ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has revolutionised the treatment of severe symptomatic aortic stenosis, providing an alternative to surgical valve aortic replacement, especially in high-risk patients. Despite its benefits, significant interregional variability in TAVI access persists within Spain. This study aimed to analyse disparities in TAVI implementation across different autonomous communities, identifying the key factors underlying this variability.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective observational study using data from the Spanish National Registry of Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set for 2016–2023, including all TAVI performed in Spain. Additionally, a survey was distributed among specialists from 123 centres to assess the factors influencing clinical decision-making, barriers to access, and resource availability.

Results: Although the number of TAVI increased across all regions, significant differences were observed in the implantation rates (between 0.63 and 2.28 per 10 000 inhabitants). Survey responses indicated that the primary determinants for TAVI indication were heart team judgment (40.0%) and patient risk stratification (36.5%). The main barriers to expanding TAVI access included rigid patient stratification (25.6%), insufficient early detection (17.8%), and resource limitations (13.3%). Participants emphasized the need for better coordination among health care levels and establishing uniform access criteria.

Conclusions: Although TAVI adoption has increased in Spain, significant regional disparities remain, suggesting factors beyond economics contribute to access variability. Addressing these inequalities requires enhanced coordination across different health care levels, optimized resource allocation, and refined patient selection strategies.

Keywords: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Aortic valve stenosis. Health inequities. Health services accessibility. Delivery of health care.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) ha revolucionado el tratamiento de la estenosis aórtica grave sintomática, ofreciendo una alternativa al reemplazo quirúrgico, en especial en pacientes de alto riesgo. A pesar de sus beneficios, persiste una significativa variabilidad interregional en el acceso al TAVI en España. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo analizar las disparidades en la implementación del TAVI entre las distintas comunidades autónomas, e identificar los factores determinantes de la variabilidad.

Métodos: Se realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo con datos del Registro de Actividad de Atención Especializada Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos para el periodo 2016-2023, abarcando todos los procedimientos de TAVI realizados en España. Además, se distribuyó una encuesta entre especialistas de 123 centros para evaluar los factores que pueden influir en la toma de decisiones clínicas, las barreras de acceso y la disponibilidad de recursos.

Resultados: El número de procedimientos de TAVI aumentó en todas las regiones, pero se observaron diferencias significativas en las tasas de implantación, que se situaron entre 0,63 y 2,28 por 10.000 habitantes. Las respuestas de la encuesta indicaron que los principales determinantes para la indicación de TAVI fueron el criterio del equipo médico (40,0%) y la estratificación del riesgo del paciente (36,5%). Las principales barreras para incrementar el acceso al TAVI incluyeron la estratificación rígida de los pacientes (25,6%), la detección temprana insuficiente (17,8%) y las limitaciones de recursos (13,3%). Los participantes subrayaron la necesidad de mejorar la coordinación entre los niveles asistenciales y la estandarización de los criterios de acceso.

Conclusiones: Aunque la adopción del TAVI en España ha crecido, persisten importantes disparidades regionales que no pueden explicarse únicamente por factores económicos. Para abordar estas desigualdades es necesario mejorar la coordinación entre niveles asistenciales, optimizar la asignación de recursos y perfeccionar las estrategias de selección de pacientes.

Palabras clave: Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Estenosis de válvula aórtica. Inequidades en salud. Accesibilidad de los servicios de salud. Atención a la salud.

Abbreviations

AC.: autonomous communities. AS: aortic stenosis. SNS: Spanish National Health Service. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular heart disease, with a prevalence of 3% in individuals older than 65 years and 7.4% in those older than 85 years. AS is more common in men.1,2 It is the leading cause of valve surgery in the adult population,3 and is associated with risk factors such as advanced age.4,5 Although aortic stenosis typically develops after age 60, symptoms usually present between ages 70 and 80; once symptoms occur, the mortality rate may reach 50% within the next few years.4,6

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), initially reserved for patients deemed ineligible for surgical aortic valve replacement,7-11 was subsequently expanded to include those at intermediate risk and, more recently, patients at low risk.5,12-14

