To the Editor,

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) is a misdiagnosed condition that has emerged as an important cause of acute coronary syndrome and sudden death, especially in women under 50. In these patients it is responsible for 30% of all the cases of such syndrome.1 However, only between 10% and 15% of all SCADs are diagnosed in male patients.

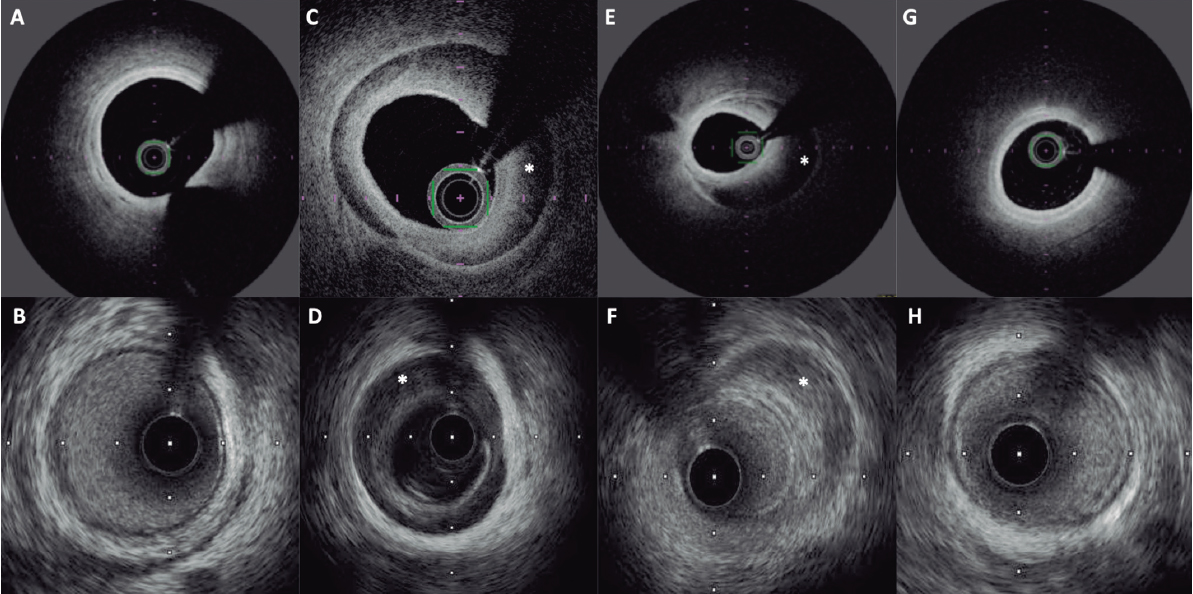

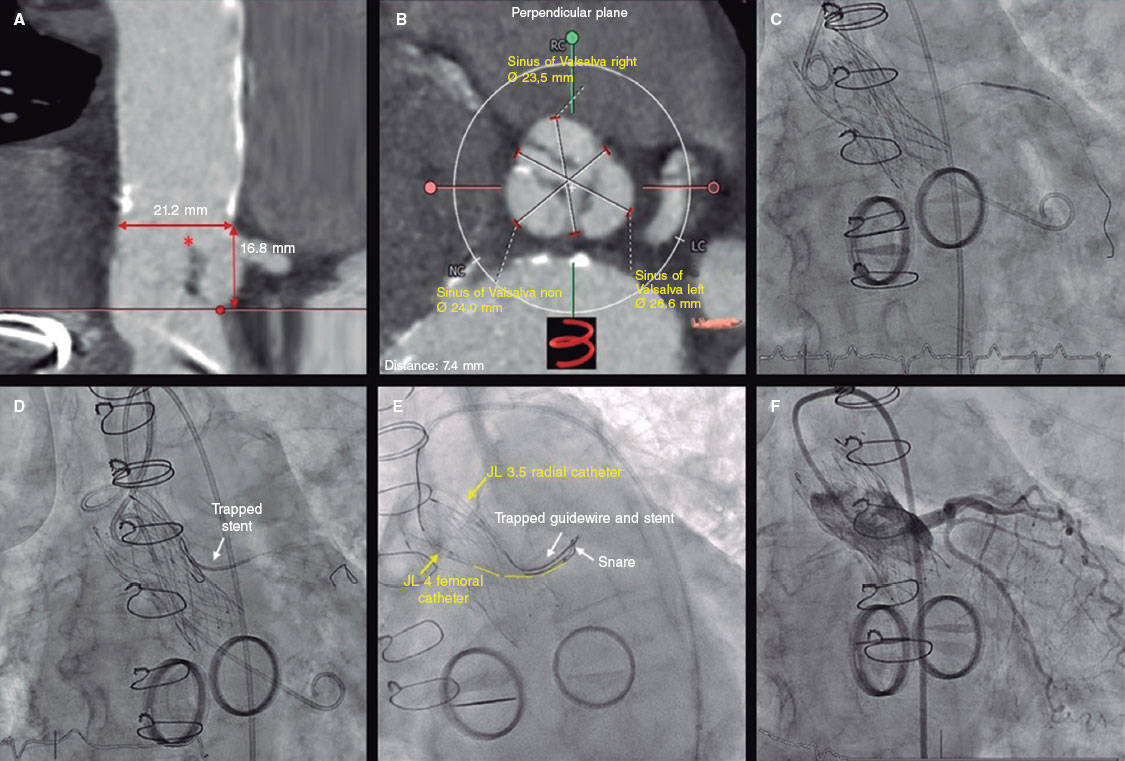

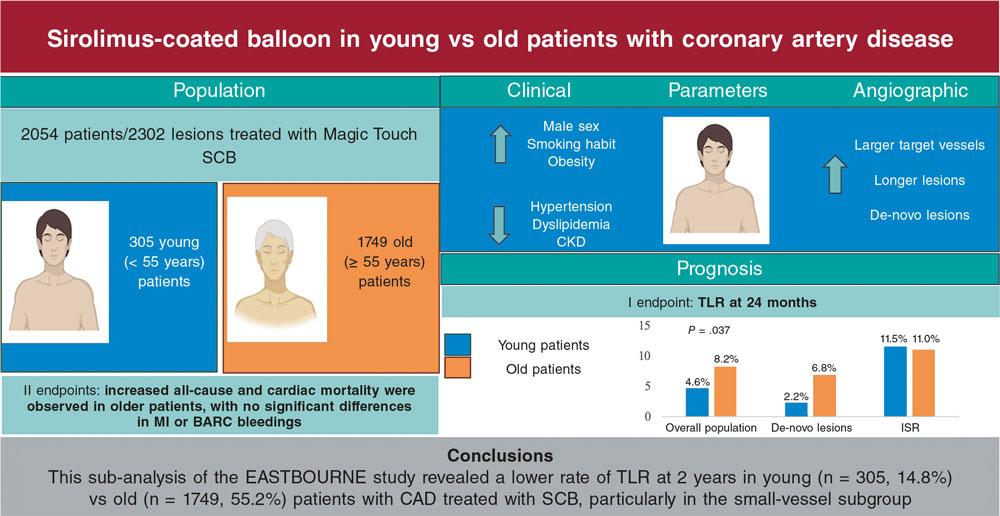

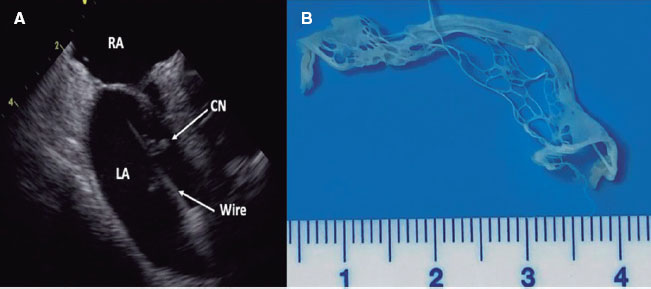

This is the case of a male patient with SCAD in a migraine crisis setting. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the proceeding and for the dissemination of his case in the article. The patient is a 55-year-old former smoker without a history of diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension or previous heart disease. However, the patient has a past medical history of migraine treated with rizatriptan. The day of admission the patient presented with a migraine headache with left-sided hemicranial pain. Twenty minutes later, the patient showed clinical signs of oppressive central chest pain of 1-hour duration that radiated to the left upper limb and was associated with paresthesias, nausea, and vomiting. Upon arrival at the ER the patient’s arterial blood pressure levels were 130/70 mmHg with no findings in the physical examination. The electrocardiogram showed ST-segment elevation in leads V1 through V4 with T-wave inversion. The ST-segment elevation came back to normal in the follow-up ECG performed 10 minutes after the index one with persistent T-wave inversion at the anteroseptal side. The blood test showed high troponin T and creatine kinase levels; the hemogram, coagulation test, the basic biochemistry, and chest x-ray all looked normal. The transthoracic echocardiogram performed revealed a slightly depressed systolic function (left ventricular ejection fraction of 50%) at the expense of akinesis in all apical segments. With the