Available online: 09/04/2019

Editorial

REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:310-312

The future of interventional cardiology

El futuro de la cardiología intervencionista

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia, United States

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has revolutionized the treatment of aortic stenosis and is currently the treatment of choice for degenerative aortic stenosis from 75 years of age. Despite its minimally invasive nature, for years, the length of stay after TAVI was approximately 1 week.1 Due to technological advancements and perioperative care, in recent years, there has been a progressive reduction in the length of stay after TAVI. Several factors have contributed to this trend, such as patient selection (preoperative planning and inclusion of patients of lower surgical risk), simplification of the procedure (use of local anesthesia, secondary radial access, smaller caliber catheters and vascular complications, standardization of implantation techniques with fewer conduction disorders) and optimization of peri- and postoperative care (accelerated circuits following after TAVI and outpatient monitoring).

In an article published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Pimienta González et al.2 present the results of the first 100 patients treated with TAVI in a noncardiac surgery center, with the implementation of an early discharge protocol since the beginning of the program. The patients’ mean age was 82 years and their surgical risk was low-to-intermediate (Society of Thoracic Surgeons score of 4.38%). A total of 97% of all procedures were performed via transfemoral access (95% via transcatheter access) and 3% via surgical transaxillary access, in patients with mostly native aortic stenosis (98%). All patients received a self-expanding supra-annular valve: 87% an Evolut valve (Medtronic, United States) and 13% an ACURATE valve (Boston Scientific, United States). There were no deaths during the procedure nor any cases of conversion to open surgery. The median length of stay was 2 days (1-19), with 76% of patients being discharged within the first 48 hours. The 30-day event rate was low: pacemaker, 13%; major vascular complication, 4%; stroke, 1%; and cardiovascular mortality, 1%. There were only 6% readmissions within the first month.

Procedural results and the subsequent care are remarkable, considering an early discharge protocol in an unselected population in a center without prior experience performing TAVI. A quarter of the procedures were proctored, which undoubtedly contributed to the excellent results reported. A total of 27% of patients were discharged at 24 hours and 76% at 48 hours due to a rigorous peri-TAVI care protocol consisting of in-person visit 1 week prior to the procedure, nursing call 48 hours prior to the procedure, telephone consultation 48 hours following discharge and in-person consultation at 10 days, and the systematization of the conduction disorders approach, which is currently the “Achilles’ heel” of TAVI and the main reason for delayed discharge.

However, there are some limitations that should be mentioned. Firstly, the authors do not specify which clinical criteria were predefined to categorize hospital discharges as very early (< 24 h), early (24-48 h) or late discharges (> 48 h), nor the percentage of patients who received ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring; information that could be useful for other centers with similar characteristics. Furthermore, all procedures were performed under general anesthesia, which contrasts with most protocols of early discharge, which prioritize local anesthesia and conscious sedation, given its potential benefit in terms of mortality, speed of recovery and shorter length of stay.3 Finally, one cannot rule out some selection bias (low surgical risk; 3, alternative access; 3%, bicuspid valves; 2%, valve-in-valve; 0%, pure aortic regurgitation). Nevertheless, the work of Pimienta González et al.2 exemplifies the possibility of implementing this type of protocols (duly prespecified and proctored) during the learning curve in contemporary clinical practice.

The growing number of TAVIs has triggered the development of standardized measures and protocols aimed at reducing the length of stay and improving the efficiency of resources. Several studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy profile of an early discharge strategy (24-72 h) after TAVI. In 2015, Durand et al.4 first described early discharge within the first 72 hours in selected patients treated with transfemoral TAVI with local anesthesia as a safe strategy with a low rate of complication. Subsequently, large-scale international studies reaffirmed the safety profile of an early discharge strategy through the implementation of dedicated protocols with rapid recovery circuits and pre-established criteria for early discharge.5-8 The Vancouver 3M Clinical Pathway study, with more than 400 patients from 13 North American low- (< 100 TAVIs per year), intermediate- or high-volume centers (> 200 TAVIs per year) achieved hospital discharges within 24 hours in 80% of patients and within 48 hours in 90%, regardless of the experience and volume of the participant centers.6 This circuit was subsequently validated in a low-volume center with limited experience performing TAVIs, with a mortality rate of 0.6% and a readmission rate of 6.7% at 30 days;9 figures very similar to those reported by Pimienta González et al.2 in their series. However, these findings contrast with data from large registries that demonstrated that there is an inverse association between volume and mortality, especially for the first 100 cases.10 While the results of the present study suggest a possible attenuation of the learning curve with new devices and contemporary implantation techniques, they highlight the importance of optimizing and systematizing not only the aspects of the procedure (“minimalist TAVI”), but also the clinical and logistical aspects throughout the entire care process, from before to after the procedure.

Of note, most of the evidence on early discharge after TAVI comes from studies with a predominance of balloon-expandable valves (traditionally associated with lower rates of pacemakers), which contrasts with the present work, in which 100% of the devices used were self-expanding valves. Some studies have previously explored the safety profile of early discharges in patients treated with self-expanding valves. In an American registry with nearly 30,000 patients who underwent elective TAVI with the self-expanding Evolut valve, the discharge rate the next day after TAVI was close to 60%.11 Similarly, Ordoñez et al.12 described the safety profile of early discharge after TAVI with the self-expanding ACURATE neo valve in 368 unselected patients, 55% at 24 hours and 74% at 48 hours, without observing an increased risk of death or readmission at 30 days.

In conclusion, the study by Pimienta González et al.2 is yet another demonstration of the applicability of this type of clinical pathways in our environment and the routine clinical practice, provided they are conducted in a structured and systematized manner.13-15 After the simplification of the procedure, the latest generation devices, contemporary implantation techniques, the patients’ lower risk profile and postoperative expansion of accelerated circuits, the “minimalist” hospitalization after “minimalist TAVI” has already become a common practice and a key tool in terms of efficiency to be able to face the increasing number of TAVIs in the coming years and the expansion of its indications.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Jiménez-Quevedo P, Muñoz-García A, Trillo-Nouche R, et al. Time trend in transcatheter aortic valve implantation:an analysis of the Spanish TAVI registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:96-105.

2. Pimienta González R, Quijada Fumero A, Farráis Villalba M, et al. Early discharge following transcatheter aortic valve implantation:a feasible goal during the learning curve?REC Interv Cardiol. 2025;7:146-153.

3. Villablanca PA, Mohananey D, Nikolic K, et al. Comparison of local versus general anesthesia in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement:A meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:330-342.

4. Durand E, Eltchaninoff H, Canville A, et al. Feasibility and safety of early discharge after transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the Edwards SAPIEN-XT prosthesis. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1116-1122.

5. Barbanti M, van Mourik MS, Spence MS, et al. Optimising patient discharge management after transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation:the multicentre European FAST-TAVI trial. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:147-154.

6. Wood DA, Lauck SB, Cairns JA, et al. The Vancouver 3M (Multidisciplinary, Multimodality, But Minimalist) Clinical Pathway Facilitates Safe Next-Day Discharge Home at Low-, Medium-, and High-Volume Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Centers:The 3M TAVR Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:459-469.

