Structural intervention

REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:112-118

A decade of left atrial appendage closure: from procedural data to long-term clinical benefit

Una década de cierre percutáneo de la orejuela izquierda: desde el procedimiento hasta el beneficio a largo plazo

aServicio Endovascular, Hospital Virgen Macarena, Seville, Spain

bDepartamento de Medicina Preventiva y Salud Pública, Facultad de Medicina, Seville, Spain

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Although early discharge protocols after transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) have demonstrated to be safe in various studies, they are usually applied in high-experience centers. This study analyzes the length of stay of the first 100 patients undergoing TAVI in a center without on-site cardiac surgery, differentiating between very early (< 24 hours), early (24-48 hours), and late discharge (> 48 hours). Furthermore, the study evaluates the feasibility of an early discharge protocol during the team’s learning curve.

Methods: We conducted a prospective observational study from April 2022 through January 2024. A preand postoperative management protocol was implemented, including assessments in the Valvular Heart Disease Clinic, admission to the cardiac surgery intensive care unit with electrocardiographic monitoring, and specific discharge criteria in full compliance with an established protocol for the management of conduction disorders. Early follow-up evaluations were performed in the outpatiently after discharge.

Results: A total of 100 patients (50% women) were included, with a mean age of 82.4 ± 5.3 years and a EuroSCORE II score of 4.38 ± 5.1%. The median length of stay was 2 days (range, 1-19). A total of 27.27% of patients were discharged in < 24 hours, 48.49% within the 24-48 hours following implantation, and 24.24% 48 hours later. The 30-day cardiovascular mortality rate was 1%. A total of 6 patients were readmitted with procedural complications within the first 30 days.

Conclusions: The implementation of a standardized care protocol allows for early and safe discharge in most patients, even during the team’s learning cuve.

Keywords: TAVI. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Length of stay. Early discharge. Learning curve.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Los protocolos de alta precoz tras el implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) han demostrado ser seguros en diversos estudios, aunque solo se aplican en centros con amplia experiencia. Este estudio analiza la duración de la estancia hospitalaria de los primeros 100 pacientes receptores de TAVI en un centro sin cirugía cardiaca in situ, diferenciando entre alta muy temprana (< 24 horas), temprana (24-48 horas) y tardía (> 48 horas), y evalúa la viabilidad de un protocolo de alta temprana durante la fase de aprendizaje del equipo.

Métodos: Estudio observacional prospectivo realizado entre abril de 2022 y enero de 2024. Se implementó un protocolo de cuidados prey posprocedimiento, que incluye valoración en la consulta de patología valvular, ingreso en la unidad de cuidados agudos cardiológicos con monitorización electrocardiográfica y criterios específicos para el alta según un protocolo establecido para el tratamiento de los trastornos de la conducción. Se realizó una evaluación precoz en la consulta tras el alta.

Resultados: Se incluyó a 100 pacientes (el 50% mujeres), con una edad media de 82,4 ± 5,3 años y EuroSCORE II de 4,38 ± 5,1%. La mediana de estancia hospitalaria fue de 2 días (rango: 1-19). Se dio de alta al 27,27% de los pacientes en < 24 horas, al 48,49% en las 24-48 horas posteriores al implante y al 24,24% después de 48 horas. La mortalidad de causa cardiovascular a 30 días fue del 1%. En los primeros 30 días, 6 pacientes reingresaron por motivos relacionados con el procedimiento.

Conclusiones: La aplicación de un protocolo de cuidados estandarizado permite un alta temprana y segura en la mayoría de los pacientes, incluso durante la fase de aprendizaje del equipo.

Palabras clave: TAVI. Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Estancia hospitalaria. Alta temprana. Curva de aprendizaje.

Abbreviations

CLBBB: complete left bundle branch block. CRBBB: complete right bundle branch block. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

In our setting, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become the treatment of choice for patients older than 75 years or with high surgical risk.1 Despite the good results documented in various studies, the stay after the procedure remains considerably long. According to data from the Spanish registry2, the mean length of stay is approximately 8 days. Given the increasing volume of patients, it is essential to implement protocols that optimize the length of stay and facilitate early discharge.

Experiences documented to this date on early discharge protocols after TAVI have demonstrated their safety profile.3-13 However, there is no uniform definition of the term “early discharge,” as it can range from 24 to 72 hours after the procedure.3-13

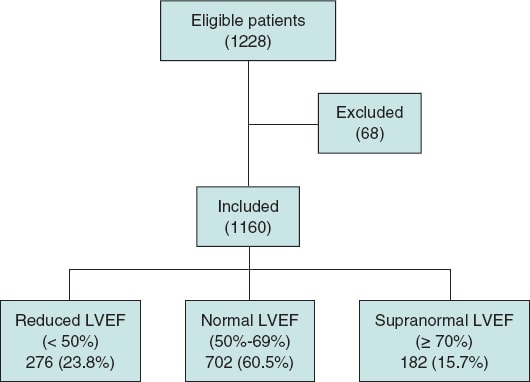

Most studies share common characteristics. On the one hand, they focus on procedures with a minimalist approach that favors faster patient recovery.14,15 On the other hand, many of them exclusively include patients with favorable pre-implant conditions,3-5,10,12 such as absence of frailty, adequate femoral access for transcatheter closure, absence of advanced conduction disorders, low-risk aortic annulus anatomy, body mass index < 35, left ventricular ejection fraction > 30%, and adequate family support. Consequently, these protocols only cover 22-55% of patients treated with TAVI.

A study conducted by a Spanish group has shown that early discharge, combined with artificial intelligence-based follow-up, is a safe strategy comparable to prolonged hospitalization in an unselected population after TAVI.13

Another important aspect is the type of valves used in the studies. Although the safety profile of early discharge after balloon-expandable valve implantation has been demonstrated,6,7 evidence on self-expanding valves is scarcer, due to doubts about the occurrence of conduction disturbances in the following days. However, in recent years, experiences have been published indicating that early discharge after the implantation of this type of valve is also safe.4,5,8,13,14

Finally, another relevant issue in these studies is that they have been conducted in highly experienced centers.3-13 Several analyses show that centers with a higher volume of procedures and more accumulated experience have lower complication rates and better overall results,16,17 which may translate into greater confidence in adopting early discharge practices.

It seems clear that reducing the length of stay through the implementation of early discharge protocols is a strategy that has demonstrated its feasibility in experienced centers. However, its application in those starting TAVI programs requires additional studies that ensure comparable results in terms of safety. Therefore, the objective of our study is to evaluate the length of stay of the first 100 patients treated with TAVI in our hospital (very early discharge: < 24 hours; early discharge: 24-48 hours; late discharge: > 48 hours) and determine the feasibility of establishing an early discharge protocol during the team’s learning curve.

METHODS

Patient selection and follow-up

We conducted a prospective, single-center registry that consecutively included all patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis who underwent TAVI in a center without on-site cardiac surgery, from the beginning of the program. The reference cardiac surgery department is located in a different center 2 km away.

The patients’ baseline characteristics, pre- and postoperative electrocardiographic and echocardiographic findings, the procedural characteristics, and the 30-day and 1-year clinical outcomes were recorded. The registry has been approved by Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria ethics committee. Relevant informed consents were obtained.

Pre- and postoperative care protocol

We developed a pre- and postoperative care protocol to standardize patient management (figure 1), in such a way that during the week prior to implantation, a cardiologist and a nurse specialized in TAVI jointly assess patients in the monographic valvular heart disease clinic. During this visit, additional tests are reviewed, the patient and their family are briefed on the procedure and possible complications, the informed consent form and a leaflet with relevant information are provided (drug management, how to proceed on implantation day, contact telephone number, etc.). Patients receive a call from nursing staff 48 hours prior to the intervention to remind them of the instructions.

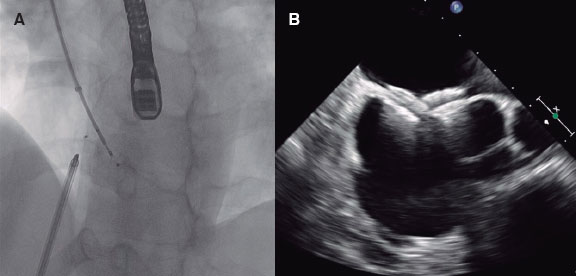

Figure 1. Pre- and postoperative care protocol for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. ECG, electrocardiogram.

On the morning of the procedure, patients go to the interventional cardiology unit of our center, where a venous line is established, an electrocardiogram is performed, and prophylactic antibiotics are administered. After implantation, they are admitted to the acute cardiac care unit with electrocardiographic monitoring. The next day, the absence of complications is ruled out, an electrocardiogram and a transthoracic echocardiogram are performed, and the discharge decision is made according to the protocol for the approach and treatment of conduction disorders by Rodés-Cabau J et al.18 adapted to our center (figure 2).

During follow-up, a telephone consultation is conducted 48 hours after discharge to rule out any complications, and a face-to-face consultation with electrocardiogram and transthoracic echocardiogram is performed 10 days later. If progress is adequate, follow-up continues in general cardiology clinics. The care protocol and the algorithm for the treatment of conduction disorders are showin in figure 1 and figure 2, respectively.

Figure 2. Protocol for the management of conduction disorders after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Very early discharge: < 24 hours; early discharge: 24-48 hours. AVB, atrioventricular block; ECG, electrocardiogram; EPS, electrophysiological study; LBBB: left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Procedural characteristics

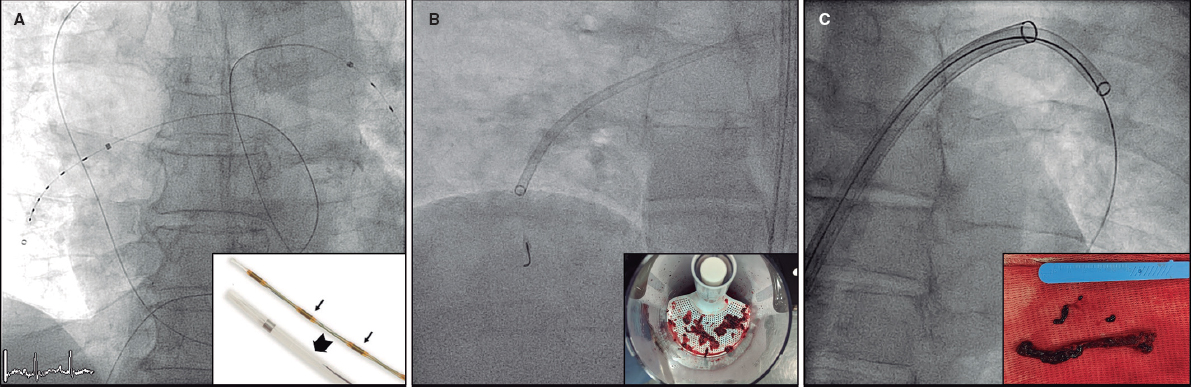

During the team’s learning curve, a “mixed” approach was selected. Procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Regarding vascular access, transcatheter transfemoral primary access and closure with double Prostyle (Abbott Vascular, United States) and AngioSeal (Terumo) were prioritized; the radial route was used as secondary access. Pacing was performed with a balloon-tipped electrocatheter via jugular venous access. Urinary catheterization was omitted. The self-expanding Evolut R/PRO+ (Medtronic, United States and Ireland) and ACURATE neo2 (Boston Scientific, United States) valve were implanted. Transthoracic echocardiography was used for postoperative monitoring.

