Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Coronary lesions with stent overlapping are associated with higher neointimal proliferation that leads to more restenosis. Furthermore, the tapering of coronary arteries is a major challenge when treating long coronary lesions. This study attempted to assess the safety and clinical level of performance of long nontapered sirolimus-eluting coronary stent systems (> 36 mm) to treat long and diffused de novo coronary lesions in real-world scenarios.

Methods: This was a prospective, non-randomized, multicentre study that included 696 consecutive patients treated with the long nontapered BioMime sirolimus-eluting coronary stent system in long and diffused de novo coronary lesions. The safety endpoint was major adverse cardiovascular events defined as a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, clinically driven target lesion revascularization, stent thrombosis, and major bleeding at the 12-month follow-up.

Results: Of a total of 696 patients, 38.79% were diabetic. The mean age of all the patients was 64.6 ± 14 years, and 80% were males. The indication for revascularization was acute coronary syndrome in 63.1%. A total of 899 lesions were identified out of which 742 were successfully treated with long BioMime stents (37 mm, 40 mm, 44 mm, and 48 mm). The cumulative incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events was 8.1% at the 12-month follow-up including cardiac death (2.09%), myocardial infarction (1.34%), and total stent thrombosis (0.5%).

Conclusions: This study confirms the safety and good performance of long nontapered BioMime coronary stents to treat de novo coronary stenosis. Therefore, it can be considered a safe and effective treatment for long and diffused de novo coronary lesions in the routine clinical practice.

Keywords: Coronary angioplasty. Drug-eluting stent. Nontapered stents.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Las lesiones coronarias largas y difusas, cuando se tratan percutáneamente, requieren a menudo superposición de los stents, que se asocia a una mayor tasa de reestenosis. Por otro lado, el adelgazamiento progresivo de las arterias dificulta el tratamiento de las lesiones largas. En este estudio se analizan la seguridad y la eficacia clínica de los stents liberadores de sirolimus largos no cónicos (> 36 mm) para el tratamiento de lesiones largas de novo en un escenario real.

Métodos: Estudio prospectivo, no aleatorizado, multicéntrico, con 696 pacientes consecutivos con implantación de stent BioMime largo no cónico para el tratamiento de lesiones coronarias de novo largas y difusas. El criterio de valoración de seguridad fueron los eventos adversos cardiovasculares mayores en el seguimiento, definidos como la combinación de muerte cardiaca, infarto de miocardio, necesidad de nueva revascularización en la misma lesión guiada por la clínica, trombosis del stent o hemorragia mayor a los 12 meses.

Resultados: De los 696 pacientes incluidos, el 38,79% eran diabéticos. La edad media fue de 64,6 ± 14 años y el 80% eran varones. La indicación de revascularización fue un síndrome coronario agudo en el 63,1%. Se identificaron 899 lesiones, de las que 742 se trataron con éxito con stents BioMime (37-40-44-48 mm). La incidencia acumulada de eventos adversos cardiovasculares mayores fue del 8,1% a los 12 meses, con un 2,09% de muertes de causa cardiaca, un 1,34% de infartos de miocardio y un 0,5% de trombosis del stent.

Conclusiones: El presente estudio confirma la seguridad y el buen perfil clínico a 12 meses del stent BioMime largo no cónico para el tratamiento de lesiones coronarias de novo largas y difusas, por lo que debe considerarse un tratamiento seguro y eficaz para este tipo de lesiones en la práctica clínica habitual.

Palabras clave: Angioplastia coronaria. Stents farmacoactivos. Stents largos no cónicos.

Abbreviations

CAD: coronary artery disease. DES: drug-eluting stent. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. SES: sirolimus-eluting stent. ST: stent thrombosis.

INTRODUCTION

The most widely used strategy to treat coronary artery disease (CAD) is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent implantation, particularly with the current generation of drug-eluting coronary stents (DES), since their distinctive features improve the clinical outcomes of PCI.1 However, the treatment of long and diffused coronary lesions remains challenging, especially in long lesions in tapered coronary arteries where variations in vessel diameter may require the implantation of > 1 stent per lesion.2,3

The use of either multiple stents or a single long stent are the most common treatment strategies for long and diffused lesions in tapered arteries. Both approaches may be associated with clinical failure due to the potential risk of mechanical mismatch of the stent size.1,4,5 Multiple short overlapping stents with variable diameters are often implanted to adequately match the size of long tapered lesions. Because of potential discrepancies regarding diameters when using long nontapered stents, a proximal optimization technique may be used to reconstruct the vessel natural geometry. However, this solution does not come without problems such as stent fracture due to vessel rigidity, restenosis due to a higher vascular injury, delayed healing, very late stent thrombosis (ST), vessel aneurysm, side branch jailing, higher treatment cost, overuse of antirestenotic drugs, and increased exposure to radiation and contrast media, and death or myocardial infarction.6,7

A single long BioMime (Meril Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd., India), an ultrathin biodegradable polymer coated sirolimus-eluting coronary stent (SES) system, is often enough to treat long and diffused lesions. Thus, the local arterial walls can be saved from overexposure to drug/metal avoiding any potential associated adverse events at the follow-up like delayed healing, perioperative myocardial infarction (MI), risk of target lesion revascularization, and very late ST. The aim of this study was to evaluate the safety and level of performance of the long nontapered BioMime SES system (37 mm, 40 mm, 44 mm, 48 mm) in consecutive real-world patients with long and diffused de novo coronary lesions.

METHODS

Study design and population

This was a prospective, non-randomized, multicentre study that included a total of 696 consecutive patients (aged ≥ 18 years) from 14 clinical centers across Spain. All the study investigators are listed in the appendix of this article.

All consecutive patients included had been treated of long and diffuse de novo coronary lesions through the implantation of, at least, 1 long nontapered BioMime system (37 mm, 40 mm, 44 mm, 48 mm). The study was conducted in observance of the privacy policy of each research center including its rules and regulations for the appropriate use of data in patient-oriented research. This study was also conducted in observance of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the ethics committee. Written informed consents were obtained from all the participants before the procedure.

Study device and procedure

The BioMime is a biodegradable polymer coated SES system with different lengths available to treat long and diffused coronary lesions. It uses an ultra-thin strut (65 µm), and a cobalt-chromium platform that has a unique hybrid design of open and closed cells with uniformly thin coating (2 µm) of bioabsorbable polymers, PLLA (poly-L-lactic acid), and PLGA (poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid). The stent elutes sirolimus (1.25 µg/mm2) between 30 and 40 days after implantation. The currently available long lengths of BioMime are 37 mm, 40 mm, 44 mm, and 48 mm. The device is CE marked.

The PCI was performed according to the standard treatment guidelines and followed by each participant center. Predilatation and postdilatation were left to the operator’s discretion though postdilatation was recommended per protocol.

Preoperatively, a 300 mg loading dose of aspirin plus a second anti-platelet agent (clopidogrel, ticagrelor, or prasugrel according to the clinical settings and operator’s preference) were administered in all the consecutive patients included.

Postoperatively, all patients were administered a 12-month course of dual antiplatelet therapy plus aspirin (75 mg to 100 mg once a day) indefinitely beyond the first year. A 1.6- and 12-month clinical follow-up was conducted after the index procedure, as required, and based on symptoms.

Endpoints and definitions

The safety endpoints were the occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at the 1-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up after the index procedure. MACE was defined as a composite of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, clinically driven target lesion revascularization, ST, and major bleeding.

MI was defined as the development of new pathological Q waves on the electrocardiogram or elevated creatinine kinase (CK) levels ≥ 2 times the upper limit of normal with elevated CK-MB levels in the absence of new pathological Q waves or new ischemic symptoms (eg, chest pain or shortness of breath).8 Cardiac death was defined as any deaths resulting from AMI, sudden cardiac death, heart failure mortality or stroke. Clinically driven target lesion revascularization was defined as a new PCI performed on the target lesion or coronary artery bypass graft of the lesion in the previously treated segment or within the 5 mm proximal or distal to the stent site or edge of DES inflation. ST was classified based on the definitions established by the Academic Research Consortium.9 Moderate-to-severe bleeding events were defined according to the GUSTO (Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Arteries) criteria. Procedural success was defined as a successful PCI without in-hospital major clinical complications including death, MI, and clinically driven target lesion revascularization. Device success was defined as the deployment of the study stent at the intended target lesion attaining final residual stenosis < 30% of the target lesion estimated both angiographically and through visual estimation.

Statistical analysis

Since there is no intervention, to study this cohort of patients we thought that the best method was to perform a descriptive analysis for an objective, comprehensive, and informative study of data. A a descriptive statistical analysis of the relevant variables was performed after collecting data. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical software platform. Measures of central tendency such as means summarize the level of performance of a group of scores while measures of variability describe the spread of scores among the participants. Both are important to understand the behavior of this cohort. One provides information on the level of performance, and the other tells us how consistent that performance is. Categorical data were expressed as frequency and percentages. No further models were conducted as the idea of this paper was to describe a group of patients, not to compare groups or search for significant inter-group differences.

RESULTS

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

The data of 696 consecutive patients (742 BioMime stents implanted, 157 different stents) were collected in the study that mostly included males (80.1%). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients are shown on table 1. The patients’ mean age was 64.6 ± 14 years. Conventional risk factors for CAD in the study population were diabetes mellitus (39%), hypertension (67.2%), dyslipidemia (64.8%), and active smoking (26.44%). The clinical status at admission is shown on table 1. Most patients (63.39%) had acute coronary syndrome.

Table 1. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

| Patients | N = 696 |

|---|---|

| Patients, demographics | |

| Age, years | 64.6 ± 14 |

| Male | 556 (80.1) |

| Baseline past medical history | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 271 (38.79) |

| Hypertension | 466 (66.80) |

| Dyslipidemia | 452 (64.80) |

| Active smoker | 180 (26.44) |

| Previous CABG | 57 (8.54) |

| Previous PCI | 223 (32.07) |

| Vascular peripheral disease | 69 (10.64) |

| Previous MI | 181 (25.63) |

| Cardiac status at the index procedure | |

| Stable angina | 254 (36.49) |

| Unstable angina | 29 (4.16) |

| STEMI | 227 (32.61) |

| NSTEMI | 186 (26.72) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction < 30% | 181 (26) |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

Lesion and procedural characteristics

Out of a total of 899 lesions identified in 696 consecutive patients, 742 long and diffused de novo type C coronary lesions (1.07 lesions per patient) were successfully treated with long BioMime stents. No other stents were needed to treat the lesion initially handled with a long BioMime device. A total of 157 other lesions were treated with 157 different stents. Therefore, no overlapping was needed in any of the lesions treated with a long BioMime device. A total of 40% of the patients had 1-vessel disease, 37% 2-vessel disease and 23% of the patients had 3-vessel disease. The left anterior descending coronary artery followed by the right coronary artery were the main arteries treated. In 3.8% of the cases BioMime implantation involved the left main coronary artery. The mean length of the implanted BioMime SES system was 43.8 mm along with an average diameter of 3.1 mm. The immediate procedural and device success rates were 99.7% and 100%, respectively. The procedural variables are shown on table 2 and table 3.

