Available online: 26/04/2019

Valvulopathy

REC Interv Cardiol. 2019;1:34-40

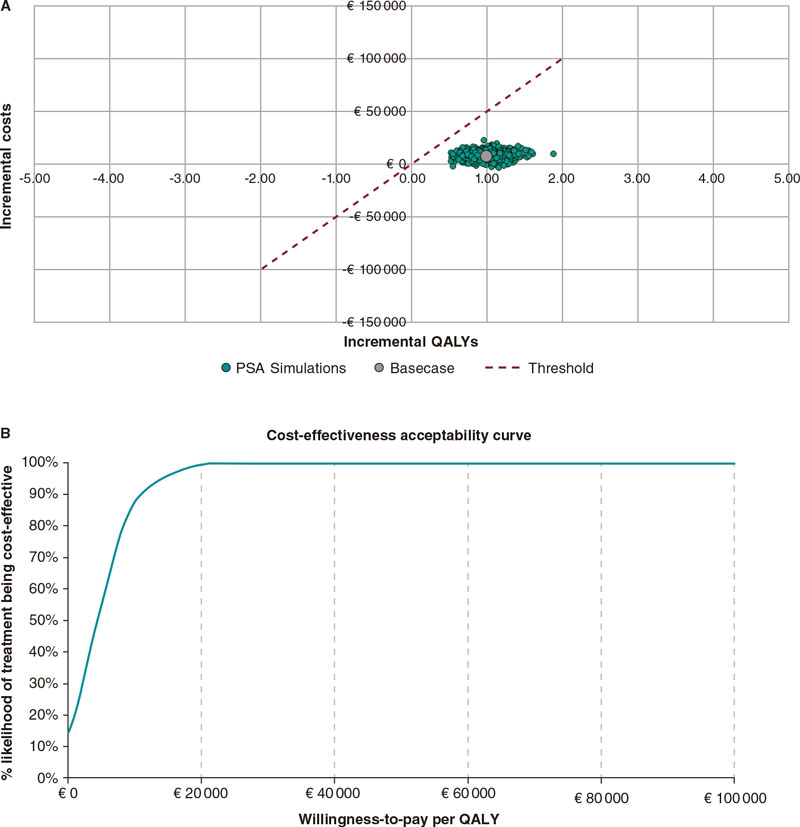

Changes in mitral annular morphology following transcatheter mitral valve repair. Clinical repercussion and importance of etiology

Cambios morfológicos anulares tras reparación mitral transcatéter: repercusión clínica y relevancia de la etiología

Área del Corazón, Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Asturias, España

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as an alternative and less invasive treatment to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR). Left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LV-GLS) can reveal changes in left ventricular performance before involvement of ejection fraction. Our aim was to present and evaluate our center’s experience regarding short- and long-term reverse left ventricular remodeling using two-dimensional-speckle tracking echocardiography-derived LV-GLS after TAVI compared with SAVR.

Methods: Our multidisciplinary cardiac team carefully evaluated 65 patients for SAVR who presented with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis and who had high, intermediate, or low surgical risk. The patients underwent either TAVI with an Evolut-R self-expanding valve or SAVR. Echocardiographic evaluation was performed before, 1 month, and 1 year after the procedure.

Results: TAVI was performed in 31 patients and SAVR in 34 patients. The incidence of valvular and paravalvular leak was higher in the TAVI group despite early favorable LV remodeling with a significant decrease in left ventricular mass index and E/e’ shortly after the procedure and an early detectable improvement in LV-GLS from −8.18 ± 1.81 to −14.52 ± 2.52, reaching −16.12 ± 2.69 at 1 year (P < .001). This early improvement was not observed in the SAVR group. TAVI preserved right ventricular function without affecting tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion or increasing estimated pulmonary artery pressure.

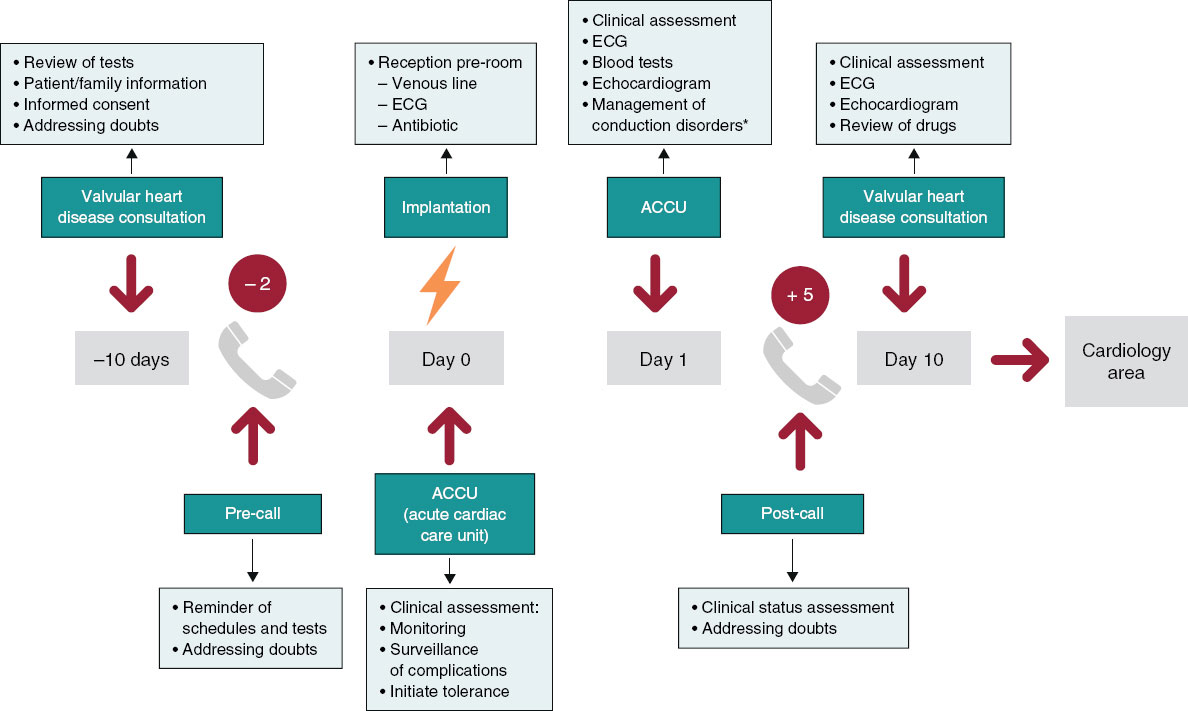

Conclusions: Patients who underwent TAVI had earlier and significantly better LV remodeling with early reduction in left ventricular mass index, E/e’ ratio, and significant early improvement in LV-GLS without concomitant impairment of left ventricular ejection fraction percentage or deterioration of right ventricular function.

Keywords: Left ventricular remodeling. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Surgical aortic valve replacement. Two-dimensional speckle tracking. TAVI. SAVR.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: El implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI) se ha establecido como una alternativa menos invasiva al recambio valvular aórtico (RVAo). El strain longitudinal global del ventrículo izquierdo (SLG-VI) puede detectar cambios en el funcionamiento ventricular izquierdo antes de que se deteriore la fracción de eyección. Nuestro objetivo fue presentar y evaluar la experiencia de nuestro centro en cuanto al remodelado inverso ventricular izquierdo a corto y largo plazo, utilizando el SLG-VI mediante rastreo de marcas, o speckle tracking, bidimensional, después de TAVI en comparación con los resultados tras RVAo.

Métodos: El equipo cardiológico multidisciplinario evaluó 65 pacientes remitidos para RVAo por estenosis aórtica grave, con riesgo quirúrgico alto, intermedio o bajo. Los pacientes se clasificaron según fueran tratados con TAVI (prótesis autoexpandible Evolut-R) o RVAo. Se realizó ecocardiograma antes del procedimiento, al mes y al año de llevarlo a cabo.

Resultados: 31 pacientes se trataron con TAVI y 34 con RVAo. En el grupo de TAVI hubo mayores tasas de regurgitación valvular y paravalvular. Se observó un remodelado ventricular izquierdo más favorable, con una disminución significativa del índice de masa del ventrículo izquierdo, un índice E/e’ tras el procedimiento y una mejoría precoz del SLG-VI de −8,18 ± 1,81 a −14,52 ± 2,52, que al año fue −16,12 ± 2,69 (p < 0,0001), sin que esta mejoría precoz en dicho parámetro se evidenciara en el grupo de RVAo. En el grupo de TAVI se mantuvo la función ventricular derecha sin afectar al desplazamiento sistólico del plano tricúspide y sin aumentar la presión sistólica de la arteria pulmonar estimada.

Conclusiones: Los pacientes que recibieron un TAVI tuvieron un mayor y más precoz remodelado ventricular izquierdo, con una reducción precoz del índice de masa del ventrículo izquierdo y del índice E/e’, y una mejoría significativa precoz del SLG-VI, sin alteración de la fracción de eyección del ventrículo izquierdo ni deterioro de la función ventricular derecha.

Palabras clave: Remodelado ventricular izquierdo. Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica. Recambio valvular aórtico. Speckle tracking bidimensional. TAVI. RVAo.

Abbreviations

AS: aortic stenosis. LV: left ventricular. LVEF: left ventricular ejection fraction. LV-GLS: left ventricular global longitudinal strain. SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

INTRODUCTION

Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valvular heart disease worldwide. For severe symptomatic cases, surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has been the gold standard procedure for decades.1

However, since its introduction in 2002, transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has emerged as a less invasive alternative treatment with a shorter recovery time and lower perioperative mortality rate. Initially, the procedure was introduced for patients with high2,3 and intermediate surgical risk.4,5 However, advances in technique and operator skills have expanded its use to patients with low surgical risk.6,7

It is well-known that the main problem in people with isolated AS is an increase in afterload, resulting in diastolic dysfunction followed by systolic dysfunction of the left ventricle (LV).8 The optimal timing of intervention, whether surgical or transcatheter, depends on the severity or grades of stenosis, symptoms, and LV dysfunction.9 Aortic valve replacement, whether through TAVI or SAVR, significantly affects LV remodeling, reduces symptoms, and increases overall survival.7

The current guidelines use left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) percentage to assess LV systolic function. However, subclinical myocardial dysfunction may develop despite a normal LVEF percentage. Fibrotic changes induced by AS mainly affect LV longitudinal function, while ejection fraction is determined by radial myocardial function. Most cases of severe AS requiring intervention have preserved ejection fraction percentages before and after intervention, with reduced ejection fraction percentages only observed in late and neglected cases with poor prognoses when both radial and longitudinal functions are affected.8 Therefore, assessment of LV function or remodeling before or after the intervention should not be based solely on LVEF. Another reliable method is needed to fully assess the impact of aortic valve replacement on LV function.10

Global longitudinal strain (GLS) analysis has proven useful in accurately characterizing regional and global myocardial systolic function. This analysis can detect changes in LV performance and overcome the limitations of ejection fraction, such as considerable interobserver variability, lack of subtle regional differences, and inadequate acoustic windows, with superior prognostic validity compared with LVEF percentage.10

At Tanta University Hospital, we recently introduced the TAVI procedure. The aim of this study was to present and evaluate the experience of our team and study the impact of aortic valve replacement on several factors. These included prosthesis hemodynamics, significant valvular or paravalvular leak, and the need for new pacemaker implantation. We also aimed to assess short-and long-term reverse LV remodeling by evaluating conventional echocardiographic parameters. In addition, we used the more reliable and accurate two-dimensional (2D) speckle tracking-derived left ventricle global longitudinal strain (LV-GLS) following the TAVI procedure and compared these parameters with the gold standard SAVR.

