ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Although acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains a leading cause of death in Mexico, the impact of out-of-hours presentation on mortality remains understudied. The aim of this study was to evaluate the association between out-of-hours admissions (nights, weekends, holidays) and 30-day mortality in patients with AMI in Mexican hospitals, with a focus on the role of catheterization laboratories (cath lab).

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cohort study to analyze emergency admissions from December 2014 through August 2023. Admissions were classified as out-of-hours or during-hours and were stratified by hospital type (with or without cath lab). Cox regression models adjusted for sociodemographic, health, and temporal variables were used to analyze mortality risks.

Results: The study included a total of 29 131 cases: 4515 in percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)-capable centers (group 1) and 24 616 in non-PCI-capable centers (group 2). Admissions outside regular hours accounted for 46.7% in group 1 and 53.6% in group 2. Adjusted analysis showed that although the presence of a cath lab was protective (HR, 0.25; 95%CI, 0.23-0.28), admissions outside regular hours increased the risk of mortality in both groups (group 1: HR, 1.25; 95%CI, 1.04-1.50; group 2: HR, 1.16; 95%CI, 1.11-1.22). Although overnight shifts increased the risk of death in both groups, weekends and holidays increased such risk only in non-PCI-capable centers.

Conclusions: Out-of-hours admissions were associated with higher mortality, and unlike in developed countries, the presence of a cath lab did not improve out-of-hours outcomes.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction. Out-of-hours. Mexico.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El infarto agudo de miocardio (IAM) sigue siendo una causa principal de muerte en México, pero el impacto de su presentación fuera de horario sobre la mortalidad está poco investigado. El objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar la asociación entre las admisiones fuera de horario (noches, fines de semana y festivos) y la mortalidad a 30 días en pacientes con IAM en hospitales mexicanos, con énfasis en el papel de las salas de hemodinámica (SH).

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio de cohorte retrospectivo que analizó las admisiones en urgencias desde diciembre de 2014 hasta agosto de 2023. Las admisiones se clasificaron como fuera o dentro de horario, y se estratificaron según el tipo de hospital (con o sin SH). Se emplearon modelos de regresión de Cox ajustados por variables sociodemográficas, de salud y temporales para analizar el riesgo de mortalidad.

Resultados: El estudio incluyó 29.131 casos: 4.515 en hospitales con SH (grupo 1) y 24.616 en hospitales sin esta infraestructura (grupo 2). Las admisiones fuera de horario representaron el 46,7% en el grupo 1 y el 53,6% en el grupo 2. El análisis ajustado mostró que, aunque la presencia de una SH fue protectora (HR = 0,25; IC95%, 0,23-0,28), las admisiones fuera de horario aumentaron el riesgo de mortalidad en ambos grupos (grupo 1: HR = 1.25; IC95%, 1,04-1,50; grupo 2: HR = 1,16; IC95%, 1,11-1,22). Los turnos nocturnos también incrementaron el riesgo de muerte en ambos grupos, pero los fines de semana y festivos solo lo hicieron en los hospitales sin SH.

Conclusiones: Las admisiones fuera de horario se asociaron con mayor mortalidad y, a diferencia de los países desarrollados, la presencia de una SH no mejoró los resultados fuera de horario.

Palabras clave: Infarto agudo de miocardio. Fuera de horario. México.

Abbreviations

AMI: acute myocardial infarction. Cath lab: catetherization laboratory. PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, despite advances in prevention and treatment.1-3 Evidence suggests that patients with AMI admitted outside working hours–nights, weekends, and holidays–experience worse outcomes,4-6 likely due to treatment delays,7 limited specialist availability, and operational constraints.4,8,9 While this association is well-documented in high-income settings, its impact in low- and middle-income countries such as Mexico, where health care resources are often constrained, remains less understood.10-12

Among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, Mexico reports the highest AMI mortality rate (23.7%), far exceeding the OECD average of 7%.3,12 Throughout the past century, the Mexican public health system has evolved from fragmentation to institutional organization, with key institutions such as the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) (est. 1943) and the Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers or Civil Service Social Security and Services Institute (ISSSTE) serving formal and public-sector workers, respectively.13,14 To address coverage gaps for the uninsured, programs such as Seguro Popular (2003), Institute of Health for Welfare (INSABI) (2020), and IMSS-BIENESTAR (2023) were established. In recent years, more than 53 million uninsured individuals, about 42% of the population, receive care through the Mexican Ministry of Health (SSA) across nearly 12 000 health centers and more than 680 hospitals.13

Despite system reforms, the management of AMI in Mexico remains hindered by limited access to specialized services, fragmented insurance coverage, and an underperforming emergency response system. These issues, exacerbated by socioeconomic disparities and insufficient preventive care, contribute to delays and reduced quality of treatment.15,16 The main aim of the current study was to evaluate the association between out-of-hours presentation and 30-day AMI-related mortality in Mexican emergency departments.

