ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is traditionally performed with on-site cardiac surgery (CS) backup. However, procedural advances enabled TAVI to be performed safely without immediate CS backup. This study describes our single-center experience with TAVI performed in a center without on-site CS backup.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective analysis of the first 300 patients undergoing TAVI without on-site CS backup between 2020 and 2024. The primary endpoint was 30-day mortality. Secondary endpoints included procedural and in-hospital mortality, stroke, emergency cardiac surgery (ECS), vascular complications, major hemorrhage, and pacemaker implantation. Outcomes were compared with those from the Portuguese national TAVI registry.

Results: The cohort mean age was 82 ± 5 years (54% women). The median STS risk score was 3.8 [IQR, 2.3–6.6], with 17% high-risk patients (STS > 8). Most procedures were elective (83%). Transfemoral access was used in 99% of cases, and self-expandable valves were implanted in 95%. The 30-day mortality rate was 3.7% (n = 11), while stroke occurred in 2.7% (n = 8). The procedural survival rate was 99% (n = 298). No cases of ECS occurred (n = 0), coronary obstruction, TAVI-in-TAVI deployment as a bailout, or valve embolization were reported. Pericardial tamponade occurred in 0.7% of cases (n = 2). Major hemorrhage and vascular complications occurred in 8%, and pacemaker implantation in 20%. The 1-year mortality rate was 12%, with 4% attributed to cardiovascular causes; among survivors, and 91% reported symptomatic improvement. There were no significant differences in outcomes vs the results from the TAVI national registry.

Conclusions: TAVI was safely and effectively performed without on-site CS, including emergency and complex cases. The non-ECS rate and outcomes comparable to national benchmarks support the feasibility of TAVI in selected non-CS centers. In this context, expanding TAVI access may reduce waiting times and improve the management of severe aortic stenosis while maintaining high procedural quality.

Keywords: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. TAVI. Severe aortic stenosis. Cardiac surgery backup.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) se realiza tradicionalmente con el apoyo de cirugía cardiaca mínimamente invasiva (CCMI) en el mismo centro. Sin embargo, los avances en los procedimientos han permitido realizar TAVI de forma segura sin cirugía cardiaca inmediata. Este estudio describe la experiencia de nuestro centro en el TAVI sin CCMI.

Métodos: Análisis retrospectivo de los primeros 300 pacientes a quienes se realizó TAVI sin CCMI entre 2020 y 2024. El objetivo principal fue la mortalidad a los 30 días. Los objetivos secundarios fueron la mortalidad intraprocedimiento y la mortalidad hospitalaria, el accidente cerebrovascular, la cirugía cardiaca de urgencia (CCU), las complicaciones vasculares, la hemorragia grave y el implante de marcapasos. Los resultados se compararon con el registro nacional portugués de TAVI.

Resultados: La edad media de la cohorte fue de 82 ± 5 años y el 54% eran mujeres. La mediana de la puntuación de riesgo STS fue de 3,8 [IQR: 2,3-6,6], con el 17% de pacientes de alto riesgo (STS > 8). La mayoría de las intervenciones fueron electivas (83%). Se utilizó el acceso transfemoral en el 99% de los casos y se implantaron válvulas autoexpandibles en el 95% de ellos. La tasa de mortalidad a los 30 días fue del 3,7 % (n = 11). Se produjeron accidentes cerebrovasculares en el 2,7% (n = 8). La tasa de supervivencia al procedimiento fue del 99% (n = 298). No se precisó CCU en ningún paciente y no hubo casos de obstrucción coronaria, necesidad de TAVI en TAVI como medida de rescate ni embolización valvular. Dos pacientes presentaron taponamiento pericárdico (0,7%). Se produjeron hemorragias graves y complicaciones vasculares en el 8% de los pacientes, y se implantó marcapasos en el 20%. Al año, la tasa de mortalidad fue del 12%, el 4% por causas cardiovasculares. El 91% de los supervivientes presentaron una mejora de los síntomas. No hubo diferencias significativas en los resultados en comparación con los del registro nacional de TAVI.

