Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Coronary bifurcation lesions are a common scenario in our interventional practice and can be challenging for our routine clinical practice. Yet despite the existence of well-defined techniques, side-branch compromise is still the most important problem. Currently, the standard strategy recommended is a 1-stent technique: balloon angioplasty and provisional stenting. Published non-randomized data reveal that in up to 26% of the cases the indication for rotational atherectomy was to preserve the side-branch. A randomized comparison between rotational atherectomy and provisional stenting (RAPS) and standard strategy (SS) for the management of bifurcation lesions is needed at this point.

Methods: We conducted a single center, prospective, randomized pilot study of consecutive patients from our center with bifurcation lesions. We compared the RAPS strategy to the SS. Lesions had to be located in the main vessel only. The bifurcation lesion angle was recorded. The primary endpoint was the need for side-branch therapy.

Results: 148 patients were included: 74 patients (95 rotational atherectomy) were enrolled in the RAPS group and 74 patients in the SS group. The bifurcation lesion most frequently treated was that of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery. The primary endpoint was lower in the RAPS group compared to the SS group (1.1 vs 31.2%; P < .001). Target vessel failure (TVF) was 13.1% and 24.8% (P = .04) in RAPS and SS, respectively. Both the primary endpoint and TVF were higher with bifurcation lesion angles < 70º compared to bifurcation lesion angles ≥ 70º (P = .03 and P = .02) in both groups.

Conclusions: The need for side-branch therapy and TVF was lower when the RAPS strategy was used compared to the SS. Bifurcation lesion angles < 70º are associated with higher side-branch compromise and TVF rates. The SS was associated with a 4.92-fold higher risk of side-branch compromise compared to the RAPS strategy with bifurcation lesion angles < 70º. These data reinforce the idea of the overall clinical relevance of the RAPS strategy regarding the patency of the side-branch.

Keywords: Bifurcation lesion. Rotational atherectomy. Side-branch compromise. Coronary calcification. Bifurcation angle.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Durante el intervencionismo coronario percutáneo es frecuente observar lesiones coronarias que afectan a las bifurcaciones. El compromiso de la rama lateral es la principal complicación observada con las diversas técnicas descritas para su tratamiento. La estrategia convencional (EC) recomendada en la actualidad es la colocación de un stent condicional. Los datos publicados de estudios no aleatorizados muestran que hasta en el 26% de los casos la indicación de la aterectomía rotacional fue el tratamiento de lesiones en las bifurcaciones. Es necesario el desarrollo de un estudio aleatorizado que compare la estrategia de aterectomía rotacional y stent condicional (ARSC) frente a la EC.

Métodos: Estudio piloto aleatorizado, prospectivo, de un solo centro, en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria en una bifurcación. Se comparó la estrategia de ARSC con la EC. Se prestó especial atención al ángulo de la bifurcación. El objetivo primario evalúa la necesidad de tratamiento de la rama lateral con ambas técnicas.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 148 pacientes: 74 (95 aterectomías rotacionales) en el grupo de ARSC y 74 en el grupo de EC. El objetivo primario fue menor con la ARSC que con la EC: 1,1% frente a 31,2% (p < 0,001). El objetivo de fallo del vaso tratado (FVT) fue del 13,1% en el grupo de ARSC y del 24,8% en el grupo de EC (p = 0,04). El objetivo primario y el FVT fueron mayores si la lesión era en una bifurcación < 70° en comparación con una bifurcación ≥ 70° en ambos grupos (p = 0,03 y p = 0,02).

Conclusiones: La necesidad de tratamiento de la rama lateral y el FVT fueron menores con la estrategia de ARSC que con la EC. Un ángulo < 70° en la bifurcación aumenta el riesgo de compromiso de la rama lateral y las tasas de FVT. La EC se asoció a un incremento del riesgo de compromiso de la rama lateral de 4,92 veces cuando el ángulo de la bifurcación era < 70°. Estos datos sugieren que el abordaje de lesiones en una bifurcación mediante aterectomía rotacional podría tener un beneficio clínico global.

Palabras clave: Lesión en bifurcación. Ángulo de la bifurcación. Aterectomía rotacional. Compromiso de rama lateral. Calcificación coronaria.

Abbreviations: CBL: coronary bifurcation lesion. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. RA: rotational atherectomy. RAPS: rotational atherectomy and provisional stenting. SS: standard strategy. SB: side-branch.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last few years, the profile of patients referred to undergo a coronary angiography has become worse. Similarly, angiographic findings have become worse as well. Recently, De María et al.1 published a study on the management of calcified lesions. They provided a nice contemporary overview on the management of calcified lesions in the catheterization laboratory focusing on the technologies available, intravascular imaging, and technical complexities. However, an important marker of procedural complexity was omitted: coronary bifurcation lesions. CBLs are often seen in interventional practice and can be challenging in our routine clinical practice. Yet spite the existence of several well-defined techniques to perform a percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) on a CBL, side-branch compromise is still the most important problem.2,3 Currently, the standard strategy (SS) recommended for the management of CBL is a 1-stent technique2,4 (balloon angioplasty and provisional stenting) since it has proven to be non-inferior to the elective 2-stent technique.5 It is well-known that rotational atherectomy (RA) is underused during the PCI6 and no specific randomized data are available regarding its role in the management of CBL. The role of RA in this setting has been suggested in different studies not designed for that purpose. Data published reveal that in up to 26% of the cases the indication for RA was to preserve the side-branch.7-9 As far as we know, this extended use of RA is an off-label indication that has not been specifically tested in a randomized study. We report the procedural and long-term results of the rotational atherectomy and provisional stenting (RAPS) strategy compared to the SS (balloon angioplasty and provisional stenting) in a randomized pilot study.

METHODS

Study population

We conducted a single center, prospective, randomized pilot study of consecutive patients from our center with bifurcation lesions located only in main vessel (BLMV) and who were screened before being recruited. The angiographic criteria to define the CBLs that were eligible for the study were: a) lesions: > 70% located in a major bifurcation point regardless of the length, morphology, and angulation of the bifurcation lesion; b) thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade > 2 on both the main vessel (MV) and the side-branch (SB); c) MV visual diameter: ≥ 2.5 mm; and 4.0. SB visual diameter: ≥ 2.0 mm. The presence of a heavily calcified lesion was not a prerequisite to enter the study.

The inclusion criteria were patients ≥ 18 years who signed their informed consent with Medina lesions type 1.0.0; 1.1.0 and 0.1.0 and who were eligible to undergo either one of the 2 strategies and with no confirmed or suspected contraindications for prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy.

The exclusion criteria were: a) SB < 2 mm; b) lesions with thrombus or dissection; c) vein graft lesions; d) cases of a single main vessel with severe left ventricle dysfunction (EF < 30%); e) hemodynamically unstable patients; f) contraindication for prolonged dual antiplatelet treatment; g) life expectancy < 1 year; and h) patient refusal.

Procedures

The random assignment of patients to the different treatment groups was done using the EPIDAT 4.0 software. After obtaining the patients’ informed consent they were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to the RAPS group, RA group or SS group. Patients were revascularized according to the current recommendations.1,10 In the SS group the strategy used was left to the operator’s discretion: 1 or 2 wires, previous BA or direct stenting, 1- or 2-stent technique, etc. Everything was decided in each case by the operator. In the RAPS group a single RotaWire was used in the main vessel and only in this vessel rotational atherectomy would be performed (videos 1-7 of the supplementary data).

The baseline clinical data collected include demographics and the patients’ cardiovascular past medical history and comorbid conditions. Both the angiographic and PCI data were recorded. The RA technique was performed following the current recommendations.6 CBLs were classified according to their angles: < 70º or ≥ 70º. Two different operators assessed each individual case.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was defined as “need for side-branch therapy”. This “need for side-branch therapy” was considered in the presence of clinical, ECG or hemodynamic signs suggestive of TIMI flow ≤ 2 and/or ostial stenosis ≥ 70%.11 In contrast, “side-branch compromise” was considered when in the presence of impaired SB stenosis or TIMI flow whether severe or not. The secondary endpoints were: a) Target vessel failure (TVF): a composite of cardiac death, culprit vessel myocardial infarction, target vessel restenosis, and target bifurcation restenosis at the follow-up (appendix of the supplementary data); b) Angiographic outcomes: B.1. Procedural and annual assessment success rate and its correlation with the bifurcation angle. Procedural success was defined as TIMI flow grade-3 in both the MV and the SB and a visual residual stenosis < 20% in the MV; B.2. Angiographic complications rate including stent thrombosis, dissection, occlusion, perforation, no-reflow, target lesion restenosis (TLR), and target bifurcation restenosis at the FUP. c) The major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCE). Other relevant conditions such as hemorrhages, need for transfusion, and kidney disease were also recorded. All deaths were considered cardiac unless a definite non-cardiac cause was established. Both the bifurcation technique and stent used were left to the operator’s discretion.

The periprocedural drugs and laboratory test definitions are shown on in the appendix of the supplementary data. After discharge, the patients’ clinical follow-up was conducted through personal interviews or phone calls every 6 months. Patients underwent angiographic control clinically driven only. The monitoring of cardiovascular risk factors, drugs compliance, and blood test controls were left to the discretion of the referring physician.

The aforementioned study has been conducted in full compliance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Also, it has been approved by the hospital local ethics committee. The patients’ written informed consent was obtained too.

Sample size

No randomized studies on this subset are available so we could not use the sample size formula. Instead, we used the ARCSIN approximation function and estimated that, at least, 60 subjects should be included in each group to find statistically significant differences (accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in two-sided tests). A drop-out rate < 1% was anticipated.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) for the continuous variables and as frequencies and percentages for the categorical ones. The FUP period was expressed as the median with its interquartile range [IQR]. The chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests that assessed the effect and accuracy analyses with the prevalence ratio and 95% confidence interval, when necessary, were used to compare the continuous and categorical variables, respectively. The Mann-Whitney test was used to study the non-parametric variables. Cox regression models were used to perform univariate analyses to estimate the associated hazard-ratio of death and composite endpoints at the FUP. A multivariate analysis was performed as well. The Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to determine the time-to-event outcomes, overall survival rate, and MACCE-free survival rate. We tested the equality of the estimated survival curves using the stratified log-rank test. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS Inc., 20.0 for Windows). P values < .05 were considered statistically significant in all of the tests.

