Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Although drug-eluting stents are the main treatment in percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), drug-coated balloons (DCB) represent an appealing alternative as they eliminate the risk of stent thrombosis and avoid leaving any metal structure in the vessel wall. However, limited evidence has been published to date on the vessel wall healing processes, plaque remodeling, plaque composition, and the impact on the coronary microcirculation after percutaneous coronary intervention with DCB (DCB-PCI).

Methods: This is investigator-initiated, single-center, single-arm, open-label, pilot study of 30 patients with native vessel disease undergoing DCB-PCI. Intravascular ultrasound and angiography-derived index of microvascular resistance (IMRangio) will be performed before and immediately after PCI, and at 3 months of follow-up.

Conclusions: The study aims to provide new evidence on the modification of atherosclerotic plaque in patients with de novo lesions undergoing PCI with DCB. This will be assessed by examining the change in the percentage of atheroma volume and late lumen enlargement using intravascular ultrasound and by evaluating changes in the microcirculation using IMRangio.

Registered at Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06080919).

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon. Intravascular ultrasound. Angiography-derived index of microvascular resistance.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Pese a que los stents farmacoactivos son el tratamiento principal en las angioplastias coronarias, los balones farmacoactivos representan una alternativa interesante dado que eliminan el riesgo de trombosis del stent sin dejar ningún tipo de estructura metálica en la pared del vaso. No obstante, la evidencia en cuanto a los procesos de cicatrización de la pared del vaso, el remodelado, los cambios en la composición de la placa ateroesclerótica y el impacto en la microcirculación coronaria tras el intervencionismo coronario percutáneo (ICP) con balón farmacoactivo aún no se ha esclarecido.

Métodos: Estudio piloto abierto, de un solo grupo, iniciado por el investigador, de 30 pacientes con enfermedad de vaso nativo sometidos a ICP con balón farmacoactivo. Se realizará ecografía intravascular y se determinará el índice de resistencia microvascular derivado de la angiografía (angio-IRM) antes, inmediatamente después y a los 3 meses de seguimiento de la angioplastia.

Conclusiones: Se aportará nueva evidencia sobre la modificación de la placa en pacientes con enfermedad de vaso nativo tratados con balón farmacoactivo, evaluando el cambio en el porcentaje del volumen de ateroma y el aumento luminal tardío, así como los cambios en la microcirculación mediante angio-IRM.

Registrado en Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT06080919).

Palabras clave: Balón farmacoactivo. Ecografía intravascular. Índice de resistencia microvascular derivado de la angiografía.

Abbreviations

DCB: drug-coated balloon. EEM: external elastic membrane. IMRangio: angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance. IVUS: intravascular ultrasound. PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease is the leading single cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for more than 7 million deaths annually1 and its prevalence has been increasing in the last 20 years.2 Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) has been crucial in the treatment of coronary artery disease.3,4 The advent of drug-eluting stents (DES) has substantially reduced restenosis rates through the deposition of antiproliferative drugs in the vessel wall. DES have evolved over the years and have become the gold standard in PCI.5 Drug-coated balloons (DCB) represent an alternative in the setting of PCI. DCB consist of a balloon coated with antiproliferative agents encapsulated in a polymer matrix.6 Upon inflation, the balloon brings the antiproliferative drug into contact with the vessel wall. The main goal of DCB is to eliminate the risk of stent thrombosis and achieve lower restenosis rates by not leaving any type of metal structure in the treated segment.6

The safety and efficacy of DCB have been extensively studied in de novo coronary artery disease.6 In small vessel disease, DCB have demonstrated noninferiority to DES in several randomized clinical trials.7 A recent meta-analysis has shown that the use of DCB, compared with that of DES, is associated with a lower risk of vessel thrombosis and a trend toward a lower risk of acute myocardial infarction.8 In large vessel de novo lesions, current data do not support the widespread use of DCB over DES, although DCB appear to be safe and effective.9,10 Nevertheless, there is a need to elucidate the elution on the vessel wall, healing processes, plaque remodeling, plaque composition and the impact on the coronary microcirculation following PCI with DCB.

The present report describes the design and rationale for a study of plaque modification and impact on the microcirculation after PCI with DCB (the PLAMI study).

METHODS

The study will be an investigator-initiated, single-center, single-arm, open-label, pilot study in patients undergoing PCI with DCB for de novo lesions. The study has been approved by the hospital ethics committee on research involving medical products. The study has been registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06080919).

Procedure

Eligible patients will be informed about the study and will be required to provide signed informed consent prior to inclusion. Patients will undergo DCB-PCI under intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) guidance. Angiography-derived coronary physiology will be assessed after the procedure using Angio Plus software (Pulse Medical Imaging Technology, China). The angiography images will be used to obtain the angiography-derived index of microcirculatory resistance (IMRangio) values, before and after DCB-PCI. All procedures will be performed according to current European guidelines5: the target lesion will be predilated with semicompliant balloons or noncompliant balloons, with a diameter equal to the reference vessel diameter and with an appropriate length. Multiple predilations will be accepted. The DCB will be the paclitaxel-coated balloon Pantera Lux (BIOTRONIK AG, Switzerland).

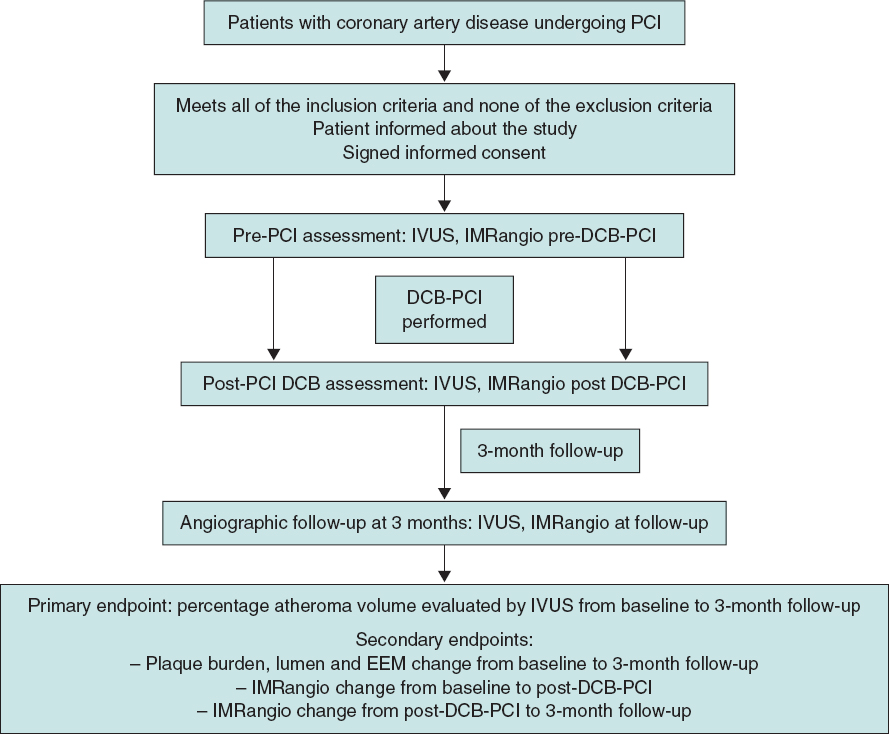

The lesion will then be treated with a DCB with a reference vessel diameter/balloon diameter ratio of 1:1. DCB length will be equal to lesion length + 5 mm. DCB inflation time will be set at 45 to 60 seconds to guarantee correct and complete drug elution. The prespecified reasons for DES implantation after DCB-PCI will be residual stenosis > 30%, dissections > type B and TIMI flow < 3.6 Angiographic follow-up with IVUS and IMRangio evaluation will be performed 3 months after the index procedure. The study timeline is summarized in figure 1.

Figure 1. Timeline of the PLAMI study. DCB, drug-coated balloon; IMRangio, angiography-based index of microcirculatory resistance; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

