Special article

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;2:108-119

Requirements and sustainability of primary PCI programs in Spain for the management of patients with STEMI. SEC, AEEC, and SEMES consensus document

Requisitos y sostenibilidad de los programas de ICP primaria en España en el IAMCEST. Documento de consenso de SEC, AEEC y SEMES

a Área de Enfermedades del Corazón, Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge, IDIBELL, Universidad de Barcelona, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain b Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de León, León, Spain c Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain d Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain e Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol, Badalona, Barcelona, Spain f Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Galdakao-Usansolo, Galdakao, Vizcaya, Spain g Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario La Paz, IDIPAZ, Madrid, Spain h Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain i Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Álvaro Cunqueiro, Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain j Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain k Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria, Málaga, Spain l SUMMA 112, Madrid, Universidad Alfonso X el Sabio, Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain m Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital do Salnés, Vilagarcía de Arousa, Pontevedra, Spain n Urgencias Sanitarias de Galicia 061, Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain o Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain p Servicio de Cardiología, Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía, Córdoba, Spain

ABSTRACT

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is established as the standard of care for patients across all surgical risk profiles, with expanding indications in younger and lower-risk populations. A substantial proportion of patients eligible for TAVI have preexisting cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED). Temporary transvenous right ventricular (RV) pacing is routinely used during TAVI to facilitate procedural safety but carries inherent risks, including RV perforation, cardiac tamponade, and lead dislodgement. Alternative pacing strategies, such as left ventricular pacing via the valve delivery guidewire, have been proposed to reduce procedural complications. In patients with a preexisting CIED, leveraging the implanted device for procedural pacing represents a rational and potentially safer option. However, its adoption remains limited, largely due to unfamiliarity with device-specific programming. This article provides a detailed, step-by-step practical guide for programming rapid ventricular pacing using the most widely encountered CIED platforms: Biotronik, Medtronic, Abbott/St. Jude, Sorin, and Boston Scientific. The specific programming pathways for each manufacturer are summarized to facilitate safe, effective, and reproducible implementation during TAVI.

Keywords: TAVI. Pacing. Cardiac implantable electronic devices. Ventricular perforation.

RESUMEN

El implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) se ha establecido como el estándar de atención para pacientes de todos los perfiles de riesgo quirúrgico. Una proporción significativa de los candidatos a TAVI son portadores de dispositivos cardiacos implantables (DCI). La estimulación ventricular derecha transvenosa temporal es una práctica habitual, pero conlleva riesgos como perforación ventricular, taponamiento y desplazamiento del electrodo. Para reducir las complicaciones se han propuesto estrategias de estimulación alternativas, como la estimulación ventricular izquierda a través de la guía de liberación de la válvula; sin embargo, en los pacientes con un DCI preexistente, aprovechar dicho dispositivo para la estimulación durante el procedimiento representa una opción racional y potencialmente más segura. No obstante, su utilización sigue siendo limitada, principalmente debido al desconocimiento de la programación específica de cada dispositivo. Este artículo ofrece una guía práctica detallada, paso a paso, para la programación de la estimulación ventricular rápida utilizando las plataformas de DCI más comunes (Biotronik, Medtronic, Abbott/St. Jude, Sorin y Boston Scientific) y se resume las rutas de programación específicas de cada fabricante para facilitar una implementación segura, eficaz y reproducible.

Palabras clave: TAVI. Marcapasos. Dispositivos cardiacos implantables. Perforación ventricular.

Abbreviations

CIED: cardiac implantable electronic device. ICD: implantable cardioverter defibrillator. NIPS: non-invasive programmed stimulation. RV: right ventricular. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as the preferred therapeutic option across the full spectrum of surgical risk, and more recently its indications have expanded to include younger patients and those at low surgical risk.1-4 Patients undergoing TAVI are typically elderly and burdened with significant cardiovascular comorbidities, with a considerable proportion (8.7% to 23.1%) having preexisting cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED).5-6

Temporary transvenous pacing is a well-established and integral component of TAVI, facilitating procedural success by reducing cardiac contractility during balloon aortic valvuloplasty and valve deployment. The target pacing rate varies according to the valve type: approximately 120 bpm for self-expanding valves and approximately 180 bpm for balloon-expandable valves.7 In the 2 scenarios, the objective is to mitigate the risk of micro- or macro-dislodgement or embolization during implantation.

Notwithstanding its utility, temporary right ventricular (RV) pacing is associated with potential complications, including myocardial injury, RV dysfunction, and perforation, which may culminate in cardiac tamponade.8-10 Furthermore, lead dislodgement and pacing failure have been reported among patients undergoing temporary pacing for a variety of indications, with incidence rates of approximately 4.6% and 9.5%, respectively. Although these figures are not specific to TAVI, they highlight that such complications are not rare and may result in ineffective pacing or sensing, thereby increasing the risk of critical intraoperative events, such as valve embolization or migration.11

To address these limitations, alternative pacing strategies have been proposed. Among them, left ventricular pacing via the valve delivery guidewire offers several advantages, such as elimination of the need for venous access, reduction of the risk of RV perforation, and potential reduction in procedural duration.12,13

In patients with preexisting CIED, use of the permanent device for procedural pacing appears to be a rational strategy to minimize complications.

The present article aims to address this unmet need by providing a concise and practical step-by-step guide for the use of the most widely encountered CIED programming consoles, thereby promoting safer and more efficient pacing management during TAVI.

USE OF ICD PROGRAMMING CONSOLES

This step-by-step guide for pacing patients with preexisting CIED during TAVI is derived from the routine clinical practice of our high-volume TAVI center, developed in close collaboration with our Electrophysiology Unit and in full compliance with the usage recommendations provided by our industry partners.

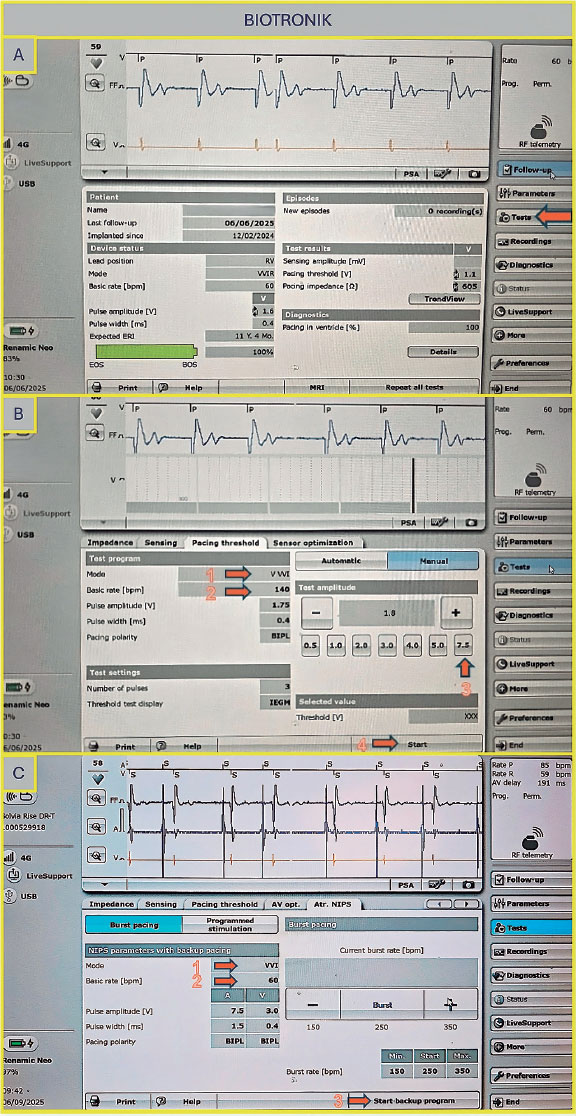

Biotronik (Germany)

Not all pacemaker models support electrophysiological testing. However, this limitation can be overcome by using the threshold measurement section. Select “Test”, then “Pacing Threshold”, and choose “Manual” (figure 1A,B). First, select the pacing mode (eg, VVI), then set the desired pacing rate (up to 200 bpm) and ensure the output is set to the maximum (7.5V) to guarantee proper capture. Once all parameters are configured, press the “Start” button to begin stimulation, which will continue until manually stopped. If the device supports rapid pacing, such as non-Invasive programmed stimulation (NIPS), overdrive pacing can be performed using the VVI or V00 mode (figure 1C). Select the desired mode and basic rate, then press the “Start Backup Program” button.

Figure 1. A: main screen of the Biotronik console. Select “Test” as indicated by the arrow to proceed to the pacing tests. B: to proceed to the pacing tests, select “Manual,” then set the following parameters: pacing mode (arrow 1), basic rate (arrow 2), amplitude (arrow 3), and press “Start” to initiate pacing (arrow 4). C: configure the NIPS parameters by selecting VVI mode (arrow 1), setting the basic rate (arrow 2), and pressing “Start” to begin pacing (arrow 3). NIPS: Non-Invasive Programmed Stimulation.

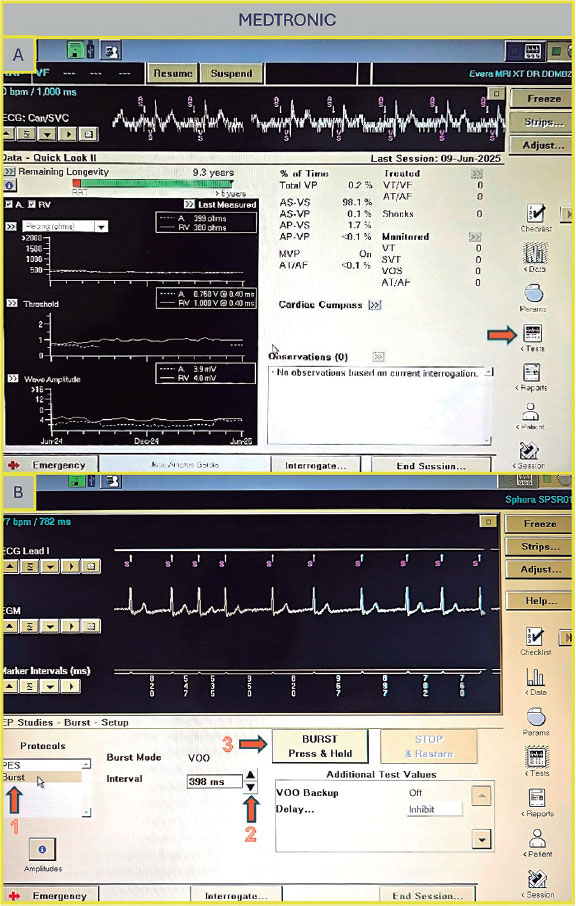

Medtronic (United States)

Once on the main screen (figure 2A), press the “Test” tab, then navigate to “Electrophysiology Study” and select either “Fixed Burst” or “Burst” (figure 2B). The interface will prompt you to choose the chamber in which pacing will be applied — select “Right Ventricular”. Adjust the interval to the desired value (as the interval decreases, the frequency increases — for example, 200 bpm corresponds to 300 ms). Once all parameters are set, press and hold the “Press and Hold” button to begin stimulation; release it to stop.

Figure 2. A: main screen of the Medtronic console. Press “Tests” (arrow) to access the electrophysiology study screen. B: select “Fixed Burst” or “Burst” (arrow 1), adjust the interval as needed (arrow 2), and press and hold the “Burst” button (arrow 3) to deliver pacing.