RESULTS

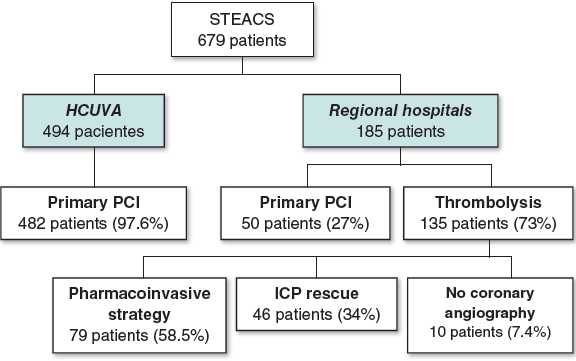

One-hundred and seventy-three out of 1028 patients who underwent a PCI between January 2015 and December 2018 were considered eligible to enter the study: 13 refused to participate, 8 patients dropped-out, and 4 patients withdrew their informed consent. Finally, 148 patients were included: 74 patients (95 RAs) were recruited in the RAPS group and 74 patients in the SS group. The inclusion/exclusion flowchart is shown on figure 1 of the supplementary data.

The baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural data are shown on table 1 and table 2. No sex-based differences were seen. Only the prevalence of a left ventricular ejection fraction ≤ 45% was different between the groups: P = .03. No calcification, tortuosity or bifurcation angle differences were reported. The most common bifurcation was found at the first diagonal branch of the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery (D1-LAD) (51%) followed by the distal left main coronary artery (LMCA)/ostial LAD (22.5%) No inter-group differences in single vs staged revascularization were seen.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

| Baseline clinical data | RAPS (N = 74) | SS (N = 74) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean; SD) | 78 (10) | 74 (7) | NS |

| Males (n; %) | 60 (81.2) | 58 (78.1) | NS |

| Weight (mean; SD) | 73.9 (11.9) | 75.4 (11.4) | NS |

| Height (m) (mean; SD) | 1.64 (0.7) | 1.66 (0.6) | NS |

| Body mass index (mean; SD) | 27.11 (3.4) | 29.24 (11.4) | NS |

| Current/Previous smoker (n; %) | 46 (62.1) | 53 (71.6) | NS |

| Hypertension (n; %) | 62 (92.2) | 74 (100) | NS |

| Diabetes mellitus (n; %) | 29 (39.1) | 30 (40.6) | NS |

| Dyslipidemia (n; %) | 69 (93.2) | 62 (83.7) | NS |

| Left ventricle ejection fraction ≤ 45 (%) | 28 (37.8) | 14 (18.7) | .03 |

| Previous myocardial infarction (n; %) | 42 (56.7) | 37 (50) | NS |

| Previous angioplasty | 42 (56.7) | 32 (43.2) | NS |

| Previous Stroke (n; %) | 10 (14.1) | 18 (24.3) | NS |

| Peripheral vascular disease (n; %) | 16 (21.6) | 23 (31) | NS |

| L-Euroscore (mean; DS) | 21.14 (22.15) | 13.7 (18.7) | NS |

| Syntax Score (mean; DS) | 34.05 (17.9) | 31.57 (17.9) | NS |

| Clinical onset (n; %) | |||

| Stable angina | 14 (19) | 20 (27) | NS |

| NSTEMI | 40 (54) | 47 (63.5) | NS |

| STEMI | 20 (27) | 7 (9.4) | NS |

| Discarded for cardiac surgery (n; %) | 24 (32.4) | 20 (27) | NS |

| NYHA Class ≥ III | 8 (9.3) | 9 (12.1) | NS |

| CCS I-II | 57 (77) | 41 (55.4) | NS |

| CCS III-IV | 17 (23) | 32 (44.6) | NS |

|

CCS, Canadian Class Classification angina score; NS, not significant; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; NYHA: New York Heart Association; RAPS, rotational atherectomy and provisional stenting; SS, standard strategy; SD, standard deviation; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

|||

Table 2. Angiographic and procedural data

| Angiographic/procedural data | RAPS (N = 74) | SS (N = 74) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6-Fr sheath (n; %) | 62 (88) | 60 (81.2) | NS |

| Radial Approach (n; %) | 29 (39.1) | 30 (40.6) | |

| Femoral approach (n; %) | 45 (60.9) | 44 (59.3) | |

| Coadjuvant therapy (n; %) | |||

| Heparin | 21 (28.1) | 29 (40.6) | NS |

| Bivaluridin | 42 (56.3) | 23 (31.2) | .01 |

| Glycoprotein inhibitors | 11 (15.9) | 23 (31.2) | NS |

| Right Dominance (n; %) | 64 (87.5) | 64 (87.5) | NS |

| Vessel disease (n; %) | |||

| Left Main coronary artery | 15 (20.3) | 14 (18.7) | NS |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery | 72 (98.4) | 57 (78.1) | .02 |

| Left circumflex artery | 47 (64.1) | 55 (71.8) | NS |

| Right coronary artery | 54 (73.4) | 57 (78.1) | NS |

| Number of diseased vessels (n; %) | |||

| 1 vessel | 10 (13.5) | 13 (17.53) | NS |

| 2 vessels | 22 (29.7) | 24 (32.4) | NS |

| 3 vessels | 34 (45.9) | 31 (41.8) | NS |

| 4 vessels | 8 (10.8) | 6 (8.1) | NS |

| Multivessel (n; %) | 60 (81.2) | 53 (71.8) | NS |

| Coronary calcification (%) | |||

| Mild | 28 | 36 | NS |

| Moderate-severe | 72 | 64 | NS |

| B2C lesions (n; %) | 94 (98.4) | 60 (81.2) | .048 |

| Medina classification of bifurcation lesions (n; %) | |||

| 1.0.0 | 46 (48.4) | 17 (23) | .04 |

| 1.1.0 | 32 (33.6) | 22 (29.7) | NS |

| 0.1.0 | 17 (17.8) | 30 (40.1) | .03 |

| Bifurcation angle (n; %) | |||

| < 70º | 46 (62) | 50 (67.5) | NS |

| ≥ 70º | 28 (38) | 24 (32.5) | NS |

| Wire | |||

| Floppy [n (%)] | 88 (92.4) | N/A | NS |

| Directly advanced [n (%)] | 84 (88.5) | N/A | NS |

| Burr size ≤ 1.5 mm | 76 (80) | N/A | NS |

| Speed (rpm) (mean; SD) | 134650 (5670) | N/A | NS |

| Rotational atherectomies performed (% per patient) | 95 (1.28) | N/A | NS |

| Burr-to-artery ratio (mean; SD) | 0.55 (.04) | N/A | |

| Number of balloons per lesion | 1.3 | 4.6 | .02 |

| Stent (n) | |||

| Number of stents per lesion | 1.6 | 2.3 | .04 |

| Number of stents per patient | 2.7 | 2.33 | NS |

| Bare-metal stent [n (%)] | 24 (12.7) | 22 (23.2) | NS |

| Drug-eluting stent [n (%)] | 167 (86.9) | 72 (76.7) | NS |

| Stenting technique [n (%)] | |||

| Provisional stenting | 64 (100) | 41 (55.4) | .04 |

| Two-stent initial approach technique | 0 | 28 (37.8) | < .001 |

| Optimal treatment of the proximal LAD | 48 (64.8) | 24 (32.4) | < .05 |

| Final kissing balloon technique | 1 (1.5) | 59 (79.7) | < .001 |

| Final inflation pressure (atm) | 18 | 14 | .05 |

| Initial vessel diameter (Me; IQR) (mm) | 2.41 (0.34) | 2.89 (0.26) | .009 |

| Final vessel diameter (Me, IQR) (mm) | 3.1 (1.9) | 2.95 (0.37) | NS |

| Maximum length stented (Me; IQR) (mm) | 56 (48) | 44 (26.1) | .005 |

| Procedural time (min) (mean; SD) | 78.8 (30) | 98 (21) | .04 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) (mean; SD) | 13 (7) | 29.2 (21) | .02 |

| Contrast media (ml) (mean; SD) | 179 (74) | 221 (73) | .05 |

| IVUS/OCT | 7 (9.4) | 11 (14.8) | NS |

|

IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; Me, median; NS, not significant; NYHA, New York Heart Association; OCT, optical coherence tomography; SD, standard deviation.s |

