ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) is increasingly used in complex percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI), particularly in cases of “balloon failure,” which includes both uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions. Although these 2 scenarios represent distinct technical and clinical challenges, they are usually evaluated using the same safety and efficacy endpoints. As a result, there is a lack of specific evidence on the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in each of these situations. Furthermore, the role of intracoronary imaging in optimizing ELCA use remains insufficiently defined.

Methods: This will be an investigator-initiated, multicenter, single-arm, open-label, prospective observational study. Patients with an indication for PCI and undilatable (non-compliant balloon dilatation < 80% at burst pressure) or uncrossable (uncrossable with a “small-profile balloon” with adequate support, left to the operator’s discretion) coronary artery lesions treated with ELCA will be included. Intravascular imaging will be highly advised and analyzed in a core laboratory. Device success, angiographical success, procedural success, clinical success and related complications will be evaluated. Patients will be postoperatively followed for 1 year and clinical events will be recorded.

Conclusions: The LUDICO study will be a multicentre, prospective study of ELCA therapy in uncrossable or undilatable coronary lesions. The study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA in these lesions as well as the clinical results at the 1 year follow-up in this setting. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT07206082).

Keywords: Percutaneous coronary intervention. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy. Intravascular imaging. Optical coherence tomography. Complex coronary intervention.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La aterectomía coronaria con láser de excímeros (ELCA) se utiliza cada vez más en intervenciones coronarias percutáneas (ICP) complejas, en particular en caso de «fallo del balón», que incluye tanto lesiones coronarias no cruzables como no dilatables. Aunque estos 2 escenarios representan desafíos técnicos y clínicos distintos, con frecuencia se han evaluado utilizando los mismos criterios de efectividad y seguridad. Como resultado, existe una falta de evidencia específica sobre la seguridad y la efectividad de la ELCA en cada una de estas situaciones. Además, el papel de la imagen intracoronaria en la optimización del uso de la ELCA sigue estando insuficientemente descrito.

Métodos: Se trata de un estudio observacional prospectivo, abierto, multicéntrico e iniciado por los investigadores. Se incluirán pacientes con indicación de ICP y lesiones coronarias no dilatables (dilatación con balón no distensible < 80% a presión de ruptura) o no cruzables (no cruzables con un balón de bajo perfil y adecuado soporte, a criterio del operador) tratados con ELCA. Se recomendará el uso de imagen intravascular, que se analizará en un laboratorio central. Se evaluarán el éxito del dispositivo, el éxito angiográfico, el éxito del procedimiento, el éxito clínico y las complicaciones asociadas. Se seguirá a los pacientes durante 1 año tras el procedimiento y se registrarán los eventos clínicos.

Conclusiones: El estudio LUDICO será un estudio prospectivo y multicéntrico sobre el uso de ELCA en lesiones coronarias no cruzables o no dilatables. Su objetivo es evaluar la efectividad y la seguridad de la ELCA en estas situaciones, así como los resultados clínicos durante un seguimiento de 1 año. (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT07206082).

Palabras clave: Intervención coronaria percutánea. Aterectomía coronaria con láser de excímeros. Imagen intravascular. Tomografía de coherencia óptica. Intervención coronaria compleja.

Abbreviations

ELCA: excimer laser coronary angioplasty. IVUS: intravascular ultrasound. OCT: optical coherence tomography. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. RA: rotational atherectomy.

INTRODUCTION

Excimer laser coronary atherectomy (ELCA) has been applied since the 1980s in multiple anatomical and clinical settings, with several studies supporting its safety and efficacy profile.1,2 Common indications include in-stent restenoses, stent underexpansion, calcified coronary lesions, saphenous vein graft stenoses, thrombotic lesions, bifurcations, and chronic total coronary occlusions.3-14 In practice, however, ELCA is predominantly used in the setting of balloon failure–specifically uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions. However, historical studies have typically applied a uniform definition of device success across both lesion types, potentially overlooking important nuances that could influence outcomes and therapeutic decision-making.

Furthermore, despite growing recognition of the value of intracoronary imaging in optimizing complex percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),15 prior ELCA studies have largely underutilized this tool, limiting insight into the mechanisms of success or failure in balloon-resistant lesions.

