Abstract

In Mexico, the number of confirmed and estimated cases of COVID-19 has been going up gradually from the second week of March 2020. This directly and indirectly altered the normal care of patients with ischemic heart disease. This is a consensus document achieved by different societies (the Mexican Society of Interventional Cardiology [SOCIME], the Mexican Society of Cardiology [SMC], the Mexican National Association of Cardiologists [ANCAM], the National Association of Cardiologists at the Service of State Workers [ANCISSSTE]), and the Coordinating Commission of National Institutes of Health and High Specialty Hospitals [CCINSHAE]). Its main objective is to guide the decision-making process on coronary revascularization procedures for the management of patients with acute coronary syndrome in catheterization laboratories during the current health emergency generated by the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

Keywords: Myocardial infarction. Acute coronary syndrome. Percutaneous coronary intervention. COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2. Pandemic.

RESUMEN

En México, el número de casos confirmados y estimados de COVID-19 inició su ascenso progresivo a partir de la segunda semana de marzo de 2020, lo que alteró de forma directa e indirecta la atención habitual de los pacientes con cardiopatía isquémica. Este documento es un consenso de la Sociedad de Cardiología Intervencionista de México (SOCIME), la Sociedad Mexicana de Cardiología (SMC), la Asociación Nacional de Cardiólogos de México (ANCAM), la Asociación Nacional de Cardiólogos al Servicio de los Trabajadores del Estado (ANCISSSTE) y la Comisión Coordinadora de Institutos Nacionales de Salud y Hospitales de Alta Especialidad (CCINSHAE) que tiene como objetivo prioritario orientar las decisiones de revascularización coronaria, en particular en los pacientes con síndrome coronario agudo, en las salas de cateterismo, durante el tiempo que dure la urgencia sanitaria por la pandemia de SARS-CoV-2.

Palabras clave: Infarto de miocardio. Síndrome coronario agudo. Intervención coronaria percutánea. COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2. Pandemia.

INTRODUCTION

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in Mexico. Consequently, the number of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) or stable chronic coronary syndrome who will require medical services is not expected to go down during the pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The ongoing need to manage this disease during the COVID-19 pandemic compels us to recognise the exceptional situation and to search for an adequate response.

Several places across the world have suspended the management of ischemic patients or decided to use less invasive—also less effective—treatments. The idea behind this is to reduce the risk of contagion for patients, relatives, and healthcare workers. However, this decision has created huge controversy in the medical establishment: is it safe? Is it ethical? Is the safety of the medical team more important than the patients’ health? For how long should this measure be effective?

The Mexican Interventional Cardiology Society (SOCIME) backed by the Mexican Society of Cardiology (SMC), the National Association of Cardiologists of Mexico (ANCAM), and the National Association of Cardiologists at the Service of State Workers (ANCISSSTE) have published this document to guide the medical personnel in the decision-making process during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

PATIENT CLASSIFICATION

Healthcare workers looking after patients with ischemic heart disease should classify them into 2 groups based on the information available during the healthcare process: 1) patients with suspected SARS-CoV-2 infection or patients with symptoms of concurrent myocardial ischemia or other heart-related complications; 2) other patients, without a diagnosis or suspicion of SARS-CoV-2 infection, who require medical attention due to symptoms of myocardial ischemia. The reason for making this subdivision is to minimise the contagion of other patients, relatives, medical and hospital personnel by avoiding contact between uninfected patients and patients with SARS-CoV-2. Before being transferred to the cath lab all patients will be actively screened for the presence of fever, cough, and respiratory distress. The patients’ temperature and arterial oxygen saturation will need to be checked as well.

STABLE CHRONIC CORONARY SYNDROMES

There is general consensus that invasive procedures—whether percutaneous or surgical—should be differentiated in patients with stable chronic coronary syndrome during the current health emergery.1,2 The undersigned working group that participated in the writing of this document agrees on the adoption of this measure. However, it also admits that the number of patients who will not receive proper care will end up accumulating and a proportion of these patients will turn into new cases of acute ischemia. In conclusion, patients with stable chronic coronary syndrome during the current pandemic should receive optimal therapy and be warned of the importance of seeking urgent medical attention in the presence of symptoms of ischemic instability.

ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROMES

In the current context of the COVID-19 pandemic, there is no unanimous agreement to define the optimal treatment strategy for patients with ACS. We will be reviewing the information available accumulated over a very short period of time on the different treatment proposals reported followed by the position and recommendations from this group.

Classification

ACSs can be divided into: a) ST-segment elevation ACS including ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and b) non-ST-segment elevation ACS including non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and unstable angina.

Diagnosis

Two recommendations should be followed to minimize the risk of contagion. The first one should be social distancing and limited contact with patients during the physical examination or while performing the transthoracic echocardiogram to obtain the maximum amount of information while minimizing physical contact with the patient; the second recommendation is the use of coronary computed tomography angiography as a fast non-invasive imaging modality to confirm or discard the presence of coronary heart disease as the cause for the symptoms when appropriate.3 The main elements for diagnosis are:

-

- Suggestive symptoms.

-

- Twelve-lead electrocardiogram.

-

- Myocardial biomarkers.

-

- Coronary computed tomography angiography: when available, it should be considered in the case of reasonable doubt on the coronary origin of the symptoms. It speeds up the confirmation/discarding process, reduces hospital stay and use of hospital resources and minimizes stay in the cath lab and exposure to contagion for the heart team who work in the cath lab.

Management of STEMI

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (pPCI) is the treatment of choice for coronary reperfusion. Fibrinolysis is spared for cases where percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is not available or when the patient transfer to a PCI capable hospital involves significant time delays.4 The COVID-19 pandemic has produced different points of view for the management of patients with STEMI; these different positions are indicative of the particular situations that medical societies are facing to design their recommendations.

Fibrinolysis as the strategy of choice

A report and the position adopted by opinion leaders recommend the use of fibrinolysis as the first reperfusion strategy in both uninfected patients and patients with suspicion or diagnosis of COVID-19. The PCI would be spared for cases of failed fibrinolysis and only if benefits exceed the possible risks.5 They recommend that patients with serious pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2, unstable vital signs, and concurrent STEMI should receive support medical treatment only—no fibrinolysis or pPCI—until they have recovered from pneumonia. These recommendations are highly restrictive, do not anticipate the pPCI option and limit the possibility of bailout PCIs in selected cases.5

pPCI as the strategy of choice

Several medical societies are keeping to their usual recommendations during the current pandemic. Patients with STEMI (with or without suspicion of infection, with or without COVID-19) inescapably need medical attention and should receive pPCI as the reperfusion therapy, especially those with persistent angina or hemodynamic compromise; they also keep the bailout PCI option alive. They accept that fibrinolysis can be an alternative in patients with pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 who develop STEMI but remain stable.1,2,6 The Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) ranks pPCI as the preferred reperfusion strategy in most patients with severe pneumonia and difficulties moving or being transferred.7 At the present time, Spain is one of the countries with the highest contagion and mortality rates and its healthcare system has collapsed due to the excessive volume of patients with COVID-19; in the middle of this health crisis, consensus still favors the reperfusion of STEMI through pPCI.

Management of non-ST-segment elevation ACS

In general, the specific risk of complications of patients with NSTEMI or unstable angina should be identified to decide the best time to perform cardiac catheterization. Regardless of their risk, it is essential to know the patients’ coronary anatomy and based on the findings assess the revascularization method.8 As with STEMI, this routine common practice has changed during the current pandemic and several of the position papers on the management of ST-segment elevation ACS have been replicated.