7. Durand E, Beziau-Gasnier D, Michel M, et al. Reducing length of stay after transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation:the FAST-TAVI II trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:952-962.

8. Frank D, Durand E, Lauck S, et al. A streamlined pathway for transcatheter aortic valve implantation:the BENCHMARK study. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1904-1916.

9. Hanna G, Macdonald D, Bittira B, et al. The Safety of Early Discharge Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Among Patients in Northern Ontario and Rural Areas Utilizing the Vancouver 3M TAVI Study Clinical Pathway. CJC Open. 2022;4:1053-1059.

10. Carroll JD, Vemulapalli S, Dai D, et al. Procedural Experience for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement and Relation to Outcomes:The STS/ACC TVT Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:29-41.

11. Batchelor WB, Sanchez CE, Sorajja P, et al. Temporal Trends, Outcomes, and Predictors of Next-Day Discharge and Readmission Following Uncomplicated Evolut Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13:e033846.

12. Ordoñez S, Chu MWA, Diamantouros P, et al. Next-Day Discharge After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation With the ACURATE neo/neo2 Self-Expanding Aortic Bioprosthesis. Am J Cardiol. 2024;227:65-74.

13. Asmarats L, Millán X, Cubero-Gallego H, et al. Implementing a fast-track TAVI pathway in times of COVID-19:necessity or opportunity?REC Interv Cardiol. 2022;4:150-152.

14. Garcia-Carreno J, Zatarain E, Tamargo M, Elizaga J, Bermejo J, Fernandez-Aviles F. Feasibility and safety of early discharge after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2023;76:660-663.

15. Herrero-Brocal M, Samper R, Riquelme J, et al. Early discharge programme after transcatheter aortic valve implantation based on close follow-up supported by telemonitoring using artificial intelligence:the TeleTAVI study. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2025;6:73-81.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common arrhythmia with an incidence rate of approximately 2% of the general population in the developed world. It is usually a consequence of underlying cardiovascular or thoracic morbidities, cardiovascular stress, toxicities, or age-related degeneration. The presence of AF may provoke or aggravate cardiocerebrovascular disease, resulting in stroke, dementia, worsening heart failure, disturbances of mood and quality of life. Thromboprophylaxis is a fundamental and critical element of its management.

Warfarin, the most widely used oral vitamin K antagonist (VKA), was first used clinically during the 1950s but its application for stroke prevention in patients at risk of AF-related thromboembolism only became clinically commonplace after the metanalysis of early trials vs placebo, or the then standard of care. This showed a remarkable stroke reduction of 64% and an often forgotten 26% reduction of mortality, which favored anticoagulation.1 There is, however, one major problem: major bleeds are common (2%-3% per year), of which intracranial bleeding (1% per year) often causes more serious strokes than those of ischaemic etiology. Major haemorrhage is usually due to an underlying arteriopathy and/or excessive anticoagulation due to drug-drug and food-drug interactions increasing the anticoagulant potency of the VKA. Regular monitoring of the anticoagulation status is necessary, and patient education/counselling is needed to encourage patient adherence and persistence with therapy. Both patients and doctors often prefer to use the considerably less effective approach using aspirin, despite its associated bleeding risks.

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), which are at least equally effective and less complicated by intracranial bleeds, entered the therapeutic armamentarium in 2010.2 Dosing depends to a certain degree on a few patient characteristics, such as renal function, age and body weight. They are not compromised by food-drug interactions but co-medication with P-glycoprotein inhibitors does result in elevated plasma concentrations. DOACs do not need regular monitoring. As a class effect, the risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding is 25% higher, and clinically relevant non-major bleeding remains a frequent and troublesome concern. It does not come as a surprise, then, that many patients continue to be reluctant to accept anticoagulant therapy to avert a future, albeit serious event. Drug doses are often skipped, and discontinuation is a common finding.3

Some patients are at high risk of bleeding complications, regardless of which anticoagulant is being used, and others remain vulnerable to ischaemic stroke, even when the anticoagulant is properly prescribed and appropriately taken. Since most AF-related thrombi form in the left atrial appendage (LAA) a mechanical approach, such as excising, closing or occluding the appendage is a therapeutic option. When patients with high-stroke-risk AF undergo cardiac surgery, many surgeons routinely excise the LAA as a preventive measure. For other patients the LAA may be closed with a ligature inserted transcutaneously. However, for most patients at high risk of AF-related stroke for whom a mechanical solution is thought necessary, an occlusion device may be inserted transvenously and placed through the atrial septum and into the LAA. Following device insertion, antiplatelet drugs or full or reduced-dose anticoagulants are used to prevent thrombus formation on the newly implanted foreign body. Although the therapy has proven to be as effective as VKA anticoagulation4 and is possibly, at least, as effective as DOAC therapy,5 this remains to be conclusively proven by randomized clinical trials.

The Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Study (LAAOS III) has conclusively demonstrated that removing/ligating the orifice of the LAA is very effective at reducing stoke or systemic embolism in patients with high-risk AF who undergo surgery for coronary revascularization or heart valve surgery.6 However, almost 80% of the patients from the study were also still on anticoagulants 3 years after surgery, which raises the question about whether the most effective stroke-reducing therapy for patients with high-risk AF, not undergoing surgery, should also be a combination of oral anticoagulation and LAAC (left atrial appendage closure) with a mechanical device. It does not come as a surprise that a new study (LAAOS IV) recruiting AF patients at high risk of stroke despite anticoagulation (CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 4) will compare anticoagulation with anticoagulation plus a mechanical device.7 (LAAOS IV - Research Studies - PHRI - Population Health Research Institute of Canada).