Table 2. Lesion and procedural characteristics

| Patients | N = 696 |

|---|---|

| Total no. of lesions treated with the BioMime Morph SES system | 742 |

| Total no. of lesions treated with other stents | 157 |

| BioMime target lesion location | |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | |

| Proximal LAD | 146 (21.40) |

| Mid LAD | 216 (30.80) |

| Distal LAD | 28 (4.50) |

| Diagonal | 11 (1.60) |

| Right coronary artery | |

| Proximal RCA | 174 (25.10) |

| Mid RCA | 257 (36.80) |

| Distal RCA | 97 (14.10) |

| Left circumflex artery | |

| Proximal LCX | 56 (8.20) |

| Mid LCX | 90 (12.90) |

| Distal LCX | 28 (4.10) |

| Left main coronary artery | 26 (3.80) |

| Diseased vessel | 1.84 ± 0.78 |

|

LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery; SES, sirolimus-eluting stent. Data are expressed as no. (%). |

|

Table 3. BioMime sirolimus-eluting stent system characteristics

| Stent lenght (mm) | |

| 37 | 100 |

| 40 | 189 |

| 44 | 128 |

| 48 | 325 |

| Average stent length (mm) | 43.80 |

| Stent diameter (mm) | |

| 2.25 | 42 |

| 2.5 | 153 |

| 2.75 | 84 |

| 3 | 263 |

| 3.5 | 185 |

| 4 | 13 |

| 4.5 | 2 |

| Maximum pressure | |

| Predilatation | 298 (86) |

| Postdilatation | 376 (54) |

| Maximum pressure | 14.6 ± 3.2 |

| Average stent diamenter used (mm) | 3.1 |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%). |

|

Clinical outcomes at follow-up

Clinical follow-up was completed in 96.12% of the patients included at the 12-month follow-up. A total of 3.88% out of 696 patients were lost to follow-up after 12 months.

The cumulative incidence of MACE at the 1-, 6-, and 12-month follow-up was 2.2%, 6.6%, and 8.1%, respectively. The individual MACE at the follow-up are shown on table 4. The rates of cardiac death were 0.59% and 2.09% after 1 month and 1 year, respectively.

Table 4. MACE at the follow-up

| % of patients | MACE | |

|---|---|---|

| Follow-up | ||

| 1 month | 682 (97.99) | 13 (2.2) |

| 6 to 9 months | 675 (97.27) | 44 (6.57) |

| 12 months | 668 (96.12) | 53 (8.1) |

| MACE | ||

| Bleeding at 1-M | 20 (0.29) | |

| Death at 1-M | 41 (0.59) | |

| MI at 1-M | 41 (0.59) | |

| Bleeding at 12-M | 5 (0.75) | |

| Death at 12-M | 13 (2.09) | |

| MI at 12-M | 9 (1.34) | |

| Total ST at 12-M | 3 (0.50) | |

|

MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; M, month; MI, myocardial infarction; ST, stent thrombosis. Data are expressed as no. (%). |

||

DISCUSSION

In the current study, the long nontapered BioMime SES system proved its safety and level of performance in consecutive real-world patients with long and diffused de novo coronary lesions. Despite the all-comers inclusion criteria defining a high-risk population, and the anatomical need for a long stent, procedural (99.7%) and device (100%) success were achieved and the clinical follow-up was quite favorable.

Studies have shown that the dimensions of coronary arteries taper naturally along with their length. They observed that 23% of the arteries had ≥ 1 mm taper and 19% arteries a 0.5 mm to 0.99 mm taper.10 Stent sizing is critical for a successful PCI regarding the treatment of long tapered lesions. Stent oversizing (stents that are larger in diameter compared to the healthy artery) may induce pathological stress on the arterial wall, aneurysm formation, late ST, and even late perforations. Stent undersizing, on the other hand, (stents that are smaller in diameter compared to the healthy artery) may lead to ST due to stent malapposition.11 Consistent with this, tapered stents were developed to potentially minimize clinical failure and maximize clinical benefits in these patients. This fact may be due to the specific design of the BioMime stents.

Ultrathin struts facilitate navegability, flexibility, and conformability of the vessel geometry while maintaining an excellent radial force. In addition, the open cell design throughout the entire body of the stent favors a less stiff device that follows more closely the tapered contour of the artery resulting in less arterial wall stress. Compliant stents should be considered for tapered artery applications, perhaps even to avoid the need for tapered stents, at least up to 48 mm length, as shown in our data.12-16

The use of long coronary stents (≥ 30 mm), but not as long as the lesions treated in this registry, to treat long and diffuse native vessel disease, saphenous vein graft disease, and long coronary dissections is associated with a reasonable procedural success rate and acceptable early and intermediate-term clinical outcomes.17 The treatment of very long CAD showed similar target lesion faliure at the 2-year follow-up for single DESs compared to overlapped DESs.18 Our results suggest that both strategies are reasonable therapeutic options for patients with diffuse CAD. However, DES overlap occurs in > 10% of the patients treated with PCI in the routine clinical practice, and has been associated with impaired angiographic and long-term clinical outcomes including death or myocardial infarction.19 In addition, the development of risk areas for malapposition with a single stent is significantly lower compared to overlapping stents. In cases where stent overlap cannot be avoided, deployment strategies should be optimized or new stent designs considered to reduce the risk of restenosis.20 A single stent strategy is often more cost-effectiveness, and involves the administration of fewer contrast and fewer balloons. New designs of very long stents allow us not only to treat increasingly complex lesions, but also to simplify the procedure, and reduce the number of stents used with very favorable results, at least, similar to those obtained with overlapping stents.21 Former studies have confirmed the safety and level of performance of the BioMime Morph, a very long tapered stent (60 mm) that can be considered the treatment of choice for very long and diffused tapered de novo coronary lesions in the routine clinical practice.22 However, in long lesions treated with single stents of up to 48 mm in length, our results suggest that nontapered stents give very good clinical results.

Limitations

One limitation may be the follow-up period that may not be enough to determine the long-term safety and level of performance of long BioMime SES system in patients with long and diffused de novo coronary lesions.

CONCLUSIONS

This study confirmed the favorable procedural and device success, and the optimal safety outcomes reported at the follow up, of the long nontapered BioMime SES system, up to 48 mm length, in real-world patients with long and diffused de novo coronary lesions.

FUNDING

The current study was partially funded by Palex Medical, and Meril (data collection, web design, and ethical committee).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

E. Domingo contributed to the study design, database completion, clinical follow-up, data analysis, and manuscript writing. J. Guindo contributed to the study design. R. Calviño Santos, J. Antoni Gomez, X. Carrillo, J. Sánchez, L. Andraka, A. Torres, J. Casanova-Sandoval, R. Ocaranza Sanchez, J. León Jiménez, J.F. Muñoz, R. Trillo Nouche, and M. Fuertes contributed to the database completion, and clinical follow-up. I. Otaegui contributed to the database completion, data analysis, and clinical follow-up. B. García del Balnco contributed to the study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

APPENDIX 1: STUDY INVESTIGATORS

-

Gerard Marti Aguasca. Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Vicenç Serra García. Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Servi- cio de Cardiología.

-

Bernat Serra Creus. Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Ser- vicio de Cardiología.

-

Neus Bellera Gotarda. Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron, Servi- cio de Cardiología.

-

Jorge Salgado Fernández. Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Montserrat Gracida Blancas. Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Lara Fuentes Castillo. Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Eduard Fernández-Nofrerias, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Oriol Rodríguez-Leor. Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Omar Abdul Jawad Altisent. Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Gabriel Galache. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Rosario Hortas. Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Eduard Bosch. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Daniel Valcarcel. Parc Taulí Hospital Universitari, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Maite Alfageme. HUA – Txagorritxu, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Merche Sanz. HUA – Txagorritxu, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Melisa Santás Álvarez. Hospital Lucus Augusti, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Diego López Otero. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago – CHUS, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Juan Carlos Sanmartin Pena. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago -CHUS, Servicio de Cardiología.

-

Ana Belén Cid Álvarez. Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago -CHUS, Servicio de Cardiología.

REFERENCES

1. Tan CK, Tin ZL, Arshad MKM, et al. Treatment with 48-mm everolimus eluting stents:Procedural safety and 12-month patient outcome. Herz. 2019;44:419-424.

2. Roach MR, MacLean NF. The importance of taper proximal and distal to Y-bifurcations in arteries. Front Med Biol Eng. 1993;5:127-133.

3. Zubaid M, Buller C, Mancini GB. Normal angiographic tapering of the coronary arteries. Can J Cardiol. 2002;18:973-980.

4. Sgueglia GA, Belloni F, Summaria F, et al. One-year follow-up of patients treated with new-generation polymer-based 38 mm everolimus-eluting stent:the P38 study. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:218-224.

5. Timmins LH, Meyer CA, Moreno MR, Moore JE, Jr. Mechanical modeling of stents deployed in tapered arteries. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:2042-2050.

6. Ellis SG, Holmes DR. Strategic approaches in coronary intervention. 2006:Lippincott Williams &Wilkins. P. 299-304.

7. Raber L, Juni P, Loffel L, et al. Impact of stent overlap on angiographic and long-term clinical outcome in patients undergoing drug-eluting stent implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1178-1188.

8. Mendis S, Thygesen K, Kuulasmaa K, et al. World Health Organization definition of myocardial infarction:2008- 09 revision. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:139-146.

9. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials:a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344-2351.

10. Banka VS, Baker HA, 3rd, Vemuri DN, Voci G, Maniet AR. Effectiveness of decremental diameter balloon catheters (tapered balloon). Am J Cardiol. 1992;69:188-193.

11. Kitahara H, Okada K, Kimura T, et al. Impact of stent size selection on acute and long-term outcomes after drug-eluting stent implantation in de novo coronary lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:e004795.

12. Sinha SK, Mahrotra A, Abhishekh NK, et al. Acute stent loss and its retrieval of a long, tapering morph stent in a tortuous, calcified lesion. Cardiol Res. 2018;9:63-67.

13. Zivelonghi C, van Kuijk JP, Nijenhuis V, et al. First report of the use of long-tapered sirolimus-eluting coronary stent for the treatment of chronic total occlusions with the hybrid algorithm. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 201;5:1-9.

14. Matchin YG, Atanesyan RV, Kononets EN, Danilov NM, Bubnov DS, Ageev FT. The first experience of using very long stents covered with sirolimus (4060 mm) in the treatment of patients with extensive and diffuse lesions of the coronary arteries. Kardiologiia. 2017;57:19-26.

15. Timmins LH, Meyer CA, Moreno MR, Moore Jr. JE. Mechanical modeling of stents deployed in tapered arteries. Ann Biomed Eng. 2008;36:2042-2050.

16. Xiang Shen, Yong-Quan Deng, Song Ji, Zhong-Min Xie. Flexibility behavior of coronary stents:the role of linker investigated with numerical simulation. J Mech Med Biol. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219519417501123.

17. Mushahwar SS, Pyatt JR, Lowe R, Morrison WL, Perry RA, Ramsdale DA. Clinical outcomes of long coronary stents:a single-center experience. Int J Cardiovasc Intervent. 2001;4:29-33.

18. Sim HW, Thong EH, Loh PH, et al. Treating very long coronary artery lesions in the contemporary drug-eluting-stent era:single long 48 mm stent versus two overlapping stents showed comparable clinical results. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:1115-1118.

19. Peter Jüni RL, Löffel L, Wandel S, et al. Impact of Stent Overlap on Angiographic and Long-Term Clinical Outcome in Patients Undergoing Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1178–1188.

20. Lagache M, Coppel R, Finet G, et al. Impact of Malapposed and Overlapping Stents on Hemodynamics:A 2D Parametric Computational Fluid Dynamics Study. Mathematics. 2021;9:795.