|||

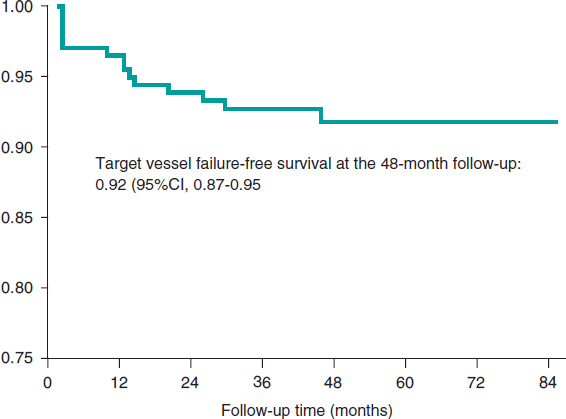

Long-term follow-up

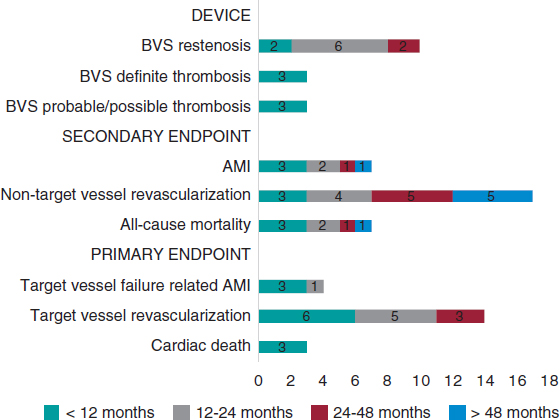

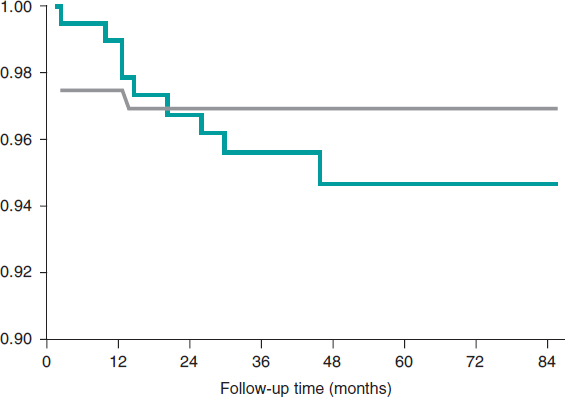

Both the clinical and angiographic success rates and outcomes were available for the entire population with a median FUP of 4.08 years [IQR: 3.18-4.78 years]. Both the all-cause and cardiovascular mortality rates were similar in both groups. The need for side-branch therapy was consistently lower in the RAPS strategy compared to the SS: 1.1% vs 27% (P < .001) (table 3). TVF was 12.1% and 24.8% (P =.04) in the RAPS strategy compared to the SS, respectively. Also, the statistical analysis confirmed that the use of the RA technique significantly reduced the risk of target vessel restenosis (P = .04), TLR (0.02), target bifurcation restenosis (P = .03), and major adverse cardiovascular events (P = .03). A positive correlation (r = 0.673, P = .03) was seen between the need for SB therapy and CBL angles < 70º. The strongest correlation was observed at the proximal D1-LAD: r = 0.79, P = .03. A weak but positive correlation was seen between the LMCA-LAD arteries angle (r = 0.412, P = .04) and the LMCA-LCx arteries angle (r = 0.342, P = .004). The sum of SS plus CBL angles < 70º was associated with a higher risk of SB compromise and TVF (OR, 4.92; 95%CI, 1.78-14.1; P = .03)

Table 3. Major adverse cardiovascular events at the follow-up

| RAPS (N = 74) | SS (N = 74) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical success (%) | 98.6 | 98 | NS |

| Associated cardiovascular mortality (hospitalizations) [n (%)] | 3 (4) | 2 (2.7) | NS |

| With procedure | 2 (2.7) | 2 (2.7) | |

| With rotational atherectomy | 1 (1.3) | N/A | |

| Angiographic success (%) | 96.5 | 97.5 | NS |

| Angiographic complications [n (%)] | |||

| Unable to advance the wire | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) | NS |

| Burr entrapment | 0 | N/A | NS |

| Unable to deliver the stent | 1 (1.3) | 2 (2.7) | NS |

| Coronary dissection | 1 (1.3) | 6 (8,1) | .024 |

| Side-branch compromise* | 2 (2.7) | 23 (31) | < .001 |

| Need for side-branch therapy** | 1 (1.3) | 20 (27) | < .001 |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Cardiac tamponade | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Need for pacemaker implantation | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Final flow compromise (TIMI ≤ 2) in SB | 0 | 2 (2.7) | NS |

| MACCE (4.08 years, ICA: 3.18-4.78) | |||

| GLOBAL: 27 (36.4%) | 18 (25%) | 30 (40.6%) | .03 |

| Overall death rate | 15 (20.3%) | 16 (21.8%) | NS |

| Hospitalization | 3 (4%) | 3 (4%) | NS |

| 30 days | 4 (5.4%) | 5 (6.7%) | NS |

| Cardiac Death | 5 (6.7%) | 7 (9.4%) | NS |

| Non-cardiac Death | 9 (12.1%) | 7 (9.4%) | NS |

| Stroke | 2 (2.7%) | 7 (9.4%) | .02 |

| TVF | 9 (12.1%) | 18 (24.8 %) | .04 |

| TLR | 2 (2.7%) | 11 (14.8%) | .02 |

| TVR | 3 (4%) | 7 (9.4%) | .03 |

| TBR | 2 (2.7%) | 7 (9.4%) | .03 |

| Stent thrombosis | 0 | 0 | NS |

|

ICA, interquartile amplitude; MACCE, major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events; NS, not significant; RAPS, rotational atherectomy and provisional stenting; SS, standard strategy; TBR, target bifurcation restenosis; TLR, target lesion restenosis; TVF, target vessel failure (composite of cardiac death, culprit vessel myocardial infarction); TVR, target vessel restenosis. * Shift plaque defined as ostial side-branch stenosis > 70% and/or TIMI flow < 3. ** Treatment included: a) angioplasty with conventional or drug-eluting balloon; b) bare-metal stent or drug-eluting stent. |

|||

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The main findings of this study are: a) the RAPS strategy for the management for CBLs minimizes the compromise of the SB, need for SB therapy, and TVF compared to the SS; b) There was a strong correlation between the compromise of the SB and acute CBL angles (< 70º); c) The SS was associated with a 4.92-fold higher risk of SB compromise compared to the RAPS strategy in CBL angles < 70º.

CBLs are a common thing in our interventional practice and can be challenging in our routine clinical practice. Side-branch compromise is still the most important problem. To our knowledge, this is the first randomized study that addressed this issue and described the role of RA in the management of CBLs. Former studies not specifically designed to address this specific question had already suggested this.8,9,12,13 We reported sustained short-term benefits of the RAPS strategy at the long-term follow up. Some differences had been previously reported,14 which is why differences in the primary endpoint could be expected, but still not so significant.

As a hypothesis-generating pilot study we defined a procedural primary endpoint.11 Selecting a “procedural” primary endpoint at this stage is a reasonable thing to do since the occlusion of large SBs is a serious complication that leads to adverse clinical outcomes.11,14 We studied whether the RAPS strategy could be as good as the SS for the management of CBL by comparing the compromise of the SB.15-17 Still, the current clinical practice guidelines minimize the indications for RA to heavily calcified lesions and rigid ostial lesions,10 although an expert consensus document recently published includes more extensive indications.6 The real-world use of RA for plaque modification in is nothing new.9 Actually, in the absence of plaque modification there are more chances of procedural failure, stent underexpansion, in-stent restenosis, and major clinical complications.2,5,18 Schwartz et al use it in up to 26% of their population.9

Percutaneous coronary intervention and bifurcation technique

Only BLMVs were included.19 Bifurcations are true bifurcations when a significant SB runs the risk of being compromised regardless of whether the disease reaches it or not. Thus, maybe we should rename them as “complex CBLs”, that is, those where the SB has baseline disease (1.1.1 in the Medina classification) and “simple CBLs”, those without baseline disease (again according to the Medina score). There is wide consensus that the main objective of complex PCIs in the management of CBLs is to keep the patency of both vessels regardless of the PCI technique used and the location of the lesion.2 For many years we have been focused on the optimization of SB, but clinical events such as TLR mostly occur in the main vessel.20 In up to 20% of the cases, the SB requires a stent, which means that the proper preparation of the CBL is essential.3,14,21

What the best bifurcation technique is for the management of CBL is still under discussion. Currently, the standard strategy recommended for the management of CBL is a 1-stent technique.2,4 Ideally, the technique selected should provide an easy access for a second stent in the SB even if conventional approach with a 1-stent technique is planned. In our cohort, the RA facilitated this approach. According to cumulative clinical trial data3 we reported a high rate of provisional stenting in the RAPS strategy that proved non-inferior to the elective 2-stent technique4,5 and ever better for the management of periprocedural myocardial infarction.22 The kissing balloon technique is being systematically used in cases of large territories supplied by the SB or when the SB exhibits flow impairment after MV stenting. Sometimes, in such situations a second stent is implanted in the SB.23 The differences reported in our population regarding the optimal treatment of the proximal LAD and final kissing balloon and 2-stent technique used are still under discussion. We saw a 4-fold higher rate of the balloon technique in the SS. Maybe these differences were due to the tight lesions described: in the SS there was a need of a step-up ballooning to cross and dilate the lesions and eventually for the final optimization of the stents. Eventually, at least 3 or 4 balloons were needed. Interestingly, as previously reported, when the final kissing balloon technique was used, the optimal treatment of the proximal LAD produced no benefit at all.24 Maybe this was the case because the stent located in the main vessel is properly expanded after using the kissing balloon technique. We saw a lower need for SB treatment and TVF rates7,18,25 in the RAPS strategy than previously reported.

Role of rotational atherectomy for the management of bifurcation lesions

The RAPS strategy facilitates the modification of the plaque without SB compromise by extending provisional stenting2,4 by a) minimizing plaque shift, b) optimizing plaque modification, c) reducing the need for 2 wires/stents and d) improving the stent expansion/apposition. Otherwise, certain maneuvers used in other strategies to avoid the occlusion of the SB may cause suboptimal stent expansion/apposition in the MV, which can be a major cause for stent thrombosis and restenosis.2,14 The bifurcation angle has been suggested as an important issue for the compromise of the SB.5,11,14 In our population, the LAD was the most commonly affected coronary artery. The LAD is particularly appealing given the angle of the origin of the diagonals. The crux is often at a right angle so it is less of a concern and the circumflex artery only matters when it is dominant. Acute CBL angles (< 70º) have shown to increase the compromise of the SB and, therefore, lead to worse outcomes. In our cohort, “SB compromise”, “need for SB therapy”, and TVF rates were lower in CBL angles < 70º both in the RAPS and the SS groups. The small size of the sample prevented us from drawing definitive conclusions, but these data were good enough to make us change our daily methodology: with CBL angles < 70º located in the main vessel with a large side-branch we use directly the RAPS technique. Maybe the explanation for the differences seen in the RAPS vs the standard strategy is the underlying mechanism of action of rotational atherectomy. As a matter of fact, this may explain the higher rates of SB compromise and need for SB therapy seen in the SS group: a more controlled plaque modification was achieved with RA that minimized the plaque shift. Unfortunately, our data did not include too many imaging modalities. In our cohort for events assignment, if during the PCI procedure any narrowing occurred adjacent to, and/or involving the origin of a significant SB it was allocated to the selected strategy used. The decision to use the 1-stent or 2-stent technique, the type of stent, etc. was left to the operator’s discretion. We should make a few comments on our study population: a) although most of the patients were unstable, this did not condition the results in any of the groups; b) in the RAPS strategy the use of the jailed wired technique is rare; c) CBL angles < 70º between branches facilitate the plaque shift.26 Thus, if the TIMI flow recorded after stent deployment was < 3 or residual stenosis was > 70% more bail-out balloons and stents were needed, which would explain the different outcomes seen when using the final kissing balloon technique; d) in a number of cases where the standard strategy was used it was complemented with the kissing balloon inflation technique at high-pressure balloon inflation instead of the final optimal treatment of the proximal LAD; and e) the differences seen in the coronary dissection rate on the angiographic study may be suggestive of micro-dissections due to inadequate balloon assessment through conventional angiography, which could be the underlying mechanism of the endpoint differences reported; performing more intravascular ultrasound/optical coherence tomography studies would provide better assessment here.

