Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The use of transradial access for percutaneous coronary procedures has increased due to its advantages over the femoral approach. However, this benefit comes at the expense of a higher rate of radial artery occlusion (RAO). Our objective was to assess the incidence and predictors of RAO following transradial catheterization. Additionally, we studied anatomic variations of the radial artery (RA).

Methods: This prospective study enrolled 427 patients who underwent coronary angiography or angioplasty via transradial access. The forearm arteries were evaluated by ultrasound. If RAO was present, follow-up ultrasound examinations were performed at 1 and 3 months postprocedure.

Results: Our study population included 288 men (67.4%) and 139 women (32.6%). The mean age was 61.9 ± 11.1 years. RAO occurred in 48 patients (11.24%), and spontaneous recanalization was observed within 3 months in 15 patients (32.6%). On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of RAO were younger age (OR, 0.642; 95%CI, 0.480-0.858; P = .031), low periprocedural systolic blood pressure (OR, 0.598; 95%CI, 0.415-0.862; P = .007), a small radial diameter (OR, 0.371; 95%CI, 0.323-0.618; P = .031), insufficient anticoagulation (OR, 0.287; 95%CI, 0.163-0.505; P < .001), occlusive hemostasis (OR, 0.128; 95%CI, 0.047-0.353; P < .001), and long duration of hemostasis. The overall incidence of RA anatomic variations was 14.8% (n = 63). Among these, 40 patients (63.5%) had a high radial origin, 18 (28.6%) had extreme RA tortuosity, and 5 (7.9%) had a complete radioulnar loop.

Conclusions: The main modifiable predictors of RAO are insufficient heparinization and occlusive hemostasis. Preventive strategies should focus primarily on these 2 predictive factors to reduce the risk of RAO.

Keywords: Anatomic variations. Cardiac catheterization. Doppler ultrasound. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Predictors. Radial artery occlusion. Transradial access.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El acceso transradial para procedimientos coronarios percutáneos ha crecido en popularidad debido a sus ventajas sobre el abordaje femoral. Sin embargo, este beneficio se ve ensombrecido por una mayor tasa de oclusión de la arteria radial (OAR). Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la incidencia y los factores predictivos de OAR tras el cateterismo transradial. También se estudiaron las variaciones anatómicas de la arteria radial (AR).

Métodos: En este estudio prospectivo participaron 427 pacientes a los que se había realizado angiografía coronaria o angioplastia mediante acceso transradial. Se realizó una evaluación ecográfica de las arterias del antebrazo. En caso de OAR, se llevó a cabo otro control ecográfico al mes y a los 3 meses de la intervención.

Resultados: La población de estudio incluyó a 288 varones (67,4%) y 139 mujeres (32,6%). La edad media fue de 61,9 ± 11,1 años. La OAR se produjo en 48 pacientes (11,24%), de los cuales en 15 (32,6%) se produjo recanalización espontánea en el plazo de 3 meses. En el análisis multivariante, la edad más joven (OR = 0,642; IC95%, 0,480-0,858; p = 0,031), la presión arterial sistólica periprocedimiento baja (OR = 0,598; IC95%, 0,415-0,862; p = 0,007), el diámetro radial pequeño (OR = 0,371; IC95%, 0,323-0,618; p = 0,031), la anticoagulación insuficiente (OR = 0,287; IC95%, 0,163-0,505; p < 0,001), la hemostasia oclusiva (OR = 0,128; IC95%, 0,047-0,353; p < 0,001) y la larga duración de la hemostasia aparecieron como predictores independientes de OAR. La incidencia global de variaciones anatómicas de la AR fue del 14,8% (n = 63). Entre estos pacientes, 40 (63,5%) tenían un origen radial alto, 18 (28,6%) presentaban una tortuosidad extrema de la AR y 5 (7,9%) tenían un asa radiocubital completa.

Conclusiones: La heparinización insuficiente y la hemostasia oclusiva son los principales predictores de OAR modificables. La estrategia preventiva debe centrarse principalmente en estos 2 factores predictivos.

Palabras clave: Variaciones anatómicas. Cateterismo cardiaco. Ecografía Doppler. Intervención coronaria percutánea. Predictores. Oclusión de la arteria radial. Acceso transradial.

Abbreviations

RA: radial artery. RAO: radial artery occlusion.

INTRODUCTION

The use of the transradial approach for coronary interventions has become increasingly widespread in interventional cardiology due to its numerous advantages.1 As a result, current guidelines recommend it as the first-line approach.2

However, the benefits of this technique are tempered by the risk of radial artery occlusion (RAO), with reported rates ranging from 5% to 30%.3,4 The aim of this study was to assess the incidence and predictors of RAO following transradial catheterization using Doppler ultrasound for evaluation.

METHODS

Patient population

This longitudinal, single-center prospective study was conducted in the cardiology department of the Military Central Hospital in Algiers. After applying exclusion criteria (hemodynamic instability and ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), we included 427 consecutive patients undergoing transradial coronary procedures between January 2019 and March 2020. The study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices and was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients provided written informed consent.

Radial artery cannulation and retrograde radial arteriography

After radial artery (RA) puncture, a radial hydrophilic sheath (Radiofocus II, TERUMO Medical, Japan, or Prelude, MERIT Medical, United States) was introduced. An antispastic cocktail was then administered into the RA through the sheath, consisting of a saline solution, a vasodilator (1 mL of nicardipine), and a bolus of unfractionated heparin, which was administered either intravenously or directly into the RA as part of the spasmolytic cocktail, depending on the operator’s preference. In patients on vitamin K antagonists, these medications were not discontinued prior to the procedure.

Retrograde radial arteriography was performed by injecting a mixture of 4 mL of contrast and 4 mL of isotonic saline through the sheath. Radiographic images were then obtained in an anteroposterior projection.

Transradial coronary procedure

The standard approach was conventional right radial access. For coronary angiography, 5-French (Fr) hydrophilic sheaths and catheters were usually used. If the patient required revascularization, an ad hoc percutaneous coronary intervention was performed, using 6-Fr guiding catheters after exchanging the sheath from 5-Fr to 6-Fr. The usual dose of heparin is 5000 IU (2500 IU for oral anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist).

Hemostasis procedure

At the end of the procedure, the sheath was removed, and hemostasis was achieved using a hemostatic compression device (TR BAND, TERUMO Medical, Japan). A reverse Barbeau test5 was systematically performed. The hemostasis device was removed by nurses in the hospitalization unit. No standardized protocol for the duration of hemostasis was followed.

Assessment of postprocedural radial artery patency

Radial Doppler assessments were conducted before and after each transradial procedure. To evaluate RAO, pulsed Doppler was performed bilaterally on the radial and ulnar arteries. Normal arterial flow was indicated by a biphasic or triphasic signal, reflecting good perfusion. In cases of RAO, 2 additional ultrasonographic examinations were performed at 1 and 3 months, following the same protocol. Artery patency was assessed by an independent operator.

Classifications and definitions

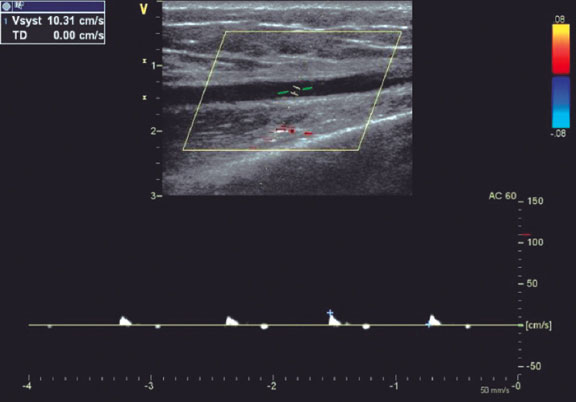

RAO was defined as the absence of anterograde flow in the RA on ultrasound (figure 1). The location of the radial occlusion was identified using color and pulsed Doppler. We delineated 3 anatomical territories: the distal third, extending from the radial styloid to approximately 7 to 10 cm proximally; the proximal third, from the elbow folds to approximately 7 to 10 cm distally; and the middle third, located between the previous 2 regions (middle part of the forearm).

Figure 1. Radial artery with occlusion in the distal third. Pulsed Doppler flow targets a stop flow indicating radial occlusion.

The type of hemostasis, whether occlusive or patent, was assessed: patent hemostasis was indicated by the presence of a plethysmographic signal in the RA during the reverse Barbeau test,5 which involves compression of the ulnar artery. The operator did not intervene during this process but simply recorded whether the artery remained patent or not.

The internal luminal diameter of the RA was defined as the distance between the leading edges of the intima-lumen interface on the superficial wall and the lumen-intima interface on the deep wall.6

The R/S ratio (radial/sheath) was calculated by dividing the luminal diameter of the RA by the external diameter of the sheath (Radiofocus II: 5-Fr = 2.29 mm, 6-Fr = 2.62 mm, 7-Fr = 2.97 mm; Prelude: 5-Fr = 2.52 mm, 6-Fr = 2.83 mm). This ratio was categorized qualitatively as < 1 or ≥ 1.

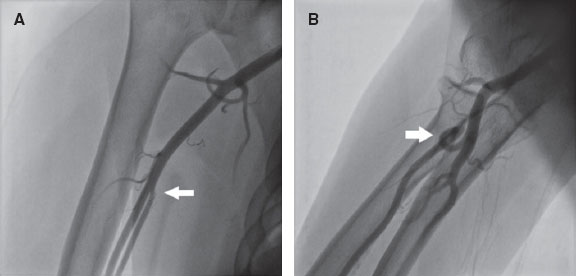

RA anatomical variations of clinical relevance were classified according to definitions provided in the literature.7,8 A high origin (high bifurcation) of the RA (figure 2) was defined with reference to the intercondylar line of the humerus. A radioulnar loop was characterized by the presence of a complete 360° loop of the RA, while radial tortuosity was identified by a curvature greater than 45°.

Figure 2. Anatomic variations of the radial artery. A: high origin of the radial artery. The radial and ulnar arteries separate at the level of the middle third of the humerus (arrow). B: radioulnar loop was defined as a complete 360° loop of the radial artery distal to the bifurcation of the brachial artery (arrow).

A blood pressure profile was obtained on the same side as the radial access. Forearm hematomas were classified according to the “EASY” study9: type I: < 5 cm in diameter; type II: < 10 cm; type III: > 10 cm but not extending to the elbow; type IV: extending beyond the elbow; type V: resulting in an ischemic lesion.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Software version 25. Parameters of interest are reported with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). For all tests, a significance threshold of 5% was retained. All tests were performed bilaterally. The following tests were used to compare groups: the chi-square test was used to compare 2 qualitative variables; the Student t-test or analysis of variance was used to compare a quantitative variable with a qualitative variable, with the Fisher test being applied when variances were unequal; and logistic regression was used to identify predictors of RAO.

RESULTS

Clinical and procedural characteristics of the study population

During the study period, 441 patients were screened. Of these, transradial access failed in 14 patients, who were excluded from the study, resulting in an eligible sample of 427 patients (mean age 61.9 ± 11.1 years, 67.4% male). Among the patients, 260 had hypertension (60.9%), and nearly half had diabetes (48.9%).

