ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: The early administration of unfractionated heparin (UFH) for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is still a matter of discussion, and clinical practice guidelines leave the timing of administration prior to angioplasty at the physician’s discretion.

Methods: We conducted a systematic search across PubMed/Cochrane databases for studies comparing pre-treatment with UFH with a comparative untreated group (non-UFH) of patients with STEMI undergoing primary angioplasty and including TIMI flow and 30-day mortality targets from June 2024 through September 2024. We conducted a randomized meta-analysis and assessed the risk of publication bias to detect asymmetry in the included studies.

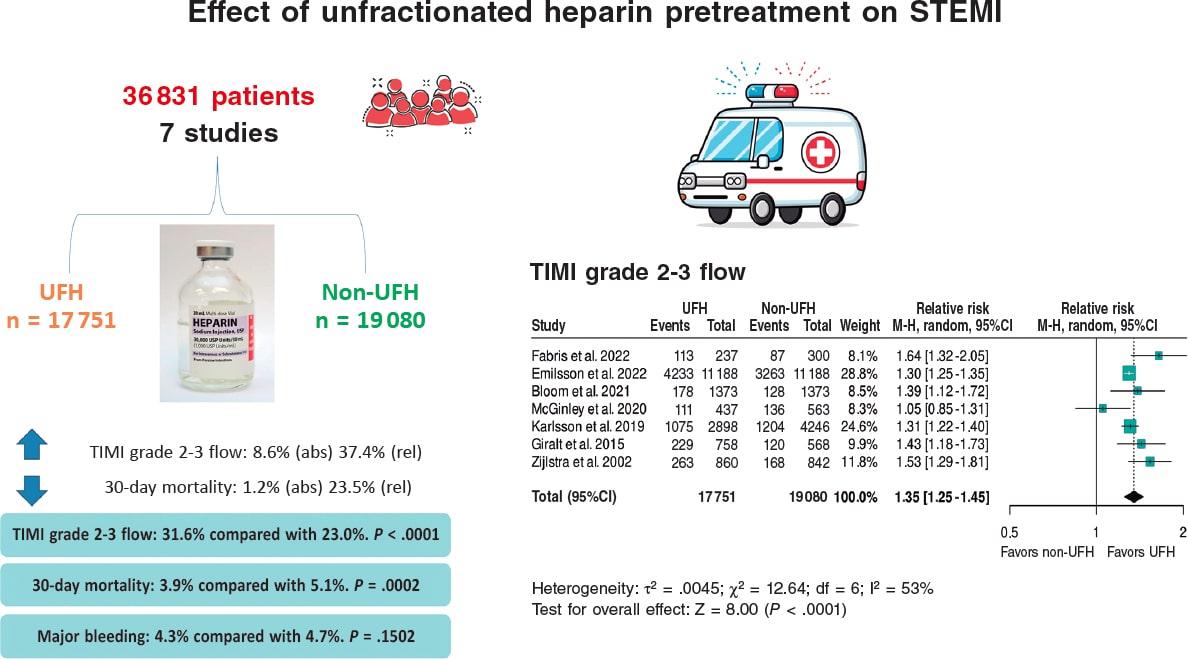

Results: We included a total of 7 studies published from 2002 through 2022 (6 retrospective trials and 1 substudy of a randomized trial) for a total of 36 831 patients: 17 751 in the UFH pre-treatment group and 19 080 in the non-UFH control group. A total of 6202 patients (31.6%) on UFH had TIMI grade-II/III flow vs 5106 (23.0%) on non-NFH while 490 (3.9%) on UFH died within 30 days vs 673 (5.1%) on non-NFH. Meta-analysis demonstrated a higher probability of TIMI grade-II/III flow (HR, 1.35; 95%CI, 1.25-1.45; P < .0001) and a lower 30-day mortality rate in patients on UFH pretreatment (HR, 0.80; 95%CI, 0.72-0.90; P = .0002), with no differences being reported in bleeding complications (HR, 0.87; 95%CI, 0.72-1.05; P = .150).

Conclusions: Meta-analysis of studies shows that pretreatment with UFH in STEMI patients undergoing primary angioplasty is associated with a higher probability of TIMI grade-II/III flow and a lower risk of early mortality.

Meta-analysis registered in PROSPERO (CRD420250655362).

Keywords: Meta-analysis. Unfractionated heparin. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Prognosis. Pre-treatment. Acute myocardial infarction.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: La administración temprana de heparina no fraccionada (HNF) en el infarto agudo de miocardio con elevación del segmento ST (IAMCEST) está sujeta a controversia, por lo que las guías de práctica clínica dejan a criterio médico el momento de su administración antes de la angioplastia.

Métodos: Entre junio y septiembre de 2024 se realizó una búsqueda sistemática en PubMed y Cochrane de estudios que comparasen el pretratamiento con HNF con un grupo control no tratado (no-HNF) en pacientes con IAMCEST tratados con angioplastia primaria e incluyesen los objetivos de flujo TIMI y la mortalidad a 30 días. Se llevó a cabo un metanálisis aleatorizado, en el que se evaluó el riesgo de sesgo de publicación para detectar asimetría en los estudios incluidos.