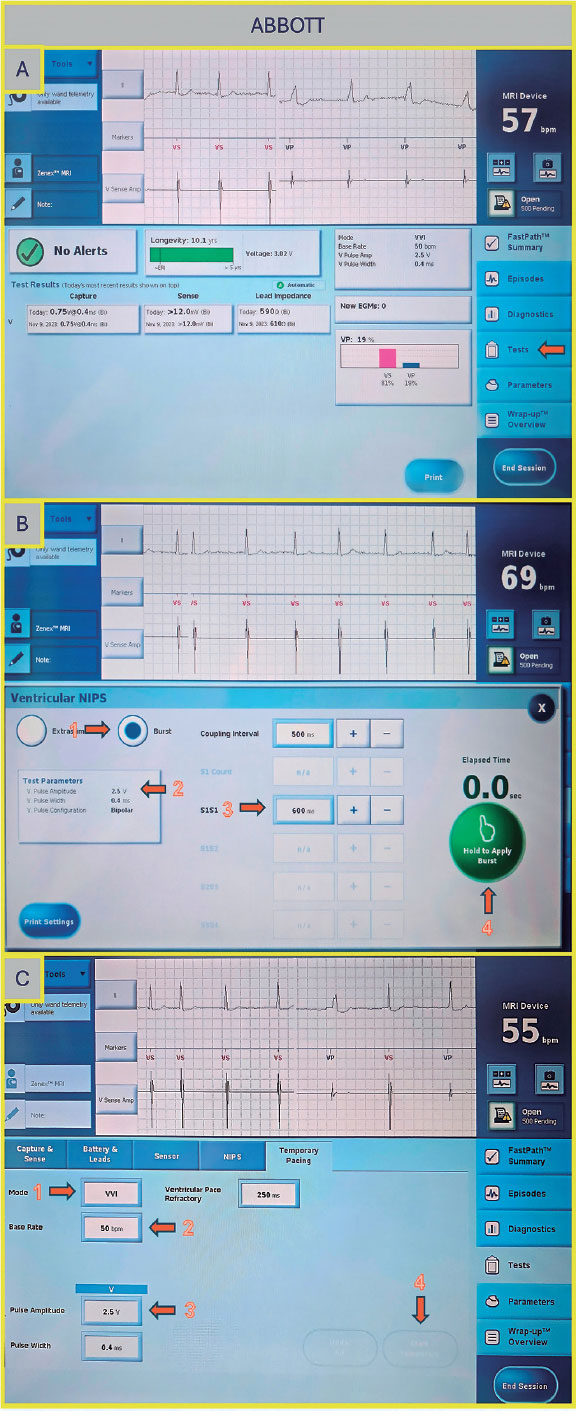

Abbott/St Jude (United States)

Once on the main screen (figure 3A), press “Test”. There are 2 options to perform rapid ventricular pacing:

- –NIPS (figure 3B): Click “Ventricular NIPS”, then select “Burst”, set the “Pulse Amplitude” (the output should be high to ensure capture), and adjust the pacing rate. In this case, the S1–S1 interval corresponds to the cycle length of the stimuli applied and must be set according to the desired heart rate. For example, 200 bpm corresponds to an S1–S1 interval of 300 ms.

- –Temporary pacing (figure 3C): Select the pacing mode (in this case, VVI), the desired rate (up to 170 bpm), and the maximum output to ensure capture. Once all parameters are set, press “Start Temporary” to begin pacing. Stimulation will continue until manually stopped.

Figure 3. A: main screen of the Abbott/St. Jude console. Press “Test” to proceed to the electrophysiology study screen. B: ventricular NIPS screen. Select “Burst” (arrow 1), set the amplitude (arrow 2), adjust the S1–S1 interval (arrow 3), and press the green button to deliver pacing (arrow 4). C: temporary pacing screen. Select the pacing mode (arrow 1), desired rate (arrow 2), and pulse amplitude (arrow 3), then press the “Start Temporary” button (arrow 4).

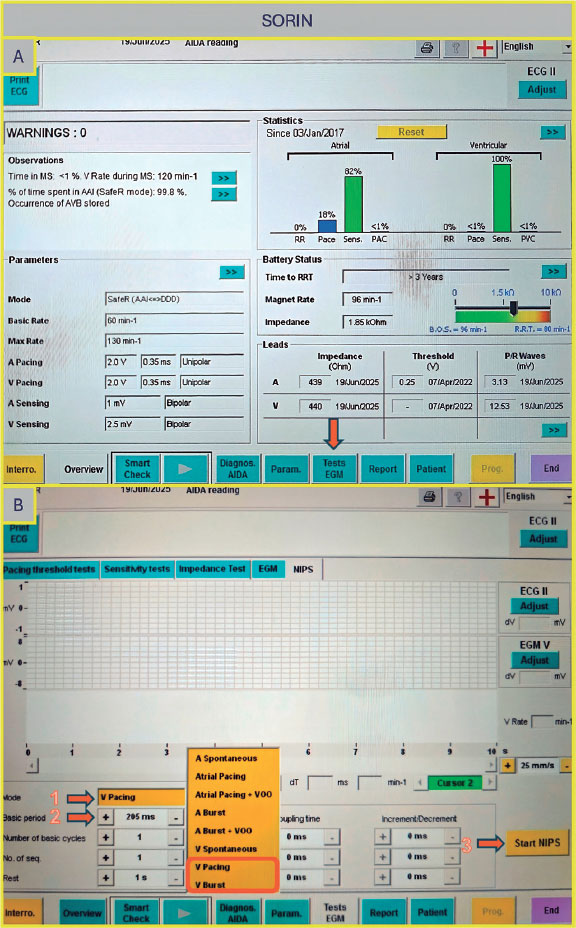

Sorin (Italy)

Select ”Tests”, then choose ”NIPS”. Under ”Mode”, select either ventricular pacing or ventricular burst, depending on the desired function. Next, set the ”Basic Period” (figure 4A,B) by choosing the corresponding rate in milliseconds (for example, 200 bpm corresponds to 300 ms). Once all parameters are set, press ”Start NIPS” to initiate the test.

Figure 4. A: main screen of the Sorin console. Select “Tests EGM” (arrow) to access pacing options. B: “Tests EGM” screen. Select the pacing mode (arrow 1), the interval period (arrow 2), and then press the “Start NIPS” button (arrow 3).

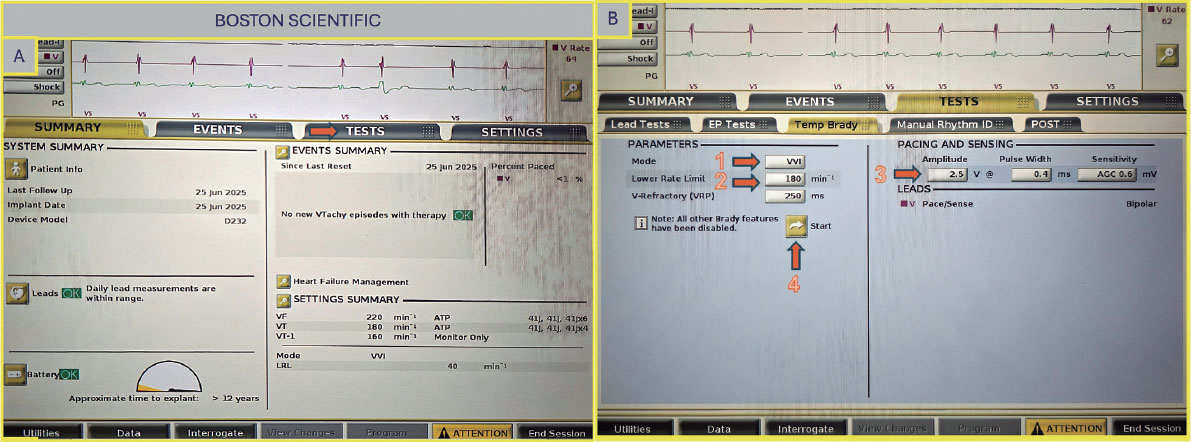

Boston Scientific (United States)

Once on the main screen (figure 5A), select “Test”, then choose “Temp Brady” (figure 5B) From there, select VVI mode and set the desired heart rate under “Lower Rate Limit.” As in previous cases, ensure that the maximum output is selected to guarantee proper capture. After all parameters have been configured, press the ”Start” button to begin.

Figure 5. A: main screen of the Boston Scientific console. Select “Test” (arrow) to proceed to the pacing setup. B: select VVI mode (arrow 1), set the lower rate limit (arrow 2) and amplitude (arrow 3), then press the “Start” button to begin pacing (arrow 4).

DISCUSSION

While earlier permanent pacing devices had limitations in achieving instantaneous burst pacing —such as ramping up the ventricular rate instead of immediate increase and requiring time to reset the function—contemporary devices have largely overcome these issues.14 Most current models allow rapid burst pacing up to 180 bpm with immediate start and stop, using electrophysiology program mode settings or whenever electrophysiology program is not available (especially in some pacemakers) via a threshold test with maximum output and maximum duration. In cases where this is not possible or does not ensure adequate rapid pacing, the placement of a temporary pacing lead should be considered. Table 1 lists several of the most widely used CIED in our routine clinical practice and specifies whether they provide the capability for rapid temporary pacing or electrophysiological testing). It is always required to ensure that any changes in device programming are reversed and individually optimized; therefore, verification of the device settings at the beginning of the procedure is recommended, and any changes or modifications at the end should be avoided. In patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator devices, tachyarrhythmia therapies should be deactivated before the procedure to avoid inappropriate shocks. Of note, some temporary pacing algorithms have a programmed duration limit, so it is essential to verify in advance that high-rate temporary pacing can be maintained for the entire time required for prosthesis deployment, as this may vary depending on the device and pacing mode used.

Table 1. Characteristics of the main cardiac implantable electronic devices.

| Manufacturer | VVI-Pacemaker (EP study available yes/no) | DDD-Pacemaker (EP study available yes/no) | VVI-Defibrillator (EP study available yes/no) | DDD-Defibrillator (EP study available yes/no) | CRT-Pacemaker (EP study available yes/no) | CRT-Defibrillator (EP study available yes/no) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biotronik | Ecuro SR (No) Enticos 4 SR (Yes) Edora 8 SR T (No) Evia SR T (Yes) Amvia Edge SR-T (Yes) Amvia Sky SR-T (Yes) |

Amvia Sky DR-T (No) Amvia Edge DR-T (Yes) Edora 8 DR-T (No) Evity 8 DR T (No) Ecuro DR (No) Effecta DR (Yes) Enticos 4 DR (Yes) Evia DR (Yes) Solvia Rise DR-T (no) |

Intica Neo 5 VRT (Yes) Iforia 3 VR-T (Yes) |

Iforia 3 DR-T (Yes) Inlexa 3 DR-T (Yes) Intica 5/7 (Yes) |

Edora 8 HF-T (Yes) Evia HF-T (Yes) Rivacor HF-T (Yes) Etrinsa 8 HF-T (Yes) |

Intica HF-T (Yes) Rivacor HF-T QP (Yes) |

| Boston Scientific | Essentio SR (Yes) Advantio SR (Yes) Accolade SR (Yes) |

Essentio DR (Yes) Advantio DR (Yes) Accolade DR (Yes) Ingenio (Yes) |

Charisma EL ICD (Yes) Inogen VR (Yes) Punctua NE ICD (Yes) Vigilant EL VR (Yes) Resonate VR (Yes) Autogen VR (Yes) Energen VR (Yes) |