METHODS

Study design, guidelines, and data source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in full compliance with the Guidelines for Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE).17 The present study used information from the public database of emergency department admissions from December 2014 through August 2023 in Mexico, published and validated by the General Directorate of Health (DGIS).18 This database compiles anonymous information from the SSA hospital registry (Seguro Popular/INSABI/IMSS-BIENESTAR programs) nationwide. Additional information on individual treatments (eg, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], thrombolysis, or door-to-balloon time), patient comorbidities, and delays in patient arrival was not available in the database.

Participants and sample size

The study included cases diagnosed with AMI (International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10, I21.0 to I21.9]), with lengths of stay of ≤ 30 days, classified as a qualified emergency, aged ≥ 18 years, and treated in a SSA hospital. Cases without complete information or not treated in the emergency department (referred to another health care unit, voluntarily discharged, or referred to outpatient care) were excluded from the analysis.

Definition of predictors and outcome

Sociodemographic (sex and age), time-related variables (admission and discharge dates), health care-related variables (type of emergency, discharge status, bed type, and AMI type according to ICD-10), and catheterization laboratories (cath labs) characteristics were collected. Several variables were grouped for analysis, including region of residence, death (yes/no), and length of stay (admission-to-discharge interval). The main predictor, out-of-hours, was defined as admissions during overnight shifts (19:00-6:59 h), weekends, or official holidays (per Article 74 of the Mexican Federal Labor Law).19 Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic (from 23 March 2020 to 9 May 2023)20 was considered. Hospitals were classified as PCI-capable and non-PCI-capable centers based on the SSA equipment database; and accurate and up-to-date information on PCI-capable centers was obtained; detailed definitions are provided in table S1.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages. The primary sample was divided into 2 groups to observe the differences between PCI-capable and non-PCI-capable centers, and all analyses were systematically performed in each group. The chi-square and Student t tests evaluated the difference between the out-hours and on-hours groups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed with proportional hazards adjusted for age, sex, year of admission, type of emergency, type of bed, territorial regions, type of AMI, admission during the COVID-19 pandemic, and characteristics of the cath lab. Moreover, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed to estimate and visualize the cumulative mortality rate according to out-of-hours admission components. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Confidence intervals (CI) were set at 95% (95%CI). Descriptive and analytical methods were performed in SPSS, version 25.0 (IBM, United States) and R software version 4.2.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria).

Ethical considerations

The study was based on data from the public emergency income database published by the DGIS.4 Accordingly, the confidentiality of the subjects is governed by the Mexican standard NOM-012-SSA3-2012,21 and the study is classified as risk-free research based on the principles of the General Law of Research for Health.22 The research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Women’s Hospital, SSA (No. 202403-47).

RESULTS

General characteristics

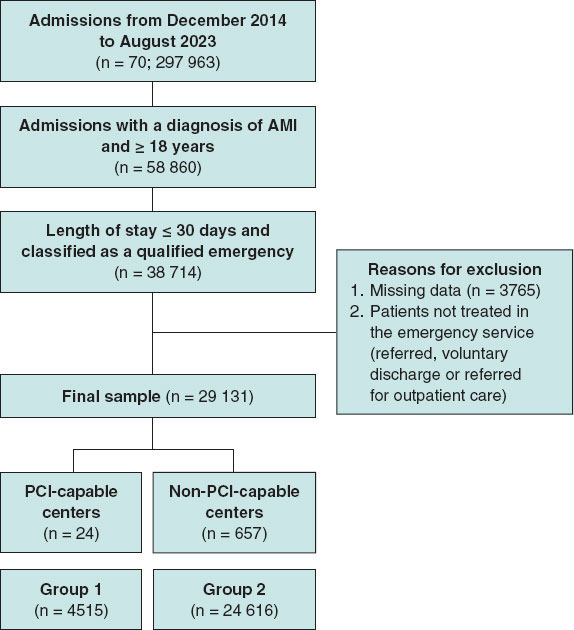

The final dataset included a total of 29 131 cases: 4515 from PCI-capable centers (group 1) and 24 616 from non-PCI-capable centers (group 2) (figure 1). Out-of-hours admissions accounted for 46.7% in group 1 and 53.6% in group 2, with night admissions being the most frequent and holiday admissions the least common (table S2). Among PCI-capable centers, 32.2% provided nightshift coverage, while 53.1% offered weekend availability. Out-of-hours admissions were associated with a higher proportion of male patients, longer lengths of stay, greater use of shock beds, higher mortality, more pronounced regional differences, and a greater impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (table S3). Moreover, in PCI-capable centers, out-of-hours admissions were associated with a lower daily average number of procedures and fewer professionals per shift (table S4).

