ABSTRACT

Aortic coarctation is a congenital disease that consists of the narrowing of the thoracic aorta, leading to distal blood flow obstruction. Significant aortic coarctation is associated with hypertension and distal hypoperfusion, with a poor prognosis without intervention. Initially, treatment was surgical; however, less invasive techniques such as percutaneous balloon angioplasty later emerged and proved effective in selected patients.

The introduction of stent implantation significantly improved the outcomes, making percutaneous repair the preferred option, especially in adolescents and adults.

However, immediate and long-term complications persist, which has driven research efforts aimed at improving the safety and efficacy profile. Modern strategies now focus on advanced stent designs, offering better delivery profiles and high redilatation potential. Gaps in knowledge remain, and data from studies with longer follow-up will be essential to further elucidate disease progression in these patients. This review aims to offer a comprehensive overview of these percutaneous procedures, discussing recent advancements, clinical outcomes, and future perspectives. atención de la estenosis aórtica grave, al tiempo que se mantiene una alta calidad del procedimiento.

Keywords: Aortic coarctation. Percutaneous repair. Complications. Advanced stent designs.

RESUMEN

La coartación de aorta es una enfermedad congénita caracterizada por el estrechamiento de la aorta torácica, que provoca una obstrucción del flujo sanguíneo distal. Una coartación de aorta significativa se asocia con hipertensión arterial e hipoperfusión distal, así como con un mal pronóstico sin intervención. Inicialmente el tratamiento era quirúrgico, pero fueron surgiendo técnicas menos invasivas, como la angioplastia percutánea con balón, que mostró eficacia en ciertos pacientes. La incorporación del implante de stents mejoró de manera significativa los resultados, convirtiendo la reparación percutánea en la opción preferida, en especial en adolescentes y adultos. Sin embargo, siguen produciéndose complicaciones inmediatas y a largo plazo. Esto ha impulsado esfuerzos destinados a mejorar su seguridad y eficacia. Las estrategias modernas se enfocan en stents de diseño avanzado, con mejor perfil de entrega y un alto potencial de redilatación. Persisten vacíos por llenar, y nuevos datos provenientes de estudios con seguimientos más prolongados permitirán comprender mejor la evolución de estos pacientes. Esta revisión tiene como objetivo ofrecer una visión integral de estas intervenciones percutáneas, abordando los avances, los resultados y las perspectivas futuras.

Palabras clave: Coartación de aorta. Reparación percutánea. Complicaciones. Stents de diseño avanzado.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic coarctation (AC) is a congenital heart disease (CHD) that is defined as a narrowing of the thoracic aorta. This defect is usually located distal to the left subclavian artery and near, or at, the insertion of the ductus arteriosus remnant. Severity may vary, and AC can present as a discrete stenosis or as a long and/or tortuous stenotic segment.1,2 AC is one of the most common CHD, accounting for 5% to 8% of this group of defects,3 with a rate of 3 to 4 cases per 10 000 live births. Male sex is more prevalent, with a 2:1 predominance.4 Other congenital cardiovascular defects are usually found accompanying this disease, with a rate of 70% to 87%.1,5,6 The most common is the bicuspid aortic valve (BAV), which has been reported in up to 60% of cases.1,2

The clinical presentation depends on the severity of the obstruction and the presence of other accompanying CHD. Severe cases present in the neonatal age, often with cardiogenic shock. In contrast, less severe obstructions can be detected in childhood or even adulthood with upper body hypertension, ventricular hypertrophy, thoracic aorta dilatation, and progressive collateralization.7,8 Signs and symptoms are listed in table 1.9

Table 1. Signs and symptoms of aortic coarctation in adults with unrepaired AC9

| Signs | Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Upper extremity hypertension | Exertional intolerance/dyspnea |

| Weak or absent femoral pulses | Headache |

| Brachio-femoral delay | Epistaxis |

| Blood pressure gradient between the upper and lower extremities | Dizziness |

| Systolic or continuous murmur between the scapulae | Lower extremity claudication |

| Aortic regurgitation murmur (in cases of dilated aortic root with or without bicuspid valve) | Abdominal angina |

| Apical impulse displaced (in cases of dilated left ventricle) | Tinnitus |

| Cold feet |

The natural history of unrepaired aortic coarctation is associated with a markedly poor prognosis. Campbell et al. reported the leading causes of death in unrepaired AC: congestive heart failure (25%), aortic rupture (21%), bacterial endocarditis (18%), and intracranial hemorrhage (11%).10 Therefore, AC repair in patients with significant stenosis is mandatory to improve prognosis and quality of life. Currently, clinical practice guidelines suggest intervention when AC is accompanied by hypertension and a peak-to-peak invasive gradient > 20 mmHg.11 Surgery was the first repair technique, with percutaneous treatment subsequently established as a viable therapeutic option for eligible patients. This review aims to summarize available evidence on percutaneous interventions, discussing advancements, outcomes, and future perspectives.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The first AC surgery was performed by Crafoord in 1944, and consisted of resection and end-to-end anastomosis.12 Since then, other surgical techniques have evolved to prevent recoarctation and aneurysm formation, including patch aortoplasty, subclavian flap aortoplasty, and coarctectomy with graft interposition.2

Although surgery was the gold standard for many years, the introduction of percutaneous therapies opened a new spectrum of possibilities. The first percutaneous treatment for AC was published in 1982 by Singer et al. They successfully performed a balloon angioplasty (BA) to treat an AC in a newborn.13 Despite the effectiveness of this technique, it was associated with a high rate of recoarctation and aneurysm formation.14,15

The first documented case of stent implantation in a patient with AC was published in 199116, and later, in 1995, Suárez de Lezo et al. reported the first series of patients treated with the same approach, showing safety and efficacy.17 The main advantage of stent implantation is the provision of structural support, which reduces complications.18 In 1999, Gunn et al. and subsequently other authors reported the use of covered stents with good results.19-21

Currently, stent implantation is recommended by the European clinical practice guidelines as the first option in adult patients with appropriate anatomy.11 However, surgical repair remains essential in some instances, requiring careful determination of the optimal approach.

