ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Mitral regurgitation is one of the most common heart valve diseases. Valve replacement surgery is a guideline-recommended option; however, in a significant proportion of patients, this option is not feasible. In such cases, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) is a potential therapeutic alternative. Nevertheless, the results of a randomized clinical trial have shown divergent results. Recently, the results of the RESHAPE-HF2 trial were published, providing additional insights. The objective of this work is to evaluate whether there are any differences between performing M-TEER and keeping patients under guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).

Methods: We conducted a meta-analysis following the PRISMA guidelines. We searched for studies across the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases until February 2025. We establish the following inclusion criteria: patients with secondary mitral regurgitation, studies comparing M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone, and who reported hospitalization due to heart failure (HF) or mortality.

Results: A total of 3 randomized clinical trials meet the inclusion criteria, including a total of 1423 patients: 704 received M-TEER and 719, GDMT alone. M-TEER was associated with a reduced risk of HF-related hospitalization with a risk ratio (RR) of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.56-0.90; P = .004). We did not find any differences in all-cause mortality with a RR of 0.80 (95%CI, 0.63-1.02; P = .07).

Conclusions: In this meta-analysis, M-TEER plus GDMT shows a lower risk of HF-related hospitalization vs GDMT alone. We did not find any differences in the risk of all-cause mortality or cardiac death.

Registered at PROSPERO: CRD42025645047.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation. Mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. Heart failure. M-TEER.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La regurgitación mitral es una de las valvulopatías cardiacas más comunes. La cirugía de reemplazo valvular es una opción recomendada por las guías clínicas. Sin embargo, en un porcentaje significativo de pacientes, esta opción no es viable. En estos casos, la reparación mitral percutánea de borde a borde (M-TEER) es una posible alternativa terapéutica. No obstante, los resultados de los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados han mostrado resultados divergentes. Recientemente se han publicado los resultados del estudio RESHAPE-HF2, que aportan información adicional sobre este tema. El objetivo de este trabajo fue evaluar si existen diferencias entre realizar M-TEER o mantener a los pacientes bajo tratamiento médico según las guías clínicas (TMSG).

Métodos: Se realizó un metanálisis siguiendo las guías PRISMA. Se buscaron estudios en las bases de datos PubMed, Embase y Cochrane hasta febrero de 2025. Se establecieron los siguientes criterios de inclusión: pacientes con insuficiencia mitral secundaria, estudios que comparaban M-TEER más TMSG frente a solo TMSG, y que indicaran hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca o mortalidad.

Resultados: Tres ensayos clínicos aleatorizados cumplieron los criterios de inclusión, con un total de 1.423 pacientes, de los que 704 se trataron con M-TEER y 719 recibieron solo TMSG. La M-TEER se asoció con una reducción del riesgo de hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca con una razón de riesgo de 0,71 (IC95%, 0,56-0,90; p = 0,004). No se encontraron diferencias en cuanto a muerte por cualquier causa, con una razón de riesgo de 0,80 (IC95%, 0,63-1,02; p = 0,07).

Conclusiones: En este metanálisis, la M-TEER, en combinación con el TMSG, mostró una reducción del riesgo de hospitalización por insuficiencia cardiaca en comparación con el TMSG solo. No se hallaron diferencias en el riesgo de muerte por cualquier causa (muerte de causa cardiovascular o infarto agudo de miocardio).

Registrado en PROSPERO: CRD42025645047.

Palabras clave: Regurgitación mitral. Reparación percutánea de borde a borde. Insuficiencia cardiaca. M-TEER.

Abreviaturas

MR: mitral regurgitation. M-TEER: mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. GDMT: guideline-direct medical therapy. HF: heart failure. NYHA: New York Heart Association.

INTRODUCTION

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is a prevalent valvular heart disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality, particularly in patients with heart failure (HF).1 Traditional management strategies include optimal medical therapy to treat symptoms and surgery for definitive correction.2 However, current clinical practice guidelines only recommend mitral valve repair if the patient is undergoing another intervention such as coronary artery bypass graft or aortic valve replacement; nonetheless, many patients are at a high risk for surgery due to comorbid conditions, for this reason, alternative therapeutic options is required.3

Mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (M-TEER) has emerged as a minimally invasive option for patients with symptomatic mitral regurgitation who are ineligible for surgery.4 While M-TEER has shown promising results, its comparative efficacy vs guideline- directed medical therapy (GDMT) is still a matter of discussion.5

This meta-analysis aims to assess the impact of M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone on major clinical outcomes in patients with secondary MR. The primary endpoint evaluated was HF-related hospitalization. Secondary endpoints included all-cause mortality, cardiac death, improvement in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class (FC), and the incidence rate of stroke and myocardial infarction. These endpoints were selected for their clinical relevance and potential to inform therapeutic decision-making in this high-risk patient population.