Conclusiones: El TAVI se realizó de forma segura y eficaz sin CCMI, incluso en casos urgentes y complejos. La no necesidad de CCU y los resultados comparables a los referentes nacionales respaldan la viabilidad del TAVI en centros seleccionados sin cirugía cardiaca. Ampliar el acceso al TAVI en este contexto puede reducir los tiempos de espera y mejorar la atención de la estenosis aórtica grave, al tiempo que se mantiene una alta calidad del procedimiento.

Palabras clave: Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. TAVI. Estenosis aórtica grave. Cirugía cardiaca mínimamente invasiva.

Abbreviations

AS: aortic stenosis. CS: cardiac surgery. ECS: emergency cardiac surgery. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common primary valvular heart disease requiring intervention.1 Its prevalence is estimated at 3–5% in individuals older than 75 years,2,3 and it is expected to increase due to longer life expectancy, growing awareness, and improved diagnostic accuracy.4 The mortality rate of untreated severe symptomatic AS reaches 10-20% within the first year and 45% at 4 years.2,5

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a well-established, less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement for patients with severe symptomatic AS.1,6 Initially reserved for high-risk patients, TAVI indications have expanded to intermediate-risk and older lower-risk patients.1,6 Improvements in device technology, procedural techniques, and operator expertise have led to fewer complications and enhanced overall safety.3 The increasing prevalence of AS and the expansion of TAVI indications highlight the need to increase procedural capacity to meet current and future clinical demands and ensure timely access to treatment.7

Current clinical practice guidelines recommend that TAVI must be performed exclusively at centers with on-site cardiac surgery (CS) backup,1,6 as surgical backup provides a safety net in complications requiring emergency cardiac surgery (ECS).8 Nonetheless, the rate of ECS has significantly decreased to 0.5-1% of TAVI,9 and the outcomes of ECS remain poor,9 with a 54% survival rate at the index event and only 22% at 1 year,10 raising concerns about the actual benefits of mandatory surgical backup.

TAVI availability remains variable, with regional disparities due to the centralized distribution of CS centers.4,11 As a result, access is often limited in regions without tertiary CS centers, leading to prolonged waiting periods associated with a worse prognosis.3 TAVI waiting list mortality rate reaches 18%, highlighting the need for timely intervention.12 Expanding TAVI to centers without on-site CS will improve access, increase procedures, reduce health care inequalities, and alleviate surgical centers, allowing them to focus on higher-risk procedures.3,13 The limited number of eligible centers constrains the national procedural volume, preventing the health system’s ability to meet the population’s growing TAVI needs.4,14

This study aims to describe our experience with TAVI in a center without on-site CS and compare outcomes to the national benchmark of centers with surgical backup.

METHODS

Study population

We conducted a retrospective, single-center cohort study including the first 300 consecutive patients who underwent TAVI at our center, Hospital Espírito Santo de Évora (Portugal), between 2020 and 2024. This study was conducted in a hospital without an on-site CS department. Patients were identified through the institutional structural heart procedure registry. The study was approved by the center ethics committee, informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data collection

Clinical, echocardiographic, laboratory, and procedural data were obtained from electronic health records, including imaging modalities, procedural documentation, and discharge summaries. Baseline characteristics included demographic, clinical, and echocardiographic parameters, and procedural information such as access route and valve type.

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the 30-day all-cause mortality rate. The secondary endpoints were need for ECS, in-hospital mortality, stroke, 1-year all-cause mortality rate, 1-year cardiac death, vascular complications, major hemorrhage, and permanent pacemaker implantation. Outcomes were defined according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-3 (VARC-3) criteria.15 ECS was defined as any unplanned cardiac surgical conversion to open surgery required to manage a life-threatening complication occurring during or shortly after the procedure, performed before the patient leaves the procedural environment.

In addition, outcomes were compared with the most recent Portuguese national TAVI registry,16 which exclusively includes centers with on-site CS, to provide a benchmark for procedural safety and efficacy profile.

