ABSTRACT

Introduction and objectives: According to the recommendations of the latest clinical practice guidelines, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) patients should undergo an invasive coronary angiography. However, the best moment to perform this coronary angiography has not been stablished yet. Our main objective was to see if performing an early angiography (within the first 24 h) in NSTEMI patients was associated with better prognosis compared to delayed angiography (beyond the first 24 h).

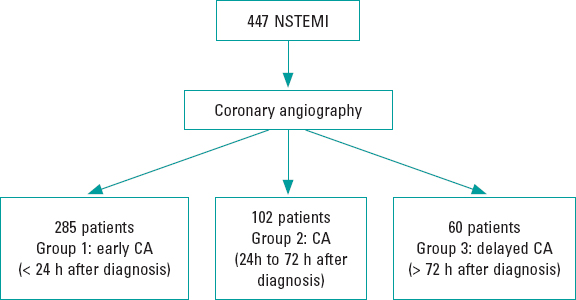

Methods: From January 2014 to June 2016, 447 consecutive patients were admitted to the acute cardiac care unit of a tertiary hospital with a diagnosis of NSTEMI. They all underwent catheterization. We classified them into 3 groups depending on the moment when the coronary angiography was performed (within the first 24 h after diagnosis, 24 h to 72 h later, and > 72 h after diagnosis).

Results: Coronary angiography was performed within the first 24 h in 285 patients (63.8%). There were no differences among the groups regarding gender, distribution of cardiovascular risk factors, past medical history of coronary disease or presence of other comorbidities. We found no differences among the 3 groups in variables with known prognostic impact. The cardiovascular events and 1-year mortality at follow-up were similar among the 3 groups.

Conclusions: In our study, in the whole spectrum of NSTEMI, early coronary angiography (within the first 24 h) did not show any clinical benefits regarding survival or fewer major adverse cardiovascular events.

Keywords: Acute coronary syndrome. GRACE score. Early angiography. Prognosis. Mortality.

RESUMEN

Introducción y objetivos: Las guías clínicas recomiendan la realización de una coronariografía en los pacientes con infarto agudo de miocardio sin elevación del segmento ST (IAMSEST). Sin embargo, no está claramente establecido el mejor momento para hacerla. Por ello, el objetivo del presente trabajo fue analizar si practicar un cateterismo precoz (durante las primeras 24 h) se relaciona con un mejor pronóstico, en comparación con hacerlo de manera diferida (más allá de las 24 h).

Métodos: De enero de 2014 a junio de 2016 ingresaron en la unidad de cuidados agudos cardiológicos de un hospital terciario 447 pacientes consecutivos con diagnóstico de IAMSEST a los que se hizo una coronariografía. Se clasificó de forma retrospectiva a los pacientes en 3 grupos en función del momento de realización del cateterismo: durante las primeras 24 h, entre las 24 y las 72 h tras el diagnóstico, y después de las primeras 72 h.

Resultados: El cateterismo se llevó a cabo en las primeras 24 h en 285 pacientes (63,8%). No se identificaron diferencias entre los grupos en cuanto a sexo, prevalencia de factores de riesgo cardiovascular ni presencia de comorbilidad. Tampoco se encontraron diferencias en las variables pronósticas analizadas ni en la mortalidad. En el seguimiento a los 12 meses, la incidencia de eventos cardiovasculares y la mortalidad fueron similares entre los grupos.

Conclusiones: En el presente estudio, la realización de una coronariografía precoz (en las primeras 24 h) a los pacientes ingresados por IAMSEST no mostró beneficio clínico en términos de supervivencia o reducción de eventos cardiovasculares.

Palabras clave: Síndrome coronario agudo. GRACE score. Cateterismo precoz. Pronóstico. Mortalidad.

Abbreviations: CA: coronary angiography. NSTEMI: non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction.

