Article

Ischemic heart disease and acute cardiac care

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:21-25

Access to side branches with a sharply angulated origin: usefulness of a specific wire for chronic occlusions

Acceso a ramas laterales con origen muy angulado: utilidad de una guía específica de oclusión crónica

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de Cabueñes, Gijón, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The use of coronary physiology is essential to guide revascularization in patients with stable coronary artery disease. However, some patients without significant angiographic coronary artery disease will experience cardiovascular events at the follow-up. This study aims to determine the prognostic value of the global plaque volume (GPV) in patients with stable coronary artery disease without functionally significant lesions at a 5-year follow-up.

Methods: We conducted a multicenter, observational, and retrospective cohort study with a 5-year follow-up. A total of 277 patients without significant coronary artery disease treated with coronary angiography in 2015 due to suspected stable coronary artery disease were included in the study. The 3 coronary territories were assessed using quantitative flow ratio, calculating the GPV by determining the difference between the luminal volume and the vessel theoretical reference volume.

Results: The mean GPV was 170.5 mm3. A total of 116 patients (42.7%) experienced major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at the follow-up, including cardiac death (11%), myocardial infarction (2.6%), and unexpected hospital admissions (38.1%). Patients with MACE had a significantly higher GPV (231.6 mm3 vs 111.8 mm3; P < .001). The optimal GPV cut-off point for predicting events was 44 mm3. Furthermore, in the multivariate analysis conducted, plaque volume, diabetes, hypertension, age, dyslipidemia, smoking, age, and GPV > 44 mm3 turned out to be independent predictors of MACE.

Conclusions: GPV, calculated from the three-dimensional reconstruction of the coronary tree, is an independent predictor of events in patients with stable coronary artery disease without significant lesions. A GPV > 44 mm3 is an optimal cut-off point for predicting events.

Keywords: Coronary artery disease. Coronary atherosclerosis. Coronary angiography. Global plaque volume. Coronary physiology. Quantitative flow ratio.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La fisiología coronaria es fundamental para guiar la revascularización en los pacientes con enfermedad coronaria estable. Sin embargo, algunos pacientes sin enfermedad coronaria significativa en la angiografía presentarán eventos cardiovasculares posteriormente. Este estudio pretende determinar el valor pronóstico del volumen global de placa (VGP) en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria estable sin lesiones funcionalmente significativas durante 5 años de seguimiento.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional multicéntrico de cohortes retrospectivo con seguimiento a 5 años, que incluyó 277 pacientes sin enfermedad coronaria significativa intervenidos mediante coronariografía en 2015 por sospecha de enfermedad coronaria estable. Se evaluaron los 3 territorios coronarios mediante el cociente de flujo cuantitativo, calculando el VGP como la diferencia entre el volumen luminal y el volumen teórico de referencia del vaso.

Resultados: El VGP medio fue de 170,5 mm3. Durante el seguimiento, 116 pacientes (42,7%) presentaron eventos cardiovasculares mayores (MACE), que incluyeron muerte de causa cardiaca (11%), infarto de miocardio (2,6%) y hospitalizaciones no programadas (38,1%). Los pacientes con MACE tenían un VGP significativamente mayor (231,6 frente a 111,8 mm3, p < 0,001). El punto de corte óptimo del VGP para predecir eventos fue de 44 mm3. En el análisis multivariado, que consideró volumen de placa, diabetes, hipertensión, edad, dislipemia y tabaquismo, la edad y un VGP > 44 mm3 fueron predictores independientes de MACE.

Conclusiones: El VGP calculado mediante reconstrucción tridimensional del árbol coronario es un predictor independiente de eventos en pacientes con enfermedad coronaria estable sin lesiones significativas. Un VGP > 44 mm3 es el punto de corte óptimo para predecir eventos.

Palabras clave: Enfermedad coronaria. Ateroesclerosis coronaria. Angiografía coronaria. Volumen global de placa. Fisiología coronaria. Cociente de flujo cuantitativo.

Abbreviations

GPV: global plaque volume. MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. QFR: quantitative flow ratio. ROC: receiver operating characteristic curve.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease is the leading cause of mortality worldwide.1 Despite the safety involved in deferring invasive treatment in patients with stable coronary artery disease without functionally significant lesions,2 a percentage of patients experience cardiovascular events at the long-term follow-up.3 It has been reported that cardiovascular events not only depend on the degree of coronary obstruction assessed by intracoronary physiology4-5 but also on the global atherosclerotic burden and its vulnerability assessed by intracoronary imaging modalities.6-8

The new era of coronary physiology is based on predicting fractional flow reserve by reconstructing the coronary tree using angiography and computational fluid dynamics.9-10 Estimating quantitative flow ratio (QFR) is the most validated method of the ones currently available.

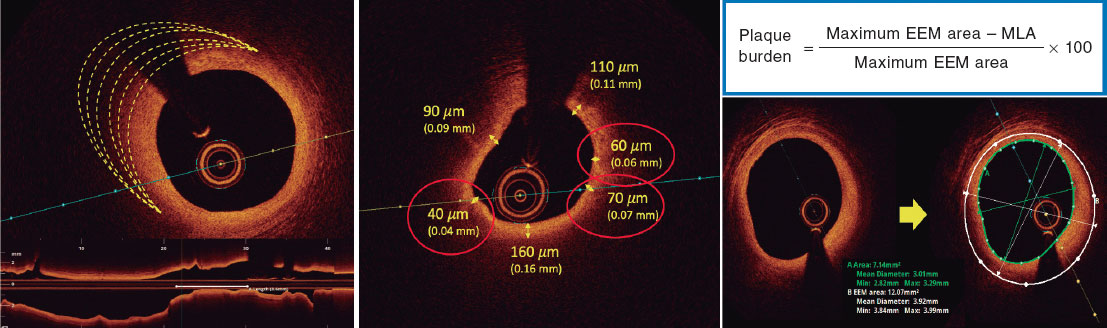

QFR—which predicts fractional flow reserve10-11—has proven to be a better tool than angiography alone to guide the need for lesion revascularization12 and shown long-term prognostic value13. Furthermore, it provides quantitative information out of the 3D reconstruction of the coronary tree, including minimum diameter and area, reference diameters, luminal volume, and atherosclerotic plaque volume in the studied vessel. However, the prognostic value of this quantitative analysis has not been sufficiently studied.

The main aim of this study was to determine the prognostic value of global plaque volume (GPV) in patients with stable coronary artery disease without functionally significant lesions at a 5-year follow-up.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective observational study on a cohort of patients from 6 tertiary referral centers.

Study population

Patients who underwent coronary angiography from January through December 2015 for suspected stable coronary artery disease were included. Each participant center retrospectively enrolled all patients who underwent coronary angiography for suspected stable coronary artery disease and met the inclusion criteria. Patients with chronic total coronary occlusions, prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery, or inadequate angiographic quality for analysis were excluded. Additionally, patients whose angiographic analysis revealed a positive QFR study (< 0.80) in any coronary territory were excluded. The principal investigator conducted a retrospective follow-up at each center within the next 5 years following the index procedure. Baseline and procedural characteristics, and events at the follow-up were collected by local investigators. The study fully complied the good clinical practice principles and regulations set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki for research with human subjects. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the reference hospital (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid) and the institutional review boards, including informed consent obtained from participants or, alternatively, approval for retrospective data analysis under ethical committee supervision.

Angiographic analysis

A blinded angiographic analysis of diagnostic coronary angiograms was performed by trained analysts at a centralized imaging unit (Icicorelab, Valladolid) using specialized software (QAngio XA 3D QFR, Medis Medical Imaging System, The Netherlands). A 3D reconstruction of the 3 major coronary vessels was performed using 2 different projections with > 25° of separation. For the right and left circumflex coronary arteries, the proximal marker was manually placed at the vessel ostium, while for the left anterior descending coronary artery, it was placed at the left main coronary artery ostium. The distal marker was placed at the end of the coronary artery. Plaque volume was estimated by calculating the difference between the theoretical reference vessel volume in the absence of atherosclerotic disease and the estimated vessel volume in angiography using QFR software via quantitative analysis. Reference diameters, minimum diameter, and minimum area were obtained for each vessel. Considering contrast flow through the coronary tree, QFR was calculated according to FAVOR II standards for the physiological significance of coronary lesions. Patients with functionally significant disease (QFR < 0.80) were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as totals and percentages, and continuous ones as means and standard deviations. GPV was estimated as the sum of plaque volume across 3 coronary territories.

The primary endpoint—major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE)—was a composite of cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, or all-cause unplanned hospital admission.

An optimal GPV cutoff as a predictor of MACE was determined using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve as the value with the maximum Youden index. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to calculate the odds ratio and 95% confidence interval as independent predictors for MACE. Variables with P < .20 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model as covariates.

Event-free survival was compared using Kaplan-Meier and Mantel-Haenszel analyses. All probability values were two-tailed, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata (16.1, StataCorp, College Station, United States).

RESULTS

Descriptive population analysis

A total of 803 patients were evaluated for inclusion in the registry, 122 of whom (15.2%) were excluded due to chronic occlusions in ≥ 1 coronary territory, 17 (2.12%) due to previous surgical myocardial revascularization, and 159 (19.2%) due to inadequate angiographic analysis in, at least, 1 coronary territory. Among the remaining patients, 228 (45.1%) had significant coronary artery disease (QFR < 0.80) in, at least, 1 coronary territory, which left a final cohort of 277 patients. Patient flowchart is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the patient selection process for inclusion in the study. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; QFR, quantitative flow ratio.