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio so the differences seen in the left ventricular ejection fraction and LAD disease were absolutely due to the size of the study sample. Although we saw a lower cardiovascular mortality rate compared to the one published in the medical literature2,14,15,27 this study was not designed to compare the MACCE results between both groups. Interestingly, the rates of TVF were significantly lower in the RAPS strategy mainly due to fewer culprit vessel myocardial infarctions and target vessel restenoses. In any case, our data underscored the safety profile of the RAPS strategy in unstable patients and patients with left ventricular dysfunction (P = .03)

Limitations

We designed and conducted a single-center pilot study. Small sample sizes have inherent limitations. Our results should be interpreted with caution as a hypothesis-generating pilot study. Several confounding factors and biases could be present, which is why any assessments on this regard should be made with caution too. The study was extremely underpowered to show clinical outcome differences, which is why the clinical findings reported should be considered just exploratory. Our procedural endpoint and inclusion of BLMVs only could be discussed. There is wide consensus that the main objective of complex PCsI for the management of CBLs is to keep both vessels patent regardless of the PCI technique used.2

We thought it was the right thing to do to assess the data on the SB compromise by comparing both techniques used. Over thec years we have been focusing on optimizing the SB, but clinical events such as TLR mostly occur in the main vessel.20 Only BLMVs were included.19 A bifurcation should be considered as a true bifurcation when a significant SB you do not want to lose is compromised whether it shows coronary stenosis or not. We should mention that in the management of CBLs with the RAPS strategy a low rate of SB stenting is associated with a lower rate of major adverse events and clinically significant rates of restenosis. Therefore, very large numbers of patients are required for the proper assessment of the differences. Some baseline characteristics of coronary lesions vary depending on the interventional strategy used (as in the management of B2C lesions) to the point of impacting the final outcomes. The lack of differences seen in the stent thrombosis and stroke rates may be associated with the size of the study sample.

Although statistical significance was not observed, the percentage of bare metal stents used was numerically higher in the control group compared to the RAPS group. However, this study is not a comparison of drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents in bifurcation disease. These findings could be associated with the difference seen in TLR/target vessel restenosis, especially if we take into account that 31.2% of patients from the control group were treated using 2-stent techniques. We saw that RA followed by drug-eluting stents was associated with a low rate of MACCE compared to bare-metal stents. However, this study was not designed to make comparisons like this one. A higher percentage of bivaluridin was intentionally used in the RAPS group, but this did not produce any statistically significant differences. The use of more imaging modalities such as intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography is desirable here. FUP was mostly conducted through phone calls and it may have underestimated the rate of MACCE. An off-label indication does not necessarily mean a contraindication of our promising, but support for the next step: a large randomized multicenter trial that is about to begin.

CONCLUSIONS

The RAPS strategy for the management of CBL preserves the SB ostium and minimizes the need for SB therapy compared to the SS. The rates of “SB compromise”, “need for SB therapy”, and TVF were higher with CBL angles < 70º for both the RAPS and the SS groups. Our data reinforce the idea of the overall clinical relevance of the RAPS strategy to keep the SB patent. Although no large clinical trials have taken this approach yet, the results published so far are promising.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J. Palazuelos (corresponding author) is a consultant on the speaker’s bureau of Abbott, Boston Scientific, Biotronik, Innovative Health Technologies (IHT) and Medtronic. J. Palazuelos is a proctor for Rotational Atherectomy with a teaching contract with Boston Scientific that has funded this study with a grant. No other relation with the industry regarding this study was declared. He confirms he has had full access to all the study data and holds full responsibility for the decision to submit this manuscript for publication in Rec: Interventional Cardiology. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever regarding the contents of this manuscript.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Over the last few years, the profile of patients referred to undergo a coronary angiography has become worse. Similarly, angiographic findings have become worse as well. With the progressive ageing of the population and the arrival of better technologies, the balance between offer and demand in this field is in continuous expansion. Still, the management of such delicate situations requires profound knowledge of dedicated techniques and accurate clinical judgement. Calcified coronary lesions and bifurcated lesions are a common occurrence that accounts to between 25% and 30% of all PCIs. There are technologies available for the management of these lesions. The older one is rotational atherectomy. Currently, the objective is to modify the plaque since the lack of plaque modification is associated with more procedural failure, stent underexpansion, in-stent restenosis, and major clinical complications. Despite the existence of well-defined techniques for the use of PCI for the management of CBLs, side-branch compromise is still the most important complication.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The role of rotational atherectomy for the management of coronary bifurcation lesions has been suggested in different studies not specifically designed for that purpose. Our randomized data support the role of the RAPS strategy for the management of BLMV in a cohort of high-risk patients. The RAPS strategy provided higher SB patency and lower TVF. Still, larger studies are needed to shed light on this question.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Video 1. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 2. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 3. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 4. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 5. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 6. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

Video 7. Palazuelos J. H. DOI: 10.24875/RECICE.M20000138

REFERENCES

1. De Maria GL, Scarsini R, Banning AP. Management of Calcific Coronary Artery Lesions. Is it time to change our interventional therapeutic approach?JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1465-1478.

2. Lassen JF, Burzotta F, Banning AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for the left main stem and other bifurcation lesions:12th consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention. 2018;13:1540-1553.

3. Gao X-F, Zhang Y-J, Tian N, et al. Stenting strategy for coronary artery bifurcation with drug-eluting stents:a meta-analysis of nine randomized trials and systematic review. EuroIntervention. 2014;10:561-569.

4. Colombo A, Jabbour RJ. Bifurcation lesions:no need to implant two stents when one is sufficient!Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1929-1931.

5. Nairooz R, Saad M, Elgendy IY, et al. Long-term outcomes of provisional stenting compared with a two-stent strategy for bifurcation lesions:a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Heart. 2017;103:1427-1434.

6. Barbato E, CarriéD, Dardas P, et al. European expert consensus on rotational atherectomy. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:30-36.

7. Ito H, Piel S, Das P, et al. Long-term outcomesof plaque debulking with rotational atherectomy in side-branch ostial lesions to treat bifurcation coronary disease. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:598-601.

8. Warth DC, Leon MB, O'Neill W, Zacca N, Polissar NL, Buchbinder M. Rotational atherectomy multicenter registry:acute results, complications and 6-month angiographic FUP in 709 patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:641-648.

9. Schwartz BG, Mayeda GS, Economides C, Kloner RA, Shavelle DM, Burstein S. Rotational atherectomy in the drug-eluting stent era:a single-center experience. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011;23:133-139.

10. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

11. Burzotta F, Trani C, Todaro D, et al. Prospective Randomized Comparison of Sirolimus- or Everolimus-Eluting Stent to Treat Bifurcated Lesions by Provisional Approach. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:327-335.

12. Nageh T, Kulkarni NM, Thomas MR. High-speed rotational atherectomy in the treatment of bifurcation-type coronary lesions. Cardiology. 2001;95:198-205.

13. Dai Y, Takagi A, Konishi H, et al. Long-term outcomes of rotational atherectomy in coronary bifurcation lesions. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:2375-2383.

14. Hahn JY, Chun WJ, Kim JH, et al. Predictors and outcomes of side-branch occlusion after main vessel stenting in coronary bifurcation lesions:results from the COBIS II Registry (COronary BIfurcation Stenting). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1654-1659.

15. Tomey MI, Kini AS and Sharma SK. Current Status of Rotational Atherectomy. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:345-53.

16. Ellis SG, Popma JJ, Buchbinder M, et al. Relation of clinical presentation, stenosis morphology, and operator technique to the procedural results of rotational atherectomy and rotational atherectomy-facilitated angioplasty. Circulation. 1994;89:882-892.

17. Furuichi S, Sangiorgi GM, Godino C, et al. Rotational atherectomy followed by drug-eluting stent implantation in calcified coronary lesions. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:370-374.

18. Abdel-Wahab M, Baev R, Dieker P, et al. Long-Term Clinical Outcome of Rotational Atherectomy Followed by Drug-Eluting Stent implantation in Complex Calcified Coronary Lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2013;81:285-291.

19. Medina A, Suarez de Lezo J, Pan M. A new classification of coronary bifurcation lesions. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2006;59:183.

20. Gwon HC. Understanding the Coronary Bifurcation Stenting. Korean Circ J. 2018;48:481-491.

21. Vaquerizo B, Serra A, Miranda F, et al. Aggressive plaque modification with rotational atherectomy and/or cutting balloon before drug-eluting stent implantation for the treatment of calcified coronary lesions. J Interv Cardiol. 2010;23:240-248.

22. Song PS, Song YB, Yang JH, et al. Periprocedural myocardial infarction is not associated with an increased risk of long-term cardiac mortality after coronary bifurcation stenting. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1251-1256.

23. Burzotta F, Sgueglia GA, Trani C, et al. Provisional TAP-stenting strategy to treat bifurcated lesions with drug-eluting stents:one-year clinical results of a prospective registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2009;21:532-537.

24. Kim MC1, Ahn Y, Sim DS, et al. Impact of Calcified Bifurcation Lesions in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Drug-Eluting Stents:Results From the COronary BIfurcation Stent (COBIS) II Registry. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:338-344.

25. Benezet J, Diaz de la Llera LS, Cubero JM, Villa M, Fernandez-Quero M, Sanchez-Gonzalez A. Drug-eluting stents following rotational atherectomy for heavily calcified coronary lesions:long-term clinical outcomes. J Invasive Cardiol. 2011;23:28-32.

26. Koo BK, Waseda K, Kang HJ, et al. Anatomic and functional evaluation of bifurcation lesions undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:113-119.