Endpoints

The endpoint of this study is to analyze the length of stay of the first 100 patients undergoing TAVI in our center, differentiating between very early (< 24 hours), early (24-48 hours), and late discharge (> 48 hours) and evaluate the possibility of establishing an early discharge protocol during the team’s learning curve.

In addition, we aim to evaluate clinical outcomes according to the VARC-3 standardized definitions,19 including cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular mortality at 30 days and between 30 days and 1 year, procedural or cardiovascular-related rehospitalizations at 30 days, need for pacemaker implantation in the same period, and rate of neurological events, bleeding complications > BARC 3a, major vascular complications, and cardiac structural complications.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute frequency and percentage, and the continuous ones as mean and standard deviation.

RESULTS

The first 100 patients treated with TAVI in a tertiary referral center without an on-site cardiac surgery department were prospectively included from April 2022 through January 2024.

The patients’ baseline characteristics

The patients’ baseline characteristics are shown in table 1. Of note, 50% were men, with a mean age of 82.4 ± 5.3 years. The STS score was 4.3 ± 5.1% and the EuroSCORE II score, 4.38 ± 5.1%. The main indication for implantation was age older than 75 years in 96% and high surgical risk in patients younger than 75 years in 4%. Regarding baseline conduction disorders, 10% of patients had complete left bundle branch block, 11%, complete right bundle branch block, and 12% a previously implanted pacemaker.

Table 1. Patient characteristics and indication for transcatheter aortic valve implantation

| Variables | Values |

|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics | |

| Age, years | 82.4 ± 5.36 |

| Sex (male/female) | 50/50 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| Hypertension | 73 (73) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 43 (43) |

| Dyslipidemia | 61 (61) |

| Active smoking | 16 (16) |

| Past medical history | |

| Coronary artery disease | 37 (37) |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 13 (13) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 34 (34) |

| Heart failure | 31 (31) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 44 (44) |

| Previous permanent pacemaker | 12 (12) |

| Previous LBBB | 10 (10) |

| Previous RBBB | 11 (11) |

| Baseline echocardiogram | |

| LVEF, % | 58.8 ± 10.1 |

| Peak gradient, mmHg | 71.4 ± 15.8 |

| Mean gradient, mmHg | 44.8 ± 10.8 |

| Aortic valve area, cm2 | 0.75 ± 0.139 |

| Aortic regurgitation | 36 (36) |

| Bicuspid aortic valve | 3 (3) |

| Surgical risk | |

| EuroSCORE II | 4.32 ± 5.15 |

| STS score | 4.38 ± 3.34 |

| Indication for implantation | |

| Age > 75 years | 96 (96) |

| High surgical risk in patients < 75 years | 4 (4) |

|

LBBB, left bundle branch block; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; RBBB, right bundle branch block; STS, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Unless otherwise indicated, data are expressed as frequency and percentage (n, %) or mean ± standard deviation. |

|

Procedural characteristics and perioperative results

Procedural characteristics and perioperative results are summarized in table 2. Procedures were performed under general anesthesia, and all patients were extubated in the operating room. Access was transcatheter transfemoral in 95% of patients, with closure using double Prostyle (Abbott Vascular, United States) and AngioSeal (Terumo, Japan). A total of 5% of these patients required surgical access by the vascular surgery service (2%, femoral; 3%, axillary). Second access was radial in 98% of cases.

Table 2. Procedural characteristics and perioperative outcomes

| Procedural characteristics and outcomes | Values |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Proctored (yes/no) | 24/76 |

| Vascular access | |

| Transcatheter femoral | 95 (95) |

| Surgical femoral | 2 (2) |

| Surgical axillary | 3 (3) |

| Native valve | 98 (98) |

| Valve-in-valve | 2 (2) |

| Predilation | 88 (88) |

| Postdilation | 22 (22) |

| Type of valve | |

| Evolut R/PRO+, Medtronic | 87 (87) |

| ACURATE neo2, Boston Scientific | 13 (13) |

| Perioperative outcomes | |

| Intraoperative mortality | 0 (0) |

| Post-implantation gradient > 20 mmHg | 0 (0) |

| Aortic regurgitation > grade II | 2 (2) |

| Aortic annulus rupture | 0 (0) |

| Aortic dissection | 0 (0) |

| Coronary artery occlusion | 0 (0) |

| Device embolization | 0 (0) |

| Conversion to surgery | 0 (0) |

|

Data are expressed as frequency and percentage (n, %). |

|

A total of 24 proctored cases were performed. Valve implantation was successful in 100% of cases. A total of 98 procedures were performed on native aortic valves (95, trileaflet; 3, bicuspid) and 2 on degenerated surgical bioprostheses using the chimney stent technique. Self-expanding valves were implanted (87%, Evolut R/PRO+; 13%, ACURATE neo2).

The immediate outcome was monitored with transthoracic echocardiography. More than moderate residual aortic regurgitation occurred in only 2 patients. There were no annular ruptures, aortic complications, coronary artery occlusions, device embolizations, or need for conversion to surgery. No patients died during the procedure.

Mortality and complications after TAVI

Mortality and complications after TAVI are shown in table 3. The 30-day cardiovascular mortality rate was 1% (1 patient who died during hospitalization due to heart failure complicated by a respiratory sepsis). In the follow-up after discharge, 2 deaths due to non-cardiovascular causes were recorded: 1 patient died from aspiration pneumonia at 6 months and another due to complications derived from colon cancer 9 months after implantation.

Table 3. Complications and mortality after transcatheter aortic valve implantation

| Complications and Mortality | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Transient LBBB | 26 (33) |

| Persistent LBBB at discharge | 6 (7.6) |

| Pacemaker implantation at 30 days | 11 (12.5) |

| Stroke | 1 (1) |

| Bleeding complications > BARC 3a | 1 (1) |

| Major vascular complications | 4 (4) |

| Cardiovascular rehospitalization at 30 days | 6 (6) |

| Cardiovascular mortality at 30 days | 1 (1) |

| Non-cardiovascular mortality at 30 days | 0 (0) |

| Cardiovascular mortality from 30 days to 1 year | 0 (0) |

| Non-cardiovascular mortality from 30 days to 1 year | 2 (2) |

|

BARC: Bleeding Academy Research Consortium scale; LBBB: left bundle branch block. a Data are expressed in numbers and percentages (n, %). |

|

Within the first 30 days, 6 patients required admission for procedural or cardiovascular-related causes. The reason for admission was infection in 3 patients: a wound infection in a patient who underwent surgical femoral access, an early infective endocarditis that had a good outcome with optimal medical therapy, and a pacemaker pocket infection that required device explantation and contralateral implantation. One patient was admitted with heart failure for developing rapid atrial fibrillation. Two patients were admitted for syncope; one had a PR interval of 350 ms and the other complete atrioventricular block. Both underwent permanent pacemaker implantation.

The rate of major vascular complications was 4%: 3 patients presented stenosis or dissection of the common femoral artery requiring stent implantation during the same procedure; furthermore, a femoral pseudoaneurysm was detected in 1 patient and was surgically repaired. One case of BARC > 3a bleeding complication was detected; the patient required transfusion of 2 packed red blood cell concentrates due to lower GI bleeding.

One patient had a stroke at 24 hours. The need for permanent pacemaker implantation was 12.5% within the first 30 days. The delay for permanent pacemaker implantation once the indication was established was < 48 hours.

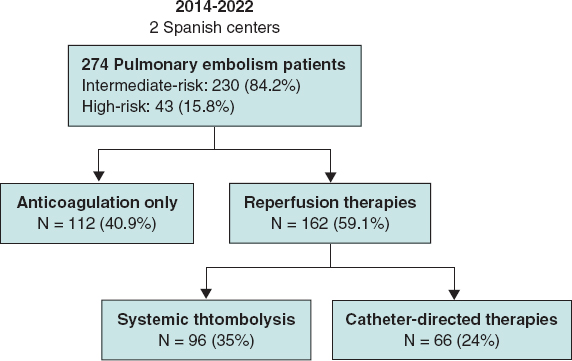

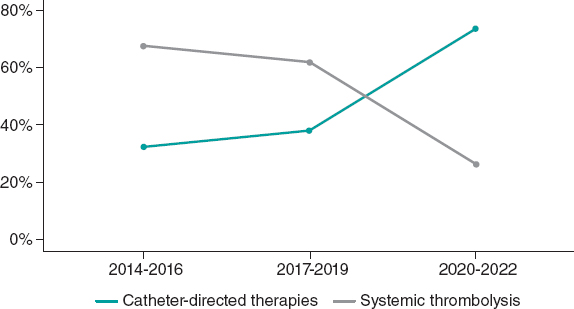

Length of stay

The pre-specified care protocol was implemented in all patients (figure 1 and figure 2). As a result, the median length of stay was 2 days (range, 1-19) for all patients (table 4). Regarding time to discharge (figure 3), 27 patients (27.27%) were discharged within the first 24 hours (very early discharge), 48 (48.49%) between 24 and 48 hours after implantation (early discharge), while 24 patients (24.24%) had to be hospitalized for more than 48 hours (late discharge). Late discharges corresponded to 8 patients whose TAVI was performed during admission for heart failure or cardiogenic shock, 10 patients who had pre-existing conduction disorders (mainly first-degree atrioventricular block or complete right bundle branch block) or who developed them after implantation and required prolonged electrocardiographic monitoring, 2 patients who underwent surgical femoral access, 2 patients with major vascular complications, 1 patient who had a stroke at 24 hours, and 1 patient who developed bacteremia due to Streptococcus mitis.