The mean age of the population was 65.8 years (most were hypertensive [74.4%] men [66.1%]). Table 1 illustrates the baseline characteristics of the population. The median follow-up was 69 months, during which time 5 patients were lost to follow-up.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the included population

| Variable | n/mean | Proportion/SD |

|---|---|---|

| Female Sex | 94 | 33.9% |

| Hypertension | 206 | 74.3% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 106 | 38.2% |

| Dyslipidemia | 188 | 67.9% |

| Smoking | 121 | 43.7% |

| Chronic kidney disease | 21 | 7.6% |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 14 | 5.1% |

| Previous ischemic heart disease | 105 | 37.9% |

| Age (years) | 65.8 | 12.2 |

| Weight (kg) | 78.0 | 15.0 |

| Height (cm) | 156.2 | 36.8 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 57.4 | 9.3 |

|

SD, standard deviation. |

||

Angiographic analysis

Mean plaque volume in the study population was 170.5 mm3 (± 16.5); mean QFR was 0.95. Table 2 illustrates the overall means from the angiographic analysis according to the coronary territory studied. Plaque volume was independently analyzed for each coronary territory and was significantly higher in the right (243 mm3) vs the left anterior descending (161.4 mm3) and left circumflex coronary arteries (172.9 mm3). Data on this analysis by coronary territories are shown in table 1 and figure 1 of the supplementary data.

Table 2. Characteristics of the angiographic analysis performed in the 3 coronary territories using quantitative flow ratio

| Variable | Mean | SD | 95%CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| QFR | 0.95 | 0.37 | 0.95-0.96 |

| Length | 76.99 | 13.21 | 75.22-78.77 |

| Proximal diameter | 3.18 | 0.47 | 3.11-3.24 |

| Distal diameter | 1.99 | 0.34 | 1.95-2.04 |

| Reference diameter | 2.69 | 0.42 | 2.58-2.70 |

| Minimum lumen diameter | 1.76 | 0.34 | 1.72-1.81 |

| Percent diameter stenosis | 33.81 | 6.44 | 32.95-34.68 |

| Stenosis area (%) | 38.72 | 9.59 | 37.43-40.01 |

| Minimum lumen area | 3.53 | 1.30 | 3.35-3.70 |

| Lumen volume | 295.5 | 242.25 | 262.83-328.12 |

| Plaque volume | 170.54 | 240.24 | 138.17-202.91 |

|

SD, standard deviation; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; QFR, quantitative flow ratio. |

|||

Prognostic value of global plaque volume

The primary event (MACE) occurred in 116 patients, which amounts to 42.7% of the cohort at the follow-up. Among these patients, 11% died, 2.6% suffered an acute myocardial infarction, and 38.1% required unplanned hospitalization. Patients who developed MACE had a significantly higher GPV (231.6 vs 111.8 mm3; P < .001), as well as those with a higher mortality rate (255.2 mm3 vs 154.3 mm3; P = .04) or unplanned hospitalizations (235.0 mm3 vs 125.4 mm3; P < .001). However, there were no significant differences in patients who experienced acute myocardial infarction (235.1 mm3 vs 169.3 mm3; P = .51).

The optimal GPV cutoff to predict events was set at 44 mm3 based on ROC curve analysis (sensitivity, 64%; specificity, 65.8%; LR+, 1.9; LR–, 0.6).

Table 3 illustrates the study of the main determinants of the primary event. Variables with a significance level of P < .10 were included in the multivariate analysis. In the final model, age and GPV were independent predictors. A GPV > 44 mm3 was associated with a 2.8-fold higher risk of events at the follow-up (figure 2).

Table 3. Uni- and multivariate analysis of determinants of the main event

| Determinants of the main event | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95%CI | OR | 95%CI | |

| Sex, female | 1.09 | 0.66-1.81 | ||

| Age* | 1.03 | 1.01-1.10 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.07 |

| Hypertension* | 2.26 | 1.26-4.07 | 1.70 | 0.82-3.53 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.18 | 0.72-1.93 | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 1.04 | 0.62-1.73 | ||

| Smoking | 1.01 | 0.72-1.42 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease | 1.00 | 0.41-2.46 | ||

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1.37 | 0.47-4.01 | ||

| Previous ischemic heart disease* | 1.52 | 0.93-2.50 | 1.46 | 0.80-2.68 |

| LVEF | 0.98 | 0.96-1.01 | ||

| GPV (> 44 mm3)* | 1.93 | 1.17-3.18 | 2.80 | 1.51-5.21 |

| Reference vessel diameter* | 2.20 | 1.12-4.35 | 1.62 | 0.75-3.50 |

|

* P values < .10 were included in the multivariate analysis. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; GPV, global plaque volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; OR, odds ratio. |

||||

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier curve showing the patients’ event-free survival based on their global plaque volume.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that GPV quantification emerged as an independent prognostic factor in patients without functionally significant coronary artery disease, which demonstrated that those with a higher GPV experienced more events at the follow-up. The optimal GPV cutoff for event prediction was set at 44 mm3. This study emphasizes the importance of anatomically characterizing coronary arteries without significant lesions.

Despite the absence of significant coronary artery obstructions, some patients still experience events during follow-up.14 In patients with a negative QFR functional study, it has been reported that the 5-year rate of events—cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction—is 11.6%,3 similar to our findings, where mortality rate was 11% and acute myocardial infarction occurred in 2.6% of patients. Determining the difference between the actual vessel diameter and the estimated diameter obtained through 3D reconstruction from QFR-based angiography has been used in other studies.15 This estimation—previously derived from coronary computed tomography16-17—has demonstrated the prognostic significance of plaque volume differences between normal and non-obstructive coronary arteries. These differences have also been confirmed using invasive imaging modalities such as intravascular ultrasound.18 Although angiography-derived percent luminal stenosis shows poor concordance with myocardial ischemia,19 a greater degree of coronary stenosis (percent diameter stenosis > 50%) is associated with a higher event rate at the 2-year follow-up in patients without functionally significant coronary lesions.20 The present study takes a step further into the minimally invasive characterization of atherosclerotic burden using easy-to-implement 3D coronary tree reconstruction technology as an independent prognostic factor in patients without functionally significant coronary lesions. In this regard, this study is consistent with recent studies which demonstrated that subclinical atherosclerosis burden—measured by vascular ultrasound for carotid plaque quantification and computed tomography for coronary calcium scoring—in asymptomatic individuals is independently associated with all-cause mortality.21

Based on these findings, GPV measurement enables the identification of patients who, despite having no significant coronary lesions, are at risk of developing events within the next 5 years, allowing for intensified treatment and cardiovascular risk factor control. However, this study has limitations, including its retrospective design for patient inclusion and recruitment, the use of indirect methods—such as QFR—to estimate plaque volume, and the inability of this method to describe plaque characteristics, or potential lipid plaque vulnerability. Of note, the estimated plaque volume in each coronary artery was not specifically correlated with events in that territory but rather with overall adverse cardiovascular events. Therefore, further studies are needed to confirm or refute this hypothesis.

CONCLUSIONS

Plaque volume, calculated by 3D coronary tree reconstruction, is an independent predictor of events in patients with suspected stable ischemic heart disease without significant coronary artery disease. The optimal GPV cutoff for event prediction is 44 mm3.

FUNDING

C. Cortés received funding through the Río Hortega contract CM22/00168 and Miguel Servet CP24/00128 from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Madrid, Spain).

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The present study was conducted in full compliance with clinical practice guidelines set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki for clinical research and was approved by the ethics committees of the reference hospital (Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid) and other participant centers. Possible sex- and gender-related biases were also considered.

DECLARATION ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the writing of this text.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

C. Cortés and J. Ruiz-Ruiz participated in study design, data analysis, manuscript drafting, and critical review. C. Fernández and M. García participated in data collection and result analysis. F. Rivero and R. López-Palop assisted in data collection. S. Blasco and A. Freites contributed to statistical analysis. L. Scorpiglione and M. Rosario Ortas Nadal collaborated in data interpretation. O. Jiménez participated in manuscript preparation and initial review. J.A. San Román Calvar and I.J. Amat-Santos conducted the final review and approved the version for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Global plaque volume has already been identified as an independent risk factor for the occurrence of new coronary events at the follow-up of patients without significant coronary lesions. However, this risk was determined using coronary computed tomography and imaging modalities such as intravascular ultrasound.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This article is the first study to only use the patient’s own angiography and minimally invasive coronary physiology techniques, such as quantitative flow ratio to determine plaque volume and its relationship with major cardiovascular events at a 5-year follow-up in patients without significant coronary artery disease. This approach simplifies the implementation of this technique and enhances prevention strategies for patients at higher risk of cardiovascular events.

REFERENCES

1. Laslett LJ, Alagona PJ, Clark BA 3rd, et al. The worldwide environment of cardiovascular disease:prevalence, diagnosis, therapy, and policy issues:a report from the American College of Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:S1-49.

2. Zimmermann FM, Ferrara A, Johnson NP, et al. Deferral vs. of percutaneous coronary intervention of functionally non-significant coronary stenosis:15-year follow-up of the DEFER trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3182-3188.