The safety and efficacy profile of coronary laser in undilatable and uncrossable lesions (LUDICO) study is a real-world, observational study designed to evaluate the use of ELCA specifically in cases of balloon failure. The study has 2 primary objectives: a) to refine the definition of ELCA procedural success based on the type of balloon failure encountered—distinguishing between uncrossable and undilatable lesions—, and b) to emphasize the critical role of intracoronary imaging in guiding ELCA and interpreting procedural outcomes. By addressing these critical gaps, the study aims to provide a more precise and and clinically meaningful framework for the contemporary use of ELCA in complex coronary interventions.

METHODS

Study design and population

This is a prospective, multicentre, observational study including consecutive patients undergoing ELCA in undilatable (expansion < 80% of the distal vessel diameter after inflation of a 1:1 non-compliant balloon at 18 atm) and uncrossable coronary artery lesions (uncrossable after using a small-profile balloon with adequate support left to the operator’s discretion). At least 15 national centers will be contacted to participate in the study. Participant centers will be required to have experience with ELCA and complex PCI, with a minimum of > 5 prior ELCA cases performed. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in table 1. This study was conducted in full compliance with the STROBE guidelines for observational studies.16 The study protocol was registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT07206082).

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Patients > 18 | Patients with known allergies to ASA, clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor |

| Patients with either stable coronary artery disease or acute coronary syndromes as the clinical presentation | Patients unable to provide informed consent, either personally or through a legal representative |

| Patients with severe coronary lesions (> 70% by visual estimation) in native vessels or coronary bypass grafts | Patients with clinical or hemodynamic instability defined as: sustained hypotension (SBP ≤ 90 mmHg for ≥ 30 minutes or use of pharmacological, or mechanical support to maintain an SBP ≥ 90 mmHg) or evidence of end‐organ hypoperfusion including urine output of < 30 mL/h, cool extremities, altered mental status, or serum lactate > 2.0 mmol/L |

| “Uncrossable” coronary lesions (eg, lesions that cannot be crossed with a 0.7:1 balloon after successful guidewire passage) or “Undilatable” lesions (eg, those in which balloon dilation with a 1:1 non-compliant balloon at 18 atm results in < 80% expansion relative to the distal reference vessel diameter; this group includes both de novo lesions and in-stent restenosis or underexpanded stents) |

Patients with significant comorbidities and a life expectancy of < 1 year |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; SBP, systolic blood pressure. |

Procedure

PCI will be performed in accordance with current clinical practice guidelines on coronary revascularization.15,17

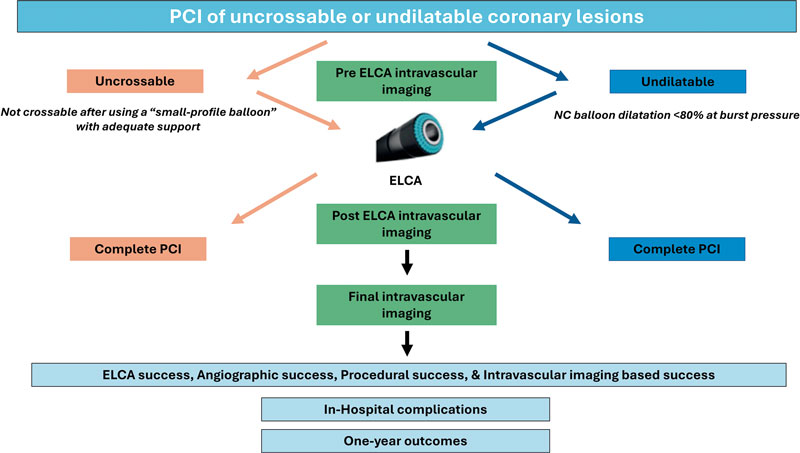

In uncrossable lesions, following successful guidewire passage and failed balloon crossing, ELCA will be performed (as described in the following section). PCI will be completed with optional predilatation at the operator’s discretion, followed by stenting or drugcoated balloon implantation. Intravascular imaging [preferably with optical coherence tomography (OCT)] will be recommended after laser application to characterize the lesion substrate and evaluate the effect of the laser and at the end of the procedure.

In undilatable lesions, if balloon dilation is inadequate, an initial intracoronary imaging assessment will be conducted. Afterwards, laser atherectomy will be performed, followed by a second intracoronary imaging assessment to evaluate the effects of ELCA on the lesion. PCI will, then, be completed with balloon dilation and stenting or drug-coated balloon implantation, at the operator’s discretion. A third intracoronary imaging pullback will be performed to assess the final procedural outcome (figure 1).