In Spain, the use of TAVI has increased,5 reflecting its growing acceptance within the Spanish National Health System (SNS), largely attributable to improved clinical and economic outcomes.5,15 Multiple studies have demonstrated the benefits of TAVI, including significant improvements in quality of life,16,17 lower rates of major complications,18 and reduced mortality.5,19,20

Nationwide, improvements in TAVI outcomes, shorter lengths of stay, and lower mortality rates have been reported. Furthermore, autonomous communities (AC) with higher implant volumes have a better safety and efficacy profile, lower risks of infection, reduced need for permanent pacemaker implantation, and shorter lengths of stay.5 However, the distribution of TAVI reveals notable interregional disparities, with procedural rates varying considerably according to hospital resources and volumes.21

Despite these advances, in Spain, TAVI use remains significantly lower compared with other European countries.22 Furthermore, Spain exhibits one of the highest variations in access and utilization rates among its AC (42%), which cannot be explained solely by economic differences, hospital utilization, or observed mortality.21 An analysis by de la Torre Hernández et al.21 described the need for strategies to promote equity in TAVI access across Spain.

This study analyzed heterogeneity in the use of TAVI across AC (2016–2023) and identified the factors associated with this inequality.

METHODS

TAVI data in Spain from 2016 through 2023

Data on TAVI performed from 2016 to 2023 were obtained from the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set23-25 using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision for Spain (ICD-10-ES) (supplementary data 1). This mandatory registry, which includes all specialized care centers, is managed by the Spanish Ministry of Health and ensures strict compliance with privacy and data protection standards. The analysis included all TAVI performed in public and private hospitals across AC.

Survey

Simultaneously, we designed a survey to gather information on therapeutic decision-making in patients with AS to identify possible factors influencing TAVI implementation and interregional variability previously observed. This survey was distributed to department heads of the 123 medical centers affiliated with the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Respondents were asked to extend the invitation to other department members to ensure representative and diverse responses.

The survey (supplementary data 2) covered clinical, structural, organizational, and patient-related aspects relevant to clinical practice during the study period, and was structured into 3 thematic blocks:

- – Center and participant characteristics (questions A1–C3): evaluation of institutional context and department composition, including variables such as the respondent’s specialty and annual budget allocation.

- – Patient selection and decision-making (questions C4–E2): identification of key clinical and demographic factors influencing therapeutic choice, as well as barriers and determinants shaping clinical team decisions.

- – Center evaluation and TAVI use (questions E3–F9): assessment of clinician perception and satisfaction regarding TAVI, and exploration of adoption, implementation, and geographic distribution of this strategy.

Responses were analyzed descriptive and qualitatively, allowing a comprehensive interpretation of factors influencing TAVI implementation and interregional heterogeneity.