Resultados: Se incluyeron 7 estudios publicados entre 2002 y 2022, de los cuales 6 eran retrospectivos y 1 subestudio de un ensayo aleatorizado, con 36.831 pacientes: 17.751 el grupo de pretratamiento con HNF y 19.080 el grupo control no-HNF. Un total de 6.202 (31,6%) con HNF tuvieron flujo TIMI II/III, frente a 5.106 (23,0%) de los no-HNF, y 490 (3,9%) con HNF fallecieron en 30 días, frente a 673 (5,1%) de los no-HNF. El metanálisis demostró mayor probabilidad de flujo TIMI II/III (HR = 1,35; IC95%, 1,25-1,45; p < 0,0001) y menor mortalidad en los pacientes que recibieron pretratamiento con HNF (HR = 0,80; IC95%, 0,72-0,90; p = 0,0002), sin diferencias en complicaciones hemorrágicas (HR = 0,87; IC95%, 0,72-1,05; p = 0,150).

Conclusiones: El metanálisis muestra que el pretratamiento con HNF en pacientes con IAMCEST y angioplastia primaria se asocia a una mayor probabilidad de flujo TIMI II/III y un menor riesgo de mortalidad precoz.

Metanálisis registrado en PROSPERO (CRD420250655362).

Palabras clave: Metanálisis. Heparina no fraccionada. Infarto con elevación del segmento ST. Pronóstico. Pretratamiento. Infarto agudo de miocardio.

Abbreviations

PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention. STEMI: ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. UFH: unfractionated heparin.

INTRODUCTION

The implementation of STEMI Code protocols, involving emergency and cardiology services, has led to improved care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and lower morbidity and mortality rates.1 Correct diagnosis of STEMI, pretreatment with antiplatelet agents, and the organization of rapid and direct transfer to a center with an PCI-capable center for primary angioplasty are quality standards in the management of STEMI.1

Parenteral anticoagulation is generally recommended in acute coronary syndrome at the time of diagnosis.1 In STEMI, the use of unfractionated heparin (UFH) during primary angioplasty is recommended to prevent coronary thrombosis and device-related complications, but its use should be discontinued after the procedure.2

The precise role of UFH pretreatment at the time of first medical contact for patients diagnosed with STEMI remains to be fully defined. The 2023 clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology1 allow attending physicians to decide when to administer UFH during treatment, as there is no solid evidence supporting its early use. This flexibility is based on the absence of conclusive data on the benefits of UFH at this stage of treatment.1,3

The most recent data published on the implementation of STEMI Code protocols and care networks in Spain reveal heterogeneity in response times and transport among the different autonomous communities (AC).4,5 This heterogeneity is also observed in the administration of anticoagulant and antiplatelet pretreatment across the 17 AC. A review of STEMI Code protocols as of December 2024 shows that in 6 of the 17 (35.3%) AC, pretreatment with UFH is recommended, representing coverage for 43.1% of the Spanish population (table 1 of the supplementary data). All AC, except for one, include dual antiplatelet therapy as pretreatment at the first medical contact in their protocols. Differences in the standardization of UFH use in STEMI Code protocols reflect the lack of evidence and concrete recommendations on this topic.

Table 1. Demographic data of populations and characteristics of the selected studies

| Study | Design | Country | n | n (%) | Age, years | Concomitant antiplatelets, drug, and dosis | Male sex | Door-to-balloon time | UFH dosis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | ||||

| Fabris et al. (2022)10 | Retrospective | Italy | 537 | 237 (44.1%) | 300 (55.9%) | 66.0 ± 12.5 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | ASA: 237, 250 mg (100%) Ticagrelor: 237, 280 mg (100%) | ASA: 300, 250 mg (100%) PCI-capable center: UFH + ticagrelor or prasugrel or clopidogrel | 176 (74.3%) | 226 (75.3%) | 77 | 74 | 70 IU/kg | 70 IU/kg |

| Emilsson et al. (2022)6 | Retrospective | Sweden | 22 376 | 11 188 (50.0%) | 11 188 (50.0%) | 67.0 ± 12.0 | 67.0 ± 12.0 | ASA: 226, NR (2%) Clopidogrel: 221, NR (22%) Ticagrelor: 4642, NR (41%), Prasugrel: 574, NR (5.1%) | ASA: 170, NR (1.5%) Clopidogrel: 28, NR (0.3%) Ticagrelor: 4486, N (40%) Prasugrel: 608, NR (5.4%) | 7877 (70%) | 7992 (71%) | 276 ± 244 | 290 ± 270 | NR | NR |

| Bloom et al. (2021)7 | Retrospective | Australia | 2746 | 1373 (50.0%) | 1373 (50.0%) | 63.0 ± 12.4 | 63.2 ± 12.7 | ASA: 1327, NR (96.6%) Ticagrelor: 944, NR (68.8%) | ASA: 1326, NR (96.6%) Ticagrelor: 975, NR (70.9%) | 1099 (80.0%) | 1081 (78.7%) | 48 ± 23 | 64 ± 47 | 4000 + 1000 IU/h in ambulance | 4000 IU |

