ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Stent thrombosis (ST) is a rare but potentially fatal complication of percutaneous coronary interventions. With its high spatial resolution, optical coherence tomography (OCT) allows identification of underlying mechanical causes of stent thrombosis that may be overlooked by conventional angiography.

Methods: We conducted a prospective, single-center registry that consecutively included patients with a definitive diagnosis of ST who underwent OCT at the acute presentation. The presence of underlying mechanical abnormalities was assessed, and their likelihood as the primary cause of ST was determined. In-hospital and follow-up prognosis was evaluated.

Results: A total of 105 patients were included in the final analysis. Mechanical abnormalities were identified by the OCT in 87% of cases and deemed the most probable cause of ST in 77.1%. Findings varied significantly by timing of stent thrombosis: in acute cases, no mechanical abnormality was most common (41.8%); in subacute cases, stent underexpansion predominated (47.8%); in late cases, malapposition was most frequent (30.8%); and in very late cases, neoatherosclerosis was the leading cause (52%). However, no significant differences were found in relation to the type of stent involved. In all cases, treatment was tailored to correct the detected abnormality, with a new stent being implanted in 52% of patients. There were no OCT-related complications.

Conclusions: OCT is a safe and valuable tool in the assessment of ST as it allows the identification of distinct causative mechanisms according to timing of ST and helps optimize the management of patients experiencing this rare but serious complication.

Keywords: Optical coherence tomography. Stent thrombosis. Intracoronary imaging.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La trombosis del stent (TS) es una complicación infrecuente del intervencionismo coronario, pero potencialmente letal. Su fisiopatología es multifactorial y en algunos casos no está bien esclarecida. La tomografía de coherencia óptica (OCT) ofrece una alta resolución espacial y permite identificar causas mecánicas subyacentes relacionadas con la TS que escapan a la angiografía convencional.

Métodos: Registro prospectivo unicéntrico que incluyó consecutivamente pacientes con diagnóstico de TS definitiva a los que se realizó OCT en el momento agudo. Se evaluó la presencia de anomalías mecánicas subyacentes y se estableció si podían considerarse la causa más probable de la TS. Se evaluaron el pronóstico intrahospitalario y la evolución clínica durante el seguimiento.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 105 pacientes. Se identificaron anomalías mecánicas por OCT en el 87% de los casos, y finalmente se establecieron como causa más probable de la TS en el 77,1%. Los hallazgos difirieron de manera significativa en función de la temporalidad de las TS: en las agudas, lo más frecuente fue no encontrar ninguna anomalía mecánica (41,8%); en las subagudas, predominó la infraexpansión del stent (47,8%); en las tardías, la mala aposición (30,8%), y en las muy tardías, la neoateroesclerosis (52%). En cambio, no se encontraron diferencias en los hallazgos de OCT en función del tipo de stent trombosado. En todos los casos se realizó un tratamiento dirigido a corregir la anomalía detectada, con implante de nuevo stent en el 52% de los pacientes. No se detectaron complicaciones relacionadas con la técnica de OCT.

Conclusiones: La OCT es una herramienta segura y útil en el estudio de la TS. Permite identificar mecanismos causales específicos en función de la temporalidad y optimizar el tratamiento de los pacientes que sufren esta rara, pero grave, complicación.

Palabras clave: Tomografía de coherencia óptica. Trombosis del stent. Imagen intracoronaria.

Abbreviations

OCT: optical coherence tomography. ST: stent thrombosis.

INTRODUCTION

Technological advances in coronary intervention, particularly the development of new-generation drug-eluting stents, have transformed the treatment of ischemic heart disease by effectively reducing restenosis and improving clinical outcomes for the patients.1 Nonetheless, stent thrombosis (ST) remains a rare but devastating complication, with an associated mortality rate of up to 40%.2 Its pathophysiological mechanisms are complex and multifactorial, involving patient-related factors, implantation technique, stent type, and the natural progression of the disease.3

Traditionally, coronary angiography has been the tool of choice for assessing potential complications after stent implantation. However, its inability to adequately visualize the interaction between the stent and the vessel wall limits its diagnostic utility. In this context, optical coherence tomography (OCT), owing to its excellent spatial resolution, enables in vivo identification of underlying mechanical abnormalities that may be responsible for or contribute to ST.

The primary endpoint of this study was to evaluate the role of OCT in characterizing the mechanisms involved in ST, analyzing its feasibility, safety profile, therapeutic implications, and potential to optimize revascularization strategies in this complex clinical setting. Preliminary findings from this study were reported previously,4 and the final results are presented herein.

METHODS

Study population

We conducted a prospective, single-center registry that consecutively included patients with a diagnosis of definite ST, as defined by Academic Research Consortium criteria, from October 2013 through December 2022 at Hospital Universitario de La Princesa (Madrid, Spain). Throughout this period, stents were implanted in 6881 patients. Patients with severe hemodynamic instability or lesions inaccessible with the OCT catheter were excluded.