Medical therapy as the strategy of choice

The general recommendation is to know the state of contagion before referring patients to the cath lab Patients without a diagnosis or suspicion of infection need to be tested to confirm or discard the presence of SARS-CoV-2. It is suggested that patients with suspicion of COVID-19 who have not been tested yet and those who have already tested positive should receive medical therapy. The interventional procedure should be deferred until they have recovered or the risk of contagion has gone down.7 It is recommended that patients without suspicion of infection or without COVID-19 (common patients) undergo PCI only if they are high-risk patients or remain unstable during the course of conservative treatment. Urgent PCIs will be spared only for patients with hemodynamic compromise or malignant arrhythmias regardless of their state of infection.6,7

PCI as the strategy of choice

Here the usual recommendations still stands, which is why high-and-intermediate risk patients should undergo PCI, regardless of their state of contagion.8 In low-risk patients with COVID-19 or with severe pneumonia and who remain unstable it is advised to consider medical therapy and defer the procedure. Early PCIs facilitate early hospital discharges. In patients with multivessel disease the PCI should be favored over coronary revascularization surgery. Patients admitted to hospitals without cath lab capabilities should not be transferred. In these cases, conservative treatment is advised followed by early hospital discharges.1,2

CONSENSUS ELEMENTS

The following variables were taken into consideration while the recommendations of this consensus document were being designed:

-

Contagion. When examined, patients who seek medical attention should be classified according to their current state of SARS-CoV-2 infection regardless of the presence of symptoms. A special subgroup are unstable patients with severe pneumonia who develop ACS.

-

Timeframe. At different times and different speeds peaks and troughs in the number of patients with COVID-19 are expected to happen.

-

Geographic location. More cases are expected in more heavily populated cities in particular the Mexico City metropolitan area, Guadalajara, Monterrey, and Puebla.

-

Healthcare system. There are different healthcare models available in Mexico. In general, in private hospitals cath labs are opened around the clock. In the public system several secondary care centers have cath lab capabilities with different care plans for the management of ACS. Most tertiary care centers have pPCI programs available around the clock too.

-

Therapeutic effectiveness. In the full spectrum of ACS, PCI is the treatment of choice. In patients with STEMI, fibrinolysis is a less effective alternative associated with a higher risk of bleeding complications. In patients with non-ST-segment elevation ACS, medical therapy in the acute phase is only intended to stabilize the atheromatous plaque and alleviate myocardial ischemia before the cath. lab. referral.

-

Risk profile. In the full spectrum of ACS, it is essential to examine patients at increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events early. This group of patients benefits the most from invasive treatment.

-

Hospital stay. Anticipating larger volumes of patients in a prolonged emergency situation, it is advised to shorten hospital stays to alleviate the work load, reduce the use of hospital resources, reduce the exposure of patients, relatives, medical and paramedic personnel to a potentially contaminated environment, empty beds, and facilitate the ongoing rotation of patients.

-

Rooms and special catheterization laboratories. According to the type, size, and resources of each hospital, whether public or private, a specific physical space should be spared to examine patients without COVID-19 or clinical suspicion away from patients with confirmed infections or a justified suspicion of infection. In public and private hospitals with at least 2 cath labs it is possible to use 1 cath lab for the specific care of patients with confirmed or suspected CODIV-19 and the other one for the management of common patients. In public or private hospitals with only 1 cath lab available, the heart team should look for alternatives to perform the procedures while minimizing the risk of contagion. This can be done by splitting the care schedule depending on the patients’ state of infection and only if the clinical indication for cardiac catheterization allows it (managing infected or suspicious patients in the morning, and uninfected or unsuspicious patients in the afternoon). Reducing the number of healthcare workers in the cath lab and organizing groups and shifts during specific timeframes helps too. Regardless of the number of cath labs available, it is a priority to observe the recommendations established for adequate protection of the heart team, which should be the smallest possible. Also, the cath lab should be disinfected before taking on the next patient.

-

Personal protective equipment. The medical personnel looking after patients, whether infected or suspicious, should all have the necessary personal protective equipment and observe the protection measures recommended like those from the Interventional Cardiology Association and Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology.9

RECOMMENDATIONS

The objective of this document is to guide the decision-making process on the coronary revascularization of patients with ACS during the health emergency declared due to the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Considering the elements described above and anticipating an epidemiological model similar to the one seen in countries like ours, we recommend making slight modifications to the management of patients with ACS while continuing to use the pharmacoinvasive reperfusion strategy prevalent in Mexico.