Figure 1. Central illustration. LUDICO study flowchart. ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; NC, non-compliant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Laser atherectomy technique

ELCA procedure will be performed using the Spectranetics CVX300 (Spectranetics, United States) and the latest generation Philips Laser System Excimer (Philips, United States) System, which is based on pulsed xenon‐chlorine laser catheters capable of delivering excimer energy (wavelength, 308 nm; pulse length, 185 ns) from 30 mJ/mm2 to 80 mJ/mm2 (fluencies) at pulse repetition rates of 25 Hz to 80 Hz.

The ELCA technique will be performed according to current recommendations.18 The choice of laser catheter size will be left to the operator’s discretion, selecting among the available rapid-exchange concentric probes (0.9 mm, 1.4 mm, 1.7 mm, or 2.0 mm). The selection of fluence, and repetition rate will be left to the operator’s discretion. A saline infusion technique will be recommended, although application of laser with blood or contrast will be recommended in resistant lesions. In the event of unsuccessful initial therapy, additional plaque modification techniques may be employed at the operator’s discretion and will be thoroughly recorded and described.

Clinical definitions and follow-up

Laser success will be defined differently for uncrossable and for undilatable lesions. For the former, laser success will be defined as the ability of the laser catheter to cross the lesion. Laser success will also be considered in cases where the laser catheter cannot cross the lesion but proximal laser application permits subsequent balloon crossing. For the latter, laser success will be defined as successful balloon dilation (sized 1:1 to the vessel diameter), with adequate expansion (> 80% in 2 orthogonal projections) following laser therapy without the need for other plaque modification technique.

Angiographic success will be defined as Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) grade-3 final flow and a percent diameter stenosis < 20%. Procedural success will be defined as angiographic success without severe procedural complications (death, coronary perforation, abrupt vessel closure, flow-limiting dissection). Intracoronary imaging-based success will be defined as a stent expansion ≥ 80% (OCT or intravascular ultrasound [IVUS]) or a minimal stent area (MSA) ≥ 4.5 mm2 in OCT or ≥ 5.5 mm2 in IVUS.

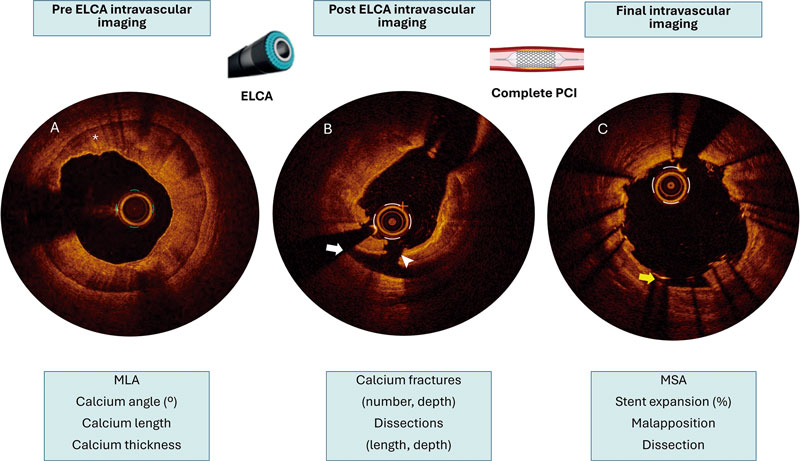

Intracoronary imaging

Intracoronary imaging will aim to describe the lesion characteristics and identify potential predictors of adequate stent expansion and procedural result. Therefore, intracoronary imaging will be highly recommended and the advised imaging modality will be OCT as its better spatial resolution vs IVUS allows better tissue characterization, plaque modification assessment and visualization of stent failure etiologies.19 A baseline intracoronary imaging evaluation is recommended, when possible, to describe the lesion characteristics and identify potential predictors of ELCA success or failure. Additionally, a second intracoronary imaging run is strongly advised immediately after laser therapy. This second run aims to describe the effect of ELCA in the coronary plaque. Evaluating and characterizing changes in the coronary plaque might help guide the optimal ELCA result and allow appropriate adjustment of therapy settings (fluence, repetition rate and infusion characteristics). Finally, a postoperative intravascular imaging run is strongly recommended once the final angiographic result is achieved. All intracoronary imaging data will be analyzed by a core laboratory. In the baseline intracoronary imaging run, lesion characteristics will be described as follows: minimum lumen area (MLA), minimum and maximum lumen diameter, lesion length, calcification angle, calcification thickness. In the post-ELCA imaging run the following parameters will be evaluated: MLA, number of calcium fractures and characteristics, presence of dissection, including its angle and length. In the final imaging run, MSA, stent apposition and dissections will be described. In both OCT and IVUS assessments, a dual-reference approach will be used: the proximal and distal reference lumen diameters will be identified, and MSA will be divided by each of these diameters separately. The final stent expansion index will be calculated as the mean of the 2 resulting values. Second, the tapered mode is only available in OCT: reference lumen profile is estimated based on the distal and proximal reference frame mean diameter and side branch mean diameter in between. With stent lengths > 50 mm, the dual method is preferred. With stent lengths < 50 mm the tapered method is often used. If the dual method is used, the stent expansion percentage of both segments will be recorded with the lower value of the two measurements used for analysis. The main variables to be evaluated by intravascular imaging are summarized and graphically shown in figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of the advised intracoronary imaging assessment in LUDICO study. A: baseline optical coherence tomography (OCT) image of a severely calcified lesion. The asterisk points to a calcium arc of 360° with a maximum thickness of 0.9 mm. B: OCT image after ELCA with contrast media. White arrow points to a dissection. The white arrowhead points to a deep calcium fracture. C: results after stenting. The yellow arrow points to a small area of malapposition. ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; MLA, minimal lumen area; MSA, minimal stent area; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Follow-up