We applied a systematic protocol that included OCT acquisition before and after treatment. If antegrade flow was not restored after crossing the lesion with the guidewire, thrombus aspiration was recommended; furthermore, when TIMI grade 0–1 flow persisted, inflation of a balloon < 2 mm in diameter at low pressure was recommended to avoid distortion of the underlying lesion. The final treatment strategy for ST was left to the operator’s discretion.

ST was classified based on the interval since implantation as acute (< 24 h), subacute (24 h to 30 d), late (30 d to 1 y), or very late (> 1 y). Stents were categorized as bare-metal, first-generation drug-eluting, new-generation drug-eluting, or bioresorbable stents.

We performed prospective clinical follow-up to assess in-hospital mortality and, after discharge, a composite of cardiac death, recurrent myocardial infarction, recurrent ST, or repeat culprit vessel revascularization.

The study protocol was approved by Hospital Universitario de La Princesa Ethics Committee, and all patients gave their prior written informed consent before being included in the study.

OCT acquisition and analysis

OCT systems available at the time (Dragonfly, St. Jude Medical, and OPTIS AptiVue, Abbott) were used. Images were acquired with a nonocclusive technique and a contrast volume of 15 mL at a rate of 5 mL/s for the left coronary system and 12 mL at a rate of 4 mL/s for the right coronary artery. The analyzed segment included the stent and 10 mm adjacent to its edges. Poor-quality studies due to insufficient flushing or artefacts were excluded. Additionally, we performed a cross-sectional morphometric analysis, including minimum lumen area, minimum and maximum stent area, reference areas and diameters, stent expansion index (minimum stent area / mean reference area ×100), thrombus burden (length and area), and malapposition (axial distance from the strut surface to the lumen border greater than the strut thickness [significant if > 200 µm]).5 Struts directly exposed to the vessel lumen were classified as uncovered. Neoatherosclerosis was defined as neointimal changes including lipidic, fibro-lipidic, or calcified tissue. Plaque rupture was assessed too. The presence of edge dissection (separation of vascular tissue extending into the media, ≥ 2 mm in length and > 60°)6 or stent edge disease (ruptured lipid plaque adjacent to the stent edge, due to incomplete coverage or disease progression)7,8 was evaluated.

Primary endpoint: mechanical abnormalities and dominant finding

We analyzed the presence of mechanical abnormalities and identified a dominant finding for each case. When multiple abnormalities coexisted, we defined the dominant finding as the one prevailing in the area with the greatest thrombus burden.9 Potentially causative mechanical abnormalities included edge dissection, underexpansion, severe malapposition, edge disease progression, neoatherosclerosis, and uncovered struts (for late and very late ST). Furthermore, we recorded the absence of mechanical abnormalities. The dominant finding was, then, assessed as the potential main cause of ST, after excluding other possible causes, such as inadequate antiplatelet therapy or prothrombotic clinical conditions. Predictors of neoatherosclerosis and plaque rupture in very late ST were also studied.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean (SD) or median (interquartile range, P25–P75) and compared using the Student t test or Wilcoxon test. For comparisons across more than 2 groups, ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Logistic regression models were applied to identify possible predictors of in-hospital mortality, and Cox regression models were used for post discharge events. Survival analyses were performed with Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests. Statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

RESULTS

Clinical and angiographic characteristics

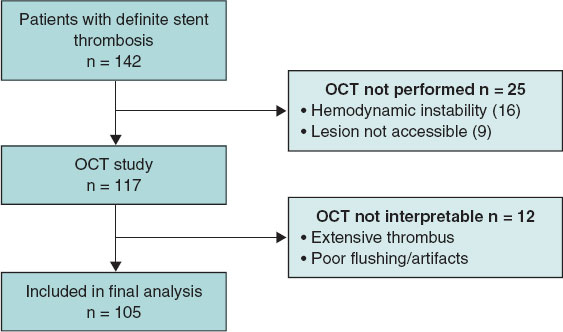

A total of 142 patients with a diagnosis of definite ST were registered, 105 of whom were included in the final analysis (figure 1). A total of 17 cases of acute ST (16%), 23 cases of subacute ST (22%), 13 cases of late ST (12%), and 52 cases of very late ST (50%) were reported. The baseline patient characteristics based on the ST timing (acute/subacute vs late/very late) are shown in table 1. The most common presentation was ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (81.9%), and the most frequently affected vessel was the left anterior descending coronary artery (42%). Most thrombosed devices were new-generation drug-eluting stents (53.3%), followed by bare-metal stents (28.6%), first-generation drug-eluting stents (13.3%), and bioresorbable scaffolds (4.8%). Bare-metal stents were significantly more common in late/very late ST, whereas new- generation drug-eluting stents and bioresorbable scaffolds were more common in acute/subacute ST. For ST treatment, drug-eluting stents and drug-coated balloons were used significantly more often in late and very late ST, whereas glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and balloon optimization were more frequently employed in acute and subacute ST.