RESULTS

TAVI in 2016–2023

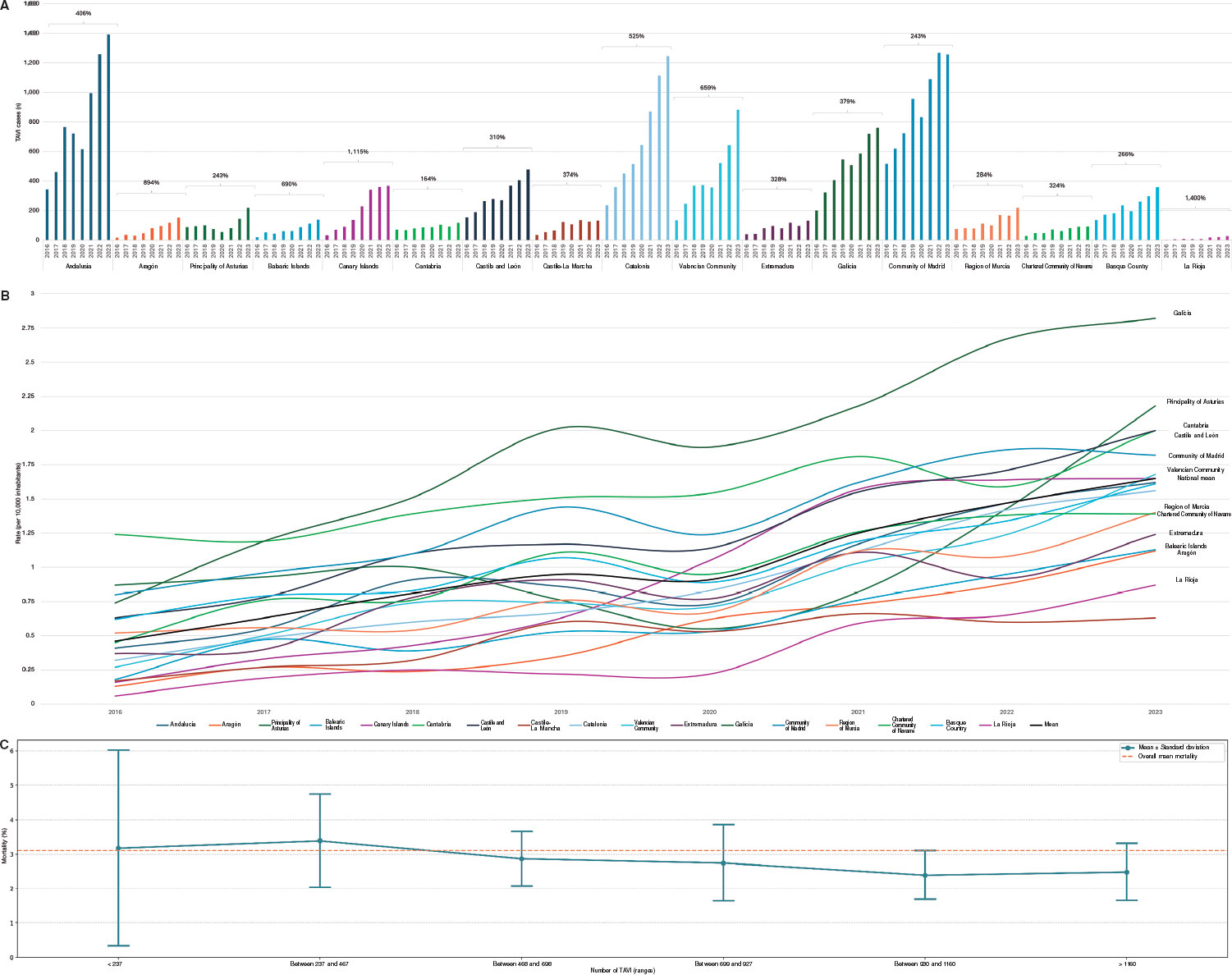

The results of TAVI interventions, expressed as the number of cases and intervention rates per 10 000 inhabitants, are shown in figure 1. All AC experienced an increase in procedures during the study period (figure 1A), with the greatest growth observed in the Canary Islands (33 cases in 2016 and 368 in 2023) and La Rioja (2 cases in 2016 and 28 in 2023), corresponding to increases of 1.115% and 1.400%, respectively. The AC with the highest number of TAVI performed in 2023 were Andalusia (n = 1392), Catalonia (n = 1245), and the Community of Madrid (n = 1257). La Rioja had the fewest (2 cases in 2016, 28 in 2023).

Figure 1. A: total number of transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) cases by autonomous community and year (2016–2023). B: population-adjusted procedural rates adjusted (per 10 000 inhabitants) by autonomous community and year (2016–2023). C: mean and dispersion of mortality based on the number of TAVI.

Procedure rates (figure 1B) indicated that, in 2023, the AC with the highest per capita TAVI volumes were Galicia (2.82 per 10 000 inhabitants), Asturias (2.18 per 10 000), Cantabria (2.00 per 10 000), Castile and León (2.00 per 10 000), and Madrid (1.82 per 10 000), all above the national average (1.65 per 10 000). The lowest per capita TAVI volumes were found in Extremadura (1.24 per 10 000), the Balearic Islands (1.13 per 10 000), Aragón (1.12 per 10 000), La Rioja (0.87 per 10 000), and Castile-La Mancha (0.63 per 10 000).

The mean in-hospital mortality rate during the study period was 3.07% (figure 1C).