3. Kuramitsu S, Matsuo H, Shinozaki T, et al. Five-Year Outcomes After Fractional Flow Reserve-Based Deferral of Revascularization in Chronic Coronary Syndrome:Final Results From the J-CONFIRM Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:E011387.

4. De Bruyne B, Pijls NHJ, Kalesan B, et al. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991-1001.

5. Ciccarelli G, Barbato E, Toth GG, et al. Angiography versus hemodynamics to predict the natural history of coronary stenoses:Fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation 2 substudy. Circulation. 2018;137:1475-1485.

6. Mortensen MB, Dzaye O, Steffensen FH, et al. Impact of Plaque Burden Versus Stenosis on Ischemic Events in Patients With Coronary Atherosclerosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2803-2813.

7. Shan P, Mintz GS, McPherson JA, et al. Usefulness of Coronary Atheroma Burden to Predict Cardiovascular Events in Patients Presenting With Acute Coronary Syndromes (from the PROSPECT Study). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1672-1677.

8. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, et al. Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome:the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:383-391.

9. Tu S, Westra J, Yang J, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Fast Computational Approaches to Derive Fractional Flow Reserve From Diagnostic Coronary Angiography:The International Multicenter FAVOR Pilot Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2024-2035.

10. Westra J, Andersen BK, Campo G, et al. Diagnostic Performance of In?Procedure Angiography?Derived Quantitative Flow Reserve Compared to Pressure?Derived Fractional Flow Reserve:The FAVOR II Europe?Japan Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:009603.

11. Cortés C, Carrasco-Moraleja M, Aparisi A, et al. Quantitative flow ratio —Meta-analysis and systematic review. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:807-814.

12. Xu B, Tu S, Song L, et al. Angiographic quantitative flow ratio-guided coronary intervention (FAVOR III China):a multicentre, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;398:2149-2159.

13. Cortés C, Fernández-Corredoira PM, Liu L, et al. Long-term prognostic value of quantitative-flow-ratio-concordant revascularization in stable coronary artery disease. Int J Cardiol. 2023;389:131176.

14. Wang TKM, Oh THT, Samaranayake CB, et al. The utility of a “non-significant“coronary angiogram. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:1465-1472.

15. Kolozsvári R, Tar B, Lugosi P, et al. Plaque volume derived from three-dimensional reconstruction of coronary angiography predicts the fractional flow reserve. Int J Cardiol. 2012;160:140-144.

16. Huang FY, Huang BT, Lv WY, et al. The Prognosis of Patients With Nonobstructive Coronary Artery Disease Versus Normal Arteries Determined by Invasive Coronary Angiography or Computed Tomography Coronary Angiography:A Systematic Review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:3117.

17. Khajouei AS, Adibi A, Maghsodi Z, Nejati M, Behjati M. Prognostic value of normal and non-obstructive coronary artery disease based on CT angiography findings. A 12 month follow up study. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11:318-321.

18. Lee JM, Choi KH, Koo BK, et al. Prognostic Implications of Plaque Characteristics and Stenosis Severity in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2413-2424.

19. Tebaldi M, Biscaglia S, Fineschi M, et al. Evolving Routine Standards in Invasive Hemodynamic Assessment of Coronary Stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1482-1491.

20. Ciccarelli G, Barbato E, Toth GG, et al. Angiography versus hemodynamics to predict the natural history of coronary stenoses:Fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation 2 substudy. Circulation. 2018;137:1475-1485.

21. Fuster V, García-Álvarez A, Devesa A, et al. Influence of Subclinical Atherosclerosis Burden and Progression on Mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:1391-1403.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: There is limited data on the impact of the culprit vessel on very long-term outcomes after ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The aim was to analyze the impact of the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) as the culprit vessel of STEMI on very long-term outcomes.

Methods: We analyzed patients included in the EXAMINATION-EXTEND study (NCT04462315) treated with everolimus-eluting stents or bare-metal stents after STEMI (1498 patients) and stratified according to the culprit vessel (LAD vs other vessels). The primary endpoint was the patient-oriented composite endpoint (POCE), including all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction (MI) or revascularization at 10 years. Secondary endpoints were individual components of POCE, device-oriented composite endpoint and its individual components and stent thrombosis. We performed landmark analyses at 1 and 5 years. All endpoints were adjusted with multivariable Cox regression models.

Results: The LAD was the culprit vessel in 631 (42%) out of 1498 patients. The LAD-STEMI group had more smokers, advanced Killip class and worse left ventricular ejection fraction. Conversely, non-LAD-STEMI group showed more peripheral vascular disease, previous MI, or previous PCI. At 10 years, no differences were observed between groups regarding POCE (34.9% vs 35.4%; adjusted hazard ratio [HR], 0.95; 95% confidence interval [95%CI], 0.79-1.13; P = .56) or other endpoints. The all-cause mortality rate was higher in the LAD-STEMI group (P = .041) at 1-year.

Conclusions: In a contemporary cohort of STEMI patients, there were no differences in POCE between LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel and other vessels at 10 years follow-up. However, all-cause mortality was more common in the LAD-STEMI group within the first year after STEMI.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction. STEMI. Angiography. Coronary. Percutaneous coronary intervention.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Existen datos limitados sobre el impacto a muy largo plazo del vaso culpable después de un infarto de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST). El objetivo fue analizar el efecto de la arteria descendente anterior (DA) como vaso culpable en el IAMCEST en los resultados a muy largo plazo.

Métodos: Se analizaron los pacientes incluidos en el estudio EXAMINATION-EXTEND (NCT04462315) que recibieron stents liberadores de everolimus o stents metálicos después de un IAMCEST (1.498 pacientes) y se estratificaron según el vaso culpable (DA frente a otros vasos). El objetivo primario fue el objetivo combinado orientado al paciente (POCE) que incluyó muerte por cualquier causa, infarto agudo de miocardio (IAM) o revascularización a los 10 años. Los objetivos secundarios fueron los componentes individuales del POCE, el evento compuesto orientado al dispositivo y sus componentes individuales, así como la trombosis del stent. Se realizaron análisis de puntos de referencia a 1 y 5 años. Todos los objetivos fueron ajustados mediante modelos de regresión de Cox multivariantes.

Resultados: De los 1.498 pacientes, la DA fue el vaso culpable en 631 (42%). El grupo IAMCEST-DA mostró mayor proporción de fumadores, una clase Killip más avanzada y una peor fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo. En cambio, el grupo sin IAMCEST-DA mostró mayor prevalencia de enfermedad vascular periférica, IAM previo y angioplastia coronaria previa. A los 10 años no se observaron diferencias entre los grupos para el POCE (34,9 frente a 35,4%; hazard ratio, 0,95; intervalo de confianza del 95%, 0,79-1,13; p = 0,56) ni para otros objetivos. Hubo una mayor mortalidad por cualquier causa en el grupo IAMCEST-DA (p = 0,041) al primer año.

Conclusiones: En una cohorte contemporánea de pacientes con IAMCEST no hubo diferencias en cuanto al POCE entre la DA como vaso culpable en el IAMCEST y los otros vasos a los 10 años de seguimiento. Sin embargo, en el primer año después del IAMCEST, la mortalidad por cualquier causa fue más común en el grupo IAMCEST-DA.

Palabras clave: Infarto agudo de miocardio. IAMCEST. Angiografía. Coronaria. Intervención coronaria percutánea.

Abbreviations

LAD: left anterior descending coronary artery. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. MI: myocardial infarction. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. POCE: patient-oriented composite endpoint. STEMI: ST−segment elevation myocardial infarction.

INTRODUCTION

Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is the first-line therapy in patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).1 The STEMI-related culprit vessel is usually considered as one of the most important prognostic factors in STEMI patients.2,3 This assumption comes from previous studies –conducted in the pre-reperfusion or thrombolysis era– which showed that left anterior descending artery (LAD)-related STEMIs were associated with worse clinical outcomes compared with right coronary (RCA) and left circumflex artery (LCX)-related lesions.4-9

However, in the contemporary era of primary PCI there are limited data about the prognostic impact of LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel especially in a very long follow-up.10,11

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the impact of the LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel on very long-term clinical outcomes in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI enrolled in the EXAMINATION-EXTEND study (10-year follow-up of the EXAMINATION trial).

METHODS

Study design and patients

The EXAMINATION trial (NCT00828087) was an all-comer, multicenter, prospective, 1:1 randomized, 2-arm, single-blind, controlled trial conducted at 12 centers across 3 countries to assess the superiority of EES (Xience V) vs BMS (Multilink Vision, Abbott Vascular) in STEMI patients regarding the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, any myocardial infarction, and any revascularization at 1 year. The study had broad inclusion criteria and few exclusion criteria to ensure an all-comer STEMI population representative of the routine clinical practice. The study outcomes have been reported up to the year 5.12,13 After that, it was reinitiated as the EXAMINATION- EXTEND study to evaluate patient- and device-oriented composite endpoints at 10 years. The latter is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04462315) as an investigator-driven extension of follow-up of the EXAMINATION trial. An independent study monitor (ADKNOMA, Barcelona, Spain) verified the adequacy of the extended follow-up and events reported. All events were adjudicated and classified by an independent event adjudication committee blinded to the therapy groups (Barcicore Lab, Barcelona, Spain). The 10-year primary endpoint results of the EXAMINATION-EXTEND study have been previously published.14 For the aim of this study, baseline, procedural characteristics and outcomes were stratified according to the STEMI-related culprit vessel (LAD vs others). All centers participating in the EXAMINATION trial received the approval of their Medical Ethics Committee, and all enrolled patients who had already signed their written informed consent forms. Medical ethics committee approval for EXAMINATION- EXTEND was granted at the institutions of the principal investigators (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain), and the requirement to obtain informed consent to gather information on 10- year events was waived. The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study endpoints

The primary endpoint of this study was the patient-oriented composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, any myocardial infarction, or any revascularization at 10 years. Secondary endpoints were each individual components of the primary endpoint, device-oriented composite endpoint (cardiac death, target-vessel myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization), its individual components and stent thrombosis. Detailed descriptions of the study endpoints and definitions have been published previously.15

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as median (interquartile range; IQR), and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies (percentages).