Table 1. Baseline, angiographic, and procedural characteristics of the study population

| Variables | Overall 105 (%) | Acute/Subacute ST n = 40 (%) | Late/Very late ST n = 65 (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65.8 ± 11.8 | 49 | 82 | – |

| Male sex | 89 (84.8) | 30 (76.9) | 59 (89.4) | .150 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Smoking | 47 (44.8) | 16 (41) | 31 (47) | .697 |

| Hypertension | 68 (64.8) | 25 (64.1) | 43 (65.1) | 1.0 |

| Dyslipidemia | 69 (65.7) | 19 (48.7) | 50 (75.7) | .009 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 (26.7) | 10 (25.6) | 18 (27.8) | 1.0 |

| Previous treatment | < .001 | |||

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 45 (40.9) | 32 (80) | 13 (20) | |

| Single antiplatelet therapy | 53 (50.5) | 7 (18) | 46 (69.7) | – |

| None | 5 (3.8) | 0 | 5 (7.6) | – |

| Clinical presentation | < .001 | |||

| STEMI | 83 (81.9) | 34 (85) | 49 (75.3) | |

| Killip-Kimball class IV | 14 (13.3) | 5 (12.8) | 9 (13.6) | – |

| Stents analyzed | 105 | 40 | 65 | < .001 |

| Bare-metal stent | 30 (28.6) | 6 (15.4) | 24 (36.4) | – |

| First-generation DES | 14 (13.3) | 1 (2.6) | 13 (19.7) | – |

| New-generation DES | 56 (53.3) | 29 (72.5) | 27 (41.5) | – |

| Bioresorbable scaffold | 5 (4.8) | 4 (10.3) | 1 (1.5) | – |

| Type of treatment | < 0.001 | |||

| Conservative | 6 (5.7) | 2 (5.3) | 2 (3.1) | – |

| Standard balloon (SC/NC) | 24 (22.9) | 13 (34.2) | 11 (16.9) | – |

| Drug-coated balloon | 4 (3.8) | 0 | 4 (6.1) | – |

| Drug-eluting stent | 52 (49.5) | 12 (30) | 40 (61.5) | – |

| Bioresorbable stent | 3 (2.9) | 0 | 3 (4.6) | – |

| NC balloon + GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 12 (11.4) | 10 (26.3) | 2 (3.1) | – |

|

DES, drug-eluting stent; NC, non-compliant; SC, semi-compliant; ST, stent thrombosis; STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. |

||||

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient inclusion in the study. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

OCT analysis

No complications related to the OCT technique were observed. Morphometric and stent–vessel wall interaction data are shown in table 2. A total of 24 834 cross-sections were evaluated, of which 1453 (5.8%) could not be analyzed because of abundant residual thrombus.

Table 2. Morphometric analysis and stent–vessel wall interaction according to type of stent thrombosis

| Variables | Acute ST (n = 17) | Subacute ST (n = 23) | Late ST (n = 13) | Very late ST (n = 52) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrombus | |||||

| Fr with thrombus per stent, % | 68.8 ± 24 | 61.7 ± 21 | 37.1 ± 27.9 | 42.6 ± 24.3 | < .001 |

| Maximum thrombus area, mm2 | 4.38 ± 1.72 | 3.12 ± 1.82 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 1.4 | < .001 |

| Maximum length, mm | 22.9 ± 30 | 15.35 ± 19 | 8.4 ± 5.8 | 7.9 ± 4.7 | < .001 |

| Malapposition | |||||

| Fr with malapposition per stent, % | 13.3 ± 14 | 9.3 ± 9 | 11.4 ± 11.5 | 2.3 ± 5.9 | < .001 |

| Maximum area, mm2 | 0.48 ± 0.54 | 0.61 ± 0.7 | 1.29 ± 1.5 | 0.42 ± 1.21 | < .001 |

| Maximum strut length, mm | 3.11 ± 3.99 | 1.92 ± 2.12 | 2.26 ± 2.3 | 0.6 ± 1.31 | < .001 |

| Stents with at least 1 Fr with malapposition, % | 13 (76.5) | 17 (73.9) | 10 (76.9) | 10 (19.2) | < .001 |

| Coverage | |||||

| Fr with uncovered struts, % | 88.2 ± 27.5 | 77.9 ± 30.6 | 21.3 ± 28.5 | 3.37 ± 11.42 | < .001 |

| Maximum length of uncovered struts, mm | 19.3 ± 11.6 | 16.1 ± 8.5 | 5.1 ± 8.6 | 1.6 ± 5.3 | < .001 |

| Stents with at least 1 uncovered Fr, % | 17 (100) | 22 (95.6) | 10 (76.9) | 15 (28.8) | < .001 |

| Neoatherosclerosis | |||||

| Fr with neoatherosclerosis per stent, n | 0 | 0 | 3.1 ± 2.9 | 41.1 ± 47.8 | < .001 |

| Stents with at least 1 Fr with neoatherosclerosis, n | 0 | 0 | 3 (23) | 78 | < .001 |

| Expansion | |||||

| Mean reference area, mm2 | 7.74 ± 2.15 | 5.76 ± 2.41 | 7.46 ± 2.29 | 6.19 ± 2.09 | .012 |

| Minimum stent area, mm2 | 6.98 ± 2.06 | 4.35 ± 1.53 | 6.09 ± 2.03 | 5.6 ± 1.89 | < .001 |

