Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Delayed vascular healing may induce late stent thrombosis. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is useful to evaluate endothelial coverage. The objective of this study was to compare stent coverage and apposition in non-complex coronary artery lesions treated with durable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stents (durable-polymer EES) vs biodegradable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stents (biodegradable-polymer EES) vs polymer-free biolimus-eluting stents (BES) 1 and 6 months after stent implantation.

Methods: Prospective, multicenter, non-randomized study that compared the 3 types of DES. Follow-up angiography and OCT were performed 1 and 6 months later. The primary endpoint was the rate of uncovered struts as assessed by the OCT at 1 month.

Results: A total of 104 patients with de novo non-complex coronary artery lesions were enrolled. A total of 44 patients were treated with polymer-free BES, 35 with biodegradable-polymer EES, and 25 with durable-polymer EES. A high rate of uncovered struts was found at 1 month with no significant differences reported among the stents (80.2%, polymer-free BES; 88.1%, biodegradable-polymer EES; 82.5%, durable-polymer EES; P = .209). Coverage improved after 6 months in the 3 groups without significant differences being reported (97%, 95%, and 93.7%, respectively; P = .172).

Conclusions: In patients with de novo non-complex coronary artery lesions treated with durable vs biodegradable vs polymer-free DES, strut coverage and apposition were suboptimal at 1 month with significant improvement at 6 months.

Keywords: Optical coherence tomography. Drug-eluting stents. Endothelization. Apposition. Restenosis.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: A pesar del desarrollo de los stents farmacoactivos, el retraso en la endotelización puede causar trombosis tardía. La tomografía de coherencia óptica puede evaluar la cobertura intimal. El objetivo de este estudio fue comparar la cobertura y la aposición en lesiones coronarias no complejas de 3 tipos de stent: stent de everolimus con polímero persistente, stent de everolimus con polímero bioabsorbible y stent de biolimus sin polímero, a 1 y 6 meses del implante.

Métodos: Se diseñó un estudio prospectivo, multicéntrico, no aleatorizado, que comparó 3 stents farmacoactivos. Se realizaron angiografía y tomografía de coherencia óptica a 1 o 6 meses. El objetivo primario fue comparar la cobertura.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 104 pacientes con lesiones coronarias de novo no complejas. Se implantó stent sin polímero a 44 pacientes, stent con polímero bioabsorbible a 35 pacientes y stent con polímero persistente a 25 pacientes. Al mes, se observó una alta tasa de struts no cubiertos, sin diferencias significativas entre los grupos (80,2% sin polímero, 88,1% con polímero bioabsorbible y 82,5% con polímero persistente; p = 0,209). La cobertura mejoró a los 6 meses en los 3 stents, sin diferencias significativas entre ellos (97, 95 y 93,7%, respectivamente; p = 0,172).

Conclusiones: En los pacientes con lesiones coronarias no complejas tratados con stent con polímero persistente, con polímero bioabsorbible o sin polímero, la cobertura y la aposición fueron subóptimas a 1 mes del implante, con mejoría significativa a los 6 meses.

Palabras clave: Tomografía de coherencia óptica. Stent farmacoactivo. Endotelización. Aposición. Reestenosis.

Abbreviations

DAPT: dual antiplatelet therapy. DES: drug-eluting stents. OCT: optical coherence tomography. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. QCA: quantitative coronary angiography.

INTRODUCTION

Uncovered stent struts is one of the key predictors of stent thrombosis,1,2 and dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) has shown to reduce its risk.3 However, DAPT increases the risk of hemorrhage, and nearly one third of the patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) are considered at high bleeding risk. Given the desire for earlier discontinuation of DAPT to reduce the risk of bleeding complications, healing of the stents at earlier time points is desirable.

Drug-eluting stents (DES) significantly reduce neointimal hyperplasia and restenosis compared to bare-metal stents (BMS). However, the main concern regarding first-generation DES was late stent thrombosis due to lack of endothelization of stent struts.1 Therefore, a new generation of DES was developed based on improved thinner metal platforms, new drugs (alternative antiproliferative -limus analogues),4-6 and more biocompatible polymers.7 The evolution of DES moved towards DES with biodegradable polymers.8-10 The comparative studies between DES with biodegradable polymers and BMS showed a lower rate of cardiac death, target vessel-related myocardial reinfarction, and revascularization at 1 year.10 Compared to biodegradable polymer DES, those with durable polymer were noninferior regarding acute coronary syndromes with respect to all-cause mortality, nonfatal myocardial infarction, and revascularization.11 Furthermore, the most recent advance to overcome stent thrombosis has been the polymer-free DES. This type of DES was initially designed to reduce the risk of stent thrombosis in patients with high bleeding risk who could only take short courses of DAPT. It was compared to BMS showing a better efficacy and safety profile.13 It has recently been compared to DES in large clinical trials, especially in patients with high bleeding risk and need for shorter DAPT courses. In these studies, the use of polymer-based zotarolimus-eluting stent was noninferior to polymer-free DES14, and non-measurable differences in device-oriented composite primary endpoints were found.15

However, despite these large clinical trials, there is scarce information on the difference between the characteristics of arterial healing among different types of latest generation DES. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a widely used high-resolution intracoronary imaging modality to assess vascular response after stent implantation, thus detecting stent strut coverage and its apposition to the vessel wall.16,17 Stent strut coverage as studied by the OCT is considered a valuable surrogate marker for vessel healing after DES implantation.

The objective of this study was to compare durable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stents (durable-polymer EES) vs biodegradable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stents (biodegradable-polymer EES) vs polymer-free BES using stent strut coverage as assessed by the optical coherence tomography (OCT) as a surrogate marker to evaluate short-term arterial healing.

METHODS

Patient population and data collection

This was a prospective, multicenter, non-randomized study that compared 3 different types of DES: a) the durable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stent Xience DES (Abbott, United States); b) the biodegradable polymer-coated everolimus-eluting stent Synergy DES (Boston Scientific, United States), and c) the polymer-free BES Biofreedom DES (Biosensors International Ltd, Singapore). The study was conducted at 4 Spanish teaching hospitals.

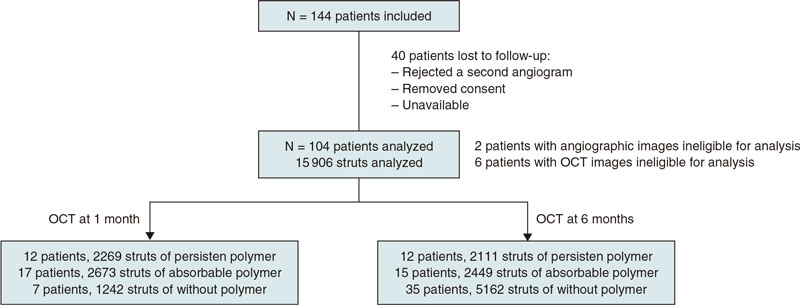

A total of 144 patients were consecutively recruited from January 2018 through December 2019. Patients were eligible if they had been admitted due to stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndrome without cardiogenic shock. The medical team selected the type of stent that should be implanted. The detailed study flowchart is shown on figure 1. Inclusion criteria were a) de novo lesions; b) ≥ 1 target lesions in the same or different coronary artery; c) no need for stent overlapping, and a 10 mm minimal distance between the stents; d) stent length between 8 mm and 30 mm; e) use of stents with diameters ≥ 2.5 mm.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient inclusion.

Exclusion criteria were a) complex lesions including ostial lesions, chronic total coronary occlusions, calcified lesions requiring calcium modification techniques, and bifurcations requiring the kissing balloon technique; b) target lesions in small vessels (< 2.5 mm) and long lesions (> 30 mm) requiring small diameter stents (2.25 mm) or overlapping stents; c) diabetic patients; d) very tortuous arteries that anticipated the impossibility of access with the OCT catheter for follow-up purposes; and e) complications during index procedure. Patients with diabetes mellitus were excluded from the study because of their pro-inflammatory status that facilitates both stent thrombosis and restenosis.18

Once recruited, patients were consecutively assigned to a 1- or 6-month OCT follow-up group. The baseline characteristics, angiographic and procedural data, follow-up data, and outcome data were prospectively collected by the study coordinators. Clinical data at follow-up were obtained from the clinical records. This study was performed following the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki, ISO14155, and the clinical practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) and the hospital research committee. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Percutaneous coronary intervention, angiographic analysis, and optical coherence tomography

In the index procedure stents were implanted according to the standard approach. Patients were medically treated following the European guidelines on the management of chronic ischemic heart disease or acute coronary syndrome.19

Regarding the initial angiographic analysis, 2 orthogonal projections without coronary guidewire were obtained after finishing the index procedure. These same projections were acquired at follow-up. The off-line analysis of the angiographic images (quantitative coronary angiography [QCA]) was performed in an independent core lab (Barcelona Cardiac Imaging Core-Lab [BARCICORElab]), following their standard protocol. They used a dedicated software (CAAS, version 5.9; Pie Medical BV, The Netherlands). Methods used in this core lab have been previously reported20.

The follow-up angiography was performed at 1-or-6-month follow-up. Angiographic and OCT images were obtained from each patient. The Dragonfly frequency domain OCT C7-XR system (St. Jude Medical, United States) was used. This analysis was performed at the same independent core lab with a dedicated software (St. Jude Medical). Further information can be found on the supplementary data. The struts were classified as non-covered if their surface was totally or partially exposed to the lumen, and without any tissue coverage above its high-density scaffold. Stent strut apposition was defined as the perpendicular distance between the luminal edge of the strut and the vascular wall. Incomplete apposition was considered when distance was higher compared to the total strut thickness considering the addition of strut plus polymer. Intimal hyperplasia was measured as the perpendicular distance between the luminal surface of the stent strut and the luminal surface of the neointima.

Endpoints

The study primary endpoint was the percentage of uncovered struts among durable-polymer EES vs biodegradable-polymer EES vs polymer-free BES as seen on the OCT at 1 month.

The study secondary endpoint was to compare the coverage and apposition of these 3 different types of DES on the OCT 1 vs 6 months after implantation. In addition, we evaluated the intimal hyperplasia in the 3 stent groups over time.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation except when they did not follow normal distribution, in which case they were expressed as median and 25th-75th percentile. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage. The analysis of the clinical differences was performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables. Comparison among quantitative variables was performed using the 1-way ANOVA test. Generalized estimating equations, considering the clustering nature of the OCT data, were used to conduct analyses at strut level. All probability values were two-sided, P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package, version 22.0 (SPSS, United States). The sample size estimate is shown on the supplementary data.

RESULTS

Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 104 patients from 4 different hospitals were included in the study; 44 patients were treated with a polymer-free BES, 35 with a biodegradable-polymer EES, and 25 patients with a durable-polymer EES. Of these, 37 patients underwent follow-up angiography and OCT 1 month after DES implantation, and 67 patients after 6 months. Mean age was 57 years; most patients were man (11% women). The inter-group baseline clinical characteristics are shown on table 1 according to the type of stent implanted. We observed a statistically significant difference in the left ventricular ejection fraction that was slightly lower in patients who received a polymer-free BES (54% vs 60%). The number of patients who needed postdilatation was higher in the durable-polymer EES group (68%) especially compared to the polymer-free BES group (38%).