Vigilant EL DR (Yes) Resonate (Yes) Energen (Yes) |

Intua (Yes) Visionist CRT-P (Yes) Valitude CRT-P (Yes) Invive (Yes) Accolate CRT-P (Yes) Incepta CRT-P (Yes) Essentio CRT-P (Yes) Resonate X4 CRT-P (Yes) |

Charisma CRT-D (Yes) Inogen CRT-D (Yes) Origen CRT-D (Yes) |

| Medtronic | Micra VR (No) Attesta SR (Yes) Sphera SR (Yes) Advisa SR (Yes) Ensura SR (Yes) Azure SR (Yes) |

Azure DR (Yes) Adapta DR (Yes) Advisa DR (Yes) Attesta DR (Yes) Ensura DR (Yes) Sphera DR (Yes) Sensia DR (Yes) Relia DR (Yes) |

Evera S VR (Yes) Maximo II VR (Yes/No) Protecta VR (Yes) Visia AF (Yes) Cobalt XT (Yes) |

Evera DR (Yes) Protecta DR (Yes) |

Serena CRT-P (Yes) Percepta CRT-P (Yes) |

Brava CRT-D (Yes) Compia CRT-D (Yes) Cobalt CRT-D (Yes) Claria CRT-D (Yes) |

| Sorin | Reply SR (Yes) Kora SR (Yes) |

Reply DR (Yes) Kora DR (Yes) Vega DR (Yes) |

Resiliant (Yes) Platinum SR (Yes) Intensia VR (Yes) Paradym SR (Yes) |

Platinum DR (Yes) Intensia DR (Yes) Paradym DR (Yes) |

Platinum CRT-P (Yes) Kora CRT-P (Yes) Luna CRT-P (Yes) Resiliant CRT-P (Yes) |

Platinum CRT-D (Yes) Paradym CRT-D (Yes) |

| Abbott/ St. Jude | Endurity Core (Yes) Assurity SR (Yes) Zephyr XL SR (Yes) |

Assurity DR (Yes) Accent DR (Yes) Endurity (Yes) Sustain XL DR (No) Verity ADx XL DR (No) |

Ellipse VR (Yes) Assura VR (Yes) Fortify Assura SR (Yes) Ellipse VR (Yes) Gallant VR (Yes) Neutrino (Yes) Entrant (Yes) |

Ellipse DR (Yes) Assura DR (Yes) Fortify Assura DR (Yes) Ellipse DR (Yes) Gallant DR (Yes) Neutrino DR (Yes) |

Quadra Allure CRT-P (Yes) Endurity CRT-P (Yes) Entrant CRT-P (Yes) Gallant CRT-P (Yes) |

Quadra Assura CRT-D (Yes) Unify Assura (Yes) CRT-D Fortify Assura CRT-D (Yes) Ellipse HF CRT-D (Yes) Entrant HF CRT-D (Yes) |

|

CRT, cardiac resynchronization therapy; CRT-P, cardiac resynchronization therapy pacemaker; CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator; DDD, dual-chamber pacing, dual-chamber sensing, and dual response to sensing; DR, dual chamber-rate; EP, electrophysiological; HF, heart failure; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators; SR, single rate; VVI, ventricular pacing, ventricular sensing, and inhibited response to a sensed event. |

||||||

Given the high ventricular rates required during this process and the deactivation of therapies in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillator or cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator devices, these maneuvers should be undertaken in a controlled environment with continuous monitoring, immediate availability of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and access to external defibrillation equipment.

Currently, temporary RV pacing remains a common clinical practice during TAVI in this patient subgroup despite growing evidence that pacing via an implanted CIED is safe and feasible and may reduce pacemaker-related complications, such as cardiac tamponade and hemorrhage vs temporary RV pacing.9,15 However, certain challenges may arise, mainly of an organizational nature. During TAVI, a manufacturer-specific CIED programmer must be available, and the operator responsible for pacing should be adequately trained on how to operate the device programming functions. Because programming options vary by manufacturer and device type, operators must have thorough and specialized knowledge. In addition, the presence of trained nurses with specific expertise is essential to support device programming and ensure procedural safety. These devices can deliver rapid ventricular pacing through anti-tachycardia pacing functions but programming them often requires adjusting more complex parameters. Our proposed strategy is simpler and more practical, especially for professionals less experienced with advanced device programming.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients undergoing TAVI with preexisting cardiac implantable electronic devices, leveraging the implanted device for procedural pacing is a feasible and potentially safer alternative to temporary RV pacing. This strategy may reduce the risk of complications such as perforation, lead dislodgement, and bleeding. However, its broader adoption is hindered by the variability in device programming interfaces and limited operator familiarity. The step-by-step instructions provided in this guide aim to facilitate the practical implementation of this approach across the most widely encountered CIED platforms, ultimately promoting safer, more efficient, and complication-free TAVI procedures.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

This is a step-by-step practical guide article; therefore, ethical committee approval was deemed unnecessary. No informed consent was required. Potential gender bias has been considered and excluded.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence has not been used in the development of this paper.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

F. Pensotti and L.J. Garnacho elaborated the manuscript under the supervision of I.J. Amat-Santos that revised and drafted the manuscript. All the remaining authors conducted a critical review. All authors approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Despite the fact that a substantial proportion of patients undergoing TAVI have a preexisting CIED, temporary pacing through these devices is rarely used. Instead, operators often prefer temporary RV pacing, which, however, carries inherent risks.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The step-by-step instructions of this guide are designed to help implement this approach on the most common CIED platforms, thereby ensuring safer, more efficient, and complication-free TAVI.

REFERENCES

1. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve replacement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1):a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:2477-2484.

2. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374: 1609-1620.

3. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients at Five Years. N Engl J Med. 2023;389: 1949-1960.

4. Forrest JK, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. 4-Year Outcomes of Patients With Aortic Stenosis in the Evolut Low Risk Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82: 2163-2165.

5. Tichelbäcker T, Bergau L, Puls M, et al. Insights into permanent pacemaker implantation following TAVR in a real-world cohort. PLoS One. 2018; 13:0204503.

6. Wasim D, Ali AM, Bleie Ø, et al. Prevalence and predictors of permanent pacemaker implantation in patients with aortic stenosis undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation:a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2025;15:093073.

7. Abdel-Wahab M, Mehilli J, Frerker C, et al. Comparison of Balloon-Expandable vs Self-expandable Valves in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement:The CHOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1503.

8. Axell RG, White PA, Giblett JP, et al. Rapid Pacing–Induced Right Ventricular Dysfunction Is Evident After Balloon-Expandable Transfemoral Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:903-904.

9. Feldt K, Dalén M, Meduri CU, et al. Reducing cardiac tamponade caused by temporary pacemaker perforation in transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Int J Cardiol. 2023;377:26-32.

10. Barbash IM, Dvir D, Ben-Dor I, et al. Prevalence and Effect of Myocardial Injury After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 111:1337-1343.

11. Tjong FVY, de Ruijter UW, Beurskens NEG, et al. A comprehensive scoping review on transvenous temporary pacing therapy. Neth Heart J. 2019;27: 462-473.

12. Hilling?Smith R, Cockburn J, Dooley M, et al Rapid pacing using the 0.035?in. Retrograde left ventricular support wire in 208 cases of transcatheter aortic valve implantation and balloon aortic valvuloplasty. Cathet Cardio Intervent. 2017;89:783-786.

13. Savvoulidis P, Mechery A, Lawton E, et al. Comparison of left ventricular with right ventricular rapid pacing on tamponade during TAVI. Int J Cardiol. 2022;360:46-52.

14. DAS MK, Dandamudi G, Steiner HA. Modern pacemakers:hope or hype?Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:1207-1221.

15. Haum M, Steffen J, Sadoni S, et al. Pacing Using Cardiac Implantable Electric Device During TAVR:10-Year Experience of a High-Volume Center. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:1020-1028.

ABSTRACT

The gender gap in interventional subspecialties is largely due to concerns about occupational radiation exposure. The belief that it is not possible to continue working in cath labs during pregnancy is perceived by many female physicians as a barrier to develop their career or fulfill their motherhood wishes. Many physicians are unaware of the doses of ionizing radiation that are harmful for the fetus, which is the dose received by women who continue to work in cath labs throughout their pregnancies, or do not know the existing regulations. The Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC), the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ARC-SEC), the Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (SERVEI), the Spanish Society of Neuroradiology (SENR), the Spanish Society of Medical Radiology (SERAM), and the Society of the Spanish Group of Interventional Neuroradiology (GeNI) consider it necessary to draft this informative document and joint position paper to provide female physicians with the necessary knowledge to make fully informed decisions on whether to choose an interventional subspecialty or work exposed to ionizing radiation during their pregnancy.

Keywords: Ionizing radiation. Occupational radiation. Pregnancy. Interventional subspecialty. Female physicians.

RESUMEN

La exposición a radiaciones ionizantes subyace en la brecha de género existente en subespecialidades intervencionistas. La creencia de que no es posible continuar trabajando en la sala durante el embarazo es percibida como un impedimento para el desarrollo profesional o para llevar a cabo los deseos genésicos. Muchas profesionales desconocen qué dosis de radiaciones ionizantes son deletéreas para el feto, cuál es la dosis recibida si se mantiene la actividad en la sala durante el embarazo y cuál es la normativa vigente. Desde la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (ACI-SEC), la Asociación del Ritmo Cardiaco de la Sociedad Española de Cardiología (ARC-SEC), la Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular e Intervencionista (SERVEI), la Sociedad Española de Neurorradiología (SENR), la Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica (SERAM) y la Sociedad del Grupo Español de Neurorradiología Intervencionista (GeNI) se considera necesario este documento informativo y de consenso, para proporcionar a las profesionales el conocimiento necesario para tomar decisiones plenamente informadas en cuanto a la elección o no de una subespecialidad intervencionista y la decisión de mantener o no una actividad con exposición a radiaciones ionizantes durante el embarazo.

Palabras clave: Radiación ionizante. Radiación ocupacional. Embarazo. Subespecialidad intervencionista. Profesionales mujeres.

Abbreviations

CSN: Spanish Nuclear Safety Council. EURATOM: European Atomic Energy Community. IR: ionizing radiation. RD: Royal Decree. RP: radiological protection.

INTRODUCTION

The percentage of women in subspecialties with exposure to ionizing radiation (IR) is significantly lower compared with men1-5 in a society where women largely outnumber men in medical schools. Only 25% of the members from the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ACI-SEC)6,7 are women, 28% of the members of the Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (SERVEI),8 and 34.5% of professionals accredited as electrophysiology specialists.9 Similarly, in other medical societies, such as the Society of the Spanish Working Group of Interventional Neuroradiology (GeNI), the percentage of women is even lower, currently at 22%.

One of the reasons for this gender gap is the belief that professional activity is incompatible with IR exposure during pregnancies.10-12 There is a lack of knowledge about the IR doses that have deleterious effects on the fetus, the dose received by a pregnant worker who remains active in the cath lab, and the current legislation on this issue. Furthermore, there is no homogeneity in occupational hazard prevention and radiological protection (RP) services across various health care centers when issuing recommendations on whether women are fit to continue working in an environment with IR exposure once pregnancy has been declared. Thus, in some centers, pregnant women can keep on working with IR exposure, while in others they are removed from their positions. On the other hand, women who decide to avoid working in an environment with IR exposure during pregnancy and change positions within their departments during gestation also face problems, as their career development and remuneration are altered during that period. In fact, they sometimes find little support when trying to come back to their pre-pregnancy job. The confusion, lack of information, and absence of unanimous criteria when determining the professional occupation of women during this period influence their decision to rule out training in these subspecialties and lead to their professional development being diminished or slowed down.