Follow-up

Follow-up was performed through clinic visits at 3 and 12 months, complemented by telephone contact and review of electronic health records when in-person visits were not possible. Symptomatic improvement was evaluated based on changes in New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared using the Student t test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance was set at a 2-tailed P-value < .05. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 18.0 (StataCorp, United States).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

The first consecutive 300 patients undergoing TAVI between 2020 and 2024 were included. The cohort mean age was 82 ± 5 years (62–101), and 54% (n = 161) were women. The median Society of Thoracic Surgery (STS) risk score was 3.8 [IQR, 2.3–6.6], with 17% (n = 51) classified as high-risk (STS > 8). Prior hospitalization for symptomatic AS occurred in 21% (n = 64). Seven patients (2%) had undergone previous surgical aortic valve replacement and were treated with the valve-in-valve procedure. Low-flow low-gradient severe AS was observed in 10% (n = 31) and bicuspid aortic valve in 6% (n = 18). The baseline characteristics of the included patients are summarized in table 1 and table 2. The Portuguese National TAVI registry included 2346 patients. Compared with our cohort, the national registry included more patients with NYHA FC > II (68% vs 51%; P < .01) and COPD (22% vs 12%; P < .01), whereas our center had a higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease (50% vs 38%; P < .01). The baseline characteristics of the Portuguese National TAVI Registry and a comparison with our cohort are shown in table 3.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and comorbidities

| Baseline characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 82 ± 5 [62-101] |

| Female sex, % (n) | 54 (161) |

| STS score, % | 3.75; IQR [2.29-6.55] |

| Low risk (STS < 4), % (n) | 52 (156) |

| Intermediate risk (STS 4-8) %, (n) | 31 (93) |

| High risk (STS > 8) % (n) | 17 (51) |

| EuroSCORE, % | 2.23 IQR [2.29-6.55] |

| Prior hospitalization due to AS, % (n) | 21 (64) |

| Hypertension, % (n) | 86 (258) |

| Diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 35 (104) |

| Dyslipidemia, % (n) | 71 (214) |

| eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73m² | 50 (50) |

| AF/flutter, % (n) | 22 (65) |

| Pacemaker, % (n) | 15 (46) |

| CAD, % (n) | 21 (63) |

| Transthoracic echocardiogram | |

| Mean transaortic gradient (mmHg) | 48 ± 14 |

| Peak transaortic velocity (m/s) | 4.3 ± 0.7 |

| AVA (cm2) | 0.74 ± 0.2 |

| LVEF (%) | 57 ± 12 |

| LVEF < 40%, % (n) | 12 (36) |

| LF/LG AS, % (n) | 10 (31) |

| SPAP (mmHg) | 38 ± 14 |

| Significant aortic regurgitation, % (n)* | 24 (71) |

| Significant mitral regurgitation, % (n)* | 27 (83) |

| CCTA | |

| Aortic annulus perimeter, mm | 74 ± 9 |

| Aortic annulus area, cm2 | 4.3 ± 0.9 |

| Aortic annulus diameter derived from perimeter, mm | 23.3 ± 3.3 |

| Aortic valve calcium score, UA | 2912 ± 1572 |

| Femoral artery min diameter, mm | 7.1 ± 1.3 |

| Bicuspid aortic valve, % (n) | 6 (18) |

|

Data is expressed as number (n) and standard deviation [ST]. Baseline characteristics, prevalence, and comorbidities, including transthoracic echocardiography and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) findings from the total population. AF, atrial fibrillation; AS, aortic stenosis; AVA, aortic valve area; CAD, coronary artery disease; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; LF/LG, low-flow low-gradient; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; SPAP, systolic pulmonary arterial pressure; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. * Significant valvular heart disease was defined as > grade 2. |

|

Table 2. Baseline characteristics comparison between our cohort and the Portuguese TAVI registry

| Baseline characteristics | Our center (n = 300) | National registry (n = 2346) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 82 ± 5 | 81 ± 7 | .6 |