Patients and study design

Patient sample and inclusion criteria

This longitudinal, prospective, nonrandomized, single-center study was conducted in the Cardiology Department of the Faculty of Medicine at Tanta University Hospital between May 2022 and October 2023. Sixty-five patients diagnosed with severe symptomatic AS, categorized as high, intermediate, or low surgical risk and scheduled for aortic valve replacement, underwent thorough evaluation by the multidisciplinary heart team. Following selection of the appropriate procedure, eligible patients were allocated to undergo either trans-femoral TAVI with an Evolut-R self-expandable valve (Medtronic, United States) or SAVR.

Patients were classified into 2 groups as follows:

-

– Group I: patients with clinical symptoms, such as chest pain, syncope, or dyspnea, as well as echocardiographic evidence of severe AS (defined as a valvular area ≤ 1 cm2 or indexed valve area ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2, mean pressure gradient ≥ 40 mmHg, and transaortic peak velocity ≥ 4 m/s).9 Patients meeting these criteria were considered suitable candidates for TAVI.

-

– Group II: patients diagnosed with symptomatic severe AS based on clinical and echocardiographic findings, who were were deemed suitable candidates for SAVR.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded patients if they had any of the following conditions: concomitant significant valvular heart disease other than AS, severe renal impairment (glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/min/ 1.73 m2), prior biological or bare-metal valve replacement, significant carotid or coronary artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, unstable heart failure, atrial fibrillation, atrial flutter, or any significant rhythm disturbance, predominant aortic regurgitation, infective endocarditis, or severe LV dysfunction (ejection fraction < 35%). We also excluded patients who died during the study period or who lacked echocardiographic data before or after valve replacement.

METHODS

All patients underwent a full history and clinical evaluation. Data on the length of hospital stay, complications in the perioperative period, and clinical follow-up were collected by a review of medical records.

TAVI procedure

After the selection of suitable patients and valves, the procedure consisted of 5 sequential steps: access, valve crossing, balloon aortic valvuloplasty, valve implantation, and access closure. Additional considerations included the choice of anesthesia (local with sedation vs general anesthesia) and the placement of a temporary pacing wire in the right ventricle. Most patients underwent the procedure under conscious sedation. The devices used were the Evolut-R self-expandable valves (26, 29, or 34 mm).11

Standard echocardiography examination

Echocardiographic measurements were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging.12 Using the Vivid E9 ultrasound system (GE Vingmed Ultrasound, Norway), equipped with an M5S phased array transducer (2.5–5.0 MHz) and a dedicated software package, images and data were digitally stored for offline analysis before the procedure, shortly after (1 month), and 9 to 12 months after replacement. All echocardiographic parameters were acquired by 2 trained observers. Three to 5 consecutive beats were recorded and averaged.

LV dimensions, wall thickness, ejection fraction percentage and LV mass index were obtained. The transaortic peak and mean pressure gradients were calculated from the aortic velocity obtained through multiwindow continuous-wave Doppler evaluation using the modified Bernoulli equation.

The effective orifice area of the aortic valve was determined using the continuity equation and was indexed to body surface area as the stroke volume measured in the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) divided by the aortic time velocity integral measured by continuous-wave Doppler. LVOT stroke volume was calculated as the LVOT cross-sectional area multiplied by the LVOT time velocity integral, measured by pulsed-wave Doppler.

After aortic valve replacement, the LVOT velocity and diameter were obtained just apical to the prosthetic valve stent or sewing ring. The presence and quantification of any valvular or paravalvular leak were assessed using color and continuous-wave Doppler.

Additional echocardiographic parameters were obtained to assess LV diastolic function, particularly transmitral flow. This included measuring peak early (E) and atrial (A) flow velocities, as well as calculating the E/A ratio. The mean peak early diastolic (e’) velocity was acquired from the septal side of the mitral annulus in the apical 4-chamber view using tissue Doppler settings. The E/e’ ratio was then calculated, serving as an indicator of LV filling pressures.

Conventional parameters were used to assess right-sided function. This included measuring the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion and evaluating the peak tricuspid regurgitation velocity with color Doppler flow imaging. The estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure was calculated using the formula: estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure = right atrial pressure + 4 V2, where V represents tricuspid regurgitant velocity).

2D speckle tracking echocardiography, left ventricular global longitudinal strain

Global longitudinal peak systolic strain was assessed offline. Endocardial borders were manually traced and were visualized as a color-coded sequence in individual clips. Subsequently, they were combined in a bull’s-eye plot. The software then calculated the regional and the average strain of the apical 2-chamber, 4-chamber, and 3-chamber views of the 17 segments at an end-systolic frame. Images with a frame rate < 50 were excluded.13 The average peak GLS was then recorded and documented for each study.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS Statistics) for Windows, version 26 (IBM Corp., United States). Qualitative variables (eg, sex) are presented as frequencies, and the association of groups with categorical variables was assessed using the Pearson chi-square test for independence, the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test, or the Fisher exact test, as appropriate. Quantitative variables (eg, age and all echocardiographic measurements) are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Differences in quantitative variables between the groups were assessed using either the independent samples T-test for baseline characteristics and measurements or mixed linear model analysis with treatment groups as a factor and baseline values as a covariate. Comparisons of repeated measurements within each group performed with the mixed linear model analysis for repeated measures with the time of treatment as a factor. The degree of mitral regurgitation between time points was compared using the McNemar test, while the degree of paravalvular leak was evaluated between time points using the marginal homogeneity test. A significance level of P < .05 was chosen for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic data for the 2 groups: TAVI was performed in 31 patients and SAVR in 34. Age was older in the TAVI group (P < .001) than in the SAVR group.

Table 1. Demographic data, comorbidities and percentage of different complications in the 2 procedures

| TAVI (31) | SAVR (34) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean ± SD | 68.86 ± 2.61 | 66.00 ± 1.74 | < .001* |

| Sex | Female | 7 (22.6%) | 9 (26.5%) | .716 |

| Male | 24 (77.4%) | 25 (73.5%) | ||

| BMI | Mean ± SD | 32.71 ± 3.13 | 32.83 ± 2.76 | .893 |

| Comorbidities | Hypertension | 15 (48.4%) | 18 (52.9%) | .714 |

| Diabetes | 11 (35.5%) | 13 (38.2%) | .818 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 13 (41.9%) | 13 (38.2%) | .761 | |

| CVD | 7 (22.6%) | 12 (35.3%) | .260 | |

| Complications Clinical outcome | No | 22 (71.0%) | 30 (88.2%) | .082 |

| Conduction disturbance | 4 (12.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | .046* | |

| Acute kidney injury | 3 (6.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | .103 | |

| Neurological | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.9%) | .493 | |

| Vascular-related complications | 5 (16.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | .021* | |

| Rehospitalization | 1 (3.2%) | 2 (5.9%) | .999 | |

|

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; PPM, permanent pacemaker; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; SD, standard deviation; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation. * Significant at P < .05. |

||||

The perioperative and postoperative course were uneventful in most patients, with reduced symptoms in both groups. However, several complications occurred during the periprocedural period and 1-year follow-up: 4 patients developed conduction abnormalities, presenting as complete heart block during their hospital stay and requiring the insertion of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker; 3 patients developed contrast-induced nephropathy, which was corrected before discharge (2 of them had long-standing diabetes); 5 patients developed vascular complications in the form of mild to moderate bleeding from the access site, which did not require transfusion or intervention; and only 1 patient was readmitted due to hypertensive pulmonary edema (the patient had chronic uncontrolled hypertension) in the TAVI group. One patient died 10 days post-TAVI and was excluded.

In the SAVR group, 2 patients developed ischemic stroke due to ineffective anticoagulation and 2 others were readmitted due to warfarin toxicity complicated by gastrointestinal bleeding requiring admission for blood transfusion until the bleeding was controlled. None of the patients in this group developed acute renal injury, conduction abnormalities, or periprocedural vascular complications during their hospital stay (table 1).

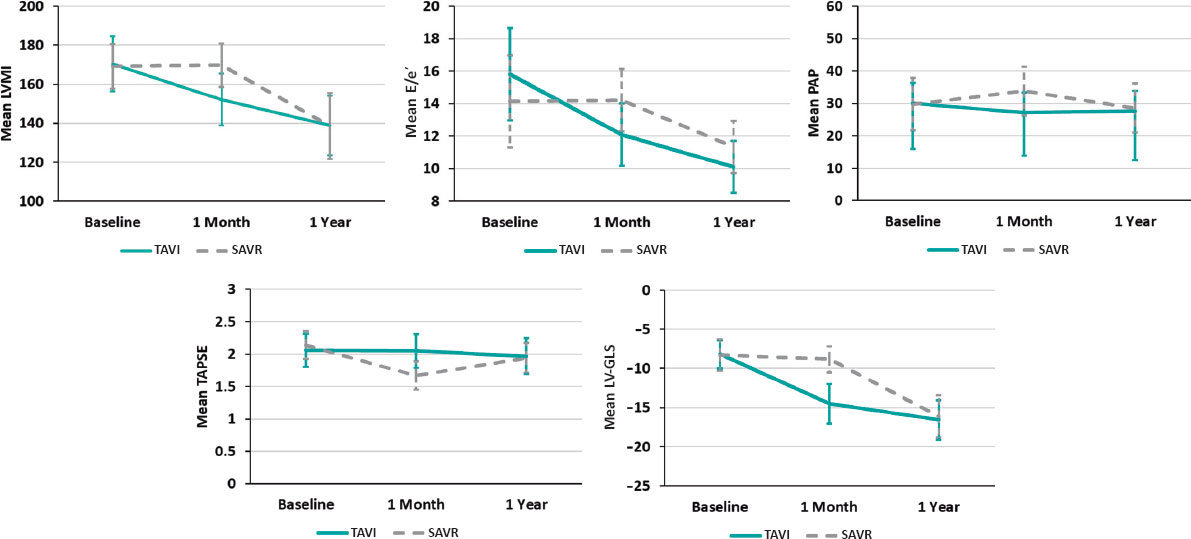

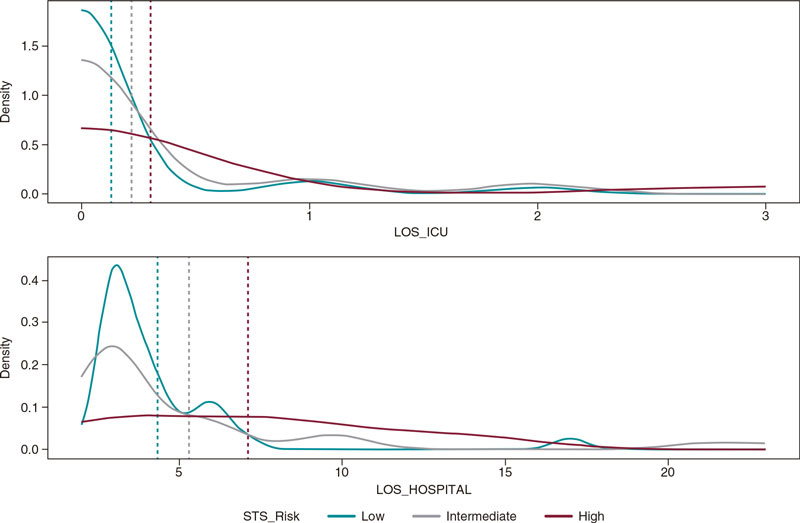

In both groups, all echocardiographic variables were collected at baseline (before the procedure), and at 1 month, and 1 year postprocedure. These data are shown in table 2. A comparison of relative changes in each parameter at different evaluation times in the 2 groups is shown in table 3 and graphically represented in figure 1.