METHODS

We conducted this meta-analysis in full compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement guidelines.6 All the stages of this study were performed following the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3.7 The protocol for this meta-analysis was registered prospectively in PROSPERO on 10 February 2025 with protocol ID CRD42025645047.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search across 3 electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, and COCHRANE) from inception until February 2025. Search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “transcatheter”, “secondary”, “mitral valve”, “replacement”, regurgitation”, and “insufficiency”. These keywords were combined using Boolean operators AND, OR. The reference lists of eligible studies and previous reviews were checked to identify additional valuable articles.

Criteria of the included studies

Studies were considered for inclusion in the meta-analysis based on the following criteria: a) randomized clinical trials (RCT) or observational cohort studies in Spanish or English that b) compared transcatheter mitral valve replacement vs optimal medical therapy in adult patients with mitral valve regurgitation due to secondary causes; and c) studies that reported outcomes of interest such as the index HF-related hospitalization, HF-related readmissions or cardiac death, and all-cause mortality.

Studies were excluded if they were non-original articles such as systematic reviews, letters, abstracts, meta-analyses, case reports, or case series. Furthermore, studies were excluded if mitral regurgitation was due to primary causes or if prior surgical repair had been performed.

Although observational cohort studies were eligible, we only identified 1 cohort study that did not meet the inclusion criteria during full-text screening. As a result, only RCTs were ultimately included in the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

To ensure accuracy, we used Zotero to eliminate duplicate references. We screened each paper based on title and abstract as a first step, followed by a full-text review as the second step. Two authors (D.A. Navarro Martínez, and D. Paulino-González) independently screened each paper, with any disagreements being resolved by a third author (A.L. García Loera). In addition, references of the included studies were reviewed and added if they met our eligibility criteria. Data extraction was conducted using Excel spreadsheets capturing the following information: a) baseline characteristics of the studied population, including baseline medication, echocardiographic baseline characteristics, and comorbidities; b) summary of the characteristics of the included studies; c) outcome measures; and d) quality assessment domains.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoints established for this meta-analysis included: a) all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR]), defined as all-cause mortality, assessed using time-to-event analysis,8 and b) HF-related hospitalization, defined as hospital admission for worsening HF following the intervention (M-TEER or initiation of optimal medical therapy).9

Secondary endpoints included a) stroke, defined as an episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal cerebral, spinal, or retinal infarction;10 and b) myocardial infarction, defined according to the Fourth Universal Definition.11

All endpoints were assessed as dichotomous categorical variables, which were reported in percentages. The risk ratio (RR) with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI) was calculated.

Assessment of heterogeneity

To assess heterogeneity, we used Cochrane’s Q-statistic with a significance level of P < .05. Additionally, the I²-statistic was used to quantify the proportion of variability due to heterogeneity, with values > 50% being considered indicative of high heterogeneity.12

Statistical analyses

To assess dichotomous data, we evaluated event frequencies and totals from each study group to calculate the RR and its 95%CI. Moreover, we obtained the HR and the 95%CI to calculate the standard error (SE).

The variables analyzed in this study were based on data reported in the original studies of the intention-to-treat principle. We implemented a random-effects model using the DerSimonian-Laird13 method to account for variability and allow comparison across studies. Given the limitations and strengths of this method, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method. Forest plots were utilized as a visual representation of the estimated outcomes.

Considering the differences in the populations included in the clinical trials, we conducted an additional exploratory analysis that focused on the RESHAPE-HF214 and COAPT15 trials for the primary endpoints by removing MITRA-FR16 from the analysis.

All statistical analyses, including the calculation of RR and SE, were conducted using RevMan V.5.4.1 software.

RESULTS

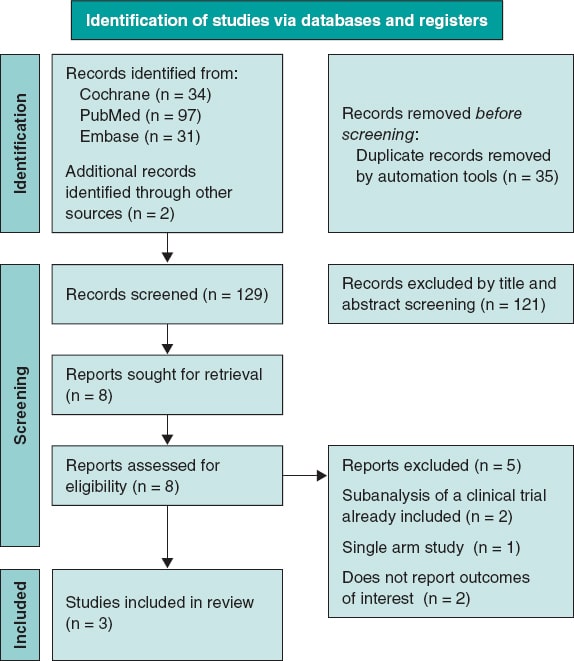

The initial database search yielded a total of 164 potentially relevant articles. After removing duplicates, a total of 129 articles finally remained for title and abstract screening. Following this initial screening, 8 articles were identified as potentially eligible for full-text review. Finally, after a detailed evaluation of the full texts under the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 3 studies were included. A summary of the study selection process is shown in the PRISMA flowchart figure 1.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only.