BALLOON ANGIOPLASTY

BA was initially used in neonates and infants with AC and heart failure as a bailout strategy or as definitive therapy in cases of high surgical risk.13 However, this technique was subsequently tested in older children and adults. The main advantage of BA is its simplicity, with good results in discrete coarctation. However, balloon dilatation inside the aorta can rupture the intima and damage the media layers, with subsequent potential complications.22

Disadvantages include lower efficacy in complex anatomies, such as isthmic hypoplasia and diffuse stenosis.23,24 The most common complications are aortic dissection and elastic recoil in the short term, and recoarctation and aneurysm formation in the long term.23,25,26 A retrospective registry of children treated with BA reported aortic rupture/dissection in 2% of cases, recoarctation in 26% and aneurysm formation in 34%.27 Similarly, a randomized clinical trial comparing balloon angioplasty vs surgical treatment in children revealed that aneurysm formation occurred in 20% and restenosis in 25% of the patients treated with angioplasty.28 On the other hand, in older patients with discrete coarctation, Walhout et al. and Fawzy et al. have found a low rate of recoarctation (≈3%).29,30 Similarly, aneurysm formation in adults appears to be lower vs children (1.8-6%).31,32

BA shows a good efficacy profile in 67%-90% of cases of recurrent coarctation (postoperative or patients with a previous BA), especially in children. Therefore, currently, recurrent AC is one of the main indications for BA.25,33-35 Furthermore, it is used in native coarctation in children to delay stent implantation until adulthood, when adult-sized stents can be implanted as definitive therapy. Despite these primary indications, in selected cases with discrete, non-critical obstruction, BA may be effective and stent implantation can be avoided, as we previously mentioned.36

TRANSCATHETER STENT PLACEMENT

The introduction of stent implantation in AC aimed to improve short- and long-term outcomes after balloon angioplasty, reducing complications due to aortic elasticity, recoil, and wall rupture.35 The radial strength of the stent opposes the aortic recoil and helps to improve vessel integrity after the trauma inherent to balloon dilatation.35

Zabal et al. found that the residual gradient was significantly lower in patients treated with stent implantation vs those undergoing BA. This difference was more evident in patients with non-discrete coarctation (tubular coarctation or isthmic hypoplasia), in whom a residual gradient > 20 mmHg was observed in 57% of cases after BA vs 0% in the stenting group.36 Furthermore, stenting reduces the rate of recoarctation and aneurysm formation.37-39

Moreover, stent implantation has demonstrated to be safe in the treatment of recoarctation, especially in patients who have undergone surgical repair. Despite several complications having been described, long-term follow-up has shown promising efficacy.40,41

Currently, stent implantation is preferred over BA in adults and adolescents. Furthermore, the European clinical practice guidelines recommend stenting over surgical repair when the anatomy is favorable.42

Despite the advantages, stenting in children younger than 8-10 years is still limited by the risk of vascular complications at the access site (greater sheaths needed), and the additional limitation of being unable to implant an adult-sized stent in a still-growing aorta, as well as the challenge of placing stents that can be adequately postdilated to accommodate future aortic growth.25,43

Covered vs uncovered stents

First, it is essential to note that balloon-expandable stents are preferred over the self-expandable ones due to the greater radial strength of the former, which enhances AC dilatation and prevents aortic recoil. Among balloon-expandable stents, covered stents are preferred over the bare-metal (uncovered) ones in most clinical scenarios. Covered stents can create a sealing effect at the implantation site, providing an additional safety feature.44

Currently, covered stents are considered first-line stents for percutaneous management of native AC, stent fracture, recoarctation, and aneurysm formation.11 In the native AC scenario, covered stents are preferred, especially in complex anatomies, older patients, patients with connective tissue disease, or Turner syndrome (TS) to prevent aortic wall rupture or aneurysm formation.25,38 The “sealing effect” is advantageous in previously treated patients who develop aneurysm formation or rupture of the vessel wall.45

Uncovered stents are preferred in children due to the possibility of redilating the stent to accommodate aortic growth. Covered stents can only be dilated up to a specific diameter without damaging their covering material. This is why covered stents are indicated for adult patients.46

HYBRID APPROACHES

A hybrid approach combining surgical procedures with percutaneous treatment is currently an option in patients with CHD. In the context of AC, a hybrid approach is typically necessary when the patient presents with another additional congenital heart defect that requires surgical repair. A common scenario is the coexistence of a dilated ascending aorta and a BAV with significant regurgitation or stenosis.47 The management of such cases is always challenging due to the lack of standard guidelines and recommendations. The timing of the corrections and the type of procedures to be applied are still under discussion.

Several authors have reported cases of patients with BAV disease accompanied by ascending aorta dilatation and aortic regurgitation, which were initially treated with a percutaneous technique for the AC and later underwent a Bentall procedure.47,48 Probably, AC repair before valvular replacement can decrease the risk of hypoperfusion of organs distal to the coarctation. However, the evidence remains inconclusive; first-stage surgical repair of valvular disease has nonetheless been reported as successful.49

As a new approach, Russell et al. reported their experience with a patient with BAV, ascending aorta dilatation, and AC. They performed a single-stage hybrid approach that included endovascular repair of the aortic root (AC), followed in the same session by surgical replacement of the aortic valve and ascending aorta.50

IMAGING, PATIENT SELECTION, AND PROCEDURAL CONSIDERATIONS

Imaging

Multimodal imaging evaluation is mandatory in patients with suspected AC to adequately characterize the anatomy, rule out accompanying malformations, and help to decide the best therapeutic option.

