Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: When using radial access established as the approach of choice to perform coronary angiographies it is important to avoid radial spasm as it is the leading cause of access failure. This study aims to determine whether a topical anesthetic cream reduces the rate of radial spasm, as well as the increased gain with the use of different vasodilators.

Methods: Randomized, double-blind, and single-center clinical trial. Patients will be randomized to receive the anesthetic cream vs placebo, and 4 types of different vasodilator cocktails will be used in each group. The presence—or not—of radial spam and caliper gain will be analyzed.

Conclusions: Demonstrating the efficacy of the anesthetic cream, and different vasodilators to reduce radial spam would have a significant clinical impact, and justify its systematic use when performing coronary angiographies.

Registered at The Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) EudraCT number: 2017-000321-12.

Keywords: Radial spasm. Anesthetic cream. Vasodilators. Coronary angiography. Luminal diameter.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Con el abordaje radial establecido como técnica de elección para la coronariografía, es importante evitar el espasmo radial como principal causa de fallo en el acceso intravascular. En este estudio se pretende demostrar si la anestesia tópica en crema disminuye la incidencia de espasmo radial, así como conocer la ganancia de calibre con el uso de diferentes vasodilatadores.

Métodos: Ensayo clínico aleatorizado doble ciego en un solo centro. Los pacientes se aleatorizarán para recibir crema anestésica o placebo, y se utilizarán 4 tipos de cócteles vasodilatadores en cada grupo. Se analizará la presencia o no de espasmo radial y la ganancia de calibre como objetivos primarios.

Conclusiones: La demostración de la eficacia de la crema anestésica y de los diferentes vasodilatadores en la disminución del espasmo radial tendría un impacto clínico importante y justificaría su uso sistemático en la coronariografía.

Registrado en la Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) con n.º EudraCT: 2017-000321-12.

Palabras clave: Espasmo radial. Crema anestésica. Vasodilatadores. Coronariografía. Diámetro luminal.

Abbreviations

MLD: mean luminal diameter. RS: radial spasm. TA: topical anesthesia.

INTRODUCTION

Radial approach for cardiac catheterizations has become the most widely used across the world. In Spain it represents up to 75% of all the procedures performed and, in some centers, up to 91.1%.1 Compared to traditional femoral approach, this access has clearly proven its superiority from the safety standpoint of the procedures.2

Arterial canalization failure is often due to radial spasm (RS), and it can occur in up to 10% of all attempts. Also, it is associated with feminine sex, young age, low weight3 or deficits of certain enzymes that act on the endothelium.4 The special histological characteristics of this artery—with a high density of alpha-adrenergic receptors and smooth muscle cells—make it more prone to spasm.5

On the other hand, pain during lumbar puncture contributes to arterial canalization failure due to a higher frequency of appearance of spasm, vasovagal reaction with hypotension and discomfort for patient and operator, and the patient’s possible hemodynamic instability. Similarly, several patients complain of discomfort. As a matter of fact, the arterial puncture is described by many patients as the main moment of discomfort.5

Former studies have reported on the greater success achieved with isolated punctures for arterial gas analysis in the radial artery with the use of anesthesia injected around the puncture site. Also, more comfort and less pain have been reported by the patients.6 However, for many professionals injected anesthesia is ill-advised due to the pain caused by the injection. Also, because there are times that pain leads discomfort, and eventually RS.7 Despite of all this, the use of injected anesthesia is a common thing in procedures performed via radial access.

On the other hand, in the pediatric population as well as in different anatomical locations or in skin surgery, the use of topical anesthesia (TA) in the form of gel, cream or ointment has proven to minimize the pain associated with venous or arterial punctures, and some procedures too.8 The use of this type of anesthetic agents has not been properly studied in the cardiac catheterization setting. However, it could minimize the rate of RS, reduce pain when using this access, and improve the patient’s perception.

Together with TA, the use of different vasodilator drug combinations with unfractionated heparin (the so-called «radial cocktail»)—after successful arterial access—has proven to reduce the rates or arterial spasm and radial occlusion after the procedure.9-12 In particular drugs like verapamil, nitroglycerin, nitroprusside, nicorandil, isosorbide dinitrate or phentolamine in different doses have been compared with one another and also with placebo with heterogeneous results with arterial spams having been reported in 4% to 12% of the cases. Verapamil in doses of 5 mg and nitroglycerin 200 µg have yielded the best results so far. However, to this date, no comparison studies between the 2 drugs at these doses have ever been drawn or randomized for this matter.13 Therefore, it has not been fully established which is the best drug combination to prevent spasm and radial occlusion.

At our center, the current radial puncture procedure includes the use of injected anesthesia around the puncture site plus a cocktail of 5000 IU of unfractionated heparin, and 2.5 mg of verapamil. The rate of RS in our cath lab is around 10% of all punctures performed. In some patients, other drugs commonly available in our setting are often used—at the operator’s criterion—like nitroprusside, nitroglycerin or high doses of verapamil.

The objective of this study is to demonstrate whether the administration of topical anesthesia reduces the rate of RS and improves the patient’s perception regardless of the vasodilator used. Also, to compare arterial caliber gain with different vasodilators.

METHODS

Study design

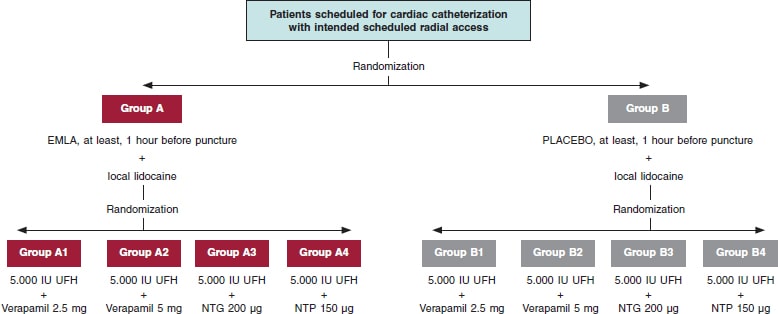

Double-blind randomized clinical trial conducted at a single center to analyze the rate of RS in patients treated with TA in cream with lidocaine 25 mg/g + prilocaine 25 mg/g (Emla) in topical solution compared to placebo, as well as the effect of vasodilators (table 1) (verapamil 2.5 mg or 5 mg, nitroglycerin 200 µg, nitroprusside 150 µg) in the arterial caliber while attempting vascular access to perform diagnostic transradial cardiac catheterization.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the E-RADIAL study

| Composition of the radial cocktail | Type of dilution |

|---|---|

| Cocktail #1 (verapamil 2.5 mg): | 12.5 mg of verapamil are diluted in 95 mL of FSS at 0.9%. A total of 20 mL are loaded in the syringe and fully administered. |

| Cocktail #2 (verapamil 5 mg): | 25 mg of verapamil are diluted in 90 mL of FSS at 0.9%. A total of 20 mL are loaded in the syringe and fully administered. |

| Cocktail #3 (nitroglycerin 0.2 mg): | 5 mg of nitroglycerin are diluted in 95 mL of FSS at 0.9%. A total of 4 mL of this solution are loaded in a 20 mL-syringe that is completed with FSS at 0.9%. The entire load of the syringe is administered. |

| Cocktail #4 (nitroprusside 0.150 mg): | 50 mg are diluted in 10 mL of FSS at 0.9% followed by the extraction of 1 mL of this solution that is diluted again in 100 mL of FSS at 0.9%. A total of 3 mL of the latter solution are loaded in a 20 mL-syringe that is completed with FSS at 0.9%. The entire load of the syringe is administered. |

|

FSS, physiological saline solution. |

|

Study population

The study will be conducted entirely at Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista of Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, Spain. All consecutive patients treated with diagnostic cardiac catheterization via radial access from November 2020 until completing the sample estimated will be included. Patients will need to meet the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion ones (table 2).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the E-RADIAL study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Age > 18 years | Allergy or intolerance to any of the drugs used in the study. |

| Informed consent signing | Baseline systolic arterial blood pressure < 90 mmHg. |

| Elective diagnostic cardiac catheterization with intended radial access |

Impossibility to understand the study or give the corresponding informed consent. |

| Introductor 5 French |

Ethical aspects

The study has been approved by the center ethics committee, and a favorable resolution was obtained. The study has been registered by Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) with registration No. EudraCT: 2017-000321-12. The study will observe the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. Also, written informed consent will be obtained from all the patients before joining the study.

Study endpoints

Primary endpoints

– Study the rate of RS using a topical anesthetic cream before radial puncture.

– Study radial artery caliber gain using different vasodilators.

Secondary endpoints

– Study the rate of radial-radial, and radial-femoral crossing with each strategy.

– Study the rate of vasovagal reactions requiring treatment in each group.

– Study parameters associated with pain during radial artery canalization using pain assessment analogue scales.

– Subjective assessment of pain and comfort by the patient using pain assessment analogue scales, and dedicated tests.

– Subjective assessment of the difficulty involved in the puncture and perception of RS by the operator using dedicated tests.

Study development

The administration of TA/placebo plus cocktail (table 1) will be fully randomized (figure 1). Both the patient and the treating interventional cardiology will be blind to the group they’ll be assigned to. If certain circumstances or complications occur, and if deemed necessary, the chain of secrecy can be broken only if investigators abide, and only under strict clinical judgement.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients from the E-RADIAL study. NTG, nitroglycerin; NTP, nitroprusside; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

Placebo with cream of similar color, consistency, and characteristics to Emla will be prepared, and they both will be marked with letters A (Emla) and B (placebo). Both placebo and the TA will be prepared by personnel from the hospital pharmacy unit. The nursing team in charge of the patients while waiting for cardiac catheterization at the cath lab will randomize each patient, and the only blind element of the study. TA or placebo will be administered in both wrists and, at least, 1 hour before the procedure.