| Female sex, % | 54 | 53 | .8 |

| STS risk score, % [IQR] | 3.8 [2.3-6.6] | 4.7 [3.0-7.1] | .7 |

| EuroSCORE II risk, % | 2.3 [1.6-4.0] | 4.3 [2.5-7.1] | .3 |

| NYHA class > 2, % | 51 | 68 | < .01 |

| DM, % | 35 | 33 | .5 |

| COPD, % | 12 | 22 | < .01 |

| GRF < 60 mL/kg/m2, % | 50 | 38 | < .01 |

| AF, % | 22 | 25 | .3 |

| PCI, % | 14 | 23 | < .01 |

| Stroke, % | 8 | 12 | .06 |

| TTE | |||

| Mean gradient (mmHg) | 48 ± 14 | 49 ± 16 | .8 |

| AVA (cm2) | 0.72 ± 0.20 | 0.64 ± 0.20 | .7 |

| LVEF < 50, % | 21 | 28 | .08 |

|

Baseline characteristics comparison between our cohort and the National TAVI registry.16 AF, atrial fibrillation; AVA, aortic valve area; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; IQR, interquartile range; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography. |

|||

Table 3. Clinical context and procedural characteristics

| Clinical context | Values |

|---|---|

| Elective procedure, % (n) | 83 (248) |

| Admitted prior to procedure, % (n) | 17 (52) |

| Days until TAVI (if admitted), (days) | 12 ± 8 |

| Cardiogenic shock, % (n) | 5 (15) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation, % (n) | 1.7 (5) |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation, % (n) | 2.7 (8) |

| Significant coronary artery disease, % (n) | 11 (33) |

| Pre-TAVI PCI, % (n) | 7 (21) |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.05 [0.86-1.41] |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 ± 1.9 |

| NT-proBNP (pg/mL) | 1865 [292-4250] |

| Evaluation time (days) | 15 [3-54] |

| Waiting time (days) | 59 [22-122] |

| Patient origin | |

| Our hospital area, % (n) | 62 (185) |

| Our area of influence, % (n) | 17 (53) |

| Outside our area of influence, % (n) | 21 (63) |

| Procedural characteristics | |

| Femoral access, % (n) | 99 (299) |

| Secondary access | |

| Radial, % (n) | 10 (29) |

| Femoral, % (n) | 90 (271) |

| Pre-dilation, % (n) | 58 (175) |

| Valve type | |

| Self-expandable valves, % (n) | 95 (286) |

| Evolut, % (n) | 91 (260/286) |

| Acurate, % (n) | 2 (6/286) |

| Navitor, % (n) | 7 (20/286) |

| Balloon-expandable valves, % (n) | 5 (14) |

| Myval, % (n) | 100 (14/14) |

| Valve size (mm) | 27.5 ± 3.0 |

| Post-dilation, % (n) | 38 (113) |

| Fluoroscopy time (min) | 26 [21-33] |

| Contrast volume (mL) | 216 [173-263] |

|

Clinical context characteristics of the population and procedural characteristics. Data is expressed as percentage and number (n) unless otherwise indicated. LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. |

|

Procedural characteristics

Most of our procedures were elective (83%; n = 249), while 17% (n = 51) were performed urgently following unplanned hospital admission for symptomatic severe AS. Cardiogenic shock was found in 5% (n = 15), and 4% (n = 12) required ventilatory support (table 3). Transfemoral access was used in 99% of cases (n = 298); the remaining 2 were performed via transcarotid and through an aortofemoral bypass graft route, both with surgical exposure by the vascular surgery team. Self-expandable valves were used in 95% of cases (n = 286), predominantly the Evolut family (Medtronic, United States) in 91%, n = 259, followed by Navitor (Abbott, United States) in 7% (n = 20) and Acurate (Boston Scientific, United States) in 2% (n = 6). The balloon-expandable valve Myval (Meril, India) was used in 5% (n = 14) (table 4).

Table 4. Procedural and follow-up outcomes

| Procedural outcomes | Values |

|---|---|

| Procedural death, % (n) | 0.7 (2) |

| In hospital death, % (n) | 2 (6) |

| Stroke, % (n) | 2.7 (8) |

| Emergency cardiac surgery, % (n) | 0 (0) |

| Major bleeding, % (n) | 8 (25) |

| Vascular complication, % (n) | 8 (24) |

| Acute kidney injury, % (n) | 6 (18) |

| Tamponade, % (n) | 0.7 (2) |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 2 [2-3] |