Figure 1. Flowchart of filtering process. Patients with AMI (ICD-10 I21.0-I21.9), aged ≥ 18 years, hospitalized ≤ 30 days in Ministry of Health (SSA) emergency services were included. Cases with incomplete data or not treated in emergency care were excluded. The final cohort was categorized as PCI-capable and non-PCI-capable centers, identified through percutaneous coronary intervention or cardiac catheterization records. AMI, acute myocardial infarction; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

Association between out-of-hours care and the risk of death

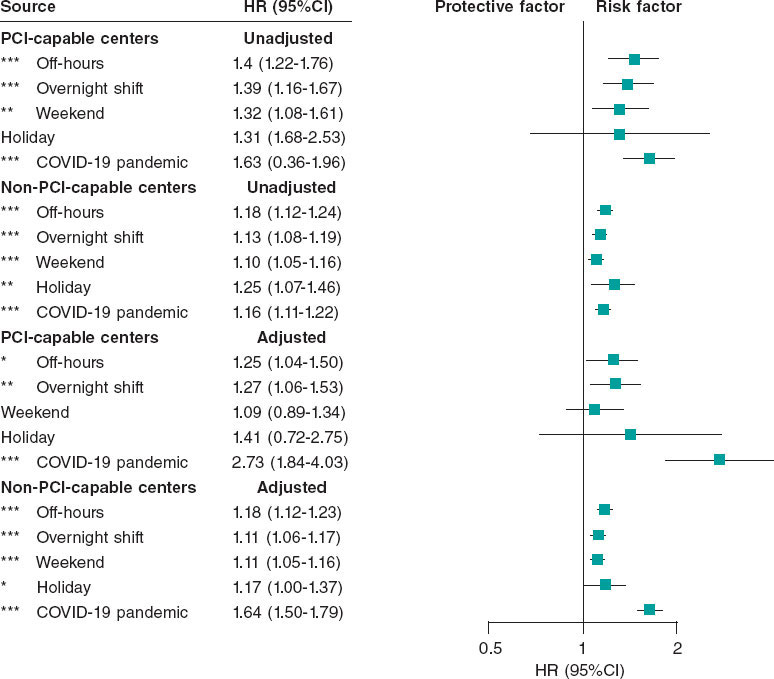

Univariate analysis showed that the presence of a cath lab was protective (HR, 0.22; 95%CI, 0.204-0.246). Out-of-hours, overnight shifts, weekend admissions, and the COVID-19 pandemic were associated with higher mortality in both groups. The risks from out-of-hours (HR, 1.46; 95%CI, 1.21-1.73 vs HR, 1.18; 95%CI, 1.11-1.23) and night-shift admissions (HR, 1.18; 95%CI, 1.12-1.23 vs HR, 1.13; 95%CI, 1.08-1.18) were more pronounced in PCI-capable centers, and holidays increased mortality only in non-PCI-capable centers (HR, 1.21; 95%CI, 1.03-1.41) (figure 2). Among cath lab characteristics, higher mean procedure volume (HR, 0.888; 95%CI, 0.840-0.938), greater staffing (HR, 0.800; 95%CI, 0.760-0.842), and availability during afternoon (HR, 0.515; 95%CI, 0.427-0.620), night (HR, 0.290; 95%CI, 0.233-0.361), and weekend shifts (HR, 0.317; 95%CI, 0.264-0.380) were associated with reduced mortality.

Figure 2. Mortality risk associated with out-of-hours admissions for acute myocardial infarction: analysis stratified by hospital type (PCI-capable and non-PCI- capable centers). The graph shows results from unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression models. Adjustments included age, sex, emergency type, bed type, region, year of admission, AMI type, and COVID-19 period. For PCI-capable centers, additional adjustments were made for cath lab availability by shift, angiography type, and number of specialists per shift. Points represent mortality HRs with horizontal lines for 95%CI. Results are shown separately for PCI-capable and non-PCI-capable centers. HR > 1 indicates increased mortality risk; HR < 1 indicates reduced risk. *P < .05; ** P < .01; *** P < .001. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; HR, hazard ratio; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