Table 1. Baseline clinical, lesion, and procedural characteristics

| Polymer-free BES (N = 44) |

Biodegradable-polymer EES (N = 35) |

Durable-polymer EES (N = 25) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 57 ± 8 | 61 ± 9 | 59 ± 10 | .094 |

| Women | 3 (7) | 4 (11) | 4 (16) | .482 |

| Dyslipidemia | 24 (55) | 19 (54) | 14 (56) | .990 |

| Hypertension | 17 (39) | 14 (40) | 13 (52) | .527 |

| Family history of ischemic heart disease | 10 (23) | 4 (11) | 6 (24) | .353 |

| Smoker | 26 (59) | 13 (37) | 9 (36) | .076 |

| LVEF % | 54 ± 9 | 60 ± 9 | 60 ± 8 | .006 |

| Chronic kidney disease (creatinine > 1.5 mg/dL) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | .370 |

| Previous MI | 2 (5) | 7 (20) | 4 (12) | .102 |

| Previous PCI | 2 (5) | 6 (17) | 4 (16) | .159 |

| Previous CABG | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | .526 |

| Target lesion location | .101 | |||

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 18 (41) | 10 (29) | 11 (44) | |

| Left circumflex artery | 10 (23) | 8 (23) | 19 (40) | |

| Right coronary artery | 15 (34) | 13 (37) | 4 (16) | |

| Secondary artery (diagonal, posterolateral, posterior descending) | 1 (2) | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Stent length, mm | 18.6 ± 5 | 18.8 ± 6 | 19.5 ± 6 | .769 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 3.1 ± 0.5 | 3.1 ± 0.4 | .053 |

| Predilatation, % | 19 (43) | 16 (73) | 13 (53) | .076 |

| Postdilatation, % | 16 (38) | 12 (57) | 17 (68) | .05 |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

||||

Procedural and lesion characteristics

Procedural characteristics based on the type of stent implanted are shown on table 1. We found no significant differences in stent diameter or length in the 3 stent groups. The left anterior descending coronary artery was the most treated of all whereas secondary arteries were scarcely included in this study.

Angiographic analysis

The lesion angiographic characteristics are shown on table 2 and table 1 of the supplementary data. There were 2 patients with angiographic images with insufficient quality for analysis, both from the biodegradable-polymer EES group. There were no significant differences in the lesions before or after the PCI. After 1 month, no significant differences were reported regarding lumen loss or percent diameter stenosis. No differences were reported among the 3 stent groups at 6 months.

Table 2. Angiographic analysis

| Polymer-free BES (N = 44) | Biodegradable-polymer EES (N = 35) | Durable-polymer EES (N = 25) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-month follow-up | (N = 7) | (N = 16) | (N = 12) | |

| Stent length, mm | 17.85 ± 4.32 | 19.24 ± 5.63 | 19.39 ± 4.41 | .788 |

| Reference lumen diameter, mm | 2.93 ± 0.60 | 2.80 ± 0.53 | 2.77 ± 0.55 | .827 |

| Minimal lumen diameter, mm | 2.75 ± 0.46 | 2.65 ± 0.50 | 2.51 ± 0.49 | .586 |

| Late lumen loss, mm | 0.03 ± 0.09 | 0.04 ± 0.10 | 0.03 ± 0.08 | .965 |

| Percentage diameter stenosis, % | 5.57 ± 6.27 | 6.50 ± 7.14 | 8.67 ± 9.27 | .658 |

| 6-month follow-up | (n = 37) | (n = 17) | (n = 13) | |

| Stent length, mm | 18.99 ± 4.92 | 20.03 ± 6.55 | 18.13 ± 4.95 | .627 |

| Reference lumen diameter, mm | 2.75 ± 0.57 | 2.79 ± 0.50 | 2.65 ± 0.34 | .757 |

| Minimal lumen diameter, mm | 2.54 ± 0.45 | 2.34 ± 0.41 | 2.39 ± 0.37 | .213 |

| Late lumen loss, mm | 0.19 ± 0.25 | 0.28 ± 0.24 | 0.20 ± 0.18 | .368 |

| Percentage diameter stenosis, % | 5.77 ± 15.30 | 15.18 ± 12.92 | 10.08 ± 7.40 | .065 |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

||||

OCT outcomes

OCT results are shown on table 3, and table 2 in the supplementary data. There were 6 patients with OCT images with insufficient quality for analysis, 2 from the polymer-free BES, 3 from the biodegradable-polymer EES group, and 1 from the durable-polymer EES group. Stent strut coverage and apposition were analyzed, as well as neointimal hyperplasia. Overall, 15 906 struts were examined. Of these, 4380 struts were from durable-polymer EES; 5122 from biodegradable-polymer EES; and 6404 from polymer-free BES; 6184 and 9722 struts were analyzed at 1 and 6 months, respectively.

Table 3. Optical coherence tomography analysis

| Polymer-free BES | Biodegradable-polymer EES | Durable-polymer EES | Pa | Pb | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow-up | 1-month (N = 7) |

6-months (N = 35) |

P | 1-month (N = 17) |

6-months (N = 15) |

P | 1-month (N = 12) |

6-months (N = 12) |

P | ||

| Strut level analysis | (N = 1242) | (N = 5162) | (N = 2673) | (N = 2449) | (N = 2269) | (N = 2111) | |||||

| Uncovered struts, n | 238 (19.2) | 154 (3.0) | < .001 | 318 (11.9) | 123 (5.0) | .007 | 396 (17.5) | 133 (6.3) | .001 | .209 | .172 |

| Malapposed struts, n | 66 (5.3) | 13 (0.3) | < .001 | 101 (3.8) | 21(0.9) | .001 | 138 (6.1) | 35 (1.7) | .029 | .497 | .071 |

| Neointimal thickness, µm | 50.7 ± 41.9 | 138.1 ± 102.9 | < .001 | 59.9 ± 45.1 | 88.3 ± 83.9 | .005 | 48.9 ± 38.1 | 85.5 ± 68.6 | < .001 | .083 | < .001 |

|

Data are expressed as no. or mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were estimated using the chi-square test; quantitative variables were estimated with 1-way ANOVA test, and strut level analyses were conducted using generalized estimating equations considering the clustering nature of OCT data. |

