ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: To evaluate the impact of bleeding on the risk-benefit balance of coronary revascularization prior to transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TF-TAVI).

Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of the patients who underwent TF-TAVI at our center between 2008 and 2018 to evalute the management of coronary artery disease (percutaneous revascularization vs no revascularization). Subsequently, the rate of major bleeding —defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria (type 3-5)— and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) was compared between the 2 groups over a mean 60-month follow-up period.

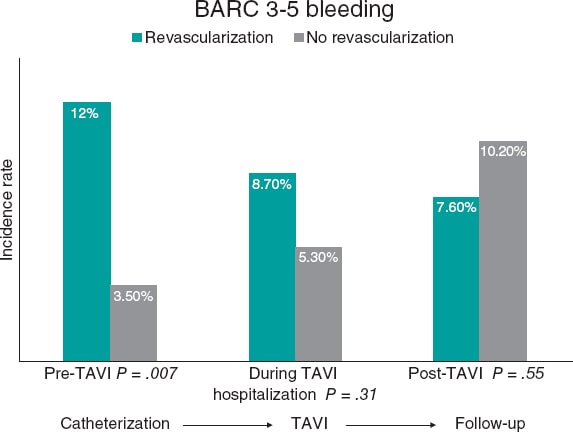

Results: A total of 379 patients were included. The overall rate of major bleeding was 21.4%, higher in revascularized patients but without reaching statistical significance. The rate of major bleeding between coronary angiography and TF-TAVI implantation was 5.5% and significantly higher in revascularized patients (12.0% vs 3.5%; P = .07). During the hospitalization for TF-TAVI and throughout follow-up, the rate of major bleeding was 6.1% and 9.6%, respectively, with no significant inter-group differences. There were no significant differences either in the 5-year rate of MACE.

Conclusions: In our patient cohort, pre-TF-TAVI preoperative coronary revascularization was associated with an initially higher bleeding risk; however, no statistically significant differences were observed in major bleeding or MACE at the 5-year follow-up. These findings support the need to generate high-quality clinical evidence to demonstrate the net clinical benefit of coronary revascularization in this context.

Keywords: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Coronary revascularization. Bleeding.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Valorar el impacto del sangrado en la relación riesgo-beneficio de la revascularización coronaria previa al implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica por vía transfemoral (TAVI-TF).

Métodos: Se realizó un análisis retrospectivo de los pacientes tratados con TAVI-TF en nuestro centro entre los años 2008 y 2018, y se identificó la actuación sobre su enfermedad coronaria (revascularización percutánea frente a no revascularización). Posteriormente, se comparó entre ambos grupos la incidencia de sangrado mayor, definido por los criterios del Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) (tipos 3-5), y de eventos cardiovasculares adversos mayores (MACE) isquémicos durante un seguimiento medio de 60 meses.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 379 pacientes. La incidencia total de sangrado mayor fue del 21,4%, más alta en los pacientes con revascularización, pero sin alcanzar la significación estadística. La incidencia global de sangrado mayor entre la coronariografía diagnóstica y el TAVI fue del 5,5%, y resultó significativamente más alta en los pacientes revascularizados (12,0% frente a 3,5%; p = 0,07). Durante el ingreso para el TAVI-TF y el seguimiento posterior de 60 meses, la incidencia global de sangrado mayor fue del 6,1% y del 9,6%, respectivamente, sin diferencias significativas entre ambos grupos. Tampoco hubo diferencias en la incidencia de MACE a los 5 años de seguimiento.

Conclusiones: En nuestra cohorte de pacientes, la revascularización coronaria previa al TAVI-TF conlleva un aumento inicial del riesgo de sangrado, sin diferencias estadísticamente significativas en sangrado mayor ni en MACE en el seguimiento a 5 años. Estos hallazgos apoyan la necesidad de generar una evidencia clínica de calidad que demuestre un beneficio clínico neto de la revascularización en este contexto.