Survey

Center and participant characteristics

The survey was completed by 26 specialists with different TAVI-related profiles: 18 in interventional cardiology, 7 in clinical cardiology, and 1 in cardiac imaging, including 4 heads of cardiac surgery departments and 18 cath lab directors. The respondents’ mean professional experience was 26.5 years (range, 9–41 years) and worked in hospitals with a mean TAVI experience of 10.6 years (range, 1–16 years). Responses were obtained from hospitals in 11 of the 17 AC (64.7% of the national territory). Team composition by professional profile is provided in supplementary data 3.

Teams performed a mean of 76 TAVI (range, 0–148) in 2021 and 95 (range, 0–254) in 2022, with marked variation across hospitals. Annual budgets allocated to units ranged from €474 765 to €25 111 709, reflecting wide disparities in resource availability. Despite these differences, most respondents reported being satisfied with the extent to which purchasing committees allocated budgets to meet their teams’ clinical needs (19.2%, very satisfied; 42.3%, quite satisfied; 34.6%, moderately satisfied; 3.9%, unsatisfied).

Most participants rated continuity of care across different settings as good or improvable (54.9% and 38.5%, respectively) and gave examples of best practices as well as areas for improvement. Best practices included teleconsultation, specialized programs such as TAVI Nurse,26 periodic cross-level meetings, and shared protocols between primary and hospital care. Suggested improvements included insufficient coordination between primary and specialized care, overloaded schedules, and the need to improve clinical information systems such as integrating joint activities.

Patient selection and decision-making

The clinical indication for TAVI was determined primarily by heart team judgment (40.0%) and patient stratification (36.5%), followed by patient preference (12.5%) and resource availability (10.4%). Barriers to expanding TAVI included rigid patient stratification (25.6%), insufficient early detection (17.8%), intra-team discrepancies (14.2%), insufficient budget (13.3%) and technology (11.8%), and obstacles to multidisciplinary team integration (7.4%).

Most centers had decision-support tools for TAVI (76.9%) and specific training programs (65.4%). Tools included decision algorithms, clinical practice guidelines, consensus protocols, and software for anatomical, feasibility, and comorbidity assessment. Specific training and periodic multidisciplinary meetings were also in place.

Most centers (76.9%) conducted periodic evaluations of outcomes—described as continuous process evaluation—to optimize procedures, including registries, internal audits, analysis of complications, in-hospital mortality, and readmissions. Annual and monthly clinical meetings allowed protocol adjustments and improved care processes, with high adherence to international clinical practice guidelines.

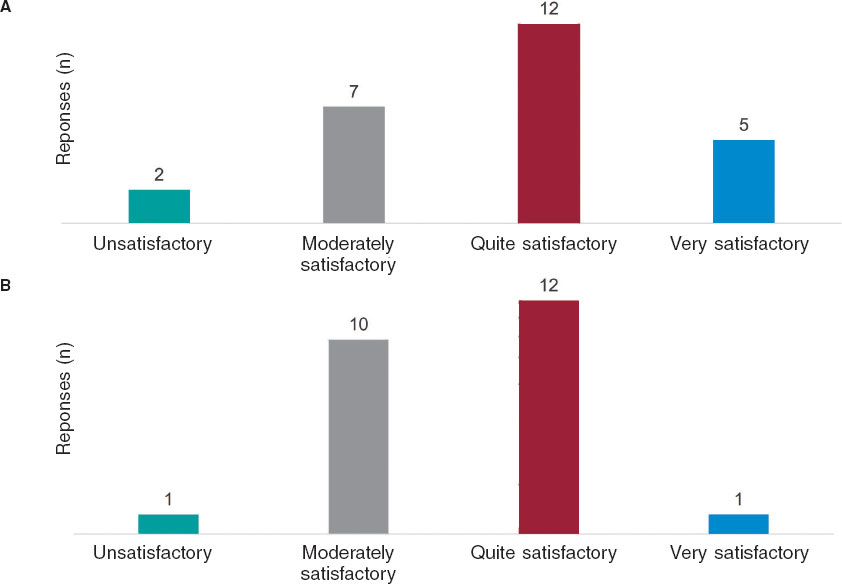

On the other hand, respondents indicated limited satisfaction with information exchange among departments and specialists involved in TAVI decision-making (figure 2A).