| Expansion index, % | 91.78 ± 21 | 86.9 ± 42.6 | 84 ± 19.9 | 95.21 ± 32.4 | 0.48 |

| Expansion index < 80%, n (%) | 6 (35.3) | 12 (52.1) | 5 (38.5) | 17 (33.3) | 0.1 |

|

Fr, frames; ST, stent thrombosis. |

|||||

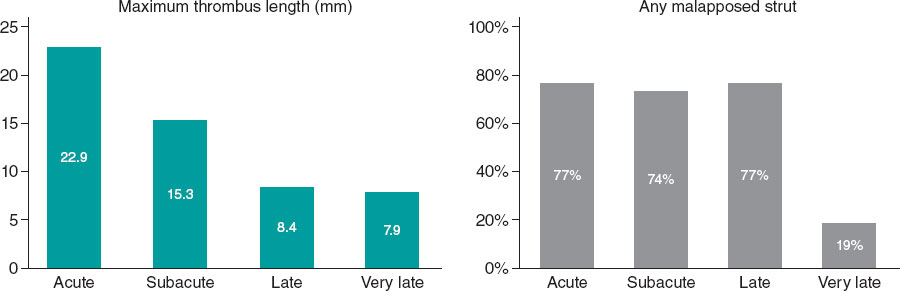

There were no differences in underexpansion rates based on the type of thrombosis, and only a minimum stent area < 4.5 mm2 was observed in subacute ST. The number of uncovered struts decreased significantly over time (although 30% of stents still exhibited uncovered struts at the 1-year follow-up), as did thrombus burden and malapposition (figure 2). Additionally, we analyzed these findings by stent type (table 3), showing that uncovered or malapposed struts were more frequent in drug-eluting stents than in bare-metal stents.

Table 3. Morphometric analysis according to stent type

| Variables | Bare-metal stent (n = 30) | First-generation DES (n = 14) | New-generation DES (n = 56) | Bioresorbable scaffold (n = 5) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Fr with uncovered struts | 29.4 ± 64 | 27.8 ± 87 | 130.6 ± 128.6 | 121.8 ± 89.4 | < .001 |

| Stents with at least 1 uncovered strut, % | 10 (33) | 6 (42) | 42 (75) | 5 (100) | < .001 |

| No. of frames with thrombus per stent | 82.3 ± 44 | 100.9 ± 51 | 134.4 ± 83.2 | 73.4 ± 59.7 | .022 |

| Stents with at least 1 malapposed strut, % | 6 (20) | 5 (35.7) | 36 (64.3) | 3 (60) | < .001 |

| Stents with expansion < 80%, % | 20.7 | 0.5 | 44.6 | 0.4 | .104 |

| Stents with neoatherosclerosis, % | 17 (56.7) | 7 (50) | 16 (28.6) | 0 | .013 |

|

DES, drug-eluting stent; Fr, frames. |

|||||

Figure 2. Morphometric findings over time.