| Length of stay (days) | 3 [2-6] |

| In elective patients (days) | 3 [2-5] |

| Follow-up outcomes | |

| 1 month | |

| 30-day mortality, % (n) | 3.7 (11) |

| Permanent pacemaker implantation, % (n) | 20 (61) |

| 1 year | |

| 1-year mortality, % (n) | 12.4 (27/217) |

| Cardiac death, % (n) | 4 (8/203) |

| Hospital readmission, % (n) | 17 (51/300) |

| Symptomatic improvement, % (n) | 91 (246/269) |

|

Procedural and follow-up outcomes by VARC-3 Criteria.15 Data with %, (n) are expressed as percentages and number. The variables with (days) are expressed as number of days and IQR. Major bleeding is defined as VARC-3 type 2-3: overt bleeding requiring medical intervention, hospitalization, or transfusion ≥ 1 unit of blood. Emergency cardiac surgery is any unplanned cardiac surgery needed to manage life-threatening complications during or shortly after the procedure, performed before the patient leaves the procedural setting. Vascular complications are arterial or venous injury, dissection, stenosis, ischemia, thrombosis, pseudoaneurysm, hematoma, distal embolization, or closure device failure related to access sites requiring intervention or resulting in clinical sequelae. Acute kidney injury is defined according to KDIGO criteria as an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or ≥ 1.5 times baseline within 7 days. |

|

Procedural and 1-month outcomes

The primary endpoint, 30-day mortality rate, was 3.7% (n = 11), while in-hospital mortality was 2% (n = 6). Survival at the end of the procedure was achieved in 99% of patients (n = 298). No patient required ECS. Two patients (0.7%) underwent transcathether pericardiocentesis for cardiac tamponade, one due to a self-contained left ventricular guidewire perforation that did not require ECS, and the other of undetermined cause, which persisted and ultimately required delayed exploratory cardiac surgery, resulting in postoperative death. No cases of aortic valvular annulus rupture, coronary obstruction, TAVI-in-TAVI deployment, or valve embolization occurred. Stroke occurred in 2.7% (n = 8), 1.6% of which (n = 5) were disabling, while major bleeding and vascular complications were each observed in 8%. Pacemaker implantation was required in 20% (n = 61) (table 4). A detailed description of procedural and early causes of death is shown in table S1.

Follow-up outcomes

The 1-year all-cause mortality rate was 12% (n = 36), and cardiac death, 4% (n = 12). A detailed description of the causes of death is provided in table S1. Readmission occurred in 17% (n = 51), including 32 cardiovascular and 19 non-cardiovascular events. A detailed description of the causes of readmission is provided in table S1. Among surviving patients with available data, 91% reported symptomatic improvement, assessed by the NYHA functional class (table 4).

National TAVI registry comparison

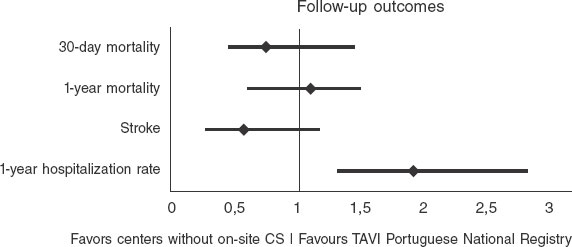

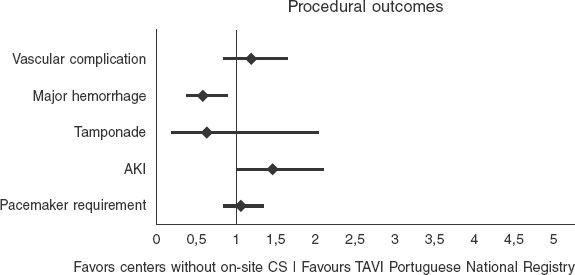

Compared with the Portuguese TAVI national registry results available16 (table 5), our center demonstrated a non-statistically significant lower 30-day mortality rate (3.7% vs 4.8%; OR, 0.8; 95%CI, 0.44–1.47; P = .5) and similar 1-year mortality rates (12% vs 11%; OR, 1.0; 95%CI, 0.76–1.47; P = .8) (figure 1). The rate of ECS was equivalent in both groups (0% vs 0.4%; P = .5), as were the rates of vascular complications (8% vs 6.8%; P = .4) and major bleeding (8.3% vs 13.3%; P = .2). Our stroke rate was numerically lower (2.7% vs 4.6%; P = .1), as was the rate of acute kidney injury (6% vs 4.2%; P = .5). Pacemaker implantation rates were similar (20% vs 19%; P = .7) (figure 2). However, 1-year hospitalization was more frequent in our cohort (17% vs 9.6%; P = .03).