27. García de Lara J, Pinar E, Ramón Gimeno J, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in heavily calcified lesions using rotational atherectomy and paclitaxel-eluting stents:outcomes at one year. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2010;63:107-110.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Between 10% and 25% of patients hospitalized due to an acute coronary syndrome develop acute kidney injury, a condition associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates. Scores have been developed to predict the occurrence of post-coronary angiography contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) in patients with acute coronary syndrome. The objective of this study was to assess the association between microalbuminuria and post-coronary angiography CIN in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

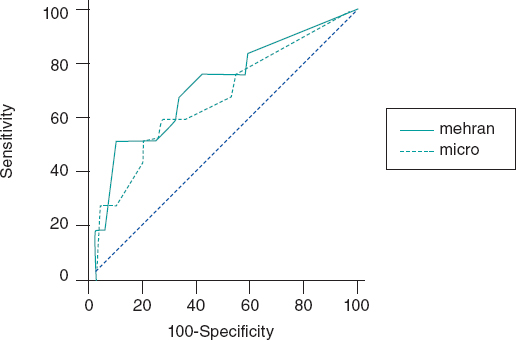

Methods: Patients admitted with acute coronary syndrome in whom a coronary angiography was performed during their hospitalization and with urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) assessment within the first 24 hours were analyzed. The best ACR cutoff value for coronary angiography-induced CIN was determined using the C-statistic measure. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were built to compare between the predictive ability of the Mehran score alone and also in combination with the ACR.

Results: A total of 148 patients were analyzed. Median age was 64 years (56-73), 35% were women, mean creatinine clearance rate at admission was 86 mL/min (66-107) and the ACR was 5 mg/g (0-14). The analysis showed that 9.6% of the patients developed post-coronary angiography CIN with ACR levels ≥ 20 mg/g compared to 1.6% when these levels were < 20 mg/g. The area under the ROC curve of the Mehran score to predict the development of post-coronary angiography CIN was 0.75 (95%CI, 0.68-0.81) and when the ACR was added it went up to 0.82 (95%CI, 0.76-0.87).

Conclusions: The ACR levels at admission were associated with the development of post-coronary angiography CIN and bring added value to an already validated predictive score. Therefore, the ACR should be used as a simple and accessible tool to detect and prevent this severe complication in patients with acute coronary syndrome.

Keywords: Contrast media. Coronary angiography. Microalbuminuria. Contrast-induced nephropathy. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Entre el 10 y el 25% de los pacientes hospitalizados por síndrome coronario agudo desarrollan insuficiencia renal aguda, lo que aumenta la morbimortalidad. Existen escalas para predecir la aparición de nefropatía inducida por contraste (NIC) tras la realización de una angiografía coronaria en pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la asociación entre el índice albúmina-creatinina (IAC) urinario y el desarrollo de NIC tras una angiografía coronaria en pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo.

Métodos: Se analizaron pacientes internados por síndrome coronario agudo a quienes se realizó angiografía coronaria durante el ingreso, con el cálculo del IAC en las primeras 24 horas. Se determinó el mejor valor de corte por curva ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic)del IAC asociado a NIC. Se compararon las curvas ROC de la escala de Mehran sola y con el agregado de la variable de IAC.

Resultados: Se analizaron 148 pacientes. La mediana de la edad fue de 64 años (56-73), el 35% eran mujeres, el aclaramiento de creatinina fue de 86 ml/min (66-107) y el IAC de 5 mg/g (0-14). El 9,6% de los pacientes desarrollaron NIC tras la angiografía coronaria cuando su IAC fue ≥ 20 mg/g y el 1,6% cuando fue < 20 mg/g. El área bajo la curva ROC de la escala de Mehran para predecir el desarrollo de NIC tras la angiografía coronaria fue de 0,75 (intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 0,68-0,81); cuando se agregó la variable de IAC fue de 0,82 (IC95%, 0,76-0,87).

Conclusiones: El IAC basal se asoció con el desarrollo de NIC tras la angiografía coronaria. Al añadirlo a la escala de Mehran aumentó la capacidad discriminativa. El IAC podría ser una herramienta de simple uso, bajo costo y amplia disponibilidad para detectar pacientes en riesgo de desarrollar NIC y adoptar medidas preventivas apropiadas.

Palabras clave: Contraste intravenoso. Angiografía coronaria. Microalbuminuria. Nefropatía inducida por contraste. Índice albúmina-creatinina urinario.

Abbreviations:

ACR: Albumin-to-creatinine ratio. ACS: Acute coronary syndrome. AKI: Acute kidney injury. CIN: Contrast-induced nephropathy.

INTRODUCTION

Renal function impairment is associated with poor prognosis in patients with stable or acute coronary syndrome (ACS). One of the most common causes of acute kidney injury (AKI) in hospitalized patients is the nephropathy induced by the IV administration of contrast agents.1Its incidence varies between 1% and 6%, and increases considerably in high-risk conditions like in the ACS setting. The reported frequency of post-coronary angiography contrast-induced nephropathy (CIN) goes from 12% to 46% in patients with ACS.2,3

There are several potential causes that trigger CIN in patients without a past medical history of kidney failure such as hemodynamic instability, the IV administration of contrast agents, thromboembolic events, and adverse drug reactions, among others. Also, it is important to consider the type of contrast used, its osmolarity, the volume administered, and the lack of preventive measures.4-6

Because CIN is associated with poor prognosis in hospitalized patients, predictive scores have been designed to identify the most vulnerable patients who can develop this complication. The Mehran score is one of the most popular indices to estimate the chances of post-coronary angiography CIN.7

It is well-established that microalbuminuria is a predictor of kidney dysfunction mainly in diabetic and hypertensive patients.8-14Also, there is a correlation between high levels of microalbuminuria and the poor outcomes seen in patients with ACS.15-16 Currently, microalbuminuria is estimated through the dosage of the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) through a simple urine sample.17

The objective of this study is to calculate microalbuminuria using the ACR as a predictive variable of post-coronary angiography CIN in patients with ACS.

METHODS

Population

Patients with ACS consecutively admitted to the coronary care unit of a community hospital were analyzed. Those undergoing an in-hospital coronary angiography with non-ionic, hyperosmolar IV contrast agents such as iopamidol, optiray or xenetix, were included in the study. The volume of IV contrast for each angiographic study was calculated retrospectively. It was estimated that each injection of contrast material into the left coronary artery required an average 10 cc to 8 cc for the right coronary artery.

Patients with a past medical history of renal failure, macroalbuminuria, treatment with diuretics and patients with secondary angina were excluded from the study.

The urinary ACR was assessed in all patients included in the study using an immunoturbidimetric assay in simple urine samples within the first 24 hours after hospitalization.

Definitions

IV contrast-induced nephropathy(CIN) was defined as an increase in serum creatinine levels ≥ 25% 48 hours after performing the coronary angiography or an absolute increase of ≥ 0.5 mg/dL compared to levels at admission.

Microalbuminuria was defined as an abnormal urinary albumin excretion rate between 30 to 200 mg/min or 30 to 229 mg/day.

The study protocol was approved by the center review board and conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, good clinical practice guidelines, and local regulatory requirements. Informed consents were obtained from all patients.

Biochemical considerations

A urine sample collected within the first 24 hours after admission (preferably during morning hours) was centrifuged at 3000 rpm and stored at -20° Celsius until biochemical analysis was conducted. The principle of the ACR test is immunoturbidimetry. This method is based on the reaction of human albumin antibodies to the antigen. Complexes are then measured after agglutination. The COBAS 6000 analyzer (ROCHE, Switzerland) was used to process the sample. The analytical detection limits of the assay were between 3 mg/g and 400 mg/g. The test variation coefficient was 3.8%.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to analyze the distribution of continuous variables and their kurtosis-skewness measures. Data were expressed as mean and standard deviation or as median with interquartile range (25%-75%) and compared using Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for independent groups according to their parametric or non-parametric distribution, respectively.

Discrete variables were expressed as percentages and compared using the chi-square test. The cross-product ratio was expressed as odds ratio (OR) with its 95% confidence interval (95%CI). The C-statistic measure was used to detect the best ACR cutoff value associated with the primary endpoint and compare the discrimination capacity of the Mehran score alone and with the ACR combined.

A multivariable regression analysis will be built to predict CIN including ACR and adjusted using the Mehran score.

Both the IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 software and the MedCalc version 11.6.1 software (Mariakerke, Belgium) were used for statistical analysis and to calculate and compare the C-statistic measure. To test the additional predictive value of ACR, the C-statistic measurewas compared using the Mehran score alone and after adding the ACR information obtained.

RESULTS

Out of a total of 397 patients diagnosed with ACS, 148 (59.4%) underwent a coronary angiography during hospitalization and this was the study population. The mean age was 64 ± 12 years; 35% were women, 20% had diabetes, 54% dyslipidemia, 65% hypertension, and 42% were active smokers. The mean blood sugar levels on admission were 110 mg/dL (98-133 mg/dL), the median creatinine clearance rate (estimated using the MDRD) was 86 mL/min (66-107), and the ACR was 5 mg/g (0-14) (table 1). The patient comparison between these groups with or without CIN showed a higher rate of overweight and obesity, left bundle branch block, atrial fibrillation, and AMI Killip and Kimball class III-IV (table 2).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Total number of patients | N = 148 |

|---|---|

| Age (years), median [25-75] | 64 [56-73] |

| Women | 35 |

| Hypertension | 65 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 20 |

| Dyslipidemia | 54 |

| Smoking | 42 |

| Previous AMI | 24.5 |

| STEAMI | 20.9 |

| NSTEACS | 79.1 |

| Fasting blood glucose levels, mg/dL | 110 [98-133] |

| Serum creatinine levels, mg/dL | 0.9 [0.8-1.0] |

| Creatinine clearance rate, mL/min | 86 [66-107] |

| Urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, mg/gr | 5 [0-14] |

| CPK, IU/L | 121 [73-264] |

| CK-MB, IU/L | 16 [12-34] |

| Troponin T levels, ng/mL | 0.01 [0.01-0.27] |

| Moderate to severe LVSF impairment (EF < 40%) | 5.79 |

|

Unless specified otherwise, data are expressed as % or mean and standard deviation. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; CK-MB, creatine kinase myocardial band; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; EF, ejection fraction; IQR, interquartile range; IU, international units; LVSF, left ventricular shortening fraction; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

|

Table 2. Comparison of patients with and without contrast-induced nephropathy

| CIN - (136) | CIN + (12) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 63.7 [55-74] | 68 [61-76] | NS |