| McGinley et al. (2020)8 | Retrospective | Scotland | 1000 | 437 (43.7%) | 563 (56.3%) | 63.7 ± NR | 63.7 ± NR | ASA: 437, NR (100%) Clopidogrel: 437, NR (100%) | ASA: NR Clopidogrel: NR | 304 (69.6%) | 390 (69.3%) | NR | NR | 5000 IU | 5000 IU |

| Karlsson et al. (2019)11 | Subanálisis de ensayo clínico aleatorizado | Sweden | 7144 | 2898 (40.6%) | 4246 (59.4%) | 66.0 ± 11.5 | 66.0 ± 11.6 | ASA: 2817, NR (97.2%), Clopidogrel: 1662, NR (57.4%), Ticagrelor: 731, NR (25.2%) Prasugrel: 243, NR (8.4%) | ASA: 3636, NR (85.6%) Clopidogrel: 2489, NR (58.6%) Ticagrelor: 578, NR (13.6%) Prasugrel: 338, NR (8%) | 2169 (74.8%) | 3177 (74.8%) | 185 (125–320) | 181 (118–327) | NR | NR |

| Giralt et al. (2015)9 | Retrospective | Spain | 1326 | 758 (57.2%) | 568 (42.8%) | 61.3 ± 12.8 | 63.4 ± 12.8 | ASA: 744, NR (98.2%) Clopidogrel: 742, NR (97.9%) | ASA: 531, NR (93.5%) Clopidogrel: 503, NR (88.6%) | 618 (81.5%) | 434 (76.4%) | 107 (86–133) | 105 (83–140) | 5000 IU | 5000 IU |

| Zijlstra et al. (2002)12 | Retrospective | The Netherlands | 1702 | 860 (50.5%) | 842 (49.5%) | 59.0 ± 11.0 | 61.0 ± 11.0 | ASA: 860, NR (100%) | ASA: 842, NR (100%) | 696 (80.9%) | 665 (79.0%) | 81 ± 43 | 26 ± 39 | NR | NR |

|

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; IU, international units; NR, not reported; UFH, unfractionated heparin. |

|||||||||||||||

The aim of this study is to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis of existing studies on UFH pretreatment in the context of primary angioplasty as a reperfusion treatment for STEMI in terms of TIMI (Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction) grade 2-3 flow at the start of the procedure and early 30-day in-hospital mortality.

The meta-analysis follows PRISMA guidelines to ensure transparency and quality (table 2 of the supplementary data).

Table 2. Events from the studies

| Study | n | n (%) | Open artery: TIMI grade 2-3 flow | Major bleeding | 30-day mortality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | UFH | Non-UFH | ||

| Fabris et al. (2022)10 | 537 | 237 (44.1%) | 300 (55.9%) | 113 (47.7%) | 87 (29.0%) | 5 (2.1%) | 6 (2.0%) | 23 (9.7%) | 28 (9.3%) |

| Emilsson et al. (2022)6 | 22 376 | 11 188 (50.0%) | 11 188 (50.0%) | 4233 (37.8%) | 3263 (29.2%) | 199 (17.8%) | 199 (17.8%) | 313 (2.8%) | 395 (3.5%) |

| Bloom et al. (2021)7 | 2746 | 1373 (50.0%) | 1373 (50.0%) | 178 (13.0%) | 128 (9.3%) | 19 (1.4%) | 26 (1.9%) | 41 (3.0%) | 48 (3.5%) |

| McGinley et al. (2020)8 | 1000 | 437 (43.7%) | 563 (56.3%) | 111 (25.4%) | 136 (24.2%) | 6 (1.4%) | 5 (0.9%) | 11 (2.5%) | 47 (8.3%) |

| Karlsson et al. (2019)11 | 7144 | 2898 (40.6%) | 4246 (59.4%) | 1075 (37.1%) | 1204 (28.3%) | 47 (1.6%) | 92 (2.2%) | 76 (2.6%) | 131 (3.1%) |

| Giralt et al. (2015)9 | 1326 | 758 (57.2%) | 568 (42.8%) | 229 (30.2%) | 120 (21.1%) | 9 (1.2%) | 6 (1.1%) | NR | NR |

| Zijlstra et al. (2002)12 | 1702 | 860 (50.5%) | 842 (49.5%) | 263 (30.6%) | 168 (20.0%) | 43 (5.0%) | 59 (7.0%) | 26 (3.0%) | 24 (2.9%) |

| Total | 36 831 | 17 751 (48.0%) | 19 080 (51.9%) | 6202 (31.6%) | 5106 (23.0%) | 328 (4.3%) | 393 (4.7%) | 490 (3.9%) | 673 (5.1%) |

|

NR, not reported; TIMI: Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction; UFH, unfractionated heparin. |