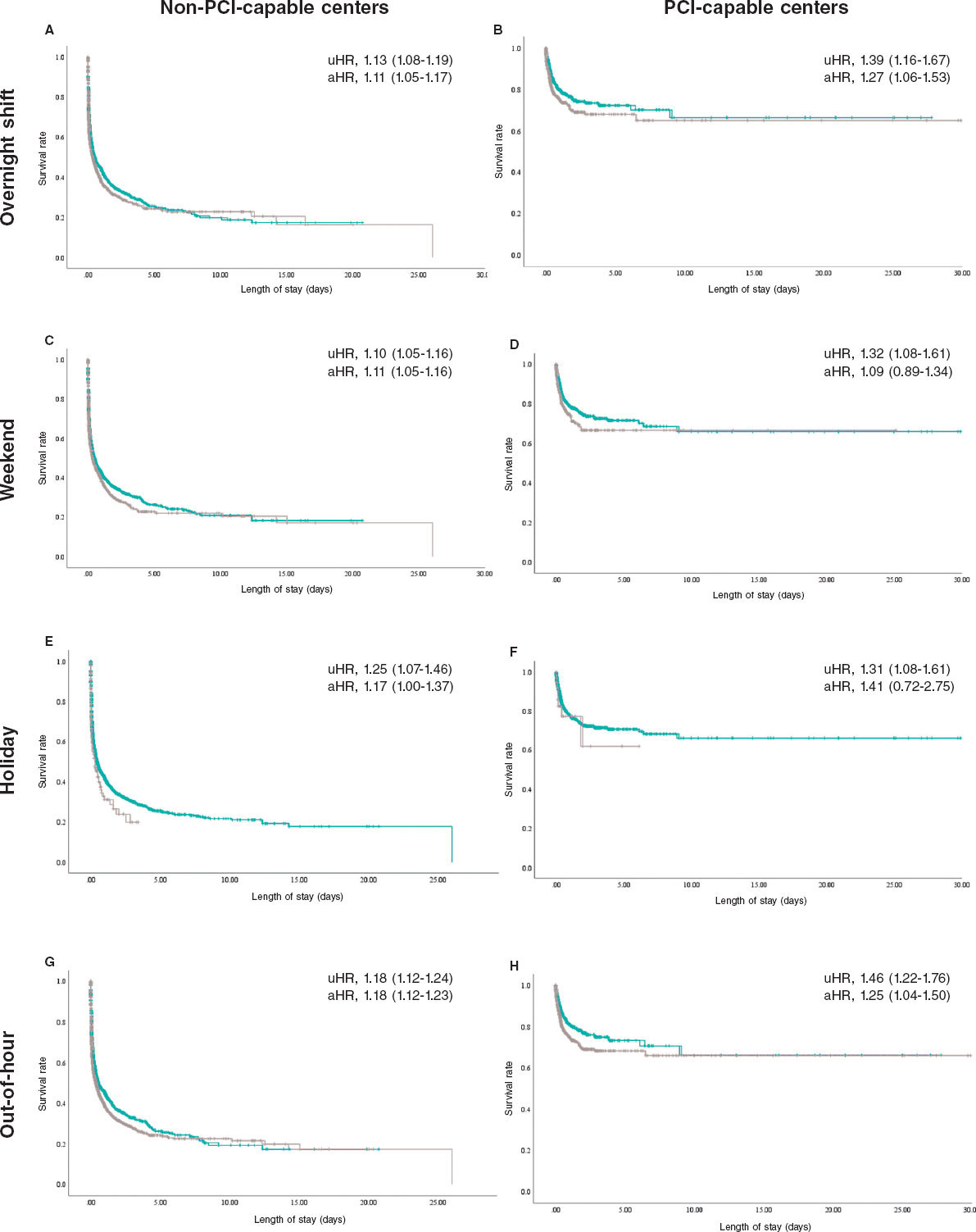

After adjusting for potential confounders, the presence of a cath lab remained protective (HR, 0.25; 95%CI, 0.23-0.28), whereas out-of-hours, night-shift admissions, and the COVID-19 pandemic continued to be associated with increased mortality in both groups. Adjusted mortality risk from out-of-hours (HR, 1.25; 95%CI, 1.04-1.50 vs HR, 1.18; 95%CI, 1.12-1.23) and night-shift admissions (HR, 1.27; 95%CI, 1.06-1.53 vs HR, 1.11; 95%CI, 1.06-1.17) persisted, while weekend and holiday effects remained significant only in non-PCI-capable centers (figure 2). Regarding cath lab characteristics, only nightshift availability (HR, 0.149; 95%CI, 0.089-0.248) and mean health care staff per shift (HR, 0.770; 95%CI, 0.710-0.834) were significantly associated with reduced mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival curves are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier analysis of mortality of out-of-hours acute myocardial infarctions by hospital type. Each column represents cath lab availability, while each row represents the components of out-of-hours admission. Each panel (A-H) shows the unadjusted (uHR) and adjusted mortality risk (aHR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

DISCUSSION

Major findings

This nationwide study examined AMI admissions across a large number of Mexican hospitals, comparing PCI-capable and non- PCI-capable centers. Out-of-hours admissions were common and associated with higher mortality, longer lengths of stay, greater shock bed use, and a higher proportion of male patients. While the presence of a cath lab appeared generally protective after adjustment, out-of-hours and nightshift admissions showed a modest increase in mortality in both groups. Although weekend and holiday effects were more evident in non-PCI-capable centers, these results should be interpreted with caution given the absence of detailed clinical data, including reperfusion strategies, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction/non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI/NSTEMI) classification, and comorbidities.

