Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Former studies have associated the severity of calcified plaques (CP) on the invasive coronary angiography (ICA) with a limited number of optical coherence tomography (OCT) measurements. The objective of this study was to describe the correlation between an extended and comprehensive set of OCT measurements and the severity of calcifications as seen on the ICA.

Methods: We retrospectively studied 75 patients (75 lesions) who underwent ICA and, concurrently, OCT imaging at a single institution. The OCT was performed before the percutaneous coronary intervention and after the administration of intracoronary nitroglycerine. The coronary artery calcium was scored using a three-tier classification system on the ICA. Maximum calcium angle, area, maximum thickness, length of calcium, and calcium depth were assessed on the OCT.

Results: The ICA detected fewer CP lesions compared to the OCT (N = 69; 92%), all cases of positive ICA were detected by the OCT (N = 30; 100%). The OCT did not find any positive lesions in negative angiographic lesions (N = 6; 100%). The sensitivity of the ICA was 43.5% (95%CI, 0.32-0.56) and its specificity, 100% (95%CI, 0.52-1.0). In most cases, as calcium angle, thickness, and area increased on the OCT so did the calcium severity of the lesions on the angiography.

Conclusions: Compared to the OCT, the ICA has a low sensitivity and a high specificity in the detection of calcified plaques. As calcium angle, thickness, area, and length increased on the OCT so did the number of angio-defined lesions of severe CP.

Keywords: Tomography. Optical coherence tomography. Invasive coronary angiography. Percutaneous coronary intervention. Calcification.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Estudios previos han asociado la gravedad de la calcificación de las lesiones coronarias evaluadas con angiografía coronaria invasiva (ACI) con un número limitado de medidas obtenidas con tomografía de coherencia óptica (OCT). El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la correlación de una amplia y exhaustiva serie de medidas de OCT con la gravedad de la calcificación estimada por ACI.

Métodos: Se estudiaron retrospectivamente 75 pacientes (75 lesiones) de un único centro a quienes se realizaron simultáneamente ACI y OCT. La OCT se llevó a cabo tras la administración de nitroglicerina intracoronaria antes del intervencionismo coronario. En la ACI, la calcificación coronaria se valoró utilizando un sistema de clasificación en tres grados. Con OCT se evaluaron el máximo ángulo, el área, el grosor máximo, la longitud y la profundidad del calcio.

Resultados: La ACI detectó menos lesiones calcificadas que la OCT (n = 69; 92%) y todos los casos detectados por ACI fueron identificados con OCT (n = 30; 100%). La OCT no encontró calcio en ninguna de las lesiones sin calcio en la ACI (n = 6; 100%). La sensibilidad de la ACI fue del 43,5%, (IC95%, 0,32-0,56) y la especificidad del 100% (IC95%, 0,52-1,0). A medida que se incrementaron el ángulo, el grosor y el área del calcio por OCT también aumentó la gravedad del calcio determinada por ACI en la mayoría de los casos.

Conclusiones: La ACI tiene una baja sensibilidad, pero una alta especificidad, para la detección de lesiones calcificadas en comparación con la OCT. Al incrementarse el ángulo, el grosor, el área y la longitud del calcio en la OCT aumenta el número de lesiones con calcificación grave en la ACI.

Palabras clave: Tomografia. Coherencia optica. Angiografia coronaria invasiva. Intervencion coronaria percutanea. Calcificacion.

Abbreviations

CP: calcified plaque. OCT: optical coherence tomography. ICA: invasive coronary angiography.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease is very prevalent in the United States and is associated with high cardiovascular mortality rates.1 The management of advanced coronary artery disease (eg, calcified lesions) is often the percutaneous coronary intervention, but the use of the PCI alone in calcified plaques (CP) is associated with poor procedural outcomes.2-5 This is mainly due to the lack of information on the spread of calcification and its appropriate management before stenting. Therefore, intravascular imaging modalities are necessary for the characterization of calcium inside the vessel and better guide the interventional cardiologist.6-9

The optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution cross-sectional imaging modality with an unparalleled axial resolution of around 4-20 microns.10 The OCT allows more accurate measurements of the CP over other invasive imaging modalities like the invasive coronary angiography (ICA) and the intravascular ultrasound (IVUS).11

Prior studies have associated the severity of the CP on the ICA with a limited number of measurements on the OCT.6,12-14 Our study aimed to further describe the correlation between an extended and comprehensive set of OCT measurements and the severity of calcification as seen on the ICA.

METHODS

Study population

We retrospectively studied 75 patients who underwent ICA and concurrently had OCT imaging acquired at the St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, NY, United States, from November 2018 through April 2019. A total of 109 lesions were identified in these patients on the ICA. An OCT plus an ICA analysis were performed on 75 of these lesions deemed primary lesions while 34 lesions were excluded from the analysis (no OCT available). All primary lesions were lesions seen on the OCT images, not on the target lesion that received the stent during the procedure. No severely calcified plaques that could not be catheterized were excluded. All the lesions excluded were secondary or tertiary lesions that were deemed non-primary based on the lower calcification burden. No lesions required preparation or ablation before the OCT imaging. All the calcified spots in the population were not thick enough so as to cast a shadow. An institutional review board waiver was obtained because of the retrospective nature of this study. Patient consent was obtained for both the ICA and the OCT.

Optical coherence tomography acquisition

The OCT was performed before the percutaneous coronary intervention and after the administration of intracoronary nitroglycerine (100 µg-200 µg) using the frequency-domain OCT ILUMIEN OPTIS system (Abbott Vascular, United States) and a 2.7-Fr OCT imaging catheter (C7 Dragonfly, Dragonfly Duo or Dragonfly OPTIS; Abbott Vascular, United States). An OCT catheter was advanced distally to the lesion. Also, contrast media was injected manually through the guiding catheter with automatic pullback at a rate of 20 mm/sec for an average pullback distance of 75 mm ± 12.2 mm.

Imaging definition and analysis

The ICA and the OCT imaging were co-registered with respect to each other based on each patients’ anatomical landmarks. Afterwards, the co-registered ICA and OCT imaging had all identifiers removed. Both the ICA and the OCT measurements were assessed independently by two experienced angiography evaluators who were blind to the patients’ information except for the data on the anatomical location of the lesion on the ICA that was assessed on 2 different projections to secure increased accuracy when looking at the vessel. The evaluators then scored the degree of calcium based on the three-tier classification system: minimal or no calcification; calcium covering ≤ 50% of the vessel circumference was classified as “moderate calcification”; calcium covering between 50% and 100% of the vessel circumference was classified as “severe calcification” according to Mintz et al. classification.9 In case of discrepancy between the evaluators, a third evaluator blind to the information of both the patient and the independent reviewers’ assessment was invited to grade the degree of calcification.

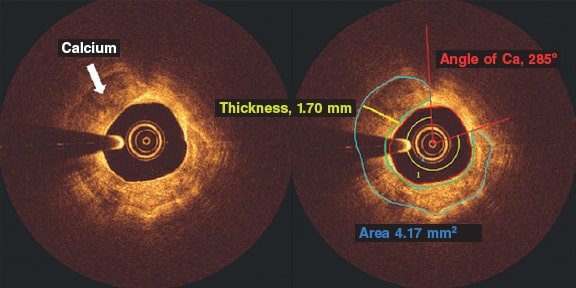

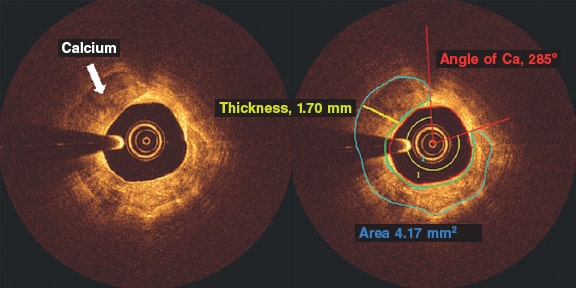

The OCT calcium analysis was performed in the pre-percutaneous coronary intervention iFR-pullbacks. All the OCT analyses of the CP were performed using the QIVUS 3.1 validation utility tool (Medis Medical Imaging, The Netherlands) based on a standardized operating procedure at the core lab (MedStar Cardiovascular Research Network). The CP was analyzed on the area of maximum severity and defined by heterogenous areas of low signal attenuation and sharply demarcated borders. We assessed all pullbacks at lesion site level: the maximum calcium angle, maximum thickness, and length of calcium (number of frames with calcium). The angle of calcium was determined using the center of the lumen as the vertex (figure 1, red rays) as it extended from one clearly delineated border of the calcium plaque to the other. Automatic software detection was used to identify the fibrous cap overlying the calcium area and the maximum and minimum depths of calcium (figure 1, area in green). We tracked down the area of calcium determined by border delineation of the heterogenous calcium plaque. Calcium thickness (figure 1, yellow line) was analyzed on the slice with the maximum angle (figure 1). The length of calcium was derived by the total number of calcium-containing slices and then multiplied by the frame interval.

Figure 1. Optical coherence tomography frames showing a calcified plaque. The angle of calcium was determined using the center of the lumen as the vertex (red rays) and extending from one clearly delineated border of the calcium plaque to the other. Automatic software detection was used to identify the cap of the calcium plaque and the maximum and minimum depths of calcium (area in green). Calcium thickness (yellow line) was analyzed on the slice with the maximum angle after tracking down the area of calcium determined by the delineated borders of the heterogenous calcium plaque. Ca, calcium.

Intra- and inter-rater observer reproducibility

The intra-rater variability of the ICA and the OCT imaging analysis was assessed by evaluating 24 randomly selected images of primary lesions deemed inexistent/mild, moderate, and severe by 2 independent evaluators on both the ICA and the OCT. All OCT measurements including angle, thickness, length, and area were also measured. The same 2 evaluators analyzed the same 24 ICA and OCT images 4 weeks after the early evaluation.

The inter-rater variability of the ICA and the OCT imaging analysis was assessed by evaluating 50 randomly selected images of primary lesions deemed inexistent/mild, moderate, and severe by the same 2 independent evaluators on both the ICA and the OCT. All OCT measurements including angle, thickness, length, and area were also measured. The independent evaluator analyses were then compared. Both the inter and Intra-rater reproducibility were analyzed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient.

Statistical method

The comparison of all categorical variables (presented as counts and percentages) was performed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Continuous data were compared used the Student t test. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed variables or as median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables. The sensitivity and specificity of the ICA with respect to the OCT were determined using standard 2 x 2 tables. Logistic regression determined the relationship between severity as seen on the angiography and the OCT measurements. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis established the optimal cut-off values using the area under the curve and Youden’s index.