|||||||||

METHODS

Literature search

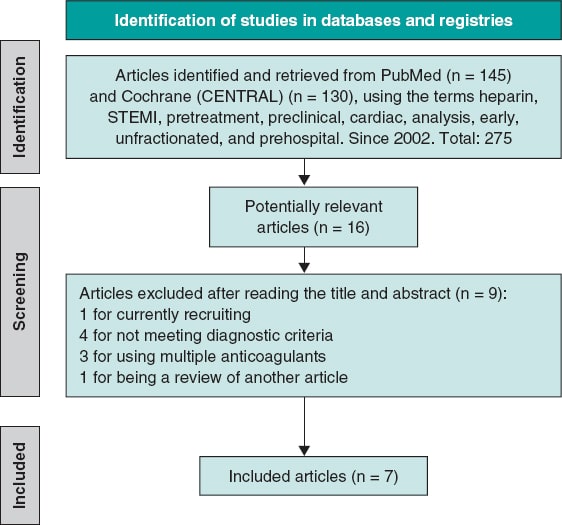

We conducted a systematic search of scientific literature across Medline-PubMed and the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) from May through September 2024. We accessed several observational studies and clinical trials comparing UFH pretreatment in the ambulance vs no pretreatment in patients diagnosed with STEMI treated with primary angioplasty. A lower date limit was set to 2002, and no language restrictions were applied. Studies were selected if they included information on initial TIMI grade flow, 30-day early mortality, and major bleeding complications. In the article by Emilsson et al.6 data from the propensity score cohort, which provides better adjustment, were used, and the same population was used in the study by Bloom et al.7. The references of the selected studies were analyzed to obtain additional articles via cross-referencing. Both the search and article selection methodology are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the literature search. STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

The PRISMA guidelines were followed (table 2 of the supplementary data), and the meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420250655362).

Inclusion criteria

We included observational, retrospective, and clinical trials analyzing the use of UFH as pretreatment in patients diagnosed with STEMI, administered at the first medical contact, in the ambulance or at a non-PCI-capable center prior to arrival at the destination hospital where the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) would be performed along with a control group of patients without UFH pretreatment. Moreover, studies had to provide information on initial TIMI grade flow, the 30-day mortality rate, and major bleeding complications. Only studies with a population of at least 500 individuals were included.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded repeated series from the same group, studies prior to 2002, those on pretreatment with anticoagulants other than UFH, studies without a control comparator group, or those that included patients diagnosed with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome, angina, or another cardiac event different from STEMI. Studies with less than 500 individuals were also excluded.

Selection of publications

The article search was conducted across Medline-PubMed and CENTRAL databases using the following terms: “preclinical,” “cardiac,” “heparin,” “analysis, early,” “unfractionated,” “STEMI,” “prehospital,” and “pretreatment.” A total of 275 relevant articles were identified, from which, after initial exclusion based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 16 were selected, and 7 finally remained6-12 (6 of them conducted in European populations and 1 in Australia.7) All were observational and retrospective studies, except for the one conducted by Karlsson et al.11, which is a subanalysis of a randomized clinical trial.

Primary and secondary endpoints

The primary endpoint was to analyze the association of UFH pretreatment with the presence of initial TIMI grade 2-3 flow in the infarct-related artery on diagnostic coronary angiography, prior to the start of PCI, in patients for whom PCI was indicated. The secondary endpoints were to analyze the association of UFH pretreatment with 30-day mortality in STEMI patients with an indication for PCI, and the presence of major bleeding complications13 (clinically significant bleeding events, such as bleeding requiring medical intervention or blood transfusion, or resulting in a significant hemoglobin decrease).

Data collection and management

Abstracts and methods sections of selected publications were systematically reviewed to ensure they met the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Measures were taken to avoid duplication of articles.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias in the studies included in the meta-analysis was assessed using a combination of robust statistical approaches and widely recognized visual methods. The Harbord test (table 3 of the supplementary data), specifically designed to detect publication bias in meta-analyses reporting risk ratios (RR), was used. Additionally, funnel plots were analyzed, allowing a visual assessment of asymmetry in the distribution of study effects. The funnel plots for each variable are included in figures 1-3 of the supplementary data.

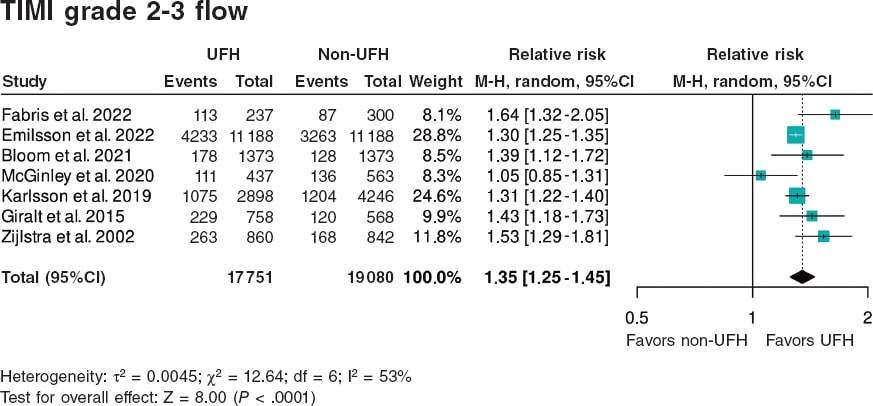

Figura 2. Forest plot of the prevalence of TIMI grade 2-3 flow. References cited in this figure: Fabris et al.10, Emilsson et. al.6, Bloom et al.7, McGinley et al.8, Karlsson et al.11, Giralt et al.9, and Zijlstra et al.12. 95%C, 95% confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel’s method; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

In this meta-analysis, the variables of interest include TIMI grade 2-3 flow, 30-day mortality, and major bleeding. Furthermore, their potential bias was analyzed using the above-mentioned statistical procedures.