STEMI

Cardiovascular risk

We recommend that pharmacoinvasive strategy should start by identifying patients with higher risk of complications. The presence of 1 or more of the following characteristics is indicative of high risk:

– Age > 75 years.

– Cardiogenic shock (whether associated or not to mechanical complications).

– Refractory angina.

– Ventricular tachyarrhythmias.

– Bradyarrhythmia requiring temporary pacemaker implantation.

– Electrocardiographic pattern of diffuse ischemia.

pPCI

We recommend public and private hospitals with cath lab capabilities and, in particular, tertiary care or reference centers to keep offering pPCI over fibrinolysis. This is completely justified by its higher rate of success, lower risk of complications, and shorter hospital stays (hospital discharges within 36 h - 48 h). The fibrinolysis proposal as the primary reperfusion method even in hospitals with cath lab is questionable.

Fibrinolysis

We still recommend its indication as the reperfusion method in non-PCI capable centers. Unlike conventional pharmacoinvasive strategy, the transfer of stable patients with successful fibrinolysis for early elective cardiac catheterization is ill-advised; these patients should be followed and monitored later in time. Only patients with failed fibrinolysis should be transferred and only in the presence of hemodynamic or electric instability. In patients with severe pneumonia due to COVID-19 it is a valid option even for PCI-capable centers in the presence of high and growing volumes of suspicious or confirmed cases. Also, in the absence of high-risk markers, especially in patients admitted within the first 3 hours after symptom onset and without contraindications for fibrinolysis.

Periodic adjustment of reperfusion method

We recommend that in cities, regions, and hospitals with large volumes of patients with COVID-19 or suspected cases, whether critical, growing or rapidly spiking, the hospital management should decide on the most adequate reperfusion method with the heart team and the resources available. The primary reperfusion strategy should adjust periodically based on the temporal and geographic pattern of the infection.

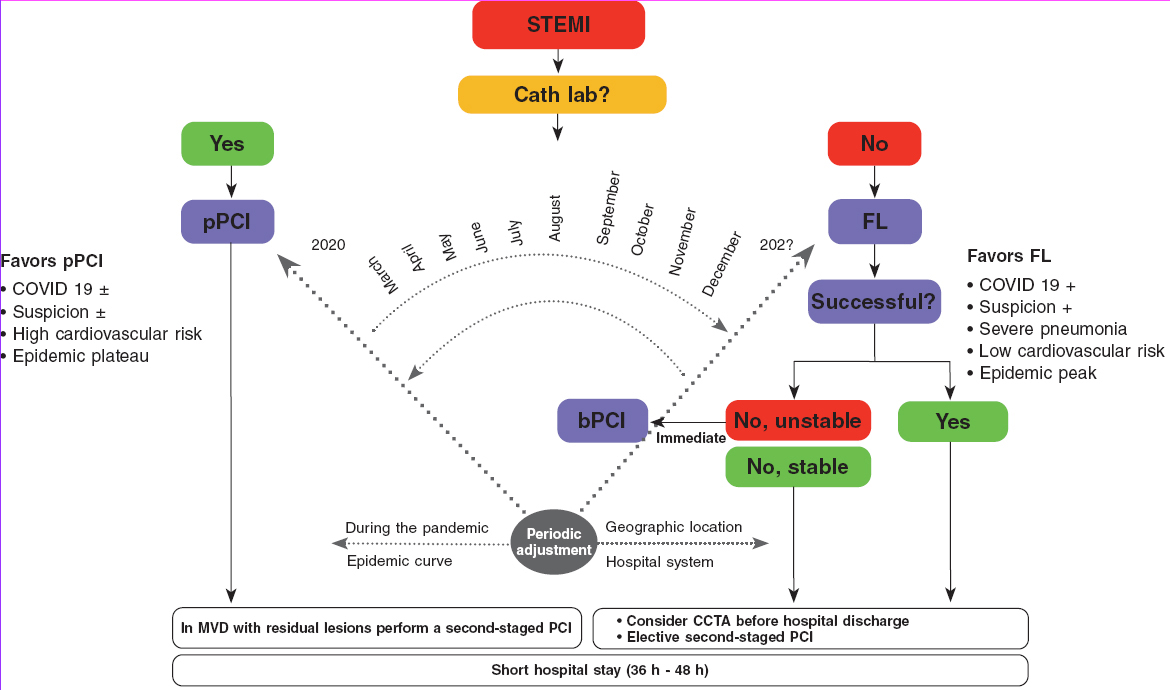

The algorithm shown on figure 1 for the management of patients with STEMI during the current COVID-19 pandemic recommends pPCI as the method of choice for coronary reperfusion. The reperfusion strategy should change as the pandemic evolves with the necessary, periodic adjustments based on the modification criteria already described.