Transthoracic echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography is usually the first imaging modality performed in patients with suspected AC. Transthoracic echocardiography can reveal ascending aorta dilatation and, in some cases, allows localization of coarctation in the suprasternal view with 2D imaging and color Doppler. Additionally, spectral Doppler in the suprasternal view can display the typical “saw tooth” pattern with continuous wave Doppler, enabling the measurement of the gradient in favorable cases.51

Computed tomography angiography

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is considered the imaging modality of choice for evaluating the thoracic aorta in patients with contraindications to cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), such as pacemakers and defibrillators. Furthermore, it is the gold standard for aortic dissection, a known complication of AC, and the preferred imaging modality for evaluating luminal patency and ruling out restenosis or stent fracture in patients who have undergone a previous AC repair.52

Compared with CMR, the CTA provides a higher spatial resolution of the aorta, requires shorter acquisition times, and is better tolerated by claustrophobic patients; however, its disadvantages include the use of ionizing radiation and the need for IV dye, which can lead to kidney damage.53

Cardiac magnetic resonance

CMR is currently considered the gold standard imaging modality for evaluating adult patients with suspected AC and other CHD. This modality can accurately identify the location and significance of the coarctation using phase-contrast flow analysis. Furthermore, CMR facilitates measurement of the coarctation segment length and aortic dimensions to select an appropriate stent size, identifies collateral flow in the intercostal arteries, assesses cardiac function, and the presence of other concomitant CHD. All of these advantages are achieved without the use of ionizing radiation.54,55 Moreover, CMR is used for postoperative surveillance after stent implantation and surgery to detect potential complications.2

Patient selection and indications

Native AC or recoarctation repair (either surgical or transcatheter) is mandatory in patients with hypertension and a confirmed peak-to-peak gradient across the coarctation > 20 mmHg (class I indication), with a preference for stenting when technically feasible in both most recent European and American clinical practice guidelines.11,56 Furthermore, according to European clinical practice guidelines, AC percutaneous repair should be considered in patients with hypertension and 50% narrowing without peak-to-peak gradient < 20 mmHg, and normotensive patients without significant gradients (class IIa indication).11

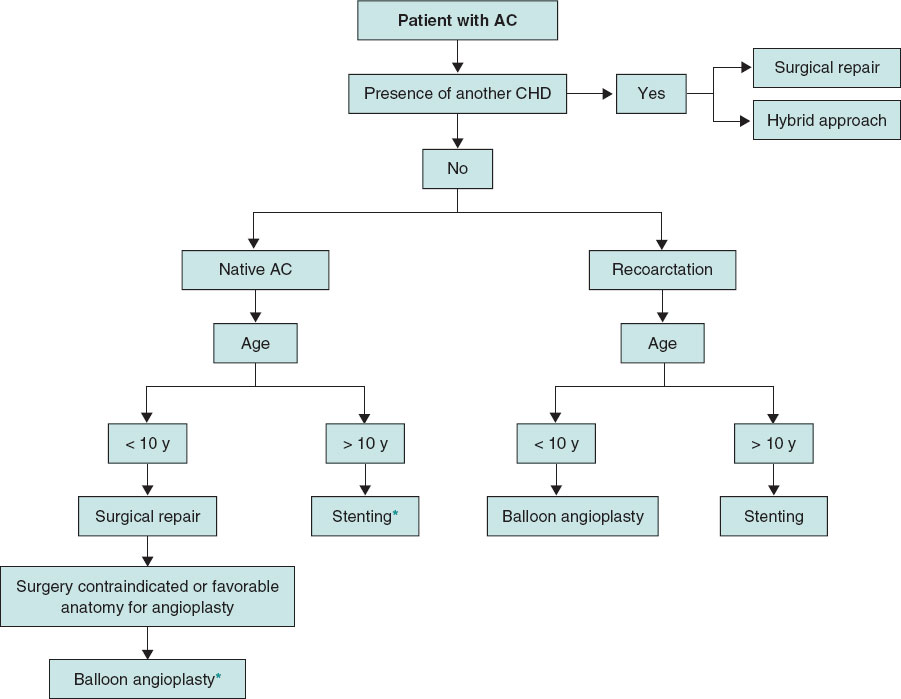

Repair strategy selection in patients with AC should be based on meticulous analysis, considering key factors such as patient age and weight, anatomic characteristics of the coarctation, and a history of prior surgical procedures. Typically, percutaneous repair is considered a lower-risk alternative to surgery in correctly selected patients. A schematic representation of the decision-making process is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed algorithm of first-line therapies according to the age of patients with aortic coarctation. The suggested approach in each case and age group is general, and the decision on the selected strategy will depend on the anatomic characteristics and the centers’ experience. AC, aortic coarctation; CHD, congenital heart disease.

*Some authors suggest a “threshold” of 25 kg, below which the use of a stent would be inadvisable.

In infants and children aged 8-10 years with native AC, surgical repair is preferable to percutaneous techniques. If an endovascular intervention is selected, BA will be the preferred approach.25 Furthermore, some authors suggest a “threshold” of 25 kg, below which stenting is not recommended due to greater sheaths needed, and represents a high risk for vascular complications.57

In adolescents and adults, if the anatomy is adequate and there is no accompanying CHD requiring surgical repair, percutaneous stenting is currently considered the first-line therapy.25 These considerations will depend on the patient’s individual anatomic characteristics. Additionally, each center’s experience with these cases will influence clinical decision-making.