|||||||||||

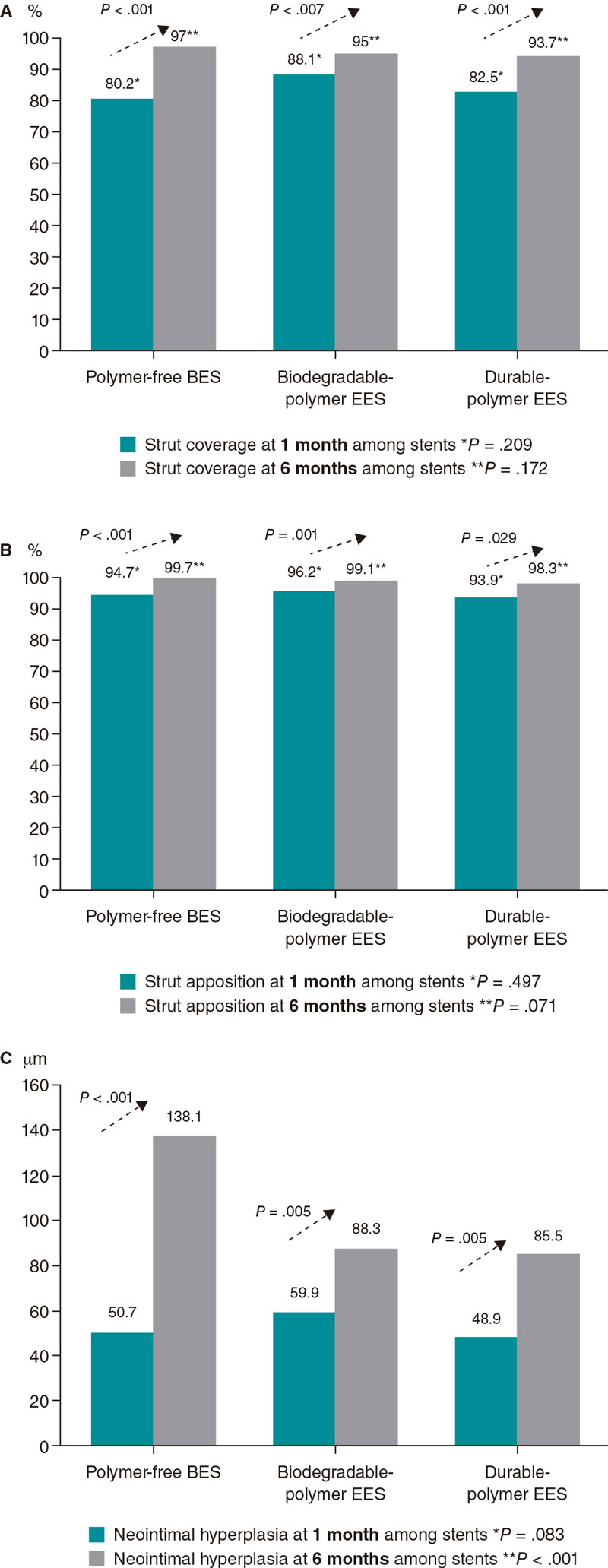

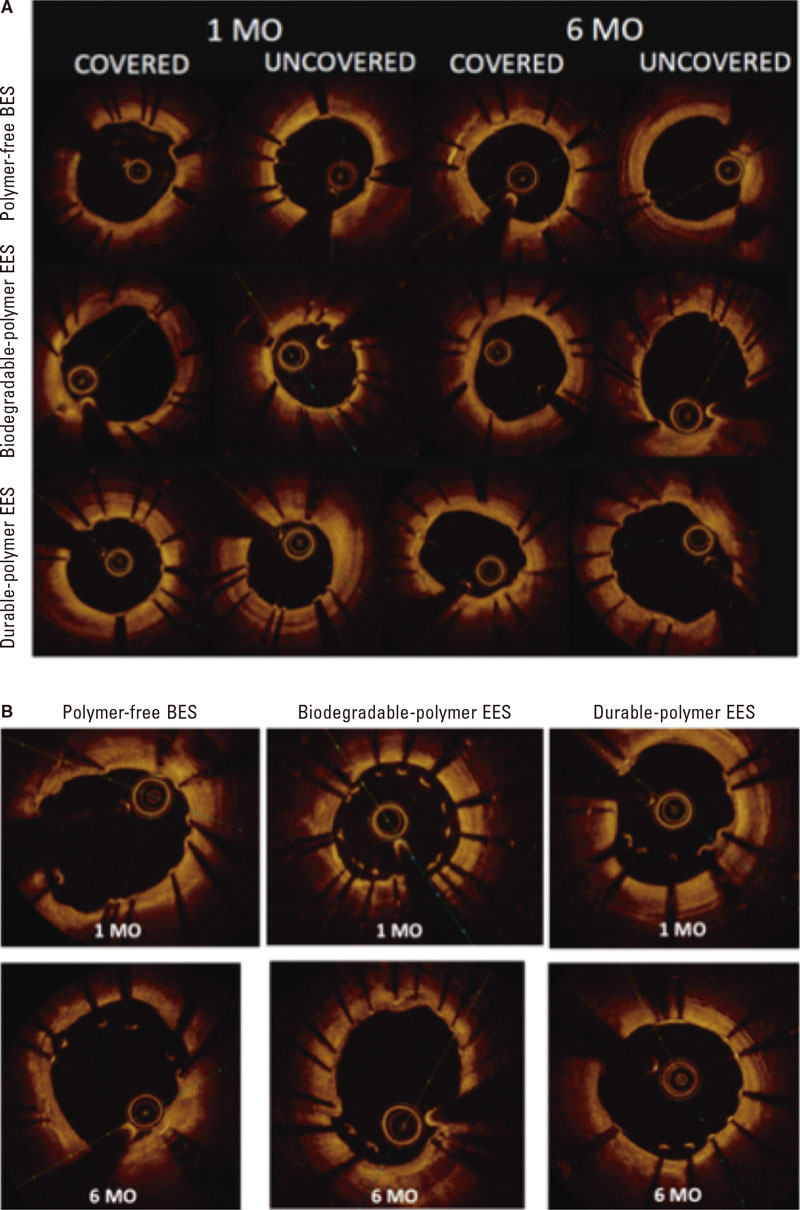

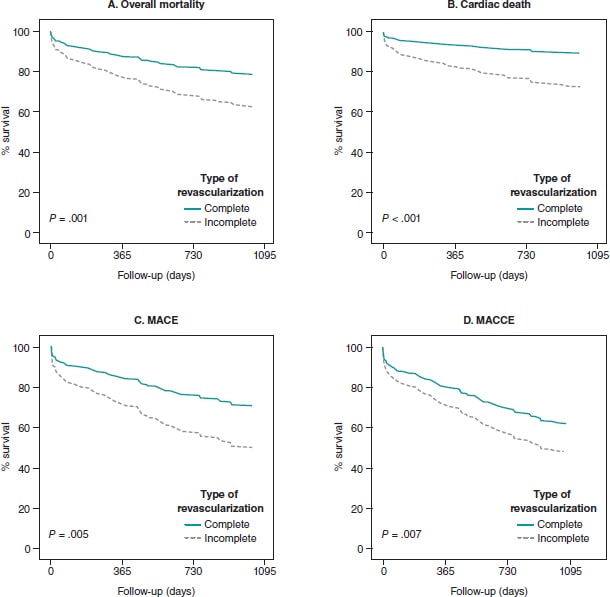

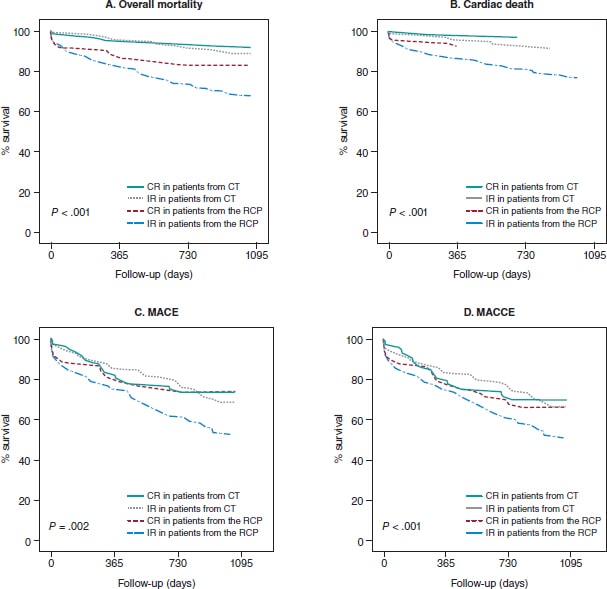

A high rate of uncovered struts was found among stents 1 month after implantation, with no significant differences (P = .209). We observed ≥ 5% of uncovered struts in > 80% of the patients. There was better coverage in the 3 stent groups at 6 months compared to 1 month (P < .001 polymer-free BES; P = .007 biodegradable-polymer EES; P = .001 durable-polymer EES). No statistically significant differences were reported in strut coverage at 6 months among the different stents (P = .172) (figure 2, figure 3A).

Figure 2. Endpoint comparison at 1 and 6 months. A: percentage of struts covered at 1 and 6 months; B: percentage of struts apposed at 1 and 6 months; C: neointimal hyperplasia at 1 and 6 months. BES, biolimus-eluting stent; EES, everolimus-eluting stent.

Figure 3. Optical coherence tomography. A: optical coherence tomography showing covered and uncovered stent struts at 1 and 6 months; B: optical coherence tomography showing malapposed stent struts at 1 and 6 months. BES, biolimus-eluting stent; EES, everolimus-eluting stent; MO, months.

Regarding strut apposition to the artery walls, no significant differences were reported among the 3 stents after 1 month (P = .497). We observed ≥ 5% of malapposed struts in 29% to 30% of the patients with no differences among stents. No significant differences were reported among the stents after 6 months either. The rate of apposition was higher at 6 months compared to 1 month in all stent groups (P < .001 polymer-free BES; P = .001 biodegradable-polymer EES; P = .029 durable-polymer EES) (figure 2, figure 3B).

When we analyzed neointimal hyperplasia, no significant differences were found at 1 month among the 3 stent groups (P = .083). At 6 months, we found higher hyperplasia in the polymer-free BES compared to the durable-polymer EES (P < .001). We found more hyperplasia at 6 months compared to 1 month in all groups (P < .001 polymer-free BES; P < .001 biodegradable-polymer EES; P = .005 durable-polymer EES; figure 2).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this prospective multicenter registry are: a) in non-diabetic patients with de novo non-complex coronary lesions treated with durable vs biodegradable vs polymer-free DES, strut coverage was similar and low (≥ 5% of uncovered struts in > 80% of patients) at 1 month; b) there was a similar high rate of malapposed stent struts (4% to 6%) at 1 month; c) intimal coverage and apposition improved significantly at 6 months; d) polymer-free BES had higher intimal hyperplasia at 6 months.

OCT findings suggest that, in non-diabetic patients with non-complex coronary lesions treated with 3 latest generation DES, there is a similar high rate of uncovered and malapposed struts at 1 month. It is after 6 months when we could see better coverage and apposition.

Several small-scale OCT studies have been performed to compare the coverage and apposition of stents with permanent and absorbable polymers.21-24 Conclusions of these studies differ with most of them stating that the absorbable polymer stent has better coverage than the permanent polymer, and 1 of them concluding the opposite.23 One of the studies found coverage to be sufficient after 3 months,22 whereas another stated that coverage improved at 12 months.24 In this study, we found no significant differences in stent strut coverage or apposition between permanent and absorbable polymer at 1 or 6 months on the OCT analysis (figure 2). Differences in stent strut coverage at follow-up may in part be explained by the stent platform, the polymers used to control drug release, and the antiproliferative drug itself. The stents of the study had a similar drug (-limus analogue) but different polymeric features (durable vs biodegradable vs polymer-free), and different platform thickness (the polymer-free BES had a thicker platform). Probably within the first month the drug effect is most important, and it was similar among the study stents (antiproliferative -limus analogues). However, over time (between 1 and 6 months), other stent features such as platform thickness or polymeric features might play a role that could explain the differences seen regarding coverage at 3 months in other studies.22,23

Accordingly, other studies have analyzed other types of polymer-free stents different to the one from our study.25,26 They found that coverage was achieved in a high percentage at 3 to 9 months, reaching conclusions that were similar to our study. One of the studies26 performed an OCT at 1, 3, and 9 months, demonstrating higher strut coverage over time, which is consistent with our results. Only 1 study analyzed the Biolimus A9 polymer-free stent with OCT without comparing it to other stents.27 It was a prospective single-center single-armed study that examined strut coverage of the Biolimus A9 polymer-free stent at 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 9 months. Researchers found that coverage was fast and improved over time with the stent remaining safe and effective. These results are similar to ours in the sense that coverage was significantly better at 6 months. However, we also compared polymer-free stents to other polymer-based stents, something that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been tested before.

One of the limitations of extrapolating the clinical safety of the stents and the degree of intimal coverage as seen on the OCT is that there is no consensus on the cut-off value of coverage that would allow safe discontinuation of DAPT. Few studies1,28 have tried to decide on a percentage of coverage, with the only in-vivo study estimating that > 5.9% of uncovered struts was an independent risk factor for stent thrombosis.28 However, these studies were limited in the number of patients included, and only some stents were tested. Larger studies are needed to decide on a security threshold for strut coverage that would make it safe to stop DAPT without increasing the risk of stent thrombosis. Therefore, the rate of coverage at 1 month (80% to 88%) in our study seems insufficient, reaching a very high percentage after 6 months (94% to 97%) in the 3 types of stents.

Finally, our study shows that intimal hyperplasia was significantly higher in polymer-free stents at 6 months. Polymer-free Biolimus A9 has a stainless steel and thicker platform, which has been associated with more intimal hyperplasia and in-stent restenosis in previous studies.27 The other 2 types of DES have a cobalt-chromium platform which has largely substituted stainless steel to provide sufficient strength and visibility with thinner struts of around 70-90 μm, resulting in lower rates of angiographic and clinical restenosis.29 Thus, inflammatory response to this thicker stent platform (130-140 μm) could be in part responsible for this finding.

Study limitations

This was an OCT-based study; unfortunately, it was not powered to assess clinical outcomes. Our study was non-randomized. However, we minimized the confounding factors through selected inclusion/exclusion criteria for patients and lesions (non-diabetic patients with non-complex coronary lesions). We analyzed the differences among the groups and no significant differences were found, except in the left ventricular ejection fraction, which was significantly lower in the group of polymer-free stents. It has not been described in the medical literature whether a lower left ventricular ejection fraction has any correlation with stent thrombosis. This study included selected non-diabetic patients with simple coronary artery lesions. Therefore, the conclusions cannot be extrapolated to other groups with different characteristics.

The distribution of patients who underwent the follow-up angiography in the polymer-free DES group at 1 or 6 months was uneven. More patients rejected the follow-up angiography at 1 month in the polymer-free DES group, which may account for this difference. Finally, the complexity of the analysis of 3 different groups in 2 different moments of time caused a disgregation of cases. This led to a small N in each group, with the potential biases associated.

CONCLUSIONS

In non-diabetic patients, a significantly high percentage of uncovered struts was detected at 1 month with OCT in latest generation DES regardless of the polymeric features of the stent (durable vs biodegradable vs polymer-free stent) in the non-complex coronary artery lesion setting. Our OCT findings do not support improved short-term healing characteristics of stents with biodegradable polymer or polymer-free based -limus elution compared to current generation of durable polymer DES.

FUNDING

This study received funding from Abbott Vascular and Biosensors International. Funders were not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of this article or decision to submit it for publication.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Calvo-Fernández, R. Elosua, and B. Vaquerizo designed the study. J. Gómez-Lara, Héctor Cubero-Gallego, Helena Tizón-Marcos, N. Salvatella, A. Negrete, R. Millán, J.L. Díez, J.M. de la Torre Hernández, and B. Vaquerizo participated in the recruitment of patients and database contribution. A. Calvo-Fernández, C. Ivern, A. Sánchez-Carpintero, and B. Vaquerizo managed the database. A. Calvo-Fernández, X. Durán, N. Farré, and B. Vaquerizo conducted the data analysis and statistics. A. Calvo-Fernández, R. Elosua, N. Farré, H. Cubero-Gallego, and B. Vaquerizo drafted the paper with feedback from all the authors.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.M. de la Torre Hernandez is an associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed; he has received grants and research support from Abbott Medical, Biosensors, Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen; honoraria or consultation fees from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Biotronik, Astra Zeneca, Daiichi-Sankyo. N. Salvatella has received teaching honoraria from Abbott Vascular, and consultation fees from Boston Scientific. The remaining authors declared no other competing interests.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Current DES with biodegradable polymer coating or the new polymer-free biolimus stent have been proposed as the optimal solution to the problem of delayed coronary artery healing characteristics seen with first-generation durable polymer-coated DES.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This multicenter registry compared 3 types of DES with similar drug elution (-limus analogue), but different stent polymeric features (durable vs biodegradable vs polymer free).