Figure 2. A: respondents’ evaluation of information exchange across departments, committees, and professionals involved in decision-making for aortic valve replacement. B: respondents’ evaluation of information exchange and best practices across centers performing transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Spain.

The survey on patient profiles treated with TAVI, which is performed primarily in intermediate- and high-risk patients, showed that 96.2% of centers treat high-risk patients; 76.9%, intermediate-risk patients; and only 30.8%, low-risk patients. In general, although no major barriers to treatment based on risk profile were reported (69.3% responded negatively), some resistance from cardiac surgery (n = 5), disagreement with institutional protocols (n = 4), and infrastructure limitations expressed as restricted availability of cath labs (n = 3) were noted.

Similarly, respondents perceived that the professional background of team members influences clinical decision-making for TAVI (63.6% strongly agreed and 27.3% moderately agreed; n = 11), highlighting the importance of training, experience, and individual performance. Multidisciplinary, consensus-based decisions among specialists in clinical cardiology, imaging, interventional cardiology, and cardiac surgery allow for the consideration of specific anatomic and clinical factors. Although such multidisciplinary teams promote more objective decision-making, participation from cardiac surgery may affect the indication in low-risk patients.

Therefore, participants considered the heart team’s judgment on additional factors in the indication for TAVI to be relevant, rating it as fairly (50%) or very relevant (50%). Similarly, respondents reported overall satisfaction with the process by which clinical decisions were made within the team: 53.8% found it fairly satisfactory; 38.5%, very satisfactory; 7.7%, moderately satisfactory.

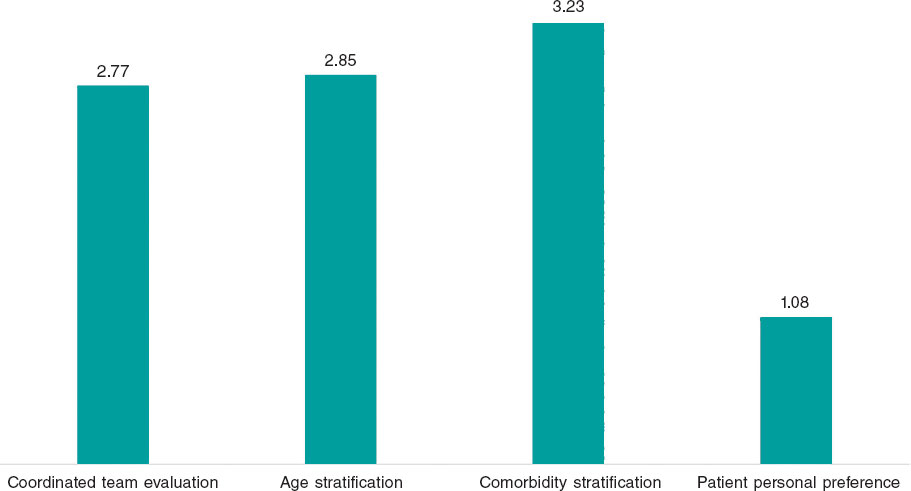

There was near-unanimous agreement (96%) on the importance of incorporating the patient’s opinion into the decision-making process for TAVI indication. When ranking the key factors guiding clinical decision-making, comorbidity and age stratification were rated as the most relevant (figure 3).

Figure 3. Weighted average of responses ranking factors by relevance in the clinical decision to indicate transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

The leading criteria for inclusion on the TAVI waiting list were the presence of comorbidities (n = 22), clinical status or overall risk (n = 20), followed by the minimum (n = 17) and maximum age threshold (n = 2).

The mean waiting time for the procedure was approximately 2 months (mean, 1.92 months; range, 0–4 months). Compared with surgical aortic valve replacement, the waiting list was generally perceived as shorter (50.0%) or equivalent (26.9%).

The primary factors influencing waiting time for TAVI were the need for computed tomography (n = 7) and cath lab availability (n = 5). Other factors included computed tomography availability (n = 3), anesthesia availability (n = 3), and waiting list length (n = 2). In line with this, respondents indicated that most patients (88.5%) undergo TAVI as scheduled procedures

Center evaluation and TAVI use

Most respondents considered the number of centers performing TAVI in Spain sufficient (n = 18, 24 respondents) and highlighted the importance of ensuring adequate procedural volume per center to optimize outcomes and minimize complications. Strengthening infrastructure, human resources, and networking was considered essential, prioritizing quality and safety over opening new centers.