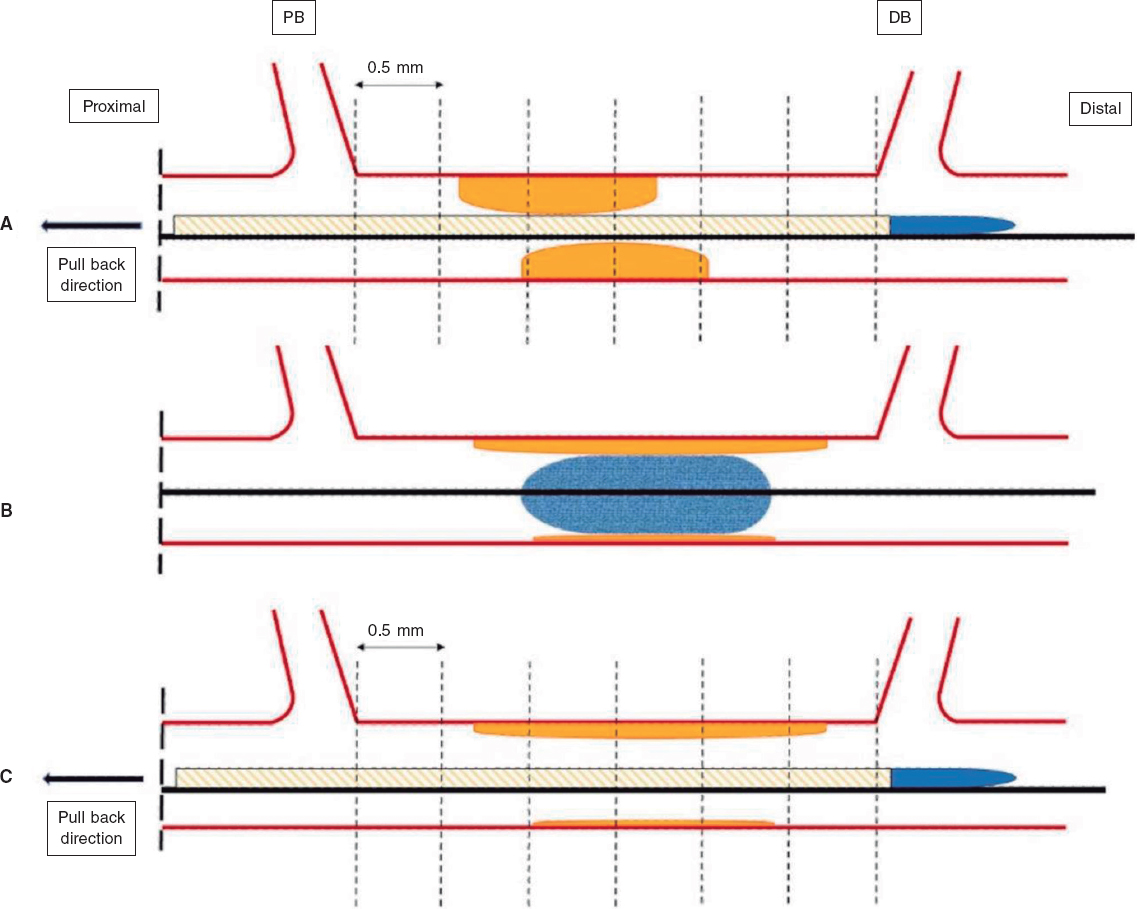

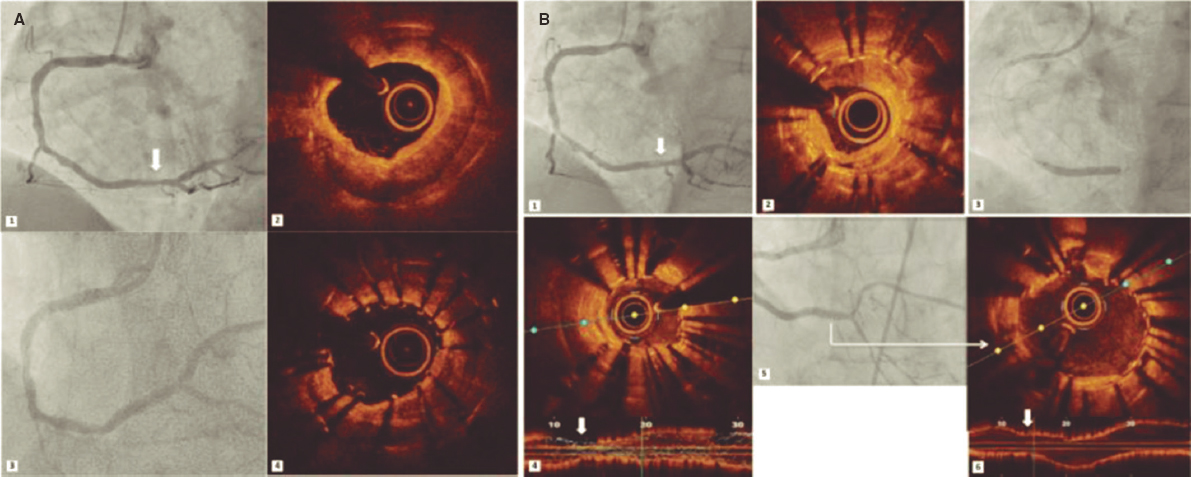

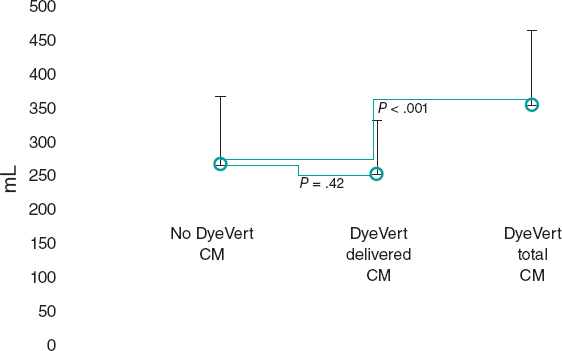

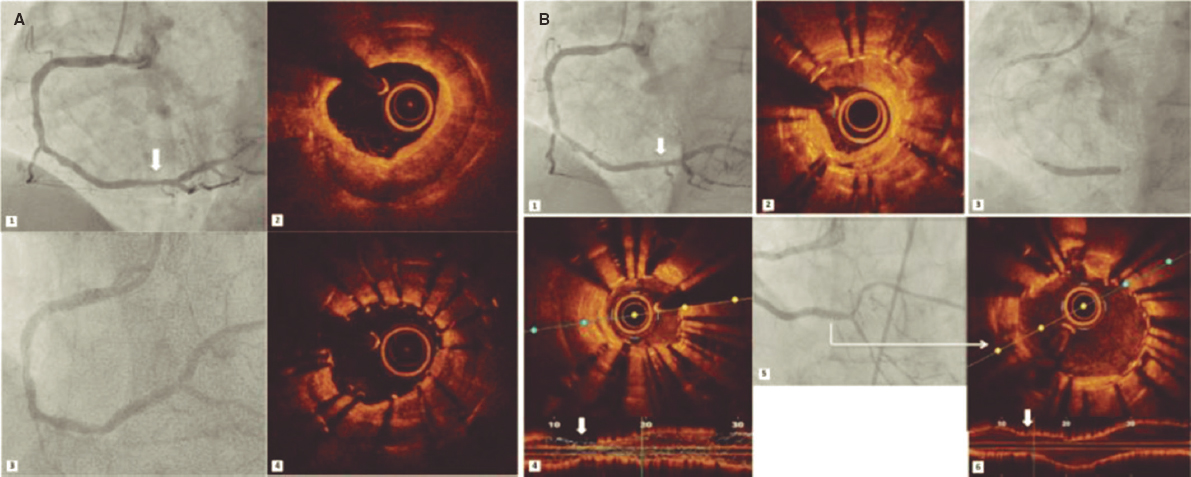

IVUS images will be taken before the DCB-PCI, immediately after, and at 3 months of follow-up using the Opticross HD 60 MHz (Boston Scientific Corp, United States) system. All IVUS studies will be performed after intracoronary administration of 200 μg of nitroglycerin. The IVUS images will be acquired at 30 frames per second with an automatic transducer pull back (at 0.5 mm/second) to the proximal reference vessel lesion. As there will be no stents to take as a reference, the proximal and distal side branches adjacent to the treated lesion will serve as references, matching the coronary angiographic images (figure 2). All IVUS images will be analyzed by an independent core lab.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of IVUS acquisition. The IVUS images will be acquired before (A) and after (C) DCB-PCI (B) at 30 frames per second with an automatic transducer pull back (at 0.5 mm/second) to the proximal reference vessel lesion. The same anatomic slice will be analyzed before, after, and at 3 months of follow-up after the PCI by using reproducible landmarks (side branches). The first frame analyzed will be the distal point of the treated vessel before the exit of the DB (represented by the rightmost dotted line), and the last frame analyzed will be the proximal point of the vessel before the split of the proximal branch. DB, distal branch; DCB-PCI, drug-coated balloon percutaneous coronary intervention; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; PB, proximal branch.

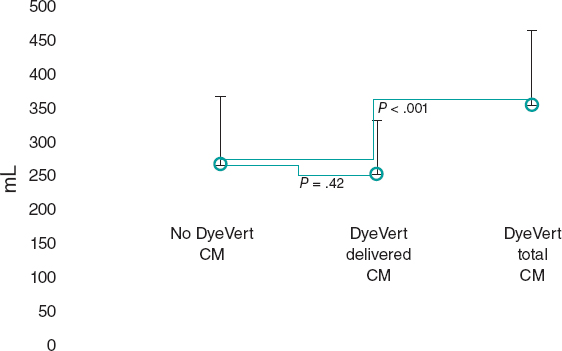

Angiography-derived assessment of coronary physiology will be performed with Angio Plus software (Pulse Medical Imaging Technology, China). For the evaluation of each lesion, at least 2 projections with a difference of > 25° will be selected. The operator will manually mark the points proximal and distal to the lesion, and the system automatically outlines the contours of the detected vessel. If the traced vessel trajectory deviates from the normal lumen, the necessary manual modifications will be performed. The artificial intelligence-assisted software combines the intravascular imaging information with the estimated vessel flow to obtain the IMRangio. All the angiography images will be analyzed by an independent core lab to obtain the IMRangio.

Study population and enrolment criteria

Patients will be screened to ensure they meet the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria prior to study enrolment. Inclusion criteria consist of an indication to undergo PCI for a de novo lesion according to current guidelines (with no restrictions regarding vessel size).5 Inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in table 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Patient with CAD undergoing PCI with DCB with no limitation to vessel size | Age < 18 years |

| Cardiogenic shock | |

| ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction | |

| Use of mechanical circulatory support | |

| Complex coronary lesions* including chronic total occlusions, bifurcation lesions, left main coronary artery disease, severe calcified lesions, graft interventions and in-stent restenosis | |

| Inability to provide informed consent | |

| Unable to understand and follow study-related instructions or unable to comply with study protocol | |

| Currently participating in another trial | |

| Pregnant women | |

|

CAD, coronary artery disease; DCB, drug-coated balloon; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. |

|

Sample size

Because of the exploratory nature of this study, no formal sample size calculation is required. Based on previous pilot studies with similar designs,12 a sample of 30 lesions is planned to evaluate the impact of DCB on coronary healing and the microcirculatory territory.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint is the change in percentage atheroma volume evaluated by IVUS from baseline to 3 months of follow-up. Secondary endpoints will include a) lumen change from baseline to 3 months of follow-up (minimum, maximum, average areas), b) the percentage of progressors and percentage of regressors, c) external elastic membrane (EEM) change from baseline to post DCB-PCI (average), d) EEM change post-DCB-PCI to the 3-month follow-up (average), e) the percentage of remodeling types (neutral, negative, and positive), f) IMRangio change from baseline to post- DCB-PCI, g) IMRangio change from post-DCB-PCI to the 3-month follow-up.

An independent clinical event committee, consisting of cardiologists not participating in the trial, will review and adjudicate all major adverse cardiac events according to the study protocol.

Considering the luminal area as the area delimited by the luminal border, the minimal luminal area is defined as the smallest lumen area within the length of the treated lesion.13,14 The atheroma or plaque burden is defined as the ratio of atheroma area to the vessel EEM and is calculated by dividing the sum of plaque and media cross-sectional area (CSA) by the EEM CSA.13,14 As the atheroma area can be calculated in each frame, the total atheroma volume is obtained by taking the sum of the differences between the EEM CSA area and the luminal CSA for all available images.15 The percent of the volume of the EEM occupied by atheroma is called the percentage atheroma volume.15,16

Serial arterial remodeling types will be classified as usual: neutral if there is no change in EEM, negative if there is a decrease in the EEM and positive if vice versa.

Statistical considerations

Continuous variables will be described as mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables will be described as percentages. The paired t-test will be used to compare continuous variables measured before and after treatment in the same patient, and differences in proportions will be tested with the chi-square or Fisher exact test. A P value less than .05 (typically ≤ .05) will be considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses will be performed using Stata software version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, United States).