Our analysis included 3 RCTs.14-16 We consulted the extended report of the 2-year outcomes of the MITRA-FR trial17 and 1 additional article on the RESAHPE-HF2 to obtain more data regarding hospitalization.18 All included studies compared the use of M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone. To standardize the outcomes, the median follow-up was set at 24 months; only the NYHA FC was evaluated with 1-year results. All 3 included studies used the MitraClip (Abbott, United States) device.

Clinical baseline characteristics of the patients

We obtained a total population of 1423 patients; among them 704 received M-TEER and 719, GDMT alone. In the RESHAPE-HF214 the device group showed the following characteristics: mean age was 70 years old; left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), 32%; median left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), 200 mL; median effective regurgitation orifice (EROA), 0.23 cm2; median N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), 2651; and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), 556. In the COAPT15 trial, median age was 71 years old; LVEF, 31%; LVEDV, 194 mL; median EROA, 0.41 cm2; median NT-proBNP, 5174; and BNP, 1014. Finally in the MITRA-FR trial16, mean age was 71 years old; LVEF, 33%; LVEDV, 136.2 mL; median EROA, 0.31 cm2; median NT-proBNP, 3407; and BNP, 765. Regarding etiology, all trials enrolled mixed ischemic and non-ischemic etiology populations. Patient and study baseline characteristics, including comorbidities, drugs, and echocardiographic data, are shown in table 1, table 2, and table 3.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of patients

| Reference | Groups | N | Age | AF or flutter | Diabetes | Previous MI | Nonischemic etiology | Ischemic etiology | 6-min walk distance | Beta- blocker | ACEI | ARB | ARNI | SGLT2i | MRA | Diuretics | Oral anti- coagulants | BNP | NT-proBNP | EuroSCORE II |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RESHAPE-HF214 | M-TEER | 250 | 70.0 ± 10.4 | 118 (47.2) | 91 (36.4) | 144 (57.6) | 88 (35.2) | – | 300 (220-382) | 238 (95.2) | 142 (56.8) | 51 (20.4) | 40 (16.0) | 24 (9.6) | 200 (80.0) | 239 (95.6) | 163 (65.2) | 556 (312-1018) | 2651 (1630-4918) | 5.3 (2.7-8.9) |

| Optimal medical therapy | 255 | 69.4 ± 10.7 | 125 (49.0) | 85 (33.3) | 135 (52.9) | 88 (34.5) | – | 310 (200-378) | 246 (96.5) | 142 (55.7) | 45 (17.6) | 28 (11.0) | 22 (8.6) | 215 (84.3) | 243 (95.3) | 152 (59.6) | 406 (231-874) | 2816 (1306-5496) | 5.3 (2.9-9.0) | |

| COAPT15 | M-TEER | 302 | 71.7 ± 11.8 | 173 (57.3) | 106 (35.1) | 156 (51.7) | 118 (39.1) | 184 (60.9) | 261.3 ± 125.3 | 275 (91.1) | 138 (45.7) | 66 (21.9) | 13 (4.3) | NR | 153 (50.7) | 270 (89.4) | 140 (46.4) | 1014.8 ± 1086.0 | 5174.3 ± 6566.6 | NR |

| Optimal medical therapy | 312 | 72.8 ± 10.5 | 166 (53.2) | 123 (39.4) | 160 (51.3) | 123 (39.4) | 189 (60.6) | 246.4 ± 127.1 | 280 (89.7) | 115 (36.9) | 72 (23.1) | 9 (2.9) | NR | 155 (49.7) | 277 (88.8) | 125 (40.1) | 1017.1 ± 1212.8 | 5943.9 ± 8437.6 | NR | |

| MITRA-FR16 | M-TEER | 152 | 70.1 ± 10.1 | 49/142 (34.5) | 50 (32.9) | 75 (49.3) | 57 (37.5) | 95 (62.5) | 307 (212-387) | 134 (88.2) | 111 (73.0) | 111 (73.0) | 14/140 (10) | NR | 86 (56.6) | 151 (99.3) | 93 (61.2) | NR | NR | 7.33 ± 6.29 |

| Optimal medical therapy | 152 | 70.6 ± 9.9 | 48/147 (32.7) | 39 (25.7) | 52 (34.2) | 66 (43.7) | 85 (56.3) | 335 (210-410) | 138 (90.8) | 113 (74.3) | 113 (74.3) | 17/140 (12.1) | NR | 80 (53.0) | 149 (98.0) | 93 (61.2) | NR | NR | 6.57 ± 5.24 | |

|

ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; AF, atrial fibrillation; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; ARNI, angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitors; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; MI, myocardial infarction; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; NR, not reported; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors. |

||||||||||||||||||||

Table 2. Summary of included studies

| Authors and year | Study design | Device | Population size | Compared interventions | Mean follow-up | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anker et al. RESHAPE-HF2 202414 | RCT | MitraClip | 505 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

| Stone et al. COAP 201815 | RCT | MitraClip | 614 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

| Obadia et al. MITRA - FR 201816 | RCT | MitraClip | 304 | M-TEER Optimal medical therapy | 24 months |