Table 2. Echo-Doppler parameters for the 2 procedures at each stage of assessment

| Variables | Baseline | 1 month | 1 year | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAVI | SAVR | P | TAVI | SAVR | P | TAVI | SAVR | P | ||

| LVEDD (cm) | 5.09 ± 0.32 | 5.15 ± 0.43 | .632 | 5.01 ± 0.33 | 5.13 ± 0.41 | .133 | 4.99 ± 0.29 | 4.95 ± 0.29 | .380 | |

| LVESD (cm) | 3.30 ± 0.28 | 3.51 ± 0.46 | .069 | 3.23 ± 0.28 | 3.50 ± 0.47 | .136 | 3.20 ± 0.22 | 3.27 ± 0.21 | .941 | |

| LVMI (g/m2) | 170.33 ± 14.10 | 169.17 ± 11.39 | .760 | 152.14 ± 13.28 | 169.63 ± 11.05 | < .001* | 138.81 ± 15.16 | 138.54 ± 17.03 | .952 | |

| LV sept (cm) | 1.53 ± 0.12 | 1.52 ± 0.10 | .707 | 1.44 ± 0.14 | 1.46 ± 0.13 | .107 | 1.21 ± 0.17 | 1.25 ± 0.13 | .280 | |

| LVEF % | 63.33 ± 5.86 | 57.44 ± 13.66 | .074 | 63.67 ± 6.05 | 59.71 ± 6.89 | .207 | 64.48 ± 5.12 | 62.54 ± 4.29 | .524 | |

| ESPAP (mmHg) | 30.00 ± 6.32 | 29.79 ± 8.06 | .924 | 27.14 ± 6.08 | 33.79 ± 7.49 | < .001* | 27.62 ± 6.21 | 28.54 ± 7.59 | .491 | |

| E/A | 0.63 ± 0.37 | 0.60 ± 0.39 | .801 | 0.65 ± 0.43 | 0.62 ± 0.39 | .899 | 0.67 ± 0.43 | 0.62 ± 0.38 | .504 | |

| E/e’ | 15.81 ± 2.84 | 14.13 ± 3.05 | .063 | 12.10 ± 1.92 | 14.21 ± 2.67 | < .001* | 10.10 ± 1.61 | 11.33 ± 1.90 | .007* | |

| TAPSE (cm) | 2.06 ± 0.26 | 2.14 ± 0.22 | .239 | 2.05 ± 0.26 | 1.67 ± 0.22 | < .001* | 1.97 ± 0.28 | 1.94 ± 0.23 | .199 | |

| AV-Vmax (m/s) | 4.92 ± 0.22 | 4.95 ± 0.24 | .655 | 1.64 ± 0.16 | 1.91 ± 0.15 | < .001* | 1.68 ± 0.16 | 1.85 ± 0.09 | < .001* | |

| AV-MG (mmHg) | 58.38 ± 7.17 | 58.08 ± 7.67 | .894 | 9.85 ± 1.65 | 13.23 ± 1.95 | < .001* | 9.21 ± 1.21 | 12.85 ± 1.93 | < .001* | |

| AVA-I (cm2/m2) | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | .984 | 1.20 ± 0.11 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | .358 | 1.22 ± 0.10 | 1.26 ± 0.08 | .201 | |

| LV-GLS % | −8.18 ± 1.81 | −8.30 ± 1.99 | .829 | −14.52 ± 2.52 | −8.82 ± 1.68 | < .001* | −16.57 ± 2.52 | −16.12 ± 2.69 | .511 | |

| MR degree | Mild | 26 (83.9%) | 21 (61.8%) | .057 | 28 (90.3%) | 23 (67.6%) | .028* | 27 (87.1%) | 21 (61.8%) | .020* |

| ≥ Moderate | 5 (16.1%) | 13 (38.3%) | 3 (9.7%) | 11 (32.4%) | 4 (12.9%) | 13 (38.2%) | ||||

| Degree of V or PV leak | None | − | − | 17 (54.8%) | 28 (82.4%) | .011* | 15 (48.4%) | 25 (73.5%) | .042* | |

| Mild | − | − | 12 (38.7%) | 6 (17.6%) | 13 (41.9%) | 8 (23.5%) | ||||

| ≥ Moderate | − | − | 2 (6.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (9.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | ||||

|

AVA-I, indexed aortic valve area; AV-MG, aortic valve mean pressure gradient; AV-Vmax, aortic valve maximum velocity; E/A, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity/ late atrial diastolic mitral flow velocity; E/e’, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity/ pulsed-wave tissue Doppler-derived early diastolic velocity from the septal mitral annulus ratio; ESPAP, estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LV-GLS, Left ventricular- global longitudinal strain; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LV sept, left ventricular septal thickness; MR, mitral regurgitation; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; V or PV leak, valvular or paravalvular leak. * Significant at P < .05. Values are expressed as mean + standard deviation. |

||||||||||

Table 3. Comparison of repeated measurements at 1 month and 1year postintervention vs baseline measurements

| TAVI | SAVR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month vs baseline P | 1 year vs baseline P | 1 month vs baseline P | 1 year vs baseline P | |

| LVED | .092 | .202 | .999 | .024* |

| LVESDD | .157 | .064 | .999 | .008* |

| LVMI | < .001* | < .001* | .999 | < .001* |

| LV sept | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* |

| LVEF percentage | .999 | .430 | .736 | .110 |

| ESPAP | .001* | .036* | .005* | .752 |

| E/A | .768 | .117 | .406 | .761 |

| E/e’ | < .001* | < .001* | .999 | < .001* |

| TAPSE | .999 | .076 | < .001* | .002* |

| AV-VMAX | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* |

| AV-MG | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* |

| AVA-I | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* | < .001* |

| LV-GLS | < .001* | < .001* | .443 | < .001* |

| MR degree | .500 | 1.000 | .500 | 1.000 |

| - | - | 1 year vs 1 month P | - | 1 year vs 1 month P |

| Degree of V or PV leak | - | .083 | - | .046* |

|

AVA-I, indexed aortic valve area; AV-MG, aortic valve mean pressure gradient; AV-Vmax, aortic valve maximum velocity; E/A, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity/late atrial diastolic mitral flow velocity; E/e’, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity/pulsed-wave tissue Doppler-derived early diastolic velocity from the septal mitral annulus ratio; ESPAP, estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure; LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD, left ventricular end-systolic dimension; LV-GLS, left ventricular- global longitudinal strain; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; LV sept, left ventricular septal thickness; MR, mitral regurgitation; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation; V or PV leak, valvular or paravalvular leak. P from mixed linear model analysis for repeated measures using time of treatment as a factor. * Significant at P < .05. |

||||

Figure 1. Relative changes of each parameter throughout the study from baseline to 1 year in both groups, with a relative decrease of LVMI, E/e, estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure and relative increase in LV-GLS with no change in TAPSE shortly (1 month) after TAVI procedure vs no detectable changes in LVMI, E/e or LV-GLS and relative decrease in TAPSE and increase in estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure in the SAVR group. At 1 year, the parameters were nearly equivalent in the 2 groups. E/e’, peak early diastolic mitral flow velocity/ pulsed-wave tissue Doppler-derived early diastolic velocity from the septal mitral annulus ratio; LV-GLS, left ventricular-global longitudinal strain; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; PAP, pulmonary artery pressure; SAVR, surgical aortic valve replacement; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TAVI, transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

All baseline echocardiographic variables were comparable between the 2 groups.

Valve hemodynamics

After both procedures, there was a significant improvement in aortic valve maximum velocity (AV-Vmax), aortic valve mean pressure gradient (AV-MG), and aortic valve area (AVA) (P < .001 for all). This improvement persisted throughout the year, while a relatively more pronounced early and 1-year improvement in AV-Vmax and AV-MG (P < .001 for both) were observed in the TAVI vs the SAVR group. None of the patients in either group developed patient prosthetic mismatch.

Left ventricle dimensions and functions

There was a steady and significant improvement in LV septal thickness postprocedure in both groups at different evaluation times. There was also a slight but significant improvement in LV dimensions (LV end-diastolic dimension and LV end-systolic dimension) in the SAVR group at 1 year compared with the TAVI group. Specifically, LV end-diastolic dimension decreased from 5.15 ± 0.43 to 4.95 ± 0.29 (P = .024) in the SAVR group vs 5.09 ± 0.32 to 4.99 ± 0.29 (P = .202) in the TAVI group. Similarly, LV end-systolic dimension decreased from 3.51 ± 0.46 to 3.27 ± 0.21 (P = .008) in the SAVR group vs 3.30 ± 0.28 to 3.20 ± 0.22, P = .064 in the TAVI group.

A favorable early outcome was observed in the TAVI group, with a significant decrease in LV mass index and E/e’ shortly after the procedure that persisted at 1 year. LV mass index decreased from 170.33 ± 14.10 to 152.14 ± 13.28 (P < .001) in the TAVI group vs 169.17 ± 11.39 to 169.63 ± 11.05 (P = .999) in the SAVR group. E/e’ decreased from 15.81 ± 2.84 to 12.10 ± 1.92 (P < .001) in the TAVI group vs 14.13 ± 3.05 to 14.21 ± 2.67 (P = .999) in the SAVR group (figure 1).

Although mitral valve regurgitation showed a relative improvement in the TAVI group compared with the SAVR group at 1 month (P = .028) and 1 year of follow-up (P = .020), it did not significantly change within each group at different evaluation times. Mild mitral regurgitation was prevalent in both groups.

Right ventricular assessment

There was no significant change in tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion postprocedure in the TAVI group. However, in the SAVR group it significantly decreased shortly after the procedure from 2.14 ± 0.22 to 1.67 ± 0.22 (P < .001). As shown in figure 1, estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure showed a significant reduction from 30.00 ± 6.32 to 27.14 ± 6.08 (P = .001) shortly after TAVI but was significantly increased from 29.79 ± 8.06 to 33.79 ± 7.49 after SAVR (P = .005).