INTRODUCTION

Coronary angiography (CA) is a key step in treatment of patients with non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). CA reduces mortality and the rates of new cardiovascular adverse events compared to the conservative approach.1,2 Therefore, the current European clinical practice guidelines on the management of NSTEMI recommend an invasive strategy to treat these patients.1

The appropriate time to perform the CA in NSTEMI patients is still under discussion. Early CA (within the first 24 h after diagnosis) is still recommended in patients with high-risk NSTEMI defined as a GRACE score > 140. However, the potential benefit of this approach has not been completely established yet.3

The objective of our study was to assess the prognostic impact of an early CA (within the first 24 h after diagnosis) in patients NSTEMI compared to a delayed CA strategy (after 24 h).

METHODS

This is a retrospective, observational cohort study. From January 2014 to June 2016, data from 447 patients with NSTEMI admitted to a tertiary referral hospital who underwent an invasive coronary angiography were consecutively collected.

NSTEMI was defined according to the guidelines and all patients were treated following the recommendations established by these guidelines.1

Data from all the cases were included prospectively in a continuous multipurpose database. The collection of data included detailed past clinical histories, physical examinations, pulse oximetry measures, 12-lead electrocardiograms, continuous electrocardiogram monitoring, blood tests, echocardiographies, and CAs. The Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) and Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress Adverse Outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines (CRUSADE) scores were calculated for each patient.1

Patients were classified into 3 groups according to the time to CA (figure 1): catheterization within the first 24 h after diagnosis (group 1, n = 285 patients), 24 h to 72 h later (group 2, n = 102 patients) and after 72 h (group 3, n = 60 patients). The decision on when to perform the CA was made by the treating physician in each case. After being discharged from the hospital, the 12-month follow-up of patients was performed in a dedicated clinic.

Figure 1. Flowchart. CA, coronary angiography; NSTEMI, non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarction.

The primary endpoints of our study were mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events (stroke, new acute coronary syndrome, new revascularization) during hospitalization and depending on the time to CA in patients with NSTEMI. The secondary endpoints were mortality and the rate of major cardiovascular events at the 1-year follow-up, and bleeding events according to the BARC criteria.4 We also analyzed the antiplatelet treatment prescribed at discharge and its correlation with MACE at follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range [IQR] when appropriate. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the variables normal distribution. Regarding quantitative variables, the groups were compared using the 2-tailed Student t test or the Mann-Whitney U test when necessary. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage, and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate. No variable had losses > 15%.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the potential impact of the CA timing on in-hospital mortality. The model included all variables that were statistically significant in the univariate analysis regarding mortality and time to CA. Adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated for each variable. Regarding the secondary endpoint of 1-year mortality, a Cox regression analysis was performed to assess any potential prognostic factors.

All tests were 2-tailed and the differences were considered statistically significant with P values < .05. The statistical analysis was performed using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics V 22.0.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the patient population. Patients in group 1 were younger (66.5 ± 13.5 years vs 71.1 ± 12.7 years in group 2, and 70.7 13.5) in group 3, P = .016). There were no gender differences among the groups (P = .565). The cardiovascular risk factors, previous coronary artery disease (P = .314), and presence of other comorbidities were similar among the groups (table 1).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics among the 3 study groups and antiplatelet therapy at discharge

| Group 1 (n = 285) | Group 2 (n = 102) | Group 3 (n = 60) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 66.5 (13.5) | 70.7 (13.5) | 71.1 (12.7) | .016 |

| Sex (male) | 78.9% | 80.2% | 73.3% | .565 |

| Diabetes | 34.9% | 37.6% | 35.0% | .880 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 63.4% | 54.5% | 55.9% | .195 |