RESULTS

Intra- and inter-rater observer reproducibility analysis

There was a 96% agreement (23/24; k = 0.92) on the intra-rater agreement between the analysts. This was indicative of an almost perfect inter-analysis agreement. There was only 1 case of disagreement between moderate calcification vs inexistent/mild calcification.

There was a 94% agreement (47/50; k = 0.72) on the inter-rater agreement between the analysts. This was indicative of substantial inter-rater agreement. There was disagreement between the analysts in 2 cases of moderate vs inexistent/mild calcification and in 1 case of moderate vs severe calcification.

Population

The baseline clinical characteristics of our patients are shown on table 1. Patient population was predominantly male with ages from 56.3 to 75.5. Most patients presented with unstable angina. Comorbidities were present in most of the patients being hypertension the most prevalent of all closely followed by hyperlipidemia. Smokers comprised over half of the patient population. The most common vessel imaged on the OCT was the left anterior descending coronary artery.

Table 1. Patient demographics and angiographic findings

| N = 75 | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.9 ± 9.6 |

| Male | 55 (73.3) |

| Body height, cm | 171.6 ± 11.6 |

| Body weight, kg | 92.4 ± 20.3 |

| Creatinine levels, mg/dL | 1.12 ± 0.95 |

| Diabetes | 28 (37.33) |

| Hypertension | 59 (78.67) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 57 (76) |

| Smoker | 40 (53.33) |

| Hemodialysis | 2 (2.67) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 4 (5.33) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 11 (14.67) |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft | 4 (5.33) |

| Clinical presentation | |

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 0 (0) |

| Non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 7 (9.33) |

| Unstable angina | 43 (57.33) |

| Silent ischemia | 4 (5.33) |

| Angiographic findings | |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 61 (81.33) |

| Femoral access site | 63 (84) |

| Catheter Size, French | 6 |

| Target vessel | |

| Left main coronary artery | 1 (1.33) |

| Left anterior descending coronary artery/Diagonal branches | 61 (81.33) |

| Left circumflex artery/Ramus intermedius branch/Obtuse marginal | 10 (13.33) |

| Right circumflex artery/Posterior descending artery | 7 (9.59) |

| Lesion location | |

| Proximal | 40 (57.14) |

| Mid | 26 (37.14) |

| Distal | 4 (5.71) |

| Lesion and stent parameters | |

| Lesion length, mm | 25.84 ± 13.47 |

| Lesion stenosis | 74.74 ± 15.27 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 3.11 ± 0.53 |

| Stent length, mm | 24.62 ± 8.84 |

| Pullback distance, mm | 75 ± 12.2 |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

Angiographic severity and optical coherence tomography parameters

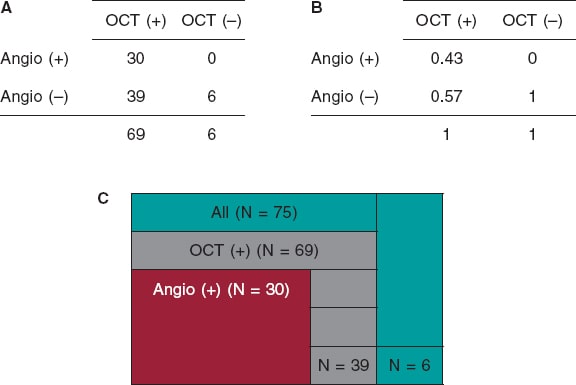

We examined a total of 75 lesions. The detection of CP lesions on the angiography in relation to the OCT is shown on figure 2. The angiography detected fewer CP lesions compared to the OCT that detected positive lesions (n = 69; 92%). All cases of positive angiography were detected by the OCT (n = 30; 100%). The OCT did not find any positive lesions in negative angiographic lesions (n = 6; 100%). A total of 43% of the lesions were both OCT positive and ICA positive. The ICA sensitivity was 95%CI, 0.32-0.56, and the ICA specificity, 95%CI, 0.52-1.0.

Figure 2. Calcified plaques lesions as seen on the angiography in relation to the OCT. A: OCT positive and negative values on the x-axis, and angio positive and negative values on the y-axis. The 4 x 4 table shows the correlation between the OCT and the angio measurements by primary lesion number. B: OCT positive and negative values on the x-axis, and angio positive and negative values on the y-axis. The 4 x 4 table shows the correlation between the OCT and the angio measurements by primary lesion percentage. C: total primary lesion numbers (in green color); the partition on the green color represents the primary lesions not found on the OCT or the angio. All OCT positive primary lesions are represented (in gray color); the partition on the gray color represents the OCT primary lesions not found on the angio. All angio positive lesions are shown (in red color); these lesions were all detected by the OCT. Angio, angiography; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

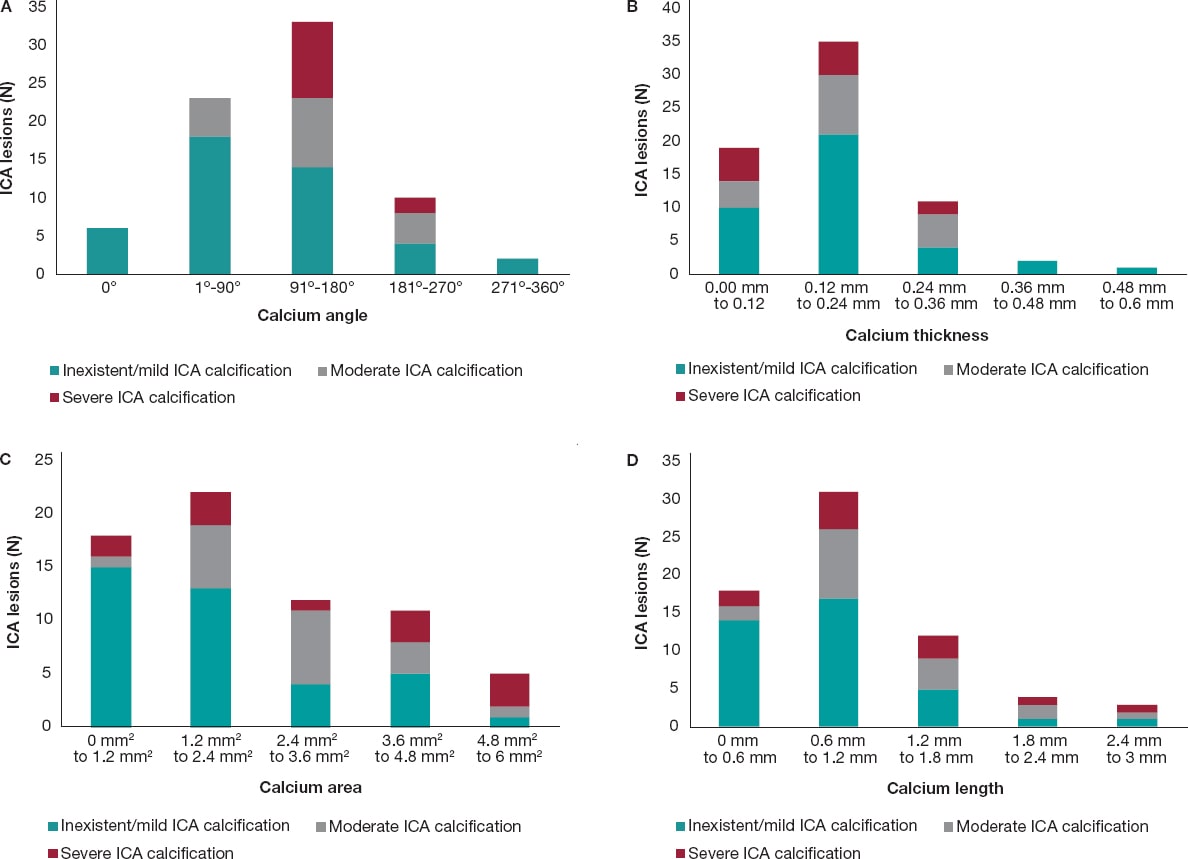

In most of cases, as the calcium angle (figure 3A), thickness (figure 3B), area (figure 3C), and length (figure 3D) increased on the OCT so did the calcium severity of the lesions on the angiography. The association between calcium severity as seen on the angiography and calcium length as seen on the OCT is shown on figure 3D. On the OCT, the severity of CP lesions run parallel to the increasing length seen on OCT.

Figure 3. A: angiographic lesions graded by severity inside the OCT angle measurements. All values are expressed in frequencies. Angles are in ranges of equal proportions based on the degrees seen. The most severe OCT lesions were found in the 91º-180° range followed by the 181º-270° OCT angle measurement. No severe CP lesions were found in the 0°, 1º-90° OCT angle measurements. B: angiographic lesions graded by severity inside the OCT thickness. All lesions are expressed as frequencies. The OCT thickness is expressed in mm and distributed in ranges that go from minimum to maximum values. The highest degree of angiographic calcium score-severe CP-was equally found in 0 mm-0.12 mm, and 0.12 mm-0.24 mm thicknesses on the OCT. C: angiographic lesions graded by severity inside the OCT area. All lesions are expressed as frequencies. The OCT area is expressed in mm2 and distributed in ranges that go from minimum to maximum values. The highest degree of angiographic calcium score-severe CP-was found from 4.8 mm2 to 6 mm2. D: angiographic lesions graded by severity inside the OCT length. All lesions are expressed as frequencies. The OCT length is expressed in mm and distributed in ranges that go from minimum to maximum values. The highest degree of angiographic calcium score- severe CP- was detected from 0.6 mm to 1.2 mm. CP, calcified plaques; ICA, interventional coronary angiography; OCT, optical coherence tomography.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of our study are: a) compared to the OCT, the ICA has a low sensitivity and a high specificity for the detection of calcium; b) as calcium angle, thickness, area, and length increased on the OCT so did the number of angio-defined severe CP lesions.

The ICA provides 2D real-time imaging with in-vivo characteristics of the lumen profile.15 Conversely, the invasive 3D-OCT imaging modality has the highest resolution to characterize variations in the composition of the plaque.11,16 The ICA detection of angiographic lesions has been used for decades. However, studies have shown that the ICA capabilities to detect calcified plaques in the arterial wall are poor.6,11,17 Some studies have compared the ICA characterization and quantification of plaque to the coronary computed tomography angiogram and the intravascular ultrasound, but few have looked into ICA plaque characterization and quantification with the OCT.6 Our study examined the sensitivity and specificity of ICA compared to the OCT. We examined 75 lesions and found that ICA sensitivity and specificity were 32%-56%, and 52%-100% with a 95%CI, respectively. Sensitivity was lower compared to former studies that showed a 50.9% sensitivity and a 95.1% specificity.6 The sensitivity of ICA is low because it only provides a 2D projection of the lesion and its resolution compared to the OCT is worse.18,19

The OCT detected all CPs present on the ICA (n = 30) and, also, lesions that were not present on the ICA (n = 39). On the angiography, the presence of CP is indicative that calcification has large CP characteristics on the OCT (eg, angle, thickness, and area). Our study concluded that severe calcifications on the ICA are seen with higher calcium angles on the OCT as the study conducted by Wang et al proved.6 The clinical implication of this is that when the ICA detects a calcified lesion, whether moderate or severe, the clinician can be sure that this calcification is, actually, present. The OCT would be the logical next step for a better characterization of the CP. Determining the morphology of the calcified lesion (eg, superficial, deep, or nodular) on the OCT allows selecting the optimal lesion preparation strategy. Also, the OCT detected calcifications that the ICA simply could not find, indicative that the ICA alone is not reliable to detect CPs. Therefore, with suspected lesions, the OCT should be the next step for a comprehensive assessment of these lesions.