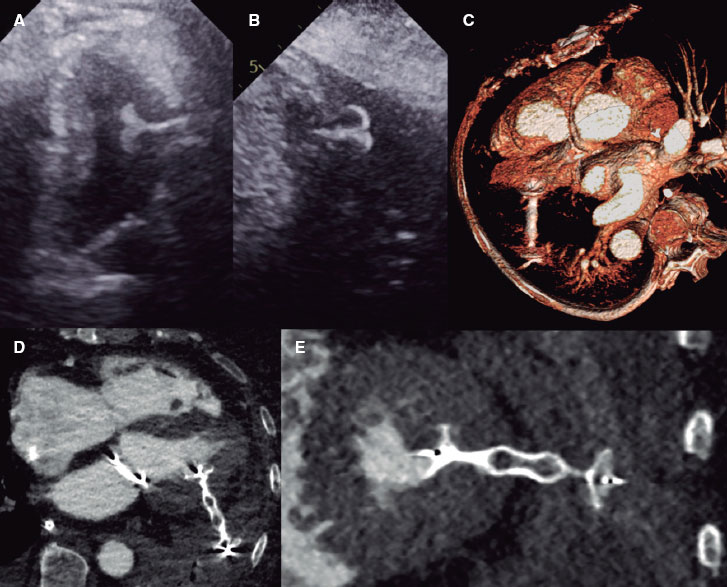

Figure 3. Length of stay of the first 100 TAVI patients. TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

Table 4. Length of stay

| Length of stay | Time |

|---|---|

| Length of stay, days | 2 (1-19) |

| Very early discharge < 24 hours | 27 (27.27) |

| Early discharge 24-48 hours | 48 (48.49) |

| Late discharge > 48 hours | 24 (24.24) |

|

ME: median; n: number. Data are expressed in days and median (interquartile range) or in number and percentage (n, %). |

|

DISCUSSION

The main findings of our study are a) it is feasible to establish a protocol that favors the early discharge of patients during the medical team’s learning curve; b) approximately 75% of patients achieve early discharge (< 48 hours); and c) it is a safe strategy associated with a low rate of adverse events at 30 days.

The progressive increase in the number of patients we will be facing in the coming years makes it essential to establish protocols that optimize the length of stay and allow for efficient use of resources.

Several experiences can be found in the literature confirming that early discharge protocols after TAVI are safe. The main problems they present are the lack of a standardized definition of early discharge, which can vary from 24 to 72 hours,3-13 and that most studies on early discharge agree on including patients with favorable anatomical characteristics,3-5,10,12 such as adequate femoral access for transcatheter closure, absence of advanced conduction disorders, low-risk aortic annulus anatomy, body mass index < 35, and left ventricular ejection fraction > 30%; in addition, they exclude patients with factors that could prolong the length of stay, such as frailty or lack of family support. Following these criteria, only 59% of our patients would have been eligible for an early discharge program, yet we were able to discharge 75% of the patients within the first 48 hours. In our series, the median length of stay for outpatients with the favorable characteristics described above is 2 days (1-10), and that of outpatients who did not meet favorable criteria is 2 days (1-18), while the length of stay of the 8 patients undergoing TAVI during hospitalization for decompensated heart failure or cardiogenic shock is 10.5 days (1-30). In this regard, the experience of Herrero et al.13 is noteworthy, who demonstrated in their study that most patients (73%) in an unselected population can be safely discharged within the first 24-48 hours.

The minimalist approach14,15 is another key aspect that has been shown to favor early discharge. This approach is especially suitable when conducted by experienced teams and applied to collaborative, hemodynamically stable patients without anatomical characteristics involving a higher risk of complications. Its implementation should be progressive, so that the safety profile of the procedure is guaranteed as the fundamental priority. We opted to start the TAVI program with a “mixed” approach with general anesthesia, mainly femoral or radial access, pacing with a transvenous pacemaker, and monitoring with transthoracic echocardiography until the team overcame the learning curve. All patients were successfully extubated in the operating room. Therefore, we believe that this type of approach did not cause any delays in patient discharge. Once the first 100 cases have been completed, we are transitioning towards a fully minimalist procedure due to the benefits this entails for the patient.

The safety profile of early discharge after the implantation of self-expanding valves has been widely discussed4,5,8,13,14, due to the increased risk of developing cardiac conduction disorders. In our study, all patients received a self-expanding valve. The algorithm by Rodés-Cabau et al.18 was applied to determine the duration of electrocardiographic monitoring and manage conduction disorders. The need for permanent pacemaker implantation was confirmed in 12.5% of cases within the first 30 days. Only 2 patients required readmission after discharge due to advanced conduction disorders requiring pacemaker implantation.

In addition, it is important to have a close follow-up system that allows for the early detection of post-discharge complications and ensures continuity of care. To this end, our patients receive a telephone consultation 48 hours after discharge, and a face-to-face consultation with electrocardiograms and echocardiograms being performed at 10 days. They also have a telephone number to contact the team during working hours. Undoubtedly, this is a system that takes human and economic resources. Experiences have been reported in which the implementation of a virtual voice assistant facilitates the detection of complications, thus demonstrating the effectiveness of this system,13 which should be considered the standard we should look for in clinical practice.

Reducing the length of stay after TAVI requires a real commitment from the heart team to the implementation and adherence to an early discharge protocol. The BENCHMARK study20 showed that adherence to an 8-point structured protocol allows for shorter lengths of stay of approximately 2 days. The key aspects identified in this protocol include educating the health care team, a clear definition of discharge criteria, a structured decision algorithm to assess the need for pacemaker implantation, echocardiographic or angiographic follow-up of the puncture site, early patient mobilization, patient and family education, and anticipated discharge planning from admission. In our own experience, the role of a cardiologist coordinating the TAVI program, along with close collaboration with key units and services, such as acute cardiac care, imaging, electrophysiology, anesthesiology, vascular surgery, and radiology, has enabled the effective implementation of these strategies. This approach has facilitated the consolidation of an early discharge protocol from the start of the program.

Limitations

Our study has multiple limitations that may affect result extrapolation. On the one hand, this was a study of observational design conducted in a single center and with a small sample size; additionally, a total of 24 cases were performed under supervision. On the other hand, only self-expanding valves were used, meaning that results cannot be generalized to other types of valves.

CONCLUSIONS

During the team’s learning curve, the application of a standardized care protocol allows for early and safe discharge after TAVI in most patients in an unselected population.

FUNDING

None declared.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Approval was obtained from Hospital Universitario Nuestra Señora de Candelaria ethics committee. Informed consents are available. The SAGER guidelines regarding potential sex and gender biases have been followed.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence has not been used for the development of the study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

R. Pimienta González and A. Quijada Fumero participated developing the protocol, collecting data, and drafting the manuscript. All authors participated in the study design, critically reviewed the text, and approved its final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The constant increase in the number of TAVIs being performed has created the need to establish protocols that reduce the length of stay.

- Several studies have shown that early discharge protocols are safe, as long as they are implemented in experienced centers.

- However, it is still unknown whether it is feasible to apply an early discharge protocol from the beginning of a TAVI program.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The implementation of a care protocol adapted to the specific characteristics of each center allows for early and safe discharge of most patients after TAVI, even during the team’s learning curve.

REFERENCES

1. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al.;ESC Scientific Document Group. 2021 ESC/EACTS guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:561-632.

2. Jimenez-Quevedo P, Munoz-Garcia A, Trillo-Nouche R, et al. Time trend in transcatheter aortic valve implantation:an analysis of the Spanish TAVI registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2020;2:98-105.

3. Wood DA, Lauck SB, Cairns JA, et al. The Vancouver 3M (Multidisciplinary, Multimodality, But Minimalist) Clinical Pathway facilitates safe next-day discharge home at low-, medium-, and high-volume transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement centers:the 3M TAVR study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:459-469.

4. Asmarats L, Millán X, Cubero-Gallego H, et al. Implementing a fast-track TAVI pathway in times of COVID-19:necessity or opportunity?REC Interv Cardiol. 2022;4:150-152.

5. García Carreño J, Zatarain E, Tamargo M, et al. Feasibility and safety of early discharge after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2023;76:655-663.

6. Barbanti M, Van Mourik M, Spence M, et al. Optimising patient discharge management after transfemoral aortic valve implantation:the multicentre European FAST-TAVI trial. EuroIntervention. 2019;15:147-154.

7. Kamioka N, Wells J, Keegan P, et al. Predictors and clinical outcomes of next-day discharge after minimalist transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:107-115.

8. Moriyama N, Vento A, Laine M, et al. Safety of next-day discharge after transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a self-expandable versus balloon-expandable valve prosthesis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:1-9.

9. Baekke PS, Jørgensen TH, Søndergaard L. Impact of early hospital discharge on clinical outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:E282-E290.

10. Krishnaswamy A, Isogai T, Agrawal A, et al. Feasibility and safety of same-day discharge following transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:575-589.

11. Hanna G, Macdonald D, Bittira B, et al. The safety of early discharge following transcatheter aortic valve implantation among patients in Northern Ontario and rural areas utilizing the Vancouver 3M TAVR study clinical pathway. CJC Open. 2022;4:1053-1059.

12. Barker M, Sathananthan J, Perdoncin E, et al. Same-day discharge post-transcatheter aortic valve replacement during the COVID-19 pandemic:the multicenter PROTECT TAVR study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:590-598.

13. Herrero Brocal M, Samper R, Riquelme J, et al. Early discharge programme after transcatheter aortic valve implantation based on close follow-up supported by telemonitoring using artificial intelligence:the TeleTAVI study. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2024;6:73-81.

14. Lauck SB, Wood DA, Baumbusch J, et al. Vancouver transcatheter aortic valve replacement clinical pathway:minimalist approach, standardized care, and discharge criteria to reduce length of stay. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:312-321.

15. Pinar Bermúdez E. Debate:Minimalist approach to TAVI as a default strategy. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:304-306.

16. Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, Mack MJ, et al. Procedural volume and outcomes for transcatheter aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2541-2550.

17. Núñez-Gil IJ, Elola J, García-Márquez M, et al. Percutaneous and surgical aortic valve replacement. Impact of volume and type of center on results. REC Interv Cardiol. 2021;3:103-111.