Table 5. Outcomes comparison between our center and the national registry

| Outcome measure | Our center (n = 300) | National registry (n = 2346) | Odds ratio 95%CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30-day mortality, % (n) | 3.7 (11) | 4.8 (110/2297) | 0.8 [0.4-1.4] | .79 |

| 1-year mortality, % (n) | 12 (36) | 11 (194/1706) | 1.1 [0.6-1.5] | .86 |

| Tamponade, % (n) | 0.7 (2) | 1.0 (8/775) | 0.6 [0.2-2] | .73 |

| Coronary obstruction, % (n) | 0 (0) | 1.8 (14/772) | NE | .09 |

| Emergency cardiac surgery, % (n) | 0 (0) | 0.4 (4/954) | 0.8 [0.2-6.8] | .35 |

| TAVI-in-TAVI, % (n) | 0 (0) | 1.1 (8/725) | NE | .09 |

| Vascular complication, % (n) | 8 (24) | 7 (120/1766) | 1.2 [0.9-1.6] | .43 |

| Major hemorrhage, % (n) | 8 (25) | 13 (273/2054) | 0.6 [0.4-0.9] | .02 |

| Stroke, % (n) | 2.7 (8) | 4.6 (88/1893) | 0.6 [0.3-1.2] | .14 |

| AKI, % (n) | 6 (18) | 4.2 (79/1892) | 1.5 [0.9-2.1] | .46 |

| Pacemaker implantation, % (n) | 20 (60) | 19.0 (374/1964) | 1.1 [0.9-1.3] | .69 |

| Hospital readmission, % (n) | 17 (51) | 10 (98/1017) | 1.9 [1.3-2.8] | .03 |

|

Procedural and clinical outcomes comparison between our cohort and the TAVI National Registry.16 Data is expressed as percentages. Acute kidney injury (AKI) is defined according to KDIGO criteria as an increase in serum creatinine ≥ 0.3 mg/dL within 48 hours or ≥ 1.5 times baseline levels within 7 days. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; NE, not estimable; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. |

||||

Figure 1. Forest plot comparing the odds ratios (OR) of primary endpoints between our center without on-site cardiac surgery (CS) backup and the national Portuguese TAVI registry16 (all centers with on-site CS backup).

Figure 2. Forest plot of procedural outcomes comparing our center without on-site CS backup with the national Portuguese TAVI registry16 (centers with on-site CS backup).

DISCUSSION

This single-center study is the first national experience of TAVI in a non-on-site CS backup center. Our results suggest that this model is feasible and safe, with outcomes comparable to those reported by national and international series, including centers with surgical backup. Our outcomes were similar across key endpoints vs the National Portuguese TAVI registry,16 which includes only centers with surgical backup. Although no patients from our series required ECS, and 1 patient underwent delayed surgical intervention due to persistent pericardial effusion, the procedure was unsuccessful. This observation is consistent with other reports indicating that outcomes of emergency conversion after TAVI are generally poor, even in centers with surgical backup.8,10

TAVI safety and efficacy profile have improved significantly through careful procedural planning, the involvement of a multidisciplinary heart team (including cardiac surgery), and growing operator experience supported by technological advances. As a result, the need for immediate surgical backup has become increasingly less relevant. Although the complications that require surgical intervention remain rare, they are associated with high morbidity and mortality despite surgical management. Within this context, our results support the feasibility and suggest the non-inferiority of performing TAVI without on-site CS, reinforcing its applicability across various clinical scenarios, including younger individuals and those with multivalvular or coronary artery disease.

Our program reflects the contemporary TAVI landscape, including a heterogeneous and high-risk population with a significant proportion of emergency and unstable cases, including hospitalized patients and those in cardiogenic shock. In addition, we treated patients with complex anatomical and clinical characteristics such as valve-in-valve procedures, bicuspid aortic valves, reduced LVEF, and pulmonary hypertension. This all-comers profile mirrors the real-world spectrum that structured TAVI programs must address today, extending beyond elective transfemoral procedures for native AS.