The OCT measurements of a calcified lesion thickness, length, and area are unique to this technology because the OCT is the only invasive imaging modality capable of measuring these values.6 Thicknesses > 0.5 mm are associated with stent underexpansion.7,20 We did not explore this in our population since not all lesions received percutaneous coronary intervention. We did expand, however, the OCT analysis to include the depth, and area of calcium on the OCT. We found that as the area increased on the OCT so did the number of severe lesions on the ICA. We found that most severe CP lesions were in the 4.8-6 mm2 range. Perhaps, calcium areas > 5 mm2 may be the fourth “5” in the OCT-based “rule of five” that identifies the CP features associated with poor stent expansion.7

Study limitations

This was a retrospective observational study with its inherent limitations. The sample size was relatively small.

CONCLUSIONS

Invasive coronary angiography has a low sensitivity and a high specificity for the detection of calcified plaques compared to the OCT. As calcium angle, thickness, area, and length increased on the OCT so did number of angio-defined severe CP lesions.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

C. McGuire: study idea, data mining, manuscript draft, and analysis; E. Schlofmitz: study idea, data mining, critical review of the manuscript; G. D. Melaku, K. O. Kuku, and Y. Kahsay: data mining, critical review of the manuscript; R. Schlofmitz, and A. Jeremias: writing, critical review of the manuscript; H. M. Garcia-Garcia: study idea, data analysis, data mining, preparation, and critical review of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

H.M. Garcia-Garcia declared having received institutional grant support from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Abbott, Neovasc, Shockwave, Phillips, and Corflow. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Percutaneous coronary interventions rely on angiography to inform most of the clinical decisions on lesion preparation; however, the extent of calcium is poorly assessed on the angiography.

- The relation between the ICA and the OCT regarding the severity of CP was examined using thickness and angle measurements on the OCT.

- No examination has been conducted of all OCT measurements and their relation to the severity of CP as seen on the ICA.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Compared to the OCT, the ICA has a low sensitivity but a high specificity to detect severely calcified plaques.

- As calcium increased on the OCT measurements regarding area, length, thickness, and angle so did the number of angio-defined severe CP lesions, which is indicative that all OCT measurements can be used to detect severely calcified lesions.

- The OCT offers a feasible alternative to the angiography regarding calcium assessment; it extends calcium characterization by providing detailed information to shed light on the use of dedicated calcium debulking therapies for lesion preparation.

REFERENCES

1. Miao Benjamin, Hernandez Adrian V., Alberts Mark J., Mangiafico Nicholas, Roman Yuani M., Coleman Craig I. Incidence and Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in patients With Established Atherosclerotic Disease or Multiple Risk Factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e014402.

2. Guedeney P, Claessen BE, Mehran R, et al. Coronary Calcification and Long-Term Outcomes According to Drug-Eluting Stent Generation. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1417-1428.

3. Costa JR, Sousa A, Moreira AC, et al. Incidence and Predictors of Very Late (?4 Years) Major Cardiac Adverse Events in the DESIRE (Drug-Eluting Stents in the Real World)-Late Registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;3:12-18.

4. Conway C, McGarry JP, Edelman ER, McHugh PE. Numerical Simulation of Stent Angioplasty with Predilation: An Investigation into Lesion Constitutive Representation and Calcification Influence. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017;45:2244-2252.

5. Waters DD, Azar RR. The Curse of Target Lesion Calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1855-1856.

6. Wang X, Matsumura M, Mintz GS, et al. In Vivo Calcium Detection by Comparing Optical Coherence Tomography, Intravascular Ultrasound, and Angiography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:869-879.

7. Fujino A, Mintz G, Matsumura M, et al. TCT-28. A New Optical Coherence Tomography-Based Calcium Scoring System to Predict Stent Underexpansion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70 (18, Supplement):B12-B13.

8. Lee T, Mintz GS, Matsumura M, et al. Prevalence, Predictors, and Clinical Presentation of a Calcified Nodule as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:883-891.

9. Mintz GS, Popma JJ, Pichard AD, et al. Patterns of calcification in coronary artery disease. A statistical analysis of intravascular ultrasound and coronary angiography in 1155 lesions. Circulation. 1995;91:1959-1965.

10. Brezinski ME, Tearney GJ, Bouma BE, et al. Imaging of coronary artery microstructure (in vitro) with optical coherence tomography. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:92-93.

11. Wang Ying, Osborne Michael T., Tung Brian, Li Ming, Li Yaming. Imaging Cardiovascular Calcification. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008564.

12. Oosterveer TTM, van der Meer SM, Scherptong RWC, Jukema JW. Optical Coherence Tomography: Current Applications for the Assessment of Coronary Artery Disease and Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Cardiol Ther. 2020;9:307-321.

13. Gharaibeh Y, Prabhu DS, Kolluru C, et al. Coronary calcification segmentation in intravascular OCT images using deep learning: application to calcification scoring. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2019;6:045002.

14. Kume T, Akasaka T, Kawamoto T, et al. Assessment of Coronary Intima - Me-dia Thickness by Optical Coherence Tomography. Circ J. 2005;69:903-907.

15. Ryan Thomas J. The Coronary Angiogram and Its Seminal Contributions to Cardiovascular Medicine Over Five Decades. Circulation. 2002;106:752-756.

16. Kubo T, Imanishi T, Takarada S, et al. Assessment of culprit lesion morphology in acute myocardial infarction: ability of optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and coronary angioscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:933-939.

17. Tuzcu EM, Berkalp B, De Franco AC, et al. The dilemma of diagnosing coronary calcification: Angiography versus intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:832-838.

18. Lee CH, Hur S-H. Optimization of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Optical Coherence Tomography. Korean Circ J. 2019;49:771-793.

19. Park S-J, Kang S-J, Ahn J-M, et al. Visual-functional mismatch between coronary angiography and fractional flow reserve. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:1029-1036.

20. Fujino A, Mintz GS, Lee T, et al. Predictors of Calcium Fracture Derived From Balloon Angioplasty and its Effect on Stent Expansion Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1015-1017.

* Corresponding author: Division of Interventional Cardiology, MedStar Washington Hospital Center, 100 Irving St, NW Washington D.C. 20010, United States.

E-mail addresses: ; (H.M. Garcia-Garcia)

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Drug-eluting balloon (DEB) angioplasty is an effective technique to treat in-stent restenosis (ISR). Neointimal modification with cutting balloon (CB) or scoring balloon (SB) enhances the angiographic results of DEB, but with no benefits have been reported in the clinical endpoints at the mid-term. There is lack of information on the clinical long-term results of this strategy. We aim to compare very long-term results of CB before DEB vs standard DEB to treat real-world patients with ISR.

Methods: Retrospective cohort registry of DEB PCIs to treat ISR defined by the use of CB. The primary endpoint was clinically driven target lesion revascularization (TLR) at 5 years. The secondary endpoints were based on the ARC-2 criteria.

Results: From January 2010 to December 2015, 107 ISRs were treated with DEB in 91 patients. CBs were used in 51 lesions (46 patients). Both cohorts were well balanced regarding clinical, lesion, and procedural characteristics. Compared to standard DEBs, CBs showed lower, although statistically non-significant rates, of TLR at 5 years (9.8% vs 23.6%, OR, 0.36; 95% confidence interval 0.19 to 1.09 P = .05). The Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence of time until TLR showed similar results (log-rank test P value = .05) with similar rates of TLR at 1 year (3.9% vs 7.1%, P = .68) as curve separation in the long-term. There were no differences in the secondary endpoints. No stent thrombosis was reported.

Conclusions: In a real-world setting, neointimal modification with CB before DEB vs standard DEB to treat ISR shows lower, although statistically non-significant rates of TLR at 5 years. This benefit has been confirmed in the long-term and is consistent with bare-metal and drug-eluting stents.

Keywords: Drug-eluting balloon. In-stent restenosis. Cutting/scoring balloon.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El uso de balón farmacoactivo (BFA) es una estrategia efectiva en el tratamiento de la reestenosis de stents coronarios (RIS). La modificación neointimal con balón de corte (BC) o incisión junto con BFA se asocia a mejores resultados angiográficos, aunque sin impacto en eventos clínicos a medio plazo. Los resultados clínicos de esta estrategia a muy largo plazo en la vida real son desconocidos. Se evaluó la eficacia de BC junto con BFA frente a BFA estándar en un registro de pacientes de la vida real con RIS a muy largo plazo (5 años).

Métodos: Registro retrospectivo de 2 cohortes de pacientes con RIS tratados con BFA, definidas por el uso de BC. El evento primario fue la tasa de revascularización clínicamente indicada de la lesión tratada a 5 años. Se valoraron eventos secundarios según los criterios ARC-2.

Resultados: Entre enero de 2010 y diciembre de 2015 se usó BFA en 107 RIS en 91 pacientes. En 51 lesiones (46 pacientes) se utilizó BC. Ambas cohortes presentaron similares características clínicas y de procedimiento. Respecto al uso estándar de BFA, el BC consiguió una reducción numérica, pero no significativa, en la tasa de revascularización de la lesión tratada a 5 años (9,8% frente a 23,6%; odds ratio = 0,36; intervalo de confianza del 95%, 0,19-1,09; p = 0,05). El análisis de incidencia acumulada de Kaplan-Meier mostró resultados parecidos (log-rank, p = 0,05), con similar tasa de eventos a 1 año (3,9% frente a 7,1%; p = 0,68), y separación de las curvas con el tiempo. No se evidenciaron diferencias en los eventos secundarios. No hubo trombosis de stent en la cohorte.

Conclusiones: En una cohorte de la vida real, la modificación neointimal de la RIS con BC junto con BFA, en comparación con BFA estándar, logra una reducción numérica, pero no significativa, en la tasa de revascularización de la lesión tratada a 5 años. El beneficio de esta estrategia se evidencia a largo plazo y es consistente entre RIS de stent convencional y de stent farmacoactivo.