clinical, electrocardiographic, analytical, and imaging data it was decided to conduct an emergent hemodynamic study that confirmed the presence of a moderately diffuse stenosis in the mid left anterior descending coronary artery (figure 1); no images suggestive of thrombi or significant stenoses were seen. The lesion was assessed through optical coherence tomography and intravascular ultrasound (figure 2) that confirmed the presence of SCAD with intramural hematoma. During the index procedure, the renal angiography performed showed no signs suggestive of fibromuscular dysplasia.

Figure 1. Moderate stenosis in mid left anterior descending coronary artery consistent with a type 3 spontaneous coronary artery dissection.

Figure 2. Optical coherence tomography (upper row) and intravascular ultrasound (lower row) showing the healthy proximal (A, B) and distal (G, H) segments of the left anterior descending coronary artery, and a spontaneous coronary artery dissection with intramural hematoma (asterisk) in the mid-segment (C-F).

During the patient’s stay at the coronary unit, rizatriptan was changed for amitriptyline and antiplatelet therapy was withdrawn. The transthoracic echocardiogram performed 48 hours after the index event showed a healthy-looking left ventricle with normal ventricular function, without altered segmental myocardial contractility or significant valvular heart disease. The patient was discharged without new episodes of chest pain or migraine crises during the hospital stay. The patient remains free from cardiovascular symptoms or associated events at the 16-month follow-up.

SCADs have been associated with fibromuscular dysplasia, pregnancy, emotional stress, extreme physical exercise, and connective tissue disorders.2 Cohort studies conducted in patients with coronary dissections reveal that migraine is a risk factor in 37% to 46% of the cases.3 This was also confirmed by a study with a series of patients with confirmed SCAD admitted to 22 hospitals from the United States. Thirty-two-point-five per cent of these patients had a past medical history of migraine. In some studies, the presence of migraine was associated with new events of SCAD.

