Coronary artery perforation is one of the most feared complications of chronic total occlusion (CTO) percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), as it can lead to pericardial effusion, tamponade, hemodynamic deterioration, need for emergency pericardiocentesis or surgery, or death.1 The incidence of perforation is higher in CTO PCI compared with non-CTO PCI, likely due to higher anatomic complexity of CTOs and the use of advanced wiring techniques, such as antegrade dissection and re-entry and retrograde crossing.2

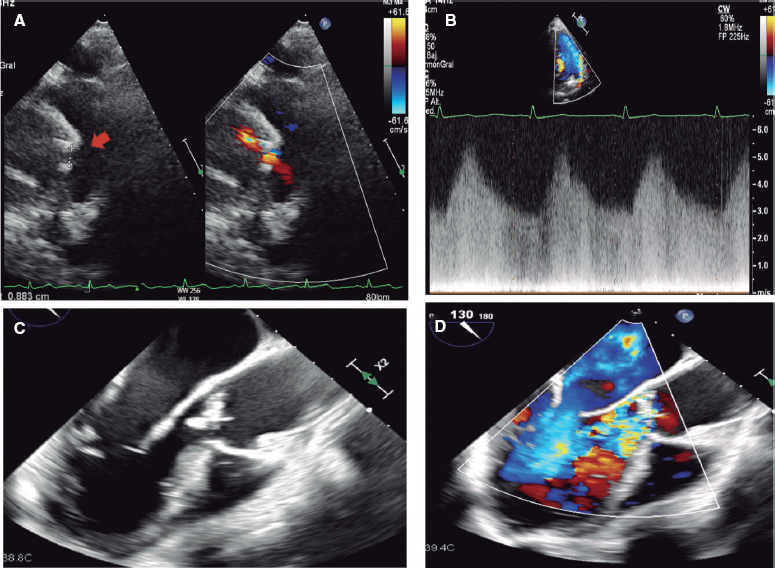

Coronary perforations have traditionally been classified according to severity using the Ellis classification.3 Because perforation location has important implications for management, another key classification of coronary perforations is according to location, as follows: a) large vessel perforation; b) distal vessel perforation; and c) collateral vessel perforation, in either a septal or an epicardial collateral.4

The first step in perforation management is immediate balloon inflation proximal to or at the site of perforation to prevent accumulation of blood in the pericardial space and tamponade. The balloon should be the same size as the perforated vessel and the inflation often last for several minutes unless the patient develops severe ischemic symptoms.5