- Using the percentage of uncovered struts at short term assessed by optical coherence tomography as a surrogate endpoint, healing characteristics at 1 month were similar among stents and insufficient after 1 month.

- Our findings do not support a preferential use of stents with biodegradable polymer-based or polymer-free stents to reduce the time of dual antiplatelet therapy at 1 month.

REFERENCES

1. Finn AV, Joner M, Nakazawa G, et al. Pathological Correlates of Late Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis: Strut Coverage as a Marker of Endothelization. Circulation. 2007;115:2435-2441.

2. Guagliumi G, Sirbu V, Musumeci G, et al. Examination of the In Vivo Mechanisms of Late Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2012;5:12-20.

3. Magnani G, Valgimigli M. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy After Drug-eluting Stent Implantation. Interv Cardiol. 2016;11:51-53.

4. Kelly CR, Teirstein PS, Meredith IT, et al. Long-Term Safety and Efficacy of Platinum Chromium Everolimus-Eluting Stents in Coronary Artery Disease: 5-Year Results From the PLATINUM Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2017;10:2392-2400.

5. Maeng M, Tilsted HH, Jensen LO, et al. Differential clinical outcomes after 1 year versus 5 years in a randomised comparison of zotarolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting coronary stents (the SORT OUT III study): a multicentre, open-label, randomised superiority trial. Lancet. 2014;383:2047-2056.

6. Jakobsen L, Christiansen EH, Maeng M, et al. Final five-year outcomes after implantation of biodegradable polymer-coated biolimus-eluting stents versus durable polymer-coated sirolimus-eluting stents. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:1336-1344.

7. Sarno G, Lagerqyist B, Fröbert O, et al. Lower risk of stent thrombosis and restenosis with unrestricted use of ‘new-generation’ drug-eluting stents: a report from the nationwide Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). Eur Heart J. 2021;33:606-613.

8. von Birgelen C, Kok MM, van der Heijden LC, et al. Very thin strut biodegradable polymer everolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stents versus durable polymer zotarolimus-eluting stents in allcomers with coronary artery disease (BIO-RESORT): a three-arm, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2607-2617.

9. Raungaard B, Jensen LO, Tilsted HH, et al. Zotarolimus-eluting durable-polymer-coated stent versus a biolimus-eluting biodegradable-polymer-coated stent in unselected patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (SORT OUT VI): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1527-1535.

10. Jensen LO, Thayssen P, Maeng M, et al. Randomized Comparison of a Biodegradable Polymer Ultrathin Strut Sirolimus-Eluting Stent With a Biodegradable Polymer Biolimus-Eluting Stent in Patients Treated With Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;9:e003610.

11. Räber L, Kelbæk H, Ostojic M, et al. Effect of biolimus-eluting stents with biodegradable polymer vs bare-metal stents on cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction: the COMFORTABLE AMI randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;308:777-787.

12. Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al, HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS Trial Investigators. Durable Polymer Versus Biodegradable Polymer Drug-Eluting Stents After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome: The HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS Trial. Circulation. 2021;143:1081-1091.

13. Urban P, Meredith IT, Abizaid A, et al. Polymer-free Drug-Coated Coronary Stents in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2038-2047.

14. Windecker S, Latib A, Kedhi E, et al; ONYX-ONE Investigators. Polymer-based or Polymer-free Stents in Patients at High Bleeding Risk. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1208-1218.

15. Kufner S, Ernst M, Cassese S, et al; ISAR-TEST-5 Investigators. 10-Year Outcomes From a Randomized Trial of Polymer-Free Versus Durable Polymer Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:146-158.

16. Lee KS, Lee JZ, Hsu CH, et al. Temporal Trends in Strut-Level Optical Coherence Tomography Evaluation of Coronary Stent Coverage: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:1083-1093.

17. Tearney GJ, Regar E, Akasaka T, et al. Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: a report from the International Working Group for Intravascular Optical Coherence Tomography Standardization and Validation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:1058-1072.

18. Yuan, J. Xu GM. Early and Late Stent Thrombosis in Patients with Versus Without Diabetes Mellitus Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention with Drug-Eluting Stents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2018;18:483-492.

19. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

20. Gomez-Lara J, Teruel L, Homs S, et al. Lumen enlargement of the coronary segments located distal to chronic total occlusions successfully treated with drug-eluting stents at follow-up. EuroIntervention. 2014;9:1181-1188.

21. Teeuwen K, Spoormans E, Bennett J, et al. Optical coherence tomography findings: insights from the “randomised multicentre trial investigating angiographic outcomes of hybrid sirolimus-eluting stents with biodegradable polymer compared with everolimus-eluting stents with durable polymer in chronic total occlusions” (PRISON IV) trial. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:e522-e530.

22. Kretov E, Naryshkin I, Baystrukov V, et al. Three-months optical coherence tomography analysis of a biodegradable polymer, sirolimus-eluting stent. J Interv Cardiol. 2018;31:442-449.

23. Adriaenssens T, Ughi GJ, Dubois C, et al. STACCATO (Assessment of Stent sTrut Apposition and Coverage in Coronary ArTeries with Optical coherence tomography in patients with STEMI, NSTEMI and stable/unstable angina undergoing everolimus vs biolimus A9-eluting stent implantation): a randomised controlled trial. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:e1619-e1626.

24. Kim BK, Hong MK, Shin DH, et al. Optical coherence tomography analysis of strut coverage in biolimus- and sirolimus-eluting stents: 3-Month and 12-month serial follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:4617-4623.

25. Suwannasom P, Onuma Y, Benit E, et al. Evaluation of vascular healing of polymer-free sirolimus-eluting stents in native coronary artery stenosis: a serial follow-up at three and six months with optical coherence tomography imaging. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e574-e583.

26. Worthley SG, Abizaid A, Kirtane AJ, et al. First-in-Human Evaluation of a Novel Polymer-Free Drug-Filled Stent. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:147-156.

27. Lee SWL, Tam FCC, Chan KKW, et al. Establishment of healing profile and neointimal transformation in the new polymer-free biolimus A9-coated coronary stent by longitudinal sequential optical coherence tomography assessments: the EGO-BIOFREEDOM study. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:780-788.

28. Won H, Shin DH, Kim BK, et al. Optical coherence tomography derived cut-off value of uncovered stent struts to predict adverse clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29:1255-1263.

29. Pache J, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, et al. Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: Strut thickness effect on restenosis outcome (ISAR-STEREO-2) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1283-1288.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The optimal time to perform a diagnostic coronary angiography in patients admitted due to non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome (NSTEACS) and start pretreatment with dual antiplatelet therapy is controversial. Our study aims to identify the current diagnostic and therapeutic approach, and clinical progression of patients with NSTEACS in our country.

Methods: The IMPACT-TIMING-GO trial (Impact of time of intervention in patients with myocardial infarction with non-ST segment elevation. Management and outcomes) is a national, observational, prospective, and multicenter registry that will include consecutive patients from 24 Spanish centers with a clinical diagnosis of NSTEACS treated with diagnostic coronary angiography and with present unstable or causal atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. The study primary endpoint is to assess the level of compliance to clinical practice guidelines in patients admitted due to NSTEACS undergoing coronary angiography in Spain, describe the use of antithrombotic treatment prior to cardiac catheterization, and register the time elapsed until it is performed. Major adverse cardiovascular events will also be described like all-cause mortality, non-fatal myocardial infarction and non-fatal stroke, and the rate of major bleeding according to the BARC (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium) scale at 1- and 3-year follow-up.

Results: This study will provide more information on the impact of different early management strategies in patients admitted with NSTEACS in Spain, and the degree of implementation of current recommendations into the routine clinical practice. It will also provide information on these patients’ baseline and clinical characteristics.

Conclusions: This is the first prospective study conducted in Spain that will be reporting on the early therapeutic strategies—both pharmacological and interventional—implemented in our country in patients with NSTEACS after the publication of the 2020 European guidelines, and on the clinical short- and long-term outcomes of these patients.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. Acute myocardial infarction. Non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Dual antiplatelet therapy. Pretreatment. Early invasive strategy. ESC guidelines. Diabetes mellitus. Hemorrhage. Revascularization.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El momento óptimo para la realización de un cateterismo diagnóstico en pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST (SCASEST) y la necesidad de pretratamiento con doble antiagregación son motivo de controversia. Este estudio pretende conocer el abordaje diagnóstico y terapéutico actual, así como la evolución clínica de los pacientes con SCASEST en España.

Métodos: El estudio IMPACT of Time of Intervention in patients with Myocardial Infarction with Non-ST seGment elevation. ManaGement and Outcomes (IMPACT-TIMING-GO) es un registro nacional observacional, prospectivo y multicéntrico, que incluirá pacientes consecutivos con diagnóstico de SCASEST tratados con coronariografía diagnóstica y que presenten enfermedad coronaria aterosclerótica inestable o causal en 24 centros españoles. El objetivo primario del estudio es conocer el grado de cumplimiento de las recomendaciones de las guías de práctica clínica en pacientes que ingresan por SCASEST tratados con coronariografía en España, describir el uso del tratamiento antitrombótico antes del cateterismo y determinar el tiempo hasta este en la práctica clínica real. Se describirán también los eventos adversos cardiovasculares mayores: mortalidad por cualquier causa, infarto no fatal e ictus no fatal, y también la incidencia de hemorragia mayor según la escala BARC (Bleeding Academic Research Consortium) durante el seguimiento a 1 y 3 años.

Resultados: Este registro permitirá mejorar el conocimiento en relación con el abordaje terapéutico inicial en pacientes que ingresan por SCASEST en España. Contribuirá a conocer sus características basales y su evolución clínica, así como el grado de adherencia y cumplimiento de las recomendaciones de las que se dispone actualmente.

Conclusiones: Se trata del primer estudio prospectivo realizado en España que permitirá conocer las estrategias terapéuticas iniciales, tanto farmacológicas como intervencionistas, que se realizan en nuestro país en pacientes con SCASEST tras la publicación de las guías europeas de 2020, y la evolución clínica de estos pacientes a corto y largo plazo.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. Infarto agudo de miocardio. Síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST. Doble antiagregación plaquetaria. Pretratamiento. Coronariografía precoz. Guía ESC. Diabetes mellitus. Hemorragia. Revascularización.

Abbreviations

IMPACT-TIMING-GO: Impact of Time of Intervention in patients with Myocardial Infarction with non-ST segment elevation ManaGement and Outcomes. SCA: síndrome coronario agudo. SCASEST: síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST.

