syntax scores < 22, 41 patients (15%) between 22 and 32, and only 4 patients (1%) > 32 without any differences being reported between stable and unstable patients. The vessel most frequently analyzed was the left anterior descending coronary artery (180, 42%) followed by the right coronary artery (99, 23%). The left main coronary artery was evaluated in 23 patients (5%).

Table 2. Angiographic and procedural data

| Patients | Total (N = 277) | Stable angina (N = 160) | ACS (N = 117) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radial access, N (%) | 251 (90) | 147 (92) | 104 (89) | .329 |

| Multivessel disease, N (%) | 165 (59) | 84 (52) | 81 (69) | .004 |

| Syntax score | 11 ± 8 | 10 ± 8 | 12 ± 8 | .885 |

| Low risk (< 22) | 45 (16) | 25 (16) | 20 (17) | .184 |

| Intermediate risk (22-32) | 6 (2) | 1 (1) | 5 (4) | .066 |

| High risk (> 32) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | .331 |

| Acetylsalicylic acid, N (%) | 245 (88) | 142 (88) | 103 (88) | .740 |

| P2Y12 inhibitor, N (%) | 195 (71) | 98 (61) | 97 (83) | |

| Clopidogrel | 63 (23) | 40 (25) | 23 (20) | .011 |

| Ticagrelor | 127 (46) | 56 (35) | 71 (61) | .019 |

| Prasugrel | 65 (2) | 2 (1) | 3 (3) | .642 |

| Vessel analyzed, N (%) | ||||

| LAD | 121 (44) | 66 (41) | 55 (47) | .318 |

| LCx | 40 (14) | 26 (16) | 14 (12) | .327 |

| RCA | 75 (27) | 50 (31) | 25 (21) | .072 |

| LMCA | 15 (5) | 8 (5) | 7 (6) | .712 |

| Other | 27 (10) | 11 (7) | 16 (14) | .057 |

| Reference vessel diameter (mm) | 3.3 ± 3 | 3.3 ± 3 | 3.3 ± 3 | .971 |

| Vessel stenosis (%) | 49 ± 16 | 49 ± 17 | 49 ± 16 | .816 |

| Vessel minimal lumen diameter (mm) | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | .203 |

| Vessel lesion length (mm) | 21 ± 12 | 21 ± 13 | 20 ± 11 | .174 |

| Vessel stent diameter (mm) | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | .581 |

| Type of stent implanted (%) | ||||

| DES | 100 | |||

| BMS | 0 | |||

| Other | 0 | |||

| Immediate angiographic optimal result (%) | 100 | |||

| Contrast used (mL) | 142 ± 91 | 151 ± 110 | 164 ± 72 | .166 |

| Intracoronary imaging, N (%) | 6 (2) | 6 (4) | 0 | .034 |

| Procedural complications, N (%) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | .754 |

| Baseline iFR | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 0.89 ± 0.12 | 0.86 ± 0.14 | .097 |

| Final iFR | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | 0.93 ± 0.04 | .951 |

| Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study, N (%) | 155 lesions (36) | 94 lesions (36) | 61 lesions (35) | .4 |

| Lesions evaluated | Total (N = 433) | Stable angina (N = 258) | ACS (N = 175) | P |

| Angiographically moderate lesions, N (%) | 244 (56.4) | 149 (58) | 95 (54) | .475 |

| Sequential/diffuse coronary lesions, N (%) | 118 (27.3) | 64 (25) | 53 (30) | .208 |

| Bifurcation lesions, N (%) | 51 (11.8) | 31 (12) | 20 (11) | .853 |

| In-stent restenosis, N (%) | 15 (3.5) | 11 (4.3) | 4 (2.3) | .269 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting, N (%) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | .085 |

| Other lesions, N (%) | 3 (0.75) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.6) | .802 |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; BMS, bare metal stent; DES, drug-eluting stent; iFR, instantaneous wave-free ratio; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery. Data are expressed as number (N) and percentage (%). |

||||

The mean reference diameter was 3.3 mm ± 3 mm with a mean vessel stenosis of 49% ± 16%, and a mean lesion length of 21 mm ± 12 mm. The mean diameter of the stent implanted was 2.8 ± 0.4. All the stents implanted were drug-eluting stents (100%). Intracoronary imaging was used in 14 patients (3%).

The instantaneous wave-free ratio was obtained in 433 lesions, with a baseline value of 0.89 ± 0.12. The physiological assessment results after the PCI were obtained in 129 lesions (29.8%) with a final iFR of 0.93 ± 0.04.

The lesions physiologically assessed are shown on table 2. The most common type of lesions undergoing physiological assessment were angiographically moderate lesions (244, 56.4%) followed by sequential and diffuse lesions (118, 27.3%). Physiological assessment was used in 51 bifurcation lesions (11.8%) basically to guide the intervention over the side branch while using a provisional stenting strategy.