Prior to puncture, 25 mg of subcutaneous local anesthesia will be injected into the puncture area (mepivacaine at 2%). Another 1-2 minutes will need to pass before it starts to work.

Different cocktails (table 1) will be prepared at the dilution often used at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete cath lab in 100 mL-jars of physiological saline solution (NaCl at 0.9%). Each jar will be marked with an alphanumeric code and its content will remain blind to everyone but the nursing team in charge of randomization.

Variable quantification during puncture

After monitoring the patient, arterial blood pressure will be determined invasively, as well as the baseline heart rate before administering the cocktail that will be used just after the introduction of hydrophilic guidewire (Radiofocus 5-Fr, Terumo, Japan). Similarly, arterial blood pressure will be recorded 2 minutes after the cocktail administration, as well as the maximum heart rate during puncture.

All vagal data that can occur and any other complications associated with access will be written down. The crossing rate to other accesses will also be studied prioritizing homolateral (cubital, distal radial) or contralateral access. Unless the operator specifies otherwise, femoral access will be set aside as the third go-to option.

Radial spasm determination and caliber gain quantification

RS will be defined as yes/no—both qualitative and dichotomically—and considered as sudden, transient, and abrupt narrowing of the radial artery during puncture. It will be clinically determined by, at least, 1 of the following events: loss of pulse during puncture, pain in the upper limb during catheter manipulation or entrapment. Its presence can also be determined through the angiography if spasm is seen during contrast injection.

Caliber gain will be determined through quantitative analysis of the radial artery luminogram. Therefore, an angiography will be immediately performed after the insertion of the introducer sheath plus another one 2 minutes after the injection of the antispasmodic cocktail. The radial artery caliber will be measured in the segment located between the tip of the arterial introducer sheath—2 cm away from it—and the location where it meets the humeral artery. Measurements will be acquired through computerized quantitative analysis (Xcelera, Philips, United States) after previous calibration of the arterial introducer sheath in the same segment before and after the cocktail injection to determine the mean luminal diameter (MLD).

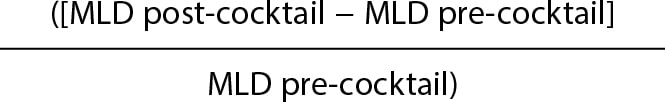

Caliber gain will be estimated in percentage according to the following formula:

Caliber gain =  × 100

× 100

Postoperative patient assessment

The patient will be asked to give his opinion on the radial puncture through the pain qualitative analogue scale, and the comfort scale consisting of 4 questions (annex of the supplementary data).

Similarly, the interventional cardiologist will give his evaluation through a survey including 2 questions (annex of the supplementary data), the difficulties found while performing the puncture, and how the procedure was accomplished via the access used.

Statistical analysis

The analysis will be conducted using the SPSS statistical software package for Windows v 21.0.

In descriptive statistics frequencies and percentages will be used to express discrete variables while mean, median, mode, standard deviation, and ranges will be used to express continuous variables. The rate of spams and other study components will be described through frequencies and percentages. The statistical analysis of the main variables will be conducted by intention-to-treat analysis. The chi-square test will be used to study differences among proportions while the continuous variables will be analyzed using the Student t test if normally distributed or else non-parametric tests if not normally distributed. In the presence of non-homogeneous distribution of confounding variables between the groups that will be analyzed, a logistic regression analysis will be conducted that should collect those clinically significant and non-homogeneously distributed parameters.

It is our will to conduct an intermediate analysis after which the study will move on or not (existence of a significant difference in the primary endpoint of RS > 7,5% between both groups).

Estimate of the sample size

According to former studies, it is estimated that the proportion of patients who will have RS in the control group will be 10%3,5 being the criterion of clinical effectiveness the reduction of this percentage off by 50%, which is why it will be necessary to have a minimum sample of 668 patients.

This volume of patients will allow us to confirm the statistical significance of the variations described in radial artery vasodilation with different types of vasodilators.

DISCUSSION

Currently, the arterial approach via radial access is used in 91.1%1 of all diagnostic and therapeutic coronary angiographies performed. In particular, the rates of bleeding complications have dropped thus contributing to the patients’ comfort. This access has facilitated the implementation of safe coronary angiography and outpatient angioplasty programs even in complex settings.14-16

Hand in hand with this and assuming pain hypothesis and adrenergic discharge are caused by puncture and risk factors for RS, different strategies have come up to contribute to the proper administration of anesthesia promoting patients’ comfort, and looking to reduce the rate of RS. As it happens in other places, at our center the use of subcutaneously injected anesthesia is the common practice since the direct correlation between less RS and proper anesthetic release in the punction area has already been confirmed.5 This study paves the way for a possible change in the routine clinical practice that could be associated—or not—with TA in cream pharmaceutical form. The medical literature includes different and very heterogeneous studies that, whether randomized or not, have tried to assess the utility of this type of creams. However, all of them include small samples (usually less than 100 patients), which makes it difficult to extrapolate the results.

We have a few examples of injected anesthesia vs a composite of TA plus injected anesthesia with favorable results from the latter.17,18 As far as we know, the heterogeneity of designs, and the small sample sizes make us question studies like these.

Although subcutaneous anesthesia—often with lidocaine—has proven to improve pain at the puncture site and reduce the rate of RS compared to TA there is a huge controversy regarding the active principles and drug combination that should be used, the specific action times of these drugs or which are the best pharmaceutical forms. However, it seems that the cream/ointment formulation, and the lidocaine/prilocaine combination (Emla type) yield the best results of all.18

Assuming that this type of formulation is the most widely studied and looking to achieve an adequate design with a representative sample, the E-RADIAL trial (Effectiveness in preventing radial spasm of different vasodilators and topic local anesthesia during transradial cardiac catheterization) has just been started. Although it is not the first trial to propose this hypothesis, it is the first one indeed to confirm it on a double-blind randomized clinical trial and compare it to different radial cocktails and a wide sample size.

This vasolidator comparison is a particularly new approach of our trial. There is some controversy on the use, or not, of such drugs: although some centers in our country do not use vasodilators on a routine basis, it seems to be proven that, overall, its use promotes arterial dilatation and, therefore, the navigability of catheters with lower rates of spasm.9,13 Currently, no such thing as head-on comparisons of cocktails have been drawn in trials to assess their efficacy and safety profile.19 Therefore, we designed our study taking into consideration that a comparison can be drawn among these different drugs in quantitative terms using MLD gain.

Although not part of our study primary endpoints we assume that—with radial access clearly established in the routine clinical practice of cath labs—the operator’s experience, his learning curve or even the rotating fellow/resident’s learning curve can have an impact on the rate of success of puncture, RS, as well as on other complications. This can be an interesting aspect we could discuss. As far as we know both in the current medical literature and good practice recommendations regarding the radial access20—although with limitations depending on the study analyzed—it seems reasonable to assume that the threshold to overtake the learning curve would be at around 30-5021 cases for conventional diagnostic coronary angiography, and > 100-200 cases for complex coronary anatomies22,23 or even in the ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome setting. In the E-RADIAL study, all operators widely exceed the number of cases recommended for this curve in diagnostic coronary angiography. Even so, while collecting data for the E-RADIAL we’ll have the possibility to know the identity of the operator who will perform the puncture, his years of experience using radial access, and whether a resident or a novel interventional cardiology (< 2 years of experience) was involved. Also, we will try to know descriptively the rate of puncture success, and whether any RS differences or other complications occurred.

The design of this clinical trial used 4 types of radial cocktail (table 1) from the ones most widely used ones in today’s clinical practice. However, this is also a controversial issue. On the one hand, some centers don’t use vasodilators systematically after radial puncture. On the other hand, choosing one over the other at the cath labs where they’re used is often based on the good clinical results obtained empirically in the routine clinical practice. Unlike the use of heparin to prevent radial occlusion, evidence is scarce regarding benefits from vasodilators, and no homogeneous head-on comparisons have been drawn among different drug cocktails. Verapamil in doses of 5 mg, and nitroglycerin in doses of 200 µg have yielded the best results so far. However, to this date, they have never been compared to one another at these doses or in a randomized way.13 Certain clinical features of the patients can turn the use of these cocktails into a controversial issue. As an example of this, in patients with very severe left ventricular dysfunction or severe aortic stenosis the use of these drugs can trigger significant adverse reactions, mainly hypotension or significant hemodynamic changes. Although, in theory, overall, these drugs are contraindicated in these clinical settings, the dose used, slow infusion, and other factors like the patients’ clinical stability, the existence—or not—of associated heart failure or different comorbidities can turn the use of these drugs into a safe practice. In its design the E-RADIAL study includes a head-on comparison of cocktails and some of the aforementioned drugs and doses. Therefore, it is an opportunity to know what the clinical implication of these drugs really is regarding adverse events.

One of the possible weaknesses or aspects that should be discussed in this trial is pain assessment and quantification. A reproducible design was attempted while assuming the difficulties posed by individual subjectivity. Therefore, following in the footsteps of former studies and registries, we decided to use the most standardized method available to this date in the medical literature: analogue scales.