Likewise, participants were generally satisfied with the exchange of information and best practices among TAVI centers in Spain (figure 2B).

There was consensus that improving the early detection of AS would, in turn, improve outcomes and patient experience (91.7%; n = 24). Conversely, most considered that regulatory thresholds for accrediting centers would not substantially affect total TAVI volume (62.5%; n = 24).

Finally, participants shared additional considerations. They emphasized prioritizing safety and clinical outcomes in TAVI programs beyond simply increasing the number of available centers. Although concentration of procedures in high-volume centers was suggested to improve health outcomes, it could also reduce the total number of procedures. The need for audits and dissemination of risk-adjusted results was highlighted to ensure transparency and care quality. Lastly, concern was expressed about the impact of health system fragmentation on equity of access.

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms the upward trend in TAVI implantation in Spain, which is consistent with previous research.5,22 From 2016 through 2023, the number of procedures increased in all AC, reflecting broader acceptance of this technique within the SNS. This trend is attributed to the consolidation of TAVI as a reference therapeutic alternative for the treatment of severe symptomatic AS, progressively expanding from high-risk to intermediate- and low-risk patients.12-14

Despite this generalized increase, results show notable interregional variability in TAVI rates. In 2023, some AC reported procedural rates well above the national average, while others were considerably lower. This inequality has been documented previously and suggests a key role for organizational factors in determining access to the procedure.21 Of note, in regions such as La Rioja, the absence of local cardiac surgery centers may partly explain the low number of TAVI. However, this does not mean that patients are not treated; rather procedures are performed in neighboring AC.

From a clinical perspective, multiple studies have shown that TAVI reduces in-hospital mortality, improves quality of life, and decreases the rate of major complications.16-20 Although these outcomes were not directly assessed in the present study, former studies have identified a relationship between higher procedural volume and improved outcomes, including reduced infection risk, decreased pacemaker need, and a shorter length of stay.5 Our analysis does not allow a direct correlation to be established between procedural volume and quality of care in Spain. This suggests that, although cumulative experience is a determinant of improved outcomes, other organizational and resource-management factors may also contribute to the observed discrepancies. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that as TAVI volume increases, the variability in mortality outcomes tends to diminish, suggesting greater standardization of practice and reduced variability across more experienced centers.

The survey analysis revealed that TAVI indication in Spain continues to depend primarily on physician judgment and patient risk stratification, with less influence from patient preference or resource availability. These findings are consistent with former studies underscoring the importance of multidisciplinary clinical judgment in decision-making, which results in patient selection aligned with clinical practice guidelines and safety criteria.27 However, organizational barriers hindering the expansion of TAVI were identified, including rigid patient stratification, insufficient identification of candidates, and difficulties integrating heart teams. Such limitations have previously been recognized as determinants of inequality in TAVI access in Spain,21 reinforcing the need for strategies to optimize care.

From a financial perspective, TAVI has been shown to be cost-effective compared with conventional surgical aortic valve replacement across various clinical scenarios.15,28 In our study, however, participants did not identify financing as a major barrier to expansion. This finding is consistent with prior Spanish investigations, which found no clear correlation between regional health spending and TAVI rates,5,21 suggesting that variability is more strongly influenced by organizational rather than economic factors.

The perception of infrastructure is relevant too, as most respondents considered the number of centers performing TAVI in Spain sufficient, while emphasizing the importance of guaranteeing a minimum procedural volume per center to optimize outcomes and minimize complications. Former studies have highlighted that cumulative team experience can improve clinical outcomes.27 However, no consensus was reached in this study on whether concentrating procedures in a smaller number of centers would favor equity of access or, conversely, limit availability in regions with restricted supply.