|

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair; OR, odds ratio. |

||||||

Table 3. Echocardiographic baseline characteristics

| Baseline characteristics | RESHAPE-HF214 | COAPT15 | MITRA-FR16 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Device group | Control group | Device group | Control group | Device group | Control group | |

| Severity MR Grade 3+, n,% (n) | 141 (56.4) (250) | 141(55.3) (255) | 148 (49.0) (302) | 172 (55.3) (312) | – | – |

| Severity MR Grade 4+, n,% (n) | 109 (43.6) (250) | 114 (44.7) (255) | 154 (51.0) (302) | 139 (44.7) (312) | – | – |

| LVEF, % (n) | 32 (26-37) (250) | 31 (25-37) (255) | 31.3 ± 9.1 (302) | 31.3 ± 9.6 (312) | 33.3 ± 6.5 | 32.9 ± 6.7 |

| LVEDV, mL (n) | 137 (100-173) (250) | 140 (104-176) (255) | 135.5 ± 56.1 (302) | 134.3 ± 60.3 (312) | – | – |

| LVEDV, mL (n) | 200 (153-249) (250) | 206 (158-250) (255) | 194.4 ± 69.2 (302) | 191.0 ± 72.9 (312) | 136.2 ± 37.4 | 134.5 ± 33.1 |

| LVESD, cm (n) | 5.8 (5.3-6.5) (250) | 5.9 (5.3-6.4) (255) | 5.3 ± 0.9 (302) | 5.3 ± 0.9 (312) | – | – |

| LVEDD, cm (n) | 6.9 (6.3-7.6) (250) | 6.8 (6.4-7.5) (255) | 6.2 ± 0.7 | 6.2 ± 0.8 | – | – |

| EROA, cm2 (n) | 0.23 (0.20-0.30) (250) | 0.23 (0.19-0.29) (255) | 0.41 ± 0.15 | 0.40 ± 0.15 | 0.31 ± 10* | 0.31 ± 11* |

| Regurgitant volume, mL (n) | 35.4 (28.9-43.9) (250) | 35.6 (28.2-42.5) (255) | – | – | 45 ± 13 | 45 ± 14 |

|

EROA, effective regurgitant orifice area; LV, left ventricular; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEDV, left ventricular end-diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; MR, mitral regurgitation. RESHAPE-HF2 data express median and interquartile range [IQR] in the COAPT trial. MITRA-FR data express median ± standard deviation. * This data was originally expressed in mm2 and has been converted to standardized meditation. |

||||||

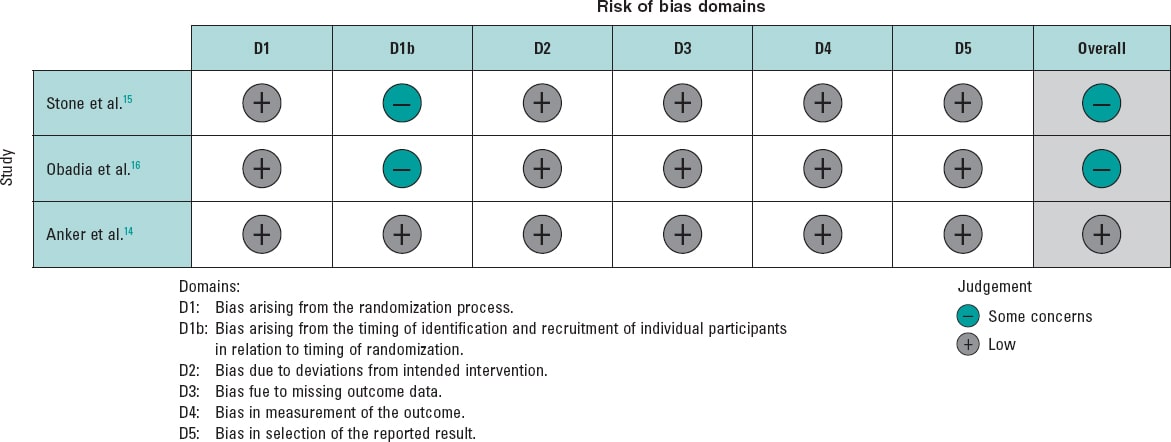

Risk of bias assessment

To evaluate the quality of the included randomized controlled trials, we used the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) tool from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions 6.3.7 This methodology allowed us to systematically assess the methodological quality of each study, thereby strengthening the validity of our findings.

Of the 3 studies, 1 had a low risk of bias,14 while the other 2 raised some concerns.15,16 The studies with some concerns were limited by factors in their methodologies, as they were open-label studies (figure 2).

Figure 2. Risk of bias for each included randomized clinical trial. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al.16.