21. Jurado-Román A, Abellán-Huerta J, Antonio Requena J, et al. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes Between Very Long Stents and Overlapping Stents for the Treatment of Diffuse Coronary Disease in Real Clinical Practice. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019;20:681-686.

22. Patted SV, Jain RK, Jiwani PA, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Novel Long-Tapered Sirolimus Eluting Coronary Stent System in Real-World Patients With Long Diffused De Novo Coronary Lesions. Cardiol Res. 2018;9:350-357.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Coronary artery aneurysms are a complex situation. Our main objective is to describe the frequency of use of covered stents (grafts) for their management, as well as to characterize their long-term results compared to drug-eluting stents.

Methods: Ambispective observational study with data from the International Coronary Artery Aneurysm Registry (CAAR) (NCT-02563626). Only patients who received a stent-graft or a drug-eluting stent where the aneurysm occurred were selected.

Results: A total of 17 patients received, at least, 1 stent-graft while 196 received 1 drug-eluting in the aneurysmal vessel. Male predominance, a higher rate of dyslipidemia, a past medical history of coronary artery disease, previously revascularized coronary artery disease, and giant aneurysms were reported in the stent-graft cohort. The independent predictive variables of the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, heart failure, unstable angina, reinfarction, stroke, systemic embolism, bleeding or any aneurysmal complications at the median follow-up of 38 months were suggestive of the existence of connective tissue diseases (HR, 5.94; 95%CI, 1.82-19.37), left ventricular dysfunction ≤ 55% (HR, 1.84; 95%CI, 1.09-3.1), and an acute indication for heart catheterization (HR, 2.98; 95%CI, 1.39-6.3). The use of stent-grafts was not associated with the occurrence of more composite endpoints (23.5% vs 29.6%; P = .598).

Conclusions: The use of stent-grafts to treat coronary aneurysms is feasible and safe in the long-term. Randomized clinical trials are needed to decide what the best treatment is for these complex lesions.

Keywords: Coronary aneurysm. Registry. Stent. Stent graft. Angioplasty.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Los aneurismas coronarios son una situación compleja. Planteamos como objetivo principal describir la frecuencia de utilización de stents recubiertos (grafts) para su tratamiento y caracterizar sus resultados a largo plazo en comparación con stents farmacoactivos.

Métodos: Estudio observacional ambispectivo, con información procedente del Registro Internacional de Aneurismas Coronarios (CAAR) (NCT-02563626). Se seleccionaron los pacientes que recibieron un stent-graft o un stent farmacoactivo en la zona del aneurisma.

Resultados: Un total de 17 pacientes recibieron al menos un stent-graft y 196 un stent farmacoactivo en la zona aneurismática. Se observa un predominio del sexo masculino y una mayor frecuencia de dislipemia, antecedentes de coronariopatía, enfermedad coronaria revascularizada previamente y aneurismas gigantes en la cohorte de stent-graft. Como variables independientes predictoras del desarrollo del evento combinado (muerte por cualquier causa, insuficiencia cardiaca, angina inestable, reinfarto, ictus, embolia sistémica, sangrado o cualquier complicación en el aneurisma), tras una mediana de seguimiento de 38 meses, destacaron la existencia de conectivopatías (hazard ratio [HR] = 5,94; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 1,82-19,37), la disfunción del ventrículo izquierdo ≤ 55% (HR = 1,84; IC95%, 1,09-3,1) y la indicación aguda del cateterismo índice (HR = 2,98; IC95%, 1,39-6,3). El uso de stent-grafts comparado con el de stents farmacoactivos no se asoció al desarrollo de más eventos combinados (23,5 frente a 29,6%; p = 0,598).

Conclusiones: El uso de stents recubiertos en aneurismas coronarios es factible y seguro a largo plazo. Se necesitan estudios clínicos aleatorizados para decidir el mejor tratamiento de este tipo de lesiones complejas.

Palabras clave: Aneurismas coronarios. Registro. Resultados. Stent. Stent-graft. Angioplastia.

Abbreviations

LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction.

INTRODUCTION

The first descriptions of a coronary aneurysm were reported by Morgagni back in 1761, and the first series of 21 patients were reported in 1929.1-4 Since then, a variable incidence rate—between 0.3% and 12%—has been reported in several series following the implementation of imaging modalities and coronary angiography.5 The overall incidence rate reported in a cohort of over 436 000 contemporary coronary angiographies from an international registry is 0.35%.5 Same as it happens with the clinical presentation and profile, treatment varies significantly.5,6 Still, revascularization is often required here.6 Over the last few years, some of the alternatives available propose the use of stent-grafts for the exclusion of coronary aneurysms.5-14

These devices—initially developed for other indications15 such as coronary perforations—have proven useful and safe in the short-term, and in cases and series previously published.7-10,12

The main goal of this paper is to describe the frequency of use of this type of stents for the management of coronary aneurysms and characterize its long-term results using patients with drug-eluting stents as the control group since they have had good results in this context.5

METHODS

This paper uses data curated from the International Coronary Artery Aneurysm Registry (CAAR) (NCT-02563626).16 Using a methodology already published, this ambispective registry included data from adult patients (≥ 18 years) who underwent a coronary angiography for whatever reason in 32 hospitals from 9 different countries.5 Coronary aneurysm was defined as a focal dilatation (< 1/3 of the vessel) 1.5 times larger compared to the vessel diameter in a healthy adjacent segment; the giant aneurysm was defined as a dilatation 4 times larger compared to the reference diameter.16 Investigators were advised to collect a consecutive case series in specific closed periods of time. Both the clinical and the procedural variables were collected, as well as the events occurred during the index hospital stay considered as that moment when it was first reported that the patient had, at least, 1 coronary aneurysm. Then, after validating which patients were eligible, the clinical follow-up was performed with information from the health records collected via medical consultations or phone calls. As stated in former reports, the protocol was initially approved by the coordinating center ethics committee and then by the centers that required it. Data were collected anonymously, and patients gave their informed consent to all the study procedures. Clinical decisions were always made by the treating physician of every patient without any influence from the study protocol whatsoever. The analysis of this study only included patients who received a stent-grafts or drug-eluting stents in an aneurysmal area.

The study primary endpoint was to describe the real-life use of stent-grafts to treat coronary aneurysms. Secondary endpoints were to determine the occurrence of events at the long-term follow-up. Similarly, another secondary endpoint was to conduct a comparison with patients who received drug-eluting stents in the aneurysmal area. If both types of stents were implanted, the patient from the stent-graft group was considered. Similarly, the analyses were conducted individually in each patient.

Statistical analysis

The statistical package SPSS v24.0 (IBM-SPSS, United States) was used to conduct the statistical analysis. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or as median and interquartile range, when appropriate. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Inter-group comparisons were made using the chi-square test with qualitative variables. On the other hand, the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test or Wilcoxon test were used, when appropriate, with continuous variables. The long-term event-free survival curves for the different analyses and groups were obtained using the Kaplan-Meier method. In them, the inter-group comparisons were performed using the log-rank test.

Based on the principle of parsimony, multivariable models were used in which, to avoid ann excess of variables in the analysis, only those with P values ≤ .10 were included in the univariate study that will be further explained later. Both the hazard ratio (HR) and the confidence intervals were estimated at 95% (95%CI) based on a Cox logistic regression model with backward elimination (Wald). Two-tailed P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

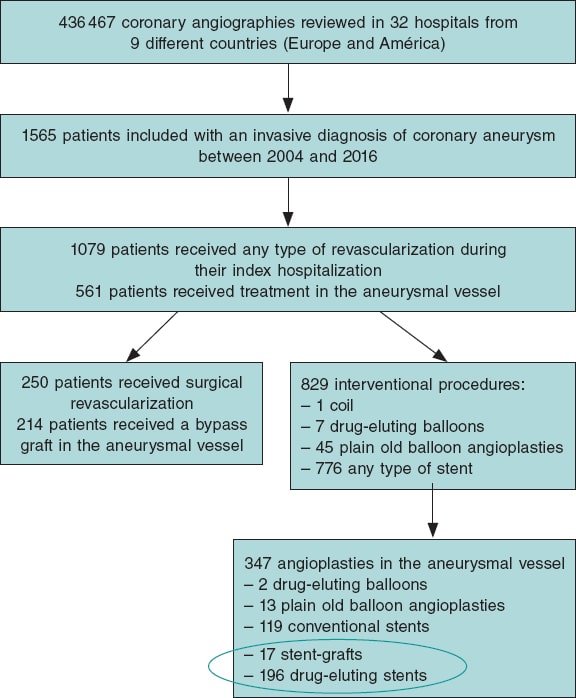

RESULTS

Out of a total of 1565 patients eventually considered in the global registry, 250 were referred for coronary artery surgery and 829 to receive some type of percutaneous revascularization.5 A total of 17 of these patients received, at least, 1 stent-graft to treat their coronary aneurysm. Also, 196 patients received a drug-eluting stent in the aneurysmal area. Therefore, the 17 and 196 patients mentioned before were included in the subsequent analyses of this study. Figure 1 shows the flow of patients.

Figure 1. Flow of the registry patients. The devices encircled in an oval were analyzed in this study. In the stent-graft group it was studied whether patients received a device of this type regardless of other devices.

Approximately, 8% of the patients specifically treated in the aneurysmal area received a stent-graft. Table 1 shows the clinical and angiographic characteristics, and the long-term events of both patients who received stent-grafts and those who received drug-eluting stents. Males were predominant and often showed signs of dyslipidemia, previous coronary arteriopathy, coronary artery disease with previous revascularization, and giant aneurysms in the cohort implanted with stent-grafts. The frequency and type of complications reported at the long-term follow-up with an overall median follow-up of 38 months are shown on table 1. No statistically significant differences were seen at the follow-up regarding the clinical events. A composite event rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) of 29.6% was reported in patients treated with drug-eluting stents compared to 23.5% in those treated with stent-grafts. Individually, the most common event reported in the group implanted with stent-grafts was unstable angina (11.8%). In the group treated with drug-eluting stents, the most common event was unstable angina (10.2%) and death (10.2%). Every individual event is shown on table 1.