Palabras clave: Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Revascularización coronaria. Sangrados.

Abreviaturas

MACE: major adverse cardiovascular events. TF-TAVI: transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Currently, transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TF-TAVI) is the treatment of choice for most patients with severe aortic stenosis, particularly those with high surgical risk or advanced age.1 Several clinical trials have demonstrated comparable clinical outcomes between TF-TAVI and surgical aortic valve replacement.2-4 Major and minor bleeding remain one of the most frequent procedural complications and are associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates.5 Although, in recent years, improvements in materials (reduction in caliber required for valve implantation) and increasing operator experience have substantially reduced perioperative bleeding rates, such rates remain significantly high. One of the main risk factors for bleeding is the requirement for perioperative dual antiplatelet therapy,6 most widely necessary when coronary revascularization is performed along with TAVI.

In addition, the high prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients undergoing TF-TAVI, reported in up to 80% of cases in published series, along with current clinical practice guideline recommendations to revascularize all ≥ 70% proximal coronary stenoses, results in a high rate of revascularization.1

Our group recently published data showing that systematic, complete revascularization in patients undergoing TF-TAVI does not provide prognostic benefit in terms of mortality or major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) (a composite of death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure-related hospitalization.)7 Given the high rate of bleeding events in these patients, it is of substantial clinical interest to evaluate whether revascularization may confer an increased bleeding risk and assess its clinical impact.6

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective study based on the historical cohort of patients who underwent TF-TAVI at our center from 2008 through 2018. Study information was drawn from the local database (Géminis) and supplemented by electronic health record review to document follow-up events. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of A Coruña-Ferrol (Spain). The primary endpoint of the study was to compare the rate of major bleeding—defined according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium (BARC) criteria (types 3–5)—occurring after diagnostic coronary angiography, during the index hospitalization for TAVI, and during follow-up. Additional endpoints included the rate of MACE and the composite endpoint of MACE plus major bleeding over the same period of time, comparing patients who underwent percutaneous coronary revascularization with those managed conservatively.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and qualitative variables as proportions. We used the Student t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) with first-order polynomial contrast for continuous variables. For categorical variables, we used the chi-square test for linear trend or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

We conducted survival analyses using the Cox proportional hazards model to determine whether an association existed between coronary revascularization and patient prognosis in terms of mortality, MACE, major bleeding (BARC 3–5), and a composite of MACE and major bleeding. Results were expressed as age- and sex-adjusted survival curves.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 26.0 (IBM, USA) and R version 4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria). Statistical significance was set at P < .05 for all comparisons.

RESULTS

A total of 379 patients who underwent TF-TAVI between 2008 and 2018 were included. Four patients were lost to follow-up, leaving 375 patients for the statistical analysis. Table 1 illustrates the patients’ baseline characteristics, with a mean age of 83.1 years and predominance of the female sex and intermediate surgical risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons score, 4.3%). Although most baseline characteristics were well balanced between patients with and without revascularization, the latter had a slightly higher surgical risk (4.5% vs 3.5%) and a higher proportion of women (61.3% vs 47.8%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the patients

| Variable | Nonrevascularized | Revascularized | Total | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 84 (5.5) | 82 (6.7) | 83.1 (5.9) | .015 |

| Female sex | 176 (61.3%) | 44 (47.8%) | 220 (58.0%) | .022 |

| Diabetes | 83 (28.9%) | 36 (39.1%) | 119 (31.4%) | .066 |

| Hypertension | 219 (76.3%) | 73 (79.3%) | 292 (77.0%) | .546 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 165 (57.5%) | 65 (70.7%) | 230 (60.6%) | .025 |

| Body mass index | 29.6 (5.2) | 28.3 (5.5) | 29.3 (5.3) | .032 |

| Baseline hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 12.1 (1.6) | 11.8 (1.8) | 12.1 (1.7) | .160 |

| Creatinine clearance (mL/min) | 55.7 (20.9) | 53.6 (21.4) | 55.2 (21.0) | .420 |