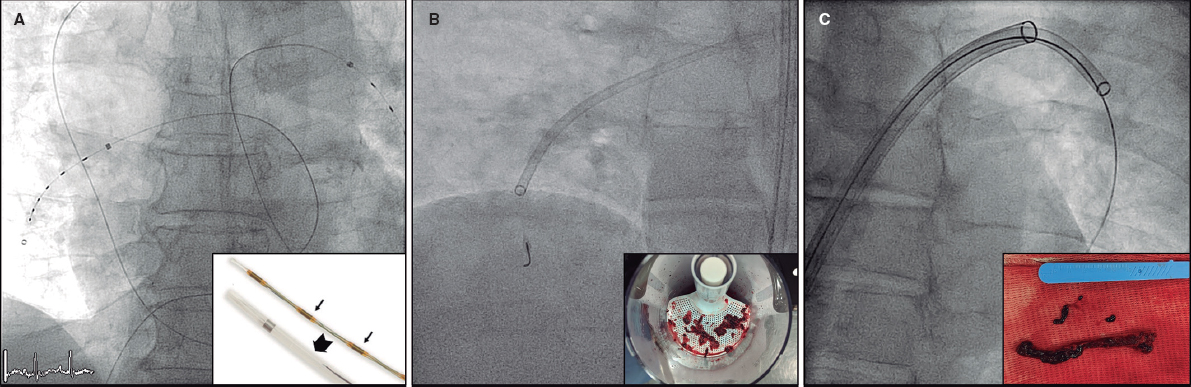

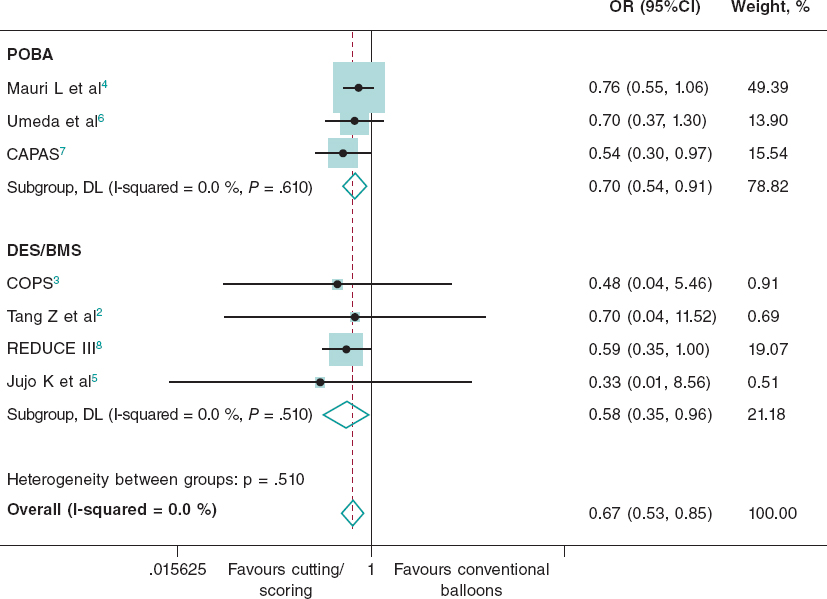

Large vessel perforations are usually treated with covered stents, such as the PK Papyrus (Biotronik, United States), and the Graftmaster Rx (Abbott Vascular, United States).6 Delivery of the covered stent can be achieved using either a single guide catheter (“block and deliver” technique)7 or 2 guide catheters (“ping pong”, also called “dueling guide catheter” technique)8. Both techniques are used to minimize bleeding into the pericardium while preparing for delivery and deployment of the covered stent. Covered stents require excellent guide catheter support for delivery and should be post-dilated aggressively after deployment to achieve good expansion. Large vessel perforations of CTO vessels can be sealed by coil deployment proximal to the perforation. Another option for treating large vessel perforations is through extraplaque crossing of the CTO segment (either antegrade or retrograde) followed by stenting: the tissue flap created can successfully seal the perforation.9,10

The most widely used treatment for distal vessel perforations is coil11 and autologous fat embolization12. Sometimes both fat and coil embolization are needed.12 Thrombin injection13 and embolization of microparticles, or other materials, such as gelfoam14 are also sometimes used.

In most cases embolization can be achieved through a single guide catheter using the “block and deliver” technique.7 The starting point for fat or coil delivery is advancing a microcatheter just proximal to the perforation site. Fat can be delivered through any microcatheter, but many coils are not compatible with the microcatheters typically used for PCI, such as the Corsair, Corsair XS, Caravel (Asahi Intecc, Japan), Turnpike, Turnpike LP, Mamba (Boston Scientific, United States) and Teleport (OrbusNeich, China) and instead require larger 0.035 inch lumen microcatheters (such as the Progreat, Terumo, Japan). Use of 0.014 inch coils (typically used for neurovascular applications, such as the Axium coils [Medtronic, United States) are compatible with all coronary microcatheters, facilitating use in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Based on the coil mechanism of release, coils are classified as pushable and detachable. Pushable coils are inserted into the microcatheter and pushed with a coil pusher until they exit the microcatheter. Pushable coil delivery is unpredictable and irreversible. In contrast, detachable coils can be delivered to the desired location and then retracted and repositioned until optimal positioning is achieved, followed by release using a dedicated release device that connects with the back end of the coil.

Septal collateral perforations are unlikely to have adverse consequences and usually no specific treatment is required. In contrast, perforation of epicardial collaterals branch can rapidly lead to tamponade and may be difficult to control. Embolization of epicardial perforations may need to be performed from both sides of the perforation.15

In cases of pericardial effusion and tamponade, emergency pericardiocentesis should be promptly performed.5 Although hemodynamic instability requires immediate pericardiocentesis, smaller size pericardial infusions can often be managed conservatively, as the accumulated blood increases the pressure in the pericardial space potentially preventing further bleeding.