Table 1. Overall characteristics of patients treated with stent-grafts compared to those treated with drug-eluting stents as first-line therapy for the management of coronary aneurysms

| Patients | Stent-graft (N = 17) | Drug-eluting stent (N = 196) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 61.47 ± 13.8 | 63.84 ± 12.8 | .467 |

| Sex, male | 16 (94.1) | 146 (74.5) | .069 |

| Arterial hypertension | 11 (64.7) | 142 (72.4) | .496 |

| Dyslipidemia | 15 (88.2) | 119 (60.7) | .024 |

| Diabetes | 3 (17.6) | 58 (29.6) | .296 |

| Smoking habit | .218 | ||

| Active smoker | 10 (58.8) | 82 (41.8) | |

| Former smoker | 3 (17.6) | 25 (12.8) | |

| Family history of coronary arteriopathy | 7 (41.2) | 14 (7.1) | < .001 |

| Kidney disease (CrCl < 30) | 1 (5.9) | 14 (7.1) | .846 |

| Peripheral vasculopathy | 1 (5.9) | 18 (9.2) | .647 |

| Aortopathy – aneurysms | 1 (5.9) | 6 (3.1) | .531 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (5.9) | 7 (3.6) | .631 |

| Connective tissue disease | 0 | 3 (1.5) | .607 |

| LVEF | 56.8 ± 6.1 | 55.6 ± 11.4 | .657 |

| Previous revascularization | 8 (47.0) | 41 (20.9) | .014 |

| Angiographic characteristics | |||

| Right dominance | 14 (82.4) | 166 (84.7) | .641 |

| Serious coronary stenoses | 15 (88.2) | .132 | |

| 1 vessel disease | 4 (23.5) | 62 (31.6) | |

| 2-vessel disease | 6 (35.3) | 68 (34.7) | |

| 3-vessel disease | 5 (29.4) | 62 (31.6) | |

| Location of the aneurysma | |||

| Left main coronary artery | 0 | 3 (1.5) | .607 |

| LAD | 7 (41.2) | 125 (63.8) | .066 |

| LCX | 4 (23.5) | 49 (25) | .893 |

| RCA | 6 (35.3) | 53 (27.0) | .466 |

| Type of aneurysmb | .450 | ||

| Fusiform | 5 (29.4) | 85 (43.8) | |

| Saccular | 12 (70.6) | 107 (55.2) | |

| Giant aneurysm | 3 (17,6) | 5 (2,6) | .02 |

| Number of aneurysms per patient | .940 | ||

| 1 | 15 (88.2) | 155 (79.1.2) | |

| 2 | 2 (6.3) | 30 (15.3) | |

| 3 | 0 | 6 (3.1) | |

| 4 or more | 0 | 5 (2.5) | |

| Indication for catheterization, acute | 11 (64.7) | 144 (73.5) | .436 |

| Indication for catheterization | .179 | ||

| STEACS | 6 (35.3) | 49 (25.0) | |

| NSTEACS | 4 (23.5) | 91 (46.4) | |

| Heart failure | 1 (5.9) | 2 (1) | |

| Stable angina | 6 (35.3) | 32 (16.3) | |

| Other | 0 | 22 (11.2) | |

| Type of stent | – | ||

| Aneugraft | 4 (23.5) | ||

| Jostent-graftmaster | 11 (64.7) | ||

| Papyrus | 1 (5.9) | ||

| Undetermined stent-graft | 1 (5.9) | ||

| ABSORB | 2 (1.0) | ||

| ACTIVE | 28 (14.3) | ||

| BIOFREEDOM | 1 (0.5) | ||

| BIOMATRIX | 4 (2.0) | ||

| COMBO | 2 (1.0) | ||

| COROFLEX | 1 (0.5) | ||

| CRE8 | 8 (4.1) | ||

| CYPHER | 3 (1.5) | ||

| GENOUS | 1 (0.5) | ||

| JANUS | 2 (1.0) | ||

| NO ESPECIF | 8 (4.1) | ||

| ONYX | 1 (0.5) | ||

| ORSIRO | 3 (1.5) | ||

| PROMUS | 20 (10.2) | ||

| RESOLUTE | 23 (11.7) | ||

| STENTYS | 6 (3.1) | ||

| SYNERGY | 12 (6.1) | ||

| XIENCE | 47 (24.0) | ||

| TAXUS | 22 (11.2) | ||

| YUKON | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Size of the stent-graft, medians | |||

| Diameter | 3.5 (3.5-4.0) | 3.5 (3.0-3.75) | .336 |

| Length | 18.0 (16.0-26.0) | 20.0 (15.0-28.0) | .014 |

| Intracoronary imaging modalities | |||

| IVUS | 5 (29.4) | 19 (9.7) | .014 |

| OCT | 1 (5.9) | 7 (3.6) | .631 |

| Any or both | 6 (35.3) | 26 (13.3) | .015 |

| Follow-up | |||

| Median follow-up, months | 29.9 (2.33-51.54) | 46.95 (11.92-76.75) | .093 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy at discharge | 17 (100) | 193 (99.5) | .767 |

| Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, median | 12.0 (11.0-12.0) | 12 (12.0-12.0) | .372 |

| Oral anticoagulation/new indication | 2/0 | 9/0 | |

| Adverse events | |||

| Heart failure | 0 | 3 (1.5) | .607 |

| Unstable angina | 2 (11.8) | 20 (10.2) | .839 |

| Reinfarction | 1 (5.9) | 16 (8.2) | .739 |

| Clinically relevant bleeding | 1 (5.9) | 8 (4.1) | .723 |

| Embolism | 0 | 1 (0.5) | .768 |

| Stroke | 0 | 2 (1) | .676 |

| Dead | 0 | 20 (10.2) | .166 |

| All of the above or complicated aneurysm (MACE) | 4 (23.5) | 58 (29.6) | .598 |

| Coronary angiography at the follow-up | 8 (47.0) | 61 (31.1) | .187 |

| Control | 3 (17.6) | 16 (8.2) | |

| Stable angina | 3 (17.6) | 6 (3.1) | |

| NSTEACS | 2 (11.8) | 25 (12.8) | |

| STEACS | 0 | 6 (3.1) | |

| Other | 0 | 8 (4.0) | |

| Aneurysmal complications on the angiographyc | |||

| Growth | 0 | 7 (11.5) | .312 |

| New aneurysms | 0 | 3 (4.9) | .521 |

| Thrombosis | 0 | 6 (9.8) | .353 |

| In-stent restenosis | 1 (12.5) | 0 | .005 |

|

Cr, creatinine; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; OCT, optical coherence tomography; RCA, right coronary artery; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. a There are more aneurysms than patients because the same patient can have several aneurysms. b Aneurysm was categorized as mixed (fusiform and saccular) in 2 patients. c Statistics is performed on a lower N, only in those with a coronary angiography at the follow-up. |

|||

Coronary angiographies at the follow-up became available for 69 patients (32.4%). Eight of them were performed in the group with stent-grafts and only 1 confirmed failed stent implantation due to in-stent restenosis. In the group treated with drug-eluting stents, the aneurysm grew bigger or new aneurysms appeared in over 15% of the patients with follow-up coronary angiographies available. The rate of thrombosis in this selected group reached 9.8%. Table 2 provides an overall comparison between patients with the composite endpoint of MACE and those without it.

Table 2. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients depending on whether they showed, at least, 1 major adverse cardiovascular event at the follow-upa

| Patients | Without events (N = 151) | Some MACE (N = 62) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 62.99 ± 12.37 | 65.29 ± 13.93 | .234 |

| Sex, make | 115 (76.2) | 47 (75.8) | .956 |

| Arterial hypertension | 107 (70.9) | 456 (74.2) | .623 |

| Dyslipidemia | 93 (61.6) | 41 (66.1) | .533 |

| Diabetes | 39 (25.8) | 22 (35.5) | .157 |

| Smoking habit | .808 | ||

| Active smoker | 64 (42.4) | 28 (30.4) | |

| Former smoker | 19 (12.6) | 9 (14.5) | |

| Family history of coronary arteriopathy | 17 (11.3) | 4 (6.5) | .285 |

| Kidney disease (CrCl < 30) | 8 (5.3) | 7 (11.3) | .120 |

| Peripheral vasculopathy | 9 (6.0) | 10 (16.1) | .018 |

| Aortopathy – aneurysms | 3 (2.0) | 4 (6.5) | .097 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (3.3) | 3 (4.8) | .594 |

| Connective tissue disease | 0 | 3 (4.8) | .006 |

| LVEF | 56.62 ± 9.74 | 53.67 ± 13.44 | .080 |

| Previous revascularization | 36 (23.8) | 13 (21.0) | .651 |

| Angiographic characteristics | |||

| Right dominance | 127 (84.1) | 53 (85.5) | .237 |

| Serious coronary stenoses | 147 (97.4) | 60 (96.8) | .817 |

| 1 vessel disease | 47 (31.1) | 19 (30.6) | |

| 2-vessel disease | 52 (34.4) | 22 (35.5) | |

| 3-vessel disease | 48 (31.8) | 19 (30.6) | |

| Location of the aneurysmb | .429 | ||

| Left main coronary artery | 3 (2.0) | 0 | |

| LAD | 88 (58.3) | 44 (71) | |

| LCX | 41 (27.2) | 12 (19.4) | |

| RCA | 41 (27.2) | 18 (29.0) | |

| Type of aneurysmc | .676 | ||

| Fusiform | 62 (41.1) | 28 (45.2) | |

| Saccular | 86 (57.0) | 33 (53.2) | |

| Giant aneurysm | 4 (2.6) | 4 (6.5) | .185 |

| Number of aneurysms per patient | |||

| 1 | 122 (80.8) | 48 (77.4) | |

| 2 | 20 (13.2) | 12 (19.4) | |

| 3 | 6 (4.0) | 0 | |

| 4 or more | 3 (2.0) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Indication for catheterization, acute | 101 (66.9) | 54 (87.1) | .002 |

| Indication for catheterization | .053 | ||

| STEACS | 38 (25.1) | 17 (27.4) | |

| NSTEACS | 61 (40.4) | 34 (54.8) | |

| Heart failure | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Stable angina | 33 (21.8) | 5 (8.1) | |

| Other | 17 (11.2) | 5 (8.1) | |

| Type of stent | .598 | ||

| Stent-graft | 13 (8.6) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Drug-eluting stent | 138 (91.4) | 58 (93.5) | |

| Size of the stent-graft, medians | |||

| Diameter | 3.38 (3.0-4.0) | 3.28 (3.0-3.5) | .521 |

| Length | 22.00 (15.0-28.0) | 21.74 (15.0-25.0) | .843 |

| Intracoronary imaging modalities | |||

| IVUS | 17 (11.3) | 7 (11.3) | .995 |

| OCT | 8 (5.3) | 0 | .065 |

| Median follow-up, months | 34.0 (12.0-76.0) | 46.93 (18.75-79.75) | .646 |

|

CD: coronaria derecha; CX: circunfleja; Cr: creatinina; DA: descendente anterior; FEVI: fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo; IVUS: ecocardiografía intravascular; MACE: eventos adversos cardiovasculares mayores; OCT: tomografía de coherencia óptica; SCACEST: síndrome coronario agudo con elevación del segmento ST; SCASEST: síndrome coronario agudo sin elevación del segmento ST. Los datos se expresan como n (%) o media ± desviación estándar. a Se consideró como MACE el combinado de muerte de cualquier causa, ingreso por insuficiencia cardiaca, angina inestable, reinfarto, ictus, embolia sistémica, sangrado que precisó atención médica o cualquier complicación del aneurisma (crecimiento, nuevo aneurisma, reestenosis o trombosis). b Hay más aneurismas que pacientes, porque cada enfermo puede presentar varios. c En varios pacientes (3 y 1, respectivamente) el aneurisma fue considerado mixto. |

|||

The multivariate analysis on the occurrence of MACE included in the model the use of stent-grafts. On the other hand, the univariate analysis included variables with P values ≤ .10. All of them are shown on table 2 including the presence or not, of peripheral vasculopathy (on therapy), previous diagnosis of aneurysm (in a territory different from the coronary one), diagnosed connective tissue disease, left ventricular ejection fraction, use of intracoronary imaging modalities (optical coherence tomography or intravascular ultrasound), and acute indication to perform index catheterization.