With respect to continuity of care, both advances and opportunities for improvement were identified. While > 90% of specialists positively evaluated the implementation of teleconsultation, specialized nursing programs (TAVI Nurse26), and shared protocols across levels of care, participants also emphasized the need to strengthen coordination between primary and specialized care, improve clinical information systems, and optimize scheduling management. These aspects have previously been highlighted as important for improving the efficiency of TAVI care processes5 and identified as cross-cutting priorities in the 2022 report of the SNS, Estrategia en Salud Cardiovascular.29

Limitations

This study has certain limitations. First, although the analysis of the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data provides information on overall TAVI trends, the Spanish Ministry of Health’s statistical portal does not include detailed patient-level clinical data, thus preventing assessment of outcomes such as complications.

Second, although the survey was designed to achieve representation from all AC, responses were obtained from only 11 of them (26 of 123 [21%] affiliated centers of the Interventional Cardiology Association), meaning that the perceptions and experiences reflected are drawn from a subset of regions, which may influence interpretation of certain findings. Nevertheless, this limitation is inherent to survey-based research, as participation greatly depends on availability and willingness of respondents. Despite this, the sample offers a representative perspective on organizational and clinical factors influencing variability in TAVI access within the SNS.

Finally, sex and gender variables were not considered in accordance with the SAGER guidelines, as the focus was on regional differences across AC. Future studies should explore sex- and gender-related influences on TAVI implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings reflect sustained growth in TAVI implementation in Spain, alongside marked interregional variability in procedural rates. Patient selection is driven primarily by physician judgment and clinical risk, while barriers to expansion are more organizational than financial. Key strategies are suggested to reduce regional variability and ensure equitable TAVI access within the SNS, including improved coordination across different levels of care, standardization of selection criteria, and strengthened resource management.

FUNDING

This work was funded by Edwards Lifesciences.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Approval from the study ethics committee was deemed unnecessary, as it used administrative data from the Spanish Ministry of Health without accessing patient-level data. Similarly, informed consent was deemed unnecessary. Sex and gender variables were not analyzed in accordance with the SAGER guidelines, as the study focused on regional differences across AC.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used in this study.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors were involved in the study design. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo requested the data and implemented the web-based survey. O. Martínez-Pérez conducted data analysis. All authors reviewed and validated the results. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

J.M. de la Torre-Hernández is editor-in-chief of REC: Interventional Cardiology; the journal’s editorial procedure to ensure impartial handling of the manuscript. A. Morán-Aja, O. Martínez-Pérez, M. Cerezales, and J. Cuervo work for Axentiva Solutions S.L., a consultancy providing services to various pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Research Agency and Scientific Department of the Spanish Society of Cardiology for their support in project management and securing funding. Their collaboration was essential to the planning and execution of this study, enabling data analysis and evaluation of regional variability in TAVI implementation in Spain.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- TAVI has revolutionized the treatment of severe AS, becoming a first-line option in high- and intermediate-risk patients. It has demonstrated advantages over conventional surgery, including reduced mortality, a shorter length of stay, and improved quality of life. In Spain, TAVI use has grown unevenly across AC, influenced not only by economic factors but also by organizational and structural differences in patient selection criteria and resource availability. However, the impact of this variability on clinical outcomes and equity of access remains unclear.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- This study provides a comprehensive analysis of interregional variability in TAVI implementation in Spain, combining the Specialized Care Activity Minimum Basic Data Set with a specialist survey. Compared with former studies, it not only identifies differences in implementation rates across AC but also organizational, structural, and care-related barriers influencing access. Furthermore, it evaluates professional perceptions of team composition in clinical decision-making and challenges in continuity of care. These findings improve understanding of the determinants of heterogeneity in TAVI access and offer recommendations to enhance equity of implementation within the SNS. Results may be key for health policy planning and the design of strategies to optimize resource allocation and ensure more uniform access to this technology.

REFERENCES

1. Ferreira-González I, Pinar-Sopena J, Ribera A, et al. Prevalence of calcific aortic valve disease in the elderly and associated risk factors:a popula- tion-based study in a Mediterranean area.

2. Stewart BF, Siscovick D, Lind BK, et al. Clinical Factors Associated With Calcific Aortic Valve Disease.

3. Salinas P, Moreno R, Calvo L, et al. Long-term Follow-up After Transcath- eter Aortic Valve Implantation for Severe Aortic Stenosis.