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis, version 4.2.1 of R was used, using the metabin function from the meta package to synthesize the results of studies comparing UFH pretreatment vs UFH administered in the cath lab. Binary event data and totals for each group were analyzed using the RR model, with the inverse variance method, which weights studies based on precision, giving more weight to those with lower variance. A forest plot was generated using a random-effects model; the graph shows point estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for each individual study, along with an overall RR estimate. The graph design followed the RevMan format, with customized labels indicating the groups of interest (UFH and non-UFH) and direction of effects (favors UFH and favors non-UFH), improving clinical interpretation. Heterogeneity analysis included calculation of the I2 value, which quantifies the proportion of variability among studies not attributable to chance, due to observed heterogeneity. As indicated by the τ2 value from the Harbord test analysis (table 3 of the supplementary data), the random-effects model is most appropriate in this situation.

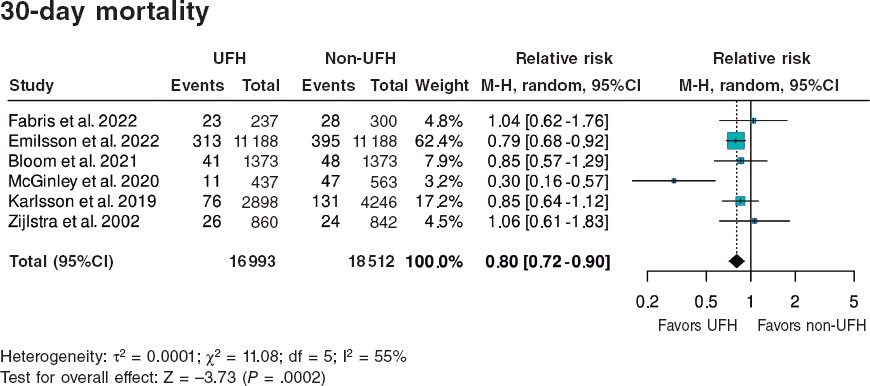

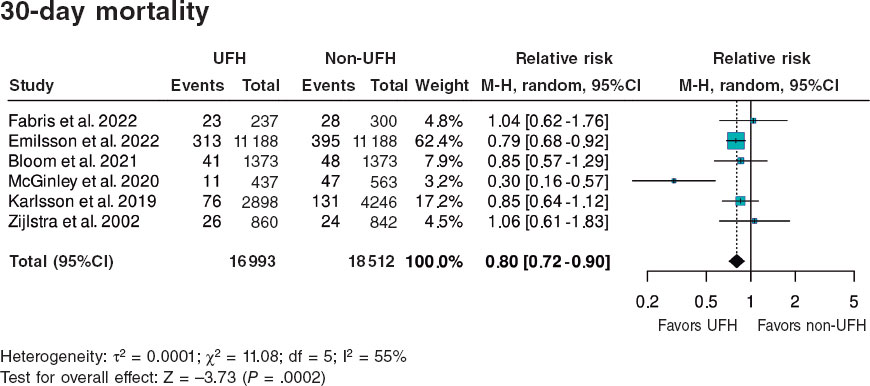

Figure 3. Forest plot of the prevalence of 30-day mortality. References cited in this figure: Fabris et al.,10 Emilsson et al.,6 Bloom et al.,7 McGinley et al.,8 Karlsson et al.,11 Giralt et al.,9 and Zijlstra et al.12. 95%C, 95% confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel’s method; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

RESULTS

A total of 36 831 patients were included, of whom 17 751 (48.2%) received pretreatment with UFH and 19 080 (51.8%) did not, the latter representing the control group for comparison. Of note, data from the article by Emilsson et al.6 were obtained from the propensity score-matched cohort, which provides better adjustment; therefore, the study population was 22 376 rather than 41 631 patients. Additionally, this adjusted cohort was used in the study by Bloom et al.7 with 2746 instead of 4720 patients. The data shown in table 1 correspond to the propensity score-matched cohort and include a summary of the demographics and characteristics of each study. A substantial portion of the population was male (70–80% of the total), with mean ages ranging from 60 to 67 years. Only 5 of the 7 studies reported the UFH dose, which ranged from 4000 to 5000 IU.

Primary endpoint

A total of 6202 (31.6%) patients pretreated with UFH achieved TIMI grade 2-3 flow vs 5106 (23.0%) from the non-pretreated group (table 2).