A key finding is that PCI-capable centers did not fully eliminate excess mortality during out-of-hours periods. Advanced interventional capabilities may mitigate some risk during weekends and holidays; however, challenges remain during overnight shifts, as only 32.2% of studied centers offered cath lab availability during overnight shifts. Out-of-hours admissions were associated with fewer procedures, lower staffing, and limited specialized personnel compared with regular hours, which is consistent with former studies4,8,9 (table S4). Additional factors likely contributing to poorer outcomes include reduced staffing, delays in care, limited access to specialized personnel, and the impact of human factors such as fatigue and sleep deprivation during nightshifts, despite the availability of advanced cardiac interventions.4,8,9 Longer door-to-balloon times, limited 24/7 cath lab coverage, and the relatively low number of cath labs per capita in Mexico further exacerbate these challenges. Moreover, the increased out-of-hours risk from PCI-capable centers may reflect their role as referral centers, where longer patient arrival times and procedural delays are more frequent.16

Pre-hospital and COVID-19 challenges in the management of AMI

Several institutions in Mexico have implemented programs to standardize the management of AMI, such as the IMSS and SOCIME national “Code Infarction” (2015) and ISSSTE “AsISSSTE Infarto” (2018).23,24 In contrast, SSA-affiliated institutions (Seguro Popular/INSABI/IMSS-BIENESTAR) follow more varied protocols, leading to disparities in care. Consequently, heterogeneity in the management of AMI management across institutions likely exacerbates challenges in pre-hospital care. Regulated, by NOM-034-SSA3-2013 and coordinated via Medical Emergency Regulatory Centers,25 the pre-hospital system faces challenges such as poor inter-institutional coordination, insufficient ambulance equipment, and personnel shortages, especially in rural areas. These factors increase response times and complicate AMI emergency management.26 Former studies report prolonged door-to-balloon times (up to 648 minutes) due to traffic, fragmented health care, and delayed diagnosis, with weekend and nighttime admissions independently predicting treatment delays over 12 hours. While this study does not examine treatment or pre-hospital delays, other research highlights these as major issues in Mexico. Araiza-Garaygordobil et al.16 reported a mean door-to-balloon time of 648 minutes in a Mexico City referral hospital, 3 times longer compared with developed countries, due to traffic, health care fragmentation and delayed primary diagnosis. Baños-González et al.15 found that patient delays, often from symptom unawareness or limited resources, led to late arrivals (> 12 hours), with 60% being transported by ambulance. Weekend and nighttime admissions independently predicted delays > 12 hours, with a mean 11-hour wait for first medical contact.

The COVID-19 pandemic was associated with an increased AMI mortality in both hospital groups, with a more pronounced effect in PCI-capable centers. Globally, the pandemic disrupted health care delivery, reducing hospitalizations and PCI procedures, partly due to lower referral rates and patients’ reluctance to seek care over concerns of viral exposure. Consequently, delays from symptom onset to first medical contact and prolonged door-to-balloon times occurred, both of which are known to adversely affect AMI outcomes.27 In Mexico, Rodríguez-González et al.28 reported a 51% decline in STEMI diagnoses in hospitals during early 2020, accompanied by longer arrival times and a 4.9%-6.8% increase in STEMI-related mortality. In other countries, such as Spain, PCI rates decreased by 10.1% during 2020.29 A recent meta-analysis reported a significant reduction in the number of PCI (IRR, 0.72; 95%CI, 0.67-0.77), I² = 92.5%) and an increase in time from symptom onset to first medical contact by a mean 69.4 minutes ([11-127], I² = 99.4%) during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, no significant change was observed in door-to-balloon times (3.33 minutes [0.32-6.98]; I² = 94.2%).30

Although detailed clinical data were not available in our study, the impact of treatment on AMI mortality has been extensively investigated in Mexico. The nationwide RENASCA cohort31 (21 826 patients, 2014–2017) reported high prevalence of diabetes (48%), hypertension (60.5%), smoking (46.8%), dyslipidemia (35.3%), and metabolic syndrome (39.1%) relative to multinational registries.31,32 Patients with STEMI (14.9%) experienced higher cardiovascular mortality vs patients with NSTEMI (7.6%), reflecting referral patterns and more severe in-hospital complications, including cardiogenic shock and arrhythmias. Implementation of the IMSS “Code Infarction” program reduced patients without reperfusion from 65.2% to 28.6%, increased fibrinolysis to 40.1%, and PCI to 31.3%.33 By comparison, Spain’s well-structured “Code Infarction” protocol achieved a primary PCI rate of 87%, median door-to-balloon time of 193 minutes, and minimal pre-hospital delays, with 55.3% of patients receiving timely care and most remaining delays attributable to initial diagnosis (18.5%).34