Table 1 summarizes the procedural data. The sheaths used were mainly 6-Fr (83.6%), and heparin was injected intra-arterially in 63.5% of patients. The mean heparin dose was 5669 ± 1394 IU, with a higher dose given when percutaneous coronary intervention was performed (4940 ± 339 IU vs 7491 ± 1368 IU; P < .001).

| Procedural characteristics | Patients N (%) |

|---|---|

| Indication | |

| CCS | 227 (53.2%) |

| ACS (NSTEMI) | 200 (46.8%) |

| Type of procedure | |

| Diagnostic angiography | 305 (71.4%) |

| PCI | 122 (28.6%) |

| Previous radial procedures | 68 (15.9%) |

| Right radial access | 410 (96.0%) |

| Puncture attempts | |

| 1 attempt | 258 (60.4%) |

| 2 attempts | 99 (23.2%) |

| ≥ 3 attempts | 70 (16.4%) |

| Sheath size | |

| 5-Fr | 68 (15.9%) |

| 6-Fr | 357 (83.6%) |

| 7-Fr | 2 (0.5%) |

| Heparin administration | |

| Intra-arterial | 271(63.5%) |

| Intravenous | 156 (36.5%) |

| Heparin dose (IU) | 5669 ± 1394 |

| Angiography | 4940 ± 339 |

| PCI | 7491 ± 1368 |

| Catheter diameter | |

| 5-Fr | 300 (70.3%) |

| 6-Fr | 125 (29.3%) |

| 7-Fr | 2 (0.5%) |

| Number of catheters used | |

| 1 | 43 (10.1%) |

| 2 | 271 (63.5%) |

| ≥ 3 | 113 (26.4%) |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) | 11.22 ± 12.09 |

| Radiation dose (mGy) | 564 ± 538 |

| Contrast amount (mL) | 98.97 ± 54.09 |

| Procedure time (min) | 39.16 ± 34.6 |

| Angiography | 21.63 ± 9.98 |

| PCI | 82.99 ± 35.39 |

| Coronary lesions | |

| Normal coronaries | 134 (31.4%) |

| 1 vessel disease | 131 (30.7%) |

| 2 vessel disease | 87 (20.4%) |

| 3 vessel disease | 75 (17.6%) |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; Fr, French; IU, international unit; NSTEMI, non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. |

|

Incidence and characteristics of radial artery occlusion

RAO occurred in 48 patients (11.24%). Of these, 89.6% were asymptomatic, and the radial pulse remained palpable in 14 patients (29.2%). At 1 month, 2 patients were lost to follow-up. Among the remaining 46 patients, spontaneous recanalization occurred in 13 patients (28.3%). At the 3-month follow-up, the recanalization rate increased to 32.6% (15 cases).

The site of RAO was the distal third in 7 patients (14.6%), the middle third in 21 patients (43.8%), and the proximal third in 20 patients (41.7%).

Predictors of radial artery occlusion

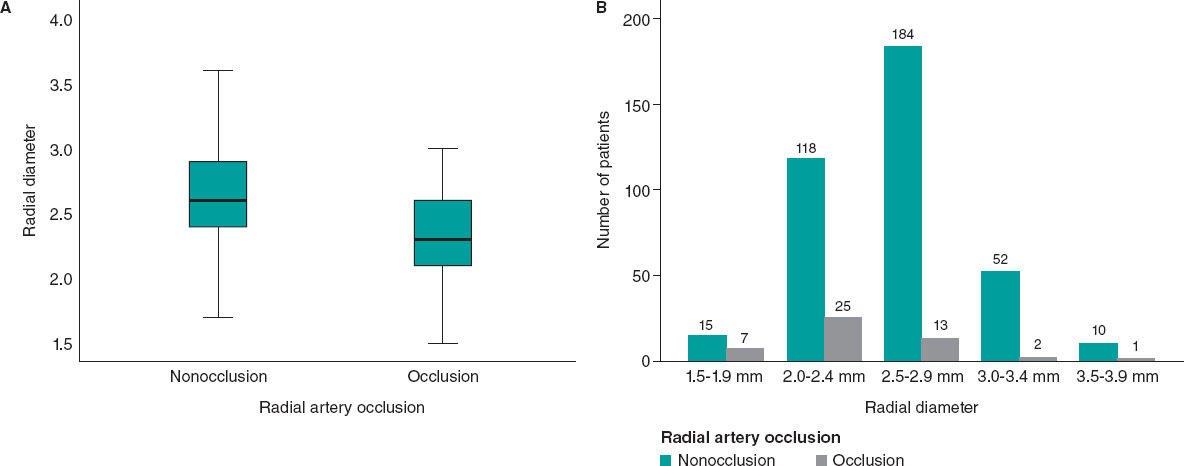

Patients with RAO were significantly younger (table 2). The mean periprocedural systolic blood pressure in the RAO group was significantly lower (138.04 mmHg ± 21.92, vs 145.84 mmHg ± 21.10; P = .017). Type A Barbeau test was associated with a higher risk of RAO compared with types B and C, and patients with occlusion had a smaller RA diameter (2.34 mm ± 0.40 vs 2.61 mm ± 0.37; P < .001) (figure 3).

Table 2. Comparison of patients with and without RAO

| Clinical data | Procedural data | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-RAO (n= 379) | RAO (n= 48) | P | Non-RAO (n= 379) | RAO (n= 48) | P | ||

| Age | 62.6 ± 10.6 | 56.4 ± 14.0 | < .001* | Previous TRA | 61 (16.0%) | 7 (14.5) | .63 |

| Female sex | 122 (32.1%) | 17 (35.4%) | .65 | Diagnostic angiography | 266 (70.1%) | 39 (81.2%) | .11 |

| Hypertension | 237 (62.5%) | 23 (47%) | .051 | ≥ 2 puncture attempts | 147 (38.7%) | 22 (45.8%) | .41 |

| Diabetes | 182 (48%) | 27 (56%) | .28 | IV heparin | 136 (35.8%) | 20 (41.6%) | .43 |

| Dyslipidemia | 44 (11.6%) | 6 (12.5%) | .85 | Heparin dose (IU) | 5754 ± 1378 | 5007 ± 1352 | < .001* |

| Smoking | 75 (19.7%) | 9 (18.7%) | .86 | Spasm | 60 (15.8%) | 12 (25.0%) | .11 |

| BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 | 123 (32.4%) | 16 (33.3%) | .90 | Procedure time (min) | 39.85 ± 34.56 | 33.73 ± 34.78 | .249 |

| Mean PSBP (mm Hg) | 145.84 ± 21.10 | 138.04 ± 21.92 | .017* | Number of catheters | 2.30 ± 0.88 | 2.21 ± 0.92 | .75 |

| Barbeau test type A | 99 (26.1%) | 20 (41.6%) | .044* | Occlusive hemostasis | 241 (63.5%) | 42 (87.5%) | .001* |

| RAD (mm) | 2.61 ± 0.37 | 2.34 ± 0.40 | < .001* | Hemostasis duration (h) | 4.29 ± 1.22 | 5.15 ± 1.41 | .006* |

| APT | 336 (88%) | 41 (85%) | .51 | ||||

| VKA (INR ≥ 2) | 16 (4.2%) | 5 (10.4%) | .061 | ||||

| MVCD | 149 (39.3%) | 13 (27.1%) | .20 | ||||

|

APT, antiplatelet therapy; BMI, body mass index; INR, international normalized ratio; IV, intravenous; IU, international unit; MVCD, multivessel coronary disease = ≥ 2 lesions ; PSBP, periprocedural systolic blood pressure; RAD , radial artery diameter; RAO, radial artery occlusion; TRA , transradial access; VKA, vitamin K antagonist. * Statistically significant. |

|||||||

Figure 3. Radial artery diameter as a predictor of occlusion. A: the radial diameter is significantly smaller if there is RAO. B: less than 2.5 mm, the risk of occlusion becomes greater.

RAO procedural factors are listed in table 2. An R/S ratio < 1 was found in 35 patients in the RAO group vs 153 patients in the non-RAO group (72.9% vs 40.3%, P < .001). The mean heparin dose was significantly lower in patients with RAO (5007 ± 1352IU vs 5754 ± 1378 IU; P < .001), and the dose adjusted to weight was also significantly lower in the RAO group (62.31 ± 17.82 IU/kg vs 75.73 ± 22.57 IU/kg; P < .001). In addition, the RAO rate decreased significantly when the heparin dose exceeded 70 IU/kg.

Forty-two patients in the RAO group had occlusive hemostasis vs 241 in the non-RAO group (87.5% vs 63.5%; P = .001). Surprisingly, two-thirds of our patients (283 [66.3%]) had occlusive hemostasis. The mean duration of hemostasis was longer if there was RAO (5.15 h ± 1.41 vs 4.29 h ± 1.22; P < .001).