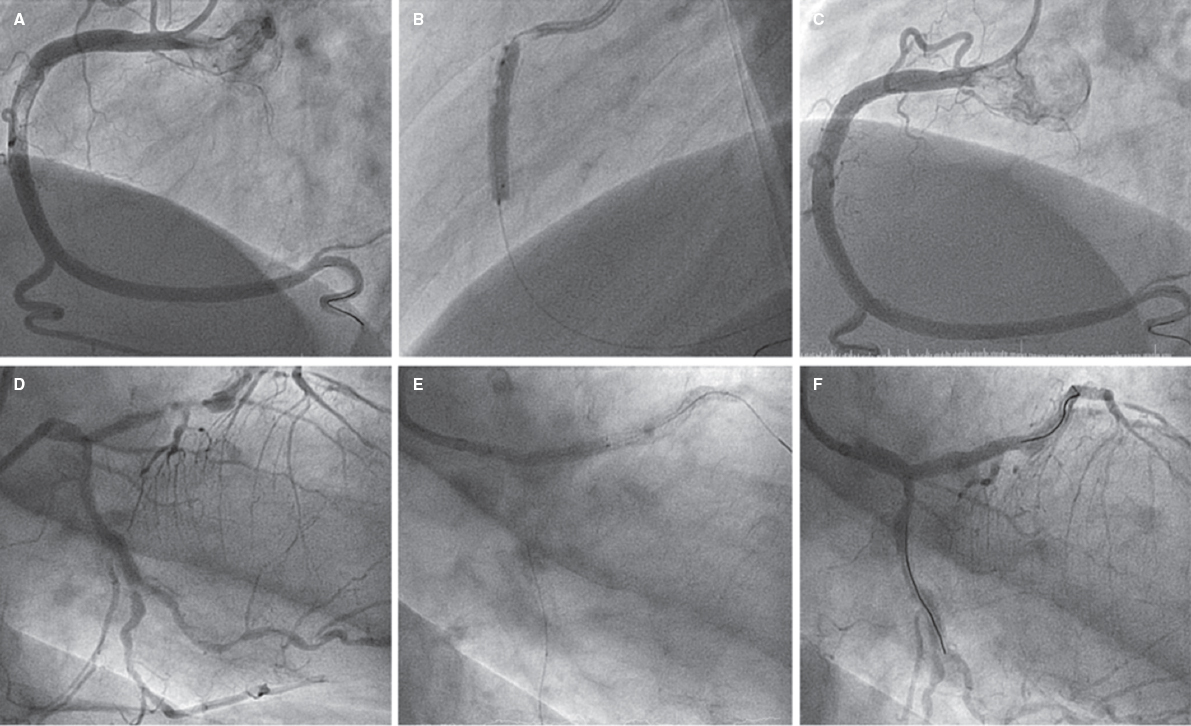

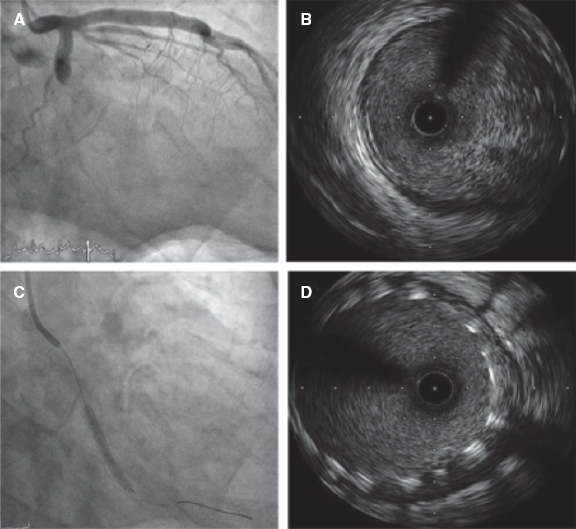

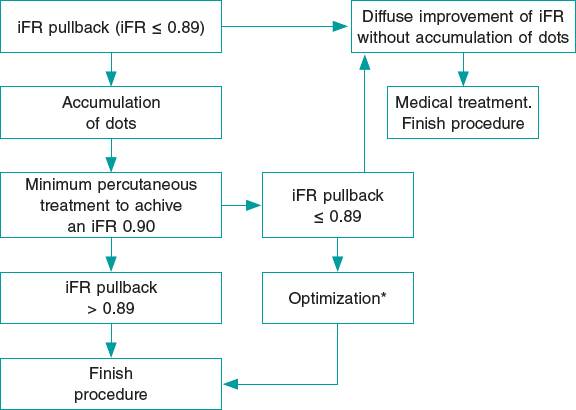

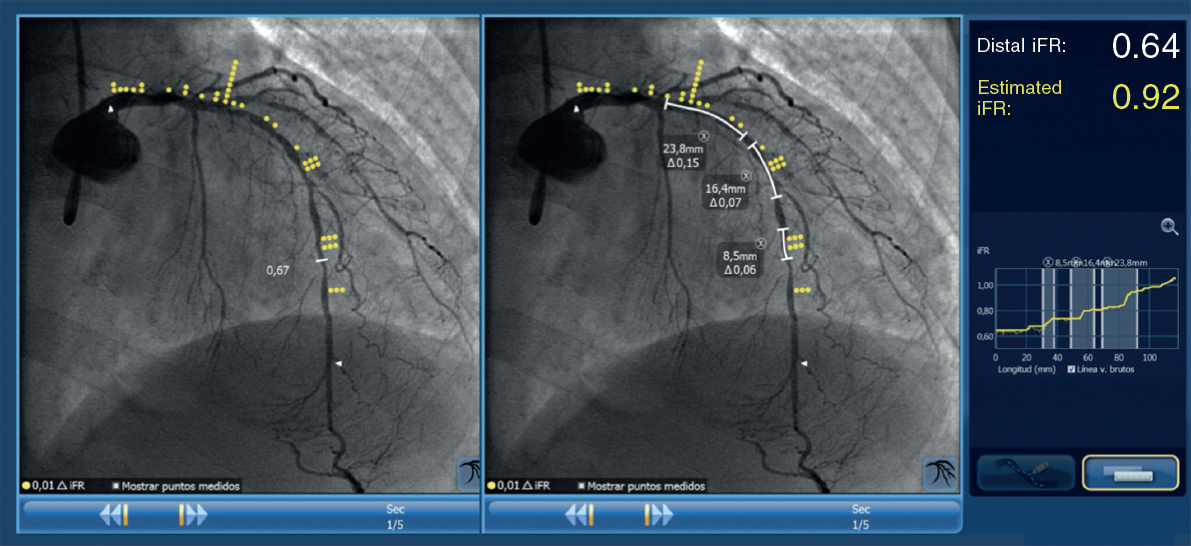

The Syncvision software for the iFR-pullback study was used in 155 lesions to guide the decision-making process (35.8%). Sequential and diffuse coronary lesions were the most common lesions analyzed by the iFR-pullback study (91 vessels, 58.7%, figure 2) followed by angiographically moderate lesions (52 vessels, 33.5%). This software was used in 5 bifurcation lesions (3.2%) to establish a baseline physiological classification or confirm an optimal physiological result after the PCI in both branches. The remaining lesions assessed by the iFR-pullback study were 6 focal or diffuse in-stent restenoses (3.9%) and 1 saphenous vein bypass graft with diffuse disease (0.6%).

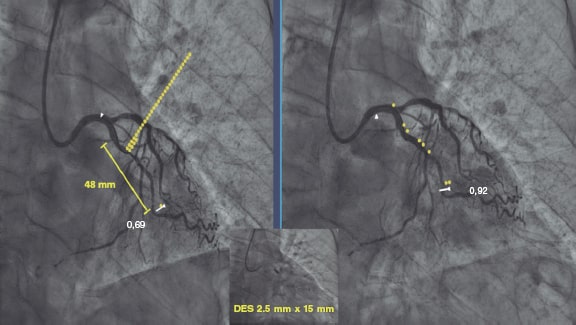

Figure 2. Images of iFR-coregistration with the Syncvision software from a left circumflex artery with diffuse disease in its middle segment (48 mm of lesion length). The baseline distal iFR was 0.69. The Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study demonstrated physiological significance only in the proximal segment. Direct implantation of a 2.5 mm × 15 mm DES was performed with a final iFR of 0.92. The stent length reduction regarding the angiographic lesion was 33 mm.

Follow-up

Follow-up data were available for 274 out of 277 patients (99%). After a mean 18 ± 10-month follow-up, 17 patients (6.1 %) presented with a major adverse cardiovascular events (table 3), 7 patients (2.5 %) with TLR, 2 of them over a lesion treated during the index procedure (0.7%) and 5 (1.8%) due to disease progression of a baseline physiologically negative lesion; 6 patients (2.2 %) suffered from acute myocardial infarction (1 patient due to acute stent thrombosis, another to a new lesion not evaluated at the index procedure, another to a baseline physiologically non-significant lesion, and the remaining 3 patients due to failed previously revascularized lesions); also, 4 patients (1.4%) presented with unclear or cardiac death. There were no differences regarding MACE between baseline physiologically negative and positive lesions (table 3).

Table 3. Rate of major adverse cardiovascular events at the follow-up based on the clinical presentation

| MACE (277 patients, 433 lesions) | iFR ≤ 0.89 (N = 167 lesions) | iFR > 0.89 (N = 266 lesions) | P | Stable angina (N = 160) | ACS (N = 117) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall, N (%) | 17 (6.1) | 7 (4.2) | 10 (3.8) | .9 | 7 (4.4) | 10 (8.5) | .1 |

| Unclear or cardiac death, N (%) | 4 (1.4) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) | .2 | 3 (1.9) | 1 (0.8) | .9 |

| Myocardial infarction, N (%) | 6 (2.2) | 1 (0.6) | 5 (1.9) | .46 | 1 (0.6) | 5 (4.3) | < .05 |

| Target lesion revascularization, N (%) | 7 (2.5) | 4 (2.4) | 3 (1.1) | .09 | 3 (1.9) | 4 (3.4) | .2 |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; iFR, instantaneous wave-free ratio; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events. Data are expressed as number (N) and percentage (%). |

|||||||

Based on their clinical signs, patients who presented with ACS had an increased rate of new myocardial infarction at the follow-up (5.3% vs 0.6%; P < .05), although no differences were found regarding unclear or cardiac death (0.9% vs 1.8%; P = .9) and the overall MACE (8.5% vs 4.4%; OR, 2.056, 0.759-5.572; P = .156 (table 3).

Finally, we performed a univariate analysis and found no risk or protective factors for MACE in this cohort of patients (table 4).

Table 4. Univariate analysis of the different variables with potential impact in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events between groups

| Variable | Univariate analysis | |

|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | P | |

| Age | 1.01 (0.97-1.06) | .608 |

| Male | 2.54 (0.57-11.40) | .224 |

| Current smoker | 1.23 (0.42-3.60) | .713 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.39 (0.50-3.87) | .531 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 0.99 (0.95-1.04) | .684 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 2.06 (0.76-5.57) | .156 |

| Multivessel disease | 0.90 (0.33-2.45) | .842 |

| Clopidogrel | 0.75 (0.23-2.44) | .623 |

| Ticagrelor | 1.52 (0.46-4.96) | .490 |

| Right coronary artery as examined vessel | 1.52 (0.54-4.26) | .428 |

| Other vessel analyzed | 1.26 (0.27-5.82) | .769 |

| Baseline iFR ≤ 0.89 | 1.43 (0.88-2.32) | .152 |

|

95%CI, confidence interval; iFR, instantaneous wave-free ratio; OR, odds ratio. |

||

DISCUSSION

This study tried to describe our experience using the physiological assessment and the Syncvision software in all-comer patients who underwent percutaneous coronary evaluations. The main findings of our study are: a) the use of the iFR in lesions of all-comer patients with the same cut-off values than established in the main trials showed a low percentage of MACE at the mid-term follow-up (6.1%); b) patients who presented with acute coronary syndrome showed an increased rate of myocardial infarction at the mid-term follow-up, and a trend towards a higher rate of MACE (OR, 2.056, 0.759-5.572; P = .156); c) The Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study provided additional information to guide the PCI decision-making process, especially in complex lesions like sequential lesions and diffuse coronary artery disease.