Outcomes

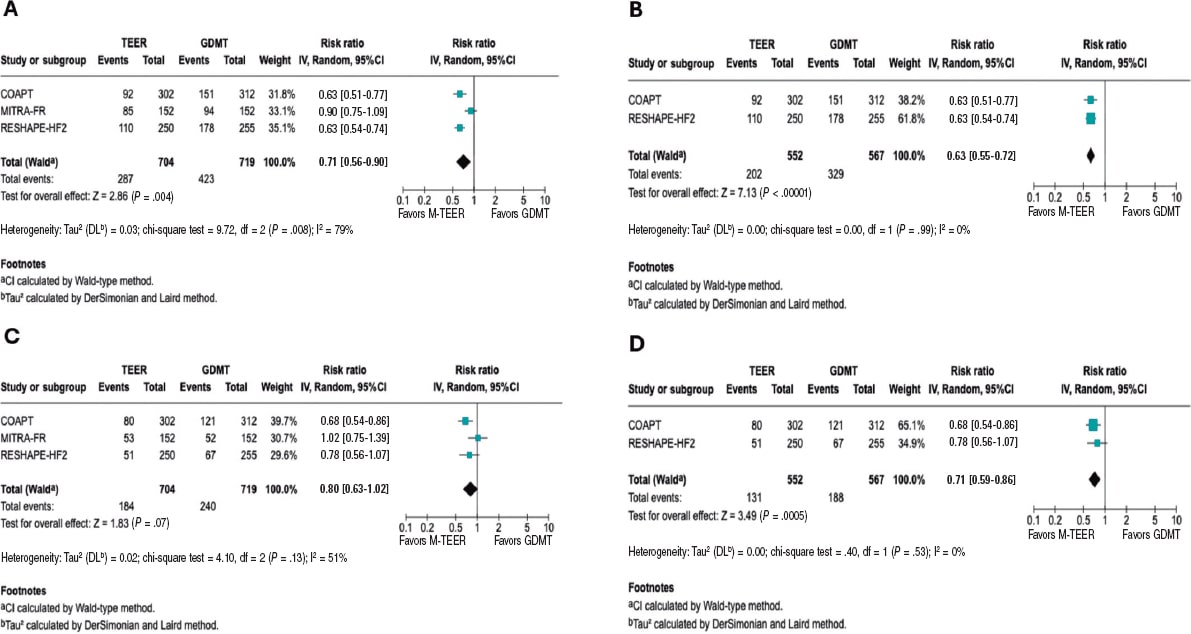

HF-related hospitalization

The analysis of this outcome showed a significant reduction, with a RR of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.56-0.90; P = .004). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed, with an I² value of 79%. Considering the differences in the MITRA-FR study population, we conducted an exploratory analysis excluding this trial. Results still demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of hospitalization, with a RR of 0.63 (95%CI, 0.55-0.72, P < .00001), along with a marked improvement in heterogeneity (I² = 0%). Of note, this finding is exploratory and should be interpreted with caution.

The analysis, including all studies, is shown in figure 3A, and the exploratory analyses are shown in figure 3B. Furthermore, we analyzed HR for this endpoint and, given the limited number of studies, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman (HKSJ) method; all these analyses are provided in the supplementary data (figures S1-S4).

Figure 3. Forest plot of risk ratios (RR). Lines denote the 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for each trial. A: forest plot of RR for HF related hospitalization. B: forest plot of exploratory RR for HF-related hospitalization. C: forest plot of RR for all-cause mortality. D: forest plot of exploratory RR for all-cause mortality. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; GDMT, guideline directed medical therapy; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al.16.

All-cause mortality

The RR for all-cause mortality was 0.80 (95%CI, 0.63–1.02; P = .07). However, substantial heterogeneity was observed across the studies (I² = 56%). In the exploratory analysis, a significant reduction in mortality was found, with an RR of 0.71 (95%CI, 0.59–0.86; P = .0005) and no heterogeneity across the studies (I² = 0%). The analyses, including all studies, are shown in figure 3C, and the exploratory analysis in figure 3D.

Both the HR analysis and the sensitivity analysis are provided in the supplementary data (figures S5-S8).

