ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Calcified coronary nodules (CN) are among the most challenging lesions for percutaneous coronary intervention, as drug-eluting stents (DES) frequently result in suboptimal expansion, malapposition, and recurrent adverse events. Although intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) provides effective plaque modification, the optimal definitive strategy remains unclear. Drug-eluting balloons (DEB) have demonstrated potential in the treatment of complex lesions in which stent implantation may be less desirable. This trial aims to compare the safety and efficacy profile of DEB vs DES after IVL in patients with CN.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective, investigator-initiated, multicenter, non-inferiority, randomized clinical trial.

Results: A total of 128 patients with de novo CN confirmed by intracoronary imaging in vessels measuring 2.5 mm to 4.0 mm in diameter will be enrolled across 10 high-volume percutaneous coronary intervention centers. After lesion preparation with IVL, patients will be randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive a DEB or a DES. The co-primary endpoints are late lumen loss and net luminal gain at 9 ± 1 months of angiographic follow-up, both assessed by an independent core laboratory. Secondary endpoints include procedural, angiographic, and clinical outcomes, adjudicated by a blinded clinical events committee. Clinical follow-up will be conducted at 1 month, 1 year, and 2 years.

Conclusions: The DEBSCAN-IVL trial will provide the first randomized evidence comparing DEB and DES after IVL for CN.

Registered at ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06657833.

Keywords: Calcified nodule. Intravascular lithotripsy. Drug-eluting balloons. Drug-eluting stents. Complex percutaneous coronary intervention.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Los nódulos coronarios calcificados (NC) se encuentran entre las lesiones más desafiantes para la intervención coronaria percutánea, ya que los stents farmacoactivos (SFA) con frecuencia presentan expansión subóptima, mala aposición y eventos adversos recurrentes. La litotricia intravascular (LIV) permite una modificación eficaz de la placa, pero la estrategia definitiva óptima sigue sin estar clara. Los balones farmacoactivos (BFA) han mostrado resultados prometedores en lesiones complejas en las que la implantación de stents podría ser menos favorable. Este ensayo tiene como objetivo comparar la seguridad y la eficacia del BFA frente al SFA después de la LIV en pacientes con NC.

Métodos: Ensayo clínico prospectivo, por iniciativa del investigador, multicéntrico, de no inferioridad y aleatorizado.

Resultados: Un total de 128 pacientes con NC de novo confirmados mediante imagen intracoronaria en vasos de 2,5-4,0 mm de diámetro serán incluidos en 10 centros de intervencionismo coronario percutáneo de alto volumen. Tras la preparación de la lesión con LIV, los pacientes serán aleatorizados 1:1 para ser tratados con BFA o SFA. Los criterios de valoración coprimarios son la pérdida luminal tardía y la ganancia luminal neta en el seguimiento angiográfico a 9 ± 1 meses, evaluadas por un laboratorio central independiente. Los criterios secundarios incluyen resultados procedimentales, angiográficos y clínicos, adjudicados por un comité de eventos clínicos enmascarado. El seguimiento clínico se realizará a 1 mes, 1 año y 2 años.

Conclusiones: El ensayo DEBSCAN-IVL proporcionará la primera evidencia de comparación de BFA y SFA aleatorizados después de IVL en NC.

Registrado en ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT06657833.

Palabras clave: Nódulo calcificado. Litotricia intravascular. Balón farmacoactivo. Stent farmacoactivo. Intervención coronaria percutánea compleja.

Abreviaturas

CN: calcified coronary nodule. DEB: drug-eluting balloon. DES: drug-eluting stent. IVL: intravascular lithotripsy. OCT: optical coherence tomography. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Calcified coronary nodules (CN) represent the most complex type of calcified lesion for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), as they are associated with worse angiographic and clinical outcomes after drug-eluting stent (DES) implantation.1-8

Intravascular lithotripsy (IVL) has shown favorable results in this context.9 However, stent implantation after IVL may not always be the best treatment option due to suboptimal stent expansion and severe malapposition in a non-negligible percentage of patients which, along with possible nodule protrusion through the stent struts, may be associated with an increased need for new target lesion revascularization (TLR), and a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE).10-12

Drug-eluting balloons (DEB) have demonstrated to be a safe and effective alternative to DES in various settings, especially in those in which stenting is associated with worse outcomes, such as small vessel disease and in-stent restenosis.13 Therefore, their use has increased exponentially in recent years and has expanded to other lesion types.14

In the specific setting of calcified lesions, there are some data on the safety and efficacy profile of DEB after an adequate plaque modification.15-19 Moreover, in this setting, DEB have shown similar clinical outcomes with favorable late lumen loss rate compared with DES.20-23

Despite the increasing use of DEB in calcified lesions, evidence on the safety and efficacy profile of CN treatment is lacking. In this setting, where the risj of suboptimal stent expansion and apposition—and the consequent likelihood of MACE— is higher,24 a leave-nothing-behind strategy using DEB following optimal plaque modification technique may be a more appealing approach.Therefore, our aim is to compare the safety and efficacy profile of the use of DEB or DES after IVL in CN within the context of a randomized controlled trial.