Global trends in out-of-hours mortality: a comparison across regions

Compared with previous meta-analyses, which often lack data from developing regions such as Latin America, our findings highlight important disparities. Sorita et al.4 reported higher short-term mortality rates and delayed PCI in patients with STEMI admitted outside regular hours, especially outside North America. Wang et al.5 found a slight increase in short-term mortality but no effect on long-term outcomes or PCI risk. Other analyses showed no significant differences in mortality or door-to-balloon times.35 Studies from developing countries such as Indonesia36,37 reported no mortality differences by admission time, while in Iraq,38 resource shortages and conflict led to higher out-of-hours mortality and limited reperfusion access. Latin American studies from Brazil39-41 and Argentina42 generally found no outcome differences by admission timing. Differences with our results are likely due to hospital infrastructure and staffing; Mexican public hospitals face substantial limitations after hours vs tertiary referral centers with 24/7 cath lab availability. Additionally, socioeconomic barriers and low awareness of AMI symptoms delay care, and the lack of standardized protocols further increases mortality risk.

Strategies to improve the out-of-hours management of AMI

The findings highlight several areas for improvement within the Mexican health care system, particularly regarding non-PCI-capable centers. All 3 components were associated with higher mortality, underscoring the need for enhanced pre-hospital and in-hospital management. Efforts should focus on early diagnosis, including increased availability of electrocardiography and the implementation of telemedicine platforms to allow cardiologists to promptly assess and guide treatment. Expanding access to thrombolytic therapy and ensuring experienced personnel are available during out-of-hours shifts can help reduce treatment delays. Furthermore, improving coordination across health centers through clear referral pathways, effective communication strategies, and standardized protocols, especially in hospitals serving uninsured patients, can streamline care and reduce variability in management. In PCI- capable centers, mortality was particularly elevated during overnight shifts, likely due to reduced cath lab availability within these hours. Despite existing protocols and optimized door-to-balloon times, strengthening nighttime staffing and training remains essential. This may include targeted training and incentives to encourage health care professionals to work during these shifts, thereby ensuring that high-quality care is maintained at all times.

Strengths and limitations

The present study is one of the largest cohorts to date examining the association between AMI-related mortality and time of presentation in Mexico. It provides valuable insights into the potential impact of out-of-hours admissions on outcomes, underscoring the importance of optimizing staffing, patient flow, and timely access to interventions such as PCI. Nevertheless, the findings should be interpreted with caution. The retrospective design, absence of detailed treatment information (eg, PCI, thrombolysis, door-to-balloon times), lack of comorbidity data, and inability to differentiate between STEMI and NSTEMI limit the depth and precision of the analyses. Furthermore, the study does not capture key factors such as patient-level delays, cath lab utilization patterns, or disparities in infrastructure and resource availability. Future research should integrate more comprehensive clinical and procedural data and explore the influence of provider fatigue, variability in care standards, and treatment delays to better delineate gaps in care.

CONCLUSIONS

Out-of-hours presentations were associated with high mortality rates, and contrary to findings in developed countries, the presence of a cath lab did not improve out-of-hours outcomes, which suggests that factors beyond cath lab availability, including systemic inefficiencies, resource limitations, and health infrastructure deficiencies, may profoundly affect patient outcomes in Mexico.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Women’s Hospital, SSA (Approval No. 202403-47). The research used publicly available emergency income data published by the DGIS, for which subject confidentiality is governed by the Mexican standard NOM-012-SSA3-2012. In accordance with the General Health Research Law, the study is classified as risk-free research. Sex variable was defined as according to the definition of the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) guidelines (table S1).

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools were used in the conception, design, data collection and analysis of this manuscript. All content was produced entirely by the authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

D. Arriaga-Izabal contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, data curation, data analysis, investigation, and writing of the original draft. F. Morales-Lazcano was responsible for investigation, data curation, and drafting the original manuscript. A. Canizalez-Román provided supervision, project administration, and validation, and participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Out-of-hours admissions (overnight shifts, weekends, holidays) are associated with higher AMI mortality, primarily due to treatment delays and reduced specialist availability.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Out-of-hours admissions in Mexican hospitals were associated with higher 30-day mortality rates, irrespective of cath lab availability. Although cath labs were generally protective, they did not fully mitigate risk during nights, weekends, or holidays, with increased mortality mainly observed in non-PCI-capable centers. The study is limited by the absence of detailed clinical data, including AMI type (STEMI/NSTEMI), reperfusion strategy, door-to-balloon times, and comorbidities, restricting conclusions regarding the precise impact of specialized care. Systemic factors, including staffing limitations and regional disparities, likely contribute to these outcomes, underscoring the need for improved out-of-hours AMI care.