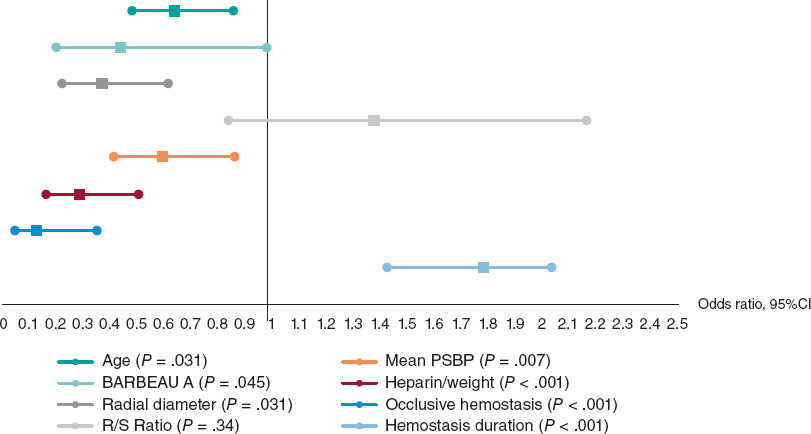

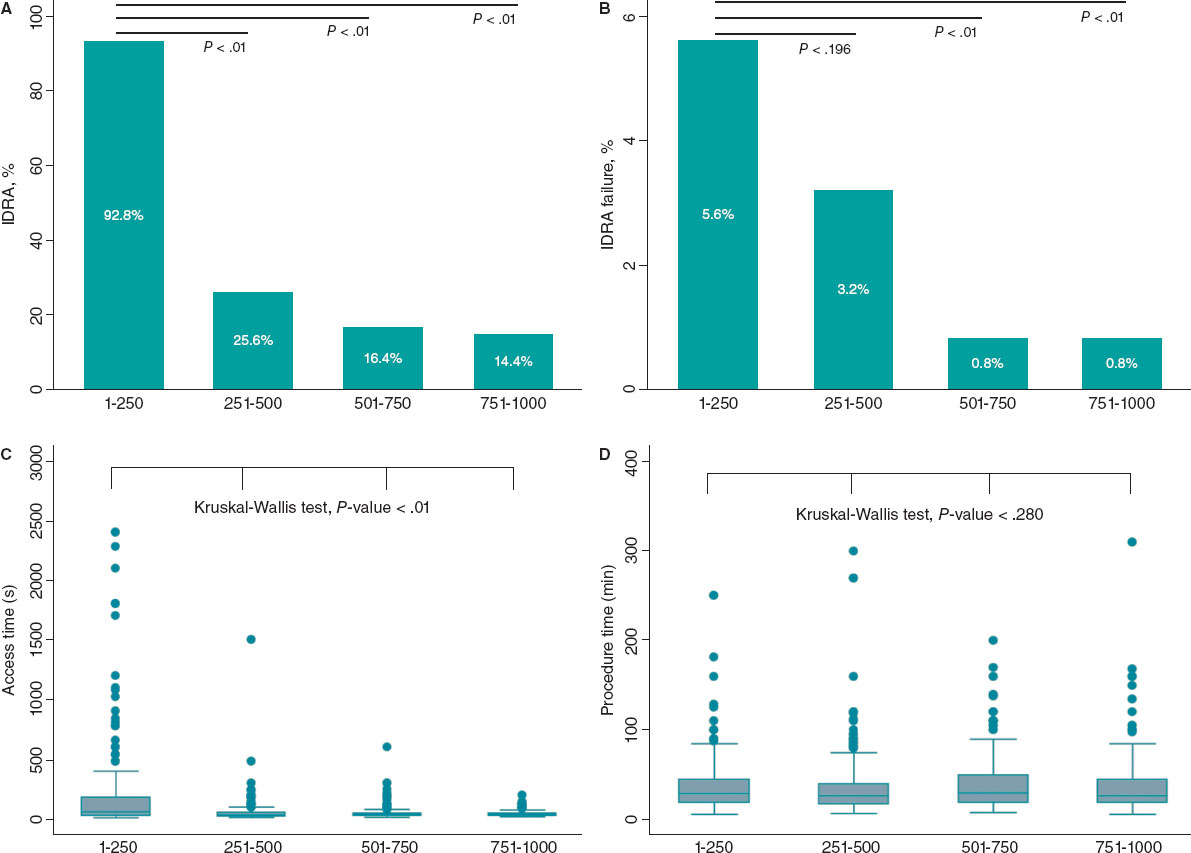

On multivariate logistic regression analysis (figure 4), the following factors were independent predictors of RAO: young age (odds ratio [OR], 0.642; 95%CI, 0.480-0.858; P = .031), low periprocedural systolic blood pressure (OR, 0.598; 95%CI, 0.415-0.862; P = .007), type A Barbeau test (OR, 0.441; 95%CI, 0.198-0.981; P = .045), small RA diameter (OR, 0.371; 95%CI, 0.323-0.618; P = .031), insufficient anticoagulation (OR, 0.287; 95%CI, 0.163-0.505; P < .001), occlusive hemostasis (OR, 0.128; 95%CI, 0.047-0.353; P < .001), and a long hemostasis duration (OR, 1.786; 95%CI, 1.428-2.039; P < .001).

Figure 4. Independent factors predictive of radial artery occlusion. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that the independent factors predictive of radial occlusion were young age, low periprocedural systolic blood pressure, type A Barbeau test, small radial artery diameter, insufficient anticoagulation, occlusive hemostasis, and long hemostasis duration. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; PSBP, periprocedural systolic blood pressure; RAO, radial artery occlusion.

Anatomic variations of the radial artery

The mean radial diameter was 2.58 mm ± 0.39, and the diameter was larger in men (2.69 mm ± 0.37 vs 2.36 mm ± 0.31; P < .001) and smaller in patients with diabetes (2.53 mm ± 0.38 vs 2.64 mm ± 0.38; P = .003). The mean radial diameter was significantly larger than the mean ulnar diameter (2.58 mm ± 0.39 vs 2.22 mm ± 0.43; P < .001).

Radial anatomical variations affected 63 patients (14.8%). The most common variation was a high origin of the RA, observed in 63.5% of cases (40 patients), followed by radial tortuosity in 28.6% (18 patients), radioulnar loop in 7.9% (5 patients). Anatomical variations were more frequent in women (23% vs 10.8%; P = .001) and in older patients, with a mean age of 66.3 years ± 10.2 vs 61.2 years ± 11.2 in those without variations (P = .001).

Periprocedural complications

Radial spasm occurred in 72 patients (16.9%). This complication was more frequent in women (29% vs 10.1%; P < .001), patients with diabetes (22.5% vs 11.5%; P = .002), and when 6-Fr catheters were used (14% vs 24%; P = .035). Forearm hematoma occurred in 25 patients (5.85%). According to the EASY classification,9 most hematomas were type I (17 patients, 68%), followed by type II (6 patients, 24%), with type III occurring in only 2 patients (8%).

DISCUSSION

The rate of RAO remains relatively high in some institutions.10,11 In the PROPHET study, the acute incidence of RAO (12%) was almost halved in 28 days (7%).3 Recanalization occurs as a result of activation of primary fibrinolysis.12 In the present study, the rate of radial recanalization at 3 months was 32.6%. The only predictor of recanalization was radial diameter: the larger the diameter, the higher the rate of spontaneous recanalization.

Zankl et al.13 found that RAO was located in the distal third of the forearm in 49% of patients, in the distal and middle third in 13.7%, and in the entire forearm (proximal third) in 37.3%. Dissections of the media also occur in the proximal RA, likely due to catheter progression or manipulation without protection of the sheath.14 In our opinion, this would explain the location of RAO in the proximal part of the artery.

Among our patients with RAO, 29.2% had a radial pulse. According to Uhlemann et al.,4 in 19.5% of patients with RAO on Doppler, the RA pulse was still palpable. This was likely due to retrograde filling of the RA by collaterals. Therefore, the diagnosis of RAO should be confirmed using a more objective method, such as Doppler ultrasound.

Young age is a predictor of RAO, possibly due to higher sympathetic reactivity in younger individuals, which increases their risk of spasm. However, this characteristic does not influence the rate of recanalization, likely because prolonged radial spasm leads to the formation of a permanent intra-arterial thrombus.

Low mean systolic blood pressure was also a predictor of radial occlusion. We speculate that hypertension and arterial stiffness may prevent complete interruption of flow during compression, thereby helping to maintain radial patency.15

There was a higher incidence of occlusion with type A Barbeau test. We believe that in cases with well-developed ulnar circulation, the ulnar artery generates a competitive retrograde flow that opposes the radial flow, promoting occlusion and hindering recanalization.

The likelihood of developing RAO is related to the size of the sheath,16 or more precisely, the R/S ratio.17 A prospective registry showed that 5-Fr sheaths reduced the rate of RAO by up to 55% compared with 6-Fr.4

A study by Pancholy et al.,18 demonstrated that intravenous heparin is as effective as intra-arterial heparin in reducing the incidence of RAO, suggesting that the systemic effect of heparin is more important than its local effect. A recently published meta-analysis identified higher heparin doses as the most significant measure for decreasing RAO.12 This results is in line with our finding that a dose of less than 70 IU/kg seems to promote the occurrence of RAO. The high prevalence of RAO and the benefit of higher doses of unfractionated heparin (≥ 50 IU/kg) in this setting were also highlighted by a meta-analysis of 112 studies.19 In a randomized superiority trial comparing high-dose (100 IU/kg) and standard-dose (50 IU/kg) heparin, the RAO rate was significantly lower in the high-dose group.20 Recent evidence suggests that a small dose of rivaroxaban, given orally after a transradial procedure, may decrease the occurrence of RAO at 1 month.21,22

Using the reverse Barbeau test, Sanmartin et al.23 found that 60% of patients had an absence of radial flow during compression. These observations led to the concept of nonocclusive hemostasis (patent hemostasis). In the PROPHET study,3 RAO was significantly less frequent in the group that underwent nonocclusive hemostasis than in the control group.

The duration of hemostatic compression has been studied in large, randomized trials.24-26 The authors concluded that compression duration was a strong predictor of RAO.

In a meta-analysis by Rashid et al.,27 the incidence of RAO after diagnostic coronary angiography was notably higher compared with percutaneous coronary intervention, possibly due to the use of higher anticoagulation doses during interventions.12 However, opposite findings have been reported by other studies.

In our sample, the mean radial diameter was 2.58 mm ± 0.39 and was significantly larger in men. Velasco et al.28 reported a mean arterial diameter of 2.22 ± 0.35 mm, while a Polish study found a mean diameter of 2.17 ± 0.53 mm for the right RA and 2.25 ± 0.43 mm for the left RA.29 The ulnar artery is also used in interventional cardiology,30 although there is no consensus on its size compared with the RA.

Autopsy studies of arterial anatomic variations of the upper extremity have reported frequencies between 4% and 18.5%.8 In the literature, the most frequent anatomic variation of the RA is high bifurcation. Yoo et al.31 reported a 2.4% incidence of high radial origin in 1191 Korean patients. Tortuosity of the RA frequently affects patients with high radial origin, possibly due to the elongated course of the RA predisposing it to tortuosity, which is considered one of the most common causes of procedural failure, along with radial spasm.32

Radioulnar loop is the most common cause of procedural failure with experienced operators.33 Angiographic evaluation of the radioulnar anastomosis is mandatory in such cases, as there is often a negotiable anastomosis between the radial and ulnar arteries.

In our study, radial spasm was the leading cause of procedural failure, occurring in 50% of the 14 patients who experienced such failures. Ruiz-Salmerón et al.34 found that RA anatomic variations were strongly associated with radial spasm in a multivariate analysis. The relationship between radial spasm and anatomic variations is mainly explained by the strong correlation with high radial origin and the radioulnar loop.

Study limitations

Since this study is a prospective registry and not a randomized trial, selection bias cannot be excluded. Our study represents a single-center experience with a limited number of patients, despite being one of the largest prospective registries of vascular ultrasound in radial catheterization to date. Among the other limitations of the study, we note the lack of standardized protocols for both heparin use and compression.

CONCLUSIONS

With the increasing number of transradial procedures and the greater age of patients undergoing these interventions, leading to more complex procedures, it is essential to maintain the patency of the RA for future access. Although predictors of RAO after cardiac catheterization have been identified, implementing preventive measures in practice remains a challenge. The main modifiable predictors associated with the risk of RAO are insufficient heparinization and occlusive hemostasis. Therefore, preventive strategies should primarily focus on addressing these 2 factors.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practices and was approved by the local ethics committee. All patients included in the study provided written informed consent, which is archived and available. Our study population included both sexes. Gender had no influence on the occurrence of radial occlusion.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence software was used in the preparation of this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors meet the criteria for authorship as defined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. M.S. Lounes, A. Meftah, C. Belhadi, K. Allal, H. Boulaam, A. Sayah, I. Hafidi, and E. Tebache contributed to the acquisition and analysis of data for this article. M.S. Lounes, A. Bedjaoui, A. Allali, and S. Benkhedda were responsible for the study design and the writing of the article. M.S. Lounes, A. Allali, and S. Benkhedda contributed to writing and critical revision of the content. All authors have read and approved the final version of the article and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, including the accuracy and integrity of all its parts.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Despite recommendations on the prevention of RAO in interventional cardiology, its incidence remains relatively high in some centers.

- Spontaneous recanalization of the artery may occur during follow-up.

- Permanent occlusion of the radial artery prevents any possibility of its further use (interventional procedures, dialysis, etc.)

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- RAO is not limited to the distal part of the artery and can affect the entire length of the vessel.

- Diagnosis of RAO should be confirmed using Doppler ultrasound, which remains the gold standard.

- The 2 independent modifiable predictors of RAO are the anticoagulation protocol and hemostasis technique.

- Anatomic variations of the RA may impact the procedure. A high origin of the RA is the most frequent, followed by radial tortuosities. After radial spasm, the radioulnar loop is the most common cause of procedural failure with experienced operators.