METHODS

Patients and study design

The DEBSCAN-IVL trial is an investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial including 10 high-volume centers.

Patients will be randomized to receive a DEB or a DES after optimal treatment with IVL if they meet all the inclusion criteria and have no exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria are age ≥ 18 years with a clinical indication for PCI (presenting with chronic or acute coronary syndromes) in a CN-induced de novo severe coronary lesion (confirmed via intracoronary imaging) in vessels with a reference diameter between 2.5 mm and 4.0 mm. Patients who meet at least 1 of the following conditions will be excluded: inability to provide oral and written informed consent or unwillingness to return for systematic angiographic follow-up; pregnant or breastfeeding patients; cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest at the time of the index procedure; inability to maintain dual antiplatelet therapy for at least 1 month; life expectancy < 1 year; index lesion located at the left main coronary artery or in an aorto-ostial location; target lesion previously treated with stents or DEB or with high thrombus burden at the time of PCI (Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] thrombus grade ≥ 3).

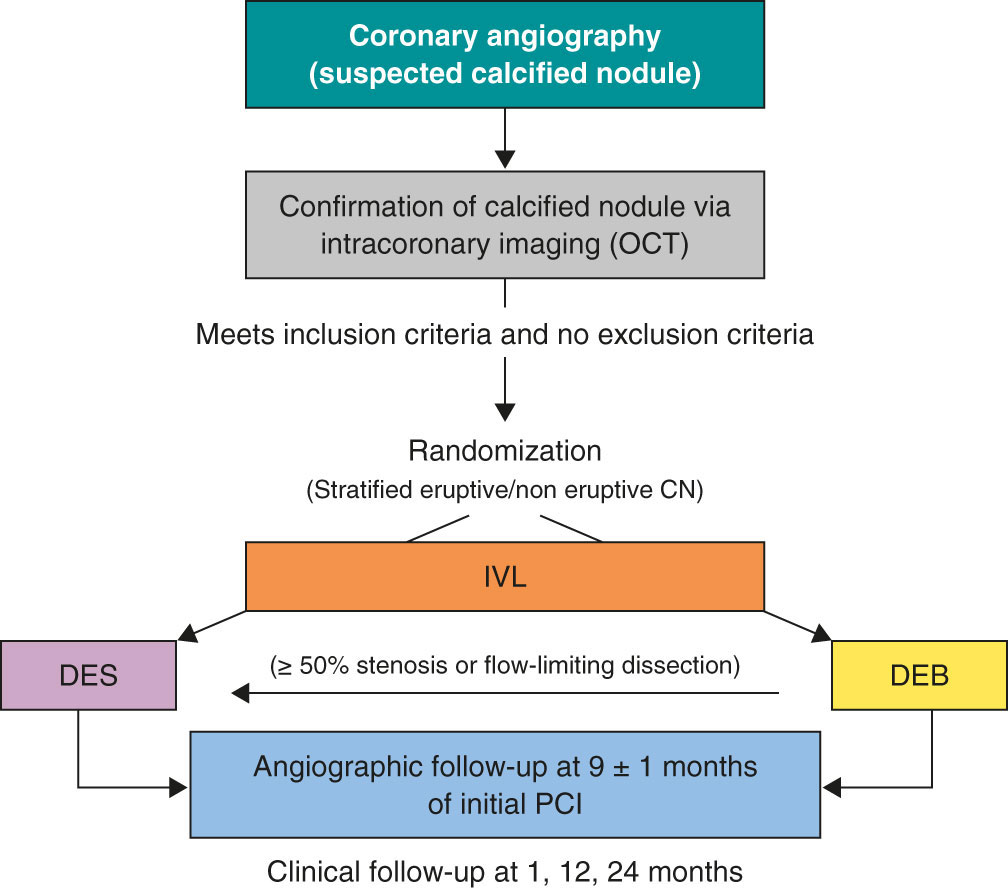

Patients who meet all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria will be treated with IVL and randomized to receive final therapy with DEB or DES. Randomization will occur via a web-based system. The complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in table 1, and the study flowchart in figure 1.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

Patients must meet all inclusion criteria:

|

Patients must not meet any criteria:

|

|

DEB, drug-eluting balloon; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. |

|

Figure 1. Central illustration. Study design flowchart. CN, calcified coronary nodule; DEB, drug-eluting balloons; DES, drug-eluting stents; IVL, intravascular lithotripsy; OCT, optical coherence tomography; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The endpoint of this study is to evaluate and compare the safety and efficacy profile of DEB or DES as final treatment strategies for CN previously modified by IVL.