Follow-up will be conducted at 3 different timeframes:a) after PCI; procedural success and complications will be thoroughly documented, and all patients will be evaluated for any postoperative events, such as chest pain, heart failure, bleeding, or ischemic events; b) at hospital discharge, documenting clinical status, complications and antiplatelet therapy; and c) 1 year after the index PCI; clinical events and antiplatelet therapy will be recorded.

The primary endpoint at the follow-up will be the composite endpoint of major adverse cardiovascular events, defined as the occurrence of cardiac death, target vessel-related acute myocardial infarction, target vessel revascularization, or definite/probable stent thrombosis. Secondary efficacy endpoints will include all-cause mortality, cardiac death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, target lesion revascularization, and target vessel revascularization. Secondary safety endpoints will include stroke and bleeding events (classified according to the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium [BARC] criteria). Endpoint definitions are shown in table 2.

Table 2. Procedural and clinical definitions

| Procedural definitions | |

|---|---|

| ELCA success | Uncrossable: defined as the ability of the laser catheter to cross the lesion or allow subsequent crossing with a predilatation balloon following laser application |

| Undilatable: defined as successful balloon dilation with adequate expansion following laser therapy | |

| Angiographic success | Defined adequate stent implantation and expansion, with residual stenosis < 20% and TIMI grade-3 flow, without crossover to another plaque modification technique |

| Procedural success | Angiographic success without severe procedural complications (death, coronary perforation, abrupt vessel closure, flow-limiting dissection) |

| Imaging based success | Defined as a stent expansion ≥ 80% (OCT or IVUS) or a MSA ≥ 4.5 mm2 in OCT or ≥ 5.5 mm2 in IVUS |

| Severely calcified coronary lesion | Angiographically: opacification in both sides of the artery before contrast administration |

| Intracoronary imaging: > 180° calcium arc or calcium thickness > 5 mm | |

| Clinical definitions | |

| MACE | Defined as the occurrence of cardiac death, target vessel-related acute MI, target vessel revascularization, or definite/probable stent thrombosis |

| Cardiac death | According to ARC definitions:31

|

| Non-fatal MI | Third universal definition of MI.32 In addition, procedure-related myocardial infarction—defined as a troponin elevation > 5 times the upper limit of normal in patients with previously normal troponin levels, or a ≥ 20% increase in patients with previously elevated troponin levels, along with electrocardiographic changes or new areas of myocardial necrosis detected by imaging—was included |

| Stent thrombosis | According to ARC criteria:

|

| Stroke | New neurological focal deficit with imaging confirmation and assessed by a neurologist |

| TLR | New coronary artery lesion in the previously treated coronary lesion including 5 mm proximal and distal to the implanted stent |

| TVR | New coronary artery lesion in the previously treated coronary vessel |

| Hemorrhage | According to BARC classification33 |

|

ARC, Academic Research Consortium; BARC, Bleeding Academic Research Consortium; ECG, electrocardiogram; ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; IVUS, intravascular ultrasound; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; MI, myocardial infarction; MSA, minimal stent area; OCT, optical coherence tomography; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; TIMI, Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; TLR, target lesion revascularization; TVR, target vessel revascularization. |