Palabras clave: Balon farmacoactivo. Reestenosis. Balon de corte.

Abreviaturas

BC: balón de corte o incisión. BFA: balón farmacoactivo. RIS: reestenosis de stent coronario. RLT: revascularización de la lesión tratada. SFA: stent farmacoactivo. SM: stent convencional.

INTRODUCTION

In-stent restenosis (ISR) is a common problem in the routine clinical practice regarding percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), and its management is associated with high rates of target lesion revascularization (TLR).1 Together with the implantation of a new everolimus drug-eluting stent, the PCI with drug-coated balloon (DCB) is the strategy of choice to treat ISR after bare-metal stent (BMS) and drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation, and has a class I indication after confirmation that it can reduce the rate of TLR at the follow-up without having to implant a new layer of metal into the artery.2-5 Despite of this, TLR is still high in the long-term (up to 20% at 3 years),6-11 which is suggestive that new strategies may be needed to improve these results.

The cutting balloon (CB) consists of small blades or nitinol bands on its surface to optimize the predilatation of coronary lesions by performing controlled fractures of the atheromatous plaque. Compared to the plain old balloon angioplasty, its use for the management of ISR is associated with structural changes of the neointima and acute improvements of the lumen area,12 although no angiographic or clinical benefit has been reported in the mid-term.13,14

The efficacy of the DCB depends on the transfer of drug from the surface of the balloon to the tissue where it exerts it antiproliferative effect.15 Theoretically speaking, greater the neointimal disarrays are associated with more effective transfers and smaller issue thickness. As a matter of fact, preclinical studies have suggested a greater effect of DCB inhibiting neointimal growth.16 This greater disarray and reduction of the neointima can be achieved using a CB before the DCB.

Although this hypothesis has not been confirmed in animal models in the short-term,17 the strategy has shown better angiographic results in the mid-term (6 to 8 months) (significant reduction of binary restenosis), but no effect on TLR or clinical events at the 1-year follow-up.18 No long-term results have been published on the use of this strategy.

Our objective was to assess the very long-term results of the use of CB plus DCB to treat ISR.

METHODS

Retrospective registry of cohorts of real-world patients with, at least, 1 ISR treated with DCB at a single high-volume PCI center (> 800/year) and a 5-year follow-up. Two different cohorts were defined based on the use of CB prior to the PCI with DCB (C_DCB) or standard DCB (S_DCB). The C_DCB cohort was defined by the use of, at least, 1 cutting balloon (Flextome Cutting Balloon, Boston Scientific, United States) or 1 scoring balloon (ScoreFlex, OrbusNeich, China). The use of the CB was left to the operator’s discretion. The ISR was defined as an angiographic stenosis > 50% in 2 different orthogonal radiographic projections inside the stent or < 5 mm from its borders plus symptoms of angina or objective confirmation of myocardial ischemia or fractional flow reserve/positive instantaneous wave-free ratio. Lesions were treated with 2 types of drug-coated balloons based on their availability at the time: the SeQuent Please (B. Braun Surgical, Germany) or the Pantera Lux (Biotronik, Switzerland). Data on the long-term progression of patients with ISR treater with the SeQuent Please DCB in this cohort regardless of the use of CB were reported beforehand.19

Exclusion criteria were cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest in the index event, the presence of ≥ 3 layers of metal in the lesion with ISR and a contraindication to dual antiplatelet therapy with acetylsalicylic acid and a P2Y12 inhibitor for, at least, a month.

The clinical and procedural characteristics were obtained from the center and the cath lab databases. The coronary study of the lesions was performed with the Xcelera system (Philips, The Netherlands) using the projection with the highest degree of stenosis. The Mehran classification of ISR was used to categorize the lesions.20 The strategy of the procedure including the use and type of CB was left to the operator’s criterion. DCB dilatation lasted for, at least, 60 seconds at nominal pressure. The PCI, management, and previous and later treatment of the patients was performed based on the routine clinical practice.

The study was conducted in observance of the criteria established at the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Council on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines (ICH-GCP). Also, it was authorized by Hospital Clínico Lozano Blesa (Zaragoza, Spain) management and ethics committee. No informed consents were needed given the retrospective nature of the study. A 5-year long follow-up period was arranged. Every follow-up was performed by checking the electronic database of the regional healthcare system where all the patient’s clinical events were thoroughly detailed. Data were anonymized through internal numerical identification at the cath lab.

All events were defined in a standard way according to the ARC-2 consensus.21 The primary endpoint was the need for TLR with a clinically indicated DCB at 5 years and estimated on the overall number of all target lesions. Clinically indicated TLR was defined as a new-onset ISR > 70% or > 50% of the target lesion in the presence of ischemic symptoms, a positive inducible ischemia on stress testing dependent on the vessel or fractional flow reserve values ≤ 0.80 or instantaneous wave-free ratio values ≤ 0.89.

Secondary endpoints were the presence or lack of target vessel revascularization, and target vessel myocardial infarction (according to the universal definition22), all-cause mortality, death due to cardiac causes (acute myocardial infarction, severe arrhythmia, heart failure, unwitnessed or unknown death) or cardiovascular death (cardiac or stroke induced or due to other cardiovascular processes), BARC type ≥ 3 bleeding, stroke (new neurologic deficit > 24 h duration) or a composite endpoint of target lesion failure (TLR + target vessel myocardial infarction + cardiovascular death), target vessel failure (target vessel revascularization + target vessel myocardial infarction + cardiovascular death) or patient-oriented composite endpoint (any revascularization + acute myocardial infarction + stroke + overall death). These endpoints were estimated on the overall number of patients. Definitive or probable stent thrombosis was also defined based on the ARC-2 criteria and estimated on the overall number of lesions.

Data mining and analysis were performed using the SPSS 19.0. statistical software (IBM, United States). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were expressed as relative percentage. The cumulative incidence of the endpoints at the follow-up was also estimated. The variables and the group endpoints studied were compared on a bivariate analysis using the chi-square test (or Fisher’s exact test, when appropriate) or the Student t test regarding the quantitative variables. Cox regression analysis was performed to estimate the primary endpoint predictors (including the variables associated with P values < .1). Survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method to build the cumulative incidence curve of time to the primary endpoint based on the strategy of treatment used. P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 107 ISRs were treated with DCBs in 95 procedures performed on 91 patients from January 2010 through December 2015 (in 4 patients the PCI with DCB was repeated at the follow-up, in 1 case using a different DCB on the same previously treated lesion). A total of 51 lesions (42 patients) were treated with a PCI plus CB + DCB (C_DCB), and 56 lesions (49 patients) with standard DCB (S_DCB). A total of 53 lesions were treated with the SeQuent Please device, and 54 with the Pantera Lux. The cutting balloon and the scoring balloon were used in 36 and 15 lesions, respectively.

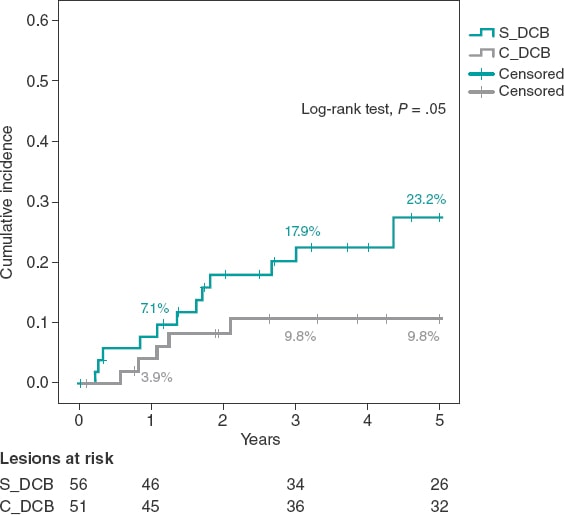

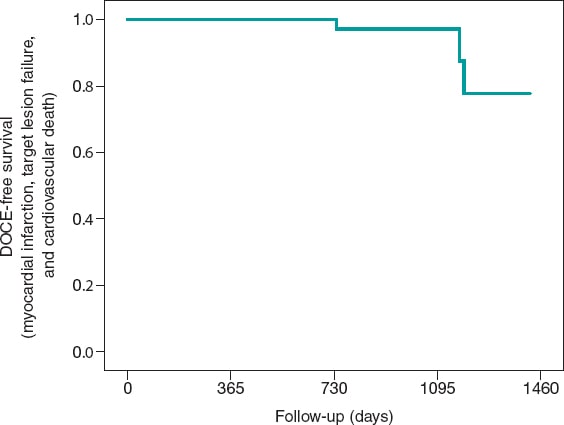

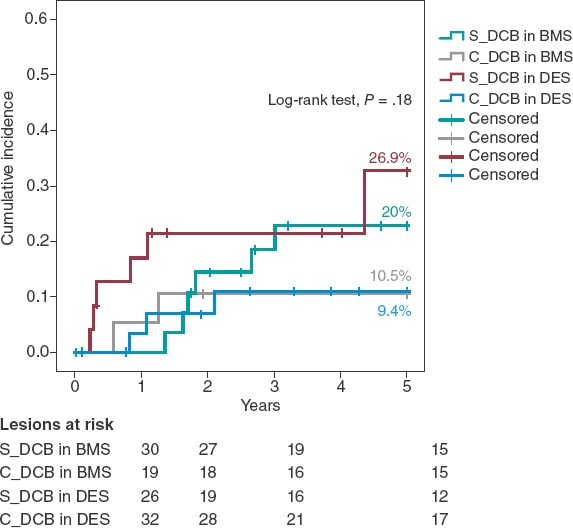

The study cohorts were similar regarding the clinical characteristics (table 1), and the lesion and procedural characteristics (table 2). Some of the differences reported in the C_DCB group where that radial access was more common, and the size of the stent and minimum lumen diameter were greater, although with a similar percent diameter stenosis of the lesion before and the after the PCI. Patients had a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors including diabetes in 35% of the cases. A total of 47 new coronary angiographies were performed at the follow-up. In 29 of these the target lesion had good results. The rate of new coronary angiography was similar in both groups (44.6% vs 41.2% in the C_DCB group. P = .71). A total of 18 TLRs were performed at the follow-up (16.8%) of which 17 were treated with a PCI (16 stent-in-stent), and 1 with coronary artery bypass graft. The rate of TLR was numerically lower in the C_DCB group at 1 (3.9% vs 7.1%; P = .68) and 3 years (9.8% vs 17.9%; P = .23). Compared to the S_DCB strategy, the use of the C_DCB reduced the 5-year rate of TLR although not statistically significant (9.8% vs 23.2%; OR, 0.36; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.19-1.09; P = .05). The Kaplan-Meier analysis of the cumulative incidence curve revealed the differences seen at the 5-year follow-up (log-rank test, P = .05) with a similar 1-year event rate and curve separation consistent with the passing of the follow-up period (figure 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristic of the patients