Co-primary endpoints will be the late lumen loss (LLL) and net luminal gain at 9 ± 1 months of angiographic follow-up, as assessed by an independent core laboratory, with a non-inferiority hypothesis between the 2 groups. LLL is defined as the difference between postoperative and follow-up minimal lumen diameter, whereas net gain is defined as the difference between follow-up and preoperative minimal lumen diameter, according to the latest Drug Coated Balloon Academic Research Consortium Consensus Document.25

Secondary endpoints of the study will include procedural, angiographic and clinical outcomes. Procedural endpoints will include the rate of crossover between treatment groups, angiographic success (defined as final TIMI grade-3 flow and a residual final percent diameter stenosis < 30% in the DEB group or < 20% in the DES group), device success (defined as angiographic success without crossover between treatment group), procedural success (defined as angiographic success without the occurrence of severe procedural complications, including cardiac death, target vessel perioperative myocardial infarction [MI], need for new clinically driven TLR, stent thrombosis [ST], stroke, flow-limiting dissection or vessel perforation). Angiographic endpoints will include the minimal lumen diameter measured immediately after the intervention and at the time of angiographic follow-up, the residual percent diameter stenosis at both timeframes, and the rate of binary restenosis, defined as a luminal diameter reduction o≥ 50% during follow-up.25 Secondary endpoints will include procedural adverse events (such as dissection, perforation, acute vessel occlusion, slow flow or no-reflow, and intraoperative thrombosis), major hemorrhagic events (classified as Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] type ≥ 3),26 and hemodynamic instability (requiring unplanned administration of vasopressors, inotropes, or ventricular support devices), cardiac death, target lesion-related MI (TL-MI), need for TLR, and ST, and MACE (defined as a composite of cardiac death, TL-MI, and TLR). TLR and ST are defined according to the Academic Research Consortium criteria.27 MACE and its components will be assessed during the index hospitalization and at 6-month, 1-year, and 2-year follow-up visits. Detailed endpoints definitions are shown in appendix S1.

Primary outcome assessment will be conducted by a central independent core laboratory. All medical data will be anonymized and stored, and confidentiality will be protected at any time in full compliance with the current legislation. The clinical events committee (CEC) and the independent core laboratory will be blinded to the treatment group. Secondary outcomes will be assessed via centralized angiographic analysis and structured clinical follow-up, either in person or via telephone, at scheduled time points.

Devices

- – IVL: Shockwave Balloon (Shockwave Medical, United States).

- – Optical coherence tomography (OCT) or intracoronary ultrasound (IVUS) system, based on availability at each participating center.

- – DEB: paclitaxel-eluting balloon (Pantera Lux, Biotronik, Switzerland)

- – DES: new-generation zotarolimus eluting stent (Onyx Frontier, Medtronic, United States).

Procedure

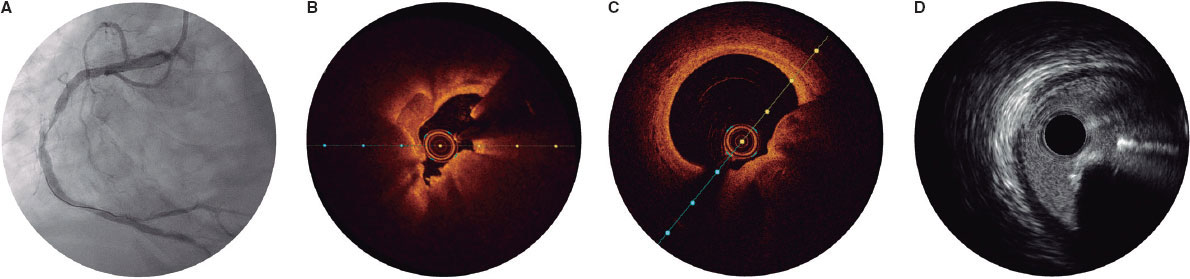

When a CN is suspected on coronary angiography, intracoronary imaging—preferably OCT, with IVUS as an alternative—will be performed to confirm the diagnosis. After confirmation of a CN in the target lesion, patients will be randomized on a 1:1 ratio to receive a DEB or a DES. Randomization will be stratified to ensure a balanced distribution of eruptive and non-eruptive nodules across both treatment groups. A CN (figure 2) will be defined as a calcified segment with an accumulation of protruding nodular calcification (small calcium deposits) with disruption of the fibrous cap (eruptive CN) or an intact thick fibrous cap (non-eruptive CN).28-30

Figure 2. Calcified nodule appearance on angiography (A), optical coherence tomography (eruptive [B] and non-eruptive [C]) and intravascular ultrasound (D).