| STS score | 4.5% (2.5) | 3.5% (3.8) | 4.3% (2.9) | .002 |

| EuroSCORE I | 13.3% (7.8) | 8.6% (5.2) | 12.2% (7.5) | .001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 4.4% (3.4) | 2.6% (1.9) | 4.0% (3.2) | .001 |

| Baseline LVEF | 59.7% (13.2) | 56.9% (13.5) | 59.0% (13.3) | .083 |

| Baseline Max PG (mmHg) | 80.6 (25.0) | 79.1 (22.2) | 80.3 (24.4) | .602 |

| Baseline Mean PG (mmHg) | 47.1 (15.4) | 47.2 (14.0) | 47.1 (15.0) | .952 |

| Baseline aortic regurgitation | .384 | |||

| Grade 0 | 69 (24.2%) | 23 (25.6%) | 92 (24.3%) | |

| Grade 1 | 151 (53.0%) | 54 (60.0%) | 205 (54.0%) | |

| Grade 2 | 46 (16.1%) | 11 (12.2%) | 57 (15.0%) | |

| Grade 3 | 15 (5.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 16 (4.2%) | |

| Grade 4 | 4 (1.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 5 (1.3%) | |

| Angina symptoms | 45 (15.7%) | 23 (25.0%) | 68 (17.9%) | .043 |

| NYHA class | .278 | |||

| 0 | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (1.1%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| 1 | 41 (14.3%) | 19 (20.7%) | 60 (15.8%) | |

| 3 | 221 (77.0%) | 62 (67.4%) | 283 (74.7%) | |

| 4 | 24 (8.4%) | 10 (10.9%) | 34 (8.9%) | |

| Prior AMI | 32 (11.3%) | 21 (23.1%) | 53 (14.0%) | .005 |

| Prior CABG | 18 (6.3%) | 6 (6.6%) | 24 (6.3%) | .931 |

| Prior PCI | 24 (8.5%) | 75 (82.4%) | 99 (26.1%) | .001 |

| Stroke | 26 (9.2%) | 8 (8.9%) | 34 (9.0%) | .932 |

| Liver disease | 8 (2.8%) | 1 (1.1%) | 9 (2.4%) | .351 |

| COPD | 39 (13.7%) | 7 (7.7%) | 46 (12.1%) | .126 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 9 (3.1%) | 5 (5.4%) | 14 (3.7%) | .309 |

| VKA therapy | 83 (29.2%) | 21 (23.1%) | 104 (27.4%) | .254 |

| DOAC therapy | 11 (3.9%) | 3 (3.3%) | 14 (3.7%) | .801 |

|

AMI, myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulants; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; Max PG, maximum pressure gradient; Mean PG, mean pressure gradient; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; VKA, vitamin K antagonist. |

||||

Regarding symptoms, most patients were in New York Heart Association functional class III (74.7%). Among revascularized patients, 25.0% (23 patients) reported angina symptoms vs only 15.7% (41 patients) from the nonrevascularized group. Regarding anticoagulant therapy, 29.2% (83 patients) from the nonrevascularized group were on vitamin K antagonists and 3.9% (11 patients) on direct oral anticoagulants. These rates were slightly lower among revascularized patients, with 23.1% (21 patients) on vitamin K antagonists and 3.3% (3 patients) on direct oral anticoagulants (table 1).

Percutaneous revascularization and bleeding

Of the patients undergoing TF-TAVI, 92 (24.3%) underwent coronary revascularization, which in our center was always performed before valve replacement, with a median interval of 88 days (46–162) between revascularization and TAVI. Consequently, most revascularized patients were on dual antiplatelet therapy when they underwent TAVI. The decision to revascularize was made in a multidisciplinary meeting according to contemporary clinical practice guidelines (2008–2018). The prevailing strategy was to revascularize most coronary lesions, and the clinical criterion remained unchanged throughout the study period.