REFERENCES

1. Ogita M, Suwa S, Ebina H, et al. Off-hours presentation does not affect in-hospital mortality of Japanese patients with acute myocardial infarction:J-MINUET substudy. J Cardiol. 2017;70:553-558.

2. Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 2010:a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380: 2095-2128.

3. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Health at a Glance 2023:OECD Indicators. 2023. Available at: https://doi.org/ 10.1787/7a7afb35-en. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

4. Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction:systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:7393.

5. Wang B, Zhang Y, Wang X, Hu T, Li J, Geng J. Off-hours presentation is associated with short-term mortality but not with long-term mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:A meta-analysis. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:0189572.

6. Yu YY, Zhao BW, Ma L, Dai XC. Association Between Out-of-Hour Admission and Short- and Long-Term Mortality in Acute Myocardial Infarction:A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8 752675.

7. Magid DJ, Wang Y, Herrin J, et al. Relationship between time of day, day of week, timeliness of reperfusion, and in-hospital mortality for patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2005;294:803-812.

8. Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Pankratz VS, Leibson CL, Stevens SR, Harris M. Nurse staffing and inpatient hospital mortality. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1037-1045.

9. Musy SN, Endrich O, Leichtle AB, Griffiths P, Nakas CT, Simon M. The association between nurse staffing and inpatient mortality:A shift-level retrospective longitudinal study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;120:103950.

10. Albuquerque GO de, Szuster E, Corrêa LCT, et al. Análise dos resultados do atendimento ao paciente com infarto agudo do miocárdio com supradesnivelamento do segmento ST nos períodos diurno e noturno. Rev Bras Cardiol Invasiva. 2009;17:52-57.

11. Cardoso O, Quadros A, Voltolini I, et al. Angioplastia Primária no Infarto Agudo do Miocárdio:Existe Diferença de Resultados entre as Angioplastias Realizadas Dentro e Fora do Horário de Rotina?Rev Bras Cardiol Invasiva. 2010;18.

12. Pérez-Cuevas R, Contreras-Sánchez SE, Doubova SV, et al. Gaps between supply and demand of acute myocardial infarction treatment in Mexico. Salud Pública México. 2020;62:540-549.

13. Robledo Z. La transformación del sistema de salud mexicano. Salud Pública México. 2024;66:767-773.

14. Gómez Dantés O, Sesma S, Becerril VM, Knaul FM, Arreola H, Frenk J. Sistema de salud de México. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53 Suppl 2:s220-32.

15. Baños-González MA, Henne-Otero OL, Torres-Hernández ME, et al. Factores asociados con retraso en la terapia de reperfusión en infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IMCEST) en un hospital del sureste mexicano. Gac Médica México. 2016;152:495-502.

16. Araiza-Garaygordobil D, González-Pacheco H, Sierra-Fernández C, et al. Pre-hospital delay of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction in Mexico City. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2019;89:174-176.

17. Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1): S31-S34.

18. Dirección General de información en Salud [DGIS]. Datos Abiertos de Urgencias. 2023. Available at: https://rb.gy/lb0tw. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

19. Procuraduría Federal de la Defensa del Trabajo. ¿Sabes Cuáles Son Los Días de Descanso Obligatorio Para Este 2024?. 2023. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/profedet/articulos/sabes-cuales-son-los-dias-de-descanso-obligatorio-para-este-2024. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

20. Secretaría de Salud. México pone fin a la emergencia sanitaria por COVID-19. 2023. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/salud/prensa/mexico-pone-fin-a-la-emergencia-sanitaria-por-covid-19-secretaria-de-salud. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

21. Diario Oficial de la Federación [DOF]. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-012-SSA3-2012, Que establece los criterios para la ejecución de proyectos de investigación para la salud en seres humanos. 2013. Available at: https://platiica.economia.gob.mx/normalizacion/nom-012-ssa3-2012/. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

22. Diario Oficial de la Federación [DOF]. NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-012-SSA3-2012, Que establece los criterios para la ejecución de proyectos de investigación para la salud en seres humanos. 2013. Available at: https://platiica.economia.gob.mx/normalizacion/nom-012-ssa3-2012/. Accessed 25 Jan 2025.