All patients will be treated with IVL, using a balloon sized 1:1 to the vessel reference diameter. A minimum of 80 pulses per lesion is recommended. If the IVL balloon cannot cross the lesion, predilation with smaller balloons is permitted. Additionally, the use of adjuvant techniques such as rotational atherectomy or excimer laser coronary atherectomy will be allowed only when deemed necessary to facilitate IVL balloon crossing. Postdilation with a non-compliant balloon after IVL is recommended before proceeding with the final assigned treatment modality.

Once optimal lesion preparation has been achieved, defined as > 80% balloon expansion in 2 orthogonal projections with a balloon sized 1:1 to the vessel, patients will receive a DEB or a DES, according to their initial randomization. If a patient randomized to the DEB group experiences a flow-limiting dissection or exhibits a percent diameter stenosis > 50%, conversion to DES implantation will be permitted at the operator’s discretion. Similarly, any crossover from DES to DEB will be documented, along with the reasons for these procedural decisions.

It is recommended that the DEB reach the target lesion within 2 minutes, as drug loss may occur during transit.13 Thus, operators need to anticipate difficulties in reaching the target lesion (proximal coronary disease or tortuosity) and ensure optimal support prior to using the DEB. If difficulties in reaching the target lesion are anticipated, the use of guide extension catheters is recommended. The recommended DEB inflation time is 60 seconds.

The PCI will be performed according to current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines, including perio- and postoperative antithrombotic management.31,32 Patients should ideally receive dual antiplatelet therapy at least 2 to 4 hours prior to the PCI to ensure optimal platelet inhibition. In cases where this is not feasible, administration of IV antiplatelet agents, such as acetylsalicylic acid with or without cangrelor, immediately before the procedure is recommended.

Intracoronary imaging with either OCT or IVUS (the same imaging modality that was initially used) is recommended at the end of the procedure.

Angiographic analysis

Quantitative coronary imaging and intracoronary analysis of baseline and follow-up angiographies will be conducted by an independent central laboratory (Barcicore, Spain). At least 2 well-selected orthogonal views—free of foreshortening and side-branch overlap—focused on the target lesion are required after intracoronary nitroglycerine administration. These views should be obtained before treatment, after the intervention, and during follow-up angiography to ensure consistent angulation and enable accurate, reproducible measurements.

Follow-up

Post-PCI antithrombotic therapy will abide by the latest ESC clinical practice guidelines, considering the individual ischemic and bleeding risk profile of each patient.31,32 Regardless of the assigned treatment group (DEB or DES), a 6-month regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) is recommended in patients with stable coronary artery disease, and a 12-month regimen of dual antiplatelet therapy (preferably using prasugrel or ticagrelor as a P2Y12 inhibitor) in patients with acute coronary syndrome. For patients requiring chronic oral anticoagulation, the choice and duration of antithrombotic therapy will follow current guideline recommendations, with triple therapy (oral anticoagulant + aspirin + clopidogrel) limited to 1 month, whenever feasible. Electrocardiogram and troponin assessment will be performed 24 hours after the PCI. All patients will be discharged with a scheduled angiographic follow-up at 9 ± 1 months. OCT is recommended during this follow-up, especially if angiography suggests progression of coronary artery disease in the target lesion. In cases where angiography or intracoronary imaging indicates disease progression, but the percent diameter stenosis is < 90%, revascularization should be guided by ischemia and confirmed with a pressure guidewire. Clinical follow-up visits are scheduled at 12 and 24 months. Schedule of visits and data assessment throughout the study are shown in table S1.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint analysis will be performed by lesion and by intention-to-treat with a 1-sided Student t test with an alfa of 0.05 between the DES and the DEB group. A per-protocol analysis, including crossover cases, will also be conducted for sensitivity purposes. If the hypothesis of non-inferiority is confirmed, a superiority 2-sided analysis will be performed. Clinical endpoints will be analyzed on a per-patient basis.

