ABSTRACT

Percutaneous left atrial appendage closure has emerged as a promising procedure for patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation with a very high or prohibitive bleeding risk. It is a safe technique, with a low rate of complications; however, complications, such as device embolization can be potentially serious, and decision-making as well as selecting the most appropriate strategy may be challenging due to the limited evidence available in this context. This review provides an overview of the most critical aspects of left atrial appendage closure device embolization focusing on its prevalence, management strategies, and treatment options.

Keywords: Left atrial appendage closure. Embolization. Devices.

RESUMEN

El cierre percutáneo de la orejuela izquierda ha ido emergiendo como un procedimiento cada vez más prometedor para pacientes con fibrilación auricular no valvular y riesgo hemorrágico muy alto o prohibitivo. Se trata de una técnica segura, con un porcentaje de complicaciones bajo; sin embargo, algunas de ellas, como la embolización del dispositivo, pueden ser graves, y la toma de decisiones y la estrategia más adecuada pueden ser difíciles debido a la escasa evidencia disponible. La presente revisión proporciona un resumen de los aspectos más importantes sobre la embolización de dispositivos de cierre de la orejuela izquierda, tanto en su prevalencia como en su abordaje y las opciones de tratamiento.

Palabras clave: Cierre de orejuela. Embolización. Dispositivos

Abreviaturas

LAA: left atrial appendage. LV: left ventricle. TEE: transesophageal echocardiogram.

INTRODUCTION

Atrial fibrillation has become the most common arrhythmia of our time. Its estimated prevalence in the Spanish population is 4.4% among individuals older than 40 years, which, in absolute numbers, translates into > 1 million Spaniards living with this rhythm disorder.1 There has been solid evidence for years regarding its association with an increased rate of stroke and cardiovascular mortality in both sexes,2,3 which is why therapeutic-dose anticoagulation a fundamental pillar in the treatment of these patients. However, in patients with high or prohibitive bleeding risk, percutaneous left atrial appendage closure has emerged as a reasonable and noninferior alternative to anticoagulation regarding cardioembolic events, cardiovascular mortality, and clinically relevant hemorrhage.4

Although intraoperative and post-implantation complication rates remain low, the increasing global use of these devices has led to a current embolization rate of approximately 0%–1.5% of all procedures.5

This review summarizes the available evidence on embolization of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure devices, including a description of currently available devices, potential predictors of embolization, and recommended management strategies.

TYPES OF DEVICES

Below is a brief description of the 3 device families currently available in our setting.

WATCHMAN family

WATCHMAN devices (Boston Scientific, United States) are single-lobe occlusion systems implanted approximately 10 mm from the left atrial appendage coronary ostium, leaving the ostial opening uncovered.

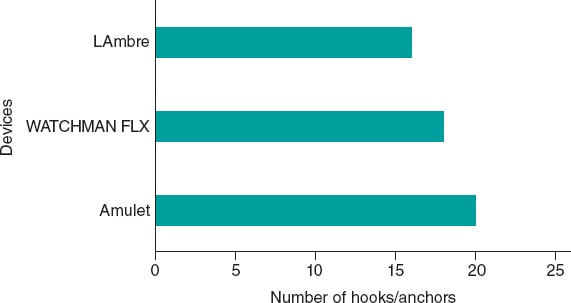

In 2020, Boston Scientific released the next-generation WATCHMAN FLX, which in a meta-analysis of 54 727 patients demonstrated superiority over its predecessor, WATCHMAN 2.5, in cardiovascular mortality, major hemorrhage, pericardial effusion, and device embolization.6,7 These advantages are partly attributed to its smaller metal surface—reducing the risk of thrombosis—and its greater number of anchors (18 vs 10), which enhance adaptation to the ostium and reduce residual leaks.6,7 It is available in 5 sizes, covering ostial diameters from 14 mm to 31.5 mm.

In 2024, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the WATCHMAN FLX Pro device, which features a fluoropolymer-coated fabric membrane designed to enhance thromboresistance and promote endothelialization, potentially allowing shorter postoperative antithrombotic regimens. It has shown promising results in published case reports.8 A single-center study, the WATCHMAN FLX PRO CT trial (NCT05567172), is currently underway to evaluate the morphology and tissue coverage of the device surface 90 days after implantation. The device has not yet received CE (Conformité Européenne) marking for commercialization in Europe.

Amplatzer family

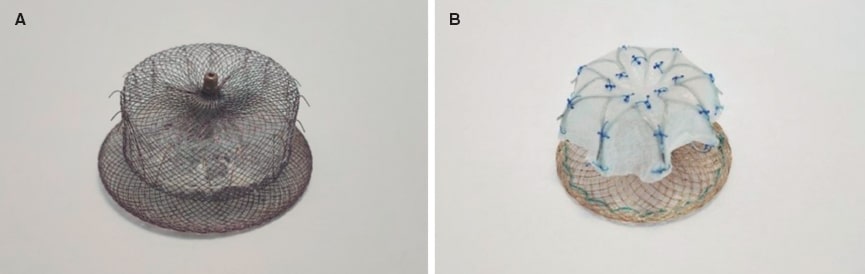

In 2013, the second-generation Amplatzer Amulet (Abbott, United States) received the CE marking (figure 1A). It features a closure lobe—usually implanted 10 mm to 15 mm away from the coronary ostium—and a disc that fully covers the ostial opening. The 2 components are connected by a central waist. Device sizing is based on the appendage landing zone, the region where the lobe rests. Sizes range from 16 mm to 34 mm to accommodate landing zones from 11 mm to 31 mm.9

Figure 1. A: Amplatzer device. B: LAmbre device.