| S_DCB | C_DCB | P | |

| N = 49 patients/ 56 lesions | N = 42 patients/ 51 lesions | ||

| Age | 68.9 ± 11.3 | 67.7 ± 10 | .58 |

| Male | 85.7% (35) | 83.3% (35) | .75 |

| Arterial hypertension | 26.8% (14) | 23.8% (10) | .6 |

| Dyslipidemia | 46.9% (23) | 28.6% (12) | .7 |

| Smoking | 61.2% (30) | 57.1% (24) | .69 |

| Diabetes | 37.5% (21) | 35.3% (18) | .81 |

| AF in oral anticoagulants | 22.4% (11) | 19% (8) | .38 |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 55.1% (27) | 50% (21) | .62 |

| Previous coronary artery bypass graft | 6.1% (3) | 4.8% (2) | 1 |

| CKD (GFR < 60mL/min) | 32.7% (16) | 33.3% (14) | .94 |

| LVEF (%) | 54 ± 10 | 55 ± 9 | .51 |

|

AF, atrial fibrillation; CKD, chronic kidney disease; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. |

|||

Table 2. Lesion and procedural characteristics

| S_DCB | C_DCB | P | S_DCB | C_DCB | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 49 patients/ 56 lesions | N = 42 patients/ 51 lesions | N = 49 patients/ 56 lesions | N = 42 patients/ 51 lesions | |||||

| Procedural characteristics | Lesion characteristics | |||||||

| Clinical signs | .87 | Location of ISR | .35 | |||||

| Stable angina | 55.4% (31) | 56.9% (29) | LAD | 53.6% (30) | 45.1% (23) | |||

| Unstable angina/NSTEACS | 41.1% (23) | 41.2% (21) | LCX | 23.2% (13) | 15.7% (8) | |||

| STEACS | 3.6% (2) | 2% (1) | RCA | 16.1% (9) | 31.4% (16) | |||

| Radial access | 55.4% (31) | 78.4% (40) | .01 | LMCA | 5.4% (3) | 3.9% (2) | ||

| DCB caliber (mm) | 3.03 ± 0.37 | 3.15 ± 0.42 | .13 | Coronary artery bypass graft | 1.8% (1) | 3.9% (2) | ||

| DCB length (mm) | 20.2 ± 5.8 | 19.5 ± 4.7 | .53 | Mehran's angiographic classification of ISR pattern | .42 | |||

| DCB inflation pressure (atm) | 14 ± 3 | 14 ± 3 | .81 | IA | 1.8% (1) | 3.9% (2) | ||

| CB caliber (mm) | N/A | 2.93 ± 0.45 | IB | 3.6% (2) | 0% (0) | |||

| CB length (mm) | N/A | 8 ± 3 | IC | 41.1% (23) | 49% (25) | |||

| CB inflation pressure (atm) | N/A | 14 ± 3 | ID | 1.8% (1) | 3.9% (2) | |||

| NCB | 53.6% (30) | 70.6% (36) | .07 | II | 21.4% (12) | 27.5% (14) | ||

| NCB caliber (mm) | 3.12 ± 0.42 | 3.28 ± 0.43 | .14 | III | 21.4% (12) | 11.8% (6) | ||

| NCB length (mm) | 13.2 ± 3.1 | 12.6 ± 3.8 | .65 | IV | 8.9% (5) | 3.9% (2) | ||

| NCB inflation pressure (atm) | 18 ± 4 | 18 ± 3 | .74 | ISR based on type of stenting | .4 | |||

| Intracoronary imaging | 8.9% (5) | 5.9% (3) | .55 | BMS | 53.6% (30) | 37.3% (19) | ||

| Multivessel disease | 62.7% (32) | 47.7% (21) | .14 | DES | 33.9% (19) | 45.1% (23) | ||

| Complete revascularization | 82.4% (42) | 93.2% (41) | .13 | DES in BMS | 8.9% (5) | 11.8% (6) | ||

| P2Y12 inhibitor | .64 | DES in DES | 3.6% (2) | 5.9% (3) | ||||

| Clopidogrel | 88.2% (45) | 81.6% (36) | Time from implantation | 4.1 ± 4.8 | 3.8 ± 5 | .69 | ||

| Prasugrel | 3.9% (2) | 4.5% (2) | Bifurcation | 32.1% (18) | 23.5% (12) | .32 | ||

| Ticagrelor | 7.8% (4) | 13.6% (6) | Stent caliber (mm) | 2.96 ± 0.43 | 3.1 ± 0.56 | .02 | ||

| Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy | .27 | Stent length (mm) | 22.4 ± 6.5 | 22.8 ± 7.1 | .75 | |||

| 1 month | 3.9% (2) | 2.3% (1) | Reference diameter (mm) | 2.98 ± 0.48 | 3.12 ± 0.53 | .16 | ||

| 3 months | 21.6% (11) | 9.1% (4) | Minimum lumen diameter (mm) | 0.73 ± 0.51 | 0.68 ± 0.5 | .67 | ||

| 6 months | 21.6% (11) | 34.1% (15) | Length (mm) | 13.2 ± 5.6 | 11.7 ± 5.3 | .18 | ||

| 12 months | 52.9% (27) | 54.5% (24) | Stenosis (%) | 72 ± 18 | 75 ± 16 | .3 | ||

| Minimum lumen diameter post-PCI (mm) | 2.43 ± 0.46 | 2.77 ± 0.62 | .002 | |||||

| Acute lumen gain (mm) | 1.7 ± 0.64 | 2.08 ± 0.83 | .01 | |||||

| Stenosis post-PCI (%) | 14 ± 5 | 14 ± 6 | .45 | |||||

| Final TIMI grade 3 flow | 98.2% (55) | 100% (51) | 1 | |||||

|

BMS, bare-metal stent; CB, cutting balloon; DCB, drug-coated balloon; DES, drug-eluting stent; ISR, in-stent restenosis; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCX, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; NCB, non-compliant balloon; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; STEACS, ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

||||||||

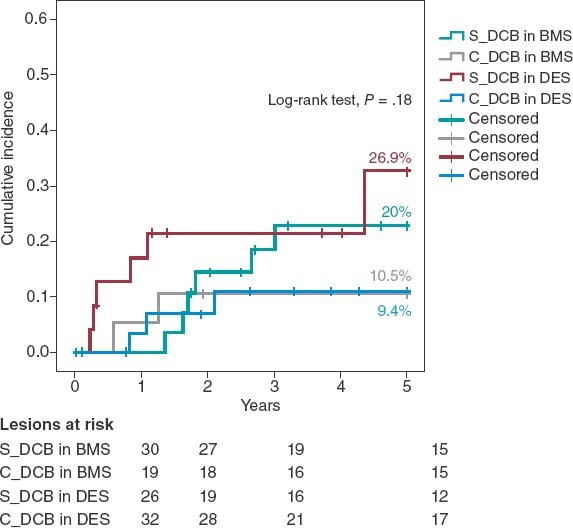

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier analysis of the 5-year cumulative incidence of target lesion revascularization. DCB, drug-coated balloon.

The 5-year cumulative incidence of secondary endpoints is shown on table 3. The incidence rate of target vessel-related composite endpoints (target lesion failure and target vessel failure) was numerically lower in the C_DCB group although not statistically significant. No differences were found in the remaining secondary endpoints. The overall mortality rate at the follow-up was 31.8% (n = 19) being neoplasms the most common cause (n = 7). The incidence rates of stroke and patient-oriented composite endpoint were high (10.9% and 51.6%, respectively), which was consistent with an old cohort with high cardiovascular risk. No cases of definitive or probable stent thrombosis were seen at the follow-up.

Table 3. 5-year cumulative incidence of primary and secondary endpoints

| S_DCB | C_DCB | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 49 patients/ 56 lesions | N = 42 patients/ 51 lesions | ||

| Primary endpoint | |||

| TLR (clinically justified) | 23.2% (13/56) | 9.8% (5/51) | .05 |

| Secondary endpoints | |||

| Target vessel revascularization | 28.6% (16/56) | 17.6% (9/51) | .18 |

| Any revascularization | 28.6% (14/49) | 26.2% (11/42) | .8 |

| Target vessel myocardial infarction | 7.1% (4/56) | 5.9% (3/51) | .79 |

| Myocardial infarction | 18.3% (9/49) | 7.2% (3/42) | .19 |

| Death due to cardiac causes | 4.1% (2/49) | 4.8% (2/42) | 1 |

| Cardiovascular death | 16.3% (8/49) | 11.9% (5/42) | .54 |

| Overall mortality | 36.7% (18/49) | 26.2% (11/42) | .28 |

| Stroke | 10.2% (5/49) | 11.9% (5/42) | .55 |

| BARC type 3-5 bleeding | 7.1% (4/49) | 3.9% (2/42) | .68 |

| Target lesion failure | 37.5% (21/56) | 25.5% (13/51) | .18 |

| Target vessel failure | 41.1% (23/56) | 25.5% (13/51) | .08 |

| POCE | 53.1% (26/49) | 50% (21/42) | .77 |

|

BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; DCB, drug-coated balloon; POCE, patient-oriented composite endpoints; TLR, target lesion revascularization. |

|||

A Kaplan-Meier subanalysis based on ISR after BMS or DES implantation showed that the C_DCB strategy consistently reduced the 5-year rate of TLR in half with both types of stent although not statistically significant (figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier analysis of the 5-year cumulative incidence of target lesion revascularization based on whether the stent is made out of metal or is drug-eluting. BMS, bare-metal stent; DCB, drug-coated balloon, DES, drug-eluting stent.

Aside from the C_DCB no association was found between the variables and the 5-year rate of TLR except for the location of ISR that was 100% in cases found in coronary artery bypass graft stents (3 cases) compared to 14.4% in cases found in the native coronary tree (P = .003). The 5-year rate of TLR was similar in diabetic patients (17.9% vs 16.2%; P = .81) in the ISR of DESs (17.2% vs 16.3%; P = .9) and in stents < 3 mm (12.9% vs 18.4%; P = .58) without any differences based on the type of DCB used (Sequent, 20.4% vs Pantera, 13.2%; P = .32). In the Cox regression analysis, the use of the C_DCB was not an independent predictor of TLR at 5 years being the ISR of a coronary artery bypass graft the only independent predictor (OR, 5.4; 95%CI, 1.5-19.8; P = .01).

DISCUSSION

As far as we know, the study presented here is the first one to confirm:

-

- The use of a CB in connection with a DCB in the ISR setting shows a tendency to reduce the rate of TLR.

-

- The benefit of this strategy is evident in the long-term.