Quantitative variables will be expressed as mean ± standard deviation if normally distributed, and as median with minimum and maximum values if they do not follow a normal distribution. Normality will be assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Qualitative variables will be described by their absolute values and frequencies, and will be expressed as absolute counts and percentages. A P < .05 will be considered statistically significant, and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) will be reported for all main analyses. For comparisons of continuous variables between the 2 groups, the Student t test will be used if normality is confirmed, or the Mann-Whitney U test if non-parametric. For comparisons across > 2 groups, the ANOVA test or the Kruskal-Wallis test will be applied, as appropriate. Associations across categorical variables will be analyzed using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when expected frequencies are small. Correlations between continuous variables will be explored using Pearson’s or Spearman’s correlation coefficient, depending on their distribution.

A multivariate analysis will be conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression with forward stepwise selection, including variables that are significantly associated with outcomes (or show a trend) in the univariate analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves will be generated for event-free survival, and differences will be assessed using the log-rank test.

Prespecified subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis will be performed according to the following prespecified categories: type of calcified nodule (eruptive vs non-eruptive), age (< 75 vs ≥ 75 years), sex (male vs female), presence of diabetes mellitus (yes vs no), location of the calcified nodule within a true bifurcation lesion involving a side branch ≥ 2.5 mm (yes vs no), and clinical presentation (acute coronary syndrome vs chronic coronary syndrome). In addition, a prespecified OCT subgroup analysis will be performed in patients with available OCT imaging at both the end of the procedure and follow, including assessments of minimal lumen area (or minimal stent area in stented segments) and minimal lumen diameter.

Sample size calculation

The hypothesis is that DEB-PCI for CN is not inferior to state-of-the-art DES-PCI in terms of LLL and net luminal gain at the lesion. The sample size calculation was based on an expected LLL of 0.20 mm in the DES group, with a non-inferiority margin (delta) of 0.30 mm, a significance level (alpha) of 5%, and a statistical power of 80%. The estimate of LLL in the control group was derived from previous studies evaluating the same DES platform.33-35 Assuming a 20% attrition rate for angiographic follow-up, 64 patients per group (128 patients in total) will be required to provide adequate statistical power. The study is not powered for clinical endpoints, which will be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

Organization and ethical concerns

The study protocol has been approved by the local ethics committees of all participant centers. Written informed consent will be obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. The DEBSCAN-IVL trial is an investigator-initiated study conducted in full compliance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines applicable to interventional and epidemiological research. The rights, safety, and well-being of all participants will be protected full compliance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, applicable EU legislation, and local legal requirements. Participant data will be handled confidentially and anonymously. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06657833). The sponsor of the study is Fundación EPIC. The study is supported by unrestricted research grants from Fundación EPIC, Shockwave Medical, Biotronik, and Medtronic.

The steering committee serves as the primary decision-making body of the trial and bears full responsibility for its scientific and clinical conduct. A clinical events committee (CEC), composed of independent interventional cardiologists not participating in the study and blinded to treatment allocation, will adjudicate all clinical events and endpoints. The CEC will operate according to pre-specified definitions outlined in the study protocol and will remain blinded to the overall trial outcomes.

DISCUSSION

CN represent the most complex type of calcified lesion for PCI, as they are associated with the worst angiographic and clinical outcomes after DES implantation.1-8 Three main factors may contribute to these unfavorable results: the nature of the nodule per se, the plaque modification technique used, and the final revascularization strategy (DES or DEB). Although our understanding of the origin and behavior of calcified nodules has grown, it remains unclear which lesions are likely to respond favorably to PCI, and which are not. Eruptive CN, for instance, may be more amenable to initial modification, yet paradoxically, they have also been associated with higher rates of adverse clinical events during follow-up.29,36

Regarding plaque modification techniques, current evidence is limited. Rotational atherectomy (RA), while commonly used, is constrained by wire bias and frequently requires large burr sizes.2 Although orbital atherectomy might overcome some of these limitations, randomized data comparing it with other advanced plaque modification techniques are lacking.37 Balloon-based techniques, in contrast, may fail to cross severely stenotic nodular lesions but have the advantage of avoiding the wire bias inherent to atherectomy.

However, conventional or scoring/cutting balloons often prove insufficient to fully modify the depth of nodular calcium, and very high-pressure special balloons carry the risk of overstretching the usually normal opposite vessel wall causing perforation. In this context, IVL has emerged as a promising alternative, offering the most robust evidence to date for nodular plaque modification.29,38

Traditionally, stent implantation has been the standard definitive treatment for CN.23 However, stenting in nodular lesions frequently leads to suboptimal expansion and incomplete apposition, particularly at the shoulders of the nodule. Moreover, In these patients, TLR is often driven not by classic in-stent restenosis, but by late protrusion of the calcified nodule through the stent struts.10,11,39 These limitations have generated interest in a “leave nothing behind” strategy after effective plaque modification.