| Hypertension | 71.1% | 71.3% | 73.3% | .942 |

| GRACE score | 157 (44.9) | 161 (45.7) | 170 (39.6) | .041 |

| CRUSADE score | 32.8 | 34.8 | 36.4 | .251 |

| GFR | 72 | 69.8 | 66 | .118 |

| Peak CK levels | 659.9 | 479.4 | 590 | .623 |

| LVEF at discharge | 49.6 | 54.2 | 52 | .229 |

| Killip class | .604 | |||

| I | 194 (71.3%) | 75 (72.7%) | 37 (62.7%) | |

| II | 32 (11.8%) | 15 (15.2%) | 9 (15.3%) | |

| III | 23 (8.5%) | 7 (7.1%) | 8 (13.6%) | |

| IV | 23 (8.5%) | 5 (5.1%) | 5 (8.5%) | |

| Mechanical ventilation | 29 (10.7%) | 6 (6.1%) | 5 (8.3%) | .636 |

| Number of vessels with severe stenosis | .488 | |||

| 1 | 133 (46.8%) | 45 (44.6%) | 23 (38.6%) | |

| 2 | 77 (27.1%) | 23 (22.8%) | 22 (36.7%) | |

| 3 | 68 (23.9%) | 29 (28.7%) | 14 (23.3%) | |

| Successful revascularization | 211 (89.8%) | 70 (92.1%) | 42 (91.3%) | .930 |

| Antiplatelet therapy at discharge | ||||

| Ticagrelor | 154 (54%) | 52 (50.9%) | 29 (48.3%) | .154 |

| Clopidogrel | 105 (36.8%) | 40 (39.2%) | 24 (40%) | .358 |

| Prasugrel | 26 (9.2%) | 10 (9.9%) | 7 (11.7%) | .469 |

|

CK, creatine kinase; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. Group 1: coronary angiography within the first 24 h after diagnosis; group 2: 24 h to 72 h later; group 3: coronary angiography > 72 h after diagnosis. |

||||

A CA was performed within the first 24 h in 285 patients (63.8%). Surprisingly, we noticed that the patients from group 1 showed lower GRACE scores [157.67 (44.9) points vs 170 (39.5) points in group 3, (P = .041)] and similar CRUSADE scores compared to the other 2 groups (P = .251).

There were no significant differences among the groups in the Killip class at admission (table 1). The left ventricular ejection fraction and the peak values of cardiac biomarkers were similar among the groups. The presence of multivessel disease was similarly in the 3 study groups (table 1). There were no significant differences in the primary endpoint among the 3 study groups (table 2). During hospitalization, strokes and bleeding events occurred similarly in the 3 groups (table 2). It is important to emphasize here the low rate of bleeding events (5 patients with BARC 2 and 2 patients with BARC 3 events in group 1, and 3 patients with BARC 2 and 2 patients with BARC 3 events in groups 2 and 3, with no fatal events). At the 1-year follow-up, cardiovascular adverse events and 1-year mortality were similar among the 3 groups (table 2).

Table 2. In-hospital and follow-up rate of adverse events and mortality (expressed as percentage) among the 3 groups

| Group 1 (n = 285) | Group 2 (n = 102) | Group 3 (n = 60) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital events | ||||

| Heart failure | 74 (25.9%) | 26 (25.4%) | 21 (36%) | .246 |

| Non-fatal AMI | 3 (1%) | 4 (3.9%) | 3 (6%) | .371 |

| Acute kidney injury | 47 (16.5%) | 18 (17.6%) | 15 (25%) | .334 |

| Stroke | 3 (1%) | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (3.3%) | .548 |

| Bleeding events | 20 (7%) | 6 (5.8%) | 6 (10%) | .213 |

| In-hospital mortality | 19 (6.6%) | 7 (6.8%) | 2 (3.4%) | .358 |

| Events at the 1-year follow-up | ||||

| Death | 17 (5.9%) | 5 (4.9%) | 5 (8.3%) | .114 |

| Stroke | 3 (1.05%) | 3 (2.9%) | 1 (1.6%) | .271 |

| Major bleeding | 7 (2.45%) | 6 (5.8%) | 4 (6.6%) | .427 |

| Myocardial infarction | 16 (5.6%) | 5 (4.9%) | 4 (6.6%) | .907 |

|

AMI, acute myocardial infarction. Group 1: coronary angiography within the first 24 h after diagnosis; group 2: 24 h to 72 h later; group 3: coronary angiography > 72 h after diagnosis. |

||||

Regarding medical treatment at discharge, a similar percentage of patients received clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor in the 3 study groups (table 1). In our cohort, antiplatelet therapy was not associated with differences in the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events and mortality at the 12-month follow-up.