The Amulet IDE trial10, which compared the Amplatzer Amulet with the first-generation WATCHMAN device, found a higher rate of left atrial appendage occlusion with the dual-seal device. Furthermore, the study demonstrated the noninferiority of the Amulet regarding its safety and efficacy profile in stroke reduction among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. However, the rate of adverse events, such as pericardial effusion and device embolization, was nearly twice as high, a finding likely influenced by the greater operator experience at the time with WATCHMAN devices, which may have contributed to higher complication rates with the Amplatzer system.10 Noninferiority findings remained consistent at 5 years, with a significantly higher proportion of patients free from prescribed anticoagulation in the Amulet group (94% vs 91%; P = .009) and a very low annual stroke rate in the 2 groups (1.6% per year), although the rate of fatal stroke was higher in the WATCHMAN group (1.9% vs 1.2%; P = .03).11

A study comparing the 2 generations of Abbott devices concluded that the second-generation system exhibited a lower rate of residual peridevice leaks, with no significant differences in major complications, mortality, or implantation success.12

LAmbre

LAmbre (Lifetech Scientific Corporation, China) is a dual-seal (lobe and disc) occluder (figure 1B). It is available in 15 different sizes (from 16 mm to 36 mm) and is made of a nitinol mesh and polyester membrane. Its design includes 8 distal hooks and 8 U-shaped hooks that enhance stabilization by improving anchoring within the trabeculations. It received the CE marking in 2016.

In a prospective multicenter Chinese study of 103 patients, the LAmbre device achieved a 98.05% implantation success rate. Postoperative pericardial effusion within the first 7 days was reported in 4.95% of patients, none requiring intervention. One patient experienced a stroke at 2 months in the context of reduced anticoagulant dosing. Although there was no device-related thrombosis, mean follow-up was only 12.2 months.13

A unique advantage of this device is the possibility of custom manufacturing for anatomically complex or out-of-range appendages.

INCIDENCE RATE OF EMBOLIZATION

Left atrial appendage embolization—whether into a cardiac chamber, a great vessel, or a peripheral artery—is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication, with reported mortality rates of up to 10.2% in published registries. The experience of interventional cardiologists or electrophysiologists performing device implantation, as well as the number of procedures performed annually at each hospital, has been significantly associated with differences in the incidence rate of embolization (0.6% in high-volume centers vs 1.5% in low-volume centers).5

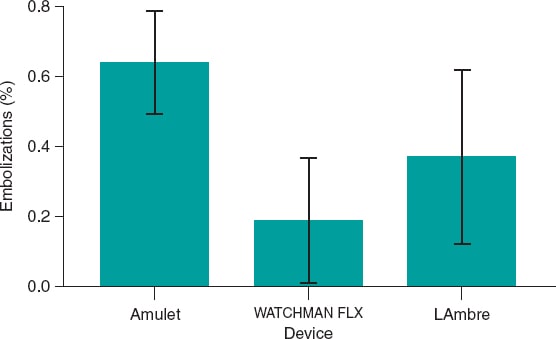

The relationship between device type and the rate of embolization is still to be elucidated. The WATCHMAN FLX has demonstrated a lower rate vs its predecessor, the WATCHMAN 2.5 (odds ratio, 0.35; 95%CI, 0.18-0.70; P < .02), as shown in a 2023 meta-analysis including 54 727 patients,6 and an embolization rate of 0% in the PINNACLE FLX study.7

For the Amulet device, the Amulet IDE trial—which compared the Amulet with the first-generation WATCHMAN—reported embolization rates of 0.6% and 0.2%, respectively. Nonetheless, the authors suggested that this difference was partly attributable to the lower operator experience with Amulet at that time.10 In the 2021 SWISS-APERO trial comparing Amulet with WATCHMAN FLX, the embolization rate reached 0.9% of patients in each group.14

A 2020 systematic review of 403 patients reported zero embolization events with the LAmbre device.15 In contrast, a 2024 German study including 118 patients reported an embolization rate of 1.7%; however, procedures were performed without contrast, representing an important limitation when interpreting this higher rate of complications.16 Spanish series have reported embolization rates close to 0%,17-18 while an initial Brazilian experience reported an embolization rate of 2% (1 of 51 patients).19

Therefore, taken together, these data suggest that the overall rate of device embolization is approximately 1%, with no consistent, clinically meaningful differences among the various devices.

Of note, not only device-related characteristics but also the anatomic and morphologic features of the appendage are among the factors influencing embolization. Cactus-type appendages—those with a dominant central lobe giving rise to numerous small secondary lobes—have been associated with a higher risk of embolization. Similarly, shallow appendages and those with wide necks have been associated with a higher risk of device embolization.20-21

Although the patient cardiac rhythm has been proposed as a potential contributor to the risk of embolization, its role is not fully understood. It has been suggested in published case reports22 that a contractile appendage—that is, one in sinus rhythm—may have a higher risk of device migration or embolization due to greater contractile force vs atrial fibrillation. Furthermore, rhythm conversion, whether from sinus rhythm to atrial fibrillation or vice versa, has been proposed as a mechanism that could facilitate embolization.