Of note, our median waiting time for the procedure was short (59 days [IQR, 22-122]), and 20% of patients were referred from outside our direct hospital catchment area. This suggests that our center has become a regional reference for TAVI despite the lack of on-site CS, which reflects both the accessibility of our program and the trust placed in our heart team’s expertise. Importantly, many of these patients were referred because traditional TAVI centers could not meet procedural demand promptly, highlighting our role in addressing unmet clinical needs within the region.

Our findings align closely with results from countries where TAVI is performed without on-site CS, including Spain,11 Germany,17 and Austria.18 In Spain, the multicenter registry reported a conversion rate to open-heart surgery of 0.3% in centers without on-site CS backup.11 The German AQUA registry, which included more than 17 000 patients, found no significant differences in outcomes between centers with and without CS, with a 30-day mortality rate of 3.8% in hospitals with visiting CS vs 4.2% in those with CS backup, with emergency surgery rates of 0.3% and 0.7%, respectively17. Similarly, a study from Austria has shown favorable outcomes in centers without on-site surgery, with no significant differences in in-hospital mortality or surgical conversion rates.18 Our outcomes are consistent with these findings, with a 30-day mortality rate of 3.7% and no cases of ECS. Consistent with previous experiences from other countries, our results demonstrate equivalent and non-inferior results compared with centers that have on-site surgical backup.

Importantly, our study reflects a more recent era, with procedures performed in lower-risk patients, using the latest-generation devices, by more experienced operators, and following more precise preoperative planning with advanced CT imaging modalities. In addition, unlike earlier studies where visiting surgeons were present, our center performed all procedures without on-site surgical support, demonstrating the feasibility of a fully independent model. This study provides contemporary real-world evidence that TAVI can be safely and effectively performed in selected patients in centers without on-site CS backup, supporting broader access while maintaining quality standards.

Our study carries important policy implications. In the context of rising TAVI demand and resource constraints in high-volume surgical centers, decentralizing care to centers without on-site CS backup may enhance access without compromising patient outcomes. Our data supports the expansion of TAVI programs under carefully controlled conditions: standardized protocols, well-trained interventional teams, strong referral networks, and access to surgical support within a structured regional pathway. Regulatory agencies may consider revisiting existing requirements for on-site surgery, fostering a model where expertise guides the safe implementation of structural heart procedures while ensuring timely access to defined surgical centers for protocoled backup in case of delayed surgical needs.

These findings highlight the safety and viability of expanding TAVI programs to selected centers without surgical backup. With rigorous patient selection, experienced operators, and standardized procedural pathways, excellent outcomes can be achieved without immediate surgical support. Our experience supports a more inclusive structural heart care model that delivers timely and effective therapy to a broader patient population without compromising safety or efficacy.

Limitations

While these results are encouraging, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center, retrospective study, and although data collection was comprehensive, the potential for unmeasured confounding remains. Second, long-term follow-up beyond 1 year was unavailable, limiting conclusions on valve durability and late complications. Third, patient selection and procedural planning were guided by a highly experienced heart team, which may not be generalizable to all centers without surgical backup. Finally, although the baseline characteristics of our cohort and those of the Portuguese national registry (table 3) appear to be broadly comparable, result comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as no statistical adjustment was performed, the analysis was retrospective, and patients in the registry generally had a less favorable clinical profile.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrates that TAVI can be safely and effectively performed in centers without on-site CS backup, even in a heterogeneous, all-comers population. Outcomes appear broadly comparable and support the non-inferiority of this approach relative to centers with on-site CS. The risk of ECS was very low, and its incremental benefit may be limited, while CS centers remain few and frequently overburdened. These findings suggest that, with careful case planning and growing operator experience, expanding TAVI programs to selected non-CS centers is a safe and feasible strategy to address the growing demand and improve access for patients with severe AS. Randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm these results and guide broader implementation.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by Hospital Espírito Santo de Évora ethics committee, ULSAC. All procedures were performed in full compliance with the ethical standards of the center research committee and with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. This study was conducted in full compliance with the SAGER guidelines. Sex and gender considerations were addressed appropriately, and any potential sex- or gender-related differences were assessed and reported where relevant.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Rocha de Almeida: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, original draft writing and review and editing of the final draft. R. Fernandes, Â. Bento, D. Neves, D. Brás, G. Mendes were in charge of original draft writing and review and editing of the final draft. R. Rocha, M. Paralta Figueiredo and R. Viana were in charge of data curation, reviewed and edited the final draft. R. Louro and Á. Laranjeira Santos were in charge of review and editing of the final draft. L. Patrício was in charge of conceptualization, supervision, review and editing of the final draft and validation. All authors read and approved the final draft.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- TAVI programs are recommended to be established in centers with on-site CS, as some complications may require emergency surgery.