| Women | 25.3 | 16.7 | NS |

| Hypertensive | 67.7 | 58.3 | NS |

| Diabetic | 20 | 33.3 | NS |

| Body mass index | 26 [24-29] | 29 [25-31] | .05 |

| Creatinineclearence rate mg/dL | 85 [65-108] | 74 [50-98] | NS |

| Blood glucose levels at admission, mg/dL | 112 [100-142] | 143 [108-209] | NS |

| Previous AMI | 26 | 16 | NS |

| Previous PCI | 17 | 8.3 | NS |

| Previous stroke or TIA | 3.6 | 8.3 | NS |

| NSTEACS | 17.7 | 25 | NS |

| STEMI | 30.8 | 33.3 | NS |

| Left bundle branch block | 3.6 | 16.7 | .02 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.9 | 8.3 | .02 |

| Killip and Kimball III-IV | 4.1 | 22 | .001 |

|

Unless specified otherwise, data are expressed as % or mean and standard deviation 25%-75%. ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ARA II, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CK-MB, creatine kinase myocardial band; CPK, creatine phosphokinase; EF, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate; IQR, interquartile range; IU, international units; LVSF, left ventricular shortening fraction; NS, not significant; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIA, transient ischemic attack. |

|||

The C-statistic measure showed that the best CIN related ACR cutoff value was 20 mg/g. Twelve patients developed CIN (8.1%) and the ACR of 22% of the patients was >20 mg/g. The rate of ACR > 20 mg/g among patients without CIN was 2.9% and 11.3% (P = .01) among patients with CIN. Contrast-induced nephropathy was significantly higher when the ACR was ≥ 20 mg/g compared to when it was < 20 mg/g (≥ 9.6% vs 1.6%, res- pectively, P < .001). When the ACR was added to the Mehran score, its predictive power went up to 0.82 (95%CI, 0.76-0.87).(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Effect of albumin-to-creatinine ratio when added to the Mehran score. When the albumin-to-creatinine ratio was added to the Mehran score, its predictive power went up from 0.75 to 0.82 (95%CI, 0.76-0.87).

Using a multivariable regression analysis model the ACR > 20 mg/g turned out to be an independent predictor for CIN: OR, 3.2 (0.7-6.2); P = .01, adjusted by the Mehran score variables (age, women, body mass index, atrial fibrillation, Killip Class III-IV, and creatinine clearance rate).

DISCUSSION

Our study proved the association between the ACR and the development of CIN in patients admitted with ACS.

Acute kidney injury in the ACS setting predisposes to more complications such as in-hospital and long-term mortality; therefore, predicting it is of critical clinical importance. A recent study reported that the rate of AKI was close to 17% in the ACS setting with significant peaks of cardiovascular complications. In this study, the ACR was not used as an early marker of AKI. The development of CIN was not specifically analyzed either as a post-coronary angiography complication.18-22

Microalbuminuria calculated through the ACR obtained from a simple urine sample is also an established marker of endothelial dysfunction that has been validated to predict cardiovascular events and mortality in different clinical settings. A previous analysis of our group revealed that higher ACR levels are associated with significantly worse outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, and with a higher rate of hard endpoints like mortality and/or non-fatal acute myocardial infarction at the long-term follow-up (12% vs 2.2%, P =/< .0001).23 Also, other authors proved its utility to assess the risk of developing AKI, mainly in the ACS setting or while being exposed to cardiac surgery.24Tziakas et al confirmed the significant correlation between AMI related higher ACR levels and the development of AKI after this event (area under the ROC curve 0.72; 95%CI, 0.67-0.77). However, the authors did not report on the clinical impact of this complication on the patient’s clinical course or its association with the use of contrast during coronary angiography.25

Special attention should be paid to patients with post-angiographic AKI in the ACS setting. Several studies have shown that CIN negatively impacts the prognosis of hospitalized and long-term patients. In our population, mortality in patients with CIN was significantly higher compared to those without this disease (33% vs 1.8%).

The use of urinary ACR has been less studied in this context. Meng et al. reported that high microalbuminuria levels (ACR in between 30 mg/g and 300 mg/g) were associated significantly with the development of post-contrast acute kidney injury in patients undergoing coronary catheterization (12.1% vs. 5.0%; P = .005). A key point here that distinguishes this study from ours is that they included patients with scheduled coronary angiographies only and out of the ACS setting.26Another relevant point is that the ACR cutoff value to develop CIN was determined from the analysis of the area under the ROC curve, and its value of 20 mg/g was even lower compared to the conventional standard threshold of 30 mg/g, a finding that was consistent with what other clinical studies reported.27

The rate of CIN and its impact on the clinical outcome of coronary patients triggered the development of predictive scores for this disease. One of the best known indices is the Mehran score that includes variables like age > 75 years, hypertension, functional class III/IV heart failure, diabetes mellitus, anemia, use of intra-aortic balloon pump, volume of contrast administered, and past medical history of renal dysfunction and is capable of identifying who the most vulnerable patients are to develop post-coronary angiography CIN (the area under the ROC curve was 0.75). Adding the ACR to this score showed an even greater discriminatory power to predict post-coronary angiography CIN in patients with ACS. This would prove the practical utility of adding this index as a variable to the Mehran score.

CIN, one of the most common causes for acute nephrotoxicity, is a multi-factor event. Among its causes we should mention the direct nephrotoxic effect of the contrast substances used during endovascular procedures on the renal endothelium and the development of acute tubular necrosis. It is estimated that the nephrotoxicity of hyperosmolar contrast enhanced by the hemodynamic alterations produced by the ongoing ACS could alter vascular resistance with changes in the regulation of the release and balance of vasoactive substances like adenosine, endothelin, and nitric oxide. The damage perpetuates the slowing down of renal perfusion, spinal hypoxemia, ischemic injury, and ultimately cell death. In addition to reducing the clearance of oxidative stress products, the lower glomerular filtration rate levels increase the concentration of inflammatory mediators triggering structural alterations at renal tubular epithelium level like edema, vacuolization, and death.28,29

We believe that these findings could help identify patients at high-risk of developing post-coronary angiography CIN in the ACS setting to promote preventive measures, behaviors, and strategies to avoid this complication.

Limitations

First, one of the main limitations of our work is its single center nature. However, we should mention that the population included was representative and covered the entire spectrum of patients with ACS admitted to our coronary care unit, which secures the internal validity and representativeness of our study. Secondly, the underpowered sample may have conditioned the appearance of false negative results due to its alpha error or lower power and stopped us from performing a proper multivariable analysis. Finally, certain data such as the volume of contrast used in each study was calculated retrospectively with the usual biases of this type of analysis.

CONCLUSIONS

The albumin-to-creatinine ratio, a recognized predictor of renal and endothelial dysfunction, was also a marker of CIN in patients with ACS with an added value when it was included in a widely validated clinical score. These results may be the beginning of a hypothesis-generating study to be confirmed prospectively at a multi-center level.

FUNDING

No funding or grants were received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank the entire staff of the Hospital Alemán Coronary Care Unit, particularly the nursing staff who helped collect the urine samples that were crucial to conduct this study.

WHAT’S KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- CIN is one of the most common causes for AKI in hospitalized patients. Microalbuminuria is an established marker of endothelial dysfunction and has been validated to predict cardiovascular events and mortality in different clinical settings. The ACR is useful to assess the risk of developing CIN basically in the ACS setting or while exposed to cardiac surgery.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Our study proved the association that exists between the ACR and the development of post-coronary angiography CIN in patients admitted with ACS. The C-statistic measure showed that the best CIN related ACR cutoff value was 20 mg/g. The ACR brings an added value when included in the Mehran score to assess the risk of developing post-coronary angiography CIN in the ACS setting.

REFERENCES

1. Hsiao PG, Hsieh CA, Yeh CF, et al. Early prediction of acute kidney injury in patients with acute myocardial injury. J Crit Care. 2012;27:525.e1-e7.

2. McCullough PA. Contrast-induced acute kidney injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1419-1428.

3. Mehran R, Nikolski E. Contrast-induced nephropathy:Definition, epidemiology, and patients at risk. Kidney International. 2006;69:S11-S15.

4. Parikh CR, Coca SG, Wang Y et al. Long-term prognosis of acute kidney injury after acute myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:987-995

5. Persson PB, Hansell P, Liss P. Pathophysiology of contrast medium-induced nephropathy, Kidney Int. 2005;68:14-22.

6. Tsai TT, Patel UD, Chag TI, et al. Contemporary incidence, predictors and outcomes of acute kidney injury in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions:insights from the NCDR Cath-PCI Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1-9.

7. Mehran R, Aymong ED, Nikolsky E, et al. A simple risk score for prediction of contrast-induced nephropathy after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1393-1399.

8. Mogensen CE, Christensen CK. Predicting diabetic nephropathy in insulin-dependent patients. N Engl J Med. 1984;31:89-93.

9. Valmadrid CT, Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE. The risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity associated with microalbuminuria and gross proteinuria in persons with older-onset diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1093-1100.

10. Dogra G, Rich L, Stanton K, Watts Parving H. Microalbuminuria in essential hypertension and diabetes. J Hypertens. 1996;14:S89-S94.

11. Deckert T, Feldt-Rasmussen B, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen T, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A. Albuminuria reflects under-spread vascular damage:the steno hypothesis. Diabetologia. 1989;32:219-226.

12. Estacio RO, Dale RA, Schrier R, Krantz MJ. Relation of reduction in urinary albumin excretion to ten-year cardiovascular mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes and systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:1743-1748.

13. Stehouwer CD, Smulders YM. Microalbuminuria and risk for cardiovascular disease:Analysis of potential mechanisms. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2106-2111.

14. Bennett PH, Haffner S, Kasiske BL, et al. Screening and management of microalbuminuria in patients with diabetes mellitus:recommendations to the Scientific Advisory Board of the National Kidney Foundations from an ad hoc committee of the Council on Diabetes Mellitus of the National Kidney Foundation. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:107-12.

15. Berton G, Cordiano R, Palmieri F, Cucchini R, De Toni R, Palatini P. Microalbuminuria during acute myocardial infarction. A strong predictor for 1-year morbidity. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1466-1475.