18. Rodes-Cabau J, Ellenbogen KA, Krahn AD, et al. Management of conduction disturbances associated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement:JACC Scientific Expert Panel. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:1086-1106.

19. Généreux P, Piazza N, Alu MC, et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3:Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:2717-2746.

20. Frank D, Durand E, Lauck S, et al. A streamlined pathway for transcatheter aortic valve implantation:the BENCHMARK study. Eur Heart J. 2024;45:1904-1916.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address: raquelpimientagonzalez@gmail.com (R. Pimienta González).

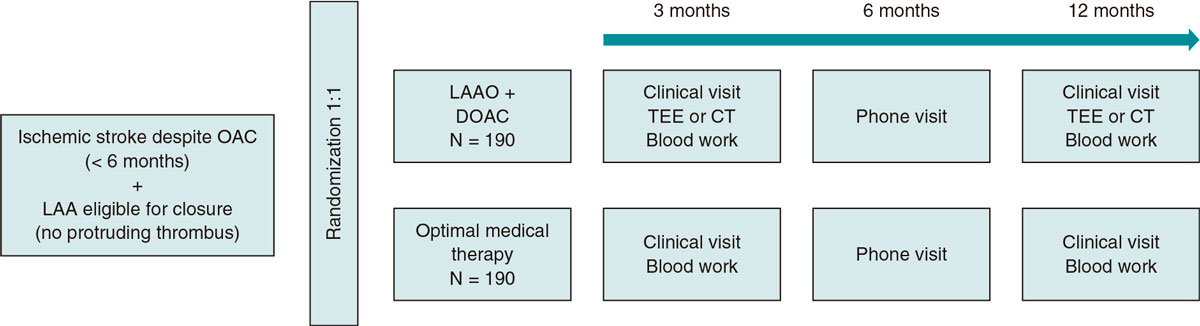

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Ultrasound renal denervation (uRDN) has emerged as an innovative therapeutic approach for the treatment of hypertension. However, its efficacy compared to medication remains uncertain. We aimed to assess the efficacy profile of uRDN vs sham groups focusing on its impact on daytime ambulatory blood pressure, 24-hour blood pressure, home blood pressure and office blood pressure.

Methods: We conducted a systematic search across Embase, PubMed, and Cochrane Library databases from their inception up 1 November 2024 to identify randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of uRDN. Statistical analyses were performed using RevMan 6.3 software, utilizing the mean and standard deviation method to calculate mean differences with a 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

Results: A total of 4 studies were included in the final analysis with 642 patients. uRDN significantly reduced daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure (SBP) (−5.12 mmHg; 95%CI, −6.07 to −4.16; P ≤ .00001), 24-h SBP (−4.87 mmHg; 95%CI, −6.53 to −3.21]; P ≤ .00001), office SBP (−5.03 mmHg; 95%CI, −6.27 to −3.79; P ≤ .00001) and showed a decrease in patient medication 6 months after the procedure.

Conclusions: Using uRDN leads to a lower blood pressure in patients within 2 months following the procedure. Additionally, after 6 months a significant decrease in drug use is observed.

This meta-analysis protocol was registered on PROSPERO on 7 July 2024 (CRD42024562852).

Keywords: Resistant hypertension. Ultrasound renal denervation. Systolic blood pressure. Diastolic blood pressure. Antihypertensive treatments.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La denervación renal por ultrasonido (DRU) ha surgido como un enfoque terapéutico innovador para la hipertensión arterial resistente. Sin embargo, su eficacia en comparación con la medicación sigue siendo incierta. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar la eficacia de la DRU frente a grupos simulados, con especial atención a su impacto sobre la presión arterial ambulatoria diurna, la presión arterial de 24 h, la presión arterial domiciliaria y la presión arterial en el consultorio.

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en las bases de datos Embase, PubMed y Cochrane Library hasta el 1 de noviembre de 2024, para identificar ensayos controlados aleatorizados que evaluaran la efectividad de la DRU. Los análisis estadísticos se realizaron con el programa informático RevMan 6.3, utilizando la media y la desviación estándar para calcular las diferencias de medias con un intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC95%).

Resultados: En el análisis final se incluyeron cuatro estudios con 642 pacientes. La DRU redujo de manera significativa la presión arterial sistólica (PAS) ambulatoria diurna (−5,12 mmHg; IC95%, −6,07 a −4,16; p ≤ 0,00001), la PAS de 24 h (−4,87 mmHg; IC95%, −6,53 a −3,21; p ≤ 0,00001) y la PAS en la consulta (−5,03 mmHg; IC95%, −6,27 a −3,79; p ≤ 0,00001), y logró una disminución de la medicación de los pacientes a los 6 meses del procedimiento.

Conclusiones: El uso de DRU conlleva una reducción de la presión arterial a los 2 meses del procedimiento. Adicionalmente, transcurridos 6 meses se observó una disminución significativa del uso de medicación.

El protocolo de este metanálisis fue registrado en PROSPERO el 7 de julio de 2024 (CRD42024562852).

Palabras clave: Hipertensión resistente. Denervación renal por ultrasonido. Presión arterial sistólica. Presión arterial diastólica. Tratamiento antihipertensivo.

Abbreviations

BP: blood pressure. DBP: diastolic blood pressure. SBP: systolic blood pressure. RCT: randomized controlled trial. uRDN: ultrasound renal denervation.

INTRODUCTION

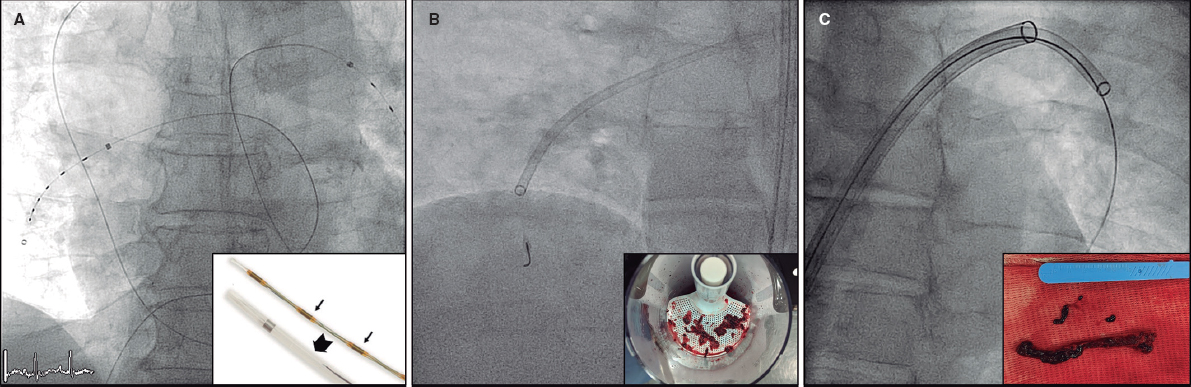

Hypertension is highly prevalent worldwide and well recognized as a major risk factor for cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and renal complications.1 Despite the availability of numerous antihypertensive drugs that effectively mitigate hypertension-related organ damage,1,2 a substantial proportion of patients fail to attain adequate blood pressure (BP) control,3 which may be attributed to factors such as medication non-adherence or the presence of resistant hypertension,4,5 which is defined as the presence of uncontrolled BP of, at least, 130/80 mmHg despite the simultaneous prescription of, at least, 3 or 4 antihypertensive drugs of different classes, or controlled BP despite the prescription of, at least, 4 drugs, at the maximum tolerated doses, including a diuretic.6 The pathophysiology of hypertension is intricate and includes a diverse array of mechanisms, with sympathetic overdrive emerging as a pertinent factor in all forms of hypertension.7 Consequently, novel therapeutic approaches have emerged, including renal denervation (RDN), which aims to decrease renal sympathetic activity thereby reducing BP. RDN has drawn considerable attention as a guideline-recommended BP lowering treatment along with lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy for patients with resistant hypertension.8,9 Recently, there has been growing consensus that RDN should also be considered for individuals whose hypertension is due to no therapeutic adherence.10-12 Early randomized controlled clinical trials yielded inconsistent findings on the efficacy profile of the intervention, with a substantial proportion of patients failing to respond across the trials.13,14 Potential explanations for the heterogeneous results include insufficient operator experience using the Symplicity Flex catheter (Medtronic, United States), the study participants’ baseline characteristics, and changes of antihypertensive medication.15 Subsequently, sham-controlled trials with better study designs, catheter technologies and procedural techniques have improved the BP-lowering safety and efficacy profile of RDN.16-18 Currently, various catheter systems are used for RDN, utilizing different technologies, such as radiofrequency-based systems like Symplicity Spyral (Medtronic, United States). Ultrasound-based catheters have also been developed, such as the Paradise (Recor Medical, United States), whose efficacy has been evaluated in multiple studies. Finally, there is a system based on alcohol-mediated RDN.19 Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Medtronic Symplicity Spyral and Recor Paradise system as adjuvant therapies for the treatment of hypertension.20

The efficacy of the latter was evaluated in a multicenter, randomized, blinded and sham-controlled trial. Subsequently, it was determined in the REQUIRE RADIANCE-HTN SOLO,16 RADIANCE HTN TRIO17 and RADIANCE II,18 and REQUIRE21 trials. Results were heterogeneous between the RADIANCE and REQUIRE trials, which had limitations that may account for the varied results.10 Finally, uRDN was concluded to be safe for the treatment of hypertension, even in patients with resistant hypertension and poor medical adherence.19 The aim of this study is to conduct a systematic review and a meta-analysis to examine the antihypertensive efficacy of uRDN in patients with hypertension vs a sham group treatment.

METHODS

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis which strictly followed the clinical practice guidelines established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.22 Methodological procedures were conducted in full compliance with the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis of Interventions. This meta-analysis protocol was registered on PROSPERO 7 July 2024, under protocol ID: CRD42024562852.

Criteria of the included studies

Inclusion criteria were established to identify relevant studies: patients with resistant hypertension and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing uRDN with sham groups, which did not undergo uRDN; RCTs reporting office, daytime ambulatory, home and 24-h ambulatory BP changes from baseline were included. We excluded those underreporting, at least, 1 of the following outcomes of interest: changes in BP between baseline and, at least, a 2-month follow up. In addition, we excluded non-English publications, case-control studies, case reports, single arm studies, letters to the editors, basic science research, meta-analyses, and review articles.