Another possible weakness or cofounding factor in the study design is the systematic use of sodium heparin via arterial access as standard prevention against radial occlusion.20 According to the drug label24 the heparin-induced cardiac tamponade solution is often an acid solution with a pH between 5.0 and 7.5. The mean arterial pH is between the traditional values of 7.35 and 7.45, and could be partially altered when in contact with heparin solutions thus favoring, through different mechanisms, the development of RS, something not clearly established to this date. To solve this possible bias, the IV—not intraarterial use—of heparin was selected. Although evidence is certainly scarce and heterogeneous the IV use of heparin does not seem to increase the rate of radial occlusion, which is more associated with the heparin dose used and factors like compression time, type of material or size of the radial introducer sheath used that are well established as predictors of radial occlusion.25,26

CONCLUSIONS

The E-RADIAL study is the first randomized clinical trial to assess, on the one hand, the implications of less RS due to topical anesthesia and, on the other, arterial caliber gain with the use of different vasodilators.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J. J. Portero-Portaz: idea, methodology, validation, formal analysis, drafting of the original project; J. G. Córdoba-Soriano: idea, methodology, review and edition of the manuscript; A. Gutiérrez-Díez: idea, methodology, validation, formal analysis, review and edition of the manuscript; A. Gallardo-López, and D. Melehi El-Assali: idea, methodology, review and edition of the manuscript; L. Expósito-Calamardo, and A. Prieto-Lobato: research, review, and edition of the manuscript; E. García-Martínez, S. Ruiz-Sánchez, M. R. Ortiz Navarro, and E. Riquelme-Bravo: methodology, review, and edition of the manuscript; J. Jiménez-Mazuecos: idea, methodology, review and edition of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors declared having no affiliation or participation in any organization or entity with any financial or non-financial interest in the topic at stake or in the materials discussed in this manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the nursing personnel of our unit for their work, dedication, and availability during the entire study.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- RS is the leading cause of access failure in diagnostic or therapeutic coronary angiographies.

- The use of injected local anesthesia is standardized and reduces the rate of RS.

- There is no consensus on the use or non-use of vasodilators, which depends on the characteristics and routine clinical practice of each center.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The E-RADIAL study can pave the way to systematization in the use of other type of anesthesia.

- It will provide relevant information on the effectiveness of different vasodilators through head-on comparisons of the most widely used agents.

REFERENCES

1. Romaguera R, Ojeda S, Cruz-González I, Moreno R. Registro Español de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista. XXX Informe Oficial de la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (1990-2020) en el año de la pandemia de la COVID-19. Rev. Esp Cardiol. 2021;74:1095-1105.

2. Rao SV, Turi ZG, Wong SC, Brener SJ, Stone GW. Radial versus femoral access. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(17 Suppl):S11-20.

3. Dandekar VK, Vidovich MI, Shroff AR. Complications of transradial catheterization. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:39-50.

4. Kocayigit I, Cakar MA, Kahyaog˘lu B, Aksoy MNM, Tatli E, Akdemir R. The relationship between serum asymmetric dimethylarginine levels and radial artery spasm. Anatol J Cardiol. 2020;23:228-232.

5. Ho HH, Jafary FH, Ong PJ. Radial artery spasm during transradial cardiac catheterization and percutaneous coronary intervention: incidence, predisposing factors, prevention, and management. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;

13:193-195.

6. Hudson TL, Dukes SF, Reilly K. Use of local anesthesia for arterial punctures. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:595-599.

7. France JE, Beech FJ, Jakeman N, Benger JR. Anaesthesia for arterial puncture in the emergency department: a randomized trial of subcutaneous lidocaine, ethyl chloride or nothing. Eur J Emerg Med. 2008;15:218-220.

8. Tran NQ, Pretto JJ, Worsnop CJ. A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of topical amethocaine in reducing pain during arterial puncture. Chest. 2002;122:1357-1360.

9. Boyer N, Beyer A, Gupta V, et al. The effects of intra-arterial vasodilators on radial artery size and spasm: implications for contemporary use of trans-radial access for coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14:321-324.

10. Ruiz-Salmerón RJ, Mora R, Vélez-Gimón M, et al. Espasmo radial en el cateterismo cardíaco transradial. Análisis de los factores asociados con su aparición y de sus consecuencias tras el procedimiento. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:504-511.

11. Majure DT, Hallaux M, Yeghiazarians Y, Boyle AJ. Topical nitroglycerin and lidocaine locally vasodilate the radial artery without affecting systemic blood pressure: a dose-finding phase I study. J Crit Care. 2012;27:532.e9-13.

12. Beyer AT, Ng R, Singh A, et al. Topical nitroglycerin and lidocaine to dilate the radial artery prior to transradial cardiac catheterization: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial: the PRE-DILATE Study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:2575-2578.

13. Kwok CS, Rashid M, Fraser D, Nolan J, Mamas M. Intra-arterial vasodilators to prevent radial artery spasm: a systematic review and pooled analysis of clinical studies. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:484-490.

14. Córdoba-Soriano JG, Rivera-Juárez A, Gutiérrez-Díez A, et al. The Feasibility and Safety of Ambulatory Percutaneous Coronary Interventions in Complex Lesions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20:875-882.

15. Córdoba-Soriano JG, Jiménez-Mazuecos J, Rivera Juárez A, et al. Safety and Feasibility of Outpatient Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Selected Patients: A Spanish Multicenter Registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70:535-542.

16. Gallego-Sánchez G, Gallardo-López A, Córdoba-Soriano JG, et al. Safety of transradial diagnostic cardiac catheterization in patients under oral anticoagulant therapy. J Cardiol. 2017;69:561-564.

17. Tatlı E, Adem Yılmaztepe M, Gökhan Vural M, et al. Cutaneous analgesia before transradial access for coronary intervention to prevent radial artery spasm. Perfusion. 2018;33:110-114.

18. Youn YJ, Kim WT, Lee JW, et al. Eutectic mixture of local anesthesia cream can reduce both the radial pain and sympathetic response during transradial coronary angiography. Korean Circ J. 2011;41:726-732.

19. Shehab A, Bhagavathula AS, Kaes AA, et al. Effect of Vasodilatory Medications on Blood Pressure in Patients Undergoing Transradial Coronary Angiography: A Comparative Study. Heart Views. 2020;21:75-79.

20. Shroff AR, Gulati R, Drachman DE, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement update on best practices for transradial angiography and intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;95:245-252.

21. Hess CN, Peterson ED, Neely ML, et al. The learning curve for transradial percutaneous coronary intervention among operators in the United States: a study from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2014;

129:2277-2286.

22. Azzalini L, Ly HQ. Letter by Azzalini and Ly regarding article, “The learning curve for transradial percutaneous coronary intervention among operators in the United States: a study from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry”. Circulation. 2015;131:e357.

23. Hamon M, Pristipino C, Di Mario C, et al. European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions; Working Group on Acute Cardiac Care of the European Society of Cardiology; Working Group on Thrombosis on the European Society of Cardiology. Consensus document on the radial approach in percutaneous cardiovascular interventions: position paper by the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions and Working Groups on Acute Cardiac Care** and Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology.EuroIntervention. 2013; 8:1242–1251.

24. Ficha técnica de la heparina sódica. Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Available online: https://cima.aemps.es/cima/dochtml/ft/56029/FT_56029.html. Accessed 20 Nov 2021.

25. Pancholy SB. Comparison of the effect of intra-arterial versus intravenous heparin on radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1083-1085.

26. Rashid M, Kwok CS, Pancholy S, et al. Radial Artery Occlusion After Transradial Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 201625;5:e002686.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Noncompliant balloon postdilatation of coronary stents improves clinical results. Regular noncompliant balloons (RegNC) have less crossability and a tapered-tip that can complicate successful stent postdilatation. The mechanical conditions of a new spherical tip non-compliant balloon (SphNC) could facilitate stent postdilatation. We tried to evaluate the effectiveness of a new SphNC in the routine percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) practice.

Methods: Prospective multicenter technical registry to assess the effectiveness of a new SphNC for stent postdilatation with 2 study arms: use of SphNC as the first choice or as the secondary choice after RegNC failure. The primary endpoint was technical success defined as advancing the SphNC across the stent segment. Secondary endpoints were angiographic success defined as technical success and residual stenosis < 30% with final TIMI grade-3 flow, and procedural success defined as angiographic success without mechanical stent complications or any perioperative major adverse cardiovascular events.

Results: The SphNC was used in 263 lesions (177 lesions as first choice, and 86 after RegNC failure) in 250 procedures. The use of the complex technique to advance the SphNC was low (9.9%). Technical, angiographic, and procedural success rates were 98.9%, 98.3%, and 98.3%, respectively, as the first choice, and 98.8%, 97.7%, and 96.5%, respectively, after RegNC failure. SphNC had similar size (3.39 mm ± 0.6 mm vs 3.34 mm ± 0.6 mm; P = nonsignificant), and shorter lengths (11 mm ± 2 mm vs 12 mm ± 3 mm; P = .005) compared to RegNC. No stent-related mechanical complications were reported.

Conclusions: SphNC for coronary stent postdilatation in the routine PCI clinical practice has a very high technical success rate as the first choice (98.9%), as well as in cases of RegNC failure (98.8% with low complex technique requirements, and a safe profile).

Keywords: Complex PCI. Stent postdilatation. Tapered-tip balloon. Spherical tip balloon.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La posdilatación de stents coronarios con balones no distensibles mejora los resultados clínicos. Los balones no distensibles normales (RegNC) presentan peor navegabilidad y tienen una punta cónica que puede dificultar la posdilatación exitosa. Las condiciones mecánicas de un nuevo balón no distensible con punta esférica (EsfNC) podrían facilitar la posdilatación del stent. Evaluamos la efectividad del EsfNC en la posdilatación coronaria para la intervención coronaria percutánea en la práctica clínica habitual.