16. Nazer B, Ray KK, Murphy SA, Gibson M, Cannon CP. Urinary albumin concentration and long-term cardiovascular risk in acute coronary syndrome patients:A PROVE IT-TIMI 22 sub-study. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2013;36:233-239.

17. Jensen JS, Clausen P, Borch-Johnsen K, Jensen G, Feldt-Rasmussen B. Detecting microalbuminuria by urinary albumin/keratinize concentration ratio. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12S2:6-9.

18. Marenzi G, Assanelli E, Campodonico J, et al. Contrast volume during primary percutaneous coronary intervention and subsequent contrast-induced nephropathy and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:170-177.

19. Rihal CS, Textor SC, Grill DE, et al. Incidence and prognostic importance of Acute Renal Failure after percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2002;105:2259-2264.

20. Garcia S, Ko B, Adabag S. Contrast-induced nephropathy and risk of acute kidney injury and mortality after cardiac operations. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;94:772-777.

21. Bouzas-Mosquera A, Vázquez-Rodríguez JM, Calviño-Santos R, et al. Contrast-Induced Nephropathy and Acute Renal Failure Following Emergent Cardiac Catheterization:Incidence, Risk Factors and Prognosis. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2007;60:1026-1034.

22. Ueda J, Nygren A, Hansell P, Ulfendahl HR. Effect of intravenous contrast media on proximal and distal tubular hydrostatic pressure in the rat kidney. Acta Radiologica. 1993;34:83-87.

23. Higa CC, Novo FA, Nogues I, Ciambrone MG, Donato MS, Gambarte MJ, Rizzo N, Catalano MP, Korolov E, Comignani PD. Single spot albumin to creatinine ratio:A simple marker of long-term prognosis in non-ST segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Cardiology J. 2016;23:236-241

24. Coca SG, Jammalamadaka D, Sint K, et al. Preoperative proteinuria predicts acute kidney injury in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:495-502.

25. Tziakas D, Chalikias G, Kareli D, et al. Spot urine albumin to creatinine ratio outperforms novel acute kidney injury biomarkers in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2015;197:48-55.

26. Meng H, Wu P, Zhao Y, et al. Microalbuminuria in patients with preserved renal function as a risk factor for contrast-Induced acute kidney injury following invasive coronary angiography. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:1063-1067.

27. Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. Effects of ramipril on cardiovascular and microvascular outcomes in people with diabetes mellitus:Results of the HOPE study and MICRO HOPE sub-study. Lancet. 2000;355:253-259.

28. Maioli M, Toso A, Gallopin M, et al. Preprocedural score for risk of contrast-induced nephropathy in elective coronary angiography and intervention. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2010;11:444-449.

29. Goldenberg I, Matetzky S. Nephropathy induced by contrast media:pathogenesis, risk factors and preventive strategies. CMAJ. 2005;172:1461-1471.

ABSTRACT

Introductionand objectives: We assessed whether the routine use of subcutaneous nitroglycerin prior to a cannulation attempt improves transradial access significantly (the NiSAR study [subcutaneous nitroglycerin in radial access]).