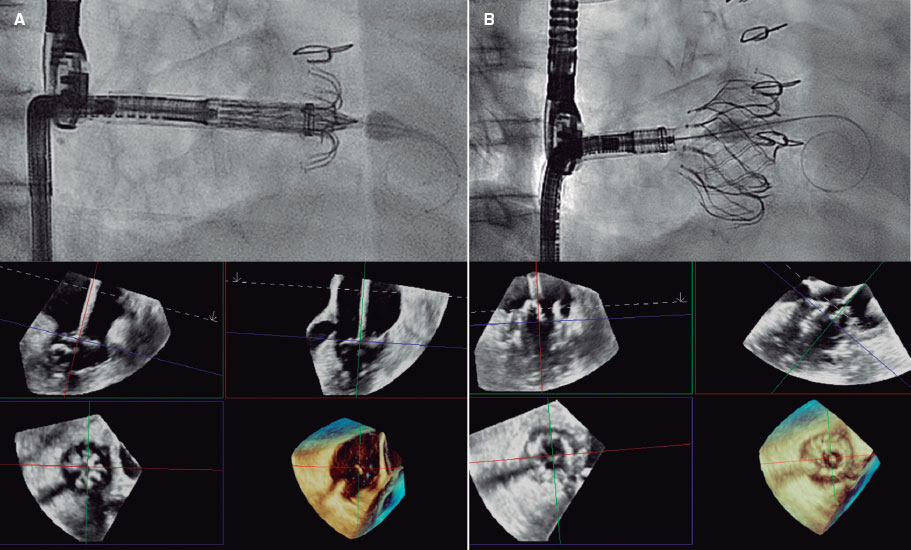

In a recent paper published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Amaro et al. described their study which is also designed to address this issue, choosing a specific group of patients who have suffered a stroke despite anticoagulation (breakthrough stroke).8 Although this is not a rare event with an incidence rate is 1%/year in anticoagulated patients due to AF, there is no accepted and fully investigated therapeutic solution to this clinical problem (figure 1). If the stroke is ischaemic and cardioembolic it is likely related directly to the AF (3 of 4 breakthrough strokes). Anticoagulant therapy might not have been prescribed or taken correctly, which can be improved. If current antithrombotic therapy seems optimal, as in the proposed study by Amaro et al.8, physicians sometimes consider changing the anticoagulant, increasing VKA to an INR > 3.0, using an off-label high dose of a DOAC, or adding antiplatelet therapy like aspirin—none of which appear beneficial. In these circumstances, a practical solution may be switching to a mechanical device requiring a short course of antiplatelet therapy or low-dose anticoagulation, or adding a mechanical device to the existing anticoagulant regimen. Although none of these approaches has been fully demonstrated, substantial observational data 9-11 support transitioning from anticoagulation to LAAC therapy, justifying ongoing randomized clinical trials in this patient population. These trials compare LAAC therapy to anticoagulant treatment, or to no thromboprophylaxis if patients with bleeding complications associated with oral anticoagulants are also elilgible for enrollment. The results of the OCCLUSION-AF PROBE design trial, with 750 patients and documented AF and ischaemic strokes or transient ischaemic attacks randomized to DOAC or LAAC are expected shortly.12

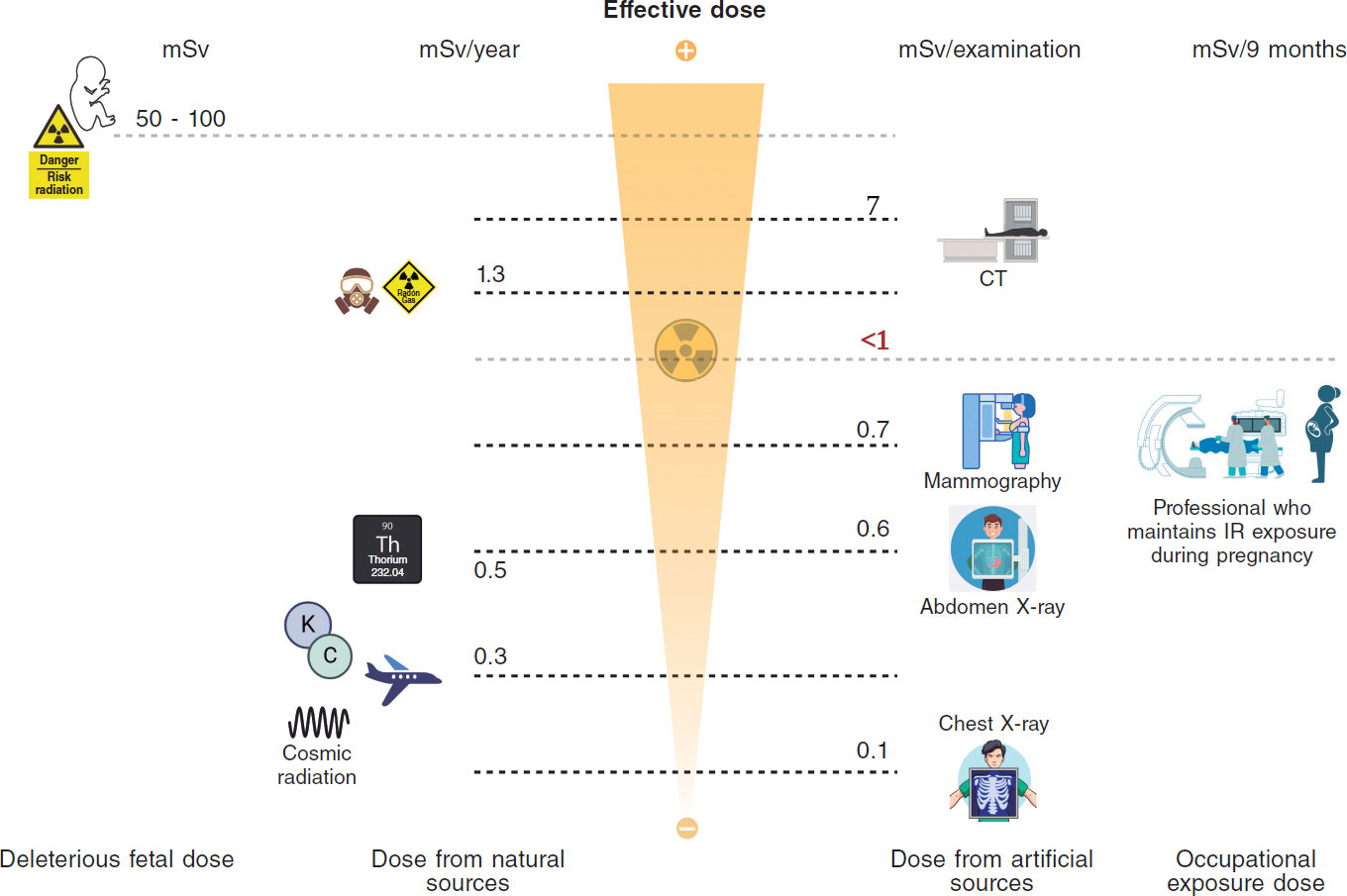

Figure 1. Approach to patients with atrial fibrillation who suffer a stroke whilst treated with an anticoagulant. AF, atrial fibrillation; D/D, drug-drug; F/D, food-drug; LAAC, left atrial appendage closure; LAAO, left atrial appendage occlusion; OAC, oral anticoagulants. a Direct oral anticoagulants drug level/coagulation tests of limited value with short acting medications. b Plus short term OACs, longer term aspirin or dual antiplatelet therapy, or low dose of direct oral anticoagulants.

There is some observational study support for the hybrid approach of adding LAAC to inadequate anticoagulant therapy, a strategy for preventing a recurrence of oral anticoagulation-resistant cardioembolic stroke in patients with AF and no major oral anticoagulation-related bleeding complications.13 Several groups have proposed and are conducting such studies, such as the ELAPSE trial (Early closure of left atrial appendage for patients with atrial fibrillation and ischaemic stroke despite anticoagulation therapy; NCT05976685) which will help them, together with the ADD-LAAO study (Oral anticoagulation alone vs oral anticoagulation plus left atrial appendage occlusion in patients with stroke despite ongoing anticoagulation) led by Amaro et al. to confirm or refute the value of this hybrid approach. Successful results of these studies would help us widen extensively the indication for LAAC therapy, which is now a procedure that can be performed by skilled operators with a complication rate no greater than that of other common procedures in interventional cardiology.14

This strategy of using all antithrombotic approaches may be more effective therapy for patients resistant to just one strategy.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A.J. Camm has received personal fees from Acesion, Anthos, Incarda, Milestone, Abbott, Boston Scientific and Johnson and Johnson.

REFERENCES

1. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis:antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:857-867.

2. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation:a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383:955-962.