The fractional flow reserve was the first physiological index that demonstrated its utility, safety, and efficacy guiding the revascularization decision-making process.2,5-7 To obtain it, the use of a hyperemic agent to reduce vascular resistance is mandatory. Adenosine is the most commonly used drug, but it presents a series of side effects and contraindications.3,4,11,12 The more recent resting index (the instantaneous wave-free ratio) has demonstrated similar utility, safety, and efficacy to the FFR.3,4 Furthermore, it has 2 main advantages: first, it is not necessary to use vasodilators, thus reducing side effects, contraindications for use, and procedural time; secondly, it allows us to assess the contribution of each lesion when the vessel presents several lesions, with the specific Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study.8,9

For these reasons, the coronary physiology assessment is already the routine practice at the cath lab for the assessment of intermediate lesions,2-5 and multivessel disease.6,7 The main clinical setting included in these studies was stable angina. Patients with NSTEMI could be included if the lesion evaluated was identified as a non-culprit lesion. However, patients with STEMI, left main coronary artery lesions, and coronary artery bypass grafting lesions were not represented in the trials; also, the percentage of bifurcation lesions and sequential or diffuse coronary lesions is tiny. The cut-off value for the FFR and the iFR is well defined in those trials, being safe to postpone a lesion with a FFR > 0.80 or an iFR > 0.89. However, information is scarce on the utility and efficacy of physiological assessment and the same cut-off values in other types of lesions and clinical presentations.13 A multicenter registry that used the iFR to guide revascularization in patients with left main coronary artery stenosis has just been published. Using a cut-off value of 0.89, the authors conclude that postponing a left main coronary artery lesion with a iFR > 0.89 seems to be safe.10

Our study results suggest that the use of physiological assessment and the Syncvision software to guide the PCI decision-making process in all-comer patients with the same cut-off values as established by the landmark trials seems useful and safe regardless of the lesion and clinical presentation undergoing evaluation. Also, the MACE rates are similar to those reported by the landmark trials with selected lesions and patients.3,4 The iFR was the index used more often. The reasons are the faster and more comfortable use,3,4 and the possibility of lesion assessment with the Syncvision software.8,9

An important point of the study was to evaluate the rate of MACE based on the clinical presentation. Although no significant differences in the overall rate of MACE were found, patients who presented with acute coronary syndrome showed a significantly higher rate of MI at the follow-up, and a trend towards a higher rate of overall MACE. We think that this absence of statistical significance could be associated with a lack of statistical power.

A type of lesion included in the study was bifurcation lesions. Physiological assessment was used mainly to guide the side branch results during a provisional stenting strategy, thus keeping the pressure wire jailed as previously described.14,15 However, another interesting use of the iFR-pullback study with the Syncvision software was to stablish the baseline physiological contribution of every segment included in the most accepted classification.16

Finally, the Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study was used in 155 lesions (36%). The main type of lesions where this software was used were diffuse and tandem lesions. This software can predict the physiological contribution of each lesion or coronary segment, which is why we believe that it is a very useful tool to avoid treating lesions without any physiological contribution and probably without clinical benefits. That is why this software seems to reduce the total stent length implanted regarding angiographically-guided revascularization with potential benefits at long-term follow-up.17,18 A clinical trial is currently in the recruitment phase to demonstrate the efficacy of this software reducing the length of the stent implanted in this type of lesions without detriment to the adverse events.19

In our experience, the key aspects to properly perform this technique are: a) a perfect aortic pressure curve allows the accurate detection of diastole through the software; b) passing the pressure sensor as distally as possible; c) finding a projection where the artery can be seen completely and with the least foreshortening possible; d) withdrawing the pressure guidewire very slowly so that the software can perfectly recognize the length of each arterial segment; e) checking that there is not drift when the pressure guidewire reaches the coronary ostium (iFR different to 1 ± 0.02) to avoid erroneous results; f) performing the coronary angiography in the same position as the guidewire withdrawal without any modifications to the height of the table or the C-arm, and with a higher flow and volume of contrast to facilitate the software recognition of all the lesions. The main problem when using this technique is the presence of lesions with complicated wiring. The pressure wire has a hydrophilic non-polymeric coating that is useful in most lesions. However, it may be very challenging to reach the distal part of the artery in very complex lesions (calcified, angled lesions…), and our experience with previous normalization, wire disconnection, the microcatheter exchange technique, and reconnection is very limited, but still there is a significant level of drift.

Limitations

The study presents several limitations. It is a retrospective, single-center analysis with a low number of patients and lesions. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, although it could be a hypothesis-generating study for future larger scale randomized clinical trials.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of coronary physiology assessment using the iFR and the Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study in the routine daily practice and in all-comer patients seems safe with a low percentage of MACE at the mid-term follow-up. The Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study provides additional information to guide the PCI decision-making process.

FUNDING

The study has not had funding.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

F.J. Hidalgo-Lesmes prepared the main draft of the manuscript. S. Ojeda-Pineda participated in the drafting of the manuscript. C. Pericet-Rodríguez, R. González-Manzanares, A. Fernández-Ruiz, and M.G. Flores-Vergara all contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. A. Luque-Moreno, J. Suárez de Lezo, and F. Mazuelos-Bellido participated in the conception and design of the study. M.A. Romero-Moreno, and J.M. Segura Saint-Gerons revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. M. Pan Álvarez-Ossorio approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

F.J. Hidalgo-Lesmes received minor fees from Philips Volcano Europe unrelated to the manuscript; S. Ojeda-Pineda received minor fees from Terumo and Philips Volcano Europe unrelated to the manuscript; M. Pan Álvarez-Ossorio received minor fees from Terumo, Abbott Vascular, and Philips Volcano Europe unrelated to the manuscript. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Physiological assessments with the iFR are strongly recommended by the European guidelines on coronary revascularization to guide the PCI decision-making process in intermediate coronary stenosis.

- However, the evidence supporting the use of coronary physiology assessment, and the new Syncvision-iFR software in other type of lesions and clinical settings is scarce.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study describes our experience with the iFR and the Syncvision-iFR software in all-comer patients and demonstrates an acceptable percentage of MACE at the mid-term follow-up.

- Furthermore, the study shows that the Syncvision-guided iFR-pullback study provides additional information to guide the PCI decision-making process, particularly in complex lesions like sequential lesions and diffuse coronary artery disease.

REFERENCES

1. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

2. Pijls NHJ, van Schaardenburgh P, Manoharan G, et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Functionally Nonsignificant Stenosis. 5-Year Follow-Up of the DEFER Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2105-2111.

3. Davies JE, Sen S, Dehbi H-M, et al. Use of the Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio or Fractional Flow Reserve in PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1824-1834.

4. Götberg M, Christiansen EH, Gudmundsdottir IJ, et al. Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio versus Fractional Flow Reserve to Guide PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1813-1823.

5. Pijls NHJ, de Bruyne B, Peels K, et al. Measurement of Fractional Flow Reserve to Assess the Functional Severity of Coronary-Artery Stenoses. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1703-1708.

6. Tonino AL, Bruyne B De, Pijls NHJ, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Guiding Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Pim. N Engl J Med. 2015:687-696.

7. Van Nunen LX, Zimmermann FM, Tonino PAL, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guidance of PCI in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (FAME):5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1853-1860.

8. Nijjer SS, Sen S, Petraco R, Mayet J, Francis DP, Davies JER. The Instantaneous wave-Free Ratio (iFR) pullback:A novel innovation using baseline physiology to optimise coronary angioplasty in tandem lesions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:167-171.

9. Nijjer SS, Sen S, Petraco R, et al. Pre-angioplasty instantaneous wave-free ratio pullback provides virtual intervention and predicts hemodynamic outcome for serial lesions and diffuse coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1386-1396.

10. Warisawa T, Cook CM, Rajkumar C, et al. Safety of Revascularization Deferral of Left Main Stenosis Based on Instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio Evaluation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1655-1664.

11. Gili S, Barbero U, Errigo D, et al. Intracoronary versus intravenous adenosine to assess fractional flow reserve:A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Med. 2018;19:274-283.

12. Patel HR, Shah P, Bajaj S, Virk H, Bikkina M, Shamoon F. Intracoronary adenosine-induced ventricular arrhythmias during fractional flow reserve (FFR) measurement:case series and literature review. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2017;32:374-380.

13. Ihdayhid AR, Koh JS, Ramzy J, et al. The Role of Fractional Flow Reserve and Instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio Measurements in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21.

14. Burzotta F, Lassen JF, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in left main coronary artery disease:The 13th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:112-120.

15. Hidalgo F, Pan M, Ojeda S, et al. Feasibility and Efficacy of the Jailed Pressure Wire Technique for Coronary Bifurcation Lesions. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:109-111.

16. Medina A, Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M. A New Classification of Coronary Bifurcation Lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59:183.

17. Mauri L, O'Malley AJ, Popma JJ, et al. Comparison of thrombosis and restenosis risk from stent length of sirolimus-eluting stents versus bare metal stents. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1140-1145.

18. Kikuta Y, Cook CM, Sharp ASP, et al. Pre-Angioplasty Instantaneous Wave-Free Ratio Pullback Predicts Hemodynamic Outcome In Humans With Coronary Artery Disease:Primary Results of the International Multicenter iFR GRADIENT Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:757-767.

19. Hidalgo F, Ojeda S, de Lezo JS, et al. Usefulness of a co-registration strategy with iFR in long and/or diffuse coronary lesions (iLARDI):study protocol. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:190-195.