Literature search strategy

We conducted a comprehensive search across PubMed, EMBASE, and COCHRANE, from their inception until 1 November 2024. Keywords and free-text terms were used to explore literature on hypertension, renal denervation, and ultrasound ablation. Detailed search information for each database is provided in the Search strategy section of the supplementary data.

Screening of literature search strategy

Initially, a comprehensive database search was conducted to compile all relevant records. Duplicate entries were, then, manually removed using Zotero software. Afterwards, references were screened by title and abstract. When necessary, a full-text review was performed to ensure relevance and accuracy. Two authors (C. J. Palomino-Ojeda and L. H. García-Mena) independently assessed each the inclusion and quality of each article. Discrepancies were resolved by a third author (J. M. Guerrero-Hernández). Additionally, references cited in the included studies were scrutinized and included if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted using Excel spreadsheets to record the following information: a) baseline characteristics of the study population, b) summaries detailing the characteristics of the included studies, c) outcome measures, and d) domains evaluated for quality assessment.

Assessing the risk of bias

Randomized controlled trials were assessed using Version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2)22,23 from the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Our analysis included a funnel plot for the primary endpoint daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure (SBP) shown in figure 1 of the supplementary data.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram. RDN, renal denervation.

Outcome measures

BP changes were assessed by comparing baseline values and follow-up measurements taken, at least, 2 months later. The mean difference was analyzed using the mean and standard deviation.

Data analysis

The efficacy profile of uRDN vs the sham control was analyzed using continuous data to calculate the mean difference with its corresponding 95% confidence interval (95%CI).24 This analysis assessed BP changes across groups with an, at least, 2-month follow-up while evaluating their mean difference.

Furthermore, an examination was conducted to discern any variation among office BP, ambulatory daytime BP, 24-h ambulatory BP, nighttime ambulatory BP, and home BP outcomes in trials that reported these results. This was achieved by computing the mean and its associated standard deviation for the difference between the 2 outcomes. The validated Campbell calculator was used to convert the measures of dispersion from the outcomes in the REQUIRE trial for data analysis.24 The level of heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted using a random effects model to account for variability among studies.25 Subgroup analyses were predefined for first and second-generation RDN trials, with tests for interaction for the primary endpoint.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity among the included studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q statistic. Additionally, the I2 statistic was used to quantify the proportion of total variation attributed to heterogeneity, with values > 50% indicating high heterogeneity. All statistical analyses (including the calculation of standardized mean difference, relative risk, and mean difference) were performed using RevMan 6.3. software.22

RESULTS

Study selection

A total of 448 studies were identified across database searches. A total of 392 studies were screened after removing duplicate studies, 388 of which were excluded due to single-arm study (n = 6); publication in a language different than English (n = 1); case-control or case report studies and literature review (n = 140); basic scientific research (n = 24); editorial letter (n = 8); different type of RDN studies (n = 83); studies with ≤ 10 participants (n = 6); and does not compare intervention of interest (n = 120). Finally, 4 studies meet all inclusion criteria and were eligible for analysis. An analysis of 642 patients from the 4 selected articles was conducted as they met the inclusion criteria. The PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process is shown in figure 1.

Study characteristics

The studies included in our analysis included a total of 4 RCTs published from 2018 through 2023.16-18,21 All studies used uRDN and a sham control group. Two studies were performed in the United States/Europe,16,17 1 study only in the United States18 and the rest in Japan and South Korea.21 The baseline characteristics of the included studies were analyzed and summarized in table 1. Characteristics of the entire patient population are shown in table 2.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and following intervention of the included studies population

| Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RADIANCE HTN SOLO 201816 | RADIANCE-HTN TRIO 202117 | REQUIRE 202221 | RADIANCE II 202318 | |||||

| Group | uRDN | SHAM control | uRDN | SHAM control | uRDN | SHAM control | uRDN | SHAM control |

| N | 74 | 72 | 69 | 67 | 69 | 67 | 150 | 74 |

| Gender, female | 28 | 33 | 13 | 14 | 21 | 14 | 47 | 17 |

| Gender, male | 46 | 39 | 56 | 53 | 48 | 53 | 103 | 57 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 54.4 (10·2) | 53.8 (10·0) | 52.3 (7.5) | 52,8 (9.1) | 50.7 (11.4) | 55.6 (12.1) | 55.1 (9.9) | 54.9 (7.9) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 29.9 (5.9) | 29.9 (5.0) | 32.8 (5.7) | 32.6 (5.4) | 29.5 (5.5) | 28.4 (4.5) | 30.1 (5.2) | 30.6 (5.2) |

| Abdominal obesity | 41 | 44 | 54 | 55 | – | – | 90 | 46 |

| GFR mL/min/1.73 m2 | 84.7 (16.2) | 83.2 (16.1) | 86 (25.2) | 82.2 (19.2) | 74.2 (16.2) | 69.6 (17.1) | 81.4 (14.4) | 82.3 (14.9) |

| GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 15 | 18 | 7 | 3 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 2 | 5 | 21 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 9 | 5 |

| Cardiovascular disease | – | – | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 1 | – |

| Systolic BP at office screening, mm Hg | 142.6 (14.7) | 144.6 (15.9) | 161.9 (15.5) | 163.6 (16.8) | 157.6 (19.5) | 160.4 (14.9) | 155.8 (11.1) | 154.3 (10.6) |

| Diastolic BP at office screening, mm Hg | 92.3 (10.1) | Mean 93.6 (8.3) | 105.1 (11.6) | 103.3 (12.7) | 97.7 (16.6) | 95.3 (14.2) | 101.3 (6.7) | 99.1 (5.6) |

| HR at office screening, beats/min | 72 (12.1) | 72.6 (12.3) | 74.5 (11) | 77.6 (12.9) | 75.3 (10.8) | 71.5 (12.8) | 74.1 (12.0) | 73.6 (11.9) |

| Number of antihypertensive drugs at screening | 1: 33 2: 28 3: 1 | 1: 28 2: 27 3: 1 | 3: 27 4: 22 5: 20 | 3: 28 4: 24 5: 15 | 3: 32 4: 20 5: 17 | 3: 29 4: 23 5: 15 | 1: 52 2: 44 > 2: 0 | 1: 25 2: 25 > 2: 1 |

| Procedural time | 72.3 (23.3) | 38.2 (12.6) | 83.66 (22.71) | 41.33 (12.87) | 86.7 (54.0) | 40.2 (11.6) | 76.7 (25.2) | 43.9 (16.6) |

| Office systolic blood pressure at 2 months | 143.7 (16.7) | 149.7 (17.4) | 147.1 (20.3) | 152.1 (22) | – | – | 145.8 (15.9) | 151.2 (16.4) |

| Office diastolic blood pressure at 2 months | 94.2 (10.1) | 98 (10) | 96.6 (13.9) | 98.7 (13.8) | – | – | 96.0 (10.2) | 98.1 (11.2) |

| Daytime ambulatory systolic BP at 2 months | 141.9 (11.9) | 147.9 (13.3) | 141.0 (16.1) | 146.3 (18.8) | – | – | 135.6 (13) | 142.9 (10.5) |

| Daytime ambulatory diastolic BP at 2 months | 87.9 (7.1) | 90.9 (7.9) | 88.5 (11.6) | 90.7 (12.2) | – | – | 83.1 (7.6) | 87.0 (6.3) |

| 24-hour systolic BP at 2 months | 135.6 (11.4) | 140.7 (11.8) | 135.2 (16.0) | 140.5 (18.7) | – | – | 135.6 (13.0) | 142.9 (10.5) |

| 24-hour diastolic BP at 2 months | 83 (6.8) | 85.7 (7.1) | 83.6 (10.9) | 85.8 (12) | – | – | 83.1 (7.6) | 87.0 (6.3) |

| Home systolic BP at 2 months | 139.4 (11.7) | 146.6 (15.4) | 144.6 (18.2) | 149.9 (18.9) | – | – | 143.4 (12.3) | 148.8 (12.3) |

| Home diastolic BP at 2 months | 89.9 (7.8) | 93.3 (8.5) | 93.2 (14.7) | 96 (12.8) | – | – | 92.7 (7.4) | 95.5 (8.1) |

| Nighttime ambulatory systolic BP at 2 months | 125.6 (12.8) | 129.4 (13.1) | 126.3 (18.4) | 76.2 (12.2) | – | – | 125.5 (15.0) | 132.4 (12.2) |

| Nighttime ambulatory diastolic BP at 2 months | 74.8 (8.5) | 77.3 (8.5) | 131.9 (20.9) | 78.4 (13.2) | – | – | 75.1 (9.7) | 79.6 (7.5) |

|

BP, blood pressure; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation; uRDN, ultrasound renal denervation. |

||||||||

Table 2. Summary of included studies

| Study ID | Country | Study design | Total population | Compare interventions | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States/Europe | RCT | 146 | uRDN vs SHAM control | Renal denervation resulted in a greater reduction in daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure compared with a sham procedure | |

| United States/Europe | RCT | 136 | uRDN vs SHAM control | Renal denervation reduced daytime ambulatory systolic blood pressure more than the sham procedure | |

| Japan and South Korea | RCT | 136 | uRDN vs SHAM control | Is the first trial of ultrasound renal denervation in Asian patients with hypertension on antihypertensive therapy | |

| The study did not show a significant difference in ambulatory blood pressure reductions in treated patients with resistant hypertension | |||||

| United States | RCT | 224 | uRDN vs SHAM control | The primary efficacy outcome was the mean change in daytime ambulatory SBP at 2 months | |

| No major adverse events were reported in either group | |||||

|

RCT: randomized controlled trial; SBP, systolic blood pressure; uRDN: ultrasound renal denervation. |

|||||

In the analysis of 642 patients, the mean age was 54.15 years ± 9.95, 70.8% were men, and the mean body mass index was estimated at 30 kg/m2 ± 5.3. Regarding comorbidities, 15.1% had type 2 diabetes mellitus, and 5.6%, cardiovascular disease. The mean glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated at 82.25 mL/min/1.73 m2 ± 16.2. In addition, 9.6% of patients had GFR levels < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Of note, eligibility criteria in all trials include an estimated GFR > 40 mL/min/1.73 m2. Two studies— the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO and the RADIANCE II—included patients on 1 to 3 antihypertensive drugs and were designed as “Off Med” studies, meaning patients underwent a washout period with no antihypertensive treatment for 4 weeks in the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO and 8 weeks in the RADIANCE II. Additionally, patients who experienced complications such as high BP were given antihypertensive escape therapy.26 On the other hand, the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO and REQUIRE trials included patients on 3 to 5 antihypertensive drugs and evaluated the uRDN in patients on concomitant antihypertensive therapy. However, only the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO trial standardized antihypertensive treatment over a 4-week regimen with a fixed-dose of 3 drugs in a single pill including amlodipine 10 mg; valsartan 160 mg (or olmesartan 40 mg); and hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg. Additionally, treatment adherence was assessed by mass spectrometry.21,27,28 Enrollment criteria were comparable across the analyzed studies. Similarly, exclusion criteria were consistent in all studies; however, the RADIANCE trials additionally excluded patients with anatomical variations or alterations in renal artery anatomy, as detected on renal computed tomography or magnetic resonance angiography.27 In all studies, patients were blinded prior to the uRDN procedure. Furthermore, in all RADIANCE trials, blinding was implemented after the washout period or after the patients completed the fixed-dose treatment.18,26,27