DEB have demonstrated to be safe and effective in various settings, particularly small vessel disease and in-stent restenosis, where DES implantation may be less favorable.13 Therefore, their use has grown significantly in recent years.14 In the context of calcified lesions, there are concerns that adequate drug-uptake may be compromised, but preliminary evidence suggests DEB may offer good outcomes after adequate plaque preparation.15-17 For instance, Ito et al.18 evaluated a total of 81 patients with de novo lesions treated with DEB, including 46 with calcified lesions. While LLL and restenosis appeared slightly higher in the calcified group, these differences were not statistically significant and did not translate into worse clinical outcomes at 2 years. Notably, 82% of these lesions were pre-treated with RA. Similarly, Nagai et al. reported a TLR rate of 16.3% in 190 severely calcified lesions treated with RA followed by DEB.19 Rissanen et al. found MACE rates of 14% and 20% at 12 and 24 months, respectively, in 82 complex de novo calcified lesions treated with DEB after RA and balloon predilation, with very low rates of clinically driven TLR.20 Furthermore, favorable findings have been reported by Shiraishi et al., including a subset of calcified nodules.16

Comparative studies have further explored DEB vs DES in calcified lesions. Ueno et al.21 conducted a single-center cohort study comparing the clinical outcomes of 166 severe calcified lesions treated with either DEB or DES after RA at a median follow-up of 3 years. The TLR rates were similar across the groups (15.6% vs 16.3%; P = .99), while LLL was significantly lower in the DEB group (0.09 mm vs 0.52 mm; P =.009). Iwasaki et al.22 compared 194 patients with de novo calcified lesions in non-small vessels the RA + DEB vs RA + DES strategies. There were no significant differences at 1 year in terms of MACE, cardiac death, myocardial infarction, TLR or hemorrhage.

Despite this data on the performance of DEB in calcified lesions, evidence on the safety and efficacy profile in the CN setting is lacking. However, given the high likelihood of suboptimal stent expansion and malapposition in this setting, which may lead to increased MACE risk,24 a metal-free strategy using DEB following optimal plaque modification seems to be an attractive and feasible approach.

Intracoronary imaging-guided PCI has been consistently associated with improved procedural outcomes and a reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events, including mortality, particularly in complex lesions.40 Intracoronary imaging plays a pivotal role in this context. Compared with conventional angiography, it provides a far more accurate assessment of coronary disease severity and plaque morphology.1 This is particularly relevant in calcified and complex lesions, where procedural planning and outcomes are significantly impacted by the detailed anatomical insights obtained. OCT, in particular, offers superior spatial resolution compared to IVUS, allowing for precise quantification of the calcium burden.28,41

In the case of CN, OCT enables accurate assessment of the plaque substrate and procedural results, including stent expansion and apposition, or in DEB-treated lesions, the extent of plaque modification.

The DEBSCAN-IVL trial will be comparing the safety and efficacy profile of DEB vs DES after lesion preparation with IVL in patients with CN, assessing both angiographic and clinical outcomes. Moreover, the trial will provide valuable information on the underlying plaque morphology and the response to different PCI strategies following the systematic use of intracoronary imaging. The central hypothesis of the study is that a DEB strategy, after IVL-based plaque modification in calcified nodules, is not inferior to DES implantation in terms of LLL and net gain, while potentially reducing the risk of long-term adverse events through improved biocompatibility and vessel healing. In addition, the analysis will be stratified according to nodule morphology, specifically differentiating eruptive vs non-eruptive CN, 2 entities that are thought to have distinct biological behavior and potentially different response to plaque modification and PCI.6,7,29,36 This stratified analysis may provide novel insights into the prognostic and therapeutic implications of nodule subtype and guide future individualized interventional strategies.

CONCLUSIONS

The DEBSCAN-IVL trial is an investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial designed to compare the safety and efficacy profile of the use of DEB or DES after IVL in CN. The co-primary endpoints are LLL and net gain at 9 ± 1 months of angiographic follow-up. The findings are expected to inform clinical decision-making and support a more individualized approach on the management of this specific type of calcified coronary disease.

DATA AVAILABILITY

This manuscript refers to the protocol of a study, therefore there is not available data related to this manuscript.