-

- The benefit seems to be consistent in ISR after BMS and DES implantation.

-

- The strategy is safe and there are no traces of stent thrombosis when a CB is used.

Compared to the plain old balloon angioplasty for the management of ISR, the CB achieves greater lumen areas because it breaks down the elastic and fibrotic continuity of the neointima by reducing its integrity and resistence.12 However, this acute angiographic improvement is not associated with lower but high rates of TLR (18% to 29%) at the 1-year follow-up.13,14 Similarly, in our series, the use of the CB is associated with a significant increase of minimum lumen diameter and acute gain after the procedure (table 2) despite the fact that the caliber of non-compliant balloons and DCBs was similar between both groups. Although stent diameter was slightly larger in the C_DCB group, the final percent stenosis did not change significantly between both groups; still, this may be an important piece of information in our results since the size of the vessel has been described as an independent predictor of new restenosis.23

The use of the DCB to treat ISR is something common after several meta-analyses revealed that, together with DES implantation with in-stent everolimus, this strategy is the most effective one to avoid new revascularizations.2-4 Afterwards, in the RIBS IV (with DES) and RIBS V (with BMS) clinical trials Alfonso et al. proved the long-term superiority of DES implantation with in-stent everolimus.8,9,24 However, the philosophy of not adding a new metal layer (or delay it through time) and questions associated with its long-term safety10,11 have turned DCB implantation into a common practice to treat ISR. Added to the RIBS IV-V studies, other trials have reported on the long-term effectiveness of DCB (PEPCAD7 with BMS, and PEPCAD-DES6 and ISAR-DESIRE 310 with DES). Overall, in these 5 studies, a total of 94 TLRs were reported in 524 ISRs treated with DCB, which is a 3-year rate of TLR of 17.9%. These results are accurately reproduced in our S_DCB cohort with rates high enough to justify looking into ways to improve the efficacy of DCBs.

The efficacy of DCBs is based on a transfer of the drug to the neointima of ISR where it exerts its antiproliferative effect. The proper preparation of the lesion by reducing neointimal thickening and increasing the surface of contact with the balloon is the key to achieve successful DCB implantations.15 Preclinical studies suggest that greater neointimal disarrays can increase the release and retention of the drug into the tissue, thus increasing its effects.16 Considering the greater acute lumen gain and controlled disarray that the CB provides, results can improve if used together with the DCB. This hypothesis was put to the test, but not proven, in a preclinical trial. The reason was that the use of the CB was not associated with a lower neointimal volume or acute lumen loss. Nonetheless, this assessment was made was very early (28 days).17

The synergistic effects of CB plus DCB were also confirmed by Scheller et al.25 in the PATENT-C trial. They took a different angle and studied the addition of an antiproliferative drug (paclitaxel) to the scoring balloon that reduced the 1-year rate of TLR significantly (3% vs 32%; P = .004). This information is consistent with the 1-year rate of TLR of 3.9 seen in our C_DCB cohort. From a new and different angle too, while still observing the philosophy of not leaving any material behind in the long-term after the PCI, Alfonso et al. conducted the RIBS VI Scoring trial and analyzed the impact of a CB before bioresorbable scaffold implantation to treat ISR. However, the 1-year rate of TLR was not reduced (9.8 vs 11.1%).26

Two randomized clinical trials have assessed the effect of CB implantation before DCB implantation to treat ISR. Aoki et al.27 found no angiographic differences at the 8-month follow-up in the ELEGANT trial. However, this was a comparative study vs a non-compliant balloon. Kufner et al.18 specifically tested the effects of CB implantation in the ISAR-DESIRE 4 trial. The primary endpoint was an angiographic result that confirmed that this strategy effectively reduced binary ISR at the 6 to 8-month follow-up. However, no differences were seen when the clinical events or TLR were assessed at the 1-year follow-up (16.2% vs 21.8%; P = .26). Qualitatively speaking, these results are consistent with what our series described because, although long-term benefits were reported, the 1-year rate of TLR did not change between our groups. No long-term data have ever been published so our cohort cannot be compared to corroborate the benefits described. Quantitatively speaking, we saw differences in the 1-year rate of TLR, much lower in our study (3.9% vs 7.1%). Three may be the reasons for this. In the first place, the scheduled angiographic assessment of the ISAR-DESIRE 4 trial because if we look at the Kaplan-Meier analysis of the TLR, in this study more clinical events were reported at the 6 to 8-month follow-up (when the angiographic assessment occurred). This is suggestive of a TLR guided by angiographic criteria (the so-called oculodilatory reflex) and not clinically justified as it was the case in our series. Secondly, the exclusive use of the scoring balloon vs the predominant use of the CB in our series since the CB achieves greater neointimal disarray and larger residual lumen diameters, thus increasing the efficacy of the DCB. Thirdly, the exclusive management of ISR after DES implantation vs ISR after any other type of stent implantation (BMS or DES) of our series since different authors have proposed the lower efficacy of the DCB to treat ISR after DES implantation.11,28 Based on this previous knowledge a subanalysis of the C_DCB strategy based on the type of stent used was conducted (figure 2). A consistent efficacy both in BMSs and DESs was seen with a similar 5-year rate of TLR in both subgroups (10.5% and 9.4% respectively)

Treating ISR with DCBs is a safe strategy associated with very low rates of stent thrombosis (around 1%) at the long-term follow-up.11 The role that a greater CB-induced neointimal tissue disarray plays in the appearance of thrombotic phenomena on the lesion is unknown. Consistent with the mid-term results of theISAR-DESIRE 4 trial, in our series, long-term target lesion thrombosis is null, which is a guarantee that the use of C_DCB is safe.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. It is a retrospective, observational, and single-center study. Although the use of the DCB is the treatment of choice for the management of ISR in our center, it is possible that patients with more unfavorable ISR may have been excluded for having been treated with a DES. The use of intracoronary imaging was limited and the characterization of ISR could have given relevant information on the therapeutic strategy used and its long-term results. The size of the sample was not big enough to obtain powerful evidence. A larger sample size and longer follow-up is, therefore, guaranteed.

CONCLUSIONS

In a real-world cohort, changing the neointima of ISR with CB plus DCB vs standard DCB reduces the 5-year rate of TLR although not statistically significant. The benefit of this strategy is evident in the long-term and consistent between ISR after BMS and DES implantation.

FUNDING

None whatsoever.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.A. Linares Vicente: study design, data mining, and analysis and writing of the manuscript. J.R. Ruiz Arroyo: data and critical review of the manuscript. A. Lukic, B. Simó Sánchez, and O. Jiménez Meló: data mining. A. Riaño Ondiviela, P. Morlanes Gracia, and P. Revilla Martí: data mining.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The use of CB to treat ISR with DCB has been associated with better angiographic results although with no impact on the mid-term clinical events. The clinical outcomes of this long-term strategy are still unknown.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The use of CB plus DCB to treat ISR is associated with lower rates of TLR. The benefit of this strategy has been reported in the long-term. This benefit seems to be consistent with both ISR after BMS and DES implantation.

REFERENCES

1. Alfonso F, Byrne RA, Rivero F, Kastrati A. Current Treatment of In-Stent Restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:2659-2673.

2. Giacoppo D, Gargiulo G, Aruta P, Capranzano P, Tamburino C, Capodanno D. Treatment strategies for coronary in-stent restenosis: systematic review and hierarchical Bayesian network meta-analysis of 24 randomised trials and 4880 patients. BMJ. 2015;351:h5392.

3. Siontis GCM, Stefanini GG, Mavridis D, et al. Percutaneous coronary interventional strategies for treatment of in-stent restenosis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2015;386:655-664.

4. Sethi A, Malhotra G, Singh S, Singh PP, Khosla S. Efficacy of Various Percutaneous Interventions for In-Stent Restenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002778.

5. Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:87-165.

6. Rittger H, Waliszewski M, Brachmann J, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Treatment With a Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Versus Balloon Angioplasty. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:1695-700.

7. Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, Cremers B, et al. Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel-coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: the three-year results of the PEPCAD II ISR study. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:926-934.

8. Alfonso F, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, Cuesta J, et al. 3-Year Clinical Follow-Up of the RIBS IV Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:981-991.

9. Alfonso F, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, García del Blanco B, et al. Long-Term Results of Everolimus-Eluting Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Balloons in Patients With Bare-Metal In-Stent Restenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9;1246-1255.

10. Kufner S, Cassese S, Valeskini M, et al. Long-Term Efficacy and Safety of Paclitaxel-Eluting Balloon for the Treatment of Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:877-884.

11. Giacoppo D, Alfonso F, Xu B, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Versus Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation in Patients With Coronary Stent Restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2664-2678.

12. Ahmed JM, Mintz GS, Castagna M, et al. Intravascular ultrasound assessment of the mechanism of lumen enlargement during cutting balloon angioplasty treatment of in-stent restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1032-1034.

13. Albiero R, Silber S, di Mario C, et al. Cutting balloon versus conventional balloon angioplasty for the treatment of in-stent restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:943-949.

14. Park S-J, Kim K-H, Oh I-Y, et al. Comparison of Plain Balloon and Cutting Balloon Angioplasty for the Treatment of Restenosis With Drug-Eluting Stents vs Bare Metal Stents. Circ J. 2010;74:1837-1845.

15. Byrne RA, Joner M, Alfonso F, Kastrati A. Drug-coated balloon therapy in coronary and peripheral artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11:13-23.

16. Radke P, Joner M, Joost A, et al. Vascular effects of paclitaxel following drug-eluting balloon angioplasty in a porcine coronary model: the importance of excipients. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:730-737.

17. Kong J, Hou J, Ma L, et al. Cutting balloon combined with paclitaxel-eluting balloon for treatment of in-stent restenosis. ArchCardiovasc Dis. 2013;106:79-85.

18. Kufner S, Joner M, Schneider S, et al. Neointimal Modification With Scoring Balloon and Efficacy of Drug-Coated Balloon Therapy in Patients With Restenosis in Drug-Eluting Coronary Stents. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:1332-1340.

19. Linares Vicente JA, Ruiz Arroyo JR, Lukic A, et al. 5 year-effectiveness of paclitaxel drug-eluting balloon for coronary in-stent restenosis in a real-world registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;2:92-98.

20. Mehran R, Dangas G, Abizaid AS, et al. Angiographic Patterns of In-Stent Restenosis. Circulation. 1999;100:1872-1878.

21. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials: The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Circulation. 2018;137:2635-2650.

22. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Circulation. 2018;138:e618-e651.

23. Cassese S, Xu B, Habara S, et al. Incidence and predictors of reCurrent restenosis after drug-coated balloon Angioplasty for Restenosis of a drUg-eluting Stent: The ICARUS Cooperation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:620-627.