Baseline clinical, angiographic, and procedural characteristics were compared between the groups stratified by the STEMI-related artery (LAD vs other vessels) using the Wilcoxon rank sum test, the chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate.

Time-to-event curves for POCE and all-cause death were plotted using the one minus the Kaplan-Meier estimate and the cumulative incidence function for other outcomes. The incidence of events at the follow-up was compared between groups using log-rank or Grey’s test. Landmark analyses were also performed, setting landmark points at 1 and 5 years.

The association between LAD as a STEMI-related culprit vessel and events was analyzed in univariable and multivariable cause-specific Cox regression models. Covariates were added to the multivariable model in 2 blocks. The first model included all clinically relevant baseline characteristics variables with P < .1 in the between-groups comparison (LAD vs other vessels), i.e., sex, smoking status, peripheral vascular disease, previous PCI, previous CABG, previous MI, and Killip class. The second model (expanded adjustment) included both the baseline characteristics and the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at discharge.

Two-tailed P-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R Core Team (2022). R: a language for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria) with the following packages: survival, tidycmprsk, jskm, and gtsummary.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

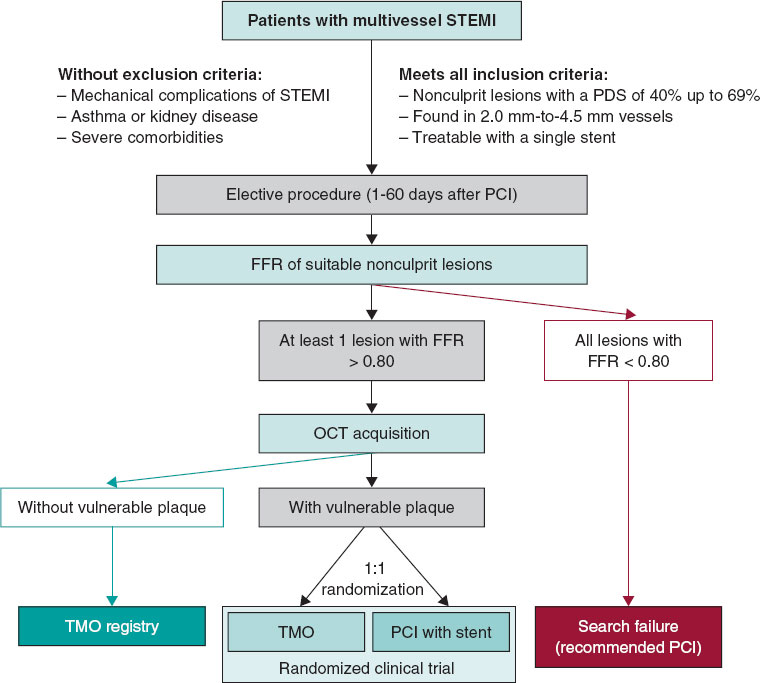

In 631 (42%) out of the 1498 STEMI patients included in the EXAMINATION EXTEND trial, the LAD was the culprit vessel (LAD-STEMI group), whereas in 867 patients (58%) it was not (non- LAD-STEMI group). Patients’ inclusion flowchart is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Study flowchart. A total of 1498 patients were initially recruited. At 10 years, clinical follow-up was obtained in 95.2% of the patients. LAD, left anterior descending artery; STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

LAD-STEMI group had a higher incidence of active smokers, advanced Killip class and more depressed LVEF vs the non-LAD-STEMI group, which, however, exhibited a higher incidence of peripheral vascular disease, previous MI and previous PCI (table 1). Also, although non-statistically significant, the frequency of late comers and bailout PCI was numerically higher in the LAD-STEMI group.

Table 1. Baseline clinical characteristics

| Clinical characteristics | Overall (N = 1498)a | LAD-STEMI (N = 631)a | Non-LAD-STEMI (N = 867)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61 [51-71] | 61 [51-71] | 61 [51-70] | .778 | |

| 1,244 (83%) | 512 (81%) | 732 (84%) | .094 | |

| 415 (28%) | 197 (31%) | 218 (25%) | .009 | |

| 655 (44%) | 268 (43%) | 387 (45%) | .419 | |

| 725 (48%) | 307 (49%) | 418 (48%) | .843 | |

| 55 (3.7%) | 14 (2.2%) | 41 (4.7%) | .011 | |

| 31 (2.1%) | 14 (2.2%) | 17 (2.0%) | .726 | |

| 80 (5.3%) | 23 (3.7%) | 57 (6.6%) | .013 | |

| 61 (4.1%) | 18 (2.9%) | 43 (5.0%) | .042 | |

| 10 (0.7%) | 1 (0.2%) | 9 (1.0%) | .052 | |

| .126 | ||||

| 1,268 (85%) | 520 (82%) | 748 (86%) | ||

| 98 (6.5%) | 51 (8.1%) | 47 (5.4%) | ||

| 34 (2.3%) | 14 (2.2%) | 20 (2.3%) | ||

| 97 (6.5%) | 46 (7.3%) | 51 (5.9%) | ||

| < .001 | ||||

| I | 1,337 (90%) | 525 (83%) | 812 (94%) | |

| II | 115 (7.7%) | 76 (12%) | 39 (4.5%) | |

| III | 23 (1.5%) | 20 (3.2%) | 3 (0.3%) | |

| IV | 18 (1.2%) | 8 (1.3%) | 10 (1.2%) | |

| 52 (45, 58) | 46 [40-55] | 55 [50-60] | < .001 | |

| 1.38 (0.70, 3.00) | 1.27 [0.67-3.00] | 1.47 [0.75-3.00] | .353 | |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention. a>Median [interquartile range] or frequency (%). bWilcoxon rank sum test; Pearson’s chi-squared test; Fisher’s exact test. |

||||

Regarding procedural data, LAD-STEMI group received smaller stent diameter (3.12 mm vs 3.26 mm; P = .001) and had a lower incidence of ST-segment resolution than the non-LAD-STEMI group (73%, vs 50%; P = .001) (table 2). The use of GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors was numerically lower in the LAD-STEMI group, although the differences between groups were not statistically significant. Of note, almost half of the patients (46%) with LAD-STEMI had the lesion in the proximal LAD compared with 44% of them who had it in the mid/distal LAD.

Table 2. Angiographic and procedural characteristics

| Procedural characteristics | Overall (N = 1498)a | LAD-related STEMI (N = 631)a | Non-LAD-related STEMI (N = 867)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | ||||

| LAD | 631 (42) | 631 (100) | 0 (0) | |

| LMCA | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.3) | |

| RCA | 650 (43) | 0 (0) | 650 (75) | |

| LCx | 207 (14) | 0 (0) | 207 (24) | |

| SVG | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 7 (0.8) | |

| 188 (13) | 72 (11) | 116 (13) | .256 | |

| 3.9 [2.7-6.8] | 4.0 [2.7-7.3] | 3.9 [2.7-6.3] | .366 | |

| 976 (65) | 405 (64) | 571 (66) | .502 | |

| 785 (52) | 312 (49) | 473 (55) | .051 | |

| 885 (60) | 390 (63) | 495 (59) | .113 | |

| .312 | ||||

| DES | 751 (50) | 326 (52) | 425 (49) | |

| BMS | 747 (50) | 305 (48) | 442 (51) | |

| 1.39 (0.65) | 1.37 (0.63) | 1.40 (0.66) | .428 | |

| 23 (18-35) | 23 (18-33) | 23 (18-35) | .154 | |

| 3.20 (0.45) | 3.12 (0.40) | 3.26 (0.47) | < .001 | |

| 221 (15) | 97 (15) | 124 (14) | .564 | |

| .607 | ||||

| 0 | 26 (1.7) | 9 (1.4) | 17 (2.0) | |

| 1 | 12 (0.8) | 5 (0.8) | 7 (0.8) | |

| 2 | 59 (4.0) | 29 (4.6) | 30 (3.5) | |

| 3 | 1396 (94) | 584 (93) | 812 (94) | |

| 852 (63) | 285 (50) | 567 (73) | < .001 | |

|

BMS, bare metal stent; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft. DES, drug-eluting stent; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery, LCx, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SVG, saphenous venous graft; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction. aMedian [interquartile range], mean (standard deviation) or frequency (%). bFisher’s exact test; Pearson’s chi-squared test; Wilcoxon rank sum test. |

||||

Ten-year outcomes

At the 10-year follow-up, POCE did not differ between LAD-STEMI and non-LAD-STEMI group (adjusted HR, 0.95; 95%CI, 0.79-1.13; P = .56) (figure 2). Moreover, no differences were found in terms of each individual component of POCE (all-cause mortality, MI, any revascularization) (figure 3) and other secondary endpoints (figure 1 of the supplementary data). Furthermore, when the expanded adjustment was performed and LVEF was included in the multivariable analysis, there were no inter-group differences between (table 3).