Abstract

Introduction and objectives: Patients with a low post-percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) fractional flow reserve (FFR) are at a higher risk for future adverse cardiac events. The objective of the current study was to assess specific patient and procedural predictors of post-PCI FFR.

Methods: The FFR-SEARCH study is a prospective single-center registry of 1000 consecutive all-comer patients who underwent FFR measurements after an angiographically successful PCI with a dedicated microcatheter. Mixed effects models were used to search for independent predictors of post-PCI FFR.

Results: The mean post-PCI distal coronary pressure divided by the aortic pressure (Pd/Pa) was 0.96 ± 0.04 and the mean post-PCI FFR, 0.91 ± 0.07. After adjusting for the independent predictors of post-PCI FFR, the left anterior descending coronary artery as the measured vessel was the strongest predictor of post-PCI FFR (adjusted β = -0.063; 95%CI, -0.070 to -0.056; P < .0001) followed by the postprocedural minimum lumen diameter (adjusted β = 0.039; 95%CI, 0.015-0.065; P = .002). Additionally, male sex, in-stent restenosis, chronic total coronary occlusions, and pre- and post-dilatation were negatively associated with postprocedural FFR. Conversely, type A lesions, thrombus-containing lesions, postprocedural percent stenosis, and stent diameter were positively associated with postprocedural FFR. The R2 for the complete model was 53%.

Conclusions: Multiple independent patient and vessel related predictors of postprocedural FFR were identified, including sex, the left anterior descending coronary artery as the measured vessel, and postprocedural minimum lumen diameter.

Keywords: Percutaneous coronary intervention. Post-PCI FFR. Predictors.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Los pacientes con una reserva fraccional de flujo (FFR) posintervención coronaria percutánea (ICP) baja tienen mayor riesgo de futuros eventos cardiacos adversos. El objetivo del presente estudio fue evaluar predictores específicos de pacientes y procedimientos de FFR tras una ICP.

Métodos: El estudio FFR-SEARCH es un registro prospectivo de un solo centro que incluyó 1.000 pacientes consecutivos que se sometieron a una evaluación de la FFR tras una ICP con éxito angiográfico utilizando un microcatéter específico. Se utilizaron modelos de efectos mixtos para buscar predictores independientes de FFR tras la ICP.

Resultados: La media de presión distal dividida entre la presión aórtica tras la ICP fue de 0,96 ± 0,04, y la media de la FFR tras la ICP fue de 0,91 ± 0,07. Tras ajustar por predictores independientes de FFR tras la ICP, la arteria descendente anterior izquierda como vaso medido fue el predictor más fuerte (β ajustado = −0,063; IC95%, −0,070 a −0,056; p < 0,0001), seguida del diámetro luminal mínimo posprocedimiento (β ajustado = 0,039; IC95%, 0,015 a 0,065; p = 0,002). Además, el sexo masculino, la reestenosis del stent, las oclusiones totales crónicas y la pre- y posdilatación se correlacionaron negativamente con la FFR posprocedimiento. Por el contrario, las lesiones de tipo A, las lesiones con trombos, el porcentaje de estenosis posprocedimiento y el diámetro del stent se correlacionaron positivamente con la FFR posprocedimiento. El R2 para el modelo completo fue del 53%.

Conclusiones: Se identificaron diversos predictores independientes relacionados con los pacientes y con los vasos para la FFR posprocedimiento, incluyendo el sexo, la arteria descendente anterior izquierda como vaso medido y el diámetro luminal mínimo posprocedimiento.

Palabras clave: Intervención coronaria percutánea. FFR post-ICP. Predictores.

Abbreviations:

FFR: fractional flow reserve. LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery. MLD: minimum luminal diameter. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

The limitations of an accurate assessment of the hemodynamic significance of coronary artery lesions through angiographic guidance alone are well-known.1 Instead, the fractional flow reserve (FFR) has proven to be a useful technique to address the coronary physiology and the hemodynamic significance of coronary segments before and after performing an intervention.2-4 Also, measuring FFR post-stenting has proven to be a strong and independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events at the 2-year follow-up.3-5

While FFR primarily takes into account the relative luminal narrowing and the amount of viable myocardium perfused by a specific vessel, several factors have been shown to impact the FFR values prior to performing a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Therefore, longer lesion length, high syntax scores, calcifications, and tortuosity are associated with significantly lower FFR values. Conversely, the presence of microvascular dysfunction, chronic kidney disease and female gender have been associated with higher FFR values.6-11

At the present time, there is lack of data on independent predictors of post-PCI FFR. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to assess the patient and procedural characteristics associated with low post-PCI FFR in an all-comer patient population.

METHODS

The FFR-SEARCH study is a prospective single-center registry that assessed the routine distal pressure divided by the aortic pressure (Pd/Pa) and FFR values of all consecutive patients after an angiographically successful PCI. The primary endpoint was to study the impact of post-PCI FFR on the rate of major adverse cardiovascular event at the 2-year follow-up. Accordingly, no further actions were taken to improve post-PCI FFR. The study was performed in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients gave their written informed consent to undergo the procedure. Also, anonymous datasets for research purposes were used in compliance with the Dutch Medical Research Act. A total of 1512 patients treated between March 2016 and May 2017 at the Erasmus Medical Center were eligible to enter our study. A total of 504 of these patients were excluded due to hemodynamic instability (156), a rather small distal outflow (129), the operator’s decision not to proceed with post-PCI hemodynamic assessment (148) or other reasons (79). A total of 1000 patients were included in the study. The microcatheter could not cross the treated lesion in 28 patients, technical issues with the catheter prevented post-PCI assessments in 11 patients, and in 2 patients the post-PCI FFR measurements had to be aborted prematurely due to adenosine intolerance. This left 959 patients whose post-PCI FFR values were measured in at least 1 angiographically successfully treated lesion.

Quantitative coronary angiography

The preprocedural lesion type was defined according to the ACC/AHA guidelines12 and divided into 4 categories: A, B1, B2, and C. Comprehensive quantitative coronary angiography analyses were performed pre- and post-stent implantation in all the treated lesions. An angiographic view with minimal foreshortening of the lesion and minimal overlapping with other vessels was selected. Similar angiographic views were used pre- and post-stent implantation. Measurements included pre- and postprocedural percent diameter stenosis, reference vessel diameter, lesion length, and minimum luminal diameter (MLD). In case of a total occlusion in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or chronic total coronary occlusion (CTO), the MLD was considered zero and the percent diameter stenosis, 100%. The reference vessel diameter and the lesion length were measured from the first angiographic view with restored flow. All measurements were taken using CAAS for Windows, version 2.11.2 (Pie Medical Imaging, The Netherlands).

Fractional flow reserve measurements

All FFR measurements were acquired using the Navvus RXi system (ACIST Medical Systems, United States), a dedicated FFR microcatheter with optical pressure sensor technology.13,14 Measurements were performed after an intracoronary bolus of nitrates (200 µg). The catheter was advanced while mounted over the previously used guidewire approximately 20 mm distal to the most distal border of the stent. The FFR was defined as the mean distal coronary artery pressure divided by the mean aortic pressure during maximum hyperemia achieved by the continuous IV infusion of adenosine at a rate of 140 µg/kg/min via the antecubital vein. In this study no vessels were assessed using intracoronary adenosine.

Statistical analysis

At baseline, the categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentage) and the continuous ones as mean ± standard deviation. To assess the independent predictors of post-PCI FFR, all the patient and vessel characteristics were primarily assessed through an univariate test using a mixed effects model (LME-model) with a random effect for the patients and a fixed effect for the post-PCI FFR. All variables were subsequently inserted in a multivariate LME-model using the enter method that resulted in all the significant independent predictors of post-PCI FFR values. A forest plot was developed to depict all variables with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Beta (β) values show the average increase or decrease of the FFR values in the case of dichotomous variables or the increment per unit increase in the case of continuous variables. Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package R (version 3.5.1, packages: Hmisc, lme4 and nlme, RStudio Team, United States).

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

The mean age was 64.6 ± 11.8 years and 72.5% were males. In 959 patients, at least, 1 lesion was measured with an overall 1165 successfully treated and measured lesions. The patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown on table 1. Up to 70% of the patients presented with an acute coronary syndrome, and 18% had confirmed thrombus as seen on the angiography. Intravascular imaging modalities were used in 9.6% of the patients to guide the procedure. Overall, 1.4 ± 0.6 lesions were treated per patient and in 1.2 ± 0.5 lesions per patient the post-PCI FFR was successfully assessed. The average overall stent length per vessel was 29 mm ± 17 mm with an average stent diameter of 3.2 mm ± 0.5 mm.