DISCUSSION

Although the use of DES remains predominant in the performance of PCI, complications such as stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis led to the development of DCB. DCB have the theoretical benefit of not leaving metallic material in the vascular lumen, thereby reducing the possibility of mechanical complications such as malapposition, stent fracture, and stent thrombosis. This could potentially reduce neointimal proliferation and shorten the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy.6 Current guidelines assign a level IA recommendation to the treatment of in-stent restenosis.5 While the use of DCB in de novo lesions seems promising, it is not yet widespread. In addition, PCI is not without risks, as it involves a certain degree of injury to the artery wall from balloon inflations and stent struts.17,19 The vascular response to endothelial cell and smooth muscle cell injury represents a complex network of biochemical responses that involve the immune system. All these factors regulate the processes of neointimal hyperplasia, vascular remodeling, and normal reendothelialization of the arterial wall.17

The pathophysiology of restenosis and lumen loss after angioplasty is a complex process involving various factors and is not limited to neointimal hyperplasia.19 Acutely, plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) generates an increase in luminal area that is mainly due to an expansion of the EEM, mainly attributed to the elastic properties of the vessel rather than to plaque compression or removal.20 Subsequently, within the first few minutes after PCI, there is an “acute recoil” due to the elastic properties of the arterial wall. In the chronic phase, IVUS data indicate that luminal loss is mainly due to a progressive reduction in EEM rather than an increase in atherosclerotic plaque volume. Unlike the acute phase where loss of area is solely due to elastic properties, “chronic recoil” leading to the loss of area also involves a combination factors such as fibrosis, apoptosis, and changes in the extracellular matrix.19,21 Interestingly, not all patients show negative remodeling with a decrease in EEM; around 25% show a persistent increase in EEM, which is correlated with a reduced restenosis rate. Consequently, restenosis appears to be primarily due to the direction and magnitude of changes in arterial remodeling,19 although neointimal hyperplasia also plays a role .

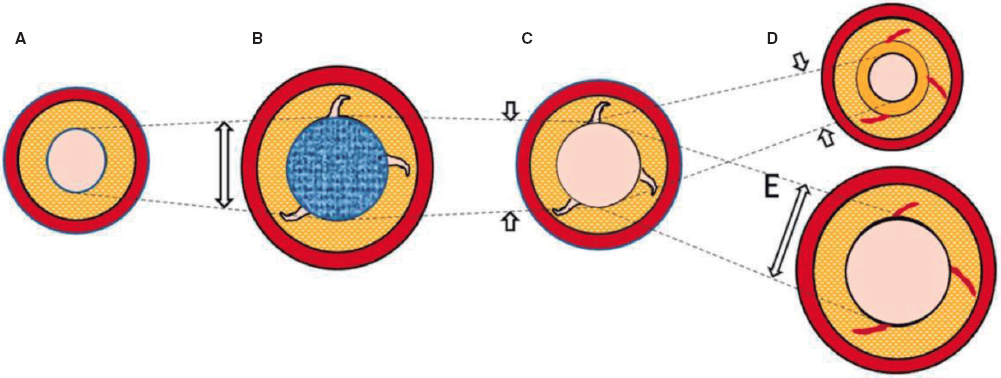

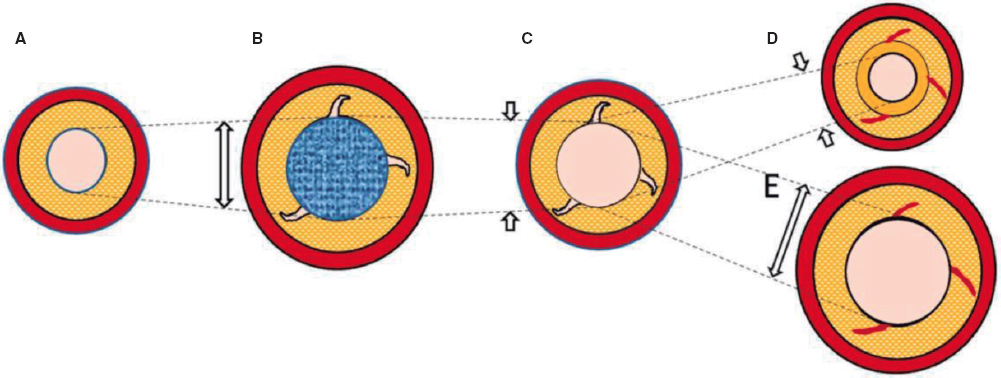

Nevertheless, the existing evidence is based on analysis after the use of traditional balloons. With DCB-PCI, late lumen enlargement has been observed compared with POBA.20 Although this finding has been partly attributed to the inhibition of neointimal proliferation by antiproliferative drugs,22 the role of plaque modification or vessel healing phenomena in influencing this process cannot be excluded. A previous study showed that late lumen enlargement was higher in areas with the highest plaque burden; however, that study was a retrospective assessment and used a quantitative coronary angiography protocol.23 It could be hypothesized that, by inducing controlled damage to the artery wall, together with the antiproliferative effect of DCB, positive vessel remodeling might be achieved, reducing restenosis rates without the need for DES. Therefore, with DCB-PCI, we are able to treat coronary stenosis not only from a mechanical point of view, but can also change the natural history of the disease and restenosis. In this regard, IVUS analysis will be essential to evaluate the reasons behind the gain or loss of luminal area. The dynamic changes produced after PCI are depicted in figure 3.

Figure 3. Central illustration. Schematic representation of timeline of DCB-PCI and lumen variation. A: pre-DCB-PCI de novo lesion. B: DCB-PCI (blue), generating injury to the vessel wall and an increase in lumen and EEM CSA. C: acute recoil. D, chronic recoil with decrease in EEM and neointimal hyperplasia. E. LLE due to maintenance of EEM area and no neointimal hyperplasia. The dotted lines represent the variations of the luminal area throughout the process. The image exemplifies how changes in luminal area, as well as plaque burden, are mainly due to variations in EEM rather than plaque compression. CSA, cross-sectional area; DCB-PCI, drug-coated balloon percutaneous coronary intervention; EEM, external elastic membrane; LLE, late lumen enlargement.

The DCB that will be used in our study, paclitaxel, has been extensively analyzed as a balloon-coating drug due to its lipophilic properties and its ability to elute into the vessel wall.24 Moreover, the available paclitaxel-DCB have shown good results in patients undergoing PCI for native vessel disease.25 In contrast, because of the hydrophobic characteristics of sirolimus, maintaining an adequate percentage in the wall over the mid-term poses technical challenges. However, advances in the formulation of the new generation of sirolimus DCB are anticipated to address this issue by facilitating adequate drug release into the vessel wall.24

As previously mentioned, the coronary microcirculation is closely related to proper coronary functioning and the pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. While it is believed that the performance of PCI, as well as the injury and healing of the coronary artery, may affect the coronary microcirculation, the evidence regarding DCB-PCI is scarce. Moreover, the plaque rupture, intimal dissections and thrombus formation that occur during balloon angioplasty are a potential source of embolism to the microvascular bed.

Since direct visualization of the microcirculation is not feasible in clinical practice,26 its assessment relies on parameters reflecting its functional status, usually coronary flow reserve and the IMR. Coronary flow reserve is defined as the ratio between hyperemic flow in response to nonendothelial vasodilation and resting blood flow. It is crucial to exclude epicardial stenosis before using coronary flow reserve, as it provides an integrated measurement of both epicardial and coronary microcirculation.26 IMR is calculated as the product of distal coronary pressure at maximal hyperemia multiplied by the hyperemic mean transit time.

In our study, we will perform a noninvasive, nonhyperemic assessment of the coronary microcirculation using IMRangio. This approach aims to characterize the baseline status of the microcirculation and assess the microvasculature changes induced by PCI and their variation over a 3-month period.

By monitoring IMRangio before and after treating the stenotic epicardial lesion, we will be able to assess the effects of acute fracture of the atherosclerotic plaque and injury to the arterial wall in the microvascular bed. We also aim to investigate whether these collateral harmful changes provoked during angioplasty remain consistent or vary significantly at 3 months of follow-up. In this same context, the analysis of IVUS during follow-up will allow us to correlate the changes in the arterial wall and atherosclerotic plaque after DCB-PCI with microcirculation physiology. To date, no insights into the anatomical and physiological process of healing of the injured arterial wall after DCB-PCI have been available in the published literature.

CONCLUSIONS

The PLAMI study is a first-in-man pilot study that aims to provide new information on the modification of atherosclerotic plaque assessed by intracoronary imaging in patients with de novo lesions undergoing PCI with DCB.

FUNDING

None reported.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study has been approved by the hospital ethics committee on research involving medical products. Eligible patients will be informed about the study and must provide written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study. Possible gender/sex biases have been considered.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence has been used in the preparation of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A Sorolla Romero, A.Teira Calderón, J. Sanz Sánchez and H.M. Garcia-Garcia contributed to the conception, design, drafting and revision of the article. J.P. Vílchez Tschischke, P. Aguar Carrascosa, F.Ten Morro, L. Andrés Lalaguna, L. Martínez Dolz and J.L. Díez Gil contributed to the critical revision of the intellectual content.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- DCB have proven clinical effectiveness in cases of in-stent restenosis and de novo lesions involving small vessel coronary artery disease.

- Several studies in small vessel coronary artery disease have shown a benefit of DCB in the vessel wall, with late lumen enlargement during follow-up.

- However, there is little evidence of their use in larger vessels.

- In addition, the impact of DCB on the coronary microcirculation has not been evaluated to date.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The PLAMI study aims to characterize vessel healing using IVUS after DCB-PCI in patients with native vessel disease and to correlate these findings with the impact on microcirculation.

REFERENCES

1. Ralapanawa U, Sivakanesan R. Epidemiology and the Magnitude of Coronary Artery Disease and Acute Coronary Syndrome:A Narrative Review. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2021;11:169-177.

2. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;140:e596-e646.

3. Canfield J, Totary-Jain H. 40 Years of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:History and Future Directions. J Pers Med. 2018;8:33.

4. Stefanini GG, Alfonso F, Barbato E, et al. Management of myocardial revascularisation failure:an expert consensus document of the EAPCI. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:e875-e890.

5. Neumann F, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

6. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease:Third Report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402.

7. Tang Y, Qiao S, Su X, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small-Vessel Disease:The RESTORE SVD China Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2381-2392.