Figure 2. Central illustration. Outcomes of patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction according to the culprit vessel at the 10-year follow-up. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; POCE: patient-oriented composite endpoint.

Figure 3. Time-to-event curves for the patient-oriented composite endpoint (A), all-cause mortality (B), myocardial infarction (C), and any revascularization (D) in patients stratified according to the culprit vessel. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; MI, myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; POCE, patient-oriented composite endpoint.

Table 3. Ten-year outcomes

| 10-year outcomes | LAD-related STEMI (N = 631) | Non-LAD-related STEMI (N = 867) | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | Adjusted HR (95%CI) | Expanded adjusted HR (95%CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-oriented composite endpointc | 220 (34.9) | 307 (35.4) | 0.99 (0.83-1.17) | .87 | 0.95 (0.79-1.13) | .56 | 0.98 (0.78-1.23) | .86 |

| All-cause mortalityd | 131 (21.6) | 179 (21.2) | 1.02 (0.82-1.28) | .84 | 0.93 (0.74-1.18) | .56 | 0.81 (0.59-1.09) | .17 |

| Any myocardial infarctione | 33 (5.5) | 53 (6.3) | 0.86 (0.56-1.33) | .50 | 0.93 (0.60-1.45) | .76 | 1.14 (0.67-1.93) | .61 |

| Any revascularization | 108 (17.4) | 161 (18.8) | 0.93 (0.73-1.18) | .55 | 0.96 (0.75-1.22) | .72 | 1.12 (0.83-1.52) | .45 |

| Device-oriented composite endpointf | 94 (14.3) | 132 (14.2) | 0.98 (0.75-1.28) | .88 | 0.91 (0.70-1.20) | .50 | 0.95 (0.67-1.35) | .77 |

| Cardiac death | 72 (9.8) | 95 (10.0) | 1.06 (0.78- 1.44) | .71 | 0.89 (0.65- 1.23) | .49 | 0.71 (0.47-1.09) | .12 |

| Target vessel myocardial infarction | 16 (2.6) | 36 (4.2) | 0.62 (0.34-1.11) | .10 | 0.69 (0.38-1.25) | .22 | 0.87 (0.43-1.77) | .71 |

| Target lesion revascularization | 44 (7.0) | 63 (7.3) | 0.97 (0.66-1.43) | .89 | 1.01 (0.68-1.49) | .96 | 1.20 (0.76-1.93) | .43 |

| Definite/probable stent thrombosisg | 17 (2.7) | 28 (3.3) | 0.84 (0.46-1.54) | .57 | 0.83 (0.45-1.55) | .57 | 0.80 (0.38-1.73) | .58 |

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; LAD, left anterior descending artery, STEMI: ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Data are expressed as no. (%). aCause-specific Cox regression model adjusted for sex, smoking status, peripheral vascular disease, previous percutaneous coronary intervention, previous coronary artery bypass graft, previous myocardial infarction, and Killip class. bCause-specific Cox regression expanded model, adjusted for baseline comorbidities and left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge. cComposite endpoint of all-cause death, any recurrent myocardial infarction, and any revascularization. dDeath was adjudicated according to the Academic Research Consortium definition. eMyocardial infarction was adjudicated according to the World Health Organization extended definition. fComposite endpoint of cardiac death, target vessel myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and stent thrombosis. gStent thrombosis was defined according to the Academic Research Consortium definition. |

||||||||

Landmark analyses

POCE landmark analysis showed no differences between the 2 groups across different time points. (figure 4A). Looking specifically at the various POCE individual components, the LAD-STEMI group exhibited a higher rate of all-cause mortality within the first year vs the non-LAD-STEMI group (p = 0.041), but this difference disappeared thereafter (figure 4B). Between years 0 and 1, there was also a trend toward a lower rate of myocardial infarction in the LAD-STEMI group vs the non-LAD-STEMI group (p = 0.081), which disappeared after year 1 (figure 4C). No differences were ever found regarding any revascularization (figure 4D) or other secondary endpoints between the 2 groups (figure 2 of the supplementary data).

Figure 4. Landmark analysis for the patient-oriented composite endpoint (A), all-cause mortality (B), myocardial infarction (C), and any revascularization (D) in patients stratified according to the culprit vessel. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; MI, myocardial infarction; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; POCE, patient-oriented composite endpoint.

DISCUSSION

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows: a) STEMI patients with LAD as the culprit vessel have a different baseline clinical profile vs STEMI patients with other culprit vessels; b) in the contemporary era of primary PCI, LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel did not bring worse very long-term outcomes compared with other coronary vessels; c) nevertheless, between years 0 and 1 the LAD-STEMI group exhibited a higher all-cause mortality rate, which disappeared thereafter compared with non-LAD-STEMI group.

Cardiology community knows (as reflected by the ESC guidelines on the management of acute coronary syndromes) that STEMI with LAD involvement as culprit vessel is a clinical marker of high risk of further events.1 LAD-related STEMI represents, approximately, 40% up to 50% of all STEMIs,12,16 and its worse prognosis has been related to the large myocardium covered by the LAD flow compared with the myocardium supplied by other coronary vessels. Of note, those studies were performed in the pre-reperfusion4-7 and early thrombolysis/PCI era,8,9 when PCIs were still not widely available. In the PCI era, there are very few studies (with short or mid-term follow-ups ranging from 1 to 3 years) reporting that LAD-STEMI is associated with an increased risk of stroke, heart failure, all-cause mortality10,17 and cardiovascular death11 after the PCI.

In our analysis, conducted in a cohort where the PCI was extensively performed, LAD as the STEMI culprit vessel did not appear to confer a worse prognosis to patients at the 1- or even 10-year follow-up. Of interest, LAD-STEMI patients exhibited the classical clinical features related to LAD, such as advanced Killip class at the time of presentation, lower ST-segment resolution and lower LVEF, which is similar to previous studies.8-11,17 All these unfavorable clinical characteristics are indeed related to the large amount of myocardium damaged in a LAD-STEMI with subsequent heart failure and ventricular arrhythmias.17-19 Nevertheless, this did not translate into a worse, very long-term clinical outcome. Significantly, even after accounting for variations in LVEF (which we addressed separately in our model due to its perceived role in the outcome cascade) the results showed no differences. This observation stands in contrast to earlier evidence, where the higher mortality rate in this cohort had been partially attributed to the subsequent decline in LVEF after STEMI.9,10

Several explanations may be claimed to understand our main finding. It may be hypothesized that worse outcome related to anterior STEMI may have been overcome by the introduction of the PCI with quick myocardial reperfusion. Pharmacological treatment has been also improved from thrombolysis to the PCI era, not only in terms of antiplatelet agents, but also in terms of secondary prevention (high intensity statins and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin receptor/neprilysin inhibitors for left ventricular dysfunction).20-23 Furthermore, in our study, the LAD-STEMI group had a higher proportion of active smokers. Smoking cessation remains the most critical preventive measure for coronary artery disease. The relationship between smoking and cardiovascular outcomes has been a matter of discussion, as some studies have suggested improved cardiovascular outcomes, even in the long term, among smokers who experienced STEMI.24 However, many of these studies were observational registries conducted in the pre-PCI era. Recent evidence indicates that smoking is associated with more post-PCI long-term adverse outcomes.25 Therefore, the so-called “smoker’s paradox” might be better explained by factors such as younger age and a lower prevalence of other risk factors among smokers. Indeed, in our study, while the LAD-STEMI group had a higher proportion of smokers, they had a lower prevalence of other risk factors, such as peripheral vascular disease and a history of prior PCI or MI.

Last, but not least, in landmark analysis we found that between years 0 and 1, all-cause mortality was more common in the LAD-STEMI group. Notably, in this period, there was a numerically higher number of cardiac deaths (although not statistically significant, P = .12), a similar finding to other existing evidence that found a higher relatively short-term mortality in the LAD-STEMI group within the first 30 days. In these studies, the elevated short-term mortality was associated with acute sequelae, such as heart failure and was also speculated to be connected to other lethal complications, such as ventricular arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock or mechanical complications.10,11 In our cohort, we found a trend towards a higher rate of reinfarction in the non-LAD-STEMI group (P = .081) that was largely unrelated to TLR, TVMI, or stent thrombosis. This observation contrasts with previous literature that reported a more common occurrence of reinfarction at the follow-up in patients with the SVG as the culprit vessel26 as well as the LAD,8 but not in LCx or the RCA.9-11

Our 10-year follow-up revealed similar clinical event rates between LAD-STEMI and non-LAD-STEMI group, indicating absence of long- term divergence. Previous studies showed a favorable post-acute phase prognosis for LAD-STEMI patients,10,11 which is consistent with our findings. In fact, non-cardiac factors seem to impact long-term mortality more than infarct location does.19 Thus, patients with STEMI should receive uniform management focused on secondary prevention strategies, regardless of the culprit vessel. Unfortunately, insufficient long-term data collection limits deeper insights into these outcomes (such as the presence of heart failure, optimal medical therapy, or other comorbidities).