- However, the rate of post-TACI ECS is consistently low, and the added clinical benefit of having immediate surgical backup is limited in contemporary practice.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This is the first national study to assess TAVI outcomes in a center without immediate on-site CS backup.

- Among 300 consecutive patients, 30-day mortality rate was comparable to national and international cohorts, and the need for ECS was 0% (n = 0).

- These findings support the safety and feasibility of performing TAVI in selected centers without on-site CS backup.

REFERENCES

1. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

2. Généreux P, Sharma RP, Cubeddu RJ, et al. The Mortality Burden of Untreated Aortic Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2101-2109.

3. Compagnone M, Dall'Ara G, Grotti S, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Without On-Site Cardiac Surgery. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:3026-3030.

4. Ali N, Faour A, Rawlins J, et al. 'Valve for Life':tackling the deficit in transcatheter treatment of heart valve disease in the UK. Open Heart. 2021;8:001547.

5. Coisne A, Montaigne D, Aghezzaf S, et al. Association of Mortality With Aortic Stenosis Severity in Outpatients. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1424.

6. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease:A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2021;143:72-227.

7. Elbaz-Greener G, Masih S, Fang J, et al. Temporal Trends and Clinical Consequences of Wait Times for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Circulation. 2018;138:483-493.

8. Aarts HM, van Nieuwkerk AC, Hemelrijk KI, et al. Surgical Bailout in Patients Undergoing Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18:89-99.

9. Carroll JD, Mack MJ, Vemulapalli S, et al. STS-ACC TVT Registry of Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76: 2492-2516.

10. Eggebrecht H, Vaquerizo B, Moris C, et al. Incidence and outcomes of emergent cardiac surgery during transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI):insights from the European Registry on Emergent Cardiac Surgery during TAVI (EuRECS-TAVI). Eur Heart J. 2018;39: 676-684.

11. Roa Garrido J, Jimenez Mazuecos J, Sigismondi A, et al. Transfemoral TAVR at Hospitals Without On-Site Cardiac Surgery Department in Spain. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:896-898.

12. Rocha de Almeida A, Carias de Sousa M, Magro C, et al. CO 92. Telemonitoring Aortic Valvular Intervention Waiting Lista Patients Prognostic Value. Rev Port Cardiol. 2023;42:S3-S85.

13. Kobo O, Saada M, Roguin A. Can Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (TAVI) Be Performed at Institutions Without On-Site Cardiac Surgery Departments?Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2022;41:159-165.

14. Iannopollo G, Cocco M, Leone A, et al. Transcatheter aortic?valve implantation with or without on?site cardiac surgery:The TRACS trial. Am Heart J. 2025;280:7-17.

15. Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3:Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:2717-2746.

16. Guerreiro C, Ferreira PC, Teles RC, et al. Short and long-term clinical impact of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Portugal according to different access routes:Data from the Portuguese National Registry of TAVI. Rev Port Cardiol. 2020;39:705-717.

17. Eggebrecht H, Bestehorn M, Haude M, et al. Outcomes of transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation at hospitals with and without on-site cardiac surgery department:insights from the prospective German aortic valve replacement quality assurance registry (AQUA) in 17 919 patients. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2240-2248.

18. Florian E, David Z, K FM, et al. Impact of On-Site Cardiac Surgery on Clinical Outcomes After Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:2160-2167.