The multivariate logistic regression analysis performed to predict mortality revealed that hypertension, Killip class IV at admission, left ventricular ejection fraction, and myocardial damage (defined as peak creatine kinase levels) were independently associated with higher in-hospital mortality rates. The time to CA was not an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality after the multivariate adjustment (table 3).

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression analysis to predict in-hospital mortality

| Variable | Odds ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| CA after 72 h | reference | |

| CA within the first 24 h | 0.98 (0.26-3.74) | .978 |

| CA 24 h to 72 h later | 1.33 (0.28-6.24) | .716 |

| Hypertension | 6.25 (1.09-33.3) | .04 |

| Age (per year) | 1.03 (0.98-1.08) | .292 |

| Successful revascularization | 0.51 (0.12-2.21) | .371 |

| Peak CK levels (per pg/mL) | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .010 |

| LVEF | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | < .001 |

| Killip class at admission | ||

| I | reference | .026 |

| II | 3.39 (0.98-11.75) | .054 |

| III | 3.24 (0.92-11.36) | .067 |

| IV | 15.34 (2.19-107.58) | .006 |

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CA, coronary angiography; CK, creatine kinase; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. |

||

Regarding 1-year mortality, the Cox regression analysis showed similar results. The time to CA was non-significant in the multivariate analysis. Hypertension, age, left ventricular ejection fraction, and Killip class at admission were independently associated with higher mortality rates at 1 year (table 4).

Table 4. Multivariate Cox regression analysis to predict 1-year mortality

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95%CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

| CA after 72 h | reference | |

| CA within the first 24 h | 0.96 (0.46-2.03) | .919 |

| CA 24 h to 72 h later | 0.82 (0.33-2.07) | .677 |

| Hypertension | 3.64 (1.30-10.3) | .014 |

| Age (per year) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | .022 |

| Successful revascularization | 0.94 (0.41-2.13) | .876 |

| Peak CK levels (per pg/mL) | 1.00 (1.00-1.01) | .198 |

| LVEF | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | < .001 |

| Killip class at admission | ||

| I | reference | |

| II | 2.83 (1.32-6.08) | .008 |

| III | 2.78 (1.27-6.09) | .010 |

| IV | 2.91 (0.83-10.2) | .096 |

|

95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CA, coronary angiography; CK, creatine kinase; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. |

||

DISCUSSION

Our study included a large cohort of 447 consecutive patients with NSTEMI that were retrospectively analyzed. Our results showed that early CAs (defined as a CA performed within the first 24 h after diagnosis) in NSTEMI patients did not improve the prognosis of this cohort of patients compared to delayed CAs. No differences were seen among the 3 groups regarding the time to CA in the in-hospital cardiovascular adverse event rate, mortality rate or at the 12-month follow-up either.

Early CA, within the first 24 h after diagnosis, is currently recommended by the clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with NSTEMI. However, this recommendation is based on the results of relatively old clinical trials and a meta-analysis.4-8 Several recent trials have explored the prognostic impact of the CA timing on NSTEMI patients in order to find stronger evidence in this clinical setting.9,10

The results of the TIMACS study (Timing of Intervention in Acute Coronary Syndromes) showed that an early CA was associated with a reduction in the composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction or refractory ischemia compared to a delayed CA strategy.11

A retrospective cohort study that included 19 704 propensity scorematched patients hospitalized with a first acute coronary syndrome conducted between January 1, 2005 and December 31, 2011 showed that the use of an early invasive treatment strategy was associated with a lower risk for cardiovascular mortality and re-hospitalization due to myocardial infarction compared to a conservative invasive approach.12 However, it is important to emphasize the retrospective nature of this study and the fact that patients were followed for 60 days only.