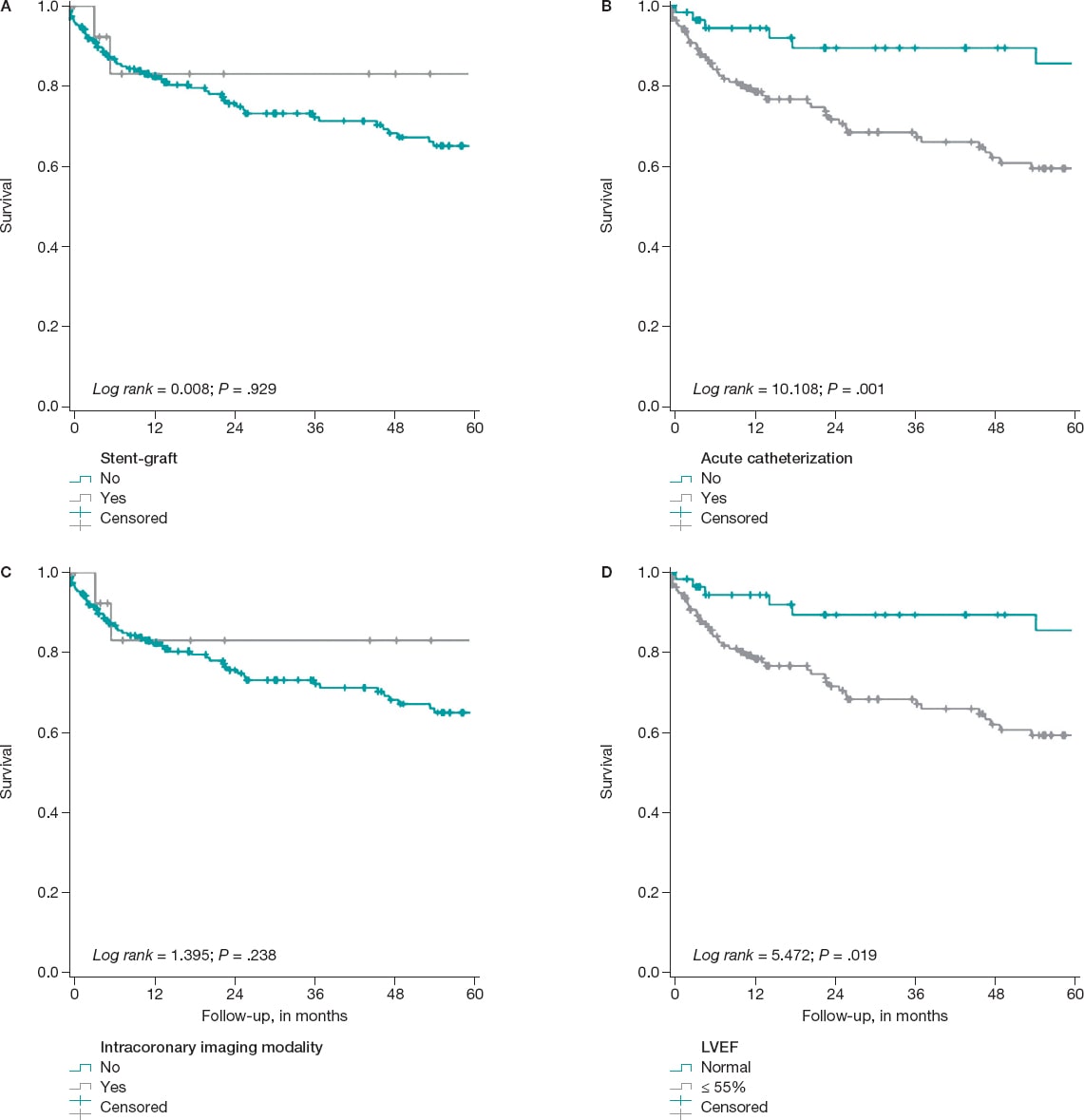

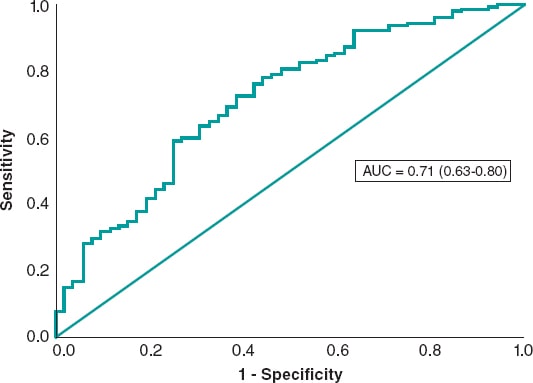

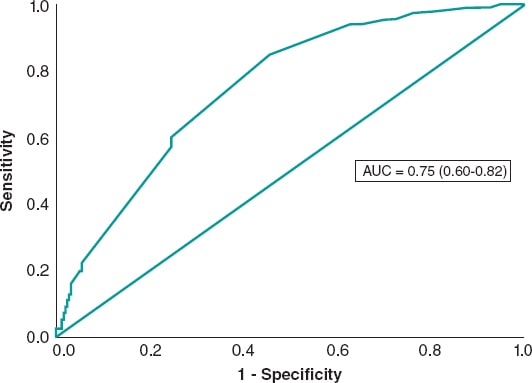

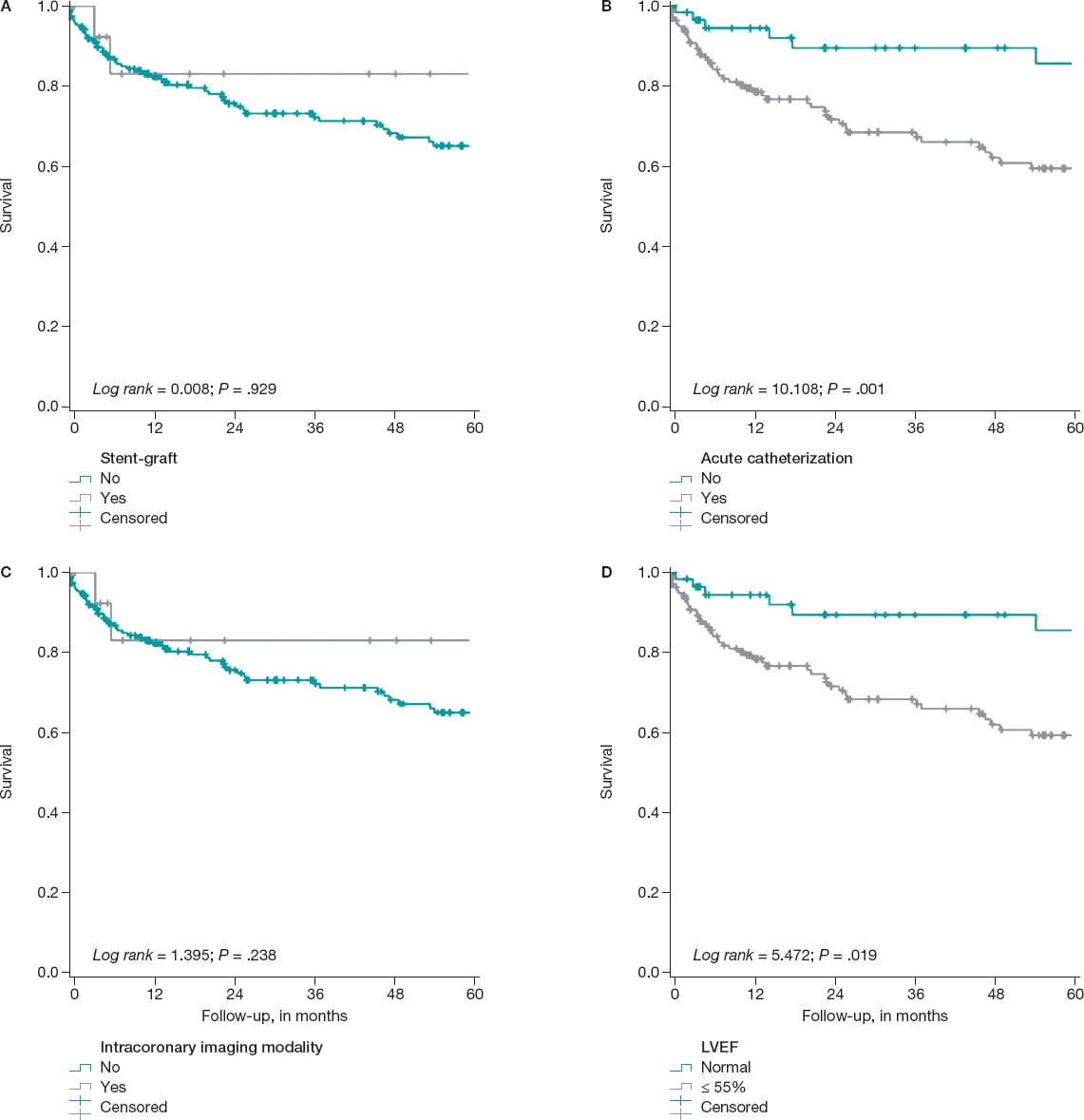

It was confirmed that the following variables remain in the model as independent predictors of the development of the composite endpoint: the existence of connective tissue disease (HR, 5.94; 95%CI, 1.82-19.37), left ventricular dysfunction—below 55%—(HR, 1.84; 95%CI, 1.09-3.1), and the acute indication for index catheterization (HR, 2.98; 95%CI, 1.39-6.3) (figure 2). The use of intracoronary imaging modalities—more common in the cohort implanted with stent-grafts—reached differences that were not statistically significant in the multivariate analysis. It was not a discriminator either regardless of the use of stent-grafts or drug-eluting stents (table 1, table 2, and figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan Meier survival curves free of the composite MACE event. A: on the use, or not of the stent-graft for the management of the aneurysm. B: based on whether the indication for index catheterization was acute (acute coronary syndrome, heart failure, etc.). C: regarding the use, during the angioplasty, of any of these intracoronary imaging modalities (intravascular ultrasound, optical coherence tomography or both), D: stratification based on the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) when the angioplasty was performed.

DISCUSSION

This analysis is one of the largest series of coronary aneurysms published including data from real-life patients. It compares 2 of the most widely used therapeutic strategies in this context,5 and its main findings are:

a) The most widely used revascularization method in patients with coronary aneurysms was percutaneous.

b) The exclusion technique, that is, the use of stent-grafts, was used in a relatively lower number of cases (8%).

c) The clinical profile of patients treated with drug-eluting stents was similar compared to patients treated with stent-grafts. However, the presence of giant aneurysms is more common in the latter group. Also, it is probably one of the factors that operators pay most attention to when choosing one stent over the other.

d) An acute indication for the index catheterization and the presence of ventricular dysfunction, at that particular moment, are independent factors of poor prognosis in the study cohort.

e) In the long-term, a similar safety and efficacy profile can be seen in both arms of treatment making stent-grafts a reasonable alternative in selected cases with coronary aneurysms.