Table 1. Baseline patient and vessel characteristics

| Variable | Total FFR-SEARCH registry |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | (N = 1000) |

| Age | 64.6 ± 11.8 |

| Sex, male | 725 (73) |

| Hypertension | 515 (52) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 451 (45) |

| Diabetes | 191 (19) |

| Smoking history | 499 (50) |

| Previous stroke | 77 (8) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 76 (8) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 203 (20) |

| Previous PCI | 264 (26) |

| Previous CABG | 57 (6) |

| Indication for PCI | |

| Stable angina | 304 (30) |

| NSTEMI | 367 (37) |

| STEMI | 329 (33) |

| Vessel characteristics | (N = 1165) |

| Lesion type | |

| A | 125 (11) |

| B1 | 233 (20) |

| B2 | 379 (33) |

| C | 428 (37) |

| LAD | 593 (51) |

| Bifurcation | 138 (12) |

| Calcified | 402 (35) |

| In-stent restenosis | 39 (3) |

| Thrombus | 214 (18) |

| Stent thrombosis | 14 (1) |

| Ostial | 97 (8) |

| CTO | 42 (4) |

| Stenosis pre procedural | 69 ± 22 |

| Reference diameter pre procedural (mm) | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

| Length pre procedural (cm) | 21 ± 11 |

| MLD pre (mm) | 0.9 ± 0.6 |

| Predilatation | 769 (66) |

| Postdilatation | 691 (59) |

| Stenosis post procedural | 44 ± 13 |

| Reference diameter post procedural (mm) | 2.7 ± 0.5 |

| Length post procedural (cm) | 24 ± 13 |

| MLD post procedural (mm) | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

| Number of stents | 1.4 ± 0.6 |

| Stent length (cm) | 29 ± 17 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | 3.2 ± 0.5 |

| Mean post-PCI Pd/Pa | 0.96 ± 0.04 |

| Mean post-PCI FFR | 0.91 ± 0.07 |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; FFR, fractional flow reserve; LAD, left anterior descending artery; MLD, minimum luminal diameter; NSTEMI, non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; Pd/Pa, ratio of mean distal coronary artery pressure to mean aortic pressure; Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or no. (%). |

|

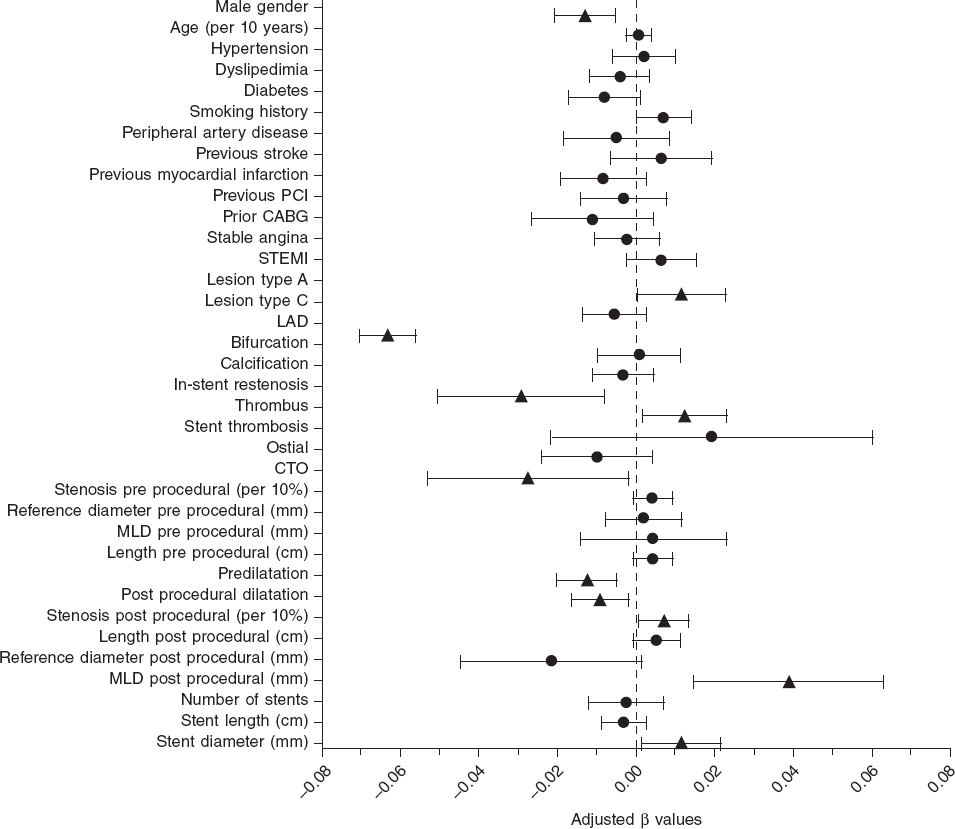

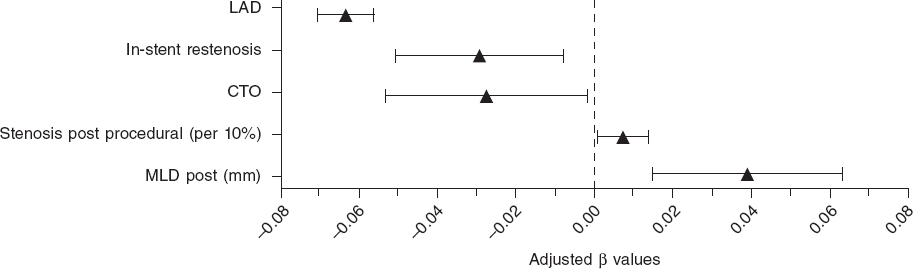

The mean post-PCI FFR was 0.91 ± 0.07 and 7.7% of vessels had a post-PCI FFR ≤ 0.80. In the LME-model and after adjusting for independent predictors of post-PCI FFR, the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as the measured vessel was the strongest predictor of post-PCI FFR (adjusted β = -0.063; 95%CI, -0.070 to -0.056; P < .0001) followed by the postprocedural MLD (adjusted β = 0.039; 95%CI, 0.015-0.065]; P = .002). Additionally, male sex, in-stent restenosis, CTO, and pre- and post-dilatation were negatively correlated with postprocedural FFR. Conversely, type A lesions, thrombus-containing lesions, postprocedural percent diameter stenosis, and stent diameter were positively correlated with postprocedural FFR. The R2 for the entire model was 53%. Figure 1 shows all significant and non-significant adjusted predictors included in the LME-model. Table 2 shows all adjusted and unadjusted predictors with corresponding β values and 95%CI. The most important predictors are shown on figure 2.

Figure 1. Forest plot of independent predictors of post-PCI FFR. Adjusted beta values with 95% confidence intervals. Triangles indicate significant predictors while circles are indicative of non-significant predictors in the multivariate generalized mixed model to predict post-PCI FFR. ACS, acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; MLD, minimum lumen diameter.

Table 2. Predictors for post-PCI FFR

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | β(95%CI) | P | β(95%CI) | |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Male sex | .214 | -0.006 (-0.015 – 0.003) | .001 | -0.013 (-0.021 – -0.005) |

| Age (per 10 years) | .976 | 0.000 (-0.03 – 0.03) | .724 | 0.001 (-0.002 – 0.003) |

| Hypertension | .013 | -0.010 (-0.018 – -0.002) | .610 | 0.002 (-0.006 – 0.010) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | < .001 | -0.019 (-0.027 – -0.011) | .287 | -0.004 (-0.012 – 0.004) |

| Diabetes | < .001 | 0.018 (0.008 – 0.042) | .081 | -0.008 (-0.017 – 0.001) |

| Smoking history | .007 | 0.020 (0.010 – 0.019) | .054 | 0.007 (-0.0001 – 0.014) |

| Previous stroke | .831 | -0.002 (-0.017 – 0.013) | .342 | 0.006 (-0.0007 – 0.019) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | .022 | -0.017 (-0.032 – -0.003) | .460 | -0.005 (-0.018 – 0.008) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | .002 | -0.016 (-0.026 – -0.006) | .137 | -0.008 (-0.019 – 0.003) |

| Previous PCI | < .001 | -0.016 (-0.025 – -0.007) | .569 | -0.032 (-0.014 – 0.008) |

| Previous CABG | .896 | -0.001 (-0.019 – 0.017) | .166 | -0.011 (-0.014 – 0.004) |

| Indication for PCI | ||||

| Stable angina | < .001 | -0.025 (-0.034 – -0.016) | .563 | -0.002 (-0.011 – 0.005) |

| STEMI | < .001 | 0.032 (0.025 – 0.041) | .171 | 0.006 (-0.003 – 0.015) |

| Vessel characteristics | ||||

| Lesion type | ||||

| A | <.001 | 0.022 (0.009 – 0.035) | .040 | 0.012 (0.0005 – 0.023) |

| C | .045 | -0.008 (-0.016 – -0.0002) | .172 | -0.006 (-0.014 – 0.002) |

| LAD | <.001 | -0.070 ( -0.077 – -0.064) | <.001 | -0.063 (-0.070 – -0.056) |

| Bifurcation | < .001 | -0.024 (-0.036 – - 0.012) | .883 | 0.001 (-0.010 – 0.011) |