A retrospective analysis of WATCHMAN device embolizations using data from the NCDR LAAO registry23 concluded that patients in sinus rhythm at the time of implantation seemed to have a higher risk of late embolization (within the first 45 days after discharge), possibly because active appendage contraction in sinus rhythm may lead to underestimating the ostial size. If the patient subsequently transitions to atrial fibrillation, a state in which the appendage is typically more dilated, the device may become undersized predisposing migration.23

Regarding timing, the review by Eppinger et al.5 showed that device embolization occurred more commonly in the acute period (within the first 24 hours after implantation), except in peripheral arteries, where late embolization (> 45 days) was a more prevalent finding.

Table 1, figure 2, and figure 3 illustrate the characteristics of all devices and their rates of embolization.

Table 1. Characteristics and embolization rates of CE-marked devices

| Device | CE year | Specific characteristics | Embolization rates |

|---|---|---|---|

| WATCHMAN FLX, Boston Scientific | 2019 | Umbrella-shaped design

Smaller metallic surface than its predecessor 18 fixation hooks |

PINNACLE FLX,7 2021: 0 %

SWISS-APERO,14 2021: 0.9% SEAL-FLX,24 2022: 0% Della Rocca et al.,25 2022: 0% SURPASS FLX,26 2024: 0.04% |

| Amplatzer Amulet, Abbott | 2013 | Proximal disc and distal lobe

Proximal disc independent of the lobe, without screw 10 pairs of hooks on the distal disc Waist length up to 20 mm (greater adaptability) Disc diameter 40% larger than the lobe |

Kleinecke et al.,12 2020: 0.9%

AMULET IDE,10 2021: 0.6% SWISS-APERO,14 2021: 0.9% SEAL-FLX,24 2022: 0.7% Della Rocca,25 2022: 0.1% |

| LAmbre, Lifetech | 2016 | Adjustable umbrella + polyester cover 8 radial U-shaped hook pairs

Wide size range (up to 40 mm) |

Cruz-González et al.,18 2018: 0%

Li et al.,27 2018: 0% Park et al.,28 2018: 0% Huang et al.,29 2019: 0% Ali et al.,15 2020: 0% Llagostera-Martín et al.,17 2021: 0% Wang et al.,30 2021: 0% Chamié et al.,19 2022: 2% Chen et al.,31 2022: 0% Vij et al.,16 2024: 1.7% (non-contrast protocol) |

Figure 2. Bar chart showing the percentage of embolizations for each device.

Figure 3. Devices and number of hooks and anchors they incorporate.

TECHNIQUES TO REDUCE THE RISK OF DEVICE EMBOLIZATION

Multiple factors related to left atrial and appendage anatomy, the procedural technique being used, and device selection may increase the risk of embolization. In May 2023, a consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions and the Heart Rhythm Society reviewed key considerations for left atrial appendage closure and associated complications.32 Table 2 illustrates the most relevant points. Selecting the correct device size is essential, as both over- and undersizing increase the risk of embolization. Additionally, operators should be well trained and familiar with the implantation technique (at least 25 transseptal punctures and, at least, of 10 appendage closures as primary operator are recommended), and retrieval techniques (requiring expertise with large-bore introducer sheaths and snare systems). Various imaging modalities can be used throughout the procedure.

Table 2. Prevention of embolization across the different phases of the procedure

| Preoperative | Intraoperative | Postoperative |

|---|---|---|

| Correct device sizing (avoid over- and undersizing) | Intraoperative guidance using 2D/3D TEE and fluoroscopy | Immediate postoperative verification with TTE for early detection of embolization |

| Adequate operator training (at least 25 transseptal punctures and 10 LAA closures) | Proper performance of the tug test (although its utility is still under discussion) | Pre-discharge evaluation with TTE |

| Use of preoperative imaging: 2D/3D TEE at multiple angles or CT | Fulfillment of PASS (WATCHMAN) or CLOSE criteria (Amplatzer) before releasing the device | Follow-up imaging at 45–90 days with TEE or CT |

| 3D CT is superior to TEE for procedural planning | ||

| Avoid markedly depleted atria (< 12 mmHg) | ||

|

2D, bidimensional; 3D, tridimensional; CT, computed tomography; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography. |

||

- – A targeted transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) should be performed, acquiring bidimensional images in 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°. Three-dimensional TEE should be used on a routine basis because it provides more accurate sizing. Cardiac CT is increasingly recognized as superior to TEE for procedural planning due to its better spatial resolution and more precise identification of maximal landing zone diameter. Furthermore, three-dimensional reconstructions provide volumetric visualization of the appendage, enhance device-size prediction, and in some cases allow virtual implantation and planning of access routes and transseptal puncture sites.20

- – In the intraoperative period, the procedure should be guided by fluoroscopy and bidimensional/tridimensional TEE. Although three-dimensional intracardiac echocardiography is emerging as another available imaging modality, it is currently more expensive and complex than TEE, requiring placement of the probe within the left atrium (LA). LA pressure should be measured during the procedure, as underfilled atria tend to produce inaccurate measurements. An important aspect is measuring LA pressure during the procedure, as markedly depleted atria have been shown to produce inaccurate measurements. In general, a LA pressure ≥ 12 mmHg is recommended for correct interpretation. In cases of low atrial pressure, IV fluids may be administered until appropriate parameters are achieved.32

- – In the immediate postoperative period proper device positioning must be confirmed, and pericardial effusion or other complications must be excluded.