Primary endpoint

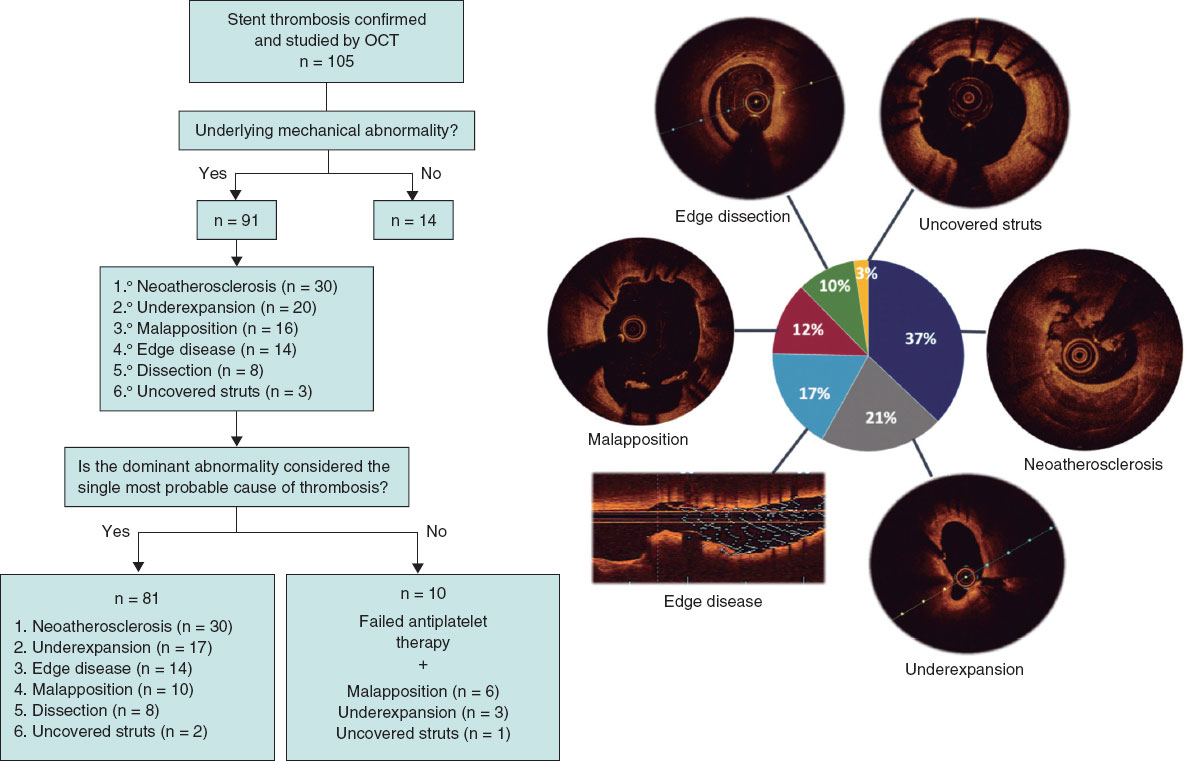

Underlying mechanical abnormalities were identified in 91 of 105 patients (86.7%). Of these, 10 patients also had documented nonadherence to antiplatelet therapy in the days preceding ST; therefore, a mechanical abnormality was considered the most likely single cause in 81 patients (77.1%). The global distribution of dominant findings is shown in figure 3, and representative examples of ST cases in figure 4.

Figure 3. Central illustration. Assignment of the dominant finding and most likely cause of stent thrombosis. OCT, optical coherence tomography.

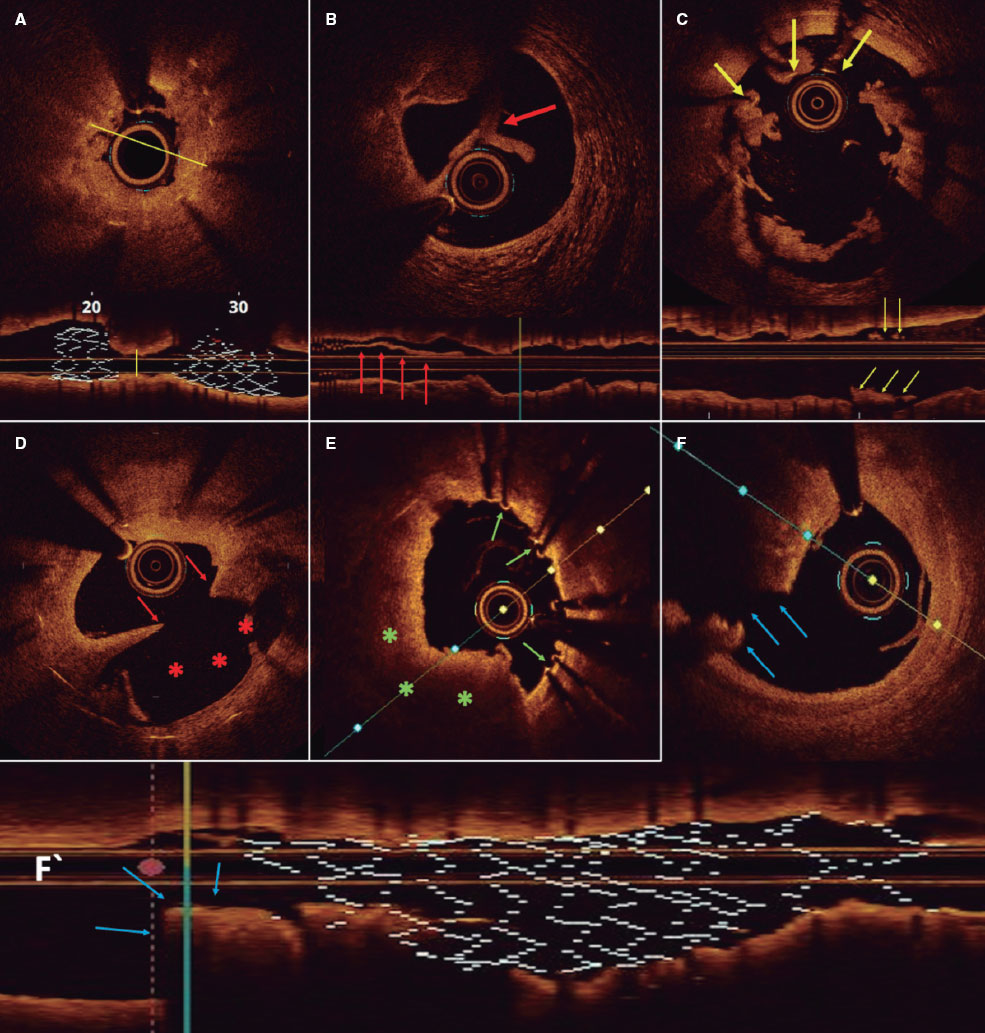

Figure 4. Representative optical coherence tomography findings. A: longitudinal and cross-sectional views of a stent with marked underexpansion (line indicates minimum diameter). B: stent-edge dissection. Arrow indicates separated tissue flap from the vessel wall. C: malapposition. Arrows indicate struts associated with thrombus that are not in contact with the vessel wall. D: neoatherosclerosis with plaque rupture. Arrows indicate intimal discontinuity, and asterisks show the evacuated plaque cavity. E: uncovered struts (arrows). F and F‘: cross-sectional and longitudinal views of a stent with distal edge disease and plaque rupture (arrows).