| Calcified | < .001 | -0.025 (-0.033 – -0.017) | .409 | -0.003 (-0.011 – 0.005) |

| In-stent restenosis | .006 | -0.031 (-0.053 – -0.009) | .007 | -0.029 (-0.051 – -0.008) |

| Thrombus | < .001 | 0.031 (0.021 – 0.042) | .026 | 0.012 (-0.001 – 0.023) |

| Stent thrombosis | .920 | 0.002 (-0.034 – 0.038) | .362 | 0.019 (-0.022 – 0.060) |

| Ostial | .181 | -0.010 (-0.024 – 0.005) | .165 | -0.010 (-0.024 – 0.004) |

| CTO | .002 | -0.034 (-0.056 – -0.013) | .036 | -0.027 (-0.053 – -0.002) |

| Stenosis pre procedural (per 10%) | <.001 | 0.007 (0.005 – 0.009) | .105 | 0.004 (-0.0009 – 0.009) |

| Reference diameter pre procedural (mm) | <.001 | 0.030 (0.023 – 0.037) | .704 | 0.002 (-0.008 – 0.011) |

| Length pre procedural (cm) | .900 | -0.00002 (-0.004 – 0.003) | .101 | 0.004 (0.0008 – 0.009) |

| MLD pre procedural (mm) | <.001 | -0.015 (-0.022 – -0.008) | .638 | 0.004 (-0.014 – 0.023) |

| Predilatation | <.001 | -0.019 (-.027 – -0.011) | .002 | -0.012 (-0.020 – -0.005) |

| Postdilatation | <.001 | 0.027 (-0.035 – -0.019) | .015 | -0.009 (-0.016 – -0.002) |

| Stenosis post procedural (per 10%) | .077 | 0.003 (-0.0003 – 0.006) | .029 | 0.01 (0.0007 – 0.01) |

| Reference diameter post procedural (mm) | <.001 | 0.035 (0.027 – 0.042) | .067 | -0.022 (-0.045 – 0.002) |

| Length post procedural (cm) | .312 | -0.002 (-0.005 – 0.001) | .086 | 0.001 (-0.0007 – 0.001) |

| MLD post procedural (mm) | <.001 | 0.032 (0.024 – 0.040) | .002 | 0.039 (0.015 – 0.063) |

| Number of stents | <.001 | -0.012 (-0.018 – -0.006) | .620 | -0.002 (-0.012 – 0.007) |

| Stent length (cm) | <.001 | 0.019 (0.009 – 0.041) | .286 | -0.003 (-0.009 – 0.002) |

| Stent diameter (mm) | <.001 | 0.033 (0.025 – 0.042) | .026 | 0.012 (0.001 – 0.022) |

|

Beta (β) values are indicative of the average increase or decrease of the FFR values in cases of dichotomous variables or the increment per unit increase in cases of continuous variables. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; FFR, fractional flow reserve; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; MLD, minimum lumen diameter; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

||||

Figure 2. Forest plot of most important predictors of post-PCI FFR. Adjusted beta values with 95% confidence intervals. The figure includes all significant predictors from the multivariate generalized mixed model predicting post-PCI FFR except for categorical variables with beta values < 0.02. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; MLD, minimum lumen diameter.

DISCUSSION

This study is the largest report to this day of predictors of post-PCI FFR. Based on data derived from the FFR-SEARCH registry, we could identify several patient and procedural predictors of post-PCI FFR. These predictors will bring more in-depth interpretations of post-PCI FFR values to be able to identify correctly which vessels are prone to future events. At first, male gender appeared to be negatively correlated with postprocedural FFR. This finding is consistent with the findings of former studies that focused on the impact of gender on pre-PCI FFR measurements.6,11,15,16 Compared to females, males are known to have a lower prevalence of microvascular dysfunction.8,17 The concept of FFR is based on drug-induced maximal hyperemia to minimize microvascular resistance. Microvascular dysfunction may hamper this vasodilator response and consequently result in a dampened flow response and high FFR.15 Subsequently, on average, males have larger myocardial masses and myocardial perfusion territories compared to females.18,19 The importance of the latter is illustrated by the second and strongest predictor of post-PCI FFR in this study, the FFR measurements in the LAD. FFR values are associated with the myocardial mass and the outflow territory of the measured vessel. As such, the LAD—the vessel with the largest perfusion area—has previously been associated with lower pre- and postprocedural FFR values.20-22

The diameters of the stents implanted in the RCA are larger, on average, but the outflow territory of the LAD is even larger.23 This discrepancy between luminal dimensions and myocardial mass may explain why the optimal improvement of the FFR measurements in the LAD is difficult to achieve.23

Thirdly, larger stent diameters and larger post-PCI MLDs were associated with higher post-PCI FFR values. However, higher postprocedural percent stenosis was also associated with higher post-PCI FFR values. While these findings may seem contradictory, post procedural percent stenosis was not associated with post-PCI physiology in the DEFINE PCI study either.24

In the intravascular ultrasound substudy of the FFR-SEARCH registry, van Zandvoort et al. showed that evident signs of residual luminal narrowing including focal lesions, underexpansion, and malapposition were present in a significant amount of vessels with post-PCI FFR values ≤ 0.85. These findings were not readily apparent on the comprehensive quantitative coronary angiography.25 Percent diameter stenosis was 20% in the cohort of patients with post-PCI FFR values ≤ 0.85 and > 0.85.26

Together with the latter predictors of post-PCI FFR we identified several others. A dedicated analysis of 26 CTOs recently showed that postprocedural FFR values are typically low initially; however they seem to increase at the 4-month follow-up. The initially low post-PCI FFR values is thought to be due to the microvascular dysfunction of the recently opened vessel, a phenomenon that improves after several months.27 In-stent restenosis and pre- and postdilatation were associated with lower post-PCI FFR values. A finding that is consistent with former studies that showed that, in general, complex lesions are associated with lower post-PCI FFR values.20,21,26,28

Also, it was interesting to see the impact of clinical presentation on post-PCI FFR values in the study population in which most patients presented with acute coronary syndrome. Contrary to former studies that questioned the validity of invasive hyperemic physiological indices in patients with acute coronary syndrome, we could not confirm the impact of clinical presentation on post-PCI FFR values. However, the identification of a thrombus, that often occurs after a ruptured plaque in patients with acute coronary syndrome, was associated with significantly higher FFR values. Despite the restoration of epicardial flow by the PCI, a relatively large number of patients with STEMI have abnormal myocardial perfusion at the end of the procedure.29 This phenomenon is thought to be related to microvascular obstruction due to distal embolization (reperfusion injury) and tissue inflammation due to myocyte necrosis.30,31 The latter may explain the significantly higher post-PCI FFR values reported in patients presenting with thrombus-containing lesions compared to those without such lesions. Conversely, our findings also show that in patients without thrombus-containing lesions the post-PCI FFR may be a valuable diagnostic tool for the identification of patients at a high risk of future adverse cardiac events.

Limitations

This study was conducted with the Navvus microcatheter, a dedicated rapid exchange microcatheter with a mean diameter of 0.022 in that proved its utility in a slight but significant underestimation of the FFR compared to conventional 0.014 in pressure guidewires.32 That is why we cannot directly extrapolate the current findings to wire-based FFR devices.14 Based on the study protocol, no further action was taken in the presence of low post-PCI FFR values. The Target FFR and FFR REACT studies (NCT03259815 and NTR6711) will provide further information on post-PCI FFR and the potential of further actions to improve post-PCI FFR and clinical outcomes.33,34 These studies should also focus on the trade-off of potential benefits and harm when performing additional interventions in order to improve the final FFR values.

CONCLUSIONS

In this substudy of the FFR-SEARCH registry, the largest real-world post-PCI FFR registry conducted to this day, we identified sex, LAD vessels, postprocedural MLD, and several other independent predictors of postprocedural FFR.

FUNDING

The FFR SEARCH study was conducted with institutional support from ACIST Medical Inc.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Conception and design: L.J.C. van Zandvoort, N.M. van Mieghem, and J. Daemen. Data aquisition: L.J.C. van Zandvoort, K. Masdjedi, J. Wilschut, W. Den Dekker, R. Diletti, F. Zijlstra, N.M. van Mieghem, and J. Daemen. Statistical analysis and manuscript writing: L.J.C. van Zandvoort and J. Daemen. Providing criticial feedback to the manuscript and approving the final content: L.J.C. van Zandvoort, K. Masdjedi, T. Neleman, M.N Tovar Forero, J. Wilschut, W. Den Dekker, R. Diletti, F. Zijlstra, N.M. van Mieghem, and J. Daemen.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

L.J.C. van Zandvoort received institutional research support from Acist medical Inc. J. Daemen received institutional research support from Pie Medical, ACIST Medical Inc., PulseCath, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Pie Medical and speaker and consultancy fees from PulseCath, Medtronic, ReCor Medical, ACIST Medical Inc. and Pie Medical. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- FFR has proven to be a useful technique to address coronary physiology and the hemodynamic significance of coronary segments pre- and post-intervention.