Figure 1. Therapeutic algorithm for the management of patients with STEMI during the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The arrow thickness is indicative of the preferred therapy. +, present; ±, present or absent; bPCI: bailout percutaneous coronary intervention; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; FL, fibrinolysis; MVD, multivessel coronary artery disease; pPCI, primary percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

NSTEACS

Regardless of the presence of SARS-CoV-2, low-risk patients who respond to medical therapy can be discharged from the hospital to be studied later in time if the risk of contagion is lower or if they have recovered from COVID-19. If the patient’s coronary anatomy needs to be documented prior to hospital discharge, an option here is to perform a coronary computed tomography angiography and, based on the findings, plan the PCI or discharge the patient. Moderate-or-high risk patients (according to the criteria described above) and those who become unstable during the course of conservative treatment should be transferred to the cath lab regardless of their state of contagion.

Most concepts described for the management of STEMI are valid in these patients. PCI-capable public and private hospitals with experienced personnel and the necessary resources should keep the PCI option open in light of its high rate of success and short hospital stays. In patients with significant multivessel disease the hospital stay should be short and PCI revascularizations should be prioritized over coronary revascularization surgeries.

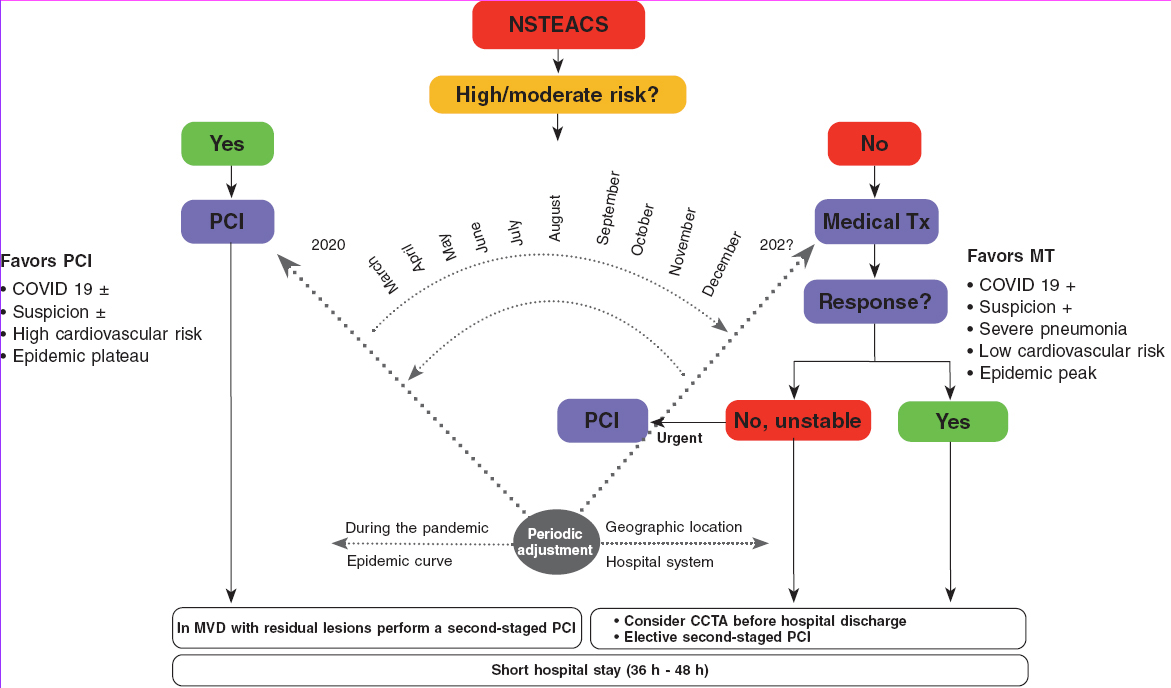

In the algorithm shown on figure 2 for the management of patients with NSTEACS during the current COVID-19 pandemic the use of PCI is recommended in high-risk patients. However, the reperfusion strategy should be dynamic as the pandemic evolves with periodic adjustments based on the modification criteria already described.

