The comprehensive management of patients with congenital heart disease is one of the major challenges in contemporary cardiology. In its early stages, the management of these patients was based primarily on diagnosis and palliative care. Afterwards, the goal shifted to ensuring survival, and, currently, the challenge is for patients to reach adulthood with good quality of life, minimizing morbidity associated with their congenital heart condition and prior procedures, while ensuring structured follow-up.

The major shift came from 2 parallel revolutions: advances in diagnostic capability and structural heart procedures. Due to developments in echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography, early and precise diagnosis is now possible—even in utero—allowing clinicians to properly inform families about the diagnosis and prognosis of these conditions. At the same time, surgical advances and, notably, significant progress made in percutaneous coronary interventions have transformed the natural course of this disease.

Cardiac catheterization, initially conceived as a diagnostic tool, soon acquired a decisive therapeutic role. In 1953, Rubio Álvarez et al.1 performed the first balloon valvulotomy. A decade later, Rashkind and Miller2 described atrial septostomy. These milestones marked the beginning of percutaneous coronary intervention, first as a palliative therapy and later as an established therapeutic option. Currently, many patients avoid surgery, lengths of stay are shorter, recovery is faster, and percutaneous coronary intervention has become a well-established, safe, and effective alternative.3

Percutaneous procedures are now the first-line therapy for obstructive lesions (valvular stenosis, aortic coarctation, etc.) and closure of septal defects and ducts (patent ductus arteriosus). Moreover, these procedures often serve as essential adjuncts in the management of complex congenital heart disease, including in patients with single-ventricle physiology who have undergone cavopulmonary diversion techniques.

In Spain, hemodynamic activity in congenital heart disease is distributed across 3 different types of cath lab based on the profile of the patients: pediatric labs (primarily for patients < 18 years), adult labs (primarily for patients ≥ 18 years), and mixed labs (no age distinction), which in some cases differ by working teams. Diagnostic catheterization remains the most frequently performed procedure, especially in adult cath labs accounting for 65% of cases.4

With increasing survival, a growing number of patients with congenital heart disease reach adulthood, creating the need for repeated diagnostic and therapeutic catheterizations, which are often prolonged and technically complex. Optimal management requires integrating a deep understanding of congenital heart disease pathophysiology with expertise in vascular complications typical of adulthood.

The complexity of many scenarios—both biventricular (eg, tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, or transposition of the great arteries repaired with atrial or arterial switch) and single-ventricle anatomies (various forms of cavopulmonary diversion)—requires more than just technology: it demands true collaboration among teams. Cumulative experience demonstrates that the combined expertise of pediatric and adult interventional cardiologists generates irreplaceable added value. The pediatric interventional cardiologist contributes knowledge on congenital physiology, long-term disease progression, and complications associated with palliative or corrective procedures performed throughout life, whereas the adult interventional cardiologist contributes experience with device technology and vascular access issues typical of older patients.

Although this synergy benefits most clinical scenarios, it is especially relevant in the following:

- – Closure of complex defects: sinus venosus atrial septal defects (associated with anomalous pulmonary venous drainage), ventricular septal defects, persistent ductus arteriosus in adults with pulmonary hypertension or calcification, and dehiscence of surgical conduits (mainly in patients with atrial switch procedures for transposition of the great arteries).

- – Treatment of obstructive lesions: aortic coarctation (especially in patients with prior childhood procedures); stenosis of surgically placed conduits (atrial switch procedures for transposition of the great arteries or right ventricle–to–pulmonary artery conduits); or treatment of branch pulmonary arteries with angioplasty with or without stenting.

- – Pulmonary valve procedures: this is a rapidly expanding field in which the incorporation of multiple techniques now allows treatment of dilated right ventricular outflow tracts resulting from childhood surgical procedures, with excellent results comparable to surgery but with reduced procedural morbidity.5 Therefore, techniques involving stenting in dilated outflow tracts allow subsequent placement of balloon-expandable valves with excellent outcomes. However, the major forthcoming advance is the consolidation of self-expandable valves, which simplify valve implantation. In these situations, the experience of adult interventional cardiologists with self-expandable valves in other settings, such as aortic valve procedures, is highly valuable.

- – Evaluation of single-ventricle physiology: it requires repeated cardiac catheterizations from the earliest stages of life. The pediatric interventional cardiologist contributes not only essential insight into the underlying pathophysiology but also expertise in managing complications associated with single-ventricle physiology and the palliative procedures needed to help patients reach adulthood in the best possible functional condition. Consequently, these patients often undergo interventions for stenosis of palliative conduits or branch pulmonary arteries, closure of systemic–pulmonary collaterals, or optimization of Fontan circulation through creation or closure of fenestrations.6

- – Coronary anomalies and complications: the adult interventional cardiologist plays a crucial role, as experience in areas such as atherosclerotic disease is invaluable in addressing and treating coronary anomalies percutaneously.