REFERENCES

1. Cruden NL, Teh CH, Starkey IR, Newby DE. Reduced vascular complications and length of stay with transradial rescue angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:670-675.

2. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

3. Pancholy SB, Coppola J, Patel T, Roke-Thomas M. Prevention of radial artery occlusion-patent hemostasis evaluation trial (PROPHET study):a randomized comparison of traditional versus patency documented hemostasis after transradial catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;72:335-340.

4. Uhlemann M, Möbius-Winkler S, Mende M, et al. The Leipzig prospective vascular ultrasound registry in radial artery catheterization:impact of sheath size on vascular complications. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2012;5:36-43.

5. Da Silva RL, Britto PF, Joaquim RM, et al. Clinical accuracy of reverse Barbeau test in the diagnosis of radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization. J Transcat Intervent. 2021;29:eA20200037.

6. Costa F, van Leeuwen MA, Daemen J, et al. The Rotterdam Radial Access Research:Ultrasound-Based Radial Artery Evaluation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Coronary Procedures. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:003129.

7. Uglietta JP, Kadir S. Arteriographic study of variant arterial anatomy of the upper extremities. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1989;12:145-148.

8. Rodríguez-Niedenführ M, Vázquez T, Nearn L, et al. Variations of the arterial pattern in the upper limb revisited:a morphological and statistical study, with a review of the literature. J Anat. 2001;199:547-566.

9. Bertrand OF. Acute forearm muscle swelling post transradial catheterization and compartment syndrome:prevention is better than treatment!Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:366-368.

10. Sadaka MA, Etman W, Ahmed W, et al. Incidence and predictors of radial artery occlusion after transradial coronary catheterization. Egypt Heart J. 2019;71:12.

11. Dousi M, Sotirakou K, Fatsi A. The Use of Acetylsalicylic Acid As A Measure of Prevention of Radial Artery Occlusion in Patients Who Perform Coronary Angiography with Tra Technique. J Radiol Clin Imaging. 2020;3:13-21.

12. Rashid M, Kwok CS, Pancholy S, et al. Radial Artery Occlusion After Transradial Interventions:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:002686.

13. Zankl AR, Andrassy M, Volz C, et al. Radial artery thrombosis following transradial coronary angiography:incidence and rationale for treatment of symptomatic patients with low-molecular-weight heparins. Clin Res Cardiol. 2010;99:841-847.

14. Bi XL, Fu XH, Gu XS, et al. Influence of Puncture Site on Radial Artery Occlusion After Transradial Coronary Intervention. Chin Med J (Engl). 2016;129:898-902.

15. Buturak A, Gorgulu S, Norgaz T, et al. The long-term incidence and predictors of radial artery occlusion following a transradial coronary procedure. Cardiol J. 2014;21:350-356.

16. Dahm JB, Vogelgesang D, Hummel A, et al. A randomized trial of 5 vs. 6 French transradial percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;57:172-176.

17. Saito S, Ikei H, Hosokawa G, Tanaka S. Influence of the ratio between radial artery inner diameter and sheath outer diameter on radial artery flow after transradial coronary intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv.1999;46:173-178.

18. Pancholy SB. Comparison of the effect of intra-arterial versus intravenous heparin on radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1083-1085.

19. Hahalis GN, Aznaouridis K, Tsigkas G, et al. Radial Artery and Ulnar Artery Occlusions Following Coronary Procedures and the Impact of Anticoagulation:ARTEMIS Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:005430.

20. Hahalis GN, Leopoulou M, Tsigkas G, et al. Multicenter Randomized Evaluation of High Versus Standard Heparin Dose on Incident Radial Arterial Occlusion After Transradial Coronary Angiography:The SPIRIT OF ARTEMIS Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2241-2250.

21. Liang D, Lin Q, Zhu Q, et al. Short-Term Postoperative Use of Rivaroxaban to Prevent Radial Artery Occlusion After Transradial Coronary Procedure:The RESTORE Randomized Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:011555.

22. Hammami R, Abid S, Jihen J, et al. Prevention of radial artery occlusion with rivaroxaban after trans-radial access coronary procedures:The RIVARAD multicentric randomized trial. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1160459.

23. Sanmartin M, Gomez M, Rumoroso JR, et al. Interruption of blood flow during compression and radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:185-189.

24. Politi L, Aprile A, Paganelli C, et al. Randomized clinical trial on short-time compression with Kaolin-filled pad:a new strategy to avoid early bleeding and subacute radial artery occlusion after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Interv Cardiol. 2011;24:65-72.

25. Dharma S, Kedev S, Patel T, et al. A novel approach to reduce radial artery occlusion after transradial catheterization:postprocedural/prehemostasis intra-arterial nitroglycerin. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv.2015;85:818-825.

26. Aminian A, Saito S, Takahashi A, et al. Impact of sheath size and hemostasis time on radial artery patency after transradial coronary angiography and intervention in Japanese and non-Japanese patients:A substudy from RAP and BEAT randomized multicenter trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92:844-851.

27. Sinha SK, Jha MJ, Mishra V, et al. Radial Artery Occlusion. Incidence, Predictors and Long-term outcome after TRAnsradial Catheterization:clinico-Doppler ultrasound-based study (RAIL-TRAC study). Acta Cardiol. 2017;72:318-327.

28. Velasco A, Ono C, Nugent K, et al. Ultrasonic evaluation of the radial artery diameter in a local population from Texas. J Invasive Cardiol. 2012;24:339-341.

29. Peruga JP, Peruga JZ, Kasprzak JD, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of forearm arteries in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention via radial artery access:results of one-year follow-up. Kardiologia Polska. 2015;73:502-510.

30. Knebel AV, Cardoso CO, Correa Rodrigues LH, et al. Safety and feasibility of transulnar cardiac catheterization. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35:268-272.

31. Yoo BS, Yoon J, Ko JY, et al. Anatomical consideration of the radial artery for transradial coronary procedures:arterial diameter, branching anomaly and vessel tortuosity. Int J Cardiol. 2005;101:421-427.

32. Pristipino C, Roncella A, Trani C, et al. Identifying factors that predict the choice and success rate of radial artery catheterisation in contemporary real world cardiology practice:a sub-analysis of the PREVAIL study data. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:240-246.

33. Louvard Y, Lefèvre T. Loops and transradial approach in coronary diagnosis and intervention. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51:250-252.

34. Ruiz-Salmerón RJ, Mora R, Vélez-Gimón M, et al. Radial artery spasm in transradial cardiac catheterization. Assessment of factors related to its occurrence, and of its consequences during follow-up. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005;58:504-511.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Distal radial access (DRA) for coronary procedures is currently recognized as an alternative to conventional transradial access, with documented advantages primarily related to access-related complications. However, widespread adoption of DRA as the default approach remains limited. Therefore, this prospective cohort study aimed to present our initial experience with DRA for coronary procedures in any clinical settings.

Methods: From August 2020 to November 2023, we included 1000 DRA procedures (943 patients) conducted at a single center. The study enrolled a diverse patient population. We recommended pre- and postprocedural ultrasound evaluations of the radial artery course, with ultrasound-guided DRA puncture. The primary endpoint was DRA success, while secondary endpoints included coronary procedure success, DRA performance metrics, and the incidence of access-related complications.

Results: The DRA success rate was 97.4% (n = 974), with coronary procedure success at 96.9% (n = 969). The median DRA time was 40 [interquartile range, 30-60] seconds. Diagnostic procedures accounted for 64% (n = 644) of cases, while 36% (n = 356) involved percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), including primary PCI in 13% (n = 128). Pre-procedure ultrasound evaluation and ultrasound-guided DRA were performed in 83% (n = 830) and 85% (n = 848) of cases, respectively. Access-related complications occurred in 2.9% (n = 29).

Conclusions: This study shows the safety and feasibility of DRA for coronary procedures, particularly when performed under ultrasound guidance in a diverse patient population. High rates of successful access and coronary procedure outcomes were observed, together with a low incidence of access-related complications. The study was registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NTC06165406).

Keywords: Vascular access. Distal radial artery. Coronary angiography. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. Doppler ultrasound. Access-related complications.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Actualmente, el acceso radial distal (ARD) para procedimientos coronarios es una alternativa al acceso radial convencional, con algunas ventajas descritas principalmente en términos de complicaciones relacionadas con el acceso. A pesar de la evidencia, pocos centros han establecido el ARD como acceso sistemático para procedimientos coronarios. El objetivo de esta cohorte prospectiva es presentar la experiencia inicial en nuestro centro con el ARD en pacientes con indicación de procedimientos coronarios en cualquier escenario clínico.

Métodos: Se incluyeron 1.000 procedimientos de ARD (943 pacientes) realizados en un único centro de agosto de 2020 a noviembre de 2023. El estudio fue realizado con pacientes en cualquier escenario clínico. Se recomendó la valoración por ultrasonido del trayecto de la arteria radial antes y después del procedimiento, así como la punción ecoguiada. El objetivo principal fue el éxito del ARD. Como objetivos secundarios se consideraron el éxito del procedimiento coronario, el desempeño del ARD y las complicaciones relacionadas con el acceso.

Resultados: El éxito del ARD fue del 97,4% (n = 974) y el éxito del procedimiento coronario fue del 96,9% (n = 969). El tiempo de acceso del ARD fue de 40 segundos [rango intercuartílico, 30-60]. Se realizaron procedimientos diagnósticos en el 64% (n = 644) e intervencionismo coronario percutáneo (ICP) en el 36% (n = 356), incluyendo ICP primario en el 13% (n = 128) de los pacientes. La valoración por ultrasonido antes del procedimiento se llevó a cabo en el 83% (n = 830) y la punción ecoguiada en el 85% (n = 848). La incidencia de complicaciones relacionadas con el acceso fue del 2,9% (n = 29).

Conclusiones: Este estudio muestra la viabilidad y la seguridad del ARD principalmente guiado por ultrasonido para los procedimientos coronarios en cualquier escenario clínico, con un alto porcentaje de éxito del acceso y de éxito del procedimiento, además de una baja incidencia de complicaciones relacionadas con el acceso. El estudio fue registrado en ClinicalTrials.gov (NTC06165406).

Palabras clave: Acceso vascular. Arteria radial distal. Coronariografía. Angioplastia coronaria transluminal percutánea. Ultrasonido Doppler. Complicaciones relacionadas con el acceso.

Abbreviations

CAG: coronary angiography. DRA: distal radial access. DRart: distal radial artery. PRart: proximal radial artery. TRA: transradial access.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, distal radial access (DRA) in the anatomical snuffbox for both noncoronary and coronary procedures is gaining popularity. Since its introduction by Babunashvili et al.,1 in 2011, several observational studies have validated the feasibility and safety of DRA,2-4 comparing it with conventional transradial access (TRA). DRA has shown advantages such as a lower incidence of radial artery occlusion (RAO) and shorter hemostasis time, with minimal access-related complications.5,6 The usefulness of ultrasound to guide DRA and evaluate access-related complications has also been described.7,8 Recent randomized trials comparing DRA with TRA have reported conflicting results regarding RAO incidence, crossover rates, and access times.9-11 Nevertheless, meta-analyses consistently support the benefits of DRA, albeit with a higher crossover rate.12-13 One of the limitations of most studies on DRA is the restricted inclusion of patients in emergent situations or complex percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), such as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); therefore, the feasibility of the approach in this context is somewhat scarce.2,9-11,14 Despite current evidence, the use of DRA as the default access for coronary procedures is still not widely implemented in most centers. Hence, this prospective single-center cohort aimed to present the experience of our first 1000 DRA in patients undergoing coronary procedures in any clinical settings.