Representative optical coherence tomography findings. A: longitudinal and cross-sectional views of a stent with marked underexpansion (line indicates minimum diameter). B: stent-edge dissection. Arrow indicates separated tissue flap from the vessel wall. C: malapposition. Arrows indicate struts associated with thrombus that are not in contact with the vessel wall. D: neoatherosclerosis with plaque rupture. Arrows indicate intimal discontinuity, and asterisks show the evacuated plaque cavity. E: uncovered struts (arrows). F and F’: cross-sectional and longitudinal views of a stent with distal edge disease and plaque rupture (arrows).

The dominant finding varied significantly by ST timing (P < .001) (table 4). In acute ST, the most frequent result was no identifiable abnormality (41.2%), and the dominant finding was stent-edge dissection (23.5%); in subacute ST, it was underexpansion (47.8%); in late ST, malapposition; and in very late ST, neoatherosclerosis (52%). However, there were no significant differences by stent type (P = .07): in bare-metal and first-generation drug-eluting stents, the most common abnormality was neoatherosclerosis (46.7% and 35.7%, respectively), whereas in new-generation drug-eluting stents, underexpansion predominated (26.8%). In very late ST, neoatherosclerosis was the most common finding in both bare-metal and drug-eluting stents (56.7% vs 50%; P = .45), regardless of whether thrombosis occurred within 5 years or later after stent implantation. Five cases of bioresorbable scaffold thrombosis were recorded whose specific findings have already been reported previously.10

Table 4. Dominant findings according to timing of stent thrombosis and stent type

| Dominant finding | Acute ST (n = 17) | Subacute ST (n = 23) | Late ST (n = 13) | Very late ST (n = 52) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edge dissection | 4 (23.5) | 4 (17.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Underexpansion | 2 (11.8) | 11 (47.8) | 1 (7.7) | 6 (11.5) |

| Malapposition | 3 (17.6) | 3 (13.0) | 4 (30.8) | 6 (11.5) |

| Neoatherosclerosis | 0 | 0 | 3 (23.1) | 27 (52.0) |

| No finding | 7 (41.8) | 3 (13.0) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (5.7) |

| Edge disease | 1 (5.9) | 2 (8.7) | 2 (15.4) | 9 (17.3) |

| Uncovered struts | 0 | 0 | 2 (15.4) | 1 (2.0) |

| Dominant finding | Bare-metal stent (n = 30) | First-generation DES (n = 14) | New-generation DES (n = 56) | Bioresorbable scaffold (n = 5) |

| Edge dissection | 2 (6.7) | 0 | 5 (8.9) | 1 (20.0) |

| Underexpansion | 2 (6.7) | 2 (14.2) | 15 (26.8) | 1 (20.0) |

| Malapposition | 5 (16.7) | 3 (21.4) | 8 (14.3) | 0 |

| Neoatherosclerosis | 14 (46.7) | 5 (35.7) | 11 (19.6) | 0 |

| No finding | 1 (3.3) | 2 (14.3) | 9 (16.1) | 2 (40.0) |

| Edge disease | 6 (20.0) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (10.7) | 1 (20.0) |

| Uncovered struts | 0 | 1 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | 0 |

|

DES, drug-eluting stent; ST, stent thrombosis. |

||||

Neoatherosclerosis and plaque rupture

Neoatherosclerosis was identified in 40 patients, regardless of whether it was the dominant finding. There were no differences in baseline characteristics between patients with and without neoatherosclerosis, although those with neoatherosclerosis had larger minimum stent areas, smaller minimum lumen areas, and fewer uncovered and malapposed struts (table 1 of the supplementary data). Minimum lumen area was the only factor associated with a higher risk of neoatherosclerosis (odds ratio [OR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.16–0.75; P = .013).

Plaque rupture was reported in 16 patients with neoatherosclerosis. There were no differences in baseline characteristics or in the composition of neoatherosclerosis between patients with and without plaque rupture (table 2 of the supplementary data). Despite the limited sample size, minimum lumen area was identified as a protective factor against plaque rupture (OR, 0.22; 95%CI, 0.04–0.7; P = .035). The presence of neovessels or calcium inside the stent was not associated with plaque rupture, nor was stent type.

Clinical follow-up

The in-hospital mortality rate for the overall cohort was 9.2%, with no significant differences being reported between patients who did and did not undergo OCT (8.5% vs 11%; P = .7). The main predictors of mortality were chronic kidney disease (OR, 9.56; 95%CI, 2.28–41.14; P = .002) and Killip-Kimball class III/IV status (OR, 14.8; 95%CI, 3.38–79.6; P = .001).

A total of 28 composite endpoints were recorded at the follow-up (median, 2143 days [15–2906]). Event-free survival rates at 1 and 5 years were 83.3% and 73.1%, respectively. There were 13 deaths at the follow-up. Estimated survival rates were 96% and 86.7% at 1 and 5 years, respectively (figure 1 of the supplementary data).