Clinical outcomes during follow-up are shown in table 2. There were no statistically significant differences in the time elapsed between diagnostic catheterization and TAVI between the 2 groups (median of 118 days for revascularized patients and 123 days for the nonrevascularized ones; P = .835). Figure 1 illustrates that the overall rate of major bleeding was 21.4% (81/375), with a rate of 28.3% (26/92) for revascularized patients and 19.0% (55/283) for the nonrevascularized ones, without reaching statistical significance (P = .074).

Table 2. Clinical outcomes during follow-up according to revascularization status

| Clinical outcome | Nonrevascularized n (%) | Revascularized n (%) | Total, n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major bleeding (BARC 3-5) | 55 (19.0%) | 26 (28.3%) | 81 (21.4%) | .074 |

| MACE at 60 months | 160 (55.7%) | 49 (53.2%) | 209 (55.1%) | .082 |

| Pre-TAVI MACE | 58 (20.4%) | 25 (27.2%) | 83 (22.1%) | NS |

| Mortality at 60 months | 125 (43.7%) | 36 (39.0%) | 161 (42.2%) | NS |

| AMI at 60 months | 8 (2.8%) | 10 (11.5%) | 18 (4.8%) | .001 |

| Revascularization at 60 months | 3 (1.0%) | 6 (6.5%) | 9 (2.4%) | .003 |

| Composite endpoint | 174 (60.6%) | 61 (66.3%) | 235 (62.0%) | .139 |

|

AMI, myocardial infarction; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; NS, not significant; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. |

||||

Figure 1. Central illustration. Overall rate of major bleeding across follow-up periods. BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Table S1 illustrates the bleeding events classified by BARC criteria according to revascularization status during follow-up. The overall rate of major bleeding (BARC 3–5) between coronary angiography and TF-TAVI was 5.5% (21/375) and was significantly higher among revascularized patients (12.0% vs 3.5%; P = .007). During the index hospitalization for TF-TAVI, the overall rate of major bleeding was 6.1% (23/375), with no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups (8.7% vs 5.3%; P = .31). During post-TAVI follow-up, the overall rate of major bleeding was 9.6% (36/375), with no significant differences between the groups either (7.6% vs 10.2%; P = .545) (figure 1).

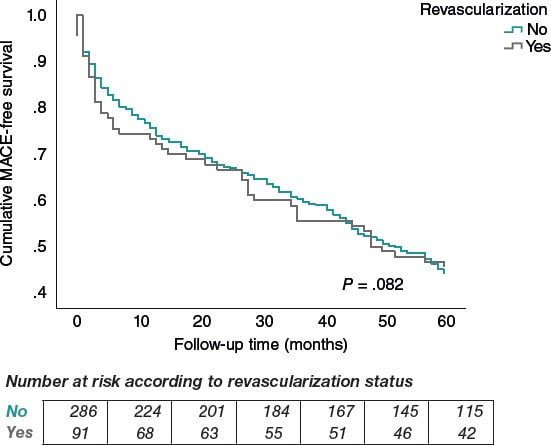

After a mean follow-up of 60 months, 55.1% (209/379) of patients experienced MACE: 55.7% in the nonrevascularized group (160 patients), and 53.2% in the revascularized group (49 patients). There were no statistically significant differences (P = .082) (figure 2). The overall mortality rate at 60 months was 42.2% (161/378): 43.7% in nonrevascularized patients (125 patients), and 39.0% in revascularized ones (36 patients). Again, no significant differences were reported (P = .380) (figure 3).

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier curve for MACE-free survival by revascularization status.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival by revascularization status.

The revascularized group exhibited higher rates of myocardial infarction (11.5% vs 2.8%; P = .001) and repeat revascularization (6.5% vs 1.0%; P = .003).