Procedural considerations

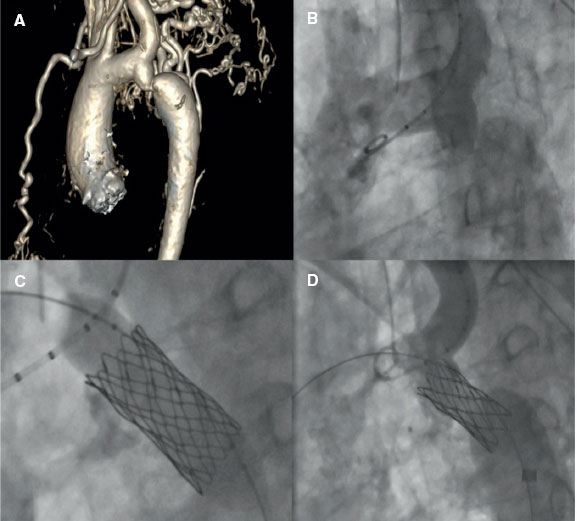

Adequate planning will be crucial in ensuring better outcomes and minimizing the risk of complications associated with coarctation stenting. Several steps may coincide with the BA. The main steps and technical considerations will be addressed below. Figure 2 illustrates a case of an AC successfully treated with stent implantation.

Figure 2. A successful treatment of aortic coarctation in an adult. A: computerized tomography showing aortic coarctation. B: angiography confirming aortic coarctation. C: balloon angioplasty and stent implantation. D: final fluoroscopic result after stent implantation.

First, before the procedure, managing hypertension is crucial as a hypertensive crisis is commonly observed after stent implantation. Beta-blockers can help to prevent such crises. Furthermore, strict postoperative monitoring is recommended to detect and manage hypertension effectively, ensuring better patient outcomes. Some authors recommend performing any percutaneous treatment under general anesthesia. AC dilatation is often painful, and the use of this approach could ensure a more comfortable procedure.35 However, in general, light or moderate sedation is usually sufficient for adult patients.

- – Access: typically, the common femoral artery (right or left) is used. Preclosure with a Perclose ProGlide (Abbott Vascular, United States) should be considered. The sheath size should be selected based on the balloon or stent diameter; delivery sheaths 2-3-Fr sizes larger than the minimum required for the balloon are recommended. Unfractionated heparin is administered to achieve an activated clotting time > 250 seconds. Furthermore, a prophylactic dose of cefazolin should be administered.

- – Coarctation crossing: AC can usually be crossed with a conventional 0.035 in polytetrafluoroethylene guidewire, and sometimes a hydrophilic guidewire. In extremely difficult anatomies, retrograde access from the radial artery with externalization via femoral artery may be necessary. New gradient measurements and angiographies should be obtained to evaluate the defect. The initial guidewire will be exchanged for an extra-stiff guidewire that will be positioned in the ascending aorta or the left subclavian artery (only if the distance from the subclavian ostium to the defect is > 10 mm).

- – Balloon and stent size selection: stent (and balloon) should be sized according to the diameter of the proximal arch without exceeding the diameter of the diaphragmatic aorta.57 Stent length should be adequate to cover the stenotic segment, bearing in mind that over-dilation may result in shortening of up to 30%. Several of the stents currently available for AC treatment are listed in Table 2.

- – Dilatation and stent implantation: Predilatation is not routinely recommended as anchorage and stent implantation are generally more effective with direct stent placement. However, in cases of critical stenosis, predilatation turns out to be unavoidable.

- After dilatation, the ratio of the final stent diameter vs the most stenotic region of the AC should be < 3.5.57

- – Effectiveness: The procedure will be considered successful when the invasively measured residual gradient is < 10 mmHg.58

Table 2. Stents used for AC repair

| Covering | Assembly | Stent model | Manufacturer | Metal | Expansion range (mm) | Shortening | Cell type* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncovered | Pre-assembled | Formula | Cook Medical | Stainless steel | 8-20 | ~ 10-15% | Closed-cell |

| Not pre-assembled | Andrastent XL and XXL | Andramed | Cobalt-chromium alloy | 12-32 | < 5% | Open-cell | |

| CP stent | NuMED | Platinum-iridium alloy | 12-30 | ≈ 15-20% | Closed-cell | ||

| Optimus | AndraTec GmbH | Cobalt-chromium alloy | 10-28 | ~ 5% | Open-cell | ||

| Covered | Pre-assembled | Begraft aortic | Bentley Innomed GmbH | Cobalt-chromium alloy | 12-24 | < 5% | Closed-cell |

| Atrium Advanta V12 | Maquet | Stainless steel | 12-16 | 0-15% | Closed-cell | ||

| NuDEL | NuMED | Platinum-iridium alloy | 12-24 | ~ 10% | Closed-cell | ||

| Not pre-assembled | CP covered | NuMED | Platinum-iridium alloy | 12-24 | ~ 15-20% | Closed-cell | |

| Optimus covered | AndraTec GmbH | Cobalt-chromium alloy | 12-28 | < 5% | Open-cell | ||

|

* Open-cell stents have larger gaps and fewer connecting struts, offering greater flexibility and conformability to curved vessels. Closed-cell stents feature more interconnections, providing higher radial strength and uniform coverage but reduced flexibility and adaptability in tortuous anatomies. |

|||||||

OUTCOMES AND COMPLICATIONS

Immediate and short-term outcomes

Percutaneous treatment of AC has proven safe and effective, with success rates varying by intervention type and patient population. Immediate complications related to transcatheter repair include aortic wall rupture, stent malapposition, and vascular access site complications; their rate varies across groups and reports. Steiner and Prsa found that BA achieved a success rate of 71% in native AC and 69% in recoarctation. On the other hand, stent implantation showed a 100% success rate in both situations.59 A meta-analysis conducted by Nana et al. found that the technical success rate of stenting in adults was 97%, with intraoperative and 30-day mortality rates of 1%.60 Another meta-analysis by Yang et al. reported an overall success rate of 98% for stent implantation in native AC.61

Long-term outcomes

Transcatheter treatment using stents, both bare-metal and covered, has demonstrated excellent long-term outcomes. Schleiger et al. reported a procedural success rate of 88.2% and survival rates of 98.1% at 5 years, 95.6% at 10 years, and 95.6% at 15 years. Reintervention rates were 27.8% at a median follow-up of 7.3 years, with no significant difference between bare and covered stents.62 The COAST and COAST II trials showed a good efficacy profile at the follow-up and less antihypertensive drug use.63