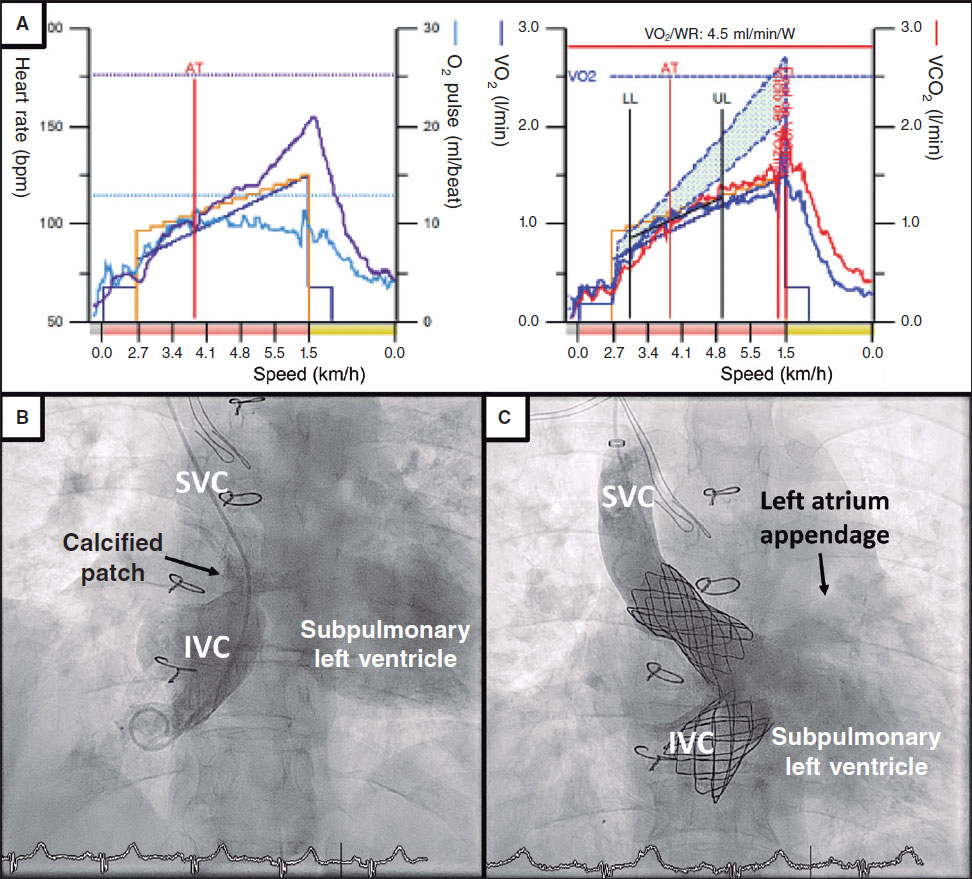

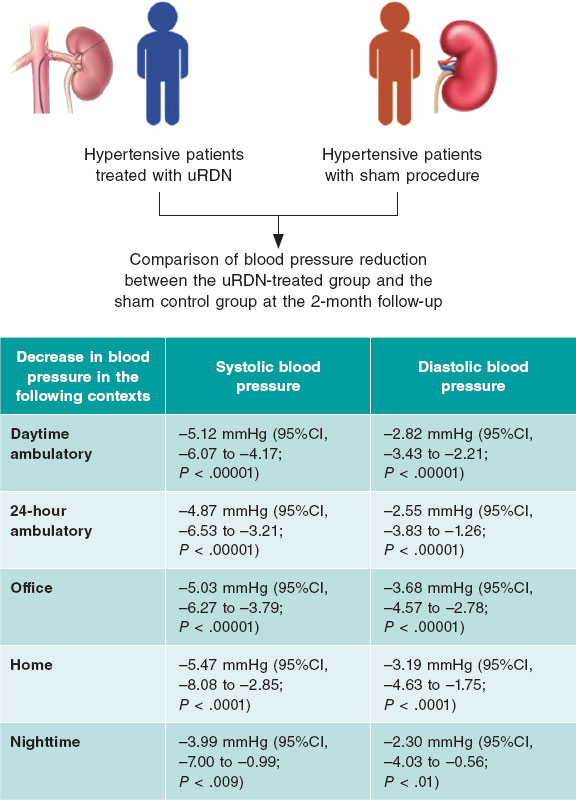

Daytime ambulatory blood pressure

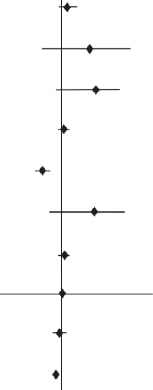

Patients treated with uRDN for up to 2 months experience a significant reduction of −5.12 mmHg (95%CI, −6.07 to −4.17; P < .00001); I2 = 2%) in daytime ambulatory SBP vs the sham group. Similarly, ambulatory diastolic blood pressure (DBP) dropped down to −2.82 mmHg (95%CI, −3.43 to −2.21; P < .00001; I2 = 0%) in patients with uRDN vs the sham group (figure 2A).

Figure 2. Meta-analysis of the effect of uRDN on blood pressure va a sham control. A: difference in daytime ambulatory BP up to 2 months; B: difference in 24-hour BP up to 2 months; C: difference in office BP up to 2 months; and D: difference in home BP up to 2 months. Forest plots showing the mean difference and SD from random assignments between the uRDN and sham control groups. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BP, blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; uRDN, ultrasound renal denervation. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Azizi et al.,16-18 and Kario et al.21

24-hour ambulatory blood pressure

24-h BP was evaluated up to 2 months after uRDN. Analysis of SBP showed a significant reduction of −4.87 mmHg (95%CI, −6.53 to −3.21; P < .00001; I2 = 42%). Meanwhile, 24-h DBP dropped down to −2.55 mmHg (95%CI, −3.83 to −1.26; P < .00001; I2 = 62%) in patients on uRDN (figure 2B).

Office blood pressure

SBP dropped down to −5.03 mmHg after 2 months (95%CI, −6.27 to −3.79; P < .00001; I2 = 0%) in uRDN patients. DBP showed a significant decrease of −3.68 mmHg (95%CI, −4.57 to −2.78; P < .00001; I2 = 31%) with the uRDN intervention (figure 2C).

Home blood pressure

Analysis of home BP after 2 months showed a decrease in SBP of −5.47 mmHg (95%CI, −8.08 to −2.85; P < .0001; I2 = 75%), while DBP dropped down to −3.19 mmHg (95%CI, −4.63 to −1.75; P < .0001; I2 = 69%) in patients on uRDN (figure 2D).

Nighttime blood pressure

Nighttime BP was evaluated at the 2-month follow-up. We found that SBP dropped down to −3.99 mmHg (95%CI, −7.00 to −0.99; P = 0.009; I2 = 70%), while DBP dropped down to −2.30 mmHg (95%CI −4.03 to −0.56; P = .01; I2 = 64%) in patients on uRDN (figure 2 of the supplementary data).

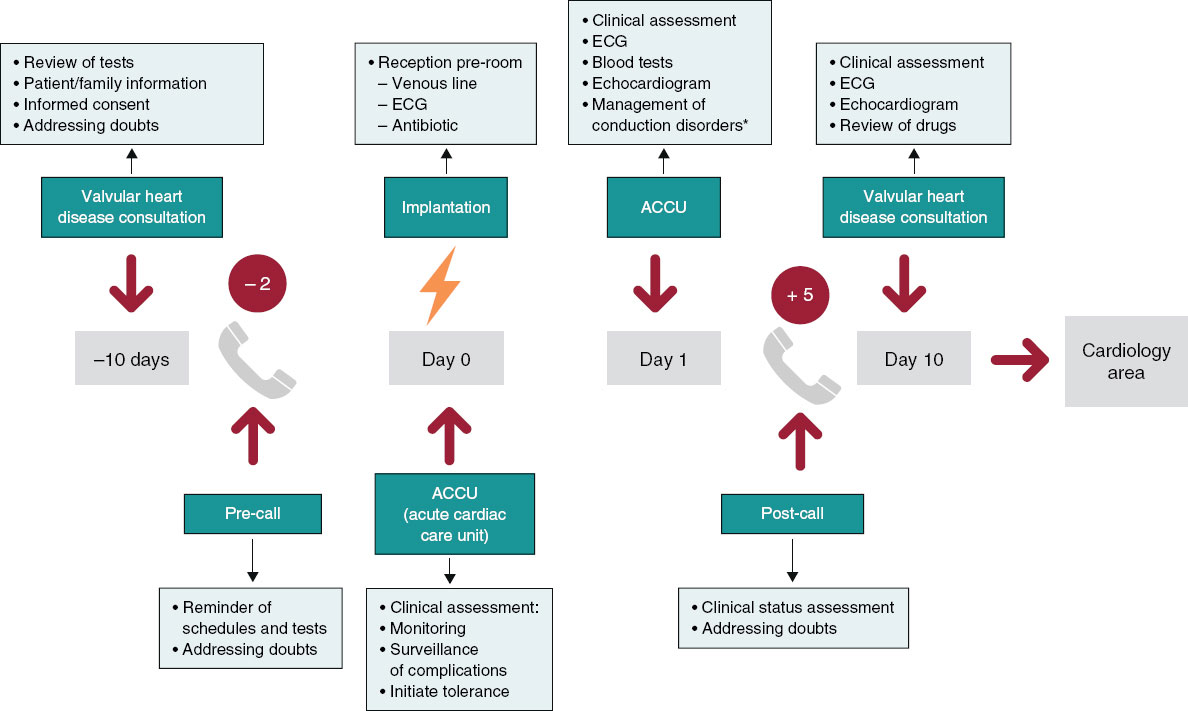

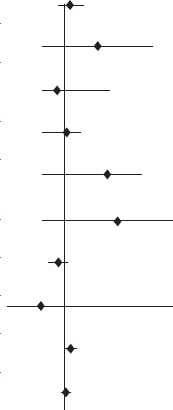

Drugs 6 months after uRDN

Patient drugs 6 months after uRDN were only reported in the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO and RADIANCE-HTN TRIO clinical trials. Data analysis revealed that uRDN leads to using fewer antihypertensive drugs by −0.52 (95%CI, −0.91 to −0.13; P = 0.009; I2 = 69%) vs the sham control group (figure 3).