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of mortality in developed countries.1 The rate of acute coronary syndrome (ACS), specially non-ST-segment elevation ACS (NSTEACS), has increased over the last few years, in part, due to the ageing of the population.2-3 Given the underlying pathophysiology4 patients receive specific antithrombotic treatment, and invasive approach is used in most of the cases.1-3 The new guidelines published by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) on the management of NSTEACS1 include changes compared to the guidelines published back in 2016. The most significant ones include antithrombotic treatment, the revascularization strategy, and several controversial innovations.

In the guidelines published in 2020, early cardiac catheterization within the first 24 hours after admission was advised (level of evidence IA) in patients diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction with GRACE scores (Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events) > 140 or dynamic electrocardiographic changes suggestive of ischemia.1 Also, the previous window of recommendation of 0 to 72 hours for moderate risk patients is now gone.4 On the other hand, the systematic use of pretreatment at admission with an P2Y12 inhibitor antiplatelet drug (ticagrelor, prasugrel or clopidogrel) in patients to be treated with an early invasive strategy is now ill-advised.1

The objective of the IMPACT registry (Time of intervention in patients with myocardial infarction with non-ST segment elevation, management and outcomes [IMPACT-TIMING-GO]) is to get the big picture on the current treatment of NSTEACS, in Spain, in association with catheterization times, use of pretreatment in these patients, and describe the possible prognostic implications of the different strategies used in real life.

METHODS

Study design and population

This is an observational, prospective, multicenter, and nationwide registry that will include all consecutive patients admitted with a diagnosis of NSTEACS to the different participant centers, treated with diagnostic coronary angiography, and with unstable or causal atherosclerotic disease regardless of further treatment administered by the heart team. The baseline characteristics of the patients included, and their clinical progression regarding in-hospital events will be studied. Patients will undergo a 1-and-3-year clinical follow-up period.

This registry has been promoted by the Spanish Society of Cardiology Young Cardiologists Working Group with scientific support from the Spanish Society of Cardiology Research Agency. Also, it has been approved by different Research Ethics Committees with drugs from all the participant hospitals. Finally, it has been designed according to the STROBE checklist for observational studies.

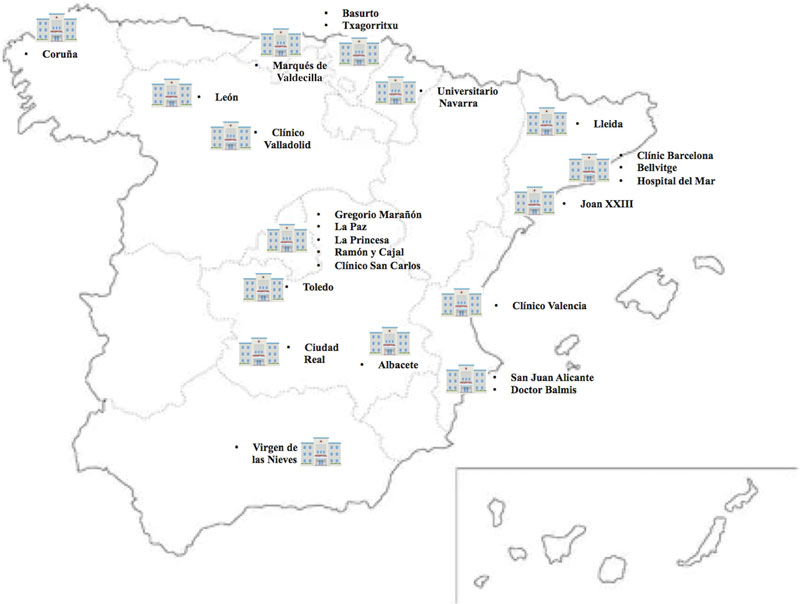

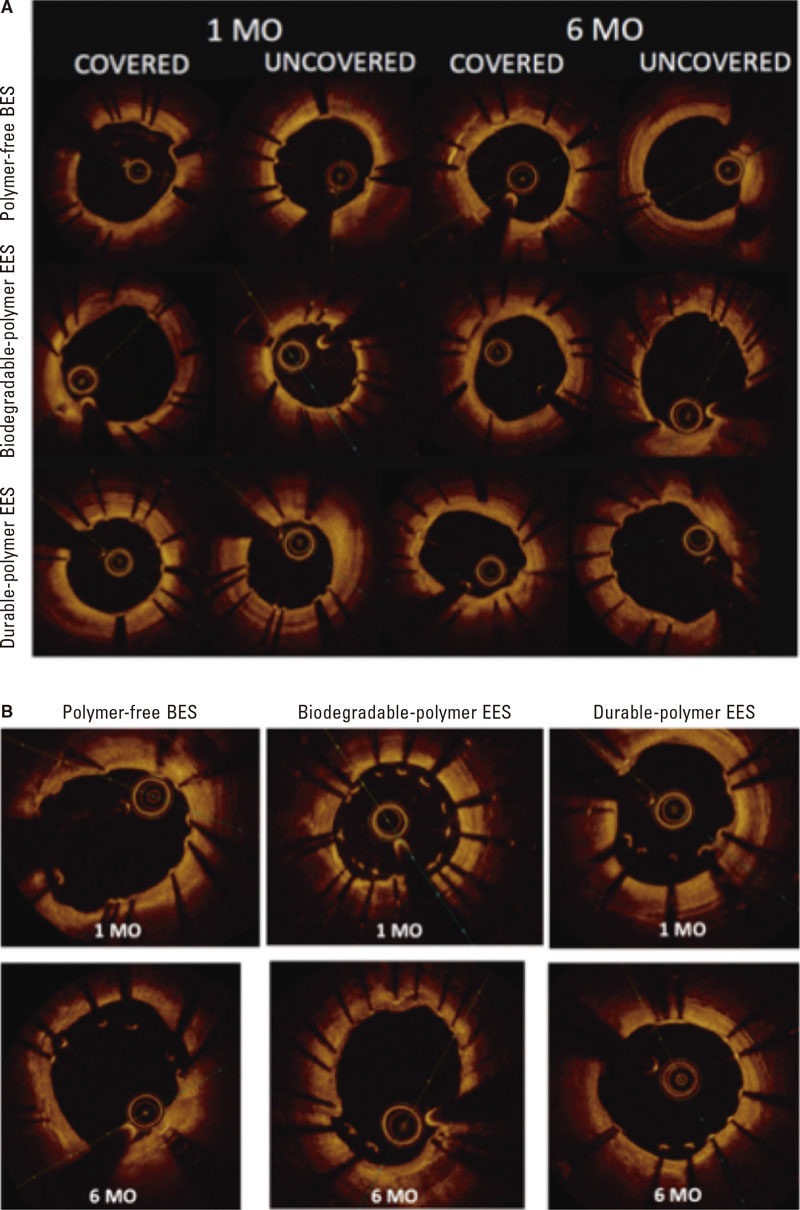

The list of centers that will eventually participate in the registry is shown on figure 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown on table 1. The presence of elevated markers of myocardial damage or electrocardiographic changes is not mandatory. Patients with a clinical diagnosis of unstable angina can be included as long as coronary angiography confirms the clinical diagnosis.

Figure 1. Map with the Spanish participant centers in the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| NSTEACS with in-hospital invasive treatment regardless of when it is performed. |

| Evidence of causal or unstable atherosclerotic disease. |

| Age ≥ 18 years. |

| Capacity to give informed consent. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Minors and those who withdraw their consent to be included or followed at any time during the study. |

| Assessment of myocardial damage markers associated with type 2 myocardial infarction. |

| Patients without any signs of coronary artery disease including those with myocarditis, Prinzmetal angina, takotsubo syndrome or MINOCA. |

| Patients diagnosed with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. |

| Patients with complete left bundle branch block or pacemaker rhythm on the electrocardiogram performed at admission. |

| Patients with a valve heart disease eligible for surgery. |

| Patients with a known past medical history of diffuse coronary artery disease noneligible for revascularization. |

| Patients with known or confirmed allergy to some antiplatelet drug. |

|

IMPACT-TIMING-GO, IMPACT of time of intervention in patients with myocardial infarction with non-ST segment elevation. Management and outcomes; MINOCA, Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. |

Endpoints

The study primary endpoint is to know the degree of compliance of the recommendations included in the clinical practice guide-lines in patients admitted due to NSTEACS treated with coronary angiography, in Spain, describe the use of antithrombotic treatment before cardiac catheterization, and the time elapsed until it is performed in the real-world clinical practice.

The secondary endpoints are:

- – To describe the baseline, clinical, and epidemiological characteristics of the study population.

- – To study the rates of cardiovascular mortality, new revascularization, stent thrombosis, and hospitalizations due to heart failure during admission and at the 1-and-3-year follow-up.

- – To describe major cardiovascular adverse events of all-cause mortality, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal infarction, and the rate of major bleeding grades 3, 4, and 5 according to the BARC scale (Bleeding Academic Research consortium.5) Data will be analyzed during admission and at the 1-and-3-year follow-up.

- – To know the medical treatment at discharge and at follow-up of patients discharged in Spain after NSTEACS.

- – To know the degree of control of the different cardiovascular risk factors associated with the endpoints defined in the ESC guidelines 2021 on prevention of cardiovascular disease in the routine clinical practice.6

Data curation and definitions

Data will be collected prospectively by trained medical investigators from each participant center in a specific standard form. Demographic data, the baseline clinical characteristics, and all analytical, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic data will be included as well.

Similarly, data on disease progression and the in-hospital stay, indication for coronary angiography and when it is be performed, type of treatment received (conservative, stent implantation or revascularization surgery), and the in-hospital complications occurred (hemorrhages and severity, heart failure or shock, reinfarction, stroke, confusional state, mechanical and arrhythmic complications, infectious complications requiring antibiotic therapy, and mortality causes) will be collected. Finally, the medical treatment at hospital discharge and level of compliance of the current recommendations based on the clinical practice guidelines will be studied too.

The definitions of the variables are shown on table 2.7-8

Table 2. Definitions of target variables

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | All deaths regardless of their cause. |

| Cardiovascular death | All deaths of vascular causes both cardiac (heart failure/shock; malignant arrhythmias; myocardial infarction) and non-coronary vascular including cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary embolism, aneurysms/aortic dissections, acute ischemia of lower limbs, etc.

All sudden deaths of unknown causes will be adjudicated as cardiovascular death. |

| Non-cardiac death | All deaths that do not meet the previous definition like deaths due to infections, cancer, pulmonary diseases, accidents, suicide or trauma. |

| Myocardial infarction | It is defined based on the criteria established in the 4th and current Universal definition.4 Therefore, patients with type 2 infarction, extracardiac causes or without elevated markers of myocardial damage were excluded. |

| Stroke/Transient ischemic attack | New-onset neurological, focal or global deficit due to ischemia or hemorrhage, and as long as it is part of diagnostic judgement at hospital discharge. |

| Stent thrombosis | Defined based on the Academic Research Consortium of randomized clinical trials with stents.7 |

| New revascularization | All unscheduled revascularizations performed after hospital discharge, whether surgical or percutaneous, including target vessel failure and target lesion failure. |

| Admission due to heart failure | Unscheduled hospital admission > 24 hours with a primary diagnosis of heart failure based on the current defintion.8 |

Follow-up

Clinical follow-up to detect events will be conducted by medical investigators through on-site visits, health record reviews or phone calls with the patient, family members or treating physician at 1 and 3 years. Clinical variables, functional class, and additional variables (analytical, electrocardiographic, and echocardiographic, and treatment received) will be included. The overall mortality rate and its causes, need of emergency hospitalization (duration > 24 hours) and its causes, and the rates of non-fatal infarction and stroke will be collected as well. All deaths due to myocardial infarction, sudden death or heart failure will be considered cardiovascular deaths.