Figure 2. Algorithm for the management of patients with NSTEACS during the current SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. The arrow thickness is indicative of the preferred therapy. +, present; ±, present or absent; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; MT, medical therapy; MVD, multivessel coronary artery disease; NSTEACS, non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; Tx, treatment.

Cardiovascular complications in patients with COVID-19

Patients with COVID-19 can have clinical signs of myocardial damage and secondary complications. Myocardial damage with elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin levels (7.2%), cardiogenic shock (8.7%), and arrhythmias (16.7%) has been reported in some patients. In the absence of coronary heart disease, the gradual increase of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin levels is a predictor of mortality.10 Cases of type I STEMI and fulminant myocarditis have also been reported.11

Most of the patients who develop complications are eligible for intensive therapy, and a high percentage of these may end up needing mechanical support of the ventricular function. The etiology of patients with cardiovascular complications can be coronary heart disease; this consideration will not be rare because the characteristics of patients more often affected are old age, overweight, high blood pressure, and diabetes mellitus. If the hypothesis of concomitant coronary heart disease is accepted there are two possible avenues: treat the case as that of a patient with NSTEMI and follow the corresponding algorithm or discard the presence of significant coronary heart disease using coronary computed tomography angiography.

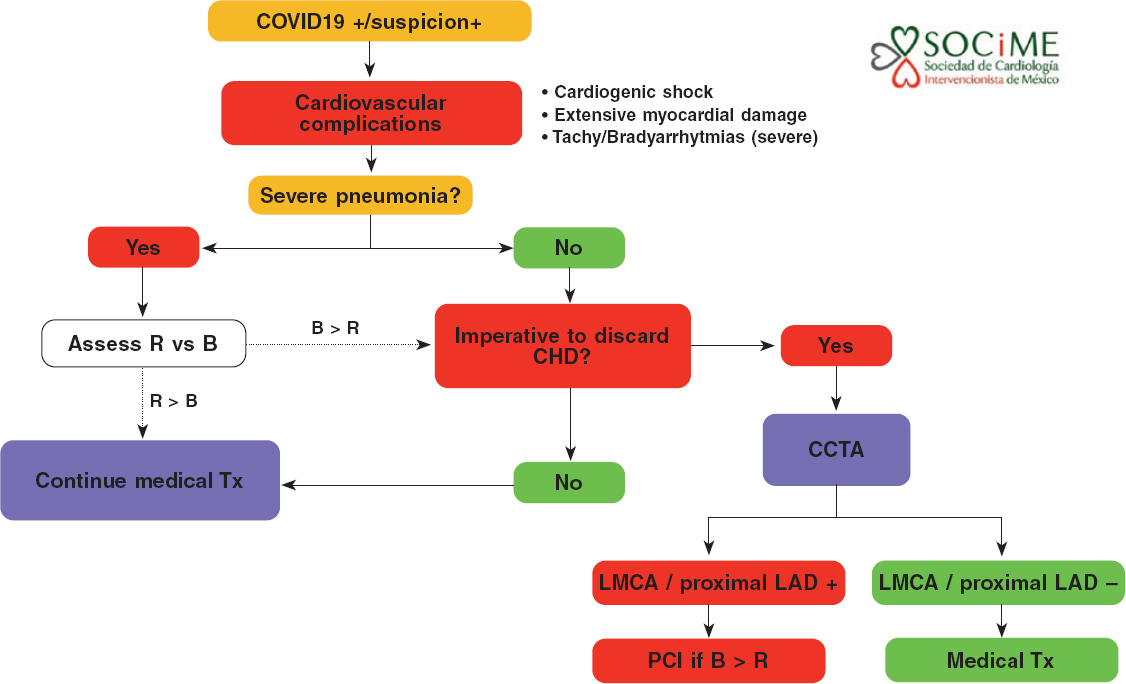

In patients with severe pneumonia, myocardial damage, hemodynamic or electric instability, and suspicion of coronary heart disease, the medical team should decide on the adequacy (benefits exceeding risks, patients who can be saved) of transferring the patient to the cath lab or performing a coronary computed tomography angiography. In particular, the presence of left main coronary artery disease or disease of the proximal left anterior descending artery in a patient who can be saved supports the need to perform an urgent PCI (figure 3).

Figure 3. Diagnostic-therapeutic algorithm for the management of patients with COVID-19 or suspicion of COVID-19 infection with cardiovascular complications. B, benefits; CHD, coronary heart disease; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; LAD, left anterior descending coronary artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery disease; R, risk; Tx, treatment.

VALIDITY OF RECOMMENDATIONS

The epidemiological model is totally unpredictable under the current circumstances; the rate of contagion, number of confirmed cases, and mortality rates are different across cities, regions, countries, and continents. However, estimates from the Mexican Ministry of Public Health suggest a peak of cases and more hospitalizations in the metropolitan area of Mexico City and main cities of the nation from May through August 2020. The flattening of the curve of infection will still take several months. No definitive projection on this regard can be given at the present time.