24. Alfonso F, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, García del Blanco B, et al. Comparison of the Efficacy of Everolimus-Eluting Stents Versus Drug-Eluting Balloons in Patients With In-Stent Restenosis (from the RIBS IV and V Randomized Clinical Trials). Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:546-554.

25. Scheller B, Fontaine T, Mangner N, et al. A novel drug-coated scoring balloon for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: Results from the multi-center randomized controlled PATENT-C first in human trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;88:51-59.

26. Alfonso F, Cuesta J, García del Blanco B, et al. Scoring balloon predilation before bioresorbable vascular scaffold implantation in patients with in-stent restenosis: the RIBS VI 'scoring' study. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:96-104.

27. Aoki J, Nakazawa G, Ando K, et al. Effect of combination of non-slip element balloon and drug-coating balloon for in-stent restenosis lesions (ELEGANT study). J Cardiol. 2019;74:436-442.

28. Habara S, Kadota K, Shimada T, et al. Late Restenosis After Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon Angioplasty Occurs in Patients With Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:14-22.

ABSTRACT

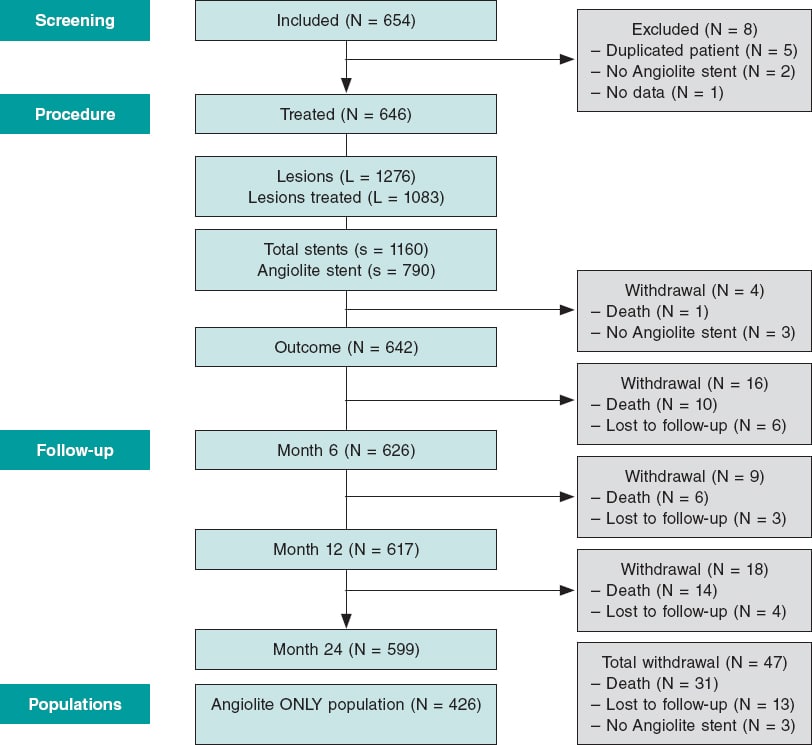

Introduction and objectives: After the positive pre-clinical and clinical results with Angiolite, a cobalt-chromium sirolimus-eluting stent, we decided to analyze its performance in a non-selected, real-world population: the RANGO registry.

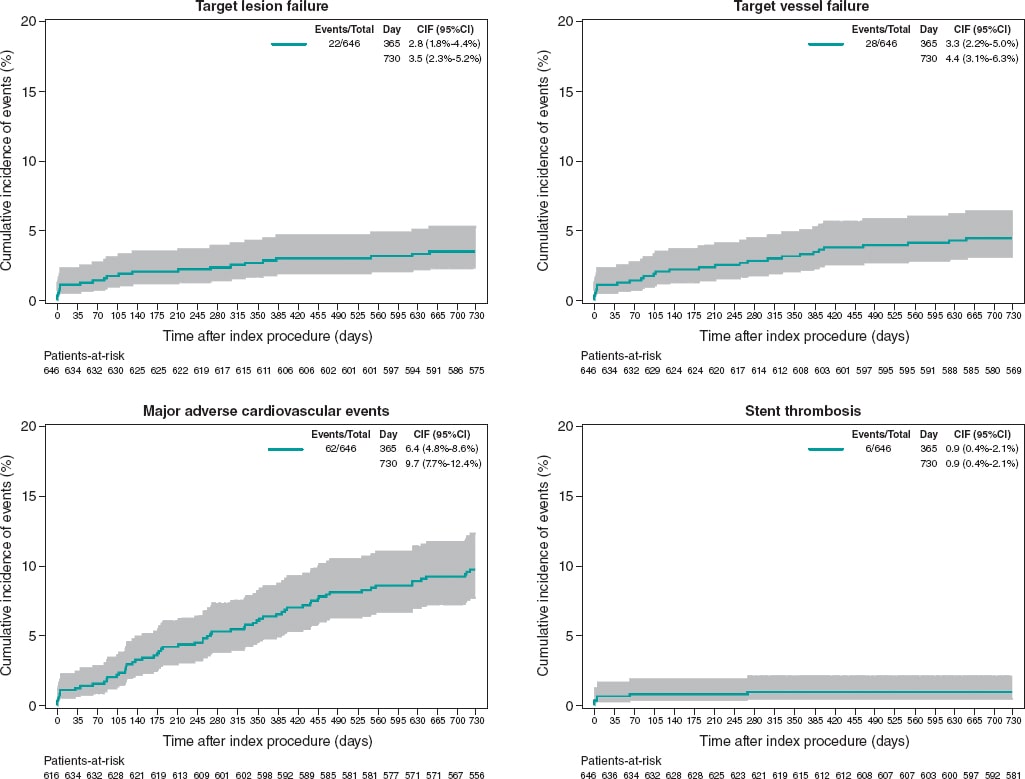

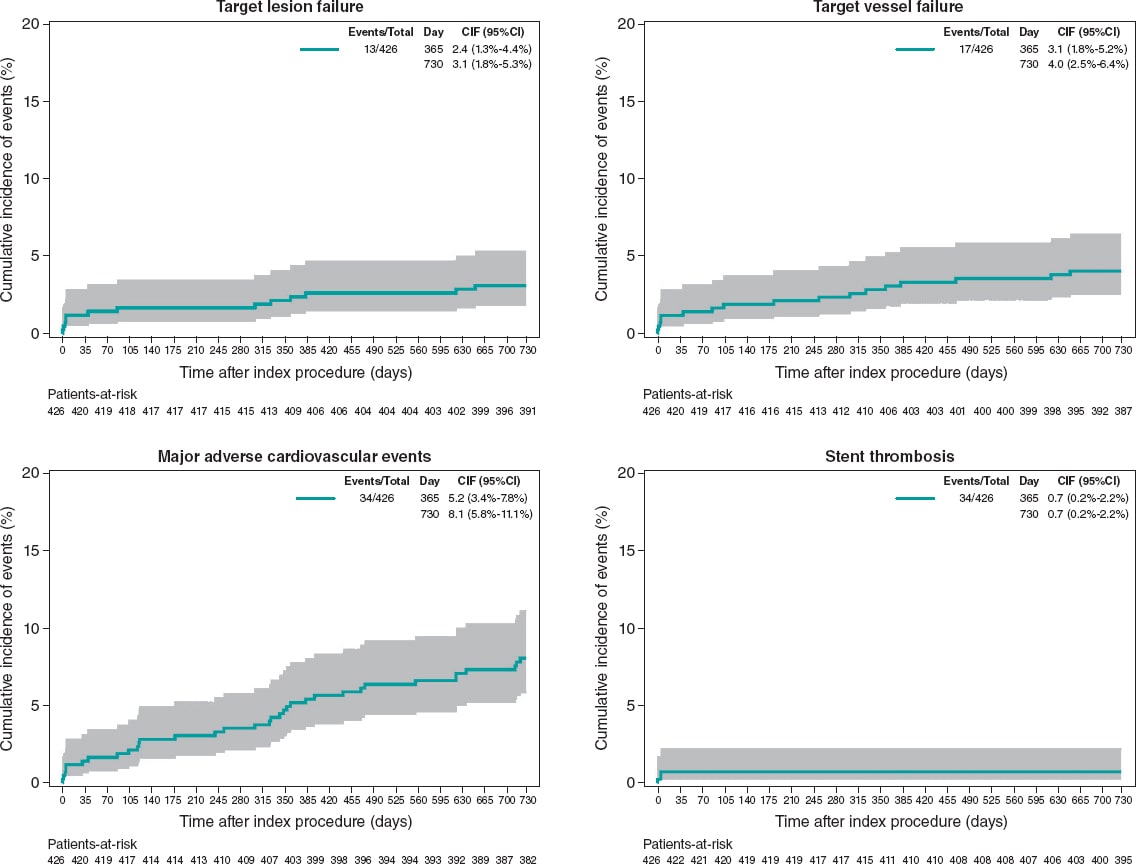

Methods: We conducted an observational, prospective, multicenter registry of patients with different clinical indications. All consecutive patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention with, at least, 1 Angiolite stent and who gave their informed consent were included. The registry primary endpoint was the occurrence of target lesion failure (TLF) at 6, 12, and 24 months defined as cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI) related to target vessel, and clinically driven target lesion revascularization. The secondary endpoints were the individual components of the primary endpoint, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE: all-cause mortality, any MI, or any revascularization), and stent thrombosis. We describe the 2-year clinical results of the RANGO study in the entire population, in those who only received Angiolite stents, and in 2 predefined subgroups: diabetics and patients with small-vessels (≤ 2.5mm).

Results: 646 patients (426 of them only received Angiolite stents) with a high-risk profile were recruited: prevalence of previous MI (18.4%), previous coronary revascularization (23.4%), clinical presentation as ST-segment elevation MI (23.1%), and multivessel disease (47.8%). At the 2-year follow-up, the rates of TLF, MACE, and stent thrombosis were 3.4%, 9.6%, and 0.9%, respectively. Similar results were observed among patients treated with Angiolite stents only: TLF, 3.1%; MACE, 8.0%; thrombosis, 0.7%. The rates were not significantly different for the diabetic (TLF, 3.0%; MACE, 14.1%; thrombosis, 1.0%), and small-vessel subgroups (TLF, 4.3%; MACE, 12.1%; thrombosis, 0%).

Conclusions: In conclusion, the results of this observational registry on the use of Angiolite in a real-world population, including a high-risk population, corroborate the excellent results observed in previous studies, up to a 2-year follow-up. An extended 5-year follow-up is planned to discard the occurrence of late events.

Keywords: Sirolimus-eluting-stent. Durable fluoropolymer. Observational study. Efficacy. Safety. Stent thrombosis.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Para confirmar los resultados observados en análisis preclínicos y clínicos del stent liberador de sirolimus Angiolite se diseñó el registro observacional de vida real RANGO.