Sample size estimate

Taking the events seen in previous studies with a population of similar characteristics as the reference,9-14 a sample size of 800 patients will be enough to know the baseline characteristics of the study population, and the therapeutic approach currently used in Spain in our routine clinical practice. Patients lost to follow-up will be handled by multiple imputation.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables will be expressed as number and percentage. Quantitative variables will be expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Quantitative variables with normal distribution will be expressed as median and interquartile range [25%-75%]. The normal distribution of quantitative variables will be assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff test. Regarding the reference variables, Student t test will be used to compare quantitative variables, and the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, if applicable, to compare categorical variables. Statistical analysis will be performed using the SPSS statistical software version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, United States).

Specific studies on subgroups of special interest will be conducted: feminine sex, patients ≥ 75 years, those with GRACE scores > 140, diabetic patients, those with a past medical history of renal failure, with an indication for chronic oral anticoagulation, with multivessel disease, acute myocardial infarction, ventricular dysfunction according to the current clinical practice guidelines and based on the day of admission (holiday vs working day), and patients who require transfer to tertiary centers to receive a coronary angiography.

Ethical principles

Inclusion in the study will not imply changes to the patients’ treatment. Instead, it will follow the routine clinical practice and the recommendations set forth by the current clinical practice guidelines. Therefore, antithrombotic treatment and additional examinations including the need for a coronary angiography and the time it is performed will all be decided by the heart team based on the routine clinical practice. Coronary angiography, vascular access, antithrombotic treatment during the procedure, and the material and devices used will all be decided by the treating operator in charge of the case. All patients will sign a written informed consent form before being included in the study that will be conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study will also observe all legal regulations applicable to this type of studies and follow the good clinical practice rules while being conducted.

DISCUSSION

The IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry will give us information on the current real-world management of patients with NSTEACS with invasive treatment and causal coronary artery disease, which will allow us to assess the degree of implementation of the current recommendations of ESC guidelines 2020 on cardiac catheterizations performed within the first 24 hours and no pretreatment with P2Y12 inhibitors. Similarly, different prognostic differences that early invasive treatment and no pretreatment could have in the real life of patients diagnosed with NSTEACS could be suggested.

Despite the clinical practice guidelines recommendations on the invasive treatment of patients with NSTEACS, the main clinical trials published to this date have been unable to demonstrate any clear benefits from systematic early invasive treatment.9-14 The VERDICT trial,9 published in 2018, randomized 2147 patients with NSTEACS on a 1:1 ratio to receive early (< 12 hours) or delayed (48 to 72 hours) cardiac catheterization. No significant differences were found in the composite endpoint of major cardiovascular events at 4-year follow-up. However, in the subgroup of patients with GRACE scores > 140 statistically significant differences were seen favorable to the early strategy regarding major adverse cardiovascular events (hazard ratio, 0.81; 95% confidence interval, 0.67-1.01; P = .023). Consistent with this, the TIMACS clinical trial10 published in 2008 of 3031 patients with NSTEACS found no differences in the primary endpoint when early invasive strategy (< 24 hours) and delayed approach (> 36 hours) were compared, except for, once again, in patients with GRACE scores > 140. Other randomized clinical trials with fewer patients show contradictory results11-14 some without significant differences.15 Also, in many cases, the results favorable to the early strategy are associated with refractory ischemia, not with hard endpoints like cardiovascular mortality or non-fatal myocardial infarction. In Spain, evidence on the management of NSTEACS is prior to the current clinical practice guidelines,16-17 and the most recent registry is retrospective, which is suggestive of a possible mortality benefit in patients with GRACE scores > 140.18 Over the last 2 decades, in our country, the use of an invasive strategy in patients with NSTEACS has increased significantly from 20% in the MASCARA registry in 200516 up to 80% in the DIOCLES study from 2012.17 However, evidence is scarce on catheterization times, our capacity to adapt to current recommendations (the median time of the DIOCLES trial was 3 days), the possible impact this time reduction can have, and on the consequencies from not starting antiplatelet pretreatment in patients who don’t meet the times recommended.

On the other hand, the current formal recommendation from the clinical practice guidelines of not pretreating systematically with a P2Y12 inhibitor (level of recommendation IIIA1) patients on early invasive treatment is mainly based on 3 clinical trials and their meta-analysis.19 In the ACCOAST trial, pretreatment with prasugrel did not reduce thrombotic events in patients with NSTEMI. However, cardiac surgery-related and potentially fatal hemorrhages increased.20 We should mention that the median time elapsed since the prasugrel loading dose until the coronary angiography was performed was 4 hours. In the ISAR-REACT 5 trial published in 2019, a non-pretreatment strategy with prasugrel in patients with ACS vs pretreatment with ticagrelor proved superior regarding the primary endpoint of thrombotic events with a tendency towards fewer hemorrhagic events.21 We should mention that the intrinsic effect of the drug used should not be obviated or else the fact that the median time elapsed since randomization until the prasugrel loading dose was received in the non-pretreatment group was 60 minutes. Finally, the first study that compared 2 different pretreatment strategies vs the intraoperative administration of ticagrelor did not show any clear benefits regarding thrombosis or a deleterious effect of pretreatment regarding bleeding.22 Once again, the median time elapsed until the cardiac catheterization was performed was < 24 hours since hospital admission (23 hours). Surprisingly, clinical practice guidelines leave the door opened to a weak level of recommendation (IIbC) regarding pretreatment of patients in whom early catheterization < 24 hours is not possible.1

In conclusion, current recommendations on early invasive treatment and no antiplatelet pretreatment in patients with NSTEACS are controversial and can also be difficult to implement in the routine clinical practice in our setting. The ultimate objective of the IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry is to shed light on the current management of NSTEACS in Spain. After the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the general structure of the healthcare system and the drop in the number of interventional procedures performed in 2020,23 we should expect to see pre-pandemic numbers in 2022 and cath labs and cardiac surgery intensive care units going back to normal. Therefore, moment seems ripe to conduct a real-world registry.

CONCLUSIONS

The IMPACT-TIMING-GO registry is the first prospective study ever conducted in Spain that will be giving us information on the early therapeutic strategies—both pharmacological and interventional—performed in our country in patients with NSTEACS after the publication of the ESC guidelines 2020, and the impact of these and other measures indicated in these patients at follow-up.

FUNDING

This unfunded study has been promoted by the Spanish Society of Cardiology Young Cardiologists Working Group with scientific endorsement from the Spanish Society of Cardiology.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design, data curation and review, statistical analysis, and manuscript drafting: P. Díez-Villanueva, F. Díez-Delhoyo, and M.T. López-LLuva. All the authors participated in the manuscript review and approval process.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the Spanish Society of Cardiology Young Cardiologists Working Group for their drive to engage the youth in medical research.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The management of patients with NSTEACS includes dual antiplatelet therapy with a P2Y12 inhibitor and, in most cases, invasive approach through cardiac catheterization for further revascularization. The current ESC clinical practice guidelines recommend early invasive approach (<24 hours) and no pretreatment systemically though both aspects are still controversial.

- The degree of implementation of such recommendations in the routine clinical practice, in Spain, is still unknown.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study will improve our knowledge on early therapeutic approach, and its prognostic impact in patients admitted due to NSTEACS in Spain.

- Also, it will bring us information on the characteristics and clinical evolution of these patients in association with the recommendations and therapeutic targets we have today.

REFERENCES

1. Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:1289-1367.

2. Díez-Villanueva P, Méndez CJ, Alfonso F. Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome in the elderly. J Geriatr Cardiol JGC. 2020;17:9-15.

3. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2354-2394.

4. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315.

5. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736-2747.

6. Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2022;75:429.

7. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Circulation. 2018;137:2635-2650.

8. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3599-3726.

9. Kofoed KF, Kelbæk H, Hansen PR, et al. Early Versus Standard Care Invasive Examination and Treatment of Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation. 2018;138:2741-2750.

10. Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2165-2175.

11. Thiele H, Rach J, Klein N, et al. Optimal timing of invasive angiography in stable non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Leipzig Immediate versus early and late PercutaneouS coronary Intervention triAl in NSTEMI (LIPSIA-NSTEMI Trial). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2035-2043.

12. Milosevic A, Vasiljevic-Pokrajcic Z, Milasinovic D, et al. Immediate Versus Delayed Invasive Intervention for Non-STEMI Patients: The RIDDLE-NSTEMI Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:541-549.

13. Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP, et al. Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2009;302:947-954.

14. Lemesle G, Laine M, Pankert M, et al. Optimal Timing of Intervention in NSTE-ACS Without Pre-Treatment: The EARLY Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:907-917.

15. Janssens GN, van der Hoeven NW, Lemkes JS, et al. 1-Year Outcomes of Delayed Versus Immediate Intervention in Patients With Transient ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:2272-2282.

16. Ferreira-González I, Permanyer-Miralda G, Marrugat J, et al. MASCARA (Manejo del Síndrome Coronario Agudo. Registro Actualizado) study. General findings. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2008;61:803-816.

17. Barrabés JA, Bardají A, Jiménez-Candil J, et al. Prognosis and management of acute coronary syndrome in Spain in 2012: the DIOCLES study. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2015;68:98-106.

18. Álvarez Álvarez B, Abou Jokh Casas C, Cordero A, et al. Early revascularization and long-term mortality in high-risk patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. The CARDIOCHUS-HUSJ registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2020;73:35-42.

19. Dawson LP, Chen D, Dagan M, et al. Assessment of Pretreatment With Oral P2Y12 Inhibitors and Cardiovascular and Bleeding Outcomes in Patients With Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2134322.

20. Montalescot G, Bolognese L, Dudek D, et al. Pretreatment with prasugrel in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:999-1010.

21. Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, et al. Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1524-1534.

22. Tarantini G, Mojoli M, Varbella F, et al. Timing of Oral P2Y12 Inhibitor Administration in Non-ST Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2450-2459.

23. Romaguera R, Ojeda S, Cruz-González I, collaborators of the ACI-SEC, REGISTRY COLLABORATORS. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 30th Official Report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2020) in the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74:1095-1105.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: There are few data on the utility of drug-coated balloons (DCB) for the side branch treatment of bifurcated lesions. Our objective was to determine the long-term effectiveness of such device in this scenario.

Methods: Retrospective-prospective registry of all such lesions treated with DCB (paclitaxel coating) at our unit from 2018 until present day with clinical follow-up including a record of adverse events.