The meta-analysis of data from the 7 studies6-12 demonstrated a significant increase in the likelihood of TIMI grade 2-3 flow, with a hazard ratio (HR) of 1.35 (95%CI, 1.25–1.45; P < .0001) (figure 2). Although all studies showed statistically significant differences, except for the one by McGinley et al.8, heterogeneity in the magnitude of association was high (I2 = 53%).

Secondary endpoints

A total of 490 (3.9%) patients pretreated with UFH died within 30 days vs 673 (5.1%) from the non-pretreated group (table 2). The meta-analysis of data from the 7 included studies6-12 showed a reduction in 30-day mortality in patients who received pretreatment with UFH (HR, 0.80; 95%CI, 0.72–0.90; P = .0002) vs those who did not. Two studies showed a significantly lower mortality rate in the UFH group individually, including the one with the largest sample size6 (65.8% of patients included in the meta-analysis). Heterogeneity in the magnitude of association was high (I2 = 55%) (figure 3).

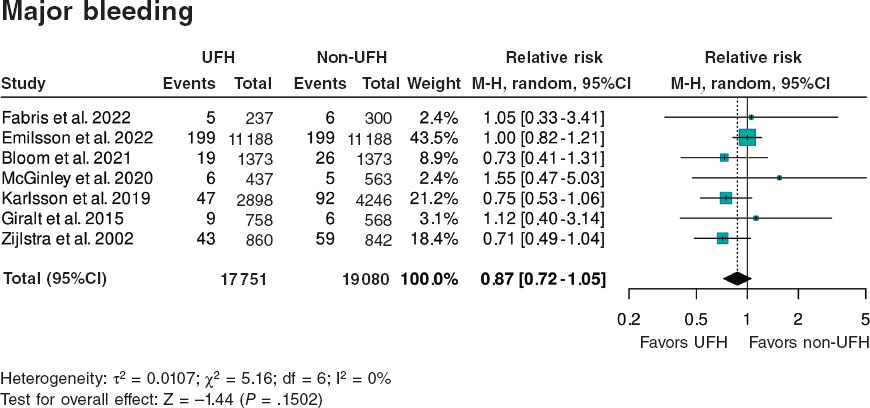

Regarding the association between UFH pretreatment and the rate of hemorrhagic complications, there were no significant associations in the meta-analysis of the 7 studies6-12 (HR, 0.87; 95%CI, 0.72–1.05; P = .1502). None of the studies showed a significant association, either beneficial or harmful, regarding bleeding complications. Heterogeneity among the studies was low (I2 = 0%) (figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot of the prevalence of major bleeding. References cited in this figure: Fabris et al.,10 Emilsson et al.,6 Bloom et al.,7 McGinley et al.,8 Karlsson et al.,11 Giralt et al.,9 and Zijlstra et al.12. 95%C, 95% confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel’s method; UFH, unfractionated heparin.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis demonstrates that for STEMI patients, administering UFH as pretreatment at the point of first medical contact is more beneficial than doing so at the PCI-capable center.

The observed benefit consists of a higher percentage of initial TIMI grade 2-3 flow (absolute increase of 8.6% and relative increase od 37.4%) and a lower 30-day mortality rate (absolute reduction of 1.2% and relative reduction of 23.5%). While most studies individually indicated a benefit of UFH pretreatment for open arteries, only 2 of the 7 studies primarily supported a mortality benefit. In terms of safety, pretreatment at first medical contact had a neutral effect on the risk of bleeding complications, and results were homogeneous across all 7 studies.

A recently published meta-analysis of 14 studies14 with different inclusion criteria and endpoints, incorporated studies on UFH and on a mix of other anticoagulants, such as low molecular weight heparin (enoxaparin), bivalirudin, and fondaparinux, along with additional events like cardiogenic shock, in-hospital mortality, and 1-year mortality. Both analyses showed consistent results on the benefit of pretreatment on open artery rates and early mortality, although they differed in the rate of bleeding complication. The referenced meta-analysis14 found a beneficial association between pretreatment with UFH or fractionated heparin in the reduction of bleeding complications. Moreover, the meta-analysis also analyzed the impact of pretreatment on the percentage of patients with cardiogenic shock, showing a positive association between pretreatment with UFH or fractionated heparin and this outcome. Of note, the heterogeneity in design, timing, and concomitant antiplatelet therapy among the studies included in the 2 meta-analyses. Notably, a small observational study conducted in Spain reported benefits from UFH pretreatment.15

Arguments for and against UFH pretreatment in STEMI

UFH is inexpensive, accessible, administered intravenously, and widely used in health care centers and ambulances. UFH is a necessary drug to prevent arterial and catheter thrombosis during PCI.

Beyond the potentially beneficial effects on open artery rates demonstrated in the meta-analysis, the use of UFH as pretreatment at the first medical contact does not seem to influence PCI per se. The rate of arterial puncture-related complications in anticoagulated patients is low when radial access is used; according to recent studies on the STEMI Code in Spain, 90% of angioplasties in STEMI patients are performed via radial access.4,5 There is still no information available on the potential impact of pretreatment on thrombus burden, no-reflow, ST-segment resolution, or infarct size, and no current studies have been designed to address these specific issues3 (table 4 of the supplementary data).