Therefore, ACI-SEC, the Heart Rhythm Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (ARC-SEC), the Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology (SERVEI), the Spanish Society of Neuroradiology (SENR), the Spanish Society of Medical Radiology (SERAM), and the GeNI Society have deemed it necessary to prepare this document, which is not only informative but also a consensus document on those IR doses that have demonstrated deleterious effects on the fetus, the average dosimetry received by a worker who remains active in the cath lab during pregnancy, what the Spanish current legislation actually says, and what advice and recommendations are considered reasonable for exposed professionals, in accordance with available scientific evidence and current regulations.

The objective of this document is to provide professionals with the necessary knowledge to make a fully informed decision on whether to choose an interventional subspecialty and continue with their job during gestation.

BIOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF IONIZING RADIATION ON THE FETUS

IR interferes with cell multiplication, especially in tissues with a high replication rate.13 Exposure to IR during the fetal period can lead to intrauterine growth restriction, malformations, tumors, and even fetal death. The risk depends on the magnitude and temporal distribution of the exposure, as well as the gestational age at which it occurs. Table 1 illustrates the IR-induced tissue reactions in the embryo or fetus, according to the gestational period, and the radiation threshold value.

Table 1. Tissue reaction to ionizing radiation in the embryo or fetus according to gestational period and threshold value

| Gestational period | Effect | Estimated radiation threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-implantation (0-2 weeks post-conception) | Embryo death or no effect | 50-100 mGy |

| Organogenesis (2-8 weeks) | Congenital malformations (skeletal, eyes, genitals) | 200 mGy |

| Growth retardation | 200-250 mGy | |

| 8-15 weeks | Severe intellectual disability (high risk of occurrence) | 60-310 mGy |

| Decrease in intellectual quotient | 20 IQ points/100 mGy | |

| Microcephaly | 200 mGy | |

| 16-25 weeks | Severe intellectual disability (low risk of occurrence) | 250-280 mGy |

|

Adapted with permission from Cheney et al.21. |

||

Radiation exposure, measured by the magnitude “absorbed dose” or kerma, is defined as the radiation energy received by an organ or tissue per unit mass and measured in milligray (mGy). The same absorbed radiation dose can cause a different biological effect depending on the ionizing agent emitting it, hence the term “equivalent dose,” which is the absorbed dose corrected by a weighting factor measured in millisievert (mSv). Since the radiation weighting factor for X-rays is 1, in this case, both the absorbed and the equivalent doses are numerically equal, with 1 mGy of absorbed dose being equal to 1 mSv of equivalent dose.14

IR can cause deleterious effects through deterministic and stochastic effects. The former have dose thresholds with intensity being proportional to the magnitude of the radiation. They are constant, reproducible, and related to moderate-to-high doses due to direct damage to multiple cell lines. The term “tissue reaction”15 is recommended as it better reflects the mechanism of damage and the dose-response relationship. The latter have no dose threshold, are caused by random damage to cellular genetic material, and show as growth and multiplication changes. Although a linear risk-exposure relationship with no minimum threshold is assumed, there is greater uncertainty surrounding this relationship at low dose levels (< 0.1 Gy).15 Their severity is independent of exposure.

General effects of radiation during the embryonic and fetal period

Evidence of these effects in humans comes from longitudinal studies of survivors of nuclear disasters, pregnant women exposed to medical or occupational radiation, and case-control studies of childhood leukemias and tumors.16 The only experimental studies have been conducted with animals.13 The magnitude of exposure is the main determinant of damage. Thus, irradiation at moderate-to-high doses can cause abortions, malformations, intellectual disability, and intrauterine growth restriction;17,18 at low doses, results are inconsistent. Damage varies depending on the stage of pregnancy. Within the first few weeks of gestation, there is greater radiosensitivity; each organ has critical weeks that are consistent with its organogenesis.19 As the fetus matures, the damage progressively decreases.18 Dose fractionation causes less damage than a single dose of the same intensity but shorter duration.18,20

Risk of fetal damage at moderate doses

Moderate doses are those between 100 mGy and 1 Gy. These have been recorded mainly in nuclear disasters and medical procedures, such as radiotherapy. These doses are not reached in the cath lab setting. Up to the 4th gestational week, doses of 0.1-0.2 Gy can be lethal.13,18 Doses > 2 Gy at any stage of pregnancy are associated with fetal death.21 This effect is an “all or nothing” phenomenon, where a sufficiently intense aggression can cause the death of the embryo or be completely repaired, given the high capacity for repair and differentiation of pluripotent cells.17 The threshold for the appearance of malformations stands between 1 Gy and 2 Gy,14 highlighting alterations in brain development, ocular, musculoskeletal, and genital systems. The most sensitive period corresponds to gestational weeks 8-25, followed by weeks 16-25. Fetal susceptibility decreases significantly after the 26th gestational week.20,22 Doses > 200 mGy have been associated with intrauterine growth restriction, low birth weight, shorter height, and decreased head circumference.20 Moreover, intellectual disability17 is associated with high doses of radiation. The central nervous system is especially radiosensitive during gestational weeks 8-25, specifically weeks 8-15, a period known as the “cortical sensitivity window”.13 Doses > 100 mGy are related to a decrease in intellectual quotient and risk of severe intellectual disability. This effect has been attributed to direct cell death and neuronal migration alterations. The high plasticity and redundancy of brain tissue could be the cause of the absence of effects below these doses. Doses < 100 mGy have not shown an association with fetal alterations or abortions.23

Risk of fetal damage at low doses

Low doses are those < 100 mSv, especially < 50 mSv. These doses can be reached in therapeutic procedures, while the doses involved in occupational exposures, living in regions of widespread environmental radiation, or frequently taking transatlantic flights are negligible. The appearance of tumors throughout life is their main stochastic effect, lacking safe minimum values.18,24 However, confirming this effect and estimating its magnitude present great methodological difficulties due to its low incidence rate, high latency, and low number of irradiated pregnant women.15 For this reason, results have been disparate.

Follow-up until 2012 of cohorts exposed to nuclear bombings found a higher mortality rate due to solid tumors only from adulthood in daughters of women exposed to this radiation, with an estimated mean dose received by these pregnant women of 123 mGy.25 This finding is only partially consistent with studies conducted in Europe after the Chernobyl accident, which only found a possible increase in thyroid tumors in uteri exposed to radioactive iodine release.26 Nonetheless, there was not an increased risk of childhood leukemia.27 In other nuclear accidents, studies of populations living close to nuclear facilities or nuclear test sites have not found any changes in the incidence rate of childhood cancer.15 Studies on occupational exposures have not demonstrated an increased risk of cancer after in utero exposures in the nuclear industry28 or medical radiology.29

Regarding the exposure of pregnant women to radiological tests, most are case-control studies. One of the main sources was the Oxford Survey of Childhood Cancer, from which the first studies emerged linking in utero exposure to childhood cancer.24 This research allowed for estimating a first absolute excess risk of cancer mortality of 500-650/10 000 people/year/Gy, updated to a relative risk excess of 51%/10 mGy for leukemia and 46%/10 mGy for other solid tumors.16 In 1982, data from these studies were used to estimate the probabilities of childhood cancer and malformations according to the exposure level (table 2). These values are the most widely used to this date.30

Table 2. Increased risk of malformations and childhood cancer according to received dose

| Embryo or fetus dose (mSv) | Absence of malformations (%) | Absence of childhood cancer (%) | Absence of malformations or childhood cancer (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 96.00 | 99.93 | 95.93 |

| 0.5 | 95.99 | 99.92 | 95.92 |

| 1 | 95.99 | 99.921 | 95.92 |

| 5 | 95.99 | 99.89 | 95.88 |

| 10 | 95.98 | 99.84 | 95.83 |

|

Adapted with permission from Wagner et al.30. The table was prepared assuming a dose increase above existing environmental radiation. |

|||

A review of the main studies found an association between in utero irradiation and leukemias or solid tumors, mainly in older cohorts.31 However, longitudinal studies with cohorts of pregnant women who underwent radiodiagnostic tests did not yield significant findings.32

Experimental studies with mice have found an increase in ovarian cancer with single doses of 0.25 Gy,33 and lymphoma with single doses of 0.18 Gy.34 Other studies, however, have not found changes to the incidence rate with doses of 2-3 Gy, except when these doses were administered after birth.35

EUROPEAN AND SPANISH LEGISLATION

The exposure of workers to IR is regulated by both national and international agencies. The European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) is a European public organization that coordinates nuclear energy research programs and develops regulations. These regulations are based on guidelines from the International Atomic Energy Agency, which, in turn, draws upon recommendations from the International Commission on Radiological Protection. The latter is an autonomous organization composed of experts in radiation protection. The European Union EURATOM treaty sets out the RP legislation that member states must adopt and transpose into their own national laws.

In Spain, the only competent organization in matters of nuclear safety and RP is the Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear, the Spanish Nuclear Safety Council (CSN), an independent entity of the Spanish General State Administration, which regulates the operation of nuclear and radioactive facilities, proposing regulations and standards. The instructions from the CSN become binding after publication in the Spanish Boletín Oficial del Estado (Official State Bulletin).

In 2013, the International Commission on Radiological Protection developed radiological protection (RP) guidelines for cardiology. These guidelines were subsequently adopted by EURATOM in Directive 2013/59.36 These guidelines and Article 10 of the EURATOM Directive state that pregnancy does not imply the exclusion of women from their job, but rather that working conditions must be carefully evaluated to ensure the safe limit of 1 mSv for the fetus throughout the pregnancy. This 1 mSv limit is established because it is considered that the protection of the fetus should be comparable to that of any person, who should not receive > 1 mSv in 1 year due to activities derived from the operation of nuclear and radioactive facilities. The transposition of European regulations in Spain is embodied in the form of Royal Decrees (RD). The RD applicable to the occupational exposure of pregnant workers are RD 298/200937 and RD 1029/2022.38 The former incorporated Annex VIII, which details a list of agents to which pregnant workers should not be at risk of exposure, including IR. This RD specifies that pregnant workers may not carry out activities that pose a risk of exposure to these agents if, according to the conclusions obtained from risk assessment, this may endanger their health or that of the fetus. Article 12 of RD 1029/2022 literally transposes Article 10 of the EURATOM Directive, establishing the same limit of 1 mSv during pregnancy. This RD repeals previous RD 783/2001 and 413/1997 on the protection of workers at risk of IR exposure, as well as all norms of equal or lower rank that contradict or oppose the provisions of this RD.

In 2016, the CSN approved the document “Protection of pregnant workers exposed to IR in the health care setting”39 specifying that, “as a general rule, the condition of pregnancy of an exposed professional does not imply her automatic withdrawal from work; what is necessary is to review her working conditions to comply with current regulations,” and that “pregnant workers may not carry out activities that involve a risk of exposure to IR if, according to the conclusions obtained in a risk assessment, there may be danger to their safety, their health, that of the child, or that of the fetus.” Furthermore, the document states that “from the moment a pregnant woman communicates her condition, the protection of the fetus must be comparable to that of the rest of the population. Therefore, the equivalent dose to the fetus must be as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA criteria),13 so that it is unlikely to exceed 1 mSv, at least from the communication of her condition until the end of her pregnancy.” Although this dose of 1 mSv is established for 1 cm depth, the actual depth at which the fetus is located is greater, and dose attenuation occurs due to the abdominal wall and the uterus. According to some models, the dose received by the fetus is 0.27% of that measured by the surface dosimeter during the first trimester, 0.23% during the second, and 0.17% during the third trimester. Thus, the CSN establishes that, in practice, the limit during pregnancy is 2 mSv on the abdominal dosimeter, or an equivalent dose received by the fetus of 1 mSv.14,40,41

MEANS OF PROTECTION VS IONIZING RADIATION

Exposure to IR requires RP measures for both patients and the health care personnel.42 Pregnant professionals must implement extraordinary measures.