Left ventricular global longitudinal strain

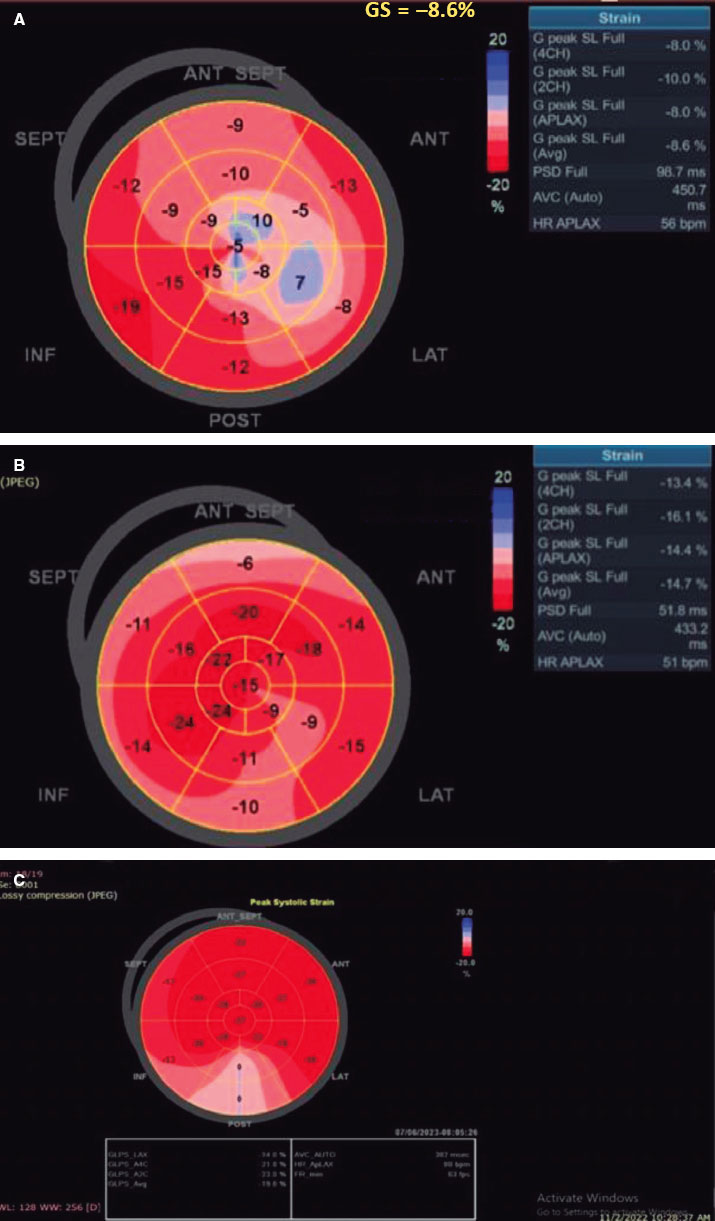

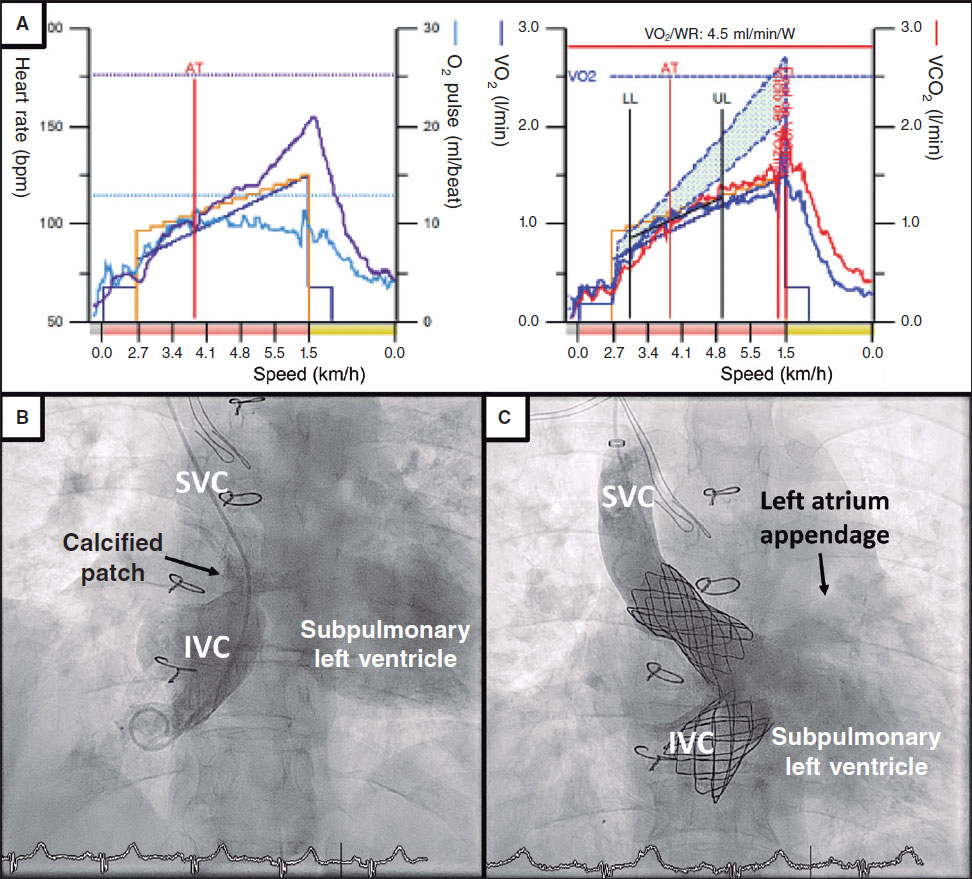

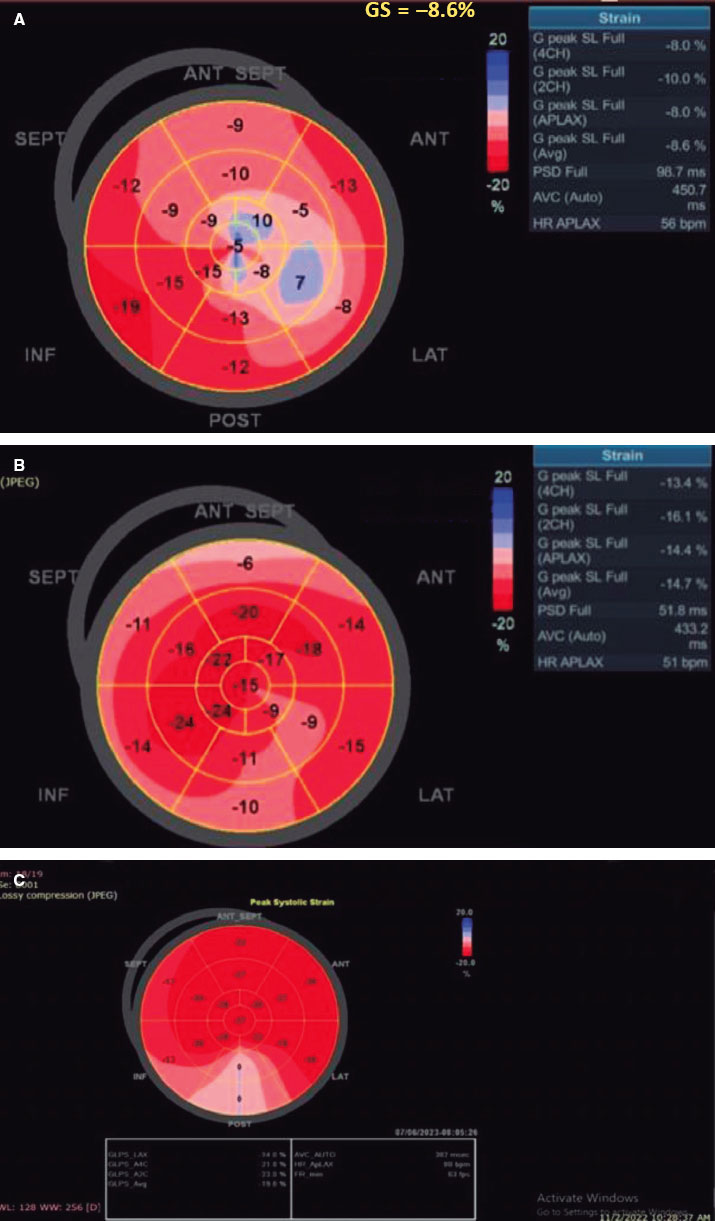

There was a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (P < .001), favoring the TAVI group with an early detectable improvement of LV-GLS from −8.18 ± 1.81 to −14.52 ± 2.52, P < .001 at 1 month, reaching −16.57 ± 2.52 at 1 year. In contrast, this early improvement was not observed in the SAVR group, with the first detectable improvement being observed at 1 year (−8.30 ± 1.99 to −16.12 ± 2.69; P < .001) (figure 2).

Figure 2. A, baseline: low LV-GLS before TAVI. B, 1 month after the procedure, LV-GLS significantly increased from −8.6 to −14.7. C, 1 year after TAVI, LV-GLS continued to improve from −14.7 to −19.8. SEPT, septal; ANT, anterior; ANT SEPT, anteroseptal; INF, inferior; POST, posterior; LAT, lateral.

Valvular or paravalvular leak

In the TAVI group, more patients developed mild or ≥ moderate paravalvular leak, with 12 (38.7%) and 2 (6.5%) patients, respectively, at immediate follow-up. These numbers increased to 13 (41.9%) and 3 (9.7%) patients, respectively, at 1 year. In the SAVR group, none developed ≥ moderate paravalvular leak, and only 6 (17.6%) patients had mild nonsignificant paravalvular leak at 1 month. Only 1 patient progressed from mild to moderate paravalvular leak at 1 year, with a statistically significant difference between the 2 groups (P = .011 at 1 month and P = .042 at 1 year).

Interobserver and intraobserver variability

The correlation coefficient for interobserver reproducibility of LV-GLS was 0.933 (95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 0.894-0.957), and that for intraobserver agreement was approximately 0.985 (95%CI, 0.976-0.991).

DISCUSSION

Echocardiography is the most effective approach for evaluating prosthetic valve performance, prosthesis-related complications, chamber geometry, remodeling, and cardiac function after any valve intervention, whether surgical or transcatheter.

Our study included all surgical risk categories. Whenever possible, TAVI was the preferred strategy for aortic valve replacement to increase our center’s experience, unless contraindicated after heart team discussion (eg, inadequate annulus size, LV thrombus, asymmetric valve calcification, short distance between annulus and coronary ostium, inadequate vascular access, mobile thrombi in the arch or ascending aorta, bicuspid valve, concomitant significant valvular or coronary artery diseases requiring intervention, or due to unlikely improvement in quality of life after TAVI because of associated comorbidities). TAVI was found to be noninferior to SAVR regarding postoperative improvement in symptoms and enhanced valve hemodynamics with improvement of AV-Vmax, AV-mean pressure gradient, and indexed aortic valve area, and even greater improvement in AV-Vmax and AV-mean pressure gradient during short- and long-term follow-up. These findings are supported by the recent update of the guidelines on indications for TAVI,14 which have firmly established this approach as an alternative to SAVR in the treatment of AS in all surgical risk categories after the continued evolution of TAVI and the results of multiple randomized trials.

The major pathophysiological features of AS are increased afterload, LV remodeling, increased filling pressure, LV diastolic dysfunction, and heart failure symptoms. The diastolic dysfunction occurs earlier and is followed by an increase in LV mass.15 After TAVI, there are immediate marked reductions in transvalvular pressure gradients, which translate into an immediate decrease in LV afterload, with an increase in E and e’ that reflects early diastolic relaxation after TAVI compared with SAVR.

After SAVR, transient perioperative LV dysfunction related to cardiopulmonary bypass is a well-known factor that can adversely affect LV remodeling.16 This transient LV dysfunction is associated with elevated biochemical markers, such as brain natriuretic peptides and troponin I soon after SAVR.17,18 However, these consequences of cardiopulmonary bypass are absent after TAVI. Therefore, LV remodeling can be reduced shortly after the procedure due to less neurohormonal stimulation, which helps to improve preprocedure LV hypertrophy.16

Even with preserved systolic LV function after postcardiac surgery, the degree of the E/e’ ratio has been shown to strongly correlate with brain natriuretic peptide levels. Consequently elevated left atrial pressure and diastolic dysfunction are major determinants of the release of brain natriuretic peptides in clinical settings.19 The present study therefore highlights how the early recovery of LV filling pressure, as indicated by earlier reduction in AV-Vmax, AV-MG, E/e’ ratio, and LV mass index can positively affect LV remodeling. This translates into early improvement of LV-GLS deformation parameters even without significant changes in LVEF percentage after TAVI. These phenomena can help explain the evidence of better short-term prognosis in patients with severe AS undergoing TAVI.20 At the 1-year follow-up, the initial mechanisms responsible for such better early outcomes were absent, and consequently the distribution of alterations in diastolic function in the SAVR group was comparable to that in the TAVI group.15

Mitral valve regurgitation did not appear to be significantly affected within the same group at different evaluation times but was improved in the TAVI group compared with the SAVR group.

These results contrast with previously published data from Gonçalves et al.21 Although these authors calculated parameters of LV diastolic function before and minutes after TAVI, they did not include a comparison with a surgical group. They found a significant increase in E-wave deceleration time, E-wave velocity, and a marked decrease in LV end-diastolic pressure.