Limitations

This study presents several limitations. First, this is a non-prespecified post-hoc analysis of the EXAMINATION-EXTEND study and therefore its conclusions must be considered only hypothesis generating. The association between infarction and outcomes may be driven by confounders which have not been recorded in the study. Then, several clinical and procedural characteristics were not available for the analysis, such as specified in-hospital or follow-up clinical data, like optimal medical treatment or compliance to medication at the follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

In a contemporary cohort of STEMI patients, there were no differences in POCE between LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel and other vessels at the 10-year follow-up. However, within the first year after STEMI, all-cause death was more common in the LAD-STEMI group. Our results should be considered as hypothesis-generating. Further studies are needed to specifically assess the relationship between infarction location and outcomes in a contemporary setting where interventional and medical treatments are optimized.

FUNDING

The EXAMINATION-EXTEND study was funded by an unrestricted grant of Abbott Vascular to the Spanish Society of Cardiology (promoter). P. Vidal Calés has been supported by a research grant provided by Hospital Clínic at Barcelona, Spain.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study fully complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our Institutional Review Committee. All patients signed a written informed consent form before being included in this study. The clinical ethics committee gave its approval for the analysis of the data collected. In this work, SAGER guidelines regarding sex and gender bias have been followed.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence tools were used during the preparation of this work.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors declare they meet the full criteria and requirements for authorship and have reviewed and agree with the content of the article. P. Vidal Calés, K. Bujak, R. Rinaldi, A. Salazar Rodríguez, S. Brugaletta and M. Sabaté contributed to conceptualization, design, data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. L. Ortega-Paz, J. Gómez-Lara, V. Jiménez-Diaz, M. Jiménez, P. Jiménez-Quevedo, R. Diletti, P. Bordes, G. Campo, A. Silvestro, J. Maristany, X. Flores, A. De Miguel-Castro, A. Íñiguez, A. Ielasi, M. Tespili, M. Lenzen, N. Gonzalo, M. Tebaldi, S. Biscaglia, R. Romaguera, J.A. Gómez-Hospital and P. W. Serruys reviewed and edited the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

M. Sabaté declares he has received consulting fees from Abbott Vascular and iVascular outside the submitted work. R. Romaguera is associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology. The journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The rest of the authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THIS TOPIC?

- – In STEMI patients, the culprit vessel is often regarded as a crucial prognostic factor.

- – This assumption is based on earlier studies conducted during the pre-reperfusion or thrombolysis era, which demonstrated that STEMIs involving the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) were linked to poorer clinical outcomes vs those involving other vessels.

- – In the current PCI era, there is limited data on the long-term prognostic impact of the LAD as the culprit vessel in STEMI patients.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- – Patients with LAD as the STEMI-related culprit vessel have a higher all-cause mortality within the first year after STEMI.

- – However, our study found that this difference did not persist beyond the initial year suggesting that the prognostic impact of the culprit vessel might pertain to the immediate post- STEMI period.

- – Moreover, our results support that (irrespective of the location of the infarction) all STEMI patients should receive uniform medical care in the long-term focused on implementing secondary prevention strategies.

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

2. De Luca G, Suryapranata H, van 't Hof AW, et al. Prognostic assessment of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with primary angioplasty:implications for early discharge. Circulation. 2004;109:2737-2743.

3. Addala S, Grines CL, Dixon SR, et al. Predicting mortality in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PAMI risk score). Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:629-632.

4. Thanavaro S, Kleiger RE, Province MA, et al. Effect of infarct location on the in-hospital prognosis of patients with first transmural myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1982;66:742-747.

5. Stone PH, Raabe DS, Jaffe AS, et al. Prognostic significance of location and type of myocardial infarction:independent adverse outcome associated with anterior location. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:453-463.

6. Hands ME, Lloyd BL, Robinson JS, de Klerk N, Thompson PL. Prognostic significance of electrocardiographic site of infarction after correction for enzymatic size of infarction. Circulation. 1986;73:885-891.

7. Welty FK, Mittleman MA, Lewis SM, Healy RW, Shubrooks SJ, Jr., Muller JE. Significance of location (anterior versus inferior) and type (Q-wave versus non-Q-wave) of acute myocardial infarction in patients undergoing percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty for postinfarction ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:431-435.

8. Kandzari DE, Tcheng JE, Gersh BJ, et al. Relationship between infarct artery location, epicardial flow, and myocardial perfusion after primary percutaneous revascularization in acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1288-1295.

9. Elsman P, van 't Hof AW, de Boer MJ, et al. Impact of infarct location on left ventricular ejection fraction after correction for enzymatic infarct size in acute myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1239.

10. Entezarjou A, Mohammad MA, Andell P, Koul S. Culprit vessel:impact on short-term and long-term prognosis in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Open Heart. 2018;5:e000852.

11. Koga S, Honda S, Maemura K, et al. Effect of Infarction-Related Artery Location on Clinical Outcome of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction in the Contemporary Era of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention- Subanalysis From the Prospective Japan Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (JAMIR). Circ J. 2022;86:651-659.

12. Sabate M, Cequier A, Iñiguez A, et al. Everolimus-eluting stent versus bare-metal stent in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (EXAMINATION):1 year results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:1482-1490.

13. SabatéM, Brugaletta S, Cequier A, et al. Clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated with everolimus-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents (EXAMINATION):5-year results of a randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;387:357-366.

14. Brugaletta S, Gomez-Lara J, Ortega-Paz L, et al. 10-Year Follow-Up of Patients With Everolimus-Eluting Versus Bare-Metal Stents After ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1165-1178.

15. SabatéM, Cequier A, Iñiguez A, et al. Rationale and design of the EXAMINATION trial:a randomised comparison between everolimus-eluting stents and cobalt-chromium bare-metal stents in ST-elevation myocardial infarction. EuroIntervention. 2011;7:977-984.

16. Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:54-63.

17. Reindl M, Holzknecht M, Tiller C, et al. Impact of infarct location and size on clinical outcome after ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2020;301:14-20.

18. Chen ZW, Yu ZQ, Yang HB, et al. Rapid predictors for the occurrence of reduced left ventricular ejection fraction between LAD and non-LAD related ST-elevation myocardial infarction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2016;16:3.

19. Pedersen F, Butrymovich V, Kelbæk H, et al. Short- and long-term cause of death in patients treated with primary PCI for STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2101-2108.

20. Wilt TJ, Bloomfield HE, MacDonald R, et al. Effectiveness of statin therapy in adults with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1427-1436.

21. Freemantle N, Cleland J, Young P, Mason J, Harrison J. beta Blockade after myocardial infarction:systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ. 1999;318:1730-1737.

22. Pfeffer MA, Greaves SC, Arnold JM, et al. Early versus delayed angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition therapy in acute myocardial infarction. The healing and early afterload reducing therapy trial. Circulation. 1997;95:2643-2651.

23. Mehran R, Steg PG, Pfeffer MA, et al. The Effects of Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibition on Major Coronary Events in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction:Insights From the PARADISE-MI Trial. Circulation. 2022;146:1749-1757.

24. Barbash GI, White HD, Modan M, et al. Significance of smoking in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Experience gleaned from the International Tissue Plasminogen Activator/Streptokinase Mortality Trial. Circulation. 1993;87:53-58.

25. Yadav M, Mintz GS, Généreux P, et al. The Smoker's Paradox Revisited:A Patient-Level Pooled Analysis of 18 Randomized Controlled Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1941-1950.

26. Stone SG, Serrao GW, Mehran R, et al. Incidence, predictors, and implications of reinfarction after primary percutaneous coronary intervention in ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction:the Harmonizing Outcomes with Revascularization and Stents in Acute Myocardial Infarction Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:543-551.

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Calcified coronary lesions are becoming more prevalent and remain therapeutically challenging. Although a variety of devices can be used in this setting, cutting balloons (CB) and scoring balloons (SB) are powerful and simple tools to treat calcified plaques vs more complex devices. However, there are some drawbacks: these are stiff and bulky balloons that, as a first device, complicate lesion crossing and navigability in the presence of tortuosity, thus making it extremely difficult to recross once the balloon has been inflated. The objective of this study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of the new Naviscore SB designed to overcome these drawbacks.

Methods: The first-in-man Naviscore Registry is a multicenter, prospective trial that included 85 patients with moderate (34%) or severe (66%) de novo calcified coronary lesions located in the native arteries, with stable angina and an indication for percutaneous coronary intervention.

Results: Mean age was 71 ± 11 years, with a high prevalence of comorbidities. Used as the first device, the Naviscore was able to cross 76% of the lesions and was used in 98% of the cases effectively modifying the calcified plaque. Procedural success was achieved in 94% of cases. Basal stenosis of 81 ± 12% decreased to 33 ± 8.5% after Naviscore and to 7.5 ± 2.6% after stent implantation. There were no major adverse cardiovascular events during admission. Perforation, device entrapment or flow-limiting dissections did not occur—only type A/B dissections in 13%—which were fixed with stent implantation. Device performance was deemed superior to the usual SB or CB used by the participant centers.

Conclusions: The Naviscore SB is very effective crossing severely calcified lesions as the first device, with effective plaque modification, stent expansion and an excellent safety profile. The Naviscore improves the behavior of current CB and SB. Due to its simplicity of use and performance, the Naviscore can be the first-choice SB to treat significant calcified lesions.