Long-term complications include aneurysm formation, restenosis, stent fracture, and stent migration.64 Of note, the COAST and COAST II trials reported a cumulative rate of stent fractures of 24.4% at late follow-up. Reintervention rates were 21.3%, with predictors including younger age and smaller stent diameters.63

Pan et al. provided one of the longest published follow-up (from 4 to 30 years). The cumulative rate of stent fracture at the long-term follow-up was 34%, while aneurysm formation occurred in 13% of cases.65

Overall, stenting is associated with high procedural success rates, significant long-term survival benefits, and a lower rate of hypertension. However, long-term follow-up is essential due to the risks of stent fractures, reinterventions, and potential late complications such as aneurysm formation.42,56

ADDRESSING LIMITATIONS IN SPECIFIC PATIENT POPULATIONS

Turner syndrome and connective tissue diseases

CHD can be found in approximately one-third of patients with TS, of which 75% correspond to AC or BAV.66,67 Although the usual first-line therapy for AC in children is surgical repair, patients with TS exhibit high rates of aortic dissection (11%) and aneurysm formation (30%) after surgery.68 These results are attributed to inherent aortic wall weakness due to cystic medial necrosis observed in TS.68 Therefore, percutaneous treatment with covered stent implantation is currently the preferred treatment option in patients with adequate anatomy. Covered stents can cover the injured area in the stented wall and help to reduce the risk of aneurysm formation in this particular vascular situation.69

Regarding connective tissue diseases, such as Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, there is insufficient evidence to select the optimal treatment for AC in these cases. However, similar considerations to those outlined previously outlined for TS may be applied, selecting covered stents when percutaneous treatment is anatomically feasible.

Adults and elderly patients

Elderly patients usually present with severe calcification at the coarctation site, which complicates the stent implantation and expansion, which can lead to suboptimal outcomes and increased risk of complications. In this regard, some authors recommend performing a series of dilations of the implanted stent to restore the physiological aortic diameter gradually. The use of covered stents to treat AC should be advised in elderly patients with a calcified aortic wall.70

In selected complex cases, such as adults with longstanding severe coarctation leading to near or complete aortic occlusion, percutaneous treatment may still be feasible. These cases require careful procedural planning, often using staged balloon dilations or covered stents to restore aortic patency safely. Advanced techniques such as guidewire escalation strategies, retrograde or antegrade access, and careful predilatation may be employed to minimize the risk of aortic injury and optimize stenting. Case reports and small series have demonstrated that, with experienced operators and appropriate planning, percutaneous repair can achieve satisfactory outcomes even in these challenging anatomies.65

INNOVATIONS AND EMERGING TECHNIQUES

Advances in stent technology

Biodegradable stents

An alternative to bare-metal stents for children and newborns could be bioabsorbable polymers, such as PLLA (poly-L-lactic acid) and PLA (poly-lactic acid).71 These stents must provide structural support through their geometry; however, their lower strength compared with bare-metal metals makes them unsuitable for larger, stiffer vessels, such as the aorta.72,73 Currently, no polymeric bioabsorbable stents exist for treating AC in children.74 Despite this, bioresorbable stents could reduce the costs and risks associated with permanent implants. Advances in stent technology may soon provide biodegradable solutions, enabling nonsurgical management and allowing infants with AC to grow normally.

Expandable stents

One limitation of stenting in infants is the size of the delivery sheath required for stent implantation, which can later be redilated to accommodate somatic growth.75 Balloon-expandable stents are the gold standard for treating AC.76 However, self-expandable stents are still in the early stages of research, which may reduce the risk of stent fracture, vessel dissection, and aneurysm formation.77

Efforts to address growth challenges include the development of self-disrupting stents, such as the Growth stent (QualiMed, Germany), designed for AC. The device is composed of 2 halves of laser-cut, electropolished stainless steel, joined with bioabsorbable sutures to form a circular structure. The sutures are fully absorbed within 6 months, after which the 2 separate halves will remain safely in position without limiting natural growth, facilitating the implantation of a larger traditional stent that can potentially expand to adult dimensions. Despite initial promise, these stents ultimately failed due to high reintervention rates and inadequate growth adaptability.78

Modern strategies now focus on newer stent designs with low delivery profiles and high redilation potential, such as the Palmaz Genesis XD, Intrastent Mega, and Cheatham Platinum stent, the latter being the first approved for AC. These stents significantly reduce the risk of restenosis and the need for additional implantation. The Cheatham Platinum stent (NuMED, United States) is made from platinum and iridium wires arranged in a zigzag configuration capable of expanding to a diameter of up to 30 mm. Its significant dilation capability greatly reduces the need for additional stent implantation, leading to a lower rate of restenosis vs other devices.58,79

Emerging technologies include the Minima stent (Renata Medical, United States), designed for congenital vascular stenosis allows for an initial size < 4 mm for implantation at birth, with the possibility to expand to over 22 mm, maintaining structural integrity and radial strength,80 and the BeGrow stent (Bentley InnoMed, Germany), developed for pulmonary artery stenosis to allow for dilation up to 11.5 mm, which features controlled breaking points to accommodate growth and future interventions.81

Imaging and navigation enhancements

Three-dimensional (3D) printed models are proving invaluable for planning complex procedures in CHD.82,83 3D-printed models have demonstrated utility in surgical and percutaneous planning, including for aortic arch hypoplasia and transcatheter valve implantation. These models are created using imaging modalities such as CMR, CTA, or echocardiography, followed by segmentation and printing. While rigid models are ideal for stent positioning, flexible models assess vessel wall dynamics.83 Clinically, 3D printing enhances procedural precision, reduces complications, and shortens procedural time being beneficial for high-risk patients or challenging anatomies.

Future directions

Advanced imaging modalities, innovative stenting technologies,74 and hybrid approaches could enhance AC treatment results. Additionally, rigorous long-term follow-up protocols are crucial for monitoring treatment durability and assessing late complications in patients.