- – Before discharge, a transthoracic echocardiogram is essential because most embolizations occur within the first 24 hours after implantation.33,34

- – During follow-up, a TEE or cardiac CT is recommended at 45–90 days.

Manufacturers of the WATCHMAN and Amplatzer devices recommend a series of intraoperative steps to ensure proper device implantation; all criteria must be met before the device is released.

WATCHMAN devices follow the PASS (position, anchor, size, seal) acronym, while Amplatzer devices follow CLOSE (circumflex, lobe, orientation, separation, elliptical), outlined in table 3.

Table 3. PASS and CLOSE criteria for WATCHMAN and Amplatzer devices

| Criteria | PASS (WATCHMAN) | CLOSE (Amplatzer) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Position: adequate coverage of the ostium, immediately distal to or at the ostium | Circumflex: the device lobe should be positioned one-third to two-thirds distal to the left circumflex artery |

| 2 | Anchoring: gentle traction test without displacement of the device | Lobe: “tyre-like” appearance when compressed |

| 3 | Size: device compression between 8% and 20% of its original size | Orientation: the device lobe must be coaxial with the left atrial appendage wall |

| 4 | Seal: residual leak < 5 mm; all lobes fully covered | Adequate separation between the lobe and the disc |

| 5 | Elliptical: the disc should be under tension, showing a concave appearance |

An important aspect of the intraoperative performance of the “tug test,” which is used to assess the stability of the implanted device. This maneuver consists of applying controlled traction to the device once it has been deployed within the appendage, with the aim of confirming that it is securely anchored and will not migrate. Its use is widespread worldwide and it is now performed routinely. However, in 2020, a study evaluated its efficacy profile by implanting a device in the primary introducer sheath equipped to measure the traction force in Newtons.35 The device used was the Amulet, and the investigators found that the force applied by the operator while releasing the device exceeded the force applied during the subsequent tug test, both for larger devices (2.96 ± 0.57 vs 1.04 ± 0.24 N; P < .001) and for devices < 25 mm (1.72 ± 0.43 vs 1.01 ± 0.59 N; P = .049). Thus, the authors concluded that the tug test was redundant. Notably, all 23 implants in the study fulfilled the manufacturer-recommended CLOSE criteria.

MANAGEMENT OF DEVICE EMBOLIZATION

The approach and management of embolizations fundamentally depend on 3 factors: the size of the embolized device, the site to which it has migrated, and the patient’s hemodynamic status. In the review conducted by Eppinger et al.,5 the most frequent migration site was the aorta (37%), followed by the left ventricle (LV) (33.3%), the LA (24.3%), and peripheral arteries (4.6%). Moreover, the authors concluded that embolization into the LV or the mitral subvalvular apparatus was associated with the highest degree of complications and the greatest need for surgery (44.4%). In the systematic review conducted by Aminian et al.,34 the predominant site of embolization was split between the aorta and the LV (30% each), with the WATCHMAN device showing a predilection for the aorta (7 out of 9 cases) and the Amplatzer Cardiac Plug (Abbott, United States; no longer marketed in Spain) for the LV (6 out of 9 cases). In this review, all devices > 25 mm were lodged in the LA or the LV. In the LAAODE trial,33 the most frequent site of embolization remained the aorta (30%), followed by the LA (24%) and the LV (20%).”

Once embolization occurs, 2 main approaches exist:

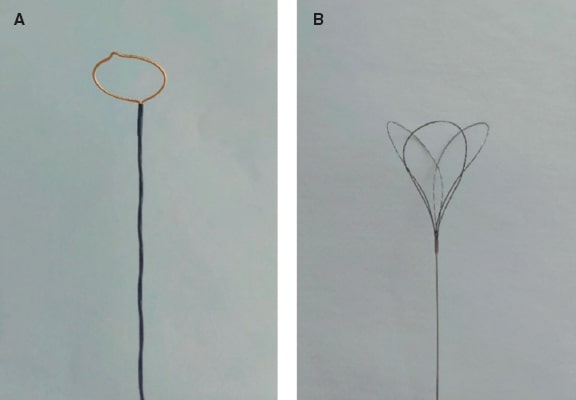

- – Percutaneous retrieval: via transarterial or transseptal access. Although single or multiple snares are widely used, myocardial biopsy forceps have been described.36 Technique depends on device size, location, and anatomy. Alkhouli et al.36 give a series of recommendations: single snares work best for large devices; the introducer sheath should be 2-Fr - 4-Fr larger than the size of the sheath required for device implantation; nitinol devices (eg, Amplatzer) can be folded and withdrawn into the introducer sheath, whereas non-nitinol devices (eg, WATCHMAN) require greater deformation for extraction. Table 4, table 5, and table 6 list snares, forceps, biotomes, and catheters useful for percutaneous retrieval according to the European Device Guide.37 Figure 4 illustrates examples of single- and triple-loop snares.

- – Surgical retrieval: more invasive, with longer hospitalization and higher mortality rates.36 Indicated in cases of severe valvular damage or need for ventricular repair.