3. Ozaki AF, Choi AS, Le QT, et al. Real-World Adherence and Persistence to Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Patients With Atrial Fibrillation:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2020;13:005969.

4. Reddy VY, Doshi SK, Kar S, et al. 5-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure:From the PREVAIL and PROTECT AF Trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:2964-2975.

5. Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P, et al. 4-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Nonwarfarin Oral Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1-14.

6. Whitlock RP, Belley-Cote EP, Paparella D, et al. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion during Cardiac Surgery to Prevent Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2081-2091.

7. Jolly SS. Surgical Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion and Rationale for design of LAAOS IV. In:CRT 2023. 2023 Feb 25-28;Washington DC. Available at: https://phri.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/LAAOS-4_FDA-.pdf. Accessed 9 Apr 2025.

8. Amaro S, Cruz-González I, Estévez-Loureiro R, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion plus oral anticoagulation in stroke patients despite ongoing anticoagulation: rationale and design of the ADD-LAAO clinical trial. REC Interv Cardiol. 2025;7:140-145.

9. Korsholm K, Valentin JB, Damgaard D, et al. Clinical outcomes of left atrial appendage occlusion versus direct oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation and prior ischemic stroke:A propensity-score matched study. Int J Cardiol. 2022;363:56-63.

10. Abramovitz Fouks A, Yaghi S, Selim MH, Gökçal E, Das AS, Rotschild O, Silverman SB, Singhal AB, Kapur S, Greenberg SM, Gurol ME. Left atrial appendage closure in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute ischaemic stroke despite anticoagulation. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2025;10:120-128.

11. Cruz-González I, González-Ferreiro R, Freixa X, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke despite oral anticoagulation (resistant stroke). Results from the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2020;73:28-34.

12. Korsholm K, Damgaard D, Valentin JB, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion vs novel oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation:rationale and design of the multicenter randomized occlusion-AF trial. Am Heart J. 2022;243:28-38.

13. Maarse M, Seiffge DJ, Werring DJ, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion vs standard of care after ischemic stroke despite anticoagulation. JAMA Neurol. 2024;81:1150–1158.

14. Kapadia SR, Yeh RW, Price MJ, et al. Outcomes With the WATCHMAN FLX in Everyday Clinical Practice From the NCDR Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:013750.

We have been treating patients with severe aortic stenosis and low surgical risk using transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for quite a few years, and the proportion of patients with this profile treated with this option is increasingly higher.1 However, the rapid expansion of this technique is unfolding with relevant unknowns that are still under investigation,2 such as the risk of infective endocarditis (IE)—a rare yet serious complication. In a study recently published in REC: Interventional Cardiology, Barreiro et al.3 investigated the actual incidence and prognosis of IE in this context compared with patients undergoing conventional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) with a biological prosthetic valve.

In the study, the direct comparison between the incidence of IE in patients undergoing TAVI and those treated with SAVR shows that the rate is very similar across groups (1.29% in TAVI vs 1.64% in SAVR).3 This incidence—although low—is higher than that reported in studies conducted with low-risk patients, such as the NOTION trial (0.5% in TAVI vs 0.8% in SAVR at 5.6 years) and the PARTNER 3 trial (0.4% in TAVI vs 0.6% in SAVR at 3 years).4,5 On the other hand, the authors report a similar rate of surgical procedures performed in both groups and an equally similar overall mortality rate. These findings contrast with previous reports that suggested a lower indication for surgery in patients undergoing TAVI with IE complications,6 but also lower mortality rates in the TAVI group (at 1 year, 27.3% in the TAVI group [95% confidence interval, 1-53.6%] vs 51.8% in the SAVR group [95% confidence interval, 28.2-75.3%]).7

To interpret these discrepancies with former studies, it is essential to consider the differences in the patients’ baseline profile. One of the most relevant aspects is the significant disparity across the groups in terms of age, comorbidities, and surgical risk profile. Patients undergoing TAVI were considerably older than those treated with SAVR (76 vs 63 years; P < .001), which per se increases the risk of complications, including IE. Additionally, TAVI patients had a higher prevalence of diabetes (70% vs 29%; P = .034), which is a known risk factor for contracting IE and having a worse prognosis.8-10 Although Barreiro et al.3 clarify that TAVI was performed in patients with significantly higher EuroSCORE II scores no full adjustment was made for these differences when studying the rate of IE. Therefore, SAVR patients were generally younger and had a lower comorbidity burden, which could have influenced a higher reintervention rate and reduced IE mortality, not necessarily attributed to the type of intervention per se. This suggests that the similar rates of IE and its intervention, as well as similar prognoses, might not hold true if populations were truly comparable. Differences with other studies may also be due, as the authors acknowledge,3 to the small number of patients analyzed.

The study also addresses the characteristics of IE in patients unergoing TAVI and SAVR, highlighting that a significant proportion of early IE (around 50%) was observed in the 2 groups. In this regard, there are several differential nuances that should be taken into consideration:

-

–The possibility of infection in the early stages after TAVI could be related to valve manipulation during implantation, not always under the same sterile conditions as in the operating room.

– Transfemoral access per se could expose patients to certain colonizing pathogens, such as enterococci, which are currently the most common in IE in TAVI carriers—but not after SAVR—in most series.

– Post-TAVI manipulations are different and could act as an entry point. Although generally minimally invasive, certain surgical procedures—such as pacemaker implantation—are more frequent, and TAVI is increasingly performed in patients with active gastrointestinal oncological processes, which are a predisposing factor for very characteristic IE-causing microorganisms.

– Finally, the above-mentioned worse profile of TAVI patients, with older age and presence of comorbidities—particularly diabetes mellitus—are factors favoring IE by increasing susceptibility to infections.

The fact that these patients are more prone to infectious complications means that direct comparison with younger, less comorbid patients undergoing SAVR should be interpreted with caution without proper adjustment for these factors.

In conclusion, the study by Barreiro et al.3 provides valuable data on the rate of IE in patients undergoing TAVI vs SAVR. The lack of a difference-adjusted analysis in the baseline characteristics between the 2 groups is per se a limitation that should not be overlooked. Differences in age, comorbidity prevalence, and baseline surgical risk may have significantly influenced the results obtained. The incidence of IE is, in part, a reflection of the patients’ underlying risk, and not just the type of surgery performed, which is why the results of this study should be interpreted with caution.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Castrodeza J, Amat-Santos IJ, Blanco M, et al. Propensity score matched comparison of transcatheter aortic valve implantation versus conventional surgery in intermediate and low risk aortic stenosis patients:A hint of real-world. ardiol J. 2016;23:541-551.

2. Amat-Santos IJ, Díez-Villanueva P, Diaz JL. Post-TAVI outcomes:devil lies in the details. Aging (Albany NY). 2019;11:9221-9222.

3. Barreiro L, Roldán A, Aguayo N, et al. Infectious endocarditis on percutaneous aortic valve prosthesis:comparison with surgical bio-prostheses. REC Interv Cardiol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M24000489.

4. Thyregod HGH, Jørgensen TH, Ihlemann N, et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic valve implantation:10-year outcomes of the NOTION trial. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1116-1124.

5. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients at Five Years. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1949-1960.

6. Amat-Santos IJ, Messika-Zeitoun D, Eltchaninoff H, et al. Infective endocarditis after transcatheter aortic valve implantation:results from a large multicenter registry. irculation. 2015;131:1566-74.

7. Lanz J, Reardon MJ, Pilgrim T, et al. Incidence and Outcomes of Infective Endocarditis After Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e020368.

8. Abramowitz Y, Jilaihawi H, Chakravarty T, et al. Impact of Diabetes Mellitus on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:1636-1642.

9. van Nieuwkerk AC, Santos RB, Mata RB, et al. Diabetes mellitus in transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation:a propensity matched analysis. ardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21:246.

10. García-Granja PE, Amat-Santos IJ, Vilacosta I, Olmos C, Gómez I, San Román Calvar JA. Predictors of Sterile Aortic Valve Following Aortic Infective Endocarditis. Preliminary Analysis of Potential Candidates for TAVI. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:428-430.

INTRODUCTION

The European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) was founded back in 2006 from the former European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Working Group on Interventional Cardiology. Within the ESC, and as 1 of 7 different sub-specialties associations, EAPCI mission is specifically aimed at reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease through percutaneous cardiovascular interventions.

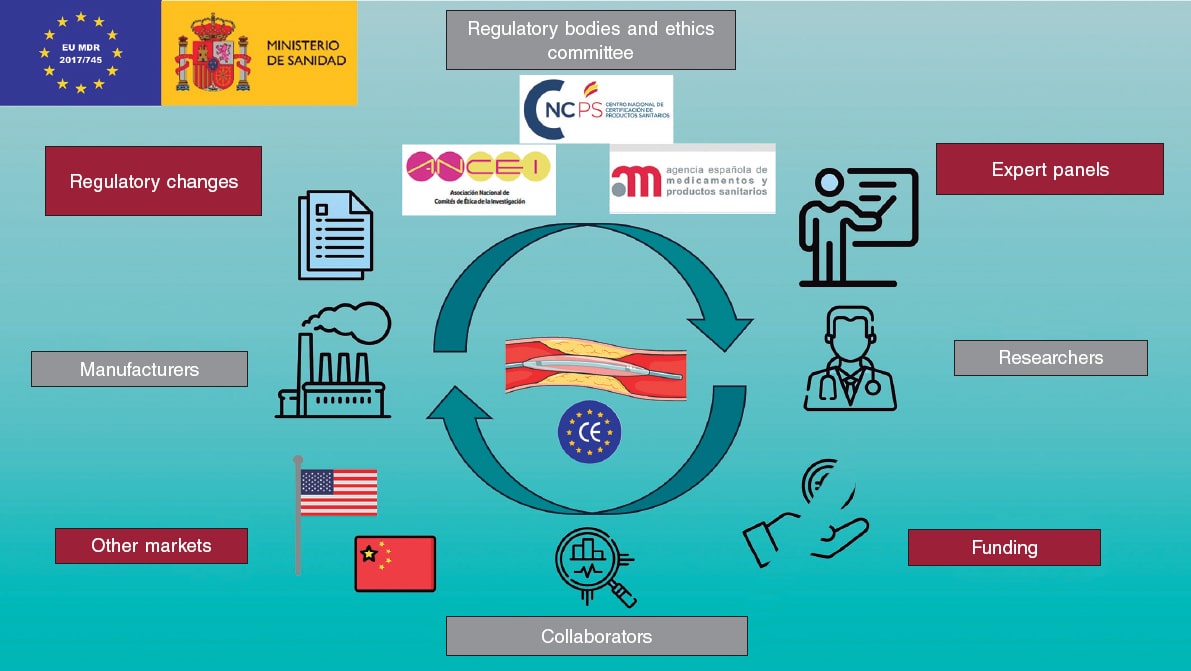

EAPCI empowers interventional cardiologists through a robust network of resources specifically designed to meet the demands of contemporary practice. In the following sections, we will outline the key benefits of EAPCI membership across several domains, including science, content, education, advocacy, and collaboration (figure 1). Each of these pillars contributes to a framework that not only keeps members at the cutting edge of interventional cardiology, but also fosters collaboration with national working groups and societies to move the field forward collectively.

Figure 1. Why join the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI)?

By highlighting these core advantages, we hope we can underscore the true value of EAPCI membership in helping interventional cardiologists navigate the current fast-paced clinical environment and drive the future of interventional cardiology to improve daily clinical practice and scientific projects.

SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES CONDUCTED BY EAPCI

EAPCI scientific documents provide guidance for the clinical management of topics not covered in the ESC clinical practice guidelines complementing them by providing more in-depth information in specific areas that cannot be expanded upon in the guidelines.

EAPCI produces scientific documents and consensus statements specific to the domain of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions and in collaboration with other ESC associations, councils and working groups on topics overlapping among the different subspecialties and with affiliated countries (ie, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions, SCAI). A dedicated EAPCI website grants access to all EAPCI consensus documents and EAPCI position papers (2009-2024).1

The 2022-2024 EAPCI Scientific Documents Committee conducted extensive work developing new standard operating procedures that have, recently, been more widely adopted by the ESC Scientific Documents Committee. These new standard operating procedures guarantee that all EAPCI members can participate in the drafting of these documents. In addition, to guarantee inclusivity a balance between geographies and sex is guaranteed.

CONTENT CREATED BY EAPCI

The aim of the unique EAPCI Journal Club format is to provide a true valuable platform for disseminating recent clinical trials, fostering discussions on clinical implications, and guiding the integration of new data into clinical practice. The discussion of recent clinical trials addresses different aspects of cardiovascular interventions and pharmacotherapy, offering insights into cutting-edge therapeutic strategies and evolving standards of care.

The EAPCI Journal Club enables attendees to engage directly with principal investigators of the clinical trials and clarify clinical questions.

By promoting interaction among global experts, EAPCI webinars are tailored to the latest advances and best practices in cardiovascular interventions. The webinars serve as a link between research and clinical application. All content is available on demand on the EAPCI official website2 and the ESC365 platform for EAPCI members at any time.3

EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES BY EAPCI

EAPCI offers comprehensive educational resources to support professionals in interventional cardiology.

EAPCI Certification is an exam designed to assess knowledge and skills in percutaneous cardiovascular interventions. Earning this certification is a significant accomplishment for professionals, as it verifies a high level of competence and dedication in interventional cardiology. For nurses and health care support specialists, achieving such a certification provides career advancement opportunities, enhances confidence in clinical practice, and solidifies their role in a multidisciplinary care team.

EAPCI online courses are another key offering providing structured, modular learning opportunities for participants to explore specific topics at their own pace. These courses include interactive elements, such as case studies and assessments, reinforcing knowledge and promoting practical understanding. For nurses and health care support specialists, online courses focus on essential areas such as perioperative care, device management, and complication prevention, providing them with essential, job-specific skills to improve patient outcomes.

Altogether, EAPCI Certification, EAPCI webinars, and EAPCI online courses foster a supportive and enriching learning environment empowering nurses and health care support specialists to expand their knowledge, achieve certifications, and deliver high-quality, patient-centered cardiovascular care.