|

Sample size estimation

The planned sample size of 230 patients was determined based on expected device success rates reported in prior studies of ELCA for undilatable and uncrossable lesions. Assuming a conservative laser success rate of 80%, a cohort of 230 patients would yield a 95% confidence interval with a precision of approximately ± 5% (estimated range, 74.8%–85.2%), which is considered adequate for reliably estimating procedural efficacy in the routine clinical practice. Moreover, this sample size ensures sufficient statistical power to support multivariable analyses of predictors of both intraoperative and follow-up outcomes. With an anticipated 40–50 events, the study would allow the inclusion of approximately 4 to 5 covariates in multivariable regression models while maintaining acceptable model stability. Based on the expected procedural volume at each participant center and the required sample size, the recruitment period is 2 to 3 years.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables following a normal distribution will be expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Those not following a normal distribution will be reported using the median and minimum and maximum values. Qualitative variables will be expressed as absolute numbers and frequencies.

A significance level of 0.5 will be considered, and 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for the primary outcome variables. Normality of the data will be assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Based on the distribution, appropriate statistical tests will be applied to compare relevant variables. For comparisons of means, the Student t test for independent samples will be used, or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test in case of dichotomous qualitative variables. For comparisons involving non-dichotomous qualitative variables, ANOVA or the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test will be employed. For bivariate analysis of qualitative variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test will be used.

Multivariate analysis will be conducted using forward stepwise Cox regression analysis. Event-free survival curves will be constructed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Variables will be considered potential risk predictors in the multivariate model if they demonstrate a statistically significant association in the univariate analysis or show a trend toward significance. All statistical analyses will be conducted using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp, United States).

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines, including the most recent ICH E6 (R3) update. Before enrollment, patients or their legal representatives must be fully informed about the nature of the study and must provide written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each participant center.

DISCUSSION

The LUDICO study will be a multicenter study to assess the safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes of ELCA specifically in undilatable or uncrossable coronary artery lesions with lesion-specific endpoints and preferential use of intravascular imaging. We believe that this real-life approach will provide valuable insights into the 2 main clinical scenarios in which ELCA is currently used.

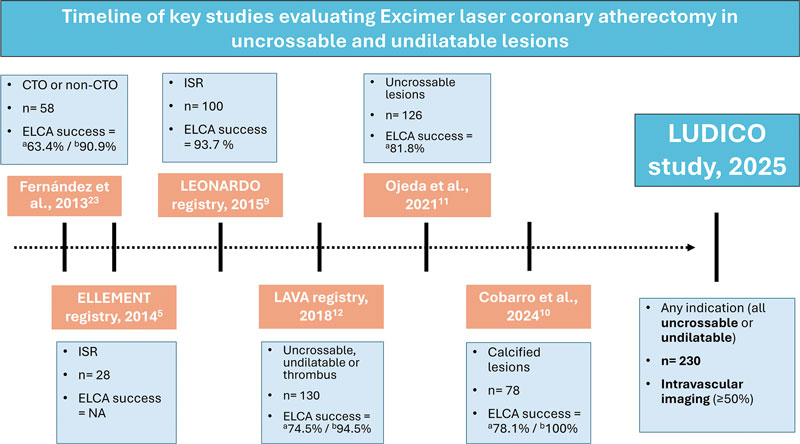

Three recent large registries confirmed ELCA to be a safe technique with an assumable rate of complications.20-22 However, these studies analyzed the overall procedural performance but failed to describe the lesion specific characteristics or intravascular imaging data. The findings of studies reporting balloon failure scenarios5,10-12,23,24 are summarized in figure 3. The LAVA multicenter registry set the main contemporary clinical indications for ELCA.12 This registry analysed ELCA use in 130 lesions and stratified them in 3 scenarios: uncrossable, undilatable and thrombotic. The LAVA and other studies analyzing ELCA has shown good performance of ELCA in balloon-failure, with lower rates of ELCA success in uncrossable vs undilatable lesions. However, one significant limitation is present in these studies: situations of balloonfailure include undilatable, uncrossable, or lesions with both components. In the routine clinical practice, these 2 situations are distinct; however, ELCA success has often been defined uniformly, potentially confounding the real efficacy of the device. Consequently, the LUDICO study aims to address this issue by specifically defining 2 endpoints based on the type of balloon failure, uncrossable or undilatable.

Figure 3. Timeline of key studies evaluating ELCA in uncrossable and undilatable lesions. CTO, chronic total coronary occlusion; ELCA, excimer laser coronary atherectomy; NA, not available; ISR, in-stent restenosis. a Uncrossable lesions. b Undilatable lesions.