8. Sanz Sánchez J, Chiarito M, Cortese B, et al. Drug-Coated balloons vs drug-eluting stents for the treatment of small coronary artery disease:A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:66-75.

9. Yerasi C, Case BC, Forrestal BJ, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon for de Novo Coronary Artery Disease:JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1061-1073.

10. Nishiyama N, Komatsu T, Kuroyanagi T, et al. Clinical value of drug-coated balloon angioplasty for de novo lesions in patients with coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2016;222:113-118.

11. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e21-e129.

12. Joner M, Finn AV, Farb A, et al. Pathology of drug-eluting stents in humans:delayed healing and late thrombotic risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:193-202.

13. Xu J, Lo S. Fundamentals and role of intravascular ultrasound in percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10:1358-1370.

14. Mintz GS, Nissen SE, Anderson WD, et al. American College of Cardiology Clinical Expert Consensus Document on Standards for Acquisition, Measurement and Reporting of Intravascular Ultrasound Studies (IVUS). A report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1478-1492.

15. Gogas BD, Farooq V, Serruys PW, Garcia-Garcia HM. Assessment of coronary atherosclerosis by IVUS and IVUS-based imaging modalities:progression and regression studies, tissue composition and beyond. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;27:225-237.

16. Tobis JM, Perlowski A. Atheroma Volume by Intravascular Ultrasound as a Surrogate for Clinical End Points. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1116-1118.

17. Feinberg MW. Healing the injured vessel wall using microRNA-facilitated gene delivery. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3694-3697.

18. Inoue T, Croce K, Morooka T, Sakuma M, Node K, Simon DI. Vascular Inflammation and Repair:Implications for Reendothelialization, Restenosis, and Stent Thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:1057-1066.

19. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, et al. Arterial Remodeling After Coronary Angioplasty. Circulation. 1996;94:35-43.

20. Her AY, Ann SH, Singh GB, et al. Comparison of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Treatment and Plain Old Balloon Angioplasty for De Novo Coronary Lesions. Yonsei Med J. 2016;57:337-341.

21. Geary RL, Nikkari ST, Wagner WD, Williams JK, Adams MR, Dean RH. Wound healing:A paradigm for lumen narrowing after arterial reconstruction. J Vasc Surg. 1998;27:96-108.

22. Sogabe K, Koide M, Fukui K, et al. Optical coherence tomography analysis of late lumen enlargement after paclitaxel-coated balloon angioplasty for de-novo coronary artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:E35-E42.

23. Kleber FX, Schulz A, Waliszewski M, et al. Local paclitaxel induces late lumen enlargement in coronary arteries after balloon angioplasty. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:217-225.

24. Yerasi C, Case BC, Forrestal BJ, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon for De Novo Coronary Artery Disease:JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1061-1073.

25. Venetsanos D, Omerovic E, Sarno G, et al. Long term outcome after treatment of de novo coronary artery lesions using three different drug coated balloons. Int J Cardiol. 2021;325:30-36.

26. Kunadian V, Chieffo A, Camici PG, et al. An EAPCI Expert Consensus Document on Ischaemia with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries in Collaboration with European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology &Microcirculation Endorsed by Coronary Vasomotor Disorders International Study Group. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3504-3520.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: In patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treatment delay significantly affects outcomes. The effect of admission time in STEMI patients is unknown when percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the preferred reperfusion strategy. This study aimed to determine the association between STEMI outcomes and the timing of admission in a PCI center in south-western Europe.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study analyzed the local electronic data from 1222 consecutive STEMI patients treated with PCI. On-hours were defined as admission from Monday to Friday between 8:00 AM and 6:00 PM on non-national holidays.

Results: A total of 439 patients (36%) were admitted on-hours and 783 patients (64%) were admitted off-hours. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the 2 groups, including the percentage of patients admitted in cardiogenic shock (on-hours 5% vs off-hours 4%; P = .62). The median time from first medical contact to reperfusion did not differ between the 2 groups (on-hours 120 minutes vs off-hours 123 minutes, P = .54) and no association was observed between admission time and in-hospital mortality (on-hours 5% vs off-hours 5%, P = .90) or 1-year mortality (on-hours 10% vs off-hours 10%, P = .97). Survival analysis showed no differences in on-hours PCI vs off-hours PCI (HR, 1.1; 95%CI, 0.74-1.64; P = .64).

Conclusions: In a contemporary emergency network, the timing of STEMI patients’ admission to the PCI center was not associated with reperfusion delays or increased mortality.

Keywords: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Admisison time. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Emergency medical services. Mortality.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: En pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST), el retraso en el tratamiento afecta de manera importante los resultados. El efecto del horario de atención en los pacientes con IAMCEST es dudoso cuando la intervención coronaria percutánea (ICP) es la estrategia de reperfusión preferida. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo determinar la asociación entre los resultados del IAMCEST y el momento de la admisión en un centro con ICP del suroeste de Europa.

Métodos: Estudio de cohorte retrospectivo en el que se analizaron los datos electrónicos locales de 1.222 pacientes consecutivos con IAMCEST tratados con ICP. El horario de atención laboral se definió como la admisión de lunes a viernes de 8 a 18 horas, en días no festivos.

Resultados: Un total de 439 pacientes (36%) ingresaron en horario laboral y 783 (64%) se admitieron fuera del horario. Las características iniciales estaban bien equilibradas entre los grupos, incluyendo el porcentaje de pacientes ingresados en shock cardiogénico (en horario laboral el 5% y fuera del horario laboral el 4%; p = 0,62). La mediana de tiempo desde el primer contacto médico hasta la reperfusión no fue diferente entre los 2 grupos (dentro del horario laboral 120 min y fuera del horario laboral 123 min; p = 0,54). No se observó asociación entre el tiempo de admisión y la mortalidad hospitalaria (dentro del horario laboral el 5% y fuera del horario laboral el 5%; p = 0,90) ni la mortalidad a 1 año (en horario laboral el 10% y fuera del horario el 10%; p = 0,97). El análisis de supervivencia no mostró diferencias entre la admisión dentro del horario laboral y la admisión fuera del horario laboral (HR = 1,1; IC95%, 0,74-1,64; p = 0,64).

Conclusiones: En una red de código infarto contemporáneo, el horario de admisión de pacientes con IAMCEST no se asoció con retrasos en la reperfusión ni con un aumento de la mortalidad.

Palabras clave: Infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST. Horario de ingreso. Intervención coronaria percutánea. Emergencia médica. Mortalidad.

Abbreviations

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide. In Europe, despite the decline in incidence and mortality between 1990 and 2009, these trends have slowed in recent years. Moreover, Mediterranean countries showed lower rate of decline during this period.1

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is a particularly important presentation, associated with high mortality in young individuals.2,3 Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is recommended as the first-line therapy to lower mortality and morbidity in STEMI patients.4-6 The timing of treatment is crucial for positive outcomes, and minimization of the time from symptom onset to revascularization is essencial.7,8 While several factors affect treatment timing, emergency system delays play a crucial role as they can be more easily altered by organizational measures and are often used as a quality measurement in STEMI networks.4,9-13

To ensure timely treatment, primary PCI centers included in STEMI networks are recommended to have a 24/7 service.4 However, the impact of admission time (on- vs off-hours) on treatment delay and patient outcomes remains a matter of debate. Some studies and a large meta-analysis have shown that off-hours admission is associated with worse outcomes, partially explained by longer system delays, less guideline-directed management, and less revascularization.14-16 Conversely, studies in high-volume PCI centers integrated in STEMI networks, demonstrated no differences in outcomes according to admission time.17-20 Overall, these results are heterogeneous and include populations from different health care systems.

In Europe, efforts have been made to improve STEMI care through public awareness, emergency medical system operations, and the implementation of a full national coverage 24/7 PCI network.21

The aim of this study was to determine the association between timing of admission in a PCI center and STEMI patients’ outcomes, within a STEMI network in south-western Europe.

METHODS

Study design and population

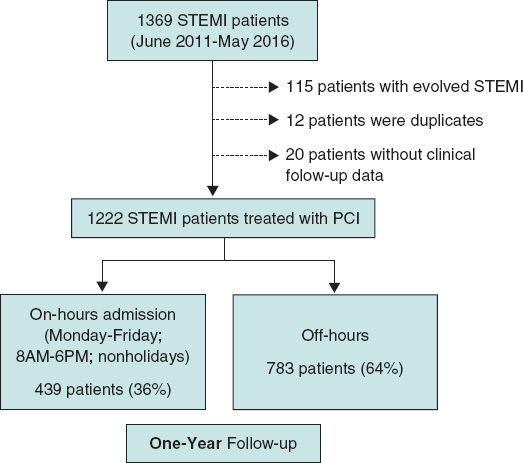

This retrospective observational cohort study identified 1369 consecutive patients treated with primary PCI at the catheterization laboratory of the Hospital de Braga (Portugal) between June 2011 and May 2016, through the local database that systematically includes all patients undergoing invasive coronary procedures. After an initial analysis, 115 patients were found to have evolved STEMI (> 12 hours since symptom onset) and were therefore excluded. To avoid duplication of results, we excluded 12 records of a repeat episode of STEMI in a patient previously identified in the selected time frame. Lastly, clinical follow-up data were not available for 20 patients, resulting in a final sample of 1222 patients (figure 1). These patients were divided into 2 groups according to admission time (on-hours and off-hours admission), and the main outcome measures evaluated were time delays, in-hospital mortality, and 1-year mortality.

Figure 1. Study flow-chart. PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Definitions

STEMI was defined as the presence of symptoms of myocardial ischemia, associated with electrocardiographic criteria for ST-segment elevation.4

Admission time was based on arrival at the catheterization laboratory. On-hours were defined as admission from Monday to Friday between 8:00 AM and 6:00 PM on non-national holidays.

The first medical contact was defined as the first contact with a health service (hospital or primary care clinic). In patients primarily attended by the emergency medical system, the moment when the emergency vehicle carrying a trained physician arrived at the location of the patient was recorded. The reperfusion time was considered as the moment when the angioplasty guidewire crossed the culprit lesion. Time delays from symptom onset to first medical contact (patient-dependent time), from first medical contact to reperfusion (system-dependent time) and from symptom onset to reperfusion (total ischemic time) were characterized.