Keywords: Calcified coronary lesions. Scoring balloon. Plaque modification.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Las lesiones coronarias calcificadas son cada vez más prevalentes y suponen un reto terapéutico. Aunque se pueden tratar con distintos dispositivos, los balones de corte (BC) y de scoring (BS) son herramientas potentes y de más fácil uso que otros dispositivos de mayor complejidad. Sin embargo, tienen un alto perfil de cruce, son rígidos y cuesta cruzar la lesión como primer dispositivo; navegan mal y es difícil recruzar cuando ya se ha dilatado el balón. El objetivo del estudio fue evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad del nuevo BS Naviscore, diseñado para soslayar estos inconvenientes.

Métodos: El Registro Naviscore es un estudio por primera vez en humanos, multicéntrico y prospectivo, en 85 pacientes con lesiones coronarias de novo con calcificación moderada (34%) o grave (66%), localizadas en arterias nativas, con angina estable e indicación de angioplastia.

Resultados: La edad media fue de 71 ± 11 años y hubo una alta prevalencia de comorbilidad. Naviscore cruzó como primer dispositivo en el 76% de los casos y se empleó hasta en el 98% para dilatar la lesión. Se logró el éxito del procedimiento en el 94%. La estenosis basal pasó del 81 ± 12 al 33 ± 8,5% después de Naviscore y al 7,5 ± 2,6% después del stent. No se registraron eventos coronarios adversos durante la hospitalización. Tampoco hubo casos de perforación, atrapamiento del dispositivo ni disección limitante del flujo; solo disecciones tipo A/B en el 13%, resueltas tras el stent. El comportamiento de Naviscore se evaluó como superior al de los BC o BS habituales en los centros participantes.

Conclusiones: Naviscore tiene una alta capacidad de cruce de las lesiones como primer dispositivo, una gran eficacia en la modificación de la placa y un excelente perfil de seguridad. Por su facilidad de uso y eficacia, Naviscore podría considerarse como el BS de primera elección en el tratamiento de lesiones calcificadas complejas.

Palabras clave: Lesiones coronarias calcificadas. Balón scoring. Modificación de placa.

Abbreviations:

CB: cutting balloon. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. SB: scoring balloon.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, the number of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) involving moderate-to-severe calcified plaques is increasing due to a progressively aging population and extending procedural indications into more comorbid patients. The presence of such calcification is extremely relevant as it is strongly associated with worse outcomes, specially by means of stent underexpansion, a potent predictor of stent thrombosis or in-stent restenosis.1-3 Moreover, calcified plaques can make advancing the devices difficult and trigger stent deformation and entrapment, coronary artery dissection, or perforation.1,4-6. Currently, there is a growing interest in the assessment of plaque morphology and its modification prior to stent implantation, which has led to the development of multiple tools such as rotational atherectomy, lithotripsy, orbitational atherectomy, cutting balloons (CB) and scoring balloons (SB).7-11 The latter are easy to use and aim to create a controlled fracture of calcium deposits and plaque dilatation to facilitate stenting.12-14 However, despite their theoretical simplicity, these devices are bulky and stiff, making it difficult to cross the lesion at the first attempt, navigate the vessel, and recross the lesion once inflated. Therefore, there is a need for a more trackable and better-profiled SB to improve the uptake of these devices to treat calcified coronary artery disease.

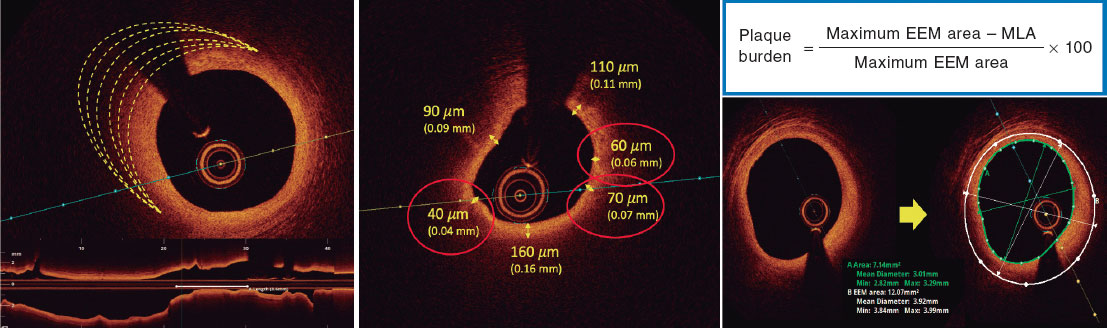

The newly designed Naviscore SB (iVascular, Spain) seeks to address these drawbacks. Its structure is based on 125-µm thick nitinol laser cut filaments arranged in an axial pattern placed over a semi-compliant high-pressure balloon with a nominal pressure of 8 atm, a rated burst pressure of 20 atm, and a mean burst pressure of 26 atm (figure 1). A nylon compensation tube in the shaft helps to re-wrap during balloon deflation. The mechanical properties of nitinol tend to regain its original shape once the balloon has been deflated. The nylon compensation tube elongates once the balloon has been inflated and due to its elastic properties, it regains its original length when deflated (video 1 of the supplementary data). The 2 mechanisms produce a powerful re-wrapping of the entire system when the balloon has been deflated, regaining its original crossing profile, which allows for easy lesion recross and further dilatations as many times as required. Axial distribution of scoring elements provides a high push against calcified lesions. Nitinol elastic properties provide a better navigability through tortuous calcific vessels compared with rigid scoring elements, such as stainless steel. The durable hydrophilic coating of the Hydrax Plus catheter (iVascular, Spain) significantly reduces its coefficient of friction to 0.04 by increasing slip and navigability. Also, its axial design enables a far larger contact area with the vessel wall compared with other devices with spiral configuration of nitinol filaments such as the AngioSculpt catheter (Philips Healthcare, The Netherlands) (figure 2). In vitro testing (iVascular, Spain) was conducted to measure the crossing profile of different SBs using a non-contact laser meter where the profile is calculated through the shadow that has been created. This allows us to measure the profile without exerting any pressure on the device.15 The Naviscore crossing profile is 5% lower than Angiosculpt, and 31% lower than Wolverine (Boston Scientific, United States). This catheter is available in a wide range of measures from 1.5 mm up to 3.5 mm in diameter and from 6.0 mm up to 15 mm in length, all of them compatible with a 6-Fr guiding catheter.

Figure 1. Structure of the Naviscore SB. MBP, mean burst pressure; RBP, rated burst pressure.

Figure 2. In vitro model assessment of the AngioSculpt scoring surface (upper image) vs the Naviscore (lower image). The Naviscore scoring surface is 6 times larger than that of the AngioSculpt.

The present study aims to demonstrate the safety and efficacy profile associated with crossing and treating calcified coronary lesions with the Naviscore SB.

METHODS

The Naviscore first-in-man study is a multicentric and prospective registry that evaluated the device safety and efficacy profile in the treatment of calcified lesions in 85 patients from 10 centers (9 in Spain and 1 in Portugal), all from the Euro 4C Group, founded in 2018 and focused on the cardiac care of calcified and complex patients. All operators involved in this study were experts in the treatment of calcified coronary lesions and familiar with most tools designed to treat such lesions.

Inclusion criteria were the presence of de novo moderate-to-severe calcified lesions by angiographic criteria in the native coronary tree of patients with chronic coronary syndrome scheduled for a PCI due to symptom persistence despite optimal medical therapy and/or evidence of inducible ischemia. The only exclusion criterion was the presence of the patient’s hemodynamic compromise.

The study was designed to assess the safety and efficacy profile of Naviscore in terms of delivery success when used as the first device to dilate the lesion, plaque modification capabilities, and complications. Consequently, operators were asked to use the Naviscore in all cases as the first device to cross and dilate the lesion. However, in cases of failed lesion crossing, dilatation with a small balloon was recommended with subsequent re-use of the same Naviscore catheter.

Operators involved in the study had little prior experience with the Naviscore in, at least, 3 cases and were asked to include, at least, 5 patients in the study. The operators assessed the performance of the catheter in each procedure in terms of pushability, navigability, crossing, deflation time, re-wrap, recrossing capabilities and ease of retrieval, and made a subjective comparison with their routinely used SB or CB.

The baseline clinical characteristics were recorded prior to the procedure and angiographical and optical coherence tomography (OCT) images were analyzed separately by 2 different operators. Coronary angiography was performed using, at least, 2 orthogonal projections to show stenosis as it is commonly used in the routine clinical practice. The view with the most severe stenosis was selected for the quantitative analysis of the lesion before and after the PCI. Lesion calcification was angiographically categorized as none/mild, moderate (radiopacities were only noted during the cardiac cycle movement prior to contrast injection) or severe (radiopacities noted without cardiac movement prior to contrast injection involving both sides of the arterial lumen).16 Lesions were categorized as A, B1, B2 and C based on the modified ACC/AHA Task Force classification, which is in turn, based on the morphology and potential complexity of the PCI.17 Procedural success was defined as an angiographically residual percent diameter stenosis < 30% after stent implantation, absence of major complications and final Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade-3 flow.18 OCT analysis was performed as recommended in the routine clinical practice: lesion and proximal and distal references within 5 mm were used to estimate diameters and areas. Calcium cracks were defined as fissures involving a calcified region.19,20

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables with a normal distribution, median and interquartile range [IQR] for continuous variables with a non-Gaussian distribution, and counts and percentages for categorical data.