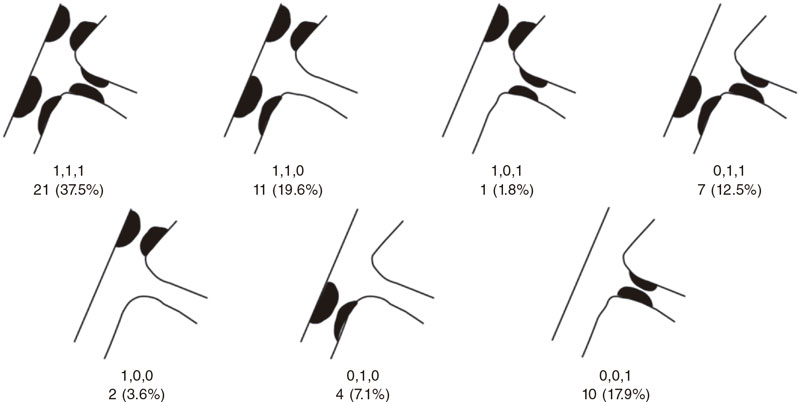

Results: A total of 56 lesions from 55 patients were included. The main demographic characteristics were mean age, 66.2 ± 11.3; and/or women, 27.3%; hypertension, 67.3%; dyslipidemia, 83.6%, and diabetes, 32.7%. The most common causes according to the coronary angiography were non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndrome and stable angina. The main characteristics of the lesions were the location (circumflex-obtuse marginal, 19.6%; left anterior descending-diagonal, 64.3%; left main-circumflex, 8.9%; posterior descending-posterolateral trunk, 7.1%. The Medina classification was 1-1-1 37.5% of the times, and 1-1-0, 19.6% of the times. The rate of in-stent restenotic lesions was 32.1%. Procedural characteristics: radial access, 100%; side branch (SB) and main branch (MB) predilatation, 83.9% and 58.9%, respectively; MB stenting, 71.4%; POT technique, 35.7%; final kissing, 48.2%; optical coherence tomography/intravascular ultrasound, 7.1%. Procedural success was achieved in 98.2% of the cases. The median follow-up he all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction and lesion thrombosis, and target lesion revascularization rates were .7%, 0%, and 3.6%, respectively.

Conclusions: SB treatment with DCB in selected bifurcation lesions is safe and highly effective with a long-term success rate of 96.4%. Very large studies are still required to compare this strategy to SB conservative approach, and determine its optimal treatment.

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon. Bifurcation lesions. Follow-up study. Side branch.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Hay pocos datos acerca de la utilidad del balón farmacoactivo (BFA) para el tratamiento de la rama lateral de las lesiones en bifurcación. El objetivo fue determinar la efectividad a largo plazo de dicho dispositivo en este escenario.

Métodos: Registro retrospectivo-prospectivo de todas las lesiones de este tipo tratadas con BFA recubierto de paclitaxel en nuestra unidad desde 2018 hasta la actualidad. Se realizó un seguimiento clínico con registro de eventos adversos.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 56 lesiones de 55 pacientes. Principales características demográficas: edad media 66,2 ± 11,3 años, 27,3% mujeres, 67,3% hipertensión arterial, 83,6% dislipemia y 32,7% diabetes. Las indicaciones más frecuentes para el cateterismo fueron síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del ST y angina estable. Características de las lesiones tratadas: localización circunfleja-obtusa marginal 19,6%, descendente anterior-diagonal 64,3%, tronco común-circunfleja 8,9% y descendente posterior-tronco posterolateral 7,1%. Según la clasificación de Medina, el tipo más frecuente fue el 1,1,1 con el 37,3%, seguido del 1,1,0 con el 19,6%. Las lesiones tipo reestenosis en el interior del stent fueron del 32,1%. Características principales del procedimiento: acceso radial 100%, predilatación de rama lateral 83,9% y de rama principal 58,9%, stent en rama principal 71,4%, técnica POT 35,7%, kissing final 48,2% y tomografía de coherencia óptica/ecocardiografía intravascular 7,1%. Se logró el éxito del procedimiento en el 98,2%. Con un seguimiento medio de 12 meses, se registraron una incidencia de muerte por cualquier causa del 3,7%, trombosis lesional o infarto 0%, y revascularización de la lesión diana del 3,6%.

Conclusiones: El tratamiento con BFA de la rama lateral en lesiones bifurcadas seleccionadas es seguro y presenta una alta efectividad, con una tasa de éxito a largo plazo del 96,4%. Serían necesarios estudios muy amplios que permitieran comparar dicha estrategia con el abordaje conservador de la rama lateral y determinar cuál es su tratamiento óptimo.

Palabras clave: Balón farmacoactivo. Lesiones en bifurcación. Estudio de seguimiento. Rama lateral.

Abbreviations

DCB: drug-coated balloon. ISR: in-stent restenosis. MB: main branch. SB: side branch.

INTRODUCTION

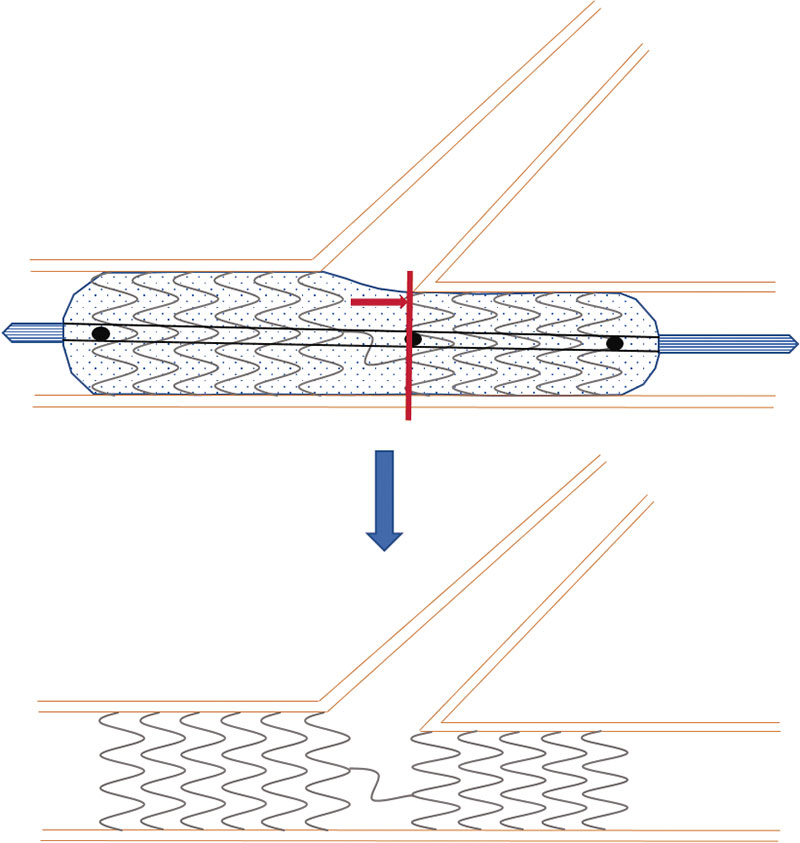

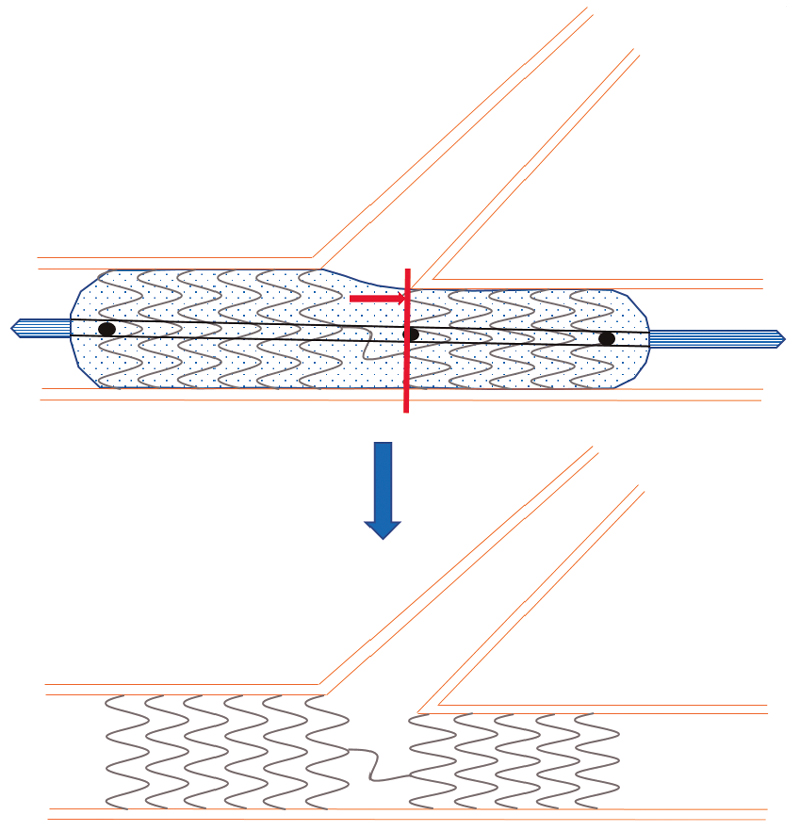

Coronary bifurcation lesions are still challenging for interventional cardiologists. The complexity surrounding such lesions regarding their anatomical, functional, and even clinical aspects truly complicates the management of this entity despite its high incidence rate that can be up to 20% of all the lesions that are treated at a cath lab on a routine basis. The relentless publication of articles on such lesions over the last few decades, the creation of specific study groups like the European Bifurcation Club, and the periodic publication of consensus documents for the management of this entity shows, without a doubt, that this scenario is in constant change and has not been solved today yet. One of the most controversial aspects is the importance of the side branch (SB) regarding the long-term prognosis of such lesions. Drug-coated balloon (DCB) is part of the therapeutic armamentarium of interventional cardiologists to treat coronary bifurcation lesions. Its utility for the management of certain anatomical settings like in-stent restenosis (ISR) type of lesions has already been demonstrated. However, its effectiveness to treat the SB is much less evident with scarce studies available in the medical literature. The theoretical advances posed by this device to treat the SB would be the administration of antiproliferative drugs into the ostium mainly, the lack of distortion of its original anatomy, and the minimization of strut deformation at carina level.1

This article presents a registry with the results obtained in our unit with the management of SB with DCB with a longer than usual clinical follow-up in this type of studies.