Patient stratification according to the Killip classification was based on physical examination and the development of heart failure. A Killip class IV classification was assigned to patients in cardiogenic shock.22

STEMI network organization

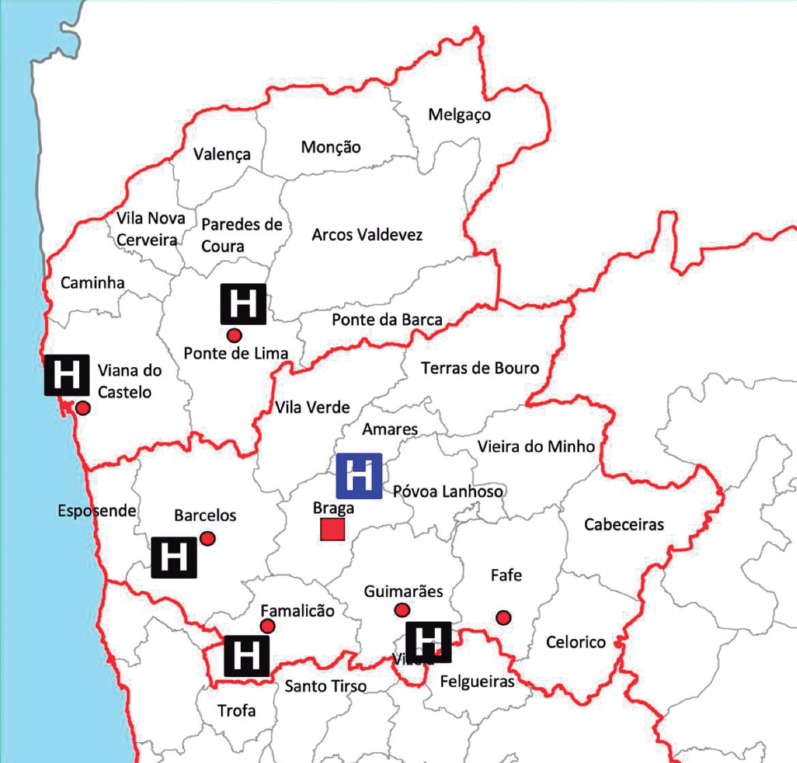

Hospital de Braga has a 24/7 catheterization laboratory service for primary PCI, performed by senior interventional cardiologists (on-call during off-hours). The hospital is the only primary PCI-capable hospital in the Minho region in the north of Portugal and serves approximately 1.1 million people (figure 2). First medical contact can be made by the emergency medical system or in non-PCI-capable hospitals and clinics, which decide whether to transfer the patient to the PCI-center after consulting the on-call clinical cardiologist. First medical contact can also be made in Hospital de Braga, with rapid triage to primary PCI.

Figure 2. Referral network of the catheterization laboratory of Hospital de Braga.

Data collection and statistical analysis

The data for the present study were obtained from the local database of the patient undergoing PCI, the patient’s clinical record, and the electronic health registry of Portugal. Clinical and demographic variables were collected.

The IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 28.0 was used for data treatment. The variables studied to characterize the patients were divided into continuous variables and categorical variables. For the analysis of continuous variables, the distribution was first evaluated. If the variables showed symmetrical normal distribution, the results are presented as mean ± standard deviation, while for variables without normal distribution, the results are reported as median [interquartile range]. To compare continuous variables between the 2 groups of patients, parametric tests were applied for variables with normal distribution and nonparametric tests for the remainder. The Student t test for independent samples was used as the parametric test, after evaluation of the homogeneity of variances using the Levene test. The Mann-Whitney U test was the nonparametric test applied. For the description of categorical variables, absolute (No.) and relative (%) frequencies were calculated. The comparison of proportions between the study groups was made using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test when the percentage of cells in the table with an expected frequency less than 5 was greater than 20%. The 1-year survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method, comparing the groups using the log-rank test. A multivariate analysis with Cox regression was performed, and was adjusted for confounding variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis (age, sex, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, cardiogenic shock, and total ischemia time), to determine if the timing of patient admission was an independent predictor of 1-year mortality. The adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) were analyzed to determine the significance of the predictor. In all analyses, results with probability values of P < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Confidentiality and ethical considerations

Informed consent for the procedure was obtained in all patients. The confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data were ensured during all phases of the study. This study was approved by the local ethics committee and complies with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent for the present analysis was waived by the ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Between June 2011 and May 2016, of 1222 consecutive patients with confirmed STEMI, a total of 439 (36%) were admitted on-hours and 783 (64%) were admitted off-hours. Baseline characteristics were well-balanced between groups, including the percentage of patients admitted in cardiogenic shock (on-hours 5% vs off-hours 4%; P = .62) (table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

| Total (N = 1222) | On-hours (N = 439) | Off-hours (N = 783) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | 61 ± 13 | 62 ± 13 | 61 ± 14 | .40 |

| Female | 269 (22) | 102 (23) | 167 (21) | .44 |

| Smoking (active or previous) | 625 (54) | 218 (51) | 407 (55) | .18 |

| Dyslipidemia | 553 (46) | 201 (46) | 352 (45) | .72 |

| Diabetes | 250 (22) | 104 (25) | 146 (20) | .04 |

| Hypertension | 622 (51) | 224 (52) | 398 (51) | .89 |

| Previous history | ||||

| ACS | 84 (7) | 28 (6) | 56 (7) | .63 |

| PCI | 62 (5) | 43 (4) | 19 (6) | .38 |

| CABG | 11 (1) | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | .50 |

| Presentation | ||||

| Direct admission | 452 (36) | 159 (37) | 293 (37) | .68 |

| Anterior MI | 642 (53) | 229 (52) | 413 (53) | .85 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 51 (4) | 20 (5) | 31 (4) | .62 |

| Angiography | ||||

| Multivessel disease | 583 (48) | 215 (49) | 368 (47) | .51 |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| LVEF | 44 ± 10 | 45 ± 10 | 44 ± 10 | .41 |

|

ACS, acute coronary syndrome; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. Data are expressed as No. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

||||

Comparison of treatment delays

The statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between groups for system-related, patient-related, and total ischemia time (table 2). Similarly, when examining patients directly admitted to the PCI-center, no significant differences were observed in terms of system-related, patient-related, and total ischemia time (table 2).

| Irrespective of place of FMC | Total (N = 1222) | On-hours (N = 439) | Off-hours (N = 783) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-related SO-FMC, min | 87 [45-165] | 82 [45-160] | 89 [48-166] | .30 |

| Emergency system-related FMC-reperfusion, min | 123 [92-172] | 120 [91-169] | 123 [92-173] | .54 |

| Total ischemic time SO-reperfusion | 225 [164-354] | 220 [159-343] | 228 [165-360] | .39 |

| Admitted directly to the PCI-center | Subtotal (N1 = 452) | On-hours (N1 = 159) | Off-hours (N1 = 293) | P |

| Patient-related SO-FMC, min | 77 [40-150] | 75 [45-155] | 78 [40-150] | .96 |

| Emergency system-related FMC-reperfusion, min | 88 [68-115] | 87 [68-115] | 88 [70-115] | .54 |

| Total ischemic time SO-revascularization, min | 177 [125-265] | 175 [127-254] | 177 [124-267] | .92 |

|

FMC, first medical contact; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SO, symptom onset. Values are expressed as median [interquartile range]. |

||||

Association between admission time and outcomes

A 1-year follow-up was completed for all patients included in the analysis. There was no association between on- and off-hours admission time and in-hospital (5% vs 5%; P = .90) or 1-year mortality (10% vs 10%; P = .97). Equally, in patients admitted on- and off-hours directly to the PCI center, in-hospital (4% vs 7%; P = .30) and 1-year mortality (9% vs 13%; P = .27) was similar.

Patients who experienced cardiogenic shock had significantly higher rates of both in-hospital (55% vs 3%; P < .01) and 1-year mortality (71% vs 7%; P < .01) compared with stable patients. However, the time of admission to the hospital did not show a significant impact on the in-hospital (on-hours 50% vs off-hours 58%; P = .57) or 1-year mortality (on-hours 65% vs off-hours 74%; P = .48) for those with cardiogenic shock.

Hospital admissions for heart failure did not differ in patients admitted on- and off-hours (3% vs 3%; P = .60).

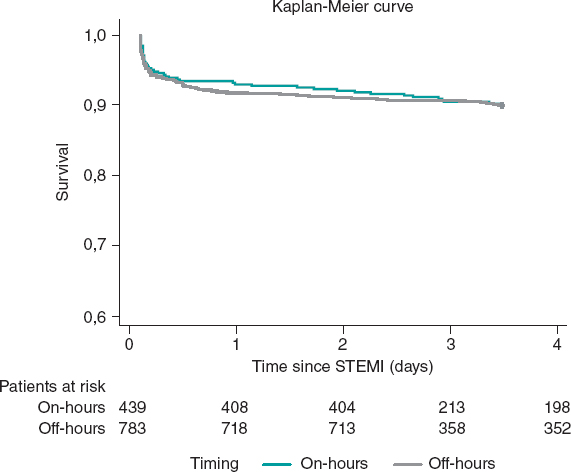

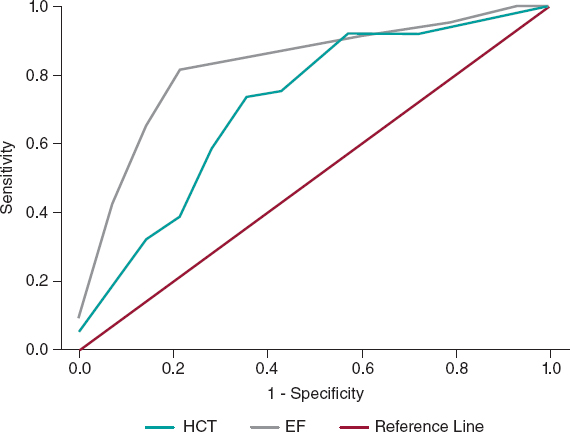

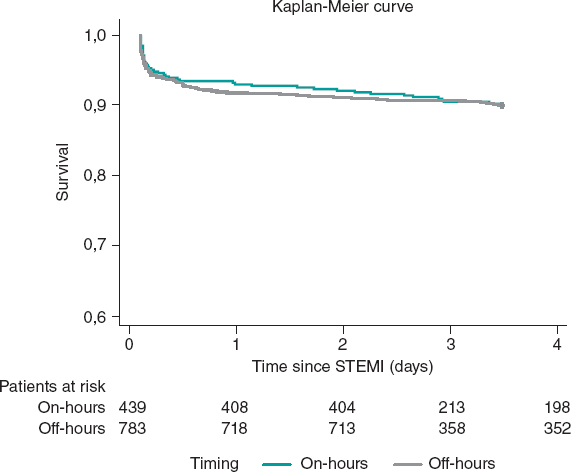

Kaplan-Meier curves showed no differences between timings in survival terms (log-rank P = .95) (figure 3). The timing of admission was not a predictor of 1-year mortality after adjustment (HR, 1.1; 95%CI, 0.74-1.64; P = .64). Independent predictors of mortality at 1-year are depicted in table 3, with cardiogenic shock emerging as the only strong predictor of 1-year mortality.