Nonetheless, the definition of ELCA success in uncrossable lesions might be ambiguous in some cases. For instance, cases in which neither the ELCA catheter nor subsequent balloons are able to cross the lesion should not be considered procedurals failures if a microcatheter can subsequently cross and enable successful completion of the procedure using the RASER technique—a combination of ELCA and rotational atherectomy (RA). However, to simplify the endpoint, we have considered this situation a crossover to RA. In contrast, for undilatable lesions, the definition of ELCA success is less prone to interpretation; however, clearly defining what constitutes an undilatable lesion remains essential. This highlights the importance of a compliance test —that is, performing an initial balloon dilatation to objectively demonstrate that the lesion cannot be adequately expanded. Such a test is critical to identify lesions that are likely to benefit from plaque modification techniques, including ELCA. Arguably, the results of some randomized controlled trials in plaque modification devices (such as ECLIPSE25 using orbital atherectomy and ROLLERCOASTR7 using ELCA, intravascular lithotripsy and RA) may have been influenced by the absence of “compliance test”, potentially including coronary lesions in which plaque modification would not have been necessary after balloon testing, thereby reducing the differences across groups. Additionally, the recent CRATER trial showed that a total of 20.9% of patients in bailout RA group required crossover to RA because of balloon failure,26 which highlights the high frequency of this situation and underscores the importance of its prompt identification to select the most appropriate plaque modification technique such as ELCA.

RA is the most extensively studied strategy for managing uncrossable coronary lesions, supported by wide clinical experience and robust evidence.7,26,27 However, RA presents important limitations in specific scenarios where ELCA may offer clear advantages —such as in-stent restenosis or bifurcation lesions requiring side branch protection—given the risk of scaffold damage or distal embolization of debris.28 Orbital atherectomy, although less studied in uncrossable lesions,29,30 shares similar drawbacks due to its ablative mechanism. By contrast, ELCA is compatible with 6-Fr catheters, can be used over any standard guidewire, and has a less demanding learning curve.18 Of note, while RA demonstrates limited efficacy against deep calcium, ELCA can affect both superficial and deep calcification.4 Collectively, these features position ELCA as a uniquely valuable tool among plaque-modification techniques. Its capacity to safely treat in-stent restenosis, thrombotic lesions, uncrossable lesions, and bifurcations requiring side branch protection underscores advantages not readily attainable with RA or orbital atherectomy, thereby reinforcing ELCA as a superior alternative in selected complex PCI scenarios.

In conclusion, the use of intravascular imaging has been limited in most of the studies that have evaluated ELCA in balloon-failure, particularly those focused on uncrossable lesions. Additionally, none of these studies have described the findings of intravascular imaging before and after ELCA and identified potential predictors of success. In fact, the effect of ELCA in intravascular imaging remains an open question as there is a paucity of studies that have evaluated it and have been limited to in-stent restenosis.4 Therefore, one of the aims of the LUDICO study is to evaluate the effects of ELCA by intravascular imaging (preferably by OCT, due to its better spatial resolution) and identify potential predictors of ELCA success or failure and its effect on the coronary plaque. We hypothesize that recognizing potential predictors in intravascular imaging could help operators guide the procedures and identify the anatomical characteristics that best predict a favourable outcome with ELCA, thereby optimizing patient selection and procedural planning.

Limitations

First, this multicentre prospective study will be conducted in a single country, which may limit the generalizability of its findings to other settings. However, these high-volume centres, with wide experience in complex PCI comply with the international recommendations and their practice is comparable to other similar centres. Second, because of to the nonblinded study design, selection bias may have occurred, whereby certain lesions, such as extremely calcified or highly complex, were preferentially treated with alternative techniques or revascularization strategies. Additionally, there will not be a control group to assess the efficacy of the ELCA therapy vs other therapies. Finally, although intracoronary imaging will be highly recommended, we foresee that the baseline evaluation will be limited to just a few cases. In fact, by definition, uncrossable lesions will rarely have a baseline evaluation. Besides, in the event of the patient having kidney disease, OCT runs could be avoided, conducting to less OCT runs, or even to the absence of intravascular imaging.

CONCLUSIONS

The LUDICO study will be a multicenter, prospective study of ELCA therapy in uncrossable or undilatable coronary artery lesions with specific success definitions for each indication. The study aims to evaluate the safety and efficacy profile of ELCA and the clinical outcomes during the follow-up. The OCT evaluation will provide insights into the effect of ELCA in this subset of coronary lesions.