Unmet needs for percutaneous treatment exist, including non-standardized techniques and ideal approaches for different patient profiles.84,85 We need to refine patient selection criteria, enhance the management of complications, and collect more extensive long-term clinical data to ensure optimal outcomes and patient safety.

Finally, key research priorities in this field include conducting randomized clinical trials comparing new stent designs, optimizing stent implantation techniques, evaluating the role and timing of post-dilation, improving imaging modalities to guide and assess outcomes, determining the indications and optimal timing for percutaneous reintervention, and addressing the management of patients during the transition from pediatric to adult care.86

Without a doubt, artificial intelligence will play an important role in the percutaneous treatment of CHD. In the case of AC, it will enable a more precise analysis of imaging modalities to characterize its severity. Moreover, AI will enable better treatment planning, allowing selection of the most sui

CONCLUSIONS

Percutaneous stenting has become the standard of care for eligible patients with AC, supported by consistent procedural success and favorable long-term outcomes. Future research should focus on optimizing device design, pediatric adaptability, and standardized follow-up protocols.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this review.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: E. Flores-Umanzor, J. Galeano, O.A. Centurión, A. Ruberti; methodology: R. Luna-López, I. Morr-Verenzuela, P. Cepas-Guillén, S. Montserrat, S. Prat-González; validation: D. Pereda, R. Sanz-Ruiz, J.M. Carretero Bellón, O. Abdul-Jawad Altisent, S. Brugaletta, M. Sabaté, X. Freixa; writing -original draft preparation: V. Arévalos, A. Salazar-Rodríguez, G. Velázquez; writing-review and editing: V. Arévalos, A. Salazar-Rodríguez, G. Velázquez, B. Vidal, L. Sanchis, I. Anduaga, A. Fernandez- Cisneros; supervision: M. Sabaté, E. Flores-Umanzor. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Teo LL, Cannell T, Babu-Narayan SV, Hughes M, Mohiaddin RH. Prevalence of associated cardiovascular abnormalities in 500 patients with aortic coarctation referred for cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging to a tertiary center. Pediatr Cardiol. 2011;32:1120-1127.

2. Kim YY, Andrade L, Cook SC. Aortic Coarctation. Cardiol Clin. Aug 2020;38:337-351.

3. Ruhela M, Randhawa H, Bagarhatta P, Bagarhatta R, Jain A. Coarctation of Aorta with Supravalvular Pulmonary Stenosis in an Adult Patient:A Rare Exception of the Fetal Flow Pattern Theory. Am J Med Case Rep. 2015;3:53-58.

4. Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1890-1900.

5. Becker AE, Becker MJ, Edwards JE. Anomalies associated with coarctation of aorta:particular reference to infancy. Circulation. 1970;41:1067-1075.

6. Levy MJ, Levinsky L, Deviri E, Hauptman E, Blieden LC. Coarctation of the aorta in infancy. Tex Heart Inst J. 1983;10:57-62.

7. Mitchell ME. Aortic Coarctation Repair:How I Teach It. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104:377-381.

8. Chen B, Wei M. Aortic Coarctation. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:1420.

9. Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563-645.

10. Campbell M. Natural history of coarctation of the aorta. Br Heart J. 1970;32:633-40.

11. Mazzolai L, Teixido-Tura G, Lanzi S, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of peripheral arterial and aortic diseases. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3538-3700.

12. Kvitting JP, Olin CL. Clarence Crafoord:a giant in cardiothoracic surgery, the first to repair aortic coarctation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:342-346.

13. Singer MI, Rowen M, Dorsey TJ. Transluminal aortic balloon angioplasty for coarctation of the aorta in the newborn. Am Heart J. 1982;103:131-132.

14. Harris KC, Du W, Cowley CG, Forbes TJ, Kim DW. A prospective observational multicenter study of balloon angioplasty for the treatment of native and recurrent coarctation of the aorta. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83:1116-1123.

15. Cowley CG, Orsmond GS, Feola P, McQuillan L, Shaddy RE. Long-term, randomized comparison of balloon angioplasty and surgery for native coarctation of the aorta in childhood. Circulation. 2005;111:3453-3456.

16. O'Laughlin MP, Perry SB, Lock JE, Mullins CE. Use of endovascular stents in congenital heart disease. Circulation. 1991;83:1923-1939.

17. Suárez de Lezo J, Pan M, Romero M, et al. Balloon-expandable stent repair of severe coarctation of aorta. Am Heart J. 1995;129:1002-1008.

18. Forbes TJ, Kim DW, Du W, et al. Comparison of surgical, stent, and balloon angioplasty treatment of native coarctation of the aorta:an observational study by the CCISC (Congenital Cardiovascular Interventional Study Consortium). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2664-2674.

19. Gunn J, Cleveland T, Gaines P. Covered stent to treat co-existent coarctation and aneurysm of the aorta in a young man. Heart. 1999;82:351.

20. de Giovanni JV. Covered stents in the treatment of aortic coarctation. J Interv Cardiol. 2001;14:187-190.

21. Forbes T, Matisoff D, Dysart J, Aggarwal S. Treatment of coexistent coarctation and aneurysm of the aorta with covered stent in a pediatric patient. Pediatr Cardiol. 2003;24:289-291.

22. Lock JE, Castaneda-Zuniga WR, Bass JL, Foker JE, Amplatz K, Anderson RW. Balloon dilatation of excised aortic coarctations. Radiology. 1982;143:689-691.

23. Beekman RH, Rocchini AP, Dick M, 2nd, et al. Percutaneous balloon angioplasty for native coarctation of the aorta. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1987;10:1078-1084.

24. Rao PS. Balloon angioplasty of native coarctation of the aorta. J Invasive Cardiol. 2000;12:407-409.

25. Luijendijk P, Bouma BJ, Groenink M, et al. Surgical versus percutaneous treatment of aortic coarctation:new standards in an era of transcatheter repair. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2012;10:1517-1531.