Figure 3. Kaplan-Meier curves for 1-year survival. STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Table 3. Predictive factors of 1-year mortality

| Adjusted HR* | 95%CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.08 | 1.06-1.10 | < .01 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 12.64 | 7.60-19.47 | < .01 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.49 | 0.98-2.26 | .06 |

| Hypertension | 1.11 | 0.72-1.73 | .63 |

| Sex | 1.29 | 0.78-1.88 | .43 |

| Smoking | 1.06 | 0.65-1.74 | .81 |

| Total ischemic time | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | .06 |

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio. * Multivariate analysis with Cox regression adjusted for confounding variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis (age, cardiogenic shock, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, sex, smoking, and total ischemia time). Admission time was not associated with 1-year mortality in univariate analysis (P = .95). |

|||

DISCUSSION

This study suggests that there is no association between the timing of admission in the PCI center and adverse outcomes, in a structured STEMI network that offers PCI as the standard of care 24/7. Patients admitted off-hours had the same characteristics and were offered the same quality of care as those admitted on-hours, reflected by the similarity in treatment delays. Previous studies, in networks that provided the same quality of care whatever the admission time, reported no differences in outcomes.17-20

On the other hand, studies that report worst outcomes in patients admitted off-hours, mainly reflect differences in care during this period, with increased delay before revascularization, lower delivery of primary PCI, different procedural characteristics, and fewer available staff during off-hours.16,23-25 Additionally, several studies found that patients tended to have worse clinical status on admission during off-hours, which adversely impacted outcomes.16,26 A finding that supports the outmost importance of presentation status is the fact that cardiogenic shock at admission was found to be an independent predictor of 1-year mortality in this study. However, we did not find significant differences in presentation status according to admission time.

This analysis emphasizes that good organization of STEMI networks, with fast-track 24/7 primary PCI, is key to improve patient outcomes and to obviate the adverse impact of off-hours. However, time delays can still be optimized. Public awareness is key to reduce patient-dependent delays, and efforts should be made to improve recognition of symptoms and activation of emergency medical systems. System delays are quality of care indexes, and in this study, they are in the upper margin for benefit of PCI over fibrinolysis (120 minutes).4,27 This group previously analyzed the impact of interhospital transfer in time from first medical contact to reperfusion, and suggested improvements in chest pain work-up in emergency rooms and prompt transfer protocols after STEMI detection.28

Mortality rates in STEMI differ widely among analyses according to the geographical area, time frame analyzed, patient inclusion criteria, and patient management protocols.29,30 Nonetheless, in this analysis, mortality rates (5% in-hospital and 10% 1-year mortality) were in line with those reported in contemporary registries.2,31

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in a STEMI network in south-western Europe ensuring the feasibility and safety of on-call off-hours primary PCI in a contemporary STEMI network. This provides substantial reassurance to the usual organization of cath labs with on-call professionals, essential for workload management and organization of the laboratory workforce.

Study limitations

First, this is a single-center study and may not reflect regional differences in STEMI network organization. Moreover, the results of this study reflect those of a high-volume PC center with a long-standing 24/7 primary PCI program, which may differ from others due to diverse organizational features and available resources. This could be tackled by a future study analyzing national registry data.

Second, the retrospective nature of this study has the limitations inherent to this type of design.

Third, the definition of off-hours admission time is heterogeneous across the literature. In this study, it was defined according to the organizational features of the cath lab, which may not reflect off-hours in other centers/networks.

Additionally, overall mortality in this study may be underestimated, as the group of patients diagnosed in hospitals other than the PCI center and who died before or during transfer were not included in this analysis.

Another limitation of this study is the focus on the management of the patient exclusively until the performance of the primary PCI. Other factors that affect outcomes in these patients, most importantly the delivery of guideline directed medical therapies immediately after revascularization, were not analyzed.

Our findings, based on procedures conducted between 2011 and 2016, may not fully reflect the most current health care trends, given the continuous development of clinical guidelines and treatment approaches. For instance, the reduced use of thrombus aspiration, in line with updated guidelines, highlights the imperative for ongoing research to capture the latest developments in the field.

CONCLUSIONS

In a contemporary emergency network, STEMI patients’ admission time in the PCI-center was not associated with reperfusion delays or increased in-hospital and 1-year mortality. Mortality in efficient STEMI networks is primarily affected by the severity of clinical presentation.

FUNDING

None.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Informed consent for the procedure was obtained in all cases. The confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data were ensured during all phases of the study. This study was approved by the local ethics committee and complied with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent for the present analysis was waived by the ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Possible sex/gender biases were taken into account and avoided.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

The authors did not use artificial intelligence tools during the preparation of this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors contributed to the study design, performed a critical review of the manuscript, gave their final approval, and are fully responsible for all aspects of the study guaranteeing both its integrity and accuracy.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The impact of admission time (on- vs off-hours) on treatment delay and patient outcomes remains a matter of debate. Some studies have shown that off-hours admission is associated with worse outcomes, while others disprove these findings.

- Previous analyses are heterogeneous and include populations from different health care systems.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Real-world clinical evidence that STEMI patients’ admission time to the PCI-center is not associated with reperfusion delays or increased in-hospital and 1-year mortality.

- Mortality in a STEMI network is primarily affected by the severity of clinical presentation.

REFERENCES

1. Vancheri F, Tate AR, Henein M, et al. Time trends in ischaemic heart disease incidence and mortality over three decades (1990–2019) in 20 Western European countries:systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2022;29:396-403.

2. Zeymer U, Ludman P, Danchin N, et al. Reperfusion therapies and in-hospital outcomes for ST-elevation myocardial infarction in Europe:the ACVC-EAPCI EORP STEMI Registry of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4536-4549.

3. Fokkema ML, James SK, Albertsson P, et al. Population Trends in Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:20-Year Results From the SCAAR (Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1222-1230.

4. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177.

5. Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction:A quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13-20.

6. Nielsen PH, Maeng M, Busk M, et al. Primary angioplasty versus fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction:Long-term follow-up in the danish acute myocardial infarction 2 trial. Circulation. 2010;121:1484-1491.

7. Cannon CP, Gibson CM, Lambrew CT, et al. Relationship of Symptom-Onset-to-Balloon Time and Door-to-Balloon Time With Mortality in Patients Undergoing Angioplasty for Acute Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:2941-2947.

8. Koul S, Andell P, Martinsson A, et al. Delay from first medical contact to primary PCI and all-cause mortality:a nationwide study of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000486.

9. Terkelsen CJ, Sørensen JT, Maeng M, et al. System Delay and Mortality Among Patients With STEMI Treated With Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JAMA. 2010;304:763-771.

10. Peterson MC, Syndergaard T, Bowler J, Doxey R. A systematic review of factors predicting door to balloon time in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2012;157:8-23.

11. Pereira H, CaléR, Pinto FJ, et al. Factors influencing patient delay before primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:The Stent for life initiative in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol. 2018;37:409-421.

12. Pereira H, CaléR, Pereira E, et al. Five years of Stent for Life in Portugal. Rev Port Cardiol. 2021;40:81-90.

13. Wein B, Bashkireva A, Au-Yeung A, et al. Systematic investment in the delivery of guideline-coherent therapy reduces mortality and overall costs in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction:Results from the Stent for Life economic model for Romania, Portugal, Basque Country and Kemerovo region. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:902-910.

14. Kostis WJ, Demissie K, Marcella SW, Shao YH, Wilson AC, Moreyra AE. Weekend versus weekday admission and mortality from myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1099-1109.

15. Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship Between Time of Day, Day of Week, Timeliness of Reperfusion, and In-Hospital Mortality for Patients With Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2005;294:803-812.

16. Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction:systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:f7393.

17. de Boer SPM, Oemrawsingh RM, Lenzen MJ, et al. Primary PCI during off-hours is not related to increased mortality. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2012;1:33-39.

18. Rathod KS, Jones DA, Gallagher SM, et al. Out-of-hours primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction is not associated with excess mortality:a study of 3347 patients treated in an integrated cardiac network. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003063.

19. Lattuca B, Kerneis M, Saib A, et al. On- Versus Off-Hours Presentation and Mortality of ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Treated With Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Cardiovascular Interventions. 2019;12:2260-2268.

20. Casella G, Ottani F, Ortolani P, et al. Off-hour primary percutaneous coronary angioplasty does not affect outcome of patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated within a regional network for reperfusion:The REAL (Registro Regionale Angioplastiche dell'Emilia-Romagna) registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:270-278.

21. Wein B, Bashkireva A, Au-Yeung A, et al. Systematic investment in the delivery of guideline-coherent therapy reduces mortality and overall costs in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction:Results from the Stent for Life economic model for Romania, Portugal, Basque Country and Kemerovo region. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:902-910.

22. Killip T, Kimball JT. Treatment of myocardial infarction in a coronary care unit:A Two year experience with 250 patients. Am J Cardiol. 1967;20:457-464.

23. Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship Between Time of Day, Day of Week, Timeliness of Reperfusion, and In-Hospital Mortality for Patients With Acute ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. JAMA. 2005;294:803-812.

24. Barnett Pathak E, Strom JA. Disparities in Use of Same-Day Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction in Florida, 2001–2005. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:802-808.

25. Cavallazzi R, Marik PE, Hirani A, Pachinburavan M, Vasu TS, Leiby BE. Association Between Time of Admission to the ICU and Mortality:A Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138:68-75.

26. Glaser R, Naidu SS, Selzer F, et al. Factors Associated With Poorer Prognosis for Patients Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention During Off-Hours. Biology or Systems Failure?JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:681-688.

27. Pinto DS, Frederick PD, Chakrabarti AK, et al. Benefit of transferring ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction patients for percutaneous coronary intervention compared with administration of onsite fibrinolytic declines as delays increase. Circulation. 2011;124:2512-2521.

28. Ferreira AS, Costa J, Braga CG, Marques J. Impacto na mortalidade da admissão direta versus transferência inter?hospitalar nos doentes com enfarte agudo do miocárdio com elevação do segmento ST submetidos a intervenção coronária percutânea primária. Rev Port Cardiol. 2019;38:621-631.