Additionally, Jin Ha et al.22 compared the effect of TAVI vs SAVR immediately and 3 months after aortic valve replacement on LV function and diastolic parameters. They found that more patients showed improvement in LV diastolic function grade in the TAVI than in the SAVR group (42% vs 11%). Early improvement in diastolic function grade with a significant decrease in E/e’ ratio and estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure was seen immediately in the TAVI group. Similar to our study, LV end-diastolic dimension and LV end-systolic dimension were significantly changed at 3 months after SAVR. This result could be explained by the frequent use of diuretics following surgery to manage pleural effusion and possible pulmonary edema. In contrast, mitral valve regurgitation did not differ significantly between the groups, and LV mass index did not show an immediate significant change in either group and started to decrease after 3 months.

Guarracino et al.,16 evaluated brain natriuretic peptides and LV diastolic function by mitral flow propagation velocity and mitral annulus early diastolic velocity, before and after valve procedures, and recorded improvement of LV diastolic parameters in the TAVI group with an increase in brain natriuretic peptides in the surgical group.

Similarly, Fairbairn et al.23 reported early regression in mass and reverse LV remodeling after TAVI compared with SAVR.

In contrast, Ngo et al.24 compared patients undergoing SAVR vs TAVI at 3 and 12 months and found a similar reduction in relative wall thickness in both groups and a more marked reduction in LV mass index in patients undergoing SAVR (17.5% vs 7.2%; P < .001).

In our study, patients who underwent TAVI showed little change in right ventricular function, with no change in tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion or further increase in estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure compared with those who underwent SAVR. Kempny et al.25 confirmed that TAVI did not influence right ventricular function, but that it worsened in patients undergoing SAVR.

Increased LV mass and the higher relative wall thickness generated by increased LV afterload in patients with severe AS are associated with reduced LV regional and global myocardial deformation assessed by 2D speckle tracking echocardiography. Therefore, LV-GLS can accurately assess LV myocardial contractility and can detect subclinical changes in LV performance in patients with AS,26 which improves after aortic valve replacement.27

Several studies have shown that TAVI is associated with a significant early improvement in LV strain parameters28-30 and that this such improvement is associated with a more favorable prognosis.25 Similar to our study, LV-GLS significantly improved immediately after TAVI while ejection fraction failed to show such a change.

Tsampasian et al.31 assessed LV-GLS before and after TAVI in 85 patients, with a mean follow-up of 49 ± 39 days. TAVI resulted in an early significant improvement of GLS (from −13.96 to −15.25, P = .01) as well as early LV mass regression with no change in ejection fraction percentage. The type of valve had no effect on LV function or remodeling after TAVI.

Mild or persistent moderate paravalvular leak is a known predictor of poor outcomes after TAVI.32 However, in our study, although more patients developed significant paravalvular leak after TAVI compared with SAVR in both short- and long-term follow-up, LV-GLS improved shortly after TAVI. This finding is supported by those of Kampaktsis et al.,33 who studied the impact of paravalvular leak on LV remodeling and LV-GLS and reported significant improvement in LV-GLS regardless of paravalvular leak, at the same time as it negatively affected LVEF percentage, LV mass regression, and diastolic function. A small number of our included patients could have negatively affected the statistical power of these findings. Patients predominantly with aortic regurgitation, or severe LV dysfunction (EF < 35%) were excluded to eliminate the adverse effect of such confounding factors on LV remodeling.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. The first is the small sample size due to the limited number of TAVI patients in our center at enrolment. A larger sample size would have enhanced the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Second, this is a single-center study with a lack of randomization, which could introduce selection bias and potentially affect the validity of the comparison between the 2 procedures. Third, we did not study other confounding factors affecting postoperative LV remodeling, such as hypertension, renal impairment, and baseline ventricular dysfunction. Fourth, the study reported follow-up data at 1 month and 1 year after the procedure. Longer-term follow-up would provide a more comprehensive understanding of LV remodeling outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Compared with individuals who underwent SAVR, those undergoing TAVI had earlier improvement of LV remodeling and LV diastolic function, with early reduction in LV mass index, E/e’ ratio, and significant early improvement of LV-GLS without concomitant changes in LVEF percentage, while maintaining right ventricular function. Nevertheless, these patients also showed rapid valve deterioration and a higher incidence of valvular and paravalvular leak. More TAVI patients experienced complete atrioventricular block, requiring permanent pacemaker implantation, and vascular complication related to the access site.

FUNDING

This study did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University (approval code: 36264PR12/1/23). Sex and gender variables were not taken into account in accordance with SAGER guidelines.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

No artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

S.B. El-Saied: design of the study, performing echocardiography for patients, and drafting the manuscript. R. Atlm and M. Elbarbary: data acquisition and analysis and revision of the manuscript and the results. A. Ghoneim and M.H. Sherif: contributed to manuscript drafting, data acquisition and analysis, and revision of the manuscript and the results. S.B. El-Saied, R. Atlm, A. Ghoneim, M.H. Sherif, and M. Elbarbary revised the work and approved the final version to be published.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Degenerative calcific AS is the most prevalent valvular heart disease globally. SARV is the gold standard for severe cases.

- TAVI has emerged as an alternative, less invasive treatment with short recovery and lower perioperative mortality.

- Aortic valve replacement significantly impacts LV remodeling, reduces symptoms, and increases overall survival.

- Current guidelines use LVEF percentage to assess LV function, but subclinical myocardial dysfunction can develop despite a normal LVEF percentage.

- GLS analysis has been used to accurately characterize regional and global myocardial systolic function, overcoming the limitations of ejection fraction.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- The study compared the impact of aortic valve replacement using TAVI vs SAVR on various parameters such as prosthesis hemodynamics, valvular leak, pacemaker implantation, and LV remodeling.

- TAVI showed earlier improvement in LV remodeling and diastolic function compared with SAVR, with reductions in LV mass index, E/e’ ratio, and improvements in LV-GLS while maintaining RV function.

- However, TAVI was associated with valve deterioration, valvular leak, and a higher incidence of pacemaker implantation and vascular complications.

REFERENCES

1. Thaden JJ, Nkomo VT, Enriquez-Sarano M. The global burden of aortic stenosis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;56:565-571.

2. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement in intermediate-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620.

3. Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1686-1695.

4. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack MJ, et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1609-1620.

5. Wenaweser P, Stortecky S, Schwander S, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with estimated low or intermediate surgical risk undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:1894-1905.

6. Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1706-1715.

7. Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH, et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:1695-1705.

8. Hein S, Arnon E, Kostin S, et al. Progression from compensated hypertrophy to failure in the pressure-overloaded human heart:structural deterioration and compensatory mechanisms. Circulation. 2003;107:984-991.

9. Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease:a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017;135:e1159-e1195.

10. Reisner SA, Lysyansky P, Agmon Y, Mutlak D, Lessick J, Friedman Z. Global longitudinal strain:a novel index of left ventricular systolic function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:630-633.

11. Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self-expanding bioprosthesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll of Cardiol. 2014;63:1972-1981.

12. Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults:an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;16:233-271.

13. Notomi Y, Shiota T, Popovic´ZB, et al. Measurement of ventricular torsion by two-dimensional ultrasound speckle tracking imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:2034-2041.

14. Sundt TM, Jneid H. Guideline update on indications for transcatheter aortic valve implantation based on the 2020 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines for management of valvular heart disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6:1088-1089.

15. Douglas PS, Berko B, Lesh M, Reichek N. Alterations in diastolic function in response to progressive left ventricular hypertrophy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:461-467.

16. Guarracino F, Talini E, Landoni G, Petronio S, Giannini C, Di Bello V. Effect of aortic valve surgery on left ventricular diastole assessed by echocardiography and neuroendocrine response:percutaneous versus surgical approach. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2010;24:25-29.

17. Provenchère S, Berroeta C, Reynaud C, et al. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I concentrations after adult cardiac surgery:association with postoperative cardiac dysfunction and 1-year mortality. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:995-1000.

18. Rieck ÅE, Gerdts E, Lønnebakken MT, et al. Global left ventricular load in asymptomatic aortic stenosis:covariates and prognostic implication (the SEAS trial). Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:1-8.

19. Salustri A, Cerquetani E, Piccoli M, et al. Relationship between B-type natriuretic peptide levels and echocardiographic indices of left ventricular filling pressures in post-cardiac surgery patients. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;7:1-7.

20. Bleiziffer S, Ruge H, Mazzitelli D, et al. Survival after transapical and transfemoral aortic valve implantation:talking about two different patient populations. J Thoracic Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138:1073-1080.

21. Gonçalves A, Marcos-Alberca P, Almeria C, et al. Acute left ventricle diastolic function improvement after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12:790-797.

22. Ha SJ, Yoo SY, Hong MK, Hong GR. Immediate and evolutionary recovery of left ventricular diastolic function after transcatheter aortic valve replacement:comparison with surgery. Yonsei Med J. 2020;61:30.

23. Fairbairn TA, Steadman CD, Mather AN, et al. Assessment of valve haemodynamics, reverse ventricular remodelling and myocardial fibrosis following transcatheter aortic valve implantation compared to surgical aortic valve replacement:a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Heart. 2013;99:1185-91.

24. Ngo A, Hassager C, Thyregod HGH, et al. Differences in left ventricular remodelling in patients with aortic stenosis treated with transcatheter aortic valve replacement with corevalve prostheses compared to surgery with porcine or bovine biological prostheses. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:39-46.

25. Kempny A, Diller GP, Kaleschke G, et al. Impact of transcatheter aortic valve implantation or surgical aortic valve replacement on right ventricular function. Heart. 2012;98:1299-304

26. Weideman F, Jamal F, Kowalski M, et al. Can strain rate and strain quantify changes in regional systolic function during dobutamine infusion, B-blockade, and atrial pacing—implications for quantitative stress echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:416-424.

27. Delgado V, Tops LF, van Bommel RJ, et al. Strain analysis in patients with severe aortic stenosis and preserved left ventricular ejection fraction undergoing surgical valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:3037-3047.

28. Giannini C, Petronio AS, Talini E, et al. Early and late improvement of global and regional left ventricular function after transcatheter aortic valve implantation in patients with severe aortic stenosis:an echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2011;1:264-273.

29. Kempny A, Diller GP, Kaleschke G, et al. Longitudinal left ventricular 2D strain is superior to ejection fraction in predicting myocardial recovery and symptomatic improvement after aortic valve implantation. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:2239-2243.

30. Schattke S, Baldenhofer G, Prauka I, et al. Acute regional improvement of myocardial function after interventional transfemoral aortic valve replacement in aortic stenosis:A speckle tracking echocardiography study. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:15.

31. Tsampasian V, Panoulas V, Jabbour RJ, et al. Left ventricular speckle tracking echocardiographic evaluation before and after TAVI. Echo Res Pract. 2020;7:29-38.

32. SáMP, Jacquemyn X, Van den Eynde J, et al. Impact of Paravalvular Leak on Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation:Meta-Analysis of Kaplan-Meier-derived Individual Patient Data. Struct Heart. 2023;7:100118.

33. Kampaktsis PN, Subramayam P, Sherifi I, et al. Impact of paravalvular leak on left ventricular remodeling and global longitudinal strain 1 year after transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Future Cardiology. 2021;17:337-345.

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: mohammed.elbarbary@med.tanta.edu.eg (M. Elbarbary).

ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has become the gold standard to measure the size of the aortic annulus and better select the size of transcatheter heart valves (THV) in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). However, in selected cases, CCTA may not be feasible. Angiographic aortic annulus (AAA) measurements during TAVI may be an alternative and should be evaluated for precision regarding the proper selection of THV sizes. We sought to investigate the correlation between AAA and CCTA measurements for the proper selection of balloon-expandable valve (BEV) sizes in patients undergoing TAVI.

Methods: Patients undergoing TAVI with BEV and high-quality CCTA were included. AAA measurements were obtained in the standard 3-cusp view after aortic root aortography. Angiographic distance between non- and left coronary cusps were compared to CCTA annulus measurements. Endpoints were diagnostic tests and correlations between angiographic and CCTA measurements, and the composite endpoint of the VARC-3-defined efficacy (technical success, correct position, and intended performance), and safety profile (multiple valves, valve embolization, pacemaker implantation, and more than moderate valvular regurgitation).