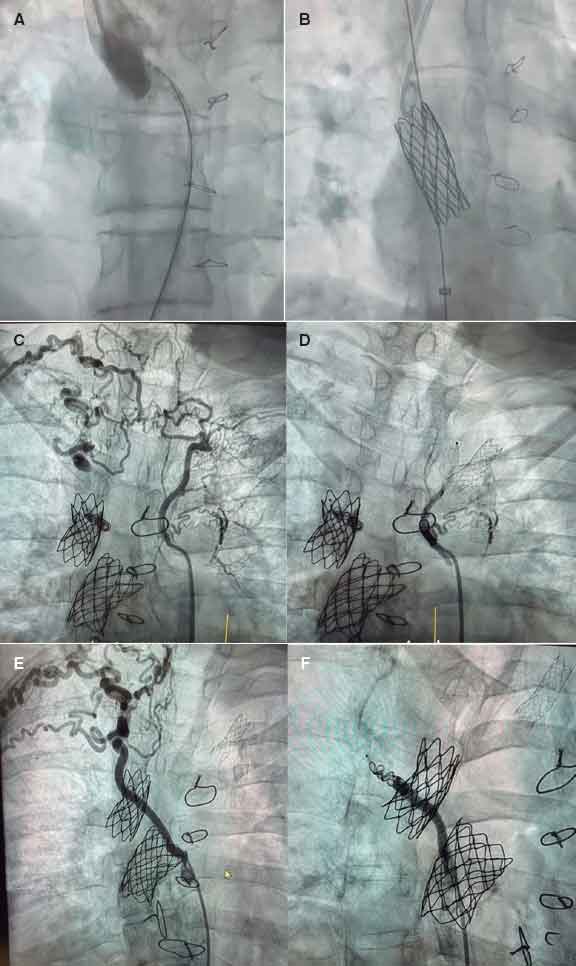

In our setting, the joint work model established since 2015 between pediatric and adult teams illustrates this philosophy. It is not just about sharing a cath lab but generating shared spaces for discussion and decision-making through multidisciplinary clinical sessions to standardize criteria and enable individualized strategy planning. A recent example reflecting the benefits of this collaborative model is a Fontan optimization case involving stenting and collateral closure. The patient was a 41-year-old woman with complex congenital heart disease and single-ventricle physiology—characterized by atrioventricular concordance with ventriculoarterial discordance, complete transposition of the great arteries, a large ventricular septal defect, pulmonary stenosis, and right ventricular hypoplasia—who had undergone multiple surgical procedures (Blalock–Taussig shunt at 13 months, systemic–pulmonary shunt at 2.5 years, bidirectional Glenn at 9 years, and extracardiac Fontan at 17 years). She exhibited reduced functional capacity and Fontan-associated hepatopathy. Cardiac catheterization confirmed a severely calcified Fontan conduit with significant stenosis at its insertion into the right pulmonary artery. Balloon sizing was performed, followed by implantation of a covered stent postdilated with a 20-mm balloon, achieving a good result. A marked stenosis at the Glenn-to–right pulmonary artery anastomosis was confirmed via right internal jugular vein, and a 34 mm bare-metal stent was implanted (figure 1A,B). The aortography performed via arterial access revealed the presence of large aortopulmonary collaterals supplying the 2 upper lung lobes, which were successfully occluded. The first one, toward the right and left upper lobes, was closed using an Amplatzer Vascular Plug 4 (Abbott Cardiovascular, United States) and coils; the second, toward the right upper lobe, was also closed with an Amplatzer Vascular Plug 4 and coils (figure 1C,F). This case illustrates the synergy between pediatric and adult interventional cardiologists in completing treatment.

Figure 1. Fontan optimization. A: stenosis at the Glenn–right pulmonary artery anastomosis. B: bare-metal stent implanted in the stenosis. C: large aortopulmonary collateral supplying the right and left upper lung lobes. D: occlusion of this collateral. E: large aortopulmonary collateral supplying the right upper lobe. F: occlusion of the collateral.

The increasing number of adults with congenital heart disease has led to more frequent, longer, and technically demanding procedures, requiring combined expertise in congenital heart disease and adult vascular complications. The joint cath-lab model for congenital heart disease should be promoted to facilitate individualized case discussion and procedural planning, both of which are essential for therapeutic success. Cross-disciplinary training and communication among teams are critical to establishing a modern, collaborative approach to interventional care in congenital heart disease. The European clinical practice guidelines on the management of adult congenital heart disease emphasize the importance of a structured transition and the need for multidisciplinary heart teams.7 Furthermore, studies show that long-term outcomes improve significantly in centers with combined pediatric and adult experience.5

The field of congenital heart disease reminds us that progress does not come from isolated disciplines, but from shared effort. The current challenge is no longer simply to extend life, but to ensure its quality. Therefore, integration of pediatric and adult cardiology in the interventional management of congenital heart disease is no longer optional, but essential.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Informed consent was obtained from the patient described in the case, including approval for publication.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Pastora Gallego and Dr. José F. Díaz Fernández for their collaboration in reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Rubio Álvarez V, Limon RL, Soni J. Valvulotomías intracardiacas por medio de un catéter. Arch Inst Cardiol Mex. 1953;23:784-792.

2. Rashkind WJ, Miller WW. Creation of an atrial defect without thoracotomy:a palliative approach to complete transposition of the great arteries. JAMA. 1966;196:991-992.

3. Sánchez Andrés A, Carrasco Moreno JI. El cateterismo cardiaco como tratamiento de las cardiopatías congénitas. Acta Pediatr Esp. 2009;67:53-59.

4. Rueda Núñez F, Abelleira Pardeiro C, Insa Albert B, et al. Dosimetric parameters in congenital cardiac catheterizations in Spain:the GTH-SECPCC Radcong-21 multicenter registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:254-262.

5. Baumgartner H, De Backer J, Babu-Narayan SV, et al.;ESC Scientific Document Group. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of adult congenital heart disease:The Task Force for the management of adult congenital heart disease of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2021;42:563-645.

6. Rychick J, Atz AM, Celermajer DS, et al. Evaluation and Management of the Child and Adult With Fontan Circulation:A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;140:e234-e284.

7. Moons P, Bratt E-L, De Backer J, et al. Transition to adulthood and transfer to adult care of adolescents with congenital heart disease:a global consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4213-4223.