29. Williams C, Fordyce CB, Cairns JA, et al. Temporal Trends in Reperfusion Delivery and Clinical Outcomes Following Implementation of a Regional STEMI Protocol:A 12-Year Perspective. CJC Open. 2023;5:181-190.

30. Landon BE, Hatfield LA, Bakx P, et al. Differences in Treatment Patterns and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction for Low- and High-Income Patients in 6 Countries. JAMA. 2023;329:1088-1097.

31. Szummer K, Wallentin L, Lindhagen L, et al. Improved outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction during the last 20?years are related to implementation of evidence-based treatments:experiences from the SWEDEHEART registry 1995–2014. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:3056-3065.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: A systematic approach to patients with angina with no obstructed coronary arteries (ANOCA) or ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries (INOCA) patients is not routinely implemented.

Methods: All consecutive patients diagnosed with ANOCA/INOCA were referred to a designated outpatient clinic for a screening visit to assess their eligibility for a NOCA program. If eligible, patients underwent scheduled coronary angiograms with coronary function testing and intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing. Medical therapy was optimized accordingly. All patients were then followed up at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. Baseline and 3-month follow-up assessments included the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) and EuroQol-5D questionnaire.

Results: Of 77 patients screened, 23 (29.9%) were excluded and 54 (70.1%) were included (29 [53.7%] with INOCA and 25 [46.3%] with ANOCA). Microvascular angina was diagnosed in 19 (35.2%) patients, vasospastic angina in 12 (22.2%), both microvascular angina and vasospastic angina in 18 (33.3%), and noncoronary chest pain in 5 (9.3%). There was a notable increase in the use of beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers and nitrates. Complications occurred in 3 (5.5%) patients. Compared with baseline, there was no difference in the mean EQ-5D score at the 3-month follow-up, but there was a significant improvement in the SAQ score related to physical limitations, angina stability, and disease perception, with no differences in angina frequency or treatment satisfaction. No events were recorded at the 1-year follow-up.

Conclusions: A specific diagnostic and therapeutic protocol can be easily and safely implemented in routine clinical practice, leading to improvement in patients’ quality of life.

Keywords: INOCA. ANOCA. Diagnosis. Therapy. Protocol.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El abordaje sistemático en pacientes con angina con arterias coronarias no obstruidas (ANOCA) o con isquemia con arterias coronarias no obstruidas (INOCA) no está bien protocolizado.

Métodos: Todos los pacientes con diagnóstico de INOCA o ANOCA se trasladaron a una clínica ambulatoria específica para evaluar su elegibilidad para el programa NOCA. Si eran elegibles, se sometían a una angiografía coronaria programada con pruebas de función coronaria y provocación intracoronaria con acetilcolina. La terapia médica se optimizó en consecuencia. Todos los pacientes tuvieron un seguimiento a 1, 3, 6 y 12 meses. Al inicio y a los 3 meses se aplicaron los cuestionarios SAQ y EuroQol-5D.

Resultados: De 77 pacientes se excluyeron 23 (29,9%) y se incluyeron 54 (70,1%) (29 [53,7%] con INOCA y 25 [46,3%] con ANOCA). Se diagnosticó angina microvascular a 19 (35,2 %) pacientes, angina vasoespástica a 12 (22,2 %), angina microvascular y angina vasoespástica a 18 (33,3 %), y dolor torácico no coronario a 5 (9,3 %). Hubo un aumento significativo en el uso de bloqueadores beta, bloqueadores del calcio y nitratos. Se presentaron complicaciones en 3 (5,5%) pacientes. No hubo diferencias en la puntuación media del EQ-5D a los 3 meses y se observó una mejora significativa en la puntuación SAQ respecto a la limitación física, la estabilidad de la angina y la percepción de enfermedad, sin diferencias en la frecuencia de angina y la satisfacción con el tratamiento. No se registraron eventos al año.

Conclusiones: Un protocolo diagnóstico y terapéutico específico podría implementarse de manera fácil y segura en la práctica clínica diaria, y con ello mejoraría la calidad de vida de los pacientes.

Palabras clave: INOCA. ANOCA. Diagnóstico. Terapia. Protocolo.

Abbreviations

ANOCA: angina with no obstructed coronary arteries. INOCA: ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries.

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of disability and mortality worldwide and is commonly characterized by the presence of obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) (defined as any coronary artery stenosis ≥ 50% in diameter).1 However, up to 60% to 70% of patients with angina and/or documented myocardial ischemia do not have angiographic evidence of CAD.2 This condition is defined as angina with no obstructed coronary arteries (ANOCA) or ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries (INOCA) when associated with evidence of myocardial ischemia.3 Of note, despite the absence of CAD, these patients are at an increased risk of future cardiovascular events such as acute coronary syndrome, heart failure hospitalization, stroke, and repeat cardiovascular procedures compared with healthy individuals.4,5 Therefore, appropriate management in terms of diagnosis and treatment is of the utmost importance to improve patients’ prognosis and outcomes.6 The Coronary Microvascular Angina (CorMicA) trial demonstrated that a strategy of adjunctive invasive testing for disorders of coronary function together with stratified medical therapy can improve outcomes (ie, reduction in angina severity and enhanced quality of life).7,8 However, there are still concerns about the implementation in real-world practice of a systematic diagnostic and therapeutic approach in INOCA and ANOCA patients, potentially impacting outcomes and quality of life.

We report our single-center experience of the implementation in clinical practice of a specific diagnostic and therapeutic protocol (no obstructed coronary arteries [NOCA] program) in INOCA and ANOCA patients.

METHODS

Eligibility criteria for the NOCA program

All consecutive patients diagnosed either at our hospital or at our referral centers with angina or ischemia with nonobstructive CAD on coronary angiography were referred to a specific outpatient clinic (the NOCA clinic at Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain) for a screening visit. Nonobstructive CAD was defined as angiographic evidence of normal coronary arteries or diffuse atherosclerosis with stenosis < 50% and/or fractional flow reserve (FFR) > 0.80 if there was stenosis between 50% and 70%. During the screening visit, a team of expert cardiologists confirmed patients’ eligibility for the NOCA program based on the following criteria: a) diagnosis of ANOCA, defined as stable, chronic typical angina symptoms (eg, chest pain precipitated by physical exertion or emotional stress and relieved by rest or nitroglycerine); b) diagnosis of INOCA, defined as the demonstration of myocardial ischemia identified by a noninvasive test with pharmacologic or exercise stress tests such as cardiac single photon emission computed tomography, cardiac magnetic resonance, stress electrocardiography, or echocardiography.3 The exclusion criteria were: a) atypical angina symptoms, and b) clearly identifiable noncoronary causes of chest pain (figure 1). The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the study was approved by our institutional review committee. All patients provided written informed consent to be included in this program and study. The clinical ethics committee gave their approval for a retrospective analysis of the collected data.

Figure 1. Central illustration. Flowchart for the inclusion of patients in the NOCA program. Cath lab, catheterization laboratory; INOCA: ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries; NOCA, no obstructed coronary arteries; NOCAD, nonobstructive coronary artery disease.

NOCA program: diagnostic approach

After patient inclusion in the NOCA program, specialized counseling was provided by expert cardiologists and nurses. All patients were thoroughly informed about their disease, the importance of reaching a specific diagnosis, and the importance implementing tailored therapy. During the counseling sessions, the predicted benefits and low associated risks of an invasive procedure to specifically study coronary microcirculation and vasospasm were explained in detail. All patients provided written informed consent to undergo coronary angiography and intracoronary provocation testing with acetylcholine (ACh).

Subsequently, all patients underwent a scheduled coronary angiogram with a comprehensive diagnostic work-up consisting of the following: a) coronary function testing to assess coronary flow reserve (CFR) and the index of microvascular resistance (IMR); b) intracoronary ACh provocation testing to assess the presence of coronary vasomotion disorders (eg, epicardial or microvascular spasm).

Coronary function testing was performed using a pressure-temperature sensor guidewire (PressureWire X Guidewire and Coroventis CoroFlow Cardiovascular System, Abbott Vascular, United States) placed in the left anterior descending artery (LAD) as the prespecified target vessel, reflecting its subtended myocardial mass and coronary dominance. Steady-state hyperemia was induced using intravenous adenosine (140 µg/kg/min). If there was severe tortuosity of the LAD or evidence of myocardial ischemia in a region other than the territory of the LAD, the wire was placed in the right coronary artery or the left circumflex, as per the operator’s decision. CFR was calculated using thermodilution, defined as resting mean transit time divided by hyperemic mean transit time (abnormal CFR was defined as ≤ 2.5). IMR was calculated as the product of distal coronary pressure at maximal hyperemia multiplied by the hyperemic mean transit time (normal value < 25).6,9

Intracoronary ACh provocation testing was performed with a standardized protocol involving serial ACh infusions for 20 seconds at increasing concentrations (2-20-100 µg in the left coronary artery with an interval of 2-3 minutes between each injection) with concomitant assessment of the patient’s symptoms, electrocardiogram documentation, and angiographic scans. Patients taking vasoactive drugs (eg, calcium channel blockers and nitrates) underwent a wash-out period of at least 48 hours before the provocative test.10,11,12 Epicardial coronary spasm was defined as the reproduction of chest pain and ischemic electrocardiogram changes in association with a reduction in coronary diameter ≥ 90% from baseline in any epicardial coronary artery segment.13 Microvascular spasm was diagnosed when typical ischemic ST-segment changes (deviation ≥ 1 mm) and angina developed in the absence of epicardial coronary constriction (< 90% diameter reduction).14

Subsequently, patients were stratified into 4 endotypes: a) microvascular angina (MVA) (evidence of coronary microvascular dysfunction [CMD] defined as any abnormal CFR [< 2.5], IMR [≥ 25], or microvascular spasm); b) vasospastic angina (VSA) (CFR ≥ 2.5, IMR < 25 and epicardial spasm); c) both MVA and VSA (evidence of CMD and epicardial spasm); and d) noncoronary chest pain (CFR ≥ 2.5 and IMR < 25, with neither microvascular nor epicardial spasm).6

Any complications occurring during the invasive diagnostic work-up were documented, including bradyarrhythmias, atrial fibrillation, ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation, coronary perforations, death from any cause, and any other complications.