Results: Regarding the Sapien family of THV, aortography-based distance measurements showed a correlation of 0.528 (P < .01), 0.451 (P < .01), and 0.579 (P < .01) for 23 mm, 26 mm, and 29 mm valves with CCTA-based distance measurements. No difference was seen regarding the VARC-3-defined efficacy (94.2% vs 96.0%; P = .60) and safety profile (90.9% vs 91.9%; P = .84) among cases showing discordant and concordant pairs of measurements.

Conclusions: AAA measurement showed a moderate diagnostic test and Spearman’s correlation coefficient compared to CCTA-based annulus assessment for perioperative THV size selection. This strategy could potentially enable TAVI in patients in whom access to preoperative CCTA is not available.

Keywords: Non-coronary cusp. Left coronary cusp. Aortography. Angiographic aortic annulus measurements. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La angiografía por tomografía computarizada (angio-TC) es el estándar para medir el anillo aórtico en pacientes tratados mediante implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica (TAVI), aunque en algunos casos podría no ser factible. Debería evaluarse la precisión de las medición del anillo aórtico angiográfica (AAA) durante el TAVI como alternativa para elegir el tamaño correcto de la válvula cardiaca percutánea. Por ello, investigamos la correlación entre las mediciones angiográficas y por angio-TC para elegir el tamaño adecuado de la válvula en pacientes que reciben un TAVI.

Métodos: Se incluyeron pacientes de TAVI con prótesis de balón expandible y angio-TC de alta calidad. Las mediciones del AAA se obtuvieron de la angiografía de la raíz aórtica en proyección de 3 cúspides. Se comparó la distancia angiográfica entre la cúspide izquierda y no coronariana con las mediciones de angio-TC. Se evaluaron la prueba diagnóstica y la correlación entre las medidas angiográficas y de angio-TC, así como la eficacia (éxito técnico, posición correcta y desempeño intencionado) y la seguridad (múltiples válvulas, embolización, implante de marcapasos e insuficiencia valvular moderada o mayor) definida por VARC-3.

Resultados: Para válvulas con balón expandible de 23 mm, la distancia en la aortografía tuvo una correlación de 0,528 (p < 0,01) comparada con las mediciones de angio-TC; para las de 26 mm, la correlación fue de 0,451 (< 0,01), y para las de 29 mm fue de 0,579 (< 0,01). No hubo diferencia en cuanto a eficacia (94,2 frente a 96,0%; p = 0,60) y seguridad (90,9 frente a 91,9%; p = 0,84) entre casos con medidas concordantes y discordantes.

Conclusiones: Las mediciones del AAA mostraron un moderado valor de prueba diagnóstica y de correlación Spearman en comparación con la angio-TC para elegir el tamaño de la válvula cardiaca percutánea. Esta estrategia podría permitir un TAVI en situaciones en que la angio-TC no esté disponible.

Palabras clave: Cúspide no coronariana. Cúspide coronaria izquierda. Aortografía. Mediciones angiográficas del anillo aórtico. Implante percutáneo de válvula aórtica.

Abbreviations

BEV: balloon-expandable valve. CCTA: coronary computed tomography angiography. LCC: left coronary cusp. NCC: non-coronary cusp. TAVI: transcatheter aortic valve implantation. THV: transcatheter heart valve.

INTRODUCTION

During transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) remains the key factor to determine the characteristics of the aortic valve and predefine the size of annular valve prior to the selection of specific transcatheter heart valves (THV).1,2 Several CCTA protocols were described to achieve reproducible and reliable aortic annulus measurements.3,4 At the same time, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic measurements were used to determine the aortic valve annular size showing good correlation with the gold standard of direct surgical and CCTA-based measurements.5,6 However, CCTA showed better image quality acquisition, detailed evaluation of the aortic annulus, and other useful anatomies for transfemoral TAVI (aorto-iliac-femoral vessels)7 making CCTA the default strategy for preoperative planning.

Adequate THV size selection is an important factor to prevent patient-prosthesis mismatch and reduce the risk of over- and under-sizing and, hence, the increased risk of all cause-mortality and unplanned repeat reintervention.6,8,9 While CCTA has been established as the gold standard method for annular sizing pre-TAVI implantation,4 an associated risk between radiation exposure and cancer, and contrast media and nephropathy has also been described.10,11 Furthermore, in selected cases, CCTA may not be feasible prior to TAVI following emergency clinical indications and/or the patients’ unstable conditions.

Aortography-only annular measurement was described as an efficient technique to determine the size of aortic annulus and select the size of the THV.12,13 Based on the standard 3-cusp view, the angiographic determination of anatomical dimensions with contrast media (and/or balloon-sizing) can facilitate the identification of proper annular size when CCTA-based sizing is not available.14-17 Aortography-based measurements have been shown to correlate with direct anatomical preoperative aortic annulus measurements.13

Against this background, we sought to investigate whether angiographic aortic valve annular measurements between the non-coronary (NCC) and left coronary cusp (LCC) correlate with CCTA-based measurements to facilitate proper size selection of the THV in a retrospective, all-comers, single-center cohort of patients undergoing TAVI.

METHODS

Study population

This retrospective, observational analysis evaluated all consecutive patients undergoing transfemoral TAVI following heart team evaluation at the German Heart Center cardiovascular disease unit in Munich, Germany. Transfemoral TAVI was performed using a minimalistic approach18 in all cases, while THV size selection was left to the operator’s discretion based on size chart, CCTA measurements, anatomical factors including calcium distribution and severity, aortic valve annular size, coronary height, and disease.

All patients with native tricuspid calcified aortic valve disease, and available high-quality CCTA for TAVI were included in this study. Procedural information was obtained from a customized database and screened for all patients treated from January 2014 through December 2021 at the German Heart Center in Munich, Germany. During this period, a total of 2500 transfemoral TAVI cases were performed using commercially available balloon-expandable (1865) and self-expanding (635) THVs. Only those who received the SAPIEN 3 or the SAPIEN 3 Ultra (Edwards Lifesciences, United States) balloon-expandable valves (BEV) were included in this analysis.

The study was performed in full compliance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients gave their written informed consent to undergo the procedure. Ethical approval was obtained from the Technical University of Munich ethical committee under registry no. OBSERVTAVI (#525/17). CCTA measurements were performed before THV implantation. Angiographic aortic valve annular measurements between the NCC and LCC were performed offline and documented in the database. The baseline clinical and procedural characteristics (including size of the implanted THV and angiographic aortic regurgitation after implantation), and test lab results were obtained from registry data or the clinical records, as appropriate. Regarding the Valve Academic Research Consortium 3 (VARC-3) defined safety and efficacy profile, in-hospital and discharge follow-up was monitored and registered. A 30-day follow-up was established via telephone call, hospital visits or follow-up letter.

Coronary computed tomography angiography measurements

CCTA was analyzed by 1 experienced cardiologist (HA) while a second experienced cardiologist (JM) analyzed a sample of 40 cases to determine inter-observer variability. Using multi-slice computed tomography reconstruction, quantitative measures of the aortic valve annular size (minimum, maximum and mean diameter, perimeter, and area) were obtained based on predefined protocols2 using 3-Mensio software (Pie Medical Imaging, The Netherlands). In summary, the 3 hinge points of the aortic cusps were detected and selected. After proper identification of the 3 hinge points, the aortic annulus was seen in automatic multiplanar reconstruction. Annular measurements were obtained 0.5 mm below the hinge points, and the aortic valve annular contour was traced to calculate the perimeter-derived area and diameter (figure 1A). To define the direct one-planar measurement between the NCC and the LCC on the CCTA, a straight line between the red (LCC) and yellow (NCC) hinge points was used to determine length (figure 1B,C). The most appropriate THV size was selected based on size chart recommendations and anatomical considerations (figure 1D). CCTA-based measurements and calculations were used to determine the proper THV size according to commercial size charts supplied by the manufacturer. The mean diameter and area of the aortic annulus were used to select the THV size (23 mm, 26 mm, and 29 mm) and then coded as a binary variable for each size category; when only 1 measurement was within the proposed range for a specific THV size based on the manufacturer’s size chart (within the gray zone), the area was used to decide the final THV size.

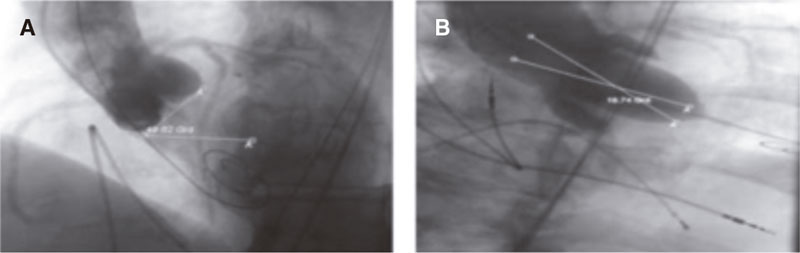

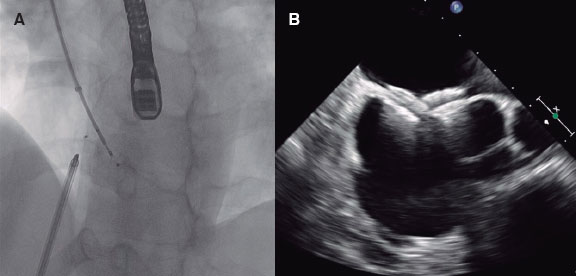

Figure 1. Central illustration. A: aortic annulus CCTA measurements determining the minimum (19.6 mm), maximum (25.9 mm), and mean (22.8 mm) diameter, perimeter (73 mm), and area (394 mm2). B: CCTA measurement from the lowest point between the left coronary cusp (red dot) and the non-coronary cusp (yellow dot) with a 23.0 mm distance. C: CCTA prediction of angiographic angulation to obtain the standard 3-cusp view (cranial right anterior oblique view of first and seventh nerves) with the left-coronary cusp from 1 side (red dot) and the non-coronary cusp on the other side (yellow dot), and the distance between them (23.0 mm). D: angiographic result after balloon-expandable valve implantation based on the tomographic measurements shown on figure 1 A (SAPIEN 3 Ultra 23 mm).

Aortographic measurements

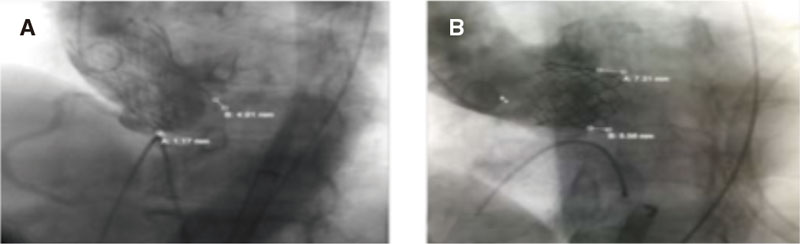

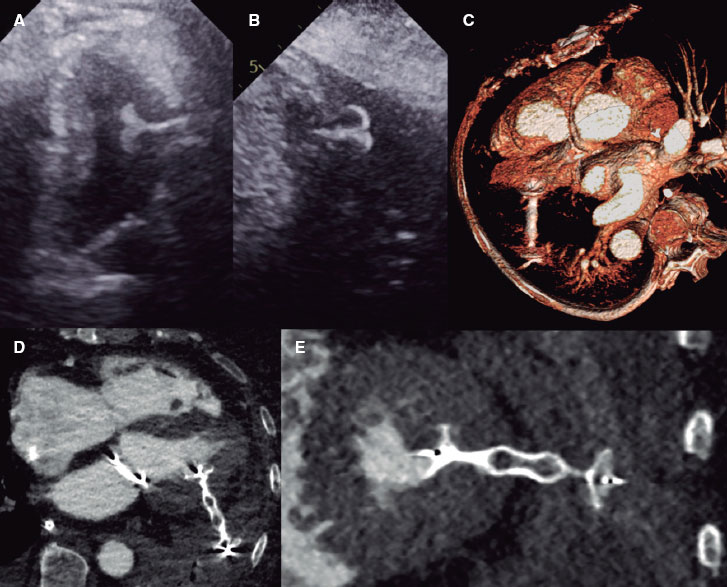

All procedures were performed by experienced TAVI operators using a monoplane digital flat panel detector X-ray system (Allura Xper FD 10 C, Royal Philips, The Netherlands) in a dedicated hybrid cath lab. All fluoroscopic 3-cusp view images were analyzed after completion of the procedure and images with distance measurements saved. Angiographic measurements were obtained offline from the angiographic aortic root injection (native annulus without the implanted THV) using a 5-Fr pigtail catheter placed in the right coronary cusp in the standard 3-cusp view.14,15 The distance between the NCC and LCC hinge points was measured by experienced cardiologists (HA and JM) using dedicated Phillips software (figure 2A-H). Angiographic measurements were performed after automatic (based on calibration factor determined by the software) and manual (using the 5-Fr catheter as reference calibration factor) calibration to determine the distance in millimeters.