Clinical practice guidelines do not make definitive recommendations either due to the absence of adequately randomized trials evaluating the value of UFH pretreatment—not because there is evidence of no effect.1,3

In some patients misdiagnosed with STEMI (eg, those with aortic syndrome, pericarditis, myocarditis, NSTEMI, transient ST-segment elevation, Takotsubo syndrome, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, thoracic or esophageal disease, or musculoskeletal chest pain), pretreatment with UFH and antiplatelets may be harmful.

Notably, recent studies on the STEMI Code in Spain4-5 report that in 16.6% of all STEMI Code activations, the diagnosis of STEMI could not be confirmed, and in 3.6% of cases, no angioplasty was performed.

These misdiagnoses were not analyzed in the included meta-analyses. The design of the studies, most of which were retrospective, complicates the identification of risks associated with UFH use in these contexts. Theoretically, UFH pretreatment might be more beneficial in patients with recent thrombus formation, shorter times from symptom onset to first medical contact, and longer transfers to the PCI-capable center. However, in this meta-analysis, the review of study characteristics does not allow conclusions in this regard. There was no evident relationship between time metrics and the use of UFH pretreatment and the rates of open arteries or short-term mortality.

Need for randomized clinical trials

Clinical practice guidelines have become key reference documents for organizing health care delivery.1,2 These guidelines, developed by international experts who thoroughly review the scientific evidence to support their recommendations, are not always implemented in the routine clinical practice. One example, relevant to our field, is the use of antiplatelet pretreatment at the first medical contact. One year after the publication of the European Society of Cardiology guidelines on the management of acute coronary syndrome,1 which assigned a class IIb recommendation and level B evidence to dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in STEMI, nearly all hospitals in Spain continued to administer DAPT at the first medical contact (table 1 of the supplementary data).

The current recommendation against antiplatelet pretreatment, similarly to the indication on pretreatment with UFH, is based on the absence of evidence demonstrating a benefit from DAPT and concerns on the potential bleeding risk associated with the use of long half-life antiplatelet agents in patients who may require emergency revascularization surgery.16-18 However, the need for emergency surgery is extremely rare in STEMI cases. Implementation of the clinical practice guidelines and reducing pretreatment to a single antiplatelet agent has been adopted in other European countries with preliminary positive results (EuroPCR 2024 presentation).19 In countries such as Denmark and Germany, and certain regions of Italy, STEMI care protocols include the administration of a single antiplatelet agent (acetylsalicylic acid) along with UFH.20 Despite the absence of a clear recommendation regarding UFH in the guidelines, it can be inferred that protocol developers trust in the theoretically beneficial effect of UFH, complementing antiplatelet therapy at the time of the first medical contact.

Study limitations

This study has inherent limitations related to its design. Observational studies, especially retrospective ones, are susceptible to various biases, including selection and confounding, as well as uncontrolled factors that may affect internal validity. However, several measures were taken to mitigate these biases and provide a robust interpretation of the findings, including a detailed sensitivity analysis to assess result consistency. Moreover, heterogeneity was explored using the Harbord test, which yielded high p-values for publication bias, indicating no significant evidence of such bias influencing our results. Despite this, heterogeneity remains an inherent challenge in meta-analyses that include observational studies with varying designs and quality. This variability was documented using measures such as τ2 and considered in interpreting the findings.

Despite these limitations, the results remain valuable and should be interpreted with caution.

Another limitation is the heterogeneity in the number of patients included in the selected studies, the times for care and transfer, the doses of UFH administered, the definition of hemorrhagic complications, and the concomitant antiplatelet regimens used, all of which may have introduced bias.

CONCLUSIONS

The meta-analysis of retrospective studies and one clinical trial shows that pretreatment with UFH in patients with STEMI undergoing a primary angioplasty is associated with an increase in the initial TIMI grade 2-3 flow and a lower early mortality rate (figure 5).

Figura 5. Effect of unfractionated heparin pretreatment in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Forest plot of the prevalence of TIMI grade 2-3 flow. References cited in this figure: Fabris et al.10, Emilsson et al.6, Bloom et al.7, McGinley et al.8, Karlsson et al.11, Giralt et al.9, and Zijlstra et al.12. 95% CI: 95% confidence interval, M-H: Mantel-Haenszel’s method, UFH: unfractionated heparin.

Specifically designed clinical trials are needed to establish the impact of early UFH administration, and current clinical practice guidelines should provide clearer recommendations on the optimal timing of UFH pretreatment in STEMI patients.

FUNDING

This work was funded by CIBERCV CB16/11/00385.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Ethical considerations are not applicable to a meta-analysis, as no direct clinical data from individuals are collected and therefore ethics committee evaluation is deemed unnecessary. A subgroup analysis by sex was not performed because it would result in a loss of statistical power, and both women and men were represented. There is no prior evidence or data suggesting that men and women respond differently to IV heparin anticoagulant treatment.