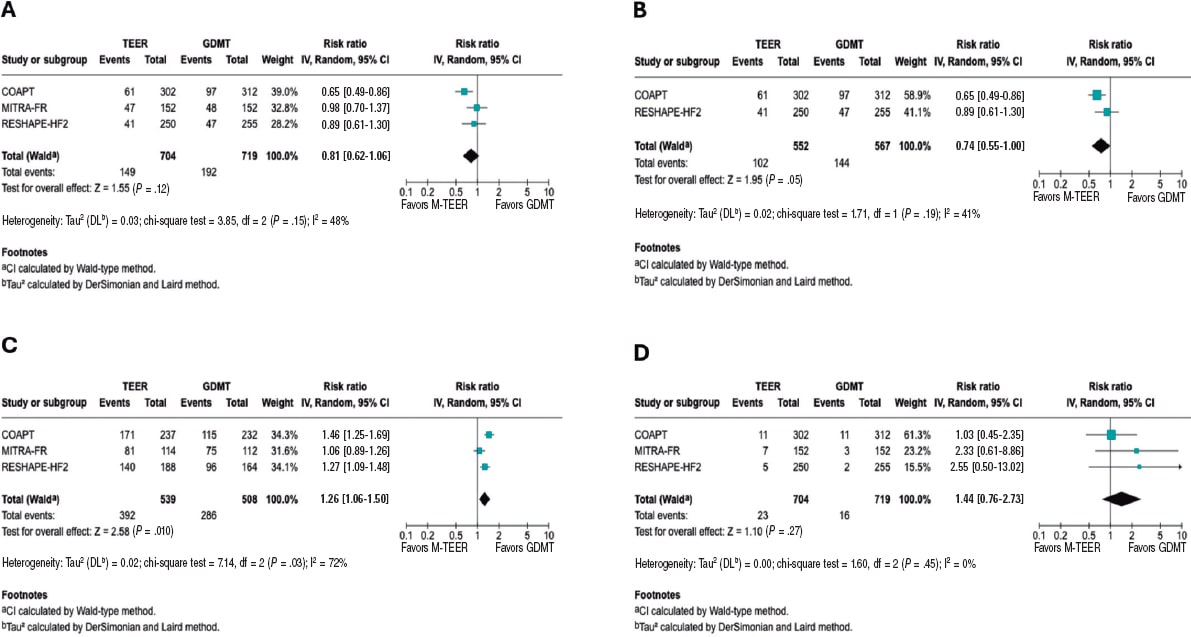

Cardiac death

The RR for death from cardiovascular causes was 0.81 (95%CI, 0.62–1.06, P = .12), with low to moderate heterogeneity (I² = 48%). In the exploratory analysis, a significant reduction in cardiac death was observed, with an RR of 0.74 (95%CI, 0.55–1.00; P = .05) and low heterogeneity (I² = 41%). The analyses, including all studies, are shown in figure 4A, while the exploratory analysis, in figure 4B. The sensitivity analysis and HR results are provided in the supplementary data (figures S9-S12).

Figure 4. Forest plot of risk ratio (RR). A: forest plot of RR for cardiac death. B: forest plot of exploratory RR for cardiac death. C: forest plot of RR of NYHA FC I/II at 1 year. D: forest plot of RR for stroke. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; GDMT, guideline directed medical therapy; M-TEER, mitral transcatheter edge-to-edge repair. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Stone et al.,14 Obadia et al.,15 and Anker et al16. Lines denote the 95%CI for each trial.

NYHA FC

In this analysis of the NYHA FC, we observed that patients undergoing M-TEER are more likely to be found in NYHA FC I/II at 12 months, with a RR 1.26 (95%CI, 1.06–1.50; P = .010), respectively. Of note, the high heterogeneity (I² = 72%). Furthermore, it is also essential to note that the NYHA FC is a subjective classification, which is why the findings of this outcome should be interpreted with caution. These results are shown in figure 4C.

Stroke

There were no statistical differences between M-TEER and optimal medical therapy regarding stroke, with a RR of 1.44 (95%CI, 0.76 - 2.73, P = .27) without any heterogeneity being reported across the studies (I² = 0%). These results are shown in figure 4D.

Myocardial Infarction

Regarding the risk of myocardial infarction, our analysis demonstrated no statistical difference between the M-TEER and optimal medical therapy groups (RR, 0.83; 95%CI, 0.43-1.61; P = .58). No heterogeneity among the studies was observed (I² = 0%); this finding is shown in supplementary data (figure S13).

Exploratory analysis by severity

We conducted an exploratory analysis stratified by the baseline grade of mitral regurgitation. Data on the composite endpoint of all-cause death or HF-related hospitalization were available according to MR grade. For patients with MR 3+, the RR was 0.75 (95%CI, 0.56-1.00; P = .05; I² = 12%). For those with severe MR 4+, data were available only from the RESHAPE-HF2 and COAPT trials, yielding a RR of 0.55 (95%CI, 0.42-0.73; P = .0001; I² = 0%). This finding is shown in the supplementary data (figure S14 to figure S15).

DISCUSSION

Our meta-analysis provides an evaluation of 3 major RCTs, COAPT15, MITRA-FR16, and RESHAPE-HF214, evaluating M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone in patients with secondary MR. In patients with persistent symptoms despite adequate GDMT and who do not meet the criteria for definitive surgical replacement, mitral M-TEER has emerged as a promising alternative. In this updated meta-analysis, no statistically significant effect on all-cause mortality was found; however, the marked between-trial heterogeneity suggests that M-TEER provides meaningful clinical benefit when used in appropriately selected patients.

Our study showed that heterogeneity of results was mainly driven by MITRA-FR. COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 have multiple similar differences compared with MITRA-FR, as evidenced in trial cohort baseline characteristics, methods, and outcome directions. This is better portrayed by an exploratory analysis comparing COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 results, showing a 37% reduction in the risk of HF-related hospitalization risk and a 32% reduction in cardiac death (figure 3). The overall neutral mortality rate resulting from our study may be driven by heterogeneity across trials rather than a lack of intrinsic therapeutic benefit.

Among the main differences across trials, the MITRA-FR trial had broader inclusion of patients with tricuspid regurgitation, advanced LV remodeling, greater dilation, and smaller EROA vs the other 2 trials. Another key source of heterogeneity was baseline MR severity. COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 primarily enrolled patients with grade 3+ and 4+ MR, whereas MITRA-FR is only focused on grade 4+, which may contribute to the observed outcome differences. In our exploratory analysis by MR grade, data showed consistent trends favoring M-TEER; however, these findings should be interpreted with caution due to limited subgroup data.