Use of personal protective equipment

Lead aprons are a primary barrier that protects the organs most sensitive to radiation. They are designed to absorb and scatter radiation, significantly reducing the dose received by personnel. A lead apron, composed of a vest and skirt, with a lead thickness of 0.25 mm, is sufficient during gestation, as the overlap of the 2 layers of the skirt on the anterior abdominal wall provides protection equivalent to 0.5 mm, thus attenuating 98% of scattered radiation, which is the main source of radiation. As the abdomen grows, a larger apron should be used to ensure the double layer on the anterior abdominal wall. There are specific aprons for pregnant women that add an extra layer to the double layer of the skirt on the anterior abdominal wall. During the first trimester, 0.5 mm lead gonad shields can be internally attached to the lead skirt14,43,44. Although adding additional skirts or aprons would minimally reduce radiation, it could lead to musculoskeletal problems. Both during gestation and lactation, complete breast protection must be ensured, as breast tissue is particularly radiosensitive; for this, aprons of the appropriate size for each worker should be used, avoiding uncovered areas in the axillary region that could expose the breasts.

Training and continuous education in RP

Health care personnel must be aware of the risks and available protective measures. Working as far as possible from the radiation source, raising the table as much as possible, and being as efficient as possible with emitted radiation doses are basic measures in any circumstance. If feasible, pregnant workers should avoid participating in long procedures, due to both IR exposure and prolonged static standing. Similarly, since the embryo or fetus is more radiosensitive within the first gestational weeks, it is reasonable to abstain from participating in examinations with IR exposure during the first trimester.

The design of the work environment is critical. Cath labs must be equipped with lead barriers and protective screens to minimize exposure and reduce the amount of scattered radiation. They are an indispensable protective tool during pregnancy, as they attenuate 99% of scattered radiation and reduce overall radiation exposure by 50%-75%.43,45,46

Finally, monitoring radiation exposure is an essential measure. Personal dosimeters allow continuous monitoring of the received radiation dose and record cumulative exposure. They ensure that doses remain within the limits established by regulations and help identify risk situations that require corrective measures. The history of each worker’s cumulative exposure helps identify trends. In the case of pregnant women, there are dosimeters with real-time readings45,47 that allow confirming that the permitted dosimetry is not exceeded, both monthly and at any given time. The personal dosimeter must be changed monthly and worn in the appropriate place; for the abdominal dosimeter, it will be under the lead apron to record the equivalent dose received beneath it. Incorrect use of the dosimeter prevents RP services from evaluating the dose the worker receives in her usual work and, consequently, whether she can continue working during pregnancy.

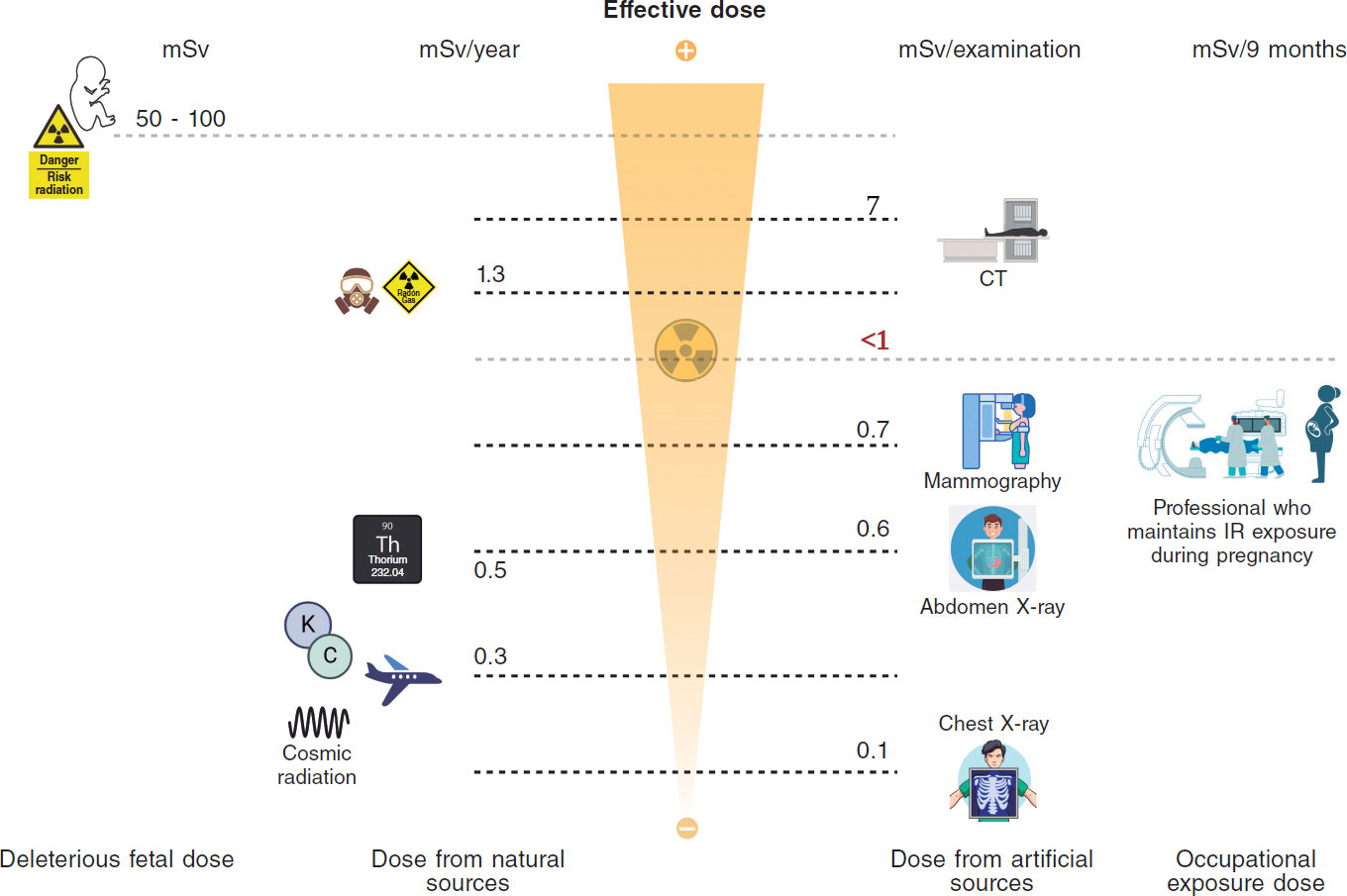

BACKGROUND RADIATION, OTHER DAILY LIFE RADIATIONS, AND OCCUPATIONAL DOSE

Understanding the doses received by the population allows for putting occupational doses into perspective. The average annual exposure to background radiation ranges between 1 mSv and 2.3 mSv;14 this radiation comes from radon in the air, cosmic radiation from space, and natural radioactivity in soil and building materials. Radon is a radioactive gas emitted by soil and rocks that accounts for 50% of a person’s annual radiation dose, approximately 1.3 mSv.48 Radioactive materials from the Earth’s crust, such as uranium, thorium, and potassium, represent an average annual exposure of 0.5 mSv. Cosmic radiation, from high-energy particles from outer space that penetrate the atmosphere, represents an average annual exposure of about 0.3 mSv at sea level. On a long-haul flight, the average radiation is about 0.003-0.0097 mSv/h.49 Internal radiation from radioactive isotopes in food and water, such as potassium-40 and carbon-14, generates an average absorbed radiation dose of 0.3 mSv per year.50,51 Background radiation varies depending on the area where one lives; for example, in some places in Galicia (Spain), 1.45 mSv of annual environmental radiation is reached.52 Considering these data and the dosimetric information of workers who have maintained their activity in the cath lab during pregnancy, the occupational dose received during pregnancy can be even lower than the dose received as a result of background radiation.25-27,53,54 Similarly, a round-trip transatlantic flight can expose a person to 0.1 mSv due to cosmic radiation at high altitude. This IR dose is similar to that of a chest X-ray and greater than the doses received by most interventional women who keep working in the cath lab throughout pregnancy45 (figure 1).

Figure 1. Central illustration. Comparison between ionizing radiation doses causing stochastic or deterministic effects in the fetus, doses due to natural or medical radiation sources, and occupational doses.14 (Created with BioRender.) CT, computed tomography; IR, ionizing radiation; Rx, X-rays.

Regarding occupational doses, the periodic reports issued by the CSN provide information on the dose received by workers exposed to IR in Spain. According to these reports, in 2023, 127 234 workers in Spain were dosimetrically controlled,55 of whom 96% received < 1 mSv, with 0.6 mSv/year being the average dose received by workers in medical radiodiagnostic centers. Even so, to make an informed decision, we need to know the doses received by interventional women who continue working in the cath lab during pregnancy. Table 3 illustrates the doses reported through questionnaires or direct interviews with women who continued working in the cath lab during pregnancy; although this information is very limited due to the small number of exposed pregnant workers, the doses registered on abdominal dosimeters are < 1 mSv in all cases.12,43,45

Table 3. Published data on occupational doses of pregnant workers with ionizing radiation exposure

| Country | No. of pregnancies/No. of interventional workers | Protection used | Dose received during gestation | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spain | 15 pregnancies / 11 interventional cardiologists or electrophysiologists | Standard vest + skirt (7/15) Extra skirt or additional gonadal protection (8/15) | Background dose (8/15) 0.2 mSv (2/15) < 1 mSv (3/15) Not reported (2/15) | 14/15 normal gestations 1/15 placental insufficiency |

| France | 8 pregnancies / 5 interventional cardiologists or electrophysiologists | Standard vest + skirt (5/8) Additional mobile protective screen (3/8) | Background dose (7/8) 0.2 mSv (1/8) | 8/8 normal gestations |

| New Zealand | Isolated cases of pregnancies in interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists | Information not available in the study | Monthly monitoring described with abdominal dosimeter clearly below the dose threshold | All gestations reported as normal |

| Australia | 21 pregnancies / 11 interventional cardiologists or electrophysiologists | 2 pregnancies left the cath lab for 6-9 weeks | Monthly monitoring described with abdominal dosimeter clearly below the dose threshold | Outcomes reported as comparable to those of the non-exposed population |

However, the dose received by a worker depends on the number and type of procedures performed, whether she is the primary operator, the patient’s body mass, the fluoroscopy-cine time, technical aspects of the X-ray machine, and the radiation protection measures adopted. Therefore, if the worker decides to keep on working in the cath lab during pregnancy, the received dose can be reduced by modifying usual activity, keeping it as low as possible, below the maximum permitted by the current legislation. Regarding on-call duties, when deciding whether to continue performing them during gestation, the worker should take into consideration that most procedures performed during these will be therapeutic, and some of them can be prolonged, leading to greater exposure and long periods of standing.