DISCUSSION

ST remains a serious complication with a high mortality rate.11 Understanding its pathophysiology is essential for improving prevention, diagnosis, and eventually treatment.12 In this context, OCT provides crucial real-time information, allowing for much more precise diagnosis and individualized treatment.

This study represents the largest national series of ST cases evaluated with OCT. The main findings are 1) the use of OCT in the acute phase of ST is safe and feasible in experienced centers; 2) OCT identified mechanical abnormalities in 86.7% of ST cases; 3) the dominant finding varied according to the timing of ST (in acute ST, no mechanical abnormality was most common, while underexpansion predominated in subacute ST, malapposition in late ST, and neoatherosclerosis in very late ST); 4) OCT enabled treatment guidance based on the dominant finding and might reduce the need for additional stenting; and 5) in-hospital mortality rate was low (9.2%), with Killip-Kimball class IV and chronic kidney disease being the main predictors.

An adequate-quality OCT study was achieved in 74% of patients, which is a rate considerably higher than that reported by the main European registries.9,13 Although thrombus can limit visibility, image quality can be improved with thrombus aspiration or the use of catheter extension systems. Unlike other studies in which OCT was performed in a procedure separate from the index ST, our study conducted OCT during the acute event, representing a key methodological strength.

OCT demonstrated a remarkable ability to detect mechanical abnormalities (86.7%). In this setting, the information provided by angiography is insufficient. In the PESTO trial,13 angiography identified the cause of ST in only 12% of cases, whereas OCT did so in more than 90% of the cases. The CLI-OPCI trial14 was the first to demonstrate that OCT provides information on immediate stent outcomes not appreciable on angiography, prompting additional interventions in up to one-third of patients.

Although some findings are consistent with the PRESTIGE study,9 our analysis provides relevant nuances. In particular, in acute ST, most cases showed no evident mechanical abnormalities (unlike our preliminary results, in which malapposition predominated). This finding reinforces the role of antithrombotic treatment and prothrombotic states as key factors, supported by the greater thrombus burden observed in early vs late ST. Unlike previous studies, our results emphasize the utility of OCT not only in identifying mechanical causes but also in avoiding unnecessary interventions, thereby underscoring the importance of optimal medical therapy. In addition, in our study, uncovered struts were not considered a cause of acute or subacute ST, based on the assumption that no stent is covered by neointima within the first 30 days.

The association between acute malapposition and ST remains controversial.15-17 A possible explanation is that although malapposition is almost ubiquitous after stent implantation,18,19 its relationship with thrombosis is difficult to establish because of the low probability of a later event.

Underexpansion, however, is established as one of the most important predictors of ST. In the CLI-OPCI study,20 a minimum lumen area > 4.5 mm2 was identified as a threshold for discriminating events during follow-up. This cutoff value is not achievable in small vessels and does not apply to left main lesions. Relative expansion6,21 may thus be a more appropriate measure, although its superiority over absolute expansion in predicting events has not yet been established.

In late ST, malapposition was the most common finding. Most cases of nonsevere acute malapposition resolve during follow-up, although up to 30% may persist.18 One study22 reported substantially lower rates of malapposition (8%) than those observed in previous large registries,9,13 likely because the index implantation was image-guided; this also supported that 75% of cases represented acquired malapposition.

Neoatherosclerosis was detected in most late and very late ST, irrespective of stent type, unlike other studies in which it predominated in drug-eluting stents. This may be explained by the longer interval between implantation and thrombosis in bare-metal stents, which is consistent with the observation that follow-up duration is the most important predictor of neoatherosclerosis.23 The use of OCT avoided unnecessary new stenting in 48% of patients, a higher rate compared with other ST series without image guidance24 and even higher than in the PRESTIGE registry.9

Limitations

The present study has several limitations: 1) the absence of a control group precludes predictive evaluation of certain findings such as malapposition, and superiority of OCT over non–intracoronary image-guided interventions cannot be definitively established; 2) no core laboratory was used for OCT analysis, which may limit external reproducibility; 3) selection bias exists due to exclusion of the most severe patients and those with complex anatomy, which may account for favorable outcomes and could influence the prevalence of some mechanisms; 4) ST is a multifactorial process, and the dominant finding cannot be considered the definitive cause; 5) the presence of thrombus hampers evaluation of underlying structures; 6) the index stent implantation was not image-guided, preventing differentiation between acute and acquired malapposition; and 7) serial OCT studies were not performed in many patients, which means that correction of the detected abnormality could not be assessed.

CONCLUSIONS

OCT is a safe, feasible, and highly useful tool for the treatment of ST. It allows identification of the most likely cause of the event in most cases—which varies according to the timing of thrombosis—and enables individualized treatment by addressing the underlying abnormality.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This study was approved by Hospital Universitario de La Princesa Ethics Committee. All procedures conformed to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study followed the SAGER guidelines. Written informed consent for publication was obtained and archived.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence tools were used in the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors contributed equally to the conception, design, and analysis of the study, as well as to drafting and revising the manuscript. Furthermore, all authors approved the final version and are responsible for its content.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

F. Alfonso is Associate Editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ST is a rare but clinically significant complication, characterized by high mortality, recurrence, and a complex, multifactorial pathophysiology. A thorough understanding of its underlying mechanisms is essential to guide appropriate preventive and therapeutic strategies.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study is the largest national series of consecutive ST cases evaluated with OCT and demonstrates the ability of this imaging modality to detect underlying mechanical abnormalities potentially involved in the pathogenesis of this serious complication.