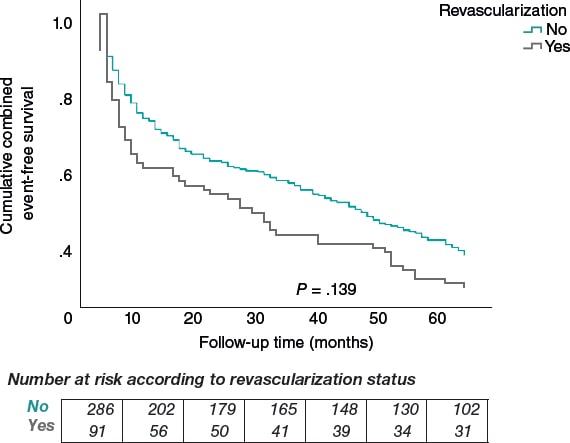

After a mean 60-month follow-up, the composite endpoint (MACE or major bleeding) occurred in 62.0% (235 patients) of the total sample, without significant differences across the groups (66.3% nonrevascularized vs 60.6% revascularized; P = .139) (figure 4).

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier curve for combined event–free survival (ischemic or hemorrhagic) by revascularization status.

DISCUSSION

There is currently no definitive clinical evidence on the optimal management of coronary artery disease in patients scheduled for TAVI. Clinical guidelines recommend percutaneous revascularization in all patients undergoing TF-TAVI with percent diameter stenoses ≥ 70% in the target vessel proximal segments, with a Class IIa recommendation. However, to this date, only 2 randomized clinical trials have assessed the benefit of pre-TAVI revascularization, with conflicting results.8,9

Major bleeding remains one of the most frequent and prognostically relevant complications after TF-TAVI. In fact, in the PARTNER 2 trial conducted with intermediate-risk patients, major bleeding was reported in up to 15.2% of patients 1 year after TAVI.³ Despite this, evidence on the impact of pre-TAVI coronary revascularization on bleeding risk is scarce.

In the ACTIVATION trial,8 a total of 235 patients scheduled for TF-TAVI who had significant coronary artery disease were randomized to undergo percutaneous revascularization (n = 119) or receive optimal medical therapy (n = 116). Outcomes in the 2 groups were evaluated according to a composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality and hospitalization. At 1 year, noninferiority of the strategy of adding percutaneous revascularization to TF-TAVI could not be demonstrated in patients who did not undergo revascularization; however, higher bleeding rates were observed in the intervention group.

The results of the NOTION-3 trial9 have been recently published. In this study, 452 patients scheduled to undergo TF-TAVI with significant coronary artery disease were randomized to receive either an invasive or a conservative strategy. In this case, the decision to revascularize was guided by the severity of stenosis as assessed by fractional flow reserve. Outcomes were evaluated according to a composite primary endpoint of all-cause mortality, myocardial infarction, and emergency revascularization. At 2 years, patients who had been revascularized showed a significant reduction in the risk of MACE compared with the conservative strategy (26.0% vs 36.0%), driven primarily by a higher rate of unplanned revascularization and without an effect on mortality. However, this risk reduction was accompanied by a higher rate of bleeding events (28.0% vs 20.0%). A major limitation of this trial is its open-label design and the fact that it did not exclude patients with angina, which may have contributed to the increased rate of unplanned revascularization.

In our study, there were no statistically significant differences in MACE or major bleeding at 60 months between revascularized and nonrevascularized patients. However, a higher rate of major bleeding occurred among the former during the time elapsed between diagnostic coronary angiography and TAVI, which is consistent with former studies demonstrating higher bleeding rates in patients on dual antiplatelet therapy.8,9 Furthermore, this group exhibited higher rates of myocardial infarction and subsequent revascularization. Although these findings were expected, they should be interpreted with caution because, despite statistically significant differences, the small number of events limits statistical power to draw definitive conclusions. A reasonable strategy may be selective revascularization aimed at symptom control, particularly in patients with angina.

