It comes as no surprise that the progression of medical training would eventually take a leap into the digital world where we would be able to access information without leaving our working place or the comfort of our homes. Our specialty, interventional cardiology, predominantly visual, has always benefited from the most advanced technology regarding communication. Actually, we have been doing this for years, even in our country: by the mid-1980s, the Madrid Interventional Course (MIC) organized by Dr. J.L. Delcán and Dr. E. García, was already broadcasting live cases via satellite to analyze and discuss new insights with larger audiences compared to those that can fit in a room. These days, live cases are an essential part of the meetings held in our setting (whether international like the ones organized by EuroPCR and TCT or national like the ones held by the Società Italiana di Cardiologia Interventistica [GISE] and the Interventional Cardiology Association of the Spanish Society of Cardiology [ACI-SEC])3. These cases are discussed remotely by panels of experts with a growing interaction with in-person and remote attendees thanks to specific computer tools and social media. But it is not only the broadcast of live cases which benefit from these advances. We have had access to information on late breaking clinical trials through the Internet many times even before in-person meeting where these trials are often presented. Also, we have had access to the recordings of many simultaneous sessions we couldn’t attend in-person but can review later when we have the time.

The situation of the pandemic caused by the new SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has accelerated this cross over to virtual meetings due to the impossibility of travelling to places and holding large in-person meetings.1 The main in-person cardiology meetings scheduled for 2020 have been suspended or turned into virtual meetings. The two largest international meetings already mentioned, EuroPCR and TCT, have become virtual meetings. Also, mass meetings like the ones held by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association or the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) have followed in the footsteps of this digital transition. Our sister societies, the Italian GISE and the Portuguese Associação Portuguesa de Intervenção Cardiovascular (APIC) have done the same thing. But, when these restrictions are lifted, will in-person activities like large face-to-face congresses and meetings be gone for good? Let us look at the pros and the cons of virtual and in-person meetings2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Pros of virtual meetings compared to face-to-face meetings.

These are the basic strengths of virtual meetings:

-

- The speed at which these meetings are prepared is much faster compared to in-person meetings since there are many different tasks that the cardiology society does not need to do.

-

- Lower costs: it is obvious that reducing travel and accomodation expenses, renting fewer available spaces, etc. reduces the overall budget. A direct consequence of this is a lower impact on the environment thanks to lower mobility.

-

- Greater efficiency in the transmission of the message without time losses when going to the meeting or in-between sessions, possibility of increasing the capacity of the virtual rooms on demand and reviewing pre-recorded sessions on demand (even so, personal interaction will be gone).

-

- Better attendance control: computer tools facilitate the comprehensive registry of attendance to every session, time, origin, and interaction developed, etc., but not the quality. Although we cannot fully know to what extent these attendees’ profit from these face-to-face meetings (exams may be an option?) leaving a device connected to these activities is no guarantee either.

-

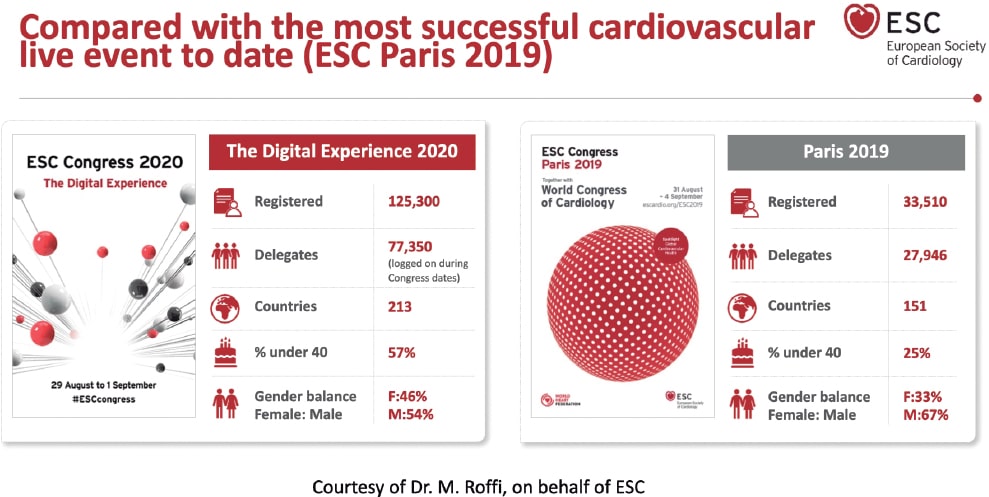

- Universal access brings meetings to larger audiences erasing geographical borders: in the fully virtual EuroPCR of 2020 there were over 15 000 registrations (compared to 11 200 registrations in the 2019 in-person edition).3 This phenomenon was even more evident in the ESC congress of 2020. This meeting still holds the registration record with 125 000 registrations from 213 different countries4 compared to the previous year (33 500 registrations).5 (Figure 2). Can these figures be compared? Probably not because registration to these virtual editions was free of charge.