Figure 2. A: standard 3-cusp cranial right anterior oblique view of first and seventh nerves (red circle) to determine longitudinal measurement (yellow arow) in the best contrasted image (green circle). B: calibration option based on the best image available (yellow arrow). C: measurement option (red arrow) to determine the distance on the aortic annulus (yellow size) on the images saved (green circle). D: saved image (red arrow) to “start analysis” (yellow arrow). E: manual calibration based on the 5-Fr catheter (red arrow and arrowhead) drawing 2 lines over the catheter (red circle) comparing the calibration factor given by the software (0.1451 mm/pixels, yellow arrow) to the one obtained through manual calibration (0.1486 mm/pixels, yellow arrowhead). F: “longitudinal measurement” option should be selected (red arrow) drawing a line at the hinge point of the left and non-coronary cusp (red circle). G: for automatic calibration, select “accept automatic calibration” (yellow arrow); the calibration factor given by the software (0.1451 mm/pixels) will be used for measurement purpose (yellow arrowhead, calibration factor of 0.1451 mm/pixels). H: aortic valve annulus measurement using automatic calibration selecting “longitudinal measurement” (red arrow) and drawing a line between the hinge points of the left and non-coronary cusp (red circle).

Endpoints

Endpoints were the correlation between angiographic and CCTA measurements of the distance between the NCC and the LCC. The rates of the VARC-3-defined efficacy (technical success, correct position, and intended performance using VARC-319 definitions) and safety profile (multiple valves, valve embolization, pacemaker implantation, and more than moderate valvular regurgitation using VARC-3 definitions) in patients with concordant and discordant measurements between angiographic and CT-based measurements were also analyzed.

Rates of in-hospital complications defined as conversion to surgery, perioperative death, life-threating bleeding, major and minor bleeding, major and minor vascular complications, and in-hospital mortality in patients with concordant and discordant measurements were reported. The 30-day mortality rate, chronic heart failure, stroke, valve dysfunction, aortic mean gradient, and aortic regurgitation were reported too.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and proportions and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Continuous data were tested for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test and expressed as mean (± standard deviation) or median (interquartile range [IQR]) as appropriate, and then compared, respectively, using the unpaired t test or the Mann-Whitney U test.

The study population was divided into derivation (n = 1256), and validation cohort (n = 40 cases). The study group of interest was obtained from the derivation cohort (n = 393). In the derivation cohort, selection of specific THV sizes (23 mm, 26 mm, and 29mm) based on the gold standard CCTA assessment was categorized as a binary variable and then compared to the THV size selection derived from aortography. Subsequently, logistic regression analysis was performed using the binary variable from the CCTA-based THV selection as a dependent variable while aortographic distance measurements were considered an independent variable. Afterwards, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was analyzed to identify optimal cut-off criteria (distance in mm, Youden’s index) and determine individual diameter ranges based on aortographic distance measurements of each category of THV sizes. The lowest value from the smallest THV and the highest value from the largest THV was determined using the 25th and 75th IQR, respectively, taken from the distribution of the derivation population. The suggested THV size was derived using aortography with manual or automatic calibration. Sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values, as well as positive and negative likelihood were used to determine diagnostic accuracy index. Bland-Altman plots were used to test correlation between the CT NCC-LCC and the NCC-LCC aortography with manual calibration and NCC-LCC aortography with automatic calibration.

Inter- and intra-observer analysis using intraclass correlation coefficient (with absolute agreement) and Pearson correlation coefficient for dichotomized data were performed in a sample of 40 cases between the 2 independent cardiologists.

To perform internal validation, previously established cut-off values to determine THV size by aortography were applied in a separate cohort of 40 patients (validation cohort) and compared using the gold standard CCTA-based sizing determination.

Pairs of sizing results based on angiography and CCTA were generated as a study group of interest and classified as concordant or discordant after comparison using the chi square test or Fischer’s exact test, unpaired t test or the Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software package (version 27, IBM Corporation, United States). All tests were 2-sided at the 0.05 significance level.

RESULTS

After exclusion, 1256/2500 (50.2%) patients who received a BEV were evaluated in the validation cohort (figure 3). Aortography-based diameter measurements were feasible in 393 of these patients (15.7%) (study group of interest).

Figure 3. Study enrollment flow diagram.

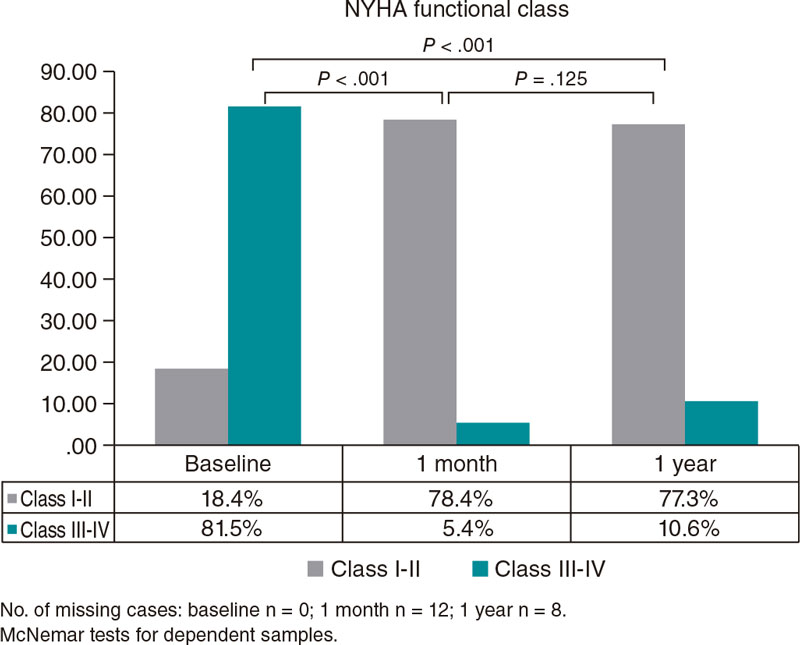

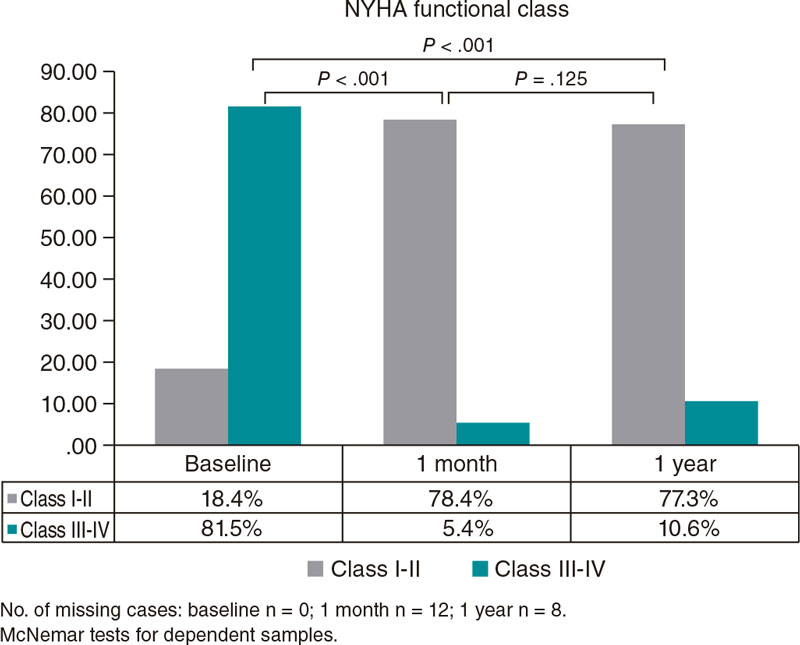

Baseline and CCTA characteristics are shown on table 1. The median age of the entire population was 81 (77-85) years, 34.3% female, with a left ventricular function of 60% [47-60], and a median EuroScore II of 3.74 (2.14-6.24).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics

| Balloon-expandable valve (N = 393) | |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 81 [77 - 85] |

| Men | 257 (65.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.2 [23.8-29.5] |

| BSA, m2 | 1.92 ± 0.22 |

| NYHA functional class III-IV | 238 (60.9) |

| CCS class III-IV | 32 (8.2) |

| Arterial hypertension | 353 (90.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 131 (33.5) |

| Dyslipidemia | 265 (67.8) |

| COPD | 19 (4.9) |

| Smoking history | 123 (31.5) |

| PAD | 77 (19.7) |

| Previous PCI | 162 (41.4) |

| CAD | 341 (87.2) |

| 1 vessel | 204 (52.2) |

| 2 vessels | 57 (14.6) |

| 3 vessels | 80 (20.5) |

| Pacemaker implantation | 36 (9.2) |

| Previous MI | 43 (11) |

| Previous CABG | 37 (9.5) |

| Previous Stroke/TIA | 60 (15.3) |

| Atrial fibrilation | 149 (38.1) |

| Creatinine levels, mg/dL | 1.11 [0.89-1.37] |

| eGRF, mL/min | 60 [46-76] |

| Dialysis | 3 (0.8) |

| Aortic regurgitation grade 2+ | 39 (10) |

| AVA, mm2 | 0.70 [0.60-0.84] |

| LVEF, % | 60 [47-60] |

| Mean Ao gradient, mmHg | 42 [36-49] |

| Peak Ao gradient, mmHg | 68 [59-80] |

| sPAP, mmHg | 42 [33-45] |

| EuroScore I, % | 11.84 [7.82-19.46] |

| EuroScore II, % | 3.74 [2.14 - 6.24] |

| CCTA measurements | |

| Minimum diameter, mm | 21.6 [20.1-23.2] |

| Maximum diameter, mm | 27.9 [26.2-29.6] |

| Mean diameter, mm | 24.8 [23.2-26.3] |

| Area, mm2 | 474 [414-533] |

| Perimeter, mm | 79 [74-84] |

| Visual estimate of the severity of valve calcification | |

| Mild | 80 (20.5) |

| Moderate | 185 (47.3) |

| Severe | 126 (32.2) |

| Visual estimate of the severity of annular calcification | |

| None | 55 (14.1) |

| Mild | 268 (68.5) |

| Moderate | 67 (17.1) |

| Severe | 1 (0.3) |

| Visual estimate of the severity of LVOT calcification | |

| None | 223 (57) |

| Mild | 145 (37.1) |

| Moderate | 23 (5.9) |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean ± standard deviation or mean [interquartile range]. |

|

Procedural characteristics are shown on table 2. Procedural time, fluoroscopic dose, and fluoroscopic time were 48 min [38-59], 919 [444-1712] cGys/cm2, and 10.9 min [8.2-14.7], respectively. Technical success was achieved in 95.4% of the cases. Regarding in-hospital complications (table 3), there rates of major bleeding events, major vascular complication, and in-hospital mortality were 16.1%, 14.6%, and 1.5%, respectively.