In addition, EAPCI is further expanding its educational offers through an agreement signed between the ESC and Europa Group. EAPCI official courses are EuroPCR, the EAPCI PCR Fellows Course, and PCR London Valves. The official textbook is the PCR-EAPCI Textbook4 and EuroIntervention5 is EAPCI official journal.

Advocacy provided by EAPCI

In terms of advocacy, the key objectives of EACPI are to understand and overcome barriers preventing patients from receiving the appropriate diagnostics and treatment, and evaluate and improve patient experience during interventional procedures.

To achieve the first goal, the ATLAS in Interventional Cardiology has been developed as the landmark project, allowing comparisons across different contemporary interventional cardiology practices in multiple ESC countries and the use of this information when negotiating reimbursement policies with national regulatory bodies. Data collection started in 2016 and the first report was published in 20206 mainly on human resources, infrastructure and procedural volumes.

To achieve the second goal, the Patient Experience in the Catheterization Laboratory (PATCATH) tool,7 patient information videos8 and Valve for Life initiative9 have been launched in collaboration with the EACPI Patient Engagement Committee. The PATCATH tool has been developed to try to understand and improve the patients’ experience while undergoing interventional cardiology procedures and is now fully available in 10 different languages. In addition, 5 patient information videos on percutaneous cardiovascular interventions have been produced to help patients understand these procedures, which remain available for use by EAPCI members in English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish. The use of PATCATH demonstrated that patient understanding of common cardiovascular procedures may be suboptimal.7,10 In turn, patients who were shown a dedicated video animation prior to the procedure tended to have more positive informational experience.11

Finally, the Valve for Life initiative launched in 2015 aims to improve transcatheter aortic and atrioventricular valve interventions across Europe to raise awareness, facilitate access to transcatheter heart valve interventions and, last but not least, reduce age and gender discrimination regarding access to health care.9 Recently, a survey has been distributed to all national societies to identify current gaps in structural valve procedires to identify the countries and topics that should be addressed in the next edition.

EACPI INITIATIVES FOR THE YOUNG

Identificating and addressing the needs of the young community is one of the key EAPCI goals. Currently, almost 50% of all EAPCI members are younger than 40 years and 25% are in training.

The EAPCI Young Committee has identified networking, education and mentoring as the priorities for 2024-2026. The networking opportunities for young EAPCI members include the possibility to participate in joint sessions during national society congresses, expand collaboration with other ESC associations, working groups, and affiliated countries.

In terms of education, young EAPCI members have access to online educational resources, including a step-by-step video library created for early career interventional cardiologists.

Two programs are dedicated to young members:

- The 12-month EAPCI Online Coaching Program that promotes the personal development of young interventional cardiologists with practical, research and personal development tips in a one-to-one mentor-mentee relationship. The upcoming coaching program includes further development of the existing mentorship program and will include more mentors among the EACPI members on interventional skills and career development (“leadership accelerator”) and create mentorship for very early career colleagues and even students with young mentors (“young to young”).

- The Education and Training Grant program provides an opportunity for clinical training in the interventional cardiology field in a country from ESC National Cardiac Societies other than their own. The goal of this grant is to help young candidates attain clinical competence with hands on activities and acquire experience on high-quality cardiological clinical practice to contribute to improving academic and clinical standards upon return to their own country. The number of grants has increased in the last term.

To underline the valuable contribution of young members, EACPI introduced a 50% reduced membership fee of €75/year for people younger than 40 years.

EAPCI-EMPOWERED COLLABORATION

ESC National Cardiac Societies are the founders and principal constituent bodies of the ESC. Currently, there are 58 national cardiac societies.12 As institutional members they pay a membership fee and vote to help shape the future of cardiology and drive ESC activities. They are also instrumental in ESC research, dissemination of clinical practice guidelines and a wide range of other activities.

The presidents, or their official representatives, make up the EAPCI National Cardiac Societies Committee whose aim is to promote interactions across countries and help understand the diverse needs of different geographical areas to foster collaboration. For example, in collaboration with the German Interventional Working Group (AGIK) EAPCI became a cooperation partner in a 2-day Complete Higher Risk Indicated Percutaneous Coronary Intervention course held in Berlin in 2024 called AGIK CHIP International. Many joint sessions have recently been held at various national society congresses, including the Romanian Society of Cardiology, APIC (Associação Portuguesa de Intervenção Cardiovascular), and GISE (Società Italiana di Cardiologia Interventistica).

With EAPCI global scope collaborative relationships with many ESC Affiliated Cardiac Societies,13 for the first time, an EAPCI International Committee was established for 2024-2026 whose plan is to build bridges and promote global collaborations through joint sessions in congresses and courses, creating scientific documents and preparing webinars together.

An agreement has already been reached with the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions (SCAI) with a joint session at the SCAI meeting in 2024 and 2 scientific documents with collaboration between SCAI and EAPCI are already being drafted. A joint session between EAPCI and the Latin American Society of Interventional Cardiology (SOLACI) was held in Buenos Aires (Argentina) in 2024 demonstrating the importance of global collaboration and education to achieve common goals. More collaborative events and scientific projects are in the pipeline with other affiliated countries.

THEN, WHY JOIN EAPCI?

EAPCI serves as a vital platform for interventional cardiologists to address the challenges of a rapidly evolving medical landscape. By offering access to cutting-edge scientific content, innovative educational opportunities, and robust collaborative networks, EAPCI provides its members with tools to stay at the forefront of interventional cardiology. From contributing to the development of groundbreaking scientific documents and consensus statements to leveraging platforms such as the Journal Club and ESC365 for continuous learning, EAPCI ensures its members are prepared to deliver optimal patient care. Additionally, advocacy initiatives such as the ATLAS project and Valve for Life underline EAPCI commitment to improving access to cardiovascular interventions across Europe and beyond. In addition, it provides an ideal platform for early career doctors and those in training to have access to educational offers, a one-to-one coaching program, fellowship grants providing access to an international network to become the future leaders of tomorrow. The EAPCI membership not only fosters professional growth but also strengthens global collaboration, making it an essential step for those wishing to lead and innovate in the field of interventional cardiology. Join EAPCI and become a member by scanning the QR code (figure 2) to access these benefits and help shape the future of our specialty.

Figure 2. EAPCI membership QR code.

FUNDING

None declared.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

E. Rafflenbeul is chair of the EAPCI Educational Content, Courses and Webinars Committee (2024-2026). M. Iannaccone is chair of the EAPCI Young Committee (2024-2026). A. Gasecka is co-chair of the EAPCI Young Committee (2024-2026). N. Ryan is chair of the EAPCI Online and Communication Committee (2024—2026). A. Chieffo is EAPCI president (2024-2026).

REFERENCES

1. European Society of Cardiology. Consensus and Position Papers on Interventional Cardiology - European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Available at: http://www.bit.ly/EAPCIConsensusPositionPapers. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

2. European Society of Cardiology. EAPCI Journal Club. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/Sub-specialty-communities/European-Association-of-Percutaneous-Cardiovascular-Interventions-(EAPCI)/Education/eapci-journal-club. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

3. ESC 365. EAPCI Webinars and Journal Clubs. Available at: https://bit.ly/EAPCIatESC365. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

4. The PCR-EAPCI Textbook. Available at: https://textbooks.pcronline.com/the-pcr-eapci-textbook. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

5. Eurointervention. Available at: https://eurointervention.pcronline.com. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

6. Barbato E, Noc M, Baumbach A, et al. Mapping interventional cardiology in Europe:the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) Atlas Project. Eur Heart J. 2020:41:2579–2588.