The specific treatment of patients with coronary aneurysms has not been well-defined yet to the point that it is not even quoted by the international clinical guidelines on revascularization.5 Over the last few years, several series and registries have been published trying to shed light on this issue.5,6,8,11 Generally speaking, coronary aneurysm is a rare coronary comorbidity. Nonetheless, the average interventional cardiologist sees 1 or several cases each year in his cath lab.7,16 As a matter of fact, in our own experience its estimated that its incidence rate is around 0.35% according to over 430 000 coronary angiographies performed,5 and around 1% according to a recent Chinese series of a little over 11 000 coronary angiographies.17 For this reason, it is important to have clinical data available to guide the management of this entity.7

Also, the coronary aneurysm is a clear marker of anatomic complexity and in adult patients it is suggestive of extensive coronary artery disease, and possibly, poor prognosis compared to milder forms of coronary arteriopathy.7 In previous analyses, the use of drug-eluting stents in patients with coronary aneurysms has been proposed as a therapeutic option clearly superior to conventional stents.5 That is why—as it happens with the rest of patients with ischemic heart disease—this type of platforms is widely recommended for patients with coronary aneurysms. Similarly, the use of an intense and thorough antithrombotic therapy is probably associated with fewer evolutionary complications, which is really reasonable considering the already mentioned high ischemic risk of these patients.11,18

The use of stent-grafts has been proposed as an alternative that can restore the anatomy of the blood vessel. Although the early design of these stents originally served other purposes, the data supporting the feasibility of their use with a high rate of success are extensive.8 In our series, the stent most widely used was the classically designed Jostent Graftmaster coronary stent graft system (Abbott Vascular, United States) (nearly 65%). It is composed of a PTFE layer between 2 stainless-steel stents that may have influenced the results. As a matter of fact, in our setting, Jurado-Román et al.15 conducted a multicenter registry on a certain state-of-the-art stent-graft. They proved that, in several real-life indications, the rate of events is reasonable (MACE, 7.1% at an average 22 months). However, the rate of stent thrombosis was slightly higher (3%) compared to the rate reported by drug-eluting stents in common uses.

The use of intracoronary imaging modalities to perform angioplasties in patients with coronary aneurysms possibly has prognostic implications as it happens in other complex clinical situations (diagnostic doubts, left main coronary artery, bifurcations). In this series, although they were more widely used in the group with stent-grafts implanted, no statistically significant differences were seen on the development of MACE (figure 2). This possibly has to do with the size of the study sample. Also, a tendency was seen towards fewer events in the group of patients with procedures optimized through intracoronary imaging guidance whether intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography.

Limitations

This study has limitation associated with the particular design of the study. Also, a relatively small number of participants was included, which may have complicated the detection of differences in the analyses due to the lack of statistical power. The decision to implant stent-grafts or drug-eluting stents was entirely left to each patient’s medical team, which may have been associated with a certain degree of heterogeneity in the protocols that could have also been more dynamic in time. At the very complete follow-up from the clinical standpoint, control angiographies became available for a limited number of patients only (32%) who met the criterion set by the treating physicians. This may have underestimated the rate of complications, especially the subclinical ones, or be associated with selection biases in both groups.

However, this study is an approach to real-life clinical practice for a relatively rare heart disease on which there is little information available. It also includes a long-term clinical follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

Stents-grafts can be used to treat coronary aneurysms and are safe in the long-term. Randomized clinical trials are needed to decide what the best treatment is for this type of complex coronary lesions.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

I. J. Núñez-Gil, CAAR coordinator: study design, data analysis, and draft writing. E. Cerrato, M. Bollati, L. Nombela-Franco, and A. Fernández-Ortiz: study design. E. Cerrato, M. Bollati, B. Terol, E. Alfonso-Rodríguez, S. J. Camacho-Freire, P. A. Villablanca, I. J. Amat-Santos, J.M. de la Torre-Hernández, I. Pascual, C. Liebetrau, B. Camacho, M. Pavani, R. A. Latini, F.Varbella, V. A. Jiménez Díaz, D. Piraino, MM, F. Alfonso, J. Antonio Linares, J. M. Jiménez-Mazuecos, J. Palazuelos- Molinero, and I. Lozano: data mining and recruitment. E. Cerrato, M. Bollati, B. Terol, L. Nombela-Franco, E. Alfonso-Rodríguez, S. J. Camacho-Freire, P. A. Villablanca, I. J. Amat-Santos J.M. de la Torre-Hernández, I. Pascual, C. Liebetrau, B. Camacho, M. Pavani, R. A. Latini, F.Varbella, V. A. Jiménez Díaz, Davide Piraino, M. Mancone, F. Alfonso, J. A. Linares, J. M. Jiménez-Mazuecos, J. Palazuelos- Molinero, IÍ. Lozano, and A. Fernández-Ortiz: reading and critical review of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. M. de la Torre Hernández is the editor-in-chief of REC: Interventional Cardiology, and F. Alfonso is an associate editor of this journal. The journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. No other conflicts of interest have been declared whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Coronary aneurysms are a complex entity whose incidence rate is between 0.3 and 12% in the different series already published.

- Treatment, like the presentation and the clinical profile, is varied. However, revascularization is often required.

- In this sense, over the last few years, some of the alternatives available propose the use of stent-grafts for the exclusion of coronary aneurysms.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The main goal of this paper was to describe the frequency of use of this type of stents to treat coronary aneurysms and then characterize its long-term results.

- From a total of 829 patients with coronary aneurysms treated with some type of percutaneous revascularization, data on the use of stent-grafts and drug-eluting stents was collected in 17 and 196 patients, respectively.

- It seems obvious that patients treated with stent-grafts for the management of coronary aneurysms have a high ischemic load, often complex anatomies, and even more often giant aneurysms.

- The use of stent-grafts for the management of coronary aneurysms is feasible and safe in the long-term. However, randomized clinical trials are still needed to decide what the best therapy is for this type of complex coronary lesions.

REFERENCES

1. Bourgon A. Biblioth Med. 1812;37:183. Citado por Scott DH. Aneurysm of the coronary arteries. Am Heart J. 1948;36:403-421.

2. Packard M, Wechsler H. Aneurysms of coronary arteries. Arch Intern Med. 1929;43:1-14.

3. Swaye PS, Fisher LD, Litwin P, et al. Aneurysmal coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1983;67:134-138.

4. Cohen P, O'Gara PT. Coronary artery aneurysms:a review of the natural history, pathophysiology, and management. Cardiol Rev. 2008;16:301-304.

5. Núñez-Gil IJ, Cerrato E, Bollati M, et al. Coronary artery aneurysms, insights from the international coronary artery aneurysm registry (CAAR). Int J Cardiol. 2020;299:49-55.

6. Núñez-Gil IJ, Terol B, Feltes G, et al. Coronary aneurysms in the acute patient:Incidence, characterization and long-term management results. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2018;19(5 Pt B):589-596.

7. Kawsara A, Núñez Gil IJ, Alqahtani F, Moreland J, Rihal CS, Alkhouli M. Management of Coronary Artery Aneurysms. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1211-1223.

8. Will M, Kwok CS, Nagaraja V, et al. Outcomes of patients who undergo elective covered stent treatment for coronary artery aneurysms. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021:S1553-8389(21)00264-5.

9. Núñez-Gil IJ, Alberca PM, Gonzalo N, Nombela-Franco L, Salinas P, Fernández-Ortiz A. Giant coronary aneurysm culprit of an acute coronary syndrome. Rev Port Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2018;37:203.e1-203.e5.

10. Cha JJ, Kook H, Hong SJ, et al. Successful Long-term Patency of a Complicated Coronary Aneurysm at a Prior Coronary Branch Stent Treated with a Stent-graft and Dedicated Bifurcation Stent. Korean Circ J. 2021;51:551-553.

11. Khubber S, Chana R, Meenakshisundaram C, et al. Coronary artery aneurysms:outcomes following medical, percutaneous interventional and surgical management. Open Heart. 2021;8:e001440.

12. Arbas-Redondo E, Jurado-Román A, Jiménez-Valero S, Galeote-García G, Gonzálvez-García A, Moreno-Gómez R. Acquired coronary aneurysm after stent implantation at a bifurcation excluded with a Papyrus covered stent subsequently fenestrated. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2022;37:215-216.

13. Della Rosa F, Molina-Martin de Nicolas J, Bonfils L, Fajadet J. Symptomatic giant coronary artery aneurysm treated with covered stents. Coron Artery Dis. 2020;31:658-659.

14. Tehrani S, Faircloth M, Chua TP, Rathore S. Percutaneous coronary intervention in coronary artery aneurysms;technical aspects. Report of case series and literature review. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;28S:243-248.

15. Jurado-Román A, Rodríguez O, Amat I, et al. Clinical outcomes after implantation of polyurethane-covered cobalt-chromium stents. Insights from the Papyrus-Spain registry. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;29:22-28.

16. Núñez-Gil IJ, Nombela-Franco L, Bagur R, et al. Rationale and design of a multicenter, international and collaborative Coronary Artery Aneurysm Registry (CAAR). Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:580-585.

17. Jiang X, Zhou P, Wen C, et al. Coronary Anomalies in 11,267 Southwest Chinese Patients Determined by Angiography. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:6693784.

18. D'Ascenzo F, Saglietto A, Ramakrishna H, et al. Usefulness of oral anticoagulation in patients with coronary aneurysms:Insights from the CAAR registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98(5):864-871.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The safety of physiology-based revascularization in patients with diabetes mellitus has been scarcely investigated. Our objective was to determine the safety of deferring revascularization based on the fractional flow reserve (FFR) or the instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) in diabetic patients.

Methods: Single-center, retrospective analysis of patients with intermediate coronary stenoses in whom revascularization was deferred based on FFR > 0.80 or iFR > 0.89 values. The long-term rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, a composite of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and target vessel revascularization (TVR), was assessed in diabetic and non-diabetic patients at the follow-up. The rate of TVR based on the type of physiological index used to defer the lesion was also evaluated.

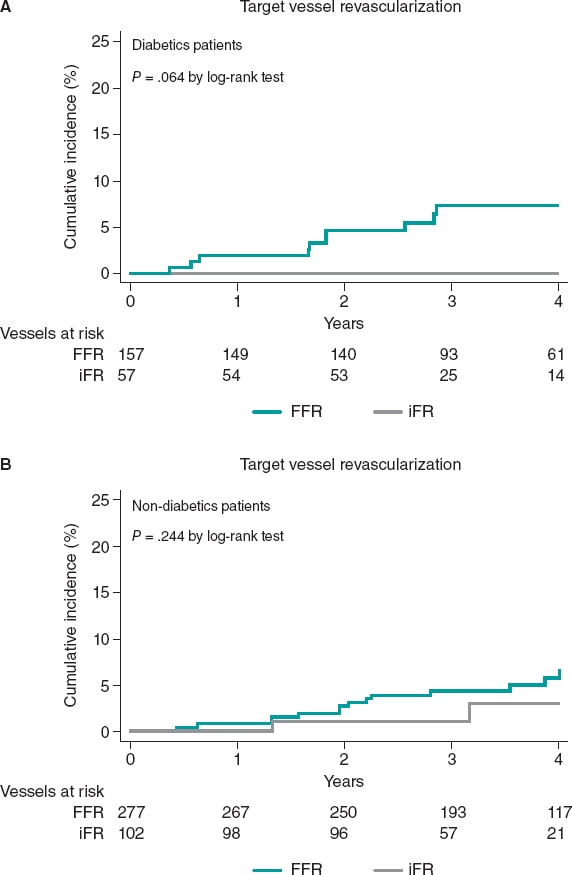

Results: We evaluated 164 diabetic (214 vessels) and 280 non-diabetic patients (379 vessels). No significant differences in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events was seen between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (20.1% vs 13.2%; P = .245) at a median follow-up of 43 months. All-cause mortality and cardiac death were not statistically different between both groups in the adjusted analysis (P > .05). A trend towards a higher rate of myocardial infarction was seen in diabetic patients (6.7% vs 2.9%; P = .063). However, the rate of target vessel myocardial infarction was similar in both groups (P = .874). Overall, TVR was similar in diabetics and non-diabetics (4.7% vs 4.2%; P = .814); however, when analyzed based on the physiological index, numerically, diabetics had a higher rate of TVR when the FFR was used in the decision-making process compared to when the iFR was used (6.4% vs 0.0%; P = .064).