STATEMENT ON THE USE OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Artificial intelligence was not used.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M. Roldán Medina and A. Riquelme Pérez equally contributed to various phases of the study: study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. Additionally, M. Roldán Medina contributed to drafting the original manuscript and editing and reviewing the final version, while A. Riquelme López was responsible for the final revision of the article.

R. López-Palop and P. Carrillo contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation, and to the final text review and editing. J. Lacunza participated in data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. R. Valdesuso contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation.

J. García de Lara was involved in data acquisition, analysis, interpretation, and final text review and editing. J. Hurtado-Martínez contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. J.M. Durán contributed to data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. E. Pinar-Bermúdez participated in data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. J.R. Gimeno and D. Pascual-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank all colleagues from the Cardiology Department at Hospital Virgen de la Arrixaca, IMIB, and Universidad de Murcia whose collaboration made this study possible.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- The early administration of unfractionated heparin (UFH) in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is controversial. Current clinical practice guidelines leave the timing of its administration before primary angioplasty to the physician’s discretion and do not provide clear recommendations on UFH pretreatment in STEMI patients prior to their arrival at the PCI-capable center.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- Our meta-analysis and systematic review of studies on the safety and efficacy profile of UFH pretreatment in STEMI patients, compared with control patients who did not receive such pretreatment, demonstrates that pretreatment with UFH was associated with an increased TIMI grade 2-3 flow, a lower 30-day mortality rate, and fewer major bleeding events.

REFERENCES

1. Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2024;13:55-161. Erratum in:Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2024;13:455

2. Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Sripal Bangalore, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Coronary Artery Revascularization.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:197-215.

3. Collet J, Zeitouni M. Heparin pretreatment in STEMI:is earlier always better?EuroIntervention. 2022;18:697-699.

4. Rodríguez-Leor O, Cid-Álvarez AB, Moreno R, et al. Regional differences in STEMI care in Spain. Data from the ACI-SEC Infarction Code Registry. REC Interv Cardiol. 2023;5:118-128.

5. Rodríguez-Leor O, Cid-Álvarez AB, Pérez de Prado A, et al. Analysis of the management of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in Spain. Results from the ACI-SEC Infarction Code Registry. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2022;75:669-680.

6. Emilsson O, Bergman S, Mohammad M, et al. Pretreatment with heparin in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:a report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR). EuroIntervention. 2022;18:709-718.

7. Bloom J, Andrew E, Nehme Z, et al. Pre-hospital heparin use for ST-elevation myocardial infarction is safe and improves angiographic outcomes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021;10:1140-1147.

8. McGinley C, Mordi I, Kell P, et al. Prehospital Administration of Unfractionated Heparin in ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction Is Associated With Improved Long-Term Survival. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020;76:159-163.

9. Giralt T, Carrillo X, Rodriguez-Leor O, et al. Time-dependent effects of unfractionated heparin in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2015;198:70,-74.

10. Fabris E, Menzio S, Gregorio C, et al. Effect of prehospital treatment in STEMI patients undergoing primary PCI. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;99:1500-1508.

11. Karlsson S, Andell P, Mohammad M, et al. Editor's Choice —Heparin pre-treatment in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and the risk of intracoronary thrombus and total vessel occlusion. Insights from the TASTE trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:15-23.

12. Zijlstra F, Ernst N, de BoerMJ, et al. Influence of prehospital administration of aspirin and heparin on initial patency of the infarct-related artery in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1733-1737.

13. Mehran R, Rao S, Bhatt D, et al. Standardized bleeding definitions for cardiovascular clinical trials:a consensus report from the Bleeding Academic Research Consortium. Circulation. 2011;123:2736-2747.

14. Costa G, Resende B, Oliveiros B, Gonçalves L, Teixeira R. Heparin pretreatment in ST segment elevation myocardial infarction:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Coron Artery Dis. 2025;36:28-38.

15. Ariza A, Ferreiro JL, Sánchez-Salado JC, Lorente V, Gómez-Hospital JA, Cequier A. Early Anticoagulation May Improve Preprocedural Patency of the Infarct-related Artery in Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2013;66:148-150.

16. Koul S, Smith J, Götberg M, et al. No Benefit of Ticagrelor Pretreatment Compared With Treatment During Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Undergoing Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11:e005528.

17. Russo RG, Wikler D, Rahimi K, Danaei G. Self-Administration of Aspirin After Chest Pain for the Prevention of Premature Cardiovascular Mortality in the United States:A Population-Based Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024;13:e032778.

18. Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45 852 patients with acute myocardial infarction:randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1607-1621.

19. Siller J, Angiolillo D, De Luca L, Rymer J, Thim T, Zeymer U. Real-world practice adoption of latest guidelines for the acute management of ACS patients. En:Paris 2024. EuroPCR Course 2024. 35th edition;2024 May 21-24;Paris, France. Available at:https://www.pcronline.com/Courses/EuroPCR. Consulted 1 Mar 2025.

20. De Luca L, Maggioni A, Cavallini C, et al. Clinical profile and management of patients with acute myocardial infarction admitted to cardiac care units:The EYESHOT-2 registry. Int J Cardiol. 2025;418:132601.