26. Hernández-González M, Solorio S, Conde-Carmona I, et al. Intraluminal aortoplasty vs. surgical aortic resection in congenital aortic coarctation. A clinical random study in pediatric patients. Arch Med Res. 2003;34:305-310.

27. Rodés-Cabau J, MiróJ, Dancea A, et al. Comparison of surgical and transcatheter treatment for native coarctation of the aorta in patients >or =1 year old. The Quebec Native Coarctation of the Aorta study. Am Heart J. 2007;154:186-192.

28. Shaddy RE, Boucek MM, Sturtevant JE, et al. Comparison of angioplasty and surgery for unoperated coarctation of the aorta. Circulation. 1993;87:793-799.

29. Walhout RJ, Lekkerkerker JC, Ernst SM, Hutter PA, Plokker TH, Meijboom EJ. Angioplasty for coarctation in different aged patients. Am Heart J. 2002;144:180-186.

30. Fawzy ME, Fathala A, Osman A, et al. Twenty-two years of follow-up results of balloon angioplasty for discreet native coarctation of the aorta in adolescents and adults. Am Heart J. 2008;156:910-917.

31. Fletcher SE, Cheatham JP, Froeming S. Aortic aneurysm following primary balloon angioplasty and secondary endovascular stent placement in the treatment of native coarctation of the aorta. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1998;44:40-44.

32. Carr JA. The results of catheter-based therapy compared with surgical repair of adult aortic coarctation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1101-1107.

33. Hellenbrand WE, Allen HD, Golinko RJ, Hagler DJ, Lutin W, Kan J. Balloon angioplasty for aortic recoarctation:results of Valvuloplasty and Angioplasty of Congenital Anomalies Registry. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:793-797.

34. Rao PS, Thapar MK, Wilson AD, Levy JM, Chopra PS. Intermediate-term follow-up results of balloon aortic valvuloplasty in infants and children with special reference to causes of restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 1989;64:1356-1360.

35. Batlivala SP, Goldstein BH. Current Transcatheter Approaches for the Treatment of Aortic Coarctation in Children and Adults. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2019;8:47-58.

36. Reich O, Tax P, BartákováH, et al. Long-term (up to 20 years) results of percutaneous balloon angioplasty of recurrent aortic coarctation without use of stents. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2042-2048.

37. Zabal C, Attie F, Rosas M, Buendía-Hernández A, García-Montes JA. The adult patient with native coarctation of the aorta:balloon angioplasty or primary stenting?Heart. 2003;89:77-83.

38. Tzifa A, Ewert P, Brzezinska-Rajszys G, et al. Covered Cheatham-platinum stents for aortic coarctation:early and intermediate-term results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1457-1463.

39. Qureshi AM, McElhinney DB, Lock JE, Landzberg MJ, Lang P, Marshall AC. Acute and intermediate outcomes, and evaluation of injury to the aortic wall, as based on 15 years experience of implanting stents to treat aortic coarctation. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:307-318.

40. Tanous D, Collins N, Dehghani P, Benson LN, Horlick EM. Covered stents in the management of coarctation of the aorta in the adult:initial results and 1-year angiographic and hemodynamic follow-up. Int J Cardiol. 2010;140:287-295.

41. Chessa M, Carrozza M, Butera G, et al. Results and mid-long-term follow-up of stent implantation for native and recurrent coarctation of the aorta. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:2728-2732.

42. Stout KK, Daniels CJ, Aboulhosn JA, et al. 2018 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Adults With Congenital Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2019;139:e698-e800.

43. Bulbul ZR, Bruckheimer E, Love JC, Fahey JT, Hellenbrand WE. Implantation of balloon-expandable stents for coarctation of the aorta:implantation data and short-term results. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;39:36-42.

44. Ewert P, Abdul-Khaliq H, Peters B, Nagdyman N, Schubert S, Lange PE. Transcatheter therapy of long extreme subatretic aortic coarctations with covered stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;63:236-239.

45. Kenny D, Hijazi ZM. Coarctation of the aorta:from fetal life to adulthood. Cardiol J. 2011;18:487-495.

46. Krasemann T, Bano M, Rosenthal E, Qureshi SA. Results of stent implantation for native and recurrent coarctation of the aorta-follow-up of up to 13 years. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;78:405-412.

47. Koletsis E, Ekonomidis S, Panagopoulos N, Tsaousis G, Crockett J, Panagiotou M. Two stage hybrid approach for complex aortic coarctation repair. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:10.

48. Teixeira AM, Reis-Santos K, Anjos R. Hybrid approach to severe coarctation and aortic regurgitation. Cardiol Young. 2005;15:525-528.

49. Novosel L, Perkov D, Dobrota S, C´oric´V, Štern Padovan R. Aortic coarctation associated with aortic valve stenosis and mitral regurgitation in an adult patient:a two-stage approach using a large-diameter stent graft. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:494.e9-e14.

50. Russell TA, Quarto C, Nienaber CA. A single-stage hybrid approach for the management of severely stenotic bicuspid aortic valve, ascending aortic aneurysm, and coarctation of the aorta with a literature review. J Cardiol Cases. 2018;17:183-186.

51. Tacy TA, Baba K, Cape EG. Effect of aortic compliance on Doppler diastolic flow pattern in coarctation of the aorta. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1999;12:636-642.

52. Krieger EV, Stout KK, Grosse-Wortmann L. How to Image Congenital Left Heart Obstruction in Adults. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e004271.

53. Hedgire SS, Baliyan V, Ghoshhajra BB, Kalra MK. Recent advances in cardiac computed tomography dose reduction strategies:a review of scientific evidence and technical developments. J Med Imaging (Bellingham). 2017;4:031211.