METHODS

Population and study design

The Distal Radial Access for Diagnostic and Interventional Coronary Procedures in an all-comer population (DISTAL) registry is a prospective observational investigation aiming to assess the performance of DRA and compare clinical and procedural characteristics in a diverse population undergoing coronary procedures. This interim analysis presents our initial experience with DRA conducted at a single center. All DRA procedures performed by 4 experienced operators, previously proficient in TRA, were included in the study from August 2020 to November 2023.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (CEIC-2804) and was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed written consent before the procedure.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included patients aged 18 years and older undergoing diagnostic or therapeutic coronary procedures using DRA in any clinical setting. Patients with an unsuitable distal radial artery (DRart) assessed by ultrasound (non-permeable or diameter <1 .8 mm) were excluded, as were patients with no palpable pulse of DRart with such unsuitability characteristics. Additional exclusion criteria encompassed participation in other clinical trials, known allergy to iodinated contrast, inability to provide informed consent, and women of childbearing age without a negative pregnancy test. While the Barbeau test was recommended, it was not mandatory for inclusion.15

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the success of DRA and the main secondary endpoint was the success of the coronary procedure. Other secondary endpoints included DRA procedure time, total procedure duration, the incidence of radial artery spasm, exposure to ionizing radiation, patient comfort levels, hemostasis time, access-related complications, and the impact of ultrasound guidance on DRA performance. Detailed definitions of these endpoints are provided in the supplementary data.

Distal radial access technique

The DRA technique has been previously described,2,4,16-18 and is explained in detail in the supplementary data. Key aspects of interest included patient selection, the decision to use ultrasound-guided puncture19 (figure 1) vs blind with palpation puncture at the discretion of the operator, patient positioning for right (r) or left (l) DRA, the puncture technique itself, and the hemostasis procedure (figure 2).

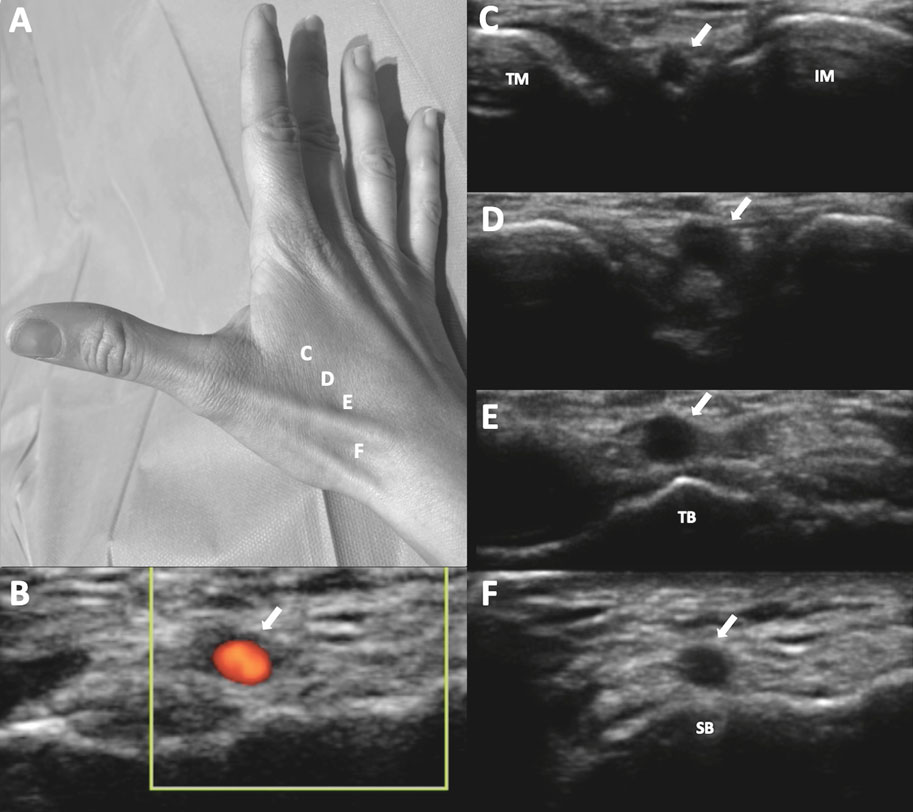

Figure 1. A: markers for ultrasound positioning in the anatomical snuffbox. B: patency of the distal radial artery (DRart) confirmed by color Doppler ultrasound. C-D: course of DRart between the metacarpal bones. E-F: recommended puncture sites of the DRart on a surface bone. IM, index metacarpal; SB, scaphoid bone; TB, trapezium bone; TM, thumb metacarpal.

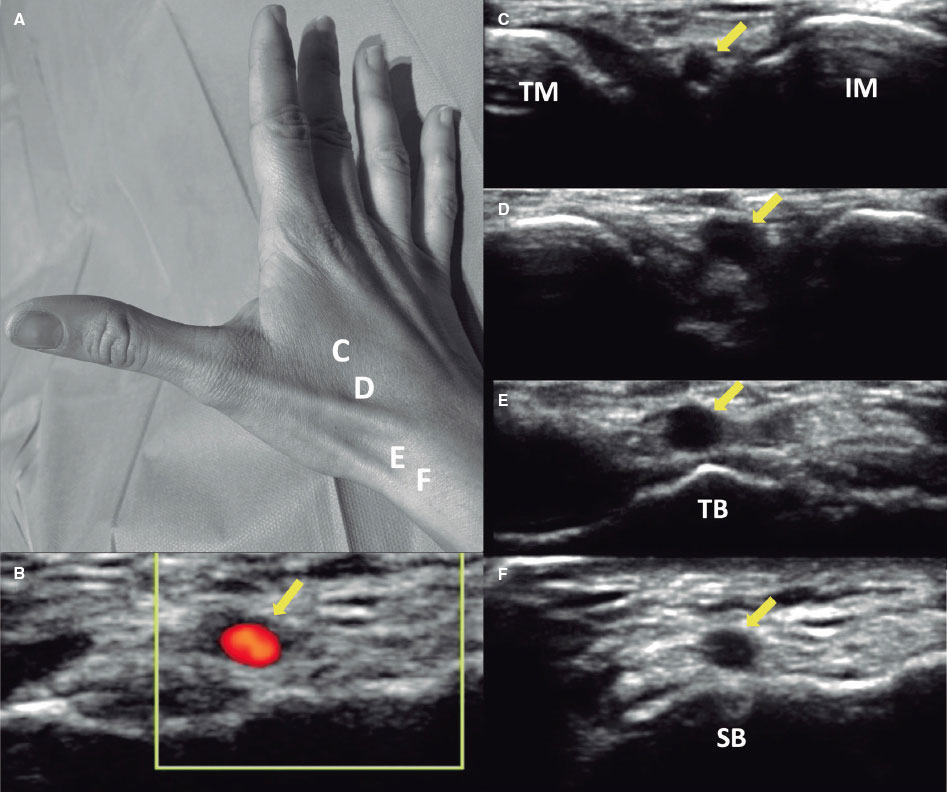

Figure 2. Distal radial access (DRA) technique. Position of the hand for A) right DRA and B) left DRA. C: ultrasound-guided DRA technique. D: blind with palpation DRA puncture. E: final position of the introducer sheaths on the right and left DRA. F: hemostasis devices in DRA.

Statistical analysis

Sample size and statistical power calculations were performed using the GRANMO calculator.20 A sample size of 1000 procedures was determined to provide a statistical power greater than 99% to detect a difference of 3% or more in the proportion of DRA success (primary endpoint) at our center, assuming an alpha risk of 1%. This calculation was based on a reference proportion from previous medical literature estimated around 95%.11,18,21

Categorical variables are presented as counts (percentages), while continuous variables were assessed for normal distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables are expressed as mean (standard deviation), and nonnormally distributed variables as median [interquartile range].

To evaluate the impact of the learning curve, comparisons were made among quartiles of the study period for variables including access failure, DRA time, total procedure time, and access-related complications. Analysis of variance or the Kruskal-Wallis test was used depending on the normality of the variable. Logistic regression analysis (logit command) was used with the first quartile as the reference to compare percentages among quartiles.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 20.0 software (IBM, United States) and STATA 12 (StataCorp, College Station, United States). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

RESULTS

From August 2020 to November 2023, a total of 1000 DRA procedures (943 patients) were performed. Table 1 shows the patients’ baseline clinical characteristics. The mean age was 68 years, and 29% of the patients were women. A total of 47% of the procedures were performed on an outpatient basis. In 35% of cases, the indication was acute coronary syndrome (13% STEMI).

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics

| Clinical characteristics | n = 1000 |

|---|---|

| Age, (years), mean (SD) | 68.1 (11.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 289 (28.9) |

| Weight, (kg), mean (SD) | 78.0 (14.8) |

| Height, (cm), mean (SD) | 167.9 (8.1) |

| Body mass index, (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 28.0 (4.5) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 735 (73.5) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 578 (57.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 353 (35.3) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 246 (24.6) |

| Family history of premature coronary heart disease, n (%) | 54 (5.4) |

| Previous peripheral artery disease, n (%) | 50 (0.5) |

| Previous stroke, n (%) | 41 (4.1) |

| Previous heart failure, n (%) | 252 (25.2) |

| GFR (mL/minute/1.73m2), mean (SD) | 72.4 (20.0) |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 27 (2.7) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SD) | 52.6 (16.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 170 (17.0) |

| OAC | |

| Acenocoumarin, n (%) | 170 (17.0) |

| Direct OAC, n (%) | 81 (8.1) |

| Previous CAG, n (%) | 251 (25.1) |

| Previous CABG, n (%) | 43 (4.3) |

| Previous PCI, n (%) | 218 (21.8) |

| Previous ischemic heart disease | |

| Previous STEMI, n (%) | 133 (13.3) |

| Previous NSTEMI, n (%) | 69 (6.9) |

| Previous CCS, n (%) | 53 (5.3) |

| CAG indication | |

| Chronic coronary syndrome, n (%) | 207 (20.7) |

| STEMI, n (%) | 128 (12.8) |

| NSTEMI, n (%) | 224 (22.4) |

| Staged PCI, n (%) | 60 (6.0) |

| Diagnostic, n (%) | 381 (38.1) |

| Preoperative CAG in patients with VHD, n (%) | 183 (18.3) |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 158 (15.8) |

| Ventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 24 (2.4) |

| Others, n (%) | 16 (1.6) |

| Outpatient coronary arteriography, n (%) | 470 (47) |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CAG, coronary angiography; CCS, chronic coronary syndrome; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; NSTEMI, non−ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; OAC, oral anticoagulation; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; VHD, valvular heart disease. Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

Table 2 presents the characteristics of the radial artery and the DRA procedure. High rates of preprocedure ultrasound evaluation and ultrasound-guided technique for DRA were noted (83% and 85%, respectively). Notably, the percentage of coronary procedures showing insufficient catheter length due to DRA was low (3.7%).