Table 4. Snares useful for recapturing an embolized device

| Snare | Manufacturer | Introducer sheath (Fr) | Loop length (cm) | Catheter length (cm) | Usable loop diameter (mm) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GooseNeck MicroSnare | Medtronic | 2.3-3 | 175; 200 | 150 | 2; 4; 7 | Single 90° loop; gold-plated tungsten coils |

| GooseNeck Snare | Medtronic | 4; 6 | 120 | 102 | 5; 10; 15; 20; 25; 30; 35 | Similar to MicroSnare |

| EN Snare standard | Merit Medical | 6; 7 | 120 | 100 | 6-10; 9-15; 12-20; 18-30; 27-45 | 3 intertwined loops |

| EN Snare Mini | Merit Medical | 3.2 | 175 | 150 | 2-4; 4-8 | Similar to the EN Snare Standard |

| One Snare standard | Merit Medical | 4; 6 | 120 | 100 | 5; 10; 15; 20; 25; 30; 35 | Capture loop with a single 90° angle, gold-plated tungsten coating |

| One Snare Micro | Merit Medical | 2.3-3 | 175; 200 | 150; 175 | 2; 4; 7 | Similar to the One Snare standard |

| Atrieve Snare | Argon Medical Devices, Inc. | 3.2; 6; 7 | 120; 175 | 100; 150 | 2-4; 4-8; 6-10; 9-15; 12-20; 18-30; 27-45 | 3 superimposed, non-intertwined loops |

| Bard Snare Kit | BD Interventional | 9; 11 | 120 | 63; 58 | 20 | Radiopaque 90° capture loop |

| CloverSnare 4-Loop Vascular Retrieval System | Cook Medical | 6 | 90 | 85 | 32 | 4-loop nitinol snare with tantalum core |

| Multi-Snare | PFM Medical | 3; 4; 5; 6 | 125; 175 | 105; 150 | 2-3; 4-6; 5-8; 10-15; 15-20; 20-30; 30-40 | Dual-plane retrieval system |

Table 5. Forceps and bioptomes useful for recapturing embolized devices

| Forceps / Bioptome | Manufacturer | Introducer sheath (Fr) | Length (cm) | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard biopsy forceps | Cordis | 5.5; 7 | 50; 104 | Available in straight and curved jaws |

| Procure endomyocardial biopsy forceps | Abbott | 5.4–7 | 50; 105 | Available in straight and curved jaws |

| Raptor* grasping device | US Endoscopy | 7 | 230 | 360° rotation |

| Needle’s Eye retrieval system | Cook Medical | 16 | 54; 94 | Stainless-steel/nitinol guidewire; widely used for cardiac lead extraction |

| Adjustable Lasso catheter | Biosense Webster | 7 | 115 | Mapping catheter used in electrophysiology |

| ŌNŌ retrieval device | B. Braun Interventional Systems, Inc. | 7.5 | 100 | 35-mm self-expanding nitinol basket |

| Cardiology grasping forceps with 3 plate claws | H + H Maslanka | 5.4 | 120 | 3 retractable claws |

|

* Intravascular use of this device is considered off-label. |

||||

Table 6. Catheters and introducer sheaths useful for recapturing embolized devices

| Catheter / Introducer sheath | Manufacturer | Size (Fr) | Length (cm) | Shape | Guidewire compatibility (inches) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extra-large Check-Flo | Cook Medical | 20-24 | 25; 40; 65 | Rigid | 0.038 |

| Gore DrySeal Flex introducer sheath | Gore & Associates | 10; 12; 14; 15; 16; 18; 20; 22; 24; 26 | 33; 45; 65 | Flexible | 0.035 |

| MitraClip delivery system | Abbott | 24 | 80 | Flexible | 0.035 |

| Keller–Timmermans | Cook Medical | 18-24 | 65; 85 | Available straight and curved | 0.038 |

| Destino bidirectional guiding catheter with hemostatic valve | Oscor Inc. | 8.5; 10; 12 | 67; 71; 73; 75; 77 | Available straight and curved | 0.038 |

Figure 4. A: Amplatz gooseneck snare as an example of a single-loop retrieval device. B: EN Snare device showing its 3 interlaced loops.

In percutaneous retrieval, Fahmy et al.,38 in their ex vivo experience, required larger introducer sheaths to retrieve WATCHMAN devices than those used to retrieve Amplatzer Cardiac Plug–type devices. They emphasized the need for a larger “gooseneck” snare (preferably 15 mm–20 mm) to facilitate engagement of the WATCHMAN anchors, as well as a larger sheath (ideally 18-Fr) to allow easier retraction of the device. Other options include capturing the device centrally or laterally, although substantially greater traction force is required to withdraw the WATCHMAN into the sheath. Two operators should participate in the retrieval attempt: one to stabilize the sheath and the other to firmly pull the captured device into it.38

As mentioned above, device embolization into the LV can cause hemodynamic instability and often requires surgical retrieval. Percutaneous retrieval is especially challenging due to the risk of damaging the aortic and mitral valves. Stabilizing guidewires, especially when the device has been released, may become entangled in surrounding structures and cause tissue damage. Abbadi et al.39 reported a case of Amulet embolization into the LV entrapping the mitral subvalvular apparatus and causing severe mitral regurgitation. Retrieval was achieved using a 35-mm Amplatz snare inserted through a 24-Fr MitraClip system (Abbott, United States), allowing the device to be captured by its central waist, pulled into the LA, and withdrawn into the MitraClip catheter. The patient remained stable with mild mitral regurgitation.