FUNDING

The DEBSCAN-IVL study was supported by non-restricted grants from Shockwave, Biotronik and Medtronic.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained, and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to enrollment. The confidentiality and anonymity of participants were strictly preserved throughout the study. Sex and gender considerations were addressed following the recommendations of the SAGER guidelines to ensure accurate and equitable reporting.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence assisted technologies were used exclusively to support language editing and improvement of style. No artificial intelligence tools were employed to generate, analyze, or interpret the data. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity, accuracy, and originality of the manuscript content.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Jurado-Román, M. Basile and R. Moreno drafted the manuscript. The remaining authors performed a critical review, and all authors approved the final version for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Jurado-Román is a proctor for Abbott, Boston Scientific, World Medica, and Philips; has received consulting fees from Boston Scientific and Philips; and has received speaker fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Shockwave Medical, Philips, and World Medica. J.M. Montero-Cabezas received a research grant from Shockwave Medical and speaker fees from Abiomed, Boston Scientific, and Penumbra Inc. A. Pérez de Prado reports receiving institutional research grants from Abbott and Shockwave Medical and speaker honoraria and consulting fees from iVascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, B. Braun, and Abbott Vascular. I.J. Amat-Santos is proctor for Boston Scientific. A. Pérez de Prado, F. Alfonso and R. Moreno are associate editors of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- CN are among the most complex calcified lesions for PCI, as DES often result in suboptimal expansion, malapposition, and long-term adverse events. IVL is an effective and safe technique for modifying nodular calcium. DEB have proven effective in complex lesions such as small vessel disease and in-stent restenosis, suggesting potential utility where stent implantation might be suboptimal. However, robust evidence on the safety and efficacy of DEB specifically for CN after IVL is currently lacking.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The DEBSCAN-IVL trial will be the first randomized study to compare DEB and DES after IVL in patients with CN. It will evaluate angiographic endpoints such as late lumen loss and net luminal gain, as well as procedural and clinical outcomes. The study is expected to provide crucial insights into whether a “leave-nothing-behind“ approach with DEB can achieve comparable efficacy to DES while potentially improving vessel healing and reducing longterm complications in this challenging patient population.

REFERENCES

1. Jurado-Román A, Gómez-Menchero A, Gonzalo N, et al. Plaque modification techniques to treat calcified coronary lesions. Position paper from the ACI-SEC. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:46-61.

2. Morofuji T, Kuramitsu S, Shinozaki T, et al. Clinical impact of calcified nodule in patients with heavily calcified lesions requiring rotational atherectomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:10-19.

3. Lee T, Mintz GS, Matsumura M, et al. Prevalence, Predictors, and Clinical Presentation of a Calcified Nodule as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:883-891.

4. Lei F, Yin Y, Liu X, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Different Calcified Culprit Plaques in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4018.

5. Mintz GS. Intravascular Imaging of Coronary Calcification and Its Clinical Implications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:461-471.

6. Torii S, Sato Y, Otsuka F, et al. Eruptive Calcified Nodules as a Potential Mechanism of Acute Coronary Thrombosis and Sudden Death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:1599-1611.

7. Sato T, Matsumura M, Yamamoto K, et al. Impact of Eruptive vs Noneruptive Calcified Nodule Morphology on Acute and Long-Term Outcomes After Stenting. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:1024-1035.

8. Nagata T, Minami Y, Katsura A, et al. Optical coherence tomography factors for adverse events in patients with severe coronary calcification. Int J Cardiol. 2023;376:28-34.

9. Ali ZA, Nef H, Escaned J, et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Coronary Intravascular Lithotripsy for Treatment of Severely Calcified Coronary Stenoses:The Disrupt CAD II Study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:e008434.

10. Kaihara T, Higuma T, Kotoku N, et al. Calcified Nodule Protruding Into the Lumen Through Stent Struts:An In Vivo OCT Analysis. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:116-118.

11. Kawai K, Akahori H, Imanaka T, et al. Coronary restenosis of in-stent protruding bump with rapid progression:Optical frequency domain imaging and angioscopic observation. J Cardiol Cases. 2019;19:12-14.

12. Isodono K, Fujii K, Fujimoto T, et al. The frequency and clinical characteristics of in-stent restenosis due to calcified nodule development after coronary stent implantation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;37:15-23.

13. Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-Coated Balloons for Coronary Artery Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:1391-1402.

14. Jurado-Román A, Freixa X, Cid B, et al. Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry. 32nd official report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2022). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2023;76:1021-1031.

15. Basavarajaiah S, Loku Waduge BH, Watkin R, Athukorala S. Is a high calcific burden an indication, or a contraindication for Drug Coated Balloon?Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021;22:1087-1093.

16. Shiraishi J, Kataoka E, Ozawa T, et al. Angiographic and Clinical Outcomes After Stent-less Coronary Intervention Using Rotational Atherectomy and Drug-Coated Balloon in Patients with De Novo Lesions. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2020;21:647-653.

17. Ho HH, Lee JH, Khoo DZL, Hpone KKS, Li KFC. Shockwave intravascular lithotripsy and drug-coated balloon angioplasty in calcified coronary arteries:preliminary experience in two cases. J Geriatr Cardiol. 2021;18:689-691.