As proposed by Paul et al.,19 one strategy to evaluate secondary MR is to consider the proportion between EROA and LVEDV. In the MITRA-FR trial, many patients had smaller EROA with markedly dilated ventricles, a phenotype in which GDMT may have more impact than valve proceduren. In the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials, a greater proportion of patients had large EROA relative to the LVEDV,20 making MR a primary driver of symptoms and outcomes, and, therefore, with potential for greater benefit from M-TEER.

In the trial-level subgroup analyses, the COAPT15 and RESHAPE-HF214 trials reported no significant interaction between treatment assignment and ischemic vs non-ischemic etiology, which indicates consistency of benefit across etiologies. Similarly, the MITRA-FR16 did not identify significant heterogeneity regarding etiology across prespecified subgroups. This suggests that ischemic vs non-ischemic alone should not be used to decide the treatment option in secondary MR. Instead, clinical decisions should prioritize other factors, such as the MR severity, the degree of LV dysfunction, symptom burden, and response to optimal medical therapy.21

Furthermore, differences between trials in procedural success are noteworthy, defined as achieving MR ≤ 2+. This was substantially lower in the MITRA-FR (75.6% MR ≤ 2+ at discharge) vs the COAPT (94.8% MR ≤ 2+ at 12 months) and the RESHAPE-HF2 (90.4% MR ≤ 2+ at 12 months). Multiple reasons could have influenced such differences; for instance, operator experience requirement in MITRA-FR (≥ 5 prior MitraClip cases) vs the high-volume and more experienced centers from the other trials. Similarly, post-approval data from the U.S. SSTS/ACC TVT Registry22 demonstrated > 90% MR reduction to ≤ 2+ and survival rates consistent with trial outcomes, underscoring the reproducibility of clinical benefit in experienced centers. Furthermore, device technology is a main contributor to these differences, from first-generation clips in MITRA-FR, to second-generation in COAPT, to the fourth-generation in RESHAPE-HF2 with independent leaflet grasping and wider arm options, potentially explaining discrepant clinical results regarding MR durability and outcomes. Lastly, GDMT implementation differed across trials. MITRA-FR was conducted before the widespread use of ARNI and SGLT2 inhibitors; COAPT was conducted before the adoption of SGLT2 inhibitors; and RESHAPE-HF2 reflects the contemporary use of quadruple therapy.

Despite the differences in patient phenotypes across the trials, in many developing countries, access to transcatheter valve procedures remains limited, primarily due to their high cost and the need for specialized infrastructure.23,24 The pronounced disparities in access to cutting-edge technologies, coupled with the centralization of these procedures in a few urban centers or high-specialty hospitals, a phenomenon observed even in high-income countries such as the United States, leave a substantial portion of the population without viable treatment options.25 Consequently, the most impactful and broadly deployable intervention in these regions remains rigorous GDMT optimization and provider education. Nevertheless, patient phenotyping should still be performed to identify those who may potentially have an outsized benefit from future M-TEER referrals.

By integrating trial-level population characteristics with clinical outcomes, our work bridges the gap between isolated trial findings and real-world patient selection, thus offering a potential framework for future prospective studies and for refining guideline criteria. While the results from our study must be interpreted with caution, they provide hypothesis-generating evidence supporting the concept that patient selection, particularly considering the balance between EROA and LVEDV and GDMT optimization, may be critical to optimizing the benefit of M-TEER in secondary MR. This approach moves beyond the broad application of current guideline recommendations and points toward a more individualized strategy in which anatomical and functional parameters guide intervention.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this study lies in the heterogeneity of the populations enrolled in the randomized controlled trials, as evidenced by the I2 observed in the analyses, which may influence the overall results. Second, differences in MR severity across trials represent a key limitation. While the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials mainly included patients with MR grade 3+ or 4, MITRA-FR enrolled a more severe grade, which may partly explain divergent results. Lastly, an individual patient-level meta-analysis could not be conducted due to lack of data; this level of analysis would further increase statistical power, especially in subgroup analyses, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In this meta-analysis, M-TEER plus GDMT shows a lower risk of HF-related hospitalization vs GDMT alone. We did not find any differences in the risk of all-cause mortality, cardiac death, stroke, or myocardial infarction.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This meta-analysis was performed using data from previously published studies. As it is based entirely on secondary data, no new data were collected from human or animal participants; on the other hand, the use of SAGER guidelines was not applicable in this study. All included studies were approved from the relevant center ethics committees. The authors confirm that all data utilized were publicly accessible, and no confidential information was used without proper authorization.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4o to review the document’s syntax and grammar. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