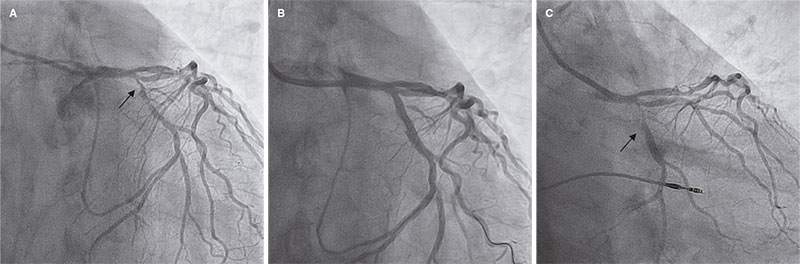

METHODS

This was a single-center, prospective-retrospective registry started back in 2019 of all coronary bifurcation lesions where the SB was treated with paclitaxel-coated DCB from October 2018 through March 2022. The device used was the SeQuent Please NEO (Braun, Germany), a paclitaxel-iopromide coated polymer-free balloon using Paccocath technology. Inclusion criteria were the presence of coronary bifurcation lesions with 1 compromised SB of, at least, 2 mm in diameter through visual angiographic estimate regardless of the aprioristic presence of a diseased SB or the appearance of carina displacement or slow flow after treating the main branch (MB). Also, the operator should consider the DCB approach of clinical and prognostic interest. Patient recruitment in the registry was on the rise: 4 patients in 2018, another 4 in 2019, 9 patients in 2020, 31 in 2021, and finally 7 within the first 3 months of 2022. No exclusion criteria were established. Approach strategy consisted of an early provisional stenting or DCB technique to treat the MB when damaged. Further management of SB with DCB was left to the operator’s criterion if, after treating the MB, significant damage done to the SB would require stenting in such branch. In that case, the patient would not be included, and the SB would not be eligible for treatment with a DCB. If, after preparing the lesion, the operator would actually consider using the DCB option, that would be the time to include the patient in the study. The rate of procedural failure—defined as the impossibility to cross the lesion with the DCB once it was used or unsatisfactory angiographic outcomes after balloon inflation involving SB stenting. The protocol for using the DCB—based on the recommendations established on the use of such devices—consisted of SB predilatation with non-compliant or scoring balloons in a 0.8-1 vessel/balloon diameter ratio, use of the device if an acceptable angiographic result with TIMI grade-3 flow was achieved, lack of significant dissection, and residual stenosis < 30%. If other lesions different from the one that triggered the inclusion in the registry needed revascularization, this was scheduled for a second surgical act. The study design followed a per protocol analysis to estimate the benefits of the technique described compared to the routine clinical practice including cases with successful DCB treatment at the follow-up and excluding those with acute device failure or impossibility to use the device once opened for being unable to cross the lesion. The lack of dissection after DCB that required stenting with residual stenosis < 50%, and final TIMI grade-3 flow was considered as procedural success. Device failure, on the other hand, was considered as an impossible DCB inflation once used or the need for stenting the SB with unsatisfactory DCB results. Different clinical variables from the patient were analyzed, as well as the lesion anatomy, and the procedural intervention per se. Retrospective clinical follow-up of patients successfully treated with the DCB was conducted. Follow-up went on for a maximum of 2 years after the procedure, and prospectively since the registry started back in 2019 until present time. This follow-up was conducted through phone calls or by checking the patients’ electronic health records. The ARC-2 definitions2 were used to collect the adverse clinical events including a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, device thrombosis, clinically driven target lesion failure and revascularization, target vessel failure outside the target lesion, and revascularization of other lesions occurred at follow-up. All patients signed their written informed consent forms, and the study was approved by our center research ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

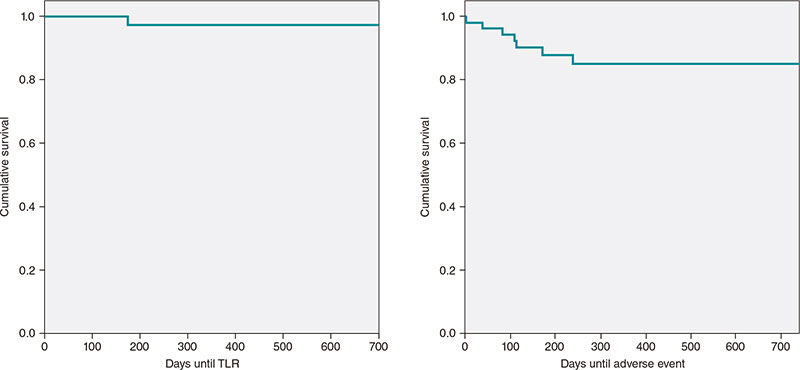

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentage. Also, actuarial curves of adverse event-free survival using the Kaplan-Meier method were built, specifically target lesion failure-free and adverse event-free curves (all-cause mortality, target lesion revascularization, target vessel failure, and revascularization of other lesions).

RESULTS

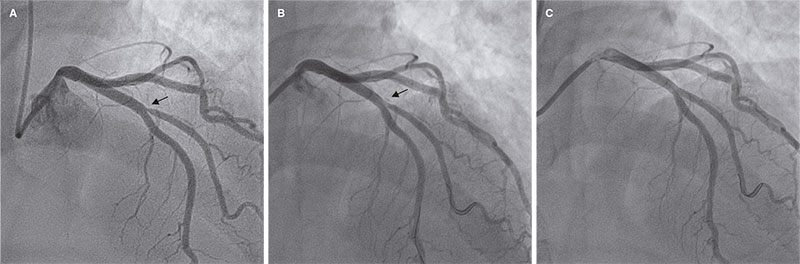

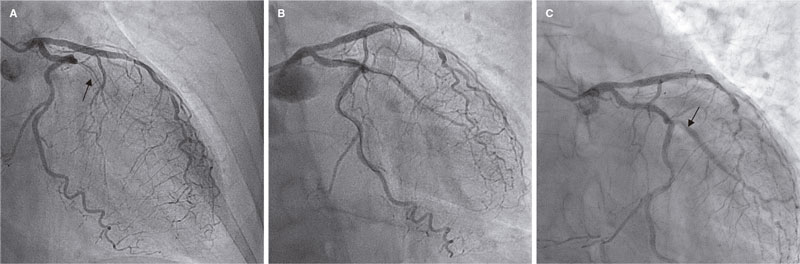

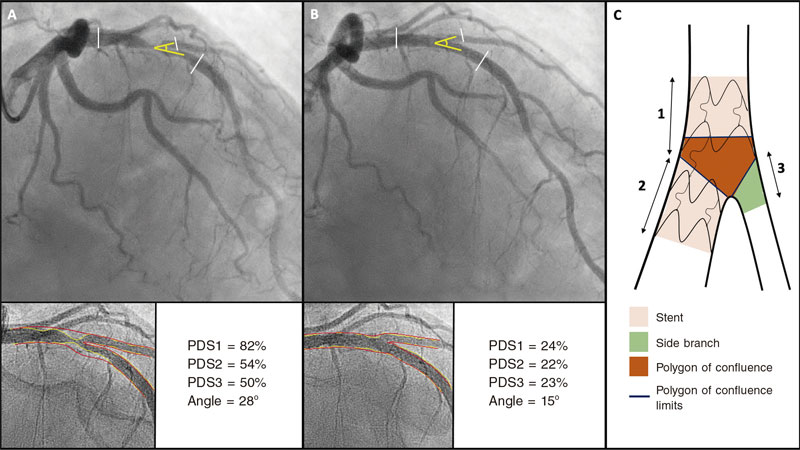

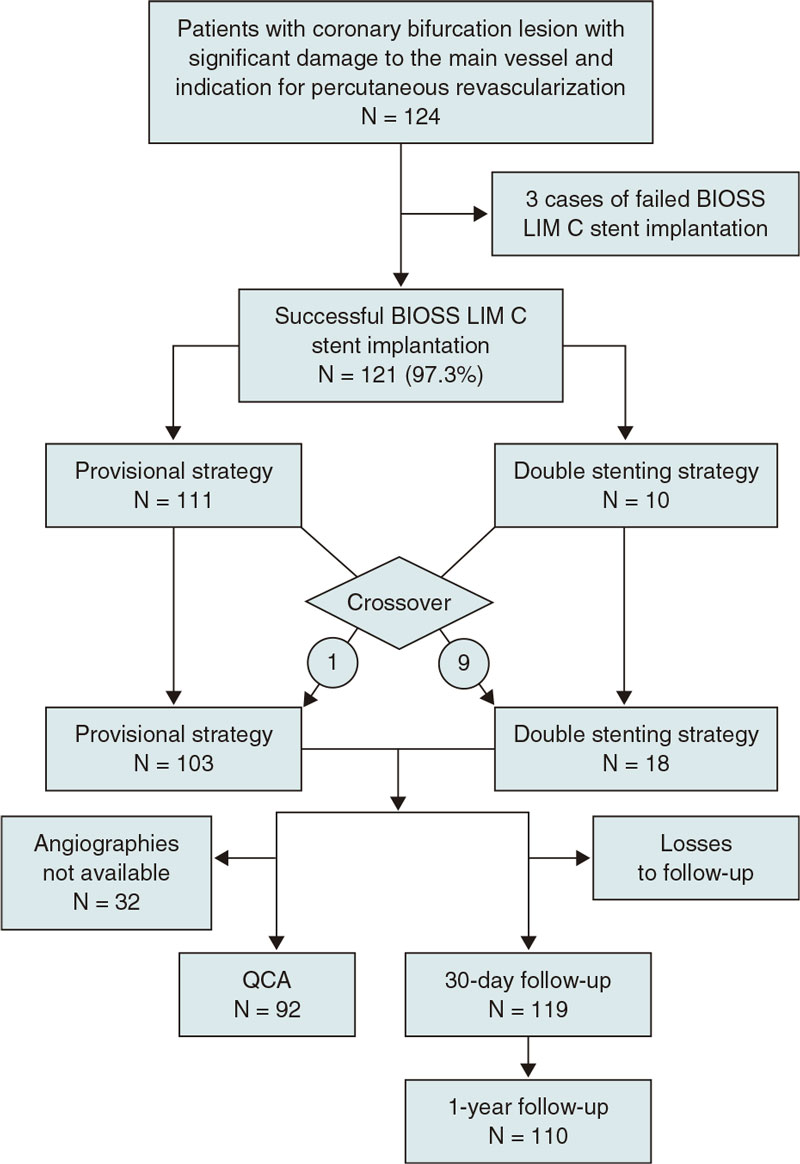

A total of 55 patients and 56 lesions were included since 2 different bifurcations found in 1 of the patients were treated in the same procedure. The patient/lesion flowchart included in the study is shown on figure 1. The patients’ clinical characteristics are shown on table 1. Vascular access was radial in 100% of the cases using a 6-Fr introducer sheath also in all of them. Table 2 shows the anatomical characteristics of target lesions. Figure 2 shows a schematic representation of the type of lesion according to the Medina classification. Table 3 shows the variables associated with the procedure. We should mention that all the clinical and anatomical data shown here, the patients’ high-risk profile with high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, and the large number of ISR-type of lesions reached 32.1% of the sample. The rate of lesions included with damage to 2 or 3 different bifurcation segments was 71.4% (40 out of 56). Regarding procedural factors the high rate of procedural success was significant (low rate of acute device failure with only 1 case of a type A dissection image after DCB inflation without damage to the distal flow and > 30% residual stenosis). Therefore, because of lesion location at ostium level, and possible damage to the MB (the left anterior descending coronary artery in this case), the operator decided to perform drug-eluting stent implantation for sealing purposes (figure 3). In all the remaining procedures, the acute result of the DCB was successful. In our series, the scarce use of intracoronary imaging modalities (only 7.1%) was also remarkable.

Figure 1. Flowchart of patients/lesions included in the study.

Figure 2. Number of lesions based on the type of bifurcation damage according to the Medina classification.

Figure 3. Only case of acute device failure. A: diagonal branch ostial lesion prior to the intervention (arrow); B: suboptimal outcome after drug-coated balloon (arrow); C: final outcome after stenting the side branch.

Table 1. Patients’ clinical characteristics

| N | 55 |

| Age | 66.2 ± 11.3 years [range, 45-91] |

| Sex | |

| Men | 40 (72.7%) |

| Women | 15 (27.3%) |

| Hypertension | 37 (67.3%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 46 (83.6%) |

| Smoking | 17 (30.9%) |

| Diabetes | 18 (32.7%) |