- Also, the FFR post-stenting has proven to be a strong and independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events at the 2-year follow-up.

- Unfortunately, at present, there is lack of data on independent predictors of post PCI FFR.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study is the largest report to this day on predictors of post-PCI FFR.

- Based on data from the FFR-SEARCH registry, we could identify several patient and procedural predictors of post-PCI FFR.

- The main predictors included sex, LAD vessels, and postprocedural lumen dimensions. These predictors will help us interpret post-PCI FFR values and identify correctly the vessels that are prone to future events.

REFERENCES

1. Topol EJ, Nissen SE. Our preoccupation with coronary luminology. The dissociation between clinical and angiographic findings in ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1995;92:2333-2342.

2. De Bruyne B, Fearon WF, Pijls NHJ, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI for stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;1533-4406.

3. Wolfrum M, Fahrni G, de Maria GL, et al. Impact of impaired fractional flow reserve after coronary interventions on outcomes:a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:177.

4. Rimac G, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Clinical value of post-percutaneous coronary intervention fractional flow reserve value:A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2017;183:1-9.

5. Kasula S, Agarwal SK, Hacioglu Y, et al. Clinical and prognostic value of poststenting fractional flow reserve in acute coronary syndromes. Heart. 2016;102:1988-1994.

6. Sareen N, Baber U, Kezbor S, et al. Clinical and angiographic predictors of haemodynamically significant angiographic lesions:development and validation of a risk score to predict positive fractional flow reserve. EuroIntervention. 2017;12:e2228-e2235.

7. Baranauskas A, Peace A, Kibarskis A, et al. FFR result post PCI is suboptimal in long diffuse coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:1473-1480.

8. Crystal GJ, Klein LW. Fractional flow reserve:physiological basis, advantages and limitations, and potential gender differences. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11:209-219.

9. Ahmadi A, Leipsic J, Ovrehus KA, et al. Lesion-Specific and Vessel-Related Determinants of Fractional Flow Reserve Beyond Coronary Artery Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:521-530.

10. Tebaldi M, Biscaglia S, Fineschi M, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve Evaluation and Chronic Kidney Disease:Analysis From a Multicenter Italian Registry (the FREAK Study). Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:555-562.

11. Fineschi M, Guerrieri G, Orphal D, et al. The impact of gender on fractional flow reserve measurements. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:360-366.

12. Ryan TJ, Faxon DP, Gunnar RM, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Assessment of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Cardiovascular Procedures (Subcommittee on Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty). Circulation. 1988;78:486-502.

13. Diletti R, Van Mieghem NM, Valgimigli M, et al. Rapid exchange ultra-thin microcatheter using fibre-optic sensing technology for measurement of intracoronary fractional flow reserve. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:428-432.

14. Menon M, Jaffe W, Watson T, Webster M. Assessment of coronary fractional flow reserve using a monorail pressure catheter:the first-in-human ACCESS-NZ trial. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:257-263.

15. van de Hoef TP, Meuwissen M, Escaned J, et al. Fractional flow reserve as a surrogate for inducible myocardial ischaemia. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:439-452.

16. Kim HS, Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, et al. The impact of sex differences on fractional flow reserve-guided percutaneous coronary intervention:a FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation) substudy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1037-1042.

17. Reis SE, Holubkov R, Lee JS, et al. Coronary flow velocity response to adenosine characterizes coronary microvascular function in women with chest pain and no obstructive coronary disease. Results from the pilot phase of the Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1469-1475.

18. Iqbal MB, Shah N, Khan M, Wallis W. Reduction in myocardial perfusion territory and its effect on the physiological severity of a coronary stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:89-90.

19. Lin FY, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, et al. Cardiac chamber volumes, function, and mass as determined by 64-multidetector row computed tomography:mean values among healthy adults free of hypertension and obesity. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1:782-786.

20. Nam CW, Hur SH, Cho YK, et al. Relation of fractional flow reserve after drug-eluting stent implantation to one-year outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1763-1767.

21. Doh JH, Nam CW, Koo BK, et al. Clinical Relevance of Poststent Fractional Flow Reserve After Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation. J Invasive Cardiol. 2015;27:346-351.

22. Agarwal SK, Kasula S, Hacioglu Y, Ahmed Z, Uretsky BF, Hakeem A. Utilizing Post-Intervention Fractional Flow Reserve to Optimize Acute Results and the Relationship to Long-Term Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:1022-1031.

23. Kimura Y, Tanaka N, Okura H, et al. Characterization of real-world patients with low fractional flow reserve immediately after drug-eluting stents implantation. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2016;31:29-37.

24. Jeremias A, Davies JE, Maehara A, et al. Blinded Physiological Assessment of Residual Ischemia After Successful Angiographic Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:The DEFINE PCI Study. JACC:Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1991-2001.

25. van Zandvoort LJC, Masdjedi K, Witberg K, et al. Explanation of Postprocedural Fractional Flow Reserve Below 0.85. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e007030.

26. van Zandvoort LJC, Witberg K, Ligthart J, et al. Explanation of post procedural fractional flow reserve below 0.85:a comprehensive ultrasound analysis of the FFR Search registry. In Cardiovascular Research Technologies (CRT) Conference 2018 March 3-6;Washingtong DC, United States. 2018.

27. Karamasis GV, Kalogeropoulos AS, Mohdnazri SR, et al. Serial Fractional Flow Reserve Measurements Post Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e006941.

28. Pijls NH, Klauss V, Siebert U, et al. Coronary pressure measurement after stenting predicts adverse events at follow-up:a multicenter registry. Circulation. 2002;105:2950-2954.

29. Stone GW, Webb J, Cox DA, et al. Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1063-1072.

30. Shah NR, Al-Lamee R, Davies J. Fractional flow reserve in acute coronary syndromes:A review. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2014;5:20-25.

31. Cuculi F, De Maria GL, Meier P, et al. Impact of microvascular obstruction on the assessment of coronary flow reserve, index of microcirculatory resistance, and fractional flow reserve after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1894-904.

32. Pouillot C, Fournier S, Glasenapp J, et al. Pressure wire versus microcatheter for FFR measurement:a head-to-head comparison. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:e1850-e1856.

33. van Zandvoort LJC, Masdjedi K, Tovar Forero MN, et al. Fractional flow reserve guided percutaneous coronary intervention optimization directed by high-definition intravascular ultrasound versus standard of care:Rationale and study design of the prospective randomized FFR-REACT trial. Am Heart J. 2019;213:66-72.

34. Collison D, McClure JD, Berry C, Oldroyd KG. A randomized controlled trial of a physiology-guided percutaneous coronary intervention optimization strategy:Rationale and design of the TARGET FFR study. Clin Cardiol. 2020;43:414-422.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The presence of comorbidities in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome worsens its prognosis. The objective of the study was to analyze the impact of the burden of comorbidities in the decision of using invasive management in these patients.

Methods: A total of 7211 patients > 70 years old from 11 Spanish registries were included. Individual data were analyzed in a common database. We assessed the presence of 6 comorbidities and their association with coronary angiography during admission.

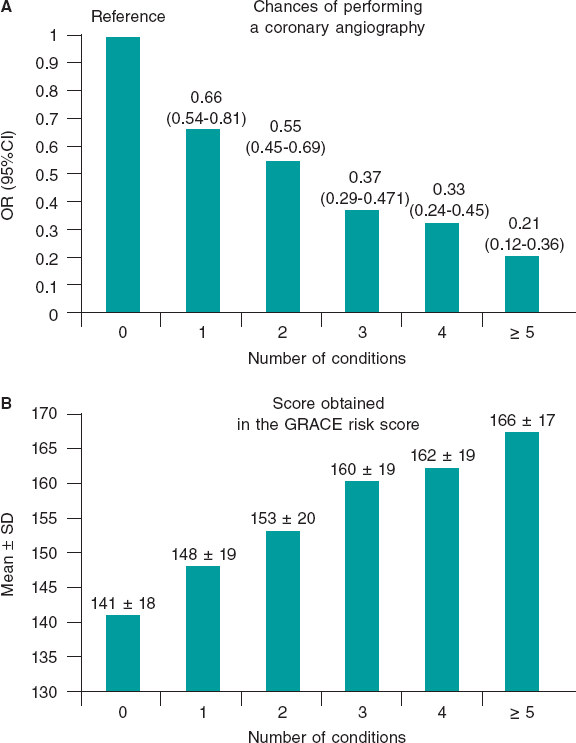

Results: The mean age was 79 ± 6 years and the mean CRACE score was 150 ± 21 points. A total of 1179 patients (16%) were treated conservatively. The presence of each comorbidity was associated with less invasive management (adjusted for predictive clinical variables): cerebrovascular disease (OR, 0.78; 95%CI, 0.64-0.95; P = .01), anemia (OR, 0.64; 95%CI, 0.54-0.76; P < .0001), chronic kidney disease (OR, 0.65; 95%CI, 0.56-0.75; P < .0001), peripheral arterial disease (OR, 0.79; 95%CI, 0.65-0.96; P = .02), chronic lung disease (OR, 0.85; IC95%, 0.71-0.99; P = .05), and diabetes mellitus (OR, 0.85; 95%CI, 0.74-0.98; P < .03). The increase in the number of comorbidities (comorbidity burden) was associated with a reduction in coronary angiographies after adjusting for the GRACE score: 1 comorbidity (OR, 0.66; 95%CI, 0.54-0.81), 2 comorbidities (OR, 0.55; 95%CI, 0.45-0.69), 3 comorbidities (OR, 0.37; 95%CI, 0.29-0.47), 4 comorbidities (OR, 0.33; 95%CI, 0.24-0.45), ≥ 5 comorbidities (OR, 0.21; 95%CI, 0.12-0.36); all P values < .0001 compared to 0.