D. Paulino-González: conceptualization; formal analysis, writing, review, and editing. A.L. García-Loera: methodology, investigation, writing, review, and editing. D.A. Navarro-Martínez: methodology, formal analysis. M.A. Pardiño-Vega: writing, review, and editing, supervision. K.P. Zúñiga-Montaño: investigation, writing, review, and editing.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Mitral regurgitation is a prevalent condition that negatively affects the patients’ quality of life. M-TEER-has emerged as an alternative therapeutic option for patients who are ineligible for surgery. However, its benefit remains unclear vs GDMT, as clinical trials evaluating this procedure have reported disparate results, with benefit in primary outcomes observed in the COAPT trial and in the recently published RHESAPE-HF2 trial, but not in the MITRA-FR trial; discrepancy in the results requires further study.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This meta-analysis provides a comprehensive evaluation of the evidence comparing M-TEER plus GDMT vs GDMT alone in secondary mitral regurgitation. Our findings confirm that M-TEER is associated with a significant reduction in HF-related hospitalizations. Of note, by examining trial populations in detail, we highlight how patient selection influences outcomes: in studies enrolling patients with less ventricular dilation and lower biomarker levels of congestion (such as the COAPT and RESHAPE-HF2 trials), M-TEER was associated with additional benefits in cardiac death and all-cause mortality. These results underscore the potential role of anatomical and functional parameters, such as the balance between EROA and LVEDV, in identifying patients most likely to benefit from this procedure.

REFERENCES

1. Chehab O, Roberts-Thomson R, Ng Yin Ling C, et al. Secondary mitral regurgitation:pathophysiology, proportionality and prognosis. Heart. 2020;106:716-723.

2. Sengodan P, Younes A, Shah N, Maraey A, Chitwood WR Jr, Movahed A. Contemporary review of the evolution of various treatment modalities for mitral regurgitation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2024;22:639-651.

3. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159-e1195.

4. Itabashi Y, Kobayashi S, Mizutani Y, Torikai K, Taguchi I. Treatment of secondary mitral regurgitation by transcatheter edge-to-edge repair using MitraClip. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2022;49:389-403.

5. Barnes C, Sharma H, Gamble J, Dawkins S. Management of secondary mitral regurgitation:from drugs to devices. Heart. 2024;110:1099-1106.

6. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement:an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

7. Sterne JAC, Savovic´J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2:a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898.

8. Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2022;145:e1033.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2022;146:e185.] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2023;147:e674]. Circulation. 2022;145:e895-e1032.

9. Abraham WT, Psotka MA, Fiuzat M, et al. Standardized Definitions for Evaluation of Heart Failure Therapies:Scientific Expert Panel From the Heart Failure Collaboratory and Academic Research Consortium. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:961-972.

10. Sacco RL, Kasner SE, Broderick JP, et al. An updated definition of stroke for the 21st century:a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association [published correction appears in Stroke. 2019;50:e239]. Stroke.2013;44:2064-2089.

11. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (2018). Glob Heart. 2018;13:305-338.

12. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560.

13. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188.

14. Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, et al. Transcatheter Valve Repair in Heart Failure with Moderate to Severe Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med.2024;391:1799-1809.

15. Stone GW, Lindenfeld J, Abraham WT, et al. Transcatheter Mitral-Valve Repair in Patients with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2307-2318.

16. Obadia JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, Leurent G, et al. Percutaneous Repair or Medical Treatment for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation. N Engl J Med.2018;379:2297-2306.

17. Iung B, Armoiry X, Vahanian A, et al. Percutaneous repair or medical treatment for secondary mitral regurgitation:outcomes at 2 years. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21:1619-1627.

18. Ponikowski P, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS, et al. Hospitalization of Symptomatic Patients With Heart Failure and Moderate to Severe Functional Mitral Regurgitation Treated With MitraClip:Insights From RESHAPE-HF2. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;84:2347-2363.

19. Grayburn PA, Sannino A, Packer M. Proportionate and Disproportionate Functional Mitral Regurgitation:A New Conceptual Framework That Reconciles the Results of the MITRA-FR and COAPT Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12:353-362.

20. Anker SD, Friede T, von Bardeleben RS. Percutaneous repair of moderate-to-severe or severe functional mitral regurgitation in patients with symptomatic heart failure:Baseline characteristics of patients in the RESHAPE-HF2 trial and comparison to COAPT and MITRA-FR trials. Eur J Heart Fail. 2024;26:1608-1615.

21. Nappi F, Singh SSA, Bellomo F.Exploring the Operative Strategy for Secondary Mitral Regurgitation:A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int.2021;2021:3466813.

22. American College of Cardiology. STS/ACC TVT Registry Analysis Finds TMVr Safe and Effective in Real-World Setting. ACC. 2023 Mar 5. Available at: https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2023/03/01/22/45/Sun-1215pm-sts-acc-tvt-acc-2023. Accessed 1 Jul 2025.

23. Bernardi FLM, Ribeiro HB, Nombela-Franco L, et al. Recent Developments and Current Status of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Practice in Latin America - the WRITTEN LATAM Study. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2022;118:1085-1096.

24. Bana A. TAVR-present, future, and challenges in developing countries. Indian J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019;35:473-484.

25. Steitieh D, Zaidi A, Xu S, et al. Racial Disparities in Access to High-Volume Mitral Valve Transcatheter Edge-to-Edge Repair Centers. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1:100398.