Métodos: Registro técnico prospectivo y multicéntrico para evaluar la efectividad de un nuevo EsfNC en posdilatación coronaria, con 2 grupos de estudio: uso de EsfNC como primera opción o uso de EsfNC ante el fracaso de RegNC. El evento primario fue el éxito técnico, definido como conseguir avanzar el EsfNC hasta el segmento que posdilatar dentro del stent. Los eventos secundarios fueron el éxito angiográfico, definido como éxito técnico junto con estenosis residual < 30% con flujo final TIMI 3, y el éxito del procedimiento, definido como éxito angiográfico sin complicación mecánica del stent ni eventos cardiovasculares mayores periprocedimiento.

Resultados: Se usó EsfNC en 263 lesiones (en 177 como primera opción y en 86 tras el fracaso de RegNC), en 250 procedimientos. Se usaron técnicas complejas para avanzar el EsfNC en el 9,9% de los procedimientos. Los porcentajes de éxito técnico, angiográfico y de procedimiento fueron del 98,9%, el 98,3% y el 98,3% como primera opción, y del 98,8%, el 97,7% y el 96,5% tras fracaso de RegNC, respectivamente. Los EsfNC tuvieron similar calibre (3,39 ± 0,6 frente a 3,34 ± 0,6 mm; p = no significativo) y longitud más corta (11 ± 2 frente a 12 ± 3 mm; p = 0,005) que los RegNC. No se comunicaron complicaciones mecánicas del stent.

Conclusiones: La posdilatación coronaria con EsfNC para la intervención coronaria percutánea en la práctica clínica habitual muestra un porcentaje muy alto de éxito técnico, tanto en primera opción (98,9%) como en casos de fracaso de RegNC (98,8%), con baja necesidad de técnicas complejas y buen perfil de seguridad.

Palabras clave: Intervención coronaria percutánea compleja. Posdilatación coronaria. Balón no distensible. Balón no distensible punta esférica.

Abbreviations

NC: noncompliant balloon. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. RegNC: regular noncompliant balloon. SphNC: spherical tip noncompliant balloon.

INTRODUCTION

Optimal stenting is crucial in the long-term clinical outcomes while proper stent expansion and apposition reduce the risk of thrombosis and restenosis.1 Coronary stent postdilatation increases luminal area while reducing stent strut malapposition.2,3

Unlike semicompliant balloons, noncompliant (NC) balloon postdilatation allows uniform dilatation at higher pressures, which reduces the risk of damage to the vessel wall (edge dissection or coronary perforation),4 and is associated with greater stent expansion and a lower rate of target lesion revascularization.5 Therefore, postdilatation using NC balloons is a common strategy to increase the luminal area of underexpanded stents or increase the stent proximal caliber in long lesions or in bifurcation techniques like the proximal optimization technique (POT) or the conventional kissing-balloon technique in a safe and predictable way.6,7

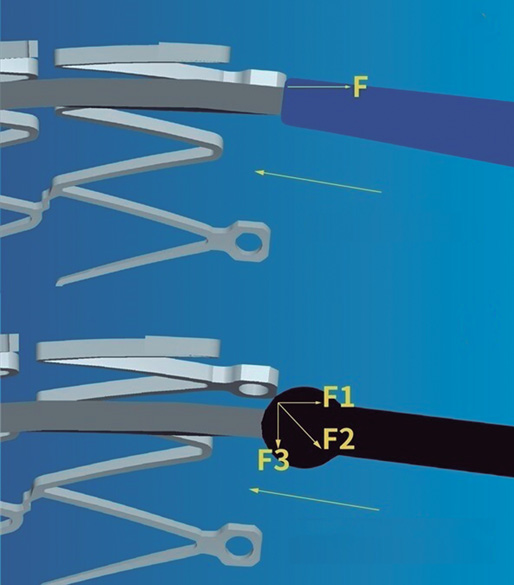

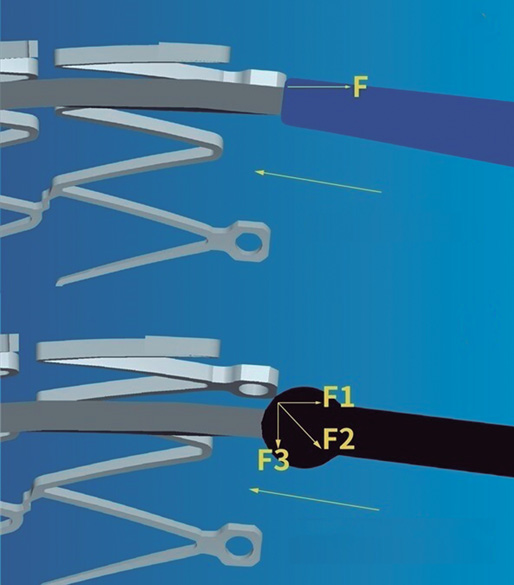

The navigability of NC balloons is more limited, a significant setback in cases of coronary tortuosity, calcified lesions or proximal stent edge malapposition. Regular noncompliant balloons (RegNC) include a cone-shaped tip that can collide with the struts or with the proximal stent edge, thus conditioning a force vector opposed to the push force that can potentially interfere with its advancement (figure 1A), and eventually lead to mechanical stent failure in cases of inadequate coaxiality. In these cases, the use of complex techniques (buddy-wire, buddy-balloon, anchoring...) or specific devices (guide catheter extension systems) are often needed to advance the balloon, which increases the cost of the procedure.

Figure 1. A: the cone-shaped tip of a regular noncompliant balloon can collide with the stent struts thus conditioning a force (F) vector opposed to the push force that can potentially interfere with its advancement. B: the spherical tip contributes to decomposing and reducing the resistance force vector opposed to the push vector, thus facilitating the balloon advancement towards the inside of the stent. Courtesy of APT Medical, China.

The cone-shaped tip has been replaced by a spherical tip in a new NC balloon (NC Conqueror Spherical tip, APT Medical, China) (SphNC). Despite its greater crossing profile (0.039 in), the spherical tip contributes to decomposing and reducing the resistance force vector opposed to the push vector (figure 1B), facilitating the advancement of the balloon until reaching the inside of the stent and the post-dilatable segment.

Figure 2. Actual appearance of the spherical tip noncompliant balloon used in the study. Courtesy of APT Medical, China.

Our objective is to assess the effectiveness of this new SphNC in coronary postdilatation during percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the routine clinical practice.

METHODS

The RECONQUISTHA trial is a prospective and multicenter technical registry conducted in 16 high volume PCI-capable centers (> 500 PCIs/year)8 designed to assess the effectiveness of SphNC in coronary postdilatation during PCI in the routine clinical practice. Since it is a technical registry that used no personal or clinical data on a device approved with CE marking no ethics committee approval or informed consent forms were required.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The only inclusion criterion was the indication for coronary postdilatation with the SphNC according to the operator (long, calcified, ostial lesion, bifurcation and angiographic or stent balloon underexpansion). The exclusion criteria were the use of a ≤ 5-Fr guide catheter, vessel size < 2mm or > 5mm, jailed branch postdilatation without previous opening of the stent struts of the main vessel towards such branch or finding 1 of the following scenarios before postdilatation: mechanical stent failure, stent edge dissection ≥ C, coronary perforation or TIMI grade ≤ 2 flow in the main vessel or lateral branch.

Procedure

All lesions were treated with stenting according to the operator’s criterion and according to the routine clinical practice (arterial access, guide catheter caliber, predilatation or plaque modification, and intracoronary imaging). Also, they should be treated with standard antithrombotic treatment (dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid, and P2Y12 receptor inhibitors prior to the PCI plus weight-adjusted unfractionated heparin at doses of 100 IU/kg with further boluses to achieve activated coagulation times between 250 s and 300 s).

The use of the SphNC was considered in 2 different clinical settings that categorized the lesions into 2 study groups: use of SphNC as first-line treatment, and use of SphNC as a second choice after failed RegNC advancement. Complex techniques like the buddy-wire, buddy-balloon, anchoring or guide catheter extension system were allowed to advance both the RegNC and the SphNC. In cases where the second choice after failed RegNCn advancement was used despite the use of a complex technique, the same complex technique with the SphNC was advised too.

The spherical tip noncompliant balloon

The NC Conqueror Spherical tip balloon (APT Medical, China) is a rapid exchange balloon catheter for percutaneous coronary interventions that is compatible with a 0.014 in intracoronary guidewire. This device has a distinctive tungsten radiopaque spherical tip (0.039 in crossing profile) designed to minimize resistance while advancing the balloon towards the inside of the stent (figure 2). It is available in calibers ranging from 2 mm to 5 mm in intervals of 0.25 mm to 0.5 mm, and lengths of 6 mm, 8 mm, 12 mm, 15 mm, 20 mm, and 30 mm. Nominal pressure stands at 12 atm, and rated pressure burst at around 20 atm (18 atm in 4.5 mm to 5 mm calibers). The device has the CE marking.

Definition of endpoints

The study primary endpoint was technical success defined as the successful advancement of the SphNC until reaching the stent post-dilatable segment. Secondary endpoints were angiographic success—defined as technical success with residual stenosis < 30% with final TIMI grade-3 flow—and procedural success defined as angiographic success without mechanical stent failure or perioperative major adverse cardiovascular events like myocardial infarction—based on the criteria established by the Academic Research Consortium [ARC]-29—stroke, coronary perforation, need for emergency heart surgery or death.

The hypothesis was to consider the study positive if technical success was achieved in > 80% of the lesions regarding the use of the SphNC as the go-to option (according to data published on technical success rates with postdilatation balloons10), and in > 30% regarding the use of the SphNC after failed RegNC advancement (random criterion based on the success of the new balloon in 1 out of 3 cases of failed RegNC advancement).