However, a meta-analysis that combined data from 83 229 patients did not show any significant differences regarding mortality, myocardial infarction or major bleeding events between the 2 strategies.13

Another meta-analysis that included 8 randomized controlled trials (n = 5324 patients) with a median follow-up of 180 days [180-360] and compared an early invasive group of NSTEMI patients to a delayed strategy showed that the early invasive strategy did not reduce mortality in all NSTEMI patients including high risk patients with GRACE score > 140 points.14

Similarly, a recent meta-analysis that combined the results of 10 clinical trials did not find any differences in mortality, myocardial infarction or major bleedings among NSTEMI patients based on the CA timing. Nevertheless, the early CA strategy was associated with less recurrent angina and shorter hospital stays.15

The LIPSIA-NSTEMI study randomized patients with NSTEMI to undergo CA within the first 2 h after randomization (immediate CA strategy), 10 h to 48 h after randomization (early CA), and the so-called “selectively invasive” arm, in which patients initially received medical treatment without showing any differences in the infarct size among the 3 study groups.16

A recent randomized controlled trial conducted by a Kofoed et al., the VERDICT trial, included a total of 2147 patients of which 1075 were allocated to very early invasive evaluation (within the first 12 h after diagnosis), and 1072 to receive standard invasive care (CA 61.6 h after randomization).17 The primary endpoint was a composite of all-cause mortality, nonfatal recurrent myocardial infarction, refractory myocardial ischemia-related hospital admission or heart failure-related hospital admission. In this trial, the very early invasive coronary evaluation strategy did not improve overall the long-term clinical outcome compared to the invasive strategy performed within 2 to 3 days in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. However, in patients with the highest risk, the very early invasive therapy improved long-term outcomes17 which is consistent with the results shown by the TIMACS trial.

Despite all these data, there is still controversy on what the best timing is to perform a CA in patients with NSTEMI.

An important limitation of previous studies is heterogeneity in the definition of early and late CA, and the differences seen in the primary endpoints.4-14 The lack of uniform criteria makes it difficult to compare the results. The definition of NSTEMI has changed over time. Thus, old clinical trials used a different criterion for the definition of NSTEMI and included different patients from those of current studies. We should try to identify what patients with the highest risk would benefit from an early invasive strategy. In this sense, previous studies did not use risk grading systems to classify patients. However, in our study we calculated the ischemic and bleeding risks of all patients. As our objective was to assess the potential benefit of an early invasive strategy among NSTEMI patients, the GRACE risk score was estimated in the entire study population. However, despite the high ischemic risk of our patients, no significant differences were found between the 2 strategies (early or delayed CA) regarding mortality or adverse events.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Although we included a large number of NSTEMI patients with a collection of high quality data, this is an observational, retrospective, single center study with the limitations of this type of study. Besides, the current clinical practice guidelines recommend the PRECISE-DAPT score to assess bleeding risk in this clinical setting. In our study bleeding risk at admission was classified according to CRUSADE score.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of our study show that the early CA strategy did not improve prognosis or reduce mortality in NSTEMI patients. However, larger studies are still needed to clarify which group of patients may benefit from early CA strategies.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None declared.

WHAT IS KNOWN ABOUT THE TOPIC?

- Early CA is recommended by the current clinical practice guidelines in patients with a high-risk suffering from non-ST-elevation acute myocardial infarctions.

- To this day, clinical trials and meta-analyses show contradictory results without clear prognostic differences between the early CA strategy and delayed catheterization.

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD?