Figure 3. Patients on uRDN used less antihypertensive medication prescribed 6 months after the procedure vs the sham group. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; BP, blood pressure; SD, standard deviation; uRDN, ultrasound renal denervation. The bibliographical references mentioned in this figure correspond to Azizi et al.16 and Azizi et al.17

Risk of bias assessment

Among the 4 studies included, the risk of bias remained consistent at a moderate level, which was attributed to the inability to blind the interventional cardiologist conducting the uRDN, although outcome assessors were blinded to the interventions performed. Studies were categorized as having moderate risk16-18,21 (table 3). Data on risk of bias can be found in table 1 of the supplementary data. In addition, the funnel plot of daytime ambulatory SBP (figure 1 of the supplementary data) showed a slight asymmetry, as points tend to concentrate towards the left side of the combined effect, which could suggest a possible publication bias. In addition, the points closer to the vertex represent studies with lower standard error due to a larger sample size. The heterogeneity of the funnel plot reflects variations in effects across studies. Plot points are within the funnel lines, but one of them towards the lower right seems further away from the rest, which could indicate a possible outlier or methodological or population differences.29

Table 3. Risk of bias summary for randomized studies (RoB 2)

| Trials | Risk of bias domains | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | D5 | Overall | |

| RADIANCE HTN SOLO16 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| RADIANCE HTN TRIO17 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| REQUIRE21 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| RADIANCE II18 | Some concerns | Low | Low | Low | Low | Some concerns |

|

D1: bias arising from the randomization process. D2: bias due to deviation from intended intervention. D3: bias due to missing outcome data. D4: bias in outcome measurement. D5: bias in selection of the reported result. |

||||||

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis includes data from 4 randomized controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy profile of uRDN in patients with true resistant hypertension and off-medication hypertensive patients vs a sham group. Antihypertensive efficacy was evaluated across different clinical settings such as 24-h ambulatory BP, home BP, office BP, and daytime BP. Our results demonstrated significant BP-lowering efficacy at the 2-month follow-up vs the sham procedure. Furthermore, at the 6-month follow-up, fewer antihypertensive drugs were prescribed to patients on uRDN vs those from the sham group. These results support the use of uRDN as an adjuvant therapy for hypertension and as a valuable option for reducing BP as well as the number of antihypertensive drugs.

Previous studies have demonstrated the safety profile of RDN for the treatment of resistant hypertension, such as the first-generation SIMPLICITY HTN trials.30 However, the SIMPLICITY HTN-3 study showed no differences in the 24-h BP reduction vs the sham group, casting doubts on the benefits of RDN.14 Subsequently, new catheters were developed for performing RDN, and standardized criteria were established for conducting RDN trials with a sham group.12,19 Currently, uRDN has emerged as a novel option as an adjuvant therapy treatment of hypertension. It is based on catheter systems, such as the TIVUS and Paradise systems, which utilize ultrasound energy for the thermal ablation of afferent and efferent renal nerves.19,31

Our results demonstrated a reduction in both SBP and DBP at the 2-month follow-up, with a more pronounced effect on SBP in patients on uRDN vs the sham control group. We observed a reduction of −5.12 mmHg in ambulatory SBP, −4.87 mmHg in 24-h SBP, −5.03 mmHg in office SBP, and −5.47 mmHg in home SBP. These findings are particularly relevant since SBP has turned out to be a strong predictor of future cardiovascular events and mortality, regardless of age in adults.32 The CI values for home BPS had the widest range. Furthermore, the RADIANCE HTN-SOLO trial demonstrated a wide CI in both office and home SBP. This observation is an opportunity for future trials to focus on patient training to standardize home BP measurement since day-to-day home BP has been proposed as a potential predictor of cardiovascular disease.33

Although the observed BP reduction may seem minimal and lack significant clinical relevance, it is important to note that these findings reflect the first 2 months of follow-up after uRDN initiation and literature reports that uRDN has a sustained long-term effect on lowering BP values. For example, the HTN RADIANCE-SOLO trial demonstrated that at the 36-month follow-up, office BP decreased 18/11 ± 15/9 mmHg.34 Related to this, previous studies have demonstrated that a 10 mmHg reduction in SBP is associated with a decrease in the relative risk (RR) of major cardiovascular events (RR, 0.80; 95%CI, 0.77-0.83), coronary heart disease (RR, 0.83; 95%CI, 0.78-0.88), stroke (RR, 0.73; 95%CI, 0.68-0.77), heart failure (RR, 0.72; 95%CI, 0.67-0.78), and a 13% reduction in all-cause mortality rate (RR, 0.87; 95%CI 0.84-0.91).2 However, it has recently been reported that even a 5 mmHg decrease is beneficial to reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events, estimating a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.91 (95%CI, 0.89-0.94) for individuals without previous cardiovascular disease and a HR of 0.89 (95%CI, 0.86-0.92) for those with previous cardiovascular disease.1 In addition, reduction of preventable major cardiovascular events by treating hypertension has a positive economic impact in reducing hospitalization expenses due to complications such as heart attack or stroke.35 Hypertension is a prevalent global health concern, and effective BP control is achieved in only 21% of patients.36 In the United States, individuals with hypertension are estimated to incur an additional $2500 to $3000 in annual expenses vs those without hypertension. Maintaining normal BP not only benefits patients but also supports the economic well-being of the entire health care system.37 In fact, studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of long-term use of radiofrequency RDN have been conducted in the United States and the United Kingdom concluding that this procedure represents a cost-effective option for the treatment of uncontrolled and resistant hypertension, as its sustained BP-lowering effect favors the reduction of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.38 Similarly, in Spain, an estimate was made of the impact of radiofrequency RDN on quality-adjusted life years, cardiac events, and patient-related lifetime costs. Radiofrequency RDN was found to reduce the risk of stroke (RR, 0.80), myocardial infarction (RR, 0.88), and heart failure (RR, 0.72) throughout a 10-year period, resulting in improved health outcomes and long-term cost savings. Results presented indicate that radiofrequency RDN is a cost-effective therapeutic option that should be taken into consideration in patients with uncontrolled hypertension, including resistant hypertension.39

In addition to the reduction in BP and the positive cost-effectiveness of uRDN, radiofrequency RDN has been demonstrated to be a safe procedure for the patients. The clinical trials that analyzed this meta-analysis found no safety differences between the treated and sham groups. Furthermore, few postoperative adverse events were reported. Most complications were associated with back pain, which was effectively and uneventfully managed.16-18,21 The long-term safety profile of the procedure has been consistently reported, with no adverse effects being reported from uRDN observed at the 1, 3-, and even 8-year follow-up.34,40,41

Our findings also demonstrated that, at the 6-month follow-up, patients on uRDN used fewer prescribed antihypertensive drugs, which suggests that treatment may potentially improve patient outcomes. However, this outcome was only evaluated in the RADIANCE HTN-TRIO and RADIANCE HTN-SOLO trials. In addition, at the 3-year follow-up the RADIANCE HTN-TRIO reported no differences in the number of drugs used by patients initially identified with uncontrolled hypertension, although they decreased office SBP by 10.8 mmHg.34 This is particularly noteworthy as non-adherence to therapy is a significant contributing factor to uncontrolled BP.42 However, the results suggest that the greatest benefit is observed in the maintenance of low BP levels rather than in the decrease in the number of antihypertensive drugs prescribed.

Of note, the I2 value of the outcomes evaluated showed that daytime SBP and DBP had low heterogeneity, while the 24-h SBP and DBP values had moderate-to-high heterogeneity. On the other hand, office SBP and DBP had low-to-moderate heterogeneity. Finally, home SBP and DBP, as well as nighttime SBP and DBP and drug intake had high heterogeneity. Variations in heterogeneity do not necessarily indicate that the results are not useful;43 possibly, the differences in the heterogeneity of the outcomes assessed is due to differences in the methodology of the studies contemplated in this meta-analysis, which will be discussed below.

Our analysis included the REQUIRE trial, which has certain limitations, such as the absence of a blinded design, a non-standardized uRDN intervention, and dose titration. These factors may have introduced bias, potentially explaining the lack of differences observed between the uRDN and sham groups. In addition, the inclusion criteria of the study did not consider the presence of anatomical variations in the renal arteries vs the RADIANCE trials in which an exclusion criterion is the presence of anatomical variations in renal arteries. This factor, along with therapeutic adherence, could impact the BP reduction results.21,28,44 Based on this perspective, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Council on Hypertension and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) have established the characteristics that must be met by studies evaluating RDN with a sham control group to be considered as high quality: a) multicenter design; b) blinding of patients; c) ambulatory BP change as the primary enpoint; d) use of second-generation RDN systems.10 In this context, RADIANCE clinical trials are characterized by a rigorous methodological protocol, which required a 4- or 8-week stabilization of pharmacological therapy prior to randomization to either uRDN or a sham procedure.45,46 Furthermore, RADIANCE trials monitored therapeutic adherence and were designed to assess the effect of uRDN with and without antihypertensive treatment, minimizing the confounding effects.28,47

A key long-term challenge of the RADIANCE trials is to demonstrate sustained BP-lowering effects vs sham groups. Follow-up studies show that patients from the sham group required higher doses of antihypertensive drugs, while those on uRDN used fewer drugs. Although BP differences across groups decreased throughout time, uRDN patients consistently needed fewer prescriptions.26,27

Results from the RADIANCE trials demonstrate the efficacy profile of uRDN for the treatment of resistant hypertension and patients with poor therapeutic adherence, as observed in the off-study population. Additionally, the REQUIRE trial highlights the potential role of anatomical variations in determining patient suitability for uRDN, underscoring the importance of selecting appropriate criteria for patient selection. In addition, RDN has proven to be a safe procedure with a positive long-term cost-benefit ratio. The key question on uRDN may be: Which patient group would benefit most from uRDN, considering anatomical factors and therapeutic adherence?