Data curation

The characteristics of the lesion and the PCI, the indication for postdilatation, any information on the devices used, and quantitative and procedural angiographic results were collected prospectively. Data was introduced in an anonymized electronic database specifically designed for the purpose of the study. Lesions were categorized based on the classification established by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA).11 Coronary calcification was defined as moderate whenever coronary radiopacities would be found prior to the injection of contrast or severe whenever these radiopacities would damage both sides of the arterial lumen.12 Coronary tortuosity was defined as moderate if ≥ 3 consecutive curvatures between 45° and 90° were found during diastole or severe if any previous curvatures between 90° and 180° would be found or that encompassed the lesion.13 Angulation inside the lesion was measured as the angle between the start and the end of stenosis. The presence of ostial stenosis > 50% in the branch lateral to the lesion or the need to place the protection guidewire in the lateral branch was considered bifurcation. The stent suboptimal expansion was defined as residual stenosis ≥ 10% on the coronary quantitative angiography after the PCI. Residual stenosis ≥ 30% was considered stent underexpansion (the use of intracoronary imaging was not mandatory). Mechanical stent failure was defined as longitudinal stent deformation or fracture. The patients’ personal or clinical data were not collected.

Statistical analysis

In each of the study groups the overall and individual data were analyzed (SphNC as the go-to option, and as the second choice after failed RegNC advancement). Data was expressed as percentages regarding the categorical variables or as mean and standard deviation regarding the continuous ones. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate). Continuous variables were compared using the Student t test. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

From February through June 2021, the SphNC was used in 263 lesions (in 177 lesions as the go-to option, and in 86 lesions after failed RegNC advancement) in a total of 250 procedures. All the lesions were treated with state-of-the-art drug-eluting stents. The characteristics of the lesions and the PCIs, and the immediate angiographic results—both overall and with the use of the SphNC as the first choice or after failed RegNC advancement—are shown on table 1 and table 2. A total of 9.9% of the lesions required complex techniques to move the SphNC forward. Lesions in the failed RegNC group were more unfavorable with a lower rate of direct stenting, greater tortuosity and angulation inside the lesion, more need for cutting balloon during predilatation, shorter SphNC length, and a higher rate of angiographic data of suboptimal stent expansion.

Table 1. Characteristics of the lesions

| Total (N = 263) |

SphNC as the go-to option (N = 177) |

SphNC after failed RegNC (N = 86) |

P* | Total (N = 263) |

SphNC as the go-to option (N = 177) |

SphNC after failed RegNC (N = 86) |

P* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target vessel | .27 | AHA classification | .1 | ||||||||

| LAD | 40.7% (107) | 41.8% (74) | 38.4% (33) | A | 2.7% (7) | 4% (7) | 0% (0) | ||||

| LCx | 20.5% (54) | 17.5% (31) | 26.7% (23) | B1 | 23.6% (62) | 26% (46) | 18.6% (16) | ||||

| RCA | 30% (79) | 31.1% (55) | 27.9% (24) | B2 | 45.2% (119) | 44.1% (78) | 47.7% (41) | ||||

| LMCA | 7.6% (20) | 8.5% (15) | 5.8% (5) | C | 26.4% (57) | 26% (46) | 33.7% (29) | ||||

| CABG | 1.2% (3) | 1.1% (2) | 1.2% (1) | Baseline TIMI flow | .65 | ||||||

| Location | .98 | 0 | 21.7% (57) | 20.9% (37) | 23.3% (20) | ||||||

| Proximal | 42.6% (112) | 42.9% (76) | 41.9% (36) | 1 | 1.1% (3) | 1.7% (3) | 0% (0) | ||||

| Medial | 43.3% (114) | 42.9% (76) | 44.2% (38) | 2 | 8.4% (22) | 8.5% (15) | 8.1% (7) | ||||

| Distal | 14.1% (37) | 14.1% (25) | 12% (12) | 3 | 68.8% (181) | 68.9% (122) | 68.6% (59) | ||||

| Calcification | .54 | Bifurcation | 29.7% (78) | 27.7% (49) | 33.7% (29) | .31 | |||||

| Moderate | 39.5% (104) | 41.2% (73) | 36% (31) | 2 stents | 7.6% (20) | 5.6% (10) | 11.6% (10) | .16 | |||

| Severe | 18.6% (49) | 16.9% (30) | 22.1% (19) | Ostial | 11.1% (24) | 13% (23) | 8.1% (7) | .24 | |||

| Tortuosity | <.001 | CTO | 5.7% (15) | 7.9% (14) | 1.2% (1) | .03 | |||||

| Moderate | 35.7% (94) | 35% (62) | 37.2% (32) | STEMI | 16.3% (43) | 13.6% (24) | 22.1% (19) | .08 | |||

| Severe | 6.1% (16) | 1.7% (3) | 15.1% (13) | Lesion on the QCA | |||||||

| Lesion angulation | <.001 | MLD (mm) | 1.01 ± 1.04 | 1.05 ± 1.06 | 0.9 ± 1 | .27 | |||||

| <30 ° | 62.4% (164) | 70.1% (124) | 46.5% (40) | VRD (mm) | 3.34 ± 0.62 | 3.3 ± 0.59 | 3.44 ± 0.65 | .09 | |||

| 30º-70 ° | 30.8% (81) | 26% (46) | 40.7% (35) | Percent diameter stenosis (%) | 83 ± 17 | 82 ± 17 | 84 ± 16 | .48 | |||

| > 70 ° | 6.8% (18) | 4% (7) | 12.8% (11) | Stenotic area (%) | 88 ± 13 | 87 ± 14 | 89 ± 12 | .13 | |||

|

AHA, American Heart Association; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; MLD, minimal lumen diameter; QCA, quantitative coronary angiography; RCA, right coronary artery; RegNC, cone-shaped tip regular noncompliant balloon; SphNC, spherical tip noncompliant balloon; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; VRD, vessel reference diameter. * P between SphNC groups as the go-to option, and SphNC after failed RegNC. |

|||||||||||

Table 2. Characteristics of percutaneous coronary intervention and angiographic outcomes

| Total (N = 263) |

SphNC as the go-to option (N = 177) |

SphNC after failed RegNC (N = 86) |

P* | Total (N = 263) |

SphNC as the go-to option (N = 177) |

SphNC after failed RegNC (N = 86) |

P* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque modification | Kissing balloon | 1.9% (5) | 2.3% (4) | 1.2% (1) | ||||||

| Noncompliant balloon | 44.9% (118) | 47.5% (84) | 39.5% (34) | .45 | Other | 1.5% (4) | 1.1% (2) | 2.3% (2) | ||

| Scoring balloon | 12.5% (33) | 9% (16) | 19.8% (17) | .14 | SphNC | |||||

| Cutting balloon | 4.9% (13) | 2.3% (4) | 10.5% (9) | .01 | Caliber (mm) | 3.36 ± 0.55 | 3.34 ± 0.53 | 3.39 ± 0.6 | .5 | |

| Lithotripsy balloon | 1.9% (5) | 1.7% (3) | 2.3% (2) | .66 | Length (mm) | 12 ± 3 | 13 ± 2 | 11 ± 2 | <.001 | |

| Rotational atherectomy | 1.9% (5) | 1.1% (2) | 3.5% (3) | .33 | Atm | 18 ± 3 | 18 ± 2 | 18 ± 3 | .09 | |

| Direct stenting | 14.1% (37) | 16.9% (30) | 8.1% (7) | .05 | Complex technique | .52 | ||||

| Stent | Guide catheter extension system | 7.6% (20) | 7.9% (14) | 7% (6) | ||||||

| Caliber (mm) | 3.07 ± 0.52 | 3.04 ± 0.49 | 3.12 ± 0.57 | .3 | Buddy-wire | 1.9% (5) | 1.1% (2) | 3.5% (3) | ||

| Length (mm) | 27 ± 11 | 27 ± 10 | 27 ± 11 | .95 | Anchoring | 0.4% (1) | 0.6% (1) | 0% (0) | ||

| Atm | 14 ± 2 | 15 ± 2 | 14 ± 2 | .02 | Intracoronary imaging | 9.5% (27) | 9.1% (16) | 10.4% (9) | .51 | |

| Number of stents in the lesion | .47 | QCA after PCI | ||||||||

| 1 | 81.4% (214) | 81.4% (144) | 81.4% (70) | MLD (mm) | 3.23 ± 0.58 | 3.19 ± 0.56 | 3.29 ± 0.61 | .21 | ||

| 2 | 13.7% (36) | 12.4% (22) | 16.3% (14) | Percent diameter stenosis (%) | 4 ± 5 | 3 ± 5 | 4 ± 5 | .18 | ||

| 3 | 5% (13) | 6.2% (11) | 2.3% (2) | Stenotic area (%) | 6 ± 8 | 5 ± 8 | 7 ± 8 | .05 | ||

| Overall stent length (mm) | 32 ± 18 | 32 ± 18 | 32 ± 16 | .96 | Stent expansion | .03 | ||||

| Postdilatation indication | .29 | Optimal | 97.7% (257) | 99.4% (176) | 94.2% (81) | |||||

| Long lesion | 39.9% (105) | 44.6% (79) | 30.2% (26) | Suboptimal | 1.9% (5) | 0.6% (1) | 4.7% (4) | |||

| Suboptimal expansion | 30.8% (81) | 28.2% (50) | 36% (31) | Underexpansion | 0.4% (1) | 0% (0) | 1.2% (1) | |||

| POT | 16% (42) | 13% (23) | 22.1% (19) | Final TIMI grade-3 flow | 99.6% (262) | 99.4% (176) | 100% (86) | 1 | ||

| Calcified lesion | 6.8% (18) | 7.3% (13) | 5.8% (5) | |||||||

| Aorto-ostial lesion | 3% (8) | 3.4% (6) | 2.3% (2) | |||||||

|

Atm, balloon inflation atmospheres; MLD, minimal lumen diameter; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; POT, proximal optimization technique in bifurcation; QCA, quantitative coronary angiography; RegNC, cone-shaped tip regular noncompliant balloon; SphNC, spherical tip noncompliant balloon; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. * P between SphNC groups as the go-to option, and SphNC after failed RegNC. |

||||||||||

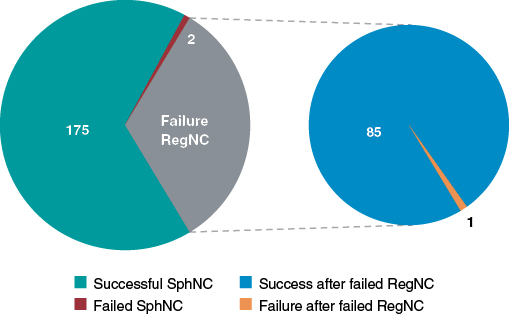

The overall rates of technical, angiographic, and procedural success were very high and similar between both groups (table 3).