Our study has several important limitations. The most significant one is that it is a single-center, observational, nonrandomized, retrospective analysis, which results in multiple sources of selection bias. First, a biological selection bias exists because the study includes patients who self-selected by surviving to a mean age of 83 years with sufficient biological status to be considered eligible for TF-TAVI. Second, a clinical selection bias is present regarding which patients were selected for TAVI, as the retrospective design makes it impossible to standardize the criteria originally used to determine candidacy. Finally, our cohort only includes patients in whom the procedure was ultimately performed—not those who initially underwent evaluation for TAVI—which means that some patients who underwent diagnostic cardiac catheterization (with or without revascularization) may not have proceeded to TAVI and are therefore not included. The proportion of such patients and the reasons for not completing the procedure are unknown. Although the causes may be diverse, given the procedural risks of coronary interventions and the frequent presence of complex coronary artery disease in this population, it is plausible that some candidates did not undergo TAVI because of revascularization-related complications; however, this cannot be demonstrated with our data and remains speculative. Moreover, this is a single-center study with a limited sample size, which may restrict the external validity of the findings and the statistical power to detect inter-group differences.

CONCLUSIONS

In our cohort, pre-TF-TAVI systematic coronary revascularization was associated with an increased early risk of major bleeding, specifically between diagnostic catheterization and valve implantation. There were no statistically significant differences in long-term major bleeding, MACE, or the composite endpoint between revascularized and nonrevascularized patients. These findings, together with recent evidence indicating that revascularization of stable coronary disease does not clearly improve prognosis,10 reinforce the need for high-quality clinical evidence to define the clinical impact of pre-TAVI systematic coronary revascularization.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of A Coruña-Ferrol. Informed consent was not required due to the retrospective design of the study and use of a preexisting clinical database. SAGER guidelines were followed to minimize potential sex-related bias.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence tools were used in the preparation of this article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

C. Vidau Getán contributed to data collection and manuscript drafting. D. López Vázquez was the main reviewer and contributed to refinement of statistical analysis. X. Flores Ríos conceived the study and conducted the initial statistical analysis. M. González Montes and G. González Barbeito participated in data collection. The remaining coauthors reviewed the final version of the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Clinical practice guidelines recommend percutaneous revascularization in TAVI candidates with percent diameter stenoses ≥ 70% in the target vessel proximal segments.

- No high-quality evidence demonstrates a clinical benefit of systematic pre-TAVI coronary revascularization.

- Two clinical trials have been conducted in this patient population, with inconsistent results regarding the benefits observed in terms of ischemic events, and with a higher rate of bleeding events in revascularized patients.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Revascularized patients showed higher rates of early major bleeding (between diagnostic catheterization and TAVI), without significant long-term differences in ischemic or hemorrhagic events.

- Results support the need for robust evidence to clarify the clinical impact of systematic pre-TAVI coronary revascularization.

REFERENCES

1. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

2. Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter versus Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in High-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med.2011;364:2187-2198.

3. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620.

4. Reardon MJ, Mieghem NMV, Popma JJ, et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1321-1331.

5. Moat N, Brecker S. Transfemoral TAVI is superior to SAVR in elderly high-risk patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis! Eur Heart J.2016;37:3513-3514.

6. Avvedimento M, Nuche J, Farjat-Pasos JI, Rodés-Cabau J. Bleeding Events After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:684-702.

7. Vázquez DJL, López GA, Guzmán MQ, et al. Prognostic impact of coronary lesions and its revascularization in a 5-year follow-up after the TAVI procedure. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;102:513-520.

8. Patterson T, Clayton T, Dodd M, et al. ACTIVATION (PercutAneous Coronary inTervention prIor to transcatheter aortic VAlve implantaTION):A Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:1965- 1974.

9. Lønborg J, Jabbari R, Sabbah M, et al. PCI in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N Engl J Med. 2024;391:2189-2200.

10. Maron DJ, Hochman JS, Reynolds HR, et al. ISCHEMIA Research Group. Initial Invasive or Conservative Strategy for Stable Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med.2020;382:1395-1407.