These recommendations will remain effective as necessary. They will be re-evaluated periodically together with the Mexican Ministry of Public Health to discuss the right time to go back to normal.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None reported.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Dr. Jorge Gaspar Hernández, General Manager of the Ignacio Chávez National Institute of Cardiology for his remarks on this manuscript.

EDITOR’S NOTE

This document is subject to further iterations based on the evolution of the current COVID-19 pandemic. This manuscript has undergone a process of internal review of exceptional priority by the editorial staff due to the special interest of disclosing the information contained herein to the scientific community. The editors wish to thank Permanyer Publications for its collaboration and commitment for the quick publication of this document.

REFERENCES

1. Welt FGP, Shah PB, Aronow HD, et al. Catheterization Laboratory Considerations During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic:From ACC's Interventional Council and SCAI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.021.

2. National Health Service. Specialty guides for patient management during the coronavirus pandemic. Clinical guide for the management of cardiology patients during the coronavirus pandemic. 2020. Disponible en:https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/specialty-guide-cardiolgy-coronavirus-v1-20-march.pdf. Consultado 20 Mar 2020.

3. Yang S, Manjunath L, Willemink MJ, Nieman K. The role of coronary CT angiography for acute chest pain in the era of high-sensitivity troponins. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13:267-273.

4. Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation:The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119-177.

5. Zeng J, Huang J, Pan L. How to balance acute myocardial infarction and COVID-19:the protocols from Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05993-9.

6. Society of Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Mahmud E. The Evolving Pandemic of COVID-19 and Interventional Cardiology. Disponible en:http://www.scai.org/press/detail/evolving-pandemic-of-covid-19-interventional-cardi#.XpKuBi2ZM6h. Consultado 18 Mar 2020.

7. Romaguera R, Cruz-Gonza?lez I, Jurado-Roma?n A, et al. Considerations on the invasive management of ischemic and structural heart disease during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. Consensus statement of the Interventional Cardiology Association and the Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiac Care Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. REC Interv Cardiol.2020. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M20000121.

8. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation:Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315.

9. Romaguera R, Cruz-González I, Ojeda S, et al. Consensus document of the Interventional Cardiology and Heart Rhythm Associations of the Spanish Society of Cardiology on the management of invasive cardiac procedure rooms during the COVID-19 coronavirus outbreak. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.24875/RECICE.M20000116.

10. Xiong TY, Redwood S, Prendergast B, Chen M. Coronaviruses and the cardiovascular system:acute and long-term implications. Eur Heart J. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa231.

11. Xu Z, Shi L, Wang Y, et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420-422.