7. Wilson H, Brenan M, Rai H, et al. Initial experience and validation of a novel tool to assess patient experience in the catheterization laboratory (PATCATH), in patients undergoing coronary angiography or angioplasty. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2022;21(Suppl 1):zvac060.030.

8. European Society of Cardiology. EAPCI Patient Resources. Available at: https://bit.ly/EAPCIPatientResources. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

9. Windecker S, Haude M, Baumbach A. Introducing a new EAPCI programme:the Valve for Life initiative. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:977-979.

10. Fitzgerald S, Wilson H, Brenan M, et al. Initial findings with the PATient experience in the CATH Lab (PATCATH) patient-reported experience metric. EuroIntervention. 2023;19:e860-e862.

11. Kenny Byrne K, Colleran R, Rai H, et al. Impact of administration of EAPCI patient video animation versus standard patient information leaflets on patient experience in the catheterization laboratory assessed using the PATCATH questionnaire. Heart.2023;109:A49-A50.

12. European Society of Cardiology. ESC National Cardiac Societies. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Member-National-Cardiac-Societies. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

13. European Society of Cardiology. ESC Affiliated Cardiac Societies. Available at: https://www.escardio.org/The-ESC/Affiliated-Cardiac-Societies. Accessed 25 Nov 2024.

INTRODUCTION

Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) refers to the treatment of high-risk plaque before the occurrence of any adverse events. Typically, the decision to perform preventive treatment is made when the expected event rate of the underlying condition outweighs the potential short- and long-term complications of the procedure. This approach is also applicable to the treatment of coronary disease. In recent years, advances in understanding atherosclerotic plaque progression and identifying high-risk plaques, along with technological progress in coronary devices, have shifted the balance between the risks of the underlying condition and those of percutaneous treatment.

THE CONCEPT OF VULNERABLE PLAQUE

The understanding of high-risk coronary plaques, also known as vulnerable plaques, has evolved over the years. Initially, a vulnerable plaque was often considered an angiographically nonsignificant stenosis that was prone to rupture and cause acute coronary syndrome.1 The PROSPECT study was the first landmark trial to focus on the natural history of vulnerable plaques, assessed using intravascular ultrasound with virtual histology.2 This trial was the first to define specific criteria for plaque vulnerability, notably thin-cap fibroatheroma (TCFA). TCFA is characterized by a lipid-rich plaque with a necrotic core, separated from the vessel lumen by a thin fibrotic cap. The trial also identified 2 other quantitative criteria: a plaque burden > 70% and a minimum lumen area (MLA) < 4.0 mm2. Despite its major contributions, the study had limitations: a) the resolution of intravascular ultrasound with virtual histology was not sufficient to detect the cap thickness ≤ 0.65 µm (cutoff value for true TCFA), and b) the trial could not exclude the absence of ischemia in lesions that led to events.

THIN-CAP FIBROATHEROMA

The use of more sophisticated imaging modalities, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), which has a resolution of 10 to 20 µm and is therefore able to detect TCFA, has paved the way for the true detection of vulnerable plaque. Indeed, the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial,3 a natural history study that compared the outcomes of nonischemic lesions, categorized as TCFA or non-TCFA based on OCT assessment, showed for the first time that even in the absence of ischemia, the presence of an OCT-assessed TCFA was associated with a 4-fold higher event rate compared with lesions without TCFA. This trial provided evidence that the morphological features of a lesion might be more important than ischemia in predicting future adverse events, opening the door to the potential treatment of nonischemic lesions.

Interestingly, our group has also shown that TCFA, rather than any lipidic plaque, is associated with future adverse events, while lipidic plaques with a thick cap have a benign outcome comparable to that of fibrotic plaques. This finding suggests that only about a third of all lipidic plaques and less than a quarter of all plaques might benefit from pre-emptive treatment.4 Other studies, such as CLIMA5 and PECTUS,6 have corroborated the role of TCFA in predicting future adverse events. Similarly, Kubo et al.7 have also shown that the presence of TCFA is associated with a high rate of future adverse events.

VULNERABLE PLAQUE NEW CONCEPTS

Recent studies have demonstrated that, contrary to previous beliefs, vulnerable plaques that lead to future adverse events typically have a large plaque volume and show a significant degree of luminal stenosis. COMBINE OCT-FFR and the FORZA trial8 both independently found that an MLA cutoff of 2.5 mm2 was a better predictor of future adverse events than the previously considered 4.0 mm2.

In addition to MLA, other plaque features are associated with vulnerability. A recent post hoc analysis from the COMBINE OCT-FFR study9 showed that, beyond MLA, other signs of plaque destabilization adjacent to TCFA, such as old plaque ruptures or healed plaques, are associated with a significantly increased rate of adverse events. When vulnerability features coexist, the event rate can progressively increase. For example, while TCFA alone was associated with a 20% future adverse event rate, a combination of TCFA with MLA < 2.5 mm2 adjacent to a healed plaque was associated with an event rate of 50%.

These findings are important as they introduce a new way of thinking about vulnerable plaques. The concept has shifted from a simple yes/no binary to a variable and progressive model. In this model, the vulnerability of a plaque increases based on the number of high-risk features present, with the most vulnerable plaques being those with more than 3 risk factors.

The notion that a plaque that ruptures without causing an acute event will heal and stabilize has also been challenged. “Healed” plaques often do not represent stable plaques but are prone to new ruptures in adjacent locations, making them one of the strongest predictors of vulnerability. Araki et al.10 have very nicely shown that multiple repeat plaque ruptures and healings are the true mechanisms behind atherosclerosis progression.

It is understandable that growth in the volume of intraluminal plaque parallels ischemia progression, as plaque progression will eventually lead to ischemic lesions. However, it is important to recognize that, based on this rupture and healing model of plaque progression, any future destabilization (rupture and/or healing) of a plaque with vulnerable features—whether angiographically borderline or already significant but not yet ischemic—could result in either an acute coronary syndrome or rapid progression (from one day to the next) of luminal stenosis, leading to ischemia and likely stable or unstable angina.

Based in this rationale, revascularization based on OCT imaging, which has the potential to detect these plaques, becomes an appealing strategy, rather than relying solely on ischemia-guided intervention. The FORZA trial was the first to show a benefit for imaging-guided PCI vs ischemia-guided PCI. However, the trial used only quantitative OCT criteria rather than a combination of quantitative and qualitative OCT vulnerability criteria. As explained above, the benefit of OCT guidance lies in its ability to identify lesions with a high degree of vulnerability that do not yet cause symptoms, thereby paving the way for preventive PCI.