Table 2. Procedural characteristics

| Balloon-expandable valve (N = 393) | |

|---|---|

| Elective | 389 (99.5) |

| Need for intubation | |

| Prophylactic | 5 (1.3) |

| Emergency | 8 (2) |

| Use of ECMO | |

| Prophylactic | 0 (0) |

| Emergency | 1 (0.3) |

| Use of cerebral protection device | 16 (4.1) |

| Size of the valve implanted | |

| 23 mm | 118 (30.2) |

| 26 mm | 207 (52.9) |

| 29 mm | 66 (16.9) |

| THV implanted | |

| SAPIEN 3 | 95 (24.3) |

| SAPIEN 3 Ultra | 296 (75.7) |

| Predilatation | 166 (42.5) |

| Postdilatation | 54 (13.8) |

| Contrast media, mL | 139 [110-172] |

| Fluoroscopic time, min | 10.9 [8.2-14.7] |

| Fluoroscopic dose, cGys/cm2 | 919 [444-1712] |

| Procedural time, min | 48 [38 - 59] |

| Technical success | 373 (95.4) |

| Procedural success | 384 (98.2) |

| Intended performance | 380 (97.2) |

| Correct position | 389 (99.5) |

| Multiple valves | 1 (0.3) |

| Access site complications | 18 (4.6) |

| THV embolization | 1 (0.3) |

| Cardiac tamponade | 5 (1.3) |

| Annular rupture | 3 (0.8) |

| Coronary impairment | 0 (0) |

| Procedural CPR | 2 (0.5) |

| Conversion to surgery | 4 (1) |

| Procedural mortality | 3 (0.8) |

| Angiographic AR ≥ moderate | 5 (1.3) |

| Postoperative mean gradient, mmHg | 9 [5-10] |

| Days at the ICU | 1 [1-1] |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean ± standard deviation or mean [interquartile range]. |

|

Table 3. In-hospital complications

| Balloon-expandable valve (N = 393) | |

|---|---|

| Life-threatening bleeding | 11 (2.8) |

| Major bleeding | 63 (16.1) |

| Minor bleeding | 65 (16.6) |

| Major vascular complications | 57 (14.6) |

| Minor vascular complications | 80 (20.5) |

| TIA | 0 (0) |

| Major stroke | 4 (1) |

| Minor stroke | 5 (1.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 3 (0.8) |

| New pacemaker implantation | 26 (6.6) |

| In-hospital mortality | 6 (1.5) |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%). |

|

No differences were reported regarding the efficacy (94.2% vs 96%; P = .60) and safety profile (90.9% vs 91.9%; P = .84) between discordant and concordant pairs of tomographic and angiographic measurements using aortography with manual calibration, respectively (table 4).

Table 4. Procedural complications in concordant and discordant valve sizes using manual and automatic calibration in aortography vs CCTA (N = 393)

| All (N = 393) | Discordant (N = 121) | Concordant (N = 272) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy | 375 (95.4) | 114 (94.2) | 261 (96.0) | .60a |

| Technical success | 386 (98.2) | 118 (97.5) | 268 (98.5) | .44b |

| Correct position | 391 (99.5) | 120 (99.2) | 271 (99.6) | .52b |

| Intended performance | 382 (97.2) | 117 (96.7) | 265 (97.4) | .74b |

| Safety | 360 (91.6) | 110 (90.9) | 250 (91.9) | .84a |

| Multiple valves | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | > .99b |

| THV embolization | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) | > .99b |

| New pacemaker implantation | 27 (6.9) | 9 (7.4) | 18 (6.6) | .83a |

| AR > moderate after valve implantation | 5 (1.3) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (1.1) | .64b |

| Conversion to surgery | 4 (1.0) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (1.1) | > .99b |

| Procedural mortality | 3 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | > .99b |

| Life-threatening bleeding | 11 (2.8) | 5 (4.1) | 6 (2.2) | .32b |

| Major bleeding | 64 (16.3) | 20 (16.5) | 44 (16.2) | > .99a |

| Minor bleeding | 66 (16.8) | 16 (13.2) | 50 (18.4) | .24a |

| Major vascular complications | 58 (14.8) | 17 (14) | 41 (15.1) | .87a |

| Minor vascular complications | 81 (20.6) | 22 (18.2) | 59 (21.7) | .50a |

| In-hospital mortality | 6 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (1.5) | > .99b |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%). |

||||

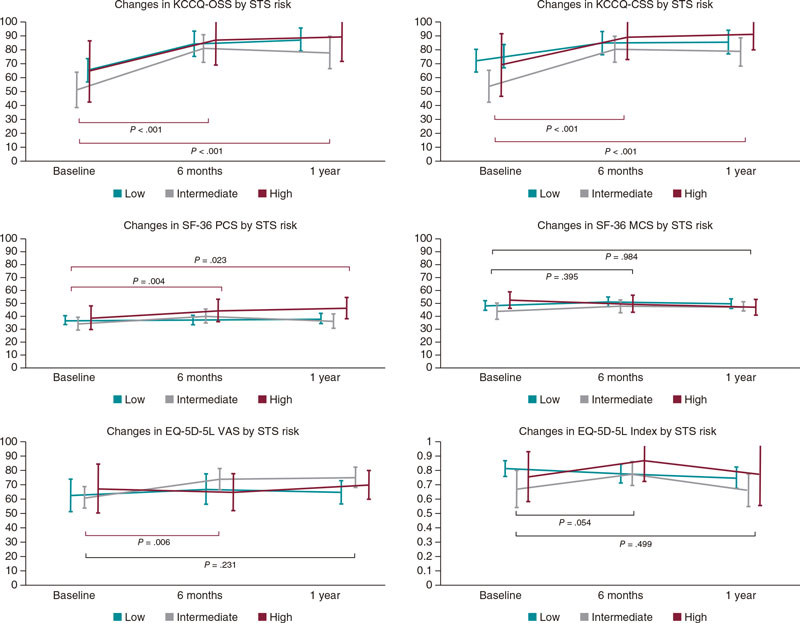

A moderate correlation was seen between CCTA-based assessment and aortographic THV size determination: 23 mm, 26 mm, and 29 mm THV sizes were associated with Spearman’s correlation coefficients of 0.528 (P < .01), 0.451 (P < .01), and 0.579 (P < .01), respectively. For more details, see tables 1-3 of the supplementary data.

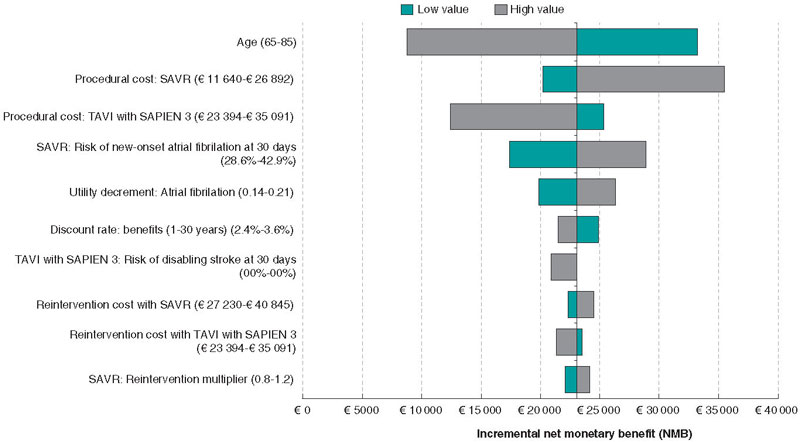

The suggested angiographic cut-off values for each THV size are shown on table 5. In brief, the best diameter range for selecting 23 mm BEVs was 18.46 mm to 22.55 mm; for 26 mm THVs the best diameter range was 21.55 mm to 24.55 mm while for 29 mm THVs the best diameter range was ≥ 24.25 mm to < 28.50 mm. The intra- and inter-observer intraclass correlation coefficients were 0.931 (95%CI, 0.869-0.963; P < .01), and 0.902 (95%CI, 0.814-0.948; P < .01), respectively (see table 4 of the supplementary data). The CT NCC-LCC distance and NCC-LCC showed an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.885 (95%CI, 0.834-0.920; P < .01) (figure 4).

Table 5. Suggested angiographic size chart for the Sapien balloon-expandable valve

| 23 mm | 26 mm | 29 mm | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N-L CC distance | 18.46–22.55 | 21.55–24.55 | 24.25–28.50 |

|

mm, millimeter; mm2, square millimeters; N-L CC, non-to-left coronary cusp. |

|||

Figure 4. Bland-Altman plots: A: CCTA vs AOMC; B: CCTA vs AOAC. AOAC, aortography with automatic calibration; AOMC, aortography with manual calibration; CCTA, coronary computed tomography angiography; CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; SD, standard deviation.

The values obtained were tested and compared with the validation cohort (n = 40) showing moderate-to-good diagnostic test analysis with a good Spearman’s correlation coefficient [0.711 (95%CI, 0.506-0.840; P = < .01)], and moderate diagnostic accuracy (table 5 of the supplementary data). The validation cohort of 40 patients is shown on tables 6 to 10 of the supplementary data.

The 30-day follow-up is shown on table 6. There was no difference in 30-day mortality between discordant and concordant tomographic and angiographic measurements (1.7% vs 2.6%; P = .73). There was no difference at 30 days regarding the mean gradient (11 [10-16] vs 12 [10-15] mmHg; P = .76), and more than moderate aortic regurgitation (3.2% vs 1.1%; P = .34) using aortography with manual calibration between discordant and concordant tomographic and angiographic measurements, respectively.

Table 6. 30-day follow-up comparing concordant vs discordant measurements using balloon-expandable valve

| Total (N = 393) | Discordant (N = 121) | Concordant (N = 272) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 9 (2.3) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (2.6) | .72a |

| CHF | 24 (6.1) | 8 (6.6) | 16 (5.9) | .82b |

| Stroke | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.7) | > .99a |

| Valve dysfunction | 8 (2) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (2.2) | > .99a |

| LVEF, %, (n 278) | 60 [60-60] | 60 [57-60] | 60 [50-60] | < .01c |

| Mean gradient, mmHg (n = 265) | 12 [10-15] | 11 [10-16] | 12 [9.8-15] | .76c |

| AR > moderate, (n = 279) | 5 (1.8) | 3 (3.2) | 2 (1.1) | .33a |

| NYHA ≥ III, (n = 345) | 18 (5.2) | 5 (4.6) | 13 (5.5) | .80a |

|

Data are expressed as no. (%), mean ± standard deviation or mean [interquartile range]. |

||||

Discussion

This single-center, retrospective, observational study investigated the correlation and diagnostic accuracy between angiographic and tomographic measurements to determine THV size according to 1 single angiographic measurement between the NCC and the LCC in patients treated with BEV.

Regarding this objective, the most salient findings are a) angiographic aortic valve annular size determination based on distance measurements between the NCC and LCC is reproducible; b) diagnostic accuracy between CCTA-based and angiography-based aortic valve annular size determination is of moderate strength (table 5 of the supplementary data); and c) internal validation of previously established diameter ranges for angiography-based aortic valve annular size determination revealed moderate diagnostic accuracy.

We found a moderate overall diagnostic accuracy and correlation between angiographic and CCTA measurements to determine aortic valve annular size for THV selection. The use of angiography only measurements may expand the minimalistic TAVI approach in scenarios where CCTA is not an option or is unavailable.