54. Julsrud PR, Breen JF, Felmlee JP, Warnes CA, Connolly HM, Schaff HV. Coarctation of the aorta:collateral flow assessment with phase-contrast MR angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169:1735-1742.

55. Hom JJ, Ordovas K, Reddy GP. Velocity-encoded cine MR imaging in aortic coarctation:functional assessment of hemodynamic events. Radiographics. 2008;28:407-416.

56. Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J, 3rd, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease:A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146:e334-e482.

57. Malek R, Puckett Y, Agasthi P. Catheter Management of Coarctation. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing;2025. Available at: https://www.statpearls.com/physician/cme/activity/↻9/?specialty=specialty°=md.

58. Hatoum I, Haddad RN, Saliba Z, Abdel Massih T. Endovascular stent implantation for aortic coarctation:parameters affecting clinical outcomes. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2020;10:528-537.

59. Steiner I, Prsa M. Immediate results of percutaneous management of coarctation of the aorta:A 7-year single-centre experience. Int J Cardiol. 2021;322:103-106.

60. Nana P, Spanos K, Brodis A, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on Stenting for Aortic Coarctation Management in Adults. J Endovasc Ther. 2023:15266028231179919.

61. Yang L, Chua X, Rajgor DD, Tai BC, Quek SC. A systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes of transcatheter stent implantation for the primary treatment of native coarctation. Int J Cardiol. 2016;223:1025-1034.

62. Schleiger A, Al Darwish N, Meyer M, Kramer P, Berger F, Nordmeyer J. Long-term follow-up after endovascular treatment of aortic coarctation with bare and covered Cheatham platinum stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102:672-682.

63. Holzer RJ, Gauvreau K, McEnaney K, Watanabe H, Ringel R. Long-Term Outcomes of the Coarctation of the Aorta Stent Trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010308.

64. Feltes TF, Bacha E, Beekman RH, 3rd, et al. Indications for cardiac catheterization and intervention in pediatric cardiac disease:a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2607-2652.

65. Pan M, Pericet C, González-Manzanares R, et al. Very long-term follow-up after aortic stenting for coarctation of the aorta. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2024;77:332-341.

66. Morgan T. Turner syndrome:diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:405-410.

67. Donadille B, Christin-Maitre S. Heart and Turner syndrome. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2021;82:135-140.

68. Zanjani KS, Thanopoulos BD, Peirone A, Alday L, Giannakoulas G. Usefulness of stenting in aortic coarctation in patients with the Turner syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1327-1331.

69. Bons LR, Van Den Hoven AT, Malik M, et al. Abnormal Aortic Wall Properties in Women with Turner Syndrome. Aorta (Stamford). 2020;8:121-131.

70. Kische S, D'Ancona G, Stoeckicht Y, Ortak J, Elsässer A, Ince H. Percutaneous treatment of adult isthmic aortic coarctation:acute and long-term clinical and imaging outcome with a self-expandable uncovered nitinol stent. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e001799.

71. Qiu TY, Song M, Zhao LG. A computational study of crimping and expansion of bioresorbable polymeric stents. Mech Time Depend Mater. 2018;22:273-290.

72. Borghi Jr TC, Costa Jr JR, Abizaid A, et al. Comparação da retração aguda do stent entre o suporte vascular bioabsorvível eluidor de everolimus e dois diferentes stents metálicos farmacológicos. Rev Bras Cardiol Invasiva. 2013;21.

73. Veeram Reddy SR, Welch TR, Wang J, et al. A novel design biodegradable stent for use in congenital heart disease:mid-term results in rabbit descending aorta. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;85:629-639.

74. Veeram Reddy SR, Welch TR, Nugent A. Biodegradable Stent Use For Congenital Heart Disease. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology. 2021;61:101349.

75. Goldstein BH, Kreutzer J. Transcatheter Intervention for Congenital Defects Involving the Great Vessels:JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:80-96.

76. Zablah JE, Morgan GJ. Pulmonary Artery Stenting. Interv Cardiol Clin. 2019;8:33-46.

77. Sadeghipour P, Mohebbi B, Firouzi A, et al. Balloon-Expandable Cheatham-Platinum Stents Versus Self-Expandable Nitinol Stents in Coarctation of Aorta:A Randomized Controlled Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:308-317.

78. Ewert P, Peters B, Nagdyman N, Miera O, Kühne T, Berger F. Early and mid-term results with the Growth Stent--a possible concept for transcatheter treatment of aortic coarctation from infancy to adulthood by stent implantation?Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;71:120-126.

79. Cheatham JP. Stenting of coarctation of the aorta. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2001;54:112-125.

80. Zahn EM, Abbott E, Tailor N, Sathanandam S, Armer D. Preliminary testing and evaluation of the renata minima stent, an infant stent capable of achieving adult dimensions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:117-127.

81. Quandt D, Knirsch W, Michel-Behnke I, et al. First-in-man pulmonary artery stenting in children using the Bentley®BeGrow™stent system for newborns and infants. Int J Cardiol. 2019;276:107-109.

82. Pluchinotta FR, Giugno L, Carminati M. Stenting complex aortic coarctation:simulation in a 3D printed model. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:490.

83. Ghisiawan N, Herbert CE, Zussman M, Verigan A, Stapleton GE. The use of a three-dimensional print model of an aortic arch to plan a complex percutaneous intervention in a patient with coarctation of the aorta. Cardiol Young. 2016;26:1568-1572.

84. Khalaj R, Tabriz AG, Okereke MI, Douroumis D. 3D printing advances in the development of stents. Int J Pharm. 2021;609:121153.

85. Capelli C, Sauvage E, Giusti G, et al. Patient-specific simulations for planning treatment in congenital heart disease. Interface Focus. 2018;8:20170021.

86. Rigatelli G, Chiastra C, Pennati G, Dubini G, Migliavacca F, Zuin M. Applications of computational fluid dynamics to congenital heart diseases:a practical review for cardiovascular professionals. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2021;19:907-916.