Métodos: El registro prospectivo multicéntrico incluyó pacientes con distintas indicaciones clínicas que recibieron al menos 1 stent Angiolite para tratar su enfermedad coronaria y que dieron su consentimiento informado. El objetivo primario fue la incidencia de fracaso del tratamiento de la lesión (FTL) a 6, 12 y 24 meses, definido como muerte de causa cardiaca, infarto de miocardio en relación con el vaso tratado o nueva revascularización de la lesión tratada. Los objetivos secundarios fueron los componentes individuales del objetivo primario y las incidencias de eventos cardiacos mayores (MACE) y de trombosis del stent. Se presentan los resultados del registro RANGO a 2 años en la población global, en los pacientes que recibieron stent Angiolite y en 2 subgrupos predefinidos de diabéticos y vasos pequeños (≤ 2,5 mm).

Resultados: Se seleccionaron 646 pacientes (426 solo recibieron stents Angiolite) con un perfil de riesgo elevado: infarto previo (18,4%), revascularización coronaria previa (23,4%), presentación clínica como infarto agudo con elevación del segmento ST (23,1%) y enfermedad multivaso (47,8%). A los 2 años, la incidencia de FTL en el grupo global fue del 3,4%, la de MACE fue del 9,6% y la de trombosis del stent fue del 0,9%. En el grupo tratado solo con stents Angiolite, los resultados fueron similares (FTL 3,1%, MACE 8,0% y trombosis 0,7%). Los resultados no fueron significativamente diferentes en los diabéticos (FTL 3,0%, MACE 14,1% y trombosis 1,0%) y en los pacientes con vasos pequeños (FTL 4,3%, MACE 12,1% y trombosis 0%).

Conclusiones: Los resultados del registro observacional RANGO a los 2 años en población de vida real con perfil de riesgo elevado confirman los excelentes resultados del stent Angiolite observados en estudios previos. Se plantea un seguimiento clínico a 5 años para descartar eventos muy tardíos.

Palabras clave: Stent liberador de sirolimus. Fluoropolimero estable. Estudio observacional. Eficacia. Seguridad. Trombosis del stent.

Abbreviations

DES: drug-eluting stents. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. TLF: target lesion failure. TLR: target lesion revascularization. TVR: target vessel revascularization.

INTRODUCTION

Drug-eluting stents (DES) are one of the greatest advances in the percutaneous treatment of coronary artery disease. These devices have consistently shown lower rates of revascularization of the treated vessel in a wide range of clinical situations, and have become the treatment of choice.1 However, the risk of late and very late stent thrombosis arose with first-generation DES,2 and, to this date, it is still a matter of concern.3 This phenomenon has been associated with side effects to the drug (impairing the proliferation of new endothelial cells), the polymer, the stent platform or a combination of them on the vessel wall, leading to delayed or incomplete endothelialization, persistent inflammatory reactions, and the development of neo-atherosclerosis. New DES have been developed with superior efficacy in terms of abolishing the need for revascularization, but with the reassurance of much lower rates of stent thrombosis, the most dreadful clinical manifestation of suboptimal vessel healing. The Angiolite stent (iVascular, Spain) is a thin-strut cobalt-chromium sirolimus-eluting stent with biostable coating made of 3 layers: acrylate to ensure adhesion to the metal surface, fluoroacrylate loaded with sirolimus (1.4 µg/mm2), and a top layer of fluoroacrylate for drug release control (> 75% elution within the first month).

The Angiolite stent was initially tested in a pre-clinical model with very promising results,4 with an equivalent antiproliferative response, and a better healing pattern compared to the XIENCE stent (Abbott Vascular, United States). Subsequently, a first-in-human study5 (ANCHOR study) proved a powerful inhibition of neointimal hyperplasia as seen on the OCT: The Angiolite stent efficiently inhibited the proliferative response (vessel area stenosis, 4.4% ± 11.3%), in- stent late lumen loss at 6 months (0.07 mm ± 0.37 mm), and had a low rate of strut malapposition (1.1% ± 6.2%). Finally, the ANGIOLITE study,6 a randomized clinical trial, compared the Angiolite stent to the XIENCE stent in 223 patients (randomization with a 1:1 allocation ratio). In this study, the primary endpoint, the 6-month in-stent late lumen loss, was non-inferior in the Angiolite group (0.04 mm ± 0.39 mm) compared to the XIENCE group (0.08 mm ± 0.38 mm). The stent received the CE marking (Conformité Européenne) for its routine use. Therefore, we designed the present observational, prospective, registry to endorse the previous results in the routine clinical practice, with wider indications for use.

METHODS

Study design

The EPIC02-RANGO study was designed as a prospective, single-arm, multicenter, observational registry for the evaluation of the safety and efficacy profile of the Angiolite stent in unselected patients representative of the routine clinical practice. The study design was approved by all investigators and the sponsor as well. A reference ethics committee approved the protocol and the informed consent forms; local ethics committees were informed that this study would be conducted in their centers in compliance with the national legislation. The study was conducted and monitored by an independent contract research organization. The authors of this original manuscript independently conducted the data final analysis, interpreted the study results, and drafted/wrote this original manuscript. The sponsor was informed on the status of the study and the final results, but had no further participation.

Selection of the study population

To be enrolled in the study, subjects should met all the 3 following inclusion criteria: ≥ 18 years-old; treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with at least 1 Angiolite stent; and have received proper information and signed the corresponding informed consent.

To guarantee a real-world population, non-stringent exclusion criteria were applied. Subjects were only excluded from the study if they met any of the following exclusion criteria: contraindication to dual antiplatelet therapy; established cardiogenic shock; unlikely to complete the scheduled follow-up; or formal refusal to participate in the study.

The PCI (predilatation, invasive imaging, postdilatation, planning, and final performance) was left at the discretion of the operator, and was indicative of the real-world use of the stents. Medical treatment during and after the procedure, including antiplatelet regime and duration, also followed the standard local practices; however, we suggested the investigators to follow the guidelines available on the management of these patients.1,7

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was target lesion failure (TLF) at 6, 12, and 24 months defined as cardiovascular death, target vessel myocardial infarction or clinically driven target lesion revascularization.

-

The secondary endpoints were:

-

– Target vessel failure defined as cardiovascular death, target vessel myocardial infarction or target vessel revascularization.

-

– Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) defined as all-cause mortality, any myocardial infarction or any target vessel revascularization.

-

– Stent thrombosis (definite or probable, as defined by the ARC criteria8).

In all cases, myocardial infarction refers to spontaneous infarction only. Two subgroups were predefined: patients with diabetes, and patients with Angiolite stents placed in small vessels (stent diameter ≤ 2.5 mm).

Sample size calculation

We conducted an exploratory analysis that rendered a population of 640 patients (with an estimated loss to follow-up of 10%). This sample size produces a 2-sided 95% confidence interval with a precision equal to 1.75% when the TLF rate is 4.86%. This value was obtained from the data published from different contemporary stents9-17 (table 1 of the supplementary data).

Table 1. Baseline and clinical characteristics

| Total N = 646 | Angiolite only population N = 426 | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years old) | 66.41 ± 11.93 | 65.72 ± 11.98 |

| Male sex | 495 (76.6%) | 320 (75.1%) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors & history | ||

| Hypertension | 402 (62.2%) | 254 (59.6%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 385 (59.6%) | 251 (58.9%) |

| Diabetes mellitus* | 199 (30.8%) | 119 (27.9%) |

| Current smoker | 182 (28.2%) | 127 (29.8%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 46 (7.1%) | 25 (5.9%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 44 (6.8%) | 23 (5.4%) |

| Previous stroke | 28 (4.3%) | 17 (4.0%) |

| Previous myocardial infarction | 119 (18.4%) | 73 (17.1%) |

| Previous coronary surgery | 20 (3.1%) | 13 (3.1%) |

| Previous PCI | 131 (20.3%) | 78 (18.3%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34 (5.3%) | 20 (4.7%) |

| Heart failure | 46 (7.1%) | 32 (7.5%) |

| Valvular heart disease ≥ grade III | 16 (2.5%) | 7 (1.6%) |

| PCI indication | ||

| NSTEMI | 220 (34.1%) | 141 (33.1%) |

| STEMI | 149 (23.1%) | 112 (26.3%) |

| Stable angina | 120 (18.6%) | 68 (16.0%) |

| Unstable angina (negative biomarkers) | 72 (11.1%) | 51 (12.0%) |

| Silent myocardial ischemia | 32 (5.0%) | 19 (4.5%) |

| Other | 53 (8.2%) | 35 (8.2%) |

|

NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. * Significant differences between patients with the Angiolite stent only vs patients with any stents in addition to the Angiolite, P < .05. Data are expressed as no. (%) or mean ± standard deviation. |

||

Population analysis

The primary safety and efficacy analysis considered all patients who received the Angiolite stent only except for those who withdrew their consent. The secondary analysis was performed on all patients included in the study who received, at least, 1 Angiolite stent plus another different stent except for those who withdrew their consent.

Clinical events committee

An independent data and safety monitoring board reviewed the cumulative safety data to safeguard the well-being of the participants. All events were remotely monitored by a contract research organization. The clinical events committee reviewed, adjudicated, and classified all adverse events. The 5 members of the clinical events committee were not affiliated to the centers that participated in the study.

A total of 90 random patient audits (14% of the global population) were conducted at 4 centers, including the top 3 recruiters. The result of these audits detected 9 unreported events, most of them corresponded to scheduled procedures that required admission (non-cardiac surgeries and 2 scheduled PCI cases). None of the events associated with these audits corresponded to events classified as primary or secondary endpoints.

Descriptive statistics

All continuous variables were summarized using the following descriptive statistics: n (based on the number of recorded data values for each parameter), mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence interval for the mean, median, interquartile range [Q1, Q3], maximum, and minimum. The frequency and percentages (based on the number of recorded data values for each parameter) of the observed values are reported for all categorical measures. In general, all data are listed, and sorted by study site, and subject.

Statistical methods

Regarding the continuous variables, results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Variables were compared using an independent t test or the Mann-Whitney test, when applicable. Categorical variables are expressed as counts and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Variables were compared between patients with only the Angiolite stent versus patients with other stents in addition to the Angiolite one. The clinical variables at 6, 12, and 24 months were expressed as counts and percentages. Time-to-event hazard curves were expressed as Kaplan-Meier estimates.

These methods were applied for the entire cohort and the 2 predefined subgroups, when appropriate: patients with diabetes, and patients with small vessel lesions (stent diameter ≤ 2.5 mm).

The statistical software SAS Version 9.4 was used for all statistical analyses, listings, tabulations, and figures.

RESULTS