DISCUSSION

One of the duties of scientific societies is to respond to the problems and concerns of the professionals they represent promoting initiatives that reduce gender bias in the workplace. According to surveys and published works, occupational exposure to IR is one of the reasons that lead to a gender bias in subspecialties such as interventional cardiology, electrophysiology, or interventional radiology.1,56 The belief that pregnant workers cannot perform activities with occupational IR exposure causes professionals to perceive difficulties in these subspecialties in reconciling professional development with motherhood, which leads them to self-exclude. However, considering the review of doses that have demonstrated biological effects on the fetus25-27,53,54, there is no risk of abortion with received doses < 50 mSv, nor risk of deterministic effects, such as malformations or intellectual disability with doses < 60 mSv.18,23 We should remember that the rate of early spontaneous abortion in pregnancies known to women is 10%-20%,57 which is a multifactorial event. Regarding stochastic effects, there is no evidence either of a higher risk with doses < 50 mSv.15,27

Occupational exposure to IR during pregnancy is regulated in Europe by directives that take into consideration the recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection. In Spain, the regulations governing the dose that the fetus can receive due to the mother’s occupational activity during pregnancy are included in several RD and have been developed following the recommendations made by the CSN.37-39 The fetus is considered a member of the general population and, like anyone else, cannot receive > 1 mSv/year. This postulate is one of the most conservative ones, since the International Commission on Radiological Protection establishes this limit of 1 mSv for the fetus, and the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements establishes a threshold limit for the fetus of 5 mSv.58 This is so because, in the United States, employers prioritize the rights of pregnant workers from an anti-discrimination perspective, while European legislation policies prioritize fetal safety. Australia and Israel set the bar at 1 mSv throughout pregnancy too, and Japan sets a threshold limit of 2 mSv.45

Both deterministic and stochastic effects present a threshold for onset several orders of magnitude higher than occupational doses. Furthermore, they are very far from the doses received by professionals who have kept on working in the lab during pregnancy, since in none of the published works has the received dose been > 1 mSv.45 Table 2 illustrates the spontaneous risk of congenital malformations in newborns (4%) and the spontaneous probability of a child developing cancer in childhood (0.07%). The increase in the probability that the fetus will have a malformation at birth or develop cancer in childhood if it receives 1 mSv during gestation would be 0.008% above the spontaneous risk, that is, an extremely low increase in risk.30

In Europe, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, and Romania have not transposed the EURATOM directive into their own legislations and do not allow women to work in the lab during pregnancy.45 Furthermore, in Spain, the occupational risk prevention and RP services of some centers, in full compliance with Annex VIII of the 2009 RD,37 declare the worker “unfit” to keep on working during pregnancy. However, this measure would not be justified for several reasons. Firstly, because the 2009 RD specifies that a pregnant worker may not carry out activities that pose a risk of exposure if, according to the conclusions obtained from the risk assessment, this may endanger her safety or health or that of the fetus, which is not the case if the dose threshold of 1 mSv is respected. Secondly, because the 2022 RD establishes that the working conditions of pregnant women shall be such that the equivalent dose to the fetus should be as low as reasonably achievable, in such a way that the dose does not exceed 1 mSv, at least since the worker communicated her condition until the end of pregnancy, which implies that it is possible to continue working during pregnancy if said limit is not exceeded. A third reason would be that, as stated in the health surveillance guide for occupational risk prevention prepared by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer and Social Welfare, the preferred way to communicate the results of health surveillance, from an occupational risk prevention perspective, is in the form of preventive recommendations.59 This document only considers that the qualification of “unfit” should be applied when there is a high probability of harm to the health of the worker or to any third parties and workplace adaptation is not possible, recommending in all other cases the qualification of “fit with adaptation measures”.59 As we have seen, in the case of occupational exposure to IR, the probability of harm to the health of third parties (fetus) is not high, since occupational doses are < 1 mSv. Moreover, workplace adaptation is possible by providing the worker with an abdominal dosimeter, even with real-time reading, to closely monitor the dose received, thus increasing protection with a specific lead apron for pregnant women or with gonadal shields, and even excluding the pregnant woman from procedures associated with high IR doses, while preserving her usual activity in the cath lab. Therefore, the qualification that should be given to workers exposed to IR when they become pregnant is “fit with adaptation measures”.59

Of note that declaring a professional “unfit” to perform her job during pregnancy removes her from her usual work environment interrupting her working projects and procedures in which she is involved. Furthermore, sometimes after pregnancy and maternity leave, women are not easily reintegrated into the professional projects they were developing in their departments before gestation. All this constitutes a situation of workplace inequality, a slowdown in professional development, and a loss of opportunities compared with their male colleagues, an unjustified prejudice if we adhere to the scientific evidence and current Spanish legislation.

Therefore, greater efforts must be made by scientific societies, the CSN, and the Spanish Ministry of Health to promote the dissemination of knowledge about the deleterious effects of IR, the doses that cause them, and the doses to which pregnant women with occupational exposure are exposed. Initiatives are needed to recognize, make visible, and solve the difficulties these professionals face. It’s also crucial to engage officials at the Spanish Ministry of Labor, as they oversee occupational risk prevention services. The goal is to raise awareness about the need for clearer regulations regarding pregnant professionals in laboratory settings. This would eliminate any ambiguity about their legal permission to continue working, provided the radiological protection department approves based on their dosimetry history.

In any case, when making a decision in this regard, we should remember that information on the dose received by workers who kept working in the cath lab during pregnancy comes from a small number of interventional cardiologists and electrophysiologists, and that information comes only from surveys and observational data. Of note, there are few studies on the health of the offspring of women who have maintained activity with IR exposure during pregnancy, and the available data are not consistent due to the small number of irradiated women and the low incidence and high latency of the effects. Similarly, the value of 1 mSv should not be considered a strict regulatory threshold; what should be attempted is that, once the worker has notified the pregnancy, her working conditions are such that it is unlikely that the fetus will receive a dose > 1 mSv during the remainder of the pregnancy.

The decision to keep on working in the cath lab and performing on-call duties during pregnancy must be made freely by the worker after consulting with her health care professionals, and based on scientific information, her dosimetric history, her physical and emotional state, and the correct use of RP measures. This choice can have both physical (exposure to unwanted doses of ionizing radiation or musculoskeletal discomfort from wearing a lead apron) and emotional implications. Of note, 10%-20% of pregnancies end in spontaneous abortion, due to mostly multifactorial and often unknown causes, not necessarily attributable to occupational radiation exposure per se. This situation can lead to a feeling of “retrospective guilt,” as can the possible appearance of medical problems in the fetus or child, even if there is no scientific evidence linking said condition to occupational exposure. Therefore, it is a reality that making the decision involves a great silent emotional burden and a significant internal conflict and must be free from external pressures and accompanied by adequate emotional support for all pregnant women, whatever their decision.

Since the current legislation allow pregnant workers to continue in their workplace as long as dose limits are respected, while contemplating the possibility of requesting a workplace adaptation without radiation exposure, it is essential to preserve each woman’s freedom of decision, preventing her from being removed from the cath lab against her will and ensuring, in all cases, a safe and understanding working environment. For those who choose not to be exposed to radiation during gestation, it is crucial to facilitate not only workplace adaptation but also full reintegration into their previous job and projects after maternity leave, including training in techniques that may have been incorporated during their absence.

Promoting this flexibility and institutional support is key to preventing sex discrimination and attracting and retaining female talent in interventional subspecialties where women are still a minority. Occupational radiation should not be perceived as a factor incompatible with pregnancy per se, but rather as a manageable circumstance based on autonomy, knowledge, fetal safety, and respect.

CONCLUSIONS

The fear of IR effects on the fetus is one of the reasons many female workers dismiss training in an interventional subspecialty. However, both the European directive and current Spanish law state that pregnant women should not be excluded from their jobs, provided the fetus is protected like any other individual and its maximum occupational radiation dose during gestation does not exceed 1 mSv.

The doses received by professionals who maintain their activity with IR exposure during pregnancy do not exceed the 1 mSv limit in any of the published studies, placing them at an order of magnitude 50 or 100 times lower than those that have demonstrated deleterious effects on the fetus. Abdominal dosimeters allow close monitoring of the doses received by workers with occupational IR exposure, ensuring that the limit established by regulations is not exceeded. Therefore, according to the CSN, any worker with occupational IR exposure, under working conditions where it is improbable that the fetus will receive a dose > 1 mSv, can feel safe in her workplace as long as she responsibly abides by the recommendations of the RP department and correctly uses the abdominal dosimeter.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Since this is not an experimental work, but a review and opinion article, it has been deemed unnecessary to consider international recommendations on clinical research or submit it to the ethical committees of the centers of the corresponding authors. Since this is not a study conducted with patients informed consent was deemed unnecessary as well. An analysis of possible sex and gender biases is not applicable because it focuses only on female workers and occupational exposure to IR during pregnancy.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Velázquez Martín, S. Lojo Lendoiro, B. Cid Álvarez, and T. Bastante Valiente contributed to the conception and design of the study. M. Velázquez Martín, S. Lojo Lendoiro, Nina Soto, T. Bastante Valiente, and B. Cid Álvarez contributed to the drafting of the text. All authors critically reviewed the intellectual content of this manuscript and gave their final approval to the version published. Similarly, all authors take full responsibility for all aspects of the article and commit themselves to investigating and resolving any issues related to the accuracy and veracity of any part of the work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

REFERENCES

1. Manzo-Silberman S, Piccaluga E, Radu M, et al. Radiation protection measures and sex distribution in European interventional catheterisation laboratories. EuroIntervention. 2020;16: 80-82.

2. Abdulsalam N, Gillis AM, Rzeszut AK, et al. Gender Differences in the Pursuit of Cardiac Electrophysiology Training in North America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78: 898-909.

3. Wang TY, Grines C, Ortega R, Dai D, Jacobs AK, Skelding KA, et al. Women in interventional cardiology: Update in percutaneous coronary intervention practice patterns and outcomes of female operators from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry®. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87: 663-668.

4. Burgess S, Shaw E, Ellenberger K, Thomas L, Grines C, Zaman S. Women in Medicine: Addressing the Gender Gap in Interventional Cardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72: 2663-2667.

5. Tamirisa KP. Women and cardiac electrophysiology as a career path. Heart Rhythm Case Rep. 2023;9: 267.

6. Cid Álvarez AB. Mujer, cardiología y subespecialidades intervencionistas. REC: CardioClinics. 2022;58: 70-71.

7. Bastante T, Arzamendi D, Martín-Moreiras J, et al. Spanish cardiac catheterization and coronary intervention registry. 33rd official report of the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology (1990-2023). Rev Esp Cardiol. 2024;77: 936-946.

8. Lojo Lendoiro S, Moreno Sánchez T. Radiación ocupacional y embarazo: realidad o desinformación. Revisión en la literatura y actualización según guías clínicas vigentes. Radiologia. 2022;64: 128-135.

9. Portwood Cl. Reasons and resolutions for gender inequality among cardiologists and cardiology trainees. Br J Cardiol. 2023;30: 13.

10. Capranzano P, Kunadian V, Mauri J, et al. Motivations for and barriers to choosing an interventional cardiology career path: results from the EAPCI Women Committee worldwide survey. EuroIntervention. 2016;12: 53-59.

11. Buchanan G, Ortega R, Chieffo A, Mehran R, Gilard M, Morice MC. Why stronger radiation safety measures are essential for the modern workforce. A perspective from EAPCI Women and Women as One. EuroIntervention. 2020;16: 24-25.

12. Adeliño R, Malaczynska-Rajpold K, Perrotta L, et al. Occupational radiation exposure of electrophysiology staff with reproductive potential and during pregnancy: an EHRA survey. Europace. 2023;25: euad216.