Table 2. Characteristics of the DRA procedure

| Procedure characteristics | n = 1000 |

|---|---|

| Preprocedure characteristics | |

| Arterial pulse strength scale | |

| Absent, n (%) | 12 (1.2) |

| Weak, n (%) | 167 (16.7) |

| Normal, n (%) | 652 (65.2) |

| Strong, n (%) | 169 (16.9) |

| Radial artery preprocedure ultrasound evaluation, n (%) | 830 (83.0) |

| Arterial tortuosity | |

| Radial, n (%) | 23 (2.3) |

| Subclavian, n (%) | 62 (6.2) |

| Calcified radial artery, n (%) | 26 (2.6) |

| Distal radial artery size, mm (SD) | 2.3 (0.3) |

| Proximal radial artery size, mm (SD) | 2.5 (0.4) |

| Depth of the distal radial artery, mm (SD) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| DRA technique | |

| CAG by the same DRA, n (%) | 57 (5.7) |

| Ultrasound-guided access, n (%) | 848 (84.8) |

| DRA side | |

| Right DRA, n (%) | 627 (62.7) |

| Left DRA, n (%) | 373 (37.3) |

| Introducer size | |

| 5 French, n (%) | 256 (25.6) |

| 6 French, n (%) | 744 (74.4) |

| Introducer sheath type | |

| Prelude Ideal (Merit Medical) Introducer Kit, n (%) | 950 (95.0) |

| Radifocus Introducer II Kit A (Terumo Corporation), n (%) | 50 (5.0) |

| Short length of the radial catheter | 37 (3.7) |

| Postprocedure arterial patency evaluation, n (%) | 907 (90.7) |

| Postprocedure puncture site bleeding, n (%) | 55 (5.5) |

|

CAG, coronary angiography; DRA, distal radial access. Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of coronary procedures, including the extent of coronary artery disease, types of procedures, and features of patients who underwent PCI. In general, 64% of the procedures were only diagnostic, while 36% included PCI.

Table 3. Characteristics of the coronary procedure

| Procedure characteristics | n = 1000 |

|---|---|

| Coronary disease extent | |

| One vessel, n (%) | 285 (28.5) |

| Two vessels, n (%) | 174 (17.4) |

| Three vessels, n (%) | 176 (17.6) |

| LMCAD, n (%) | 55 (5.5) |

| Coronary bypass graft, n (%) | 27 (2.7) |

| Characteristics of the coronary procedure | |

| Type of coronary procedures | |

| Diagnostic, n (%) | 644 (64.4) |

| PCI, n (%) | 356 (35.6) |

| Ambulatory PCI, n (%) | 90 (9.0) |

| PCI culprit lesion | |

| LMCAD, n (%) | 9 (0.9) |

| Left anterior descending artery, n (%) | 164 (16.4) |

| Circumflex coronary artery, n (%) | 95 (9.5) |

| Right coronary artery, n (%) | 100 (10.0) |

| Coronary bypass graft | 2 (0.2) |

| Specific techniques | |

| Wire-based intracoronary physiological assessment, n (%) | 57 (5.7) |

| Optical coherence tomography, n (%) | 21 (2.1) |

| Intravascular ultrasound, n (%) | 30 (3.0) |

| Guide catheter extension system, n (%) | 15 (1.5) |

| Rotational atherectomy, n (%) | 16 (1.6) |

| Cutting balloon, n (%) | 34 (3.4) |

| Intracoronary lithotripsy, n (%) | 8 (8.0) |

| Thrombus aspiration, n (%) | 81 (8.1) |

| Intracoronary perfusion catheter, n (%) | 7 (0.7) |

| Special PCI procedures | |

| Complex bifurcation, n (%) | 60 (6.0) |

| Chronic total occlusion, n (%) | 16 (1.6) |

| Volume of contrast, (mL), mean (SD) | 85.0 (53.1) |

| Heparin dose, (IU), median [IQR] | 5000 (3000-8500) |

|

LMCAD, left main coronary artery disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. |

|

Table 4 depicts the clinical endpoints. The DRA success rate was 97.4% and the coronary procedure success rate was 96.9%. The median access time was 40 (interquartile range [IQR], 30-60) seconds, and 4% of patients experienced radial artery spasm. The overall rate of access-related complications was low (2.9%).

Table 4. Clinical endpoints

| Clinical endpoints | n = 1000 |

|---|---|

| Primary endpoint | |

| DRA success, n (%) | 974 (97.4) |

| Coronary procedure success by DRA, n (%) | 969 (96.9) |

| Secondary endpoints | |

| Access time, (sec), median [IQR] | 40 (30-60) |

| Procedure time, (min), median [IQR] | 29.0 [17.3-45.0] |

| Radial artery spasm, n (%) | 44 (4.4) |

| DAP, (Gy.m2), median [IQR] | 32.7 [19.2-63.0] |

| Fluoroscopy time (min), median [IQR] | 4.6 [2.5-10.0] |

| VAS patient comfort for access, mean (SD) | 2.2 (0.6) |

| VAS patient comfort for hemostasis, mean (SD) | 2.1 (0.4) |

| Hemostasis time, (hour), mean, (SD) | 2.9 (1.1) |

| Access-related complications (all), n (%) | 29 (2.9) |

| Radial artery occlusion, n (%) | 10 (1.0) |

| Hematoma, n (%) | |

| Type I-a, n (%) | 11 (1.1) |

| Type I-b, n (%) | 1 (0.1) |

| Type II, n (%) | 1 (0.1) |

| Type III, n (%) | 1 (0.1) |

| Type IV, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Radial pseudoaneurysm, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Radial dissection, n (%) | 5 (0.5) |

| Arteriovenous fistula, n (%) | 0 (0) |

|

DAP, dose-area product; DRA, distal radial access; VAS, visual analog scale. Data are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation, or median [interquartile range]. |

|

Combined preprocedure ultrasound evaluation and ultrasound-guided puncture were performed in 82.8% of cases, with successful DRA achieved in 97.7% compared with 95.9% in those who did not undergo ultrasound guidance (P = .183). Based on the strength of the arterial pulse—absent, weak, normal, and strong—ultrasound-guided puncture was performed in 100%, 91%, 89.7%, and 45.5% of cases, respectively. Access time was longer with ultrasound-guided puncture than with nonultrasound-guided puncture (40 s [30-70] vs 35 s [30-45]; P < .001). The success of DRA in relation to the use of ultrasound-guided technique among all strengths of arterial pulse is detailed in table 1 of the supplementary data.

Arterial patency after removal of the hemostatic device was assessed in 907 patients (90.7%), revealing RAO in only 1% (n = 10).

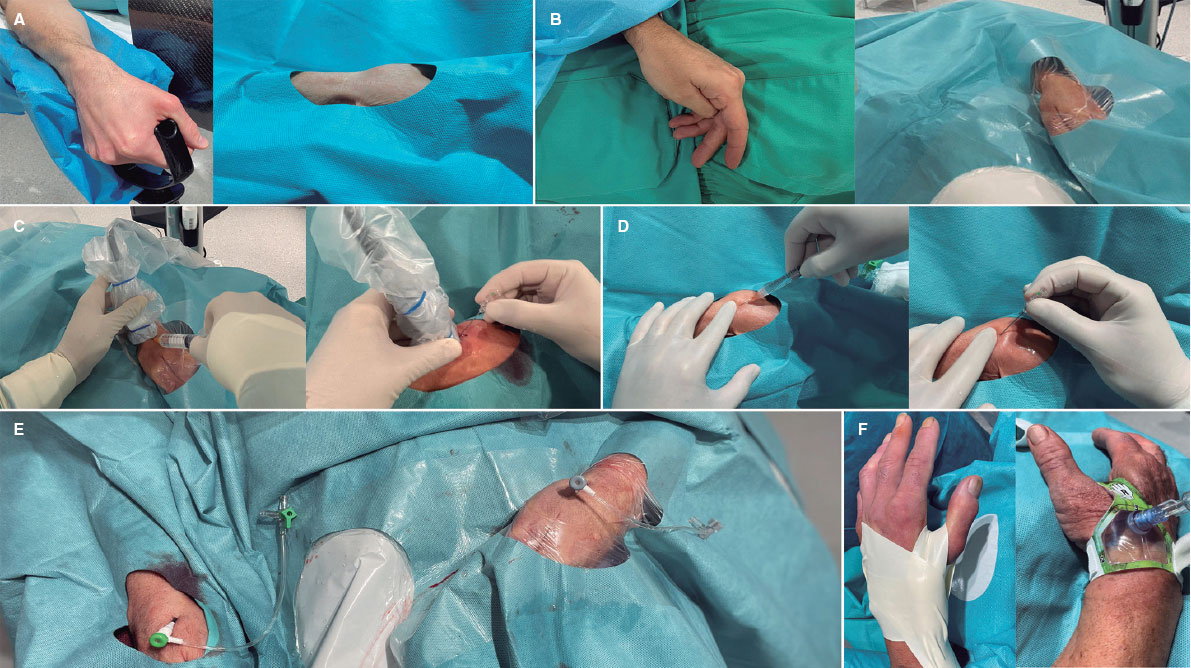

In the quartile analysis, a shift in the selection of DRA side was observed, with lDRA initially more commonly used, shifting to rDRA as the preferred access in later quartiles (figure 3A). DRA failure rates were low in all quartiles but decreased significantly from the third quartile onwards (figure 3B). Access time decreased significantly from the second quartile onwards and remained stable thereafter (figure 3C). However, no significant differences were found in total procedure duration between quartiles (figure 3D).

Figure 3. Stratified analysis by quartiles of patients over the study period. A: use of left vs right distal radial access (DRA). B: DRA access failure rate by quartile. C: DRA access time in seconds. D: total procedural time in minutes.

DISCUSSION

Using data from a large prospective registry of patients who underwent DRA for coronary procedures, with high use of ultrasound-guided techniques, our study showed that DRA achieves high rates of access and procedural success, coupled with a low incidence of access-related complications in an all-comer population.

The usefulness of ultrasound in the distal radial access technique

Understanding the anatomy of the anatomical snuffbox is crucial for successful DRA, and ultrasound serves as a valuable tool in achieving this, offering demonstrated advantages.5,16,17,22 In our study, preprocedure ultrasound evaluation and ultrasound-guided DRA techniques were used in most patients. In addition to assessing arterial diameters and evaluating calcification and tortuosity, ultrasound enabled us to exclude patients with unsuitable distal radial arteries. Overall, we found no significant differences between ultrasound-guided and nonultrasound-guided DRA, although the former was associated with longer access times. However, the role of ultrasound is particularly noteworthy in cases of weak or absent arterial pulses, which are often underrepresented in prior studies. The presence of a suboptimal arterial pulse can stem from various factors, including small DRart, hypotension, collateral blood supply, or depth of DRart.11 In our study, most patients with weak pulses underwent ultrasound-guided puncture, with a favorable trend toward successful access in those who did. However, in patients with normal to strong pulses, no differences in DRA success were found, and even prolongation of access time was observed with its use. Therefore, in this type of pulse, an ultrasound-guided puncture is probably not necessary.

Feasibility, safety, and technical issues in distal radial access

This study corroborates the previously reported advantages of DRA,3,9,10,12,13,18 such as a low rate of RAO, acceptable access time, short hemostasis time, and adequate patient comfort.