Prevention is critical to decrease the incidence of perforation during CTO PCI. Key preventive strategies include: a) confirmation of guidewire position within the vessel architecture in multiple angiographic projections before balloon dilation and/or microcatheter advancement, usually through injection of the donor vessel to opacity the distal portion of the CTO vessel; b) use of intravascular imaging to determine the need for lesion preparation, and to guide balloon and stent size; c) outlining the anatomy of the collateral channels before and during crossing.5

Meticulous CTO PCI technique, continuous surveillance of the patient and availability and knowledge of how to treat coronary perforations can reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this complication during CTO PCI.

FUNDING

No funding.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

S. Kostantinis has no conflicts of interest to disclose. E.S. Brilakis declares consulting/speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (associate editor of Circulation), Amgen, Asahi Intecc, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), ControlRad, CSI, Elsevier, GE Healthcare, IMDS, InfraRedx, Medicure, Medtronic, Opsens, Siemens, and Teleflex; research support from Boston Scientific, GE Healthcare; owner, Hippocrates LLC; shareholder of MHI Ventures, Cleerly Health, Stallion Medical.

REFERENCES

1. Moroni F, Brilakis ES, Azzalini L. Chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention: managing perforation complications. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2021;19:71-87.

2. Karmpaliotis D, Karatasakis A, Alaswad K, et al. Outcomes With the Use of the Retrograde Approach for Coronary Chronic Total Occlusion Interventions in a Contemporary Multicenter US Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003434

3. Ellis SG, Ajluni S, Arnold AZ, et al. Increased coronary perforation in the new device era. Incidence, classification, management, and outcome. Circulation. 1994;90:2725-2730.

4. Ybarra LF, Rinfret S, Brilakis ES, et al. Definitions and Clinical Trial Design Principles for Coronary Artery Chronic Total Occlusion Therapies: CTO-ARC Consensus Recommendations. Circulation. 2021;143:479-500.

5. Brilakis ES. Manual of percutaneous coronary interventions: a step-by-step approach. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021.

6. Sandoval Y, Lobo AS, Brilakis ES. Covered stent implantation through a single 8-french guide catheter for the management of a distal coronary perforation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;90:584-588.

7. Tarar MN, Christakopoulos GE, Brilakis ES. Successful management of a distal vessel perforation through a single 8-French guide catheter: Combining balloon inflation for bleeding control with coil embolization. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;86:412-416.

8. Ben-Gal Y, Weisz G, Collins MB, et al. Dual catheter technique for the treatment of severe coronary artery perforations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2010;75:708-712.

9. Xenogiannis I, Tajti P, Nicholas Burke M, Brilakis ES. An alternative treatment strategy for large vessel coronary perforations. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;93:635-638.

10. Kartas A, Karagiannidis E, Sofidis G, Stalikas N, Barmpas A, Sianos G. Retrograde Access to Seal a Large Coronary Vessel Balloon Perforation Without Covered Stent Implantation. JACC Case Rep. 2021;3:542-545.

11. Kostantinis S, Brilakis ES. When and how to close vessels in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;98:1332-1334.

12. Guddeti RR, Kostantinis ST, Karacsonyi J, Brilakis ES. Distal coronary perforation sealing with combined coil and fat embolization. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;40:222-224.

13. Kotsia AP, Brilakis ES, Karmpaliotis D. Thrombin injection for sealing epicardial collateral perforation during chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary interventions. J Invasive Cardiol. 2014;26:E124-E126.

14. Dixon SR, Webster MW, Ormiston JA, Wattie WJ, Hammett CJ. Gelfoam embolization of a distal coronary artery guidewire perforation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;49:214-217.

15. Boukhris M, Tomasello SD, Azzarelli S, Elhadj ZI, Marza F, Galassi AR. Coronary perforation with tamponade successfully managed by retrograde and antegrade coil embolization. J Saudi Heart Assoc. 2015;27:216-221.