4. Otto CM, Lind BK, Kitzman DW, Gersh BJ, Siscovick DS. Association of Aortic-Valve Sclerosis with Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity in the Elderly.

5. Íñiguez-Romo A, Zueco-Gil JJ, Álvarez-BartoloméM, et al. Outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve implantation in Spain through the Activity Registry of Specialized Health Care.

6. Ramaraj R, Sorrell VL. Degenerative aortic stenosis.

7. Van Hemelrijck M, Taramasso M, De Carlo C, et al. Recent advances in understanding and managing aortic stenosis.

8. Maldonado Y, Baisden J, Villablanca PA, Weiner MM, Ramakrishna H. General Anesthesia Versus Conscious Sedation for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement —An Analysis of Current Outcome Data.

9. Perrin N, Frei A, Noble S. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation:Update in 2018.

10. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implanta- tion for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery.

11. Duncan A, Ludman P, Banya W, et al. Long-Term Outcomes After Tran- scatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in High-Risk Patients With Severe Aortic Stenosis.

12. Vahanian A, Beyersdorf F, Praz F, et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease.

13. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients.

14. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replace- ment with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients.

15. Pinar E, de Lara JG, Hurtado J, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of the SAPIEN 3 transcatheter aortic valve implant in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis.

16. Tamm AR, Jobst ML, Geyer M, et al. Quality of life in patients with transcatheter aortic valve implantation:an analysis from the INTERVENT project.

17. Nuland PJA, van Ginkel DJ, Overduin DC, et al. The impact of stroke and bleeding on mortality and quality of life during the first year after TAVI:A POPular TAVI subanalysis.

18. Zhang S, Kolominsky-Rabas PL. How TAVI registries report clinical outcomes —A systematic review of endpoints based on VARC-2 definitions.

19. Gargiulo G, Sannino A, Capodanno D, et al. Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement.

20. Sehatzadeh S, Doble B, Xie F, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) for treatment of aortic valve stenosis:an evidence update.

21. la Torre Hernández JM, Lozano González M, García Camarero T, et al. Interregional variability in the use of cardiovascular technologies (2011- 2019). Correlation with economic indicators, admissions, and in-hospital mortality.

22. Biagioni C, Tirado-Conte G, Nombela-Franco L, et al. Situación actual del implante transcatéter de válvula aórtica en España.

23. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Actividad de Atención Especializada, Conjunto Mínimo Básico de Datos. Available at:https://www.sanidad. gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/cmbdhome.htm. Accessed 8 Apr 2024.

24. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Actividad de Atención Sanitaria Espe- cializada (RAE-CMBD). Actividad y resultados de la hospitalización en el SNS. Año 2022. Madrid:Ministerio de Sanidad;2024. Available at:https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/docs/RAE-CMBD_Informe_Hospitalizacion_2022.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2025.

25. Ministerio de Sanidad. Registro de Atención Sanitaria Especializada RAE-CMBD. Manual de Usuario y Glosario de Términos. Portal Estadístico;2023. Available at:https://pestadistico.inteligenciadegestion.sanidad.gob. es/publicoSNS/D/rae-cmbd/rae-cmbd/manual-de-usuario/manual-de-usuario- rae. Accessed 29 May 2025.

26. González Cebrián M, Valverde Bernal J, Bajo Arambarri E, et al. Docu- mento de consenso de la figura TAVI Nurse del Grupo de Trabajo de Hemodinámica de la Asociación Española de Enfermería en Cardiología.

27. Carnero-Alcázar M, Maroto-Castellanos LC, Hernández-Vaquero D, et al. Isolated aortic valve replacement in Spain:national trends in risks, valve types, and mortality from 1998 2017.

28. Baron SJ, Magnuson EA, Lu M, et al. Health Status After Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Low-Risk Patients With Aortic Stenosis.

29. Ministerio de Sanidad. Estrategia en Salud Cardiovascular del Sistema Nacional de Salud (ESCAV). 2022. Available at:https://www.sanidad.gob. es/areas/calidadAsistencial/estrategias/saludCardiovascular/docs/Estrategia_de_salud_cardiovascular_SNS.pdf. Accessed 29 May 2025.