Table 3. Rates of primary and secondary endpoints

| Total (N = 63) | SphNC as the go-top option (N = 177) | SphNC after failed RegNC (N = 86) | P* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | ||||

| Technical success | 98.9% (260) | 98.9% (175) | 98.8% (85) | 1 |

| Secondary endpoint | ||||

| Angiographic success | 98.1% (258) | 98.3% (174) | 97.7% (84) | .66 |

| Procedural success | 97.7% (257) | 98.3% (174) | 96.5% (83) | .33 |

| Mechanical stent failure | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | N/A |

| Perioperative complications | 0.4% (1) | 0% (0) | 1.2% (1) | .32 |

|

N/A, non-applicable; RegNC: cone-shaped tip regular noncompliant balloon; SphNC, spherical tip noncompliant balloon. * P between SphNC groups as the go-to option, and SphNC after failed RegNC. |

||||

The rate of technical success in the same lesion where the RegNC had failed was very high (98.8%): only 1 SphNC failed too (figure 3). The SphNC and the RegNC had a similar mean caliber (3.39 ± 0.6 mm vs 3.34 ± 0.6 mm; P = .06) while the SphNC had a shorter mean length (11 ± 2 mm vs 12 ± 3 mm; P = .005). The length of the SphNC was shorter, similar or longer in 36%, 46.5%, and 17.5% of the lesions, respectively. The same complex techniques were used to advance the RegNC and the SphNC in 7 lesions (the guide catheter extension system and the buddy-wire technique were used in 6 and 1 cases, respectively). The buddy-wire technique was used in 2 lesions to advance the SphNC, but not previously with the RegNC. In 1 lesion where the RegNC could not be advanced despite anchoring, the SphNC was moved forward without the need for a complex technique. Both the RegNC and the SphNC had been previously used on 3 and 9 occasions, respectively for predilatation purposes.

The description of failed primary and secondary endpoints with the SphNC is shown on table 4. In 2 of the 3 cases without technical success regarding the SphNC, a shorter RegNC was eventually advanced. No instances of mechanical stent failure were reported. One proximal fracture of the catheter hypotube was reported due to excessive resistance during push in 1 SphNC. Nonetheless, the device could be retrieved uneventfully. Only 1 major adverse cardiovascular event was reported: 1 distal branch perforation due to an angioplasty guidewire unrelated with the use of the SphNC that occurred while unsuccessfully trying to advance the RegNC. However, according to the definitions of the study protocol, it was adjudicated as lack of procedural success.

Table 4. Description of cases of failed spherical tip noncompliant balloon

| Case of failed SphNC | Failed event | Use of SphNC | Postdilatation indication | Success of other NC balloons | Complex technique | Complication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion #46 | Technical success | Go-to option | Suboptimal expansion | Yes | No | No |

| Lesion #71 | Technical success | Go-to option | Long lesion | No | No | No |

| Lesion #83 | Technical success | Failed RegNC | POT | Yes | No | Hypotube rupture |

| Lesion #84 | Angiographic success (QCA) | Failed RegNC | Suboptimal expansion | N/A | Guide catheter extension system | No |

| Lesion #224 | Angiographic success (TIMI flow) | Go-to option | Suboptimal expansion | N/A | No | No |

| Lesion #258 | Procedural success | Failed RegNC | POT | N/A | No | Coronary perforation |

|

NA, non-applicable; POT, proximal optimization technique in bifurcation; QCA, quantitative coronary angiography; RegNC, cone-shaped tip regular noncompliant balloon; SphNC, spherical tip noncompliant balloon; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

||||||

Figure 3. Overall technical success and failure of the spherical tip noncompliant balloon (SphNC), as well as in cases of failed regular noncompliant balloon (RegNC); section chart on the right.

DISCUSSION

As far as we know, it is the first time that a clinical trial—the REPIC02-RECONQUISTHA—reports on the most extensive experience using SphNC for coronary stent postdilatation. The registry included 16 high volume PCI-capable centers and collected data from 263 lesions where SphNCs were used at the operator’s discretion both as the go-to and second choice after failed RegNC advancement in the same lesion. Based on the initial hypothesis, the study can be considered positive; findings can be summarized as follows: a) very high rates of technical, angiographic and procedural success defined, respectively, as the capacity to move forward towards the inside of the stent and reach an adequate expansion without mechanical stent failure or periprocedural complications; b) very high rates of technical, angiographic and procedural success in the same lesions where the RegNC failed; and c) lower need for complex techniques to achieve technical success.

Over the last few years, the arrival of new techniques and modern devices has facilitated the performance of successful PCIs on more complex lesions in the routine clinical practice. Although the operators were not specifically encouraged to include complex lesions in the study, our data show this reality where over 70% of the lesions were type B2/C, and nearly 50% showed significant calcification, tortuosity or angulation inside the lesion. These characteristics reduce the success of the PCI14,15 and can eventually lead to stent malapposition16 and underexpansion17 or difficulties advancing the devices until reaching such stents, which means that the availability of effective and safe postdilatation balloons is essential to perform successful PCIs.

There is no data in the medical literature to compare or discuss our findings. Our study can be considered positive as it exceeded 80% of the success anticipated in the initial hypothesis. Despite the complexity of the lesions reported, the overall and subgroup outcomes of use of the SphNCs as the go-to option are nothing new since they can be expected in the assessment of any NC balloons (rate of success and proper stent expansion > 90%)10 since it is rare to find difficulties or impossibilities if complex techniques are used to advance these devices. However, these maneuvers can lead to severe complications like mechanical stent deformation.18,19 The lack of mechanical stent failure in our series places the SphNC as an effective and safe device for coronary postdilatation.

After the first 200 procedures, the percentage of cases where the SphNC was used in lesions where the RegNC would have failed was low. Since focus was on assessing the SphNC performance in this context, only inclusions in this subgroup were allowed later on. As already mentioned, the rate of RegNC failure is rare, and the rhythm of inclusion of the next 50 procedures was a slower. We designed this study group considering that the sequential use of a SphNC in the same lesion where a RegNC had failed would show the potential benefit of this new device. The SphNC achieved technical success in 98.8% of the lesions in this subgroup and validated its superiority in the exact same lesions where the RegNC had failed, which can be considered the most valuable piece of information from our study. The mean SphNC length was shorter compared to the RegNC (a 1 mm difference, which is statistically significant due to similar and narrow standard deviations, yet of uncertain practical significance). However, the operators used SphNCs and RegNCs of similar length in most of the lesions. In this study subgroup, lesions were more unfavorable, which may explain the rate of failure with RegNCs, the discretely low rate of angiographic and procedural success reported, and the presence of the complications described (fracture of the SphNC hypotube or coronary perforation).

It has been reported that the tortuosity and angulation seen until the lesion are predictors of failed PCI or perioperative complications.14,15,20 In our series, their prevalence was high—around 40%—and up to 50% in lesions where the RegNC failed. Several complex techniques for the management of these anatomies have been described,21 but they increase procedural time and cost. Eddin et al.22 determined that tortuosity and angulation were the main predictors for the use of a guide catheter extension system. Also, angulations > 45° proximal to the lesion predict its use with a 73% sensitivity and a 74% specificity. In different series, tortuosity and angulation justify the use of a guide catheter extension system in 22% to 43% of the cases.18 Despite the significant tortuosity and angulation of our series, the need for a guide catheter extension system or any other kind of complex technique to advance the SphNC was low (< 8% and 10% respectively), which is why this device emerges as a useful tool in the coronary tortuosity setting with potential to reduce procedural costs.

The study design was moderately ambitious since we hypothesized that if the SphNC were successful in 1 out of 3 lesions where the RegNC had failed this outcome would have been good enough for the new device. The fact that it exceeded the success rate of 30% proposed in the hypothesis makes us think of the results as positive. To better understand these outcomes, 5 videos have been provided as supplementary data including examples of failed RegNCs and succesful SphNCs in the same lesion.

Limitations

Despite its prospective design, the study has several limitations. The indication of postdilatation with SphNC based only on the operator’s criterion may have conditioned selection biases, thus preventing the inclusion of very unfavorable lesions. The study design does not allow us to assess the superiority of the SphNC over the RegNC regarding the lower need for complex techniques, mechanical stent failure or better angiographic and procedural outcomes. The use of intracoronary imaging was low, and a more comprehensive assessment of stent expansion with imaging techniques could have changed the data of the PCI final outcomes and, consequently, the secondary endpoints. The SphNC recrossing after first inflation was anecdotal and is, therefore, ill-advised. We should mention that our results cannot be extrapolated to coronary predilatation because the device has not been tested prior to stenting. Finally, the lack of follow-up to monitor the patients’ clinical course does not allow us to assess the clinical impact derived from the use of SphNC.