FUNDING

The LUDICO study was supported by a non-restricted grant from Biomenco.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The study was conducted in full compliance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained (institutional approval number: 5502), and all participants gave their written informed consent prior to enrolment. The confidentiality and anonymity of participants were strictly preserved throughout the study. Sex and gender considerations were addressed following the recommendations of the SAGER guidelines to ensure accurate and equitable reporting.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence assisted technologies were used exclusively to support language editing and improvement of style. No artificial intelligence tools were employed to generate, analyse, or interpret the data. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity, accuracy, and originality of the manuscript content.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

A. Jurado-Román and J. Zubiaur contributed to the study equally and share first authorship. A. Jurado-Román is responsible of the study conception and design. J. Zubiaur, A. Jurado-Román, and M. Basile were involved in the draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

R. Moreno is associate editor of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript has been followed; moreover, he has received consulting fees and honoraria/speaker fees from Abbott vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Terumo, and Biotronik. A. Jurado-Román reported receiving consulting fees from Boston Scientific and Philips; honoraria/speaker fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Shockwave Medical, World Medica, and Philips; and serves as a proctor for Abbott, Boston Scientific, World Medica, and Philips. G. Galeote has received honoraria/speaker fees from Meril, Boston Scientific, Abbott SMT, and Biomenco. A. Gonzálvez-García has received honoraria from Abbott. J. Suárez de Lezo has received honoraria/ speaker fees from Abbott and Philips. F. Hidalgo has received honoraria/speaker fees from Philips. M. Basile reported receiving consulting fees and speaking fees from Iberhospitex. B. Garcia del Blanco disclosed his role as a proctor for Edwards Lifescienses and his participation on the Advisory Board of Iberhospitex. All other authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- ELCA has demonstrated its usefulness across several challenging lesion subsets, including in-stent restenosis, stent underexpansion, calcified plaques, saphenous vein graft disease, thrombotic lesions, bifurcations, and chronic total coronary occlusions.

- However, in real-world practice, its main indication remains balloon failure, particularly in lesions that are either uncrossable or undilatable.

- Despite this, most earlier studies applied a uniform definition of device success for these distinct scenarios, potentially missing clinically relevant nuances that may affect outcomes and guide treatment strategies.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The LUDICO study is designed as a multicenter investigation to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and clinical outcomes of ELCA specifically in undilatable or uncrossable coronary artery lesions, incorporating individualized endpoints for each subset and emphasizing the use of intravascular imaging.

- This real-world strategy is expected to yield meaningful insights into the 2 primary clinical situations in which ELCA is currently employed: uncrossable and undilatable coronary artery lesions.

REFERENCES

1. Choy DS. History of lasers in medicine. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;36 Suppl 2:114–117.

2. Köster R, Kähler J, Brockhoff C, Münzel T, Meinertz T. Laser coronary angioplasty: history, present and future. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2002;2:197–207.

3. Bilodeau L, Fretz EB, Taeymans Y, Koolen J, Taylor K, Hilton DJ. Novel use of a high-energy excimer laser catheter for calcified and complex coronary artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2004;62:155–161.

4. Lee T, Shlofmitz RA, Song L, et al. The effectiveness of excimer laser angioplasty to treat coronary in-stent restenosis with peri-stent calcium as assessed by optical coherence tomography. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:e279–288.

5. Latib A, Takagi K, Chizzola G, et al. Excimer Laser LEsion Modification to Expand Non-dilatable sTents: The ELLEMENT Registry. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2014;15:8–12.

6. Dörr M, Vogelgesang D, Hummel A, et al. Excimer laser thrombus elimination for prevention of distal embolization and no-reflow in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: results from the randomized LaserAMI study. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116:20–26.

7. Jurado-Román A, Gómez MA, Rivero-Santana B, et al. Rotational Atherectomy, Lithotripsy, or Laser for Calcified Coronary Stenosis. JACC: Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18:606–618.

8. Giugliano GR, Falcone MW, Mego D, et al. A prospective multicenter registry of laser therapy for degenerated saphenous vein graft stenosis: the COronary graft Results following Atherectomy with Laser (CORAL) trial. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:84–89.

9. Ambrosini V, Sorropago G, Laurenzano E, et al. Early outcome of high energy Laser (Excimer) facilitated coronary angioplasty ON hARD and complex calcified and balloOn-resistant coronary lesions: LEONARDO Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:141–146.