18. Ito R, Ueno K, Yoshida T, et al. Outcomes after drug?coated balloon treatment for patients with calcified coronary lesions. J Intervent Cardiol. 2018;31:436-441.

19. Nagai T, Mizobuchi M, Funatsu A, Kobayashi T, Nakamura S. Acute and mid-term outcomes of drug-coated balloon following rotational atherectomy. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2020;35:242-249.

20. Rissanen TT, Uskela S, Siljander A, et al. Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Complex Calcified Lesions With Drug?Coated Balloon After Rotational Atherectomy. J Intervent Cardiol. 2017;30:139-146.

21. Ueno K, Morita N, Kojima Y, et al. Safety and Long-Term Efficacy of Drug-Coated Balloon Angioplasty following Rotational Atherectomy for Severely Calcified Coronary Lesions Compared with New Generation Drug-Eluting Stents. J Intervent Cardiol. 2019;2019:1-10.

22. Iwasaki Y, Koike J, Ko T, et al. Comparison of drug-eluting stents vs drug-coated balloon after rotational atherectomy for severely calcified lesions of nonsmall vessels. Heart Vessels. 2021;36:189-199.

23. Rivero-Santana B, Jurado-Roman A, Galeote G, et al. Drug-eluting balloons in Calcified Coronary Lesions:A Meta-Analysis of Clinical and Angiographic Outcomes. J Clin Med. 2024;13:2779.

24. Muramatsu T, Kozuma K, Tanabe K, et al. Clinical expert consensus document on drug-coated balloon for coronary artery disease from the Japanese Association of Cardiovascular Intervention and Therapeutics. Cardiovasc Interv Ther. 2023;38:166-176.

25. Fezzi S, Scheller B, Cortese B, et al. Definitions and standardized endpoints for the use of drug-coated balloon in coronary artery disease:consensus document of the Drug Coated Balloon Academic Research Consortium. EuroIntervention. 2025;21:e1116-e1136.

26. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized Bleeding Definitions for Cardiovascular Clinical Trials:A Consensus Report From the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736-2747.

27. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized End Point Definitions for Coronary Intervention Trials:The Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document. Circulation. 2018;137:2635-2650.

28. Johnson TW, Räber L, Di Mario C, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 2:acute coronary syndromes, ambiguous coronary angiography findings, and guiding interventional decision-making:an expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2566-2584.

29. Fernández-Cordón C, Brilakis ES, García-Gómez M, et al. Calcified nodules in the coronary arteries:systematic review on incidence and percutaneous coronary intervention outcomes. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2025;78:977-991.

30. Guagliumi G, Pellegrini D, Maehara A, Mintz GS. All calcified nodules are made equal and require the same approach:pros and cons. EuroIntervention. 2023;19:e110-e112.

31. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes:Developed by the task force on the management of acute coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720-3826.

32. Vrints C, Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes:Developed by the task force for the management of chronic coronary syndromes of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3415-3537.

33. Latib A, Colombo A, Castriota F, et al. A Randomized Multicenter Study Comparing a Paclitaxel Drug-eluting balloon With a Paclitaxel-Eluting Stent in Small Coronary Vessels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:2473-2480.

34. Cannon LA, Simon DI, Kereiakes D, et al. The XIENCE nanoTM everolimus eluting coronary stent system for the treatment of small coronary arteries:The SPIRIT small vessel trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;80:546-553.

35. Cortese B, Di Palma G, Guimaraes MG, et al. Drug-Coated Balloon Versus Drug-Eluting Stent for Small Coronary Vessel Disease. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:2840-2849.

36. Prati F, Gatto L, Fabbiocchi F, et al. Clinical outcomes of calcified nodules detected by optical coherence tomography:a sub-analysis of the CLIMA study. EuroIntervention. 2020;16:380-386.

37. Shin D, Dakroub A, Singh M, et al. Debulking Effect of Orbital Atherectomy for Calcified Nodule Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17.

38. Ali ZA, Kereiakes D, Hill J, et al. Safety and Effectiveness of Coronary Intravascular Lithotripsy for Treatment of Calcified Nodules. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16(9):1122-1124.

39. Madhavan MV, Alsaloum M, Maehara A, et al. Recurrent Calcified Nodule Protrusion Through Stent Struts After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of the RCA. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2023;16:2463-2465.

40. Stone GW, Christiansen EH, Ali ZA, et al. Intravascular imaging-guided coronary drug-eluting stent implantation:an updated network meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2024;403:824-837.

41. Amabile N, RangéG, Landolff Q, et al. OCT vs Angiography for Guidance of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention of Calcified Lesions:The CALIPSO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10:666.