-

- Adaptation to changing situations: this virtual format allows us to accommodate meetings to travel limitations or potentially infectious situations like the one posed by the current pandemic.

Figure 2. Registration comparison of the annual meetings held by the European Society of Cardiology back in 2019 and 2020.

The downsides of virtual meetings are:

-

- Dependency on technical factors: technical support systems are excellent, but still depend on variables like the Internet bandwidth, the quality of connectivity or the incompatibilities of presentations and videos. After 25 years of use of the DICOM standard for the communication and management of medical imaging we still have issues when we try to play video sequences in virtual meetings.

-

- To a great extent, the format of these sessions keeps the same structure as face-to-face meetings. The adaptation to the new virtual environment has been more cosmetic than a true reality with the implementation of several technological advances to mimic the in-person experience (avatars, virtual common rooms, chats to replace direct communication). However, fully developed specific methods of communication have not been implemented yet.

-

- More difficult personal interaction: asynchronous communication and other virtual borders like lack of types of nonverbal communication (beyond emoticons) complicate connectivity among speakers, moderators, and audience. Speakers feel some kind of «digital loneliness» because they don’t receive any feedback from the audience. In turn, the audience experience “digital fatigue” and they can’t remain focused on anything for more than 30 minutes. New systems to encourage audience participation are desperately needed, particularly in the virtual format.

-

- Agendas, time zones, and time devoted to work: in these virtual meetings it is not unusual to find conflicting time schedules since participants come from all across the world. It is not unusual either that these time schedules invade our spare time or affect our working day. The proliferation of these activities is associated with digital overload that has sometimes been referred to as «death-by-webinars»

-

- Program sustainability: although our political representatives can’t wait to stop the private sector from funding our medical training programs, the truth is that this is crucial if we want to develop this kind of activity. If some of the activities that used to take place at face-to-face meetings are gone, will support still be the same? Isn’t it more profitable to conduct sponsored meetings and not independent activities?

Those of us who have been trained in the “traditional” meeting environment have a hard time thinking that they can be totally replaced by the virtual format. Here are some of the reasons why:

-

- Attending a scientific meeting is a comprehensive experience that includes training as well as other activities: research coordination meetings, building up professional relations, consultancy and counseling, etc. It is almost impossible to conduct these activities outside the context of a scientific meeting.

-

- In this sense, attending a face-to-face meeting is time-bound. It is not always easy to disassociate attendance to these meetings from working or face-to-face obligations (especially when the meeting is held in our own town), but it is actually easier compared to virtual meetings. In our setting there are work permits that can be issued to attend training sessions: could this be applicable to virtual meetings particularly with the current extended time schedules of such events?6

-

- Most of the advantages seen in the broadcast of contents have long been part of face-to-face meetings. Consequently, most sessions are recorded for immediate broadcast and further reproduction. The same thing happens with in-person and remote audience interaction where the use of social media has proven very useful.

Will the digital gap between the analogical and the digital world, between immigrants and digital natives, between boomers and millennials grow? I don’t think so. Their coexistence will prevail and bring us the best of both worlds: hybrid meetings. If these two worlds were actually ever there…

FUNDING

No funding was received for this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

A. Pérez de Prado declared having received professional fees for his consultancy work or meetings held for iVascular, Boston Scientific, Terumo, BBraun, and Abbott totally unrelated to this article; he is the current president of the education and learning organization Fundación Epic.

REFERENCES

1. Alkhouli M, Coylewright M, Holmes DR. Will the COVID-19 Epidemic Reshape Cardiology? Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2020;6:217-220.

2. Sandars J, Correia R, Dankbaar M, et al. Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish. 2020. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1.

3. PCR e-Course 2020. Thanks to the 15,000+online learners. 2020. Available online:https://www.pcronline.com/Courses/PCR-e-Course. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

4. European Society of Cardiology. ESC Congress 2020 ? The Digital Experience. A record-breaking event:125,000 healthcare professionals from 213 countries. Available online:https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-%26-Events/ESC-Congress. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

5. European Society of Cardiology. Figures from ESC Congress ? Statistics from the world's largest cardiovascular congress. Participation 2015-2019. Available online:https://www.escardio.org/Congresses-&-Events/ESC-Congress/About-the-congress/Figures-from-ESC-Congress. Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

6. Margolis A, Balmer JT, Zimmerman A, López-Arredondo A. The Extended Congress:Reimagining scientific meetings after the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish. 2020. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000128.1.

Corresponding author: Servicio de Cardiología Intervencionista, Hospital Universitario de León, Altos de Nava s/n, 24008 León, Spain.

E-mail address: aperez@secardiologia.es (A. Pérez de Prado).