23. Robledo-Aburto ZA, Duque-Molina C, Lara-Saldaña GJ, Borrayo-Sánchez G, Avilés-Hernández R, Reyna-Sevilla A. Protocolo de atención Código Infarto, hacia la federalización de IMSS-Bienestar. Rev Médica Inst Mex Seguro Soc. 2022;60(Suppl 2):S49-S53.

24. Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers or Civil Service Social Security and Services Institute (ISSSTE). Con Asissste Infarto disminuye mortalidad por problemas cardiovasculares. .mx. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/issste/prensa/con-asissste-infarto-disminuye-mortalidad-por-problemas-cardiovasculares. Accessed 21 Jan, 2025.

25. Diario Oficial de la Federación [DOF]. NOM-034-SSA3-2013, Regulación de los servicios de salud. Atención médica prehospitalaria. 2013. Available at: https://platiica.economia.gob.mx/normalizacion/nom-034-ssa3-2013/. Accessed 26 2025 Jan.

26. Ministry of Health (SSA). Modelo de Atención Médica Prehospitalaria. 2017. Available at: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/250824/MODELO_DE_ATENCION_MEDICA_PREHOSPITALARIA.pdf. Accessed 21 2025 Jan

27. Sharma A, Razuk V, Nicolas J, Beerkens F, Dangas GD. Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic:implications for the cardiac catheterization laboratory and its current practices. J Transcat Interv. 2022;30 eA20220003.

28. Rodríguez-González EF, Briceño-Gómez EE, Gómez-Cruz EJ, Rivas-Hernández Z, Chacón-Sánchez J, Cabrera-Rayo A. ¿A dónde se fueron los infartos de miocardio durante la pandemia por COVID-19 en México?Med Interna México. 2023;39:538-540.

29. Romaguera R, Ojeda S, Cruz-González I, Moreno R. Spanish Cardiac Catheterization and Coronary Intervention Registry. 30th Official Report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2020) in the year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2021;74:1095-1105.

30. Nadarajah R, Wu J, Hurdus B, et al. The collateral damage of COVID-19 to cardiovascular services:a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2022;43: 3164-3178.

31. Borrayo-Sánchez G, Rosas-Peralta M, Ramírez-Arias E, et al. STEMI and NSTEMI:Real-world Study in Mexico (RENASCA). Arch Med Res. 2018; 49:609-619.

32. Tang EW, Wong CK, Herbison P. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) hospital discharge risk score accurately predicts long-term mortality post acute coronary syndrome. Am Heart J. 2007;153:29-35.

33. Martinez-Sanchez C, Borrayo G, Carrillo J, Juarez U, Quintanilla J, Jerjes-Sanchez C. Clinical management and hospital outcomes of acute coronary syndrome patients in Mexico:The Third National Registry of Acute Coronary Syndromes (RENASICA III). Arch Cardiol México. 2016;86:221-232.

34. Rodríguez-Leor O, Cid-Álvarez AB, Pérez de Prado A, et al. Analysis of the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in Spain. Results from the ACI-SEC Infarction Code Registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2022; 75:669-680.

35. Wang X, Yan J, Su Q, Sun Y, Yang H, Li L. Is there an association between time of admission and in-hospital mortality in patients with non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction?A meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:14409.

36. Dharma S, Dakota I, Sukmawan R, Andriantoro H, Siswanto BB, Rao SV. Two-year mortality of primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction during regular working hours versus off-hours. Cardiovasc Revascularization Med Mol Interv. 2018;19(7 Pt B):826-830.

37. Javanshir E, Ramandi ED, Ghaffari S, et al. Association Between Off-hour Presentations and In-hospital Mortality for Patients with Acute ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Treated with Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2020;32:242-247.

38. Al-Asadi JN, Kadhim FN. Day of admission and risk of myocardial infarction mortality in a cardiac care unit in Basrah, Iraq. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:579-584.

39. Machado GP, Araujo GN de, Mariani S, et al. On- vs. -hours admission of patients with ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions:data from a tertiary university brazilian hospital. Clin Biomed Res. 2018;38:30-34.

40. Evangelista PA, Barreto SM, Guerra HL. Hospital admission and hospital death associated to ischemic heart diseases at the National Health System (SUS). Arq Bras Cardiol. 2008;90:130-138.

41. Barbosa R, Cesar F, Bayerl D, et al. Acute Myocardial Infarction and Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at Night Time. Int J Cardiovasc Sci. 2018;2018;31:513-519.

42. Rosende A, Mariani JA, Abreu MD, Gagliardi JA, Doval HC, Tajer CD. Distribución de la frecuencia de síndrome coronario agudo acorde al día de la semana. Análisis del Registro Epi-Cardio. Rev Argent Cardiol. 2015; 83:1-10.