13. Valentin J. Biological effects after prenatal irradiation (embryo and fetus): ICRP Publication 90 Approved by the Commission in October 2002. Ann ICRP. 2003;33: 1-206.

14. Saada M, Sanchez-Jimenez E, Roguin A. Risk of ionizing radiation in pregnancy: just a myth or a real concern?Europace. 2022;25: 270-276.

15. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. Report No. 174 –Preconception and Prenatal Radiation Exposure: Health Effects and Protective Guidance (2013). Bethesda, MD: NCRP;January 30, 2018. Available at: https://ncrponline.org/shop/reports/report-no-174-preconception-and-prenatal-radiation-exposure-health-effects-and-protective-guidance-2013/. Accessed 13 Jul 2024.

16. Wakeford R, Bithell JF. A review of the types of childhood cancer associated with a medical X-ray examination of the pregnant mother. Int J Radiat Biol. 2021;97: 571-592.

17. National Research Council (US) Committee on the Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR V). Health Effects of Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation: Beir V. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US);1990.

18. Brent RL. Saving lives and changing family histories: appropriate counseling of pregnant women and men and women of reproductive age, concerning the risk of diagnostic radiation exposures during and before pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200: 4-24.

19. De Santis M, Cesari E, Nobili E, Straface G, Cavaliere AF, Caruso A. Radiation effects on development. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today: 2007;81: 177-182.

20. Valentin J, ed. Pregnancy and Medical Radiation. Oxford: Pergamon Press;2000.

21. Cheney AE, Vincent LL, McCabe JM, Kearney KE. Pregnancy in the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory: A Safe and Feasible Endeavor. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14: e009636.

22. Ikenoue T, Ikeda T, Ibara S, Otake M, Schull WJ. Effects of environmental factors on perinatal outcome: neurological development in cases of intrauterine growth retardation and school performance of children perinatally exposed to ionizing radiation. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101(Suppl 2): 53-57.

23. Mainprize JG, Yaffe MJ, Chawla T, Glanc P. Effects of ionizing radiation exposure during pregnancy. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2023;48: 1564-1578.

24. Stewart A, Webb J, Giles D, Hewitt D. Malignant disease in childhood and diagnostic irradiation in utero. Lancet. 1956;268: 447.

25. Sugiyama H, Misumi M, Sakata R, Brenner AV, Utada M, Ozasa K. Mortality among individuals exposed to atomic bomb radiation in utero: 1950–2012. Eur J Epidemiol. 2021;36: 415-428.

26. Hatch M, Brenner AV, Cahoon EK, et al. Thyroid Cancer and Benign Nodules After Exposure In Utero to Fallout From Chernobyl. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;104: 41-48.

27. Parkin DM, Clayton D, Black RJ, et al. Childhood leukaemia in Europe after Chernobyl: 5 year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 1996;73: 1006-1012.

28. Roman E, Doyle P, Ansell P, Bull D, Beral V. Health of children born to medical radiographers. Occup Environ Med. 1996;53: 73-79.

29. Johnson KJ, Alexander BH, Doody MM, et al. Childhood cancer in the offspring born in 1921–1984 to US radiologic technologists. Br J Cancer. 2008;99: 545-550.

30. Wagner LK, Hayman LA. Pregnancy and women radiologists. Radiology. 1982;145: 559-562.

31. Little MP, Wakeford R, Bouffler SD, et al. Cancer risks among studies of medical diagnostic radiation exposure in early life without quantitative estimates of dose. Sci Total Environ. 2022;832: 154723.

32. Doll R, Wakeford R. Risk of childhood cancer from fetal irradiation. Br J Radiol. 1997;70: 130-139.

33. Uma Devi P, Hossain M. Induction of solid tumours in the Swiss albino mouse by low-dose foetal irradiation. Int J Radiat Biol. 2000;76: 95-99.

34. Benjamin SA, Lee AC, Angleton GM, Saunders WJ, Keefe TJ, Mallinckrodt CH. Mortality in beagles irradiated during prenatal and postnatal development. II. Contribution of benign and malignant neoplasia. Radiat Res. 1998;150: 330-348.

35. Ellender M, Harrison JD, Kozlowski R, Szłuin´ska M, Bouffler SD, Cox R. In utero and neonatal sensitivity of ApcMin/+mice to radiation-induced intestinal neoplasia. Int J Radiat Biol. 2006;82: 141-151.

36. Directiva 2013/59/Euratom del Consejo, de 5 de diciembre de 2013, por la que se establecen normas de seguridad básicas para la protección contra los peligros derivados de la exposición a radiaciones ionizantes, y se derogan las Directivas 89/618/Euratom, 90/641/Euratom, 96/29/Euratom, 97/43/Euratom y 2003/122/Euratom. Available at: https://www.boe.es/doue/2014/013/L00001-00073.pdf. Accessed 24 Nov 2024.

37. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Disposiciones generales. Ministerio de la Presidencia. 7 de marzo de 2009, núm. 57, sec. I. Pág. 23288. Available at: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2009/03/07/pdfs/BOE-A-2009-3905.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2024.

38. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Disposiciones generales. Ministerio de la Presidencia, Relaciones con las Cortes y Memoria Democrática. 21 de diciembre de 2022, núm. 305, sec. I. Pág. 178672. Real Decreto 1029/2022, de 20 de diciembre, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento sobre protección de la salud contra los riesgos derivados de la exposición a las radiaciones ionizantes. Available at: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rd/2022/12/20/1029/dof/spa/pdf. Accessed 24 Nov 2024.

39. Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear. Protección de las trabajadoras gestantes expuestas a radiaciones ionizantes en el ámbito sanitario. Available at: https://www.csn.es/documents/10182/914805/Protecci%C3%B3n%20de%20las%20trabajadoras%20gestantes%20expuestas%20a%20radiaciones%20ionizantes%20en%20el%20%C3%A1mbito%20sanitario%20(Actualizaci%C3%B3n%202024). Accessed 13 Jul 2024.

40. Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear. Requisitos técnicos-administrativos para los servicios de dosimetría personal. Available at: https://www.csn.es/documents/10182/896572/GS+07-01+Revisi%C3%B3n+1+-+Requisitos+t%C3%A9cnico-administrativos+para+los+servicios+de+dosimetr%C3%ADa+personal+(Febrero+2006)/dfe4292b-7792-45fc-ba67-b16302e19c64?version=1.4. Accessed 13 Jul 2024.

41. Damilakis J, Perisinakis K, Theocharopoulos N, et al. Anticipation of Radiation Dose to the Conceptus from Occupational Exposure of Pregnant Staff During Fluoroscopically Guided Electrophysiological Procedures. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2005;16: 773-780.

42. Vu CT, Elder DH. Pregnancy and the Working Interventional Radiologist. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2013;30: 403-407.

43. Velázquez M, Pombo M, UnzuéL, Bastante T, Mejía E, Albarrán A. Radiation Exposure to the Pregnant Interventional Cardiologist. Does It Really Pose a Risk to the Fetus?Rev Esp Cardiol. 2017;70: 606-608.

44. Marx MV. Baby on Board: Managing Occupational Radiation Exposure During Pregnancy. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;21: 32-36.

45. Manzo-Silberman S, Velázquez M, Burgess S, et al. Radiation protection for healthcare professionals working in catheterisation laboratories during pregnancy: a statement of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI), the ESC Regulatory Affairs Committee and Women as One. EuroIntervention. 2023;19: 53-62.

46. Miller DL, VañóE, Bartal G, et al. Occupational Radiation Protection in Interventional Radiology: A Joint Guideline of the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe and the Society of Interventional Radiology. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33: 230-239.

47. Poudel S, Weir L, Dowling D, Medich DC. Changes in Occupational Radiation Exposures after Incorporation of a Real-time Dosimetry System in the Interventional Radiology Suite. Health Physics. 2016;111: S166.

48. Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear. Mapa del potencial de radón en España. Available at: https://www.csn.es/mapa-del-potencial-de-radon-en-espana. Accessed 13 Oct 2024.

49. Bottollier-Depois JF, Chau Q, Bouisset P, Kerlau G, Plawinski L, Lebaron-Jacobs L. Assessing exposure to cosmic radiation on board aircraft. Adv Space Res. 2003;32: 59-66.

50. Ortega García JA, Ferrís i Tortajada J, OrtíMartín A, et al. Contaminantes medio-ambientales en la alimentación. An Esp Pediatr. 2002;56: 69-76.

51. Diario Oficial de las Comunidades Europeas. 22/07/1989. N.ºL 211/1. Reglamento (EURATOM) N.º2218/89 del Consejo de 18 de julio de 1989. Available at: https://www.boe.es/doue/1989/211/L00001-00003.pdf. Accessed 13 Oct 2024.

52. Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear. Mapa de radiación gamma natural en España (MARNA) MAPA. Available at: https://www.csn.es/mapa-de-radiacion-gamma-natural-marna-mapa. Accessed 4 Jan 2025.

53. Hatch M, Brenner A, Bogdanova T, et al. A Screening Study of Thyroid Cancer and Other Thyroid Diseases among Individuals Exposed in Utero to Iodine-131 from Chernobyl Fallout. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94: 899-906.

54. Stewart A, Barber R. Survey of childhood malignancies. Public Health Rep (1896). 1962;77: 129-139.

55. Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear. Informe del Consejo de Seguridad Nuclear al Congreso de los Diputados y al Senado. Año 2023. Available at: https://www.calameo.com/read/006700665a458974bd45d. Accessed 8 Apr 2025.

56. Bernelli C, Cerrato E, Ortega R, et al. Gender Issues in Italian Catheterization Laboratories: The Gender-CATH Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10: e017537.

57. Benson LS, Holt SK, Gore JL, et al. Early Pregnancy Loss Management in the Emergency Department vs Outpatient Setting. JAMA Network Open. 2023;6: e232639.

58. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. NCRP Report No. 174, Preconception and Prenatal Radiation Exposure: Health Effects and Protective Guidance. Bethesda, MD: NCRP;June 1, 2015. Available at: https://ncrponline.org/publications/reports/ncrp-report-174/. Accessed 13 Jul 2024.

59. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Vigilancia de la salud para la prevención de riesgos laborables. Guía básica y general de orienta-ción. Available at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/ciudadanos/saludAmbLaboral/docs/guiavigisalud.pdf. Accessed 19 Jul 2024.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail addresses: ; (M. Velázquez Martín).