Research is currently underway on specific materials and systems designed to facilitate the capture, repositioning, and retrieval of devices. One of these is the O–NO– device (B. Braun, Germany), which consists of a 35-mm self-expanding nitinol basket attached to a 12-Fr catheter with a 7.5-Fr internal lumen. In a 3-case series published in 2024 (2 with migration to the LA and 1 to the LVOT beneath the aortic valve), the O–NO– device achieved a 100% retrieval success rate, with no complications40.

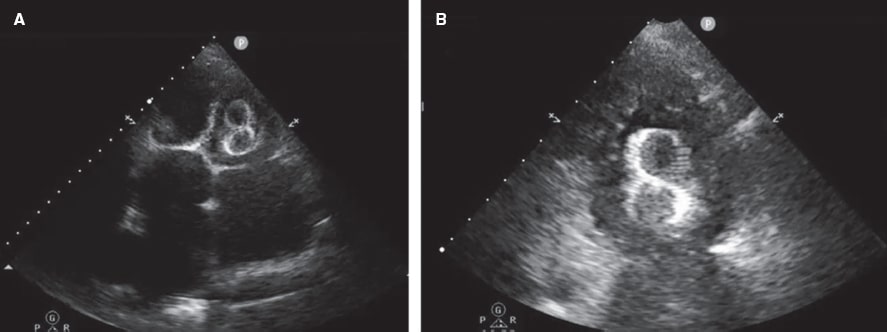

Figure 5 and figure 6 illustrate examples of left atrial appendage device embolization.

Figure 5. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and fluoroscopy of left atrial appendage closure with a 25-mm Amulet device. A: the device migrated to the left ventricle (LV). B: an 8-Fr JR4 guiding catheter with a 20-mm snare was introduced via left femoral access, capturing the device by the distal lobe screw and allowing it to be pulled into the descending aorta. C: afterwards, the right femoral artery was cannulated with a 16-Fr introducer sheath; using a guiding catheter and a 30-mm snare, the device was again captured by the distal lobe screw, pulled back, and finally extracted.

Figure 6. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) performed 24 hours after implantation of a 38-mm LAmbre device. A: migration to the left ventricle (LV), with entrapment in the mitral subvalvular apparatus. B: magnified image.

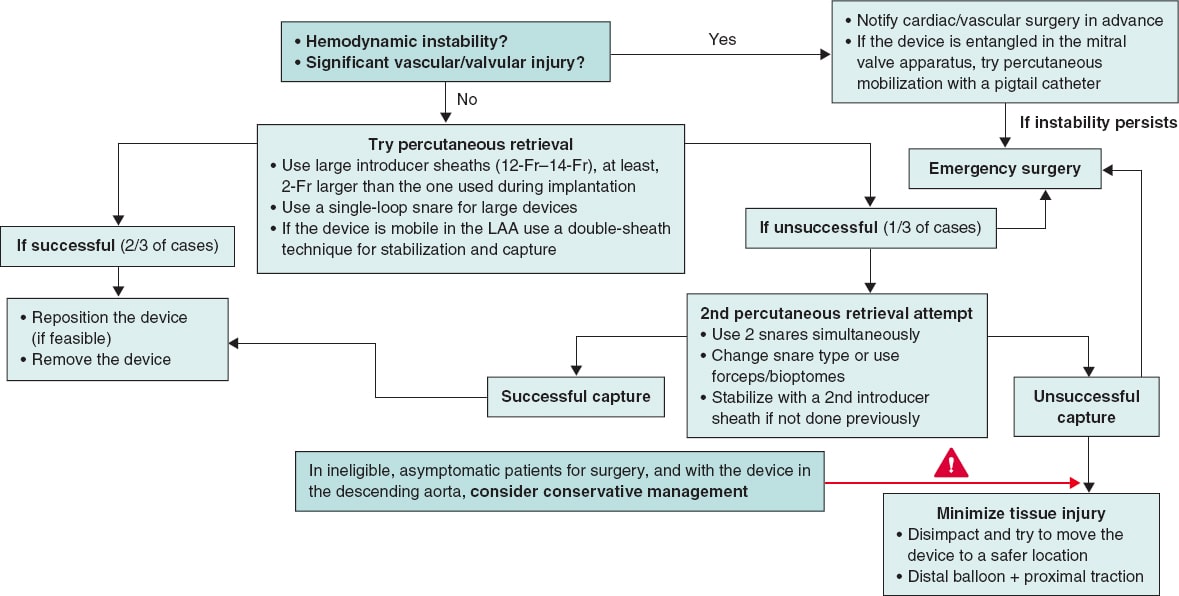

TREATMENT ALGORITHMS

Several algorithms have been published with the aim of providing guidance and helping the operator in the decision-making process. In all of them, it is considered that if the patient is hemodynamically stable and there is no significant vascular or valvular damage, the percutaneous retrieval technique should be the first-line approach (76.4% vs 21.7% of patients who required open cardiac surgery as an initial strategy in the series by Eppinger et al.5, of whom 60% exhibited embolization to the LV), always taking into account that embolization into a cardiac chamber carries higher risk than embolization into a large or peripheral vessel.36 If the first attempt is successful, it is acceptable to either try to reposition the device in its correct location or remove it from the patient and schedule a new implant.