CONCLUSIONS

Coronary postdilatation with the SphNC during PCI in the routine clinical practice has a very high rate of technical success both as first choice (98.9%), and in cases of failed RegNC advancement (98.8%) with a lower need for complex techniques, and a good safety profile.

FUNDING

RECONQUISTHA is an investigator-initiated trial promoted and developed by Fundación EPIC, Spain as the clinical research organization sponsored by IZASA Medical, Spain. All the authors received research grants for their participation in the study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J. A. Linares Vicente: design, data curation, analysis, and interpretation, and manuscript drafting. A. Pérez de Prado, and J. R. Rumoroso Cuevas: design, data curation, manuscript drafting, and critical review of its content. K. García San Román, F. Lozano Ruiz-Póveda, G. Veiga Fernández, A. Gómez Menchero, G. Moreno Terribas, G. Miñana Escrivà, J. Sánchez Gila, C. Arellano Serrano, G. Martín Cáceres, P. Bazal Chacón, P. Martín Lorenzo, F. Rebollal Leal, and J. Moreu Burgos: data curation, critical review of the content of the manuscript, and final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Pérez de Prado is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. J. A. Linares has received lecture fees from IZASA Medical, Spain.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Coronary stent postdilatation with NC balloons is associated with better clinical outcomes. The complexity of PCIs in the routine clinical practice is on the rise. The navigability of RegNCs is limited, and their cone-shaped tip can complicate moving forward inside of the stent. Therefore, success could be limited in in complex lesions.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- In the routine clinical practice, coronary postdilatation using SphNC while performing a PCI has a very high rate of technical success even in complex clinical settings where the RegNC has failed (especially in coronary tortuosity), a lower need for complex techniques, and a good safety profile. Therefore, it could be considered as the go-to option for coronary postdilatation when performing complex PCIs.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Vídeo 1. Linares Vicente J.A. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000289

Vídeo 2. Linares Vicente J.A. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000289

Vídeo 3. Linares Vicente J.A. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000289

Vídeo 4. Linares Vicente J.A. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000289

Vídeo 5. Linares Vicente J.A. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M22000289

REFERENCES

1. Takano Y, Yeatman LA, Higgins JR, et al. Optimizing stent expansion with new stent delivery systems. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1622-1627.

2. Romagnoli E, Sangiorgi GM, Cosgrave J, Guillet E, Colombo A. Drug-Eluting Stenting. The Case for Post-Dilation. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;

1:22-31.

3. Brodie BR, Cooper C, Jones M, Fitzgerald P, Cummins F. Is adjunctive balloon postdilatation necessary after coronary stent deployment? Final results from the POSTIT trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;59:184-192.

4. Seth A, Gupta S, Singh VP, Kumar V. Expert Opinion: Optimising stent deployment in contemporary practice: The role of intracoronary imaging and non-compliant balloons. Interv Cardiol. 2017;12:81-84.

5. Pasceri V, Pelliccia F, Pristipino C, et al. Clinical effects of routine postdilatation of drug-eluting stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:898-904.

6. Mylotte D, Hovasse T, Ziani A, et al. Non-compliant balloons for final kissing inflation in coronary bifurcation lesions treated with provisional side branch stenting: A pilot study. EuroIntervention. 2012;7:1162-1169.

7. Park TK, Lee JH, Song YB, et al. Impact of non-compliant balloons on long-term clinical outcomes in coronary bifurcation lesions: Results from the COBIS (COronary BIfurcation Stent) II registry. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:456-464.

8. Moreno R, Ojeda S, Romaguera R, et al. Actualización de las recomendaciones sobre requisitos y equipamiento en cardiología intervencionista. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:33-44.

9. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Circulation. 2018;137:2635-2650.

10. Secco GG, Buettner A, Parisi R, et al. Clinical Experience with Very High-Pressure Dilatation for Resistant Coronary Lesions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20:1083-1087.

11. Ryan TJ, Faxon DP, Gunnar RM, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Assessment of Diagnostic and Therapeutic Cardiovascular Procedures (Subcommittee on Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty). Circulation. 1988;78:486-502.

12. Madhavan MV, Tarigopula M, Mintz GS, Maehara A, Stone GW, Généreux P. Coronary Artery Calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1703-1714.

13. Jakob M, Spasojevic D, Krogmann ON, Wiher H, Hug R, Hess OM. Tortuosity of coronary arteries in chronic pressure and volume overload. Cathet Cardiovasc Diag. 1996;38:25-31.

14. Ellis SG, Vandormael MG, Cowley MJ, et al. Coronary morphologic and clinical determinants of procedural outcome with angioplasty for multivessel coronary disease. Implications for patient selection. Multivessel Angioplasty Prognosis Study Group. Circulation. 1990;82:1193-1202.

15. Moushmoush B, Kramer B, Hsieh AM, Klein LW. Does the AHA/ACC task force grading system predict outcome in multivessel coronary angioplasty? Cathet Cardiovasc Diag. 1992;27:97-105.

16. Wang B, Mintz GS, Witzenbichler B, et al. Predictors and Long‐Term Clinical Impact of Acute Stent Malapposition: An Assessment of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy With Drug‐Eluting Stents (ADAPT‐DES) Intravascular Ultrasound Substudy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e004438.

17. Komaki S, Ishii M, Ikebe S, et al. Association between coronary artery calcium score and stent expansion in percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2021;334:31-36.

18. Fabris E, Kennedy MW, di Mario C, et al. Guide extension, unmissable tool in the armamentarium of modern interventional cardiology. A comprehensive review. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:141-147.

19. Arnous S, Shakhshir N, Wiper A, et al. Incidence and mechanisms of longitudinal stent deformation associated with Biomatrix, Resolute, Element, and Xience stents: Angiographic and case-by-case review of 1,800 PCIs. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:1002-11.

20. Ellis SG, Topol EJ. Results of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty of high-risk angulated stenoses. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66:932-7.

21. Saeed B, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Tortuous Coronary Arteries: Associated Complications and Strategies to Improve Success. J Interv Cardiol. 2008;21:504-511.

22. Eddin MJ, Armstrong EJ, Javed U, Rogers JH. Transradial interventions with the GuideLiner catheter: Role of proximal vessel angulation. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2013;14:275-279.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Systemic coronary artery embolism is one of the mechanisms of acute myocardial infarction of nonatherosclerotic origin. However, the epidemiological, clinical, and angiographic profile of this entity has not been properly established yet. Our objective was to describe the clinical characteristics, angiographic features, and prognosis of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) due to systemic embolism (ACS-E), compare them to those due to coronary atherosclerosis (ACS-A), and identify predictive clinical factors of ACS-E.

Methods: All consecutive patients with ACS—admitted to a tertiary hospital from 2003 through 2018—were classified as ACS-E (n = 40) or ACS-A (n = 4989), and prospectively recruited on a multipurpose database.

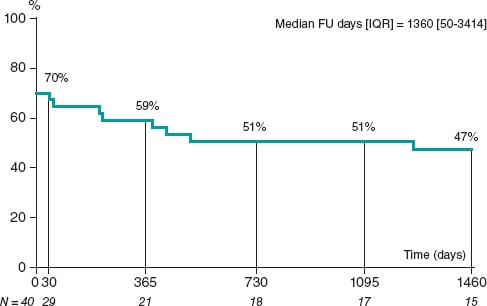

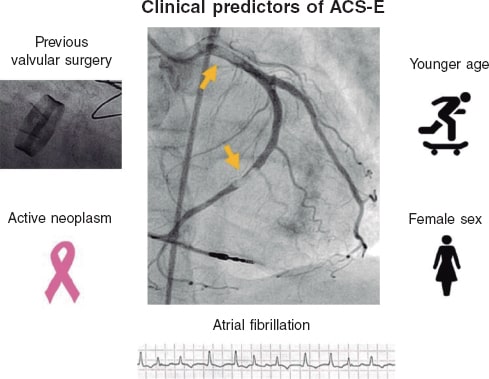

Results: Patients with ACS-E were younger (27.5% vs 9.6% were < 45 years old, P < .001), more often women (42.5% vs 22.5%, P = .003), and had higher rates of atrial fibrillation (AF) (40.0% vs 5.3%, P < .001), previous stroke (15.0% vs 3.6%, P < .001), active neoplasms (17.5% vs 6.9%, P =.009), and previous valvular surgery (12.5% vs 0.5%, P < .001). Also, a higher proportion of them were on warfarin (27.5% vs 2.9%, P < .001). The most frequent culprit vessel was the left anterior descending coronary artery in both groups. A percutaneous coronary intervention was attempted in all patients with ACS-A, and in 75.0% of those with ACS-E (P < .001) being successful in 99.1% and 80.0%, respectively. The in-hospital all-cause mortality rate was 15.0% regarding ACS-E, and 4.0% in the control group (P < .001). A multivariate analysis was performed to study the independent predictors of ACS-E, identify AF, previous valvular surgery, and active neoplasms, younger age, and female sex.

Conclusions: ACS-E and ACS-A have different clinical and angiographic characteristics. Atrial fibrillation, previous valvular surgery, active neoplasms, younger age, and female sex were all independent predictors of ACS-E.

Keywords: Coronary artery embolism. Atrial fibrillation. Acute coronary syndrome. Myocardial infarction.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La embolia coronaria de origen sistémico representa uno de los mecanismos de infarto agudo de miocardio de causa no aterosclerótica. Sin embargo, el perfil epidemiológico, clínico y angiográfico de esta entidad no ha sido aún bien definido. Nuestro objetivo fue describir las características clínicas y angiográficas y el pronóstico de los síndromes coronarios agudos (SCA) de origen embólico (SCA-E), compararlos con aquellos debidos a aterosclerosis (SCA-A) e identificar predictores clínicos de SCA-E.