Conclusions: The number of coronary angiographies performed drops as the number of comorbidities increases in elderly patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. More studies are still needed to know what the best management of these patients should be.

Keywords: Comorbidities. Elderly. Acute coronary syndrome. Coronary angiography.

Resumen

Introducción y objetivos: La comorbilidad en ancianos con síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST empeora el pronóstico. El objetivo fue analizar la influencia de la carga de comorbilidad en la decisión del tratamiento invasivo en ancianos con SCASEST.

Métodos: Se incluyeron 7.211 pacientes mayores de 70 años procedentes de 11 registros españoles. Los datos se analizaron en una base de datos conjunta. Se evaluó la presencia de 6 enfermedades simultáneas y su asociación con la realización de coronariografía durante el ingreso.

Resultados: La edad media fue de 79 ± 6 años y la puntuación GRACE media fue de 150 ± 21 puntos. Fueron tratados de manera conservadora 1.179 pacientes (16%). La presencia de cada enfermedad se asoció con un menor abordaje invasivo (ajustado por variables clínicas predictivas): enfermedad cerebrovascular (odds ratio [OR] = 0,78; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 0,64-0,95; p = 0,01), anemia (OR = 0,64; IC95%, 0,54-0,76; p < 0,0001), insuficiencia renal (OR = 0,65; IC95%, 0,56-0,75; p < 0,0001), arteriopatía periférica (OR = 0,79; IC95%, 0,65-0,96; p = 0,02), enfermedad pulmonar crónica (OR = 0,85; IC95%, 0,71-0,99; p = 0,05) y diabetes mellitus (OR = 0,85; IC95%, 0,74-0,98; p = 0,03). Asimismo, el aumento del número de enfermedades (carga de comorbilidad) se asoció con menor realización de coronariografías, ajustado por la escala GRACE: 1 enfermedad (OR = 0,66; IC95%, 0,54-0,81); 2 (OR = 0,55; IC95%, 0,45-0,69); 3 (OR = 0,37; IC95%, 0,29-0,47); 4 (OR = 0,33; IC95%, 0,24-0,45); ≥ 5 (OR = 0,21; IC95%, 0,12-0,36); todos p < 0,0001, en comparación con ninguna enfermedad.

Conclusiones: Conforme aumenta la comorbilidad disminuye la realización de coronariografías en ancianos con síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST. Se necesitan estudios que investiguen la mejor estrategia diagnóstico-terapéutica en estos pacientes.

Palabras clave: Comorbilidad. Ancianos. Síndrome coronario agudo. Coronariografía.

Abbreviations:

ACS: acute coronary syndrome. DM: diabetes mellitus. NSTEACS: non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Population ageing leads to an increase in the number of elderly patients who suffer non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS). This population group, that has been misrepresented in large studies, has a great comorbidity burden that increases with age1 and an important impact on prognosis.2-4 The ideal therapeutic strategy for the management of these patients is still unknown. The benefit of an invasive strategy in elderly patients with NSTEACS and comorbidities is still unclear.5-9 In general, elderly patients with comorbidities undergo fewer coronary angiographies despite their worse prognosis.10 This clinical practice —apparently in contrast with the recommendations published in the clinical practice guidelines11— seems to be based on the perception of a scarce benefit due to the worse intrinsic prognosis associated with comorbidities.

In this study the data of 11 Spanish NSTEACS registries were collected to set up a common database with over 7000 elderly patients with NSTEACS. In this preliminary analysis, the objective was to study the impact of comorbidities on the decision to go with invasive approach.

METHODS

Study design

The study was conducted from 11 cohorts of Spanish registries of patients with NSTEACS (annex).2,12-20 All cases were included in a single database of patients with chest pain and a diagnosis of NSTEACS, > 70 years of age and with, at least, a 1-year follow-up.

ANNEX. Registries included in the study.

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Valencia2 |

| Hospital Universitario Joan XXIII, Tarragona12 |

| Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, Barcelona13 |

| Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid14 |

| Hospital Universitario de San Juan, Alicante15 |

| LONGEVO multicenter registry16 |

| ACHILLES multicenter registry17 |

| Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo18 |

| Hospital Clínico Universitario, Santiago de Compostela19 |

| Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona20 |

| Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, Madrid* |

|

* Unpublished data. |

The anthropometric and social-demographic data, main cardiovascular risk factors, and analytical and hemodynamic data at admission or during hospitalization were registered.

Patients were treated according to each center routine clinical practice and the decision to treat the NSTEACS invasively, with or without a coronary angiography, was left to the discretion of the treating physician. The 6-month mortality GRACE risk score was determined in all the patients.21

A total of 6 conditions that proved to have a higher prognostic impact on elderly patients hospitalized due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in a previous study were included:22 renal failure (glomerular filtration rate < 60mL/min/1.73m2), anemia (hemoglobin levels < 11 g/dL), diabetes mellitus (DM), cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, and chronic pulmonary disease.

Endpoints

The study primary endpoint was to assess how the presence of comorbidities impacted the decision to perform a coronary angiography during admission.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as absolute values (percentages) and compared using the unpaired Student t test or the ANOVA. The continuous ones were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using the chi-square test.

Initially, the correlation between each disease and the performance of a coronary angiography through univariable analysis were assessed. Then, a first binary logistics regression model was conducted including the 6 conditions and the clinical variables associated with the performance of the coronary angiography in the univariable analysis. The odds ratio (OR) and the 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were estimated. Afterwards, patients were classified according to their comorbidity burden, defined by the number of concomitant conditions (from 0 to 6). A second logistics regression model was conducted where comorbidity burden was adjusted for the predictive clinical variables in the previous analysis. Finally, a third logistics regression model was conducted where the comorbidity burden was adjusted based on the GRACE risk score. Differences were considered statistically significant with P values < .05

RESULTS

A total of 7211 patients with a mean age of 79 ± 6 years were included; 62% were males. Table 1 shows the population baseline characteristics. The prevalence of comorbidities was DM in 2874 patients (40%), chronic kidney disease in 3070 patients (42.6%), anemia in 1025 (14.2%), peripheral arterial disease in 1006 (14%), chronic pulmonary disease in 1161 (16%), and previous stroke in 831 (11.5%).

Table 1. Differences in the baseline characteristics based on the therapeutic approach

| All N = 7211 | Conservative approach N = 1 179 (16) | Invasive approach N = 6 032 (84) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 79 ± 6 | 82 ± 6 | 78 ± 5 | .001 |

| Males | 4 441 (61.6) | 597 (50.6) | 3 844 (63.7) | .0001 |

| Smoking | 621 (8.6) | 72 (6.1) | 549 (9.1) | .0001 |

| Hypertension | 5 723 (79.4) | 943 (80) | 4 780 (79.2) | .58 |

| Dyslipidemia | 4 262 (59) | 609 (51.7) | 3 653 (60.6) | .0001 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 1 682 (23.3) | 371 (31.7) | 1 308 (21.7) | .0001 |

| Pervious percutaneous coronary intervention | 1 334 (19) | 175 (14.8) | 1 159 (19.2) | .0001 |

| Previous coronary surgery | 573 (7.9) | 104 (8.8) | 469 (7.8) | .24 |

| Previous heart failure | 641 (8.9) | 198 (16.8) | 443 (7.3) | .0001 |

| Killip ≥ 2 | 1 889 (26.2) | 463 (39.3) | 1 426 (23.6) | .0001 |

| ST-segment depression | 2 638 (36.6) | 396 (33.6) | 2 242 (37.2) | .02 |

| High troponin levels | 5 319 (73.7) | 920 (78) | 4 399 (73) | .001 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 54 ± 11 | 54 ± 12 | 55 ± 11 | .03 |