If the first percutaneous attempt is unsuccessful—something that occurs in approximately one-third of the patients—a second percutaneous attempt may be performed, or the operator may proceed directly to open cardiac surgery, while bearing in mind that a failed first attempt increases mortality rate from 2.9% to 21.4%.5

If the second attempt fails too, and the patient is ineligible for surgery, Alkhouli et al.36 propose several options, such as trying to disimpact the device and reposition it in a less anatomically compromised area, inflating a balloon distal to the device to apply traction and facilitate its mobilization to a safer position, and even using 2 snares simultaneously.

Finally, in patients with prohibitive surgical risk who remain asymptomatic, and only when the device is lodged in the descending aorta, conservative management with periodic follow-up is an option, although it is unclear how often follow-up should be performed or what antithrombotic or anticoagulant therapy should be administered.

Figure 7 proposes a management and treatment algorithm according to the latest evidence available, summarizing the information presented above.

Figure 7. Proposed treatment algorithm for the embolization of a left atrial appendage (LAA) closure device.

CONCLUSIONS

Left atrial appendage occlusion device embolization is a rare but potentially fatal complication in a procedure that has proven safe and effective for stroke prevention in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation who cannot take anticoagulation. Although device designs have evolved over the past few years, appropriate patient selection, meticulous preprocedural planning, and precise procedural execution remain essential to minimize the risks. This review highlights the multifactorial complexity and numerous contributing factors involved. When embolization occurs, percutaneous retrieval should be the initial approach when feasible, reserving surgery for specific cases, such as valvular disruption, hemodynamic instability, or failed percutaneous attempt. Development of specialized retrieval tools and standardized management algorithms will help optimize the outcomes. Future research should focus on identifying more precise anatomical and technical predictors and validating universal preventive strategies.

FUNDING

None declared.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used in preparing this review.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M.Á. Martín-Arena and G. Galeote-García conducted the literature search, collected data, and drafted the initial and final versions of the manuscript. A. Lara-García, A. Jurado-Román, S. Jiménez-Valero, A. Gonzálvez-García, D. Tébar-Márquez, B. Rivero-Santana, J. Zubiaur, M. Basile, S. Valbuena-López, L. Fernández-Gassó, R. Dalmau González-Gallarza, and R. Moreno provided images, figures, and data, critically reviewed the text, and contributed to the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Moreno is associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology. The journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed; additionally, he has received speaker and consultant fees from Abbott, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific. A. Gonzálvez declared to have received speaker fees from Abbott. G. Galeote declared to have received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and M.A. Jurado is a proctor for Abbott and Boston Scientific and declared to have received speaker fees from both. M. Basile declared to have received conference attendance fees from Abbott.

REFERENCES

1. Gómez-Doblas JJ, Muñiz J, Martin JJA, et al. Prevalence of Atrial Fibrillation in Spain. OFRECE Study Results. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2014;67:259-269.

2. Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial Fibrillation:A Major Contributor to Stroke in the Elderly:The Framingham Study. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1561-1564.

3. Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Benjamin EJ, Levy D. Prevalence, incidence, prognosis, and predisposing conditions for atrial fibrillation:population-based estimates 1. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(7, Suppl 1):2N-9N.

4. Osmancik P, Herman D, Neuzil P, et al. 4-Year Outcomes After Left Atrial Appendage Closure Versus Nonwarfarin Oral Anticoagulation for Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:1-14.

5. Eppinger S, Piayda K, Rodes-Cabau J, et al. Embolization of percutaneous left atrial appendage closure devices:timing, management and associated clinical outcomes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(Suppl 2):ehad655.2276.

6. Najim M, Reda Mostafa M, Eid MM, et al. Efficacy and safety of the new generation WATCHMAN FLX device compared to the WATCHMAN 2.5:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2023;13:291-299.

7. Kar S, Doshi SK, Sadhu A, et al. Primary Outcome Evaluation of a Next-Generation Left Atrial Appendage Closure Device. Circulation. 2021;143:1754-1762.

8. Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Kramer A, Andersen A, Kim WY, Korsholm K. First-in-human left atrial appendage closure using the WATCHMAN FLX Pro device:a case report. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2024;8:ytae135.

9. Bavishi C. Transcatheter Left Atrial Appendage Closure:Devices Available, Pitfalls, Advantages, and Future Directions. US Cardiol Rev. 2023;17:e05.

10. Lakkireddy D, Thaler D, Ellis CR, et al. Amplatzer Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Versus WATCHMAN Device for Stroke Prophylaxis (Amulet IDE):A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Circulation. 2021;144:1543-1552.

11. Lakkireddy D, Ellis CR, Thaler D, et al. 5-Year Results From the AMPLATZER Amulet Left Atrial Appendage Occluder Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025;85:1141-1153.

12. Kleinecke C, Cheikh-Ibrahim M, Schnupp S, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of Amplatzer cardiac plug versus Amulet occluders for left atrial appendage closure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96:E324-E331.

13. Bangash AB, Li Y, Huang W, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion using the LAmbre device in atrial fibrillation patients with a history of ischemic stroke:1-Year outcomes from a multicenter study in China. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2023;46:1478-1483.

14. Galea R, De Marco F, Meneveau N, et al. Amulet or WATCHMAN Device for Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure:Primary Results of the SWISS-APERO Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2022;145:724-738.