Migraine has been associated with mood swings such as anxiety and depression, which happen to be factors that increase cardiovascular risk.4 Also, it has been associated with vascular phenomena like cerebral vasoconstriction, retinal vasculopathy, vertebral and cervical artery dissection, and cerebrovascular diseases.

The prevalence of SCAD was studied in a cohort of 585 patients with SCAD from Mayo Clinic. Previous migraine episodes were present in up to 40% of the cases. However, only 1 male patient had a past medical history of migraine when the SCAD was diagnosed.4

This case is relevant because of the exceptional combination of a migraine related SCAD in a male patient. To this day, this is the only case ever reported in the medical literature, probably due to the fact that the isolated prevalence of both conditions in males is very low.

FUNDING

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

All authors contributed equally to the realization of this work.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1. Hayes SN, Kim CESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection:Current state of the science:A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;137:e523-e557.

2. Adlam D, Alfonso F, Maas A, Vrints C. European Society of Cardiology, Acute Cardiovascular Care Association, SCAD Study Group:a position paper on spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3353-3368.

3. Nakashima T, Noguchi T, Haruta S, et al. Prognostic impact of spontaneous coronary artery dissection in young female patients with acute myocardial infarction:A report from the Angina Pectoris-Myocardial Infarction Multicenter Investigators in Japan. Int J Cardiol. 2016;207:341-348.

4. Kok SN, Hayes SN, Cutrer FM, et al. Prevalence and clinical factors of migraine in patients with spontaneous coronary artery dissection. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e010140.