NOCA program: pharmacological and psychological therapeutic approach

Once the endotype was identified, medical treatment for each patient was optimized accordingly (table 1). In patients with MVA, treatment with beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) was started or up-titrated. Ranolazine was added if angina symptoms were not fully controlled by beta-blockers and CCBs. In patients with VSA, treatment with nondihydropyridine CCBs and long-acting nitrates was started or up-titrated. In patients with both MVA and VSA, treatment with nondihydropyridine CCBs or beta-blockers was started or up-titrated. In patients with noncoronary chest pain, vasoactive drugs were discontinued unless clinically indicated for other reasons. Additionally, treatment with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers and statins was started or up-titrated in all patients. If a patient showed intolerance or had contraindications to a specific medication (eg, asthma for beta-blockers, perimalleolar edema for CCBs, severe bradycardia for both beta-blockers and CCBs), the treatment was tailored and modified accordingly.

Because stress is an important trigger factor for angina symptoms, all patients were also referred to a team of expert psychologists for psychological support.15

NOCA program: clinical outcome and quality of life evaluation

All patients were followed up at 1, 3, 6, and 12-months for treatment titration and assessment of clinical outcomes. At the time of coronary angiography (ie, baseline) and at the 3-month follow-up, all patients were administered the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) and quality of life questionnaire (EuroQol-5D [EQ-5D]). The SAQ is a validated 19-item self-administered questionnaire that measures 5 dimensions of CAD: physical limitation, angina stability, angina frequency, treatment satisfaction, and disease perception.16 The EQ-5D is a standardized, nondisease-specific questionnaire used to describe and evaluate patients’ health status and was intended to complement other quality-of life measures.17 Figure 2 provides a visual representation of all the steps involved for patients included in the NOCA program.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the NOCA program. EQ-5D, EuroQol-5D; NOCA, no obstructed coronary arteries; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire. * See text for more details.

Statistical analysis

Data distribution was assessed according to the Kolgormonov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were compared using the unpaired Student t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. The data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as median and interquartile range [IQR]. Categorical data are expressed as numbers and percentages and were evaluated using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. A 2-sided P value < .05 was considered significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (SPSS, United States).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics of the study population

From January 2021 to December 2021, a total of 77 patients were screened at the NOCA clinic for inclusion in the NOCA program. Following the screening visit, 23 (29.9%) patients were excluded from the NOCA program: 12 due to atypical angina symptoms and 11 due to a clearly identifiable noncoronary cause. Consequently, 54 patients were included in the NOCA program (mean age 64.4 ± 9.4 years, 39 [63.9%] women). A total of 29 (53.7%) patients had INOCA and 25 (46.3%) had ANOCA. All clinical and angiographic characteristics of the study population are shown in table 1.

Table 1. Medical therapy according to the specific endotype of ANOCA/INOCA

| Pathogenic mechanism of MINOCA | Therapeutic implications |

|---|---|

| MVA | Beta-blockers (Nebivolol 2.5–10 mg daily) |

| CCBs (amlodipine 10 mg daily, or verapamil 240 mg daily, or diltiazem 90 mg twice daily) | |

| Ranolazine (375-750 mg twice daily) | |

| VSA | Nondihydropyridine CCBs (verapamil 240 mg, or ciltiazem 90 mg twice daily) |

| Long-acting nitrates (isosorbide mononitrate 30 mg) | |

| MVA and VSA | CCBs (verapamil or diltiazem) or beta-blockers |

| Noncoronary chest pain | Beta-blockers or dihydropyridine CCBs if clinically indicated (eg, hypertension) |

| ACEi or ARB if clinically indicated | |

| Statins if clinically indicated | |

|

ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ANOCA, angina with no obstructed coronary arteries; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; CCBs, calcium channel blockers; INOCA, ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries; MINOCA, myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease; MVA, microvascular angina; VSA, vasospastic angina. |

|

NOCA program: diagnosis of the specific endotype and complications

The results of the invasive functional assessment are presented in table 2. The mean IMR and CFR values were 21.2 ± 10.6 and 2.3 ± 1.4, respectively. MVA was diagnosed in 19 (35.2%) patients, VSA in 12 (22.2%), and both MVA and VSA in 18 (33.3%). Finally, 5 (9.3%) patients were diagnosed with noncoronary chest pain.

Table 2. Clinical and angiographic characteristics of patients included in the NOCA program

| Characteristics | Study population (n = 54) |

|---|---|

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age | 64.4 ± 9.4 |

| Female sex | 39 (72.2) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| ANOCA | 25 (46.3) |

| INOCA | 29 (53.7) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 12 (22.2) |

| Hypertension | 35 (64.8) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 28 (51.9) |

| Former smokers | 3 (5.7) |

| Current smoker | 14 (25.9) |

| Familiar history of CV disease | 5 (9.3) |

| Previous CV history | |

| Prior MI | 7 (13.0) |

| Prior PCI | 8 (14.8) |

| Prior CABG | 0 (0.0) |

| COPD | 1 (1.9) |

| CKD (eGFR < 60 mL/min/m2) | 4 (7.4) |

| Depression | 15 (27.8) |

| Anxiety | 19 (35.2) |

| Invasive functional evaluation | |

| Vessel explored | |

| LDA | 48 (88.9) |

| LCx | 3 (5.6) |

| RCA | 3 (5.6) |

| IMR | 21.2 ± 10.6 |

| Increased IMR (≥ 25) | 18 (33.3) |

| CFR | 2.3 ± 1.4 |

| Reduced CFR (< 2.5) | 33 (61.1) |

| Increased IMR (≥ 25) and reduced CFR (< 2.5) | 13 (24.1) |

| Diagnosis (endotype) | |

| MVA | 19 (35.2) |

| VSA | 12 (22.2) |

| MVA and VSA | 18 (33.3) |

| Noncoronary chest pain | 5 (9.3) |

|

ANOCA, angina with no obstructed coronary arteries; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; CFR, coronary flow reserve; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CV, cardiovascular; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; IMR, index of microcirculatory resistance; INOCA, ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries; MI, myocardial infarction; MVA, microvascular angina; LAD, left anterior descending; LCx, left circumflex; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; VSA, vasospastic angina. Values are expressed as No. (%), mean ± standard deviation or median [interquartile range]. |

|

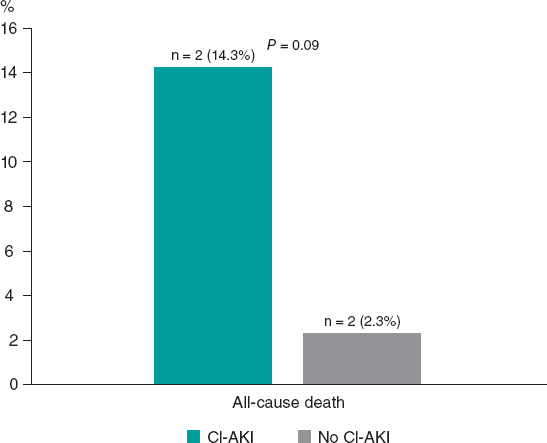

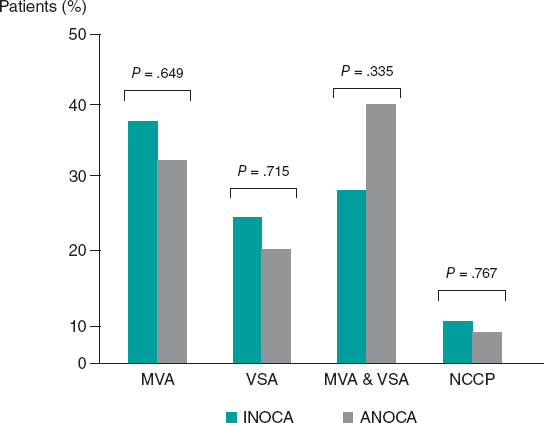

Among INOCA patients, MVA was diagnosed in 11 (37.9%) patients, VSA in 7 (24.1%), both MVA and VSA in 8 (27.6%), and noncoronary chest pain in 3 (10.3%). Among ANOCA patients, MVA was diagnosed in 8 (32.0%) patients, VSA in 5 (20.0%), both MVA and VSA in 10 (40.0%), and noncoronary chest pain in 2 (8.0%). There were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence of any endotype between INOCA and ANOCA patients (all P > .05, figure 3).

Figure 3. Prevalence of the different endotypes among INOCA and ANOCA patients. ANOCA, angina with no obstructed coronary arteries; INOCA, ischemia with no obstructed coronary arteries; MVA, microvascular angina; NCCP, noncoronary chest pain; VSA, vasospastic angina.

Complications occurred in 3 (5.5%) patients during intracoronary ACh provocation testing: 2 (3.7%) patients had transient bradyarrhythmias and 1 (1.8%) patient had paroxysmal atrial fibrillation that spontaneously reverted to sinus rhythm.

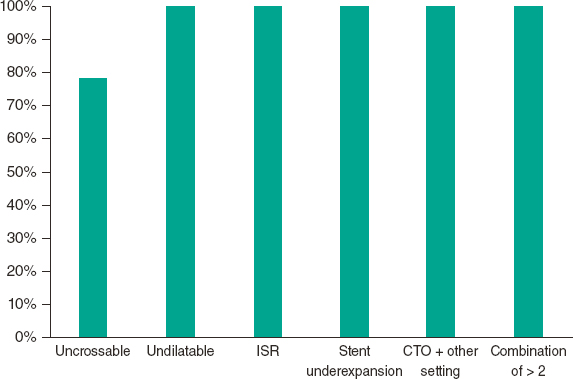

NOCA program: treatment optimization according to the specific endotype

Inclusion in the NOCA program led to statistically significant changes in medications after diagnosis of the specific endotype. There was a significant increase in the use of beta-blockers (33.3% before vs 57.4% after, P = .008), nondihydropyridine CCBs (9.3% before vs 37.0% after, P < .001), and long-acting nitrates (46.3% before vs 63.0% after, P = .012). There were no statistically significant differences in any other medications before and after the invasive assessment (all P > .05, figure 4). All changes in medications according to the specific endotype of ANOCA/INOCA are shown in figure 5.

Figure 4. Differences in medical treatment before and after patient inclusion in the NOCA program. ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; DP-CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; LA, long-acting; ND-CCBs, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers.

Figure 5. Changes in medications according to the specific endotype of ANOCA/INOCA. A: patients with MVA. B: patients with VSA. C: Patients with MVA and VSA. D: patients with noncoronary chest pain. DP-CCBs, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; LA, long-acting; MVA, microvascular angina; ND-CCBs, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; VSA, vasospastic angina.