Study limitations

To make the most out of the study results, it is important to consider its limitations: a) we only analyzed data from trials that used uRDN, which reduces the size of the population; b) data availability from the studies considered covered a short follow-up period, which limits the ability to determine the long-term antihypertensive efficacy of uRDN; c) differences in supervised drug adherence across the methodological designs limit their applicability to real-world settings; d) Since RCTs included patients with true resistant hypertension and off-med hypertension, the heterogeneous population limits the generalizability of the results to a specific hypertension subtype; and e) The funnel plot showed asymmetry, suggesting a possible publication bias, although results should be interpreted with caution because the funnel plot also indicates that there is a limited amount of data.

CONCLUSIONS

This meta-analysis demonstrates that uRDN treatment effectively reduces both SBP and DBP across various contexts, including 24-h, ambulatory, home and office BP at the initial 2-month follow-up in hypertensive patients (figure 4). Additionally, uRDN was associated with reduced antihypertensive drug use 6 months after the procedure. However, further research is needed to assess its long-term effects and identify the patient groups who may benefit the most.

Figure 4. Central illustration. Summary of the effect on the decrease in systolic and diastolic blood pressure in patients on uRDN compared with patients who received the sham procedure at the 2 months postoperative follow-up. uRDN, ultrasound renal denervation.

FUNDING

This manuscript did not receive financial support from any institution or funding agency for its preparation.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

The present meta-analysis was conducted based on previously published studies. As the study involved secondary data analysis, no new data was collected from human participants or animals, and the use of SAGER guidelines does not apply to this study. Therefore, ethical approval was deemed unnecessary. All included studies were reviewed in full compliance with ethical guidelines set forth by the respective institutions where the original studies were conducted. All authors state that the data used in this study were obtained exclusively from publicly accessible sources, and no confidential or proprietary information was utilized without appropriate authorization.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-4o to review the document syntaxis and grammar. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and took full responsibility for the content of the published article.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

J.M. Guerrero-Hernández: conceptualization, formal analysis, drafting, review and editing; C. J. Palomino-Ojeda: methodology, investigation, drafting, review and editing; L. H. García-Mena: methodology, formal analysis, writing, review and editing; Ó.Á. Vedia-Cruz: investigation; J. L. Maldonado-García: drafting, review and editing; I. J. Núñez-Gil: investigation, supervision and review; J. A. García-Donaire: review and supervision.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

I. J. Núñez-Gil served as a consultant for Medtronic and Recor Medical in the denervation field. J. A. García-Donaire served as consultant for Medtronic and Recor Medical in the denervation field. The rest of the authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- uRDN has emerged as a safe option for the treatment of resistant hypertension, and previous studies have observed greater efficacy in lowering BP vs a sham group.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Our results demonstrate that uRDN decreased 24-h, office, daytime and home SBP and DBP within the first 2 months after the procedural follow-up vs a sham group, and a decrease in the number of antihypertensive drugs at the 6-month follow-up. However, further long-term studies are required to confirm the benefit of uRDN.

REFERENCES

1. Adler A, Agodoa L, Algra A, et al. Pharmacological blood pressure lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure:an individual participant-level data meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2021;39:1625-1636.

2. Ettehad D, Emdin CA, Kiran A, et al. Blood pressure lowering for prevention of cardiovascular disease and death:A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2016;387:957-967.

3. Carey RM, Muntner P, Bosworth HB, Whelton PK. Prevention and Control of Hypertension:JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1278-1293.

4. Choudhry NK, Kronish IM, Vongpatanasin W, et al. Medication adherence and blood pressure control:A scientific statement from the american heart association. Hypertension. 2022;79:E1-E14.

5. Egan BM, Zhao Y, Li J, et al. Prevalence of optimal treatment regimens in patients with apparent treatment-resistant hypertension based on office blood pressure in a community-based practice network. Hypertension. 2013;62:691-697.

6. Flack JM, Buhnerkempe MG, Moore KT. Resistant Hypertension:Disease Burden and Emerging Treatment Options. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2024;26:183-199.

7. Grassi G, Ram VS. Evidence for a critical role of the sympathetic nervous system in hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:457-466.

8. Mabin T, Sapoval M, Cabane V, Stemmett J, Iyer M. First experience with endovascular ultrasound renal denervation for the treatment of resistant hypertension. EuroIntervention. 2012;8:57-61.

9. Dasgupta I, Sharp ASP. Renal sympathetic denervation for treatment of hypertension:where are we now in 2019? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2019;28:498-506.

10. Barbato E, Azizi M, Schmieder RE, et al. Renal denervation in the management of hypertension in adults. A clinical consensus statement of the ESC Council on Hypertension and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J. 2023;44:1313-1330.

11. Rodríguez-Leor O, Jaén-Águila F, Segura J, et al. Renal denervation for the management of hypertension. Joint position statement from the SEH-LELHA and the ACI-SEC. REC Interv Cardiol. 2022;4:39-46.

12. Schmieder R, Burnier M, East C, Tsioufis K, Delaney S. Renal Denervation:A Practical Guide for Health Professionals Managing Hypertension. Interv Cardiol. 2023;18:e06.

13. Azizi M, Sapoval M, Gosse P, et al. Optimum and stepped care standardised antihypertensive treatment with or without renal denervation for resistant hypertension (DENERHTN):a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1957-1965.

14. Bhatt DL, Kandzari DE, O'Neill WW, et al. A Controlled Trial of Renal Denervation for Resistant Hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1393-1401.

15. Stiermaier T, Okon T, Fengler K, et al. Endovascular ultrasound for renal sympathetic denervation in patients with therapy-resistant hypertension not responding to radiofrequency renal sympathetic denervation. EuroIntervention. 2016;12:e282-e289.

16. Azizi M, Schmieder RE, Mahfoud F, et al. Endovascular ultrasound renal denervation to treat hypertension (RADIANCE-HTN SOLO):a multicentre, international, single-blind, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2018;391:2335-2345.

17. Azizi M, Sanghvi K, Saxena M, et al. Ultrasound renal denervation for hypertension resistant to a triple medication pill (RADIANCE-HTN TRIO):a randomised, multicentre, single-blind, sham-controlled trial. Lancet. 2021;397:2476-2486.

18. Azizi M, Saxena M, Wang Y, et al. Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation to Treat Hypertension:The RADIANCE II Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023;329(8):651-661.

19. Lauder L, Kandzari DE, Lüscher TF, Mahfoud F. Renal denervation in the management of hypertension. EuroIntervention. 2024;20:E467-E478.

20. Reuter E. The FDA approved 2 renal denervation devices. There are still questions about who will benefit. MedTech Dive. 13 Dec 2023. Available at:https://www.medtechdive.com/news/renal-denervation-recor-medtronic-evidence/702385/. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

21. Kario K, Yokoi Y, Okamura K, et al. Catheter-based ultrasound renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension:the randomized, controlled REQUIRE trial. Hypertens Res. 2022;45:221-231.

22. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). Cochrane;2023. Avalilable at:https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. Accessed 1 Dec 2024.

23. Sterne JAC, Savovic´J, Page MJ, et al. RoB 2:a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366.

24. Wilson DB. Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator (Version 2023.11.27). 2023. Available at:https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/calculator/d-ordinal-freq. Accessed 20 Dec 2024.

25. DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188.

26. Azizi M, Schmieder RE, Mahfoud F, et al. Six-Month Results of Treatment-Blinded Medication Titration for Hypertension Control After Randomization to Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation or a Sham Procedure in the RADIANCE-HTN SOLO Trial. Circulation. 2019;139:2542-2553.

27. Azizi M, Mahfoud F, Weber MA, et al. Effects of Renal Denervation vs Sham in Resistant Hypertension After Medication Escalation:Prespecified Analysis at 6 Months of the RADIANCE-HTN TRIO Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:1244.

28. Mauri L, Kario K, Basile J, et al. A multinational clinical approach to assessing the effectiveness of catheter-based ultrasound renal denervation:The RADIANCE-HTN and REQUIRE clinical study designs. Am Heart J. 2018;195:115-129.

29. Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002.

30. Epstein M, De Marchena E. Is the failure of SYMPLICITY HTN-3 trial to meet its efficacy endpoint the “end of the road“for renal denervation? J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:140-149.

31. Haribabu S, Sharif F, Zafar H. Recent trends in renal denervation devices for resistant hypertension treatment. Ir J Med Sci. 2021;190:971-979.

32. McCarthy CP, Natarajan P. Systolic Blood Pressure and Cardiovascular Risk:Straightening the Evidence. Hypertension. 2023;80:577-579.

33. Kario K, Kanegae H, Okawara Y, Tomitani N, Hoshide S. Home Blood Pressure Variability Risk Prediction Score for Cardiovascular Disease Using Data From the J-HOP Study. Hypertension. 2024;81:2173-2180.

34. Rader F, Kirtane AJ, Wang Y, et al. Durability of blood pressure reduction after ultrasound renal denervation:three-year follow-up of the treatment arm of the randomised RADIANCE-HTN SOLO trial. EuroIntervention. 2022;18:E677-E685.

35. Wang G, Grosse SD, Schooley MW. Conducting Research on the Economics of Hypertension to Improve Cardiovascular Health. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(6 Suppl 2):S115.

36. Kario K, Okura A, Hoshide S, Mogi M. The WHO Global report 2023 on hypertension warning the emerging hypertension burden in globe and its treatment strategy. Hypertens Res. 2024 47:5. 2024;47:1099-1102.

37. Kumar A, He S, Pollack LM, et al. Hypertension-Associated Expenditures Among Privately Insured US Adults in 2021. Hypertension. 2024;81:2318-2328.

38. Taylor RS, Bentley A, Metcalfe K, et al. Cost Effectiveness of Endovascular Ultrasound Renal Denervation in Patients with Resistant Hypertension. Pharmacoecon Open. 2024;8:525.

39. Rodríguez-Leor O, M. Ryschon A, N. Cao K, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of radiofrequency renal denervation for uncontrolled hypertension in Spain. REC Interv Cardiol. 2024;6:305-312.

40. M Zeijen VJ, Völz S, Zeller T, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of endovascular ultrasound renal denervation in resistant hypertension:8-year results from the ACHIEVE study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-024-02555-7.