10. Cobarro L, Jurado-Román A, Tébar-Márquez D, et al. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy in severely calcified lesions: time to bust the myth. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;6:33–40.

11. Ojeda S, Azzalini L, Suárez de Lezo J, et al. Excimer laser coronary atherectomy for uncrossable coronary lesions. A multicenter registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:1241–1249.

12. Karacsonyi M, Armstrong EJ, Huu Tam D, et al. Contemporary Use of Laser During Percutaneous Coronary Interventions: Insights from the Laser Veterans Affairs (LAVA) Multicenter Registry. J Invasive Cardiol. 2018;30:195–201.

13. Tomasello SD, Rochira C, Mazzapicchi A, et al. Clinical Outcomes of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Using Excimer Laser Coronary Atherectomy for Complex Coronary Lesions: The ACCELERATE Registry. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:1630–1638.

14. Basile M, Gómez-Menchero A, Rivero-Santana B, et al. Rotational Atherectomy, Lithotripsy, or Laser for Calcified Coronary Stenosis: One-Year Outcomes From the ROLLER COASTER-EPIC22 Trial. Cath Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:702–710.

15. Vrints C, Felicita Andreotti F, Koskinas KC, et al. 2024 ESC Guidelines for the management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:3415–3537.

16. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–S34.

17. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2024;13:55–161.

18. Rawlins J, Din JN, Talwar S, O’Kane P. Coronary Intervention with the Excimer Laser: Review of the Technology and Outcome Data. Interv Cardiol. 2016;11:27–32.

19. Nagaraja V, Kalra A, Puri R. When to use intravascular ultrasound or optical coherence tomography during percutaneous coronary intervention? Cardiovasc Diag Ther. 2020;10:1429444–1421444.

20. Sintek M, Coverstone E, Bach R, et al. Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty in Coronary Lesions: Use and Safety From the NCDR/CATH PCI Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e010061.

21. Protty MB, Gallagher S, Farooq V, et al. Combined use of rotational and excimer lASER coronary atherectomy (RASER) during complex coronary angioplasty—An analysis of cases (2006–2016) from the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society database. Cath Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;97:E911–E918.

22. Hinton J, Tuffs C, Varma R, et al. An analysis of long-term clinical outcome following the use of excimer laser coronary atherectomy in a large UK PCI center. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;104:27–33.

23. Fernandez JP, Hobson AR, McKenzie D, et al. Beyond the balloon: excimer coronary laser atherectomy used alone or in combination with rotational atherectomy in the treatment of chronic total occlusions, non-crossable and non-expansible coronary lesions. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:243–250.

24. Ambrosini V, Sorropago G, Laurenzano E, et al. Early outcome of high energy Laser (Excimer) facilitated coronary angioplasty ON hARD and complex calcified and balloOn-resistant coronary lesions: LEONARDO Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:141–146.

25. Kirtane AJ, Généreux P, Lewis B, et al. Orbital atherectomy versus balloon angioplasty before drug-eluting stent implantation in severely calcified lesions eligible for both treatment strategies (ECLIPSE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2025;405:1240–1251.

26. Galeote G, Zubiaur J, Jurado-Román A, et al. Coronary Rotational Atherectomy Elective Versus Bailout in Patients With Severely Calcified Lesions and Chronic Renal Failure (CRATER) Trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;106:1702–1712.

27. Abdel-Wahab M, Toelg R, Byrne RA, et al. High-Speed Rotational Atherectomy Versus Modified Balloons Prior to Drug-Eluting Stent Implantation in Severely Calcified Coronary Lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e007415.

28. Rivero-Santana B, Galán C, Pérez-Martínez C, et al. ELLIS Study: Comparative Analysis of Excimer Laser Coronary Angioplasty and Intravascular Lithotripsy on Drug-Eluting Stent as Assessed by Scanning Electron Microscopy. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:e014505.

29. Helal A, Ehtisham J, Shaukat N. Overcoming Uncrossable Calcified RCA Using Orbital Atherectomy After Failure of Rotational Atherectomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;105:1265–1268.

30. Bayón J, Mori-Junco RA, Jusková M, Abellas-Sequeiros M, González-Juanatey C. Feasibility and safety of orbital atherectomy in uncrossable lesions. REC: Interv Cardiol. 2025;7:269–271.

31. Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, et al. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344–2351.

32. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2551–2567.

33. Mehran R, Rao SV, Bhatt DL, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials: a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736–2747.