15. Ali M, Rigopoulos AG, Mammadov M, et al. Systematic review on left atrial appendage closure with the LAmbre device in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:78.

16. Vij V, Ruf TF, Thambo JB, et al. Contrast-free left atrial appendage occlusion in patients using the LAMBRE™ device. Int J Cardiol. 2024;405:131939.

17. Llagostera-Martín M, Cubero-Gallego H, Mas-Stachurska A, et al. Left Atrial Appendage Closure with a New Occluder Device:Efficacy, Safety and Mid-Term Performance. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1421.

18. Cruz-González I, Freixa X, Fernández-Díaz JA, Moreno-Samos JC, Martín-Yuste V, Goicolea J. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion With the LAmbre Device:Initial Experience. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2018;71:755-756.

19. ChamiéF, Guerios E, Silva DP, Fuks V, Torres R. Oclusão do Apêndice Atrial Esquerdo com a Prótese Lambre:Experiência Multicêntrica Inicial no Brasil. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2022;119:48-56.

20. Holmes DR, Korsholm K, Rodés-Cabau J, Saw J, Berti S, Alkhouli MA. Left atrial appendage occlusion. EuroIntervention. 2023;18:e1038-e1065.

21. Garg J, Kabra R, Gopinathannair R, et al. State of the Art in Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2025;11:602-641.

22. Bhagat A, Gier C, Kim P, Diggs P, Gursoy E. Delayed embolization of next-generation left atrial appendage closure device in an asymptomatic patient. Hear Case Rep. 2023;9:598-601.

23. Friedman DJ, Freeman JV, Zimmerman S, et al. WATCHMAN device migration and embolization:A report from the NCDR LAAO Registry. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:1192-1195.

24. Korsholm K, Kramer A, Andersen A, et al. Left atrial appendage sealing performance of the Amplatzer Amulet and WATCHMAN FLX device. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2023;66:391-401.

25. Rocca DGD, Magnocavallo M, Gianni C, et al. Procedural and short-term follow-up outcomes of Amplatzer Amulet occluder versus WATCHMAN FLX device:A meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2022;19:1017-1018.

26. Kapadia SR, Yeh RW, Price MJ, et al. Outcomes With the WATCHMAN FLX in Everyday Clinical Practice From the NCDR Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:e013750.

27. Li S, Zhang J, Zhang J, et al. GW29-e1803 LAmbre Occluder in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation:a Prospective single-center registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(16, Suppl):C150.

28. Park JW, Sievert H, Kleinecke C, et al. Left atrial appendage occlusion with lambre in atrial fibrillation:Initial European experience. Int J Cardiol. 2018;265:97-102.

29. Huang H, Liu Y, Xu Y, et al. Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure With the LAmbre Device for Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation:A Prospective, Multicenter Clinical Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:2188-2194.

30. Wang B, Wang Z, He B, et al. Percutaneous Left Atrial Appendage Closure Confirmed by Intra-Procedural Transesophageal Echocardiography under Local Anesthesia:Safety and Clinical Efficacy. Acta Cardiol Sin. 2021;37:146-154.

31. Chen YH, Wang LG, Zhou XD, et al. Outcome and safety of intracardiac echocardiography guided left atrial appendage closure within zero-fluoroscopy atrial fibrillation ablation procedures. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2022;33:667-676.

32. Saw J, Holmes DR, Cavalcante JL, et al. SCAI/HRS expert consensus statement on transcatheter left atrial appendage closure. Heart Rhythm. 2023;20:e1-e16.

33. Murtaza G, Turagam MK, Dar T, et al. Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Device Embolization (The LAAODE Study):Understanding the Timing and Clinical Consequences from a Worldwide Experience. J Atr Fibrillation. 2021;13:2516.

34. Aminian A, Lalmand J, Tzikas A, Budts W, Benit E, Kefer J. Embolization of left atrial appendage closure devices:A systematic review of cases reported with the watchman device and the amplatzer cardiac plug. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:128-135.

35. Salmon MK, Hammer KE, Nygaard JV, Korsholm K, Johansen P, Nielsen-Kudsk JE. Left atrial appendage occlusion with the Amulet device:to tug or not to tug?J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021;61:199-206.

36. Alkhouli M, Sievert H, Rihal CS. Device Embolization in Structural Heart Interventions:Incidence, Outcomes, and Retrieval Techniques. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:113-126.

37. European Device Guide. Cardiac Interventions Today. Available at: https://citoday.com/device-guide/european. Accessed 2 Jul 2025.

38. Fahmy P, Eng L, Saw J. Retrieval of embolized left atrial appendage devices. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;91:E75-E80.

39. Abbadi AB, Akodad M, Horvilleur J, Neylon A. Retrieval of a left appendage device from the left ventricle using a large bore steerable catheter. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;104:365-367.

40. Hermann D, Khan Z, Khan Z, Abreu J, Loyalka P, Qureshi AM. First-in-Human Percutaneous Removal of Left Atrial Appendage Occlusion Devices With a Novel Retrieval System. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2024;10:1004-1009.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: (M.Á. Martín-Arena).

@martinarenaMA;

@hemodin90;

@Azlaragarcia;

@JuradoRomanAl;

@Dr_DanielTebar;

@BorjaRiversa;

@JonZubiaur;

@MattiaBasile97;

@cayevalbuena;

@LuciaFGasso;

@reginadalmau;

@RaulmorenoMD