Statistical analyses were performed using the Stata software version 16.1 (College Station, TX, United States).

Ethical considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all the patients and the study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee. The authors declare that procedures were followed according to the regulations established by the Clinical Research and Ethics Committee and the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association.

RESULTS

From November 2021 through February 2022, a total of 85 patients—80% males—with a mean age of 71 ± 11 years were included in the present study. One center included a total of 21 patients and the remaining 9, between 5 and 10 patients each. Baseline patient and lesion characteristics are shown in table 1. Regarding comorbidities, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease was 44%, 70%, 75%, and 18% respectively. Prior revascularization was present in 43% of the patients (PCI in 38% and coronary artery bypass graft in 16%). The left anterior descending coronary artery was the most common location of target lesions (41%), followed by the right coronary artery (28%), left circumflex artery (16%) and left main coronary artery (15%). Most lesions (87%) were categorized as type B2/C, 66% were severely calcified and 34% had moderate calcification by angiographic assessment. Chronic total occlusion was reported in 10% of treated lesions. Reference vessel diameter was 3.0 ± 0.5 mm; mean lesion length, 20.3 ± 9.4 mm; and diameter stenosis, 81.4 ± 12%.

Table 1. Baseline clinical and angiographic characteristics

| Clinical and angiographic characteristics (n = 85) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 71 ± 11 |

| Male | 68 (80%) |

| Diabetes | 37 (44%) |

| Dyslipidemia | 59 (70%) |

| Hypertension | 67 (75%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 15 (18%) |

| Current/former smokers | 53 (62%) |

| Prior PCI/CABG | 37 (43%) |

| Type B2/C lesions | 74 (87%) |

| Severe calcification | 56 (66%) |

| Moderate calcification | 29 (34%) |

| Basal percent diameter stenosis | 81 ± 12% |

| Chronic total occlusion | 8 (10%) |

| Lesion location: Left main coronary artery | 13 (15%) |

| LAD | 35 (41%) |

| RCA | 24 (28%) |

| LCx | 13 (16%) |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery. |

|

The Naviscore catheter diameters used to dilate the lesions were 2.0 mm (21%), 2.5 mm (38%), 3.0 mm (31%), and 3.5 mm (10%). Mean number of device inflations was 2.7 ± 1.5 times.

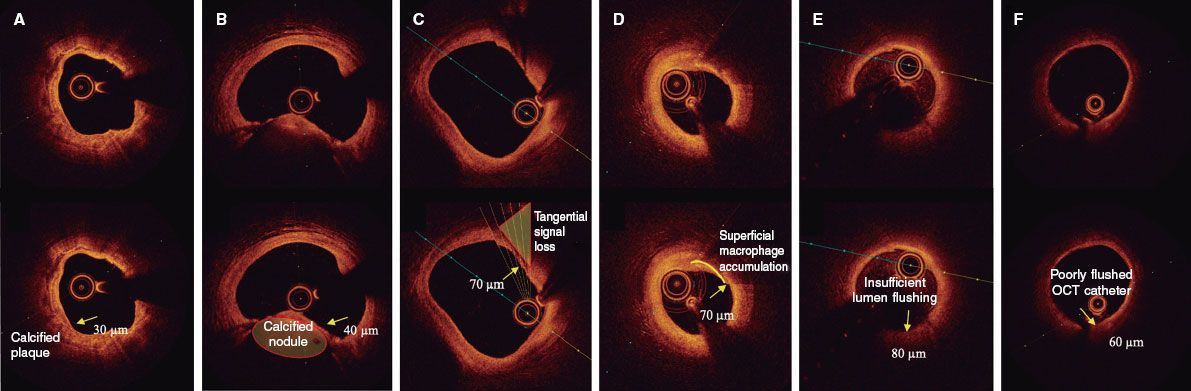

The Naviscore crossing performance of is shown in figure 3. Despite the strong recommendation to use Naviscore as the first device, some operators decided to use Rotablator or small balloons first in 10 patients due to severely narrowed and/or calcified vessels. In all those cases, the Naviscore successfully crossed and dilated the lesion after the first attempt. In the 75 patients in whom the Naviscore was used as the first device, the lesions were crossed and treated successfully in 57 (76%) of them. In the remaining 18 (24%) patients, the Naviscore crossed the lesion after pre-dilatation with a small balloon in 16 (89%) patients. Only 2 patients had non-crossable lesions.

Figure 3. Crossing performance of the Naviscore.

PCI results and in-hospital outcomes are shown in table 2. Procedural success was achieved in 94% of cases. The mean lesion percent diameter stenosis decreased from 81.4 ± 12% at baseline to 33.3 ± 8.5% after Naviscore dilatation, with a residual percent diameter stenosis of 7.5 ± 2.6% after stent implantation. There were no in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events or any cases of perioperative perforation or device entrapment. Coronary dissections occurred in 13% of the cases (all of them type A or B) and resolved after stent implantation.

Table 2. Angiographic and in-hospital results

| Angiographic and in-hospital clinical results (n = 85) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Procedural success: residual percent diameter stenosis < 30% after stenting, absence of major complications and TIMI grade-3 flow | 80 (94%) |

| Percent diameter stenosis pre-Naviscore | 81 ± 12% |

| Percent diameter stenosis post-Naviscore | 33 ± 8.5% |

| Percent diameter stenosis post-stenting | 7.5 ± 2.6% |

| MACE (in-hospital) | 0% |

| Death, MI, emergency CABG | 0% |

| Perforation | 0% |

| Limiting flow dissection | 0% |

| Type A or B dissection | 11 (13%) |

| Device entrapment | 0% |

|

CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

|

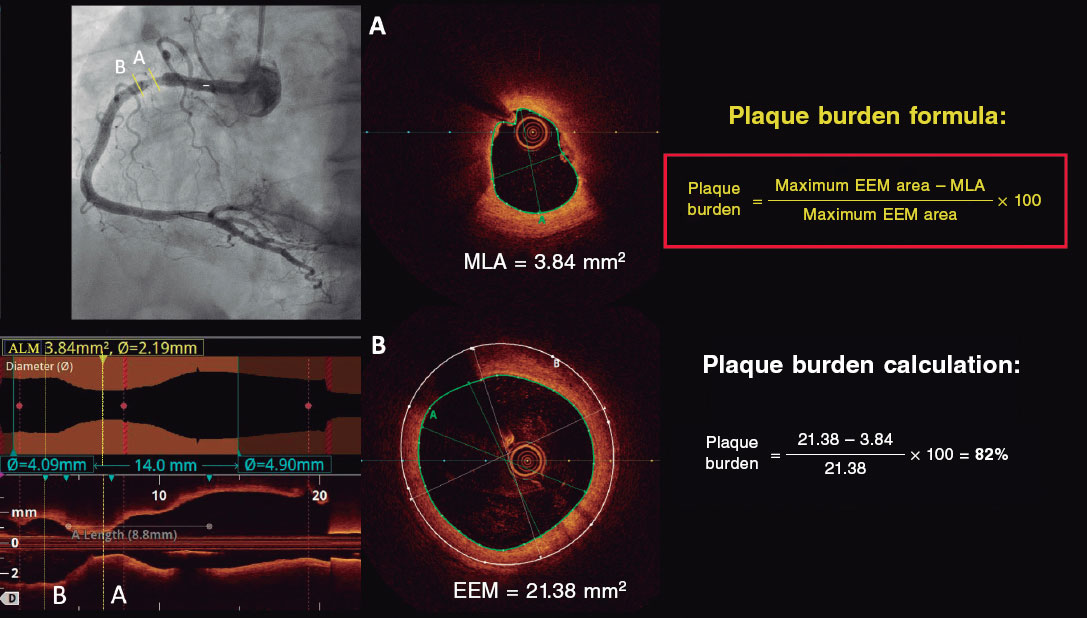

Ten procedures were OCT-guided. Pre-dilatation analysis could only be performed in 5 lesions; the OCT catheter could not cross the remaining lesions. Four of those had Fujino’s scores8 of 4 and in 2 of them the nodules protruded into the lumen. After dilatation, all lesions exhibited dissections that covered the intima and the media. Fractures were seen in all calcified plaques, which were deeper and wider in non-nodular calcified regions. Enlargement of lumen area after treatment with the Naviscore and correct stent apposition and expansion was observed in all imaging-guided cases (figure 4).

Figure 4. Clinical examples of 2 different lesions treated with the Naviscore. Angiography and baseline OCT (A) after dilatation with the Naviscore catheter (B) and post-stent implantation (C). On the left side, panel A shows a severely stenotic fibrocalcific plaque on the left anterior descending coronary artery that Naviscore (B) modifies creating calcium fractures (*) and dissection (arrow) resulting in stent implantation with good apposition and expansion (C). The right side shows a severely calcified plaque on the right coronary artery (A) with an arc of calcium of 180º at its proximal edge (lateral OCT picture) and 360º at its distal edge (central OCT picture) that the Naviscore modifies (B) creating calcium fractures (*) and dissection (arrow) resulting in stent implantation with good apposition and expansion (C). OCT, optical coherence tomography.