- Mechanical abnormalities associated with ST vary significantly according to timing of presentation.

- Improving stent implantation technique could reduce the rate of ST by addressing causes such as malapposition and underexpansion.

- The use of OCT during ST treatment allows procedures to be guided and optimized.

REFERENCES

1. Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Pache J, et al. Analysis of 14 Trials Comparing Sirolimus-Eluting Stents with Bare-Metal Stents. N Engl J Med. 2007;356: 1030-1039.

2. Alfonso F. The “Vulnerable“Stent. Why So Dreadful?J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2403-2406.

3. Park KW, Hwang SJ, Kwon DA, et al. Characteristics and predictors of drug-eluting stent thrombosis:Results from the multicenter Korea stent thrombosis (KoST) registry. Circ J. 2011;75:1626-1632.

4. Cuesta J, Rivero F, Bastante T, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Patients With Stent Thrombosis. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70: 1050-1058.

5. Prati F, Kodama T, Romagnoli E, et al. Suboptimal stent deployment is associated with subacute stent thrombosis:Optical coherence tomography insights from a multicenter matched study. From the CLI Foundation investigators:The CLI-THRO study. Am Heart J. 2015;169:249-256.

6. Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1:Guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3281-3300.

7. Alfonso F, Fernandez-Viña F, Medina M, Hernandez R. Neoatherosclerosis:The Missing Link Between Very Late Stent Thrombosis and Very Late In-Stent Restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:155.

8. Joner M, Koppara T, Byrne RA, et al. Neoatherosclerosis in Patients With Coronary Stent Thrombosis:Findings From Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging (A Report of the PRESTIGE Consortium). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:1340-1350.

9. Adriaenssens T, Joner M, Godschalk TC, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography Findings in Patients With Coronary Stent Thrombosis:A Report of the PRESTIGE Consortium (Prevention of Late Stent Thrombosis by an Interdisciplinary Global European Effort). Circulation. 2017;136: 1007-1021.

10. Cuesta J, García-Guimaraes M, Basante T, Rivero F, Antuña P, Alfonso F. Bioresorbable Vascular Scaffold Thrombosis:Clinical and Optical Coherence Tomography Findings. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2019;72:90-91.

11. la Torre-Hernández JM, Alfonso F, Hernández F, et al. Drug-Eluting Stent Thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:986-990.

12. Alfonso F, Dutary J, Paulo M, et al. Combined use of optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound imaging in patients undergoing coronary interventions for stent thrombosis. Heart. 2012;98:1213-1220.

13. Souteyrand G, Amabile N, Mangin L, et al. Mechanisms of stent thrombosis analysed by optical coherence tomography:insights from the national PESTO French registry. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:1208-1216.

14. Prati F, Di Vito L, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Angiography alone versus angiography plus optical coherence tomography to guide decision-making during percutaneous coronary intervention:the Centro per la Lotta contro l'Infarto-Optimisation of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) study. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:823-829.

15. Ng JCK, Lian SS, Zhong L, Collet C, Foin N, Ang HY. Stent malapposition generates stent thrombosis:Insights from a thrombosis model. Int J Cardiol. 2022;353:43-45.

16. Prati F, Romagnoli E, La Manna A, et al. Long-term consequences of optical coherence tomography findings during percutaneous coronary intervention:the Centro Per La Lotta Contro L'infarto – Optimization Of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (CLI-OPCI) LATE study. EuroIntervention. 2018;14:443-451.

17. Romagnoli E, Gatto L, La Manna A, et al. Role of residual acute stent malapposition in percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90:566-575.

18. Shimamura K, Kubo T, Akasaka T, et al. Outcomes of everolimus-eluting stent incomplete stent apposition:a serial optical coherence tomography analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;16:23-28.

19. Ali ZA, Maehara A, Généreux P, et al. Optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and with angiography to guide coronary stent implantation (ILUMIEN III:OPTIMIZE PCI):a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2618-2628.

20. Prati F, Romagnoli E, Burzotta F, et al. Clinical Impact of OCT Findings During PCI:The CLI-OPCI II Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:1297-1305.

21. Ali ZA, Landmesser U, Maehara A, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography– Guided versus Angiography-Guided PCI. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1466-1476.

22. Mori H, Sekimoto T, Arai T, et al. Mechanisms of Very Late Stent Thrombosis in Japanese Patients as Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography. Can J Cardiol. 2024;40:696-704.

23. Otsuka F, Byrne RA, Yahagi K, et al. Neoatherosclerosis:Overview of histopathologic findings and implications for intravascular imaging assessment. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:2147-2159.

24. Armstrong EJ, Feldman DN, Wang TY, et al. Clinical Presentation, Management, and Outcomes of Angiographically Documented Early, Late, and Very Late Stent Thrombosis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:131-140.

* Corresponding author.