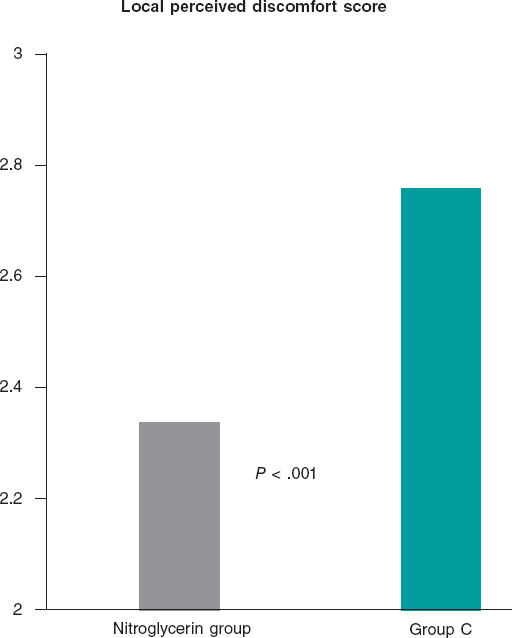

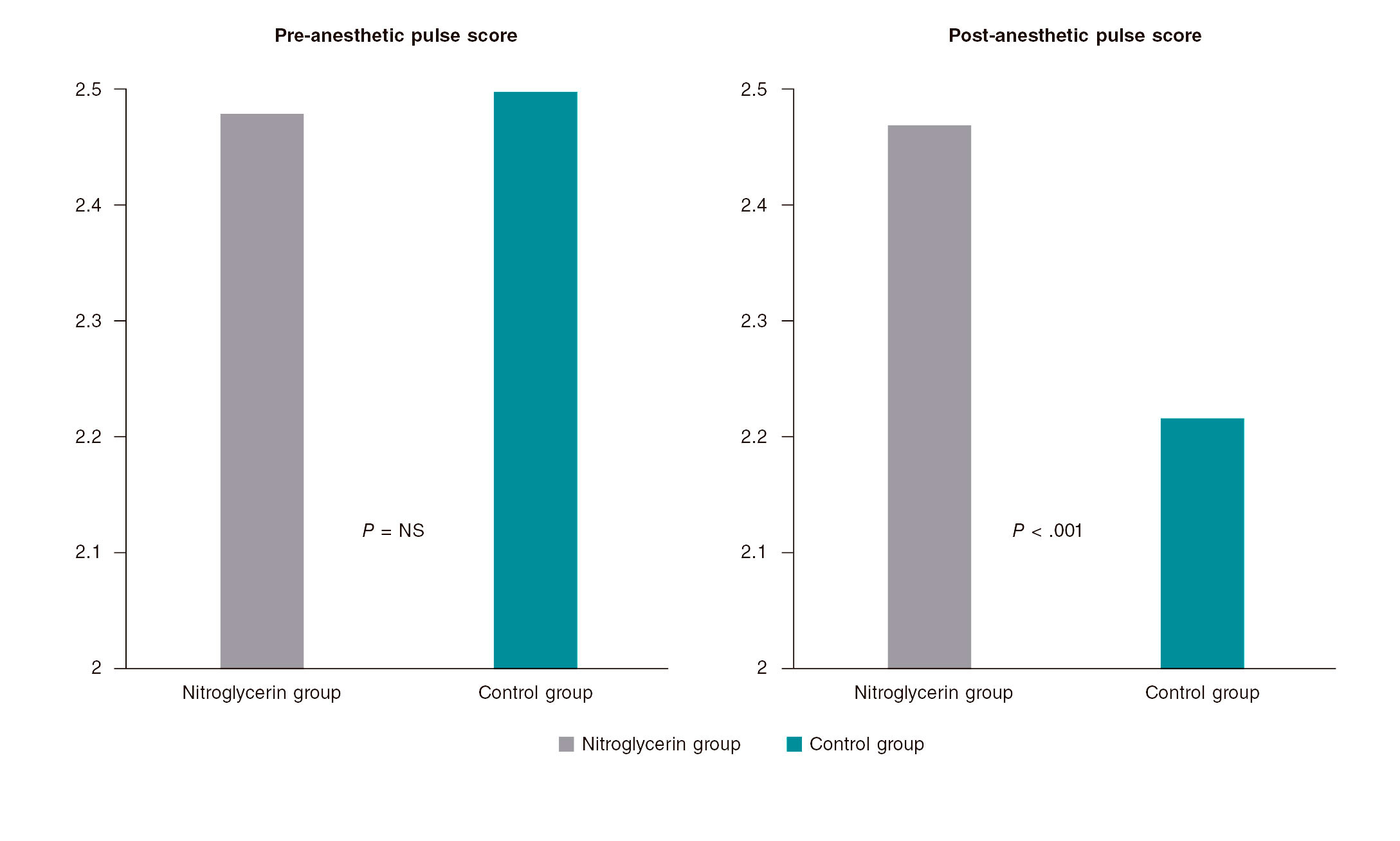

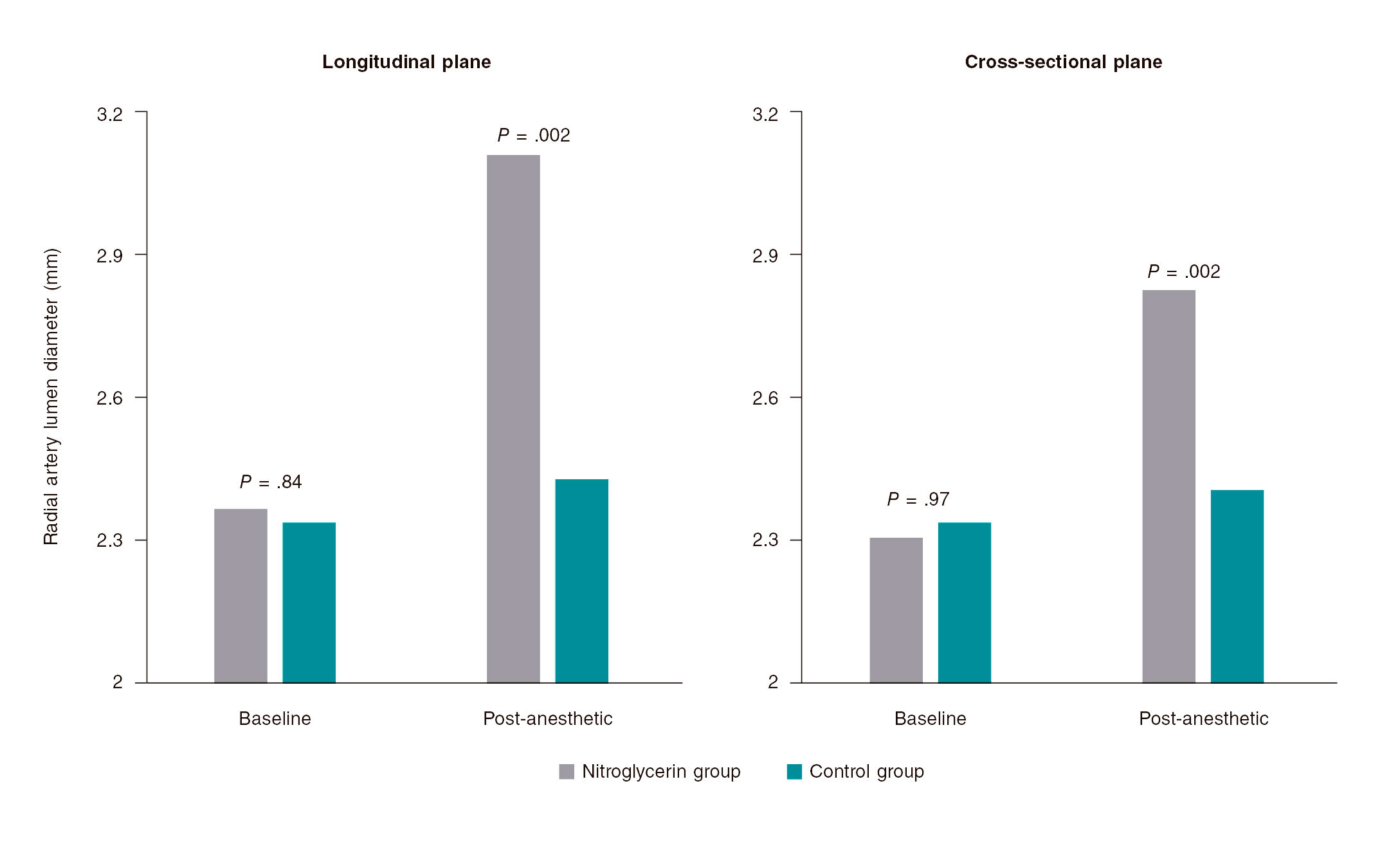

Methods: Patients undergoing a coronary angiography were enrolled in a prospective, double-blind, multicenter, randomized trial in 2 groups (nitroglycerin group vs control group). The primary endpoints were the overall number of puncture attempts, access and procedural time, switch to transfemoral access, and local perceived discomfort score. The secondary endpoints were the pre- and post-anesthetic pulse score. A subgroup of patients underwent ultrasound scans performed through the radial artery.

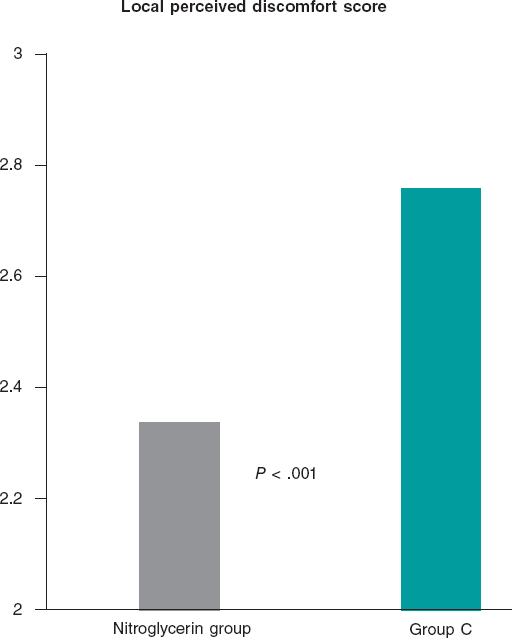

Results: 736 patients were enrolled in the trial: 379 in the nitroglycerin group and 357 in control group. The average number of puncture attempts was similar (1.70 vs 1.76; P = .42). Access and procedural time did not change significantly (61.1 s and 33.3 s vs 63 s and 33.4 s; P = .66 and P = .64, respectively). No significant differences were found either between the 2 groups in the number of switches to transfemoral access (7.1% vs 8.4%; P = .52). However, the average local perceived discomfort score and post-anesthetic pulse score were significantly better in the nitroglycerin group (2.34 vs 2.76; P< .001 and 2.47 vs 2.22; P< .001). The ultrasound scan performed through the radial artery showed post-anesthetic radial artery lumen diameters that were significantly higher in the nitroglycerin group in both the longitudinal (3.11 mm vs 2.43 mm; P = .002) and cross-sectional planes (2.83 mm vs 2.41 mm; P = .002). A trend towards fewer local hematomas in the nitroglycerin group was seen (6.1% vs 9.8%; P = .059). Headaches were more common in the nitroglycerin group (3.2% vs 0.6%; P = .021).

Conclusions: The routine use of subcutaneous nitroglycerin prior to radial puncture was not associated with fewer punctures or shorter access times. However, the lower local perceived discomfort and enlargement of the radial artery size would justify its daily use in the routine clinical practice to enhance the transradial experience for both patients and operators.

Keywords: Transradial access. Subcutaneous nitroglycerin. Radial spasm.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Se evaluó si la utilización sistemática de nitroglicerina subcutánea previa a cualquier intento de canulación podía mejorar de forma significativa el acceso transradial (nitroglicerina subcutánea acceso radial [NiSAR]).

Métodos: Se incluyeron todos los pacientes sometidos a angiografía coronaria en un estudio prospectivo, multicéntrico, doble ciego y aleatorizado, y se dividió la población en 2 grupos: grupo de nitroglicerina y grupo control. Los objetivos primarios del estudio fueron el número total de punciones radiales, el tiempo total de acceso y de procedimiento, la necesidad de cambio a acceso femoral y la puntuación de disconfort local. El objetivo secundario fue la evaluación del pulso antes y tras la anestesia. Además, un subgrupo de pacientes fue evaluado con ecografía de la arteria radial.

Resultados: Se incluyeron736 pacientes: 379 en el grupo de nitroglicerina y 357 en el grupo C. El número promedio de intentos de punción radial fue similar en ambos (1,70 frente a 1,76; p = 0,42). No hubo diferencias significativas en los 2 grupos con respecto al tiempo total del acceso y del procedimiento (61,1 y 33,3 s frente a 63 y 33,4 s; p = 0,66 y p = 0,64, respectivamente). Tampoco se encontraron diferencias significativas entre los 2 grupos en la tasa de conversión a acceso femoral (7,1 en el grupo de nitroglicerina frente a 8,4% en el grupo C; p = 0,52). Sin embargo, el índice de malestar local y el de pulso tras la anestesia fueron significativamente mejores en el grupo de nitroglicerina (2,34 frente a 2,76, p < 0,001; 2,47 frente a 2,22, p < 0,001). La ecografía mostró un diámetro radial significativamente mayor en el grupo de nitroglicerina tanto en la vista longitudinal (3,11 frente a 2,43 mm; p = 0,002) como en la transversal (2,83 frente a 2,41 mm; p = 0,002). Hubo una menor incidencia de hematoma en el antebrazo en el grupo de nitroglicerina (6,1 frente a 9,8%; p = 0,059). La cefalea fue más frecuente en los pacientes del grupo de nitroglicerina (3,2 frente a 0,6%; p = 0,021).

Conclusiones: El uso sistemático de nitroglicerina subcutánea previo a la punción radial no estuvo asociado a una reducción en el número de punciones ni en el tiempo de acceso, pero el menor malestar local y el aumento del calibre de la arteria radial podrían justificar su uso en la práctica clínica para mejorar la experiencia del acceso transradial tanto en el paciente como en el operador.

Palabras clave: Espasmo radial. Nitroglicerina subcutánea. Acceso radial.

INTRODUCTION

Transradial access to perform coronary and peripheral procedures is becoming more successful compared to transfemoral access thanks to several advantages including more comfort as reported by the patients, early ambulation and discharge, less bleeding, and overall better outcomes.1-5However, the radial artery is more susceptible to spasm, which can stop the advance of the catheter, extend the duration of the procedure, and increase its difficulty.6Also, radial artery spasm has been identified as an independent predictor of radial access failure.7

When radial artery spasm occurs after an introducer sheath has been inserted, the intra-arterial administration of vasodilator drugs has proved to improve the conduit effectively.8Still, the subcutaneous administration of nitroglycerin relieves the spasm causing the reduction significantly and the eventual loss of pulse volume after several ineffective attempts to cannulate the radial artery.9Also, it enhances radial pulse palpation, and eventually makes the puncture of radial artery easier.10,11

Because the first puncture failure is a powerful predictor of radial artery spasm,12we conducted a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial in 4 Argentinian centers to see whether the routine subcutaneous administration of nitroglycerin prior to a cannulation attempt improved transradial access significantly (the NISAR study [subcutaneous nitroglycerin in radial access]).

Specifically, the primary endpoints of the study were to assess the number of radial artery puncture attempts, the time required to place the sheath introducer, the number of times that switching to transfemoral access was required, and the patients’ tolerance to the procedure. The secondary endpoints included the assessment of the radial artery pulse and diameter and local and systemic complications.

METHODS

Patients and procedures

Patients undergoing a coronary angiography with evidence of myocardial ischemia were enrolled in a prospective, multicenter, and randomized clinical trial conducted in 4 Argentinian centers into 2 different groups based on the periradial subcutaneous administration of nitroglycerin. In the nitroglycerin group, 2% xylocaine (1 mL) was used followed by 200 mcg of nitroglycerin (2 mL). In control group, 2% xylocaine (1 mL) was followed by the infusion of a normal saline solution (2 mL) used as placebo. Trained nurses from each center prepared the syringes following a 1:1 randomization scheme and making sure that their content was unknown to both the operators and the patients.

The coronary angiographies and revascularization procedures were performed using 5-Fr or 6-Fr diagnostic and guiding catheters as selected by the operators. In all cases a properly sized sheath introducer was inserted using the Seldinger or modified Seldinger technique. Five thousand units of heparin were consistently administered through a bolus injection with further additions to keep the activated clotting time between 250 and 300 seconds if a percutaneous coronary intervention was performed.

All procedures were performed after patients gave their informed consent by 8 skilled and experienced operators who had performed over 1500 transradial procedures. All operators used the right radial artery as the access of choice; the left radial artery was spared for cases with right radial artery occlusion and patients with left internal mammary artery graft. The Ethics Committe reviewed and approved this study. Patients' informed consent to publish was obtained.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measures were the overall number of puncture attempts, access, and procedural time, switch to transfemoral access, and local perceived discomfort score.

Access time was defined as the time elapsed between the administration of local anesthesia and the insertion of the radial sheath introducer. When the initial radial access could not be completed, the contralateral radial access was never tried and access site changed to the femoral access. The local perceived discomfort score was assessed by the patient after undergoing the procedure and graded according to a radial-related pain score between 0 = no pain and 10 = unbearable pain.