Furthermore, the absence of an increased risk of hand dysfunction after DRA has been demonstrated,23 even compared with TRA at 12 months of follow-up, documented by Al-Azizi et al.24 Here, we focus on controversial issues that may have hampered wider adoption of this technique, and our results may provide additional support for DRA.

High success rates of DRA in coronary procedures have been reported in numerous studies.2-4,17,18,25 In addition, recent clinical trials and meta-analyzes describe a higher crossover rate compared with TRA.9-13

In contrast to our results, trials comparing DRA with TRA have reported lower access success and longer puncture times.9-11 Conversely, our study demonstrates remarkably high success rates for DRA and coronary procedures, as well as shorter access time, consistent with registries in which DRA is the default approach among experienced operators, as shown by the largest registries published to date, the DISTRACTION and KODRA studies.2-4,18,21

The KODRA trial included 4977 DRA procedures from a Korean registry.21 The authors reported a DRA success rate of 94.4%, with a crossover rate of 6.7%. In contrast to our work, the use of ultrasound-guided puncture in KODRA was low (6.4%). Additionally, the authors found predictors of DRA failure, such as the presence of a weak pulse and limited operator experience (less than 100 cases).

The equivalence of rDRA and lDRA has previously been demonstrated, and contemporary studies use mainly rDRA.9-11,17 As in the first registries, which suggested a potential advantage of lDRA, we started our experience with lDRA but, based on operator comfort and preference, the use of the rDRA increased over time.

Although the feasibility and benefits of DRA over TRA in STEMI have been observed, the literature on the topic remains scarce.2,9-11 In our registry, all attempted DRA procedures in patients with STEMI were successful. However, the first DRA in STEMI was performed after the operators had surpassed the learning curve for the technique (up to case 320). Similarly, the use of DRA for complex PCI has been previously described.22,26,27 In our cohort, all complex PCI procedures were performed without crossover.

The puncture site in DRA, situated 5 cm distal to TRA, may lead to an inadequate catheter length in specific contexts (such as tall patients, dilated aorta, subclavian artery tortuosity, and the need for retrograde access to PCI for chronic total occlusions).28 We found a low incidence of short catheter length during DRA procedures, with only 1 crossover due to severe tortuosity of the subclavian artery.

DRA-related complications have been consistently reported to be low.2,9-11,18 Similarly, we found a very low rate of complications, the most common being type I-a hematoma. In our study, the incidence of in-hospital RAO was 1%.

The number of DRA procedures to overcome the learning curve and maintain a success rate above 94% is around 150 to 200.2,8 However, in our early experience, we achieved this percentage after the first 20 cases per operator.17 In this study, operators navigated the learning curve in the first quartile; however, success significantly improved to more than 99% in the last 2 quartiles, probably because DRA became the default access for coronary procedures among operators.

Limitations

First, this study was an interim analysis of the leading participating site and coordinator of the DISTAL registry (NTC06165406), conducted because substantial enrollment from other sites was lacking. Although the data cannot be fully extrapolated to other centers, recalculation of the sample size was considered sufficient to evaluate the results.

Second, patient enrollment was not consecutive because the decision to use DRA was at the operators’ discretion. Only one-third of coronary procedures during the study period used this approach. However, we included all patients in whom operators intended to use DRA in any clinical setting were included, with only 21 patients excluded due to DRart ≤1.8mm. Third, this was a descriptive cohort of DRA, without a comparison control group. Fourth, the scale used to assess the arterial pulse is subjective. However, this scale is widely used in routine clinical practice and has been used in multiple DRA studies. Finally, radial artery patency was not evaluated in 9.7% of the patients before discharge, and no evaluation was conducted at 1 month; therefore, the in-hospital rate of radial artery occlusion may be underestimated and no mid-term data are available on the patency of the DRart.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows the safety and feasibility of DRA primarily guided by ultrasound for coronary procedures in an all-comer population, with high rates of both access and procedural success, in addition to a very low rate of access-related complications.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our institution (CEIC-2804) and was conducted following the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave their informed written consent before the procedure.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Not used.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

K. Rivera and D. Fernández-Rodríguez conceived and designed the study. K. Rivera, D. Fernández-Rodríguez, M. García-Guimarães, J. Casanova-Sandoval, and J. L. Ferreiro analyzed data, and drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the treatment of patients, data acquisition and mining, and review and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. L. Ferreiro reports a) honoraria for lectures from Eli Lilly Co, Daiichi Sankyio, Inc, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bistol-Myers Squibb, Rovi, Terumo and Ferrer; b) consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly Co, Ferrer, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, Inc, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Biotronik; c) research grants from AstraZeneca. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Previous studies have demonstrated the safety and feasibility and safety DRA. Compared with TRA, DRA has several advantages, despite the high prevalence of crossover and controversial incidence of radial artery occlusion.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The results of this cohort show the safety and feasibility of DRA in an all-comer population throughout the spectrum of DRart pulses. Our study demonstrates that preprocedure ultrasound evaluation and the ultrasound-guided DRA technique help to achieve a low crossover rate, which is especially useful in patients with an unfavorable arterial pulse. According to our observations, DRA in urgent/emergent procedures and complex PCI is feasible and safe once the learning curve has been overcome and the operator is familiar with the technique.

REFERENCES

1. Babunashvili A, Dundua D. Recanalization and reuse of early occluded radial artery within 6 days after previous transradial diagnostic procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;77:530-536.

2. Lee JW, Park SW, Son JW, Ahn SG, Lee SH. Real-world experience of the left distal transradial approach for coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention:A prospective observational study (LeDRA). EuroIntervention. 2018;14:e995-e1003.

3. Oliveira MDP, Navarro EC, Kiemeneij F. Distal transradial access as default approach for coronary angiography and interventions. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2019;9:513-519.

4. Kiemeneij F. Left distal transradial access in the anatomical snuffbox for coronary angiography (ldTRA) and interventions (ldTRI). EuroIntervention. 2017;13:851-857.

5. Sgueglia GA, Di Giorgio A, Gaspardone A, Babunashvili A. Anatomic Basis and Physiological Rationale of Distal Radial Artery Access for Percutaneous Coronary and Endovascular Procedures. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2113-2119.

6. Lu H, Wu D, Chen X. Comparison of Distal Transradial Access in Anatomic Snuffbox Versus Transradial Access for Coronary Angiography. Heart Surg Forum. 2020;23:E407-E410.

7. Ghose T, Kachru R, Dey J, Khan WU, et al. Safety and Feasibility of Ultrasound-Guided Access for Coronary Interventions through Distal Left Radial Route. J Interv Cardiol. 2022;2022:2141524.

8. Roh JW, Kim Y, Lee OH, et al. The learning curve of the distal radial access for coronary intervention. Sci Rep. 2021;11:13217.

9. Tsigkas G, Papageorgiou A, Moulias A, et al. Distal or Traditional Transradial Access Site for Coronary Procedures:A Single-Center, Randomized Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:22-32.

10. Aminian A, Sgueglia GA, Wiemer M, et al. Distal Versus Conventional Radial Access for Coronary Angiography and Intervention:The DISCO RADIAL Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1191-1201.

11. Kozin´ski Ł, Orzałkiewicz Z, Da˛browska-Kugacka A. Feasibility and Safety of the Routine Distal Transradial Approach in the Anatomical Snuffbox for Coronary Procedures:The ANTARES Randomized Trial. J Clin Med. 2023;12:7608.

12. Ferrante G, Condello F, Rao SV, et al. Distal vs Conventional Radial Access for Coronary Angiography and/or Intervention:A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:2297-2311.

13. Barbarawi M, Barbarawi O, Jailani M, Al-Abdouh A, Mhanna M, Robinson P. Traditional versus distal radial access for coronary angiography:A meta-Analysis of randomized controlled trials. Coron Artery Dis. 2023;34:274-280.

14. Erdem K, Kurtogˇlu E, Küçük MA, Ilgenli TF, Kizmaz M. Distal transradial versus conventional transradial access in acute coronary syndrome. Turk Kardiyoloji Dernegi Arsivi. 2021;49:257-265.

15. Valgimigli M, Campo G, Penzo C, Tebaldi M, Biscaglia S, Ferrari R. Transradial coronary catheterization and intervention across the whole spectrum of allen test results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1833-1841.

16. Sgueglia GA, Lee BK, Cho BR, et al. Distal Radial Access:Consensus Report of the First Korea-Europe Transradial Intervention Meeting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:892-906.

17. Rivera K, Fernández-Rodríguez D, Casanova-Sandoval J, et al. Comparison between the Right and Left Distal Radial Access for Patients Undergoing Coronary Procedures:A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J Interv Cardiol. 2022;2022:7932114.

18. Oliveira MD, Navarro EC, Caixeta A. Distal transradial access for coronary procedures:A prospective cohort of 3,683 all-comers patients from the DISTRACTION registry. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2022;12:208-219.

19. Hadjivassiliou A, Kiemeneij F, Nathan S, Klass D. Ultrasound-guided access to the distal radial artery at the anatomical snuffbox for catheter-based vascular interventions:A technical guide. EuroIntervention. 2021;16:1342-1348.

20. Calculadora de tamaño muestral GRANMO. Available at:https://www.imim.cat/media/upload/arxius/granmo/granmo_v704.html. Accessed 25 Mar 2024.

21. Lee JW, Kim Y, Lee BK, et al. Distal Radial Access for Coronary Procedures in a Large Prospective Multicenter Registry:The KODRA Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:329-340.

22. Zong B, Liu Y, Han B, Feng CG. Safety and feasibility of a 7F thin-walled sheath via distal transradial artery access for complex coronary intervention. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:959197.

23. Sgueglia GA, Hassan A, Harb S, et al. International Hand Function Study Following Distal Radial Access:The RATATOUILLE Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:1205-1215.

24. Al-Azizi K, Moubarak G, Dib C, et al. Distal Versus Proximal Radial Artery Access for Cardiac Catheterization:1-Year Outcomes. Am J Cardiol. 2024;220:102-110.

25. Rivera K, Fernández-Rodríguez D, Bullones J, et al. Impact of sex differences on the feasibility and safety of distal radial access for coronary procedures:a multicenter prospective observational study. Coron Artery Dis. 2024;35(5):360-367.

26. Rivera K, Fernández-Rodríguez D, García-Guimarães M, Ramírez Martínez T, Casanova-Sandoval J. Intravascular ultrasound-guided percutaneous exclusion of a complicated coronary artery aneurysm presenting as ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2023;34:527-528.

27. Nikolakopoulos I, Patel T, Jefferson BK, et al. Distal Radial Access in Chronic Total Occlusion Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:Insights From the PROGRESS-CTO Registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2021;33:E717-E722.

28. Davies RE, Gilchrist IC. Back hand approach to radial access:The snuff box approach. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2018;19:324-326.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Drug-eluting balloons (DEB) are an established treatment option for in-stent restenosis (ISR). This study aimed to assess the safety and efficacy of a novel DEB in patients with ISR.