@maitevelazquezm;

@shci_sec;

@SERVEISoc;

@saralojo86;

@Geni_NRI;

@ritmo_SEC;

@SERAM_RX;

@SENR_ORG

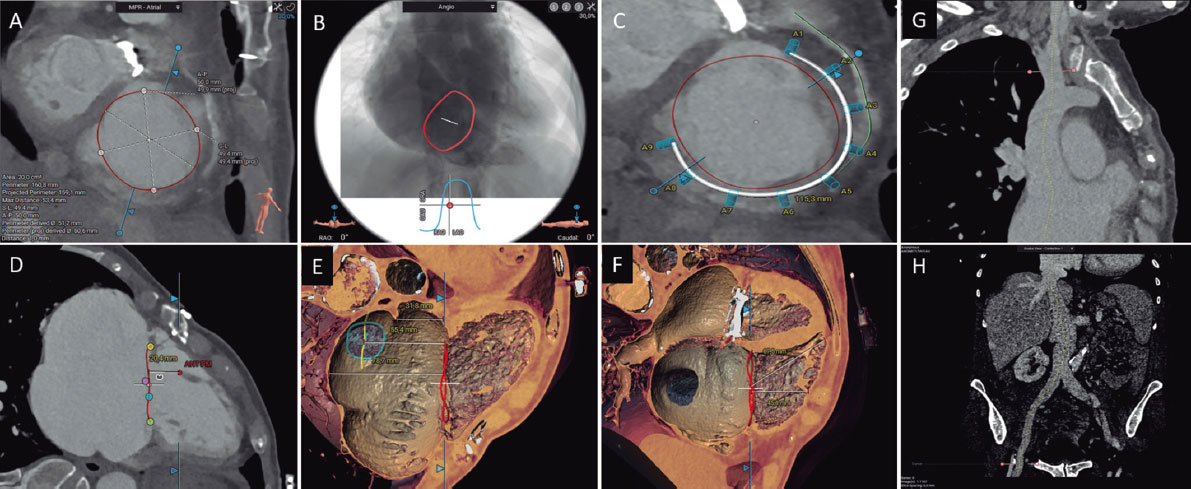

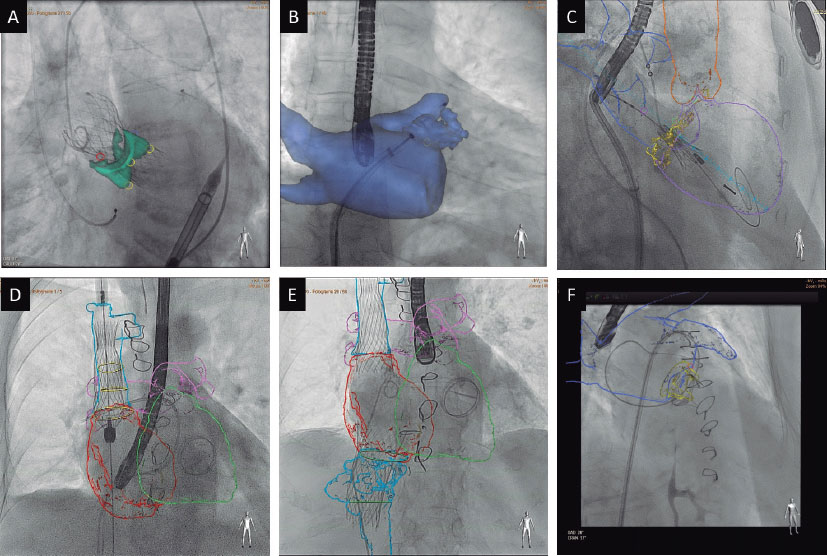

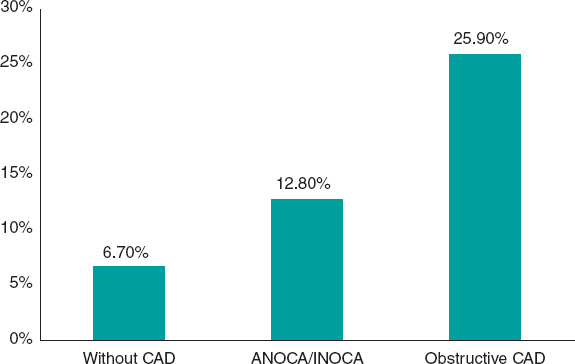

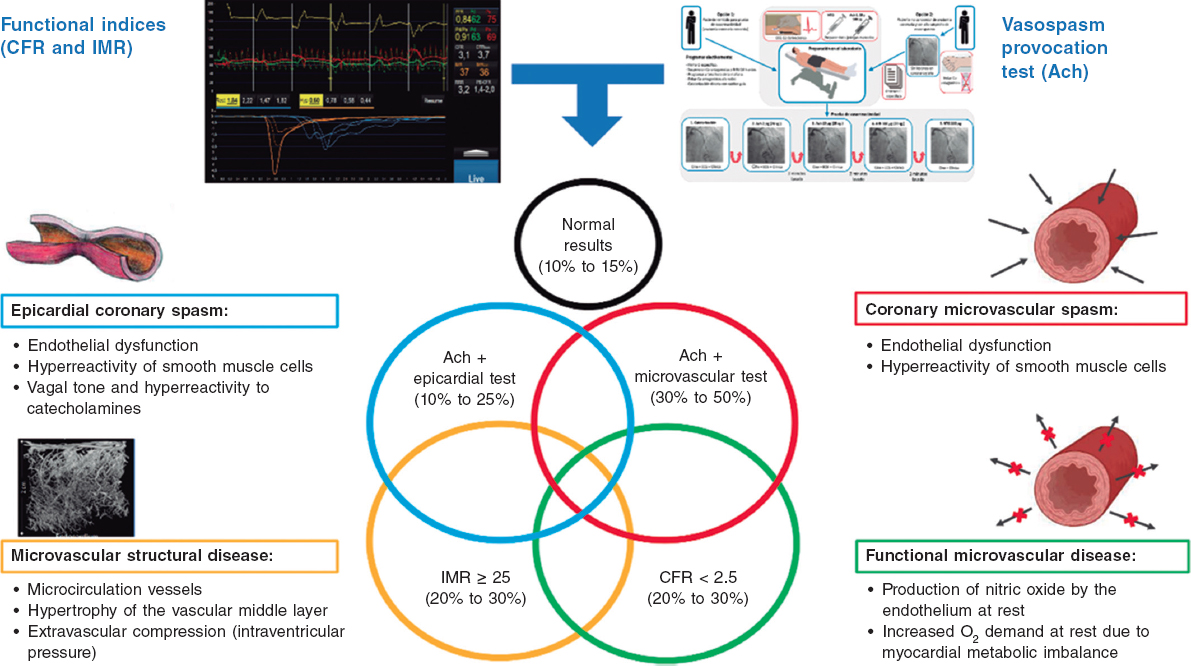

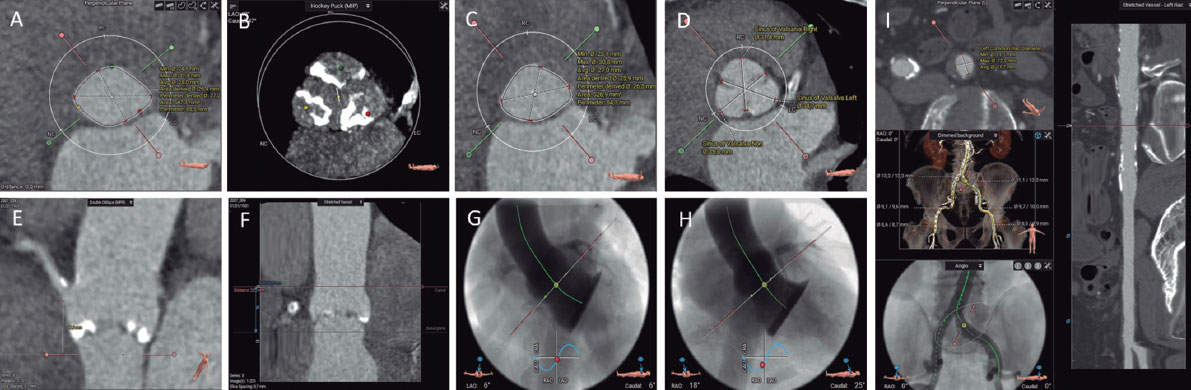

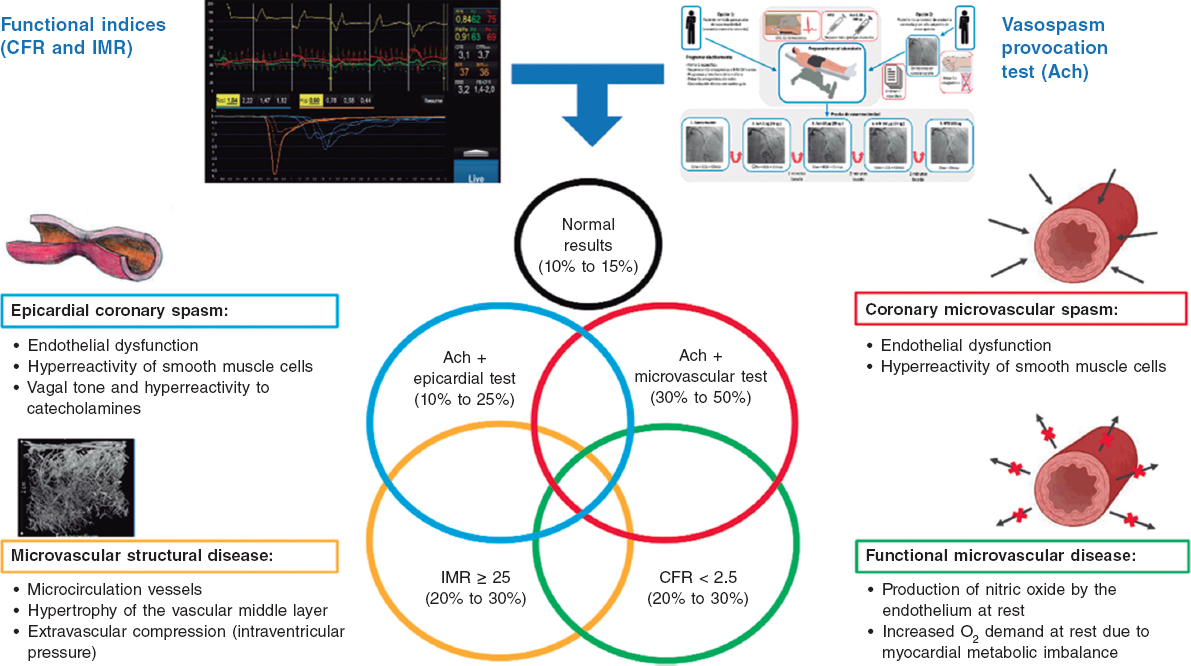

ABSTRACT

The approach to patients with acute mitral regurgitation poses a therapeutic challenge. These patients have a very high morbidity and mortality rate, thus requiring a multidisciplinary approach. This document presents the position of 3 associations involved in the management of these patients: the Ischemic Heart Disease and Acute Cardiovascular Care Association, the Interventional Cardiology Association, and the Cardiac Imaging Association. The document discusses aspects related to patient selection and care, technical features of the edge-to-edge procedure from both the interventional and imaging unit perspectives, and the outcomes of this process. The results of mitral repair and/or replacement surgery, which is the first-line treatment option to consider in these patients, have not been included as they exceed the scope of the aims of the document.

Keywords: Mitral regurgitation. Acute myocardial infarction. Left ventricular ejection fraction. Papillary muscle rupture. Transcatheter edge-to-edge mitral valve repair.

RESUMEN

El tratamiento de los pacientes con insuficiencia mitral aguda supone un reto terapéutico. Estos pacientes tienen una morbimortalidad muy elevada, que requiere un abordaje multidisciplinario. El presente documento recoge el posicionamiento de tres asociaciones implicadas en el tratamiento de estos pacientes: la Asociación de Cardiopatía Isquémica y Cuidados Agudos Cardiovasculares, la Asociación de Cardiología Intervencionista y la Asociación de Imagen Cardiaca. Incluye aspectos relacionados con la selección y los cuidados del paciente, los aspectos técnicos del tratamiento de borde a borde desde el punto de vista intervencionista y de la imagen cardiaca, y los resultados de este proceso. No se han incluido los resultados de la cirugía de reparación o sustitución mitral, que es la primera opción terapéutica a considerar en estos pacientes, por exceder los objetivos del documento.