- A large cohort of consecutive NSTEMI patients was retrospectively studied. We assessed in-hospital progression and cardiovascular events and mortality at the 1-year follow-up.

- The results of our study show that the early CA strategy did not imporive prognosis or reduced mortality in NSTEMI patients.

- No differences among the 3 groups were seen based on the CA timing regarding cardiovascular adverse events and mortality during the hospital stay or at the 12-month follow-up.

- No differences among the 3 groups were seen based on the CA timing regarding cardiovascular adverse events and mortality during the hospital stay and at the 12-month follow-up.

REFERENCES

1. Roffi M, Patrono C, Collet JP, et al. 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation:Task Force for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes in Patients Presenting Without Persistent ST-Segment Elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016;37:267-315.

2. Amsterdam EA, Wenger NK, Brindis RG, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes:executive summary:a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;130:2354-2394.

3. Reuter PG, Rouchy C, Cattan S, et al. Early invasive strategy in high-risk acute coronary syndrome without ST-segment elevation. The Sisca randomized trial. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:414-418.

4. Vranckx P, White HD, Huang Z, et al. Validation of BARC Bleeding Criteria in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes:The TRACER Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:2135-2144.

5. Montalescot G, Cayla G, Collet JP, et al. ABOARD Investigators. Immediate vs delayed intervention for acute coronary syndromes:a randomized clinical trial. JAMA.2009;302:947-954.

6. De Winter RJ, Windhausen F, Cornel JH, et al. Early invasive versus selectively invasive management for acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med.2005;353:1095-1104.

7. Hirsch A, Windhausen F, Tijssen JG, et al. Long-term outcome after an early invasive versus selective invasive treatment strategy in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome and elevated cardiac troponin T (the ICTUS trial):a follow-up study. Lancet.2007;369:827-835.

8. O'Donoghue M, Boden WE, Braunwald E, et al. Early invasive vs conservative treatment strategies in women and men with unstable angina and non- ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction:a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:71-80.

9. Badings EA, The SH, Dambrink JH, el al. Early or late intervention in high-risk non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes:results of the ELISA-3 trial. EuroIntervention.2013;9:54-61.

10. Milosevic A, Vasiljevic-Pokrajcic Z, Milasinovic D, et al. Immediate Versus Delayed Invasive Intervention for Non-STEMI Patients:The RIDDLE-NSTEMI Study. JACC Cardiovasc Interv.2016;9:541-549.

11. Mehta SR, Granger CB, Boden WE, et al. Early versus delayed invasive intervention in acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2165-2175.

12. Hansen KW, Sorensen R, Madsen M, et al. Effectiveness of an early versus a conservative invasive treatment strategy in acute coronary syndromes:a nationwide cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:737-746.

13. Navarese EP, Gurbel PA, Andreotti F, et al. Optimal timing of coronary invasive strategy in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes:a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:261-270.

14. Jobs A, Mehta SR, Montalescot G, et al. Optimal timing of an invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome:a meta-analysis of randomized trials. Lancet.2017;390:737-746.

15. Bonello l, Laine M, Puymirat E, et al. Timing of Coronary Invasive Strategy in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndromes and Clinical Outcomes:An Updated Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:2267-2276.

16. Thiele H, Rach J, Klein N, et al. Optimal timing of invasive angiography in stable non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction:the Leipzig Immediate versus early and late PercutaneouS coronary Intervention triAl in NSTEMI (LIPSIA-NSTEMI Trial). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2035-2043.

17. Kofoed KF, Kelbæk H, Hansen PR, et al. Early Versus Standard Care Invasive Examination and Treatment of Patients With Non-ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome. Circulation. 2018;138:2741-2750.

Corresponding author: Hospital Clínico Universitario San Carlos, Prof. Martín Lagos s/n, 28040 Madrid, Spain.

E-mail address: carlosferreraduran@gmail.com (C. Ferrera).