Métodos: Todos los pacientes con SCA atendidos en un hospital terciario entre 2003 y 2018 se clasificaron en SCA-E (n = 40) o SCA-A (n = 4.989) e incluidos de forma prospectiva en un registro multipropósito.

Resultados: Entre los pacientes con SCA-E existía mayor proporción de jóvenes (27,5 frente a 9,6% tenían menos de 45 años, p < 0,001), mujeres (42,5 frente a 22,5%, p = 0,003), fibrilación auricular (FA) (40,0 frente a 5,3%, p < 0,001), neoplasias activas (17,5 frente a 6,9%, p = 0,009), cirugía valvular previa (12,5 frente a 0,5%, p < 0,001) y una mayor proporción de los mismos se encontraba en tratamiento con warfarina (27,5 frente a 2,9%, p < 0,001). El vaso responsable con mayor frecuencia fue la descendente anterior en ambos grupos. En todos los pacientes con SCA-A se llevó a cabo una intervención coronaria percutánea, frente al 75,0% de los pacientes con SCA-E (p < 0,001), la cual se completó con éxito en el 99,1% y el 80,0% de los casos, respectivamente. La mortalidad por todas las causas en el grupo de SCA-E fue del 15,0% frente al 4,0% en el grupo control (p < 0,001). Se llevó a cabo un análisis multivariante para estudiar predictores independientes de SCA-E, identificando la FA, la cirugía valvular previa, la presencia de una neoplasia activa, una menor edad y el sexo femenino.

Conclusiones: Los SCA-E y los SCA-A presentan características clínicas y angiográficas diferentes. La FA, la cirugía valvular previa, la presencia de una neoplasia activa, ser más joven y el sexo femenino son predictores independientes de SCA-E.

Palabras clave: Embolia coronaria. Fibrilacion auricular. Sindrome coronario agudo. Infarto de miocardio.

Abbreviations

ACS: acute coronary syndrome. ACS-A: acute coronary syndrome due to atherosclerosis. ACS-E: acute coronary syndrome due to systemic embolism. AF: atrial fibrillation. AMI: acute myocardial infarction. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

INTRODUCTION

Systemic coronary artery embolism is one of the mechanisms of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) of non-atherosclerotic origin and represents 3% to 14% of all acute coronary syndromes (ACS) reported, according to angiographic and autopsy studies. However, the real prevalence of this entity remains unknown due to the uncertainty of its diagnosis in the acute setting.1,2

Atrial fibrillation (AF), cardiomyopathies, valvular heart disease, malignancies, and infective endocarditis have previously been associated with ACS due to systemic embolism (ACS-E).1,3 Nevertheless, the epidemiological, clinical, and angiographic profile of this entity has not been properly established yet.

Our objective was to describe the clinical characteristics, angiographic features, therapeutic management, and prognosis of ACS-E, compare it to ACS due to coronary atherosclerosis (ACS-A), and identify predictive clinical factors of ACS-E.

METHODS

Study population

All consecutive patients with ACS—admitted to a tertiary hospital from January 2003 through December 2018—were evaluated, classified as ACS-E or ACS-A, and prospectively recruited on a multipurpose database. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee (internal code 22/137-E), and patients’ informed consent was waived because it involved only the analysis of data obtained during standard clinical practice.

AMI was defined as elevated cardiac troponin levels (myocardial injury) with clinical evidence of acute myocardial ischemia including symptoms, new ischemic electrocardiographic changes, development of pathological Q waves on the electrocardiogram, new regional wall motion abnormalities in a pattern consistent with ischemic aetiology, and/or angiographic identification of a coronary thrombus.4 All patients underwent a thorough diagnostic work-up including detailed clinical histories and physical examinations, serial electrocardiograms, blood tests, transthoracic echocardiographies, and invasive coronary angiographies. Intracoronary imaging techniques like optical coherence tomography or intravascular ultrasound were left to the operator’s discretion.

Diagnosis of ACS-E was achieved according to the angiographic evidence of coronary artery thrombosis without atherosclerotic components, concomitant multi-site coronary artery embolism or concomitant systemic embolization excluding left ventricular thrombus due to AMI.1 Only emboli of principal coronary arteries were considered. Patients with the following angiographic findings were systematically excluded: a) presence of atherosclerosis at culprit lesion level, b) evidence of > 25% coronary artery stenosis outside the culprit lesion, c) plaque rupture or coronary erosion at culprit lesion level found on the intravascular imaging, d) coronary artery ectasia, and e) other causes of non-atherosclerotic AMI (vasospasm, spontaneous coronary artery dissection).

Angiographic evaluation of the culprit site was performed by 2 expert operators with an intention to rule out a) the presence of thrombus (defined as noncalcified filling defect outlined by contrast media), b) presence of angiographic stenosis, and c) signs of atherosclerosis (eg, vessel wall calcification). The rest of the angiogram was assessed looking for angiographic stenosis or atherosclerosis.

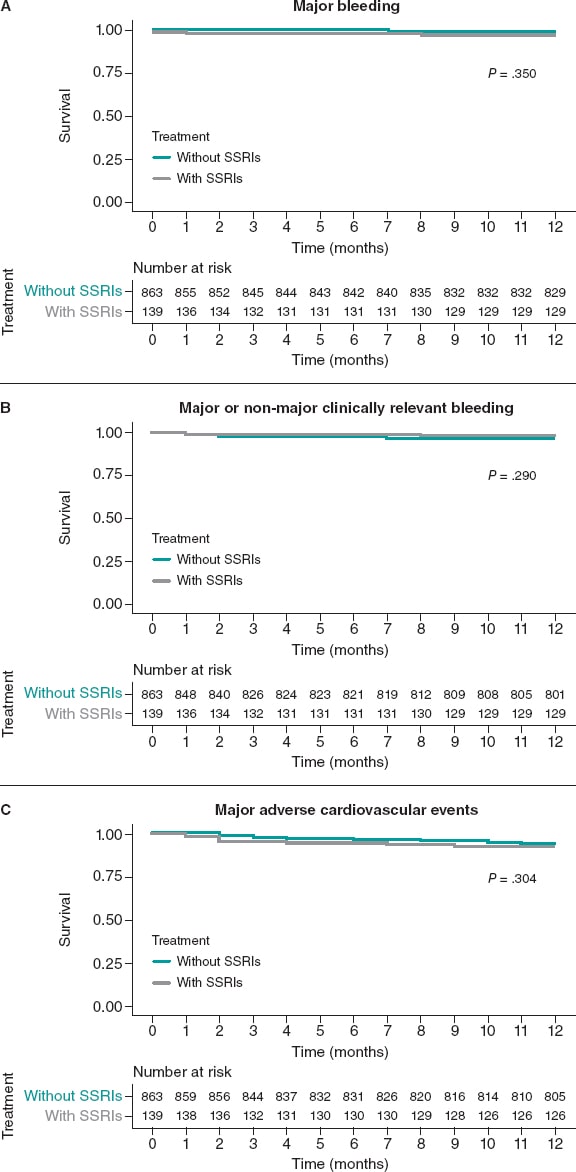

Clinical events

Epidemiological data, clinical features, angiographic characteristics, management, and outcomes were prospectively collected as patients were recruited and retrospectively analysed. The long-term follow-up of ACS-E was performed by monitoring any recurrences of systemic emboli (including cardiogenic stroke), and the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events including cardiac death, myocardial infarction, new percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), hospitalization due to heart failure or stroke more than 30 days after admission due to ACS-E.

In the present study, we first performed a detailed description of the episodes of ACS-E followed by a comparison to ACS-A to identify clinical peculiarities, and predictors.

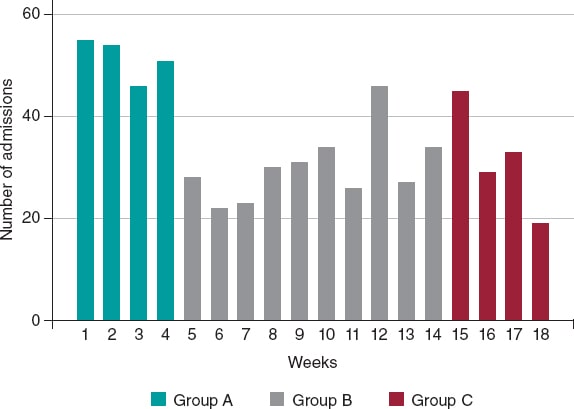

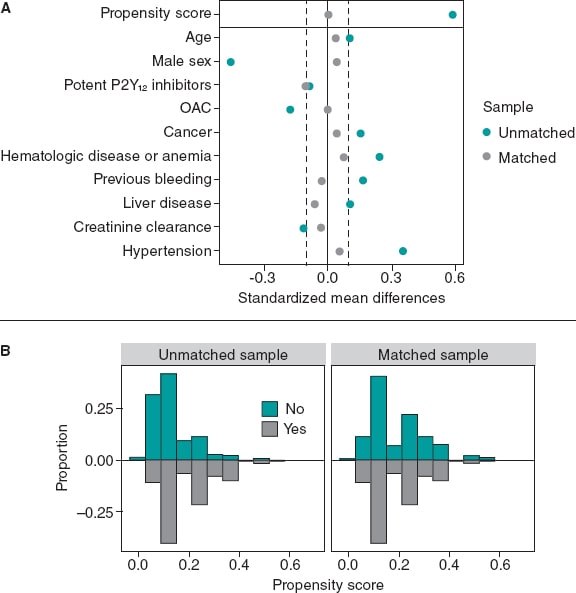

Statistical analysis