IMPROVED PCI OUTCOMES

Improvements in stent technology, PCI techniques, and intravascular imaging guidance have led to very low complication rates with PCI, especially in nonseverely stenosed lesions. The PREVENT trial,11 which compared a medical therapy vs PCI in lesions with a diameter stenosis of ≥ 50% but which were otherwise nonischemic, showed very low event rate in the PCI arm (< 1%). This suggests that PCI can currently provide lower event rates than medical therapy for these high-risk vulnerable lesions.

IMPROVING THE CURRENT REVASCULARIZATION STRATEGY BY INTEGRATING A PREVENTIVE VULNERABLE PLAQUE INTERVENTION

Interestingly, while at first glance, an approach similar to that of the PREVENT trial might seem to open the door to stenting all intermediate lesions, the reality is different. The ability of OCT to detect truly vulnerable features has significantly limited the number of lesions that might benefit from preventive PCI. In patients without ischemia but with a lesion that has a diameter stenosis of more than 50%, the prevalence of vulnerable lesions according to OCT criteria may range between 10% and 20% compared with > 90% in the PREVENT trial.

On the other hand, large trials like ISCHEMIA12 and FAME 2,13 have shown that approximately 20% of patients with ischemic lesions are unresponsive to medical treatment and require PCI to control angina symptoms. Interestingly, this 20% corresponds to the percentage of truly ischemic lesions, defined as having a fractional flow reserve (FFR) of < 0.75.14 Therefore, it can be deduced that there is still a role for ischemia detection and revascularization of these lesions with true ischemia (FFR < 0.75), regardless of the presence of vulnerability features. Meanwhile, the role of preventive PCI could be reserved for plaques with highly vulnerable features that show at least an intermediate degree of stenosis but are otherwise nonischemic.

If such a combined decision-making strategy is correctly applied, the number of lesions that may benefit from PCI treatment could be similar to or even lower than those identified through the current ischemia-driven revascularization strategy alone. Indeed, with this new combined strategy, the only lesions requiring PCI would be those with true ischemia (FFR ≤ 0.75), which represent about 20% of lesions, and those with high-risk vulnerable plaque, which represent another 10% to 20% of all lesions. This compares with the 40% of lesions that currently undergo PCI based on an ischemia-driven revascularization strategy (FFR ≤ 0.80).

This combined FFR- and OCT-guided treatment strategy in patients with multivessel disease (lesions with angiographic stenosis > 50%) presenting with stable or acute coronary syndromes is now being tested in the COMBINE-INETREVENE trial (NCT05333068), a global randomized controlled trial. This new strategy involves reserving PCI to lesions with an FFR of ≤ 0.75, as well to to all lesions with an FFR > 0.75 that show vulnerable features such as TCFA, ruptured plaque, or plaque erosions with significant lumen reduction (MLA < 2.5 mm2).

Another trial implementing a purely preventive percutaneous treatment is the VULNERABLE trial (NCT05599061), an ongoing multicenter study in Spain that tests a similar concept but focuses solely on nonischemic, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction nonculprit lesions with high-risk vulnerable features. We believe that the results of these trials, as well as new imaging technologies that could lead to automatic detection of vulnerable plaques, combined imaging and hemodynamic assessment modalities, and improved intracoronary treatment devices (whether implantable or not), will provide new insights into the role of preventive PCI.

FUNDING

There was no funding for this manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

E. Kedhi has received institutional research grants from Medtronic and Abbott and is a proctor for Abbott.

REFERENCES

1. Virmani R, Burke AP, Farb A, Kolodgie FD. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C13-C18.

2. Stone GW, Maehara A, Lansky AJ, et al. PROSPECT Investigators. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226-235.

3. Kedhi E, Berta B, Roleder T, Hermanides RS, et al. Thin-cap fibroatheroma predicts clinical events in diabetic?patients with normal fractional flow reserve:the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4671-4679.

4. Fabris E, Berta B, Roleder T, et al. Thin-Cap Fibroatheroma Rather Than Any Lipid Plaques Increases the Risk of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetic Patients:Insights from the COMBINE OCT-FFR Trial. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:011728.

5. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Gatto L, et al. Relationship between coronary plaque morphology of the left anterior descending artery and 12 months clinical outcome:the CLIMA study. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:383-391.

6. Mol JQ, Volleberg RHJA, Belkacemi A, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve-Negative High-Risk Plaques and Clinical Outcomes After Myocardial Infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;8:1013-1021.

7. Kubo T, Ino Y, Mintz GS, Shiono Y, Optical coherence tomography detection of vulnerable plaques at high risk of developing acute coronary syndrome. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021:jeab028.

8. Burzotta F, Leone AM, Aurigemma C, et al. Fractional Flow Reserve or Optical Coherence Tomography to Guide Management of Angiographically Intermediate Coronary Stenosis:A Single-Center Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:49-58.

9. Del Val D, Berta B, Roleder T, et al. Vulnerable plaque features and adverse events in patients with diabetes mellitus:a post hoc analysis of the COMBINE OCT-FFR trial. EuroIntervention. 2024;20:707-717.

10. Araki M, Yonetsu T, Kurihara O, et al. Predictors of Rapid Plaque Progression:An Optical Coherence Tomography Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;14:1628-1638.

11. Park SJ, Ahn JM, Kang DY, et al. PREVENT Investigators. Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy alone for the treatment of vulnerable atherosclerotic coronary plaques (PREVENT):a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024;403:1753-1765.

12. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1395-1407.

13. De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. FAME 2 Trial Investigators. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991-1001.

14. Davies JE, Sen S, Dehbi HM, et al. Use of the Instantaneous Wave-free Ratio or Fractional Flow Reserve in PCI. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1824-1834.

- Percutaneous coronary intervention of the left main in the elderly: a reasonable option

- The challenging pathway to TAVI: in memory of Alain Cribier

- Clinical evaluation requirements under the new European Union medical device regulation

- Misconceptions and misunderstandings hampering medical research and progress

Subcategories

Special articles

Original articles

Editorials

Original articles

Editorials

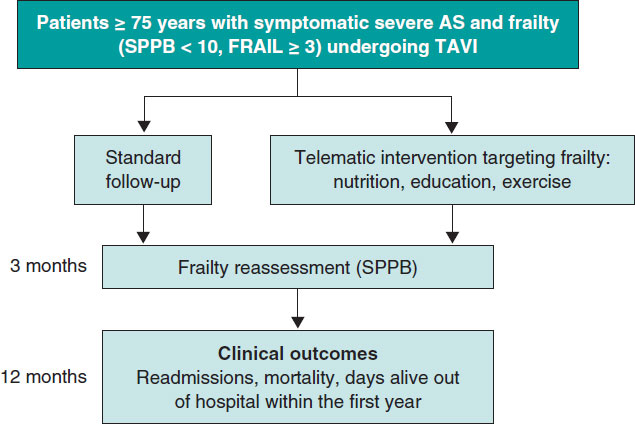

Post-TAVI management of frail patients: outcomes beyond implantation

Unidad de Hemodinámica y Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital General Universitario de Elche, Elche, Alicante, Spain

Original articles

Debate

Debate: Does the distal radial approach offer added value over the conventional radial approach?

Yes, it does

Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Sant Joan d’Alacant, Alicante, Spain

No, it does not

Unidad de Cardiología Intervencionista, Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Galdakao, Galdakao, Vizcaya, España