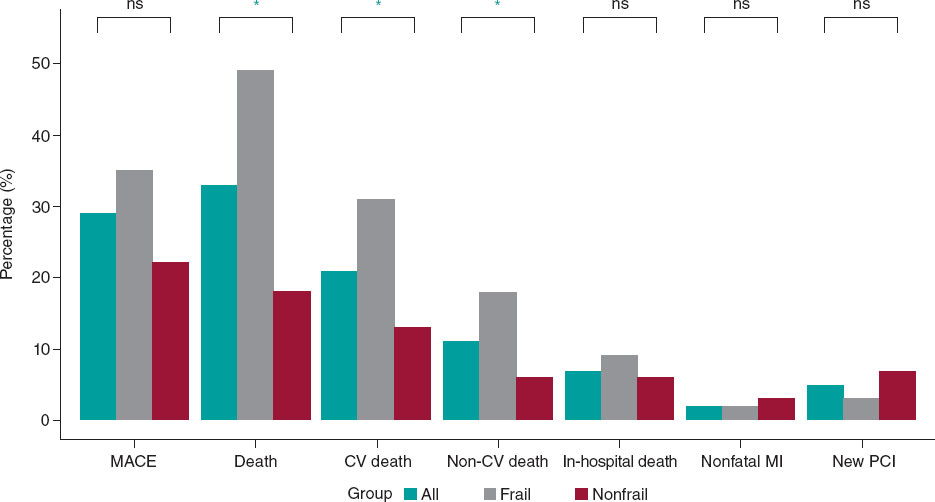

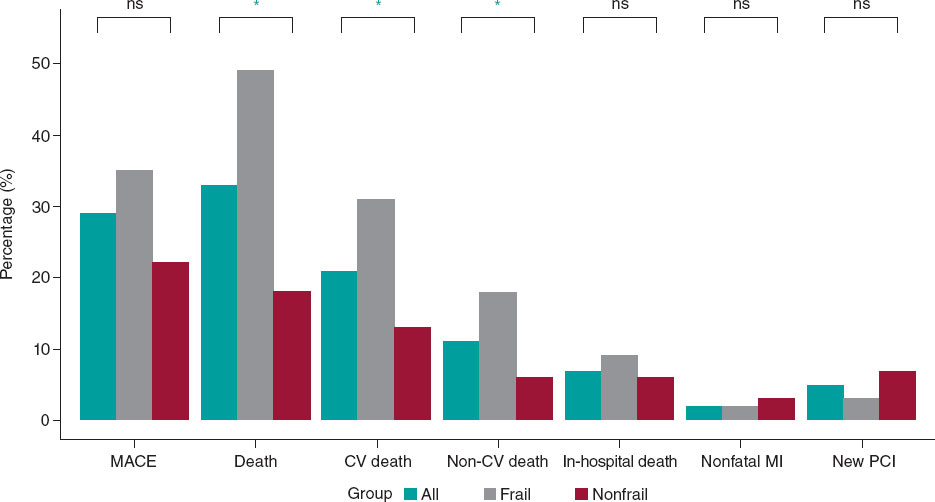

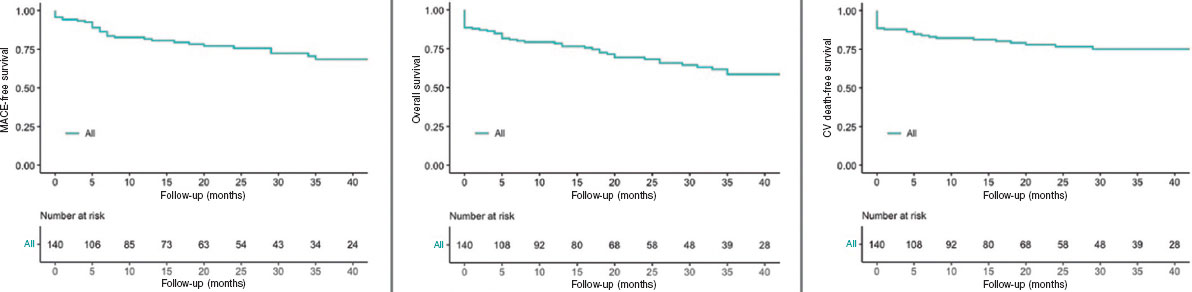

Methods: This prospective, single-center study enrolled a consecutive cohort of patients diagnosed with ISR who underwent coronary angioplasty with a new second-generation paclitaxel-eluting balloon. The 3 main endpoints were myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and target vessel revascularization. Baseline variables were collected, including patient and procedure characteristics. Follow-up data were collected through medical records or telephone contact.

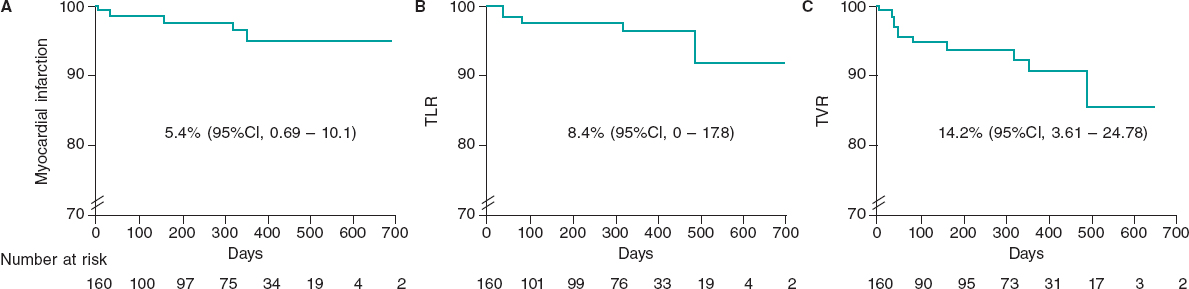

Results: The study included 160 consecutive patients with 206 treated lesions (mean age, 71.4 ± 14.9 years, 15.5% women) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with DEB for ISR. A total of 53.3% of patients had acute coronary syndrome. The average diameter of the treated vessel was 3.10 ± 0.7 mm. The DEB used had a mean diameter of 3.1 ± 0.6 mm and a mean length of 23.1 ± 6.8 mm. Predilatation was performed in 98% of the lesions, and a noncompliant balloon was used in 80%. Intracoronary imaging was used in 24% of cases. At the end of the procedure, 98.5% of patients had Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction flow grade 3, residual stenosis was > 30% in 3.4%, and dissection occurred in 1.4%. Bail-out stenting was required in 4.8% of patients. Mortality was nil during follow-up (maximum 768 days). The incidence of myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and target vessel revascularization were 5.4% (95%CI, 0.69-10.1), 8.4% (95%CI, 0-17.8), and 14.2% (95%CI, 3.61-24.78), respectively.

Conclusions: In this cohort of patients with ISR treated with DEB, we observed a low rate of adverse events in both the short- and mid-term. These results support the safety and efficacy of this new generation of DEB for treating ISR.

Keywords: In-stent restenosis. Drug-eluting balloon. Paclitaxel.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El balón farmacoactivo (BFA) es un tratamiento establecido para tratar la reestenosis intrastent (RIS). El objetivo de este estudio fue valorar la eficacia y la seguridad de un nuevo BFA en pacientes con RIS.

Métodos: Cohorte prospectiva, unicéntrica y consecutiva de pacientes con RIS tratados con angioplastia coronaria con un nuevo balón liberador de paclitaxel de segunda generación. Los 3 eventos principales del estudio fueron infarto de miocardio, revascularización de la lesión diana y revascularización del vaso diana. Se recogieron variables basales, incluidas las características del paciente y del procedimiento. Los datos referentes al seguimiento se obtuvieron de registros médicos o por contacto telefónico.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 160 pacientes consecutivos con 206 lesiones tratadas (71,4 ± 14,9 años, el 15,5% mujeres) que fueron tratados con una intervención coronaria percutánea con BFA debido a RIS. El 53,3% de los pacientes presentaban síndrome coronario agudo. El diámetro medio del vaso tratado fue de 3,1 ± 0,7 mm. El diámetro y la longitud del BFA empleado fueron de 3,1 ± 0,6 mm y 23,1 ± 6,8, respectivamente. El 98% de las lesiones se predilataron y en el 80% se empleó un balón no distensible. El 24% de las angioplastias fueron guiadas por imagen intracoronaria. El 98,5% de los pacientes presentaban un flujo Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction de grado 3 al final de la angioplastia. Hubo estenosis residual > 30% en el 3,4%, y el 1,4% presentaron disección. El 4,8% de los pacientes requirieron stent de rescate. Al finalizar el seguimiento (máximo 768 días), ningún paciente había fallecido. Las incidencias de infarto de miocardio, de revascularización de la lesión diana y de revascularización del vaso diana fueron del 5,4% (IC95%, 0,69-10,1), el 8,4% (IC95%, 0-17,8) y el 14,2% (IC95%, 3,61-24,78), respectivamente.

Conclusiones: En esta cohorte de pacientes con RIS tratados con BFA se observa una baja tasa de eventos clínicos adversos, tanto a corto como a mediano plazo. Estos resultados respaldan la eficacia y la seguridad de esta nueva generación de BFA para pacientes con RIS.

Palabras clave: Reestenosis intrastent. Balón farmacoactivo. Paclitaxel.

Abbreviations

DEB: drug-eluting balloon. ISR: in-stent restenosis. TLR: target lesion revascularization. TVR: target vessel revascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR) represent a clinical challenge.1 Evidence indicates that these patients are at increased risk of recurrent symptoms, myocardial infarction, and repeated coronary revascularizations.2 The use of drug-eluting balloons (DEB) is a novel alternative therapeutic strategy in patients with ISR.1,3,4 The effect of DEBs in coronary angioplasty is based on the rapid and uniform transfer of antiproliferative drugs into the vessel wall using a single balloon through a lipophilic matrix without the need for permanent implants.5

Over time, new DEB technologies are developed and launched onto the market. The Essential Pro (iVascular, Spain) is a paclitaxel-eluting balloon catheter with advancements to enhance catheter pushability and drug delivery. We believe it is essential to report outcomes from real-world settings. In this study, we report our findings on the safety and efficacy of this new DEB in patients with ISR.

METHODS

Design and population

This prospective, single-center study included a cohort of consecutive patients undergoing DEB angioplasty with the Essential Pro. The center treating these patients performs more than 1500 percutaneous coronary interventions per year. The 2 inclusion criteria for this analysis were: a) use of an Essential Pro DEB and b) its application for ISR treatment. ISR was defined as stenosis more than 50% within the stented segment, and treatment was indicated according to the treating physician’s judgment.6 The use of the Essential Pro DEB was prioritized during the study period to treat all eligible patients for DEB angioplasty, while other DEB devices were rarely used due to inventory constraints. There were no exclusion criteria. Patients may have undergone stent coronary angioplasty of other lesions in the same or a different setting.

Drug-eluting balloon characteristics

The Essential Pro is a paclitaxel-eluting balloon with a uniform 3 μg/mm2 eluting formulation, consisting of paclitaxel (80%) and a biocompatible amphiphilic excipient (20%).7 The balloon incorporates the proprietary TransferTech technology (iVascular, Spain), which is based on the ultrasonic deposition of nanodrops, followed by a dry-off process, resulting in a homogeneous microcrystalline drug coating. This allows more uniform and complete treatment of the vessel with the antiproliferative drug. The microcrystalline structure, coupled with the lipophilic nature of both paclitaxel and the excipient, facilitates drug transfer within 45 to 60 seconds. The Essential Pro balloon has been designed with a smooth transition and a very low tip profile of 0.016 inches, enhancing flexibility, trackability, and device crossability. The balloon is compatible with 5-Fr sheaths in all available diameters.

Procedures