Conclusions: Deferring the revascularization of intermediate stenoses in patients with DM based on the FFR or the iFR is safe regarding the risk of TVR or target vessel myocardial infarction, with a rate of events at the long-term follow-up similar to that seen in non-diabetic patients.

Keywords: Fractional flow reserve. Instantaneous wave-free ratio. iFR. Diabetes mellitus.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La seguridad de la revascularización fisiológica en pacientes diabéticos ha sido poco investigada. El objetivo fue determinar la seguridad de diferir la revascularización basándose en la reserva fraccional de flujo (FFR) o en el índice instantáneo libre de ondas (iFR) en pacientes con diabetes mellitus.

Métodos: Análisis retrospectivo, unicéntrico, de pacientes con estenosis coronarias intermedias en quienes se había diferido la revascularización en función de unos valores de FFR > 0,80 o de iFR > 0,89. Se analizó la incidencia a largo plazo de eventos cardiovasculares adversos mayores, una combinación de muerte por cualquier causa, infarto miocárdico y revascularización del vaso diana (RVD) en pacientes con y sin diabetes. También se evaluó la incidencia de RVD según el tipo de índice fisiológico utilizado para diferir la revascularización.

Resultados: Se evaluaron 164 pacientes diabéticos (214 vasos) y 280 pacientes no diabéticos (379 vasos), con una mediana de seguimiento de 43 meses. No se observaron diferencias significativas en los eventos cardiovasculares adversos mayores entre pacientes con y sin diabetes mellitus (20,1 frente a 13,2%; p = 0,245). La mortalidad por cualquier causa y de causa cardiaca no fue estadísticamente diferente entre ambos grupos en el análisis ajustado (p > 0,05). Se observó una tendencia a una mayor incidencia de infarto de miocardio en los pacientes con diabetes mellitus (6,7 frente a 2,9%; p = 0,063), pero el infarto relacionado con el vaso diana fue similar en ambos grupos (p = 0,906). En general, la RVD fue similar en diabéticos y no diabéticos (4,7 frente a 4,2%; p = 0,787); sin embargo, cuando se analizó según el índice fisiológico, los diabéticos tuvieron una mayor tasa numérica de RVD cuando se utilizó la FFR en la toma de decisiones en comparación con el iFR (6,4 frente a 0,0%; p = 0,064).

Conclusiones: Diferir la revascularización de estenosis intermedias en pacientes con diabetes mellitus según la FFR o el iFR es seguro en términos de RVD e infarto relacionado con el vaso diana, con una tasa de eventos en el seguimiento a largo plazo similar a la observada en pacientes sin diabetes mellitus.

Palabras clave: Reserva fraccional de flujo. Indice instantaneo libre de ondas. iFR. Diabetes mellitus.

Abbreviations

DM: diabetes mellitus. FFR: fractional flow reserve. iFR: instantaneous wave-free ratio. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. TVR: target vessel revascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Physiological evaluation has a class IA recommendation to guide coronary revascularization in the current clinical practice guidelines.1 Fractional flow reserve (FFR) and instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) have proven to be safe tools to guide revascularization therapy in several clinical scenarios.2-4

The results of the DEFER trial at the 15-year follow-up showed the long-term safety of FFR to defer therapy in functionally non-significant stenosis.5 Afterwards, the DEFINE-FLAIR and the iFR-SWEDEHEART trials proved the non-inferiority of the iFR compared to the FFR to guide revascularization of moderate stenosis at the 1-year follow-up.3,6 The utility of physiological guidance to guide revascularization in multivessel disease has been confirmed in the FAME and the SYNTAX II clinical trials.7,8

However, the prognostic value of pressure guidewire assessment in certain high-risk groups has not been firmly established yet. A pooled analysis of the DEFINE-FLAIR and the iFR-SWEDEHEART trials found a higher rate of events in patients with acute coronary syndrome in whom revascularization of non-culprit vessels was deferred based on the FFR or the iFR compared to stable patients.3,6 Patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) are a high-risk group with a well-known higher burden of cardiovascular disease and worse prognosis including more extensive atherosclerosis, more prevalence of multivessel disease, and a faster disease progression compared to non-diabetic patients.9-11 The special characteristics of the extent and spread of atherosclerosis in patients with DM raises concerns on the safety surrounding deferring revascularization in this population. Our objective was to evaluate the safety of revascularization deferral based on pressure guidewire interrogation in diabetic patients at the long-term follow-up.

METHODS

Study population

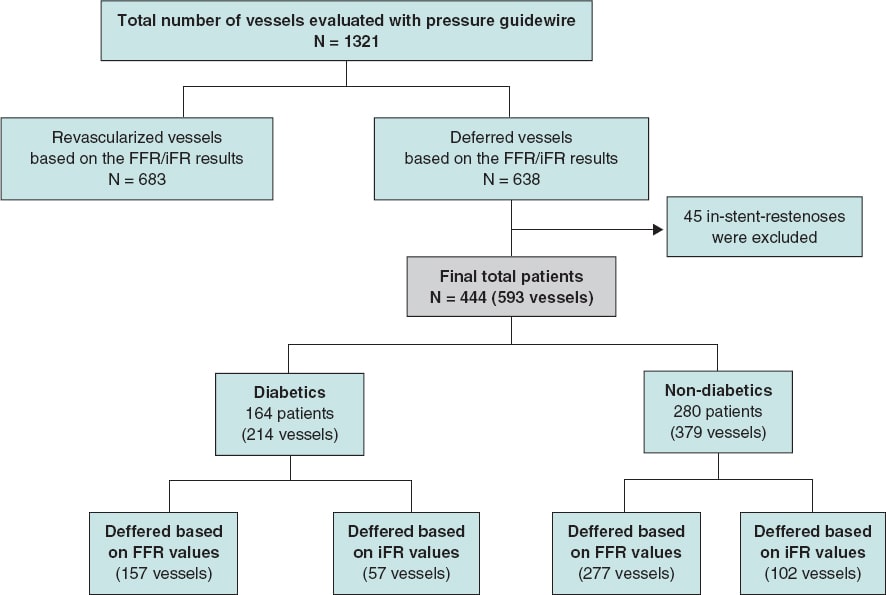

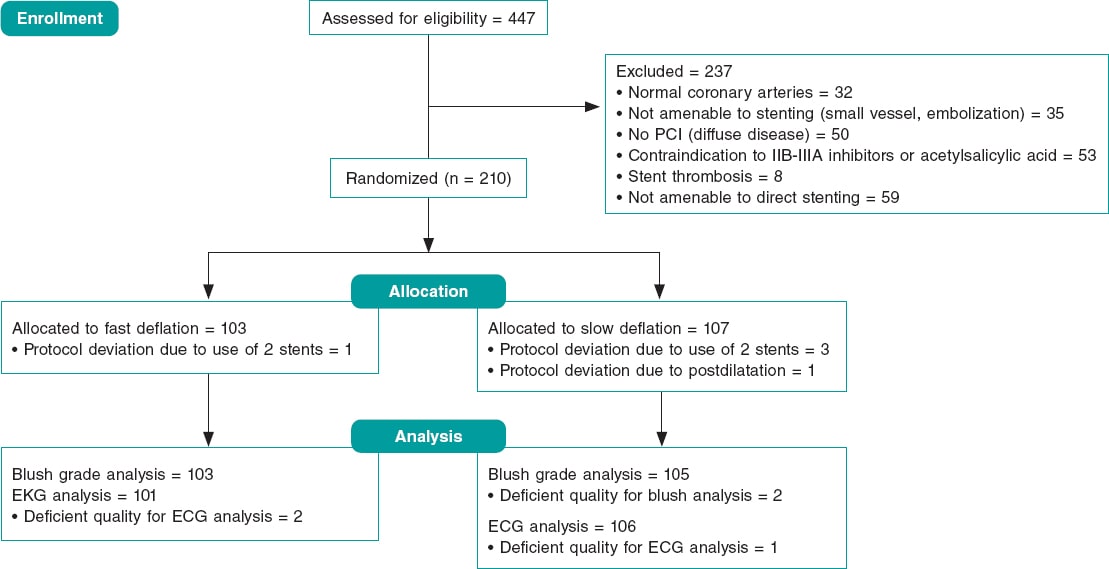

This is a single center, retrospective, and open-label trial. The study population was recruited from a total of 1321 consecutive patients with coronary artery disease in whom the iFR or the FFR indices were used to determine the need for coronary revascularization from January 2012 through December 2016. In 444 patients (34%) the revascularization of ≥ 1 lesions was deferred based on FFR values > 0.80 or iFR values > 0.89. Patients with stable angina and acute coronary syndrome (with non-culprit stenosis interrogated with pressure guidewires) were included in the study. For the analysis, the overall population was divided into 2 groups: DM and non-DM. The DM group was defined based on their past personal history included in their medical records. The study flow chart depicting patient selection is shown on figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flow chart. iFR, instantaneous wave-free ratio; FFR, fractional flow reserve.

This retrospective, cohort study was conducted according to the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki. Both the informed consent and the research committee assessment were spared due to the retrospective nature of the study; each patient included in the database was encrypted and de-identified to protect everyone’s privacy.

The physiological procedure

Pressure guidewire assessment was performed using a commercial guidewire (Verrata, Philips Healthcare, United States; PressureWire [Certus. Aeris, X] St. Jude Medical, United States) and the standard technique previously reported.3,12 As a standard practice, an intracoronary bolus of nitrates (200 mcg) was administered before the FFR or iFR measurements. The cases submitted for FFR assessment received IV adenosine at a rate of 140 µg/kg/min. The cut-off values to defer revascularization were FFR > 0.80 or iFR > 0.89. The presence of significant drift was discarded by placing the sensor of the pressure guidewire on the tip of the guiding catheter at the end of the physiological measurements acquisition.

In patients with stable angina, the physiological evaluation was performed as part of the same procedure, and all intermediate stenoses were assessed. In patients with acute coronary syndrome, interrogation with the pressure guidewire was performed at a staged procedure in non-culprit vessels only.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the 4-year risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) defined as a composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction or unplanned target vessel revascularization (TVR). The secondary endpoints were a) the individual components of MACE, b) the rate of target vessel myocardial infarction, and c) the rate of unplanned TVR based on the physiological index used (FFR or iFR)

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Discrete variables are summarized as frequency (percentages). Under baseline conditions, group comparisons were made using the Student t test or the Mann Whittney U test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square test for discrete data.

Time-to-event analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, and group comparison was performed using the Mantel-Cox (log-rank) test. For the primary and secondary endpoint comparison between diabetics and non-diabetics, a Cox Proportional hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios (HR). The adjusted analysis was performed based on age, sex, hypertension, dyslipidemia, smoking habit, chronic kidney disease, previous stroke, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, and coronary artery bypass graft surgery.

All probability values were 2-sided with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). P values < .05 were considered statistically significant. The SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States) and STATA version 15 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States) statistical packages were used for statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics

The baseline clinical characteristics are shown on table 1. In the overall study population, mean age was 68.4 years, and 39.6% were patients with DM (164 patients). As expected, patients with DM had more cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidities compared to patients without DM. There were no significant differences in the clinical presentation between both study groups (P > .05). Most patients received optimal medical treatment at the hospital discharge without significant differences between DM and non-DM patients (P > .05).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

| Total (N = 444) | Diabetics (N = 164) | Non-diabetics (N = 280) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics, N (%) | ||||

| Sex | .026 | |||

| Male | 340 (76.5) | 116 (70.7) | 224 (80.0) | |

| Female | 104 (23.4) | 48 (29.3) | 56 (20.0) | |

| Age (year) | 68.41 | 70.02 | 67.46 | .003 |

| Arterial hypertension | 321 (72.3) | 138 (84.1) | 183 (65.4) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 287 (64.6) | 124 (75.6) | 163 (58.2) | <.001 |

| Current smoker | 253 (57.0) | 85 (51.8) | 168 (60.0) | .093 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 41 (9.2) | 29 (17.7) | 12 (4.3) | .000 |

| COPD | 30 (6.8) | 9 (5.5) | 21 (7.5) | .415 |

| Previous cerebrovascular disease | 21 (4.7) | 12 (7.3) | 9 (3.2) | .049 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 38 (8.6) | 18 (11.0) | 20 (7.1) | .164 |

| Previous AMI | 47 (10.6) | 17 (10.4) | 30 (10.7) | .908 |

| Previous PCI | 220 (49.5) | 70 (42.7) | 150 (53.6) | .027 |

| Previous CABG | 13 (2.9) | 9 (5.5) | 4 (1.4) | .019 |

| Clinical presentation, N (%) | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 148 (33.3) | 46 (28.0) | 102 (36.4) | .302 |

| Unstable angina | 89 (20.0) | 33 (20.1) | 56 (20.0) | |

| Stable angina | 112 (25.2) | 44 (26.8) | 68 (24.3) | |

| Silent ischemia | 46 (10.4) | 22 (13.4) | 24 (8.6) | |

| Other | 49 (11.0) | 19 (11.6) | 30 (10.7) | |

| Therapy at discharge, N (%) | ||||

| Aspirina | 408 (93.8) | 150 (94.3) | 258 (93.5) | .720 |

| Clopidogrela | 165 (37.9) | 53 (33.3) | 112 (40.6) | .134 |

| Prasugrela | 22 (5.1) | 9 (5.7) | 13 (4.7) | .663 |

| Ticagrelora | 78 (17.9) | 30 (18.9) | 48 (17.4) | .699 |

| DAPT | 332 (56.3) | 111 (52.6) | 221 (58.3) | .181 |

| Statinsb | 396 (93.2) | 148 (93.1) | 248 (93.2) | .952 |

| Beta-blockersb | 334 (78.6) | 121 (76.1) | 213 (80.1) | .334 |

| ACEIb | 324 (76.2) | 126 (79.2) | 198 (74.4) | .260 |

| Acenocoumarola | 41 (9.4) | 18 (11.3) | 23 (8.3) | .304 |

| Insulin | 53 (8.9) | 53 (24.8) | ||

|

ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting;; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. a n = 435. b n = 425. |

||||

Characteristics of vessels with deferred revascularization

On average, deferred revascularization was performed in vessels with stenoses of intermediate severity (percent diameter stenosis, 59.73% ± 9.2%). The most frequently interrogated artery was the left anterior descending coronary artery (43.2%). In most patients, only 1 vessel was deferred (72.7%). Nevertheless, in about 4% of patients, revascularization was deferred in 3 vessels within the same procedure.

In our study population, revascularization deferral was based more frequently in the FFR (434 vessels, 73.2%) compared to the iFR (159 vessels, 26.8%). The same ratio applied to patients with DM: revascularization was deferred in 157 vessels (73.4%) based on FFR values compared to 57 vessels (26.6%) based on iFR values. The mean FFR and iFR values of the overall population were 0.87 ± 0.46 and 0.94 ± 0.41, respectively without any significant differences between diabetic and non-diabetic patients (table 2).

Table 2. Characteristics of the deferred arteries

| Total (N = 593) | Diabetics (N = 214) | Non-diabetics (N = 379) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred vessel | ||||

| LMCA | 25 (4.2) | 8 (3.7) | 17 (4.5) | .664 |

| LAD | 256 (43.2) | 90 (42.1) | 166 (43.8) | .681 |

| LCX | 173 (29.2) | 59 (27.6) | 114 (30.1) | .519 |

| RCA | 138 (23.3) | 57 (26.6) | 81 (21.4) | .145 |

| Number of deferred vessels per patient* | ||||

| 1 vessel | 323 (72.7) | 122 (74.4) | 201 (71.8) | .475 |

| 2 vessels | 98 (22.1) | 35 (21.3) | 63 (22.5) | |

| 3 vessels | 19 (4.3) | 7 (4.3) | 12 (4.3) | |

| 4 vessels | 4 (0.9) | 4 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Coronary physiological parameters | ||||

| Mean FFR | 0.87 ± 0.46 | 0.86 ± 0.41 | 0.87 ± 0.48 | .387 |

| Mean iFR | 0.94 ± 0.41 | 0.94 ± 0.43 | 0.95 ± 0.40 | .091 |

| Deferred based on FFR values | 434 (73.2) | 157 (73.4) | 277 (73.1) | .942 |

| Deferred based on iFR values | 159 (26.8) | 57 (26.6) | 102 (26.9) | .942 |

|

FFR, fractional flow reserve; iFR, instantaneous wave-free ratio; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; RCA, right coronary artery. * n = 444. |

||||

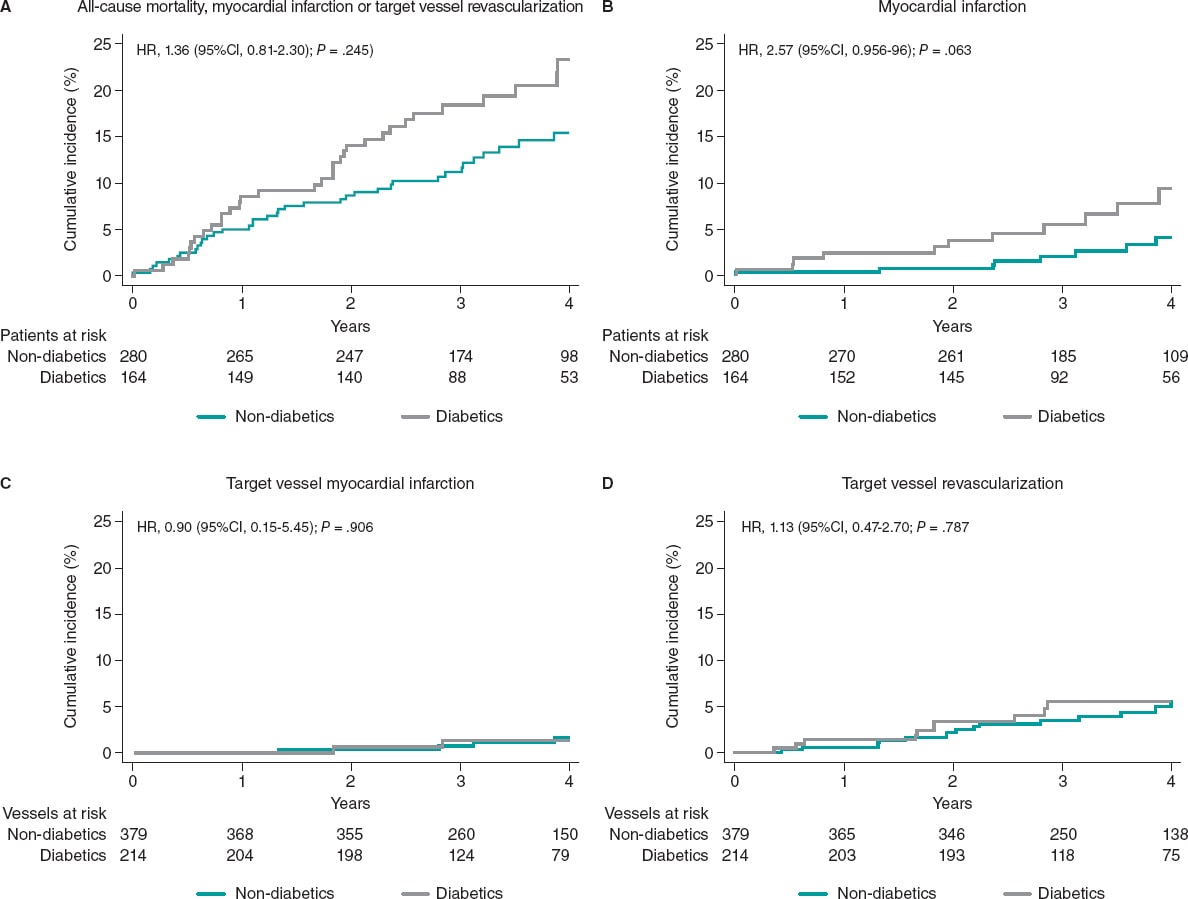

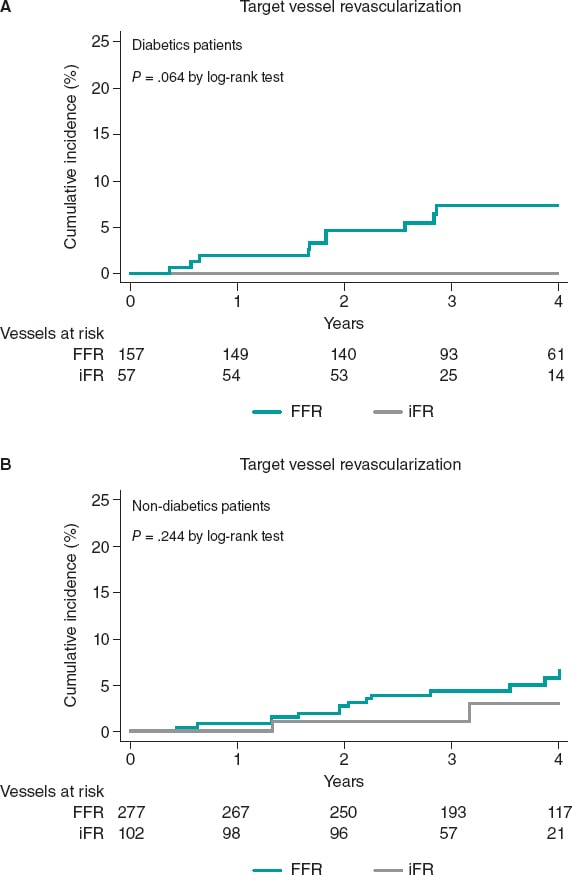

Clinical outcomes at the long-term follow-up based on the presence of diabetes

The median follow-up was 43 months [interquartile range, 31.1-55.8] without any differences being reported between DM and non-DM patients. The clinical outcomes are shown on table 3. Diabetic patients had higher rates of MACE (33 [20.1%] vs 37 [13.2%] in non-DM patients) although this difference did not reach statistical significance in the adjusted analysis (HR, 0.98, 95%CI; 0.46-2.11, P = .964). The all-cause mortality rate was higher in diabetics (18 [10.8%] vs 15 [5.3%] in non-diabetics), but the rates of cardiovascular death were not statistically different in either group (3.1% vs 2.1%). A trend towards a higher rate of myocardial infarction was seen in patients with DM (6.7% vs 2.9%; P = .063), yet target vessel myocardial infarction was similar in both groups (HR, 0,87; 95%CI, 0.15-4.89, P = .906). Similar rates of unplanned revascularization and TVR were seen between diabetics and non-diabetics (figure 2 and table 3).

Table 3. Clinical events at the 4-year follow-up based on the presence of diabetes

| Diabetics (N = 164) |

Non-diabetics (N = 280) |

Unadjusted analysis | Fully adjusted analysis* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|